- 1Department of Human Genetics, McGill University, Montreal, QC, Canada

- 2Psychiatric Genetics Group, Douglas Mental Health University Institute, Montreal, QC, Canada

- 3Department of Psychiatry, McGill University, Montreal, QC, Canada

- 4Integrated Program in Neuroscience, McGill University, Montreal, QC, Canada

Brain development is a highly regulated process that involves the precise spatio-temporal activation of cell signaling cues. Transcription factors play an integral role in this process by relaying information from external signaling cues to the genome. The transcription factor Forkhead box G1 (FOXG1) is expressed in the developing nervous system with a critical role in forebrain development. Altered dosage of FOXG1 due to deletions, duplications, or functional gain- or loss-of-function mutations, leads to a complex array of cellular effects with important consequences for human disease including neurodevelopmental disorders. Here, we review studies in multiple species and cell models where FOXG1 dose is altered. We argue against a linear, symmetrical relationship between FOXG1 dosage states, although FOXG1 levels at the right time and place need to be carefully regulated. Neurodevelopmental disease states caused by mutations in FOXG1 may therefore be regulated through different mechanisms.

Introduction

Mammalian brain development involves cell proliferation and differentiation of cells into specific types, usually in response to diffusible signaling cues and cell-cell interactions. It is the precise spatio-temporal order of cell division, growth, motility, and cell fate determination that leads to the specified structures of the mammalian central nervous system, including the forebrain (telencephalon), midbrain (mesencephalon), and hindbrain (rhombencephalon) (1, 2). External signals may initiate specific cell programs but inside each cell is a complex messenger system whereby critical signals for development are relayed to the genome to induce gene expression and to make mRNA and protein for specific functions. Transcription factors play a critical role in this process, forming an output for external signaling cues and second messengers by directly interacting with the genome. Forkhead Box G1 [FOXG1; previously known as BF-1 (3)] is one such factor and is necessary for the development of the telencephalon (4, 5), though is also expressed in the retina, inner ear, and olfactory bulb. The homozygous loss of Foxg1 in mouse leads to a severe reduction in telencephalic structures (5), and the loss of one copy of FOXG1 in human leads to postnatal microcephaly, severe developmental delay, and structural brain deficits such as cerebral atrophy, gyral simplification, hypomyelination, and a thin or absent corpus callosum (6).

The concept of gene dose refers to the amount of product (mRNA and/or protein) produced from a given allele or mRNA. In some cases, allelic expression is imbalanced where one allele may contribute more product than another allele (7). This can be a normal state and does not necessarily imply disease, as evidenced by imprinting effects and monoallelic expression from several genes (7, 8). In other cases, a change in gene dose (through deletion or duplication, for example) may have no effect on proliferation or cell fate determination. Why is it that some regions of the genome are dosage sensitive while others are not (9)? In the case of Down Syndrome (DS), for example, all genes on chromosome 21 are increased by 50% (three alleles per gene instead of two), yet not all genes show increased expression (10), nor is it the case that genes that show increased expression contribute to the DS phenotype. It is thought that increased dose from only a few genes [the DS critical region (11)] are required for the disease phenotype. This implies that increased expression from several genes on chromosome 21 have no effect on cell fate and so these genes are presumably not dosage sensitive.

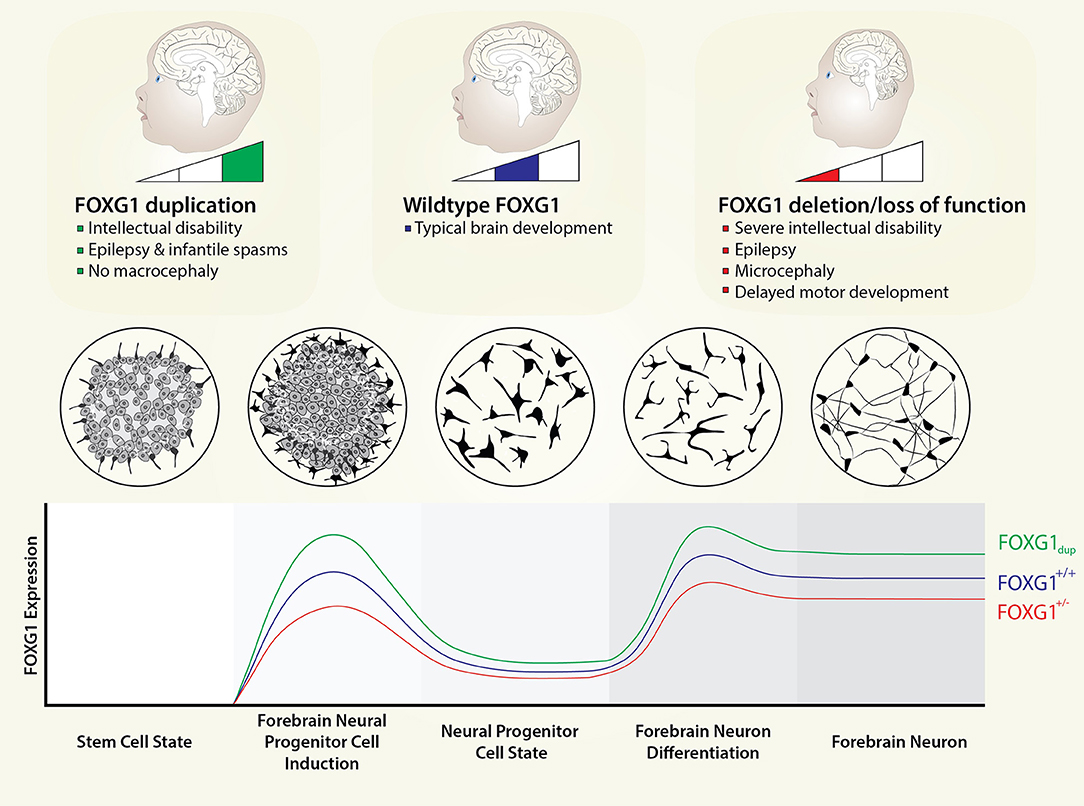

There are a few known biological reasons why dosage can be important for some genes and not for others. Often, it is intimately related to the biological activity of the encoded protein. For example, some transcription factors may need to partner with another factor to exert an effect and in the absence of one transcription factor the other will bind with a different partner, leading to different cellular effects. The chromatin remodeling complexes BAF (SWI/SNF) and TIP60 are a good example of this (12–14), where several proteins associate to drive an effect, but the same complex with a few changes in binding patterns can lead to a different cellular effect. Genes that code for these specific proteins would thus be considered dosage sensitive. Several human syndromes that cause neurodevelopmental disease can be considered sensitive to gene dose (15); including FOXG1 deletion syndrome, though it is not clear why FOXG1 dosage is so critical (Figure 1). To address this question, we have laid out this review by looking at FOXG1 dose in multiple model systems, diseases, and tissue types, and analyzing molecular interacting patterns and signaling pathways that could contribute to dosage sensitivity. Our hope is that integrating information from different research areas and studies might better illuminate the role of FOXG1 dose in human neurodevelopment.

Figure 1. FOXG1 dosage in neurodevelopment. FOXG1 expression levels are currently unknown; however, FOXG1 is one of the earliest genes to be expressed in mammalian telencephalon. We envision FOXG1 expression being activated well before terminal differentiation of forebrain neurons and even forebrain neural progenitors. Here, we depict expression patterns from a stem cell state to forebrain neurons, with induction and maintenance states defined. Circular plates show the appearance of cells in vitro for the different cell states. We model FOXG1 dosage changes as linear with respect to gene dosage, even though the molecular effects of FOXG1 protein (e.g., interaction with different proteins or different genomic regions) are not necessarily linear with respect to protein dose.

Forkhead Box Family

Forkhead box (Fox) transcription factors belong to a superfamily of related proteins characterized by a winged-helix DNA-binding domain approximately 110 residues long (16, 17). Fox transcription factors bind a similar DNA sequence, albeit with different affinities, due to their highly conserved DNA-binding motif. These genes have been ubiquitously present during the evolutionary history of vertebrates and invertebrates, from worms to humans (18–23). The evolutionary expansion of Fox gene family members has been driven by the increased developmental and tissue complexity required of higher organisms (24).

Fox protein regulation and function vary significantly between families, arising in part from sequence variation outside of the DNA-binding forkhead domain, allowing for differential regulation and functional diversification. As a result, Fox proteins have been found to participate in numerous physiological processes and biological functions including embryonic development and organogenesis, cell cycle regulation, metabolism control, stem cell niche maintenance, and signal transduction (24, 25). While their role in developmental patterning is well known, many Fox genes continue to be expressed in post-embryonic structures, suggesting there are other important functions that have yet to be elucidated (26).

The total number of Fox genes varies widely among different organisms. C. elegans have 15 compared to 44 known Fox genes in humans (24). The mammalian forkhead family of transcription factors are categorized into subclasses A to S based on sequence similarity within and outside of the forkhead box (25, 27). The divergent sequences outside of the conserved DNA-binding domain likely distinguish between the function of these proteins, in addition to their distinct temporal and spatial expression patterns.

