- 1Meakins-Christie Laboratories, Research Institute of the McGill University Health Centre, Montreal, QC, Canada

- 2Department of Microbiology and Immunology, McGill University, Montreal, QC, Canada

- 3Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry, Concordia University, Montreal, QC, Canada

- 4Department of Medicine, McGill University, Montreal, QC, Canada

Stressors and environmental cues shape the physiological state of bacteria, and thus how they subsequently respond to antibiotic toxicity. To understand how superoxide stress can modulate survival to bactericidal antibiotics, we examined the effect of intracellular superoxide generators, paraquat and menadione, on stationary-phase antibiotic tolerance of the opportunistic pathogen, Pseudomonas aeruginosa. We tested how pre-challenge with sublethal paraquat and menadione alters the tolerance to ofloxacin and meropenem in wild-type P. aeruginosa and mutants lacking superoxide dismutase (SOD) activity (sodAB), the paraquat responsive regulator soxR, (p)ppGpp signaling (relA spoT mutant), or the alternative sigma factor rpoS. We confirmed that loss of SOD activity impairs ofloxacin and meropenem tolerance in stationary phase cells, and found that sublethal superoxide generators induce drug tolerance by stimulating SOD activity. This response is rapid, requires de novo protein synthesis, and is RpoS-dependent but does not require (p)ppGpp signaling nor SoxR. We further showed that pre-challenge with sublethal paraquat induces a SOD-dependent reduction in cell-envelope permeability and ofloxacin penetration. Our results highlight a novel mechanism of hormetic protection by superoxide generators, which may have important implications for stress-induced antibiotic tolerance in P. aeruginosa cells.

Introduction

Bacteria can survive the lethal effects of antibiotics through expression of genetically inheritable resistance mechanisms. They also can adopt a transient physiological state of drug tolerance (Levin and Rozen, 2006; Meylan et al., 2018), which is widely observed in slow growing and biofilm bacteria. Such a drug tolerant state likely contributes to chronic infections refractory to antibiotic treatment, particularly those caused by the major human opportunistic pathogen Pseudomonas aeruginosa.

A wide range of physiological, metabolic and environmental stressors can induce drug tolerance and lower antibiotic lethality. For example, nutrient starvation (Nguyen et al., 2011; Bernier et al., 2013), ATP depletion (Conlon et al., 2016), respiratory inhibition (Lobritz et al., 2015), transition to stationary phase (Davey et al., 1988) and hypoxic environments (Walters et al., 2003; Stewart et al., 2015) dampen antibiotic killing, while nutrient utilization that enhance TCA cycle activity and aerobic respiration enhance drug lethality (Allison et al., 2011; Dwyer et al., 2014; Meylan et al., 2017). Our groups and others have previously shown that global stress responses (Chen et al., 2009; Lewis, 2010; Harms et al., 2016), such as those mediated by the alternative sigma factor RpoS (Murakami et al., 2005) and (p)ppGpp signaling (Nguyen et al., 2011), confer multidrug tolerance in P. aeruginosa. As such, the mechanisms of drug tolerance are likely multifactorial, condition specific, and species-specific.

How oxidative stress pathways contribute to bacterial survival when challenged with bactericidal antibiotics remains a complex and incompletely understood question. Superoxide radicals can contribute to cell death by inactivating iron-containing proteins, particularly those harboring [Fe-S] clusters that release Fe 2+ to catalyze the production of highly reactive hydroxyl radicals by Fenton chemistry (Hausladen and Fridovich, 1994; Keyer and Imlay, 1996). While several groups have previously reported that bactericidal antibiotics induce production of reactive oxygen species, including superoxide and hydroxyl radicals, which contribute to their off-target killing mechanism (Dwyer et al., 2007; Grant et al., 2012; Sampson et al., 2012; Imlay, 2013; Van Acker et al., 2016), others have refuted these observations (Keren et al., 2013; Liu and Imlay, 2013). Superoxide stress also induces anti-oxidant defenses such as superoxide dismutases (SOD), which in turn modulate antibiotic lethality as we and others have reported (Bizzini et al., 2009; Hwang et al., 2013; Ladjouzi et al., 2013, 2015; Heindorf et al., 2014; Wang et al., 2014; Martins et al., 2018). We recently demonstrated that induction of SOD activity confers multidrug tolerance to stationary phase P. aeruginosa through alteration of the cell envelope permeability and increased drug accumulation (Martins et al., 2018).

Superoxide-generating compounds, such as paraquat (PQ), menadione (MN) and plumbagin, increase intracellular superoxide levels. Although they can cause superoxide mediated damage, and are thus expected to amplify cell death, they have also been reported to reduce antibiotic susceptibility and mitigate killing in some studies (Wu et al., 2012; Mosel et al., 2013). Superoxide-generating compounds induce gene expression through activation of the transcription factors SoxR, and OxyR (Ochsner et al., 2000; Blanchard et al., 2007), including genes encoding drug efflux systems in Escherichia coli, P. aeruginosa, and other species (Miller et al., 1994; Pérez et al., 2012; Mosel et al., 2013; Blanco et al., 2017). However, how superoxide stress alters the susceptibility of P. aeruginosa to antibiotic lethality remains poorly understood. In this study, we report that sublethal PQ and MN confer antibiotic tolerance in stationary phase P. aeruginosa cells by inducing SOD activity. This SOD response is rapid, RpoS-dependent but (p)ppGpp- and SoxR-independent, leading to a reduction in envelope permeability and drug accumulation, and diminished killing by ofloxacin (a quinolone) and meropenem (a beta-lactam) in stationary phase cells.

Materials and Methods

Bacterial Strains and Culture Conditions

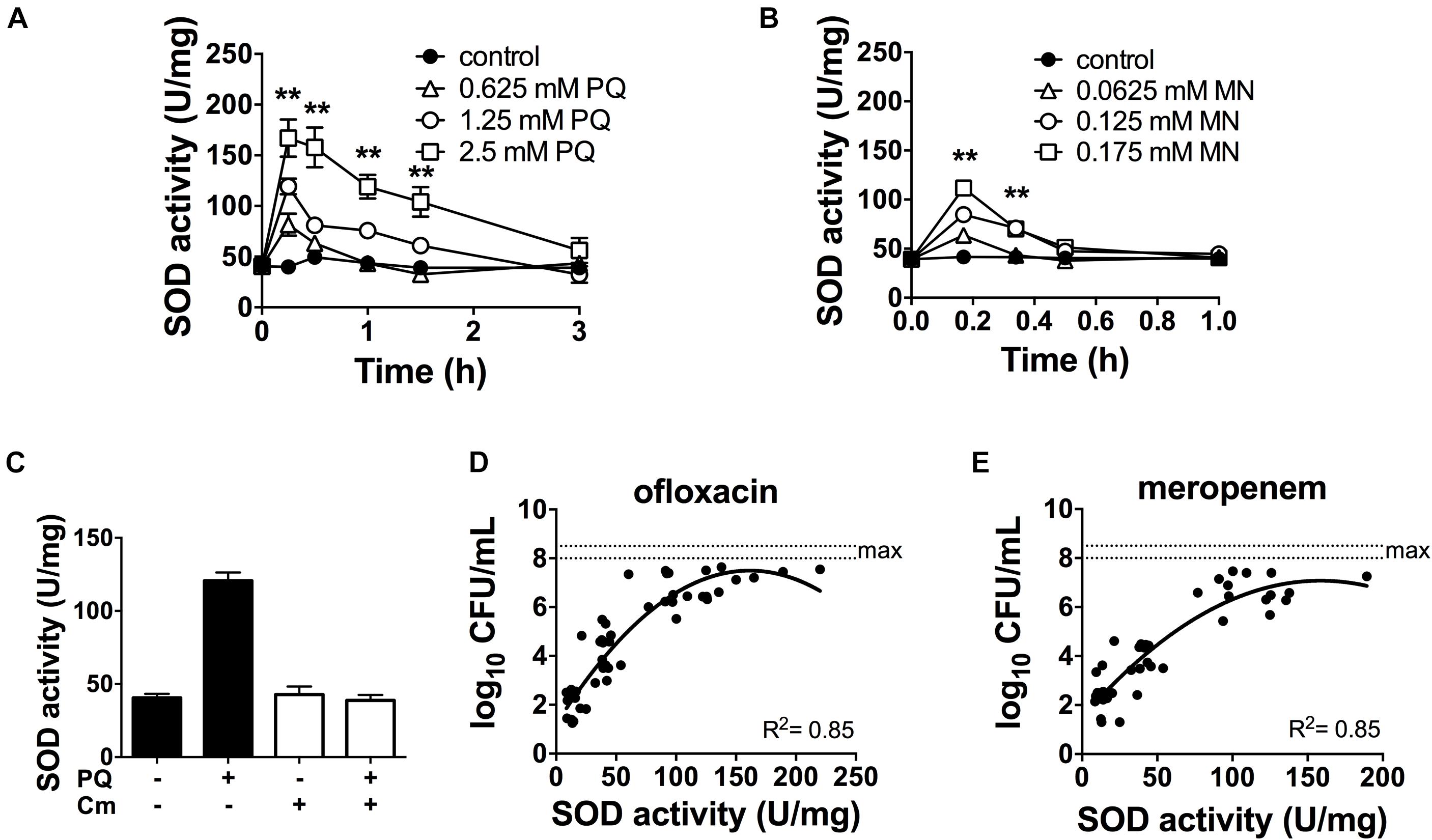

The bacterial strains used in this study are listed in Table 1. All Pseudomonas aeruginosa mutants are derived from the parental wild-type (WT) strain PAO1. The ΔsoxR mutant harboring an unmarked soxR deletion was constructed by allelic exchange using the plasmid pSMV10-ΔsoxR (Dietrich et al., 2006). Merodiploids were selected for gentamicin resistance, followed by counterselection on 15% sucrose and confirmation of the mutation by PCR and sequencing. The sodAB mutant was generated by homologous recombination of the sodB mutation into a sodA mutant using genomic DNA from the sodB mutant (Iiyama et al., 2007), and selection with 90 μg/mL tetracycline and 75 μg/mL gentamicin.

All bacterial cultures were grown in LB Miller liquid medium (wt/v 1% tryptone, 0.5% yeast extract and 1% NaCl, Difco) or 1.5% agar (wt/v). Single colonies grown overnight on LB agar plates from glycerol stocks were picked to inoculate starter cultures (5 mL LB in 25 mL slanted tubes), grown for 8 h, then sub-cultured to an initial OD600 = 0.05 and grown to exponential (2 h, OD600 = 0.2) or late-stationary phase (16 h) in 15 mL LB in 150 mL flasks. All liquid cultures were grown at 37°C with shaking at 250 rpm. In order to generate a robust SOD induction in response to sublethal PQ and MN challenge, stationary phase cultures were diluted 10-fold in their own spent medium (without new nutrients) to OD600 = 0.3, namely filter sterilized (0.22 μm filters) supernatants of the same stationary phase cultures, prior to PQ or MN challenge. To induce katA expression from cells transformed with the pBAD-katA construct, 2% (w/v) L-arabinose (Sigma, #A3256) was added. Gentamicin 75 μg/mL (Sigma #G1264) and tetracycline 50 μg/mL (Sigma #T6660) were used for selection where appropriate.

Paraquat (PQ) and Menadione (MN) Challenge

After 16 h growth, stationary phase cells were diluted 10-fold (final OD600 ∼0.3) in their spent culture medium unless otherwise specified. Cells were transferred to 96-well plates and incubated with sublethal concentrations of the superoxide generators PQ (Sigma #856177) or MN (Sigma #M5625) at 37°C with shaking at 250 rpm. Unless otherwise specified, cells were challenged 1.25 mM PQ, 0.175 mM MN or an equivalent volume of the vehicle (MilliQ H2O for PQ or DMSO for MN) for 20 min before the SOD activity was assayed, or before antibiotics were added for the antibiotic killing assays.

