94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Cell. Neurosci., 26 April 2019

Sec. Cellular Neurophysiology

Volume 13 - 2019 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fncel.2019.00163

This article is part of the Research TopicCellular Neurophysiology Editors’ Pick 2021View all 19 articles

Despite 50+ years of clinical use as anxiolytics, anti-convulsants, and sedative/hypnotic agents, the mechanisms underlying benzodiazepine (BZD) tolerance are poorly understood. BZDs potentiate the actions of gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA), the primary inhibitory neurotransmitter in the adult brain, through positive allosteric modulation of γ2 subunit containing GABA type A receptors (GABAARs). Here we define key molecular events impacting γ2 GABAAR and the inhibitory synapse gephyrin scaffold following initial sustained BZD exposure in vitro and in vivo. Using immunofluorescence and biochemical experiments, we found that cultured cortical neurons treated with the classical BZD, diazepam (DZP), presented no substantial change in surface or synaptic levels of γ2-GABAARs. In contrast, both γ2 and the postsynaptic scaffolding protein gephyrin showed diminished total protein levels following a single DZP treatment in vitro and in mouse cortical tissue. We further identified DZP treatment enhanced phosphorylation of gephyrin Ser270 and increased generation of gephyrin cleavage products. Selective immunoprecipitation of γ2 from cultured neurons revealed enhanced ubiquitination of this subunit following DZP exposure. To assess novel trafficking responses induced by DZP, we employed a γ2 subunit containing an N terminal fluorogen-activating peptide (FAP) and pH-sensitive green fluorescent protein (γ2pHFAP). Live-imaging experiments using γ2pHFAP GABAAR expressing neurons identified enhanced lysosomal targeting of surface GABAARs and increased overall accumulation in vesicular compartments in response to DZP. Using fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) measurements between α2 and γ2 subunits within a GABAAR in neurons, we identified reductions in synaptic clusters of this subpopulation of surface BZD sensitive receptor. Additional time-series experiments revealed the gephyrin regulating kinase ERK was inactivated by DZP at multiple time points. Moreover, we found DZP simultaneously enhanced synaptic exchange of both γ2-GABAARs and gephyrin using fluorescence recovery after photobleaching (FRAP) techniques. Finally we provide the first proteomic analysis of the BZD sensitive GABAAR interactome in DZP vs. vehicle treated mice. Collectively, our results indicate DZP exposure elicits down-regulation of gephyrin scaffolding and BZD sensitive GABAAR synaptic availability via multiple dynamic trafficking processes.

GABAARs are ligand-gated ionotropic chloride (Cl-) channels responsible for the majority of fast inhibitory neurotransmission in the adult CNS. The most prevalent synaptic GABAAR subtype is composed of two α, two β, and a γ2 subunit forming a heteropentamer (Uusi-Oukari and Korpi, 2010). Benzodiazepines (BZDs) are a widely used clinical sedative-hypnotic drug class that selectively bind between the interface of a GABAAR γ2 subunit and either an α1/2/3/5 subunit (Vinkers and Olivier, 2012). Receptors containing these α subunits are considered to be primarily synaptic, with the exception of α5, which is localized both synaptically and extrasynaptically (Brady and Jacob, 2015). Positive allosteric modulation by BZD enhances GABAAR inhibition by increasing the binding affinity of GABA and increasing channel opening frequency (Uusi-Oukari and Korpi, 2010). Recent cryo-electron microscopy publications have provided unprecedented structural and pharmacological information about benzodiazepine-sensitive GABAARs and the benzodiazepine binding site (Phulera et al., 2018; Zhu et al., 2018; Laverty et al., 2019; Masiulis et al., 2019) reinvigorating interest in the molecular actions of BZD drugs. It is known that the potentiating effect of BZDs are lost after prolonged or high dose acute exposure (Tietz et al., 1989; Holt et al., 1999), characterized first by a loss of sedative/hypnotic activity followed by the anti-convulsant properties behaviorally (Lister and Nutt, 1986; Wong et al., 1986; File et al., 1988; Bateson, 2002). The induction of BZD tolerance occurs in part due to the uncoupling of allosteric actions between GABA and BZD (Gallager et al., 1984; Marley and Gallager, 1989), a process that appears to rely on GABAAR receptor internalization (Ali and Olsen, 2001; Gutierrez et al., 2014). We have previously shown that 24 h BZD treatment leads to decreased surface and total levels of the α2 subunit in cultured hippocampal neurons that was dependent on lysosomal-mediated degradation (Jacob et al., 2012); however, the process by which the α2 subunit is selectively targeted to lysosomes is still unknown. GABAAR subunit ubiquitination and subsequent degradation at proteasomes or lysosomes modulates cell surface expression of receptors (Saliba et al., 2007; Arancibia-Carcamo et al., 2009; Crider et al., 2014; Jin et al., 2014; Di et al., 2016). Ubiquitination of the γ2 subunit is the only currently known mechanism identified to target internalized surface GABAARs to lysosomes (Arancibia-Carcamo et al., 2009).

Another major regulator of GABAAR efficacy is postsynaptic scaffolding. Confinement at synaptic sites maintains receptors at GABA axonal release sites for activation. Furthermore, this limits receptor diffusion into the extrasynaptic space where internalization occurs (Bogdanov et al., 2006; Gu et al., 2016). The scaffolding protein gephyrin is the main organizer of GABAAR synaptic localization and density, as gephyrin knock-down and knock-out models show dramatic reductions in γ2- and α2-GABAAR clustering (Kneussel et al., 1999; Jacob et al., 2005). Evidence suggests gephyrin interacts directly with GABAAR α1, α2, α3, α5, β2, and β3 subunits (Tretter et al., 2008; Maric et al., 2011; Mukherjee et al., 2011; Kowalczyk et al., 2013; Tyagarajan and Fritschy, 2014; Brady and Jacob, 2015). Gephyrin recruitment is involved in inhibitory long term potentiation (Petrini et al., 2014; Flores et al., 2015), while its dispersal coincides with GABAAR diffusion away from synapses (Jacob et al., 2005; Bannai et al., 2009). Extensive post-translational modifications influence gephyrin function (Zacchi et al., 2014; Ghosh et al., 2016). Accordingly, expression of gephyrin phosphorylation site mutants revealed complex effects on GABAAR diffusion and gephyrin ultrastructure and scaffolding (Ghosh et al., 2016; Battaglia et al., 2018). Phosphorylation at the gephyrin serine 270 (Ser270) site has been particularly characterized to negatively modulate scaffold clustering and density, in part by enhancing calpain-1 protease mediated degradation of gephyrin (Tyagarajan et al., 2013). Given the well-established interdependent relationship between gephyrin and the γ2 subunit in maintaining receptor synaptic integrity (Essrich et al., 1998; Kneussel et al., 1999; Schweizer et al., 2003; Alldred et al., 2005; Jacob et al., 2005; Li et al., 2005), impaired postsynaptic scaffolding should affect both pre-existing and newly inserted GABAAR clustering and ultimately the efficacy of inhibitory neurotransmission. Thus a central unanswered question is if BZD exposure causes changes in gephyrin phosphorylation or protein levels.

Here we demonstrate that 12–24 h treatment with the BZD diazepam (DZP) leads to a reduction in total γ2 subunit and full-length gephyrin levels in vitro and in vivo. This reduction occurred coincident with enhanced γ2 subunit ubiquitination, but resulted in no significant change in overall γ2 surface levels. Using our recently published dual fluorescent BZD-sensitive GABAAR reporter (γ2pHFAP), we further show that cell surface γ2-GABAARs are more frequently targeted to lysosomes after DZP exposure. Forester resonance energy transfer (FRET) experiments further confirmed specific loss of synaptic α2/γ2 GABAAR levels following DZP treatment. The scaffolding protein gephyrin also demonstrated augmented phosphorylation at Ser270, increased cleavage and was significantly decreased in membrane and cytosolic compartments. Fluorescence recovery after photobleaching (FRAP) assays identified that DZP treatment increased the simultaneous recovery of γ2-GABAAR and gephyrin at synaptic sites, indicating reduced receptor confinement and accelerated exchange between the synaptic and extrasynaptic GABAAR pool. This process was reversed by the BZD site antagonist Ro 15-1788. Lastly, co-immunoprecipitation, quantitative mass spectrometry and bioinformatics analysis revealed shifts in the γ2-GABAAR interactome toward trafficking pathways in vivo. Together, these data suggest that DZP exposure causes a compensatory decrease in inhibitory neurotransmission by reducing BZD-sensitive GABAAR and gephyrin confinement at synapses and via ubiquitination and lysosomal targeting of γ2.

Cortical neurons were prepared from embryonic day 18 rats and nucleofected with constructs at plating (Amaxa). The γ2pHFAP construct was characterized in Lorenz-Guertin et al. (2017) and RFP-gephyrin was described in Brady and Jacob (2015). The γ2RFP construct was generated by PCR cloning and fully sequenced: the red fluorescent protein mCherry replaced pHluorin in the previously published γ2pHGFP construct (Jacob et al., 2005). GFP-ubiquitin was a gift from Nico Dantuma (Addgene plasmid # 11928) (Dantuma et al., 2006). 8–10 weeks old male C57BL/6J mice (Jackson Laboratory) were maintained on a reverse 12 h dark/light schedule. Mouse cortical brain tissue was collected and flash frozen 12 h after I.P. injection with either vehicle or diazepam [in 40% PEG, 10% EtOH, 5% Na Benzoate, 1.5% Benzyl alcohol (Hospira)]. All procedures were approved by the University of Pittsburgh Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Diazepam (cell culture, Sigma; injections, Hospira); Ro 15-1788 (Tocris Bioscience); calpain-1 inhibitor MDL-28170 (Santa Cruz); L-glutamic acid (Tocris Bioscience). Primary antibodies: rabbit GAPDH (WB) (14C10, Cell Signaling); guinea pig GAD-65 (IF) (198104, Synaptic Systems); rabbit γ2 GABAAR subunit (IF, WB, and IP) (224003, Synaptic Systems); rabbit gephyrin (WB) (sc-14003, Santa Cruz); rabbit gephyrin (IF, total) (147002, Synaptic Systems) (antibody validation Supplementary Figure S1); mouse gephyrin mAb7a (IF, phospho) (147011, Synaptic Systems); chicken GFP (WB) (GFP-1020, Aves); rabbit (P)ERK (WB) (4370, Cell Signaling); mouse ERK (WB) (9107, Cell Signaling); rabbit (P)GSK3β (WB) (9322, Cell Signaling); rabbit GSK3β (WB) (9315. Cell Signaling); rabbit CDK5 (WB) (2506, Cell Signaling). MG-BTau dye prepared as in Lorenz-Guertin et al. (2017).

Measurements were made on days in vitro (DIV) 15–19 cortical neurons. Live-imaging performed in Hepes-buffered saline (HBS), containing the following (in mM): 135 NaCl, 4.7 KCl, 10 Hepes, 11 glucose, 1.2 MgCl2, and 2.5 CaCl2 (adjusted to pH 7.4 with NaOH). Images were acquired using a Nikon A1 confocal microscope with a 60× oil objective (N.A., 1.49) at 3× zoom. Data were analyzed in NIS Elements software (Nikon, N.Y.). Measurements were taken from whole cell or averaged from three dendritic 10 μm regions of interest (ROI) per cell. For fixed imaging, media was quickly removed and coverslips were washed twice with Dulbecco’s Phosphate Buffered Saline (DPBS) and immediately fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and then blocked in PBS containing 10% fetal bovine serum and 0.5% bovine serum albumin. Surface antibody staining was performed under non-permeabilized conditions overnight at 4°C. Intracellular staining was performed overnight at 4°C following 0.2% Triton-X permeabilization for 10 min in blocking solution. Synaptic sites were determined during analysis by binary thresholds and colocalization with GAD-65. Extrasynaptic intensity was measured by taking the total dendrite ROI sum intensity minus background and synaptic fluorescence intensity. Dendritic fluorescence was measured using binary thresholds. Experimental conditions were blinded during image acquisition and analysis. The ROUT test (Q = 1%) or Grubbs’ Test (alpha = 0.05) was used to remove a single outlier from a data set.

Neuron surface and lysosomal-association assays utilized MG-BTau dye for surface receptor pulse-labeling. DIV 15–16 neurons were treated with vehicle or DZP for 8–12 h, then pulse labeled with 100 nM MG-BTau for 2 min at room temperature in HBS. Neurons were then washed 5× times with HBS and returned to conditioned media ± DZP for 1 h. To identify lysosomal targeting, 50 nM LysoTracker Blue DND-22 (Life Technologies) and the lysosomal inhibitor, Leupeptin (200 μM Amresco), was added 30 min prior to imaging. Following incubation, neurons were washed and imaged in 4°C HBS. Two–three neurons were immediately imaged per culture dish within 10 min of washing. For image analysis, independent ROIs were drawn to capture the soma, three 10 μm sections of dendrite and the whole cell. Binary thresholds and colocalization measurements were performed to identify MG-BTau, pHGFP synaptic GABAAR clusters and lysosomes. Total surface pHGFP expression was determined by taking the entire cell surface signal following background subtraction.

DIV 15–16 neurons were washed and continuously perfused with HBS + treatment at room temperature. Multiposition acquisition was used to image 2–3 neurons per dish. An initial image was taken to identify surface γ2pHFAP GABAARs. Neurons were then perfused with NH4Cl solution to collapse the cellular pH gradient and were reimaged. NH4Cl solution (in mM): 50 NH4Cl, 85 NaCl, 4.7 KCl, 10 Hepes, 11 glucose, 1.2 MgCl2, and 2.5 CaCl2 (adjusted to pH 7.4 with NaOH). pHGFP intensity was measured following background subtraction and smoothing. Surface/total levels were determined by dividing the first image (surface only) from the second image (total). The spot detection tool in Nikon Elements was used to selectively count larger intracellular vesicles positive for γ2pHFAP. A stringent threshold was set to identify brightly fluorescent circular objects with a circumference of approximately 0.75 μm. Values reflect new vesicle objects that were only seen after NH4Cl perfusion (second image – first image).

