- 1Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, Cumming School of Medicine, University of Calgary, Calgary, AB, Canada

- 2Department of Medical Genetics, Cumming School of Medicine, University of Calgary, Calgary, AB, Canada

- 3Alberta Children's Hospital Research Institute, University of Calgary, Calgary, AB, Canada

Autosomal recessive primary microcephaly (MCPH; “small head syndrome”) is a rare, heterogeneous disease arising from the decreased production of neurons during brain development. As of August 2020, the Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM) database lists 25 genes (involved in molecular processes such as centriole biogenesis, microtubule dynamics, spindle positioning, DNA repair, transcriptional regulation, Wnt signaling, and cell cycle checkpoints) that are implicated in causing MCPH. Many of these 25 genes were only discovered in the last 10 years following advances in exome and genome sequencing that have improved our ability to identify disease-causing variants. Despite these advances, many patients still lack a genetic diagnosis. This demonstrates a need to understand in greater detail the molecular mechanisms and genetics underlying MCPH. Here, we briefly review the molecular functions of each MCPH gene and how their loss disrupts the neurogenesis program, ultimately demonstrating that microcephaly arises from cell cycle dysregulation. We also explore the current issues in the genetic basis and clinical presentation of MCPH as additional avenues of improving gene/variant prioritization. Ultimately, we illustrate that the detailed exploration of the etiology and inheritance of MCPH improves the predictive power in identifying previously unknown MCPH candidates and diagnosing microcephalic patients.

Introduction

Autosomal recessive primary microcephaly (MCPH) is a rare, heterogeneous disorder characterized by an occipitofrontal diameter >2 or 3 standard deviations below the mean at birth, after accounting for sex and ethnicity. MCPH patients typically have a simplified cerebral cortical gyral pattern (lissencephaly) although overall brain architecture is generally normal. MCPH is also frequently associated with other clinical features such as intellectual impairment, short stature, and mild seizures—since these features frequently overlap with other syndromes, it is likely that MCPH is part of a disease spectrum. The rate of incidence varies between 1 in 10,000, in populations where consanguineous marriages are common, and 1 in 250,000 in non-consanguineous populations (1, 2). Although there are some examples of dominantly inherited primary microcephaly, it is typically inherited in an autosomal recessive manner.

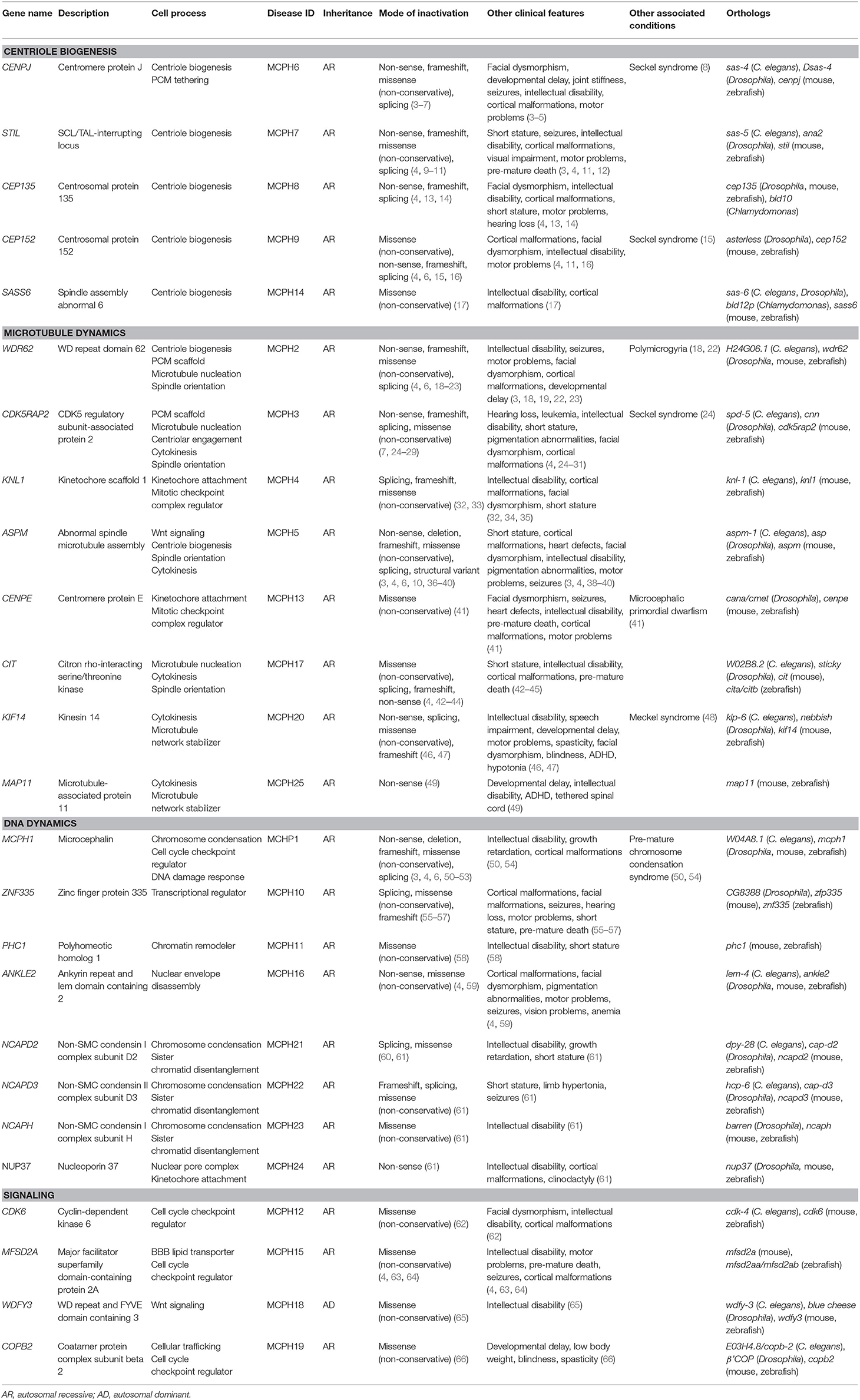

There are currently 25 MCPH-associated genes listed in the Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM) database (accessed as of April 2020): MCPH1, WDR62, CDK5RAP2, KNL1, ASPM, CENPJ, STIL, CEP135, CEP152, ZNF335, PHC1, CDK6, CENPE, SASS6, MFSD2A, ANKLE2, CIT, WDFY3, COPB2, KIF14, NCAPD2, NCAPD3, NCAPH, NUP37, and MAP11 (MCPH1–25, respectively) (Table 1). Some of these genes cause microcephaly in combination with other disease features (syndromic microcephaly), however, we will focus on their involvement in primary microcephaly in this review. Because of its heterogeneous nature, diagnosing patients can be a challenging endeavor. Gene panel testing is effective at identifying the more common genetic variants that cause MCPH but becomes impractical with the continual updates required as new genes and variants are discovered. For instance, a recent case report describes a patient with primary microcephaly in which several gene panels were unable to find the disease-causing variant, including the autosomal recessive primary microcephaly Tier 2 sequencing and deletion/duplication panel that screens for several MCPH genes (67). Once whole exome sequencing (WES) was performed on this individual, a homozygous variant in the DNA damage response gene, TTI2, was found, representing a novel MCPH locus. Accordingly, it then makes sense to turn to exome or whole genome sequencing (WGS) in order to diagnose patients; however, although these techniques give us a more complete picture of the genome, they do not always immediately provide answers. Exome sequencing of MCPH patients has been shown to have a diagnostic yield of only 29%, with a particular bias for identifying ASPM mutations (68). Although that number does increase to about 50% with WGS, this still leaves half of MCPH patients and their families without answers (69). One issue is that WES or WGS typically results in thousands of variants, making the variant prioritization process a daunting endeavor. Therefore, while there is an obvious need to improve our analysis of WES and WGS in order to identify disease-causing variants, it is also necessary to improve our understanding of the causes of MCPH to be able to make new gene–disease associations.

The overall goal of this review is to describe different aspects of MCPH that impact our ability to discover new genes associated with MCPH and, consequently, to diagnose patients. To achieve this goal, we first demonstrate that MCPH arises from perturbations in cell cycle regulation by briefly highlighting the cellular role of microcephaly-associated proteins. Then, we discuss the genetics and evolution of these genes as further considerations in variant prioritization in patients. Throughout this, we provide examples that exemplify how a thorough understanding of the etiology and genetics of disease allows us to identify new disease-causing candidates. Finally, we will comment on a major question in the field—based on what we know about the etiology and genetics of MCPH, why do mutations result in a brain-specific phenotype? Altogether, we illustrate that multidisciplinary approaches facilitate the prioritization of MCPH variants in patients with unknown genetic causes.

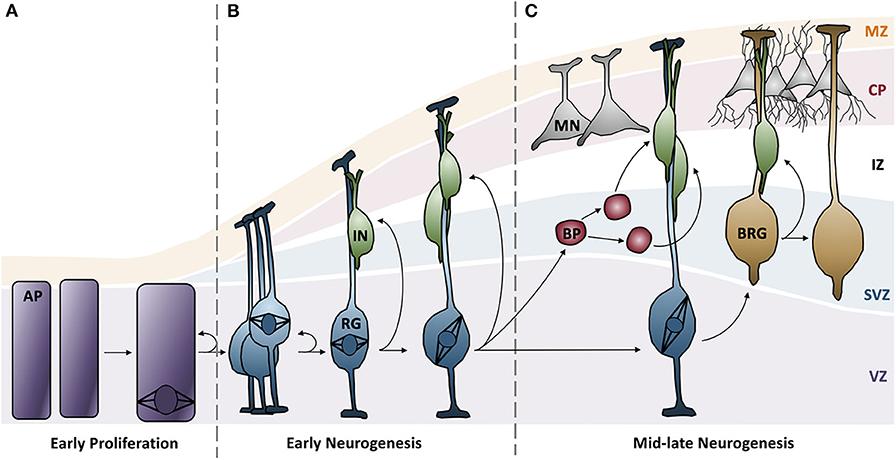

Dissecting the Etiology of Primary Microcephaly

MCPH is typically caused by a reduction in the number of neurons in the developing neocortex. Neurons are derived from apical progenitor cells (APs) in the ventricular zone (VZ) of the neocortex (70). In a brief overview, APs divide symmetrically to produce two progenitor cells in the proliferative phase. At the onset of neurogenesis, symmetric cell divisions are favored in order to generate a large pool of progenitor cells; the size of this pool is a good indicator of eventual brain size (Figure 1A) (71). In early neurogenesis phases, APs begin to express glial markers and adopt a radial glial cell (RG) fate; these cells have a highly polarized architecture and are able to divide symmetrically to generate more RGs or young neurons (Figure 1B) (70, 72). As neurogenesis continues, RGs begin to favor asymmetric cell divisions in order to generate more neurons and a secondary progenitor cell, termed basal progenitors (BPs) that localize to the subventricular zone (Figure 1C) (70). BPs serve to amplify the number of neurons that are formed per AP division.

