- 1Research Unit, Instituto Peruano de Neurociencias, Lima, Peru

- 2Cognitive Decline and Dementia Diagnostic and Prevention Services Unit, Instituto Peruano de Neurociencias, Lima, Peru

- 3Neurology Department, Instituto Peruano de Neurociencias, Lima, Peru

- 4Neuromedicenter Adult Day Care Center, Quito, Ecuador

- 5Facultad de Ciencias de la Salud, Universidad Científica del Sur, Lima, Peru

- 6Neuropsychology and Clinical Neuroscience Laboratory (LANNEC), Physiopathology Department, ICBM, Neurosciences and East Neuroscience Departments, University of Chile School of Medicine, Santiago, Chile

- 7Geroscience Center for Brain Health and Metabolism (GERO), University of Chile School of Medicine, Santiago, Chile

- 8Memory and Neuropsychiatric Clinic (CMYN), Neurology Department, Del Salvador Hospital and University of Chile School of Medicine, Santiago, Chile

- 9Neurology Unit, Department of Medicine, Alemana Clinic, Universidad del Desarrollo, Santiago, Chile

Objectives: The aim of this study was to evaluate the validity of brief cognitive screening (BCS) tools designed to diagnose mild cognitive impairment (MCI) or dementia in Spanish-speaking individuals over the age of 50 years from Latin America (LA).

Methods: A systematic search of titles and abstracts in Medline, Biomed Central, Embase, Scopus, Scirus, PsycINFO, LILACS, and SciELO was conducted. Inclusion criteria were papers written in English or Spanish involving samples from Spanish-speaking Latin American individuals published until 2018. Standard procedures were applied for reviewing the literature. The data related to the study sample, methodology, and procedures applied, as well as the performance obtained with the corresponding BCS, were collected and systematized.

Results: Thirteen of 211 articles met the inclusion criteria. The studies primarily involved memory clinic-based samples, with the exception of two studies from an adult day-care center, one from a primary care clinic, and one from a community-based sample. All the studies originated from five of the 20 countries of LA and all used standardized diagnostic criteria for the diagnosis of dementia and MCI; however, the diagnostic protocols applied differed. Most studies reported samples with an average of 10 years of education and only one reported a sample with an average of <5 years of education. No publication to date has included an illiterate population. Although the Montreal cognitive assessment (MoCA) is the most widely-used BCS tool in LA, it is significantly influenced by education level.

Conclusions: Although evidence is still limited, the findings from studies on LA populations suggest that MoCA requires cultural adaptations and different cutoff points according to education level. Moreover, the diagnostic validity of the INECO frontal screening (IFS) test should be evaluated in populations with a low level of education. Given the heterogeneity that exists in the levels of education in LA, more studies involving illiterate and indigenous populations are required.

Introduction

Dementia has become a public health priority in Latin America (LA) owing to the increasing life expectancy of the population, which has led to escalating rates of neurological disorders (Custodio et al., 2017c). The number of people with dementia in LA is expected to rise fourfold by 2050 (Parra et al., 2018). By 2020, it is estimated that 89.28 million people will be living with dementia in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), compared with 42.18 million in high-income nations (Bongaarts, 2009). Timely diagnosis is one of the most promising strategies for addressing dementia and reducing patient and caregiver morbidity (Watson et al., 2018). However, dementia is significantly underdiagnosed, especially in LMICs. Indeed, some studies have suggested that only 3% of dementia patients are diagnosed by their primary care providers in these countries (Chong et al., 2016), and it is estimated that 77% of dementia cases in Brazil go undiagnosed (Nakamura et al., 2015). Barriers to dementia diagnosis that are particularly relevant to LA include inadequate physician training (Olavarría et al., 2016; Mansfield et al., 2019), especially among primary care providers (Saxena et al., 2007; Parra et al., 2018); lack of knowledge about different types of dementia, such as frontotemporal dementia (FTD) (Gleichgerrcht et al., 2011; Custodio et al., 2018a); language barriers; the stigma associated with age-related health problems; insufficient access to healthcare; a lack of diagnostic protocols; and scarcity of neuropsychological services (Custodio et al., 2017c; Parra et al., 2018).

The brief cognitive screen (BCS) is an instrument used to detect signs of dementia that does not include caregiver or information interviews. BCSs can be a useful tool for timely dementia detection, and can be used both for screening the general geriatric population and confirming the presence of a cognitive disorder in people with clinical suspicion of dementia (Brown, 2014; Velayudhan et al., 2014).

BCSs are routinely used in clinical practice, both to detect cognitive decline or dementia and to monitor disease evolution and treatment response (Carnero-Pardo, 2014). A positive screening result can provide a “wake-up call” to providers and caregivers that a detailed cognitive evaluation is indicated (Zucchella et al., 2018). BCSs are crucial for identifying the presence of a cognitive syndrome and initiating the diagnostic process, which may include supporting tests such as blood tests, brain imaging, and eventually a formal neuropsychological evaluation (Brown, 2014; Custodio et al., 2018b; Parra et al., 2018).

An appropriate BCS should fulfill the following characteristics: Administration time should be brief (no longer than 5 min for primary care or 10 min for specialist care) and require minimal additional material; the tools should be user-friendly and easy to administer and score; studies that provide norms and show that the instrument has appropriate psychometric properties should be available (Carnero-Pardo, 2014); the tool should be applicable to all patients regardless of education level, sociodemographic characteristics, and ethnic or cultural group; finally, it is important that the BCS can be administered by any professional (specialists, primary care physicians, or other nonmedical personnel) and in any location (home, outpatient office, or hospital). Evidence suggests that physicians and primary care nurses, if adequately trained, are capable of performing dementia screening with reasonable accuracy, using clinical observations and routine tests, during a typical office visit (Prince et al., 2011). With a few hours of training, community health workers in LMICs can identify signs of dementia with a positive predictive value of 66% (Ramos-Cerqueira et al., 2005).

The mini-mental state examination (MMSE) is the most widely used of the available BCS tools, and has been validated in LA (Ostrosky-Solís et al., 2000; Rosselli et al., 2000; De Beaman et al., 2004; Franco-Marina et al., 2010). However, this method has several drawbacks. Administration is not standardized; the cultural and socioeconomic characteristics of the patient may bias scores, and the tool can detect dementia only in individuals with at least 5 years of education; the tool does not measure executive function; finally, the MMSE can only detect moderate or advanced dementia, and is not sensitive to early-stage Alzheimer's disease dementia (ADD) or non-Alzheimer's dementias (Dubois et al., 2000). Recently, other BCSs have been proposed as substitutes, such as the Montreal cognitive assessment (MoCA) (Gómez et al., 2013; Pereira-Manrique and Reyes, 2013; Gil et al., 2014; Pedraza et al., 2016; Aguilar-Navarro et al., 2017; Delgado et al., 2017), Addenbrooke's cognitive examination (ACE) (Sarasola et al., 2005; Custodio et al., 2012; Herrera-Pérez et al., 2013), ACE-III (Bruno et al., 2017), and Addenbrooke's cognitive examination-revised (ACE-R) (Torralva et al., 2011; Muñoz-Neira et al., 2012a; Ospina, 2015), as well as complimentary tools designed to measure specific domains such as the memory alteration test (M@T) (Custodio et al., 2014, 2017a), INECO frontal screening (IFS) (Torralva et al., 2009; Ihnen Jory et al., 2013; Custodio et al., 2016), and frontal assessment battery (FAB; Dubois et al., 2000).

For use in LA, a BCS tool should be adapted, standardized, and validated for the region (Dua et al., 2011). To reflect the sociodemographic characteristics of older adults in LA, which include high indices of illiteracy and the presence of indigenous populations, data should also be available for individuals from both urban and rural areas and with various levels of education, including illiterate individuals (Carnero-Pardo, 2014; UNESCO, 2015, 2017; Instituto Nacional de Estadística e Informática., 2018). Although several reviews are available for BCSs in other countries and continents (Paddick et al., 2017; De Roeck et al., 2019; Magklara et al., 2019), no critical BSC-related reviews have been published for LA populations. Therefore, the objective of this article is to review studies on BCS designed to discriminate between normal cognition and mild cognitive impairment (MCI) or dementia in Spanish-speaking individuals over the age of 50. We also discuss the diagnostic accuracy of BCS methods designed to discriminate between amnestic MCI (aMCI) or early AD and normal cognition in Spanish-speaking individuals over the age of 50 years.

Methods

Search Criteria

Suitable published studies were identified by searching the following databases: Medline, Biomed Central, Embase, Scopus, Scirus, PsycINFO, LILACS, and SciELO. Three of the authors (RM, MM, and LD) independently searched for articles associated with the following terms in English: [(Dementia) OR (Cognitive Impairment)] AND [(Screening) OR (questionnaires) OR (brief cognitive screening) OR (validity)] AND [(“Latin America” OR “Hispanic American” OR “South America” OR “Caribbean” OR “Latinos” OR “Mexico” OR “Colombia” OR “Argentina” OR “Chile” OR “Peru”)]. Next, the authors performed a search for the same terms in Spanish. The authors searched for articles published between 1953 and July 30, 2018, considering that PRISMA for Systematic Review (Moher et al., 2015).

