- 1Department of Neurology, Sun Yat-sen Memorial Hospital, Sun Yat-sen University, Guangzhou, China

- 2Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Macau, Taipa, Macau

Background: Multiple sclerosis (MS) is an autoimmune and demyelinating disease. Genome-wide association studies have shown that MS is associated with many genetic variants in some human leucocyte antigen genes and other immune-related genes, however, those studies were mostly specific to Caucasian populations. We attempt to address whether the same associations are also true for Asian populations by conducting whole-exome sequencing on MS patients from southern China.

Methods: Genomic DNA was extracted from the peripheral blood mononucleocytes of 8 MS patients and 26 healthy controls and followed by exome sequencing.

Results: In total, 41,227 variants were found to have moderate to high impact on their protein products. After filtering per allele frequencies according to known database, 17 variants with the allele frequency <1% or variants with undetermined frequency were identified to be unreported and have significantly different frequencies between the MS patients and healthy controls. After validation via Sanger sequencing, one rare variant located in exon 7 of TRIOBP (Chr22: 37723520G>T, Ala322Ser, rs201693690) was found to be a novel missense variant.

Conclusion: MS in southern China may have association with unique genetic variants, our data suggest TRIOBP as a potential novel risk gene.

Introduction

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is one of the chronic inflammatory demyelinating diseases of the central nervous system (1). Although the causes of MS are still largely unclear, it is thought to be the consequence of the interaction of genetic and environmental factors (1–3). Epidemiological studies have shown that MS is much less prevalent in East Asia than Europe and North America (4–7), which may be attributed to different genetic bases underlying the susceptibility to MS in various populations.

For the past several decades, many genetic variants have been found to be associated with MS in the western populations (8–10). However, lots of risk variants could not be validated in Asian populations (2, 11). Furthermore, not only common variants but rare variants in protein-coding regions also play critical roles in the development of complex diseases (12, 13). In this study, we determined the genetic differences between MS patients and healthy controls in southern China using whole-exome sequencing (WES) to find MS-associated variants in this area.

Materials and Methods

Patients and Samples

The study was reviewed and approved by both ethic committees of Sun Yat-sen Memorial Hospital of Sun Yat-sen University and University of Macau. Patients with MS were diagnosed according to 2010 revision of the McDonald criteria (14) and were recruited from Jan. 1, 2016 to Dec. 31, 2016 in Sun Yat-sen Memorial Hospital. Healthy volunteers who were age- and gender-matched to the MS patients and had no history of autoimmune disorders, tumors, and other chronic illness such as hypertension and diabetes were also recruited. All MS patients and healthy volunteers were southern Chinese and included into the subsequent analysis after they had completed a written informed consent. Patients with underdetermined diagnoses, previous history of transplantation, previous plasmapheresis or stem cell therapy were excluded from the study. Peripheral whole blood was collected for preparing DNA libraries. Genomic DNA was extracted from peripheral blood mononucleocytes of each individual patient or healthy donor with a DNA extraction kit (Tiangen Biotech). Then, genomic DNA was sonicated into fragments of around 200 bp for preparing DNA libraries. DNA libraries for Illumina sequencing were constructed using the NEB Ultra II DNA Prep Kit (NEB) followed by quality verification via DNA High-Sensitivity Bioanalyzer assay (Agilent).

Whole-Exome Sequencing and Confirmation via Sanger Sequencing

Exome capture was performed with the TruSeq Rapid Exome Prep kit (Illumina). Multiple individual DNA libraries with different Illumina sequencing indexes were pooled together for exome capture and subsequent sequencing. Exon-enriched DNA library pools were sequenced by Illumina HiSeq 2500 platform (15). FastQC (16) tool was used to check the quality of raw fastq data generated by sequencing. The raw sequencing reads were aligned to the Ensembl (release 84) Human Genome Build 38 (GRCh38.p5) (17) using the Burrows-Wheeler Alignment tool (18). Reads which mapped to multiple locations were marked as duplicate using Picard tool (BroadInstitute)1 for future filtering during variant calling. Local realignment of reads around indels and base quality score recalibration was performed using the IndelRealigner and BaseRecalibrator modules of the Genome Analysis Toolkit (GATK) (19, 20). Finally, variants were called using HaplotypeCaller module and variant quality scores were recalibrated with VariantRecalibrator module of GATK.