SOD and Catalase Activity Assay

Cells from ∼10 mL of diluted stationary phase cultures (OD600 = 0.3) pre-challenged with PQ, MN or vehicle control, were pelleted by centrifugation at 10,000 × g for 5 min at room temperature, washed twice with phosphate buffered saline (PBS), resuspended in 0.25 mL PBS (10 mM sodium phosphate, 150 mM NaCl, pH 7.4) and lysed by sonication on ice (100 W, 6 × 10 s cycles on ice). The lysates were spun at 12,000 × g for 5 min to remove cell debris; the supernatants containing soluble proteins were collected and assayed for total protein (Bio-Rad Bradford assay), SOD or catalase activity.

SOD activity was assayed as done previously (Martins et al., 2018). Briefly, 2.5–10 μL of soluble protein extracts (5–20 μg in the final assay) were added to a solution containing 50 mM potassium phosphate (KPi) buffer (pH 7.5), 30 μM horse heart ferricytochrome c (Sigma #C6749) and 100 μM xanthine (Sigma #X0626). The assay was started by the addition of 0.25 μg/mL xanthine oxidase (Sigma #X4875), and reduction of ferri- to ferrocytochrome c was measured via absorbance at 550 nm (Δε550 = 19.6 mM–1 cm–1) in a 96-well plate reader (Tecan Infinite M1000). One unit of specific SOD activity per mg of protein (U/mg) inhibits the rate of ferricytochrome c reduction by 50%. Catalase activity was assayed as done previously (Martins et al., 2018). Briefly, 25–150 μL soluble protein extract (0.5–10 μg in the final assay) was added to 1.0 mL of 20 mM H2O2 in 50 mM KPi and H2O2 decomposition was monitored via absorbance at 240 nm (ε240 = 43.6 M–1cm–1) (Beers and Sizer, 1952). One unit of catalase activity catalyzes the degradation of 1 μmol of H2O2 per min (Beers and Sizer, 1952; Martins and English, 2014).

Antibiotic Killing Assays

Stationary phase cells were diluted 10-fold in their spent medium, pre-challenged with PQ or MN (where indicated) then transferred to 96-well plates (200 μL final volume) for challenge with 5 μg/mL ofloxacin (Sigma #O8757) or 500 μg/mL meropenem (Sigma #M2574) at 37°C with shaking at 250 rpm. At specific time points, 25 μL was removed, mixed with an equal volume of activated charcoal (25 mg/mL in PBS, Sigma #05105) to bind the residual antibiotic, serially diluted in sterile PBS and plated on LB agar plates for counting of colony forming units (CFU) after overnight growth at 37°C. The vehicles (50 μM aqueous NaOH for ofloxacin, MilliQ H2O for meropenem) were used as controls.

Inhibition of De Novo Protein Synthesis

Stationary phase cells were diluted 10-fold in their spent medium and treated with 500 μg/mL chloramphenicol (∼10× the minimal inhibitory concentration) for 1 h to inhibit de novo protein synthesis. Cells were then challenged with 1.25 mM PQ for 20 min before harvest to prepare the soluble protein extracts for SOD activity assays. To validate the inhibition of de novo protein synthesis, WT cells expressing an arabinose-inducible katA construct (pBAD-katA) or a control vector were grown to stationary phase, diluted 10-fold in their own spent medium and incubated with ± 2% L-arabinose (wt/v) ± 500 μg/mL chloramphenicol. Soluble-protein extracts were prepared 1.25 h later for measurement of catalase activity. All incubations were done at 37°C with shaking at 250 rpm.

Ethidium Bromide (EtBr) and Dihydroethidium (DHE) Staining

EtBr internalization is an indicator of envelope permeability (Ocaktan et al., 1997), whereas DHE staining reports on relative intracellular superoxide levels (Lee K. et al., 2009). Staining was carried out as described before with minor modifications (Martins et al., 2018). Where indicated, stationary phase cultures were pre-challenged with PQ or MN as described above, and without washing, cells were stained with 15 μM EtBr (Sigma #E7637) or 15 μM DHE (Thermo Fisher Scientific #D11347) for 1 h at room temperature in the dark without shaking. Since they are substrates for efflux pumps, EtBr and DHE staining was carried out in the presence of 100 μM carbonyl cyanide m-chlorophenyl hydrazine (CCCP, Sigma #C2759), a protonophore that inactivates H+-dependent efflux systems. Stained cells were fixed with 4% formalin (v/v) and analyzed by flow cytometry (BD Accuri C6 flow cytometer, BD Biosciences). Relative fluorescence units of individual bacterial cells were determined at Ex/Em 490/580 nm for EtBr and the DHE superoxide-reaction products (namely, 2-hydroxyethidium), and the median fluorescence intensity (MFI) of 10,000 cells was reported for each sample. To estimate superoxide levels, we calculated the MFI ratio of DHE/EtBr fluorescence in each sample to correct for probe loading (Martins et al., 2018).

Efflux Pump Activity

The relative H+-dependent efflux activity was estimated from the ratio of EtBr MFI in the presence or absence of CCCP (+CCCP/-CCCP ratio) under the specified conditions. Stationary phase cells were stained with 15 μM EtBr with or without 100 μM CCCP for 1 h at room temperature in the dark without shaking. EtBr fluorescence was measured by flow cytometry as above.

Ofloxacin Internalization Assay

Ofloxacin internalization was assessed by measuring intracellular drug levels in stationary phase WT cells. Briefly, stationary phase cells were diluted to OD600 0.5 in their spent media, and pre-challenged with 1.25 mM paraquat or H2O (control) for 20 min, then incubated for 1 h with 0.5 μg/mL ofloxacin, a sublethal concentration chosen to cause no cell death during the incubation period. Cells were harvested by centrifugation, washed once in 10 mL PBS and resuspended in 250 μL ddH2O to which an equal volume of methanol was added to lyse cells and extract ofloxacin. Samples were vortexed vigorously for 2 min at room temperature and centrifuged twice (14,000 × g for 20 min) to remove cell debris. The supernatant was collected and stored at −20°C until analyzed.

Quantification of ofloxacin was performed by liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC/MS) using multiple reaction monitoring in positive mode on a triple quadrupole MS system (EVOQ Elite, Bruker) coupled with an ultrahigh-performance liquid chromatography (LC) pump (Advance, Bruker) and a reversed-phase Agilent Zorbax Eclipse Plus C18 column (2.1 × 50 mm, 1.8 μm; P.N. 959757-902). Mobile phases were water with 0.1% formic acid (A) and acetonitrile with 0.1% formic acid (B). 10 μL samples were injected and ofloxacin was eluted at 2.53 min with the following LC conditions: 0–1 min at 5% B, from 1–6 min with gradient up to 95% B, followed by a plateau at 95% for 2 min, and back to 5% B at 8.1 min until 10 min, with a column temperature set at 40°C and flow rate at 0.4 mL/min. Two mass transitions were followed for ofloxacin 362.0 → 318.0 (CE 17 eV), 362.0 → 260.0 (CE 25 eV). The lower limit of detection (LOD 5 pg/mL) and calibration curve (range 15.5–1,000 pg/mL were established using ofloxacin standards (>99%; Sigma-Aldrich #O8757). The relative ofloxacin concentration was calculated as area under the curve (AUC) and the mean of three technical replicates was reported for each sample.

Statistical Analyses

Results were pooled from at least two independent experiments, each performed with at least three biological replicates as indicated. Two-tailed Student’s t-test was used to compare two conditions and one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Tukey multi-comparison post-test was used for comparison between three or more conditions. The correlations between SOD activity and survival to antibiotic challenge were established using non-linear regression (second order polynomial). P ≤ 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were done using the Prism 7 software (GraphPad, CA, United States).

Results

The sodAB Mutant Is Highly Impaired for Antibiotic Tolerance in Stationary Phase P. aeruginosa

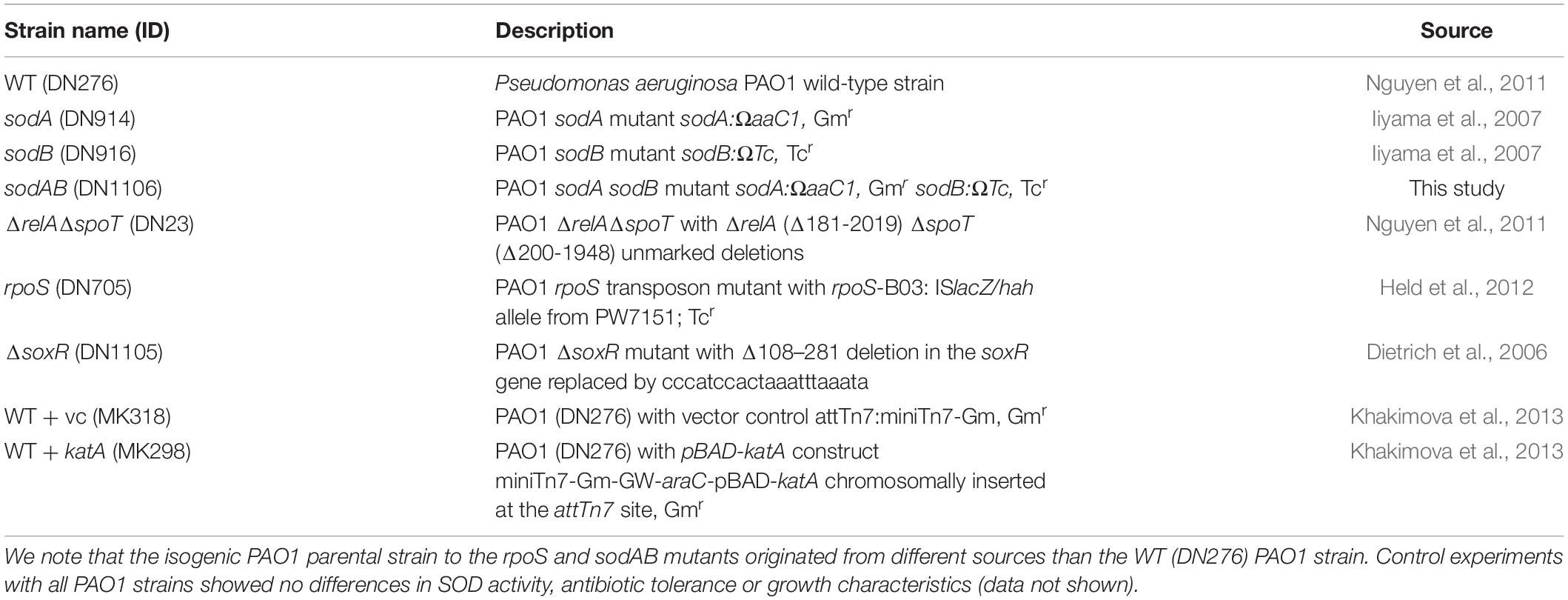

We previously reported that inactivation of (p)ppGpp signaling leads to impaired SOD expression and activity, and that SODs confer multidrug tolerance in stationary phase P. aeruginosa (Martins et al., 2018). P. aeruginosa encodes two different SODs, SodA and SodB. The Fe-cofactored SodB is most abundant in iron replete conditions, while the Mn-cofactored SodA is only expressed under iron limitation or in the absence of SodB (Hassett et al., 1995, 1996). Since the sodB mutant retains 10–15% of the SOD activity of WT cells in stationary phase (Hassett et al., 1995; Martins et al., 2018), we proceeded to characterize the sodAB mutant where both sodA and sodB genes are inactivated (Iiyama et al., 2007). As expected, the sodAB mutant exhibited no detectable SOD activity (Figure 1A) and elevated intracellular superoxide levels as indicated from its DHE/EtBr fluorescence ratio (Figure 1B). Furthermore, stationary phase sodAB cells display ∼3-log10 greater killing by ofloxacin (Figure 1C) and meropenem (Figure 1D) than the WT strain. No difference in antibiotic killing was observed between these two strains during the exponential growth phase (Supplementary Figure S1), which further supports our recent finding that SODs are required specifically for stationary phase antibiotic tolerance (Martins et al., 2018).