Inclusion/Eligibility Criteria

Study titles and abstracts were independently read by RM, MM, and LD to exclude duplications or articles unrelated to the validation of a BCS. After obtaining the full text of each article, the following inclusion criteria were applied: the study was carried out on Spanish-speaking individuals over the age of 50; a standardized protocol was used for the diagnostic process; the study was carried out in a memory clinic or research center based in LA; BCSs took less than 15 min to administer; psychometric measures (content validity, criterion validity, internal consistency, and diagnostic validity) were available; and the BCS was compared with gold-standard diagnostic criteria (including the last three versions of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders [DSM]; diagnosis by a neurologist, psychiatrist, or geriatrician; or diagnosis based on a detailed neuropsychological evaluation). BCSs were included irrespective of the type of dementia evaluated.

Exclusion Criteria

Studies were excluded if they were based on tests administered by telephone, self-evaluations, and caregiver or informant interviews, or if the analysis was limited to a simple correlation between the BCS and a previously established neuropsychological battery. Studies were excluded if the tests evaluated were detailed neuropsychological batteries or screenings for cognitive decline secondary to depression, traumatic brain injury, or cerebrovascular disorder.

Selection of Studies

The full text of every article was read by NC and CA. These authors analyzed the data on the process of translating or culturally adapting the tool when the original BCS was written in a language other than Spanish. The quality of the translation and cultural adaptation procedures reported were evaluated using the Manchester translation reporting questionnaire (MTRQ) and Manchester cultural adaptation reporting questionnaire (MCAR), respectively. Both the MTRQ and MCAR (Landis and Koch, 1977) are seven-point scales developed by the Center for Primary Care Research at the University of Manchester to quantify the quality of procedures reported for translation and cultural adaptation of neuropsychological evaluations. For BCSs originally written in Spanish, only the MCAR was applied. Studies were included in this analysis if they received a score of at least 2a on the MTRQ and MCAR. Given that there are several Spanish-language versions available for the MoCA, and that the original authors have not authorized these versions, we analyzed studies that met the above inclusion/exclusion criteria. When necessary, authors were contacted to obtain the full text of the study or additional unpublished data.

Analysis and Evaluation of BCSs

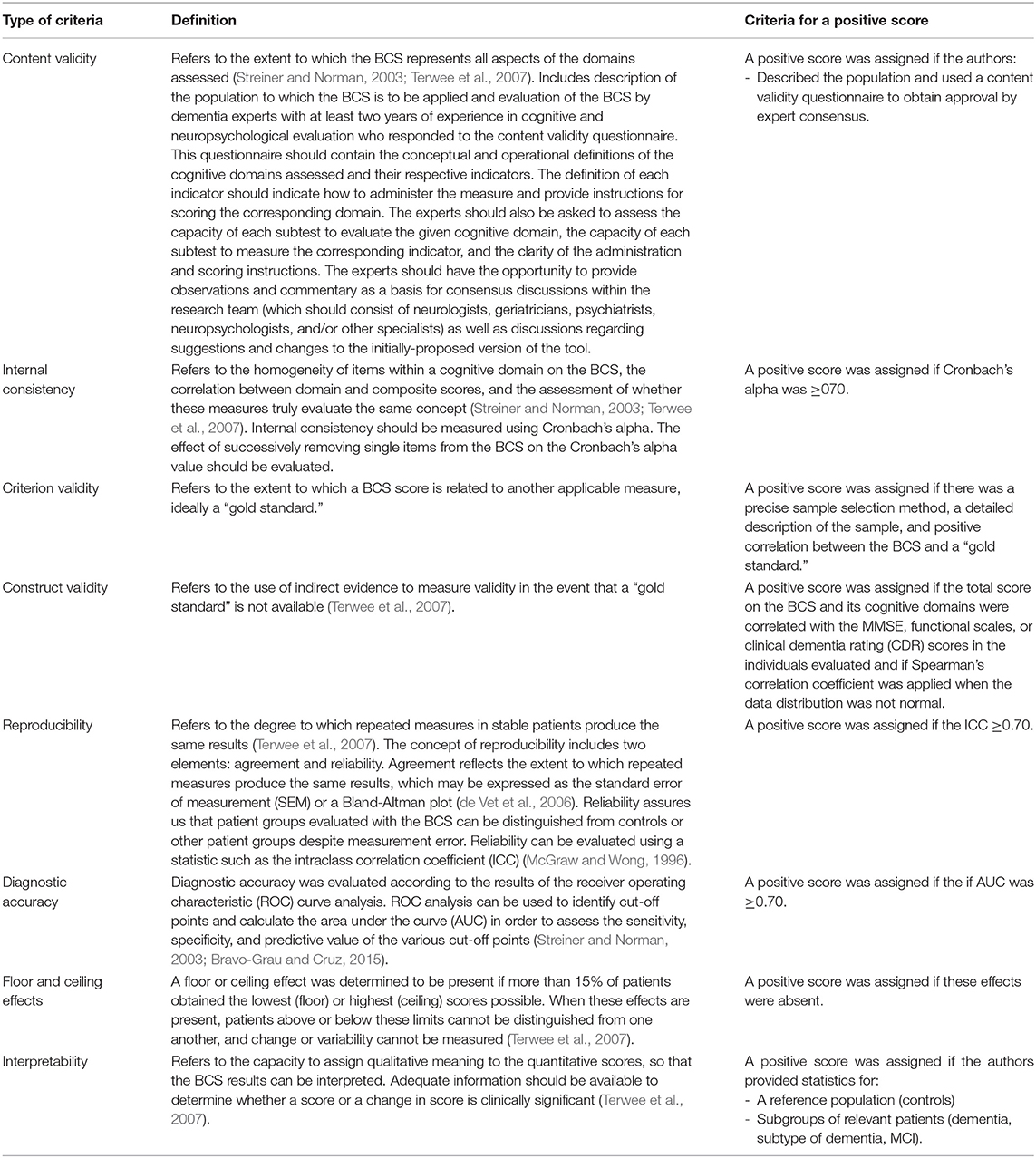

NC, MM, and LD recorded specific data for each study, including the author name(s), year, and complete title of the publication; site where the research was performed (specifically, the location from which the study sample was recruited); study objectives; type of BCS used; cognitive domains evaluated, categorizing each study as a domain-specific or global evaluation; geographic location; institution that performed the research; type of dementia evaluated; and diagnostic utility. The quality of the BCS was evaluated according to the following properties: content validity, internal consistency, criterion validity, construct validity, reproducibility, diagnostic accuracy, floor/ceiling effects, and interpretability (see Table 1). Each evaluated property was scored separately by two authors (RM and MM) as positive, negative, or indeterminate. In general, a positive score was assigned if the characteristics of the property were mentioned in the study design and described in detail in the methods and analysis of results. A negative score was assigned if the characteristics of the property did not meet these criteria. A score of “indeterminate” was assigned if the characteristics of each property were mentioned in a general manner in the study design, but a detailed description was not included in the methods and analysis of results. A score of “indeterminate” was also assigned if the characteristics of the property were not mentioned or described in the methods or analysis of results.

