- 1West China School of Nursing/ West China Hospital, Sichuan University, Chengdu, China

- 2Key Laboratory of Birth Deficits and Related Diseases of Women and Children, West China Second University Hospital, Sichuan University, Chengdu, China

- 3Department of Pharmacy, Chengdu University of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Chengdu, China

- 4Department of Pharmacy, West China Second University Hospital, Sichuan University, Chengdu, China

Background: Indomethacin and ibuprofen, two commonly used prostaglandin inhibitors, are the drugs of choice for patent ductus arteriosus. However, paracetamol is an alternative choice when these drugs are ineffective or contraindicated. This study aimed to confirm paracetamol's efficacy and safety compared with those of other drugs or placebos for patent ductus arteriosus closure in premature infants.

Methods: We conducted a literature search using the Cochrane Library, PubMed, CINAHL, and EMBASE databases for randomized controlled trials and quasi-randomized controlled trials. We used the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines to direct the process and PICO (P, population; I, intervention/interest; C, comparator; O, outcome) principle to constitute the theme. We combined the research data through qualitative summaries or meta-analyses.

Results: The final analyses included 15 trials (N = 1,313). No significant differences were noted between paracetamol and ibuprofen except for shorter mean days needed for patent ductus arteriosus closure, lower risk of gastrointestinal bleeding, and hyperbilirubinemia. No significant difference existed between paracetamol and indomethacin. Oral paracetamol was more effective than placebo in infants weighing 1,501–2,500 g.

Conclusions: Our study findings tentatively conclude that paracetamol can induce early patent ductus arteriosus closure without significant side effects but that its efficacy is not superior to that of indomethacin.

Introduction

Hemodynamically significant patent ductus arteriosus (PDA) is regularly related to morbidity and mortality among premature infants (1, 2). Only 70% of infants born at 1,000–1,500 g and only 30–35% of infants born at < 1,000 g experience spontaneous PDA closure within 7 days of birth (3, 4). Treating PDA to promote rapid ductal closure may be crucial. Owing to the risks associated with surgery, medication is the first-line treatment (5). Indomethacin and ibuprofen, prostaglandin inhibitors that are commonly used to achieve PDA closure (6, 7), act on active cyclooxygenase (COX) receptors to promote ductal constriction by inhibiting prostaglandin synthesis (8). However, these drugs may induce severe adverse effects including isolated perforation, renal impairment, hyperbilirubinemia, and necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC) (6, 9–11). Most of these contraindications are associated with the pharmacological effects produced by ibuprofen or indomethacin, including a decrease in concentration-related prostaglandin synthesis by non-selective inhibition of the COX receptor of the prostaglandin H2 synthetase enzyme (12). Recent studies demonstrated the effectiveness of paracetamol (a prostaglandin synthetase inhibitor) as an alternative therapy for PDA closure in patients with contraindications for indomethacin or ibuprofen or those who have not been successfully treated with these drugs, which has caused great concern among neonatologists (13–16). Paracetamol is believed to work on prostaglandin synthetase in the peroxidase (POX) receptor of the enzyme, boosting paracetamol-mediated inhibition at decreased local peroxide concentrations (17) and immediately inhibiting prostaglandin synthase activity (18). POX is activated when the peroxide concentration is 10 times lower than that of COX (19). This difference may allow POX inhibition to be optimally effective under conditions of low COX inhibitory activity (20). To date, although a number of correlative randomized controlled trials (RCTs) have compared the therapeutic efficacies of paracetamol and other drugs for PDA closure, most achieved insignificant results (21–25). Paracetamol's efficacy and safety for PDA closure in premature or low-birth-weight infants (or both) have not been fully determined.

Objectives

This systematic review aimed to confirm paracetamol's efficacy and safety compared with those of other drugs or placebo by reviewing RCTs in the literature to increase the sample size.

Research Question

Is paracetamol effective and safe for PDA closure in premature neonates?

Methods

Study Design

This systematic review and meta-analysis was created according to the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews (Intervention version) and complied with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement (26).

Participants, Interventions, and Comparators

Samples were <37 weeks' gestation premature infants or <2,500-g low-birth-weight infants with echocardiography-confirmed PDA regardless of postnatal age. Paracetamol was administered to achieve PDA closure.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

The inclusion criteria for screening studies were as follows: RCTs and quasi-RCTs comparing paracetamol with other drugs or placebo for PDA closure in our target population (regardless of drugs given via oral, intravenous, or rectal route and at any dose). The exclusion criteria were as follows: (i) incomplete article or not published in English (or both); and (ii) administration of paracetamol was not used to achieve PDA closure.