The α2 pHGFP (α2pH) construct was previously published (Tretter et al., 2008) and the γ2RFP construct was generated by PCR cloning and fully sequenced. DIV 15–16 neurons were treated with Veh or DZP for 20–28 h, then washed and continuously perfused with HBS at room temperature. Images were acquired with a 60× objective at 2× zoom. For each cell, an initial image was acquired containing two channels to identify surface α2pH (excited by 488 laser, emission band pass filter 500–550) and γ2RFP participating in FRET (excited 488 FRET, emission band pass filter 575–625 nm, FRET channel). A second, single channel image was taken immediately following with only 561 nm excitation to reveal total γ2RFP levels (excited by 561 laser, emission band pass filter 575–625 nm). For synaptic quantifications, binary thresholding based on intensity was applied with smoothing and size exclusion (0–3 μm) factors. FRET and 561 channel binaries shared identical minimum and maximum binary threshold ranges. Individual synaptic ROIs were created to precisely target and measure synaptic clusters containing both α2pH and γ2RFP. Manual trimming and single pixel removal were used to remove signal not meeting the criteria of a receptor cluster. Restriction criteria were applied in the following order: (1) at least 15 synapses measured per cell, (2) FRET γ2RFP: raw γ2RFP sum intensity ratio must be less than one, (3) synaptic α2pH mean intensity of at least 500, and (4) α2pH sum intensity limit of 300% of average sum intensity. ROI data was then normalized to vehicle control as percent change. The percentage of RFP participating in FRET was also calculated using FRET RFP:Total RFP ratio.

Fluorescence resonance energy transfer activity was directly assessed by acceptor (γ2RFP) photobleaching. Photobleaching ROIs were implemented on 2 synapses per cell. Pre-bleaching images were acquired every 5 s, followed by a γ2RFP photobleaching event using 80% 561 nm laser power. After photobleaching, image capturing resumed without delay using pre-bleach laser power settings for 2 min. Image analysis incorporated background subtraction and the measurement of percent change in α2pH/FRET γ2RFP ratio over the time course. FRET efficacy measurements compared directly adjacent α2pH and γ2RFP subunits in a GABAAR complex. Live-imaging with perfusion of pH 6.0 extracellular imaging saline solution (MES) was used to quench the pH-dependent GFP fluorescence from the α2pH donor fluorophores and show the dependence of FRET on surface α2pH fluorescence. Acidic extracellular saline solution, MES solution pH 6.0 (in mM): 10 MES, 135 NaCl, 4.7 KCl, 11 glucose, 1.2 MgCl2, and 2.5 CaCl2 (adjusted to pH 7.4 with NaOH). Images were collected under HBS conditions for 1 min at 20 s intervals, and then followed by a 2 min MES wash with the same imaging interval to quench donor emissions. FRET RFP mean intensity was measured under both conditions and normalized to HBS. Percent or fold change in FRET RFP emissions were reported as indicated.

Neurons were washed and media was replaced with HBS + treatment. Imaging was performed in an enclosed chamber at 37°C. An initial image was taken for baseline standardization. Photobleaching was performed by creating a stimulation ROI box encompassing two or more dendrites. This stimulation region was photobleached using the 488 and 561 lasers at 25% power for 1 min. The same stimulation ROI was used for every cell in an experiment. Immediately following photobleaching, 10 nM MG-Tau dye was added to the cell culture dish to re-identify surface synaptic GABAAR clusters. Time-lapse imaging was then started every 2 min for 60 min. During image analysis, objects were only considered synaptic if they demonstrated colocalization with γ2pHFAP pHGFP signal, RFP-gephyrin signal and had obvious surface MG-BTau fluorescence. ROIs were drawn measuring the rate of fluorescence recovery at 4–8 synaptic sites and one extrasynaptic site (10 μm long region; Bezier tool) per cell. For data analysis, synapse post-bleach fluorescence intensity time point data was first normalized to pre-bleach fluorescence intensity (post-bleach/pre-bleach). Normalized synapse post-bleach data was then calculated as percent change from t0 [(tx/t0)∗100, where x = min]. Individual synapses were then averaged to calculate fluorescence recovery and statistically significant changes across time points.

Protein concentration was determined by BCA protein assay for all biochemistry. Neurons were lysed in denaturing buffer for immunoprecipitation: 50 mM Tris HCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1% SDS, 2 mM Na3VO4, 10 mM NaF, 50 mM N-ethylmaleimide, protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma). Lysates were sonicated and heated at 50°C for 20 min, then diluted 1:5 in RIPA buffer (50 mM Tris HCl pH 7.6, 150 mM NaCl, 1% Igepal, 0.5% Sodium deoxycholate, 1 mM EDTA, 2 mM Na3VO4, 10 mM NaF, 50 mM N-ethylmaleimide, protease inhibitor cocktail). Standard immunoprecipitation procedures were performed using overnight incubation with γ2 subunit antibody or rabbit IgG (sci2027; Sigma), 1 h incubation with Protein A Sepharose 4B beads (Invitrogen), three RIPA buffer washes, and loading for SDS-PAGE. After electrophoresis and transfer to nitrocellulose membrane, samples were probed with primary antibody overnight followed by the appropriate horseradish peroxide (HRP)-coupled secondary antibody.

Cultured neurons were lysed using fractionation buffer: 50 mM Tris-HCl, 50 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 2 mM Na3VO4, 10 mM NaF, 320 mM sucrose, 0.25% igepal, and protease inhibitor cocktail. Lysates were spun at 88,881 g for 30 min at 4°C to separate pellet (membrane) from supernatant (cytosol). Fraction integrity was tested by localization specific markers in all experiments (Supplementary Figure S2 and data not shown).

Mice were intraperitoneally (I.P.) injected with vehicle control or 10 mg/kg DZP and sacrificed 12 h post-injection (n = 4 mice per treatment). Mouse cortical tissue was homogenized in co-IP buffer (50 mM Tris HCl pH 7.6, 50 mM NaCl, 0.25% Igepal, 1 mM EDTA, 2 mM Na3VO4, 10 mM NaF, 50 mM N-ethylmaleimide, and Sigma protease inhibitor cocktail) using a Dounce homogenizer. Tissue was solubilized with end-over-end mixing at 4°C for 15 min, and then spun at 1,000 g to remove non-solubilized fractions. Each immunoprecipitation tube contained 375 μg of tissue lysate brought up to 1 ml volume using co-IP buffer. Lysates were precleared using Protein A Sepharose 4B beads (Invitrogen) for 1 h at 4°C. Lysate was then immunoprecipitated overnight with 2.5 μg rabbit γ2 subunit antibody (224003, Synaptic Systems) or 2.5 μg rabbit IgG (2027, Santa Cruz). The next day, 40 μl Protein A Sepharose slurry was added and mixed for 2 h at 4°C on a nutator. Beads were then washed 3× at 4°C on a nutator in 1 ml co-IP buffer. Beads were denatured with SDS-PAGE loading buffer [Laemmli Sample buffer (Bio-Rad) + β-mercaptoethanol] with heat at 70°C for 10 min and intermittent vortexing. Two immunoprecipitation reactions were performed per animal and were pooled into a single tube without beads to be used for downstream in-gel digestion.

Immunoprecipitated proteins were separated by electrophoresis in Criterion XT MOPS 12% SDS-PAGE reducing gels (Bio-Rad), with subsequent protein visualization by staining with Coomassie blue. Each gel lane was divided into six slices. After de-staining, proteins in the gel slices were reduced with TCEP [tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine hydrochloride] and then alkylated with iodoacetamide before digestion with trypsin (Promega). HPLC-electrospray ionization-tandem mass spectrometry (HPLC-ESI-MS/MS) was accomplished by data-dependent acquisition on a Thermo Fisher Orbitrap Fusion Lumos Tribrid mass spectrometer. Mascot (Matrix Science; London, United Kingdom) was used to search the MS files against the mouse subset of the UniProt database combined with a database of common contaminants. Subset searching of the Mascot data, determination of probabilities of peptide assignments and protein identifications, were accomplished by Scaffold (v 4.8.4, Proteome Software). MS data files for each entire gel lane were combined via the “MudPIT” option. Identification criteria were: minimum of two peptides; 96% peptide threshold; 1% FDR; 99% protein threshold. One vehicle- and one DZP-treated animal were removed from analysis due to insufficient γ2 subunit pulldown relative to all other groups. N = 3 animals per condition were used for downstream analysis. Protein clustering was applied in Scaffold and weighted spectrum values and exclusive unique peptides were exported for manual excel analysis. Student’s t-test analysis was performed using relative fold change (ratio) of DZP compared to vehicle group. In some cases peptides were only detected in vehicle or DZP treated groups, resulting in DZP/V ratio values of zero or undefined error (cannot divide by zero). These were annotated as NF-DZP (not found in DZP samples) or NF-V (not found in vehicle samples) in the tables.

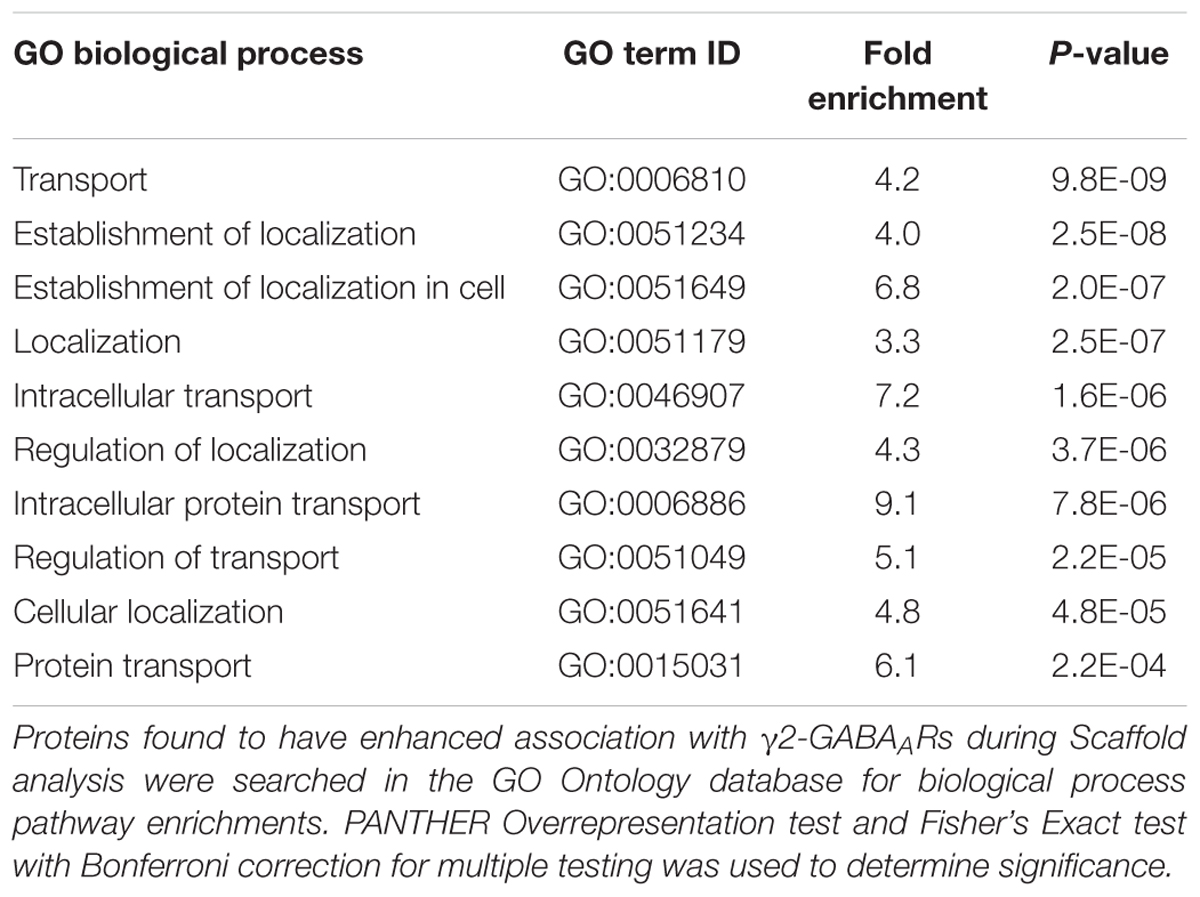

Ingenuity Pathways Analysis (IPA) (Ingenuity Systems) was used for cellular pathway analysis. Relative fold levels of DZP proteins compared to vehicle were used for analysis. To be suitable for IPA analysis, proteins NF-DZP were assigned a value of -1E+99, while proteins NF-V were assigned a value of 1E+99. Significant enrichment in protein networks were calculated by right tailed Fisher’s exact test. Z-score analysis is a statistical measure of an expected relationship direction and observed protein/gene expression to predict pathway activation or inhibition. IPA core analysis was searched to determine direct and indirect relationships within 35 molecules per network and 25 networks per analysis. All data repositories available through IPA were used to determine experimentally observed and highly predicted interactions occurring in mammalian tissue and cell lines. Ratio data were converted to fold change values in IPA, where the negative inverse (-1/x) was taken for values between 0 and 1, while ratio values greater than 1 were not affected. Proteins found to be enhanced in their association with γ2 (Table 1) were searched in the Mus musculus GO Ontology database (released 2018-10-08) for GO biological process and GO molecular function and analyzed by the PANTHER overrepresentation test; significance was determined using Fisher’s Exact with Bonferroni correction for multiple testing.