Results

Studies Included

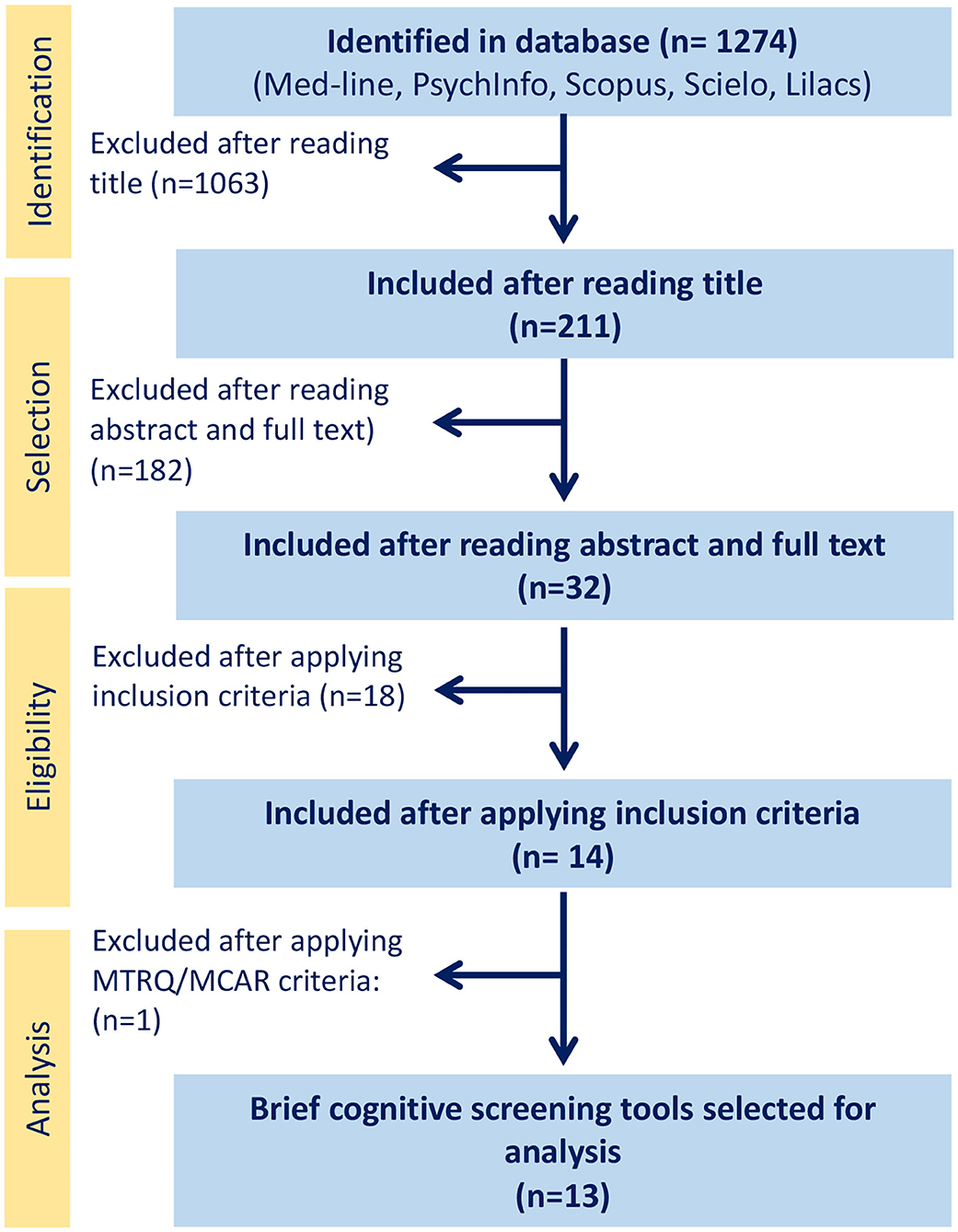

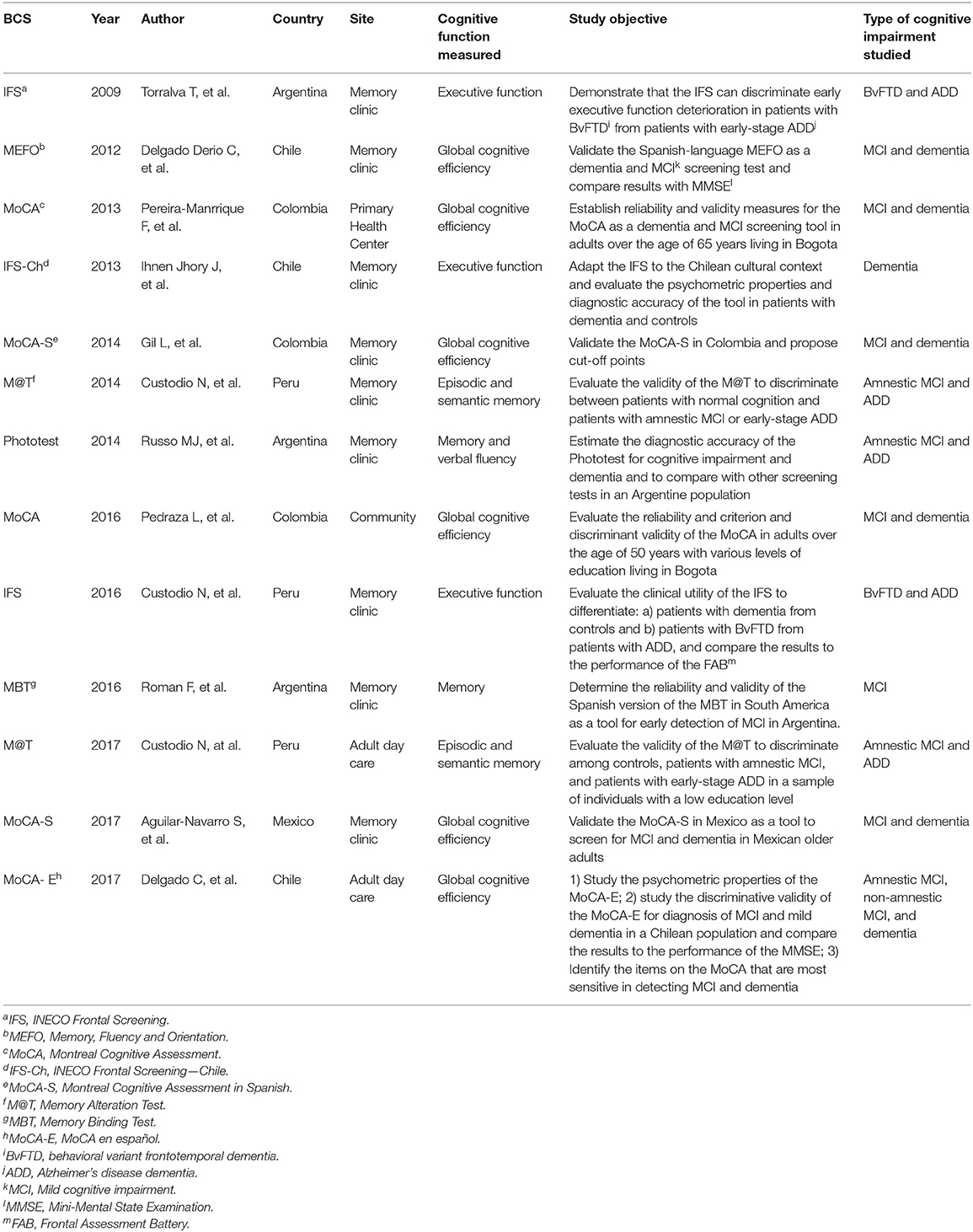

After reading the abstract and full text of each study, our search identified 32 studies on BCSs to detect cognitive decline or dementia carried out in LA. The selection process is depicted in the flowchart in Figure 1. After applying the inclusion criteria, 18 studies were excluded for the following reasons: two for the absence of a standardized diagnostic protocol for study sample selection (Iturra-mena, 2007; Cantor-Nieto and Avendaño-Prieto, 2016); two for the use of another BCS, such as the Leganés cognitive test (Gómez et al., 2013) or the MEC Lobo, as the diagnostic criterion for study sample selection (Serrani Azcurra, 2013); six for the use of a tool that takes more than 15 min to administer, such as ACE (Sarasola et al., 2005; Custodio et al., 2012; Herrera-Pérez et al., 2013) or ACE-R (Torralva et al., 2011; Muñoz-Neira et al., 2012a; Ospina, 2015); three for not reporting diagnostic accuracy measures (Rosselli et al., 2000; Labos et al., 2008; Pedraza et al., 2014); four for reporting only one diagnostic accuracy measure (Ostrosky-Solís et al., 2000; Quiroga et al., 2004; Franco-Marina et al., 2010; Oscanoa et al., 2016); and one for including patients with depression in the sample (Fiorentino et al., 2013). After applying the MTRQ/MCAR to the 14 remaining publications, a study validating the Manos version of the clock-drawing test was also excluded (Custodio et al., 2011) as the translation and cultural adaptation process was not described. Finally, 13 publications were selected for the definitive analysis (see the description in Table 2), five of which evaluated the MoCA (Pereira-Manrique and Reyes, 2013; Pedraza et al., 2016; Aguilar-Navarro et al., 2017; Delgado et al., 2017), three the IFS (Torralva et al., 2009; Ihnen Jory et al., 2013; Custodio et al., 2016), two the M@T (Custodio et al., 2014, 2017a), and one the memory, fluency, and orientation (MEFO) test (Delgado Derio et al., 2013); the Phototest (Russo et al., 2014) and the last one, about Memory Binding Test (MBT) (Roman et al., 2016). Of these publications, three were from Chile (Delgado Derio et al., 2013; Ihnen Jory et al., 2013; Delgado et al., 2017), three from Peru (Custodio et al., 2014, 2016, 2017a), three from Colombia (Pereira-Manrique and Reyes, 2013; Gil et al., 2014; Pedraza et al., 2016), three from Argentina (Torralva et al., 2009), and one from Mexico (Aguilar-Navarro et al., 2017). The tests assessed global cognitive function, memory, and executive function. All the publications assessing the MoCA (Pereira-Manrique and Reyes, 2013; Gil et al., 2014; Pedraza et al., 2016; Aguilar-Navarro et al., 2017; Delgado et al., 2017) and the MEFO test (Delgado Derio et al., 2013) compared the performance of control groups, patients with MCI, and patients with dementia. Two (Torralva et al., 2009; Custodio et al., 2016) of the three studies assessing the IFS test also evaluated the capacity of this test to detect FTD and early-stage ADD. The studies assessing the M@T (Custodio et al., 2014, 2017a) and the Phototest (Russo et al., 2014) evaluated the capacity of the test to discriminate patients with aMCI and early ADD from controls; meanwhile the MBT (Roman et al., 2016) comparing control and patients with MCI. All studies were clinically defined but no biomarkers were used to define whether these patients had ADD.