Types of Outcome Measures

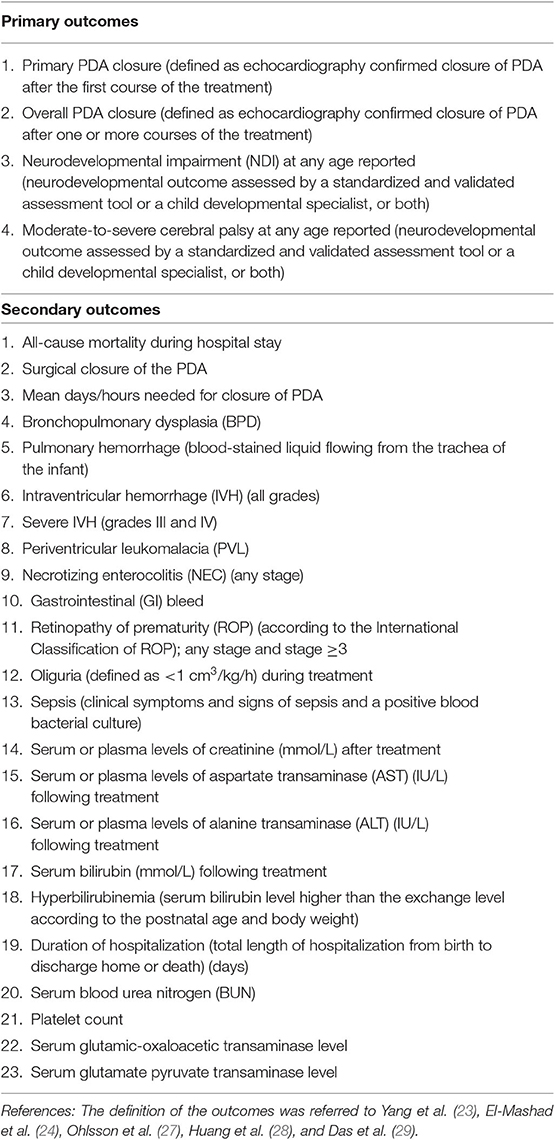

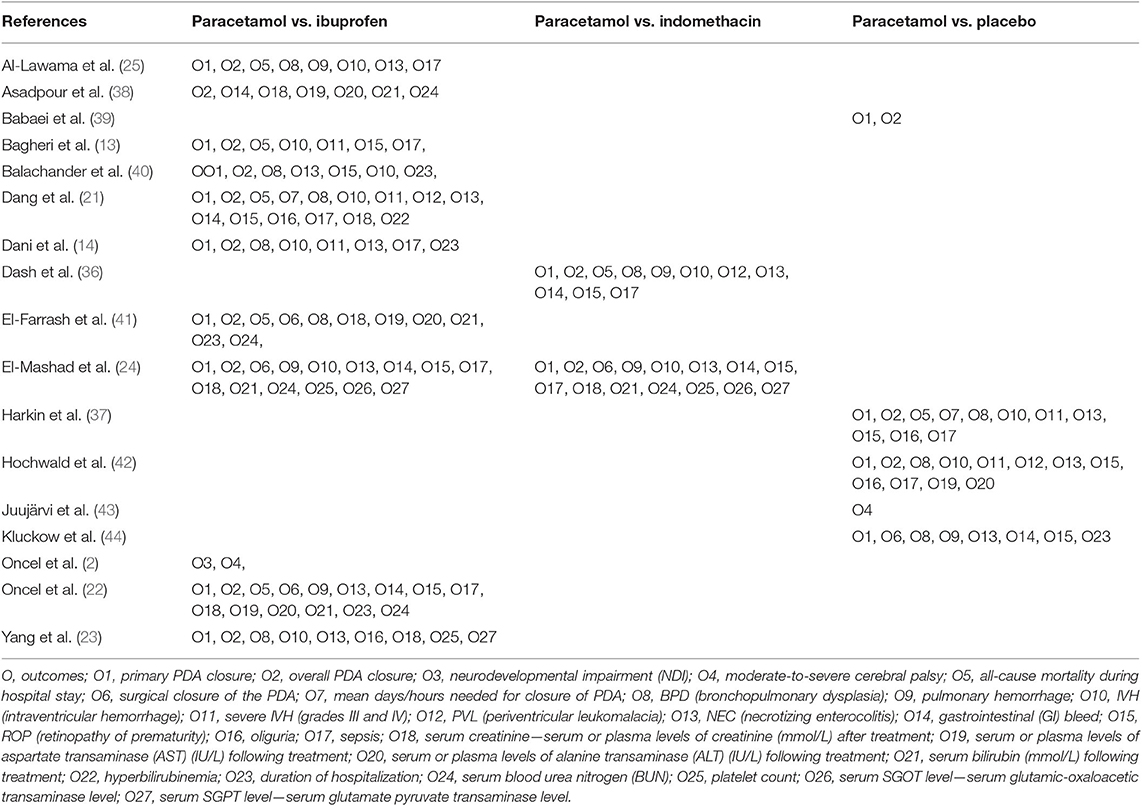

Our outcome types consisted of four primary outcomes and 23 secondary outcomes. Specific outcomes are shown in Table 1.

Search Strategy

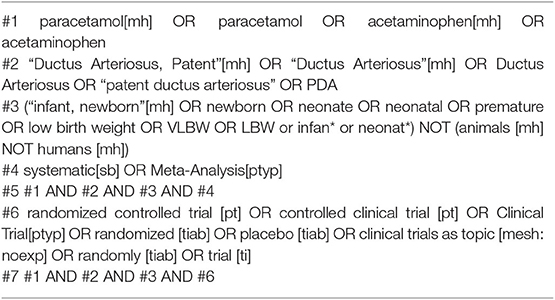

The Cochrane Library, PubMed, CINAHL, and EMBASE databases were searched from the date of their inception to March 2018 to identify published systematic reviews or meta-analyses. Among them, we recognized original RCTs and quasi-RCTs. We also searched the same databases for studies published from December 2013 to March 2018 to identify recently published RCTs and quasi-RCTs. We imposed no language restrictions. The main search terms included “paracetamol,” “ductus arteriosus,” and their synonyms (the specific search strategy used in PubMed is reported in Table 2). We subsequently conducted an updated search (the second search) for studies limited to March 2018 to March 2019 using the same search strategy and searched for terms used in the first search.

Data Sources, Studies Sections, and Data Extraction

Two researchers independently estimated the study qualification on the basis of pre-established criteria and extracted the relevant information from every included study, as follows: publication year, lead author; country conducting trials; characteristics of participants, method of diagnosis; exposure/intervention (paracetamol or any other drug, dose of the drugs, trial duration, and number of courses), and data of results (outcome measures, effect, significance, and adverse events). If studies had more than two sets or allowed multiple tests, we obtained only the requisite data and information reported. Differences were resolved through negotiation or third-party intervention.

Assessment of Risk of Bias

Two researchers independently evaluated the selected trials by applying the criteria listed in the Cochrane Handbook and rated these trials as being of low, high, or unclear risk (30). Differences were resolved as described above.

Data Analysis

We executed a meta-analysis using the Mantel–Haenszel or inverse variance statistical method to calculate risk ratios (RRs) or mean difference (MD) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs). We used Cochran's Q-test to assess heterogeneity and values of P < 0.10 were considered significantly heterogenous (31). Based on the Cochrane Handbook, when there was minimal evidence of heterogeneity, a fixed-effects meta-analysis model was used. When the effect-estimated I2 value was >30%, the random-effects model was used, and we would attempt to determine the reason for the heterogeneity. The sensitivity analysis was performed by stratified analysis. Given that few studies were included in the secondary outcomes part of the study, the subgroup analysis included only the primary outcomes. Subgroups were pre-specified according to administration route (oral, intravenous, or other), gestational age (including <28, 28–32, and 33–36 weeks) and birth weight (including <1,000, 1,000–1,500, and 1,501–2,500 g), which allowed us to estimate whether the relationship between paracetamol and other drugs or placebo was changed by the participants' characteristics. We intended to evaluate potential publication bias by examining a funnel plot. Two-tailed P < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. RevMan version 5.3 was used for all of the analyses.