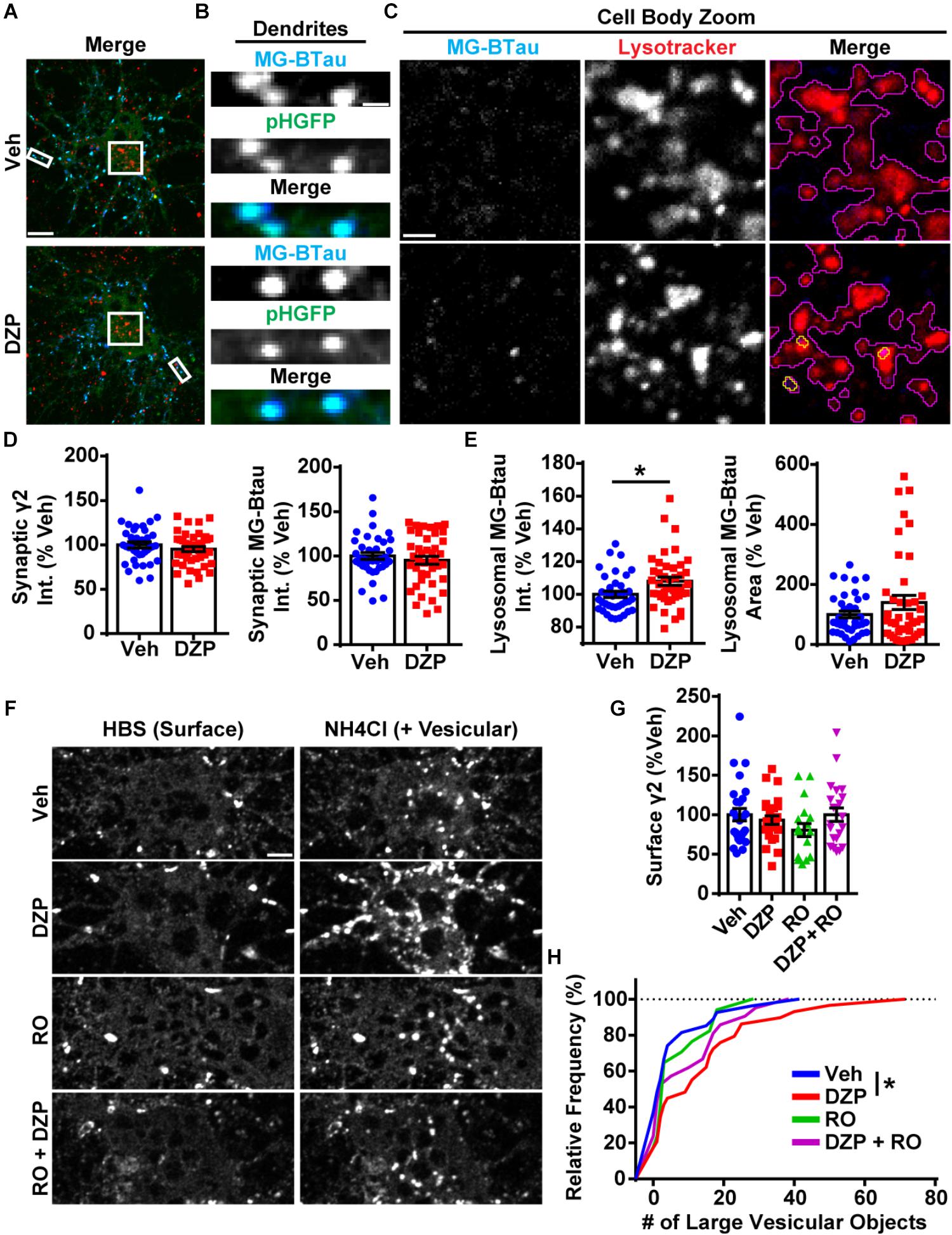

Table 1. Proteins demonstrating increased association with γ2-GABAARs after DZP in vivo by mass spectrometry.

Relevant statistical test information is described in the figure legends or within the individual methods sections. p-values are reported in the results section if significance is between 0.01 and <0.05 or if the data is approaching significance.

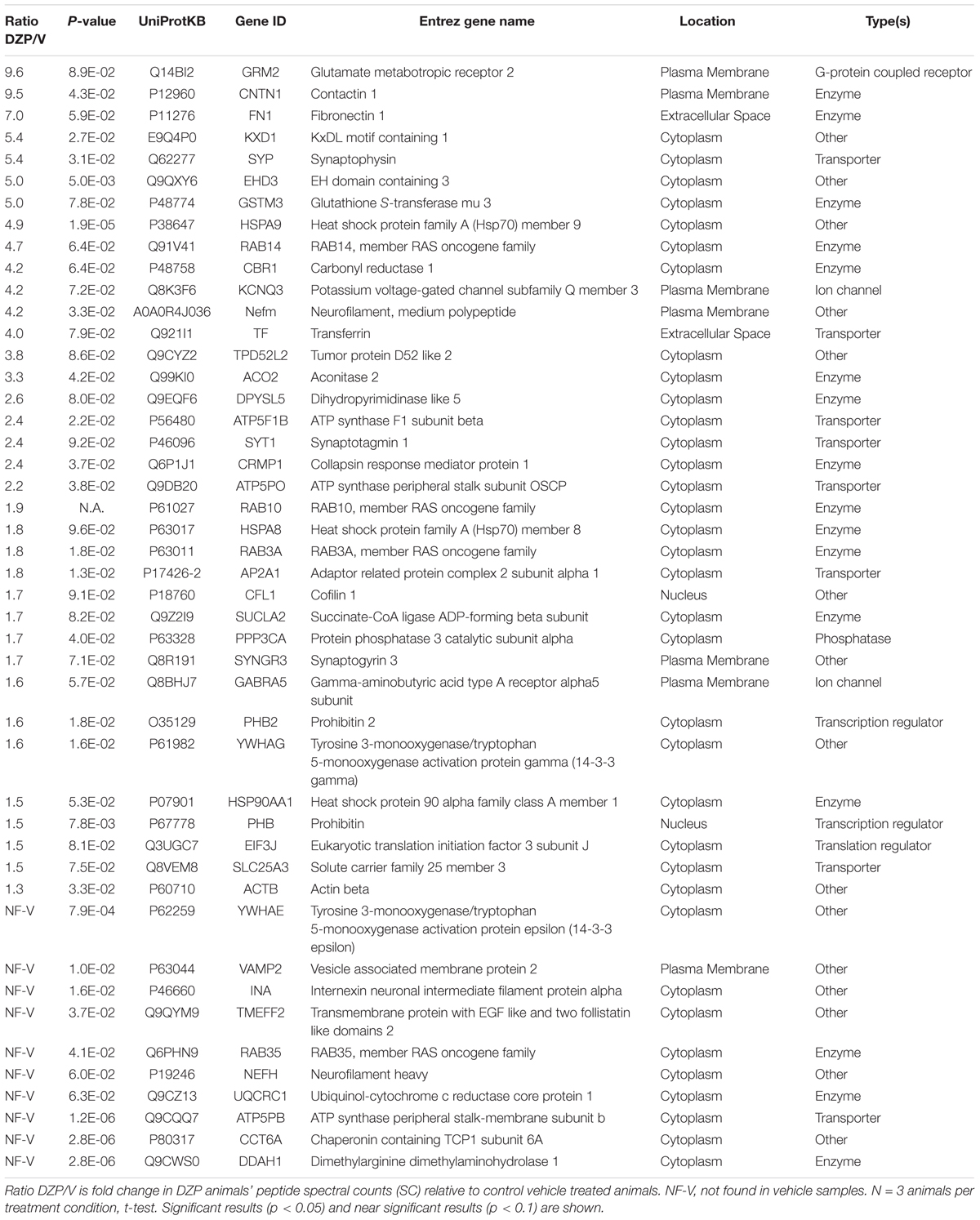

We first examined if DZP exposure reduced surface levels of γ2-GABAARs and altered gephyrin Ser270 phosphorylation in cortical neurons by immunofluorescence (Figure 1A). Cortical neurons were treated for 24 h with vehicle or 1 μM DZP, then immunostained for surface γ2, followed by permeabilization and immunostaining with GAD65 (glutamic acid decarboxylase 65, a marker for presynaptic GABAergic terminals) and the phospho-Ser270 specific gephyrin mAb7a antibody (Kuhse et al., 2012; Kalbouneh et al., 2014). Image analysis identified no sizable change in surface synaptic (91.6 ± 5.3%) or extrasynaptic (93.3 ± 3.8%) γ2 intensity in DZP treated neurons relative to control, but DZP induced a significant 18.9 ± 7.4% (p = 0.033) increase in synaptic phospho-gephyrin (Figure 1B). No change in extrasynaptic phosphorylated Ser270 gephyrin was measured. We repeated this DZP treatment and examined total and phospho-gephyrin levels in dendrites (Figure 1C). Again DZP significantly enhanced phospho-Ser270 gephyrin compared to vehicle (132 ± 12%; p = 0.013), while a decrease in overall gephyrin levels was found (69.7 ± 5.4%) (Figure 1D). Accordingly, the mean ratio of phospho/total gephyrin was 78.1 ± 21% higher following DZP (Figure 1D). Complimentary biochemical studies using membrane fractionation were used to compare cytosolic, membrane, and total protein pools in cortical neurons. In agreement with immunofluorescence data, membrane levels of γ2 (0.929 ± 0.06) were not reduced after 1 μM DZP, although the total pool of γ2 was diminished (0.793 ± 0.07) (Figures 2A,B) compared to vehicle. Cytosolic levels of γ2 (1.03 ± 0.06) were also unchanged. Comparatively, DZP reduced full-length gephyrin in every compartment measured relative to control (cytosol: 0.871 ± 0.03; membrane: 0.722 ± 0.06, total: 0.695 ± 0.05). We confirmed the integrity of our fractions using cytosolic and membrane specific markers (Supplementary Figure S2).

Figure 1. DZP downregulates gephyrin independent of γ2 surface levels. (A) Cortical neurons were treated for 24 h with vehicle or 1 μM DZP, then immunostained for surface γ2 GABAAR (green), followed by permeabilization and immunostaining for (P)Ser270 gephyrin (red), and GAD65 (blue). Panels below show enlargements of GABAAR synapses on dendrites. (B) Dendrite surface synaptic and extrasynaptic γ2 levels are not significantly altered by DZP. Synaptic phospho-gephyrin was enhanced in response to DZP (n = 69–74 neurons; 4 independent cultures). (C) Neurons were treated as in (A) followed by antibody staining for total gephyrin (green) and (P)Ser270 gephyrin (red). Panels below show enlargements of dendrite region. (D) The dendritic pool of gephyrin was decreased, while (P)Ser270 gephyrin levels were augmented, resulting in a dramatic increase in the ratio of phosphorylated gephyrin to total gephyrin (n = 52–59 neurons; 3 independent cultures). Int., fluorescence intensity. Image scale bars: main panels = 5 μm, enlargements = 1 μm. ∗p ≤ 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001, Student’s t-test; error bars ± s.e.m.

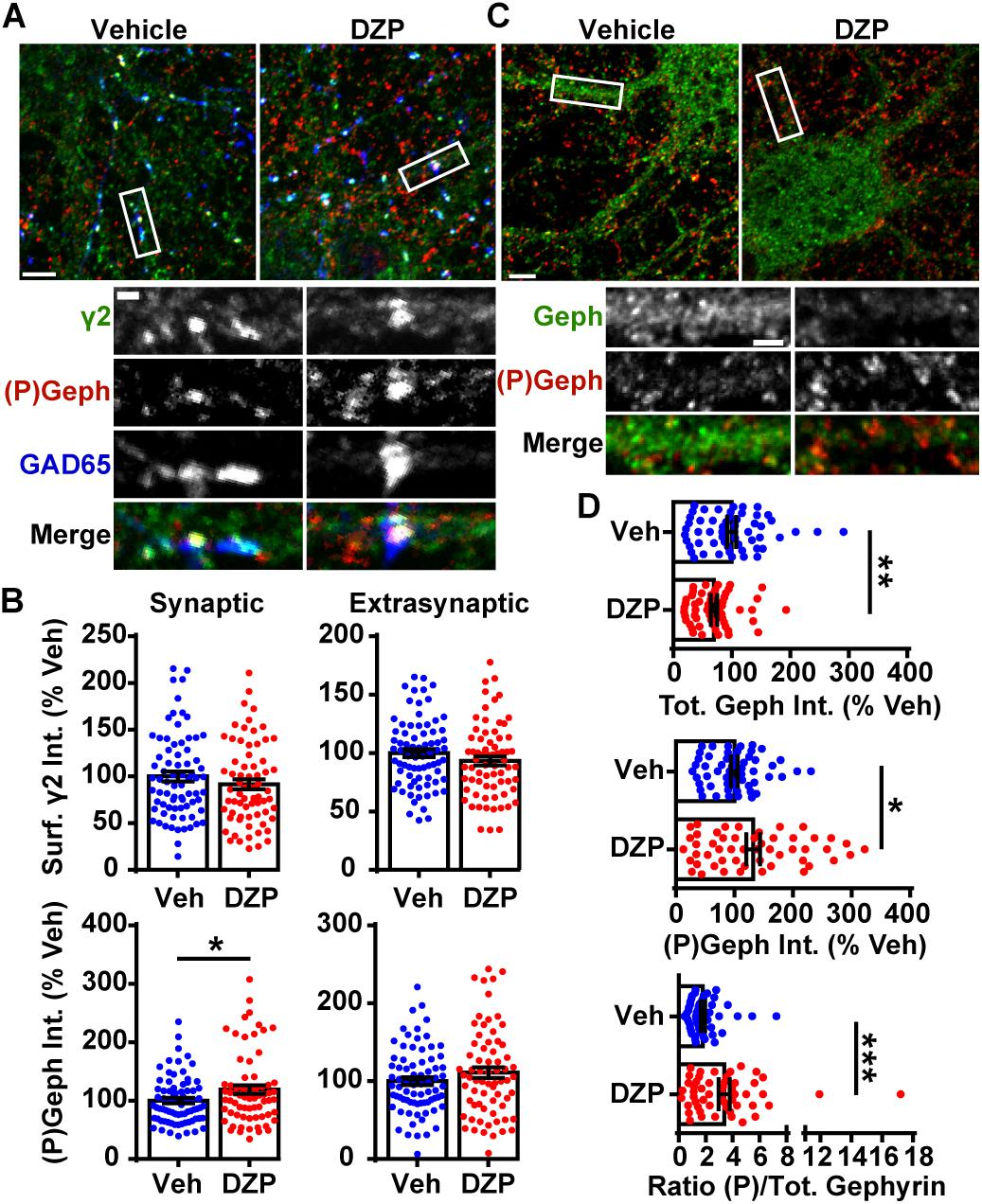

Figure 2. DZP induces degradation of γ2 and gephyrin in vitro and in vivo. (A) Cortical neurons exposed to 1 μM DZP or vehicle for 24 h were subjected to membrane fraction and western blot analysis. Full Geph = full-length gephyrin. (B) Total γ2 subunit and cytosolic, membrane, and total gephyrin were significantly reduced after DZP (n = 7 independent cultures). (C) Quantitative RT-PCR revealed no change in γ2 subunit, β3 subunit or gephyrin mRNA expression following 24 h DZP in vitro (n = 5 independent cultures). (D) GFP-ubiquitin transfected neurons were treated with vehicle or DZP for 12 h. Lysates were immunoprecipitated with control IgG or γ2 antibody, followed by blotting with anti-GFP, γ2 and GAPDH. (E) DZP treatment increased the levels of γ2 ubiquitin conjugates and decreased γ2 total levels. (F,G) DZP treatment enhanced the ratio of cleaved gephyrin fragments/full length gephyrin (n = 7 biological replicates/dishes from 4 independent cultures). Full, full-length gephyrin; Cleav, cleaved gephyrin. (H) Western blots of cortical tissue collected from mice 12 h after a single IP injection of 10 mg/kg DZP or vehicle. (I) γ2 subunit and full-length gephyrin levels are significantly reduced in DZP-treated animals (6–7 mice per condition). [∗p ≤ 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, paired t-test (B,E), Student’s t-test (C,G,I); error bars ± s.e.m].