Analysis and Quality of the BCS Tools

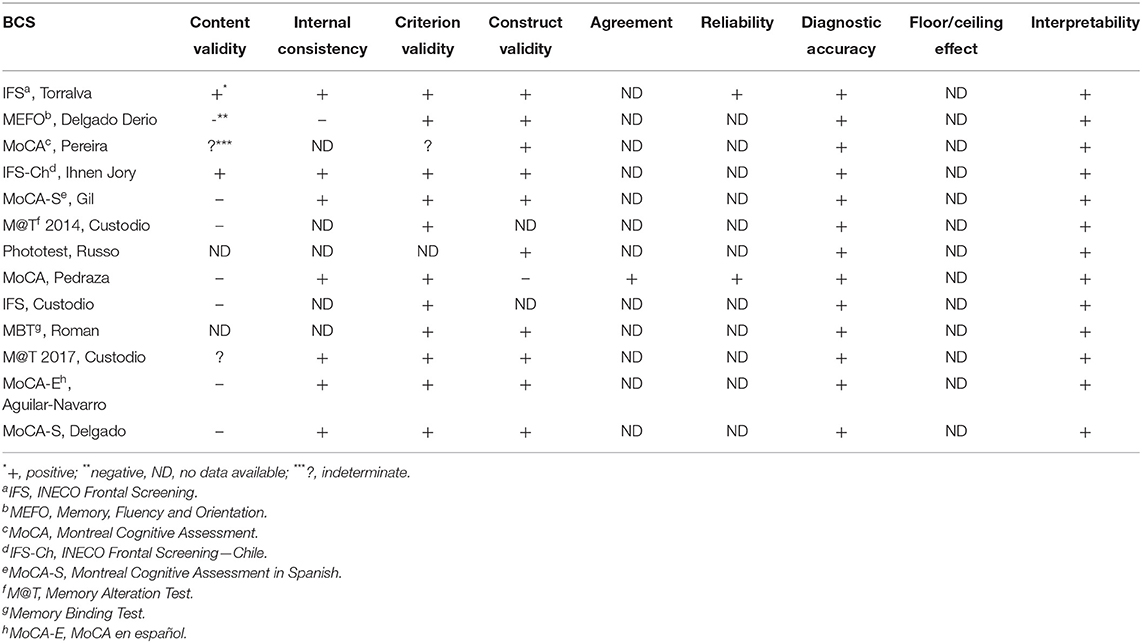

A summary of the psychometric properties of the BCS tests for early dementia detection in older Spanish-speaking adults in LA is shown in Table 3.

Table 3. Psychometric properties of BCS for early dementia detection in Spanish-speaking LA older adults.

Content Validity

Only two of the publications (Torralva et al., 2009; Ihnen Jory et al., 2013) provided an adequate description of the study and the process of adaptation to the local cultural context before the administration of the test. The validity of the BCS was assessed by consulting with a group of experts using a content validity questionnaire.

Internal Consistency

A Cronbach's alpha of 0.69 was reported for the MEFO test (Delgado Derio et al., 2013). This statistic was not reported in one of the studies evaluating the MoCA in Colombia (Pereira-Manrique and Reyes, 2013) or in the studies assessing the IFS (Custodio et al., 2016) or M@T (Custodio et al., 2014) in Peru. The studies that evaluated the Phototest (Russo et al., 2014) and the MBT (Roman et al., 2016) also did not report on internal consistency.

Criterion Validity

Twelve of the 13 studies met the gold standard for this measure, the exception being the study by Pereira-Manrique and Reyes (2013), that was rated as “indeterminate” as the methods only mentioned in a general manner that the diagnosis of dementia was based on DSM-IV-TR criteria, and not data available in Phototest's study (Russo et al., 2014).

Construct Validity

Only two studies failed to provide data (Custodio et al., 2014, 2016) correlating the BCS with the MMSE or other global functioning scale such as the clinical dementia rating (CDR).

Reproducibility

Most of the studies failed to provide the data necessary to evaluate this characteristic. Only one study (Pereira-Manrique and Reyes, 2013) provided adequate data on concordance and reliability. The study by Torralva et al. (2009) only presented data on reliability.

Diagnostic Accuracy

All the studies met diagnostic accuracy criteria for various cut-off points.

Floor and Ceiling Effects

None of the 13 studies reported results for this characteristic.

Interpretability

All the investigators included a comparison group (controls vs. patients with dementia, controls vs. patients with MCI) to evaluate the results of BCSs, and the diagnostic accuracy measures allowed the authors to establish cut-off points to discriminate between the groups.

Measures of Diagnostic Accuracy

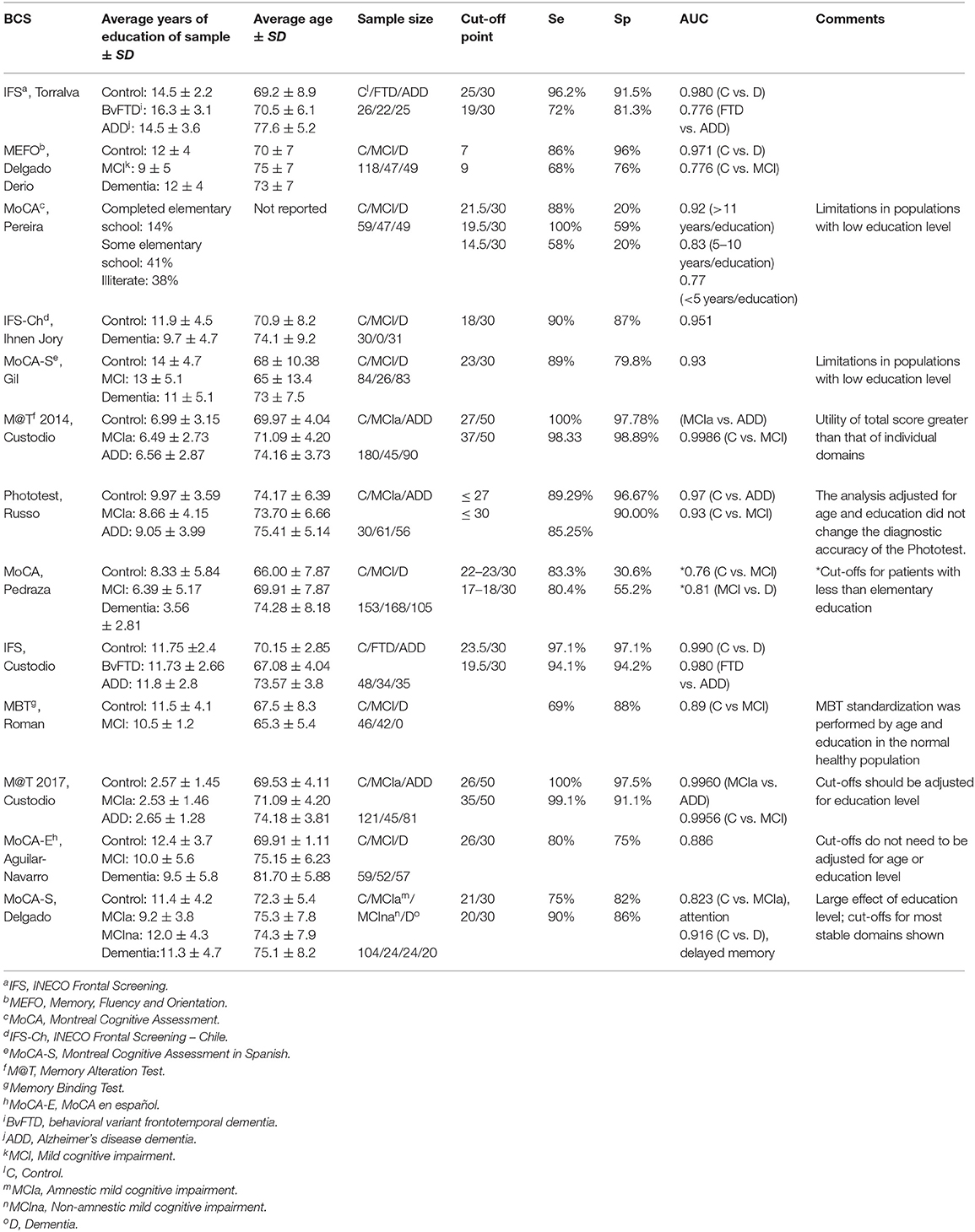

To analyze the diagnostic accuracy measures for the BCS to discriminate MCI and dementia from normal cognition in Spanish-speaking patients over the age of 50, we assessed performance according to age and education level, requesting additional information if the publication did not provide this data. Olga Pedraza (Pedraza et al., 2016) responded via email with the number of cases per group evaluated, as well as the age and education level of each group (control, MCI, and dementia) (see Table 4).