Figure 1. Neurogenesis in the developing neocortex. (A) Apical progenitor cells in the ventricular zone undergo symmetrical proliferative divisions, generating a pool of progenitor cells. (B) Expression of glial markers causes progenitor cells to differentiate into radial glial cells, which can subsequently undergo symmentrical divisions to generate more radial glial cells or immature neurons. Distinct cortical layers begin to form: ventricular zone, subventricular zone, intermediate zone, cortical plate, and the marginal zone. (C) Radial glial cells favor asymmetric division to generate more diverse neuron types and basal progenitors, a secondary progenitor. Radial glial cells continue to differentiate into mature neurons and basal radial glia. AP, apical progenitors; BP, basal progenitors; BRG, basal radial glia; CP, cortical plate; IN, immature neurons; IZ, intermediate zone; MN, mature neurons; MZ, marginal zone; RG, radial glia; SVZ, subventricular zone; VZ, ventricular zone.

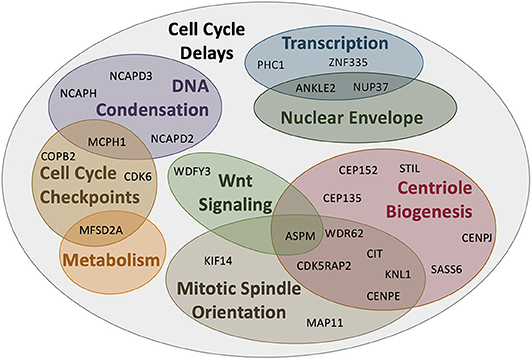

Based on this developmental model, there are a number of reasons why fewer neurons are produced in MCPH patients. There can be increased cell death of these neurons, an imbalance in the ratio of progenitor to differentiating cells (i.e., changes in asymmetric vs. symmetric cell divisions), changes in the timing of the cell divisions, or abnormal differentiation. However, although each of the MCPH-associated genes affects neuronal population size given their involvement in microcephaly, these genes are involved in a number of different cellular processes that seem rather unconnected. For instance, MCPH genes are involved in centriole biogenesis and regulation, DNA replication and division, cell division, signaling, mitotic spindle orientation, chromosomal condensation, DNA damage responses, microtubule dynamics, and transcriptional control (Figure 2). Despite these seemingly diverse cellular functions, there appears to be a common disease mechanism linking each of these processes—mutations in MCPH genes disrupt the timing of the neurogenic program. This can be modeled using the cell cycle exit fraction, which is the ratio of cells that take on a differentiated fate (i.e., become neurons) vs. those that remain in a proliferative state (73).

Figure 2. MCPH-associated proteins have overlapping cellular functions that affect cell cycle progression. Aberrant activity in any of these cellular functions would create delays in the timing of the cell cycle and overall proliferation through development. Several proteins act across more than one functional pathway (i.e., centriole biogenesis and mitotic spindle orientation), further delaying the cell cycle at each functionally relevant timepoint.

To give context to readers that may not be familiar with the cellular function of MCPH genes, this review will begin by demonstrating that mutations in the highlighted genes affect cell cycle timing in some way, effectively increasing the cell cycle exit fraction, indicating that MCPH is a disease arising from cell cycle dysregulation (Figure 2). The cell cycle checkpoints ensure that the cell is appropriately prepared for cell division; they are activated by events such as DNA damage (G2 checkpoint), unattached kinetochores (M checkpoint), limited resources (G1 checkpoint), and/or signaling cues (G1 checkpoint) [reviewed in Pucci et al. (74)]. These checkpoints delay the onset of the next phase to permit the cell to correct any errors that arise. If errors can be repaired, the cell continues to progress through the cell cycle, but if errors are incapable of being fixed, often due to mutations, the cell will often undergo apoptosis to prevent errors from being transmitted (74). Accordingly, not only do ongoing cell cycle delays produce fewer neurons, it is compounded by apoptosis, which further reduces the number of progenitors and neurons within the neocortex. Therefore, a disruption in cell cycle timing appears to be the common mode of pathogenesis underlying MCPH. Although we primarily focus on the described role of each protein encoded by the human MCPH genes to illustrate this model, we also draw from studies of orthologous genes in the murine, nematode, and fly models, as required.

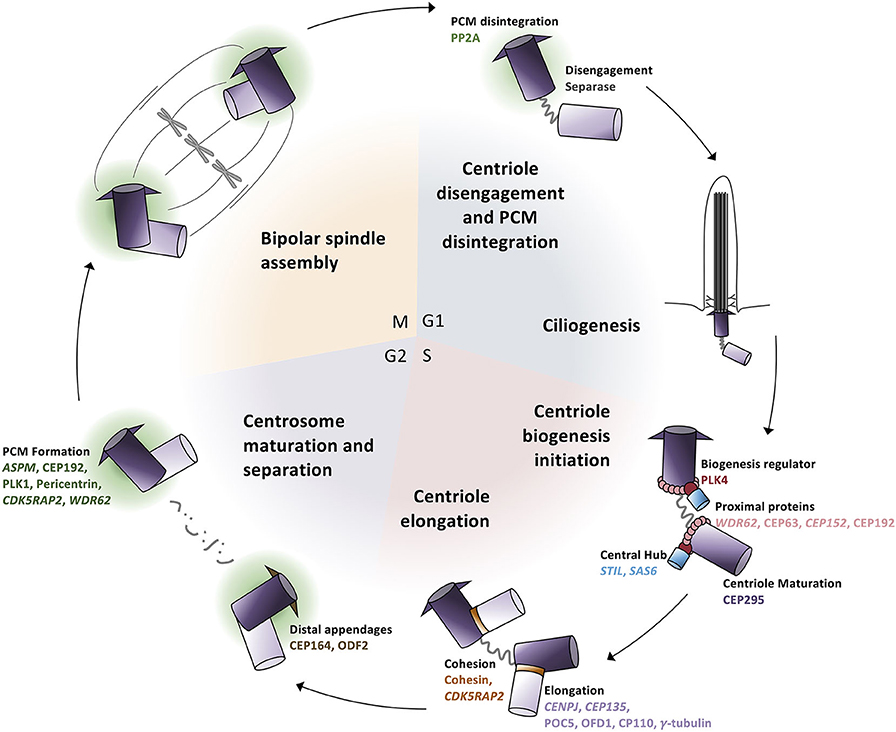

Centrosomes and the Cell Cycle

For many years, MCPH was considered a “centriolopathy” because most of the first genes implicated in causing the disease were involved in centriole biogenesis. Centrosomes are essential for establishing the mitotic spindle during cell division and nucleating the ciliary axoneme during quiescence. Centrosomes are composed of a pair of centrioles (termed mother and daughter centrioles) and associated pericentriolar material (PCM). Centriole biogenesis is tightly linked to the cell cycle (Figure 3). In G1, just after cell division, the two centrioles from one centrosome are loosely linked together. In S phase, this link weakens further and is proceeded by pro-centriole formation (i.e., new daughter centriole biogenesis). In G2, centrosome separation occurs and each new centrosome begins maturation. Finally, in mitosis, each centrosome travels to opposite sides of the cell during spindle formation in preparation for cell division. Therefore, there are four key processes essential in the centrosome cycle that are critical in terms of microcephaly: centriole biogenesis, centriole maturation, centriole tethering, and spindle formation. Variants in genes that are involved in these four key processes have recently been connected with MCPH (Table 1).

Figure 3. Centrosome biogenesis is linked to the cell cycle. (G1 phase) Centrioles disengage through both separase activity and pericentriolar material (PCM) degradation. The disengaged centriole pair becomes the cilium basal body and acts as the template for ciliogenesis. (S phase) The daughter centriole becomes replication competent and centriole biogenesis is initiated by the recruitment of PLK4 which phosphorylates STIL to begin SAS6 recruitment to generate the central hub. Daughter centrioles elongate and remain attached to the mother centriole via cohesion. (G2 phase) Mother centrioles unlink and centrosome maturation begins with the development of the pericentriolar material and formation of distal appendages. (M phase) Centrosomes travel to opposite poles of the cell for spindle formation and attachment and cell division; each daughter cell contains one centrosome to repeat the cycle.

Centriole Biogenesis

To initiate the formation of daughter centrioles in G1–S phase, the original daughter centriole must first become duplication competent (i.e., must mature into a so-called “mother” centriole). Subsequently, a number of proteins are recruited to the proximal ends of the “grandmother” and “mother” centrioles (Figure 3). The scaffold protein WDR62 recruits CEP63 and CEP152, which form a ring-like structure at the mother centriole's proximal end, and triggers the recruitment of PLK4, a polo-like kinase known as the master regulator of centriole duplication, to the site of daughter centriole formation (75–79).

Following the recruitment of proteins to the mother centriole, PLK4 autophosphorylates itself concurrently with phosphorylating and recruiting STIL (80). PLK4 and STIL subsequently recruit SAS6 to form the template for the nascent daughter centriole (Figure 3). STIL and SAS6 oligomerize into a 9-fold symmetrical ring structure to form the unstable “cartwheel” central hub (80–82). Following central hub formation, proteins such as CENPJ and CEP135 are finally recruited, which aid in regulating and stabilizing central tube elongation and initiating singlet microtubules to assemble around the central hub (80, 83–87).

Centriole Maturation

The centrosome-associated pericentriolar material (PCM) is composed of a protein matrix and is responsible for anchoring and nucleating microtubules; just prior to mitosis, this matrix undergoes expansion. Master regulators of PCM maturation recruit coiled-coil proteins as well as the attachment of γ-tubulin to the centrosome by CDK5RAP2; these activities ensure the formation of a PCM scaffold that permits centrosomal microtubule nucleation, which is an essential step in astral microtubule formation (Figure 3) (88–93).

Similar to the centrioles themselves, PCM assembly and disassembly is tightly linked to the cell cycle. During mitotic exit, the dense PCM must disassociate in order to drive centriolar separation (disengagement); daughter centriole biogenesis cannot occur if the so-called “grand-mother” and “mother” centrioles fail to separate because they are entrapped within the PCM (94, 95). Several centrosomal effector molecules therefore become dephosphorylated to promote their destabilization and result in a fragmented PCM, which allows centriole biogenesis to occur (96, 97).

Centriole Tethering

Following mitosis, the mother and daughter centriole become disengaged such that the tight cohesin fiber connections between them loosen (95, 98). This requires PCM disintegration and separase protease activity. In G1, disengagement allows the mother centriole to become the basal body in order to nucleate the cilium but also licenses centriole biogenesis in S phase. The newly formed daughter centrioles are tightly bound (engaged) to the mother centriole via cohesin, which is maintained by CDK5RAP2 and functions to limit centriole biogenesis to once per cell cycle (99, 100). Finally, during mitosis, the two engaged centriole pairs (i.e., the centrosomes) lose their loose connection, become separated, and move to opposite sides of the cell where they begin mitotic spindle formation (Figure 3).