Forkhead Box G1 (FOXG1)

Like all Fox family members, the winged-helix transcription factor forkhead box G1 (FOXG1; formerly named forebrain-restricted transcription factor BF-1, qin, Chicken Brain Factor 1, or XBF-1) is characterized by unique sequences of amino acids within the forkhead-binding domain (FHD) (25). FOXG1 is expressed in a variety of nervous system cell types and tissues, including the cerebral cortex, telencephalon, inner ear, retina, olfactory epithelial cells, and other neural and sensory tissues in mammals (28). The timing of its expression also varies by tissue type.

In humans, FOXG1 is located on chromosome 14q12 and contains only one coding exon (29, 30). The amino acid sequence from the FHD to C-terminal domain is highly conserved (29), with the N-terminal domain being more variable among species. In addition to the FHD, FOXG1 consists of a 10-residue histone demethylase (KDM5B; previously JARID1B)-binding domain (JBD) and a 20-residue Groucho (Gro)-binding domain (GBD). The FHD consists of three alpha helices and one beta hairpin (two beta strands and one loop) (6).

FoxG1 primarily acts as a transcriptional repressor in the embryonic telencephalon (31, 32). From multiple studies of FoxG1 deficiency in animal models, it has become apparent that FoxG1 plays a vital role in brain development, ranging from telencephalon specification and patterning and neuronal differentiation, to maintenance and survival of mature neurons (26). Mouse knockout (KO) studies of Foxg1 revealed it to be a regulator of neurogenesis in which it regulates early cortical cell fate by coordinating the expression of an early transcriptional network in the cerebral cortex (33–35). Thus, FoxG1 is not just one of many important transcription factors in brain development; rather it is considered a pioneer transcription factor in that it is one of the earliest expressed in this cell type and can alter the structure of chromatin to allow other factors to bind (36).

Role of FOXG1 in the Development of the Vertebrate Telencephalon

The transcription factor Foxg1 is essential for the normal development of the telencephalon. The vertebrate forebrain (prosencephalon) arises from the largest portion of the neural tube—a structure derived from the neuroectoderm composed of a layer of neuroepithelial cells. From there, bilateral swellings known as telencephalic vesicles are generated in the most rostral region to form the telencephalon (37). The cerebral cortex forms from the dorsal telencephalon, while the basal ganglia develop from the ventral telencephalon. These dorsal and ventral regions are patterned by the activities of many secreted morphogens produced by different signaling centers (38–43).

Multiple signals are required for the correct specification of the telencephalon including bone morphogenetic proteins (BMPs), wingless/integrated proteins (WNTs), extracellular signal fibroblast growth factor 8 (FGF8), and sonic hedgehog (SHH) (44–47). In the embryonic telencephalon, SHH is produced ventrally, FGF8 is produced rostrally and multiple BMPs and WNT proteins are produced caudo-medially (35). These morphogens and others coordinate the expression of transcription factors including FOXG1 that regulate subsequent telencephalic development. The fine-tuning of Foxg1 expression levels by specific spatio-temporal signals from other morphogens and their second messenger relays is what allows for the precise development of the telencephalon; though exactly how this occurs is not well understood. Foxg1 is one of the earliest transcription factors to be expressed during early neurogenesis and responds to a variety of signaling cues (48). A detailed description of Foxg1 activity during brain development is reviewed in Kumamoto and Hanashima and Danesin and Houart (26, 49). Here, we will briefly summarize the spatio-temporal patterning of mammalian brain development at the onset of Foxg1 expression, using mice as a model system.

At embryonic day 8.5 (E8.5), Foxg1 expression is present in the most rostral region of the neural tube. Foxg1 and Shh both promote Fgf8 expression in the anterior neural ridge (ANR) to pattern the nascent telencephalon (40). The ANR is a region in the neural plate which acts as a secondary organizer and secretes signaling molecules that generate the anterior-posterior patterning of the forebrain. Foxg1 directly promotes Fgf8 expression, while Shh indirectly promotes Fgf8 expression by inhibiting Gli3 repression of Fgf8 (40). As a result, Shh allows the formation of a ventral telencephalic subdivision by inhibiting the dorsalizing effects of Gli3. Both Foxg1 and Fgf8 are required to form the complete telencephalon.

By embryonic day 9 (E9), Foxg1 expression is contained in the telencephalic neuroepithelium, including the progenitor cells of the cerebral cortex, the basal ganglia and the olfactory bulb (50). At E9.5, Foxg1 expression declines in the dorsomedial telencephalon and the dorsal midline, though Foxg1 expression persists in the ventral telencephalon. At E12.5, Foxg1 is expressed in telencephalic neural progenitors and absent from the rest of the neural tube. Lastly, according to coronal sections of 4-month old mice brains, Foxg1 expression remains restricted to cells derived from the telencephalic neuroepithelium, including the cerebral cortex and the hippocampus.

FOXG1 Syndrome

FOXG1 syndrome is a rare neurodevelopmental disorder characterized by abnormal brain development and function due to mutations in one copy of FOXG1.

FOXG1 syndrome (OMIM #613454) was first thought to be a congenital variant of Rett Syndrome (RTT) with many overlapping features of typical RTT but with differences in disease onset and symptoms (51). The features of RTT generally include a rapid regression in language and motor skills between the ages of 6–18 months in which affected individuals demonstrate repetitive and stereotypic hand movements, severe intellectual disability (ID), and social impairment. Since the original description of RTT in 1966 (52) and its characterization in 1983 (53), a RTT diagnosis was based only on consensus clinical criteria until mutations in MECP2 were identified in almost all classical RTT cases (54). As a result, RTT patients were characterized as having typical RTT if they fit the consensus criteria or atypical RTT if they had the congenital form (51, 55).

The FOXG1 gene was first implicated in the congenital form of RTT in 2005, when a 7-year old girl with a 720-kb inversion in chromosome 14q12 disrupting FOXG1 was identified (56). The affected girl displayed severe ID, tetraplegia, and structural brain abnormalities including microcephaly, myelination defects, and agenesis of the corpus callosum. Soon afterwards, clinical reports of children with facial dysmorphisms, microcephaly, and ID were identified with 14q12 interstitial deletions overlapping FOXG1 (57, 58). Other reports of atypical RTT associated FOXG1 as the causal gene following the discovery of interstitial 14q12 de novo deletions in patients with no observable MECP2 mutations (59–61). From these findings, FOXG1 was recognized as a strong candidate gene for the syndrome, due to its high expression in the developing brain and the reported developmental abnormalities in the telencephalon of both heterozygous and homozygous mouse mutants (62, 63). Since then, retrospective molecular screenings for FOXG1 mutations were done in large cohorts of typical and atypical RTT patients (64–66). These screens of RTT patients with no mutations in MECP2 later identified non-sense, frameshift, and missense mutations in FOXG1.

FOXG1 Dose and Cell Survival

In the developing brain, neural stem cells (NSCs) are controlled by a tightly regulated series of signals that coordinate proliferation and differentiation into different neural cell types (neurons, astrocytes, and oligodendrocytes) that ultimately populate the mature brain (67). NSCs are defined as self-renewing, multipotent cells that generate neurons, astrocytes, and oligodendrocytes. Neural progenitor cells (NPCs) have a limited life span, less self-renewal capacity, and may be multipotent or unipotent (68, 69). Subventricular zone NSCs first divide symmetrically to expand the population of ventricular zone progenitor cells then switch to divide asymmetrically (67). Asymmetric cell division gives rise to a progenitor cell and radial glia or neurons which migrate and form the cortical layers.

NSCs must continually counterbalance pro-death and pro-survival signals to ensure the appropriate numbers of cells in the progenitor pool and the developing cortex (70–73). Mediators of these processes can either increase or decrease cell-death signals or increase or decrease pro-survival signals. Cell death involves a strictly regulated series of events and is an essential aspect of an organism's life. The controlled nature of the initiation, execution, and termination of the cell death process is commonly referred to as apoptosis (71). Apoptosis is a series of specific biochemical and morphological changes that lead to the degradation of cells and their contents in a controlled manner. The distinguishable morphological features of apoptosis include chromatin condensation, nuclear fragmentation, cytoplasmic condensation, membrane blebbing, and nucleus, and inter-nucleosomal cleavage of DNA (74–76). Toward the end of the process, the apoptotic cell is converted into membrane-bound fragments called apoptotic bodies which are quickly eliminated via phagocytosis (77, 78). The caspases are major mediators of this process in that they perform the controlled demolition of cell components (79).

The tight regulation of NSC apoptosis will have a dramatic effect on the final size of the NSC pool (72). This should be distinguished from the more widely studied form of cell or synaptic pruning of projection neurons during neurodevelopment. At the early stages of embryogenesis, large-scale apoptosis occurs in the brain, eliminating a majority of the newly generated neuronal population following neurogenesis (70). This is also demonstrated in the proliferative regions of adult brain, the subventricular zone (SVZ) and dentate gyrus (DG) (80–82).

