- 1Discipline of Genetics, Victor Babeș University of Medicine and Pharmacy, Timișoara, Romania

- 2“Louis Turcanu” Clinical Emergency Hospital for Children, Timișoara, Romania

- 3IIIrd Pediatric Clinic, Pediatric Cardiology, Victor Babeș University of Medicine and Pharmacy, Timișoara, Romania

- 4Département de Génétique Médicale, AP-HP, GHUEP, Hôpital Armand Trousseau, Paris, France

- 5INSERM, UMRS 933, Hôpital Armand Trousseau, Paris, France

- 6Sorbonne Universités, UPMC Univ Paris 06, Paris, France

- 7Genetics Department Cluj-Napoca, Iuliu Hațieganu University of Medicine and Pharmacy, Cluj-Napoca, Romania

- 8Discipline of Pediatric Surgery, Victor Babeș University of Medicine and Pharmacy, Timișoara, Romania

- 9IIIrd Pediatric Clinic, Victor Babeș University of Medicine and Pharmacy, Timișoara, Romania

3q29 deletion syndrome is a rare disorder, causing a complex phenotype. Clinical features are variable and relatively non-specific. Our report aims to present an atypical, de novo deletion in chromosome band 3q29 in a preschool boy, first child of healthy non-consanguineous parents, presenting a particular phenotype (microcephaly, “full moon” face, flattened facial profile, large ears, auricular polyp, and dental dystrophies), motor and cognitive delay, characteristics of autism spectrum disorder and aggressive behavior. He also presented intrauterine growth restriction (birth weight 2,400 g) and a ventricular septal defect. SNP Array revealed a 962 kb copy number loss, on the chromosome 3q29 band (195519857–196482211), consistent with 3q29 microdeletion syndrome. FISH analysis using a RP11-252K11 probe confirmed the deletion in the proband, which was not present in the parents. Although the patient's deletion is relatively small, it partly overlaps the canonical 3q29 deletion (defined between TFRC and DLG1 gene) and extends upstream, associating a different facial phenotype compared to the classic 3q29 deletion, nonetheless showing a similar psychiatric disorder. This deletion is different from the canonical region, as it does not include the PAK2 and DLG1 genes, considered as candidates for causing intellectual disability. Thus, narrowing the genotype-phenotype correlation for the 3q29 band, FBX045 is suggested as a candidate gene for the neuropsychiatric phenotype.

Established Facts and Novel Insights

Established Facts

- 3q29 deletion syndrome is characterized by a variable clinical presentation, with mild to moderate intellectual disability, autism, gait ataxia, microcephaly, cleft lip and palate, chest wall deformity.

- Affected people also show psychiatric disturbances, including aggression, anxiety, hyperactivity, and bipolar disorder with psychosis.

- Cardiac malformations, were reported in 11/42 of people with 3q29 del.

Novel Insights

- We report a de novo small deletion (<1Mb) on 3q29 in a patient with microcephaly, moon face, flat profile, global developmental delay, aggressive behavior, and ventricular septal defect.

- This cardiac malformation was reported previously in only two cases.

- This deletion is different from the canonical region, as it does not include the PAK2 and DLG1 genes, considered as candidates causing intellectual disability; thus, narrowing the genotype-phenotype correlation for the 3q29 band.

- FBX045 is suggested as a candidate gene for the neuropsychiatric phenotype.

Introduction

Rare diseases are complex pathologies that require a multidisciplinary team and a very rigorous clinical evaluation. Some have a distinct, nonetheless, non-specific phenotype that makes the clinical diagnosis difficult. 3q29 deletion syndrome is a rare condition, reported in 2001 (1) and characterized by a variable clinical presentation, with mild to moderate intellectual disability, autism, gait ataxia, a chest wall deformity and additional features, including microcephaly, cleft lip and palate, horseshoe kidney and hypospadias observed in very few patients. Congenital anomalies associated with this condition are cardio-vascular defects, gastrointestinal abnormalities, failure to thrive, and teeth abnormalities (1, 2).