Table 4. Education level and age of study samples and diagnostic accuracy measures for BCS to detect MCI and dementia in Spanish-speaking adults over the age of 50 years.

In general, the studies analyzed involved study samples with an average of 10 years of education. Two studies involving the MoCA test (Pereira-Manrique and Reyes, 2013; Pedraza et al., 2016) and one involving the M@T (Custodio et al., 2014) reported a sample with an average of 5–10 years of education, and only one (Custodio et al., 2017a) reported a sample with an average of <5 years of education. One study, only compared controls and patients with dementia (Ihnen Jory et al., 2013) and other, only compared controls and patients with MCI (Roman et al., 2016). All of the studies involving the MoCA found that education level biased scores, with the exception of the study carried out in Mexico (Aguilar-Navarro et al., 2017). Finally, our review yields important differences in publishing data, mainly: population heterogeneity, heterogeneity in screening tests explaining by the difference in their application and validity, use of different diagnostic criteria limiting the combination of results of the publications to calculate cut-off points, sensibility, and specificity. Therefore, it was not possible to calculate metrics by gathering data of the published papers.

Discussion

The objective of this study was to review evidence on the use of BCS test in detecting MCI and dementia in a LA population. The main conclusions of this review were that relatively studies have evaluated BCSs with adequate diagnostic accuracy measures in LA populations, and most of the BCS tests were validated in a memory clinic setting. Finally, the validated BCSs studied differed in terms of the cognitive domains evaluated. A large number of screening tests for ADD are available; however, most are only validated in a memory clinic setting and description of the psychometric properties of the instruments is limited. Analyzed tests, in particular, require further research. The MoCA is a promising BCS instrument, but shows low specificity in detecting early ADD.

After applying exclusion criteria, only 13 studies were retained for analysis in this review. These studies were performed in five countries. No studies on validated BCSs with adequate diagnostic accuracy measures performed in other countries in the region were identified. While there is a certain level of linguistic homogeneity in LA, studies on the standardization of neuropsychological batteries have suggested that significant differences exist among countries in terms of neuropsychological tests (Arango-Lasprilla, 2015). Given that reviews of BCS tools for other parts of the world have included up to 120 studies (De Roeck et al., 2019), our findings suggest that there is a notable lack of studies validating BCS tools in Spanish-speaking LA countries. Additional studies that include other LA countries are needed. Most of the studies identified were carried out in memory clinics, with only two being undertaken in adult day care centers (Custodio et al., 2017a; Delgado et al., 2017), one in a primary health center (Pereira-Manrique and Reyes, 2013) and one in the community (Pedraza et al., 2016). This finding is noteworthy given that results from memory clinics are not extrapolable to primary care centers and community samples. Indeed, BCSs have been reported to perform better in the community that in the clinical context (Paddick et al., 2017). However, some community-based studies have excluded individuals with significant sensory deficits, which may artificially inflate the diagnostic accuracy of the BCS (De Roeck et al., 2019). Additionally, studies in clinical contexts such as memory clinics or adult day care centers may include an elevated proportion of individuals with general frailty or medical conditions, which may also adversely affect the performance on the evaluated BCS test (Paddick et al., 2017; De Roeck et al., 2019). Owing to the high rate of underdiagnosis of dementia, there is a need for properly validated BCS tools in primary care centers. In general, results from community-based studies can reflect the true prevalence and severity of mild cognitive impairment and dementia, because when studies are conducted in specialized memory centers in clinics or general hospitals, the prevalence and severity tend to be higher. Furthermore, in this way, BCS tools could be used by primary care professionals, especially in rural populations.

All the studies included in this review analyzed the criterion validity and diagnostic accuracy of the BCS assessed, and most reported internal consistency and construct validity. Only one study addressed agreement (Pedraza et al., 2016), and two studies reported the reliability of the BCS (Torralva et al., 2009; Pedraza et al., 2016). None of the studies reported a floor/ceiling effect, which is consistent with the findings of previous reviews (Paddick et al., 2017; De Roeck et al., 2019; Magklara et al., 2019).

Most of the BCSs included in this review evaluated global cognitive efficiency, while a few assessed executive function (Torralva et al., 2009; Ihnen Jory et al., 2013; Custodio et al., 2016) or memory (Custodio et al., 2014, 2017a). Notably, vascular cognitive impairment, vascular dementia (VD), and mixed dementias are more common in LMICs than in higher-income countries; importantly, these dementias are best detected with global BCS tests or those that measure executive function (Dubois et al., 2000; Maestre et al., 2018). BCS tests that only evaluate memory have a better capacity to detect typical cases of Alzheimer's dementia, while BCS tests that evaluate executive function are superior for identifying disorders involving the prefrontal cortex, such as FTD and VD but are limited ability in their ability to identify other subtypes of dementia (Ihara et al., 2013).

MoCA is the most widely-used BCS in LA, especially in Colombia (Pereira-Manrique and Reyes, 2013; Gil et al., 2014; Pedraza et al., 2016). All the studies evaluating the MoCA carried out in Colombia reported that the education level biased the results, as did a study performed in Chile on a sample with a high level of education (Delgado et al., 2017). However, the Mexican authors (Aguilar-Navarro et al., 2017), who assessed a population with an education level similar to that of the Chilean sample, found no significant effect of age or education level, which differs from most results reported in the literature. A different study evaluated Brazilian patients with Parkinson's disease, 65% of whom had less than 8 years of education, as part of the LARGE-PD study. In that sample, there was a significant floor for some of the MoCA subtests (Tumas et al., 2016). For the attention subtest, which requires individuals to count backwards from 100, subtracting seven each time, most of the patients had failed by the fifth subtraction. Similar results were found for the repetition, verbal fluency, and abstraction subtests (Tumas et al., 2016). Moreover, in a sample of patients from the Andean region of Colombia, where the average education level was 4.8 years and where 8% of the people were illiterate, the MoCA subtests that were least biased by education were orientation, delayed recall, and repetition. In contrast, the part B subset of the Trail Making test was correctly performed by only 37% of people with an elementary-level education, and <30% of individuals with an elementary-level education and 7% of illiterate individuals correctly completed cube drawing (Gómez et al., 2013). Similarly, studies using MoCA in populations of Brazilian (Apolinario et al., 2018), Turkish (Yancar and Öscan, 2015), and Chinese (Zhang et al., 2019) origin have reported the influence of education level on MoCA cut-off points. A systematic review on the cultural validity of MoCA (O'Driscoll and Shaikh, 2017) and a critical review on BCS for older adults with low levels of education (Tavares-Júnior et al., 2019) suggest different cut-off points of MoCA according to education level. In this sense, taking into account the high proportion of people with low education and illiteracy in Latin America (UNESCO, 2015, 2017), certain MoCA tasks (drawing of the cube, denomination of dromedary and rhinoceros, and subtract backwards by seven from 100) could not be completed easily, increasing the real suspicion of cases with cognitive impairment. Also, it has been noted that MoCA cognitive domains reflect an educational gradient, including some form of language that might be primarily developed through schooling (Yancar and Öscan, 2015). Different mechanisms have been suggested to explain the relationship between education and cognition. It has been suggested that education may be a marker of other factors associated with cognition, including lower brain reserve may be related to low education.

A major strength of our study was that we used LA databases, including LILACS and SciELO. As some regional authors do not have access to high-impact journals, systematic reviews and meta-analyses often fail to include studies by these authors (Paddick et al., 2017; De Roeck et al., 2019; Magklara et al., 2019). Another strength of this study was the inclusion criteria and detailed evaluation of the diagnostic accuracy measures, as these elements are often overlooked in other publications (De Roeck et al., 2019; Magklara et al., 2019).

The limitations of this review include the scarcity of studies with sufficient information to discriminate between different types of dementia. The only studies to address different types of dementia were those carried out on IFS in Argentina (Torralva et al., 2009) and Peru (Custodio et al., 2016), which evaluated the capacity of this BCS to distinguish between ADD and behavioral variant FTD (BvFTD), and those on the M@T (Custodio et al., 2014, 2017a), which evaluated the ability of the tool to distinguish between aMCI and early ADD. This limitation is likely related to our inclusion criterion that the BCS administration time be no longer than 15 min, as evaluating different cognitive domains requires additional administration time to establish differential profiles of dementia. Therefore, the capacity of a BCS to discriminate among different types of dementia is questionable (De Roeck et al., 2019). On the other hand, some of the BCS tools only evaluated specific domains, such as episodic memory in the case of the M@T. When used for screening in the clinical context, it is possible that such BCS tests would fail to detect cases in which the initial sign of dementia do not include memory loss, such as, VD or FTD. Moreover, BCS tests that evaluate executive function, such as the IFS, may be ideal for detecting BvFTD and VD (Custodio et al., 2017b) but potentially at the cost of a decreased ability to detect AD. It is likely that cognitive screening tools that require a longer administration time, such as the ACE-R (Torralva et al., 2011; Muñoz-Neira et al., 2012a; Ospina, 2015), might be capable of discriminating among different types of dementia. However, our objective in this review was to evaluate BCS that can be used in a primary care setting.