Results

Description of Studies

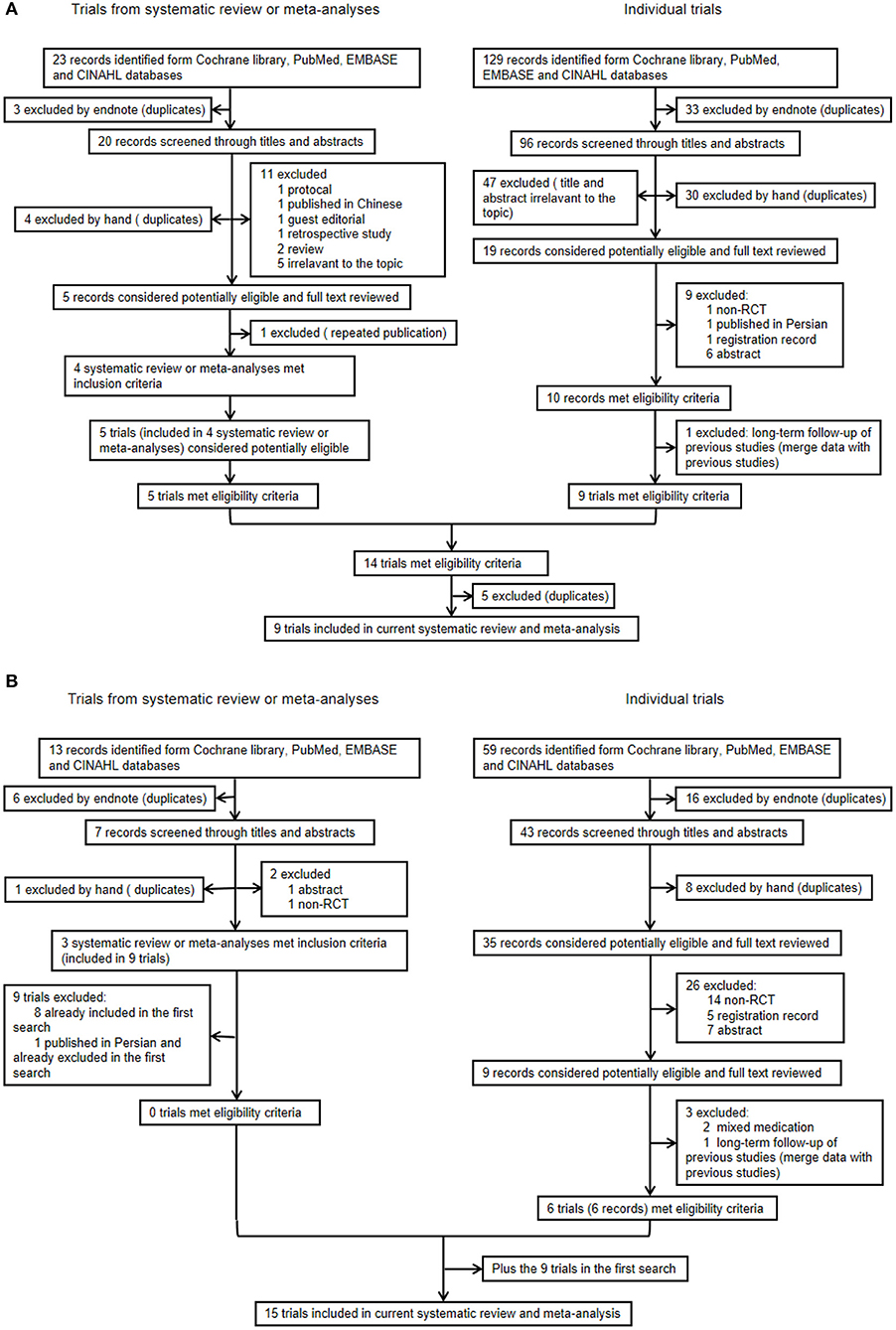

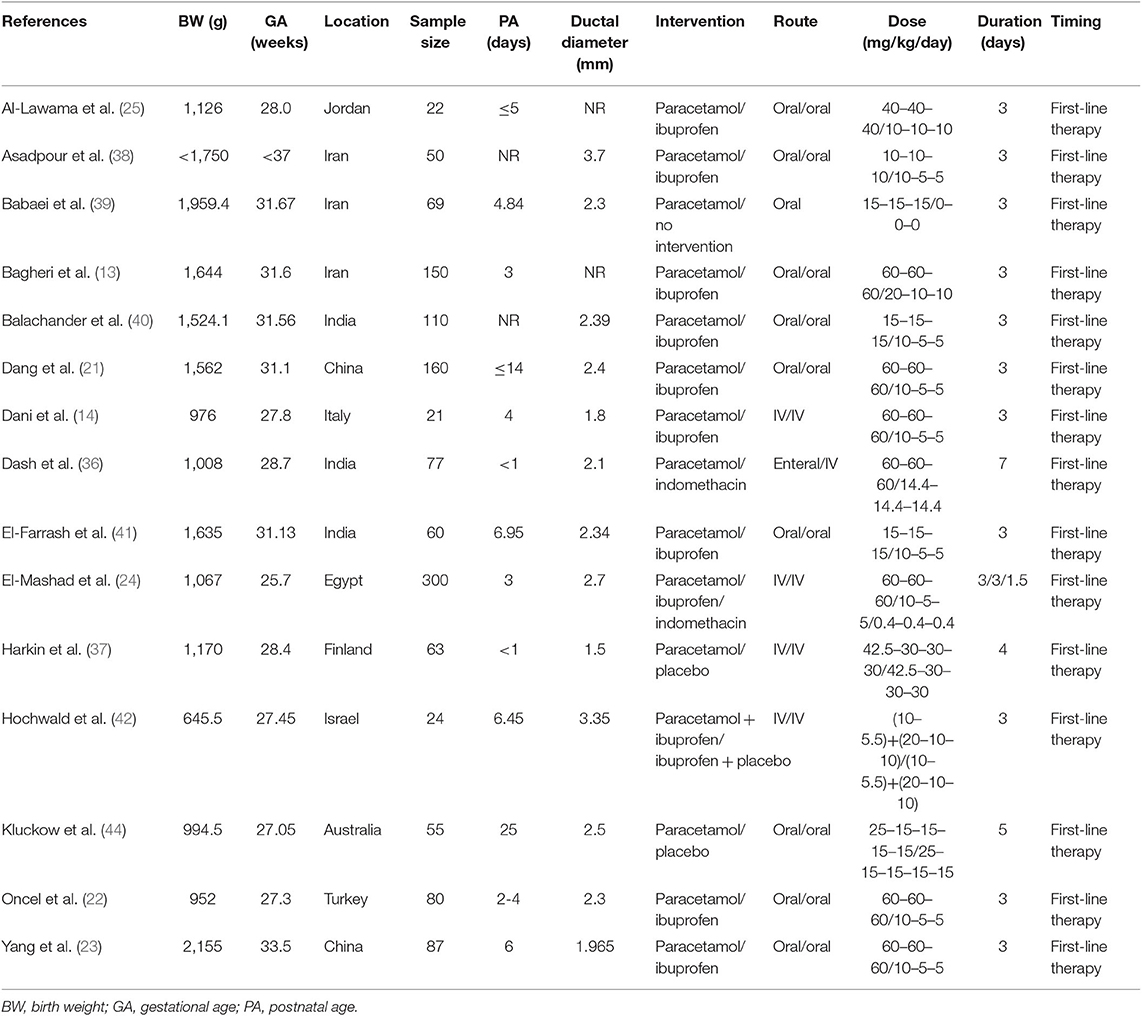

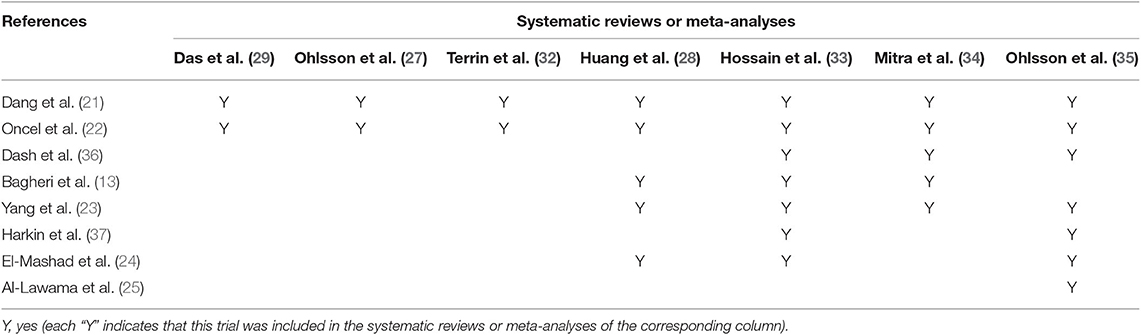

In the first search, of the 23 systematic reviews and 129 citations retrieved, four systematic reviews (27–29, 32) were assessed to extract RCTs or quasi-RCTs (Table 3). The full texts of 10 articles (2, 13, 14, 21–25, 36, 37) that met the inclusion criteria were assessed for eligibility after retrieval of the RCTs or quasi-RCTs (Figure 1). Of these, two (2, 22) came from the same study: one reported short-term outcomes, whereas the other reported long-term outcomes. Thus, the extracted data from those two articles were considered those of a single study. Therefore, nine trials were included in this systematic review in the first search. In the second search, of 13 systematic reviews and 59 citations