How might dosage of FOXG1 affect control NSC apoptosis? Caspases exist in the cell as inactive procaspase monomers that need to dimerize to be active, and do this in response to signaling cues (83). Active caspase assembly involves specific adapter proteins, and the amount of dimerized active caspases results in a positive feedback loop to activate other caspases (79). Given that the total number of active caspases determines outcome and caspases can be regulated at the procaspase and dimerization level, one could imagine a situation where FOXG1 either regulates the expression of a negative regulator of these factors or that FOXG1 protein can interact and inhibit caspase dimerization. There are no studies to our knowledge on direct or indirect effects of FOXG1 on caspase regulation. However, this model provides an example of how dose could lead to dramatic effects on apoptosis.

Complete Loss of Foxg1

Mice with a homozygous loss of Foxg1 display severe abnormalities in telencephalon development and die shortly after birth (5, 84). In particular, the telencephalon from Foxg1 null mice are significantly smaller than normal from E10.5 to perinatal death (6). The Foxg1 null telencephalon is also enriched for dorsal markers while ventral cell fates are not (5, 33, 40, 50, 85, 86). Dorsal telencephalic neuroepithelial cells also differentiate prematurely, leading to the early depletion of neural progenitors. These results suggest that Foxg1 controls the morphogenesis of the telencephalon by regulating the rate of neuroepithelial cell proliferation and the timing of neuronal differentiation (5, 84). One study examined the outcome of homozygous loss-of-function Foxg1 models by making a DNA binding defective version of the gene called BF1NHAA (86). The authors suggest that this led to reduced proliferation and precocious differentiation of Foxg1-deficient neural progenitors (86). Conditional deletion of Foxg1 from pyramidal neurons (selective deletion using CRE/LoxP system driven by NeuroD) (87) showed that in Foxg1-cKO (conditional KO) the cortex was substantially thinner, the ventricles were enlarged, and the intermediate zone was not well-defined at postnatal day 0 (P0). Lastly, the corpus callosum was missing throughout the anterior-posterior axis, and the hippocampus failed to develop in Foxg1-cKO mice (87). The authors suggest an important signaling complex for projection neurons that may be important in corpus callosum formation including Znf513, Slit3, Reelin, and Robo1.

Other models of complete loss of Foxg1 have also been investigated. In a homozygous knockout neuronal cell line, embryoid bodies (EBs) derived from induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) were significantly smaller (88), supporting a role for Foxg1 in cell survival. In vivo adult neurogenesis models support this finding. (89) conditionally ablated Foxg1 to create homozygous knockouts specifically in the dentate gyrus. They used a tamoxifen inducible, Frizzled9 Cre/LoxP approach for this and show almost complete loss of subgranular zone cells. Apoptosis occurred as early as half a day following Foxg1 deletion with cell death persisting until at least P7. There was a significant decrease in the number of postmitotic neurons at P14 which was attributed to increased cell death following postnatal Foxg1 ablation rather than impaired neurogenesis in the DG.

Complete loss of Foxg1 can be considered an extreme version of a loss of gene dosage, though in cases of complete loss it is difficult to argue that gene dosage matters (there are several syndromes in human that require complete loss of a gene product, e.g., some recessive disorders, and where loss of one allele has no effect). For this, we require an investigation into models with increased dose of FoxG1 and reduced, but not absent FoxG1.

Increased Dose of FoxG1 and Cell Survival

FoxG1 Over-expression in Chick and Xenopus

In cranial neural tube slices of White Leghorn chick embryos, Ahlgren et al. (85) performed retroviral gene transfer to overexpress the avian homolog of FoxG1, V-qin, in the telencephalon and to ectopically express it in the mesencephalon, rhombencephalon, and spinal cord (85). The ectopic expression of FoxG1 resulted in a selective overgrowth of the telencephalon and mesencephalon (midbrain) but not in more posterior brain regions. As well, there was a marked thickening of the neuroepithelium. Interestingly, a separate experiment demonstrated that retroviral expression of FoxG1NHR−AAA (virus containing the FoxG1 construct with the DNA binding domain inactivated) resulted in no observable phenotype. This finding suggested that the brain overgrowth is mediated through the DNA-binding domain of FoxG1 (85). Ahlgren et al. (85) concluded that the observed overgrowth was not due to an increase in proliferation rates (85). Embryos examined 2–3 days after retroviral infection demonstrated no significant increase in BrdU incorporation in the neural tube. Similarly, there was no detectable effect of FoxG1NHR−AAA on proliferation as measured by BrdU or mitotic index (85). Rather than uncontrolled proliferation, Ahlgren et al. suggested that the absence of normal programmed cell death was associated with the brain overgrowth observed in FoxG1 overexpressing chicks (85). The authors used DAPI as an indicator of apoptotic nuclei and observed that dying cells appeared small and bright. Cellular counts revealed a significant decrease in the number of apoptotic nuclei in the anterior neural tube including both the telencephalon and mesencephalon. Furthermore, control retroviruses and FoxG1NHR−AAA did not yield a significant change in the apoptotic index compared to embryos with no virus infection.

In Xenopus laevis embryos in which FoxG1 (known as XBF-1) is overexpressed, studies revealed an expansion of the telencephalic progenitor population (90, 91). According to Hardcastle and Papalopulu, embryos injected with a high XBF-1 concentration show increased proliferation over an area of expanded or ectopic neuroectoderm, such that the normally bilayered neuroectoderm becomes multilayered (91). XBF-1 injected embryos also demonstrated proliferating neural precursor cells in lateral domains where post-mitotic cells would normally be found. Overall, the authors show that a high dose of XBF-1 causes tissue outgrowths in the ectoderm, increases proliferation, and inhibits the expression of the cyclin-dependent kinase (cdk) inhibitor p27XIC (91). Bourguignon et al. demonstrated that neuronal differentiation is specifically suppressed in cells in which XBF-1 is expressed at high levels (90). This was seen also via the thickening of the ectoderm in developing Xenopus models as well as through an increase in the number of proliferating progenitor cells in place of differentiated neurons in the anterior neural plate (90). These studies support a model whereby increased XBF-1 leads to more proliferation of precursor cells possibly through suppression of neuron differentiation.

Duplication of FOXG1 in Human Populations

“Natural” experiments exist in humans whereby mutations have arisen on chromosome 14q12 where FOXG1 is duplicated leading to three gene copies instead of two. Pontrelli and others recently reviewed 15 cases with duplications on chromosome 14q12 all of which included FOXG1 (92), where epilepsy and cognitive impairment with dysmorphic features are the common phenotypes of this cohort. There was no identifiable microcephaly, though there is also no macrocephaly, arguing against a simple balanced model of FOXG1 to drive proliferation, at least in human. Some amount of FOXG1 may be required to ensure enough progenitor cells are made. Too much FOXG1 however, may not affect this specific process which may involve an interaction with specific proteins that govern the generation of progenitor cells. The epilepsy and intellectual disability phenotypes in the duplication cases may arise from completely different mechanisms than from loss of FOXG1 dosage, i.e., the interaction of FOXG1 with different molecules or with different genomic regions.

Increase of FOXG1 in Human Tumors and Neurodevelopmental Disease Associated With Macrocephaly

Cancers are broadly defined as a group of diseases that involve abnormal cell growth with the potential to invade or spread to other parts of the body. Tumors are large masses that are often the result of this abnormal growth of cells. Resistance to cell death is an important feature of cancers, where apoptosis has been established as a mechanism of anti-cancer defense. Gliomas are a common form of brain cancer characterized by excessive cell proliferation and aggressive infiltration (93). Notably, FOXG1 has been shown to be upregulated in glioma as well as ovarian cancer and medulloblastoma (94–96), and to have important driver effects. To examine the role of FOXG1 in glioma, Chen et al. examined FOXG1 expression in two cultured glioma cell lines (U87MG and SHG44) and found elevated FOXG1 expression in U87MG cells (93). A lentivirus-mediated expression system was used to overexpress FOXG1 in SHG44 cells and a lentivirus-mediated shRNA was used to knock down FOXG1 in U87MG. The results of these expression studies demonstrated that cell proliferation was decreased as a function of downregulated FOXG1. Similarly, increased cell proliferation was associated with increased FOXG1 expression. The authors further questioned whether the change in the proliferation rate was attributed to altered apoptotic activity. In FOXG1-overexpressing SHG44 cells, apoptosis appeared to be reduced given by the decreased expression of caspase-9, 8 and 3 and the cleaved versions of these pro-apoptotic proteins. Furthermore, expression of these caspases was elevated in the FOXG1 knockdown U87MG cells, indicating increased apoptotic activity. Together, these results suggest that FOXG1 has a pro-survival function and that expression is negatively correlated with glioma cell apoptosis (93).

