95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Oncol. , 23 July 2018

Sec. Cancer Imaging and Image-directed Interventions

Volume 8 - 2018 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fonc.2018.00271

Lauren C. J. Baker1

Lauren C. J. Baker1 Arti Sikka1†

Arti Sikka1† Jonathan M. Price1†

Jonathan M. Price1† Jessica K. R. Boult1

Jessica K. R. Boult1 Elise Y. Lepicard1

Elise Y. Lepicard1 Gary Box2

Gary Box2 Yann Jamin1

Yann Jamin1 Terry J. Spinks1

Terry J. Spinks1 Gabriela Kramer-Marek1

Gabriela Kramer-Marek1 Martin O. Leach1

Martin O. Leach1 Suzanne A. Eccles2

Suzanne A. Eccles2 Carol Box1,2‡

Carol Box1,2‡ Simon P. Robinson1*‡

Simon P. Robinson1*‡Background: Overexpression of EGFR is a negative prognostic factor in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC). Patients with HNSCC who respond to EGFR-targeted tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) eventually develop acquired resistance. Strategies to identify HNSCC patients likely to benefit from EGFR-targeted therapies, together with biomarkers of treatment response, would have clinical value.

Methods: Functional MRI and 18F-FDG PET were used to visualize and quantify imaging biomarkers associated with drug response within size-matched EGFR TKI-resistant CAL 27 (CALR) and sensitive (CALS) HNSCC xenografts in vivo, and pathological correlates sought.

Results: Intrinsic susceptibility, oxygen-enhanced and dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI revealed significantly slower baseline R2∗, lower hyperoxia-induced ΔR2∗ and volume transfer constant Ktrans in the CALR tumors which were associated with significantly lower Hoechst 33342 uptake and greater pimonidazole-adduct formation. There was no difference in oxygen-induced ΔR1 or water diffusivity between the CALR and CALS xenografts. PET revealed significantly higher relative uptake of 18F-FDG in the CALR cohort, which was associated with significantly greater Glut-1 expression.

Conclusions: CALR xenografts established from HNSCC cells resistant to EGFR TKIs are more hypoxic, poorly perfused and glycolytic than sensitive CALS tumors. MRI combined with PET can be used to non-invasively assess HNSCC response/resistance to EGFR inhibition.

Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) is a significant cause of morbidity and mortality, with almost 700,000 new cases estimated annually, worldwide (1). For locally advanced head and neck cancer (LAHNC), the standard of care is chemoradiotherapy (with/without initial surgery) (2). Even with aggressive multimodality management, the majority of patients with LAHNC develop incurable locoregional or systemic relapse (3). For patients with recurrent and/or metastatic (R/M) disease, prognosis is poor and survival rates are dismal, highlighting a requirement for novel therapeutic options together with clinically useful predictive biomarkers (4).

The epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) belongs to the ErbB/HER family of transmembrane receptor tyrosine kinases and has a key role in HNSCC (5). Ligand binding to EGFR activates many downstream signaling pathways, promoting cell proliferation, survival, DNA repair, migration, invasion and angiogenesis (6). Elevated expression of EGFR occurs in >80% HNSCC, and is associated with poor prognosis and treatment resistance (7, 8). EGFR is thus a compelling therapeutic target, and a number of EGFR family antagonists have been developed (5, 6). The monoclonal antibody cetuximab has an established role in combination with radiotherapy in newly-diagnosed LAHNC (9), and with cisplatin/5-FU in R/M disease (10). Clinical responses to first generation EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs), such as gefitinib or erlotinib, in HNSCC were disappointing (11). However afatinib, an irreversible HER family inhibitor, recently demonstrated improved progression-free survival in patients with R/M HNSCC (12). Nevertheless, the overwhelming majority of patients who initially respond to targeted therapies only achieve stable disease of short duration and acquired resistance usually manifests within 6–12 months (13–15).

A clinical definition of acquired resistance to EGFR TKIs has been proposed for patients with non-small cell lung cancer (16). These guidelines are based on detecting known drug-sensitizing EGFR mutations, combined with anatomical imaging, to detect disease progression whilst on therapy. However, in HNSCC, this approach is not applicable, since EGFR mutations are rare (17). Furthermore, levels of EGFR protein do not correlate with clinical response to EGFR TKIs in HNSCC (13, 18). Alternative strategies to identify HNSCC patients who are likely to benefit from EGFR-targeted therapies, together with biomarkers of response for monitoring therapy, are urgently required (19, 20).

An additional challenge in the treatment of the often bulky HNSCC tumors is hypoxia. The low levels of oxygen that result from an anarchic tumor vasculature and uncontrolled cell division are a well-established cause of treatment resistance and adversely affect HNSCC prognosis (21, 22). Under hypoxic conditions, altered gene transcription and adaptive signaling networks enable cancer cells to resist apoptosis and continue to proliferate in adversity, leading to the development of an increasingly aggressive tumor (23, 24). Expression and activation of EGFR are moderated by hypoxia although the mechanisms involved are yet to be fully elucidated (25). Co-localization of hypoxic regions and EGFR expression has been demonstrated in HNSCC biopsies and was associated with poor outcome (26). Conversely, hypoxic areas of HNSCC tumors were found to have reduced EGFR expression (27), possibly due to degradation of EGFR by the hypoxia-induced protein PHD-3 (28), and this was proposed as a putative mechanism of resistance to anti-EGFR therapies.

For the assessment of molecularly targeted agents such as TKIs, the standard response evaluation criteria in solid tumors (RECIST) may be suboptimal (29). This is particularly pertinent in the context of drug resistance, where genomic and morphological transformations typically precede changes in tumor volume. Advances in imaging technologies provide a means of defining non-invasive quantitative biomarkers to inform on biologically relevant structure-function relationships in tumors, enabling their accurate detection, an understanding of their behavior, and informing on response to targeted and, by extension, conventional treatments, at relatively early time points (30). Predictive imaging biomarkers of sensitivity and resistance to targeted anti-cancer treatments would thus provide opportunities to deliver personalized and more effective therapy regimes (31, 32).

To investigate EGFR TKI resistance in HNSCC, we have generated a CAL 27 cell line, CALR, that is resistant to multiple EGFR TKIs (gefitinib, erlotinib, lapatinib and afatinib) (33). An isogenic control cell line, CALS, retained sensitivity to EGFR TKIs in vitro and in vivo (33). The aim of this study was to exploit CALR/S xenografts to identify clinically translatable functional imaging biomarkers that (i) correctly report on the pathology and processes relevant to acquired resistance to EGFR inhibition in HNSCC in vivo and (ii) may have value in assessing response to targeted EGFR inhibition and, potentially, conventional radiotherapy/chemotherapy. To this end, a range of advanced magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and positron emission tomography (PET) techniques, and the quantitative imaging biomarkers they afford, were evaluated and pathologically qualified to assess tumor hypoxia, angiogenesis and metabolism in vivo.