Figure 1. Loss of SOD activity impairs drug tolerance in stationary-phase Pseudomonas aeruginosa. (A) SOD activity, (B) relative intracellular superoxide levels and tolerance to killing with (C) 5 μg/mL ofloxacin or (D) 500 μg/mL meropenem in wild-type (WT) and sodAB cells. Relative intracellular superoxide levels were calculated from the ratio of DHE/EtBr median fluorescence, both measured in the presence of 100 μM CCCP. Note that the data points for WT and sodAB cells without antibiotics overlap in (C,D). Results are shown as mean ± SEM (n = 6). ** for P < 0.01 vs. WT.

Superoxide Generators Induce Antibiotic Tolerance

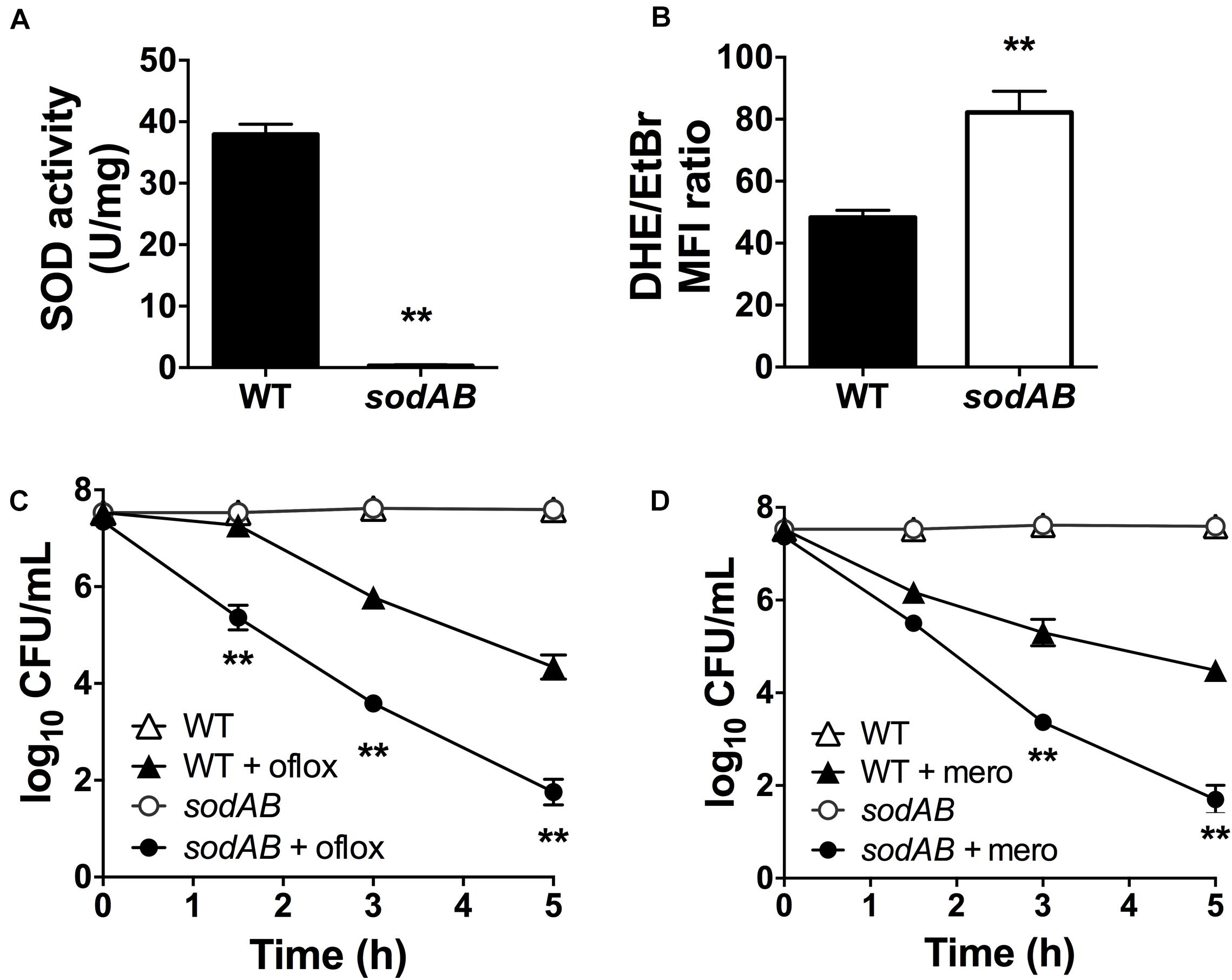

Although superoxide-generating compounds can cause cell toxicity and death, we hypothesized that at sublethal doses they induce adaptive responses that confer protection against antibiotics. To examine this possibility, we selected paraquat (PQ) and menadione (MN), two well-known chemically distinct and cell-permeable superoxide generators. Prior to antibiotic challenge, wild-type (WT) cells were pre-incubated with 1.25 mM PQ or 0.175 mM MN at sublethal concentrations that did not affect bacterial viability (Figures 2A,B). While ofloxacin and meropenem alone caused bacterial killing with 2.5- to 3.0-log10 lower viable counts compared to control conditions, pre-incubation with PQ nearly completely abrogated ofloxacin (Figure 2A) and meropenem (Figure 2B) killing of WT cells. Similar results were observed with sublethal 0.175 mM MN and ofloxacin (Figure 2C) or meropenem (Figure 2D) killing.

Figure 2. Sublethal pre-challenge with PQ and MN enhance drug tolerance. Killing assays for stationary phase WT cells with (A,C) ofloxacin 5 μg/mL and (B,D) 500 μg/mL meropenem ± pre-challenge with (A,B) 1.25 mM PQ or (C,D) 0.175 mM MN for 20 min before addition of antibiotic. Note that the data points for PQ alone and vehicle controls overlap (A,B). Results are shown as mean ± SEM (n = 6). * for P < 0.05 and ** for P < 0.01 vs. antibiotic treatment alone.

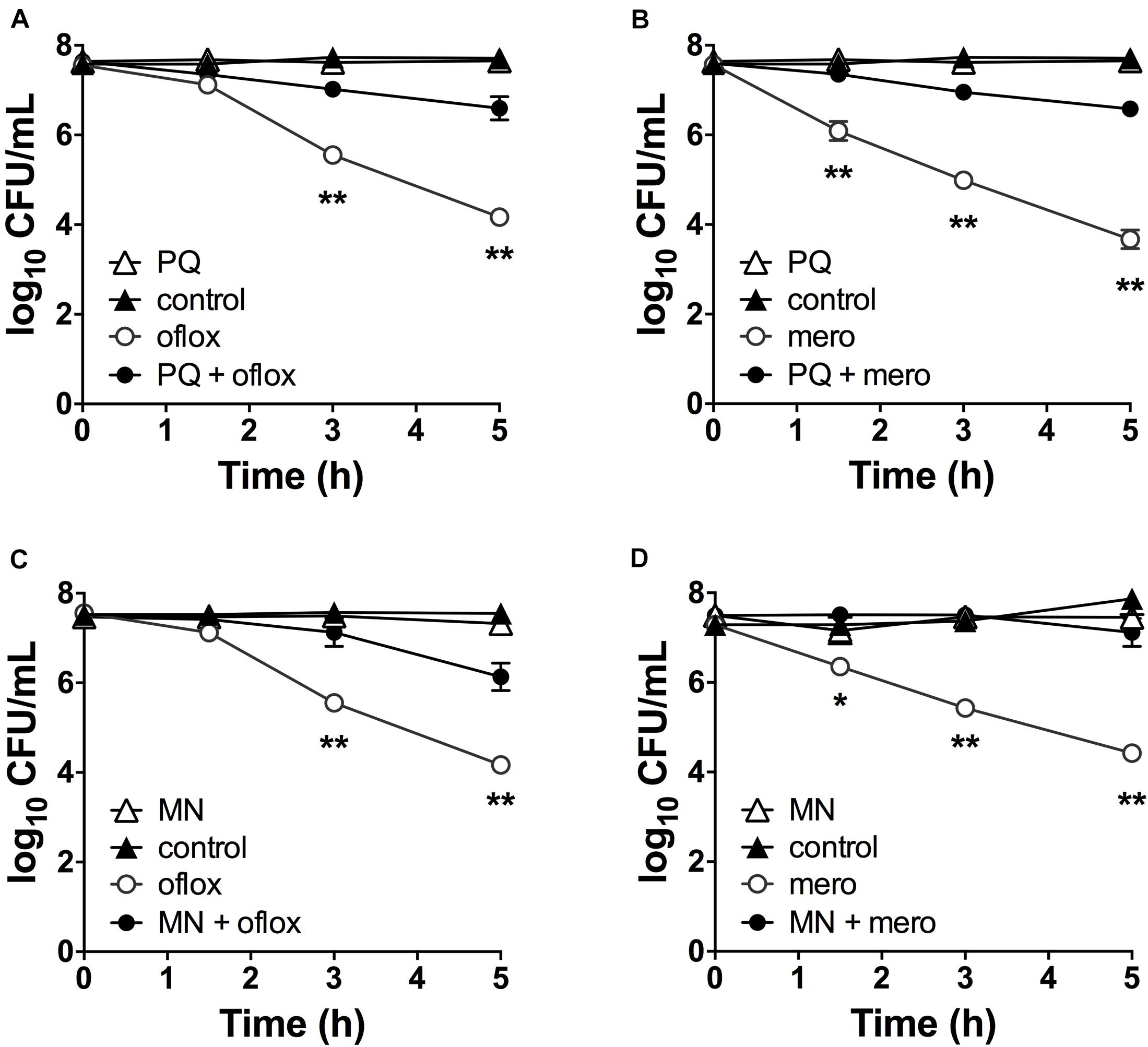

PQ and MN Rapidly Induce SOD Activity and This Requires De Novo Protein Synthesis

Since antibiotic tolerance is impaired upon loss of SODs (Figures 1C,D), and high SOD activity achieved through genetic or chemical complementation confers antibiotic tolerance (Martins et al., 2018), we reasoned that PQ might confer tolerance by inducing SOD activity. As shown in Figure 3A, sublethal concentrations of PQ (0.625–2.5 mM) rapidly induce SOD activity by 1.5- to 4.0-fold in a dose dependent manner. Activity levels reach a maximum within 15 min and return to baseline levels over 1–3 h. We note that, in order to generate a robust SOD induction at low PQ concentrations, stationary phase cultures were diluted in their own spent supernatant to reduce the cell concentration without providing new nutrients or stimulating growth. As a control, we confirmed that diluted and undiluted cells showed a comparable dose-dependent SOD induction in response to PQ (Supplementary Figure S2) as well as PQ-induced ofloxacin tolerance (Supplementary Figure S3). Finally, we also tested MN, a chemically distinct superoxide generator and found that it had similar effects, with a 3-fold induction of SOD activity by 0.175 mM MN within 20-min of challenge (Figure 3B).

