94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Microbiol. , 29 September 2020

Sec. Microbiotechnology

Volume 11 - 2020 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2020.566117

This article is part of the Research Topic Exploring the Growing Role of Cyanobacteria in Industrial Biotechnology and Sustainability View all 10 articles

myo-inositol (MI) is an essential growth factor, nutritional source, and important precursor for many derivatives like D-chiro-inositol. In this study, attempts were made to achieve the “green biosynthesis” of MI in a model photosynthetic cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. First, several genes encoding myo-inositol-1-phosphate synthases and myo-inositol-1-monophosphatase, catalyzing the first or the second step of MI synthesis, were introduced, respectively, into Synechocystis. The results showed that the engineered strain carrying myo-inositol-1-phosphate synthase gene from Saccharomyces cerevisiae was able to produce MI at 0.97 mg L–1. Second, the combined overexpression of genes related to the two catalyzing processes increased the production up to 1.42 mg L–1. Third, to re-direct more cellular carbon flux into MI synthesis, an inducible small RNA regulatory tool, based on MicC-Hfq, was utilized to control the competing pathways of MI biosynthesis, resulting in MI production of ∼7.93 mg L–1. Finally, by optimizing the cultivation condition via supplying bicarbonate to enhance carbon fixation, a final MI production up to 12.72 mg L–1 was achieved, representing a ∼12-fold increase compared with the initial MI-producing strain. This study provides a light-driven green synthetic strategy for MI directly from CO2 in cyanobacterial chassis and represents a renewable alternative that may deserve further optimization in the future.

Inositol, known as cyclohexanehexol, is a vital growth factor previously identified in bacteria, fungi, higher plants, and animals. It has nine isomers (i.e., myo-, cis-, epi-, allo-, muco-, neo-, L-chiro-, D-chiro-, and scyllo-), and five of them have been found in nature, namely, D-chiro-inositol, L-chiro-inositol, myo-inositol, neo-inositol, and scyllo-inositol (Thomas et al., 2016). Among them, myo-inositol (cis-1, 2, 3, 5-trans-4, 6-cyclohexanehexol, hereafter MI) and its derivatives are the most abundant in nature and have attracted significant attention in recent years due to their wide applications in functional food and pharmaceutical industry (You et al., 2017). For example, MI was reported to be effective in restoring spontaneous ovarian activity, consequently improving the fertility of most patients with polycystic ovary syndrome (Regidor et al., 2018; Januszewski et al., 2019). In addition, MI serves as a precursor for many valuable chemicals, further generating numerous important chemicals participating in maintaining homeostasis, such as inositol-1, 4, 5-trisphosphate (IP3) that functions as a Ca2+-mobilizing second messenger in regulating many cellular processes (Berridge, 2009). Moreover, MI can also be converted to scyllo- and D-chiro–inositol, both of which have potential roles in the medicine industry in curing Alzheimer’s disease and hyperglycemia (Ma et al., 2012; Cheng et al., 2019). It is thus valuable to develop cost-efficient strategies for MI production.

Several strategies have been so far reported for MI synthesis. Among all chemical approaches, it is difficult to operate and is less environmentally friendly due to its harsh chemical conditions, such as low pH, high temperature, and high pressure. Recently, the microbial production of MI through synthetic biology has attracted increasing attention (Fujisawa et al., 2017; You et al., 2017; Lu et al., 2018). For example, Lu et al. (2018) recently reported a novel pathway to produce MI from glucose through a trienzymatic cascade system in vitro, achieving a productivity of 45.2 mM within 24 h. By dynamically modulating the key enzyme phosphofructokinase-I (Pfk-I) in Escherichia coli, recently a level of MI production at 1.31 g L–1 was achieved (Brockman and Prather, 2015). In addition, Tanaka et al. (2013) constructed a pathway starting from MI to scyllo-inositol in Bacillus subtilis, resulting in scyllo-inositol productivity of 10 g L–1 after 48 h. More recently, by introducing Mycobacterium tuberculosis ino1 gene encoding myo-inositol-1-phosphate synthase and overexpressing intrinsic inositol monophosphatase, YktC, as well as an artificial pathway converting myo-inositol to scyllo-inositol in Bacillus subtilis, Michon et al. (2020) achieved a production of 2 g L–1 scyllo-inositol using 20 g L–1 glucose. Nevertheless, even with all the exciting progresses, a new, renewable, and cost-efficient alternative for MI production remains to be developed.

Due to the ability of utilizing sunlight and CO2 as sole energy and carbon sources, respectively, cyanobacteria are considered as promising green chassis for producing chemicals. Up to now, several dozens of biofuels and chemicals have been successfully synthesized directly from CO2 in cyanobacteria, such as ethylene, ethanol, fatty acids, D-lactic acid, 3-hydroxypropionic acid, etc. (Gao et al., 2016). As a model cyanobacterium, Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803 (hereafter Synechocystis) has the advantages of a simple genetic background and feasible genetic tools for metabolic engineering and synthetic biology (Sun et al., 2018a). Given that cyanobacteria could directly use CO2 to produce chemicals driven by sunlight, attempts were made in this study to construct green synthesis strategy for MI in Synechocystis chassis.