EGFR TKI-resistant CALR and -sensitive CALS HNSCC cells were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (Invitrogen, Paisley, UK) and maintained at 37°C in a humidified incubator with an atmosphere of 95% air, 5% CO2 (33). Cells were routinely screened for mycoplasma using PCR and had STR profiles (obtained using a GenePrint® 10 kit, Promega, Southampton, UK and a 3730xl DNA analyser, Applied Biosystems, Warrington, UK) identical to parental CAL 27 cells. STR profiles were obtained contemporaneous to the in vivo experiments (October 2013) and re-checked after completion (August 2015).

All animal experiments were performed in accordance with the local ethical review panel, the UK Home Office Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act 1986, the United Kingdom National Cancer Research Institute guidelines for the welfare of animals in cancer research (34), and the ARRIVE (Animal Research: Reporting of In Vivo Experiments) guidelines (35). Female NCr-Foxn1nu mice (7–8 weeks old, Charles River) were injected with either 5 × 105 CALR or 5 × 106 CALS cells subcutaneously in the right flank. Ten-fold fewer CALR cells were used to compensate for the more rapid tumor growth rate of the resulting xenografts in vivo (33). Animals were housed in specific pathogen-free rooms in autoclaved, aseptic microisolator cages with a maximum of four animals per cage. Food and water were provided ad libitum. The mice were routinely monitored for the appearance of palpable tumors and imaged at a tumor diameter of ~0.8 to 1 cm.

MRI was performed on a 7 T horizontal bore microimaging system (Bruker, Ettlingen, Germany) using a 3 cm birdcage volume coil. Anaesthesia was induced with an intraperitoneal injection of fentanyl citrate (0.315 mg ml−1) plus fluanisone [10 mg ml−1 (Hypnorm; Janssen Pharmaceutical Ltd., High Wycombe, UK)], midazolam (5 mg ml−1 [Hypnovel; Roche, Welwyn Garden City, UK)], and sterile water (1:1:2). A lateral tail vein was cannulated with a 27G butterfly catheter (Hospira, Royal Leamington Spa, UK) for remote administration of contrast media. Mice were positioned in the coil on a custom-built platform to isolate the tumor, and with a nosepiece for gas delivery, and their core temperature maintained at 37°C with warm air blown through the magnet bore.

Multiple contiguous 1 mm thick axial T2-weighted images were acquired for localization and subsequent quantitation of the tumor volume. Magnetic field homogeneity was optimized by shimming over the entire tumor volume using an automated shimming routine (FASTmap).

For intrinsic susceptibility and oxygen-enhanced MRI, multiple gradient recalled echo (MGRE) images [repetition time (TR) = 200 ms, 8 echo times (TE) ranging from 6 to 28 ms, 4 ms echo spacing, 8 averages, acquisition time (AQ) 2 min 30 s], and inversion recovery (IR) TrueFISP images (TE = 1.2 ms, TR = 2.4 ms, 25 inversion times spaced 155 ms apart, initial inversion time of 109 ms, total scan TR = 10 s, α = 60°, 8 averages, AQ of 8 min) were acquired from three contiguous 1 mm slices across the center of the tumor over a 3 × 3 cm field of view (FOV) and 128 × 128 matrix whilst the host breathed air, to enable quantitation of the transverse relaxation rate (s−1), and the longitudinal relaxation rate R1 (s−1), respectively. The gas supply was then switched to 100% oxygen administered at 1 l min−1 and, following a 5 min transition time, identical MGRE and IR-TrueFISP image sets were acquired (36).

Dynamic contrast enhanced (DCE-) MRI data were acquired from a single 1 mm thick, central axial slice across the tumor using an inversion recovery (IR) true-FISP sequence with one baseline scan (3 × 3 cm field of view, 128x96 matrix, TI = 25–1451 ms, 50 inversion times, TR = 2.4 ms, TE = 1.2 ms, 8 averages), and 60 dynamic scans (TI = 109–924 ms, 8 inversion times, TR = 2.4 ms, TE = 1.2 ms, scan TR = 10 s, 1 average, 60° flip angle, temporal resolution = 20 s) acquired for 3 min before and 17 min after an i.v. injection of 0.1 mmol kg−1 of a clinically approved, low molecular weight contrast agent gadolinium-DTPA (Gd-DTPA, Magnevist, Schering, Berlin, Germany) (37). A single slice acquisition was used for the IR-true-FISP sequence in order to minimize the temporal resolution of the dynamic acquisition and thereby optimize the accuracy of pharmacokinetic parameter estimates (38). The imaging slice used herein was taken through the largest axial extent of the tumor and assumed to be representative of the tumor as a whole.

Diffusion weighted (DW) images were acquired from the same three 1 mm thick axial slices as for intrinsic susceptibility and oxygen-enhanced MRI using an echo-planar imaging (EPI) sequence (3 × 3 cm FOV, 128 × 128 matrix, TR = 3,000 ms, 5 b values ranging from 40 to 700 s−1mm2, 4 averages).

Tumor volumes were determined using segmentation from regions of interest (ROIs) drawn on T2-weighted images for each tumor-containing slice. Functional MRI data were fitted on a pixel-by-pixel basis using in-house software (Imageview, developed in IDL, ITT Visual Information Systems, Boulder, CO, USA). MGRE, IR-TrueFISP and DW images were fitted using a Bayesian maximum a posteriori approach, allowing estimates of the oxygen-induced change in () and R1 (ΔR1), and the median ADC to be calculated, respectively (39, 40). For the IR-TrueFISP data, voxels with calculated T1 values < 200 or >3,000 ms were excluded from the analysis. For DCE-MRI analysis, IR true-FISP data were fitted using a similar approach, utilizing the dual-relaxation sensitivity (T1 and T2) of the pulse sequence and incorporating the Tofts and Kermode pharmacokinetic model, providing estimates of Ktrans (37). In addition, model-free analysis was used to derive the initial area under the gadolinium uptake curve (IAUGC60, mM Gd min−1) from 0 to 60 s after injection of Gd-DTPA, and the ratio of enhancing to total tumor volume (enhancing fraction; EF, %).

Following overnight fasting, mice bearing CALR or CALS tumors were continuously warmed using a heating pad prior to and during the tracer uptake period. Both fasting and warming reduce normal/brown fat tissue radiotracer uptake, thereby enhancing tumor contrast (41). Mice were intravenously administered with 6.2–6.5 MBq of 18F-FDG (Alliance Medical Radiopharmacy Ltd, Sutton, UK) 30 min after initiation of warming, and PET-CT imaged 1 h later under isoflurane anesthesia using a trimodal PET/SPECT/CT scanner (Carestream Health, Rochester, NY, USA) for a duration of 600 s. A calibration phantom containing ~0.5–1.5 MBq 18F-FDG was positioned in the middle of the FOV and imaged simultaneously to ensure accurate quantification of tumor tracer uptake. The total activity in the FOV was < 10 MBq, where acceptable linearity of the PET scanner has previously been established (42). Each PET scan was followed by a CT examination (45 kVp, 0.4 mA, 250 projections) for attenuation correction and anatomical localisation.