Figure 3. SOD activity is induced by PQ and MN, requires de novo protein synthesis and is a determinant of antibiotic tolerance. Dose- and time-response of SOD activity following challenge of stationary phase WT cells with sublethal (A) PQ, (B) MN or vehicle (control). (C) Stationary phase WT cells was treated with 500 μg/mL chloramphenicol (Cm) for 1 h to inhibit de novo protein synthesis, then challenged with 1.25 mM PQ for 20 min before SOD activity was measured. Correlation between SOD activity and (D) ofloxacin and (E) meropenem tolerance was established by simultaneously measuring in the same sample the SOD activity and the bacterial survival following a 5 h challenge with 5 μg/mL ofloxacin or 500 μg/mL meropenem. The max counts (dotted lines) were defined by bacterial counts in untreated controls. Combined data from different strains (WT, ΔrelA spoT, rpoS, and ΔsoxR) in conditions with 1.25 mM PQ, 0.175 mM MN or vector controls are shown and each data point represents one independent replicate (n ≥ 25). The correlation coefficient R2 was calculated using non-linear (second order polynomial) regression. For (A–C), results are shown as mean ± SEM (n = 6) and ** for P < 0.01 vs. untreated WT.

The rapid SOD response following PQ challenge led us to ask if it required de novo protein synthesis. To test this, we inhibited protein synthesis with the bacteriostatic antibiotic chloramphenicol. We first validated this approach using an arabinose-inducible katA expressing construct (pBAD-katA), measured catalase activity in the presence or absence of 500 μg/mL chloramphenicol, and confirmed that pre-treatment with chloramphenicol abrogates the arabinose-dependent induction of catalase activity (Supplementary Figures S4A,B). Next, we demonstrated that PQ-mediated induction of SOD activity is completely abolished by pre-treatment with chloramphenicol (Figure 3C). Whether the induction of SOD activity requires de novo synthesis of SOD itself, or indirectly via another protein remains to be determined. Finally, we noted that a strong correlation between SOD activity and antibiotic tolerance in PQ- and MN-treated cells (Figures 3D,E) is comparable to untreated cells from our previous report (Martins et al., 2018).

PQ-Induced Tolerance Is SOD Dependent and Can Rescue the ΔrelA spoT Mutant

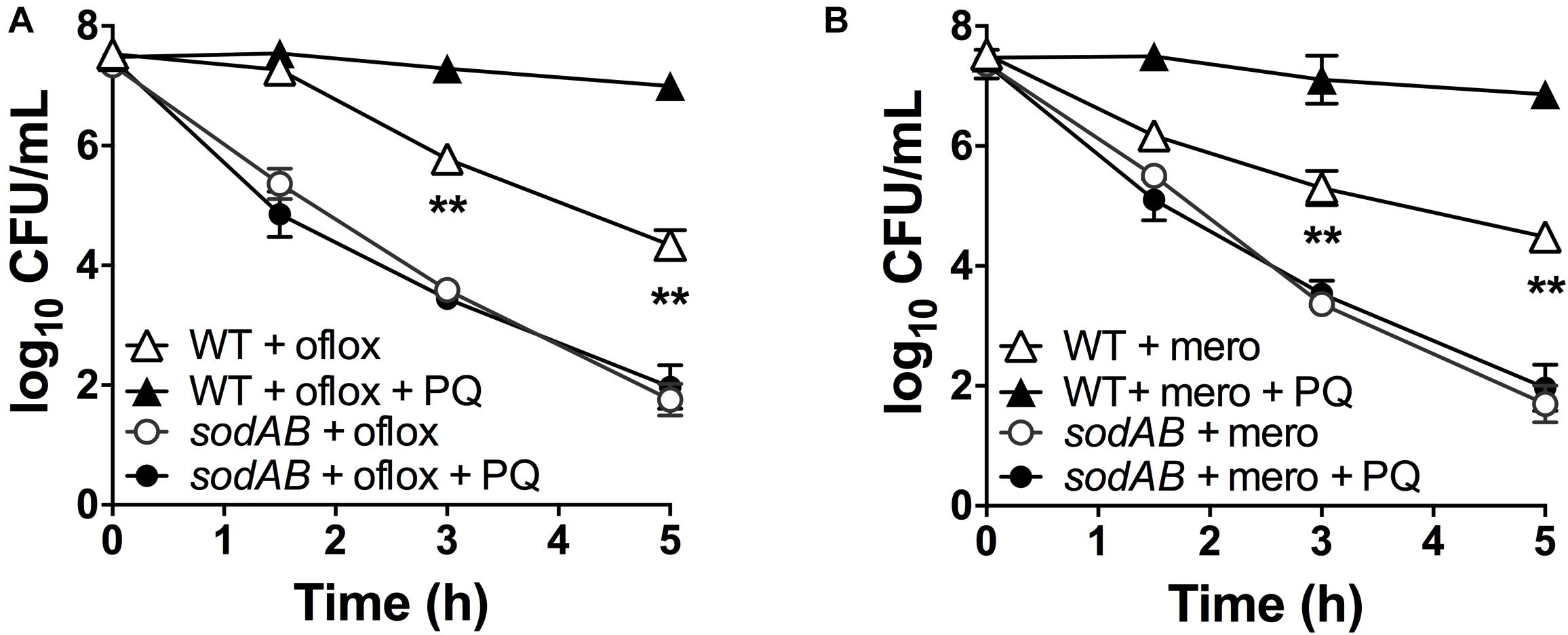

If stimulation of SOD activity is responsible for PQ-mediated antibiotic tolerance, we reasoned that this effect would be abrogated in the sodAB mutant. We thus treated this mutant with 1.25 mM PQ prior to challenge with ofloxacin and meropenem. First, we confirmed that sublethal PQ did not cause any loss of viability in WT or sodAB cells under our experimental conditions (Supplementary Figure S5). Next, we observed that ofloxacin (Figure 4A) and meropenem (Figure 4B) killing of the sodAB mutant was identical in the presence or absence of PQ, demonstrating that PQ-induced tolerance requires sodA and/or sodB.

Figure 4. SOD deletion abrogates PQ-induced tolerance. Stationary phase WT or sodAB mutant cells were pre-challenged with 1.25 mM PQ and assayed 20 min later for killing with (A) 5 μg/mL ofloxacin or (B) 500 μg/mL meropenem. Results are shown as mean ± SEM (n = 6). ** for P < 0.01 vs. the corresponding strains treated with antibiotic alone.

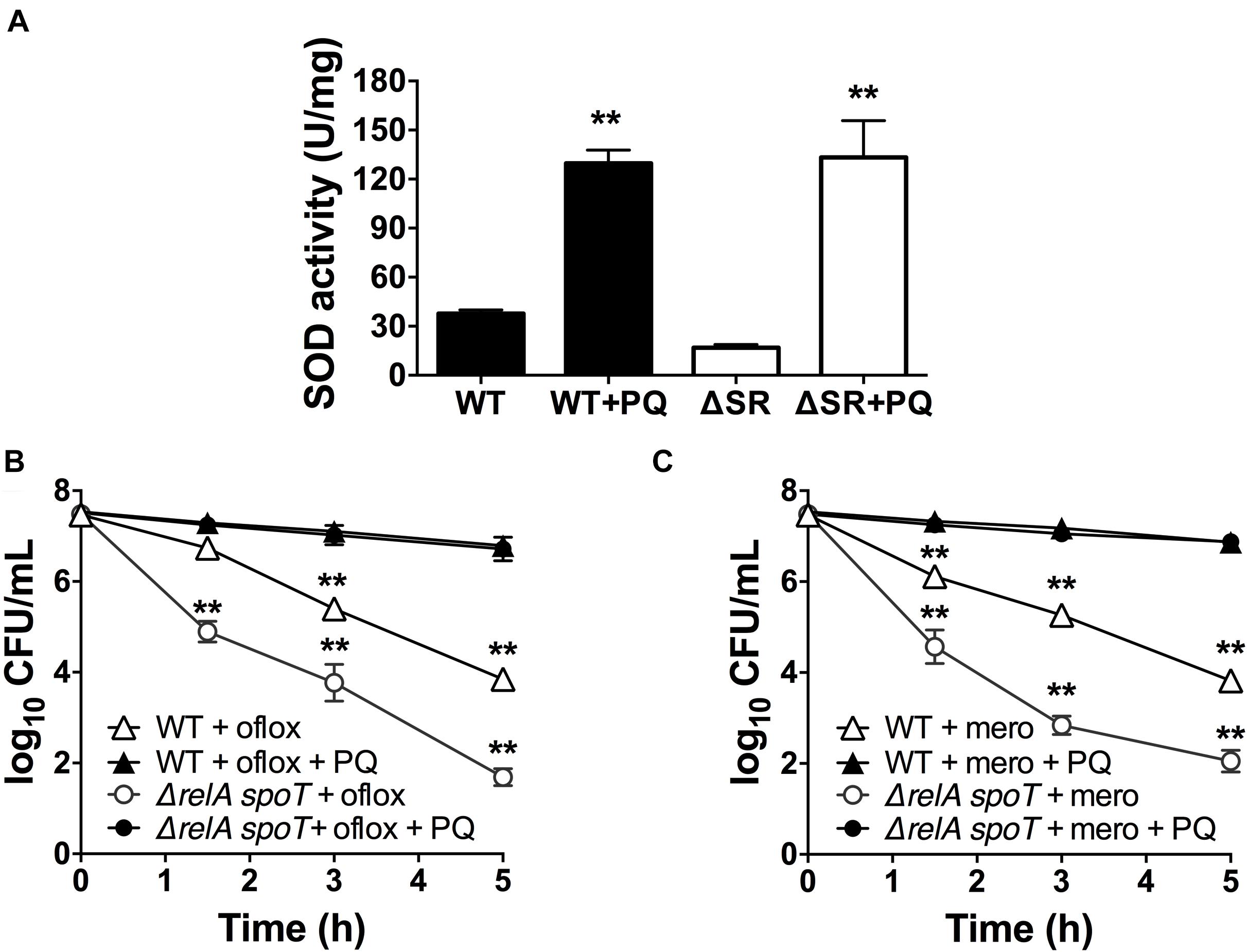

Since loss of (p)ppGpp signaling in the ΔrelA spoT mutant causes a SOD defect and impaired stationary phase antibiotic tolerance, and we previously demonstrated that genetic and chemical SOD complementation rescued the tolerance of the ΔrelA spoT mutant (Nguyen et al., 2011; Martins et al., 2018), we asked whether pre-challenge with sublethal PQ was also sufficient to restore antibiotic tolerance. We first confirmed that the ΔrelA spoT mutant displays ∼3-fold lower SOD activity compared to WT (Figure 5A), and 2- to 3-log10 greater killing by ofloxacin (Figure 5B) and meropenem (Figure 5C). Then, we demonstrated that sublethal PQ does not alter the viability of the ΔrelA spoT mutant (Supplementary Figure S3C) but increases its SOD activity by 8-fold to levels comparable to those in PQ-treated WT cells (Figure 5A). Hence, under our conditions, PQ restored the tolerance of the ΔrelA spoT mutant to WT levels, with a reduction of 5- and 4.8-log10 in killing by ofloxacin (Figure 5B) and meropenem (Figure 5C), respectively. This indicates that the PQ-induced SOD response does not require (p)ppGpp and is sufficient to restore drug tolerance to the ΔrelA spoT mutant.