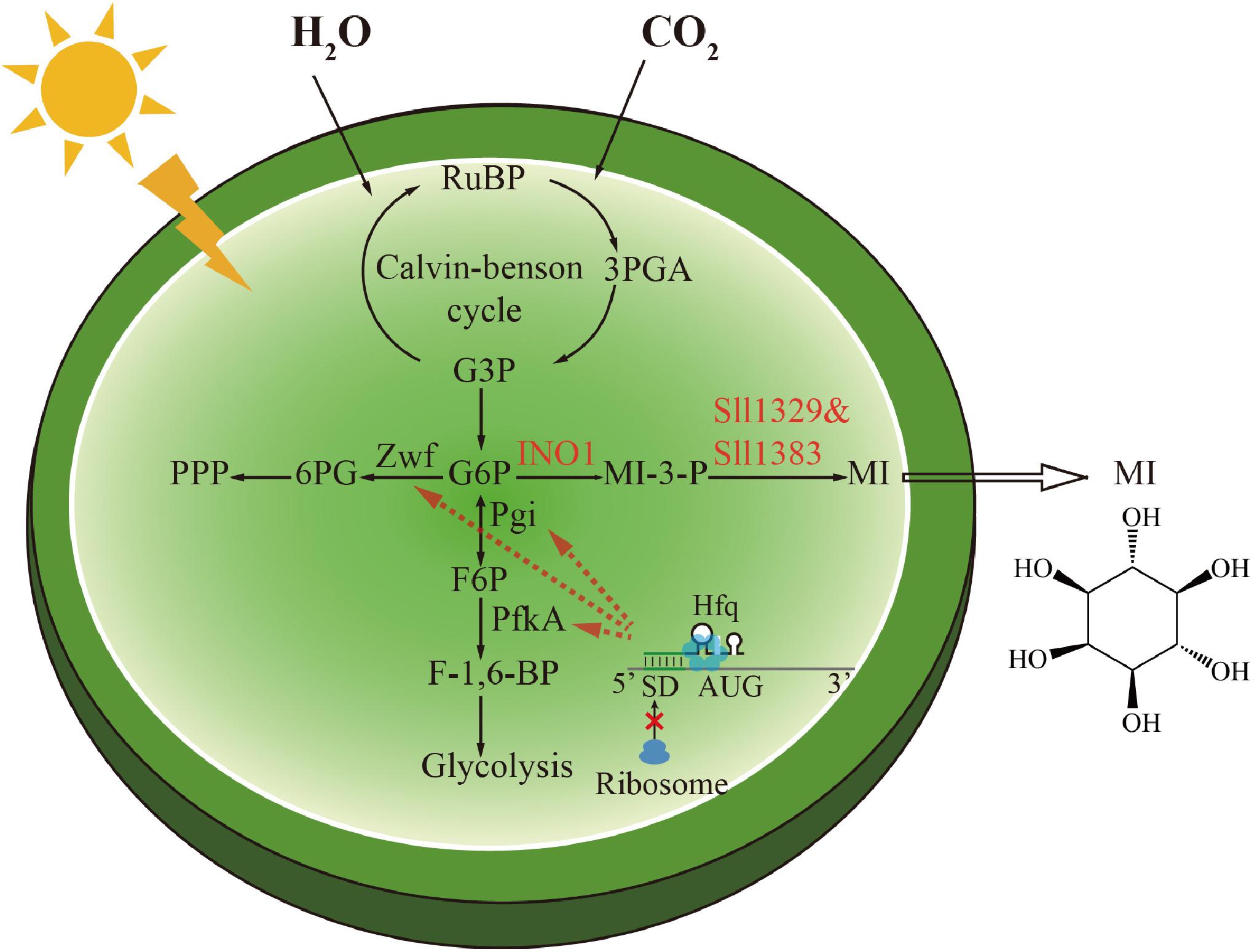

In this study (Figure 1), to achieve the green synthesis of MI, we first constructed an exogenous metabolic route to convert glucose-6-phosphate to MI in Synechocystis by, respectively, introducing myo-inositol-1-phosphate synthase from Saccharomyces cerevisiae or Corynebacterium glutamicum as well as the native genes (sll1329 and sll1383) encoding myo-inositol-1-monophosphatase. The results showed that the engineered Synechocystis carrying INO1 (myo-inositol-1-phosphate synthases from S. cerevisiae) performed the best, with MI production of 0.97 mg L–1. Second, the combined overexpression of INO1, sll1329, and sll1383 further improved MI production. Third, to drive more carbon flux into MI synthesis, endogenous gene zwf (encoding glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase), pgi (encoding glucose-6-phosphate isomerase), and pfkA (encoding phosphofructokinase) were knocked down, respectively, and combined, using a theophylline-inducible small RNA (sRNA) regulatory tool based on MicC-Hfq, leading to MI production of up to 7.93 mg L–1. Finally, by supplying bicarbonate to enhance carbon fixation, a final MI production up to 12.72 mg L–1 was achieved, representing a ∼12-fold increase compared with the initial MI-producing strain.

Figure 1. Scheme of the biosynthetic pathway of myo-inositol and the metabolic regulation strategy in Synechocystis. The genetic modifications made in this study were highlighted. The conversion of glucose-6-phosphate (G-6-P) to myo-inositol (MI) was catalyzed by inositol-1-phosphate synthase (INO1) and myo-inositol-1-monophosphatase (Sll1329 and Sll1383). The phosphoglucose isomerase (Pgi), phosphofructokinase (PfkA), and glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (Zwf) were downregulated by a small RNA tool to direct G-6-P to MI biosynthesis.

MI standard was purchased from Rhawn Chemical Technology Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). The other chemicals used in this study were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (MO, United States). T4 Polynucleotide Kinase, T4 DNA ligase, and all restriction enzymes were purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific (MA, United States). Phanta Super-Fidelity DNA Polymerase, ChamQ SYBR qPCR Master Mix, and HiScript Q RT SuperMix for qPCR were obtained from Vazyme Biotech Co., Ltd. (Nanjing, China). The Plasmid Mini Kit I and Cycle Pure Kit used were purchased from Omega Bio-Tek (GA, United States). Synthesis of DNA oligonucleotide primers and Sanger sequencing were provided by Genewiz (Suzhou, China).

The wild-type (WT) and all engineered strains of Synechocystis were grown at 30°C in BG-11 liquid medium or on solid BG-11 agar plate at a light intensity of ∼50 μmol photons m–2 s–1 in an incubator (SPX-250B-G, Boxun, Shanghai, China) or illuminating shaking incubator (HNY-211B, Honour, Tianjin, China) at 130 rpm, respectively. Appropriate antibiotic(s) was added into the BG-11 growth medium as required (i.e., 20 μg ml–1 chloramphenicol or 20 μg ml–1 spectinomycin). The growth of the cells was monitored by measuring their optical density at 730 nm (OD730) with a UV-1750 spectrophotometer (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan). E. coli Trans 5α was used as a host for constructing all recombinant plasmids, which were grown on Luria–Bertani solid agar plates or in a medium with appropriate antibiotic(s) to maintain the plasmids (i.e., 50 μg ml–1 chloramphenicol or 50 μg ml–1 spectinomycin) at 37°C in an incubator or a shaking incubator (HNY-100B, Honour, Tianjin, China) at 200 rpm, respectively.

E. coli Trans 5α was used as a host for plasmid construction and amplification. In this study, two suicide plasmids, p3031 and p0168, that could replicate in E. coli and integrate into the genome of Synechocystis (between slr2030 and slr2031 for p3031 or within slr0168 for p0168, respectively) via homologous recombination were utilized to express the related genes. The INO1 and cgl2996 genes were amplified using S. cerevisiae and C. glutamicum genomic DNA as templates, respectively. Then INO1 and cgl2996 were, respectively, ligated into pCP3031 (Supplementary Figure S1), resulting in plasmids p3031I and p3031C, respectively. After being confirmed by DNA sequencing, these two genes were, respectively, introduced into WT, generating the strains WT-INO1 and WT-cgl. The sll1329 and sll1383 genes were amplified using Synechocystis genomic DNA as template and fused into one fragment linked by a ribosome binding site (RBS) via overlapping PCR. The fused fragment was then ligated into pCP3031, resulting in plasmid p3031SS. The p3031SS was introduced into WT, generating the strain WT-SS. In addition, the fragments of sll1329 and sll1383 were further fused with a strong promoter, Pcpc560, and inserted after the cassette of INO1 on p3031I for transformation, generating the plasmid p3031S and the Synechocystis strain WT-INO1SS, respectively. The construction of sRNA-expressing plasmids was conducted as reported previously (Sun et al., 2018b). First, a light-induced promoter PpsbA2M (Ppsba2 without RBS) was utilized to express the sRNA scaffold micC, while a theophylline-induced riboswitch was used to control the expression of hfq, respectively (Supplementary Figure S2). Second, the synthetic 24-bp sRNA sequence (aszwf) targeting the translational starting site of the zwf was added into the location between PpsbA2M and MicC, leading to p0168Z, with a PpsbA2M-aszwf-micC-TrbcL-Ptrc-riboswitch-hfq-TrbcL cassette. Similarly, the plasmids with sRNA-expressing cassette targeting the pgi and the pfkA (aspgi and aspfkA) were constructed independently, leading to p0168P and p0168PF, respectively. The p0168Z, p0168P, and p0168PF plasmids were, respectively, transferred into Synechocystis WT-INO1SS through natural transformation, generating the strains WT-INO1SS-ASZWF, WT-INO1SS-ASPGI, and WT-INO1SS-ASPFKA, respectively. Finally, two expressing cassettes, PpsbA2M-aspgi-micC-TrbcL and PpsbA2M-aspfkA-micC-TrbcL, were ligated into p0168Z, generating p0168ZP or p0168ZF, respectively targeting two genes (i.e., targeting zwf and pgi or zwf and pfkA). They were then introduced into WT-INO1SS to generate the strains WT-INO1SSZP and WT-INO1SSZF, respectively. All the strains and the plasmids used and constructed in this study are listed in Table 1.

Natural transformation of Synechocystis was performed according to the method published previously. Briefly, when Synechocystis grew to exponential phase (OD730≈ 0.5), cells were collected by centrifugation (3,000 × g, 13 min, 4°C) and washed with fresh BG-11 medium. The cells were then resuspended in fresh BG-11, and ∼10 μg of corresponding plasmid DNA was added to the suspension. The cell and plasmid mixture was incubated at 30°C for at least 5 h under luminous intensity of ∼50 μmol photons m–2 s–1, followed by spreading onto BG-11 agar plates with appropriate antibiotic(s) (e.g., 20 μg ml–1 chloramphenicol and/or 20 μg ml–1 spectinomycin). After incubation of ∼2 weeks, colonies were observed. After validation by colony PCR and sequencing, positive colonies would be transferred to liquid BG11 medium for growth and further examination.