retrieved, three systematic reviews (33–35) were assessed to extract RCTs or quasi-RCTs (Table 3). Seven records (38–44) containing six trials met our inclusion criteria. Therefore, by summarizing the trials of the first and second searches, 15 trials were eventually included in our review (Table 4). The primary characteristics of the selected trials are displayed in Table 4. The included outcomes of the selected studies are reported in Table 5.

Table 3. Randomized trials included in systematic reviews or meta-analyses evaluating paracetamol for patent ductus arteriosus.

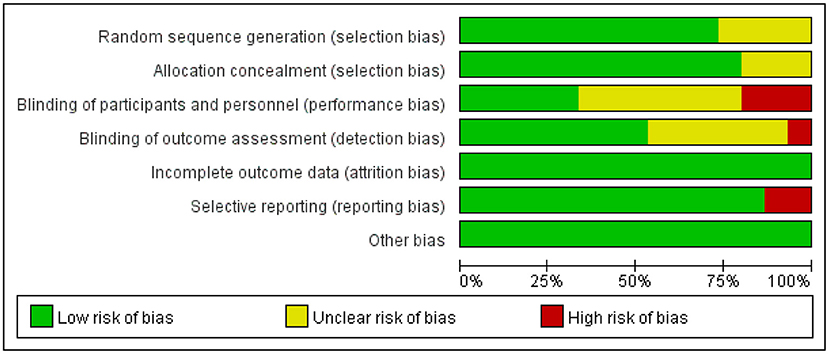

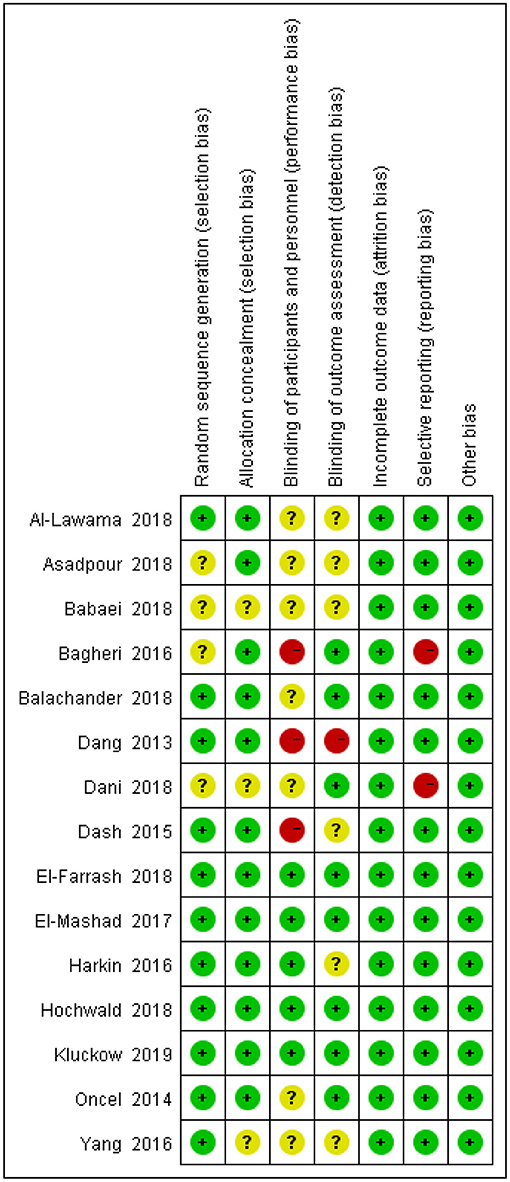

Risk of Bias

The degrees of bias of the selected trials were low to high because of their double-blind, single-blind, or open-label designs. Figures 2, 3 display the evaluation of the degrees of bias.