Next we assessed if the decrease in gephyrin and γ2 total levels at 24 h was a result of altered gene expression. qRT-PCR experiments revealed no difference in gephyrin (p = 0.206), γ2, or control GABAAR β3 subunit mRNA levels between vehicle and DZP treated neurons (Figure 2C). To determine if post-translational modification of γ2 also occurs coincident with decreased γ2 protein levels, we examined ubiquitination of γ2 in response to DZP exposure. We reasoned that changes in ubiquitination of γ2 would likely precede the loss of total γ2 seen at 24 h (Figures 2A,B). GFP-ubiquitin transfected cortical neurons were treated with vehicle or 1 μM DZP for 12 h. Neurons were lysed under denaturing conditions to isolate the γ2 subunit from the receptor complex (Supplementary Figure S3). Immunoprecipitation of the γ2 subunit revealed a 2.13-fold increase (p = 0.015) in ubiquitination in DZP treated neurons relative to vehicle (Figures 2D,E). Furthermore, just as observed with 24 h DZP treatment, a reduced total pool of γ2 was also found at 12 h (p = 0.020) (Figures 2D,E). Notably, this is the first demonstration of endogenous γ2 ubiquitination occurring in neurons (previous findings were of recombinant receptors in HEK cells) (Arancibia-Carcamo et al., 2009; Jin et al., 2014). To investigate mechanisms underlying reduced full-length gephyrin levels, we examined gephyrin cleavage. Gephyrin is degraded post-translationally by the protease calpain-1 (Tyagarajan et al., 2013; Costa et al., 2015; Kumar et al., 2017), and gephyrin Ser270 phosphorylation promotes cleavage by calpain-1 (Tyagarajan et al., 2013). Consistent with the enhanced gephyrin Ser270 phosphorylation (Figure 1) and reduced full-length levels (Figures 1, 2) we found a significant increase in the ratio of cleaved/full length gephyrin after 24 h DZP in vitro (Figures 2F,G). We confirmed the identity of the gephyrin cleavage product using a well-characterized glutamate stimulation protocol that induces gephyrin cleavage in cultured neurons (Costa et al., 2015; Kumar et al., 2017), a process blocked by calpain-1 inhibition (Supplementary Figure S4).

Finally, we wanted to determine if similar mechanisms occur in vivo following DZP treatment. Prior publications show that BZDs and metabolites are not present 24 h post-injection due to rapid drug metabolism in rodents (Yoong et al., 1986; Xie and Tietz, 1992; Van Sickle et al., 2004; Markowitz et al., 2010). Furthermore, BZD uncoupling does not persist 24 h after a single dose (15 mg/kg) or 2 weeks daily DZP treatment, whereas uncoupling can be seen 12 h after a single injection, indicating this is the appropriate time point for measuring in vivo loss of γ2-GABAAR function (Holt et al., 1999). Accordingly, mice were given a single intraperitoneal (IP) injection of 10 mg/kg DZP or vehicle control, and cortex tissues were harvested 12 h later. We found DZP significantly reduced the total pool of γ2 (87.3 ± 3.0%) and full-length gephyrin (73.9 ± 9.1%; p = 0.046) relative to vehicle treated mice at 12 h post injection (Figures 2H,I). These findings indicate both BZD-sensitive GABAARs and full-length gephyrin are downregulated by post-translational mechanisms after initial DZP treatment in vitro and in vivo to temper potentiation of GABAAR function.

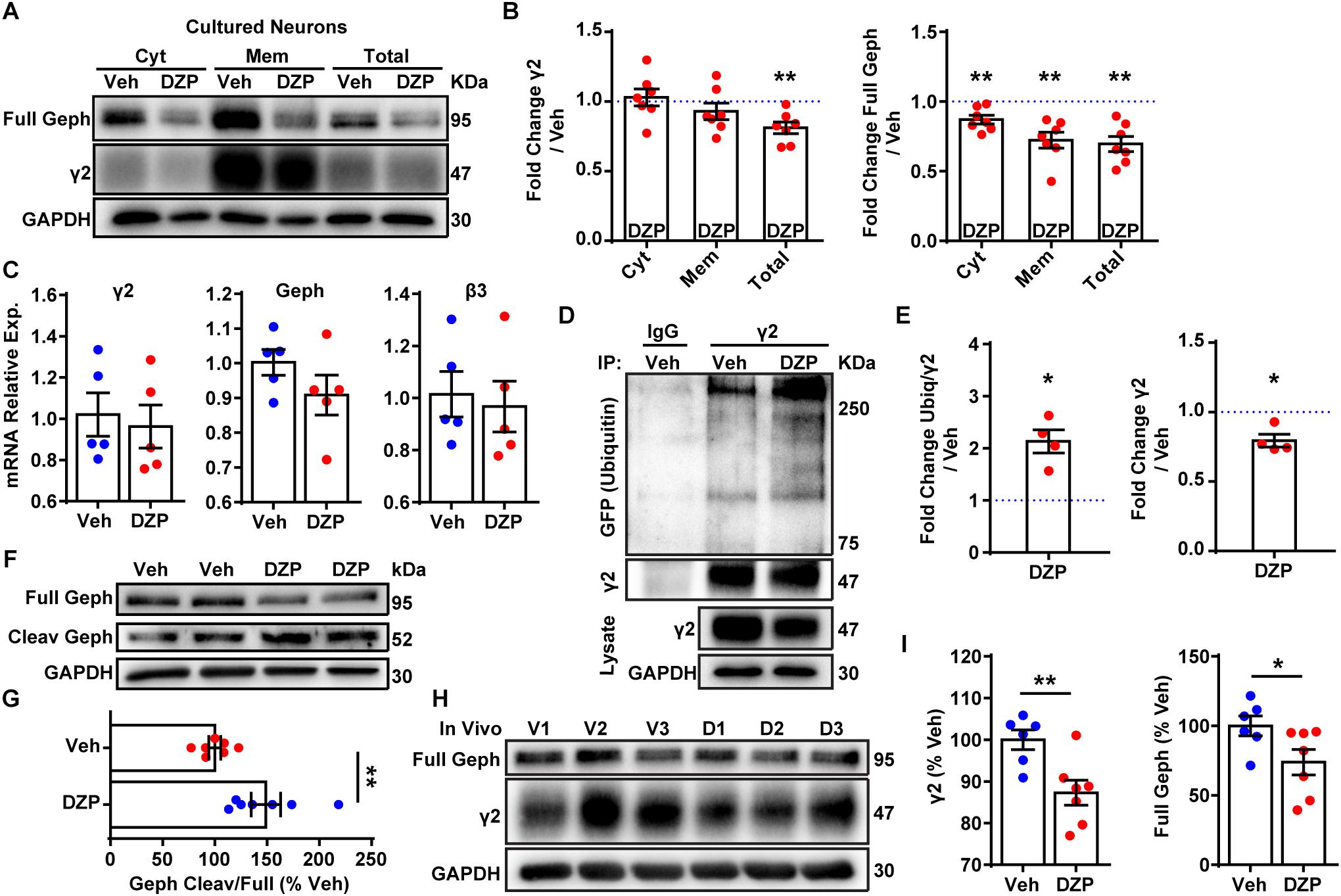

We then investigated if surface γ2-containing GABAARs are more frequently targeted to lysosomes after DZP exposure by live-imaging. For these experiments we used our recently characterized optical sensor for synaptic GABAAR (γ2pHFAP). This dual reporter is composed of a γ2 subunit tagged with an N terminal pH-sensitive GFP, myc, and the fluorogen-activating peptide DL5 (Lorenz-Guertin et al., 2017). The pH-sensitive GFP tag selectively identifies cell surface GABAARs and the DL5 FAP binds malachite green (MG) dye derivatives including MG-BTau (Szent-Gyorgyi et al., 2008, 2013; Pratt et al., 2017). MG-BTau is cell impermeable and non-fluorescent until bound by DL5. Upon binding, MG-BTau fluoresces in the far red spectral region (∼670 nM). This FAP-dye system allows for selective labeling of surface γ2-containing GABAARs which can then be tracked through various phases of trafficking (Lorenz-Guertin et al., 2017). As previously shown, γ2pHFAP GABAARs are expressed on the neuronal surface, form synaptic clusters, do not perturb neuronal development and show equivalent functional responsiveness to GABA and DZP both in the absence and presence of MG dyes (Lorenz-Guertin et al., 2017). We transfected neurons with γ2pHFAP and treated them with DZP for 8–16 h. Neurons were then pulse-labeled with 100 nM MG-BTau dye and returned to conditioned media at 37°C ± DZP for 1 h. The lysosomal inhibitor leupeptin (200 μM) and the lysosomal specific dye, Lysotracker (50 nM), were added after 30 min. At the end of the incubation, neurons were washed in 4°C saline to inhibit trafficking and immediately used for live-imaging experiments. Representative images demonstrate MG-BTau labeled γ2pHFAP-GABAARs localized on the cell surface (Figure 3A) and at synaptic clusters on dendrites (Figure 3B) based on colocalization with surface specific pHGFP signal. MG-BTau further reveals internalized receptors at lysosomes (Figure 3C). Image quantification showed synaptic γ2-GABAAR intensity remained largely unchanged (Figure 3D). Importantly, we found a significant 8.0 ± 2.5% (p = 0.015) enhancement in the mean intensity of GABAARs labeled with MG-BTau at lysosomes following DZP (Figure 3E). The area of GABAARs colocalized at lysosomes trended toward an increase in DZP treated cells (140.2 ± 23.6%; p = 0.144) but did not reach significance.

Figure 3. Lysosomal targeting and vesicular accumulation of γ2-GABAARs in response to DZP. (A) γ2pHFAP neurons were pretreated for 12–18 h with 1 μM DZP, then pulse-labeled with 100 nM MG-BTau dye for 2 min, and returned to conditioned media at 37°C ± DZP for 1 h. 50 nM Lysotracker dye was added at the 30 min mark to identify lysosomes. MG-BTau = blue; pHGFP = green; Lysotracker = red (n = 37–42 neurons; 5 independent cultures). (B) Dendrite zoom images show MG-BTau labeling at γ2pHFAP synapses. (C) Cell body zoom images highlighting colocalization of MG-BTau labeled GABAARs (yellow trace) at lysosomes (purple trace). (D) Dendrite pHGFP and MG-BTau measurements reveal surface synaptic γ2-GABAAR levels are not altered by DZP. (E) The pool of internalized MG-BTau GABAARs colocalized at lysosomes was enhanced in DZP treated neurons as measured by intensity (∗p ≤ 0.05, Student’s t-test; error bars ± s.e.m). (F) Neurons treated 20–28 h with vehicle or DZP. The DZP site antagonist Ro 15–1788 (5 μM) was added 1–2 h prior to imaging to inhibit DZP binding at GABAARs. Neurons were first imaged in HBS, and then perfused with NH4Cl (pH 7.4) to reveal intracellular γ2pHFAP receptors. DZP treated neurons accumulated more γ2-GABAARs in large vesicular structures compared to vehicle (n = 20–27 neurons; 3–4 independent cultures). (G) Surface intensity of γ2pHFAP was not different between treatments (one-way ANOVA; error bars ± s.e.m). (H) DZP-treated neurons more frequently demonstrated accumulation of γ2pHFAP in large vesicles (∗p ≤ 0.05 Kolmogorov–Smirnov statistical test). Int., fluorescence intensity. Scale bars in μm: (A) = 10; (B) = 1; (C) = 2, (F) = 5.

We complemented these lysosomal targeting studies with an NH4Cl live-imaging approach that allows us to compare the ratio of cell surface vs. intracellular GABAARs in living neurons. γ2pHFAP expressing neurons were treated with vehicle or DZP for 24 h. Additional control groups included the BZD antagonist Ro 15-1788 (1–2 h) to reverse the effects of DZP. Neurons were actively perfused with HEPES buffered saline (HBS) treatment and an initial image was taken of surface pHGFP receptor signal (Figure 3F). Neurons were then exposed to pH 7.4 NH4Cl solution to neutralize the pH gradient of all intracellular membrane compartments, revealing internal pools of γ2 containing GABAARs. Analysis revealed no change in surface γ2 levels between treatments (Figure 3G) consistent with Figures 1, 2. However, the number of large intracellular vesicles (circular area ∼0.75 μm) containing receptors was significantly enhanced (p = 0.047) (Figure 3H), consistent with increased localization in intracellular vesicles. Ro 15-1788 and DZP + Ro 15-1788 treated neurons were not significantly different from vehicle. Overall, these findings suggest γ2-GABAAR ubiquitination, intracellular accumulation, lysosomal targeting and degradation are part of the adaptive response to DZP.