For Synechocystis samples, 1 ml of fresh cultures of Synechocystis was collected on the third day by centrifugation at 12,000 × g for 5 min at room temperature (Eppendorf 5430R, Hamburg, Germany). The MI content in the sample pellets and the supernatant were, respectively, measured after performing pre-column derivatization according to the two-stage technique described previously (Roessner et al., 2001). Meanwhile, the stock solution of MI was prepared in ddH2O at a final concentration of 1 g L–1. The MI standard curve was plotted using different concentrations of MI solution (Supplementary Figure S4). MI levels were quantified on a gas chromatography–mass spectrometry system—GC 7890 coupled to MSD 5975 (Agilent Technologies, Inc., Santa Clara, CA) equipped with a HP-5MS capillary column (30 m × 250 mm id).

The stock solution of theophylline was prepared by dissolving theophylline (Aladdin; Shanghai; China) in BG-11 medium at a final concentration of 10 mM. For theophylline-induced assays, all Synechocystis samples were collected by centrifugation at 3,000 × g and 4°C for 12 min and then re-suspended using fresh BG-11 medium with stock solution of theophylline at a final concentration of 2 mM (Sun et al., 2018b).

Synechocystis samples were collected at 24 h after 2 mM theophylline induction. ∼5 ml of samples (OD730 = 1.0) was collected by centrifugation at 3,000 × g and 4°C for 12 min. The supernatant was removed, and the cell pellet was used for RNA extraction. Total RNA extraction was achieved through a Direct-zolTM RNA MiniPrep Kit (Zymo, CA, United States), and cDNAs were synthesized using HiScript Q RT SuperMix for qPCR (Vazyme Biotech Co., Ltd., Nanjing, China). The 10-μl qRT-PCR reaction included 5 μl ChamQ SYBR qPCR Master Mix (Vazyme Biotech Co., Ltd., Nanjing, China), 3 μl ddH2O, 1 μl diluted template cDNA, and 1 μl of each PCR primer (0.5 μl forward primer and 0.5 μl reverse primer). The reaction was conducted in the StepOneTM Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems, CA, United States). 16S rRNA was selected as the reference gene, and the primers of the specific genes used are listed in Supplementary Table S1. Data analysis was carried out by using 2−ΔΔCT method as reported previously (Livak and Schmittgen, 2001).

The bioconversion from glucose to MI involves three steps which are catalyzed by three sequentially acting enzymes (Fujisawa et al., 2017; You et al., 2017; Lu et al., 2018). First, with the aid of hexokinase, glucose was phosphorylated to glucose-6-phosphate (G6P). Second, G6P was converted into myo-inositol 3-phosphate (I3P), catalyzed by inositol-1-phosphate synthase (IPS), which was responsible for the committed step of inositol synthesis. Third, I3P was dephosphorylated to generate MI by inositol-1-monophosphatase. Previously, native genes potentially related to MI synthesis have been identified in Synechocystis (Chatterjee et al., 2004, 2006; Patra et al., 2007). In this study, to detect the production of MI in the Synechocystis WT strain, we measured both intracellular and extracellular MI, and the results showed that no detectable MI could be observed even after 7 days of cultivation, demonstrating that the MI produced natively was below the detection limit. Previously, studies showed that the INO1 gene encoding inositol-1-phosphate synthase from S. cerevisiae could perform well in E. coli (Gupta et al., 2017). In addition, an IPS gene of the same function, cgl2996, was also identified in C. glutamicum. Therefore, INO1 from S. cerevisiae and cgl2996 from C. glutamicum were, respectively, introduced and evaluated in Synechocystis, generating the strains WT-INO1 and WT-cgl (Table 1).

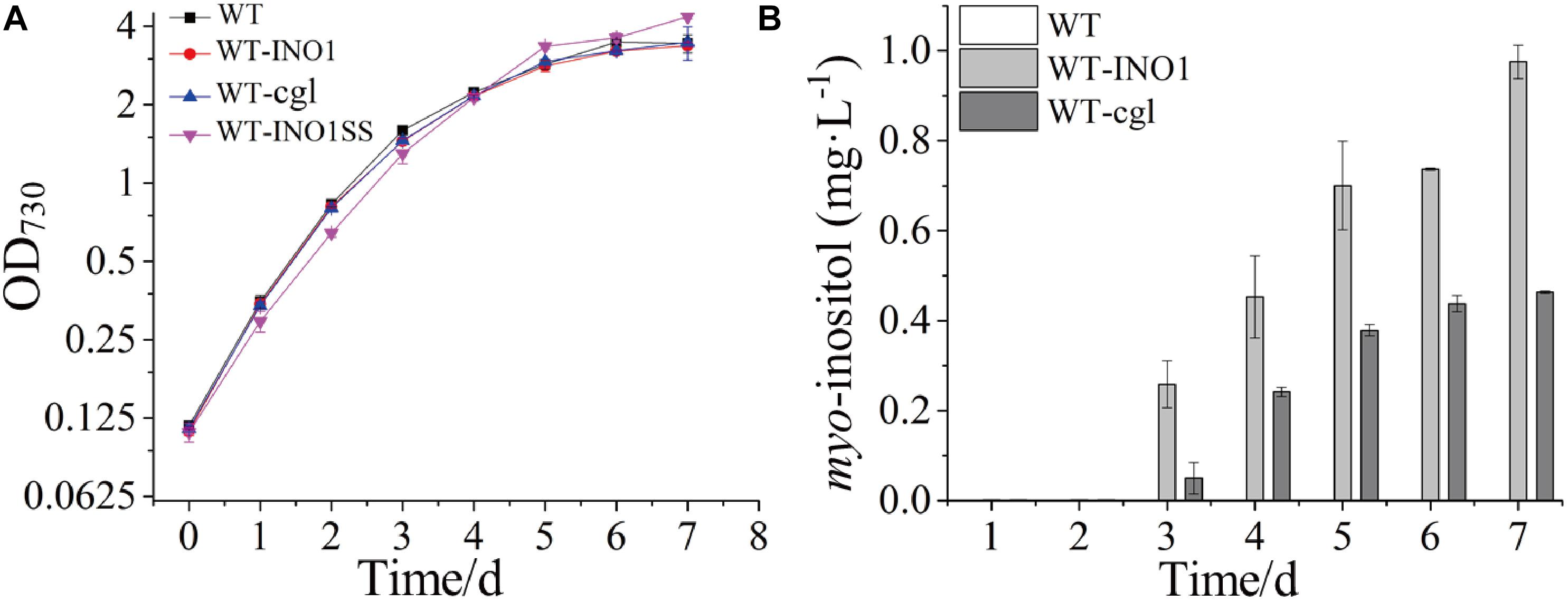

The growth comparison between WT, WT-INO1, and WT-cgl suggested that overexpression of neither INOI nor cgl2996 affected the growth of the engineered strains (Figure 2A). The potential production of MI was measured in both WT-INO1 and WT-cgl strains. As shown in Figure 2B, no MI was detected by GC-MS in the first 2 days as they were probably below the detection limit; however, MI could be observed in both intracellular and extracellular samples from the 3rd day (Supplementary Figure S3) and accumulated steadily until the 7th day (stationary phase) (Figure 2B). Finally, after cultivation for 7 days, the production of MI reached ∼975.5 μg L–1 in WT-INO1, while it only reached ∼463.8 μg L–1 in WT-cgl, respectively. These results demonstrated that the introduction of exogenous IPS could enable the MI biosynthesis in Synechocystis. In addition, the IPS from S. cerevisiae seemed to function better for MI biosynthesis than that from C. glutamicum in Synechocystis.

Figure 2. Growth curves and myo-inositol quantitation in wild-type (WT) and engineered Synechocystis strains. The error bar represents the standard deviation of three biological replicates for each sample. (A) Growth curves of WT, WT-INO1, WT-cgl, and WT-INO1SS. (B) myo-inositol quantitation in WT and WT-cgl.