PET images were reconstructed with a maximum likelihood expectation maximization algorithm using 12 iterations and a voxel size of 0.5 mm3. Scatter, randoms and decay correction were applied within the reconstruction with attenuation correction derived from the CT data. The CT data was reconstructed with filtered back projection. The PET/CT images were co-registered and analyzed using PMOD (version 3.501, PMOD Technologies Ltd, Zurich, Switzerland). Whole tumor ROIs were delineated using an isocontour method based on 50% of the maximum tumor uptake value, and the uptake of 18F-FDG quantified by calculation of the mean percentage injected dose per gram (%ID/g) using PMOD, corrected using the calibration phantom data.

Mice bearing CALR or CALS tumors were administered the hypoxia marker pimonidazole (60 mg kg−1 i.p., Hypoxyprobe Inc., Burlington, VT, USA) and the perfusion marker Hoechst 33342 (15 mg kg−1 i.v., Sigma-Aldrich, Poole, UK), 45 min and 1 min, respectively, prior to necropsy. Tumors were rapidly excised and bisected in the imaging plane at the position of the central MRI slice, with half the tumor snap-frozen over liquid nitrogen and the other half formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded (FFPE).

Fluorescence signals from reduced pimonidazole adducts bound with mouse monoclonal FITC-conjugated antibodies (Hypoxyprobe Inc.) and from Hoechst 33342 were detected and quantified in whole tumor frozen sections (10 μm) using a motorized scanning stage (Prior Scientific Instruments, Cambridge, UK) attached to a BX51 microscope (Olympus Optical, London, UK), driven by image analysis software (CellP, Soft Imaging System, Münster, Germany), as previously described (37). Immunohistochemical (IHC) detection of glucose transporter 1 (Glut-1) expression was performed on FFPE sections (5 μm), as previously described (43). In addition to a composite whole tumor image, high magnification (x100) images were acquired from ten randomly selected fields for each tumor, from which the percentage of Glut-1 staining was determined using color deconvolution in ImageJ (NIH, Bethesda, MD, USA). Cellular density was assessed on haematoxylin and eosin (H&E) stained FFPE sections by counting the number of nuclei in four square ROIs from a total area of 0.01 mm2 per field (x200 magnification, six fields assessed per section) (44).

Statistical analysis of the MRI, PET and histopathological data was performed with GraphPad Prism ver 6.07 (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA, USA). Cohort sizes used for each experiment are shown in each figure (N.B. each animal did not necessarily undergo all the functional MRI scans). Results are presented in the form of mean ± 1 s.e.m. Following application of a Shapiro-Wilk normality test to confirm the Gaussian distribution of the data, significance testing employed either unpaired Student's two-tailed t-test assuming equal variance or the non-parametric Mann-Whitney test as appropriate, with a 5% level of significance.

HNSCC xenografts derived from EGFR TKI-resistant CALR cells grew more rapidly than CALS tumors, as previously reported (33). There was however no significant difference in the mean tumor volumes (as determined by T2-weighted MRI) of the CALR (533 ± 45 mm3) and CALS (506 ± 79 mm3) cohorts at the time of imaging.

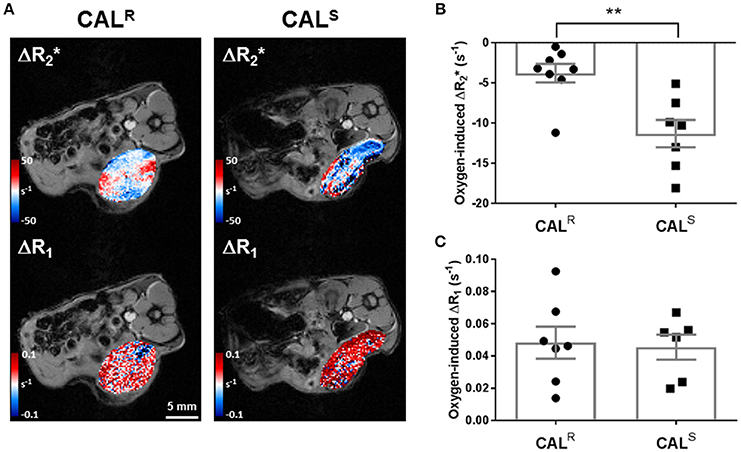

A hyperoxia-induced reduction in tumor , resulting from the flushing out of paramagnetic deoxyhaemoglobin with diamagnetic oxyhaemoglobin, and altered tumor R1 arising from more dissolved paramagnetic oxygen in blood, are being actively investigated for the provision of imaging biomarkers of hypoxia (36, 45). Parametric maps showing the spatial distribution of oxygen-induced and ΔR1 in a CALR and a CALS tumor are shown in Figure 1A. Visually, hyperoxia predominantly induced a heterogeneous reduction in in both cohorts, which was greater in the CALS tumors. Overall, a small, heterogeneous oxygen-induced increase in R1 was the predominant response in both tumor types. No spatial relationship between hyperoxia-induced and ΔR1 was apparent in either tumor type. Quantitatively, mean baseline was significantly (p < 0.01) slower in the CALR (58 ± 2 s−1) than the CALS (70 ± 2 s−1) tumors. Oxygen-inhalation resulted in an overall reduction in mean in both CALR (−4 ± 1 s−1) and CALS (−11 ± 2 s−1) tumors, the response of the CALS tumors being significantly (p < 0.01) greater than that of the CALR xenografts (Figure 1B). There was no significant difference in mean baseline R1 (0.49 ± 0.003 and 0.49 ± 0.007 s−1) and mean hyperoxia-induced ΔR1 (0.05 ± 0.01 and 0.05 ± 0.01 s−1) between the CALR and CALS tumors, respectively (Figure 1C).

Figure 1. (A) Oxygen-induced ΔR2* and ΔR1 (both s−1) parametric maps acquired from a CALR and a CALS HNSCC xenograft in vivo. (B,C) Summary of the quantitative oxygen-enhanced MRI data, showing a significantly greater hyperoxia-induced ΔR2* in the CALS relative to the CALR cohort. Data are the individual oxygen-induced ΔR2* and ΔR1 measurements for each tumor, and the cohort mean ± 1 s.e.m., **p < 0.01, Student's t-test.