Spindle Formation

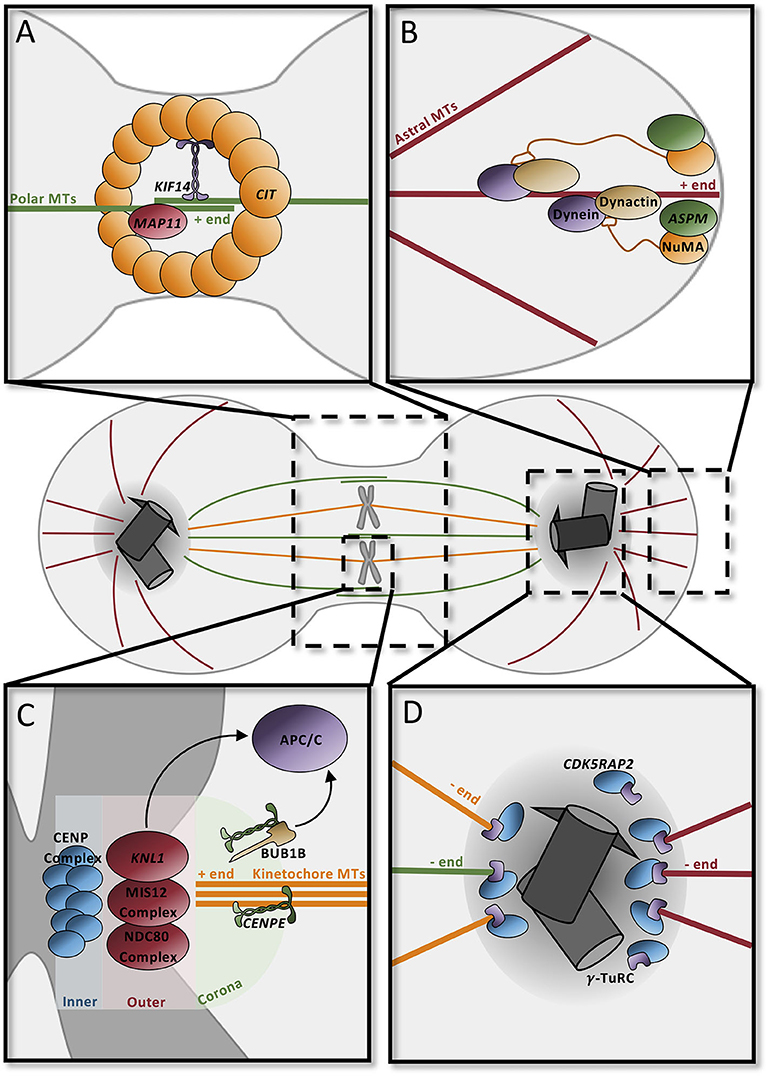

The mitotic spindle is responsible for the accurate segregation of chromosomes during cell division. The spindle depends heavily on dynamic microtubule activity for its function: astral microtubules connect the centrosome to the cell cortex, kinetochore microtubules connect the condensed chromosomes to the centrosome, and polar microtubules overlap at the central spindle to connect the two spindle poles (Figure 4). Each microtubule subtype performs specific tasks. Polar microtubules drive the separation of the two centrosomes, direct the positioning of the cleavage furrow, and promote abscission (Figure 4A). Astral microtubules serve to position the mitotic spindle and direct cleavage orientation (Figure 4B), while kinetochore microtubules are responsible for accurately segregating DNA to the opposite poles (Figure 4C). Predictably, many MCPH genes have roles in regulating spindle dynamics, including many of the genes that are involved in centriole biogenesis and PCM maturation (Figure 4D).

Figure 4. Microtubule dynamics orient the mitotic spindle and drive cell division. (A) Contractile ring component CIT at the midbody recruits KIF14 to the central spindle to stabilize the microtubule network. MAP11 promotes cell abscission at the midbody. (B) ASPM and NuMA at spindle poles recruit dynein–dynactin to astral microtubules to position spindles in the dividing cell. (C) The kinetochore, composed of three distinct layers (inner, outer, and corona), contains several proteins to securely attach microtubules. CENPE in the coronal layer binds microtubules through the motor domain; unbound CENPE signals through BUB1B to the APC/C to delay anaphase. The outer layer complex similarly binds the microtubule positive end; one of the components, KNL1, signals the APC/C to delay cycle if there is improper attachment at this layer. In the inner layer, the CENP complex binds the kinetochore to the condensed chromosome ensuring proper attachment for segregation. (D) Pericentriolar material scaffold is formed by CDK5RAP2 for microtubule nucleation by γ-tubulin at the centrosome. APC/C, anaphase promoting complex/cyclosome; MT, microtubules.

During anaphase, the highly abundant polar microtubules emanating from each of the spindle poles overlap centrally in order to form the stable central spindle (Figure 4). This structure is necessary to recruit proteins that position the cleavage furrow and trigger its contraction to form the midbody. Many of the centrosomal proteins that influence microtubule nucleation, such as ASPM, CDK5RAP2, and CIT, are recruited to the midbody during cytokinesis, highlighting the multifunctional roles of these proteins (101). In addition to these proteins, microtubule-associated proteins and their regulators also affect central spindle dynamics. CIT, which is a component of the contractile ring, recruits the microtubule-associated protein KIF14 to the central spindle, where it functions to stabilize the central spindle microtubule network and promote cytokinesis (Figure 4A) (102–105). MAP11 is similarly required at the midbody to promote abscission (49).

The astral microtubules in particular are essential for the orientation of the mitotic spindle (and thus cell division orientation). Rotation of the mitotic spindle depends on forces generated between the cell cortex and the astral microtubules. Minus-end-directed activity of a dynein–dynactin complex, coupled with the cortical anchoring of the astral microtubules, generates a pulling force which allows for rotation and positioning of the spindle (106–108). ASPM seems to be a major player in this process since it binds to nuclear mitotic apparatus (NuMA), which localizes to the spindle poles and the cortex, and subsequently recruits the dynein–dynactin complex to the spindle poles, where it acts as the force generator in spindle positioning (Figure 4B) (109–112).

The kinetochore microtubules are required for the faithful segregation of the chromosomes during cell division; aberrant segregation can lead to chromosomal instabilities or aneuploidy, which can be toxic to the cell. Under the “search and capture model,” microtubules emanating from the spindle poles seek out and attach to the heavily scaffolded kinetochore. The multilayered kinetochore is largely responsible for ensuring this correct attachment and for triggering cellular alarms when microtubules are not appropriately attached (Figure 4D). One of the outermost microtubule-capturing kinetochore components is the centromere-associated protein E (CENPE), which is a large, kinesin-like motor protein that binds to microtubules through its motor domain (113, 114). KNL1, which is located in a complex more interiorly in the kinetochore, is similarly required for microtubule binding (115). If microtubules are incorrectly attached to the kinetochore, then the spindle assembly checkpoint (SAC) will be activated, delaying mitosis until attachment has been corrected. For instance, microtubule-unbound CENPE binds to BUB1B and triggers its phosphorylation which leads to a “delay anaphase” signaling cascade that culminates on the anaphase-promoting complex/cyclosome (APC/C) (114, 116). Similarly, the KNL1 complex functions redundantly with CENPE to delay the cell cycle (117).

DNA Dynamics During the Cell Cycle

Similar to centrosomes, DNA dynamics are tightly linked to the cell cycle. At the onset of mitosis, one of the cell cycle checkpoints ensures that chromosomes have been accurately condensed and that breakdown of the nuclear envelope occurs; together, these permit the proper pairing of homologous chromosomes at the metaphase plate and the subsequent segregation of sister chromatids into the presumptive daughter cells during anaphase. Following mitosis, cells in G1 become transcriptionally active. Throughout the cell cycle, DNA is continually monitored for damage, which must be repaired in order for the cell to continue to progress through the cycle. Dysregulation of DNA dynamics is thus capable of creating delays in the cell cycle and affecting the overall trajectory of a cell within a developing system, such as the brain. Specifically, delays in the cell cycle of neural progenitors will reduce the proliferative pool and the subsequent number of differentiated neurons within the developing brain. Therefore, because of the tight link between DNA dynamics and cell cycle timing, variants in genes that affect chromosomal condensation, transcriptional regulation, DNA damage responses, and nuclear envelope breakdown are increasingly being implicated in causing MCPH (Table 1).

Condensation and Transcriptional Regulation

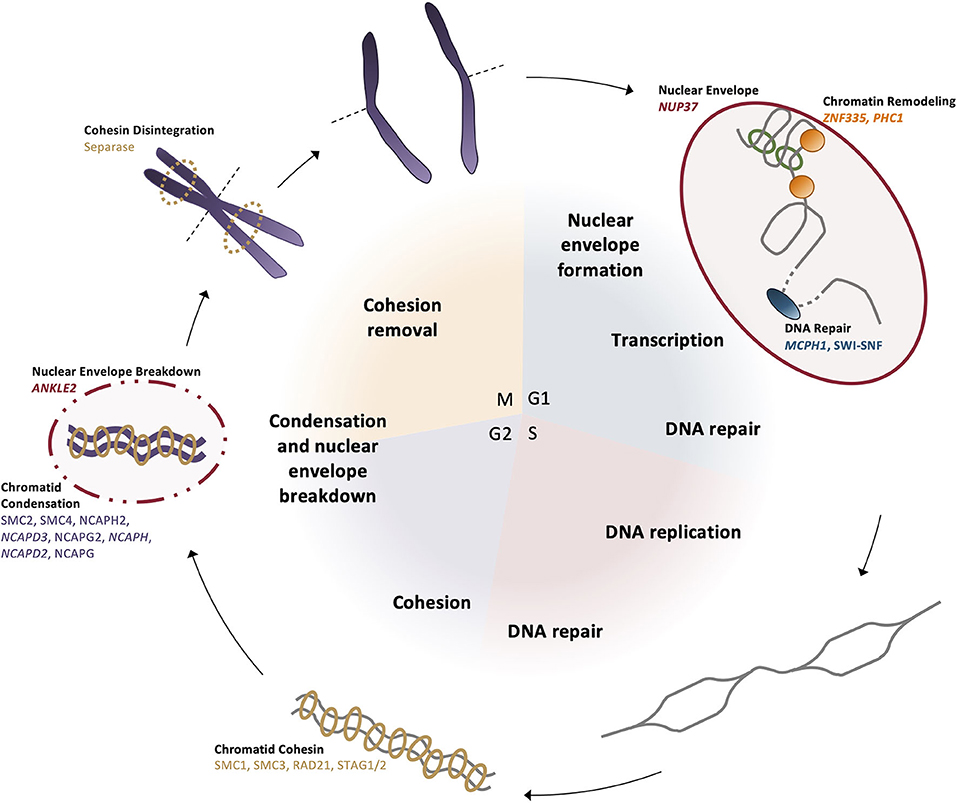

Chromosomal condensation is one mode by which transcription is regulated across cell types and throughout the cell cycle. The shift between heterochromatin and euchromatin regulates the genes that are accessible to transcriptional machinery, shifting the transcript profile of each cell. One MCPH gene, ZNF335, is an H3K4 methyltransferase that binds to heterochromatin upstream of the neuron-restrictive silencer factor (NRSF) locus in neural stem cells to prevent differentiation pathways; this brain-specific expression pattern is turned off during the dynamic remodeling in the transition to differentiation (Figure 5) (55). PHC1 also represses transcription through chromatin remodeling by ubiquitinating histone H2A to maintain condensation of specific genomic regions (58). Since the switch from proliferation to differentiation requires changes in gene regulation and expression, dynamic chromatin remodeling permits transcriptional machinery binding to various genomic regions related to cell cycle progression and differentiation.