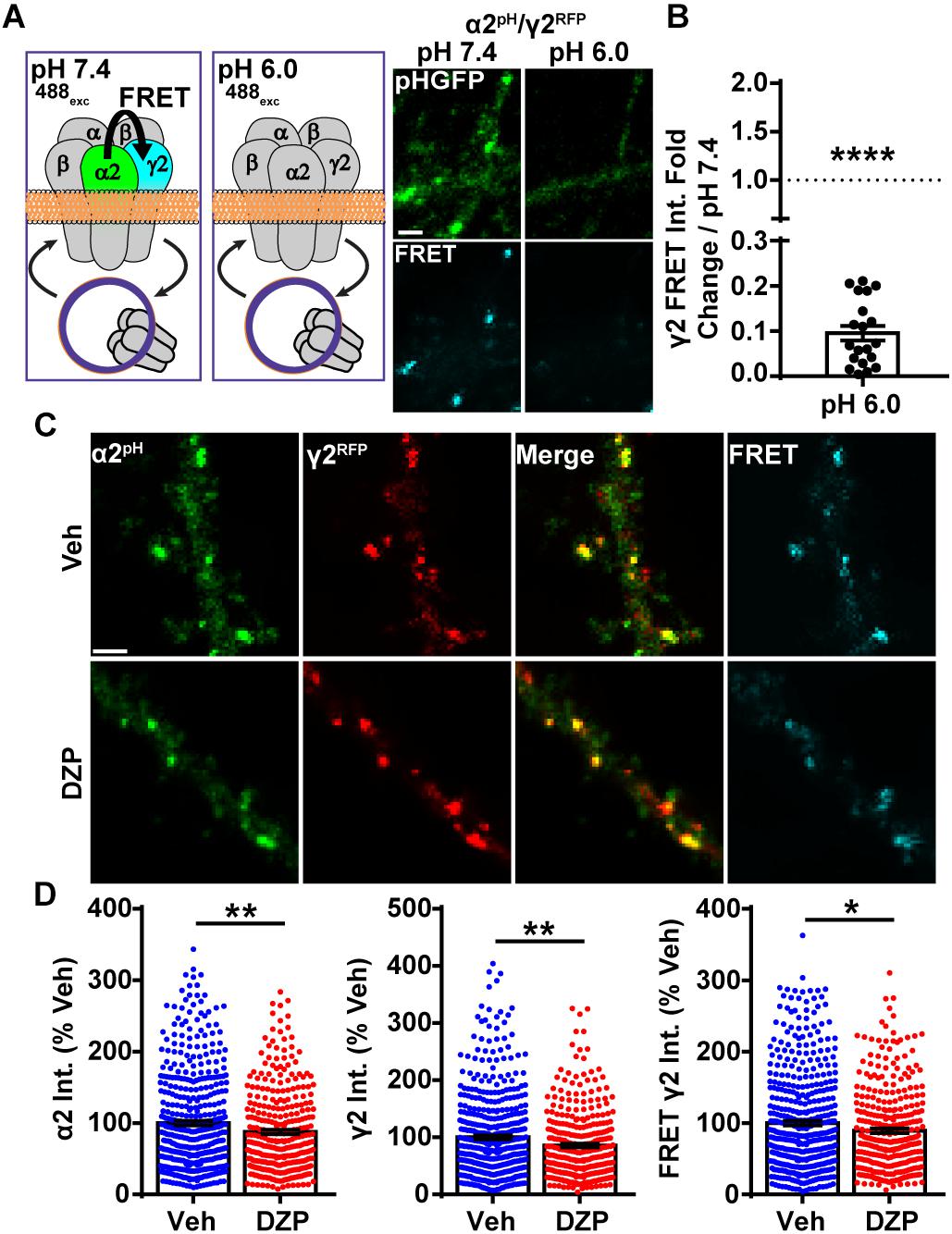

Despite the increase in ubiquitination and lysosomal targeting of γ2-GABAARs after DZP, we did not detect decreased overall surface or synaptically localized γ2 levels. This suggested two possibilities, one being that a slight decrease in surface γ2-GABAARs could be challenging to detect with current methods (DZP treated cells total γ2 levels 80% of control in cultured cortical neurons; 85% in vivo). Alternatively, there could be an increase in γ2 subunit assembly with BZD-insensitive α subunits (γ2α4β) (Wafford et al., 1996) with a concomitant reduction in surface levels of BZD-sensitive receptors (γ2α1/2/3/5β). Our previous work showed 24 h BZD exposure in hippocampal neurons causes decreased total and surface levels of the α2 GABAAR subunit via lysosomal mediated degradation, without any changes in receptor insertion or removal rate (Jacob et al., 2012). To determine if α2/γ2 GABAARs are specifically decreased by DZP treatment, we developed an intermolecular FRET assay, using pH-sensitive GFP tagged α2pH (Tretter et al., 2008) as a donor fluorophore and a red fluorescent protein (RFP) tagged γ2 subunit (γ2RFP) as an acceptor. FRET is an accurate measurement of molecular proximity at distances of 10–100 Å and is highly efficient if donor and acceptor are within the Förster radius, typically 30–60 Å (3–6 nm), with the efficiency of FRET being dependent on the inverse sixth power of intermolecular separation (Förster, 1965). Synaptic GABAARs exist as five subunits assembled in γ2-α-β-α-β order forming a heteropentameric ion channel (Figure 4A). We first expressed α2pH and γ2RFP in neurons and examined their ability to participate in intermolecular FRET. Photobleaching of the acceptor γ2RFP channel enhanced donor α2pH signal (Supplementary Figure S5), confirming energy transfer from α2pH to γ2RFP. Next, we confirmed measurable FRET only occurs between α2pH/γ2RFP in surface GABAAR at synaptic sites; FRET was blocked with quenching of donor α2pH when the extracellular pH was reduced from 7.4 to 6.0 (Figures 4A,B). Following FRET assay validation, α2pH/γ2RFP GABAAR expressing neurons were treated for 24 h with vehicle or DZP and examined for total synaptic α2pH and γ2RFP fluorescence as well as the γ2 FRET signal (Figure 4C). These studies identified a DZP-induced reduction in synaptic α2 (-12.6%), synaptic γ2 (-14.3%) and diminished association of α2 with γ2 in synaptic GABAARs as measured by decreased FRET γ2 signal (-10.6%; p = 0.024) (Figure 4D). In summary, this sensitive FRET method indicates that cortical neurons show a similar susceptibility for α2 subunit downregulation by BZD treatment as seen in hippocampal neurons (Jacob et al., 2012). Furthermore it identifies a DZP-induced decrease in a specific pool of surface synaptic BZD-sensitive γ2-GABAAR.

Figure 4. Intermolecular FRET reveals decreased dendritic synaptic α2/γ2 surface GABAARs after DZP. (A) Diagram and time-series images of cortical neurons expressing donor α2pH (green) and acceptor γ2RFP during imaging at pH 7.4 and pH 6.0. Surface α2pH (green) signal and intermolecular FRET (teal) between α2/γ2 subunits occurs at pH 7.4, but is eliminated by brief wash with pH 6.0 extracellular saline and quenching of the α2pH donor pHGFP fluorescence. (B) Quantification of relative FRET at pH 7.4 and pH 6.0 (n = 20 synapses). (C) Neurons α2pH (green) and γ2RFP (red) were treated with vehicle or DZP for 20–28 h ± and then subjected to live-imaging. For each cell, an initial image used 488 nm laser excitation to identify surface α2pH and FRET γ2RFP. A second image was taken immediately afterwards to acquire γ2RFP total levels (561 nm laser excitation). Dendritic lengths show multiple synaptic clusters with α2/γ2 surface GABAARs. (D) Synaptic cluster intensity quantification of α2pH, γ2RFP, and FRET γ2RFP (at least 15 synapses per cell; n = 335–483 synapses; 6 independent cultures). Int., fluorescence intensity. Image scale bars = 2 μm [∗p ≤ 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001, paired t-test (B), Student’s t-test (D); error bars ± s.e.m].

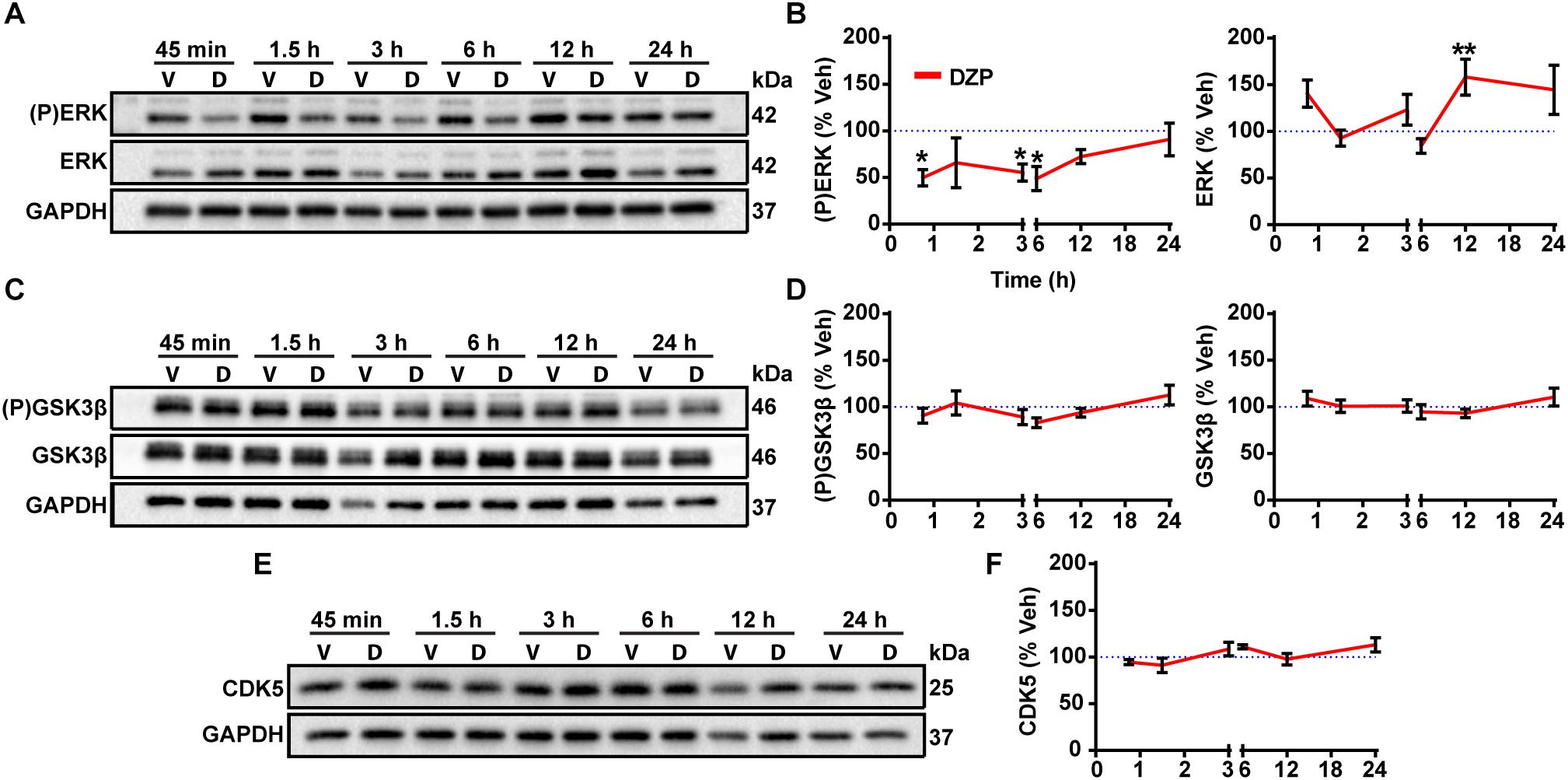

To gain additional mechanistic insight into the molecular mechanisms controlling phosphorylation and degradation of gephyrin observed in Figures 1, 2, we performed a DZP time series experiment to measure changes in expression or activation of the gephyrin regulating kinases ERK, GSK3β, and CDK5. CDK5 and GSK3β phosphorylate gephyrin at the Ser270 site (Tyagarajan et al., 2011; Kalbouneh et al., 2014), while ERK phosphorylates a neighboring Ser268 residue (Tyagarajan et al., 2013). We first measured ERK activation by examining ERK phosphorylation across time points. DZP treatment caused a significant decrease in ERK phosphorylation at 45 min (-50.2%), 3 h (-44.5%) and 6 h (-51.2%), with a recovery in phosphorylation to vehicle levels occurring around 12 and 24 h (Figures 5A,B). Total ERK levels were unchanged after DZP, except for a significant enhancement in expression at the 12 h time point, coinciding with recovery of ERK phosphorylation. We did not detect a change in the phosphorylation or total levels of GSK3β (Figures 5C,D) or expression of CDK5 (Figures 5E,F). This data indicates that kinases involved in gephyrin phosphorylation at Ser270 do not demonstrate global changes after DZP, suggesting that the kinases may be recruited to gephyrin, or that an unknown phosphatase responsible for dephosphorylating Ser270 is inhibited after DZP exposure. Conversely, ERK inactivation by DZP is predicted to decrease phosphorylation of the functionally relevant Ser268 site of gephyrin, which has also been implicated in gephyrin synaptic remodeling (Tyagarajan et al., 2013). Gephyrin point mutant studies suggest reduced phosphorylation at Ser268 coupled with enhanced Ser270 phosphorylation, or the inverse, promotes calpain-1 degradation and scaffold remodeling (Tyagarajan et al., 2013). This data provides evidence that a known kinase pathway responsible for fine-tuning GABAAR synapse dynamics (Brady et al., 2017) and scaffold (Tyagarajan et al., 2013) is robustly inactivated by DZP.

Figure 5. Gephyrin regulating kinases following DZP treatment. DIV 16 cortical neurons were treated with vehicle (V) or DZP (D) at multiple time points. Known kinase regulators of gephyrin synaptic clustering were tested for total protein levels and activation status with phospho-specific antibodies as indicated. (P)ERK and total ERK (A,B), (P)GSK3β and total GSK3β (C,D) and CDK5 (E,F) western blot and quantification (n = 4 independent cultures). DZP strongly inhibited ERK phosphorylation across multiple time points while GSK3β activation and total levels did not change. CDK5 total levels were also unchanged by DZP treatment. (∗p ≤ 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, Two-way ANOVA followed by Sidak’s multiple comparisons test; error bars ± s.e.m).