Given the purported pro-proliferation and anti-differentiation activity of FOXG1, a study by Wang et al. (97) hypothesized that FOXG1 expression supported the resistance of glioblastoma multiforme (GBM) cells against temozolomide (TMZ) treatment. TMZ is a DNA methylation agent and drug resistance-modifying agent that induces G2/M arrest and apoptosis. Upon TMZ treatment, viability of GBM cells was assessed using an MTT assay (apoptotic assay) which demonstrated significantly reduced cell viability—defined as the ratio of initial cell number minus dead cell number to the initial cell number (97). GBM cells transiently overexpressing FOXG1 in combination with TMZ treatment showed significantly improved cell viability, indicating that FOXG1 resisted the anti-proliferation ability of TMZ treatment (97).

In a smaller study, Adesina et al. (98) demonstrated that FOXG1 is significantly differentially overexpressed in aggressive medulloblastoma subtypes from four publicly available gene expression profiling data sets. As a result, the authors attempted to examine the genome-wide effect of down-regulating FOXG1 expression in DAOY (a medulloblastoma cell line) by running an mRNA expression profile of 44,000 genes using the shFOXG1, shLuciferase, and the UT DAOY cell lines. Whole-genome expression analyses revealed pathways affected by decreased FOXG1 including those involved in cell adhesion and migration (98). As expected, changes in expression were seen in genes previously implicated in cancer. There also appeared to be a variety of altered genes involved in cell survival or anti-apoptotic activity (98). In a separate experiment, the authors demonstrated that mice xenografts injected with DAOY cells demonstrated enhanced survival when transfected with shFOXG1 knockdown constructs as opposed to sh-Luciferase. Overall, these studies offer evidence for the overexpression of FOXG1 in mediating excessive cell survival in glioma and medulloblastoma, respectively (93, 98).

Idiopathic autism spectrum disorder refers to individuals where no underlying cause for the disorder has been identified. (99) suggest that FOXG1 may act as a convergence point for these ASDs associated with macrocephaly and modeled these patients in human stem cells. Gene expression profiling of neurons derived from different patient lines revealed that overexpression of FOXG1 was ubiquitous in their transcriptomic profiles. The authors also observed an excitatory/inhibitory neuron imbalance in brain organoids generated from proband iPSCs, such that FOXG1 may be partially involved in the overproduction GABAergic neurons.

Studies from model organisms, human duplication cases, neurodevelopmental disorders with macrocephaly and no mutation in FOXG1, and human tumors suggest that cell survival and tissue growth are sensitive to FOXG1 gene dosage. Tipping the balance of FOXG1 toward overexpression leads to a reduction in cell death and tissue overgrowth. Brain overgrowth and tumor formations are logical consequences of FoxG1 overexpression as its role in promoting proliferation and cell survival are amplified beyond normal levels. This idea needs to be tempered with the results from the human duplication cases where no brain overgrowth was observed (92), arguing against a simple FOXG1 dosage model. While the data do support a FOXG1 dosage sensitive model in brain cells, it may be that the mechanism important in reduced dosage of FOXG1 operates on different molecules than those that are important where there is too much FOXG1, something we call an asymmetric dosage sensitivity model.

Heterozygous Models of FOXG1 Syndrome

Foxg1+/− Mouse Models

Foxg1 heterozygous mice were first generated while making Foxg1 homozygous KO mice and were considered as controls (i.e., before the human heterozygous deletion syndrome was identified, highlighting the importance of heterozygotes). This was attributed to the fact that several initial studies reported that mice with a single allele of Foxg1 develop an apparently normal cerebral cortex (5, 33, 50, 86, 100). Foxg1 heterozygous mice did not exhibit the severe cortical defects in patterning observed in the null mice (100), at least on cursory observation. Closer investigation of Foxg1+/− mice identified smaller cortical volumes and Foxg1 heterozygous mice showed a reduction in layer II/III thickness associated with microcephaly and impaired hippocampal neurogenesis (62, 101). The Foxg1+/− model also showed hyperlocomotion, impaired habituation in the open field and a severe deficit in contextual fear conditioning (62, 63, 101). The cerebral cortex, hippocampus and striatum were observed to have reduced volumes in the Foxg1+/− mice (62, 63), though this may be strain or genetic background dependent. For example, the forebrain of heterozygous Foxg1 mice maintained on the C57BL/6J background had severely impaired development. However, Foxg1+/− mice of the Foxg1-tet line and Foxg1-lacZ and Foxg1-cre mice maintained on a mixed background, did not display reduced cortical thickness. This suggests that reduced but not absent Foxg1 in mice displays complex interactions with brain development.

Heterozygous Loss of FOXG1 in Humans

Clinical data on several FOXG1 deletion syndrome patients have been reviewed and discussed in this review; however, understanding why a loss or mutation in one copy of FOXG1 leads to microcephaly and severe intellectual disability in humans is unknown. Human-derived iPSCs now make it feasible to generate isogenic, patient-derived neurons to investigate neurodevelopment and to perform functional genetic studies (102). Patriarchi et al. generated iPSC-derived neurons from FOXG1+/− patients and suggested that there is an imbalance in excitatory/inhibitory (E/I) synaptic protein expression in patient neurons compared to controls (103). However, these data do not explore the dynamics of FOXG1 dose as neurons develop. It seems reasonable to suspect that the molecular mechanism of disease will arise early on as cells differentiate and any overt cellular phenotype at a mature cell stage is a passenger effect to an earlier problem in cell differentiation. It is these early molecular mechanisms that need to be assessed to understand how FOXG1 dose leads to a reproducible, robust cellular phenotype. To this end, a recent study was able to generate human stem cells where FOXG1 dose could be fine-tuned (104). Studies such as these will become important in titrating specific doses at specific times for in vitro neurodevelopment.

Binding Partners That May Mediate FOXG1 Dosage Effects

FOXG1 dose appears to be critical for the proper differentiation or proliferation of specific cell types. One way that protein levels (dose) can exert its effects is by binding to other molecules. Dose effects can be revealed by the need to compete with other proteins to interact with a given protein or protein complex. The reduced amount of FOXG1 may allow a protein complex to perform different functions, whereas too much may allow FOXG1 to outcompete other proteins for binding sites where it has lower affinity.

Groucho (Gro)/Transducin-Like Enhancer of Split (TLE)

FoxG1 is known to interact directly with Groucho (Gro)/Transducin-like enhancer of split-1 (TLE1) by forming a transcription repression complex with co-repressors of the TLE family (105, 106). TLE family members are transcriptional repressors that lack a DNA binding motif and so are dependent on other factors for this function, like Foxg1. Among mammals, there are four full-length TLE family members (TLE1-4) and two shorter isoforms–Groucho-related gene product (Grg) 5 and 6. Only full-length TLE and Grg6 proteins contain a conserved C-terminal WD40 repeat domain mediating interaction with FoxG1. Grg6 acts as a dominant-negative regulator of FoxG1:TLE transcriptional repressor complexes (107). Grg6 interferes with the binding of TLE1 to FoxG1 and does not repress transcription when targeted to DNA. Moreover, co-expression of Grg6 and FoxG1 in cortical progenitor cells leads to a decrease in the number of proliferating cells and increased neuronal differentiation (107). Furthermore, Roth et al. show that Xenopus tropicalis TLE2 (a closely related family member to TLE1) physically interacts with FoxG1 in the ventral telencephalon (subpallium) (108) via a conserved N-terminal Engrailed Homology 1 (EH1) motif. Knocking down TLE2 leads to impaired development of the ventral telencephalon, similar to the knockdown of FoxG1. This suggests that TLE2 is a spatially restricted member of the Groucho/TLE family, which interacts with FoxG1 to specify and promote the development of the ventral telencephalon. The dynamic interplay of TLE and Grg proteins shows just how dynamic altering the total level of Foxg1 protein could be. The binding affinities of each would be critical to determining outcome, and suggest that a simple linear model (more expression of FOXG1 = more binding with TLE) is not necessarily correct.

Lysine Demethylase 5B (KDM5B)

FOXG1 cooperates with KDM5B (previously JARID1B or PLU-1), a histone demethylase, to potentially regulate cell proliferation and differentiation. The interaction between KDM5B and FOXG1 is mediated by a conserved interacting motif (Ala-X-Ala-Ala-X-Val-Pro-X4-Val-Pro-X8-Pro; termed the VP motif) in both proteins (109). The interaction between FOXG1 and the transcriptional repressor KDM5B is of functional importance for early brain development (110). In particular, during mouse embryogenesis, KDM5B expression overlaps with FOXG1 expression both spatially and temporally (111). While the two interact directly, KDM5B also acts as a repressor of FOXG1 expression (112). KDM5B then can both regulate the expression of FOXG1 and bind to FOXG1 protein, possibly forming important regulatory loops. Dosage change in FOXG1 would thus have important consequences on the activities of KDM5B.