The canonical deleted region (1.6 Mb) includes several genes (~22 genes) with important roles in brain and neurocognitive development (3). From those, PAK2 and DLG1 genes were considered as candidates for causing intellectual disability. The chromosome 3q29 band was identified as a risk factor for schizophrenia, autism, bipolar disorders (4), and other neuropsychiatric pathologies; however, the phenotype is not clearly defined (4–6).

3q29 deletion syndrome has an autosomal dominant transmission. The deletion is frequently associated with segregation of neuropsychiatric diseases in families (5, 6). The deletion presents with a variable phenotype; however, the neurocognitive abnormalities are presented in most patients (2).

We aim to present a case of atypical 3q29 deletion syndrome with a particular phenotype and intellectual disability in order to further refine the genotype phenotype relation.

Clinical Presentation and Family History

The patient was born at 40 weeks of gestation, with a weight of 2,400 g, the first born from healthy non-consanguineous parents. The parents had normal intelligence and no reported behavioral issues. The patient's family history was unremarkable.

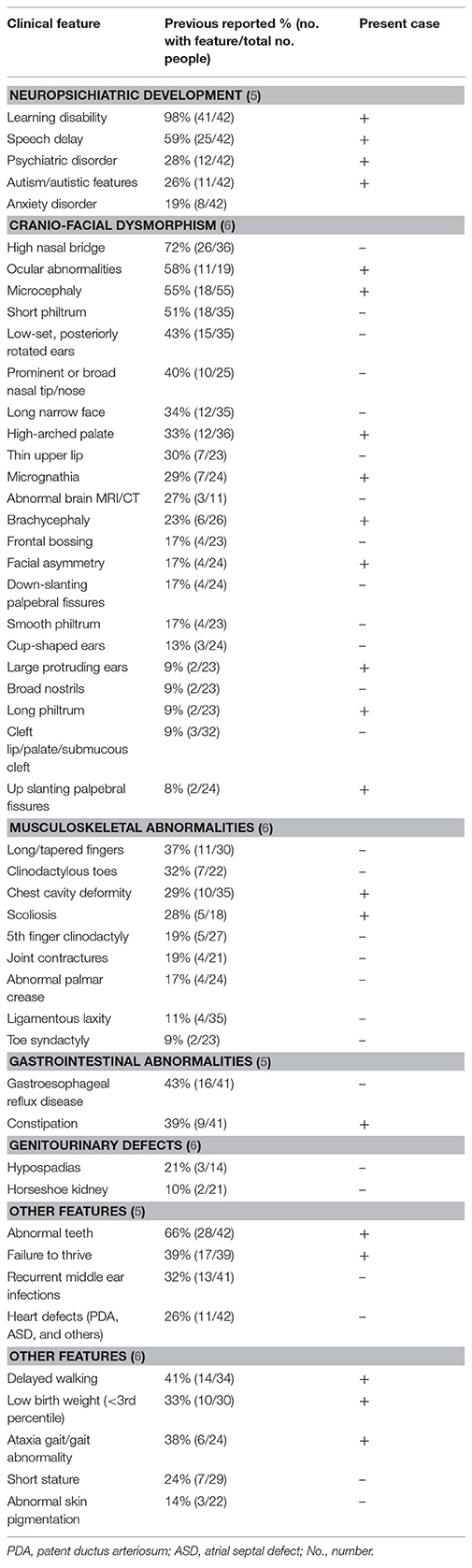

At 7 years of age, the patient had a particular phenotype (Figure 1) with a “full moon” face, strabismus, antimongoloid slants, flattened facial profile, deviated septum, long philtrum, microretrognathia, dental dystrophies, high palate, large ears, auricular polyp, and a nasally voice. His body mass index was 19.3 kg/m2 (+2 standard deviations-SD) showing obesity. His height was 122.5 cm (+1 SD), within the normal range for boys at this age. At the age of 7 years he presented waddling gait and was not able to run. The clinical presentation of the patient in comparison to others reported in a 3q29 deletion registry (5), is presented in Table 1. The registry has the largest reported cohort in literature with 3q29 deletion.

Table 1. Clinical presentation of patient in comparison to phenotypic features, reported in a registry for 3q29 deletion (5) or by the literature review from Cox and Butler (6), arranged by decreasing frequency.