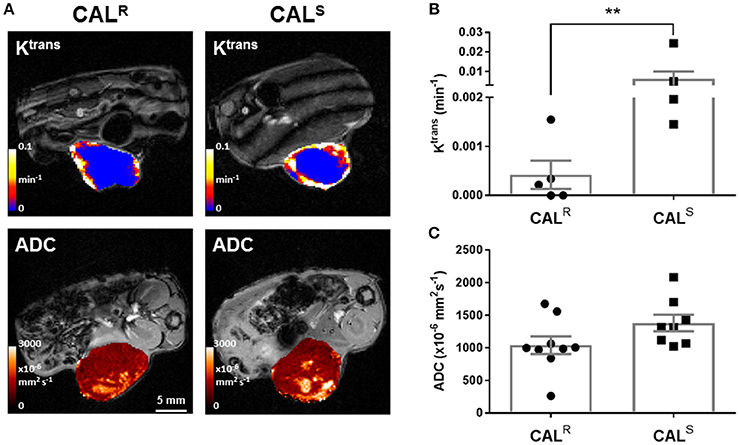

DCE-MRI measures contrast agent extravasation from the blood plasma compartment to the extravascular extracellular compartment, i.e., vascular leakage, typically expressed by the volume transfer constant Ktrans (min−1). Increasing contrast agent concentration in the extracellular leakage space is related to both tumor perfusion and permeability (46). DCE-MRI revealed that Gd-DTPA delivery was restricted to the periphery of both CALR and CALS xenografts (Figure 2A). Pharmacokinetic modeling of the DCE-MRI data revealed that Ktrans was significantly (p < 0.01) lower in the CALR tumors (Figure 2B). Model free analysis showed similarly significant lower IAUGC60 (0.0006 ± 0.0004 vs. 0.010 ± 0.005 mM Gd min−1, p < 0.01) and EF (51 ± 6 vs. 82 ± 4%, p < 0.01) in the CALR xenografts.

Figure 2. (A) Parametric maps of the transfer constant Ktrans (min−1) and the apparent diffusion coefficient, ADC (x10−6 mm2s−1), acquired from different CALR and CALS HNSCC xenografts in vivo. (B,C) Summary of the quantitative DCE- and DWI MRI data, showing a significantly lower Ktrans in the CALR relative to the CALS cohort. Data are the individual Ktrans and ADC measurements for each tumor, and the cohort mean ± 1 s.e.m., **p < 0.01, Mann-Whitney test.

DW-MRI exploits the random diffusion of water molecules to measure differences in tissue cellularity, quantified through the measurement of the apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC, x106 mm2s−1) (47). Parametric ADC maps from both CALR and CALS tumors were generally homogeneous, but with discrete regions of markedly elevated water diffusion (Figure 2A). There was no significant difference in mean ADC between the two tumor types (Figure 2C).

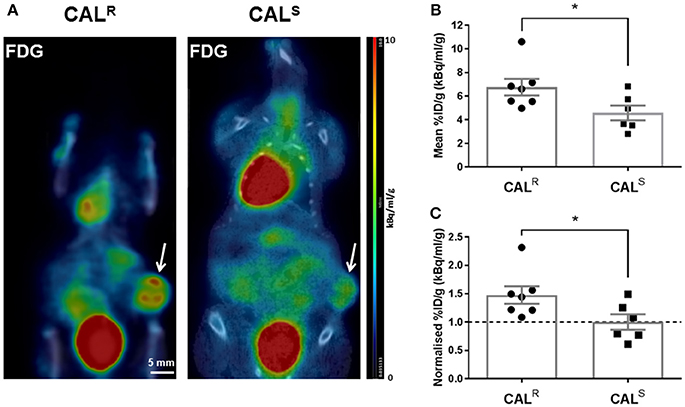

Representative whole body PET-CT images acquired from CALR and CALS tumor-bearing mice 1 h post injection of 18F-FDG are shown in Figure 3A. Greater uptake of 18F-FDG was apparent across the CALR xenografts, resulting in a significantly (p < 0.05) higher %ID/g in the CALR tumors compared to the CALS (Figure 3B). The relative difference between the CALR and CALS xenograft tracer uptake was quantified by normalizing the %ID/g results to the average value found in the CALS cohort, and also revealed a significant 48% (p < 0.05) higher relative uptake of 18F-FDG in the CALR tumors (Figure 3C).

Figure 3. (A) Coronal whole body PET-CT images of mice bearing CALR and CALS HNSCC xenografts (arrowed) acquired 1 h post injection of 18F-FDG. The images are shown on the same PET scale of 0–10% injected dose per gram (%ID/g). Marked uptake of 18F-FDG was also observed in the heart and bladder. (B,C) A significantly higher relative uptake of 18F-FDG was determined in the CALR cohort compared to the CALS tumors. Data are the individual (B) %ID/g and (C) normalized %ID/g for each tumor (relative to the average of the CALS cohort), and the cohort mean ± 1 s.e.m., *p < 0.05, Student's t-test.

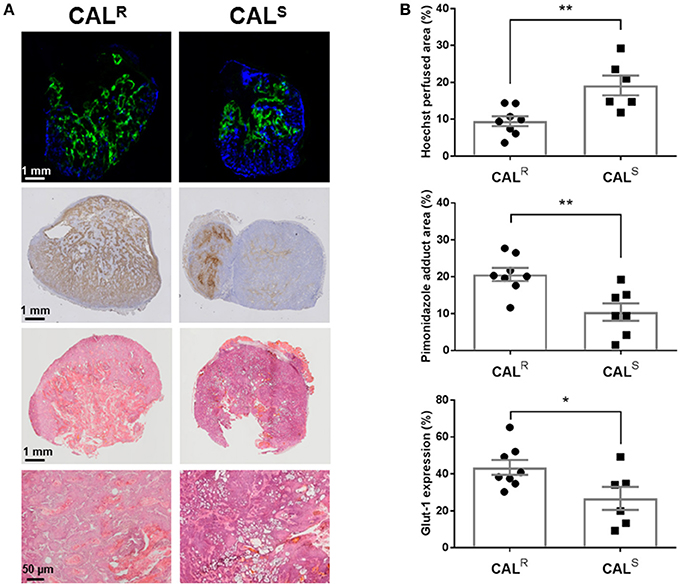

Composite fluorescence images of Hoechst 33342 and pimonidazole adducts, and bright field images of Glut-1 expression, in whole sections from CALR and CALS tumors, are shown in Figure 4A. Spatially, uptake of the perfusion marker Hoechst 33342 was primarily associated with the periphery of both tumor types, with hypoxic regions, as revealed by pimonidazole adduct formation, more heterogeneously distributed and predominantly located in the tumor core. Abundant Glut-1 expression was apparent across the CALR tumors, but more localized in the CALS xenografts. Quantitation of the pathology showed significantly (p < 0.01) lower perfusion, and significantly greater hypoxia (p < 0.01) and Glut-1 expression (p < 0.05) in the CALR tumors relative to the CALS cohort (Figure 4B). H&E staining revealed abundant vesicle formation in both the CALR and CALS tumors (Figure 4A). There was no significant difference in cellular density between the two tumor types [CALR 45 ± 3 nuclei/0.01 mm2 (n = 7), CALS 49 ± 3 nuclei/0.01 mm2 (n = 5)].