Figure 5. DNA dynamics are linked to the cell cycle. (G1 phase) The nuclear envelope reforms after mitosis, then chromatin is positioned in the nucleus and remodeled for transcription by ZNF335 and PHC1. In preparation for synthesis and the G1 cell cycle checkpoint, DNA repair proteins correct any damage present in the genome. (S phase) Chromosomes undergo replication and repair proteins correct any errors or DNA breaks that occurred during the synthesis process. (G2 phase) Sister chromatids are brought together and bound by cohesin complexes. Prior to mitotic entry, condensin II begins the condensation of the chromatids as the negative regulator MCPH1 is broken down. (M phase) Nuclear envelope is broken down by ANKLE2 and homologous chromosomes align at the metaphase plate. Separase disintegrates the cohesin bonds between sister chromatids so they can be segregated to opposite poles before cytokinesis divides the daughter cells.

There are many nuclear proteins involved in reducing the length of the chromosomes, some of which are causative in primary microcephaly (118, 119). The primary complexes acting to further condense the chromosomes both laterally and axially are condensin I and condensin II, which share the same structural maintenance core (SMC) subunits but differ in their associated NCAP family subunits (Figure 5). In preparation for entry into mitosis, the SMC associates with NCAPH2, NCAPD3, and NCAPG2 to form condensin II in the nucleus, which localizes to the chromosomes and creates an axially rigid structure of interacting chromosome regions, shortening the overall length of the chromosomes (119, 120). Condensin II localization to the chromosomes is restricted to this phase, as throughout the rest of the cell cycle, it is negatively regulated by MCPH1 until condensation can be coupled with centriole duplication, ensuring that all necessary mitotic structures are formed by the end of G2 (50, 121). Lateral compaction occurs after nuclear envelope breakdown when the condensin I complex—including NCAPH and NCAPD2—can associate with the chromosomes to loop the chromatin around the established axial patterning created by condensin II (Figure 5) (122).

Beginning in S phase, the newly replicated sister chromatids must be connected through to the early mitotic stages, until finally at anaphase, sister chromatids are separated. Sister chromatid cohesion is mediated by the cohesin complexes, which also contain SMC molecules but differ in their accessory protein subunits (Figure 5). This ring-like complex encircles each of the sister chromatid pairs to ensure they are tethered together. At anaphase, the complex is degraded by the protease separase, which is the enzyme that facilitates centriolar disengagement, linking DNA dynamics and centrosome function through the cell cycle (123). This ensures that the sister chromatids are faithfully segregated, and each daughter cell contains identical DNA content. In the event that the cohesin complex pre-maturely dissociates, kinetochore-centromeric attachments fail to occur and genomic instability can result.

DNA Damage Response

Prior to synthesis and mitosis, the DNA damage response ensures the accurate passage of genomic information to both daughter cells; if the genome is damaged beyond a reparable threshold, the cell is instead sent into the apoptotic pathway to prevent aberrant cell function or growth and to maintain a healthy cell population. MCPH1 localizes to chromatin that has been damaged by ionizing radiation and prevents compaction of the chromatin at that locus by inhibiting the condensin II complex and, thus, mitotic onset until the repair machinery is able to correct the sequence (Figure 5) (124–126).

Nuclear Envelope

In interphase, the nuclear envelope is critical for the movement of proteins into and out of the nucleus, regulating transcription factor access to the genome and the proteins required for the transition to differentiation. NUP37 is a microcephaly-associated nucleoporin that encodes an essential component of the nuclear pore complex (NPC) (Figure 5). It is a component of the ring-shaped Y-complex on the surface of the nuclear envelope, creating much of the structure for the nuclear pore (127). The presence of the Y-complex is necessary for nuclear pore stability and continued proliferation (61). However, during mitosis, the nuclear envelope must disintegrate in order to permit the segregation of the condensed chromosomes. While cells are in interphase, chromatin is bound to the nuclear envelope to maintain each chromosome in its defined region of the nucleus. In preparation for the breakdown of the nuclear envelope during mitosis, ANKLE2 phosphorylates envelope components to reduce the binding affinity between chromatin and the nuclear envelope (128). Once this interaction is broken, the nuclear envelope can begin to disassemble; upon mitotic exit, ANKLE2 dephosphorylates components so the nuclear envelope can reform and reestablish its interaction with the chromatin within the nucleus (128).

Signaling

The decision for a cell to progress through the cell cycle and divide relies upon numerous signals. For a cell to enter S phase, the cell must assess DNA integrity, metabolic state, and developmental cues—providing these all satisfy certain thresholds, the cell may progress through the cell cycle, which is itself regulated by a series of checkpoints that require the cyclic activity of positive regulators [cyclins and cyclin-dependent kinases (CDKs)] and negative regulators (examples include p53, p21, and retinoblastoma protein). Here, we discuss MCPH genes that influence signaling pathways, such as those involved in cell cycle checkpoints, metabolism, and Wnt signaling.

Cell Cycle Regulators

One MCPH gene, CDK6, directly regulates the cell cycle; it is responsible for the progression of the cell through G1 phase and the G1/S phase transition (62, 129). In addition, there are two MCPH genes, COPB2 and MFSD2A, that more indirectly affect the cell cycle (66, 130, 131). The first, COPB2, is typically associated with trafficking between the Golgi apparatus and the endoplasmic reticulum, but it has recently been shown to regulate several cell cycle proteins (132). Knockdown of COPB2 increases the expression of CDK inhibitors (P16 and P21) and decreases the expression of cyclin A1 and A2, which are responsible for progression through S phase. MFSD2A encodes a fatty acid transporter that acts at the blood–brain barrier (133, 134). It is responsible for the uptake of lysophosphatidylcholines (LPCs), such as those derived from docosahexanoic acid (DHA), which are not synthesized within the brain but are essential for neurogenesis. Specifically, in the early stages of neural stem cell differentiation, DHA promotes cell cycle exit and subsequent differentiation by decreasing the expression of several key cyclins, thus preventing the transition from G1 to S phase (130, 131).

Metabolism

MFSDA2 also performs a metabolic role. DHA is a major component of the brain lipid profile as it comprises many of the phospholipids within the brain. Mutations in MFSD2A result in increased plasma levels of LPCs and a corresponding decrease in LPC uptake into the brain; this reduced uptake is associated with both lethal and non-lethal microcephaly in humans and animal models (63, 64, 133, 135). The presence of DHA in the brain suppresses the activity of master transcriptional regulators of sterol and fatty acid synthesis (133). Accordingly, reduced uptake of DHA due to mutations in MFSD2A results in the increased expression of the master transcriptional regulators and their downstream targets. This indicates that the lipid metabolic pathways must be tightly regulated during neurogenesis, and is highlighted by the link between DHA levels within the brain and proliferation (136).

Wnt Signaling

Canonical Wnt signaling activation, at its core, involves the binding of a Wnt-protein ligand to a Frizzled family receptor, which in turn activates the intracellular messenger protein, Disheveled, to influence gene transcription via β-catenin accumulation. Canonical Wnt signaling promotes proliferative cell divisions (i.e., the production of progenitor cells), whereas its loss leads to neuronal differentiation (137–140). ASPM appears to act as a positive regulator of Wnt signaling by preventing the proteasome-mediated degradation of Disheveled (141–143). Conversely, WDFY3 attenuates Wnt signaling; it is responsible for degrading Disheveled aggregates, thus reducing β-catenin levels (65).

Facilitating Primary Microcephaly Diagnosis

As summarized, MCPH genes are involved in a number of cellular processes, such as centriole biogenesis, mitotic spindle formation, transcription, DNA damage responses, and signaling. Obviously, screening for the 25 known genes in MCPH patients via gene panels or directed sequencing is the simplest method of diagnosing patients and is likely to be successful in about 50% of patients, as previously found (144). However, with advances in WGS, how do we address the remaining 50% of patients? In this section of the review, we discuss a range of aspects to consider when prioritizing variants in patients.

Linking Cell Biology to Disease

A thorough understanding of the etiology of a disease can guide the diagnostic process. Thus far, we have outlined the molecular roles of each of the MCPH genes known to date, and although each of the thus far implicated genes appear to be involved in distinct cellular processes, MCPH mutations commonly affect the cell cycle exit fraction by pre-maturely increasing the ratio of differentiating to proliferating cells or by triggering apoptosis. For instance, incorrectly positioned mitotic spindles promote asymmetric divisions, thereby increasing the cell cycle exit ratio and cell division delays mimic differentiating cells which have exited the cell cycle. We would therefore predict that mutations in functionally related genes would be likely implicated in the disease. In support of this, a FZR1 variant, which encodes a component of the APC/C complex and is responsible for driving the cell cycle, has recently been identified in a patient with MCPH-like phenotypes (145). Similarly, a patient with a mutation in TUBGCP5, which is a centrosomal component that affects microtubule nucleation and spindle orientation, presents with MCPH (146). Finally, a METTL5 variant has also recently been identified in a patient with clinical features matching that of MCPH, highlighting the role of epigenetics and transcriptional regulation in the etiology of MCPH (147). Although these three genes are not listed in OMIM as of August 2020 as MCPH genes, we expect that these will be included following database updates and identification of additional patients with mutations in these genes.

Translation From Genetic Models

One issue when diagnosing patients is that many genes simply do not have a recognized molecular or cellular function ascribed to them. However, the study of these genes in model organisms may reveal a function related to processes disrupted in microcephaly. Not only do most of the MCPH genes have conserved functions across the animal kingdom (Table 1), but mutations in these genes also show a conserved set of phenotypes in model organisms (phenologs); although these phenotypes do not always perfectly mimic the human disease condition, they do reflect perturbation of a common pathway, which gives us a better understanding of whether a given gene is likely to be causal in disease. For instance, modeling MCPH gene mutations in zebrafish, mice, and Drosophila typically results in animals with small heads, whereas in Caenorhabditis elegans, embryonic lethality with abnormal cell division phenotypes is often observed (49, 65, 69, 80, 83, 148–155). In this way, we can not only validate potential candidates but also begin to screen for possible new candidates that may subsequently be found in human patients. Loss of cntrob in zebrafish or Hmgn2 in mice results in microcephaly, although, as of yet, they are not associated with microcephaly in humans (156, 157). Similarly, pioneering work in C. elegans has revealed the importance of SPD-2 (CEP192 in humans) in centriole duplication and PCM maturation, but despite the clear association of other core centriole biogenesis components with microcephaly, CEP192 has not yet been implicated (80, 158). While these genes are not yet associated with MCPH, this may be due to the rarity of these variants in human populations or highly deleterious effects resulting in lethality. Additionally, the phenotypes seen in model organisms may be more profound in the lab environment than they would present in humans, decreasing their chances of being discovered.