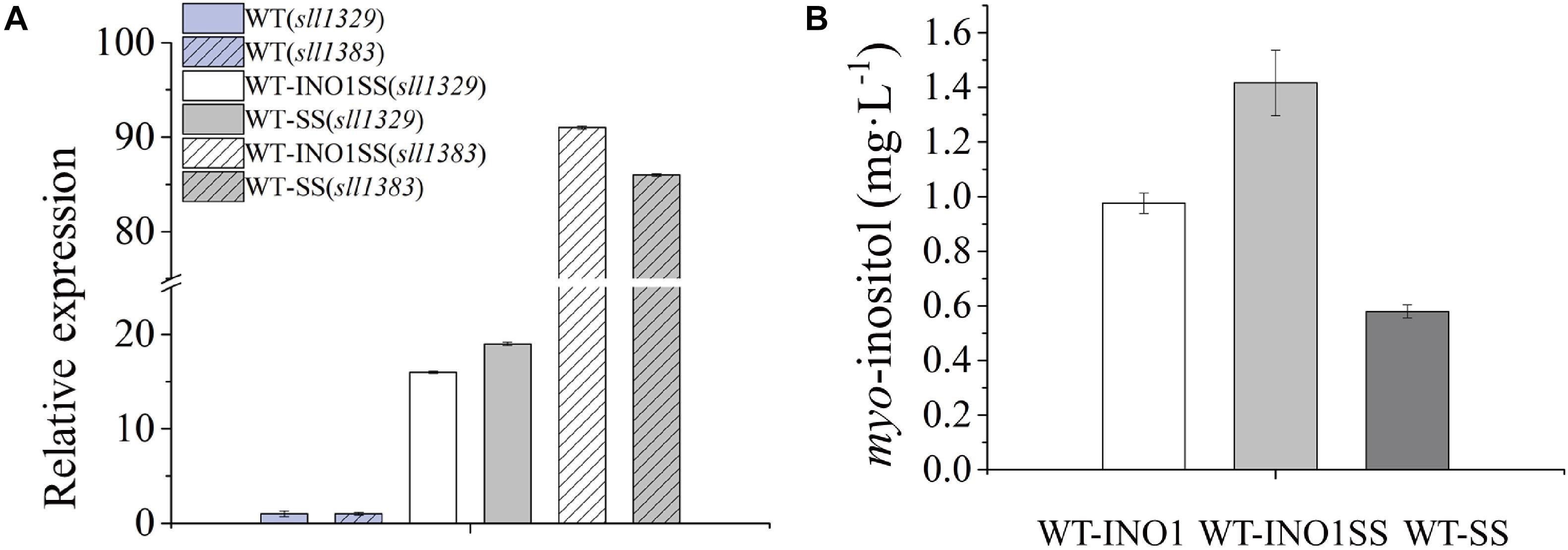

myo-inositol-1-monophosphatase (IMP) is another crucial enzyme for MI synthesis that catalyzes the production of myo-inositol from myo-inositol 3-phosphate. This enzyme is putatively encoded by sll1329 or sll1383 in Synechocystis according to a previous study (Patra et al., 2007) and the KEGG pathway annotation1. In order to further improve the MI production, we simultaneously overexpressed the genes sll1329 and sll1383 (isozyme genes, both encoding IMP) using a strong promoter Pcpc560 in WT-INO1, resulting in the strain WT-INO1SS (Table 1). As a control, strain WT-SS with only overexpressed sll1329 and sll1383 was also constructed (Table 1). To evaluate their expression, the transcriptional levels of sll1329 and sll1383 in WT-INO1SS or WT-SS were quantified via qRT-PCR. As illustrated in Figure 3A, the transcriptional levels of sll1329 and sll1383 were, respectively, increased by more than 15- and 80-folds in both WT-INO1SS and WT-SS compared to that of WT, suggesting a successful overexpression. The growth of WT and WT-INO1SS was comparatively investigated, and the results showed that the overexpression of sll1329 and sll1383 caused no visible growth inhibition (Figure 2A). Moreover, the production of MI reached 1.42 mg L–1 in WT-INO1SS after cultivation for 7 days, achieving ∼45.6% increase compared to that in WT-INO1 (Figure 3B). In the control WT-SS strain where only sll1329 and sll1383 were expressed, MI analysis showed that it can produce MI production at 579.6 μg L–1, confirming the existence of a native INO1 gene encoding inositol-1-phosphate synthase in Synechocystis (Chatterjee et al., 2004, 2006; Patra et al., 2007), although its catalytical activity might be well lower than INO1 from S. cerevisiae and Cgl2996 from C. glutamicum. The results supported the report that the overexpression of sll1329 and sll1383 could improve the production of MI.

Figure 3. qRT-PCR assays and myo-inositol quantitation in the engineered Synechocystis strain WT-INO1SS. The error bar represents the standard deviation of three technical replicates for each sample. (A) Relative transcriptional level of sll1383 and sll1329 in WT and WT-INO1SS, respectively. (B) myo-inositol quantitation in WT-INO1, WT-SS, and WT-INO1SS.

Glycolysis and pentose phosphate pathway are the main carbon source competing pathways for MI synthesis (Figure 1; Hansen et al., 1999). However, total blocking of these essential pathways would cause severe growth inhibition or even a lethal phenotype. In order to drive more carbon flux from the competing pathways to MI biosynthesis, a sRNA tool MicC–Hfq, developed previously in Synechocystis, that allows “gene knock-down” was adopted (Sun et al., 2018b). In detail, the Hfq–MicC tool is composed of a chaperone protein Hfq and a well-studied sRNA scaffold named MicC from E. coli. With a designed target-binding region fused into the MicC scaffold, the fragment could regulate the expression of target genes effectively via altering their translation with the aid of the Hfq chaperone.