Effect of Interventions

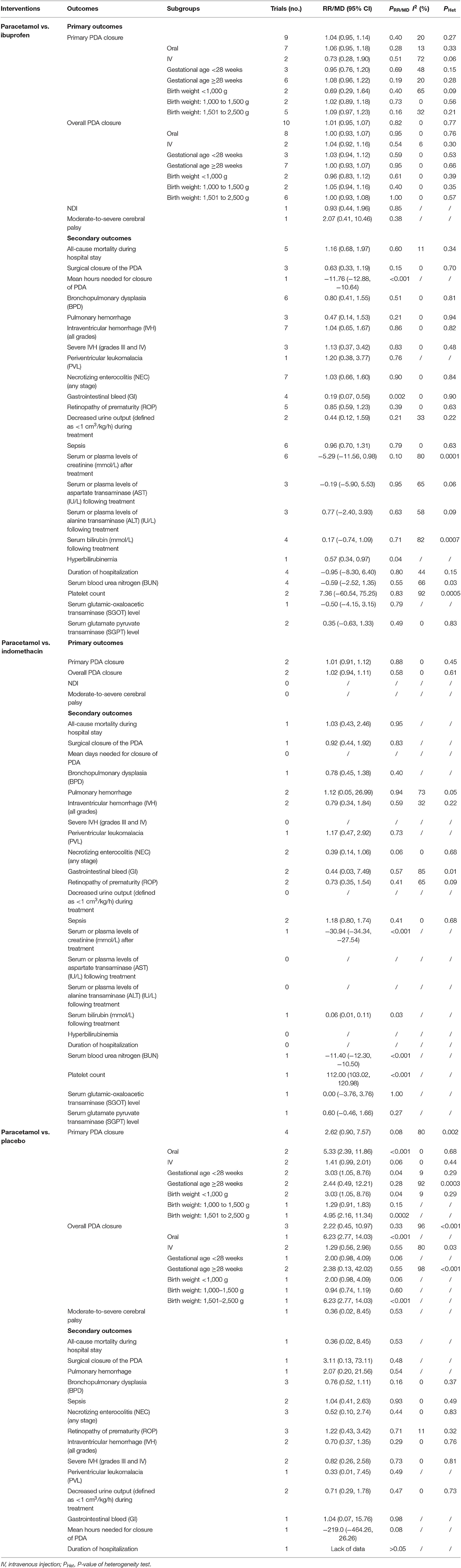

Paracetamol vs. Ibuprofen

When paracetamol was compared with ibuprofen, all 27 outcomes were reported (Table 5). The results of the study showed no significant differences in the pooled results of the primary outcomes between the two set comparison groups regardless of whether a subgroup analysis was performed (Table 6 and Figure 4 show the forest plot of the meta-analysis focusing on primary PDA closure). Among the secondary outcomes, only the pooled results of three outcomes showed statistically significant intergroup differences. Specifically, compared with the ibuprofen group, in the paracetamol group, the mean number of hours needed for PDA closure was significantly shorter [MD, −11.76 (95% CI, −12.88 to −10.64), P < 0.001] and the proportion of gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding [RR, 0.19 95% CI, 0.07–0.56), P = 0.002] and hyperbilirubinemia [RR, 0.57 (95% CI, 0.34–0.97), P = 0.04] were significantly reduced. There was no heterogeneity in these comparisons (Table 5).

Paracetamol vs. Indomethacin

When paracetamol was compared with indomethacin, 18 outcomes were reported, including two primary outcomes and 16 secondary outcomes (Table 5). The results showed no significant intergroup differences in the pooled results of primary outcomes (Table 6). Among the secondary outcomes, only the pooled results of the four outcomes were statistically different between the two groups. However, the reports of these four outcomes were all from the same study (24). Specifically, vs. those in paracetamol group, serum creatinine level [MD, −30.94 (95% CI, 34.34–27.54), P < 0.001] and blood urea nitrogen level [MD, −11.40 (95% CI, −12.30 to −10.50), P < 0.001] were significantly increased in the indomethacin group (P < 0.001), whereas platelet count [MD, 112.00 (95% CI, 103.02–120.98), P < 0.001] and serum bilirubin level after treatment [MD, 0.06 (95% CI, 0.01–0.11), P = 0.03] were significantly lower (P < 0.001) in the indomethacin group (Table 6).

Paracetamol vs. Placebo

Seventeen outcomes were reported in the comparison of paracetamol and placebo (Table 5). Four trials reported the effects of paracetamol vs. placebo for PDA closure. Specifically, two compared paracetamol and placebo, one compared paracetamol and no intervention, and one compared paracetamol plus ibuprofen vs. ibuprofen plus placebo. Although the last comparison was a combined therapy, the study design was a prospective, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled pilot study. So in addition to the influence of paracetamol, the latter two comparisons were similar to those between paracetamol and placebo after balancing differences between groups and were therefore classified as paracetamol vs. placebo. Our meta-analysis showed that the oral paracetamol group better promoted primary PDA closure than did the placebo group. In addition, in the gestational age <28 weeks, body weight <1,000 g, and body weight of 1,501–2,500 g, the paracetamol group better promotes primary PDA closure. Regarding overall PDA closure, the oral paracetamol group, compared with the placebo group, promoted PDA closure for infants weighing <1,000 g and those weighing 1,501–2,500 g. According to the results, no significant intergroup differences existed between paracetamol and placebo in other outcomes (Table 6).

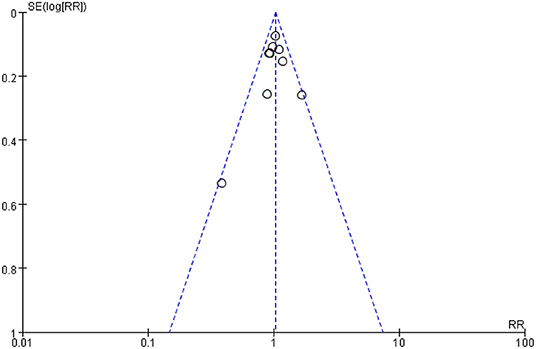

Publication Bias

We inspected a funnel plot for the comparison of primary PDA closure of paracetamol and ibuprofen in our target population and found almost no publication bias (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Funnel Plot of the comparing primary PDA closure of paracetamol and ibuprofen on PDA closure in preterm or low birth weight (or both) infants.

Discussion

This systematic review meta-analyzed the use of paracetamol for PDA closure in premature infants. Our findings can enhance our understanding of the theme.

The following outcomes were not used in the subgroup analyses: mean days needed for PDA closure, GI bleeding, and hyperbilirubinemia. Our study results showed no significant difference between the paracetamol and ibuprofen groups internal or external of the subgroup analyses. Compared with the ibuprofen group, the paracetamol group had shorter mean days for PDA closure, a lower risk of GI bleeding, and lower risk of hyperbilirubinemia. A recent Cochrane systematic review demonstrated no difference in efficacy between oral paracetamol and oral ibuprofen (35). As the same two RCTs were included, Das et al. and Terrin et al. reported the same conclusion as the aforementioned Cochrane systematic review (29, 32). Huang et al. stated that no significant difference existed between paracetamol and ibuprofen in PDA closure in premature neonates by summarizing the results of five RCTs, but the paracetamol group, compared with the ibuprofen group, had a reduced risk of renal failure as well as GI bleeding (28).

In our research, the comparison of paracetamol and ibuprofen identified nine studies that reported primary closure and 10 studies that reported total closure. The results showed that, consistent with other studies (9, 24), paracetamol was as efficacious as ibuprofen in accelerating PDA closure in premature infants. The primary closure and overall closure rates after paracetamol therapy (313/452 = 69.25%; 398/477 = 83.44%) were more or less similar to those after ibuprofen therapy (292/438 = 66.67%; 384/463 = 82.94%). The overall closure rate of our study was slightly higher than that reported by El-Mashad et al. (24), probably because of the higher weights of the infants with a higher mean gestational age after the merger. Higher prostaglandin receptor expression in the PDA wall demonstrated a lesser response to COX inhibition in young premature infants (45). In addition, a longer average treatment time after the merger may have led to a higher closure rate. Consistent with previous studies, our research indicated that the ibuprofen group had a higher incidence of GI bleeding. The potential peripheral effect of vasoconstriction and the potential antiplatelet aggregation effect of ibuprofen could explain the higher GI bleeding tendency in the ibuprofen group (46, 47), and paracetamol did not harm the GI mucosa (48). Another study showed that paracetamol was recommended for infants with clinical contraindications to non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (9). Because only one study reported the mean hours needed for PDA closure, our results supported the conclusion of Das et al. (29) in that the paracetamol group required less time for closure than did the ibuprofen group. Only one study reported hyperbilirubinemia (49). A higher risk of hyperbilirubinemia with ibuprofen use may be explained by the ibuprofen albumin binding with consequent bilirubin displacement (49).