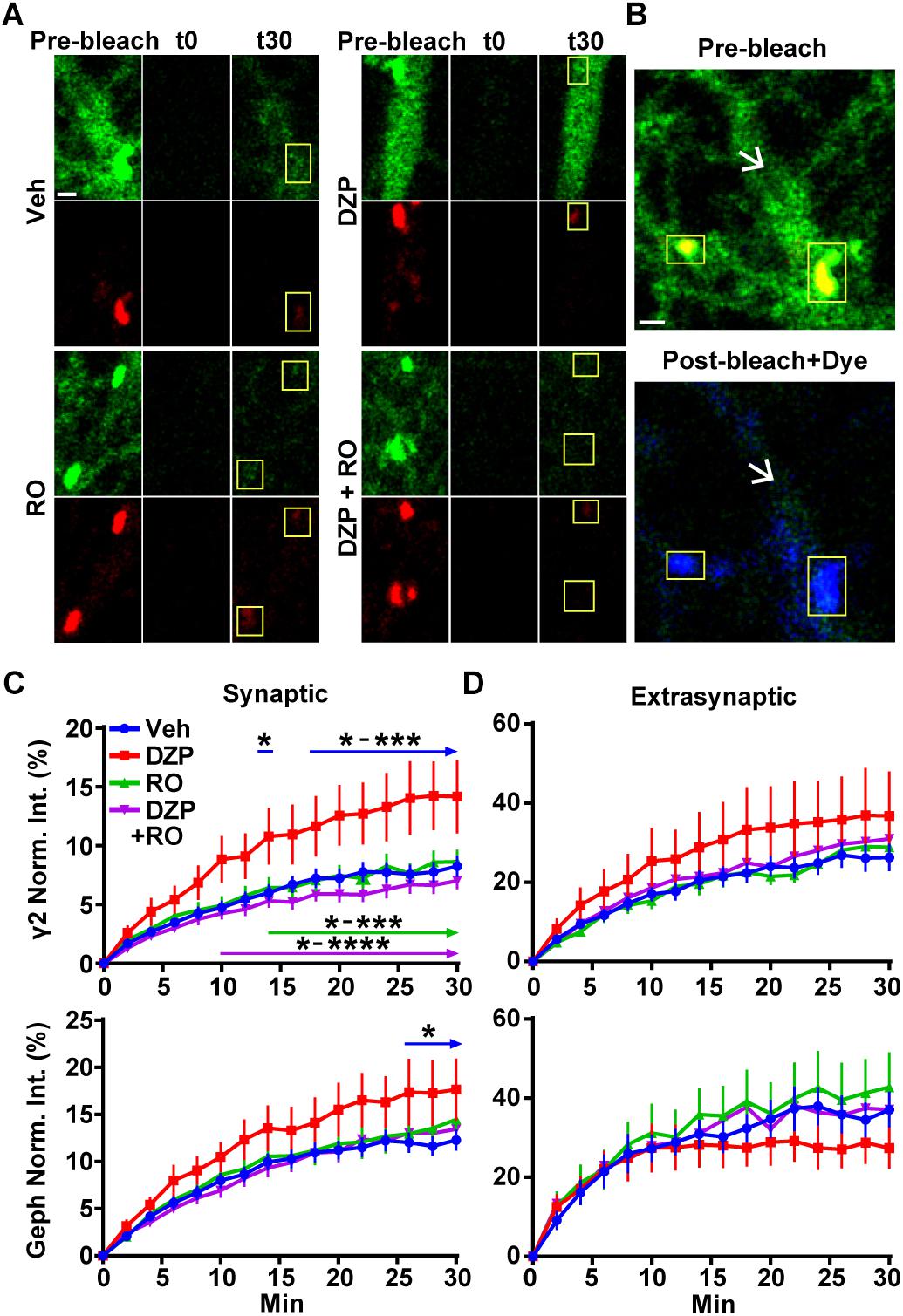

We previously found 24 h BZD exposure reduces the amplitude of miniature inhibitory postsynaptic currents (mIPSCs) (Jacob et al., 2012), suggesting changes in synaptic GABAAR function. Having identified both reductions in full-length gephyrin (Figures 1, 2) and BZD sensitive GABAARs (Figures 2, 4), we next tested if DZP treatment altered the synaptic retention properties of gephyrin and/or GABAARs. Neurons expressing γ2pHFAP and RFP-gephyrin were used for live-imaging fluorescence recovery after photobleaching experiments (FRAP) to measure synaptic and extrasynaptic exchange following exposure to vehicle, 1 μm DZP, 5 μm Ro 15-1788, or DZP + Ro 15-1788. After an initial image was taken, dendrites were photobleached, and signal recovery was measured every 2 min over 30 min at synaptic sites and extrasynaptic regions (Figure 6A synapses panel; Figure 6B larger dendritic region with white arrows denoting extrasynaptic region). MG-BTau dye was added directly after the photobleaching step to immediately re-identify the photobleached surface synaptic GABAARs, and improve spatial measurements (Figure 6B). These experiments revealed synaptic γ2 turnover rates were nearly doubled in DZP treated neurons, a process reversed by Ro 15-1788 co-treatment (Figure 6C). DZP also accelerated gephyrin synaptic exchange rates compared to vehicle, with Ro 15-1788 co-treatment restoring exchange to control levels. No significant correlation was found between cluster area measured and fluorescence recovery rates of γ2 and gephyrin across all conditions, suggesting synaptic exchange rate is independent of cluster size (Supplementary Figure S6). Moreover, no statistical difference was found in γ2 or gephyrin extrasynaptic exchange rates (Figure 6D). These findings suggest concurrent reduction of gephyrin and GABAAR synaptic confinement is a compensatory response to mitigate prolonged DZP potentiation of GABAARs.

Figure 6. Prolonged DZP exposure accelerates γ2 GABAAR and gephyrin synaptic exchange. (A) Neurons expressing γ2pHFAP GABAAR (green) and RFP-gephyrin (red) were treated with vehicle or DZP for 20–28 h ± Ro 15-1788 for the last 1–2 h. Neurons were imaged at 37°C in constant presence of treatment. Initial image of dendrites taken prior to photobleaching (Pre-bleach), then imaged post-bleach (t0) every 2 min for 30 min. Images of dendritic regions show synaptic cluster sites (yellow boxes) and extrasynaptic regions. (B) 10 nM MG-BTau dye (blue) was added immediately after bleaching events in (A) to resolve bleached γ2pHFAP GABAARs and provide spatial accuracy for time series measurements. Panels show enlargement of vehicle dendritic regions identified in (A). Yellow boxes indicate synaptic clusters and arrows indicate extrasynaptic region seen by pHGFP fluorescence in pre-bleach (green) followed by post-bleach labeling with Mg-Btau (blue). (C,D) Fluorescence recovery of γ2 GABAAR and gephyrin measured at synaptic sites and extrasynaptic sites from (A). Synapse = γ2pHFAP cluster colocalized with gephyrin cluster. Int., fluorescence intensity. Image scale bars = 1 μm (∗p ≤ 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001, ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001, two-way ANOVA; Tukey’s multiple comparisons test; 4–8 synapses and one 10 μm extrasynaptic region per cell; n = 51–56 synapses from 16 neurons per treatment; 4 independent cultures; error bars ± s.e.m).

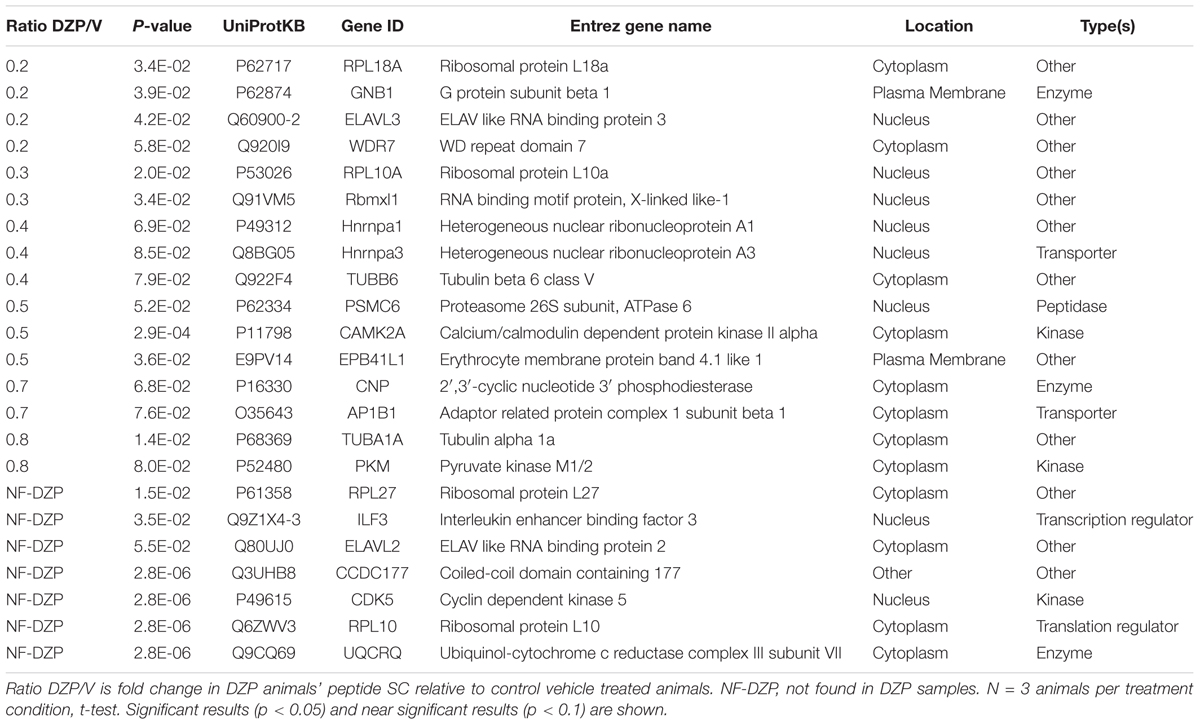

We sought to observe DZP-induced changes in receptor trafficking in vivo. As an orthogonal approach, we utilized label-free quantitative proteomics to measure changes in the quantities of proteins associated with γ2-GABAARs in the cortex of mice after DZP. Cortical tissue was collected from DZP- or vehicle-treated mice 12 h post injection, lysed, and immunoprecipitated with anti-γ2 subunit antibody or IgG control. Following label-free mass spectrometry analysis, spectrum counts were used to assess relative abundance of γ2-associated proteins. A total of 395 proteins were identified using our inclusion criteria: minimum of two peptides; identified in at least three samples overall or in two of three samples in a specific treatment group; demonstrated at least 3:1 enrichment over IgG control across at least three samples overall (Supplementary Dataset 1). The relative abundance of γ2-GABAAR associated proteins in the DZP group compared to vehicle was used to determine which proteins were increased (Table 1) or decreased (Table 2). As a result we identified 46 proteins with elevated levels of interaction with γ2-GABAARs, including 10 proteins that were only found in the DZP treated group (Table 1, not found in vehicle samples, NF-V). Notably, we found a significant (p < 0.05) increase in γ2 association with 14-3-3 protein family members tyrosine 3-monooxygenase/tryptophan 5-monooxygenase activation protein gamma (also known as 14-3-3γ) and tyrosine 3-monooxygenase/tryptophan 5-monooxygenase activation protein epsilon (also known as 14-3-3𝜀), the phosphatase protein phosphatase 3 catalytic subunit alpha (also known as calcineurin/PPP3CA) and a near significant increase in the GABAAR α5 subunit (p = 0.057), suggesting DZP induced changes in GABAAR surface trafficking (Qian et al., 2012; Nakamura T. et al., 2016), synaptic retention (Bannai et al., 2009, 2015; Muir et al., 2010; Niwa et al., 2012; Eckel et al., 2015), and receptor composition (van Rijnsoever et al., 2004). In contrast, 23 proteins were found to co-immunoprecipitate with γ2 less in DZP animals relative to control, seven of which were only present in the vehicle treatment group (Table 2, not found in DZP, NF-DZP). Interestingly, the calcium-sensitive kinase CaMKIIα, which can regulate GABAAR membrane insertion, synaptic retention and drug binding properties (26, 70–72), was found to be significantly decreased in interaction with γ2-GABAAR following DZP injection in vivo.

Table 2. Proteins demonstrating decreased association with γ2-GABAARs after DZP in vivo by mass spectrometry.

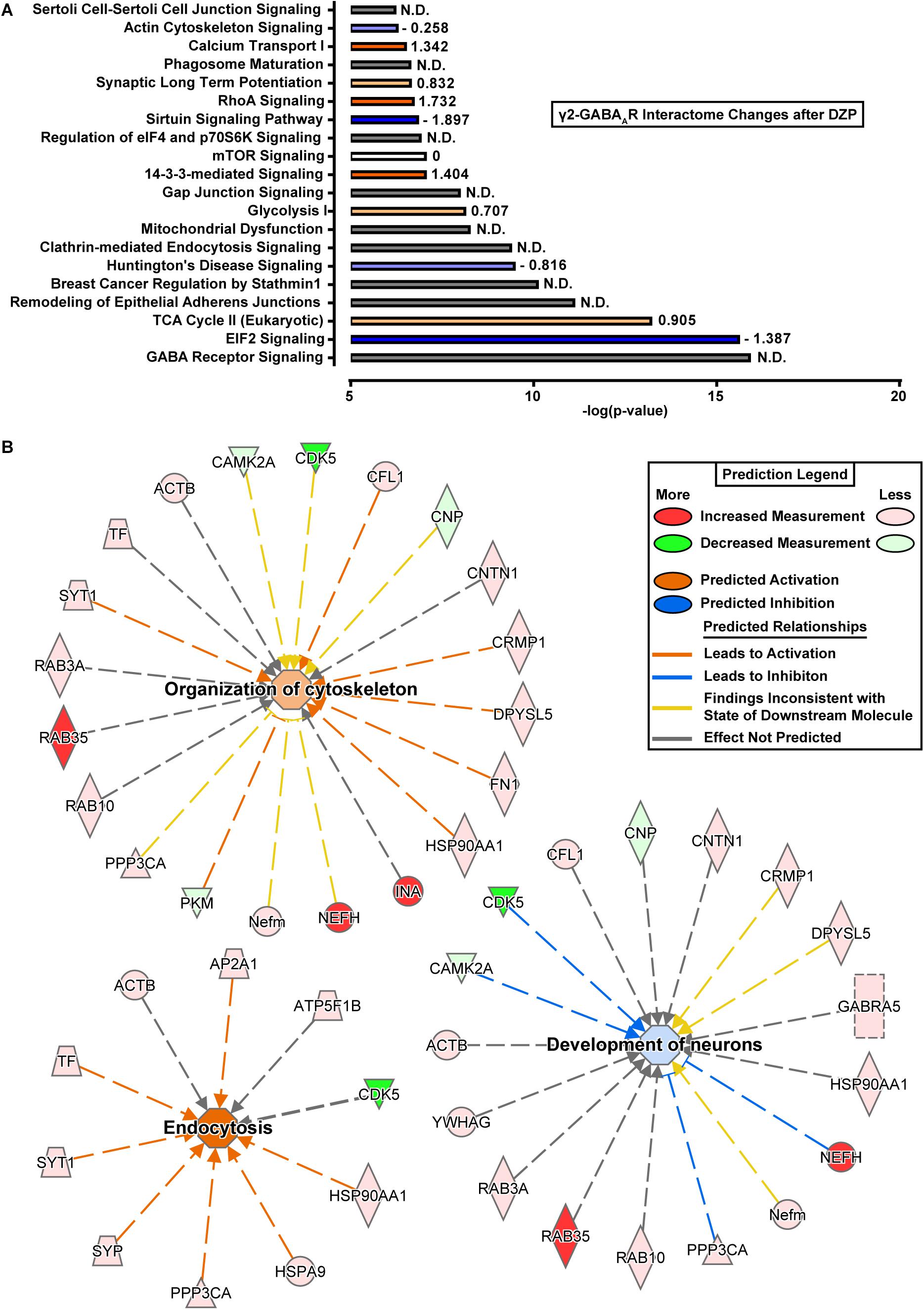

To better understand the consequences of the DZP-induced shift in the γ2-GABAAR protein interaction network, protein fold change data was subjected to core Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (IPA). Top enriched canonical pathways with -log(p-value) > 6.2 are shown in Figure 7. Notably, GABA receptor signaling pathways were highly enriched, as expected, although IPA was unable to determine pathway activation status by z-score analysis. γ2-GABAAR association with proteins involved in 14-3-3 mediated signaling and RhoA signaling pathways were greatly increased after DZP (Figure 7A, orange), while interaction with proteins involved in EIF2 signaling and sirtuin signaling pathways were reduced (Figure 7A, blue) relative to vehicle.