KDM5B is an H3K4 demethylase (mono-, di-, and tri-), and therefore has a role in removing an important mark of actively transcribed regions. KDM5B is classified as a repressive chromatin writer and so loss of function would lead to a more permissive (i.e., more gene expression) chromatin state. KDM5B is predominantly expressed during embryonic development, including embryonic stem cells (ESCs) and also the adult brain, testis, eye, spleen and thymus (111–113). It has also been identified as an oncogene in many cancer types (114). This suggests that while it is essential for normal development, any perturbation to gene expression may induce abnormal phenotypes related to growth and survival.

Polycomb Complex Protein BMI-1 (BMI-1)

FOXG1 and BMI-1 expression levels are tightly correlated with each other in a close expression loop to affect neural progenitor cell survival (115). BMI-1 is part of the polycomb repressive complex 1, a transcriptional repressor complex known to interact with multiple proteins (116). PRC1 is thought to repress gene expression by affecting the level of histone H2A variants in nucleosomes (117), levels of which determine the stem-like state of a cell. While FOXG1 and BMI-1 may not physically interact, their tight regulatory relationship might suggest that the proper dose of FOXG1 is important for PRC1-mediated gene repression in nerve cells, perhaps as a proper guide to the correct genomic coordinates.

Signaling Mechanisms that May Contribute to or Be Affected by FoxG1 Dosage

FGF8 Signaling

FGF8 is thought to directly affect FOXG1 during neurodevelopment to specify and pattern the ventral telencephalon (40, 84, 118). FGF8 is a morphogen meaning it derives its function from amount or concentration along a specific gradient. Morphogens are an appealing model to explain why FOXG1 dose may be important since more or less FOXG1 might lead to more or less FGF8, or vice versa. At neural plate stages, Fgf8 induces and/or maintains Foxg1 expression in the anterior neural ridge (119). Foxg1 then restricts the expression of Bmp4 to the midline where BMP4 is believed to induce apoptosis. Analysis of serial sections of forebrains from normal, Fgf8 function eliminated, and Fgf8 function reduced animals confirmed that the Foxg1 and Bmp4 expression domains in the midline were complementary. These observations support the hypothesis that FGF8 regulates telencephalic cell survival in part via a Foxg1 pathway and that either eliminating or increasing Fgf8 expression decreases Foxg1 pathway activity; whereby reducing Fgf8 expression increases it (119).

PI3K-Akt Signaling

The PI3K (phosphatidylinositide-3′-OH kinase)-Akt pathway (120) promotes neuronal survival by inactivating the cell death machinery and repressing pro-apoptotic gene expression (121, 122), likely through IGF-1 (123). This signaling cascade activates CK1 and AKT, both of which can target FOXG1 (122). Foxg1 may be imported into the nucleus of cells through its phosphorylation by CKI which promotes NPC differentiation into neurons, while Foxg1 phosphorylation by Akt at Thr271 leads to Foxg1 nuclear export. Loss of FOXG1 dose may mean there are less FOXG1 targets available to be phosphorylated and that a critical mass of FOXG1 may need to be phosphorylated for AKT to execute its cellular programming.

TGF-β Signaling

The transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) pathway consists of multiple cytokines that control a wide variety of biological activities including apoptosis, cell proliferation, differentiation, cell adhesion, and embryonic development through TGF-β and other receptors and Smad transducer proteins (124, 125). Studies have shown that FoxG1 may act as a negative regulator of TGF-β signaling pathway by binding to the MH2 of Smads -1, -2, -3, and -4 (96, 126). This association blocks the binding of Smad proteins to DNA and results in the inhibition of TGF-β signaling (127). FoxG1 has been shown to inhibit expression of the cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK) inhibitor p21WAF1/CIP1, which is normally transcriptionally activated by TGF-β signaling, in glioblastoma and the neuroepithelium (96, 128). While TGF-β signaling is complex and context dependent, some of the effects of decreased FOXG1 dose could be exerted through its interactions with the SMAD proteins.

Conclusion

Altering FOXG1 dose leads to severe consequences in different cell types though this may be through asymmetric mechanisms. In this review, we have shown the results across different systems of increased or decreased FOXG1 dosage, as well as the different binding partners or signaling systems that may explain why dosage is important. These data support a non-linear model whereby FOXG1 interactions with different players may be governed by substrate affinity or phosphorylation states, arguing against any simplistic model of FOXG1 dose. How and when FOXG1 is expressed, how FOXG1 is stabilized or degraded, and background genetics will all be important determinants of the effects of FOXG1 gain or loss on brain development.

Author Contributions

NH and CE both evaluated the scientific literature and wrote the review together.

Funding

NH was funded by the Fonds de la recherche en santé du Québec (FRQS) doctoral fellowship. CE was funded by grants from the Canadian Institute of Health Research and a Canada Research Chair award.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

1. Mukherjee O, Acharya S, Rao M. Making NSC and neurons from patient-derived tissue samples. Methods Mol Biol. (2019) 1919:9–24. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-9007-8_2

2. Rakic P. Evolution of the neocortex: a perspective from developmental biology. Nat Rev Neurosci. (2009) 10:724–35. doi: 10.1038/nrn2719

3. Kaestner KH, Knochel W, Martinez DE. Unified nomenclature for the winged helix/forkhead transcription factors. Genes Dev. (2000) 14:142–6. doi: 10.1101/gad.14.2.142

4. Toresson H, Martinez-Barbera JP, Bardsley A, Caubit X, Krauss S. Conservation of BF-1 expression in amphioxus and zebrafish suggests evolutionary ancestry of anterior cell types that contribute to the vertebrate telencephalon. Dev Genes Evol. (1998) 208:431–9. doi: 10.1007/s004270050200

5. Xuan S, Baptista CA, Balas G, Tao W, Soares VC, Lai E. Winged helix transcription factor BF-1 is essential for the development of the cerebral hemispheres. Neuron. (1995) 14:1141–52. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90262-7

6. Florian C, Bahi-Buisson N, Bienvenu T. FOXG1-related disorders: from clinical description to molecular genetics. Mol Syndromol. (2012) 2:153–63. doi: 10.1159/000327329

7. Chess A. Monoallelic gene expression in mammals. Annu Rev Genet. (2016) 50:317–27. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genet-120215-035120

8. Gimelbrant A, Hutchinson JN, Thompson BR, Chess A. Widespread monoallelic expression on human autosomes. Science. (2007) 318:1136–40. doi: 10.1126/science.1148910

9. Zarrei M, MacDonald JR, Merico D, Scherer SW. A copy number variation map of the human genome. Nat Rev Genet. (2015) 16:172–83. doi: 10.1038/nrg3871

10. Prandini P, Deutsch S, Lyle R, Gagnebin M, Delucinge Vivier C, Delorenzi M, et al. Natural gene-expression variation in Down syndrome modulates the outcome of gene-dosage imbalance. Am J Hum Genet. (2007) 81:252–63. doi: 10.1086/519248

11. Belichenko NP, Belichenko PV, Kleschevnikov AM, Salehi A, Reeves RH, Mobley WC. The “Down syndrome critical region” is sufficient in the mouse model to confer behavioral, neurophysiological, and synaptic phenotypes characteristic of Down syndrome. J Neurosci. (2009) 29:5938–48. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1547-09.2009

12. Huen J, Kakihara Y, Ugwu F, Cheung KL, Ortega J, Houry WA. Rvb1-Rvb2: essential ATP-dependent helicases for critical complexes. Biochem Cell Biol. (2010) 88:29–40. doi: 10.1139/O09-122

13. Ikura T, Ogryzko VV, Grigoriev M, Groisman R, Wang J, Horikoshi M, et al. Involvement of the TIP60 histone acetylase complex in DNA repair and apoptosis. Cell. (2000) 102:463–73. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)00051-9

14. Park J, Wood MA, Cole MD. BAF53 forms distinct nuclear complexes and functions as a critical c-Myc-interacting nuclear cofactor for oncogenic transformation. Mol Cell Biol. (2002) 22:1307–16. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.5.1307-1316.2002

15. Coe BP, Stessman HAF, Sulovari A, Geisheker MR, Bakken TE, Lake AM, et al. Neurodevelopmental disease genes implicated by de novo mutation and copy number variation morbidity. Nat Genet. (2019) 51:106–16. doi: 10.1038/s41588-018-0288-4

16. Weigel D, Jackle H. The fork head domain: a novel DNA binding motif of eukaryotic transcription factors? Cell. (1990) 63:455–6. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90439-L

17. Clark KL, Halay ED, Lai E, Burley SK. Co-crystal structure of the HNF-3/fork head DNA-recognition motif resembles histone H5. Nature. (1993) 364:412–20. doi: 10.1038/364412a0

18. Miller LM, Gallegos ME, Morisseau BA, Kim SK: lin-31 a Caenorhabditis elegans HNF-3/fork head transcription factor homolog specifies three alternative cell fates in vulval development. Genes Dev. (1993) 7:933–47. doi: 10.1101/gad.7.6.933

19. Weigel D, Jackle H. Novel homeotic genes in Drosophila melanogaster. Biochem Cell Biol. (1989) 67:393–6. doi: 10.1139/o89-063

20. Strahle U, Blader P, Henrique D, Ingham PW. Axial, a zebrafish gene expressed along the developing body axis, shows altered expression in cyclops mutant embryos. Genes Dev. (1993) 7:1436–46. doi: 10.1101/gad.7.7b.1436

21. Knochel S, Lef J, Clement J, Klocke B, Hille S, Koster M, et al. Activin A induced expression of a fork head related gene in posterior chordamesoderm (notochord) of Xenopus laevis embryos. Mech Dev. (1992) 38:157–65. doi: 10.1016/0925-4773(92)90007-7

22. Sasaki H, Hogan BL. Differential expression of multiple fork head related genes during gastrulation and axial pattern formation in the mouse embryo. Development. (1993) 118:47–59.