The patient presented intellectual disability. At the age of 7 years, the patient's psychological development was comparable to that of a 2, 5 years old child. Additionally, he presented aggressive, sometimes uninhibited behavior and poor eye contact. Communication abilities included only hand gestures, and no words. He could interact with a mobile phone. The patient presented various anxieties (including a fear of dogs and stairs). He attended a normal kindergarten for 6 months, however, could not cope and thus, later attended services offered by a specialized center for intellectual disabilities.

His personal history showed delayed motor milestones. He started to walk around the age of 3 years and acquisitioned sphincter control after the age of 4 years. The history of illness included failure to thrive in the first 2 years, chronic constipation and repeated upper respiratory infections. He received treatment with Risperidone for his behavior, which showed a moderate response. Cardiologic evaluation at the age of 5 years, diagnosed the spontaneously closed ventricular septal defect.

The patient's imagistic brain evaluation, using MRI at 7 years of age was normal. Repeated EEG evaluations did not show significant changes.

Methodology

Clinical Evaluation

The patient was evaluated by clinical geneticists along with a multidisciplinary team. The mother completed a parent-report questionnaire (The Children Behavior Check List-CBCL) in order to evaluate her perception about the child's neuropsychiatric development.

The parents provided written informed consent to publish this case (including publication of images).

Molecular Analyses

The genetic laboratory tests performed inlcuded: cytogenetic analysis (classic karyotype), SNP array using Infinium® OmniExpress-24 v1.2 Kit, ~710,000 Markers (scan performed using Iscan Illumina and GenomeStudio v2.0 software) and FISH analysis for patient and parents using the RP11-252K11 probe (localized to chr3:195907410-196071593 on build hg19, includes the ZDHHC19, PCYT1A, SLC51A, TCTEX1D2, and TM4SF19 genes).

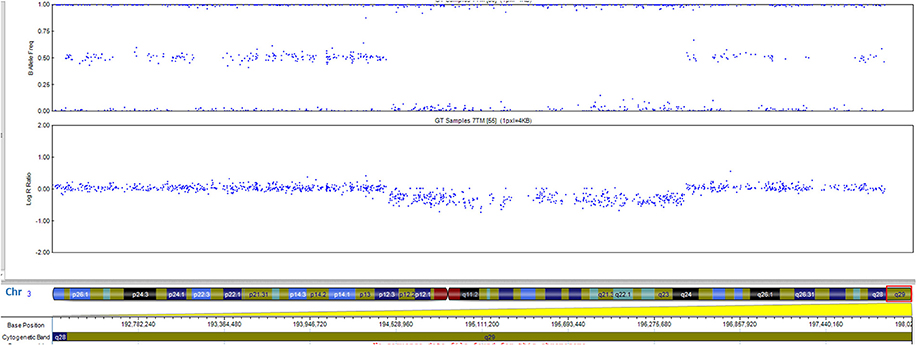

The patient has a normal male karyotype (46, XY). SNP array identified a 962 kb copy number loss of chromosome 3q29, between 195519857 and 196482211 (Figure 2). That region includes the following morbid genes TFRC, PCYT1A, RNF168, TCTEX1D2, and CEP19. Non-morbid genes included in the deleted region are: TNK2, ZDHHC19, SLC51A, TM4SF19, UBXN7, RNF168, SMCO1, WDR53, FBXO45, PIGX, and NRROS. The identified copy number variation was associated with 3q29 Microdeletion syndrome (OMIM 609425). No other significant genomic imbalances were detected. The 3q29 deletion was confirmed in the patient by FISH analysis using a RP11-252K11 probe. The parental genetic evaluation using the same FISH probe, was negative, thus, showing a de novo origin of the deletion. The FISH analysis in the parents cannot exclude small deletion/duplication/insertion in the targeting region. Gonadal mosaicism cannot be excluded and was considered in genetic counseling.

Figure 2. The 0.96-Mb deletion in the 3q29 band, arr[GRCh37] 3q29(195519857_196482211)x1 detected by whole genome SNP-array analysis and ideogram of chromosome 3. Morbid genes are depicted in red for the 3q29 band.