Figure 5. PQ induces SOD activity and antibiotic tolerance in the ΔrelA spoT mutant. Stationary phase WT or the (p)ppGpp-null ΔrelA spoT cells were pre-challenged with 1.25 mM PQ and assayed 20 min later for (A) SOD activity and killing with (B) 5 μg/mL ofloxacin or (C) 500 μg/mL meropenem. Results are shown as mean ± SEM (n = 6). ** for P < 0.01 vs. untreated controls in (A) and the respective strains treated with antibiotic alone in (B,C).

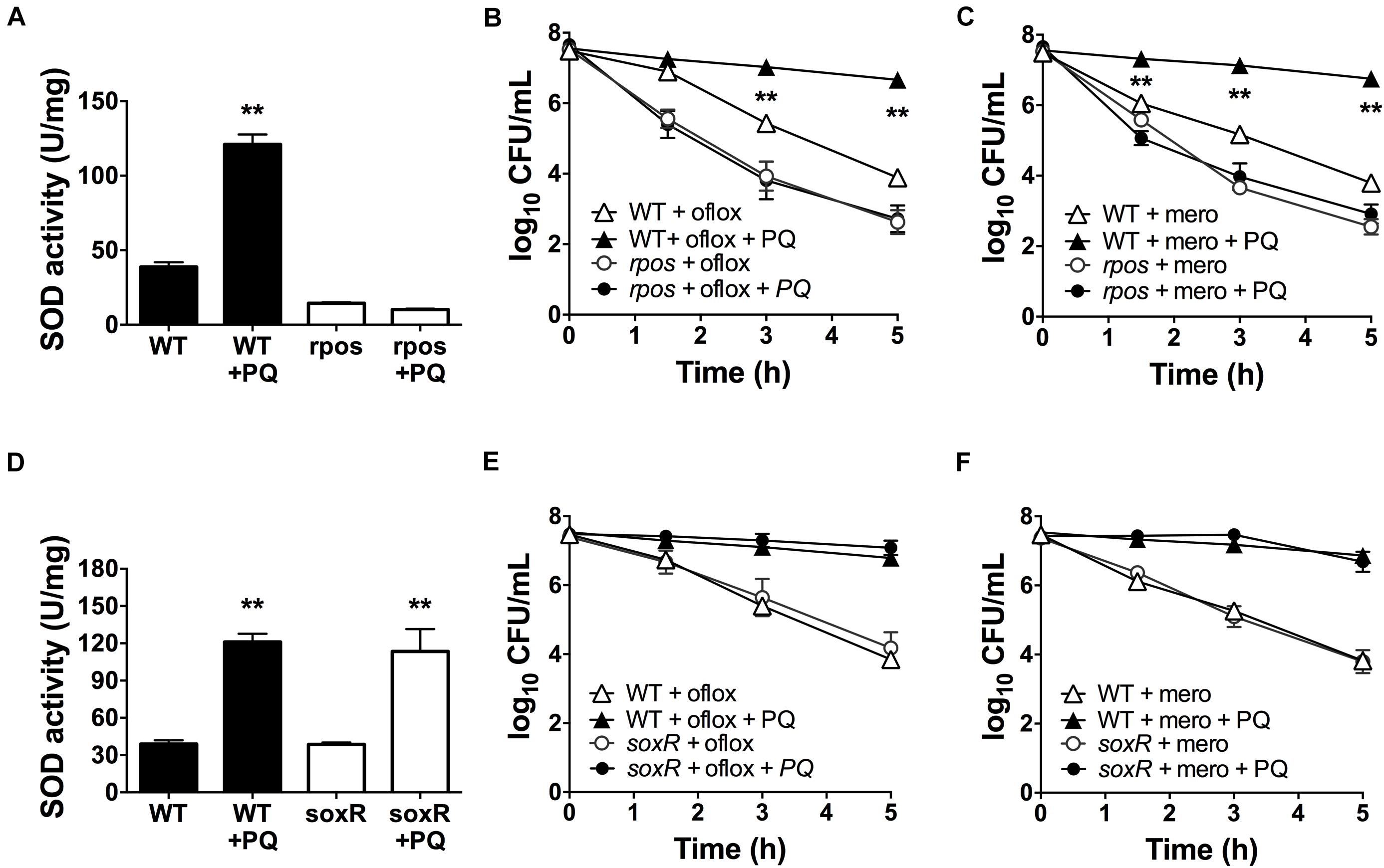

PQ-Induced Antibiotic Tolerance in P. aeruginosa Requires RpoS but Not SoxR

The alternative sigma factor RpoS regulates SOD expression (Martins et al., 2018) and the transcriptional factor SoxR is activated by PQ (Greenberg et al., 1990; Kobayashi and Tagawa, 2004). Thus, we sought to determine whether RpoS and SoxR were involved in the PQ-induced SOD response. First, we tested the rpoS mutant and found that, in contrast to WT cells, sublethal PQ does not induce any SOD activity (Figure 6A) or antibiotic tolerance to ofloxacin (Figure 6B) or meropenem (Figure 6C). In contrast, PQ induces SOD activity (Figure 6D) and drug tolerance (Figures 6E,F) to the same extent in the soxR mutant as in WT cells. As controls, we also confirmed that PQ does not affect the viability of either the soxR or rpoS mutant (Supplementary Figures S3B,D). These results therefore indicate that the PQ-induced responses in stationary phase P. aeruginosa require RpoS but not the PQ-responsive SoxR.

Figure 6. PQ-induced SOD activity and multidrug tolerance requires RpoS but not SoxR. Stationary phase WT, rpoS or ΔsoxR cells were pre-challenged with 1.25 mM PQ and assayed 20 min later for (A,D) SOD activity and killing with (B,E) 5 μg/mL ofloxacin or (C,F) 500 μg/mL meropenem. Note that the data point for rpoS with and without PQ overlap in (B,C). Results are shown as mean ± SEM (n = 6). ** for P < 0.01 vs. untreated controls (for A,D) and WT cells challenged with the same treatment (for B,C,E,F).

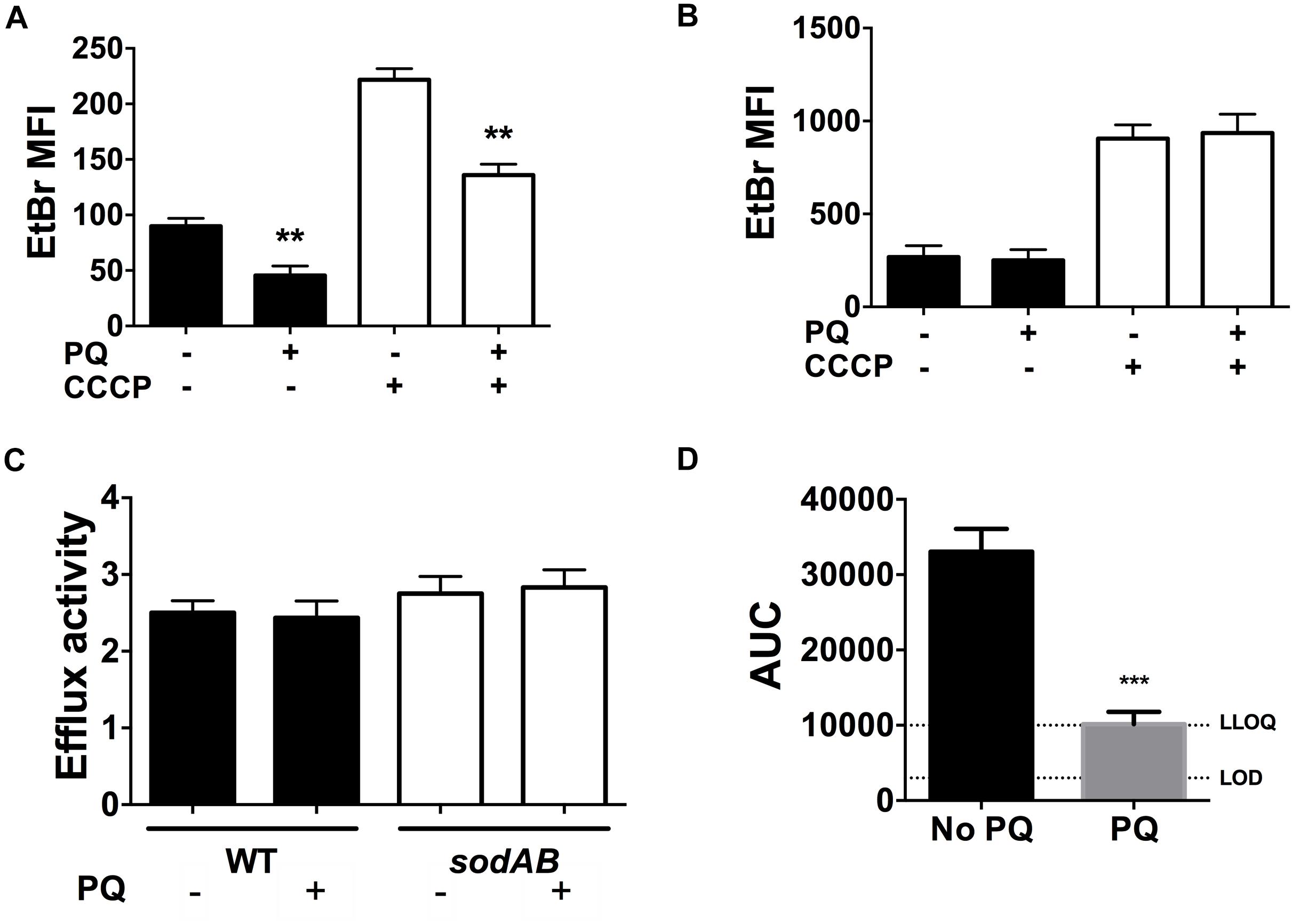

PQ Lowers Envelope Permeability and Ofloxacin Internalization

We recently reported that SODs lower envelope permeability and restrict drug internalization in stationary phase cells (Martins et al., 2018). We thus examined the effect of PQ on envelope permeability by measuring EtBr internalization as a relative measure of envelope permeability. As shown in Figure 7A, EtBr internalization in WT cells is diminished by 2.5-fold after PQ exposure. Since EtBr internalization is a function of both envelope permeability and H+-dependent efflux activity, we also measured EtBr internalization in the presence of the ionophore CCCP to inactivate efflux pumps. As expected, CCCP increases intracellular EtBr fluorescence and this effect was similar for cells pre-challenged with PQ (Figure 7A).

Figure 7. PQ lowers envelope permeability and ofloxacin internalization in a SOD-dependent but efflux independent fashion. EtBr internalization was measured in (A) WT and (B) sodAB stationary phase cells ±1.25 mM PQ pre-challenge and ±100 μM CCCP. (C) Relative efflux activity was estimated by the ratio of EtBr mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) in (+)CCCP to (-)CCCP conditions. (D) Ofloxacin internalization over 1 h was measured by LC/MS in the WT strain ± pre-challenge with 1.25 mM PQ for 20 min. Relative ofloxacin concentrations are reported as area under the curve (AUC), with the lower limit of detection (LOD) and lower limit of quantification (LLOQ) indicated. All results are shown as mean ± SEM (n ≥ 6). ** for P < 0.01 or *** for P < 0.001 vs. the same condition without PQ.

To probe if PQ-induced reduction in envelope permeability is SOD-dependent, we measured EtBr internalization in the sodAB mutant in the presence or absence of PQ. PQ has no effect on EtBr internalization in this mutant (Figure 7B), in contrast to WT cells (Figure 7A), indicating that PQ’s effect on envelope permeability also required SOD activity. We also noted that sodAB mutant cells exhibit significantly higher EtBr fluorescence compared to WT cells whether CCCP is present or absent (Figure 7C). Moreover, the ratio of EtBr fluorescence with and without CCCP, i.e., (+) CCCP/(-) CCCP, an indicator of relative efflux activity, are similar between the WT and sodAB mutant and are not affected by PQ. Together, these results suggest that PQ lowers envelope permeability in an efflux-independent fashion.