Analyzing Inheritance Patterns

Another mechanism of prioritizing variants is to examine the inheritance pattern. With the exception of WDFY3, all MCPH variants are autosomal recessively inherited (Table 1). Many microcephaly patients exhibit homozygous variants in the disease-causing gene due to consanguinity, but increasingly, compound heterozygous variants are being discovered. Therefore, in non-consanguineous families, performing triad sequencing and using filtering methods that include compound heterozygous variants are essential. However, recent evidence suggests that the inheritance of MCPH may be more complicated than originally thought and alternative forms of inheritance should be considered in difficult-to-diagnose patients. For instance, similar to WDFY3, mutations in DPP6, which encodes a dipeptidyl peptidase protein, cause autosomal dominant microcephaly in addition to intellectual disabilities, indicating that it may also be necessary to screen through heterozygous variants in patients (159). Furthermore, there is increasing evidence that MCPH may occasionally follow an oligogenic inheritance pattern; a recent study found that microcephaly patients have a higher mutational burden in genes implicated in causing MCPH (69). Additionally, the digenic inheritance of CDK5RAP2 and CEP152 heterozygous mutations causes Seckel syndrome, a disease which includes microcephaly as a clinical feature (24). Again, turning to genetic models may validate instances where digenic inheritance is predicted to be necessary for phenotypic presentation or where modifying genes affect phenotypic severity. In the fish model, for example, homozygous mutations in both aspm and wdr62 are necessary to produce the microcephaly phenotype (69). Considering that ciliopathies are well-established digenic conditions, and like microcephalies, depend upon proper cell cycle timing and centrosome function (Figure 3), it is not challenging to envision a model in which these diseases genetically parallel each other. Conversely, a mutation in Ttc21b causes genetic background-dependent microcephaly in mouse; quantitative trait locus analysis revealed a missense mutation in one genetic background but not the other that was able to enhance the Ttc21b neural phenotypes (160). Therefore, clinicians may have to look past traditional autosomal recessively inherited variants in a single gene in particularly challenging to diagnose patients.

Determining Mode of Gene Inactivation

Intriguingly, most of the MCPH-causing mutations are non-sense, frameshift, or splicing mutations, all of which typically result in a complete loss-of-function of the protein product (Table 1). However, this also implies that other types of nullifying mutations, such as structural variants, copy number variants (CNVs), or non-coding regulatory variants, may be causative in microcephaly. Already, larger deletion mutations in MCPH1 and ASPM have been identified in MCPH patients, in addition to a translocation break in ASPM that disrupts the coding sequence (3, 36, 37, 51). However, these types of variations are likely to be increasingly discovered as our methods of identifying these variants improve. Similarly, the use of transcriptomics, such as RNA-seq, may expedite our identification of non-coding variants in patients; the use of transcriptomics in a patient with microcephaly-micromelia syndrome found a non-coding mutation in DONSON that caused aberrant splicing (161). Multimethod approaches to identifying causal mutations may therefore be necessary, in addition to using tools that are capable of detecting a wide range of variants.

Evolution of Brain Size in Primates

One of the hallmarks of human evolution is an increase in brain size and complexity, a change that was accompanied by increased cognitive power. Interestingly, there is a correlation between genes predicted to be responsible for driving the increase in human brain size and those that are implicated in causing MCPH. For instance, MCPH1, CDK5RAP2, CENPJ, and ASPM have been shown to have undergone positive selection during primate evolution (162–165). Researchers speculate that over the course of evolution, MCPH genes may have accumulated genetic changes that permitted the increase in hominid brain size—specifically, these changes likely altered the rate of cell division in proliferating neuronal stem cells. Conversely, the disease state may be an example of atavism, in which nullifying mutations recreate a more ancestral state. Another possibility is the changes in copy number may underlie hominid brain size changes; a recently discovered example is NOTCH2NL, in which three copies are necessary for normal human development (166). The duplication or deletion of the locus in which NOTCH2NL is located results in macrocephaly or microcephaly, respectively. Therefore, evolutionary analyses, such as those determining whether a gene undergoes positive selection through the course of hominid brain evolution, may be one more mechanism by which microcephaly-causing variants are prioritized [reviewed in Gilbert et al. (166)].

Remaining Questions

Why do mutations in MCPH genes specifically affect neurogenesis? While some MCPH genes have enriched expression in neural progenitors or have a biological function limited to the brain (e.g., MFSD2A), many genes are ubiquitously expressed and have biological functions that are necessary in many tissue types (18, 134). Therefore, a major question is why mutations in the MCPH genes, which are typically nullifying mutations, specifically cause microcephaly, with generally few abnormalities outside of the head and brain. This is especially true when we consider that in the C. elegans model, mutations in orthologous MCPH genes result in lethality, which would be predicted based on the essential function of these genes in cell division. One similarity between neuroprogenitors and C. elegans development though is that the cell cycle length is remarkably short; in humans, the length is shorter in comparison to other cell types, and in C. elegans, the first few cell divisions occur extremely rapidly and are stereotypically oriented (167, 168). In fact, G1 length has been shown to be an essential regulator of the switch between proliferation and differentiation, which explains why mutations in MCPH genes, which generally cause a lengthening in the cell cycle and thus pre-maturely increase the cell cycle exit fraction, have dramatic effects on the number of progenitors remaining in a proliferative state (129, 169). The brain therefore appears to be more sensitive to changes in cell cycle length relative to other tissue types, an effect that may be appropriately modeled using the C. elegans genetic system.

Another possibility may lie in alternative splicing. The brain undergoes the most alternative splicing events than any other tissue and expresses the largest number of splicing factor genes (170). This means that the brain produces more diverse protein isoforms than other tissue types. Accordingly, there are many examples of splicing mutations in MCPH genes (Table 1); it is possible that the disruption in splicing in these genes affects the protein isoforms that are uniquely expressed in the brain. For instance, a splicing mutation in KNL1 specifically affects neuronal progenitor cells, but fibroblasts and neural crest cells expressing the same mutation are unaffected (171). Although not every MCPH mutation affects splicing, this may be one mechanism that contributes to the brain-specific presentation.

Finally, the classical clinical definition of MCPH describes an isolated disorder affecting the head and brain size, with typically no other malformations. However, as more patients continue to be discovered and diagnosed with MCPH, the clinical landscape of primary microcephaly expands. We now know that in addition to a small head, MCPH is frequently associated with cortical and facial malformations, intellectual disabilities, and seizures, in addition to short stature, heart problems, and in extreme cases, pre-mature death (Table 1). Many of the genes are also implicated in causing different but related diseases, such as Seckel syndrome or microcephalic primordial dwarfism, indicating that there is likely an overlapping pathophysiology between these conditions, and they may represent a disease spectrum rather than individual conditions. In support of this, many genes that are implicated in causing syndromic microcephaly affect the same pathways as MCPH genes, indicating that cell cycle dysregulation underlies both isolated and syndromic microcephalies. This reflects the prediction that mutations in genes affecting cell cycle progression would present with more pleiotropic effects.

Concluding Remarks

MCPH is a heterogeneous disorder that, like many rare diseases, has been challenging to diagnose despite advances in genomics. Therefore, there is a need to understand the genetics and cell biology underlying the disease in order to expedite discovery and genetic diagnosis. This review has shown that microcephaly is caused by aberrant cell cycle regulation by summarizing the molecular functions of each of the known MCPH-causing genes and their associated cellular phenotypes, as well as providing examples of novel MCPH candidates. In addition to furthering our understanding of the disease pathogenesis, we have also provided insights on the genetics and inheritance of MCPH with the hopes of facilitating the variant prioritization process in patients with microcephaly. Altogether, the incorporation of each of these disease facets in the process of identifying the MCPH-causing gene(s) will improve diagnosis rates in these patients and will guide family planning and personalized treatments but also forms a template for the inclusion of multidisciplinary approaches in the diagnostic process.

Author Contributions

FJ and MT-G: conceptualization and funding acquisition. FJ and AS: writing—original draft preparation. MT-G: writing—review and editing and supervision. All authors have read and agreed to the final manuscript version.

Funding

The authors were funded by the Canadian Institute of Health Research (CIHR-Project grant number: PJT-156068) and an Eyes High Postdoctoral Fellowship.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors thanked Matthew Oldach, Dr. Xiao Li, Andrew Galbraith, Dr. Simona Frederiksen, Tahsin Hassan, Brittany Ngo, and Vladimir Avramovic for their thoughtful insights on manuscript revisions.

References

1. Cox J, Jackson AP, Bond J, Woods CG. What primary microcephaly can tell us about brain growth. Trends Mol Med. (2006) 12:358–66. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2006.06.006

2. Van Den Bosch J. Microcephaly in the Netherlands: a clinical and genetical study. Ann Hum Genet. (1959) 23:91–116. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-1809.1958.tb01455.x

3. Garshasbi M, Motazacker MM, Kahrizi K, Behjati F, Abedini SS, Nieh SE, et al. SNP array-based homozygosity mapping reveals MCPH1 deletion in family with autosomal recessive mental retardation and mild microcephaly. Hum Genet. (2006) 118:708–15. doi: 10.1007/s00439-005-0104-y

4. Gul A, Hassan MJ, Hussain S, Raza SI, Chishti MS, Ahmad W. A novel deletion mutation in CENPJ gene in a Pakistani family with autosomal recessive primary microcephaly. J Hum Genet. (2006) 51:760–4. doi: 10.1007/s10038-006-0017-1

5. Sajid Hussain M, Marriam Bakhtiar S, Farooq M, Anjum I, Janzen E, Reza Toliat M, et al. Genetic heterogeneity in Pakistani microcephaly families. Clin Genet. (2013) 83:446–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2012.01932.x

6. Bond J, Roberts E, Springell K, Lizarraga S, Scott S, Higgins J, et al. A centrosomal mechanism involving CDK5RAP2 and CENPJ controls brain size. Nat Genet. (2005) 37:353–5. doi: 10.1038/ng1539

7. Al-Dosari MS, Shaheen R, Colak D, Alkuraya FS. Novel CENPJ mutation causes Seckel syndrome. J Med Genet. (2010) 47:411–4. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2009.076646

8. Kumar A, Girimaji SC, Duvvari MR, Blanton SH. Mutations in STIL, encoding a pericentriolar and centrosomal protein, cause primary microcephaly. Am J Hum Genet. (2008) 84:286–90. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2009.01.017

9. Papari E, Bastami M, Farhadi A, Abedini S, Hosseini M, Bahman I, et al. Investigation of primary microcephaly in Bushehr province of Iran: novel STIL and ASPM mutations. Clin Genet. (2013) 83:488–90. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2012.01949.x

10. Kakar N, Ahmad J, Morris-Rosendahl DJ, Altmüller J, Friedrich K, Barbi G, et al. STIL mutation causes autosomal recessive microcephalic lobar holoprosencephaly. Hum Genet. (2014) 134:45–51. doi: 10.1007/s00439-014-1487-4

11. Cristofoli F, De Keersmaecker B, De Catte L, Vermeesch JR, Van Esch H. Novel STIL compound heterozygous mutations cause severe fetal microcephaly and centriolar lengthening. Mol Syndromol. (2017) 8:282–93. doi: 10.1159/000479666

12. Farooq M, Fatima A, Mang Y, Hansen L, Kjaer KW, Baig SM, et al. A novel splice site mutation in CEP135 is associated with primary microcephaly in a Pakistani family. J Hum Genet. (2016) 61:271–3. doi: 10.1038/jhg.2015.138