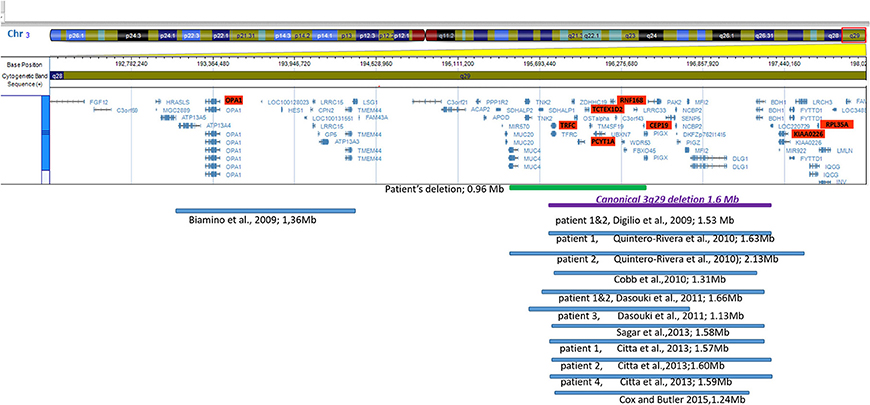

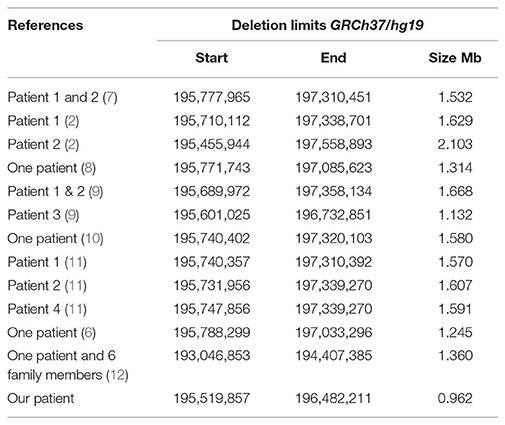

A systematic literature search for similar reports was performed to have an overview of genotype and phenotype syndrome aspects. The findings are presented in Figure 3 (ideogram) and Table 2 (deleted limits).

Figure 3. Ideogram of chromosome 3 with zoomed-in details of the 3q29 band shown with a schematic view of the genes involved in the deletion. Horizontal lines in blue show proportional representation of deletion size in our patient and previously reported deletions in other patients (in order of publication year). Deletion limits were converted to GRCh37/hg19 reference (also shown in Table 2). The ideogram included the deletions reported in the literature which were detected by array. Cases reported using the FISH method were not included.

Table 2. Deletion limits reported in literature using array platforms illustrated in Figure 3.

Discussion

Described initially as a 1.6 Mb deletion on THE long arm of chromosome 3 (1, 3), the 3q29 deletion syndrome was defined as a recurrent subtelomeric deletion (hg 19 coordinates 195,788,299–197,033,296) between TFRC and DLG1 genes (6). Authors described families with 3q29 syndrome in several generations (11, 13). However, the present case is de novo, his parents do not present similar clinical or molecular abnormalities. The family history is not relevant for neuropsychiatric disorders.

The syndrome phenotype varies, from mild to severe, without very specific facial characteristics. Intellectual disability and psychiatric disorders are the most consistent findings (2). Glassford MR and collaborators have developed an online registry to summarize the phenotypic features of 3q29 deletion syndrome (5). To date, this is the largest cohort of patients with reported clinical data from 44 individuals. However, the data was self-reported/reported by family members and does not show deletion sizes to enable genotype-phenotype correlation. Authors highlighted the large clinical variability. Nonetheless, 64% of patients had a low birth weight and feeding problems, while ~30% of cases had neuropsychiatric disorders (anxiety, panic attacks, depression or bipolar disorder, and schizophrenia). The present case showed various anxieties already present at an early age. The patients in the registry also associated organ abnormalities. Cardiac defects were reported in 26% of cases, with the most frequently defect reported as ductus arteriosus and ventricular septal defect, a rare condition, reported only in two other cases (11, 14). The registry reported a high prevalence of gastrointestinal disorders (68%). In the present case constipation was one of the major issues for the family. The present case had rare clinical features (Table 1), reported in <20% of cases, such as large protruding ears (9%) and long philtrum (9%). Conversely, features frequently reported (in more than 40% of cases) were not identified, such as a high nasal bridge or long narrow face, however, these features could change with age.