23. Hromas R, Moore J, Johnston T, Socha C, Klemsz M. Drosophila forkhead homologues are expressed in a lineage-restricted manner in human hematopoietic cells. Blood. (1993) 81:2854–9. doi: 10.1182/blood.V81.11.2854.bloodjournal81112854

24. Golson ML, Kaestner KH. Fox transcription factors: from development to disease. Development. (2016) 143:4558–70. doi: 10.1242/dev.112672

25. Hannenhalli S, Kaestner KH. The evolution of Fox genes and their role in development and disease. Nat Rev Genet. (2009) 10:233–40. doi: 10.1038/nrg2523

26. Kumamoto T, Hanashima C. Evolutionary conservation and conversion of Foxg1 function in brain development. Dev Growth Differ. (2017) 59:258–69. doi: 10.1111/dgd.12367

27. Kaestner KH, Lee KH, Schlondorff J, Hiemisch H, Monaghan AP, Schutz G. Six members of the mouse forkhead gene family are developmentally regulated. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. (1993) 90:7628–31. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.16.7628

28. Pauley S, Lai E, Fritzsch B. Foxg1 is required for morphogenesis and histogenesis of the mammalian inner ear. Dev Dyn. (2006) 235:2470–82. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20839

29. Bredenkamp N, Seoighe C, Illing N. Comparative evolutionary analysis of the FoxG1 transcription factor from diverse vertebrates identifies conserved recognition sites for microRNA regulation. Dev Genes Evol. (2007) 217:227–33. doi: 10.1007/s00427-006-0128-x

30. Wiese S, Murphy DB, Schlung A, Burfeind P, Schmundt D, Schnulle V, et al. The genes for human brain factor 1 and 2, members of the fork head gene family, are clustered on chromosome 14q. Biochim Biophys Acta. (1995) 1262:105–12. doi: 10.1016/0167-4781(95)00059-P

31. Li J, Chang HW, Lai E, Parker EJ, Vogt PK. The oncogene qin codes for a transcriptional repressor. Cancer Res. (1995) 55:5540–4.

32. Murphy DB, Wiese S, Burfeind P, Schmundt D, Mattei MG, Schulz-Schaeffer W, et al. Human brain factor 1, a new member of the fork head gene family. Genomics. (1994) 21:551–7. doi: 10.1006/geno.1994.1313

33. Hanashima C, Li SC, Shen L, Lai E, Fishell G. Foxg1 suppresses early cortical cell fate. Science. (2004) 303:56–9. doi: 10.1126/science.1090674

34. Kumamoto T, Toma K, Gunadi, McKenna WL, Kasukawa T, Katzman S, et al. Foxg1 coordinates the switch from nonradially to radially migrating glutamatergic subtypes in the neocortex through spatiotemporal repression. Cell Rep. (2013) 3:931–45. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2013.02.023

35. Manuel M, Martynoga B, Yu T, West JD, Mason JO, Price DJ. The transcription factor Foxg1 regulates the competence of telencephalic cells to adopt subpallial fates in mice. Development. (2010) 137:487–97. doi: 10.1242/dev.039800

36. Zaret KS, Mango SE. Pioneer transcription factors, chromatin dynamics, and cell fate control. Curr Opin Genet Dev. (2016) 37:76–81. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2015.12.003

37. Manuel MN, Martynoga B, Molinek MD, Quinn JC, Kroemmer C, Mason JO, et al. The transcription factor Foxg1 regulates telencephalic progenitor proliferation cell autonomously, in part by controlling Pax6 expression levels. Neural Dev. (2011) 6:9. doi: 10.1186/1749-8104-6-9

38. Danesin C, Peres JN, Johansson M, Snowden V, Cording A, Papalopulu N, et al. Integration of telencephalic Wnt and hedgehog signaling center activities by Foxg1. Dev Cell. (2009) 16:576–87. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.03.007

39. Hebert JM. Unraveling the molecular pathways that regulate early telencephalon development. Curr Top Dev Biol. (2005) 69:17–37. doi: 10.1016/S0070-2153(05)69002-3

40. Hebert JM, Fishell G. The genetics of early telencephalon patterning: some assembly required. Nat Rev Neurosci. (2008) 9:678–85. doi: 10.1038/nrn2463

41. Rallu M, Machold R, Gaiano N, Corbin JG, McMahon AP, Fishell G. Dorsoventral patterning is established in the telencephalon of mutants lacking both Gli3 and Hedgehog signaling. Development. (2002) 129:4963–74.

42. Sur M, Rubenstein JL. Patterning and plasticity of the cerebral cortex. Science. (2005) 310:805–10. doi: 10.1126/science.1112070

43. Wilson SW, Houart C. Early steps in the development of the forebrain. Dev Cell. (2004) 6:167–81. doi: 10.1016/S1534-5807(04)00027-9

44. Ericson J, Muhr J, Jessell TM, Edlund T. Sonic hedgehog: a common signal for ventral patterning along the rostrocaudal axis of the neural tube. Int J Dev Biol. (1995) 39:809–16.

45. Furuta Y, Piston DW, Hogan BL. Bone morphogenetic proteins (BMPs) as regulators of dorsal forebrain development. Development. (1997) 124:2203–12.

46. Lee SM, Tole S, Grove E, McMahon AP. A local Wnt-3a signal is required for development of the mammalian hippocampus. Development. (2000) 127:457–67.

47. Walshe J, Mason I. Unique and combinatorial functions of Fgf3 and Fgf8 during zebrafish forebrain development. Development. (2003) 130:4337–49. doi: 10.1242/dev.00660

48. Shimamura K, Rubenstein JL. Inductive interactions direct early regionalization of the mouse forebrain. Development. (1997) 124:2709–18.

49. Danesin C, Houart C. A Fox stops the Wnt: implications for forebrain development and diseases. Curr Opin Genet Dev. (2012) 22:323–30. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2012.05.001

50. Dou CL, Li S, Lai E. Dual role of brain factor-1 in regulating growth and patterning of the cerebral hemispheres. Cereb Cortex. (1999) 9:543–50. doi: 10.1093/cercor/9.6.543

51. Neul JL, Kaufmann WE, Glaze DG, Christodoulou J, Clarke AJ, Bahi-Buisson N, et al. Rett syndrome: revised diagnostic criteria and nomenclature. Ann Neurol. (2010) 68:944–50. doi: 10.1002/ana.22124

52. Rett A. [On a unusual brain atrophy syndrome in hyperammonemia in childhood]. Wien Med Wochenschr. (1966) 116:723–6.

53. Hagberg B, Aicardi J, Dias K, Ramos O. A progressive syndrome of autism, dementia, ataxia, and loss of purposeful hand use in girls: Rett's syndrome: report of 35 cases. Ann Neurol. (1983) 14:471–9. doi: 10.1002/ana.410140412

54. Amir RE, Van den Veyver IB, Wan M, Tran CQ, Francke U, Zoghbi HY. Rett syndrome is caused by mutations in X-linked MECP2, encoding methyl-CpG-binding protein 2. Nat Genet. (1999) 23:185–8. doi: 10.1038/13810

55. Rolando S. Rett syndrome: report of eight cases. Brain Dev. (1985) 7:290–6. doi: 10.1016/S0387-7604(85)80030-9

56. Shoichet SA, Kunde SA, Viertel P, Schell-Apacik C, von Voss H, Tommerup N, et al. Haploinsufficiency of novel FOXG1B variants in a patient with severe mental retardation, brain malformations and microcephaly. Hum Genet. (2005) 117:536–44. doi: 10.1007/s00439-005-1310-3

57. Bisgaard AM, Kirchhoff M, Tumer Z, Jepsen B, Brondum-Nielsen K, Cohen M, et al. Additional chromosomal abnormalities in patients with a previously detected abnormal karyotype, mental retardation, and dysmorphic features. Am J Med Genet A. (2006) 140:2180–7. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.31425

58. Papa FT, Mencarelli MA, Caselli R, Katzaki E, Sampieri K, Meloni I, et al. A 3 Mb deletion in 14q12 causes severe mental retardation, mild facial dysmorphisms and Rett-like features. Am J Med Genet A. (2008) 146A:1994–8. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.32413