Figure 7. Ingenuity pathway analysis reveals shifts in protein interaction networks following DZP exposure. (A) Canonical pathways found to be enriched with γ2-GABAARs and differentially expressed following DZP administration in vivo. Enriched pathways with –log(p-value) greater than 6.2 were considered as calculated by Fisher’s exact test right-tailed. Values to right of bars represent pathway activation z-score. Positive z-score represents predicted upregulation of a pathway (orange), negative z-score predicts inhibition (blue), z-score = 0 represents no change in pathway (white), while not determined (N.D.) conveys the analysis program was unable to determine a significant change (gray). Intensity of color represents size of z-score value. (B) Functional network association of select pathways when using proteins which were found to be increased or decreased with a p < 0.1. Major functional pathways altered by DZP include endocytosis (z-score = 2.626), organization of cytoskeleton (z-score = 0.672), and development of neurons (z-score = –0.293). Significant protein changes (p < 0.05) conserved between two or more pathways include decreased γ2-GABAAR association with CAMKIIα and CDK5 and enhanced association with calcineurin/PPP3CA, the intracellular trafficking protein RAB35 and the cytoskeletal protein NEFH (also known as heavy neurofilament protein). Red = increased measurement, green = decreased measurement, orange = activation of pathway, blue = inhibition of pathway, yellow = findings inconsistent with state of downstream molecule, gray = effect not predicted.

We further examined alterations in functional network association relevant to receptor trafficking by checking the predicted activation status of select pathways when only using proteins which were found to be increased or decreased (Tables 1, 2). Figure 7B lists γ2-GABAAR major functional pathways found to be altered by DZP, contributing to processes such as endocytosis (z-score = 2.626), organization of cytoskeleton (z-score = 0.672), and development of neurons (z-score = -0.293). Significant protein changes (p < 0.05) conserved between two or more pathways include decreased γ2-GABAAR association with CAMKIIα and CDK5 and enhanced association with calcineurin/PPP3CA, the intracellular trafficking protein RAB35 and the cytoskeletal protein NEFH (also known as heavy neurofilament protein). As an additional measurement, we performed gene ontology (GO) database analysis of proteins which were found to be increased in DZP treated mice relative to vehicle control (Table 3). GO analysis identified enrichment in γ2 association with proteins involved in intracellular trafficking and cellular localization biological pathways after DZP, consistent with IPA analysis findings. Taken together, these results suggest DZP modifies intracellular and surface trafficking of γ2-GABAARs both in vitro and in vivo.

Table 3. GO analysis reveals enrichment of intracellular trafficking, transport, and protein localization pathways after DZP.

This work identifies key trafficking pathways involved in GABAAR neuroplasticity in response to initial DZP exposure. Using a combination of biochemical and imaging techniques, we identified total γ2 subunit levels are diminished in response to 12–24 h of DZP exposure in vitro and in vivo. Concurrent with the decrease in the overall γ2 pool, we found DZP treatment enhanced ubiquitination of this subunit. Use of an innovative optical sensor for BZD sensitive GABAAR (γ2pHFAP) in combination with MG dye pulse-labeling approaches revealed DZP exposure moderately enhanced targeting of surface γ2-GABAARs to lysosomes. Live-imaging experiments with pH 7.4 NH4Cl revealed increased intracellular receptor pools, providing further evidence that DZP enhances γ2-GABAAR lysosomal accumulation, a response reversed by BZD antagonist Ro 15-1788 treatment. We used novel intersubunit FRET based live-imaging to identify that surface synaptic α2/γ2 GABAARs were specifically decreased after DZP, suggesting these receptor complexes were subjected to ubiquitination, lysosomal targeting, and degradation. In addition to DZP modulation of receptor trafficking, the postsynaptic scaffolding protein gephyrin demonstrated significant plasticity including increased Ser270 phosphorylation and production of gephyrin proteolytic fragments, concurrent with a decrease in total and membrane full-length gephyrin levels and ERK inactivation. Given the fundamental role of gephyrin in scaffolding GABAARs and regulating synaptic confinement, we used simultaneous FRAP live-imaging of receptors and scaffold in neurons to monitor inhibitory synaptic dynamics. We found ∼24 h DZP exposure accelerates both the rate of gephyrin and GABAAR exchange at synapses as shown by enhanced fluorescence recovery rates. Control experiments using the BZD antagonist Ro 15-1788 were able to reverse the DZP induced loss of synaptic confinement, reducing gephyrin and GABAAR mobility back to vehicle levels. Finally, we used label-free quantitative mass spectrometry and bioinformatics to identify key changes in γ2-GABAAR protein association in vivo suggesting alterations in trafficking at the cell surface and intracellularly. Collectively, this work defines a DZP-induced reduction of gephyrin scaffolding coupled with increased synaptic exchange of gephyrin and GABAARs. This dynamic flux of GABAARs between synapses and the extrasynaptic space was associated with enhanced γ2-GABAAR accumulation in intracellular vesicles and γ2-GABAAR subtype specific lysosomal degradation. We propose DZP treatment alters these key intracellular and surface trafficking pathways ultimately diminishing responsiveness to DZP.

Numerous classical studies have examined gene and protein expression adaptations in GABAAR subunits after BZD exposure with minimal agreement that a specific change occurs (Bateson, 2002; Uusi-Oukari and Korpi, 2010; Vinkers and Olivier, 2012). Here molecular mechanistic insight is provided, through direct measurements of enhanced ubiquitination of the γ2 subunit (Figure 2), lysosomal targeting (Figure 3), reduced surface synaptic α2/γ2 GABAAR levels (Figure 4), and reduced synaptic confinement (Figure 6) of DZP-sensitive GABAARs. Together this suggests BZD exposure primarily decreases synaptic retention of γ2 containing GABAAR while downregulating surface levels of the α2 subunit. Ubiquitination of the γ2 subunit by the E3 ligase Ring Finger Protein 34 (RNF 34) (Jin et al., 2014) is the only currently known mechanism targeting internalized synaptic GABAARs to lysosomes (Arancibia-Carcamo et al., 2009). Due to the requirement of the γ2 subunit in all BZD-sensitive GABAARs, it is likely that ubiquitination of the γ2 subunit is a contributing factor for increased lysosomal-mediated degradation in response to DZP. Despite a small decrease in the γ2 total protein, changes in surface levels were not significant by biochemical approaches, consistent with evidence that γ2-GABAAR surface levels are tightly regulated to maintain baseline inhibition and prevent excitotoxicity. For example, in heterozygous γ2 knockout mice a 50% reduction in γ2 levels appears to be compensated by increased cell surface trafficking, resulting in only an approximately 25% reduction in BZD binding sites in the cortex and a limited reduction in synaptic GABAAR clusters (Crestani et al., 1999; Ren et al., 2015). In contrast, homozygous γ2 knockout mice show a complete loss of behavioral drug response to BZD and over 94% of the BZD sites in the brain (GABA binding sites unchanged) and early lethality (Gunther et al., 1995). Similarly, studies have shown that prolonged GABAAR agonist or BZD application increases γ2 GABAAR internalization in cultured neurons, while surface GABAAR levels are variably affected (Chaumont et al., 2013; Nicholson et al., 2018). Importantly, by using high sensitivity surface GABAAR intersubunit FRET measurements we were able to detect a decrease in BZD sensitive α2/γ2 GABAARs (Figure 4).

The role of inhibitory scaffolding changes in responsiveness to BZD has been largely under investigated. Phosphorylation of gephyrin at Ser270 is mediated by CDK5 and GSK3β, while a partnering and functionally relevant Ser268 site is regulated by ERK (Tyagarajan et al., 2013). DZP time series experiments revealed a global decrease in ERK phosphorylation but not GSK3β, without a change in total kinase levels of ERK, GSK3β, or CDK5 over the course of the assay (except 12 h ERK) (Figure 5). A previous model by Tyagarajan et al. (2013) using gephyrin point mutants at Ser268 and Ser270 suggested that enhanced Ser270 phosphorylation coupled with decreased Ser268 phosphorylation by ERK promotes gephyrin remodeling and calpain-1 degradation. This is consistent with the ERK inactivation measured in our data and the increase in gephyrin Ser270 phosphorylation demonstrated by immunofluorescence after DZP (Figure 1), enhanced gephyrin degradation and decreased full-length gephyrin levels (Figures 1, 2). Calpain-1 mediated gephyrin cleavage can occur within 1 min in hippocampal membranes (Kawasaki et al., 1997), and cleavage products are increased following in vitro ischemia at 30 min and up to 48 h following ischemic events in vivo (Costa et al., 2015). Gephyrin cleavage may be occurring at earlier time points than the DZP 24 h mark measured here (Figures 2F,G), coinciding with ERK dephosphorylation as early as 45 min (Figures 5A,B). One limitation of our results is that measuring total and phospho levels of these kinases does not directly address changes in association or regulation of gephyrin, although it does provide an additional piece of evidence supporting gephyrin cleavage by calpain-1 and scaffold remodeling. Accordingly, our previous work found 30 min treatment with the GABAAR agonist muscimol in immature neurons (depolarizing) leads to ERK/BDNF signaling and decreased Ser270 phosphorylated gephyrin levels at synapses and overall (Brady et al., 2017). Thus, ERK activation status negatively correlates with the level of phosphorylation at gephyrin Ser270.

Recent work has demonstrated 12 h DZP treatment of organotypic hippocampal slices expressing eGFP-gephyrin causes enhanced gephyrin mobility at synapses and reduced gephyrin cluster size (Vlachos et al., 2013). Here we found the synaptic exchange rate of γ2 GABAARs and gephyrin to be nearly doubled at synapses in cortical neurons after ∼24 h DZP exposure (Figure 6). γ2 extrasynaptic fluorescence recovery in DZP treated neurons was variable but also trended toward an increase relative to controls (Figure 6), which could be a result of increased diffusion of receptors out of the synaptic space. This effect occurred coincident with the formation of truncated gephyrin cleavage products (Figure 2), which has previously been shown to decrease γ2 synaptic levels (Costa et al., 2015). These findings are also consistent with our previous work showing RNAi gephyrin knockdown doubles the rate of γ2-GABAAR turnover at synaptic sites (Jacob et al., 2005). Later quantum dot single particle tracking studies confirmed γ2 synaptic residency time is linked to gephyrin scaffolding levels (Renner et al., 2012). Importantly, GABAAR diffusion dynamics also reciprocally regulate gephyrin scaffolding levels (Niwa et al., 2012), suggesting gephyrin and GABAARs synaptic residency are often functionally coupled. Accordingly, γ2 subunit and gephyrin levels both decrease in responses to other stimuli including status epilepticus (Gonzalez et al., 2013) or prolonged inhibition of IP3 receptor-dependent signaling (Bannai et al., 2015). Additionally, chemically induced inhibitory long-term potentiation (iLTP) protocols demonstrate gephyrin accumulation occurs concurrent with the synaptic recruitment of GABAARs within 20 min (Petrini et al., 2014). Collectively, these proteins display a high degree of interdependence across different experimental paradigms of inhibitory synapse plasticity occurring over minutes to days.

Increasing receptor synaptic retention enhances synaptic currents, while enhanced receptor diffusion via decreased scaffold interactions reduces synaptic currents. For example, reduction of gephyrin binding by replacement of the α1 GABAAR subunit gephyrin binding domain with non-gephyrin binding homologous region of the α6 subunit results in faster receptor diffusion rates and a direct reduction in mIPSC amplitude (Mukherjee et al., 2011). Similarly, enhanced diffusion of GABAARs following estradiol treatment also reduces mIPSCs in cultured neurons and in hippocampal slices (Mukherjee et al., 2017). In contrast, brief DZP exposure (<1 h) reduces GABAAR synaptic mobility (Levi et al., 2015) without a change in surface levels (Gouzer et al., 2014), consistent with initial synaptic potentiation of GABAAR neurotransmission by DZP. Together with our current findings, this suggests post-translational modifications on GABAAR subunits or gephyrin that enhance receptor diffusion are a likely key step leading to functional tolerance to BZD drugs.