Finally, we examined the effect of PQ on the accumulation of ofloxacin in stationary phase WT cells. As shown in Figure 7D, PQ-treated WT cells internalize ∼3.3-fold less ofloxacin than untreated cells, which we attribute to PQ-mediated reduction in envelope permeability.

Discussion

This study expanded on our recent work and further confirmed a key role for SOD activity in mediating multidrug tolerance in stationary phase P. aeruginosa (Martins et al., 2018). We here report that deletion of SOD activity in sodAB cells increases intracellular superoxide levels and antibiotic killing. Pre-challenge with sublethal paraquat (PQ) and menadione (MN) nearly abolishes antibiotic killing of WT cells but this rescue is completely abrogated in the sodAB mutant, indicating that it is SOD-dependent. We determined that RpoS is required PQ-induced increase in SOD activity and antibiotic tolerance, but not SoxR or (p)ppGpp signaling. We previously reported that SODs are positively regulated by (p)ppGpp signaling (Nguyen et al., 2011; Martins et al., 2018) and RpoS (Murakami et al., 2005) under basal growth conditions, and we now found that only RpoS is required for SOD induction under PQ challenge. How RpoS upregulates SOD activity in PQ-challenged P. aeruginosa remains to be determined. We also found no evidence that PQ increased H+-dependent efflux activity in P. aeruginosa. In fact, PQ lowers envelope permeability in a SOD-dependent but efflux-independent fashion. Our current and recently published results show that the SOD-dependent reduction in envelope permeability is associated with a concurrent reduction in internalization of ofloxacin, as well as meropenem (Martins et al., 2018). In the absence of altered drug efflux, this most likely indicates a reduction in drug penetration, although other mechanisms such as drug degradation cannot be excluded. How SOD activity alters envelope permeability and drug penetration remain to be elucidated.

PQ and MN are redox-cycling drugs that generate superoxide radicals, that can directly damage [2Fe-2S] clusters and oxidize NADPH-reduced enzymes, leading to inactivation of dehydratases and NADPH depletion (Gu and Imlay, 2011). PQ induces the expression of several anti-oxidant defenses, including the katB catalase and alkyl hydroperoxidases ahpBCF through an OxyR-dependent response (Ochsner et al., 2000; Hare et al., 2011) as well as sodA and sodB gene expression, leading to increased SOD activity levels in E. coli (Pomposiello et al., 2001; Chen et al., 2006; Hare et al., 2011), and P. aeruginosa (Hare et al., 2011). In E. coli, induction of SodA upon PQ challenge is SoxR dependent (Pomposiello et al., 2001), and RpoS positively regulates sodA expression (Wong et al., 2017). PQ directly activates SoxR through oxidation of its [2Fe-2S] cluster (Gu and Imlay, 2011), which in E. coli, leads to the expression of the transcriptional regulator SoxS, which in turn regulates >100 genes (Pomposiello et al., 2001). In addition to genes involved in superoxide detoxification such as sodA (Greenberg et al., 1990), the E. coli SoxRS regulon includes genes involved in efflux systems (MarR-AB, AcrAB-TolC) that extrude antibiotics (Pomposiello et al., 2001; Wu et al., 2012), membrane porins (MicF and OmpF) implicated in drug influx (Chou et al., 1993), and LPS modification (waaY) (Lee J.H. et al., 2009).

PQ activation of the SoxRS system has been previously linked to antibiotic resistance in E. coli (Miller et al., 1994; Koutsolioutsou et al., 2001, 2005). Miller et al. (1994) reported that PQ dampens the antibacterial activity of enoxacin, a fluoroquinolone, and that this effect requires the superoxide-responsive SoxRS system. Wu et al. (2012) reported that PQ increased fluoroquinolone resistance in E. coli, an effect abrogated in the acrB mutant, suggesting that it may be mediated by the AcrAB-TolC drug efflux system. Interestingly, Mosel et al. (2013) also observed that PQ induced MarA and AcrAB-TolC but deletion of these efflux systems was not sufficient to abrogate the PQ-mediated tolerance to oxolinic acid, kanamycin and ampicillin, indicating that mechanisms other than these efflux systems were involved. Notably, none of these E. coli studies specifically measured envelope permeability nor drug susceptibility in stationary phase cells, and it is uncertain whether the PQ-mediated tolerance observed in our studies shares common mechanisms with the above E. coli studies.

Although P. aeruginosa possesses the superoxide-sensing SoxR, it lacks SoxS (Kobayashi and Tagawa, 2004). Previous studies have also highlighted the divergent roles of SoxR in E. coli and P. aeruginosa (Palma et al., 2005; Dietrich et al., 2008; Singh et al., 2013). Its six gene SoxR regulon includes the mexGHI-ompD efflux system and PA3718, a putative efflux pump, but not sodA nor sodB (Palma et al., 2005). Our demonstration that soxR deletion has no impact on PQ-induced SOD activity nor antibiotic tolerance thus implies that SoxR-regulated efflux systems do not explain PQ-induced antibiotic tolerance. Furthermore, we did not detect significant changes in efflux activity following PQ treatment, thus suggesting that drug efflux is unlikely to be a major mechanism of PQ-induced tolerance.

We recognize that redox-cycling agents such as PQ have pleiotropic effects on gene expression and protein activity, some of which may contribute to the inducible tolerance observed in our conditions. PQ modulates gene expression through SoxR, SoxR-independent responses including OxyR and Fur, or indirectly through perturbation of redox enzymes (Ochsner et al., 2000; Blanchard et al., 2007). In P. aeruginosa, GeneChip experiments by Salunkhe et al. looking at the global gene expression of stationary phase bacteria in response to 0.5 mM PQ only identified 0.5% of ORFs to be differentially expressed. In the P. aeruginosa PAO1 strain, PQ upregulated genes involved in the TCA cycle and acetoin metabolism (e.g., acetyl-coenzyme A synthase acsA, acetoin catabolism acoB), in membrane transport (a putative sodium/solute symporter PA3234, the ABC transporter PA4502-4506), the opdQ and oprC outer membrane porins, and fpr encoding the ferredoxin NADP reductase, while six genes were down-regulated, including PA0105-0108 encoding the cytochrome c oxidase subunits (Salunkhe et al., 2002). PQ and other redox-cycling drugs can also directly oxidize and inactivate catalytic [2Fe-2S] clusters of dehydratases involved in carbon and energy metabolism, leading to disruption in metabolic pathways and respiration (Kuo et al., 1987; Gu and Imlay, 2011). Multiple groups have reported that fluctuations in ATP levels and cellular respiration, central carbon metabolism, and expression of energy generating components are linked to persister formation and antibiotic tolerance (Amato et al., 2014; Lobritz et al., 2015; Orman and Brynildsen, 2015; Meylan et al., 2017; Zalis et al., 2019). It is therefore possible that PQ triggers alterations in central carbon and energy metabolism, which also contribute to ofloxacin and meropenem tolerance in our conditions. We note however that our experiments challenged stationary phase cells with PQ at sublethal concentrations, and the effects such concentrations have on carbon and energy metabolism remain to be determined. Further studies would be required to evaluate these specific mechanisms.

The present observation that SODs mediate the PQ-induced antibiotic tolerance is consistent with our recent report that genetic complementation with sodA and sodB, and chemical complementation with the SOD mimetic Mn(III)-tetrakis-(1-methyl-4-pyridyl) porphyrin pentachloride were also sufficient to restore antibiotic tolerance to the ΔrelA spoT mutant (Martins et al., 2018). These results thus further support the important contribution of SOD activity to antibiotic tolerance, which is growth phase specific and negligible under rapid growth conditions as the absence of SOD activity does not affect antibiotic tolerance in exponentially growing P. aeruginosa. Our results with the sodAB mutant are consistent with studies in Enterococcus faecalis (Bizzini et al., 2009; Ladjouzi et al., 2015), Campylobacter jejuni (Hwang et al., 2013), Acinetobacter baumannii (Heindorf et al., 2014), and E. coli (Dwyer et al., 2007; Wang et al., 2014), where loss of SODs also enhances bactericidal antibiotic killing. These stand in contrast to other studies performed in exponentially growing E. coli reporting that the sodA sodB mutant exhibited similar susceptibility to ampicillin, gentamicin, and norfloxacin killing to the wild-type strain (Wang and Zhao, 2009; Ezraty et al., 2013), and that overexpression of sodA or sodB did not mitigate ampicillin and ofloxacin killing (Orman and Brynildsen, 2016). Why SOD activity is critical to antibiotic survival during stationary phase but not exponential phase remains to be determined. Dukan and Nystrom previously reported that SOD-deficient E. coli mutants exhibit increased protein oxidation only in stationary phase cultures (Dukan and Nystrom, 1999) and proposed that superoxide stress was a hallmark of respiring but non-replicating stationary phase cells (Dukan and Nystrom, 1998).

Several groups have linked antibiotic lethality with ROS mediated toxicity (Dwyer et al., 2007; Grant et al., 2012; Hwang et al., 2013). Hence, reports that PQ and other redox-cycling compounds that generate superoxide radicals actually mitigate antibiotic killing (Wu et al., 2012; Mosel et al., 2013), while superoxide generating nanoparticles (Courtney et al., 2017) and plumbagin enhance isoniazid toxicity in Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Bulatovic et al., 2002) and Mycobacterium smegmatis (Wang et al., 1998), raised questions about the paradoxical role of superoxide stress and SOD in conferring protection and toxicity, respectively, upon antibiotic challenge. Based on our current study, we propose that PQ-induced tolerance has the hallmark of hormesis, a phenomenon in which low doses of a stressor induce a response protective against subsequent high doses of the same or different stressor (Calabrese and Mattson, 2017). In other words, pre-challenge of cells with sublethal PQ or MN induces a SOD response that protects them against an ensuing antibiotic stress. Thus, whether superoxide confers protection or enhances antibiotic lethality will depend on dosage and growth phase. Furthermore, the notion of hormesis and stress-induced tolerance may be relevant beyond sublethal PQ stress, as other physiological cues modulate SOD responses. During in vivo infections where bacteria encounter nutrient limitations, host-derived ROS and other challenges, multiple stress-induced responses may dampen the lethality of antibiotics. For example, Rowe et al. (2020) recently reported that ROS generation within macrophage phagolysosome induced multidrug tolerance in S. aureus. Chemical or metabolic perturbations aimed at potentiating antibiotic lethality should thus be evaluated in physiological contexts relevant to bacteria growing in vivo.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Author Contributions

DM and GM generated and analyzed the data. DM, AME, and DN designed the study and wrote the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

DM acknowledges post-doctoral fellowships from Cystic Fibrosis Canada (3079 to DM) and the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (359359 to DM). We acknowledge funding from the Burroughs Welcome Fund (1006827.01 to DN) and the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (RGPIN-2019-06408 to DN and RGPIN/5032-2018 to AME).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Kazuhiro Iiyama (Kyushu University, Japan) for the sod mutants and Lars Dietrich (Columbia University, United States) for the soxR deletion construct.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmicb.2020.576708/full#supplementary-material

FIGURE S1 | Loss of SOD activity does not affect drug tolerance in exponential phase P. aeruginosa. Wild-type (WT) and sodAB cells were grown to OD600 = 0.2 and challenged with (A) 5 μg/mL ofloxacin and (B) 500 μg/mL meropenem. Note that the data points for WT and sodAB without antibiotics overlap in (A,B). Results are shown as mean ± SD (n = 3).