A second limitation of this review was that we excluded BCSs based on caregiver or informant interviews, as tools such as the general practitioner assessment of cognition (GPCOG), informant questionnaire on cognitive decline in the elderly (IQCODE), Alzheimer disease 8 (AD8), or Pfeffer functional activities questionnaire (PFAQ) may be useful in the clinical setting. This resulted in the exclusion of tools to evaluate functional capacity, which may improve the ability of a test to detect cognitive decline (De Roeck et al., 2019; Magklara et al., 2019). Indeed, in the dementia field, most functional capacity evaluation tools are informant-based questionnaires owing to the frequent coexistence of cognitive decline with anosognosia (Muñoz-Neira et al., 2012b). This point is important, as evaluating instrumental activities of daily living is crucial for differentiating between MCI and dementia (De Roeck et al., 2019).

A third limitation is the inclusion of BCS tools only study in subjects over 50 years, even though there are dementias with an age-at-onset less than 50 years old like the Dominantly Inherited Alzheimer's Disease (DIAD) (McDade et al., 2018). Current evidence suggests that the same BCS are valid tool to diagnosis dementia regardless of aging of onset (Rossor et al., 2010). Nevertheless, it is important to highlight that most of BCS present low sensitivity to detect neurodegenerative disease at a preclinical stage. A final limitation relates to the fact that we have only included publications in Spanish, and probably we have not been able to access native aboriginal populations. In addition, there is the possibility of researchers publishing their findings in non-indexed journals.

In summary, this review showed that the M@T is the only BCS that has been evaluated in a group with a low education level; in LA the MoCA requires cultural adaptations and different cut-off points based on the level of education; the diagnostic validity of the IFS should be evaluated in populations with a low education level; finally, no publication to date has included an illiterate population.

Conclusion

Our review on BCS tests for LA Spanish speaking population showed the need for additional studies in LA with adequate indices on the diagnostic validity of tools to screen for various stages of cognitive decline and different types of dementia. Moreover, the diagnostic accuracy of BCS tools need to be study in different settings (i.e., community, primary care and memory unit). Finally, low-level of education is beside age, one the main risk of dementia (Livingston et al., 2017). Unavailability of BCS properly validate in low -education and illiterate subjects is a strong barrier to diagnosis dementia in this population and there is an urgent need to validate BCS suitable for this population (Ortega et al., 2019).

Author Contributions

NC and AS conceived the study. NC, RM, CA-D, and AS designed the study. RM, CA-D, MM, and LD collected the data. RM, MM, and CA-D organized the database. NC, RM, and AS wrote the first draft of the manuscript. NC, RM, and CA-D wrote sections of the manuscript. All authors contributed to manuscript revision, read, and approved the final version.

Funding

This work was funded by ANID/FONDAP Program Grant 15150012, ANID/FONDEF Grant ID18I10113, and a grant from the Inter-American Development Bank (IADB) (to AS).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

Aguilar-Navarro, S. G., Mimenza-Alvarado, A. J., Palacios-García, A. A., Samudio-Cruz, A., Gutiérrez-Gutiérrez, L. A., and Ávila-Funes, J. A. (2017). Validity and reliability of the Spanish Version of the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) for the detection of cognitive impairment in Mexico. Revista Colombiana Psiquiatria 47, 237–243. doi: 10.1016/j.rcpeng.2018.10.004

Apolinario, D., dos Santos, M. F., Sassaki, E., Pegoraro, F., Pedrini, A. V. A., Cestri, B., et al. (2018). Normative data for the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) and the Memory Index Score (MoCA-MIS) in Brazil: adjusting the nonlinear effects of education with fractional polynomials. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 33, 893–899. doi: 10.1002/gps.4866

Arango-Lasprilla, J. C. (2015). Commonly used neuropsychological tests for spanish speakers: normative data from Latin America. NeuroRehabilitation 37, 489–491. doi: 10.3233/NRE-151276

Bongaarts, J. (2009). Human population growth and the demographic transition. Philos. Trans. Royal Soc. B 364, 2985–2990. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2009.0137

Bravo-Grau, S., and Cruz, Q. J. P. (2015). Estudios de exactitud diagnóstica: Herramientas para su Interpretación. Revista Chilena Radiol. 21, 158–164. doi: 10.4067/S0717-93082015000400007

Brown, J. (2014). The use and misuse of short cognitive tests in the diagnosis of dementia. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 86, 680–685. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2014-309086

Bruno, D., Slachevsky, A., Fiorentino, N., Rueda, D. S., Bruno, G., Tagle, A. R., et al. (2017). Argentinian/Chilean validation of the Spanish-language version of Addenbrooke's Cognitive Examination III for diagnosing dementia. Neurologia. 35:82–88. doi: 10.1016/j.nrl.2017.06.004

Cantor-Nieto, M. I., and Avendaño-Prieto, B. L. (2016). Propriedades psicométricas do teste de rastreio de demências pesoteste em amostras clínica e não clínica de idosos. Acta Colombiana Psicol. 19, 41–52. doi: 10.14718/ACP.2016.19.2.3

Carnero-Pardo, C. (2014). Should the mini-mental state examination be retired? Neurología 29, 473–481. doi: 10.1016/j.nrleng.2013.07.005

Chong, S. A., Abdin, E., Vaingankar, J., Ng, L. L., and Subramaniam, M. (2016). Diagnosis of dementia by medical practitioners: a national study among older adults in Singapore. Aging Mental Health 20, 1271–1276. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2015.1074160

Custodio, N., Becerra-Becerra, Y., Cruzado, L., Castro-Suárez, S., Montesinos, R., Bardales, Y., et al. (2018a). Nivel de conocimientos sobre demencia frontotemporal en una muestra de médicos que evalúan regularmente a pacientes con demencia en Lima-Perú. Rev Chil Neuro-Psiquiat 56, 77–88. doi: 10.4067/s0717-92272018000200077

Custodio, N., García, A., Montesinos, R., Lira, D., and Bendezú, L. (2011). Validation of the clock drawing test—Manos version—As a screening test for detection of dementia in older persons of lima; Peru. Revista Peruana Medicina Exp. Salud Publica 28, 29–34. doi: 10.1590/S1726-46342011000100005

Custodio, N., Herrera-Perez, E., Lira, D., Roca, M., Manes, F., Báez, S., et al. (2016). Evaluation of the INECO Frontal Screening and the Frontal Assessment Battery in Peruvian patients with Alzheimer's disease and behavioral variant Frontotemporal dementia. ENeurologicalSci 5:1. doi: 10.1016/j.ensci.2016.11.001

Custodio, N., Lira, D., Herrera-Perez, E., Montesinos, R., Castro-Suarez, S., Cuenca-Alfaro, J., et al. (2017a). Memory alteration test to detect amnestic mild cognitive impairment and early Alzheimer's dementia in population with low educational level. Front. Aging Neurosci. 9:278. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2017.00278

Custodio, N., Lira, D., Herrera-Perez, E., Nuñez del Prado, L., Parodi, J., Guevara-Silva, E., et al. (2014). The memory alteration test discriminates between cognitively healthy status, mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer's disease. Dementia Geriatric Cognitive Disord. Extra 4, 314–321. doi: 10.1159/000365280

Custodio, N., Lira, D., Montesinos, R., Gleichgerrcht, E., and Manes, F. (2012). Utilidad del Addenbrooke' s Cognitive Examination versión en español en pacientes peruanos con enfermedad de Alzheimer y demencia frontotemporal. Rev. Arg. de Psiquiat XXIII, 165–172. Availabe online at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/233397502_Usefulness_of_the_Addenbrooke's_Cognitive_Examination_Spanish_version_in_Peruvian_patients_with_Alzheimer's_disease_and_Frontotemporal_Dementia

Custodio, N., Montesinos, R., and Alarcón, J. (2018b). Evolución histórica del concepto y criterios actuales para el diagnóstico de demencia. Revista Neuro-Psiquiatria 81, 165–179. doi: 10.20453/rnp.v81i4.3438

Custodio, N., Montesinos, R., Lira, D., Herrera-Perez, E., Bardales, Y., and Valeriano-Lorenzo, L. (2017b). Evolution of short cognitive test performance in stroke patients with vascular cognitive impairment and vascular dementia: baseline evaluation and follow-up. Dementia Neuropsychol. 11:7. doi: 10.1590/1980-57642016dn11-040007

Custodio, N., Wheelock, A., Thumala, D., and Slachevsky, A. (2017c). Dementia in Latin America: epidemiological evidence and implications for public policy. Front. Aging Neurosci. 9:221. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2017.00221

De Beaman, S. R., Beaman, P. E., Garcia-Peña, C., Villa, M. A., Heres, J., Córdova, A., et al. (2004). Validation of a modified version of the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) in Spanish. Aging Neuropsychol. Cognit. 11, 1–11. doi: 10.1076/anec.11.1.1.29366