True variants were identified only when the sequencing read depth of the mutation was equal to or more than 10 reads. SnpEff (21) was used for the general variant annotation purpose, and SnpSift (22) was used to add additional annotation from the 1000 Genomes Project (1KGP) (23), Exome Aggregation Consortium (ExAC) (24), and dbNSFP (25) variant databases. The variants which were predicted by SnpEff to have moderate or high impact on the gene products were screened for further analysis. Allele frequencies from both the 1KGP and ExAC were used as reference allele frequency in the different populations. For TRIOBP, the identified variants were confirmed through Sanger sequencing using target-specific primers as follows: forward GGACAGCACTGGGCAAGG, and reverse GGGAGTACAAGTAGGAAAAGAA.

Statistical Analysis

Variant frequencies were described as proportions, and comparisons of frequencies between different groups were analyzed using Fisher's exact tests. Two-tailed P < 0.05 was used as statistically significance.

Results

Characteristics of Samples

Eight MS patients and 26 healthy controls were included in the study. All the eight patients met the McDonald criteria (2010 revision) for MS, six of them were diagnosed as relapsing-remitting MS (RRMS) who had more than one clinical attack and had one or more typical lesions in two or more typical MS-affecting areas of the central nervous system (CNS), and the other two patients diagnosed as clinically isolated syndrome with more than one objective lesion in two or more typical MS-affecting areas and oligoclonal bands in cerebral spinal fluid. All the patients and healthy volunteers came from several provinces in southern China including Guangdong, Hunan, Guangxi and Fujian, which are within 1,000-km away from the hospital. All the healthy controls had no relative relationship with the patients. The MS patients were 31.63 ± 15.45 years old on average, while the healthy controls 31.24 ± 8.52 years old (P > 0.05). Female-to-male ratio happened to be 1:1 for the recruited MS patients (which is lower than the ratio for MS patients in general with P > 0.05 per Fisher's Exact Test) and 15:11 for the healthy controls.

Rare Variants Revealed via Whole-Exome Sequencing

On average, 2 × 37,614,484 pair-end reads (100 bp of read length) were generated after raw sequencing data filtering, mapping, and realignments, and per-base coverage of target exome regions was around 167 × per person. About 87.4% of exomes had sequencing depth > 1×, and 58.2% of exomes had sequencing depth > 10×.