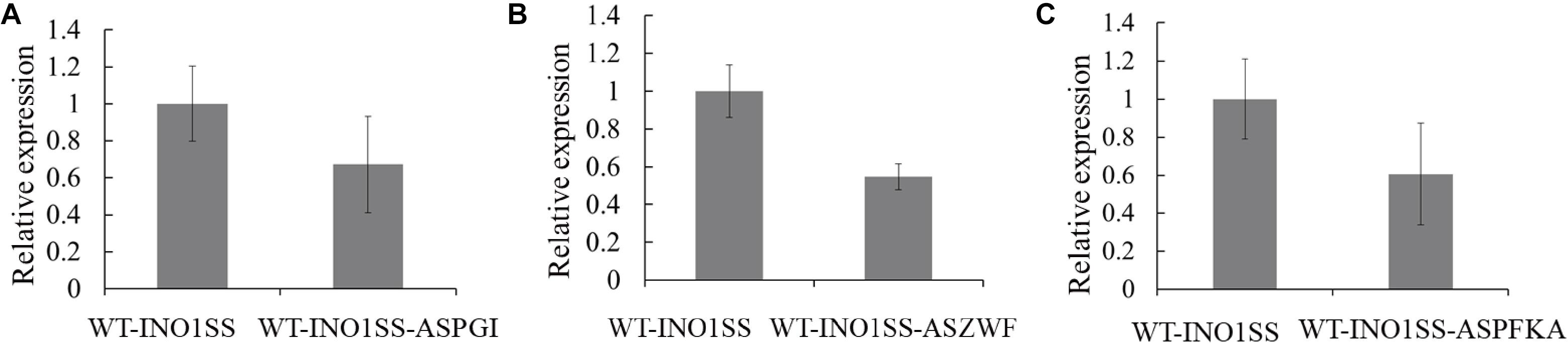

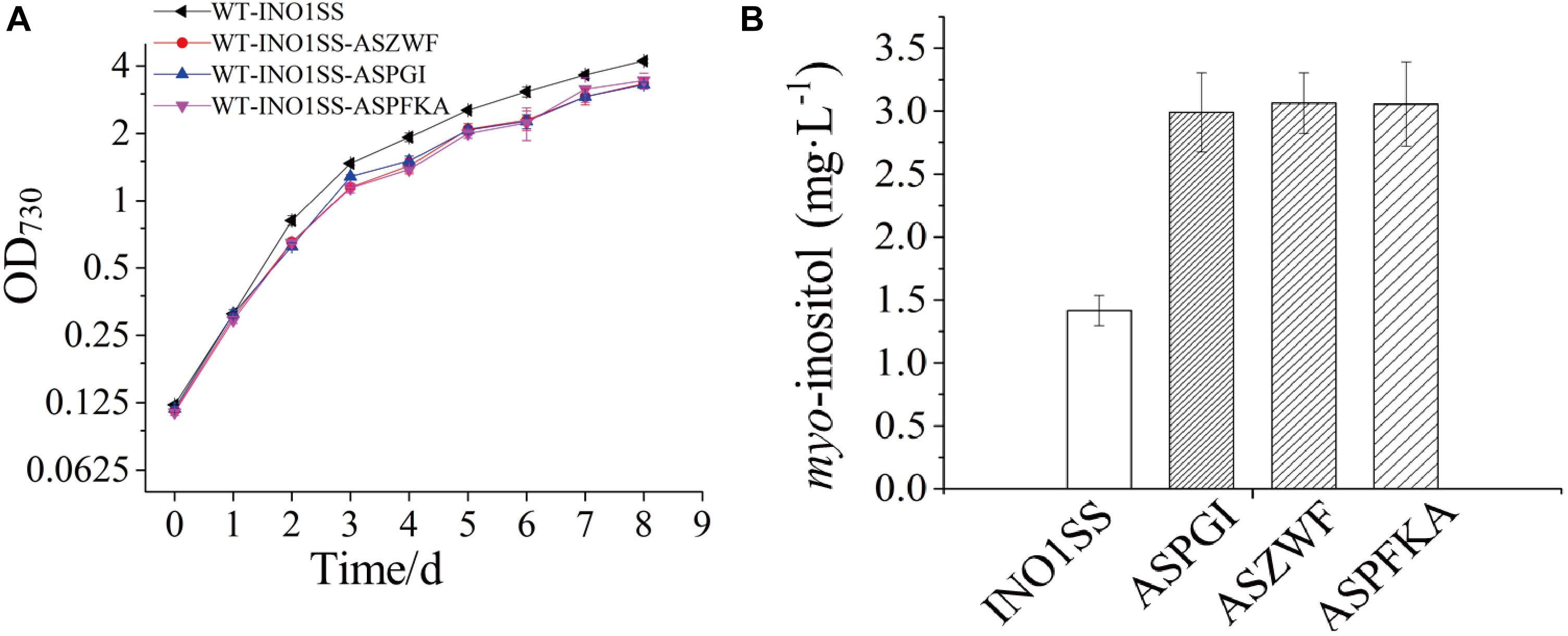

Glucose-6-phosphate (G6P) is not only a metabolic branch point but also a substrate for inositol synthesis in cells, as it could be routed into native cellular metabolism through both glycolysis and the oxidative pentose phosphate pathway, as well as into the heterologous biosynthetic pathway of MI production. Thus, pgi (encoding phosphoglucose isomerase), pfkA (encoding phosphofructokinase), and zwf (encoding glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase) were chosen as the target genes, and the related sRNA expressing systems were constructed. The synthetic sRNA sequences targeting the translational starting site of the zwf, pgi, or pfkA were fused, respectively, into the MicC scaffold and driven by PpsbA2M (PpsbA2 without RBS), while the expression of hfq was controlled by the Ptrc containing a theophylline-induced riboswitch. In addition, the related strains WT-INO1SS-ASPGI, WT-INO1SS-ASPFKA, and WT-INO1SS-ASZWF were, respectively, achieved via introducing the MicC–Hfq-expressing cassettes (Table 1). After induction with 2 mM theophylline, qRT-PCR analysis, growth curves, and myo-inositol production determination of the three strains were performed. First, qRT-PCR analysis was performed to validate the knockdown effect of the MicC–Hfq tool on all three target genes. As shown in Figures 4A–C, when compared to that in WT-INO1SS, 33, 45, and 39% down-regulation for pgi, pfkA, and zwf were achieved via the synthetic sRNA in WT-INO1SS-ASPGI, WT-INO1SS-ASPFKA, and WT-INO1SS-ASZWF, respectively. Second, the growth rate of the three strains was comparatively monitored, and only a slight inhibition was observed for WT-INO1SS-ASPGI, WT-INO1SS-ASPFKA, and WT-INO1SS-ASZWF compared to WT-INO1SS (Figure 5A). Third, the production of MI in three strains was determined, and the results showed that MI production was increased to 3.00, 3.06, and 3.06 mg L–1 in strains WT-INO1SS-ASPGI, WT-INO1SS-ASZWF, and WT-INO1SS-ASPFKA, respectively (Figure 5B), suggesting that the knock-down of pgi, zwf, and pfkA by the synthetic sRNAs was able to efficiently increase the metabolic flux from glucose-6-phosphate into MI.

Figure 4. qRT-PCR assays in the engineered Synechocystis strains WT-INO1SS-ASPGI, WT-INO1SS-ASZWF, and WT-INO1SS-ASPFKA after providing the supplement of 2 mM theophylline. The error bar represents the standard deviation of three technical replicates for each sample. (A) Relative transcriptional level of pgi in WT-INO1SS and WT-INO1SS-ASPGI. (B) Relative transcriptional level of zwf in WT-INO1SS and WT-INO1SS-ASZWF. (C) Relative transcriptional level of pfkA in WT-INO1SS and WT-INO1SS-ASPFKA.

Figure 5. Growth curves and myo-inositol quantitation in the engineered Synechocystis strains WT-INO1SS-ASPGI, WT-INO1SS-ASZWF, and WT-INO1SS-ASPFKA. The error bar represents the standard deviation of three biological replicates for each sample. INO1SS, strain WT-INO1SS; ASPGI, strain WT-INO1SS-ASPGI; ASZWF, strain WT-INO1SS-ASZWF; ASPFKA, strain WT-INO1SS-ASPFKA. (A) Growth curves of WT-INO1SS, WT-INO1SS-ASPGI, WT-INO1SS-ASZWF, and WT-INO1SS-ASPFKA. (B) myo-inositol quantitation in WT-INO1SS, WT-INO1SS-ASPGI, WT-INO1SS-ASZWF, and WT-INO1SS-ASPFKA after 8 days of cultivation.