FIGURE S2 | PQ induction of SOD activity is concentration dependent in both undiluted and diluted cultures of stationary phase P. aeruginosa. Stationary phase WT cells were (A) undiluted or (B) diluted 10-fold in their own culture supernatant prior to challenge with different sublethal concentrations of PQ for 1.5 h, followed by measurement of SOD activity. Results are shown as mean ± SD (n = 3). ∗ for P < 0.05 and ∗∗ for P < 0.01 vs. untreated controls.

FIGURE S3 | Pre-challenge with sublethal PQ confer ofloxacin tolerance to both undiluted and diluted cultures of stationary phase P. aeruginosa. Killing assays with ofloxacin 5 μg/mL in (A) undiluted stationary phase WT cells ± pre-challenge with 7.5 mM PQ or (B) 10-fold diluted stationary phase WT cells with 1.25 mM PQ for 1.5 h before addition of antibiotic. Note that the data points for PQ alone and vehicle controls overlap (A,B). Representative plots are shown as mean ± SD (n = 3). ∗∗ for P < 0.01 vs. antibiotic treatment alone.

FIGURE S4 | Chloramphenicol inhibits de novo catalase activity of WT expressing pBAD-katA. Catalase activity in stationary phase WT cells expressing the (A) pBAD vector control or (B) arabinose inducible catalase construct pBAD-katA. Cells were incubated ±2% wt/v arabinose (Ara) and ± 500 μg/mL chloramphenicol (Cm) for 1.25 h at 37°C with shaking at 250 rpm. Results are shown as mean ± SEM (n ≥ 6). ∗∗ for P < 0.01 vs. the untreated control (-Ara, -Cm).

FIGURE S5 | Challenge with 1.25 mM PQ does not affect bacterial viability. Bacterial viability of stationary phase (A) sodAB, (B) soxR, (C) ΔrelA spot, and (D) rpoS mutant cells challenged with 1.25 mM PQ over 5 h at 37°C with shaking at 250 rpm. Results are shown as mean ± SEM (n = 6).

FIGURE S6 | Bacterial viability remains unchanged during ofloxacin internalization assay. Stationary phase WT cells were pre-challenged with or without 1.25 mM PQ for 20 min, then incubated with 0.5 μg/mL ofloxacin for 1 h. Bacterial viability was measured by CFU count in samples prior to and after ofloxacin incubation for the internalization assay. Results are shown as mean ± SEM (n = 6).

References

Allison, K. R., Brynildsen, M. P., and Collins, J. J. (2011). Metabolite-enabled eradication of bacterial persisters by aminoglycosides. Nature 473, 216–220. doi: 10.1038/nature10069

Amato, S. M., Fazen, C. H., Henry, T. C., Mok, W. W. K., Orman, M. A., Sandvik, E. L., et al. (2014). The role of metabolism in bacterial persistence. Front. Microbiol. 5:70. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2014.00070

Beers, R. F., and Sizer, I. W. (1952). A spectrophotometric method for measuring the breakdown of hydrogen peroxide by catalase. J. Biol. Chem. 195, 133–140.

Bernier, S. P., Lebeaux, D., DeFrancesco, A. S., Valomon, A., Soubigou, G., Coppée, J. Y., et al. (2013). Starvation, together with the SOS response, mediates high biofilm-specific tolerance to the fluoroquinolone ofloxacin. PLoS Genet. 9:e1003144. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003144

Bizzini, A., Zhao, C., Auffray, Y., and Hartke, A. (2009). The Enterococcus faecalis superoxide dismutase is essential for its tolerance to vancomycin and penicillin. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 64, 1196–1202. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkp369

Blanchard, J. L., Wholey, W. Y., Conlon, E. M., and Pomposiello, P. J. (2007). Rapid changes in gene expression dynamics in response to superoxide reveal SoxRS-dependent and independent transcriptional networks. PLoS One 2:e1186. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001186

Blanco, P., Corona, F., Sánchez, M. B., and Martínez, J. L. (2017). Vitamin K 3 induces the expression of the Stenotrophomonas maltophilia SmeVWX multidrug efflux pump. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 61:e02453-16.

Bulatovic, V. M., Wengenack, N. L., Uhl, J. R., Hall, L., Roberts, G. D., and Rusnak, F. (2002). Oxidative stress increases susceptibility of Mycobacterium tuberculosis to isoniazid. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46, 2765–2771. doi: 10.1128/aac.46.9.2765-2771.2002

Calabrese, E. J., and Mattson, M. P. (2017). How does hormesis impact biology, toxicology, and medicine? NPJ Aging Mech. Dis. 3:13.

Chen, J. W., Sun, C. M., Sheng, W. L., Wang, Y. C., and Syu, W. (2006). Expression analysis of up-regulated genes responding to plumbagin in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 188, 456–463. doi: 10.1128/jb.188.2.456-463.2006

Chen, P. R., Nishida, S., Poor, C. B., Cheng, A., Bae, T., Kuechenmeister, L., et al. (2009). A new oxidative sensing and regulation pathway mediated by the MgrA homologue SarZ in Staphylococcus aureus. Mol. Microbiol. 71, 198–211. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2008.06518.x

Chou, J. H., Greenberg, J. T., and Demple, B. (1993). Posttranscriptional repression of Escherichia coli OmpF protein in response to redox stress: positive control of the micF antisense RNA by the soxRS locus. J. Bacteriol. 175, 1026–1031. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.4.1026-1031.1993

Conlon, B. P., Rowe, S. E., Gandt, A. B., Nuxoll, A. S., Donegan, N. P., Zalis, E. A., et al. (2016). Persister formation in Staphylococcus aureus is associated with ATP depletion. Nat. Microbiol. 1:16051.

Courtney, C. M., Goodman, S. M., Nagy, T. A., Levy, M., Bhusal, P., Madinger, N. E., et al. (2017). Potentiating antibiotics in drug-resistant clinical isolates via stimuli-activated superoxide generation. Sci. Adv. 3:e1701776. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.1701776

Davey, P., Barza, M., and Stuart, M. (1988). Tolerance of Pseudomonas aeruginosa to killing by ciprofloxacin, gentamicin and imipenem in vitro and in vivo. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 21, 395–404. doi: 10.1093/jac/21.4.395

Dietrich, L. E. P., Price-Whelan, A., Petersen, A., Whiteley, M., and Newman, D. K. (2006). The phenazine pyocyanin is a terminal signalling factor in the quorum sensing network of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Mol. Microbiol. 61, 1308–1321. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05306.x

Dietrich, L. E. P., Teal, T. K., Price-Whelan, A., and Newman, D. K. (2008). Redox-active antibiotics control gene expression and community behavior in divergent bacteria. Science 321, 1203–1206. doi: 10.1126/science.1160619

Dukan, S., and Nystrom, T. (1998). Bacterial senescence : stasis results in increased and differential oxidation of cytoplasmic proteins leading to developmental induction of the heat shock regulon. Genes Dev. 12, 3431–3441. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.21.3431

Dukan, S., and Nystrom, T. (1999). Oxidative stress defense and deterioration of growth-arrested Escherichia coli cells. J. Biol. Chem. 274, 26027–26032. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.37.26027

Dwyer, D. J., Belenky, P. A., Yang, J. H., MacDonald, I. C., Martell, J. D., Takahashi, N., et al. (2014). Antibiotics induce redox-related physiological alterations as part of their lethality. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 111, E2100–E2109.

Dwyer, D. J., Kohanski, M. A., Hayete, B., and Collins, J. J. (2007). Gyrase inhibitors induce an oxidative damage cellular death pathway in Escherichia coli. Mol. Syst. Biol. 3:91. doi: 10.1038/msb4100135

Ezraty, B., Vergnes, A., Banzhaf, M., Duverger, Y., Huguenot, A., Brochado, A. R., et al. (2013). Fe-S cluster biosynthesis controls uptake of aminoglycosides in a ROS-less death pathway. Science 340, 1583–1587. doi: 10.1126/science.1238328

Grant, S. S., Kaufmann, B. B., Chand, N. S., Haseley, N., and Hung, D. T. (2012). Eradication of bacterial persisters with antibiotic-generated hydroxyl radicals. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109, 12147–12152. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1203735109

Greenberg, J. T., Monach, P., Chou, J. H., Josephy, P. D., and Demple, B. (1990). Positive control of a global antioxidant defense regulon activated by superoxide-generating agents in Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 87, 6181–6185. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.16.6181

Gu, M., and Imlay, J. A. (2011). The SoxRS response of Escherichia coli is directly activated by redox-cycling drugs rather than by superoxide. Mol. Microbiol. 79, 1136–1150. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2010.07520.x

Hare, N. J., Scott, N. E., Shin, E. H. H., Connolly, A. M., Larsen, M. R., Palmisano, G., et al. (2011). Proteomics of the oxidative stress response induced by hydrogen peroxide and paraquat reveals a novel AhpC-like protein in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Proteomics 11, 3056–3069. doi: 10.1002/pmic.201000807

Harms, A., Maisonneuve, E., and Gerdes, K. (2016). Mechanisms of bacterial persistence during stress and antibiotic exposure. Science 354:aaf4268. doi: 10.1126/science.aaf4268

Hassett, D. J., Schweizer, H. P., and Ohman, D. E. (1995). Pseudomonas aeruginosa sodA and sodB mutants defective in manganese- and iron-cofactored superoxide dismutase activity demonstrate the importance of the iron-cofactored form in aerobic metabolism. J. Bacteriol. 177, 6330–6337. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.22.6330-6337.1995

Hassett, D. J., Sokol, P. A., Howell, M. L., Ma, J. U. F., Schweizer, H. T., Ochsner, U., et al. (1996). Ferric uptake regulator (Fur) mutants of Pseudomonas aeruginosa demonstrate defective siderophore-mediated iron uptake, altered aerobic growth, and decreased superoxide dismutase and catalase activities. J. Bacteriol. 178, 3996–4003. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.14.3996-4003.1996

Hausladen, A., and Fridovich, I. (1994). Superoxide and peroxynitrite inactivate aconitases, but nitric oxide does not. J. Biol. Chem. 269, 29405–29408.