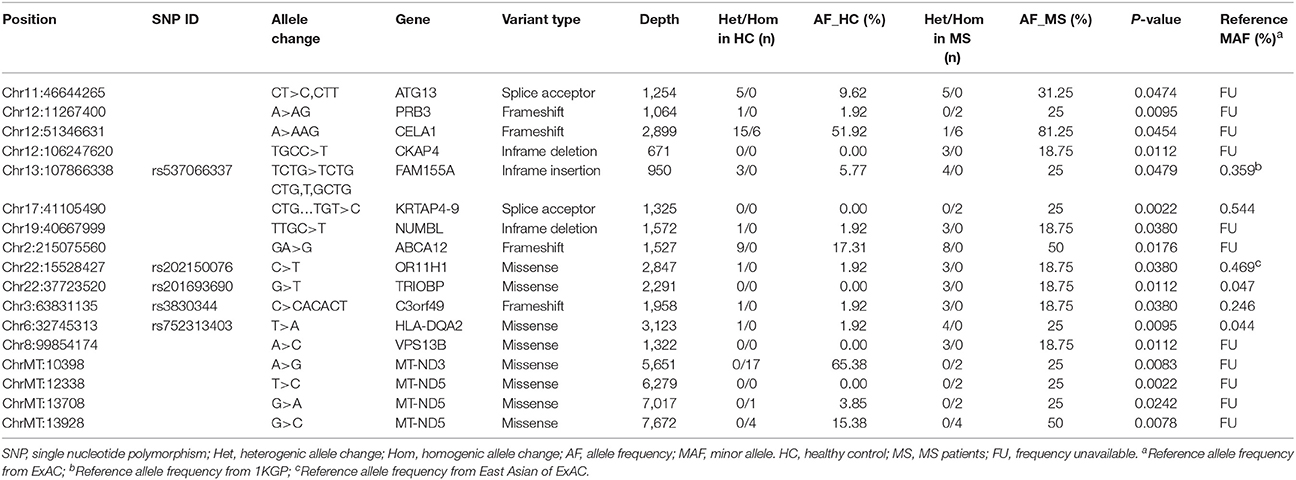

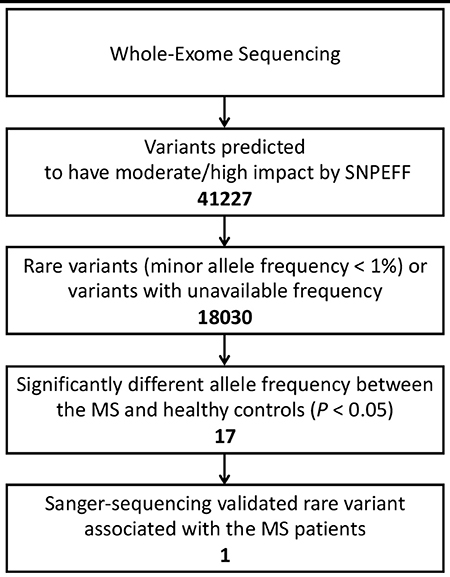

After annotations for all variants according to SnpEff database, a total of 41,227 variants which may have moderate or high impact on their translation products were found in the MS patients and healthy controls. We then filtered out common variants and identified 18,030 rare variants (with allele frequency <1% referring to both 1KGP/ExAC and East Asian populations of 1KGP/ExAC) or variants with undetermined allele frequency. Among the 18,030 variants, 17 variants (located in 15 genes) were identified with allele frequencies significantly different between the MS patients and healthy controls (P < 0.05) (Table 1, Figures 1, 2).

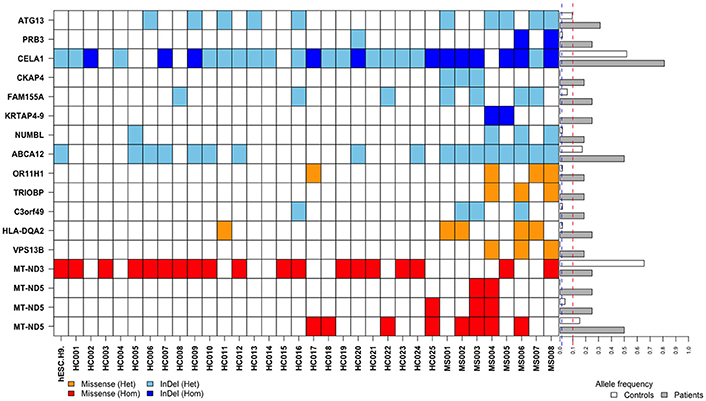

Figure 2. Distributions and frequencies of 17 rare and frequency-unavailable variants associated with the MS patients. Blocks in various colors indicate specific allele types (designated below) in specific loci of corresponding genes (listed in the left side) in each healthy control (HC) or MS patient (MS) (listed at the bottom). The horizontal bars in the right side indicate minor allele frequencies in the healthy controls (white bars) and MS patients (gray bars), respectively. Across these bars are two vertical and dashed lines in blue and red representing allele frequency of 1 and 10%, respectively.