Figure 4. (A) Composite fluorescence images of Hoechst 33342 uptake (blue, perfusion) and pimonidazole adduct formation (green, hypoxia), and bright field images of Glut-1 expression (brown) and H&E staining, acquired from whole sections of representative CALR and CALS HNSCC xenografts. High magnification (x200) images from H&E stained sections are also shown. (B) Summary of quantitative differences in perfused tumor vessels, hypoxia and Glut-1 expression in the CALR and CALS tumors. Significantly lower Hoechst 33342 uptake, and significantly greater pimonidazole adduct formation and Glut-1 expression, was found in the CALR tumors relative to the CALS cohort. Data are the individual measurements of Hoechst perfused area (%), pimonidazole adduct area (%) and Glut-1 expression (%) for each tumor, and the cohort mean ± 1 s.e.m., **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05, Student's t-test.

Resistance is one of the major reasons for the failure of targeted cancer drugs. The initial response and subsequent relapse of HNSCC patients treated with EGFR TKIs is well documented (13, 14). Methods that can accurately predict which HNSCC patients will benefit from EGFR-targeted therapies, and inform on response, would positively impact on treatment planning in this patient population. To this end, we evaluated MRI and PET-derived imaging biomarkers in CALR and CALS HNSCC xenografts to identify and characterize any phenotypic differences in vivo associated with differential sensitivity to EGFR TKIs (33).

Tumor hypoxia is a well-established cause of treatment resistance, adversely affects the prognosis of HNSCC (21, 22), and moderates the expression and activation of EGFR (26). Both intrinsic susceptibility and oxygen-enhanced MRI are being actively exploited for spatially mapping tumor hypoxia in vivo (36, 45, 48–50). Oxygen inhalation induced a reduction in of both CALR and CALS xenografts, a consequence of a reduction in paramagnetic deoxyhaemoglobin in perfused tumor blood vessels. The reduction in was significantly smaller in the more aggressive CALR xenografts, consistent with their having relatively more impaired haemodynamic (functional) vasculature, and was confirmed histologically by their significantly lower uptake of Hoechst 33342. Hyperoxia increased R1 in both CALR and CALS xenografts to a similar extent reported in other tumor models (36, 48, 49, 51, 52). The low magnitude of this response suggests that these HNSCC xenografts are largely refractory to hyperoxia-induced changes in R1 and hence hypoxic (36, 48, 49). There was no relationship between and ΔR1 across the CALR and CALS tumors. As expected, extensive hypoxia was histologically evident in both CALR and CALS HNSCC xenografts, with significantly greater pimonidazole adduct formation determined in the CALR tumors. These data suggest that diminished hyperoxia-induced is associated with a more drug resistant phenotype, and re-iterates the contribution of hypoxia in exacerbating resistance to anti-EGFR therapies (26, 27).

The vascular patency and cellularity of CALR and CALS xenografts was interrogated using DCE- and DW-MRI respectively. The DCE-MRI biomarkers Ktrans, IAUGC60 and EF all indicated significantly lower vascular permeability/perfusion in the more hypoxic CALR xenografts, aligning with the lower hyperoxia-induced response and reduced Hoechst 33342 uptake seen in these tumors. The CALR phenotype is consistent with clinical data showing that DCE-MRI estimates of perfusion inversely correlate with pimonidazole adduct formation, and that relatively high pre-treatment Ktrans is associated with good response, in patients with HNSCC (53, 54). Whilst reduced tumor perfusion/permeability measured by DCE-MRI may thus be indicative of resistance to EGFR antagonists, it also reflects diminished drug delivery and hence response. DW-MRI revealed no significant difference in ADC between the CALR and CALS xenografts, and H&E staining confirmed no overall difference in cellular density. A recent study in HNSCC patients showed that pre-treatment ADC was unable to distinguish between eventual responders and non-responders to chemotherapy (55). Discrete areas of elevated ADC were detectable in both CALR and CALS xenografts, consistent with vesicle formation previously ascribed to the CAL 27 model (56).

As with many aggressive tumors, HNSCCs exhibit high rates of glycolysis to fulfill their energy requirements (57, 58). 18F-FDG PET has been widely used to visualize increased glycolysis in HNSCC in vivo (59). Accordingly, 18F-FDG uptake was clearly detected in both CALR and CALS xenografts. Significantly greater uptake of 18F-FDG was determined in the CALR tumors, and associated with greater Glut-1 expression, as determined by IHC. Elevated levels of lactate have also been reported in CALR, relative to CALS, tumors (60). Together these data are consistent with EGFR TKI-resistance being associated with a switch to a more glycolytic metabolism in vivo. Tumor adaptation to treatment with EGFR antagonists thus involves metabolic reprogramming in HNSCC cells, enabling them to survive in vivo despite an impaired functional vasculature and hypoxic microenvironment.

Collectively, the data herein suggest that a multi-modal, multiparametric MRI/PET imaging strategy, incorporating intrinsic susceptibility and DCE-MRI with 18F-FDG PET, may be useful in correctly identifying response/resistance to TKIs in patients with HNSCC. Such integrated approaches are already being used clinically to assess the degree and spatial distribution of perfusion, hypoxia and metabolism in HNSCC, and are being facilitated by new hybrid PET/MR technology and associated data fusion (61–63). Incorporation of quantitative measurements using intrinsic susceptibility MRI into clinical scanning protocols is relatively straightforward, and tumor is being actively investigated as an exploratory imaging biomarker of hypoxia in patients with HNSCC (64).

Whilst this study has focused on characterizing the radiological phenotype associated with resistance to EGFR TKIs in xenografts, the same array of imaging biomarkers may inform on tumor response in patients with HNSCC. In support of this, several pre-clinical imaging investigations have reported improved tumor oxygenation (65), perfusion/permeability and water diffusivity (66, 67), and reduced 18F-FDG uptake (68), following treatment with gefitinib monotherapy or in combination with chemo/radiation (69).

In summary, we have shown that xenografts established from HNSCC cells resistant to EGFR TKIs are more hypoxic, poorly perfused and more glycolytic than those sensitive to EGFR inhibitors, and that these differences can be visualized and quantified non-invasively in vivo using functional MRI and PET imaging. These imaging techniques are either routinely being used in the clinic or are under active development, so adoption of a multi-modal, multiparametric imaging strategy to assess HNSCC response and resistance to EGFR inhibition would enhance expedient treatment selection and scheduling for individual patients.