13. Hussain MS, Baig SM, Neumann S, Nürnberg G, Farooq M, Ahmad I, et al. A truncating mutation of CEP135 causes primary microcephaly and disturbed centrosomal function. Am J Hum Genet. (2012) 90:871–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2012.03.016

14. Kalay E, Yigit G, Aslan Y, Brown KE, Pohl E, Bicknell LS, et al. CEP152 is a genome maintenance protein disrupted in Seckel syndrome. Nat Genet. (2011) 43:23–6. doi: 10.1038/ng.725

15. Guernsey DL, Jiang H, Hussin J, Arnold M, Bouyakdan K, Perry S, et al. Mutations in centrosomal protein CEP152 in primary microcephaly families linked to MCPH4. Am J Hum Genet. (2010) 87:40–51. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2010.06.003

16. Khan MA, Rupp VM, Orpinell M, Hussain MS, Altmüller J, Steinmetz MO, et al. A missense mutation in the PISA domain of HsSAS-6 causes autosomal recessive primary microcephaly in a large consanguineous Pakistani family. Hum Mol Genet. (2014) 23:5940–9. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddu318

17. Yi YG, Lee D-W, Kim J, Jang J-H, Lee S-M, Jang D-H. Two novel mutations (c.883-4_890del and c.1684C>G) of WDR62 gene associated with autosomal recessive primary microcephaly: a case report. Front Pediatr. (2019) 7:457. doi: 10.3389/fped.2019.00457

18. Rakic P. A small step for the cell, a giant leap for mankind: a hypothesis of neocortical expansion during evolution. Trends Neurosci. (1995) 18:383–8. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(95)93934-P

19. Nicholas AK, Khurshid M, Désir J, Carvalho OP, Cox JJ, Thornton G, et al. WDR62 is associated with the spindle pole and is mutated in human microcephaly. Nat Genet. (2010) 42:1010–4. doi: 10.1038/ng.682

20. Yu TW, Mochida GH, Tischfield DJ, Sgaier SK, Flores-Sarnat L, Sergi CM, et al. Mutations in WDR62, encoding a centrosome-associated protein, cause microcephaly with simplified gyri and abnormal cortical architecture Human Splicing Finder Version 2.3 HHS Public Access Author manuscript. Nat Genet. (2010) 42:1015–20. doi: 10.1038/ng.683

21. Murdock DR, Clark GD, Bainbridge MN, Newsham I, Wu Y-Q, Muzny DM, et al. Whole-exome sequencing identifies compound heterozygous mutations in WDR62 in siblings with recurrent polymicrogyria. Am J Med Genet Part A. (2011) 155:2071–7. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.34165

22. Bhat V, Girimaji S, Mohan G, Arvinda H, Singhmar P, Duvvari M, et al. Mutations in WDR62, encoding a centrosomal and nuclear protein, in Indian primary microcephaly families with cortical malformations. Clin Genet. (2011) 80:532–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2011.01686.x

23. Jouan L, Bencheikh BOA, Daoud H, Dionne-Laporte A, Dobrzeniecka S, Spiegelman D, et al. Exome sequencing identifies recessive CDK5RAP2 variants in patients with isolated agenesis of corpus callosum. Eur J Hum Genet. (2016) 24:607–10. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2015.156

24. Snedeker J, Gibbons WJ, Paulding DF, Abdelhamed Z, Prows DR, Stottmann RW. Gpr63 is a modifier of microcephaly in Ttc21b mouse mutants. PLoS Genet. (2019) 15:e1008467. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1008467

25. Pagnamenta AT, Murray JE, Yoon G, Akha ES, Harrison V, Bicknell LS, et al. A novel nonsense CDK5RAP2 mutation in a Somali child with primary microcephaly and sensorineural hearing loss. Am J Med Genet Part A. (2012) 158:2577–82. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.35558

26. Lancaster MA, Renner M, Martin CA, Wenzel D, Bicknell LS, Hurles ME, et al. Cerebral organoids model human brain development and microcephaly. Nature. (2013) 501:373–9. doi: 10.1038/nature12517

27. Tan CA, Topper S, Ward Melver C, Stein J, Reeder A, Arndt K, et al. The first case of CDK5RAP2-related primary microcephaly in a non-consanguineous patient identified by next generation sequencing. Brain Dev. (2014) 36:351–5. doi: 10.1016/j.braindev.2013.05.001

28. Pagnamenta AT, Howard MF, Knight SJL, Keays DA, Quaghebeur G, Taylor JC, et al. Activation of an exonic splice-donor site in exon 30 of CDK5RAP2 in a patient with severe microcephaly and pigmentary abnormalities. Clin Case Reports. (2016) 4:952–6. doi: 10.1002/ccr3.663

29. Moynihan L, Jackson AP, Roberts E, Karbani G, Lewis I, Corry P, et al. A third novel locus for primary autosomal recessive microcephaly maps to chromosome 9q34. Am J Hum Genet. (2000) 66:724–7. doi: 10.1086/302777

30. Heney D, Mueller R, Turner G, Karbani G, Cadranel J, Lewis IJ, et al. Familial microcephaly with normal intelligence in a patient with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Cancer. (1992) 69:962–5. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19920215)69:4<962::AID-CNCR2820690421>3.0.CO;2-W

31. Zarate YA, Kaylor JA, Bosanko K, Lau S, Vargas J, Gao H. First clinical report of an infant with microcephaly and CASC5 mutations. Am J Med Genet Part A. (2016) 170:2215–8. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.37726

32. Genin A, Desir J, Lambert N, Biervliet M, Van Der Aa N, Pierquin G, et al. Kinetochore KMN network gene CASC5 mutated in primary microcephaly. Hum Mol Genet. (2012) 21:5306–17. doi: 10.1093/hmg/dds386

33. Saadi A, Verny F, Siquier-Pernet K, Bole-Feysot C, Nitschke P, Munnich A, et al. Refining the phenotype associated with CASC5 mutation. Neurogenetics. (2016) 17:71–8. doi: 10.1007/s10048-015-0468-7

34. Jamieson CR, Govaerts C, Abramowicz MJ. Primary autosomal recessive microcephaly: homozygosity mapping of MCPH4 to chromosome 15. Am J Hum Genet. (1999) 65:1465–9. doi: 10.1086/302640

35. Létard P, Drunat S, Vial Y, Duerinckx S, Ernault A, Amram D, et al. Autosomal recessive primary microcephaly due to ASPM mutations: an update. Hum Mutat. (2018) 39:319–32. doi: 10.1002/humu.23381

36. Pichon B, Vankerckhove S, Bourrouillou G, Duprez L, Abramowicz MJ. A translocation breakpoint disrupts the ASPM gene in a patient with primary microcephaly. Eur J Hum Genet. (2004) 12:419–21. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201169

37. Evrony GD, Cordero DR, Shen J, Partlow JN, Yu TW, Rodin RE, et al. Integrated genome and transcriptome sequencing identifies a noncoding mutation in the genome replication factor DONSON as the cause of microcephaly-micromelia syndrome. Genome Res. (2017) 27:1323–35. doi: 10.1101/gr.219899.116

38. Bond J, Scott S, Hampshire DJ, Springell K, Corry P, Abramowicz MJ, et al. Protein-truncating mutations in ASPM cause variable reduction in brain size. Am J Hum Genet. (2003) 73:1170–7. doi: 10.1086/379085

39. Shen J, Eyaid W, Mochida GH, Al-Moayyad F, Bodell A, Woods CG. ASPM mutations identified in patients with primary microcephaly and seizures. J Med Genet. (2005) 42:725–9. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2004.027706

40. Mirzaa GM, Vitre B, Carpenter G, Abramowicz I, Gleeson JG, Paciorkowski AR, et al. Mutations in CENPE define a novel kinetochore-centromeric mechanism for microcephalic primordial dwarfism. Hum Genet. (2014) 133:1023–39. doi: 10.1007/s00439-014-1443-3

41. Harding BN, Moccia A, Drunat S, Soukarieh O, Ne Tubeuf H, Chitty LS, et al. Mutations in citron kinase cause recessive microlissencephaly with multinucleated neurons. Am J Hum Genet. (2016) 99:511–20. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2016.07.003

42. Basit S, Al-Harbi KM, Alhijji SAM, Albalawi AM, Alharby E, Eldardear A, et al. CIT, a gene involved in neurogenic cytokinesis, is mutated in human primary microcephaly. Hum Genet. (2016) 135:1199–207. doi: 10.1007/s00439-016-1724-0

43. Li H, Bielas SL, Zaki MS, Ismail S, Farfara D, Um K, et al. Biallelic mutations in citron kinase link mitotic cytokinesis to human primary microcephaly. Am J Hum Genet. (2016) 99:501–10. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2016.07.004

44. Shaheen R, Hashem A, Abdel-Salam GMH, Al-Fadhli F, Ewida N, Fowzan SA. Mutations in CIT, encoding citron rho-interacting serine/ threonine kinase, cause severe primary microcephaly in humans. Hum Genet. (2016) 135:1191–7. doi: 10.1007/s00439-016-1722-2

45. Moawia A, Shaheen R, Rasool S, Waseem SS, Ewida N, Budde B, et al. Mutations of KIF14 cause primary microcephaly by impairing cytokinesis. Ann Neurol. (2017) 82:562–77. doi: 10.1002/ana.25044

46. Makrythanasis P, Maroofian R, Stray-Pedersen A, Musaev D, Zki MS, Mahmoud IG, et al. Biallelic variants in KIF14 cause intellectual disability with microcephaly. Eur J Hum Genet. (2018) 26:330–9. doi: 10.1038/s41431-017-0088-9

47. Filges I, Nosova E, Bruder E, Tercanli S, Townsend K, Gibson WT, et al. Exome sequencing identifies mutations in KIF14 as a novel cause of an autosomal recessive lethal fetal ciliopathy phenotype. Clin Genet. (2014) 86:220–8. doi: 10.1111/cge.12301

48. Farooq M, Baig S, Tommerup N, Kjaer KW. Craniosynostosis-microcephaly with chromosomal breakage and other abnormalities is caused by a truncating MCPH1 mutation and is allelic to premature chromosomal condensation syndrome and primary autosomal recessive microcephaly type 1. Am J Med Genet Part A. (2010) 152:495–7. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.33234

49. Perez Y, Bar-Yaacov R, Kadir R, Wormser O, Shelef I, Birk OS, et al. Mutations in the microtubule-associated protein MAP11 (C7orf43) cause microcephaly in humans and zebrafish. Brain. (2019) 142:574–85. doi: 10.1093/brain/awz004

50. Trimborn M, Bell SM, Felix C, Rashid Y, Jafri H, Griffiths PD, et al. Mutations in microcephalin cause aberrant regulation of chromosome condensation. Am J Hum Genet. (2004) 75:261–6. doi: 10.1086/422855

51. Nicholas AK, Swanson EA, Cox JJ, Karbani G, Malik S, Springell K, et al. The molecular landscape of ASPM mutations in primary microcephaly. J Med Genet. (2009) 46:249–53. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2008.062380