A MS-Associated Missense in TRIOBP

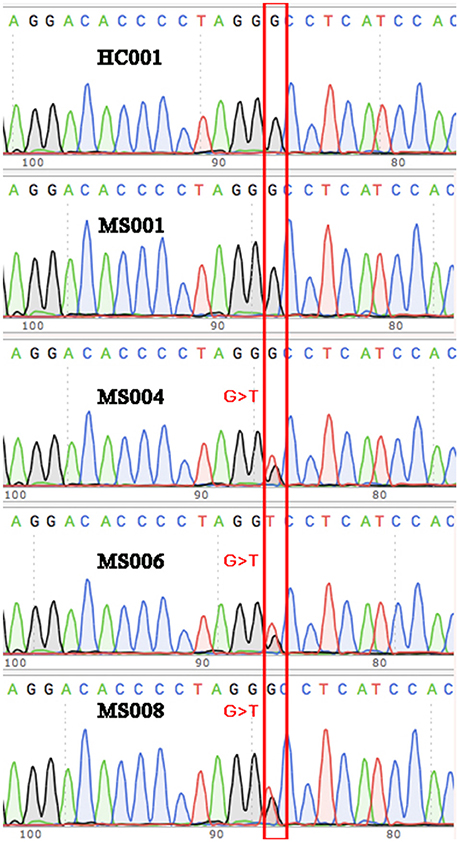

Among the 17 variants (possibly associated with MS) identified in our study, 6 were known rare variants. We validated the variants by Sanger sequencing (Figure 3), and found that one of the variants in the gene TRIOBP had significantly different allele frequency between the MS patients and healthy controls (P < 0.05).

Figure 3. Validation via Sanger sequencing. The G>T variant identified in three of the eight MS patients was verified via Sanger sequencing. Wild-type sequences were shown for some of the other MS patients and the healthy controls as representatives.

The variant is a missense (Chr22: 37723520G>T, Ala322Ser, rs201693690) located in the exon 7 of TRIOBP, causing an amino acid substitution (Ala322Ser). Among the eight MS patients, three had heterogeneous variants in Chr22: 37723520 (G/T). It has much higher allele frequency in the MS patients than the healthy controls (18.75 vs. 0%, P = 0.0112). This variant has been documented in the ExAC study, and found to be associated with deafness and schizophrenia. The frequency of allele T in Chr22:37723520 is only 0.047% in the total population of the ExAC database, indicating that it is a rare variant in human genome (Figure 2).

Discussion

In this study, we recruited 8 MS patients and 26 healthy controls in southern China. Due to the low morbidity of MS in southern China, we could not recruit more patients within the two-year study period. Following WES, we found 17 rare variants or variants with unknown allele frequency had significantly different allele frequencies between the MS patients and healthy controls, including a missense in TRIOBP (Chr22: 37723520G>T, Ala322Ser, rs201693690). TRIOBP may be a novel risk gene among southern Chinese.

The association between gene polymorphisms and MS has been investigated for decades. The most studied polymorphisms with MS are the human leukocyte antigen (HLA) genes. It has been found that MS risk is strongly associated with HLA-DRB1*15:01 and the related haplotype HLA-DRB1*15:01-DQA1*01:02-HLA-DQB1*06:02 in Caucasian populations such as Europeans and North Americans (2, 26). However, it is difficult to associate other HLA-related risk alleles with MS because strong linkage disequilibrium is present in the HLA-DRB1-DQA1-DQB1 regions (2). It is also difficult to confirm risk alleles in genes unrelated to HLA since their genetic effects may be much smaller than that of HLA-DRB1*15:01 (2). Furthermore, the associations of HLA-DR allele polymorphisms with MS found in Caucasian populations do not consistently apply to the Asian populations including Chinese. For example, HLA-DRB1*15:01 is not strongly associated with MS in Asian populations (11). The association of HLA-DRB1*15:01 with MS risk was weaker among northern Chinese than Caucasians, whereas no association of HLA-DRB1*15:01 with MS risk was found in southern Chinese (27). These findings indicate that polymorphisms in HLA-unrelated genes might be associated with MS among southern Chinese.