LB and CB: study concepts. LB, AS, JP, JB, CB, and SR: study design. LB, AS, JP, and GB: data acquisition. LB, JP, JB, EL, YJ, and TS: quality control of data and algorithms. LB, AS, JP, JB, EL, YJ, TS, CB, and SR: data analysis and interpretation. LB, JB, and SR: statistical analysis. LB, JP, JB, CB, and SR: manuscript preparation. LB, AS, JP, JB, EL, GB, YJ, TS, GK-M, ML, and SE: manuscript editing. CB and SR: manuscript review.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

We acknowledge the support received from a Medical Research Council (MRC) Centenary Award, the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council (EPSRC) [EP/H046410/1], The Oracle Cancer Trust, Children with Cancer UK [2014/176], Cancer Research UK (CR-UK) to the Cancer Therapeutics Unit [C309/A11566], CR-UK and EPSRC to the Cancer Imaging Centre, in association with the MRC and Department of Health (England) [C1060/A10334, C1060/A16464], and NHS funding to the NIHR Biomedical Research Centre at The Royal Marsden and the ICR. We thank Allan Thornhill and his staff for animal maintenance.

1. Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Dikshit R, Eser S, Mathers C, Rebelo, M, et al. Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: sources, methods and major patterns in GLOBOCAN 2012. Int J Cancer (2015) 136:E359–86. doi: 10.1002/ijc.29210

2. Welsh L, Panek R, McQuaid D, Dunlop A, Schmidt M, Riddell A, et al. Prospective, longitudinal, multi-modal functional imaging for radical chemo-IMRT treatment of locally advanced head and neck cancer: the INSIGHT study. Radiat Oncol. (2015) 10:112. doi: 10.1186/s13014-015-0415-7

3. Argiris A, Karamouzis MV, Raben D, Ferris RL. Head and neck cancer. Lancet (2008) 371:1695–709. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(08)60728-x

4. Sacco AG, Cohen EE. Current treatment options for recurrent or metastatic head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. (2015) 33:3305–13. doi: 10.1200/jco.2015.62.0963

5. Box C, Zimmermann M, Eccles S. Molecular markers of response and resistance to EGFR inhibitors in head and neck cancers. Front Biosci. (2013) 18:520–42. doi: 10.2741/4118

6. Arteaga CL, Engelman JA. ERBB receptors: from oncogene discovery to basic science to mechanism-based cancer therapeutics. Cancer Cell (2014) 25:282–303. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2014.02.025

7. Nijkamp MM, Span PN, Bussink J, Kaanders JH. Interaction of EGFR with the tumour microenvironment: Implications for radiation treatment. Radiother Oncol. (2013) 108:17–23. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2013.05.006

8. O-Charoenrat P, Rhys-Evans PH, Archer DJ, Eccles SA. C-erbB receptors in squamous cell carcinomas of the head and neck: clinical significance and correlation with matrix metalloproteinases and vascular endothelial growth factors. Oral Oncol. (2002) 38:73–80. doi: 10.1016/S1368-8375(01)00029-X

9. Bonner JA, Harari PM, Giralt J, Azarnia N, Shin DM, Cohen RB, et al. Radiotherapy plus cetuximab for squamous-cell carcinoma of the head and neck. N Engl J Med. (2006) 354:567–78. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa053422

10. Licitra L, Mesia R, Rivera F, Remenár E, Hitt R, Erfán J, et al. Evaluation of EGFR gene copy number as a predictive biomarker for the efficacy of cetuximab in combination with chemotherapy in the first-line treatment of recurrent and/or metastatic squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck: EXTREME study. Ann Oncol. (2011) 22:1078–87. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdq588

11. Chen LF, Cohen EE, Grandis JR. New strategies in head and neck cancer: understanding resistance to epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitors. Clin Cancer Res. (2010) 16:2489–95. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.Ccr-09-2318

12. Machiels J-PH, Haddad RI, Fayette J, Licitra LF, Tahara M, Vermorken JB, et al. Afatinib versus methotrexate as second-line treatment in patients with recurrent or metastatic squamous-cell carcinoma of the head and neck progressing on or after platinum-based therapy (LUX-Head & Neck 1): an open-label, randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. (2015) 16:583–94. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(15)70124-5

13. Wheeler DL, Dunn EF, Harari PM. Understanding resistance to EGFR inhibitors - impact on future treatment strategies. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. (2010) 7:493–507. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2010.97

14. Leemans CR, Braakhuis BJM, Brakenhoff RH. The molecular biology of head and neck cancer. Nat Rev Cancer (2011) 11:9–22. doi: 10.1038/nrc2982

15. Chong CR, Janne PA. The quest to overcome resistance to EGFR-targeted therapies in cancer. Nat Med. (2013) 19:1389–400. doi: 10.1038/nm.3388

16. Jackman D, Pao W, Riely GJ, Engelman JA, Kris MG, Jänne PA, et al. Clinical definition of acquired resistance to epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors in non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. (2010) 28:357–60. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.24.7049

17. Cancer Genome Atlas Network Comprehensive genomic characterization of head and neck squamous cell carcinomas. Nature (2015) 517:576–82. doi: 10.1038/nature14129

18. Ang KK, Zhang Q, Rosenthal DI, Nguyen-Tan PF, Sherman EJ, Weber RS, et al. Randomized phase III trial of concurrent accelerated radiation plus cisplatin with or without cetuximab for stage III to IV head and neck carcinoma: RTOG 0522. J Clin Oncol. (2014) 32:2940–50. doi: 10.1200/jco.2013.53.5633

19. Amin S, Bathe OF. Response biomarkers: re-envisioning the approach to tailoring drug therapy for cancer. BMC Cancer (2016) 16:850. doi: 10.1186/s12885-016-2886-9

20. Chapman CH, Saba NF, Yom SS. Targeting epidermal growth factor receptor for head and neck squamous cell carcinoma: still lost in translation? Ann Transl Med. (2016) 4:80. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2305-5839.2016.01.01

21. Brizel DM, Sibley GS, Prosnitz LR, Scher RL, Dewhirst MW. Tumor hypoxia adversely affects the prognosis of carcinoma of the head and neck. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. (1997) 38:285–9.