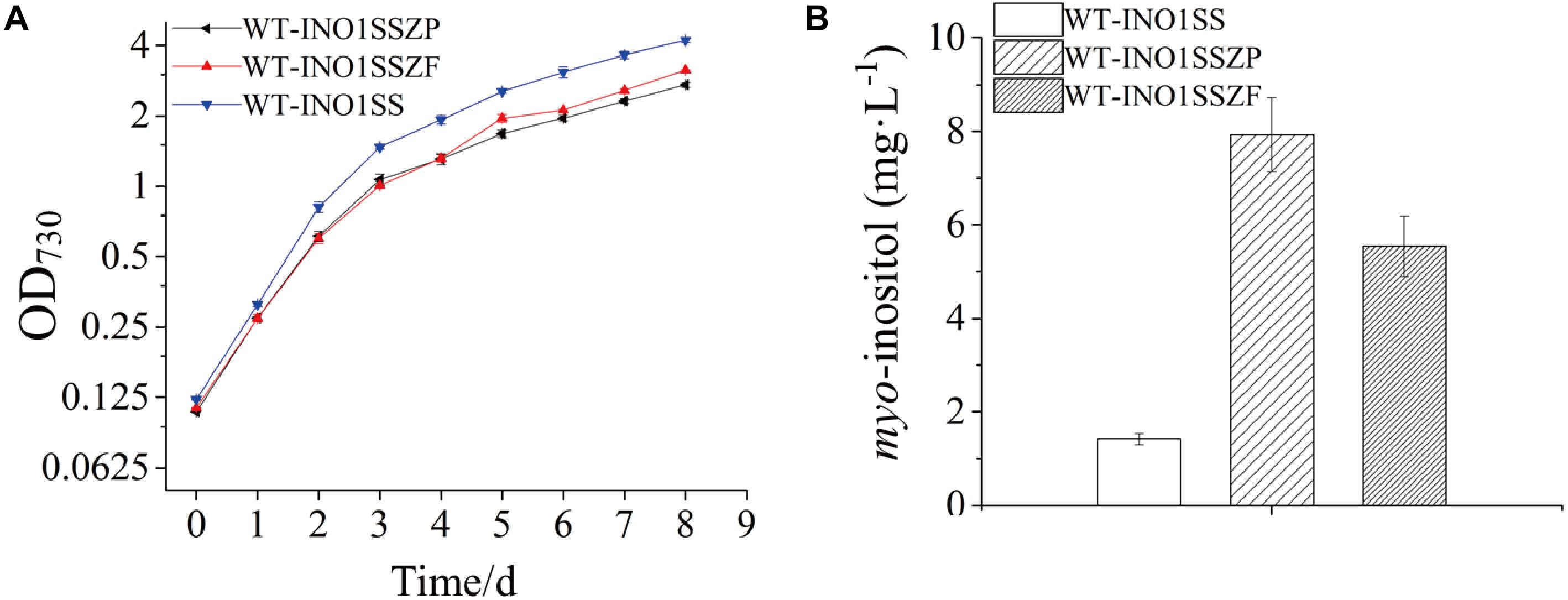

Given that pgi and pfkA genes are both involved in the same pathway, a combined regulation for zwf and pgi or zwf and pfkA was carried out to evaluate whether it can further increase MI production. Accordingly, two strains, WT-INO1SSZP and WT-INO1SSZF, carrying the synthetic sRNAs targeting both zwf and pgi or both zwf and pfkA, respectively, were constructed. As illustrated in Supplementary Figure S5, the expression level of zwf was decreased by 42 and 41% in WT-INO1SSZP and WT-INO1SSZF; pfkA in WT-INO1SSZF and pgi in WT-INO1SSZP were decreased as well by 39 and 37% compared to that in WT after induction with 2 mM theophylline. The growth curves and the MI yields of the two strains were then measured after addition of 2 mM theophylline (Figure 6A); however, an obvious retardation in growth was observed for both strains, possibly due to the increased partitioning of carbon sources toward myo-inositol, which is consistent with the increased MI production in WT-INO1SSZP and WT-INO1SSZF even with the decreased growth (Figure 6B). The results showed that the MI production reached 7.93 and 5.54 mg L–1 in WT-INO1SSZP and WT-INO1SSZF, respectively, indicating that the combined regulation of zwf and pgi was more effective for increasing MI synthesis. Between the two engineered strains, WT-INO1SSZP grew slower than WT-INO1SSZF (Figure 6A), which may be due to the fact that more glucose-6-phosphate was directed into the MI biosynthesis pathway from glycolysis and pentose phosphate pathway with the aid of sRNA tools in WT-INO1SSZP.

Figure 6. Growth curves and myo-inositol quantitation in the engineered Synechocystis strains WT-INO1SSZP and WT-INO1SSZF. The error bar represents the standard deviation of three biological replicates for each sample. (A) Growth curves of WT-INO1SS, WT-INO1SSZP, and WT-INO1SSZF. (B) myo-inositol quantitation in WT-INO1SS, WT-INO1SSZP, and WT-INO1SSZF after 8 days of cultivation.

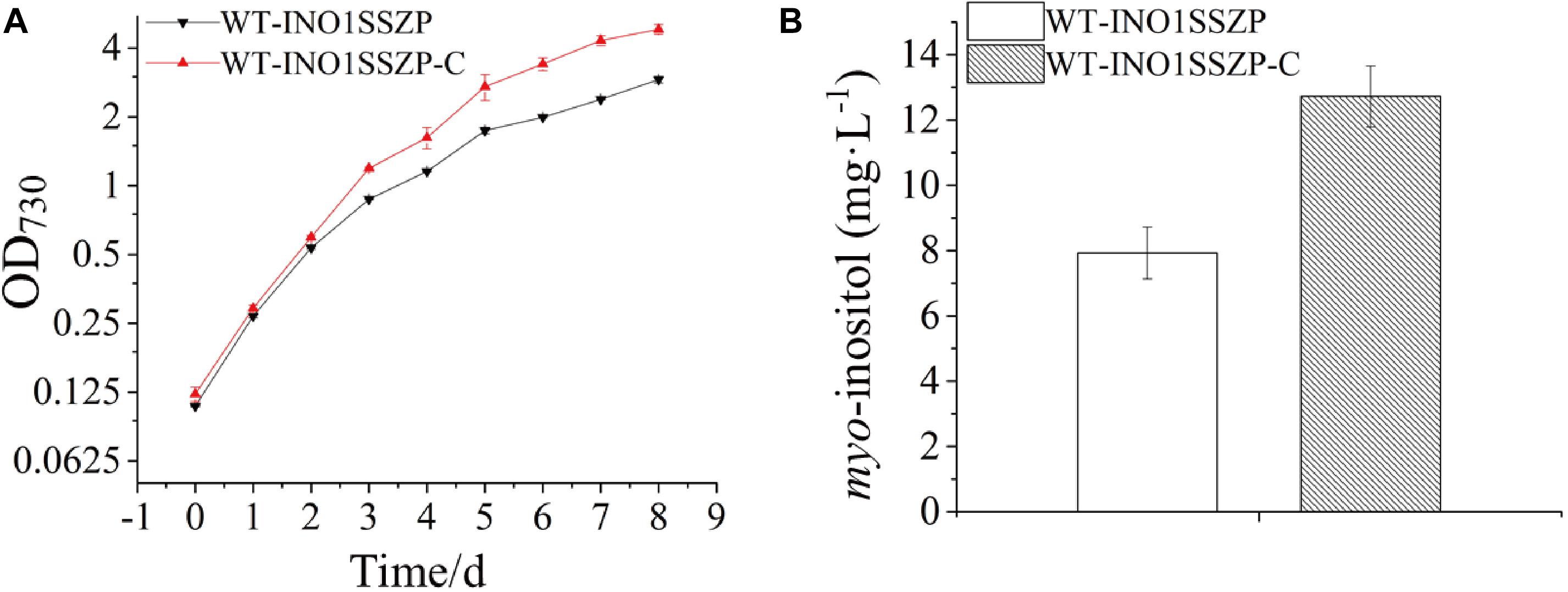

Early studies have demonstrated that NaHCO3 supplementation to cyanobacterial culture is an effective strategy for higher biomass and more production of target chemicals (Johnson et al., 2016; Wang et al., 2016). Thus, the effects of increased NaHCO3 supply on MI production in the engineered strain were evaluated. Given that the strain WT-INO1SSZP showed the highest MI production capacity, it was chosen as the target for cultivation optimization. After supplementing 0.5 ml 1.0 M NaHCO3 every 24 h into the BG-11, the engineered Synechocystis strain WT-INO1SSZP showed a faster growth rate compared with their corresponding strains without NaHCO3 supplementation (Figure 7A). Meanwhile, the MI production in the strain WT-INO1SSZP was increased to 12.72 mg L–1 (Figure 7B), demonstrating that the enhanced carbon supply could significantly increase the MI production.

Figure 7. myo-inositol quantitation and growth curves in the engineered Synechocystis strain WT-INO1SSZP, cultivated with or without NaHCO3. The error bars represent the standard deviation of three biological replicates for each sample. WT-INO1SSZP represents cultivation without NaHCO3, while WT-INO1SSZP-C represents cultivation with NaHCO3. (A) Growth curves of WT-INO1SSZP with or without NaHCO3. (B) myo-inositol quantitation in WT-INO1SSZP after cultivation for 8 days with or without NaHCO3.

Early studies have shown the feasibility of directly converting light energy and CO2 into green fuels and chemicals in Synechocystis (Gao et al., 2016; Wang et al., 2016). In this study, we engineered a photoautotrophic cyanobacterial system for the production of MI directly from CO2. Previously, INO1 and myo-inositol 1-phosphate synthase were overexpressed from S. cerevisiae in E. coli (Brockman and Prather, 2015), successfully achieving a heterologous production of MI. Consistently, we found that the overexpression of INO1 led to detectable MI biosynthesis in Synechocystis. After the overexpression of sll1329 and sll1383 (encoding myo-inositol-1-monophosphatase), intracellular MI concentration was slightly increased by ∼45.6% in WT-INO1SS than that in WT-INO1. A significant overexpression for sll1329 and sll1383 on a transcriptional level was demonstrated via qRT-PCR (Figure 3), suggesting that IMP might not be the limiting step for MI synthesis in Synechocystis.