Regarding paracetamol treatment of PDA, two studies reported neurodevelopmental outcomes. A subsequent study by Oncel et al. compared the effects of paracetamol and ibuprofen on pharmacological closure and neurodevelopmental outcomes in premature infants between 18 and 24 months of corrected age (2). Juujärvi et al. conducted a follow-up study of the Harkin study and reported the effects of early intravenous paracetamol on pharmacological closure of neurodevelopmental outcomes at corrected age of 2 years (43). Their results showed no difference in neurodevelopmental outcomes in premature infants receiving paracetamol or ibuprofen/placebo. However, paracetamol works on the endocannabinoid system, which refers to brain development (50). Posadas et al. found that paracetamol caused direct toxicity in rat cortical neurons in vitro as well as in vivo, resulting in apoptosis of the rat cortical neurons (51). In addition, Viberg et al. reported that the effects of neonatal paracetamol exposure on brain development appeared as adult behavior and caused cognitive deficits; likewise, they also changed in response to paracetamol (50). Therefore, rigorous RCTs and cohort studies are needed to clarify the effects of paracetamol on the neurodevelopmental outcomes of infants.

Although some articles reported that paracetamol was safer than indomethacin in terms of side effects (24, 34, 52), our results did not directly produce such results. The main reason was that fewer studies were included. Only one study reported statistically significant adverse outcomes. However, these adverse outcomes did not all point in the same direction (both beneficial and harmful). However, there was a slight trend in the favoring paracetamol over indomethacin in terms of primary PDA closure [RR, 1.01 (95% CI, 0.91–1.12), P = 0.88] and overall PDA closure [RR, 1.02 (95% CI, 0.94–1.11), P = 0.88] (Table 6), but the difference did not reach statistical significance. This research only included two trials with a lower sample size, which may have led to the current analyses lacking statistical power to support this association. In the USA, many centers use indomethacin as a drug to prevent (severe) intraventricular hemorrhage (IVH) (53), although this is not a property of paracetamol. A study has shown that prophylactic indomethacin administration given in extremely premature infants at level 4 neonatal intensive care units (NICUs) could improve survival but had no significant effect on the incidence of severe IVH or PDA closure (54). Therefore, the current evidences make it difficult to distinguish which of the two drugs is the best.

Regarding the comparison of paracetamol and placebo for PDA closure, four trials satisfied the inclusion criteria. According to our meta-analysis, oral paracetamol achieved more PDA closures, whether primary or total. Paracetamol was also better than placebo for PDA closure in infants at <28 weeks' gestational age, a birth weight <1,000 g, or a birth weight of 1,501–2,500 g. In addition, no significant difference was found between paracetamol and indomethacin in the aspects of all secondary outcomes. Given these results, we tentatively conclude that paracetamol can induce early PDA closure without noticeable side effects. However, because many of the adverse outcomes (such as periventricular leukomalacia and GI bleeding) were reported in only one study, these findings should be treated cautiously owing to the insufficient numbers of patients to thoroughly assess efficiency and safety.

Limitations

The results of this analysis have several disadvantages. First, we discovered RCTs from published systematic reviews and meta-analyses in English, possibly omitting trials published in other languages that satisfied the inclusion criteria. Second, the included trials had open-label or single-blinded or double-blinded designs, which were not always of high quality. Third, because PDA has a high spontaneous closure rate, it is not a major problem for larger infants. Fourth, the diagnosis and treatment of PDA remain controversial, and the included studies may have had different echocardiographic criteria that may have impacted the outcomes. Fifth, we conducted stratified analyses on the basis of the different characteristics of the premature infants, but owing to the small number of studies, it was difficult to conduct a more detailed analysis. At the same time, the stratification further led to a decrease in sample size, making it difficult to draw accurate conclusions. Finally, in this updated systematic review, because of the few numbers of studies involving paracetamol vs. placebo, we classified the use of ibuprofen + paracetamol vs. ibuprofen + placebo as paracetamol vs. placebo. This comparison was a prospective, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled pilot study; in addition to the influence of paracetamol, the comparison was similar to paracetamol vs. placebo after balancing differences between groups, but the combined therapy may have affected the primary or secondary outcomes.

Further Areas of Research

Double-blind parallel trials and cohort studies of a larger sample should be conducted to further confirm the long- and short-term efficiency and safety of the above drugs and the differences among them. Trials should report all the useful and important outcomes described in this review at a minimum. When using any drug, safety and efficacy should also be studied in different subgroups of premature infants (characteristics that affect therapeutic efficacy include gestational age, birth weight, dosages, administration route, and timing). To reduce the impact of spontaneous closure, trials should select extremely premature infants (gestational age ≤ 24 weeks or birth weight <1,000 g).

Conclusion

Compared with ibuprofen, paracetamol showed specific effects for PDA closure owing to fewer adverse reactions. Specifically, paracetamol showed shorter mean days needed for closure, a lower percentage of GI bleeding, and lower risk of hyperbilirubinemia. Compared with indomethacin, paracetamol did not differ in efficacy or safety. Compared with placebo, paracetamol could promote PDA closure without adverse reactions in this meta-analysis. These findings tentatively conclude that paracetamol can induce early PDA closure without noticeable side effects but do not demonstrate that paracetamol is superior to indomethacin. Therefore, more well-designed studies are needed to enrich the evidence of this treatment. Finally, because of the controversy in the diagnosis and treatment of PDA in premature infants, this updated systematic review and meta-analysis only summarizes the existing evidence and does not make any recommendations.

Data Availability Statement

All datasets generated for this study are included in the article/supplementary material.