The deleted region of the presented patient partly overlaps the canonical 3q29 deletion, associating a different facial phenotype compared to the classic 3q29 deletion, nonetheless showing a similar psychiatric disorder (Figure 1). PAK2 and DLG1 are autosomal homologs of the X-linked intellectual disability genes PAK3 and DLG3. Haplosufficiency of PAK3 or DLG3 was previously associated with intellectual disability (14). Importantly, several transcription factors are mapped within this region, however their role in development is not completely understood. The patient reported by Krepischi-Santos et al. (15) had moderate intellectual disability and a particular phenotype caused by a small deletion of 1.0 Mb on the 3q29 chromosome, including gene DIG1 (OMIM 601014) (5). Cobb's case, described in 2010 (8) was a 6 years old boy with a particular phenotype, autism spectrum disorders and ADHD but no intellectual disability, although the deleted region included morbid genes previously associated with intellectual disability (DLG1 and PAK2) (8).

Out of the 11 non-morbid genes included in the deleted region of the patient, four (TNK2, UBXN7, SLC51A, and FBX045) have expressions in the brain. TNK2 was reported (16), in a small family with autosomal recessive (AR), infantile onset epilepsy and intellectual disability. Functional studies were performed for the homozygous variant identified. Although our patient did not show seizures, this gene could potentially be considered relevant for the phenotype. The SLC51A gene was found to have a potential role of the organic solute transporter in brain dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate/pregnenolone sulfate homeostasis. This transporter was localized especially in steroidogenic cells of the cerebellum and hippocampus. The impact of transporters on neurosteroid homeostasis is poorly understood (17). The UBXN7 gene was shown to be expressed in the brain, however its role is poorly understood at the moment (18). FBX045 was suggested as a candidate gene for the neuropsychiatric phenotype by [Quintero-Rivera et al. (2)]. The FBXO45 gene was also considered as a prominent candidate for mediating schizophrenia pathogenesis (19, 20), as the ubiquitin ligase F-box protein 45 is critical for synaptogenesis, neuronal migration, and synaptic transmission. While a genome-wide association study of coping behaviors suggests that FBXO45 is associated with emotional expression (21). Compared with other patient's deletion size and region involved in Figure 3, the closest is patient 3, described by [Dasouki et al. (9)], however patient phenotypic data was not available to the authors, except for the developmental delay and heart murmur, similar to our patient.

The function of the non-morbid ZDHHC19, SMCO1, WDR53, and PIGX genes is unclear or not relevant for the phenotype. Interestingly, the NRROS, TM4SF19 (non-morbid), RNF168, and TFRC (morbid, AR) genes were found to be related to the immune system, yet there were no apparent immune disfunctions in our patient or in the literature.

An Italian group (12) reported a 1.36 Mb deletion of the 3q arm, 193,046,853–194,407,385, outside of the known specific region for the classical 3q29 deletion syndrome, inherited from the mother and reported in several siblings, presenting with gastroesophageal reflux and milk protein intolerance as first clinical symptoms, later developing mild intellectual disability and endocrinological abnormalities. An overarching characteristic, described by Biamino was overweight, which was also observed in our patient. However, they do not share similar deleted regions. Bioamino et al. (12) suggested that the HES1 gene could be causative for the obesity phenotype, while in our patient the CEP19 gene (associated with Morbid obesity and spermatogenic failure-AR) in haploinsufficiency could play a potential role in our patient.

Aside from CEP19, other AR genes in the deleted region of the patient were: TFRC, associated with immunodeficiency 46 (OMIM 616740), PCYT1A, associated with Spondylometaphyseal dysplasia with cone-rod dystrophy (OMIM 608940), TCTEX1D2, associated with Short-rib thoracic dysplasia 17 with or without polydactyly (OMIM 617405), and RNF168, associated with RIDDLE syndrome (OMIM 611943). Considering the lack of association between patient phenotype and the symptoms of the associated pathology, these genes were not considered relevant for the phenotype.