Recently, several genome-wide association studies (GWAS) with large numbers of samples had identified 57 non-HLA SNPs to be associated with MS (10). However, the populations involved in the study were mainly Caucasian populations. Another GWAS study from an Australian group showed that genetic loci for Epstein-Barr virus nuclear antigen-1 were positively associated with the risk of MS (28). However, the association cannot be found in Asian populations (29). These results suggest that MS-related genetic heterogeneity exists in different ethnic populations, and new studies on Asian populations are needed to identify genetic bases related to the development of MS in Asia. We performed the exome-sequencing study to discover whether any MS-associated variants differ between southern Chinese and Caucasians.

WES is one of the powerful next-generation sequencing techniques to explore global genetic variants in Mendelian inheritance disorders and many other complex diseases (30–32). It allows discovery of rare variants in coding sequences that may cause mutations in their protein products and subsequent disease phenotypes (31, 32) or contribute to heritability of complex traits. In this study, WES has revealed that the frequency of the rare variant in TRIOBP is significantly different between the MS patients and healthy controls, and its allele frequency is much higher than that of reference in known databases (18.75 vs. 0.047% in ExAC). And subsequent Sanger sequencing validated the variant in our samples. Although our sample size is very small, the much higher allele frequency in the MS patients than the healthy controls suggests that this variant may be associated with the risk of MS development in southern China.

This variant, which has not been identified in any MS GWAS studies, may play an important role in the development of MS among southern Chinese. TRIOBP is a gene encoding TRIO and F-actin binding protein, and locates in chromosome 22. The encoded protein interacts with trio, which regulates actin cytoskeleton organization, cell migration and cell growth, and it also stabilizes F-actin structures (33, 34). Previous studies have found that mutations or variants of TRIOBP cause genetic sensorineural hearing impairments (35, 36), and abnormal TRIOBP protein aggregation leads to chronic mental illness (37, 38). However, the mechanism for how TRIOBP affects immune or inflammation is unknown.

Our exome-sequencing also identified several variants in the other genes which have higher allele frequencies in the MS patients than the normal controls. However, there is no referable information for the allele frequency for some of the variants (e.g., CKAP4, NUMBL, and VPS13B). The other variants such as the missense in HLA-DQA2 (Chr6: 32745313T>A, rs752313403), which had much higher allele frequency in the MS patients than the healthy controls, could not be validated through Sanger sequencing. Thus, we cannot include it as a risk variant.

Furthermore, other etiologic factors can trigger MS or increase the susceptibility to MS. For example, it has been proposed that HLA2TA mRNA level can be reduced by the active replication of human herpesvirus 6 in MS patients (39, 40). It is intriguing to determine whether these external etiologic factors are differentially distributed among various populations. Simultaneous testing of both genetic and environmental etiologic factors may further elucidate the correlations.

In conclusion, this study on MS patients from southern China has identified a missense rare variant in TRIOBP (Chr22: 37723520G>T, Ala322Ser, rs201693690) that may be associated with MS. Further study is necessary to verify the above findings in a larger sample size, and animal models are needed to confirm the role of this and other potential variants.

Author Contributions

HW contributes to recruit study participants, collect samples, prepare exome sequencing samples, and write manuscript. LP contributes to analyze exome sequencing samples. XR contributes to recruit study participants and collect samples. EL contributes to prepare exome sequencing samples. KW contributes to prepare exome sequencing samples and analyze exome sequencing samples. YP contributes to supervise whole project, design the study, recruit study participants, collect samples, and write manuscript. R-HX contributes to supervise whole project, design the study, prepare exome sequencing samples, and write manuscript.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgements

We appreciate the excellent services provided for this study by the Genomics Core of Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Macau. This work was supported by University of Macau Research Committee funds MYRG #2015-00169-FHS, 2016-00070-FHS, 2017-00124-FHS, and Macau Science and Technology Development Fund (FDCT) #128-2014-A3, 028/2015/A1, and 095/2017/A2 to R-HX. This work was also supported by the Key Project of Product, Study and Research of Guangzhou City (No. 201508020058) to Ying Peng and National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC, No. 81601042) to HW. This work was performed in part at the High Performance Computing Cluster (HPCC) which is supported by Information and Communication Technology Office (ICTO) of the University of Macau. In particular, we thank Jacky Chan and William Pang for their continuous supports on the HPCC.