22. Nordsmark M, Bentzen SM, Rudat V, Brizel D, Lartigau E, Stadler P, et al. Prognostic value of tumor oxygenation in 397 head and neck tumors after primary radiation therapy. An international multi-center study. Radiother Oncol. (2005) 77:18–24. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2005.06.038

23. Sasabe E, Tatemoto Y, Li D, Yamamoto T, Osaki T. Mechanism of HIF-1α-dependent suppression of hypoxia-induced apoptosis in squamous cell carcinoma cells. Cancer Sci. (2005) 96:394–402. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2005.00065.x

24. Zheng Y, Ni Y, Huang X, Wang Z, Han W. Overexpression of HIF-1α indicates a poor prognosis in tongue carcinoma and may be associated with tumour metastasis. Oncol Lett. (2013) 5:1285–9. doi: 10.3892/ol.2013.1185

25. Wouters A, Boeckx C, Vermorken JB, Van den Weyngaert D, Peeters, M, Lardon F. The intriguing interplay between therapies targeting the epidermal growth factor receptor, the hypoxic microenvironment and hypoxia-inducible factors. Curr Pharm Des. (2013) 19:907–17. doi: 10.1186/s13104-015-1197-6

26. Hoogsteen IJ, Marres HAM, van den Hoogen FJA, Rijken PFJW, Lok J, Bussink J, et al. Expression of EGFR under tumor hypoxia: identification of a subpopulation of tumor cells responsible for aggressiveness and treatment resistance. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. (2012) 84:807–14. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2012.01.002

27. Mayer A, Zahnreich S, Brieger J, Vaupel P, Schmidberger H. Downregulation of EGFR in hypoxic, diffusion-limited areas of squamous cell carcinomas of the head and neck. Br J Cancer (2016) 115:1351–8. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2016.336

28. Garvalov BK, Foss F, Henze A-T, Bethani I, Gräf-Höchst S, Singh D, et al. PHD3 regulates EGFR internalization and signalling in tumours. Nature Commun. (2014) 5:5577. doi: 10.1038/ncomms6577

29. Michaelis LC, Ratain MJ. Measuring response in a post-RECIST world: from black and white to shades of grey. Nat Rev Cancer (2006) 6:409–14. doi: 10.1038/nrc1883

30. O'Connor JPB, Aboagye EO, Adams JE, Aerts HJWL, Barrington SF, Beer AJ, et al. Imaging biomarker roadmap for cancer studies. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. (2017) 14:169–86. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2016.162

31. Hermans R. Head and neck cancer: how imaging predicts treatment outcome. Cancer Imag. (2006) 6:S145–53. doi: 10.1102/1470-7330.2006.9028

32. Horsman MR, Mortensen LS, Petersen JB, Busk M, Overgaard J. Imaging hypoxia to improve radiotherapy outcome. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. (2012) 9:674–87. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2012.171

33. Box C, Mendiola M, Gowan S, Box GM, Valenti M, Brandon ADH, et al. A novel serum protein signature associated with resistance to epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Eur J Cancer (2013) 49:2512–21. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2013.03.011

34. Workman P, Aboagye EO, Balkwill F, Balmain A, Bruder G, Chaplin DJ, et al. Guidelines for the welfare and use of animals in cancer research. Br J Cancer (2010) 102:1555–77. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605642

35. Kilkenny C, Browne WJ, Cuthill IC, Emerson M, Altman DG. Improving bioscience research reporting: the ARRIVE guidelines for reporting animal research. PLoS Biol. (2010) 8:e1000412. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000412

36. Burrell JS, Walker-Samuel S, Baker LCJ, Boult JKR, Jamin Y, Halliday J, et al. Exploring ΔR and ΔR1 as imaging biomarkers of tumour oxygenation. J Magn Reson Imaging (2013) 38:429–34. doi: 10.1002/jmri.23987

37. Baker LCJ, Boult JKR, Thomas M, Koehler A, Nayak T, Tessier J, et al. Acute tumour response to a bispecific Ang-2-VEGF-A antibody: insights from multiparametric MRI and gene expression profiling. Br J Cancer (2016) 115:691–702. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2016.236

38. Henderson E, Rutt BK, Lee TY. Temporal sampling requirements for the tracer kinetics modeling of breast disease. Magn Reson Imaging (1998) 16:1057–73.

39. Walker-Samuel S, Orton M, McPhail LD, Boult JKR, Box G, Eccles SA, et al. Bayesian estimation of changes in transverse relaxation rates. Magn Reson Med. (2010) 64:914–21. doi: 10.1002/mrm.22478

40. Walker-Samuel S, Orton M, McPhail LD, Robinson SP. Robust estimation of the apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) in heterogeneous solid tumors. Magn Reson Med. (2009) 62:420–9. doi: 10.1002/mrm.22014

41. Fueger BJ, Czernin J, Hildebrandt I, Tran C, Halpern BS, Stout D, et al. Impact of animal handling on the results of 18F-FDG PET studies in mice. J Nucl Med. (2006) 47(6):999–1006.

42. Spinks TJ, Karia D, Leach MO, Flux G. Quantitative PET and SPECT performance characteristics of the Albira Trimodal pre-clinical tomograph. Phys Med Biol. (2014) 59:715–31. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/59/3/715

43. Baker LC, Boult JK, Walker-Samuel S, Chung YL, Jamin Y, Ashcroft M, et al. The HIF-pathway inhibitor NSC-134754 induces metabolic changes and anti-tumour activity while maintaining vascular function. Br J Cancer (2012) 106:1638–47. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2012.131

44. Schnapauff D, Zeile M, Niederhagen MB, Fleige B, Tunn P-U Hamm B, et al. Diffusion-weighted echo-planar magnetic resonance imaging for the assessment of tumor cellularity in patients with soft-tissue sarcomas. J Magn Reson Imaging (2009) 29:1355–9. doi: 10.1002/jmri.21755

45. Baker LCJ, Boult JKR, Jamin Y, Gilmour LD, Walker-Samuel S, Burrell JS, et al. Evaluation and immunohistochemical qualification of carbogen-induced ΔR as a noninvasive imaging biomarker of improved tumor oxygenation. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. (2013) 87:160–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2013.04.051

46. Leach MO, Brindle KM, Evelhoch JL, Griffiths JR, Horsman MR, Jackson A, et al. The assessment of antiangiogenic and antivascular therapies in early-stage clinical trials using magnetic resonance imaging: issues and recommendations. Br J Cancer (2005) 92:1599–610. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602550

47. Taouli B, Beer AJ, Chenevert T, Collins D, Lehman C, Matos C, et al. Diffusion-weighted imaging outside the brain: Consensus statement from an ISMRM-sponsored workshop. J Magn Reson Imaging (2016) 44:521–40. doi: 10.1002/jmri.25196

48. O'Connor JPB, Boult JKR, Jamin Y, Babur M, Finegan KG, Williams KJ, et al. Oxygen-enhanced MRI accurately identifies, quantifies, and maps tumor hypoxia in preclinical cancer models. Cancer Res. (2016) 76:787–95. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.can-15-2062

49. Linnik IV, Scott MLJ, Holliday KF, Woodhouse N, Waterton JC, O'Connor JPB, et al. Noninvasive tumor hypoxia measurement using magnetic resonance imaging in murine U87 glioma xenografts and in patients with glioblastoma. Magn Reson Med. (2014) 71:1854–62. doi: 10.1002/mrm.24826

50. Little RA, Jamin Y, Boult JKR, Naish JH, Watson Y, Cheung S, et al. Mapping hypoxia in renal carcinoma with oxygen-enhanced MRI: comparison with intrinsic susceptibility MRI and pathology. Radiology (2018). doi: 10.1148/radiol.2018171531. [Epub ahead of print].