G6P was the direct precursor for MI synthesis; meanwhile, it is a fundamental metabolite to support microbial survival. Though the manipulation of carbon flux toward the G6P pool has previously been demonstrated to be an effective strategy to enhance the production of its derivatives in various microorganisms (Brockman and Prather, 2015; Gupta et al., 2017), deletion of the pentose phosphate pathway (PPP)-related gene zwf could totally block the essential pathways and cause severe growth inhibition. Thus, a suitable and efficient genetic tool for gene knockdown is valuable. Previously, the small RNA regulatory tool was demonstrated as feasible and efficient in regulating genes, especially essential genes, such as redirecting the carbon flux to the key precursor malonyl-CoA in Synechocystis (Sun et al., 2018b). In this work, the sRNA tool was utilized to decrease the flux to glycolysis and pentose phosphate pathway based on the theophylline-inducible riboswitch. Interestingly, the down-regulation of either PPP (zwf) or glycolysis pathway (pgi or pfkA) led to an ∼2-fold increase in MI production compared to that of WT-INO1SS, while the combined regulation of the two pathways realized a synergetic effect with ∼5.58-fold increase of MI production. The results demonstrated that control of the competing pathways and driving more carbon into MI biosynthesis were important for MI production. In the future, attempts could be made to target more “carbon-consuming pathways” like glycogen, fatty acids, as well as acetate synthesis to direct more carbon into MI synthesis (Zhou et al., 2014). Meanwhile, in this study, the control for competing pathways was achieved using an inducible riboswitch, which needs additional inducers at specific time points. As artificial quorum sensing systems allowed cell growth at low cell density and induced specific gene expressions at high cell density automatically (Kim et al., 2017; Gu et al., 2020), it may represent a more suitable switch to control the essential pathways and is worth investigating in the future.

Limiting the carbon flux into other pathways was efficient for enhancing MI synthesis, while improving the total carbon fixation could also be important as it provides more carbon precursors. Previously, the overexpression of genes encoding ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase or extra bicarbonate transporters were both demonstrated as feasible for enhancing carbon fixation and biomass accumulation in Synechocystis (Atsumi et al., 2009; Kamennaya et al., 2015; Liang and Lindblad, 2016). In addition, supplementation of inorganic carbon like CO2 or bicarbonate has been considered as a more direct strategy for carbon fixation reinforcement and production improvement (Wang et al., 2013). Consistently, supplementation of bicarbonate for the cultivation of WT-INO1SSZP further reached a ∼1.6-fold increase in MI production. Nevertheless, the final production in Synechocystis is still much lower than that in other heterotrophic microorganisms like B. subtilis and E. coli (Brockman and Prather, 2015; Michon et al., 2020), suggesting that less than enough carbon sources and precursors were fed into the synthetic pathway. In the future, cultivation supplemented with organic carbon sources like glucose, used for heterotrophic organisms or photomixotrophic, could also be a feasible strategy (Vassilev et al., 2017; Qian et al., 2020). In this work, our preliminary results showed that supplementation of 5 mM glucose could significantly improve the growth and MI production of WT-INO1SS-ZP, finally reaching a production at 21.74 mg L–1 after 8 days of cultivation (Supplementary Figure S6), which also supported the argument that more carbon sources and precursors are needed to achieve high MI production.

The relatively lower growth rate of Synechocystis could also be an important limiting factor for MI production. Previously, a fast-growing cyanobacterium named Synechococcus elongatus UTEX 2973 (Yu et al., 2015; Lin et al., 2020) was isolated, whose shortest doubling time can reach 1.5 h at 41°C under continuous 1,500 μmol photons m–2 s–1 white light with 5% CO2, close to that of S. cerevisiae (1.67 h). More importantly, the potential of S. elongatus UTEX 2973 for products like sucrose was found to be 6- to 26-fold compared with those in traditional cyanobacterial chassis like Synechocystis, Anabaena sp. PCC 7120, and S. elongatus PCC 7942 (Song et al., 2016), suggesting its application potential for chemical synthesis. Similarly, other fast-growing cyanobacteria like S. elongatus PCC 11802 and Synechococcus sp. PCC 11901 were identified recently, offering more candidates as chassis for MI production in the future (Jaiswal et al., 2020; Wlodarczyk et al., 2020).

In this study, we engineered the model cyanobacterium Synechocystis for the sustainable production of MI. With the expression of IPS and IMP genes, simultaneous knockdown of three genes related to competing pathways, and cultivation optimization, photosynthetic production of MI directly from CO2 was achieved, with a production of up to 12.72 mg L–1 after cultivation for 8 days, which represents an increase of ∼12 times compared with initial MI-producing WT-INO1. The study presented here demonstrated the feasibility of converting CO2 directly into MI in cyanobacterial chassis.

All datasets generated for this study are included in the article/Supplementary Material.

XW conducted the experiments, analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript. LC and TS designed the research and revised the manuscript. JL helped with some of the experiments. WZ designed the research and revised the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

This research was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 31901017, 31770035, 31972931, 91751102, 31770100, 31901016, and 21621004), the National Key Research and Development Program of China (Nos. 2019YFA0904600, 2018YFA0903600, and 2018YFA0903000), and the Tianjin Synthetic Biotechnology Innovation Capacity Improvement Project (No. TSBICIP-KJGG-007).

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmicb.2020.566117/full#supplementary-material

Atsumi, S., Higashide, W., and Liao, J. C. (2009). Direct photosynthetic recycling of carbon dioxide to isobutyraldehyde. Nat. Biotechnol. 27, 1177–1180. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1586

Berridge, M. J. (2009). Inositol trisphosphate and calcium signalling mechanisms. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1793, 933–940. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2008.10.005

Brockman, I. M., and Prather, K. L. J. (2015). Dynamic knockdown of E. coli central metabolism for redirecting fluxes of primary metabolites. Metab. Eng. 28, 104–113. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2014.12.005

Chatterjee, A., Dastidar, K. G., Maitra, S., Das-Chatterjee, A., Dihazi, H., Eschrich, K., et al. (2006). sll1981, an acetolactate synthase homologue of Synechocystis sp. PCC6803, functions as L-myo-inositol 1-phosphate synthase. Planta 224, 367–379. doi: 10.1007/s00425-006-0221-4

Chatterjee, A., Majee, M., Ghosh, S., and Majumder, A. L. (2004). sll1722, an unassigned open reading frame of Synechocystis PCC 6803, codes for L-myo-inositol 1-phosphate synthase. Planta 218, 989–998. doi: 10.1007/s00425-003-1190-5

Cheng, F., Han, L., Xiao, Y., Pan, C., Li, Y., Ge, X., et al. (2019). d- chiro-inositol ameliorates high fat diet-induced hepatic steatosis and insulin resistance via PKCepsilon-PI3K/AKT pathway. J. Agric. Food Chem. 67, 5957–5967. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.9b01253

Fujisawa, T., Fujinaga, S., and Atomi, H. (2017). An in vitro enzyme system for the production of myo-inositol from starch. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 83:e00550-17. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00550-17

Gao, X., Sun, T., Pei, G., Chen, L., and Zhang, W. (2016). Cyanobacterial chassis engineering for enhancing production of biofuels and chemicals. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 100, 3401–3413. doi: 10.1007/s00253-016-7374-2

Gu, F., Jiang, W., Mu, Y., Huang, H., Su, T., Luo, Y., et al. (2020). Quorum sensing-based dual-function switch and its application in solving two key metabolic engineering problems. ACS Synth. Biol. 9, 209–217. doi: 10.1021/acssynbio.9b00290

Gupta, A., Reizman, I. M., Reisch, C. R., and Prather, K. L. (2017). Dynamic regulation of metabolic flux in engineered bacteria using a pathway-independent quorum-sensing circuit. Nat. Biotechnol. 35, 273–279. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3796

Hansen, C. A., Dean, A. B., Draths, K. M., and Frost, J. W. (1999). Synthesis of 1,2,3,4-tetrahydroxybenzene from d-glucose: exploiting myo-inositol as a precursor to aromatic chemicals. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 121, 3799–3800. doi: 10.1021/ja9840293

Jaiswal, D., Sengupta, A., Sengupta, S., Madhu, S., Pakrasi, H. B., and Wangikar, P. P. (2020). A novel cyanobacterium Synechococcus elongatus PCC 11802 has distinct genomic and metabolomic characteristics compared to its neighbor PCC 11801. Sci. Rep. 10:191. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-57051-0