Footnotes

1. ^Broadinstitute Picard Tools - By Broad Institute. http://broadinstitute.github.io/picard/index.html

References

1. Compston A, Coles A. Multiple sclerosis. Lancet (2008) 372:1502–17. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61620-7

2. Dyment DA, Ebers GC, Sadovnick AD. Genetics of multiple sclerosis. Lancet Neurol. (2004) 3:104–10. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(03)00663-X

3. Sawcer S, Franklin RJ, Ban M. Multiple sclerosis genetics. Lancet Neurol. (2014) 13:700–9. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(14)70041-9

4. Cheng Q, Miao L, Zhang J, Ding SJ, Liu ZG, Wang X, et al. A population-based survey of multiple sclerosis in Shanghai, China. Neurology (2007) 68:1495–500. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000260695.72980.b7

5. Evans C, Beland SG, Kulaga S, Wolfson C, Kingwell E, Marriott J, et al. Incidence and prevalence of multiple sclerosis in the Americas: a systematic review. Neuroepidemiology (2013) 40:195–210. doi: 10.1159/000342779

6. Kingwell E, Marriott JJ, Jette N, Pringsheim T, Makhani N, Morrow SA, et al. Incidence and prevalence of multiple sclerosis in Europe: a systematic review. BMC Neurol. (2013) 13:128. doi: 10.1186/1471-2377-13-128

7. MSIF. (2013). Atlas of MS 2013. MSIF. Available online at: https://www.msif.org/resources/

8. Olerup O, Hillert J. HLA class II-associated genetic susceptibility in multiple sclerosis: a critical evaluation. Tissue Antigens (1991) 38:1–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0039.1991.tb02029.x

9. Harbo HF, Lie BA, Sawcer S, Celius EG, Dai KZ, Oturai A, et al. Genes in the HLA class I region may contribute to the HLA class II-associated genetic susceptibility to multiple sclerosis. Tissue Antigens (2004) 63:237–47. doi: 10.1111/j.0001-2815.2004.00173.x

10. International Multiple Sclerosis Genetics Consortium, Wellcome Trust Case Control Consortium, Sawcer S, Hellenthal G, Pirinen M, Spencer CC, et al. Genetic risk and a primary role for cell-mediated immune mechanisms in multiple sclerosis. Nature (2011) 476:214–9. doi: 10.1038/nature10251

11. Fukazawa T, Yamasaki K, Ito H, Kikuchi S, Minohara M, Horiuchi I, et al. Both the HLA-CPB1 and -DRB1 alleles correlate with risk for multiple sclerosis in Japanese: clinical phenotypes and gender as important factors. Tissue Antigens (2000) 55:199–205. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-0039.2000.550302.x

12. Eichler EE, Flint J, Gibson G, Kong A, Leal SM, Moore JH, et al. Missing heritability and strategies for finding the underlying causes of complex disease. Nat Rev Genet. (2010) 11:446–50. doi: 10.1038/nrg2809

13. Lee S, Abecasis GR, Boehnke M, Lin X. Rare-variant association analysis: study designs and statistical tests. Am J Hum Genet. (2014) 95:5–23. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2014.06.009

14. Polman CH, Reingold SC, Banwell B, Clanet M, Cohen JA, Filippi M, et al. Diagnostic criteria for multiple sclerosis: 2010 revisions to the McDonald criteria. Ann Neurol. (2011) 69:292–302. doi: 10.1002/ana.22366

15. Bentley DR, Balasubramanian S, Swerdlow HP, Smith GP, Milton J, Brown CG, et al. Accurate whole human genome sequencing using reversible terminator chemistry. Nature (2008) 456:53–9. doi: 10.1038/nature07517

16. Andrews S. (2014). Babraham Bioinformatics-FastQC A Quality Control tool for High Throughput Sequence Data. Available online at https://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc/ [Accessed].