Author Contributions

YX, HL, and XJ conceived this study. YX and RH designed the search strategy and screened studies for eligibility. YX, QY, and XJ assessed study risk of bias and the quality of evidence. YX, RH, and QY wrote the first draft of the manuscript and conducted data analysis. HL, MZ, and XJ interpreted the data analysis and critically revised the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

1. Sellmer A, Bjerre JV, Schmidt MR, McNamara PJ, Hjortdal VE, Høst B, et al. Morbidity and mortality in preterm neonates with patent ductus arteriosus on day 3. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. (2013) 98:F505–10. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2013-303816

2. Oncel MY, Eras Z, Uras N, Canpolat FE, Erdeve O, Oguz SS. Neurodevelopmental outcomes of preterm infants treated with oral paracetamol versus ibuprofen for patent ductus arteriosus. Am J Perinatol. (2017) 34:1185–9. doi: 10.1055/s-0037-1601564

3. Nemerofsky SL, Parravicini E, Bateman D, Kleinman C, Polin RA, Lorenz JM. The ductus arteriosus rarely requires treatment in infants > 1000 grams. Am J Perinatol. (2008) 25:661–6. doi: 10.1055/s-0028-1090594

4. Martin RJ. Prevalence of spontaneous closure of the ductus arteriosus in neonates at a birth weight of 1000 grams or less. Yearbook Neonatal Perinatal Med. (2007) 2007:115–7. doi: 10.1016/S8756-5005(08)70072-6

5. Rostas SE, McPherson CC. Pharmacotherapy for patent ductus arteriosus: Current options and outstanding questions. Curr Pediatr Rev. (2016) 12:110–9. doi: 10.2174/157339631202160506002028

6. Ohlsson A, Shah Prakeshkumar S. Paracetamol (acetaminophen) for patent ductus arteriosus in preterm or low-birth-weight infants. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (2015) 4:CD010061. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD010061.pub2

7. Gulack BC, Laughon MM, Clark RH, Sankar MN, Hornik CP, Smith PB. Comparative effectiveness and safety of indomethacin versus ibuprofen for the treatment of patent ductus arteriosus. Early Hum Dev. (2015) 91:725–9. doi: 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2015.08.003

8. Hammerman C, Bin-Nun A, Kaplan M. Managing the patent ductus arteriosus in the premature neonate: a new look at what we thought we knew. Semin Perinatol. (2012) 36:130–8. doi: 10.1053/j.semperi.2011.09.023

9. Hammerman C, Bin-Nun A, Markovitch E, Schimmel MS, Kaplan M, Fink D. Ductal closure with paracetamol: a surprising new approach to patent ductus arteriosus treatment. Pediatrics. (2011) 128:1618–21. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-0359

10. Johnston PG, Gillam-Krakauer M, Fuller MP, Reese J. Evidence-based use of indomethacin and ibuprofen in the neonatal intensive care unit. Clin Perinatol. (2012) 39:111–36. doi: 10.1016/j.clp.2011.12.002

11. Rao R, Bryowsky K, Mao J, Bunton D, McPherson C, Mathur A. Gastrointestinal complications associated with ibuprofen therapy for patent ductus arteriosus. J Perinatol. (2011) 31:465–70. doi: 10.1038/jp.2010.199

12. Anderson BJ. Paracetamol (acetaminophen): mechanisms of action. Paediatr Anaesth. (2008) 18: 915–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9592.2008.02764.x

13. Bagheri MM, Niknafs P, Sabsevari F, Torabi MH, Bahman Bijari B, Noroozi E, et al. Comparison of oral acetaminophen versus ibuprofen in premature infants with patent ductus arteriosus. Iran J Pediatr. (2016) 26:e3975. doi: 10.5812/ijp.3975

14. Dani C, Poggi C, Cianchi I, Corsini I, Vangi V, Pratesi S. Effect on cerebral oxygenation of paracetamol for patent ductus arteriosus in preterm infants. Eur J Pediatr. (2018) 177:533–9. doi: 10.1007/s00431-018-3086-1

15. Le J, Gales MA, Gales BJ. Acetaminophen for patent ductus arteriosus. Ann Pharmacother. (2015) 49:241–6. doi: 10.1177/1060028014557564

16. Allegaert K, Anderson B, Simons S, van Overmeire B. Paracetamol to induce ductus arteriosus closure: is it valid? Arch Dis Child. (2013) 98:462–6. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2013-303688

17. Oncel MY, Erdeve O. Safety of therapeutics used in management of patent ductus arteriosus in preterm infants. Curr Drug Saf. (2015) 10:106–12. doi: 10.2174/1574886309999141030142847

18. Green K, Drvota V, Vesterqvist O. Pronounced reduction of in vivo prostacyclin synthesis in humans by paracetamol. Prostaglandins. (1989) 37:311–5. doi: 10.1016/0090-6980(89)90001-4

19. Lucas R, Warner TD, Vojnovic I, Mitchell JA. Cellular mechanisms of acetaminophen: role of cyclo-oxygenase. FASEB J. (2005) 19:635–37. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-2437fje

20. Kulmacz RJ, Wang LH. Comparison of hydroperoxide initiator requirements for the cyclooxygenase activities of prostaglandin H synthase-1 and−2. J Biol Chem. (1995) 270:24019–23. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.41.24019

21. Dang D, Wang D, Zhang C, Zhou W, Zhou Q, Wu H. Comparison of oral paracetamol versus ibuprofen in premature infants with patent ductus arteriosus: a randomized controlled trial. PLoS ONE. (2013) 8:e77888. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0077888

22. Oncel MY, Yurttutan S, Erdeve O, Uras N, Altug N, Oguz SS, et al. Oral paracetamol versus oral ibuprofen in the management of patent ductus arteriosus in preterm infants: a randomized controlled trial. J Pediatr. (2014) 164:510–514.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2013.11.008

23. Yang B, Gao X, Ren Y, Wang Y, Zhang Q. Oral paracetamol vs. oral ibuprofen in the treatment of symptomatic patent ductus arteriosus in premature infants: a randomized controlled trial. Exp Ther Med. (2016) 12:2531–6. doi: 10.3892/etm.2016.3676

24. El-Mashad A, El-Mahdy H, El Amrousy D, Elgendy M, El-Mashad AE-R. Comparative study of the efficacy and safety of paracetamol, ibuprofen, and indomethacin in closure of patent ductus arteriosus in preterm neonates. Eur J Pediatr. (2017) 176:233–40. doi: 10.1007/s00431-016-2830-7

25. Al-Lawama M, Alammori I, Abdelghani T, Badran E. Oral paracetamol versus oral ibuprofen for treatment of patent ductus arteriosus. J Int Med Res. (2018) 46:811–8. doi: 10.1177/0300060517722698

26. Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gøtzsche PC, Ioannidis JP, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. PLoS Med. (2009) 6:e1000100. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000100

27. Ohlsson A, Walia R, Shah SS. Ibuprofen for the treatment of patent ductus arteriosus in preterm or low birth weight (or both) infants. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (2015) 18:CD00348. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003481.pub6

28. Huang X, Wang F, Wang K. Paracetamol versus ibuprofen for the treatment of patent ductus arteriosus in preterm neonates: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. (2017) 31:2216–22. doi: 10.1080/14767058.2017.1338263

29. Das RR, Arora K, Naik SS. Efficacy and safety of paracetamol versus ibuprofen for treating patent ductus arteriosus in preterm infants: a meta-analysis. J Clin Neonatol. (2014) 3:183–90. doi: 10.4103/2249-4847.144747

30. Higgins JPT, Green S, editors. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions, Version 5.1.0. Cochrane Collaboration. Available online at: http://training.cochrane.org/handbook. 2011 (accessed April 22, 2019).

31. Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. (2003) 327:557–60. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557

32. Terrin G, Conte F, Oncel MY, Scipione A, McNamara PJ, Simons S, et al. Paracetamol for the treatment of patent ductus arteriosus in preterm neonates: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. (2015) 101:F127–36. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2014-307312

33. Hossain J, Shabuj MK. Oral paracetamol versus intravenous paracetamol in the closure of patent ductus arteriosus: a proportion meta-analysis. J Clin Neonatol. (2018) 7:121–4. doi: 10.4103/jcn.JCN_119_17

34. Mitra S, Florez ID, Tamayo ME, Mbuagbaw L, Vanniyasingam T, Veroniki AA, et al. Association of placebo, indomethacin, ibuprofen, and acetaminophen with closure of hemodynamically significant patent ductus arteriosus in preterm infants: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. (2018) 319:1221–38. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.1896

35. Ohlsson A, Shah PS. Paracetamol (acetaminophen) for patent ductus arteriosus in preterm or low birth weight infants. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (2018) 4:CD010061. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD010061.pub3

36. Dash SK, Kabra NS, Avasthi BS, Sharma SR, Padhi P, Ahmed J. Enteral paracetamol or intravenous indomethacin for closure of patent ductus arteriosus in preterm neonates: a randomized controlled trial. Indian Pediatr. (2015) 52:573–8. doi: 10.1007/s13312-015-0677-z

37. Härkin P, Härmä A, Aikio O, Valkama M, Leskinen M, Saarela T, et al. Paracetamol accelerates closure of the ductus arteriosus after premature birth: a randomized trial. J Pediatr. (2016) 177:72–7.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2016.04.066

38. Asadpour N, Harandi PS, Hamidi M, Malek Ahmadi MR, Malekpour-Tehrani A. Comparison of the effect of oral acetaminophen and ibuprofen on patent ductus arteriosus closure in premature infants referred to hajar hospital in Shahrekord in 2016–2017. J Clin Neonatol. (2018) 7:224–30. doi: 10.4103/jcn.JCN_47_18

39. Babaei H, Nemati R, Daryoshi, H. Closure of patent ductus arteriosus with oral acetaminophen in preterm neonates: a randomized trial. Biomed Res Ther. (2018) 5:2034–44. doi: 10.15419/bmrat.v5i02.418

40. Balachander B, Mondal N, Bhat V, Adhisivam B, Kumar M, Satheesh S, et al. Comparison of efficacy of oral paracetamol versus ibuprofen for PDA closure in preterms - a prospective randomized clinical trial. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. (2018) 29:1–6. doi: 10.1080/14767058.2018.1525354

41. El-Farrash RA, El Shimy MS, El-Sakka AS, Ahmed MG, Abdel-Moez DG. Efficacy and safety of oral paracetamol versus oral ibuprofen for closure of patent ductus arteriosus in preterm infants: a randomized controlled trial. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. (2018) 9:1–8. doi: 10.1080/14767058.2018.1470235

42. Hochwald O, Mainzer G, Borenstein-Levin L, Jubran H, Dinur G, Zucker M, et al. Adding paracetamol to ibuprofen for the treatment of patent ductus arteriosus in preterm infants: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled pilot study. Am J Perinatol. (2018) 35:1319–25. doi: 10.1055/s-0038-1653946

43. Juujärvi S, Kallankari H, Pätsi P, Leskinen M, Saarela T, Hallman M, et al. Follow-up study of the early, randomised paracetamol trial to preterm infants, found no adverse reactions at the two-years corrected age. Acta Paediatr. (2019) 108:452–8. doi: 10.1111/apa.14614

44. Kluckow M, Carlisle H, Broom M, Woods P, Jeffery M, Desai D, et al. A pilot randomised blinded placebo-controlled trial of paracetamol for later treatment of a patent ductus arteriosus. J Perinatol. (2019) 39:102–7. doi: 10.1038/s41372-018-0247-z

45. Roofthooft DW, van Beynum IM, de Klerk JC, van Dijk M, van den Anker JN, Reiss IK, et al. Limited effects of intravenous paracetamol on patent ductus arteriosus in very low birth weight infants with contraindications for ibuprofen or after ibuprofen failure. Eur J Pediatr. (2015) 174:1433–40. doi: 10.1007/s00431-015-2541-5

46. Kanabar DJ. A clinical and safety review of paracetamol and ibuprofen in children. Inflammopharmacology. (2017) 25:1–9. doi: 10.1007/s10787-016-0302-3

47. Rainsford KD. Ibuprofen: pharmacology, efficacy and safety. Inflammopharmacology. (2009) 17:275–342. doi: 10.1007/s10787-009-0016-x

48. Graham GG, Davies MJ, Day RO, Mohamudally A, Scott KF. The modern pharmacology of paracetamol: therapeutic actions, mechanism of action, metabolism, toxicity and recent pharmacological findings. Inflammopharmacology. (2013) 21:201–32. doi: 10.1007/s10787-013-0172-x

49. Diot C, Kibleur Y, Desfrere L. Effect of ibuprofen on bilirubin-albumin binding in vitro at concentrations observed during treatment of patent ductus arteriosus. Early Hum Dev. (2010) 86:315–7. doi: 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2010.04.006

50. Viberg H, Eriksson P, Gordh T, Fredriksson A. Paracetamol (acetaminophen) administration during neonatal brain development affects cognitive function and alters its analgesic and anxiolytic response in adult male mice. Toxicol Sci. (2014) 138:139–47. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kft329

51. Posadas I, Santos P, Blanco A, Munoz-Fernandez M, Cena V. Acetaminophen induces apoptosis in rat cortical neurons. PLoS ONE. (2010) 5:e15360. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0015360

52. Yajamanyam PK, Kanani AN, Rasiah SV. Management of patent ductus arteriosus in preterm infants—where do we stand? A UK national perspective. Congenit Heart Dis. (2015) 10:86–7. doi: 10.1111/chd.12170

53. van Bel F, Vaes J, Groenendaal F. Prevention, reduction and repair of brain injury of the preterm infant. Front Physiol. (2019) 10:181. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2019.00181

Keywords: ductus arteriosus, patent, infant, premature, paracetamol, ibuprofen, indomethacin

Citation: Xiao Y, Liu H, Hu R, You Q, Zeng M and Jiang X (2020) Efficacy and Safety of Paracetamol for Patent Ductus Arteriosus Closure in Preterm Infants: An Updated Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front. Pediatr. 7:568. doi: 10.3389/fped.2019.00568

Received: 09 April 2019; Accepted: 30 December 2019;

Published: 18 February 2020.

Edited by:

Mikko Hallman, University of Oulu, FinlandReviewed by:

Frank Van Bel, University Medical Center Utrecht, NetherlandsTimo Vesa Saarela, Oulu University Hospital, Finland

Copyright © 2020 Xiao, Liu, Hu, You, Zeng and Jiang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Xiaolian Jiang, amlhbmdfeGlhb2xpYW4mI3gwMDA0MDsxMjYuY29t

Yingqi Xiao

Yingqi Xiao Hui Liu2

Hui Liu2