Januszewski, M., Issat, T., Jakimiuk, A. A., Santor-Zaczynska, M., and Jakimiuk, A. J. (2019). Metabolic and hormonal effects of a combined Myo-inositol and d-chiro-inositol therapy on patients with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS). Ginekol. Pol. 90, 7–10. doi: 10.5603/GP.2019.0002

Johnson, T. J., Zahler, J. D., Baldwin, E. L., Zhou, R., and Gibbons, W. R. (2016). Optimizing cyanobacteria growth conditions in a sealed environment to enable chemical inhibition tests with volatile chemicals. J. Microbiol. Methods 126, 54–59. doi: 10.1016/j.mimet.2016.05.011

Kamennaya, N. A., Ahn, S., Park, H., Bartal, R., Sasaki, K. A., Holman, H. Y., et al. (2015). Installing extra bicarbonate transporters in the cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. PCC6803 enhances biomass production. Metab. Eng. 29, 76–85. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2015.03.002

Kim, E. M., Woo, H. M., Tian, T., Yilmaz, S., Javidpour, P., Keasling, J. D., et al. (2017). Autonomous control of metabolic state by a quorum sensing (QS)-mediated regulator for bisabolene production in engineered E. coli. Metab. Eng. 44, 325–336. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2017.11.004

Liang, F., and Lindblad, P. (2016). Effects of overexpressing photosynthetic carbon flux control enzymes in the cyanobacterium Synechocystis PCC 6803. Metab. Eng. 38, 56–64. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2016.06.005

Lin, P. C., Zhang, F., and Pakrasi, H. B. (2020). Enhanced production of sucrose in the fast-growing cyanobacterium Synechococcus elongatus UTEX 2973. Sci. Rep. 10:390. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-57319-5

Livak, K. J., and Schmittgen, T. D. (2001). Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods 25, 402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262

Lu, Y., Wang, L., Teng, F., Zhang, J., Hu, M., and Tao, Y. (2018). Production of myo-inositol from glucose by a novel trienzymatic cascade of polyphosphate glucokinase, inositol 1-phosphate synthase and inositol monophosphatase. Enzyme Microb. Technol. 112, 1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.enzmictec.2018.01.006

Ma, K., Thomason, L. A., and McLaurin, J. (2012). scyllo-Inositol, preclinical, and clinical data for Alzheimer’s disease. Adv. Pharmacol. 64, 177–212. doi: 10.1016/b978-0-12-394816-8.00006-4

Michon, C., Kang, C. M., Karpenko, S., Tanaka, K., Ishikawa, S., and Yoshida, K. I. (2020). A bacterial cell factory converting glucose into scyllo-inositol, a therapeutic agent for Alzheimer’s disease. Commun. Biol. 3:93. doi: 10.1038/s42003-020-0814-7

Patra, B., Ghosh Dastidar, K., Maitra, S., Bhattacharyya, J., and Majumder, A. L. (2007). Functional identification of sll1383 from Synechocystis sp PCC 6803 as L-myo-inositol 1-phosphate phosphatase (EC 3.1.3.25): molecular cloning, expression and characterization. Planta 225, 1547–1558. doi: 10.1007/s00425-006-0441-7

Qian, D. K., Geng, Z. Q., Sun, T., Dai, K., Zhang, W., Jianxiong Zeng, R., et al. (2020). Caproate production from xylose by mesophilic mixed culture fermentation. Bioresour. Technol. 308:123318. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2020.123318

Regidor, P. A., Schindler, A. E., Lesoine, B., and Druckman, R. (2018). Management of women with PCOS using myo-inositol and folic acid. New clinical data and review of the literature. Horm. Mol. Biol. Clin. Investig. 34:20170067. doi: 10.1515/hmbci-2017-0067

Roessner, U., Luedemann, A., Brust, D., Fiehn, O., Linke, T., Willmitzer, L., et al. (2001). Metabolic profiling allows comprehensive phenotyping of genetically or environmentally modified plant systems. Plant Cell 13, 11–29. doi: 10.1105/tpc.13.1.11

Song, K., Tan, X., Liang, Y., and Lu, X. (2016). The potential of Synechococcus elongatus UTEX 2973 for sugar feedstock production. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 100, 7865–7875. doi: 10.1007/s00253-016-7510-z

Sun, T., Li, S., Song, X., Diao, J., Chen, L., and Zhang, W. (2018a). Toolboxes for cyanobacteria: recent advances and future direction. Biotechnol. Adv. 36, 1293–1307. doi: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2018.04.007

Sun, T., Li, S., Song, X., Pei, G., Diao, J., Cui, J., et al. (2018b). Re-direction of carbon flux to key precursor malonyl-CoA via artificial small RNAs in photosynthetic Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. Biotechnol. Biofuels 11:26. doi: 10.1186/s13068-018-1032-0

Tanaka, K., Tajima, S., Takenaka, S., and Yoshida, K. (2013). An improved Bacillus subtilis cell factory for producing scyllo-inositol, a promising therapeutic agent for Alzheimer’s disease. Microb. Cell Fact. 12:124. doi: 10.1186/1475-2859-12-124

Thomas, M. P., Mills, S. J., and Potter, B. V. (2016). The “Other” inositols and their phosphates: synthesis, biology, and medicine (with recent advances in myo-inositol chemistry). Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 55, 1614–1650. doi: 10.1002/anie.201502227

Vassilev, N., Malusa, E., Requena, A. R., Martos, V., Lopez, A., Maksimovic, I., et al. (2017). Potential application of glycerol in the production of plant beneficial microorganisms. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 44, 735–743. doi: 10.1007/s10295-016-1810-2

Wang, B., Pugh, S., Nielsen, D. R., Zhang, W., and Meldrum, D. R. (2013). Engineering cyanobacteria for photosynthetic production of 3-hydroxybutyrate directly from CO2. Metab. Eng. 16, 68–77. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2013.01.001

Wang, Y., Sun, T., Gao, X., Shi, M., Wu, L., Chen, L., et al. (2016). Biosynthesis of platform chemical 3-hydroxypropionic acid (3-HP) directly from CO2 in cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. Metab. Eng. 34, 60–70. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2015.10.008

Wlodarczyk, A., Selao, T. T., Norling, B., and Nixon, P. J. (2020). Newly discovered Synechococcus sp. PCC 11901 is a robust cyanobacterial strain for high biomass production. Commun. Biol. 3:215. doi: 10.1038/s42003-020-0910-8

You, C., Shi, T., Li, Y., Han, P., Zhou, X., and Zhang, Y. P. (2017). An in vitro synthetic biology platform for the industrial biomanufacturing of myo-inositol from starch. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 114, 1855–1864. doi: 10.1002/bit.26314

Yu, J., Liberton, M., Cliften, P. F., Head, R. D., Jacobs, J. M., Smith, R. D., et al. (2015). Synechococcus elongatus UTEX 2973, a fast growing cyanobacterial chassis for biosynthesis using light and CO(2). Sci. Rep. 5:8132. doi: 10.1038/srep08132

Zhou, J., Zhang, H., Meng, H., Zhang, Y., and Li, Y. (2014). Production of optically pure d-lactate from CO2 by blocking the PHB and acetate pathways and expressing d-lactate dehydrogenase in cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. Process Biochem. 49, 2071–2077. doi: 10.1016/j.procbio.2014.09.007

Keywords: myo-inositol, cyanobacteria, photosynthetic cell factory, small RNA tools, synthetic biology

Citation: Wang X, Chen L, Liu J, Sun T and Zhang W (2020) Light-Driven Biosynthesis of myo-Inositol Directly From CO2 in Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. Front. Microbiol. 11:566117. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2020.566117

Received: 27 May 2020; Accepted: 11 September 2020;

Published: 29 September 2020.

Edited by:

Xuefeng Lu, Qingdao Institute of Bioenergy and Bioprocess Technology (CAS), ChinaReviewed by:

Stephan Klähn, Helmholtz Centre for Environmental Research (UFZ), GermanyCopyright © 2020 Wang, Chen, Liu, Sun and Zhang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Tao Sun, dHN1bkB0anUuZWR1LmNu; Weiwen Zhang, d3d6aGFuZzhAdGp1LmVkdS5jbg==

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.