59. Ariani F, Hayek G, Rondinella D, Artuso R, Mencarelli MA, Spanhol-Rosseto A, et al. FOXG1 is responsible for the congenital variant of Rett syndrome. Am J Hum Genet. (2008) 83:89–93. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2008.05.015

60. Jacob FD, Ramaswamy V, Andersen J, Bolduc FV. Atypical Rett syndrome with selective FOXG1 deletion detected by comparative genomic hybridization: case report and review of literature. Eur J Hum Genet. (2009) 17:1577–81. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2009.95

61. Mencarelli MA, Kleefstra T, Katzaki E, Papa FT, Cohen M, Pfundt R, et al. 14q12 Microdeletion syndrome and congenital variant of Rett syndrome. Eur J Med Genet. (2009) 52:148–52. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmg.2009.03.004

62. Eagleson KL, Schlueter McFadyen-Ketchum LJ, Ahrens ET, Mills PH, Does MD, Nickols J, et al. Disruption of Foxg1 expression by knock-in of cre recombinase: effects on the development of the mouse telencephalon. Neuroscience. (2007) 148:385–99. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2007.06.012

63. Siegenthaler JA, Tremper-Wells BA, Miller MW. Foxg1 haploinsufficiency reduces the population of cortical intermediate progenitor cells: effect of increased p21 expression. Cereb Cortex. (2008) 18:1865–75. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhm209

64. Bahi-Buisson N, Nectoux J, Girard B, Van Esch H, De Ravel T, Boddaert N, et al. Revisiting the phenotype associated with FOXG1 mutations: two novel cases of congenital Rett variant. Neurogenetics. (2010) 11:241–9. doi: 10.1007/s10048-009-0220-2

65. Mencarelli MA, Spanhol-Rosseto A, Artuso R, Rondinella D, De Filippis R, Bahi-Buisson N, et al. Novel FOXG1 mutations associated with the congenital variant of Rett syndrome. J Med Genet. (2010) 47:49–53. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2009.067884

66. Philippe C, Amsallem D, Francannet C, Lambert L, Saunier A, Verneau F, et al. Phenotypic variability in Rett syndrome associated with FOXG1 mutations in females. J Med Genet. (2010) 47:59–65. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2009.067355

67. Chandwani MN, Creisher PS, O'Donnell LA. Understanding the role of antiviral cytokines and chemokines on neural stem/progenitor cell activity and survival. Viral Immunol. (2018) 32:15–24. doi: 10.1089/vim.2018.0091

68. Rotheneichner P, Lange S, O'Sullivan A, Marschallinger J, Zaunmair P, Geretsegger C, et al. Hippocampal neurogenesis and antidepressive therapy: shocking relations. Neural Plast. (2014) 2014:723915. doi: 10.1155/2014/723915

69. Sierra A, Martin-Suarez S, Valcarcel-Martin R, Pascual-Brazo J, Aelvoet SA, Abiega O, et al. Neuronal hyperactivity accelerates depletion of neural stem cells and impairs hippocampal neurogenesis. Cell Stem Cell. (2015) 16:488–503. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2015.04.003

70. Biebl M, Cooper CM, Winkler J, Kuhn HG. Analysis of neurogenesis and programmed cell death reveals a self-renewing capacity in the adult rat brain. Neurosci Lett. (2000) 291:17–20. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3940(00)01368-9

71. Chung KM, Yu SW. Interplay between autophagy and programmed cell death in mammalian neural stem cells. BMB Rep. (2013) 46:383–90. doi: 10.5483/BMBRep.2013.46.8.164

72. de la Rosa EJ, de Pablo F. Cell death in early neural development: beyond the neurotrophic theory. Trends Neurosci. (2000) 23:454–8. doi: 10.1016/S0166-2236(00)01628-3

73. Yadirgi G, Leinster V, Acquati S, Bhagat H, Shakhova O, Marino S. Conditional activation of Bmi1 expression regulates self-renewal, apoptosis, and differentiation of neural stem/progenitor cells in vitro and in vivo. Stem Cells. (2011) 29:700–12. doi: 10.1002/stem.614

74. Ameisen JC. On the origin, evolution, and nature of programmed cell death: a timeline of four billion years. Cell Death Differ. (2002) 9:367–93. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4400950

75. Kerr JF, Wyllie AH, Currie AR. Apoptosis: a basic biological phenomenon with wide-ranging implications in tissue kinetics. Br J Cancer. (1972) 26:239–57. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1972.33

76. Saraste A, Pulkki K. Morphologic and biochemical hallmarks of apoptosis. Cardiovasc Res. (2000) 45:528–37. doi: 10.1016/S0008-6363(99)00384-3

77. Reed JC. Mechanisms of apoptosis. Am J Pathol. (2000) 157:1415–30. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64779-7

78. Zimmermann KC, Bonzon C, Green DR. The machinery of programmed cell death. Pharmacol Ther. (2001) 92:57–70. doi: 10.1016/S0163-7258(01)00159-0

79. McIlwain DR, Berger T, Mak TW. Caspase functions in cell death and disease. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. (2013) 5:a008656. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a008656

80. Altman J, Das GD. Post-natal origin of microneurones in the rat brain. Nature. (1965) 207:953–6. doi: 10.1038/207953a0

81. Breunig JJ, Arellano JI, Macklis JD, Rakic P. Everything that glitters isn't gold: a critical review of postnatal neural precursor analyses. Cell Stem Cell. (2007) 1:612–27. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2007.11.008

82. Eriksson PS, Perfilieva E, Bjork-Eriksson T, Alborn AM, Nordborg C, Peterson DA, et al. Neurogenesis in the adult human hippocampus. Nat Med. (1998) 4:1313–7. doi: 10.1038/3305

83. Boatright KM, Renatus M, Scott FL, Sperandio S, Shin H, Pedersen IM, et al. A unified model for apical caspase activation. Mol Cell. (2003) 11:529–41. doi: 10.1016/S1097-2765(03)00051-0

84. Martynoga B, Morrison H, Price DJ, Mason JO. Foxg1 is required for specification of ventral telencephalon and region-specific regulation of dorsal telencephalic precursor proliferation and apoptosis. Dev Biol. (2005) 283:113–27. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2005.04.005

85. Ahlgren S, Vogt P, Bronner-Fraser M. Excess FoxG1 causes overgrowth of the neural tube. J Neurobiol. (2003) 57:337–49. doi: 10.1002/neu.10287

86. Hanashima C, Shen L, Li SC, Lai E. Brain factor-1 controls the proliferation and differentiation of neocortical progenitor cells through independent mechanisms. J Neurosci. (2002) 22:6526–36. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-15-06526.2002

87. Cargnin F, Kwon JS, Katzman S, Chen B, Lee JW, Lee SK. FOXG1 orchestrates neocortical organization and cortico-cortical connections. Neuron. (2018) 100:1083–96.e1085. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2018.10.016

88. Mall EM, Herrmann D, Niemann H. Murine pluripotent stem cells with a homozygous knockout of Foxg1 show reduced differentiation towards cortical progenitors in vitro. Stem Cell Res. (2017) 25:50–60. doi: 10.1016/j.scr.2017.10.012

89. Tian C, Gong Y, Yang Y, Shen W, Wang K, Liu J, et al. Foxg1 has an essential role in postnatal development of the dentate gyrus. J Neurosci. (2012) 32:2931–49. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5240-11.2012

90. Bourguignon C, Li J, Papalopulu N. XBF-1, a winged helix transcription factor with dual activity, has a role in positioning neurogenesis in Xenopus competent ectoderm. Development. (1998) 125:4889–900.

91. Hardcastle Z, Papalopulu N. Distinct effects of XBF-1 in regulating the cell cycle inhibitor p27(XIC1) and imparting a neural fate. Development. (2000) 127:1303–14.