The reported case provides additional clinical and molecular features that complete the phenotype and genotype of 3q29 Deletion syndrome.

A second hypothesis was considered for this particular case, however, the other CNVs observed in the SNP array analysis were benign. Also, the parental study showed de novo deletion 3q29. These arguments are supportive for the phenotype-genotype correlation. Nonetheless, the possibility of a second event, at the molecular level, cannot be excluded.

Conclusion

We present the phenotype correlated with the smallest reported de novo chromosome 3q29 deletion (<1 Mb) in a patient with microcephaly, full moon face, flat profile, global developmental delay, aggressive behavior, and ventricular septal defect. This deletion is different from the canonical 3q29 deleted region, as it does not include the PAK2 and DLG1 genes, considered as candidates for causing intellectual disability, thus, narrowing the genotype-phenotype correlation for the region. FBX045 is suggested as a candidate gene for the neuropsychiatric phenotype.

Data Availability

This manuscript contains previously unpublished data. The name of the repository and accession number are not available.

Ethics Statement

The parents provided the written informed consent to publish this case (including publication of images).

Author Contributions

AC, AD, CP, MP, and SA contributed to patient clinical and genetic evaluation and the writing process. GD contributed to patient cardiological evaluation and the writing process. CH and DM contributed to patient genetic evaluation and the writing process.

Funding

The research was performed in the Center of Genomic Medicine from the Victor Babes University of Medicine and Pharmacy of Timisoara, POSCCE Project ID: 1854, cod SMIS: 48749, contract 677/09.04.2015. The funding agency for the above-mentioned project, ANCS had no role in study design, data collection, and analysis, decision to publish or preparation of the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We thank the family for their collaboration and trust.

References

1. Rossi E, Piccini F, Zollino M, Neri G, Caselli D, Tenconi R, et al. Cryptic telomeric rearrangements in subjects with mental retardation associated with dysmorphism and congenital malformations. J Med Genet. (2001) 38:417–20. doi: 10.1136/jmg.38.6.417

2. Quintero-Rivera F, Sharifi-Hannauer P, Martinez-Agosto JA. Autistic and psychiatric findings associated with the 3q29 microdeletion syndrome: case report and review. Am J Med Genet A. (2010) 152A:2459–67. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.33573

3. Willatt L, Cox J, Barber J, Cabanas ED, Collins A, Donnai D, et al. 3q29 microdeletion syndrome: clinical and molecular characterization of a new syndrome. Am J Hum Genet. (2005) 77:154–60. doi: 10.1086/431653

4. Green EK, Rees E, Walters JTR, Smith K-G, Forty L, Grozeva D, et al. Copy number variation in bipolar disorder. Mol Psychiatry. (2016) 21:89–93. doi: 10.1038/mp.2014.174

5. Glassford MR, Rosenfeld JA, Freedman AA, Zwick ME, Mulle JG. Novel features of 3q29 deletion syndrome: results from the 3q29 registry. Am J Med Genet A. (2016) 170:999–1006. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.37537

6. Cox DM, Butler MG. A clinical case report and literature review of the 3q29 microdeletion syndrome. Clin Dysmorphol. (2015) 24:89–94. doi: 10.1097/MCD.0000000000000077

7. Digilio MC, Bernardini L, Mingarelli R, Capolino R, Capalbo A, Giuffrida MG, et al. 3q29 Microdeletion: a mental retardation disorder unassociated with a recognizable phenotype in two mother–daughter pairs. Am J Med Genet A. (2009) 149A:1777–81. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.32965

8. Cobb W, Anderson A, Turner C, Hoffman RD, Schonberg S, Levin SW. 1.3 Mb de novo deletion in chromosome band 3q29 associated with normal intelligence in a child. Eur J Med Genet. (2010) 53:415–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmg.2010.08.009

9. Dasouki M.J., Lushington G. H., Hovanes K., Casey J., Gorre M. (2011). The 3q29microdeletion syndrome: report of three new unrelated patients and insilico‘RNA binding’analysis of the 3q29 region. Am. J. Med. Genet. A155A:1654–1660. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.34080