De Roeck, E. E., De Deyn, P. P., Dierckx, E., and Engelborghs, S. (2019). Brief cognitive screening instruments for early detection of Alzheimer's disease: a systematic review. Alzheimer's Res. Therapy 11, 1–14. doi: 10.1186/s13195-019-0474-3

de Vet, H. C. W., Terwee, C. B., Knol, D. L., and Bouter, L. M. (2006). When to use agreement versus reliability measures. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 59, 1033–1039. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2005.10.015

Delgado Derio, C., Guerrero Bonnet, S., Troncoso Ponce, M., Araneda Yañez, A., Slachevsky Chonchol, A., and Behrens Pellegrino, M. I. (2013). Memory, fluency, and orientation (MEFO): A 5-minute screening test for cognitive decline. Neurología 28, 400–407. doi: 10.1016/j.nrleng.2012.10.001

Delgado, C., Araneda, A., and Behrens, M. I. (2017). Validation of the Spanish-language version of the Montreal Cognitive Assessment test in adults older than 60 years. Neurologia 34, 376–385. doi: 10.1016/j.nrl.2017.01.013

Dua, T., Barbui, C., Clark, N., Fleischmann, A., Poznyak, V., van Ommeren, M., et al. (2011). Evidence-based guidelines for mental, neurological, and substance use disorders in low- and middle-income countries: summary of WHO recommendations. PLoS Med. 8:1122. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001122

Dubois, B., Slachevskya Litvan, I., and Pillon, B. (2000). The FAB. Neurology 55, 1621–1626. doi: 10.1212/WNL.55.11.1621

Fiorentino, N., Gleichgerrcht, E., Roca, M., Cetkovich, M., Manes, F., and Torralva, T. (2013). The INECO Frontal Screening tool differentiates behavioral variant. Dement Neuropsychol. 7, 33–39. doi: 10.1590/S1980-57642013DN70100006

Franco-Marina, F., García-González, J., Wagner-Echeagaray, F., Gallo, J., Ugalde, O., and Sánchez-García, S. (2010). The Mini-mental State Examination revisited: ceiling and floor effects after score adjustment for educational level in an aging Mexican population. Int. Psychogeriatrics 22, 72–81. doi: 10.1017/S1041610209990822

Gil, L., Ruiz De Sánchez, C., Gil, F., Romero, S. J., and Pretelt Burgos, F. (2014). Validation of the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) in Spanish as a screening tool for mild cognitive impairment and mild dementia in patients over 65 years old in Bogotá, Colombia. Int. J. Geriatric Psychiatry 30, 655–662. doi: 10.1002/gps.4199

Gleichgerrcht, E., Flichtentrei, D., and Manes, F. (2011). How much do physicians in latin america know about behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia? J. Mol. Neurosci. 45, 609–617. doi: 10.1007/s12031-011-9556-9

Gómez, F., Zunzunegui, M. V., Lord, C., Alvarado, B., and García, A. (2013). Applicability of the MoCA-S test in populations with little education in Colombia. Int. J. Geriatric Psychiatry 28, 813–820. doi: 10.1002/gps.3885

Herrera-Pérez, E., Custodio, N., Lira, D., Montesinos, R., and Bendezu, L. (2013). Validity of addenbrooke's cognitive examination to discriminate between incipient dementia and depression in elderly patients of a Private Clinic in Lima, Peru. Dementia Geriatric Cognitive Disord. Extra 3, 333–341. doi: 10.1159/000354948

Ihara, M., Okamoto, Y., and Takahashi, R. (2013). Suitability of the montreal cognitive assessment versus the mini-mental state examination in detecting vascular cognitive impairment. J. Stroke Cerebrovasc. Dis. 22, 737–741. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2012.01.001

Ihnen Jory, J., Bruna, A. A., Muñoz-Neira, C., and Slachevsky, A. (2013). Chilean version of the INECO Psychometric properties and diagnostic accuracy. Dementia Neuropsychol. 7, 40–47. doi: 10.1590/S1980-57642013DN70100007

Instituto Nacional de Estadística e Informática. (2018). Perú: Crecimiento y Distribución de la Población, 2017. Lima: PRIMEROS RESULTADOS.

Iturra-mena, A. M. (2007). Adaptation and preliminary validation of a screening test for dementia in Chile: the eurotest. Rev. Chil. Neuro-Psiquiat 45, 296–304. doi: 10.4067/S0717-92272007000400005

Labos, E., Trojanowski, S., and Ruiz, C. (2008). Prueba de recuerdo libre/facilitado con recuerdo inmediato version verbal de la FCSRT-IR * Adaptación y normas en lengua española. Revista Neurol. Argentina 33, 50–66.

Landis, J. R., and Koch, G. G. (1977). The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics 33:159. doi: 10.2307/2529310

Livingston, G., Sommerlad, A., Orgeta, V., Costafreda, S. G., Huntley, J., Ames, D., et al. (2017). Dementia prevention, intervention, and care. Lancet. 390, 2673–734. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31363-6

Maestre, G. E., Mena, L. J., Melgarejo, J. D., Aguirre-Acevedo, D. C., Pino-Ramírez, G., Urribarrí, M., et al. (2018). Incidence of dementia in elderly Latin Americans: results of the Maracaibo aging study. Alzheimer Dementia 14, 140–147. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2017.06.2636

Magklara, E., Stephan, B. C. M., and Robinson, L. (2019). Current approaches to dementia screening and case finding in low- and middle-income countries: research update and recommendations. Int. J. Geriatric Psychiatry 34, 3–7. doi: 10.1002/gps.4969

Mansfield, E., Noble, N., Sanson-Fisher, R., Mazza, D., and Bryant, J. (2019). Primary care physicians' perceived barriers to optimal dementia care: a systematic review. Gerontologist 59, e697–e708. doi: 10.1093/geront/gny067

McDade, E., Wang, G., Gordon, B. A., Hassenstab, J., Benzinger, T. L. S., Buckles, V., et al. (2018). Longitudinal cognitive and biomarker changes in dominantly inherited Alzheimer disease. Neurology 91, e1295–e1306. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000006277

McGraw, K., and Wong, S. (1996). Forming inferences about some intraclass correlation coefficients. Psychol. Methods 1, 30–46. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.1.1.30

Moher, D., Shamseer, L., Clarke, M., Ghersi, D., Liberati, A., Petticrew, M., et al. (2015). Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst. Rev. 4:1. doi: 10.1186/2046-4053-4-1

Muñoz-Neira, C., Henríquez, C. H. F., Josefina Ihnen, J., Mauricio Sánchez, C., Patricia Flores, M., and Slachevsky, C. H. A. (2012a). Propiedades psicométricas y utilidad diagnóstica del Addenbrooke's Cognitive Examination-Revised (ACE-R) en una muestra de ancianos chilenos. Revista Medica Chile 140, 1006–1013. doi: 10.4067/S0034-98872012000800006

Muñoz-Neira, C., López, O. L., Riveros, R., Núñez-Huasaf, J., Flores, P., and Slachevsky, A. (2012b). The technology—activities of daily living questionnaire: a version with a technology-related subscale. Dementia Geriatric Cognitive Disord. 33, 361–371. doi: 10.1159/000338606

Nakamura, A. E., Opaleye, D., Tani, G., and Ferri, C. P. (2015). Dementia underdiagnosis in Brazil. Lancet 385, 418–419. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60153-2

O'Driscoll, C., and Shaikh, M. (2017). Cross cultural applicability of the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA): a systematic review. J. Alzheimer's Dis. 58, 789–801. doi: 10.3233/JAD-161042

Olavarría, L., Mardones, C., Delgado, C., and Andrea, S. C. (2016). Percepción de conocimiento sobre las demencias en profesionales de la salud de Chile. Revista Medica Chile 144, 1365–1368. doi: 10.4067/S0034-98872016001000019

Ortega, L., Aprahamian, I., Borges, M. K., Cacao, J., and de Yassuda, M. S. C. (2019). Screening for Alzheimer's disease in low-educated or illiterate older adults in Brazil: a systematic review. Arq. Neuro-Psiquiatr. 77, 279–288. doi: 10.1590/0004-282x20190024

Oscanoa, T. J., Cieza, E., Parodi, J. F., and Paredes, N. (2016). Evaluación de la prueba de la moneda peruana en el tamizaje de trastorno cognitivo en adultos mayores. Revista Peruana Medicina Experimental Salud Pública 33:67. doi: 10.17843/rpmesp.2016.331.2009

Ospina, N. A. (2015). Adaptación y validaciónn en Colombia del Addenbrooke's Cognitive Examination-Revisado (ACE-R) en pacientes con deterioro cognoscitivo leve y demencia. (Thesis). Available online at: http://www.bdigital.unal.edu.co/46616/ (accessed july 15, 2018).