92. Pontrelli G, Cappelletti S, Claps D, Sirleto P, Ciocca L, Petrocchi S, et al. Epilepsy in patients with duplications of chromosome 14 harboring FOXG1. Pediatr Neurol. (2014) 50:530–5. doi: 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2014.01.022

93. Chen J, Wu X, Xing Z, Ma C, Xiong W, Zhu X, et al. FOXG1 expression is elevated in glioma and inhibits glioma cell apoptosis. J Cancer. (2018) 9:778–83. doi: 10.7150/jca.22282

94. Adesina AM, Nguyen Y, Mehta V, Takei H, Stangeby P, Crabtree S, et al. FOXG1 dysregulation is a frequent event in medulloblastoma. J Neurooncol. (2007) 85:111–22. doi: 10.1007/s11060-007-9394-3

95. Chan DW, Liu VW, To RM, Chiu PM, Lee WY, Yao KM, et al. Overexpression of FOXG1 contributes to TGF-beta resistance through inhibition of p21WAF1/CIP1 expression in ovarian cancer. Br J Cancer. (2009) 101:1433–43. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605316

96. Seoane J, Le HV, Shen L, Anderson SA, Massague J. Integration of Smad and forkhead pathways in the control of neuroepithelial and glioblastoma cell proliferation. Cell. (2004) 117:211–23. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(04)00298-3

97. Wang L, Wang J, Jin T, Zhou Y, Chen Q. FoxG1 facilitates proliferation and inhibits differentiation by downregulating FoxO/Smad signaling in glioblastoma. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. (2018) 504:46–53. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2018.08.118

98. Adesina AM, Veo BL, Courteau G, Mehta V, Wu X, Pang K, et al. FOXG1 expression shows correlation with neuronal differentiation in cerebellar development, aggressive phenotype in medulloblastomas, and survival in a xenograft model of medulloblastoma. Hum Pathol. (2015) 46:1859–71. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2015.08.003

99. Mariani J, Coppola G, Zhang P, Abyzov A, Provini L, Tomasini L, et al. FOXG1-dependent dysregulation of GABA/glutamate neuron differentiation in autism spectrum disorders. Cell. (2015) 162:375–90. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.06.034

100. Hebert JM, McConnell SK. Targeting of cre to the Foxg1 (BF-1) locus mediates loxP recombination in the telencephalon and other developing head structures. Dev Biol. (2000) 222:296–306. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2000.9732

101. Shen L, Nam HS, Song P, Moore H, Anderson SA. FoxG1 haploinsufficiency results in impaired neurogenesis in the postnatal hippocampus and contextual memory deficits. Hippocampus. (2006) 16:875–90. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20218

102. Bell S, Maussion G, Jefri M, Peng H, Theroux JF, Silveira H, et al. Disruption of GRIN2B impairs differentiation in human neurons. Stem Cell Reports. (2018) 11:183–96. doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2018.05.018

103. Patriarchi T, Amabile S, Frullanti E, Landucci E, Lo Rizzo C, Ariani F, et al. Imbalance of excitatory/inhibitory synaptic protein expression in iPSC-derived neurons from FOXG1(+/–) patients and in foxg1(+/–) mice. Eur J Hum Genet. (2016) 24:871–80. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2015.216

104. Zhu W, Zhang B, Li M, Mo F, Mi T, Wu Y, et al. Precisely controlling endogenous protein dosage in hPSCs and derivatives to model FOXG1 syndrome. Nat Commun. (2019) 10:928. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-08841-7

105. Sonderegger CK, Vogt PK. Binding of the corepressor TLE1 to Qin enhances Qin-mediated transformation of chicken embryo fibroblasts. Oncogene. (2003) 22:1749–57. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206308

106. Yao J, Lai E, Stifani S. The winged-helix protein brain factor 1 interacts with groucho and hes proteins to repress transcription. Mol Cell Biol. (2001) 21:1962–72. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.6.1962-1972.2001

107. Marcal N, Patel H, Dong Z, Belanger-Jasmin S, Hoffman B, Helgason CD, et al. Antagonistic effects of Grg6 and Groucho/TLE on the transcription repression activity of brain factor 1/FoxG1 and cortical neuron differentiation. Mol Cell Biol. (2005) 25:10916–29. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.24.10916-10929.2005

108. Roth M, Bonev B, Lindsay J, Lea R, Panagiotaki N, Houart C, et al. FoxG1 and TLE2 act cooperatively to regulate ventral telencephalon formation. Development. (2010) 137:1553–62. doi: 10.1242/dev.044909

109. Cloos PA, Christensen J, Agger K, Helin K. Erasing the methyl mark: histone demethylases at the center of cellular differentiation and disease. Genes Dev. (2008) 22:1115–40. doi: 10.1101/gad.1652908

110. Tan K, Shaw AL, Madsen B, Jensen K, Taylor-Papadimitriou J, Freemont PS. Human PLU-1 Has transcriptional repression properties and interacts with the developmental transcription factors BF-1 and PAX9. J Biol Chem. (2003) 278:20507–13. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M301994200

111. Madsen B, Spencer-Dene B, Poulsom R, Hall D, Lu PJ, Scott K, et al. Characterisation and developmental expression of mouse Plu-1, a homologue of a human nuclear protein (PLU-1) which is specifically up-regulated in breast cancer. Mech Dev. (2002) 119(Suppl. 1):S239–46. doi: 10.1016/S0925-4773(03)00123-0

112. Dey BK, Stalker L, Schnerch A, Bhatia M, Taylor-Papidimitriou J, Wynder C. The histone demethylase KDM5b/JARID1b plays a role in cell fate decisions by blocking terminal differentiation. Mol Cell Biol. (2008) 28:5312–27. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00128-08

113. Frankenberg S, Smith L, Greenfield A, Zernicka-Goetz M. Novel gene expression patterns along the proximo-distal axis of the mouse embryo before gastrulation. BMC Dev Biol. (2007) 7:8. doi: 10.1186/1471-213X-7-8

114. Kuo YT, Liu YL, Adebayo BO, Shih PH, Lee WH, Wang LS, et al. JARID1B expression plays a critical role in chemoresistance and stem cell-like phenotype of neuroblastoma cells. PLoS ONE. (2015) 10:e0125343. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0125343

115. Fasano CA, Phoenix TN, Kokovay E, Lowry N, Elkabetz Y, Dimos JT, et al. Bmi-1 cooperates with Foxg1 to maintain neural stem cell self-renewal in the forebrain. Genes Dev. (2009) 23:561–74. doi: 10.1101/gad.1743709

116. Gil J, O'Loghlen A. PRC1 complex diversity: where is it taking us? Trends Cell Biol. (2014) 24:632–41. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2014.06.005

117. Wang H, Wang L, Erdjument-Bromage H, Vidal M, Tempst P, Jones RS, et al. Role of histone H2A ubiquitination in Polycomb silencing. Nature. (2004) 431:873–8. doi: 10.1038/nature02985

118. Storm EE, Garel S, Borello U, Hebert JM, Martinez S, McConnell SK, et al. Dose-dependent functions of Fgf8 in regulating telencephalic patterning centers. Development. (2006) 133:1831–44. doi: 10.1242/dev.02324

119. Storm EE, Rubenstein JL, Martin GR. Dosage of Fgf8 determines whether cell survival is positively or negatively regulated in the developing forebrain. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. (2003) 100:1757–62. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0337736100

120. Brunet A, Datta SR, Greenberg ME. Transcription-dependent and -independent control of neuronal survival by the PI3K-Akt signaling pathway. Curr Opin Neurobiol. (2001) 11:297–305. doi: 10.1016/S0959-4388(00)00211-7

121. Brunet A, Bonni A, Zigmond MJ, Lin MZ, Juo P, Hu LS, et al. Akt promotes cell survival by phosphorylating and inhibiting a Forkhead transcription factor. Cell. (1999) 96:857–68. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80595-4

122. Regad T, Roth M, Bredenkamp N, Illing N, Papalopulu N. The neural progenitor-specifying activity of FoxG1 is antagonistically regulated by CKI and FGF. Nat Cell Biol. (2007) 9:531–40. doi: 10.1038/ncb1573

123. Cheng CM, Reinhardt RR, Lee WH, Joncas G, Patel SC, Bondy CA. Insulin-like growth factor 1 regulates developing brain glucose metabolism. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. (2000) 97:10236–41. doi: 10.1073/pnas.170008497

124. Hu PP, Datto MB, Wang XF. Molecular mechanisms of transforming growth factor-beta signaling. Endocr Rev. (1998) 19:349–63. doi: 10.1210/edrv.19.3.0333

125. Massague J. TGF-beta signal transduction. Annu Rev Biochem. (1998) 67:753–91. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.67.1.753

126. Dou C, Lee J, Liu B, Liu F, Massague J, Xuan S, et al. BF-1 interferes with transforming growth factor beta signaling by associating with Smad partners. Mol Cell Biol. (2000) 20:6201–11. doi: 10.1128/MCB.20.17.6201-6211.2000

127. Rodriguez C, Huang LJ, Son JK, McKee A, Xiao Z, Lodish HF. Functional cloning of the proto-oncogene brain factor-1 (BF-1) as a Smad-binding antagonist of transforming growth factor-beta signaling. J Biol Chem. (2001) 276:30224–30. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M102759200

Keywords: FOXG1, BF-1, iPSCs, neurodevelopment, neural stem cell, gene dosage

Citation: Hettige NC and Ernst C (2019) FOXG1 Dose in Brain Development. Front. Pediatr. 7:482. doi: 10.3389/fped.2019.00482

Received: 01 March 2019; Accepted: 01 November 2019;

Published: 22 November 2019.

Edited by:

Jo Madeleine Wilmshurst, University of Cape Town, South AfricaReviewed by:

Andrea Domenico Praticò, University of Catania, ItalySalvatore Savasta, University of Pavia, Italy

Copyright © 2019 Hettige and Ernst. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Carl Ernst, Y2FybC5lcm5zdCYjeDAwMDQwO21jZ2lsbC5jYQ==

Nuwan C. Hettige

Nuwan C. Hettige Carl Ernst

Carl Ernst