10. Sagar A, Bishop JR, Tessman DC, Guter S, Martin CL, Cook EH. Co-occurrence of autism, childhood psychosis, and intellectual disability associated with a de novo 3q29 microdeletion. Am J Med Genet A. (2013) 161A:845–9. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.35754

11. Città S, Buono S, Greco D, Barone C, Alfei E, Bulgheroni S, et al. 3q29 microdeletion syndrome: Cognitive and behavioral phenotype in four patients. Am J Med Genet A. (2013) 161A:3018–22. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.36142

12. Biamino E, Di Gregorio E, Belligni EF, Keller R, Riberi E, Gandione M, et al. A novel 3q29 deletion associated with autism, intellectual disability, psychiatric disorders, and obesity. Am J Med Genet Part B Neuropsychiatr Genet. (2016) 171B:290–9. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.32406

13. Clayton-Smith J, Giblin C, Smith RA, Dunn C, Willatt L. Familial 3q29 microdeletion syndrome providing further evidence of involvement of the 3q29 region in bipolar disorder. Clin Dysmorphol. (2010) 19:128–32. doi: 10.1097/MCD.0b013e32833a1e3c

14. Li F, Lisi EC, Wohler ES, Hamosh A, Batista DA. 3q29 interstitial microdeletion syndrome: an inherited case associated with cardiac defect and normal cognition. Eur J Med Genet. (2009) 52:349–52. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmg.2009.05.001

15. Krepischi-Santos AC, Vianna-Morgante AM, Jehee FS, Passos-Bueno MR, Knijnenburg J, Szuhai K, et al. Whole-genome array-CGH screening in undiagnosed syndromic patients: old syndromes revisited and new alterations. Cytogenet Genome Res. (2006) 115:254–61. doi: 10.1159/000095922

16. Hitomi Y, Heinzen EL, Donatello S, Dahl H, Damiano JA, McMahon JM, et al. Mutations in TNK2 in severe autosomal recessive infantile onset epilepsy. Ann Neurol. (2013) 74:496–501. doi: 10.1002/ana.23934

17. Grube M, Hagen P, Jedlitschky G. Neurosteroid transport in the brain: role of ABC and SLC transporters. Front Pharmacol. (2018) 9:354. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2018.00354

18. Nagase T, Ishikawa K, Suyama M, Kikuno R, Miyajima N, Tanaka A, et al. Prediction of the coding sequences of unidentified human genes. XI. The complete sequences of 100 new cDNA clones from brain which code for large proteins in vitro. DNA Res. (1998)5:277–86.

19. Viñas-Jornet M, Esteba-Castillo S, Baena N, Ribas-Vidal N, Ruiz A. High incidence of copy number variants in adults with intellectual disability and co-morbid psychiatric disorders. Behav Genet. (2018) 48:323–36. doi: 10.1007/s10519-018-9902-6

20. Wang C, Koide T, Kimura H, Kunimoto S, Yoshimi A. Novel rare variants in F-box protein 45 (FBXO45) in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. (2014) 157:149–56. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2014.04.032

Keywords: 3q29, cytogenetics, intellectual disability, cardiac malformation, behavior

Citation: Chirita Emandi A, Dobrescu AI, Doros G, Hyon C, Miclea D, Popoiu C, Puiu M and Arghirescu S (2019) A Novel 3q29 Deletion in Association With Developmental Delay and Heart Malformation—Case Report With Literature Review. Front. Pediatr. 7:270. doi: 10.3389/fped.2019.00270

Received: 15 February 2019; Accepted: 14 June 2019;

Published: 08 July 2019.

Edited by:

Merlin G. Butler, University of Kansas Medical Center, United StatesReviewed by:

Fan Jin, Zhejiang University, ChinaFeodora Stipoljev, University Hospital Sveti Duh, Croatia

Copyright © 2019 Chirita Emandi, Dobrescu, Doros, Hyon, Miclea, Popoiu, Puiu and Arghirescu. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Adela Chirita Emandi, YWRlbGEuY2hpcml0YSYjeDAwMDQwO3VtZnQucm8=

Adela Chirita Emandi

Adela Chirita Emandi Andreea Iulia Dobrescu1,2

Andreea Iulia Dobrescu1,2 Maria Puiu

Maria Puiu