17. Aken BL, Ayling S, Barrell D, Clarke L, Curwen V, Fairley S, et al. The Ensembl gene annotation system. Database (2016) 2016:baw093. doi: 10.1093/database/baw093

18. Li H, Durbin R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics (2009) 25:1754–60. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp324

19. Mckenna A, Hanna M, Banks E, Sivachenko A, Cibulskis K, Kernytsky A, et al. The Genome Analysis Toolkit: a MapReduce framework for analyzing next-generation DNA sequencing data. Genome Res. (2010) 20:1297–303. doi: 10.1101/gr.107524.110

20. Van Der Auwera GA, Carneiro MO, Hartl C, Poplin R, Del Angel G, Levy-Moonshine A, et al. From FastQ data to high confidence variant calls: the Genome Analysis Toolkit best practices pipeline. Curr Protoc Bioinformatics (2013) 43:11.10.1–11.10.33. doi: 10.1002/0471250953.bi1110s43

21. Cingolani P, Platts A, Wang Le L, Coon M, Nguyen T, Wang L, et al. A program for annotating and predicting the effects of single nucleotide polymorphisms, SnpEff: SNPs in the genome of Drosophila melanogaster strain w1118; iso-2; iso-3. Fly (2012b) 6:80–92. doi: 10.4161/fly.19695

22. Cingolani P, Patel VM, Coon M, Nguyen T, Land SJ, Ruden DM, et al. Using Drosophila melanogaster as a model for genotoxic chemical mutational studies with a new program, SnpSift. Front Genet. (2012a) 3:35. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2012.00035

23. Genomes Project C, Auton A, Brooks LD, Durbin RM, Garrison EP, Kang HM, et al. A global reference for human genetic variation. Nature (2015) 526:68–74. doi: 10.1038/nature15393

24. Lek M, Karczewski KJ, Minikel EV, Samocha KE, Banks E, Fennell T, et al. Analysis of protein-coding genetic variation in (2016) 60,706 humans. Nature 536:285–91. doi: 10.1038/nature19057

25. Liu X, Wu C, Li C, Boerwinkle E. dbNSFP v3.0: a one-stop database of functional predictions and annotations for human nonsynonymous and splice-site SNVs. Hum Mutat. (2016) 37:235–41. doi: 10.1002/humu.22932

26. Moutsianas L, Jostins L, Beecham AH, Dilthey AT, Xifara DK, Ban M, et al. Class II HLA interactions modulate genetic risk for multiple sclerosis. Nat Genet. (2015) 47:1107–13. doi: 10.1038/ng.3395

27. Qiu W, James I, Carroll WM, Mastaglia FL, Kermode AG. HLA-DR allele polymorphism and multiple sclerosis in Chinese populations: a meta-analysis. Mult Scler. (2011) 17:382–8. doi: 10.1177/1352458510391345

28. Zhou Y, Zhu G, Charlesworth JC, Simpson, S Jr, Rubicz R, Goring HH, et al. Genetic loci for Epstein-Barr virus nuclear antigen-1 are associated with risk of multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. (2016) 22:1655–64. doi: 10.1177/1352458515626598

29. Mcelroy JP, Isobe N, Gourraud PA, Caillier SJ, Matsushita T, Kohriyama T, et al. SNP-based analysis of the HLA locus in Japanese multiple sclerosis patients. Genes Immun. (2011) 12:523–30. doi: 10.1038/gene.2011.25

30. Bamshad MJ, Ng SB, Bigham AW, Tabor HK, Emond MJ, Nickerson DA, et al. Exome sequencing as a tool for Mendelian disease gene discovery. Nat Rev Genet. (2011) 12:745–55. doi: 10.1038/nrg3031