52. Jackson AP, Eastwood H, Bell SM, Adu J, Toomes C, Carr IM, et al. Identification of microcephalin, a protein implicated in determining the size of the human brain. Am J Hum Genet. (2002) 71:136–42. doi: 10.1086/341283

53. Neitzel H, Neumann LM, Schindler D, Wirges A, Tönnies H, Trimborn M, et al. Premature chromosome condensation in humans associated with microcephaly and mental retardation: a novel autosomal recessive condition. Am J Hum Genet. (2002) 70:1015–22. doi: 10.1086/339518

54. Sato R, Takanashi JI, Tsuyusaki Y, Kato M, Saitsu H, Matsumoto N, et al. Association between invisible Basal Ganglia and ZNF335 mutations: a case report. Pediatrics. (2016) 138:e20160897. doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-0897

55. Yang YJ, Baltus AE, Mathew RS, Murphy EA, Evrony GD, Gonzalez DM, et al. Microcephaly gene links trithorax and REST/NRSF to control neural stem cell proliferation and differentiation. Cell. (2012) 151:1097–112. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.10.043

56. Stouffs K, Stergachis AB, Vanderhasselt T, Dica A, Janssens S, Vandervore L, et al. Expanding the clinical spectrum of biallelic ZNF335 variants. Clin Genet. (2018) 94:246–51. doi: 10.1111/cge.13260

57. Yamamoto S, Jaiswal M, Charng WL, Gambin T, Karaca E, Mirzaa G, et al. A drosophila genetic resource of mutants to study mechanisms underlying human genetic diseases. Cell. (2014) 159:200–14. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.09.002

58. Awad S, Al-Dosari MS, Al-Yacoub N, Colak D, Salih MA, Alkuraya FS, et al. Mutation in PHC1 implicates chromatin remodeling in primary microcephaly pathogenesis. Hum Mol Genet. (2013) 22:2200–13. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddt072

59. Reuter MS, Tawamie H, Buchert R, Gebril OH, Froukh T, Thiel C, et al. Diagnostic yield and novel candidate genes by exome sequencing in 152 consanguineous families with neurodevelopmental disorders. JAMA Psychiatry. (2017) 74:293–9. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2016.3798

60. Martin CA, Murray JE, Carroll P, Leitch A, Mackenzie KJ, Halachev M, et al. Mutations in genes encoding condensin complex proteins cause microcephaly through decatenation failure at mitosis. Genes Dev. (2016) 30:2158–72. doi: 10.1101/gad.286351.116

61. Braun DA, Lovric S, Schapiro D, Schneider R, Marquez J, Asif M, et al. Mutations in multiple components of the nuclear pore complex cause nephrotic syndrome. J Clin Invest. (2018) 128:4313–28. doi: 10.1172/JCI98688

62. Hussain MS, Baig SM, Neumann S, Peche VS, Szczepanski S, Nürnberg G, et al. CDK6 associates with the centrosome during mitosis and is mutated in a large pakistani family with primary microcephaly. Hum Mol Genet. (2013) 22:5199–214. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddt374

63. Alakbarzade V, Hameed A, Quek DQY, Chioza BA, Baple EL, Cazenave-Gassiot A, et al. A partially inactivating mutation in the sodium-dependent lysophosphatidylcholine transporter MFSD2A causes a non-lethal microcephaly syndrome. Nat Genet. (2015) 47:814–7. doi: 10.1038/ng.3313

64. Guemez-Gamboa A, Nguyen LN, Yang H, Zaki MS, Kara M, Ben-Omran T, et al. Inactivating mutations in MFSD2A, required for omega-3 fatty acid transport in brain, cause a lethal microcephaly syndrome. Nat Genet. (2015) 47:809–13. doi: 10.1038/ng.3311

65. Kadir R, Harel T, Markus B, Perez Y, Bakhrat A, Cohen I, et al. ALFY-Controlled DVL3 autophagy regulates wnt signaling, determining human brain size. PLoS Genet. (2016) 12:e1005919. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1005919

66. DiStasio A, Driver A, Sund K, Donlin M, Muraleedharan RM, Pooya S, et al. Copb2 is essential for embryogenesis and hypomorphic mutations cause human microcephaly. Hum Mol Genet. (2017) 26:4836–48. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddx362

67. Picher-Martel V, Labrie Y, Rivest S, Lace B, Chrestian N. Whole-exome sequencing identifies homozygous mutation in TTI2 in a child with primary microcephaly: a case report. BMC Neurol. (2020) 20:58. doi: 10.1186/s12883-020-01643-1

68. Rump P, Jazayeri O, van Dijk-Bos KK, Johansson LF, van Essen AJ, Verheij JBGM, et al. Whole-exome sequencing is a powerful approach for establishing the etiological diagnosis in patients with intellectual disability and microcephaly. BMC Med Genomics. (2015) 9:7. doi: 10.1186/s12920-016-0167-8

69. Duerinckx S, Jacquemin V, Drunat S, Vial Y, Passemard S, Perazzolo C, et al. Digenic inheritance of human primary microcephaly delineates centrosomal and non centrosomal pathways. Hum Mutat. (2019) 41:512–24. doi: 10.1002/humu.23948

70. Noctor SC, Martinez-Cerdeno V, Ivic L, Kriegstein AR. Cortical neurons arise in symmetric and asymmetric division zones and migrate through specific phases. Nat Neurosci. (2004) 7:136–44. doi: 10.1038/nn1172

71. Chenn A, McConnell SK. Cleavage orientation and the asymmetric inheritance of Notch1 immunoreactivity in mammalian neurogenesis. Cell. (1995) 82:631–41. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90035-7

72. Noctor SC, Flint AC, Weissman TA, Wong WS, Clinton BK, Kriegstein AR. Dividing precursor cells of the embryonic cortical ventricular zone have morphological and molecular characteristics of radial glia. J Neurosci. (2002) 22:3161–73. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-08-03161.2002

73. Takahashi T, Nowakowski RS, Caviness VSJ. The leaving or Q fraction of the murine cerebral proliferative epithelium: a general model of neocortical neuronogenesis. J Neurosci. (1996) 16:6183–96. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-19-06183.1996

74. Pucci B, Kasten M, Giordano A. Cell cycle and apoptosis. Neoplasia. (2000) 2:291–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.neo.7900101

75. Sir J-H, Barr AR, Nicholas AK, Carvalho OP, Khurshid M, Sossick A, et al. A primary microcephaly protein complex forms a ring around parental centrioles. Nat Genet. (2011) 43:1147–53. doi: 10.1038/ng.971

76. Kim T-S, Park J-E, Shukla A, Choi S, Murugan RN, Lee JH, et al. Hierarchical recruitment of Plk4 and regulation of centriole biogenesis by two centrosomal scaffolds, Cep192 and Cep152. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. (2013) 110:4849–57. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1319656110

77. Sonnen KF, Gabryjonczyk AM, Anselm E, Nigg EA, Stierhof YD. Human cep192 and cep152 cooperate in plk4 recruitment and centriole duplication. J Cell Sci. (2013) 126:3223–33. doi: 10.1242/jcs.129502

78. Tsuchiya Y, Yoshiba S, Gupta A, Watanabe K, Kitagawa D. Cep295 is a conserved scaffold protein required for generation of a bona fide mother centriole. Nat Commun. (2016) 7:12567. doi: 10.1038/ncomms12567

79. Jayaraman D, Kodani A, Gonzalez DM, Mancias JD, Mochida GH, Vagnoni C, et al. Microcephaly proteins Wdr62 and Aspm define a mother centriole complex regulating centriole biogenesis, apical complex, and cell fate. Neuron. (2016) 92:813–28. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2016.09.056

80. Pelletier L, O'Toole E, Schwager A, Hyman AA, Müller-Reichert T. Centriole assembly in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature. (2006) 444:619–23. doi: 10.1038/nature05318

81. Keller D, Orpinell M, Olivier N, Wachsmuth M, Mahen R, Wyss R, et al. Mechanisms of HsSAS-6 assembly promoting centriole formation in human cells. J Cell Biol. (2014) 204:697–712. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201307049

82. Rogala KB, Dynes NJ, Hatzopoulos GN, Yan J, Pong SK, Robinson CV, et al. The Caenorhabditis elegans protein SAS-5 forms large oligomeric assemblies critical for centriole formation. Elife. (2015) 4:1–51. doi: 10.7554/eLife.07410

83. Delattre M, Canard C, Gönczy P. Sequential protein recruitment in C. elegans centriole formation. Curr Biol. (2006) 16:1844–9. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.07.059

84. Singla V, Romaguera-Ros M, Garcia-Verdugo JM, Reiter JF. Ofd1, a human disease gene, regulates the length and distal structure of centrioles. Dev Cell. (2010) 18:410–24. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.12.022

85. Azimzadeh J, Hergert P, Delouvée A, Euteneuer U, Formstecher E, Khodjakov A, et al. hPOC5 is a centrin-binding protein required for assembly of full-length centrioles. J Cell Biol. (2009) 185:101–14. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200808082

86. Schmidt TI, Kleylein-Sohn J, Westendorf J, Le Clech M, Lavoie SB, Stierhof Y-D, et al. Control of centriole length by CPAP and CP110. Curr Biol. (2009) 19:1005–11. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2009.05.016

87. Lin YC, Chang CW, Hsu WB, Tang CJC, Lin YN, Chou EJ, et al. Human microcephaly protein CEP135 binds to hSAS-6 and CPAP, and is required for centriole assembly. EMBO J. (2013) 32:1141–4. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2013.56

88. Dictenberg JB, Zimmerman W, Sparks CA, Young A, Vidair C, Zheng Y, et al. Pericentrin and gamma-tubulin form a protein complex and are organized into a novel lattice at the centrosome. J Cell Biol. (1998) 141:163–74. doi: 10.1083/jcb.141.1.163

89. Hamill DR, Severson AF, Carter JC, Bowerman B. Centrosome maturation and mitotic spindle assembly in C. elegans require SPD-5, a protein with multiple coiled-coil domains. Dev Cell. (2002) 3:673–84. doi: 10.1016/S1534-5807(02)00327-1

90. Haren L, Stearns T, Lüders J. Plk1-dependent recruitment of gamma-tubulin complexes to mitotic centrosomes involves multiple PCM components. PLoS ONE. (2009) 4:e5976. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005976

91. Doxsey SJ, Stein P, Evans L, Calarco PD, Kirschner M. Pericentrin, a highly conserved centrosome protein involved in microtubule organization. Cell. (1994) 76:639–50. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90504-5

92. Zheng Y, Wong ML, Alberts B, Mitchison T. Nucleation of microtubule assembly by a γ-tubulin-containing ring complex. Nature. (1995) 378:578–83. doi: 10.1038/378578a0

93. Miyamoto T, Akutsu SN, Fukumitsu A, Morino H, Masatsuna Y, Hosoba K, et al. PLK1-mediated phosphorylation of WDR62/MCPH2 ensures proper mitotic spindle orientation. Hum Mol Genet. (2017) 26:4429–40. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddx330