It is a significant technical challenge to examine dynamic alterations in receptor trafficking occurring in vivo. To overcome this we examined changes in γ2-GABAAR protein association following DZP injection in mice using quantitative proteomics and bioinformatics analysis. This work revealed shifts toward γ2-GABAAR association with protein pathway networks associated with endocytosis and organization of cytoskeleton (Figure 7B and Table 3), confirming similar fluctuations in membrane and intracellular trafficking occur in vivo and in vitro after DZP. We also found that shifts in association of proteins involved in the development of neurons (CAMKIIα, CDK5, NEFH, and calcineurin/PPP3CA) suggested an inhibition in this pathway after DZP (Figure 7B). When considering all protein hits between vehicle and DZP, γ2-GABAAR association with proteins involved in 14-3-3 mediated signaling and RhoA signaling pathways were greatly increased after DZP (Figure 7A, orange), while interaction with proteins involved in EIF2 signaling and sirtuin signaling pathways were reduced (Figure 7A, blue). 14-3-3 proteins are heavily linked in GABAAR intracellular to surface trafficking (Qian et al., 2012; Nakamura T. et al., 2016), and the RhoA signaling pathway is directly involved in actin cytoskeleton organization (Negishi and Katoh, 2002) and α5-GABAAR anchoring (Hausrat et al., 2015), providing further evidence of GABAAR shifts in membrane and cytosolic trafficking after DZP exposure.

Recent inhibitory synapse proteomics studies have identified a number of new protein synaptic constituents or modulators of GABAAR function (Butko et al., 2013; Kang et al., 2014; Nakamura Y. et al., 2016; Uezu et al., 2016; Ge et al., 2018). We show here that proteins known to have roles in synaptic function and trafficking of membrane receptors show changes in their association with γ2-receptors. For example, the calcium-sensitive kinase CaMKIIα was found to be significantly decreased in interaction with γ2-GABAAR following DZP, which can regulate GABAAR membrane insertion, synaptic retention and drug binding properties (Churn et al., 2002; Marsden et al., 2010; Saliba et al., 2012; Petrini et al., 2014) (Table 2). Calcineurin/PPP3CA has been recognized as a key regulator of GABAAR synaptic retention and plasticity (Bannai et al., 2009; Muir et al., 2010; Niwa et al., 2012; Bannai et al., 2015; Eckel et al., 2015) and has been linked to the response to DZP in vitro (Nicholson et al., 2018). Here we provide the first evidence that DZP exposure enhances the association of calcineurin with γ2-GABAARs in vivo. Furthermore, DZP was found to enhance γ2 association with 14-3-3 protein family members (Table 1), which are known mediators of GABAAR surface and intracellular trafficking (Qian et al., 2012; Nakamura T. et al., 2016). γ2 coassembly with the GABAAR α5 subunit was also elevated post DZP exposure (Table 1). Interestingly, the α5 subunit is required for the development of BZD sedative tolerance in mice (van Rijnsoever et al., 2004). It is notable that our proteomic studies are in part limited by the specificity of our antibody used and general downstream effects of reduced neuronal activity. Future follow up studies using the DZP site antagonist R015-1788 will be needed to dissect the individual roles of proteins found to be significantly altered in their association with GABAAR, and their physiological and pharmacological importance to BZD tolerance and inhibitory neurotransmission.

Through application of novel and highly sensitive fluorescence imaging approaches combined with in vivo proteomics, we provide unprecedented resolution of GABAAR synapse plasticity induced by BZDs at both the level of the single neuron and cortex. Our study reveals that sustained initial DZP treatment diminishes synaptic BZD sensitive GABAAR availability through multiple fundamental cellular mechanisms: through reduction of the post-synaptic scaffolding protein gephyrin; shifts toward intracellular trafficking pathways and targeting of receptors for lysosomal degradation; and enhanced synaptic exchange of both gephyrin and GABAARs. Proteomic and bioinformatics studies using DZP-treated mouse brain tissue provide further evidence that altered γ2-GABAAR surface and intracellular trafficking mechanisms play a critical role to the response to DZP in vivo. These results define key events leading to BZD irresponsiveness in initial sustained drug exposure. Future studies utilizing this dual approach will address the neuroadaptations produced by long term BZD use to systematically identify the effects of a critical drug class that has seen a tripling in prescription numbers over the last two decades (Bachhuber et al., 2016).

JL-G and TJ designed the research. JL-G, TJ, and SW wrote and revised the manuscript. JL-G performed the biochemistry, immunoprecipitation, bioinformatics analysis and fixed and live imaging acquisition and analysis in Figures 1–6. MB performed the FRET imaging and analysis. JL-G and SD performed the tissue collection. TJ, JL-G, and SW designed the Mass spectrometry experiments. SW and the Weintraub lab performed mass spectrometry and data was analyzed by JL-G, TJ, and SW.

This work was supported by funding from National Institutes of Health Grants R56MH114908-01 (to TJ), T32GM008424 (to JL-G), F31MH117839-01 (to JL-G), University of Pittsburgh Pharmacology and Chemical Biology Fellowship (to JL-G, William C. deGroat Neuropharmacology Departmental Fellowship), NARSAD young investigator grant R01MH114908-01A1 (to TJ) and Pharmacology and Chemical Biology Startup Funds.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

We thank Jonathan Beckel for technical advice on qRT-PCR and Katarina Vajn for assistance with neuronal cultures. Mass spectrometry analyses were conducted at the UTHSCSA Institutional Mass Spectrometry Laboratory, supported in part by UTHSCSA and the University of Texas System for purchase of the Orbitrap Fusion Lumos mass spectrometer. The expert technical assistance of Sammy Pardo and Dana Molleur is gratefully acknowledged. This manuscript has been released as a Pre-Print at bioRxiv (Lorenz-Guertin et al., 2019).

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fncel.2019.00163/full#supplementary-material

Ali, N. J., and Olsen, R. W. (2001). Chronic benzodiazepine treatment of cells expressing recombinant GABA(A) receptors uncouples allosteric binding: studies on possible mechanisms. J. Neurochem. 79, 1100–1108. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2001.00664.x

Alldred, M. J., Mulder-Rosi, J., Lingenfelter, S. E., Chen, G., and Luscher, B. (2005). Distinct gamma2 subunit domains mediate clustering and synaptic function of postsynaptic GABAA receptors and gephyrin. J. Neurosci. 25, 594–603. doi: 10.1523/jneurosci.4011-04.2005

Arancibia-Carcamo, I. L., Yuen, E. Y., Muir, J., Lumb, M. J., Michels, G., Saliba, R. S., et al. (2009). Ubiquitin-dependent lysosomal targeting of GABA(A) receptors regulates neuronal inhibition. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 17552–17557. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0905502106

Bachhuber, M. A., Hennessy, S., Cunningham, C. O., and Starrels, J. L. (2016). Increasing benzodiazepine prescriptions and overdose mortality in the united states, 1996-2013. Am. J. Public Health 106, 686–688. doi: 10.2105/ajph.2016.303061

Bannai, H., Levi, S., Schweizer, C., Inoue, T., Launey, T., Racine, V., et al. (2009). Activity-dependent tuning of inhibitory neurotransmission based on GABAAR diffusion dynamics. Neuron 62, 670–682. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.04.023

Bannai, H., Niwa, F., Sherwood, M. W., Shrivastava, A. N., Arizono, M., Miyamoto, A., et al. (2015). Bidirectional control of synaptic GABAAR clustering by glutamate and calcium. Cell Rep. 13, 2768–2780. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.12.002

Bateson, A. N. (2002). Basic pharmacologic mechanisms involved in benzodiazepine tolerance and withdrawal. Curr. Pharm. Des. 8, 5–21. doi: 10.2174/1381612023396681

Battaglia, S., Renner, M., Russeau, M., and Come, E. (2018). Activity-dependent inhibitory synapse scaling is determined by gephyrin phosphorylation and subsequent regulation of GABAA receptor diffusion. eNeuro 5:ENEURO.0203-17.2017. doi: 10.1523/eneuro.0203-17.2017

Bogdanov, Y., Michels, G., Armstrong-Gold, C., Haydon, P. G., Lindstrom, J., Pangalos, M., et al. (2006). Synaptic GABAA receptors are directly recruited from their extrasynaptic counterparts. EMBO J. 25, 4381–4389. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601309

Brady, M. L., and Jacob, T. C. (2015). Synaptic localization of alpha5 GABA (A) receptors via gephyrin interaction regulates dendritic outgrowth and spine maturation. Dev. Neurobiol. 75, 1241–1251. doi: 10.1002/dneu.22280

Brady, M. L., Pilli, J., Lorenz-Guertin, J. M., Das, S., Moon, C. E., Graff, N., et al. (2017). Depolarizing, inhibitory GABA type A receptor activity regulates GABAergic synapse plasticity via ERK and BDNF signaling. Neuropharmacology 128, 324–339. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2017.10.022

Butko, M. T., Savas, J. N., Friedman, B., Delahunty, C., Ebner, F., Yates, J. R. III, et al. (2013). In vivo quantitative proteomics of somatosensory cortical synapses shows which protein levels are modulated by sensory deprivation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110, E726–E735. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1300424110

Chaumont, S., Andre, C., Perrais, D., Boue-Grabot, E., Taly, A., and Garret, M. (2013). Agonist-dependent endocytosis of gamma-aminobutyric acid type A (GABAA) receptors revealed by a gamma2(R43Q) epilepsy mutation. J. Biol. Chem. 288, 28254–28265. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.470807

Churn, S. B., Rana, A., Lee, K., Parsons, J. T., De Blas, A., and Delorenzo, R. J. (2002). Calcium/calmodulin-dependent kinase II phosphorylation of the GABAA receptor alpha1 subunit modulates benzodiazepine binding. J. Neurochem. 82, 1065–1076. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2002.01032.x

Costa, J. T., Mele, M., Baptista, M. S., Gomes, J. R., Ruscher, K., Nobre, R. J., et al. (2015). Gephyrin cleavage in in vitro brain ischemia decreases GABA receptor clustering and contributes to neuronal death. Mol. Neurobiol. 53, 3513–3527. doi: 10.1007/s12035-015-9283-2

Crestani, F., Lorez, M., Baer, K., Essrich, C., Benke, D., Laurent, J. P., et al. (1999). Decreased GABAA-receptor clustering results in enhanced anxiety and a bias for threat cues. Nat. Neurosci. 2, 833–839. doi: 10.1038/12207

Crider, A., Pandya, C. D., Peter, D., Ahmed, A. O., and Pillai, A. (2014). Ubiquitin-proteasome dependent degradation of GABAAα1 in autism spectrum disorder. Mol. Autism 5:45. doi: 10.1186/2040-2392-5-45

Dantuma, N. P., Groothuis, T. A., Salomons, F. A., and Neefjes, J. (2006). A dynamic ubiquitin equilibrium couples proteasomal activity to chromatin remodeling. J. Cell Biol. 173, 19–26. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200510071

Di, X. J., Wang, Y. J., Han, D. Y., Fu, Y. L., Duerfeldt, A. S., Blagg, B. S., et al. (2016). Grp94 protein delivers gamma-aminobutyric acid type a (GABAA) receptors to Hrd1 protein-mediated endoplasmic reticulum-associated degradation. J. Biol. Chem. 291, 9526–9539. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.705004

Eckel, R., Szulc, B., Walker, M. C., and Kittler, J. T. (2015). Activation of calcineurin underlies altered trafficking of alpha2 subunit containing GABAA receptors during prolonged epileptiform activity. Neuropharmacology 88, 82–90. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2014.09.014

Essrich, C., Lorez, M., Benson, J. A., Fritschy, J. M., and Luscher, B. (1998). Postsynaptic clustering of major GABAA receptor subtypes requires the gamma 2 subunit and gephyrin. Nat. Neurosci. 1, 563–571. doi: 10.1038/2798

File, S. E., Wilks, L. J., and Mabbutt, P. S. (1988). Withdrawal, tolerance and sensitization after a single dose of lorazepam. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 31, 937–940. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(88)90408-x

Flores, C. E., Nikonenko, I., Mendez, P., Fritschy, J. M., Tyagarajan, S. K., and Muller, D. (2015). Activity-dependent inhibitory synapse remodeling through gephyrin phosphorylation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 112, E65–E72. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1411170112

Förster, T. (1965). Delocalized Excitation and Excitation Transfer. New York, NY: Academic Press Inc.

Gallager, D. W., Lakoski, J. M., Gonsalves, S. F., and Rauch, S. L. (1984). Chronic benzodiazepine treatment decreases postsynaptic GABA sensitivity. Nature 308, 74–77. doi: 10.1038/308074a0

Ge, Y., Kang, Y., Cassidy, R. M., Moon, K. M., Lewis, R., Wong, R. O. L., et al. (2018). Clptm1 limits forward trafficking of GABAA receptors to scale inhibitory synaptic strength. Neuron 97, 596–610.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2017.12.038

Ghosh, H., Auguadri, L., Battaglia, S., Simone Thirouin, Z., Zemoura, K., Messner, S., et al. (2016). Several posttranslational modifications act in concert to regulate gephyrin scaffolding and GABAergic transmission. Nat. Commun. 7:13365. doi: 10.1038/ncomms13365

Gonzalez, M. I., Cruz Del Angel, Y., and Brooks-Kayal, A. (2013). Down-regulation of gephyrin and GABAA receptor subunits during epileptogenesis in the CA1 region of hippocampus. Epilepsia 54, 616–624. doi: 10.1111/epi.12063

Gouzer, G., Specht, C. G., Allain, L., Shinoe, T., and Triller, A. (2014). Benzodiazepine-dependent stabilization of GABA(A) receptors at synapses. Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 63, 101–113. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2014.10.004

Gu, Y., Chiu, S. L., Liu, B., Wu, P. H., Delannoy, M., Lin, D. T., et al. (2016). Differential vesicular sorting of AMPA and GABAA receptors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 113, E922–E931. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1525726113

Gunther, U., Benson, J., Benke, D., Fritschy, J. M., Reyes, G., Knoflach, F., et al. (1995). Benzodiazepine-insensitive mice generated by targeted disruption of the gamma 2 subunit gene of gamma-aminobutyric acid type A receptors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 92, 7749–7753. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.17.7749

Gutierrez, M. L., Ferreri, M. C., and Gravielle, M. C. (2014). GABA-induced uncoupling of GABA/benzodiazepine site interactions is mediated by increased GABAA receptor internalization and associated with a change in subunit composition. Neuroscience 257, 119–129. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2013.10.077

Hausrat, T. J., Muhia, M., Gerrow, K., Thomas, P., Hirdes, W., Tsukita, S., et al. (2015). Radixin regulates synaptic GABAA receptor density and is essential for reversal learning and short-term memory. Nat. Commun. 6:6872. doi: 10.1038/ncomms7872