51. Winter JD, Akens MK, Cheng H-L. Quantitative MRI assessment of VX2 tumour oxygenation changes in response to hyperoxia and hypercapnia. Phys Med Biol. (2011) 56:1225–42. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/56/5/001

52. Hallac RR, Zhou H, Pidikiti R, Song K, Stojadinovic S, Zhao D, et al. Correlations of noninvasive BOLD and TOLD MRI with pO2 and relevance to tumor radiation response. Magn Reson Med. (2014) 71:1863–73. doi: 10.1002/mrm.24846

53. Donaldson SB, Betts G, Bonington SC, Homer JJ, Slevin NJ, Kershaw LE, et al. Perfusion estimated with rapid dynamic contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging correlates inversely with vascular endothelial growth factor expression and pimonidazole staining in head-and-neck cancer: a pilot study. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. (2011) 81:1176–83. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2010.09.039

54. Ng S-H, Lin C-Y, Chan S-C, Yen T-C, Liao C-T, Chang JT-C, et al. Dynamic contrast-enhanced MR imaging predicts local control in oropharyngeal or hypopharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma treated with chemoradiotherapy. PLoS ONE (2013) 8:e72230. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0072230

55. Wong KH, Panek R, Welsh L, Mcquaid D, Dunlop A, Riddell A, et al. The predictive value of early assessment after 1 cycle of induction chemotherapy with 18F-FDG PET/CT and diffusion-weighted MRI for response to radical chemoradiotherapy in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. J Nucl Med. (2016) 57:1843–50. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.116.174433

56. Jiang L, Ji N, Zhou Y, Li J, Liu X, Wang Z, et al. CAL 27 is an oral adenosquamous carcinoma cell line. Oral Oncol. (2009) 45:e204-e7. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2009.06.001

57. Sandulache VC, Ow TJ, Pickering CR, Frederick MJ, Zhou G, Fokt I, et al. Glucose, not glutamine, is the dominant energy source required for proliferation and survival of head and neck squamous carcinoma cells. Cancer (2011) 117:2926–38. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25868

58. Richtsmeier WJ, Dauchy R, Sauer LA. In vivo nutrient uptake by head and neck cancers. Cancer Res. (1987) 47:5230–3.

59. Paidpally V, Chirindel A, Lam S, Agrawal N, Quon H, Subramaniam RM. FDG-PET/CT imaging biomarkers in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Imag Med. (2012) 4:633–47. doi: 10.2217/iim.12.60

60. Beloueche-Babari M, Box C, Arunan V, Parkes HG, Valenti M, De Haven Brandon A, et al. Acquired resistance to EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors alters the metabolism of human head and neck squamous carcinoma cells and xenograft tumours. Br J Cancer (2015) 112:1206–14. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2015.86

61. Surov A, Stumpp P, Meyer HJ, Gawlitza M, Höhn A-K Boehm A, et al. Simultaneous 18F-FDG-PET/MRI: Associations between diffusion, glucose metabolism and histopathological parameters in patients with head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Oral Oncol. (2016) 58(Supplement C):14–20. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2016.04.009

62. Gawlitza M, Purz S, Kubiessa K, Boehm A, Barthel H, Kluge R, et al. In vivo correlation of glucose metabolism, cell density and microcirculatory parameters in patients with head and neck cancer: initial results using simultaneous PET/MRI. PLoS ONE (2015) 10:e0134749. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0134749

63. Jansen JFA, Schöder H, Lee NY, Stambuk HE, Wang Y, Fury MG, et al. Tumor metabolism and perfusion in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma: pretreatment multimodality imaging with 1H magnetic resonance spectroscopy, dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI, and [18F]FDG-PET. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. (2012) 82:299–307. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2010.11.022

64. Panek R, Welsh L, Dunlop A, Wong KH, Riddell AM, Koh D-M et al. Repeatability and sensitivity of T measurements in patients with head and neck squamous cell carcinoma at 3T. J Magn Reson Imaging (2016) 44:72–80. doi: 10.1002/jmri.25134

65. Karroum O, Kengen J, Gregoire V, Gallez B, Jordan BF. Tumor reoxygenation following administration of the EGFR inhibitor, gefitinib, in experimental tumors. Adv Exp Med Biol. (2013) 789:265–71. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4614-7411-1

66. Kawano K, Hattori Y, Iwakura H, Akamizu T, Maitani Y. Combination therapy with gefitinib and doxorubicin inhibits tumor growth in transgenic mice with adrenal neuroblastoma. Cancer Med. (2013) 2:286–95. doi: 10.1002/cam4.76

67. Aliu SO, Wilmes LJ, Moasser MM, Hann BC, Li KL, Wang D, et al. MRI methods for evaluating the effects of tyrosine kinase inhibitor administration used to enhance chemotherapy efficiency in a breast tumor xenograft model. J Magn Reson Imaging (2009) 29:1071–9. doi: 10.1002/jmri.21737

68. Zhou LN, Wu N, Liang Y, Gao K, Li XY, Zhang LF. Monitoring response to gefitinib in nude mouse tumor xenografts by [18]F-FDG microPET-CT: correlation between [18]F-FDG uptake and pathological response. World J Surg Oncol. (2015) 13:111. doi: 10.1186/s12957-015-0505-x

Keywords: HNSCC, EGFR, resistance, imaging, MRI, PET

Citation: Baker LCJ, Sikka A, Price JM, Boult JKR, Lepicard EY, Box G, Jamin Y, Spinks TJ, Kramer-Marek G, Leach MO, Eccles SA, Box C and Robinson SP (2018) Evaluating Imaging Biomarkers of Acquired Resistance to Targeted EGFR Therapy in Xenograft Models of Human Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Front. Oncol. 8:271. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2018.00271

Received: 24 March 2018; Accepted: 02 July 2018;

Published: 23 July 2018.

Edited by:

Natalie Julie Serkova, School of Medicine, University of Colorado, United StatesReviewed by:

Ellen Ackerstaff, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, United StatesCopyright © 2018 Baker, Sikka, Price, Boult, Lepicard, Box, Jamin, Spinks, Kramer-Marek, Leach, Eccles, Box and Robinson. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Simon P. Robinson, c2ltb24ucm9iaW5zb25AaWNyLmFjLnVr

†Present Address: Arti Sikka, Department of Surgery and Cancer, Imperial College London, Hammersmith Hospital, London, United Kingdom

Jonathan M. Price, Southend University Hospital NHS Foundation Trust, Prittlewell Chase, Westcliff-on-Sea, Essex, United Kingdom

‡ These authors have contributed equally to this work.

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.