Ostrosky-Solís, F., López-Arango, G., and Ardila, A. (2000). Sensitivity and specificity of the mini-mental state examination in a Spanish-speaking population. Appl. Neuropsychol. 7, 25–31. doi: 10.1207/S15324826AN0701_4

Paddick, S. M., Gray, W. K., McGuire, J., Richardson, J., Dotchin, C., and Walker, R. W. (2017). Cognitive screening tools for identification of dementia in illiterate and low-educated older adults, a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. Psychogeriatr. 29, 897–929. doi: 10.1017/S1041610216001976

Parra, M. A., Baez, S., Allegri, R., Nitrini, R., Lopera, F., Slachevsky, A., et al. (2018). Dementia in Latin America Assessing the present and envisioning the future. Neurology 90, 222–231. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000004897

Pedraza, O. L., Salazar, A. M., Sierra, F. A., Soler, D., Castro, J., Castillo, P., et al. (2016). Confiabilidad, validez de criterio i discriminante del Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) test, en un grupo de adultos de Bogotá. Acta Médica Colombiana 41, 221–228. doi: 10.36104/amc.2016.693

Pedraza, O. L., Sánchez, E., Plata, S. J., Montalvo, C., Galvis, P., Chiquillo, A., et al. (2014). Puntuaciones del MoCA y el MMSE en pacientes con deterioro cognitivo leve y demencia en una clínica de memoria en Bogotá. Acta Neurol. Colombiana 30, 22–31.

Pereira-Manrique, F., and Reyes, M. F. (2013). Confiabilidad y Validez del Test Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) en población mayor de Bogotá, Colombia. Revista Neuropsicol. Neuropsiquiatría Neurociencias 13, 39–61.

Prince, M., Acosta, D., Ferri, C. P., Guerra, M., Huang, Y., Jacob, K. S., et al. (2011). A brief dementia screener suitable for use by non-specialists in resource poor settings-the cross-cultural derivation and validation of the brief Community Screening Instrument for Dementia. Int. J. Geriatric Psychiatry 26, 899–907. doi: 10.1002/gps.2622

Quiroga, P., Albala, C., and Klaasen, G. (2004). Validación de un test de tamizaje para el diagnóstico de demencia asociada a edad, en Chile Validation of a screening test for age associated cognitive impairment, in Chile. Rev. Méd. Chile 132, 67–478. doi: 10.4067/S0034-98872004000400009

Ramos-Cerqueira, A. T., Torres, A. R., Crepaldi, A. L., Oliveira, N. I., Scazufca, M., Meneses, P. R., et al. (2005). Identification of dementia cases in the community: a Brazilian experience. J AmGeriatr Soc. 53, 1738–1742. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53553.x

Roman, F., Iturry, M., Rojas, G., Buschke, H., and Allegri, R. F. (2016). Validation of the Argentine version of the Memory Binding Test (MBT) for early detection of mild cognitive impairment. Dement Neuropsychol. 10, 217–226. doi: 10.1590/S1980-5764-2016DN1003008

Rosselli, D., Ardila, A., Pradilla, G., Morillo, L., Bautista, L., and Rey, O. (2000). El examen mental abreviado (Mini-Mental State Examination) como prueba de selección para el diagnóstico de demencia: un estudio poblacional colombiano. Neurología 30, 428–432. doi: 10.33588/rn.3005.99125

Rossor, M. N., Fox, N. C., Mummery, C. J., Schott, J. M., and Warren, J. D. (2010). The diagnosis of young-onset dementia. Lancet Neurol. 9, 793–806. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(10)70159-9

Russo, M. J., Iturry, M., Sraka, M. A., Bartoloni, L., Carnero-Pardo, C., and Allegri, R. F. (2014). Diagnostic accuracy of the Phototest for cognitive impairment and dementia in Argentina. Clin. Neuropsycol. 28, 826–840. doi: 10.1080/13854046.2014.928748

Sarasola, D., De Luján-Calcagno, M., Sabe, L., Crivelli, L., Torralva, T., Roca, M., et al. (2005). El Addenbrooke's Cognitive Examination en Español para el diagnóstico de demencia y para la diferenciación entre enfermedad de Alzheimer y demencia frontotemporal. Revista Neurologia 41, 717–721. doi: 10.33588/rn.4112.2004625

Saxena, S., Thornicroft, G., Knapp, M., and Whiteford, H. (2007). Resources for mental health: scarcity, inequity, and inefficiency. Lancet 370, 878–889. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61239-2

Serrani Azcurra, D. J. L. (2013). Spanish translation and validation of an Executive Battery 25 (EB25) and its shortened version (ABE12) for executive dysfunction screening in dementia. Neurologia 28, 457–476. doi: 10.1016/j.nrl.2010.12.020

Streiner, D., and Norman, G. (2003). Health Measurement Scales: A Practical Guide to Their Development and Use, 3rd Edn. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Tavares-Júnior, J. W. L., de Souza, A. C. C., Alves, G. S., Bonfadini Jd, C., Siqueira-Neto, J. I., and Braga-Neto, P. (2019). Cognitive assessment tools for screening older adults with low levels of education: a critical review. Front. Psychiatry 10:878. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00878

Terwee, C. B., Bot, S. D. M., de Boer, M. R., van der Windt, D. A. W. M., Knol, D. L., Dekker, J., et al. (2007). Quality criteria were proposed for measurement properties of health status questionnaires. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 60, 34–42. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2006.03.012

Torralva, T., Roca, M., Gleichgerrcht, E., Bonifacio, A., Raimondi, C., and Manes, F. (2011). Validación de la versión en español del Addenbrooke's Cognitive Examination-Revisado (ACE-R). Neurologia 26, 351–356. doi: 10.1016/j.nrl.2010.10.013

Torralva, T.eresa, Roca, M., Gleichgerrcht, E., López, P., and Manes, F. (2009). INECO Frontal Screening (IFS): a brief, sensitive, and specific tool to assess executive functions in dementia. J. Int. Neuropsychol. Soc. 15, 777–786. doi: 10.1017/S1355617709990415

Tumas, V., Borges, V., Ballalai-Ferraz, H., Zabetian, C., Mata, I. F., Brito, M. M. C., et al. (2016). Some aspects of the validity of the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) for evaluating cognitive impairment in Brazilian patients with Parkinson's disease. Dementia Neuropsychol. 10, 333–338. doi: 10.1590/s1980-5764-2016dn1004013

UNESCO (2015). EDUCATION FOR ALL 2000–2015: Achievements and Challenges (Second). Paris: UNESCO Publishing. Available online at: http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0023/002322/232205e.pdf

UNESCO (2017). Literacy rates continue to rise from one generation to the next. Unesco 45, 1–13. Availabe online at: http://uis.unesco.org/sites/default/files/documents/fs45-literacy-rates-continue-rise-generation-to-next-en-2017.pdf

Velayudhan, L., Ryu, S. H., Raczek, M., Philpot, M., Lindesay, J., Critchfield, M., et al. (2014). Review of brief cognitive tests for patients with suspected dementia. Int. Psychogeriatrics 26, 1247–1262. doi: 10.1017/S1041610214000416

Watson, R., Bryant, J., Sanson-Fisher, R., Mansfield, E., and Evans, T-J. (2018). What is a ‘timely’ diagnosis? Exploring the preferences of Australian health service consumers regarding when a diagnosis of dementia should be disclosed. BMC Health Serv. Res. 18:612. doi: 10.1186/s12913-018-3409-y

Yancar, E., and Öscan, T. (2015). Evaluating the relationship between education level and cognitive impairment with the Montreal Cognitive Assessment Test. Psychogeriatrics 15, 186–190. doi: 10.1111/psyg.12093

Zhang, Y.-R., Ding, Y.-L., Chen, K.-L., Liu, Y., Wei, C., Zhai, T.-t., et al. (2019). The items in the Chinese version of the Montreal Cognitive Assessment basic discriminate among different severities of Alzheimer's disease. BMC Neurol. 19:269. doi: 10.1186/s12883-019-1513-1

Keywords: cognitive screening, dementia, Alzheimer's disease, mild cognitive impairment, MoCA, Latin America

Citation: Custodio N, Duque L, Montesinos R, Alva-Diaz C, Mellado M and Slachevsky A (2020) Systematic Review of the Diagnostic Validity of Brief Cognitive Screenings for Early Dementia Detection in Spanish-Speaking Adults in Latin America. Front. Aging Neurosci. 12:270. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2020.00270

Received: 25 March 2020; Accepted: 04 August 2020;

Published: 04 September 2020.

Edited by:

Johannes Schröder, Heidelberg University, GermanyReviewed by:

Blas Couto, Instituto de Neurología Cognitiva, ArgentinaDiego Salas-Gonzalez, University of Granada, Spain

Diego Castillo-Barnes, University of Granada, Spain, in collaboration with reviewer DS-G

Copyright © 2020 Custodio, Duque, Montesinos, Alva-Diaz, Mellado and Slachevsky. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Nilton Custodio, bmN1c3RvZGlvQGlwbi5wZQ==; Andrea Slachevsky, YW5kcmVhLnNsYWNoZXZza3lAdWNoaWxlLmNs

Nilton Custodio

Nilton Custodio Lissette Duque

Lissette Duque Rosa Montesinos

Rosa Montesinos Carlos Alva-Diaz

Carlos Alva-Diaz Martin Mellado

Martin Mellado Andrea Slachevsky

Andrea Slachevsky