31. Do R, Kathiresan S, Abecasis GR. Exome sequencing and complex disease: practical aspects of rare variant association studies. Hum Mol Genet. (2012) 21:R1–9. doi: 10.1093/hmg/dds387

32. Kosmicki JA, Churchhouse CL, Rivas MA, Neale BM. Discovery of rare variants for complex phenotypes. Hum Genet. (2016) 135:625–34. doi: 10.1007/s00439-016-1679-1

33. Seipel K, Medley QG, Kedersha NL, Zhang XA, O'brien SP, Serra-Pages C, et al. (1999). Trio amino-terminal guanine nucleotide exchange factor domain expression promotes actin cytoskeleton reorganization, cell migration and anchorage-independent cell growth. J Cell Sci. 112 (Pt 12):1825–34.

34. Seipel K, O'brien SP, Iannotti E, Medley QG, Streuli M. Tara, a novel F-actin binding protein, associates with the Trio guanine nucleotide exchange factor and regulates actin cytoskeletal organization. J Cell Sci. (2001) 114:389–99.

35. Kitajiri S, Sakamoto T, Belyantseva IA, Goodyear RJ, Stepanyan R, Fujiwara I, et al. Actin-bundling protein TRIOBP forms resilient rootlets of hair cell stereocilia essential for hearing. Cell (2010) 141:786–98. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.03.049

36. Wesdorp M, Van De Kamp JM, Hensen EF, Schraders M, Oostrik J, Yntema HG, et al. Broadening the phenotype of DFNB28: mutations in TRIOBP are associated with moderate, stable hereditary hearing impairment. Hear Res. (2017) 347:56–62. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2016.12.017

37. Bradshaw NJ, Bader V, Prikulis I, Lueking A, Mullner S, Korth C. Aggregation of the protein TRIOBP-1 and its potential relevance to schizophrenia. PLoS ONE (2014) 9:e111196. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0111196

38. Bradshaw NJ, Yerabham ASK, Marreiros R, Zhang T, Nagel-Steger L, Korth C. An unpredicted aggregation-critical region of the actin-polymerizing protein TRIOBP-1/Tara, determined by elucidation of its domain structure. J Biol Chem. (2017) 292:9583–98. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M116.767939

39. Dominguez-Mozo MI, Garcia-Montojo M, De Las Heras V, Garcia-Martinez A, Arias-Leal AM, Casanova I, et al. MHC2TA mRNA levels and human herpesvirus 6 in multiple sclerosis patients treated with interferon beta along two-year follow-up. BMC Neurol. (2012) 12:107. doi: 10.1186/1471-2377-12-107

Keywords: multiple sclerosis, whole-exome sequencing, single nucleotide polymorphism, human leucocyte antigen, TRIOBP

Citation: Wang H, Pardeshi LA, Rong X, Li E, Wong KH, Peng Y and Xu R-H (2018) Novel Variants Identified in Multiple Sclerosis Patients From Southern China. Front. Neurol. 9:582. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2018.00582

Received: 14 March 2018; Accepted: 27 June 2018;

Published: 25 July 2018.

Edited by:

Fabienne Brilot, University of Sydney, AustraliaReviewed by:

Maria José Sá, Centro Hospitalar São João, PortugalMoussa Antoine Chalah, Hôpitaux Universitaires Henri Mondor, France

Copyright © 2018 Wang, Pardeshi, Rong, Li, Wong, Peng and Xu. This is an openaccess article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Ying Peng, cGVuZ3kyQG1haWwuc3lzdS5lZHUuY24=

Ren-He Xu, cmVuaGV4dUB1bWFjLm1v

Hongxuan Wang

Hongxuan Wang Lakhansing Arun Pardeshi

Lakhansing Arun Pardeshi Xiaoming Rong1

Xiaoming Rong1 Koon Ho Wong

Koon Ho Wong