94. Seo MY, Jang W, Rhee K. Integrity of the pericentriolar material is essential for maintaining centriole association during m phase. PLoS ONE. (2015) 10:e138905. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0138905

95. Cabral G, Sans SS, Cowan CR, Dammermann A. Multiple mechanisms contribute to centriole separation in C. elegans. Curr Biol. (2013) 23:1380–7. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2013.06.043

96. Schlaitz A-L, Srayko M, Dammermann A, Quintin S, Wielsch N, MacLeod I, et al. The C. elegans RSA complex localizes protein phosphatase 2A to centrosomes and regulates mitotic spindle assembly. Cell. (2007) 128:115–27. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.10.050

97. Enos SJ, Dressler M, Gomes BF, Hyman AA, Woodruff JB. Phosphatase PP2A and microtubule-mediated pulling forces disassemble centrosomes during mitotic exit. Biol Open. (2018) 7:bio029777. doi: 10.1101/182618

98. Tsou MFB, Stearns T. Mechanism limiting centrosome duplication to once per cell cycle. Nature. (2006) 442:947–51. doi: 10.1038/nature04985

99. Fong K-W, Choi Y-K, Rattner JB, Qi RZ. CDK5RAP2 is a pericentriolar protein that functions in centrosomal attachment of the gamma-tubulin ring complex. Mol Biol Cell. (2008) 19:115–25. doi: 10.1091/mbc.e07-04-0371

100. Barrera JA, Kao LR, Hammer RE, Seemann J, Fuchs JL, Megraw TL. CDK5RAP2 regulates centriole engagement and cohesion in mice. Dev Cell. (2010) 18:913–26. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2010.05.017

101. Paramasivam M, Yoon JC, LoTurco JJ. ASPM and citron kinase co-localize to the midbody ring during cytokinesis. Cell Cycle. (2007) 6:1605–12. doi: 10.4161/cc.6.13.4356

102. Gruneberg U, Neef R, Li X, Chan EHY, Chalamalasetty RB, Nigg EA, et al. KIF14 and citron kinase act together to promote efficient cytokinesis. J Cell Biol. (2006) 172:363–72. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200511061

103. Bassi ZI, Audusseau M, Riparbelli MG, Callaini G, D'Avino PP. Citron kinase controls a molecular network required for midbody formation in cytokinesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. (2013) 110:9782–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1301328110

104. Arora K, Talje L, Asenjo AB, Andersen P, Atchia K, Joshi M, et al. KIF14 binds tightly to microtubules and adopts a rigor-like conformation. J Mol Biol. (2014) 426:2997–3015. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2014.05.030

105. D'Avino PP, Savoian MS, Glover DM. Mutations in sticky lead to defective organization of the contractile ring during cytokinesis and are enhanced by Rho and suppressed by Rac. J Cell Biol. (2004) 166:61–71. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200402157

106. Waddle JA, Cooper JA, Waterston RH. Transient localized accumulation of actin in Caenorhabditis elegans blastomeres with oriented asymmetric divisions. Development. (1994) 120:2317–28.

107. Nguyen-Ngoc T, Afshar K, Gönczy P. Coupling of cortical dynein and Gα proteins mediates spindle positioning in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nat Cell Biol. (2007) 9:1294–302. doi: 10.1038/ncb1649

108. Busson S, Dujardin D, Moreau A, Dompierre J, De Mey JR. Dynein and dynactin are localized to astral microtubules and at cortical sites in mitotic epithelial cells. Curr Biol. (1998) 8:541–4. doi: 10.1016/S0960-9822(98)70208-8

109. van der Voet M, Berends CWH, Perreault A, Nguyen-Ngoc T, Gönczy P, Vidal M, et al. NuMA-related LIN-5, ASPM-1, calmodulin and dynein promote meiotic spindle rotation independently of cortical LIN-5/GPR/Gα. Nat Cell Biol. (2009) 11:269–77. doi: 10.1038/ncb1834

110. Haren L, Gnadt N, Wright M, Merdes A. NuMA is required for proper spindle assembly and chromosome alignment in prometaphase. BMC Res Notes. (2009) 2:64. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-2-64

111. Okumura M, Natsume T, Kanemaki MT, Kiyomitsu T. Dynein–dynactin–NuMA clusters generate cortical spindle-pulling forces as a multiarm ensemble. Elife. (2018) 7:e36559. doi: 10.7554/eLife.36559

112. Lorson MA, Horvitz HR, Van Den Heuvel S. LIN-5 is a novel component of the spindle apparatus required for chromosome segregation and cleavage plane specification in Caenorhabditis elegans. J Cell Biol. (2000) 148:73–86. doi: 10.1083/jcb.148.1.73

113. Yao X, Abrieu A, Zheng Y, Sullivan KF, Cleveland DW. CENP-E forms a link between attachment of spindle microtubules to kinetochores and the mitotic checkpoint. Nat Cell Biol. (2000) 2:484–91. doi: 10.1038/35019518

114. Mao Y, Desai A, Cleveland DW. Microtubule capture by CENP-E silences BubR1-dependent mitotic checkpoint signaling. J Cell Biol. (2005) 170:873–80. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200505040

115. Cheeseman IM, Chappie JS, Wilson-Kubalek EM, Desai A. The conserved KMN network constitutes the core microtubule-binding site of the kinetochore. Cell. (2006) 127:983–97. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.09.039

116. Sudakin V, Chan GKT, Yen TJ. Checkpoint inhibition of the APC/C in HeLa cells is mediated by a complex of BUBR1, BUB3, CDC20, and MAD2. J Cell Biol. (2001) 154:925–36. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200102093

117. Kiyomitsu T, Obuse C, Yanagida M. Human Blinkin/AF15q14 is required for chromosome alignment and the mitotic checkpoint through direct interaction with Bub1 and BubR1. Dev Cell. (2007) 13:663–76. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2007.09.005

118. Bentley Lawrence J, Villnave CA, Singer RH. Sensitive, high-resolution chromatin and chromosome mapping in situ: presence and orientation of two closely integrated copies of EBV in a lymphoma line. Cell. (1988) 52:51–61. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90530-2

119. Li G, Sudlow G, Belmont AS, Li G, Willhelm C, Sudlow G, et al. Interphase cell cycle dynamics of a late-replicating, heterochromatic homogeneously staining region: precise choreography of condensation/decondensation and nuclear positioning. J Cell Biol. (1998) 140:975–89. doi: 10.1083/jcb.140.5.975

120. Green LC, Kalitsis P, Chang TM, Cipetic M, Kim JH, Marshall O, et al. Contrasting roles of condensin I and condensin II in mitotic chromosome formation. J Cell Sci. (2012) 125:1591–604. doi: 10.1242/jcs.097790

121. Yamashita D, Shintomi K, Ono T, Gavvovidis I, Schindler D, Neitzel H, et al. MCPH1 regulates chromosome condensation and shaping as a composite modulator of condensin II. J Cell Biol. (2011) 194:841–54. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201106141

122. Rana V, Bosco G. Condensin regulation of genome architecture. J Cell Physiol. (2017) 232:1617–25. doi: 10.1002/jcp.25702

123. Uhlmann F, Lottspeich F, Nasmyth K. Sister-chromatid separation at anaphase onset is promoted by cleavage of the cohesin subunit Scc1. Nature. (1999) 400:37–42. doi: 10.1038/21831

124. Chaplet M, Rai R, Jackson-Bernitsas D, Li K, Lin SY. BRIT1/MCPH1: a guardian of genome and an enemy of tumors. Cell Cycle. (2006) 5:2579–83. doi: 10.4161/cc.5.22.3471

125. Lin SY, Rai R, Li K, Xu ZX, Elledge SJ. BRIT1/MCPH1 is a DNA damage responsive protein that regulates the Brca1-Chk1 pathway, implicating checkpoint dysfunction in microcephaly. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. (2005) 102:15105–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0507722102

126. Peng G, Yim EK, Dai H, Jackson AP, van der Burgt I, Pan MR, et al. BRIT1/MCPH1 links chromatin remodelling to DNA damage response. Nat Cell Biol. (2009) 11:865–72. doi: 10.1038/ncb1895

127. Holzer G, Antonin W. Breaking the Y. PLoS Genet. (2019) 15:e1008109. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1008109

128. Asencio C, Davidson IF, Santarella-Mellwig R, Ly-Hartig TBN, Mall M, Wallenfang MR, et al. Coordination of kinase and phosphatase activities by Lem4 enables nuclear envelope reassembly during mitosis. Cell. (2012) 150:122–35. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.04.043

129. Beukelaers P, Vandenbosch R, Caron N, Nguyen L, Belachew S, Moonen G, et al. Cdk6-dependent regulation of g1 length controls adult neurogenesis. Stem Cells. (2011) 29:713–24. doi: 10.1002/stem.616

130. Chen ZY, Istfan NW. Docosahexaenoic acid, a major constituent of fish oil diets, prevents activation of cyclin-dependent kinases and S-phase entry by serum stimulation in HT-29 cells. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fat Acids. (2001) 64:67–73. doi: 10.1054/plef.2000.0239

131. Insua MF, Garelli A, Rotstein NP, German OL, Arias A, Politi LE. Cell cycle regulation in retinal progenitors by glia-derived neurotrophic factor and docosahexaenoic acid. Investig Ophthalmol Vis Sci. (2003) 44:2235–44. doi: 10.1167/iovs.02-0952

132. Wang Y, Chai Z, Wang M, Jin Y, Yang A, Li M. COPB2 suppresses cell proliferation and induces cell cycle arrest in human colon cancer by regulating cell cycle-related proteins. Exp Ther Med. (2018) 15:777–84. doi: 10.3892/etm.2017.5506

133. Chan JP, Wong BH, Chin CF, Galam DLA, Foo JC, Wong LC, et al. The lysolipid transporter Mfsd2a regulates lipogenesis in the developing brain. PLoS Biol. (2018) 16:e2006443. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.2006443

134. Nguyen LN, Ma D, Shui G, Wong P, Cazenave-Gassiot A, Zhang X, et al. Mfsd2a is a transporter for the essential omega-3 fatty acid docosahexaenoic acid. Nature. (2014) 509:503–6. doi: 10.1038/nature13241

135. Harel T, Quek DQY, Wong BH, Cazenave-Gassiot A, Wenk MR, Fan H, et al. Homozygous mutation in MFSD2A, encoding a lysolipid transporter for docosahexanoic acid, is associated with microcephaly and hypomyelination. Neurogenetics. (2018) 19:227–35. doi: 10.1007/s10048-018-0556-6

136. Kawakita E, Hashimoto M, Shido O. Docosahexaenoic acid promotes neurogenesis in vitro and in vivo. Neuroscience. (2006) 139:991–7. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.01.021

137. Bengoa-Vergniory N, Gorroño-Etxebarria I, González-Salazar I, Kypta RM. A switch from canonical to noncanonical Wnt signaling mediates early differentiation of human neural stem cells. Stem Cells. (2014) 32:3196–208. doi: 10.1002/stem.1807

138. Chenn A, Walsh CA. Regulation of cerebral cortical size by control of cell cycle exit in neural precursors. Science. (2002) 297:365–9. doi: 10.1126/science.1074192