Heindorf, M., Kadari, M., Heider, C., Skiebe, E., and Wilharm, G. (2014). Impact of Acinetobacter baumannii superoxide dismutase on motility, virulence, oxidative stress resistance and susceptibility to antibiotics. PLoS One 9:e101033. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0101033

Held, K., Ramage, E., Jacobs, M., Gallagher, L., Manoil, C., and Pao, P. (2012). Sequence-verified two-allele transposon mutant library for Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1. J. Bacteriol. 194, 6387–6389. doi: 10.1128/jb.01479-12

Hwang, S., Ryu, S., and Jeon, B. (2013). Roles of the superoxide dismutase SodB and the catalase KatA in the antibiotic resistance of Campylobacter jejuni. J. Antibiot. 66, 351–353. doi: 10.1038/ja.2013.20

Iiyama, K., Chieda, Y., Lee, J. M., Kusakabe, T., Yasunaga-Aoki, C., and Shimizu, S. (2007). Effect of superoxide dismutase gene inactivation on virulence of Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1 toward the silkworm, Bombyx mori. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 73, 1569–1575. doi: 10.1128/aem.00981-06

Imlay, J. A. (2013). The molecular mechanisms and physiological consequences of oxidative stress: lessons from a model bacterium. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 11, 443–454. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro3032

Keren, I., Wu, Y., Inocencio, J., Mulcahy, L. R., and Lewis, K. (2013). Killing by bactericidal antibiotics does not depend on reactive oxygen species. Science 339, 1213–1216. doi: 10.1126/science.1232688

Keyer, K., and Imlay, J. A. (1996). Superoxide accelerates DNA damage by elevating free-iron levels. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 93, 13635–13640. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.24.13635

Khakimova, M., Ahlgren, H. G., Harrison, J. J., English, A. M., and Nguyen, D. (2013). The stringent response controls catalases in Pseudomonas aeruginosa and is required for hydrogen peroxide and antibiotic tolerance. J. Bacteriol. 195, 2011–2020. doi: 10.1128/jb.02061-12

Kobayashi, K., and Tagawa, S. (2004). Activation of SoxR-dependent transcription in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Biochem. 136, 607–615. doi: 10.1093/jb/mvh168

Koutsolioutsou, A., Martins, E. A., White, D. G., Levy, S. B., and Demple, B. (2001). A soxRS-constitutive mutation contributing to antibiotic resistance in a clinical isolate of Salmonella enterica (Serovar typhimurium). Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45, 38–43. doi: 10.1128/aac.45.1.38-43.2001

Koutsolioutsou, A., Peña-Llopis, S., and Demple, B. (2005). Constitutive soxR mutations contribute to multiple-antibiotic resistance in clinical Escherichia coli isolates. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 49, 2746–2752. doi: 10.1128/aac.49.7.2746-2752.2005

Kuo, C. F., Mashino, T., and Fridovich, I. (1987). alpha, beta-Dihydroxyisovalerate dehydratase. A superoxide-sensitive enzyme. J. Biol. Chem. 262, 4724–4727.

Ladjouzi, R., Bizzini, A., Lebreton, F., Sauvageot, N., Rincé, A., Benachour, A., et al. (2013). Analysis of the tolerance of pathogenic enterococci and Staphylococcus aureus to cell wall active antibiotics. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 68, 2083–2091. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkt157

Ladjouzi, R., Bizzini, A., van Schaik, W., Zhang, X., Rincé, A., Benachour, A., et al. (2015). Loss of antibiotic tolerance in Sod-deficient mutants is dependent on the energy source and arginine catabolism in Enterococci. J. Bacteriol. 197, 3283–3293. doi: 10.1128/jb.00389-15

Lee, J. H., Lee, K. L., Yeo, W. S., Park, S. J., and Roe, J. H. (2009). SoxRS-mediated lipopolysaccharide modification enhances resistance against multiple drugs in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 191, 4441–4450. doi: 10.1128/jb.01474-08

Lee, K., Jung, J., Kim, K., Bae, D., and Lim, D. (2009). Overexpression of outer membrane protein OprT and increase of membrane permeability in phoU mutant of toluene-tolerant bacterium Pseudomonas putida GM730. J. Microbiol. 47, 557–562. doi: 10.1007/s12275-009-0105-y

Levin, B. R., and Rozen, D. E. (2006). Non-inherited antibiotic resistance. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 4, 556–562. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1445

Liu, Y., and Imlay, J. A. (2013). Cell death from antibiotics without the involvement of reactive oxygen species. Science 339, 1210–1213. doi: 10.1126/science.1232751

Lobritz, M. A., Belenky, P., Porter, C. B. M., Gutierrez, A., Yang, J. H., Schwarz, E. G., et al. (2015). Antibiotic efficacy is linked to bacterial cellular respiration. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 112, 8173–8180. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1509743112

Martins, D., and English, A. M. (2014). Catalase activity is stimulated by H2O2 in rich culture medium and is required for H2O2 resistance and adaptation in yeast. Redox Biol. 2, 308–313. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2013.12.019

Martins, D., McKay, G., Sampathkumar, G., Khakimova, M., English, A. M., and Nguyen, D. (2018). Superoxide dismutase activity confers (p)ppGpp-mediated antibiotic tolerance to stationary-phase Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 115, 9797–9802. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1804525115

Meylan, S., Andrews, I. W., and Collins, J. J. (2018). Targeting antibiotic tolerance, pathogen by pathogen. Cell 172, 1228–1238. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.01.037

Meylan, S., Porter, C. B. M., Yang, J. H., Belenky, P., Gutierrez, A., Lobritz, M. A., et al. (2017). Carbon sources tune antibiotic susceptibility in Pseudomonas aeruginosa via tricarboxylic acid cycle control. Cell Chem. Biol. 24, 195–206. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2016.12.015

Miller, P. F., Gambino, L. F., Sulavik, M. C., and Gracheck, S. J. (1994). Genetic relationship between soxRS and mar loci in promoting multiple antibiotic resistance in Escherichia coli. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 38, 1773–1779. doi: 10.1128/aac.38.8.1773

Mosel, M., Li, L., Drlica, K., and Zhao, X. (2013). Superoxide-mediated protection of Escherichia coli from antimicrobials. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 57, 5755–5759. doi: 10.1128/aac.00754-13

Murakami, K., Ono, T., Viducic, D., Kayama, S., Mori, M., Hirota, K., et al. (2005). Role for rpoS gene of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in antibiotic tolerance. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 242, 161–167.

Nguyen, D., Joshi-Datar, A., Lepine, F., Bauerle, E., Olakanmi, O., Beer, K., et al. (2011). Active starvation responses mediate antibiotic tolerance in biofilms and nutrient-limited bacteria. Science 334, 982–986. doi: 10.1126/science.1211037

Ocaktan, A., Yoneyama, H., and Nakae, T. (1997). Use of fluorescence probes to monitor function of the subunit proteins of the MexA-MexB-oprM drug extrusion machinery in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Biol. Chem. 272, 21964–21969. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.35.21964

Ochsner, U. A., Vasil, M. L., Alsabbagh, E., Parvatiyar, K., and Hassett, D. J. (2000). Role of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa oxyR-recG operon in oxidative stress defense and DNA repair: OxyR-dependent regulation of katB-ankB, ahpB, and ahpC-ahpF. J. Bacteriol. 182, 4533–4544. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.16.4533-4544.2000

Orman, M. A., and Brynildsen, M. P. (2015). Inhibition of stationary phase respiration impairs persister formation in E. coli. Nat. Commun. 6:7983.

Orman, M. A., and Brynildsen, M. P. (2016). Persister formation in Escherichia coli can be inhibited by treatment with nitric oxide. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 93, 145–154. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2016.02.003

Palma, M., Zurita, J., Ferreras, J. A., Worgall, S., Larone, D. H., Shi, L., et al. (2005). Pseudomonas aeruginosa SoxR does not conform to the archetypal paradigm for SoxR-dependent regulation of the bacterial oxidative stress adaptive response. Infect. Immun. 73, 2958–2966. doi: 10.1128/iai.73.5.2958-2966.2005

Pérez, A., Poza, M., Aranda, J., Latasa, C., Medrano, F. J., Tomás, M., et al. (2012). Effect of transcriptional activators SoxS, RobA, and RamA on expression of multidrug efflux pump AcrAB-TolC in Enterobacter cloacae. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 56, 6256–6266. doi: 10.1128/aac.01085-12

Pomposiello, P. J., Bennik, M. H. J., and Demple, B. (2001). Genome-wide transcriptional profiling of the Escherichia coli responses to superoxide stress and sodium salicylate. J. Bacteriol. 183, 3890–3902. doi: 10.1128/jb.183.13.3890-3902.2001

Rowe, S. E., Wagner, N. J., Li, L., Beam, J. E., Wilkinson, A. D., Radlinski, L. C., et al. (2020). Reactive oxygen species induce antibiotic tolerance during systemic Staphylococcus aureus infection. Nat. Microbiol. 5, 282–290. doi: 10.1038/s41564-019-0627-y

Salunkhe, P., von Götz, F., Wiehlmann, L., Lauber, J., Buer, J., and Tümmler, B. (2002). GeneChip expression analysis of the response of Pseudomonas aeruginosa to paraquat-induced auperoxide stress. Genome Lett. 1, 165–174. doi: 10.1166/gl.2002.019

Sampson, T. R., Liu, X., Schroeder, M. R., Kraft, C. S., Burd, E. M., and Weiss, D. S. (2012). Rapid killing of Acinetobacter baumannii by polymyxins is mediated by a hydroxyl radical death pathway. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 56, 5642–5649. doi: 10.1128/aac.00756-12

Singh, A. K., Shin, J. H., Lee, K. L., Imlay, J. A., and Roe, J. H. (2013). Comparative study of SoxR activation by redox-active compounds. Mol. Microbiol. 90, 983–996. doi: 10.1111/mmi.12410

Stewart, P. S., Franklin, M. J., Williamson, K. S., Folsom, J. P., Boegli, L., and James, G. A. (2015). Contribution of stress responses to antibiotic tolerance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 59, 3838–3847. doi: 10.1128/aac.00433-15

Van Acker, H., Gielis, J., Acke, M., Cools, F., Cos, P., and Coenye, T. (2016). The role of reactive oxygen species in antibiotic-induced cell death in Burkholderia cepacia complex bacteria. PLoS One 11:e0159837. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0159837

Walters, M. C., Roe, F., Bugnicourt, A., Franklin, M. J., and Stewart, P. S. (2003). Contributions of antibiotic penetration, oxygen limitation, and low metabolic activity to tolerance of Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms to ciprofloxacin and tobramycin. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 47, 317–323. doi: 10.1128/aac.47.1.317-323.2003

Wang, J. H., Singh, R., Benoit, M., Keyhan, M., Sylvester, M., Hsieh, M., et al. (2014). Sigma S-dependent antioxidant defense protects stationary-phase Escherichia coli against the bactericidal antibiotic gentamicin. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 58, 5964–5975. doi: 10.1128/aac.03683-14

Wang, J. Y., Burger, R. M., and Drlica, K. (1998). Role of superoxide in catalase-peroxidase-mediated isoniazid action against mycobacteria. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 42, 709–711. doi: 10.1128/aac.42.3.709

Wang, X., and Zhao, X. (2009). Contribution of oxidative damage to antimicrobial lethality. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 53, 1395–1402. doi: 10.1128/aac.01087-08

Wong, G. T., Bonocora, R. P., Schep, A. N., Beeler, S. M., Fong, A. J. L., Shull, L. M., et al. (2017). Genome-wide transcriptional response to varying RpoS levels in Escherichia coli K-12. J. Bacteriol. 199:e00755-16.

Wu, Y., Vuliæ, M., Keren, I., and Lewis, K. (2012). Role of oxidative stress in persister tolerance. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 56, 4922–4926. doi: 10.1128/aac.00921-12

Keywords: Pseudomonas aeruginosa, antibiotic tolerance, stationary phase, superoxide dismutase, superoxide generators, paraquat, stringent response, RpoS

Citation: Martins D, McKay GA, English AM and Nguyen D (2020) Sublethal Paraquat Confers Multidrug Tolerance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa by Inducing Superoxide Dismutase Activity and Lowering Envelope Permeability. Front. Microbiol. 11:576708. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2020.576708

Received: 26 June 2020; Accepted: 31 August 2020;

Published: 25 September 2020.

Edited by:

Weihui Wu, Nankai University, ChinaReviewed by:

Nisanart Charoenlap, Chulabhorn Research Institute, ThailandMarc G. J. Feuilloley, Université de Rouen, France

Copyright © 2020 Martins, McKay, English and Nguyen. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Dao Nguyen, ZGFvLm5ndXllbkBtY2dpbGwuY2E=

Dorival Martins

Dorival Martins Geoffrey A. McKay

Geoffrey A. McKay Ann M. English

Ann M. English Dao Nguyen

Dao Nguyen