95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Microbiol. , 02 October 2020

Sec. Fungi and Their Interactions

Volume 11 - 2020 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2020.542961

This article is part of the Research Topic Plant Pathogenic Fungi: Molecular Systematics, Genomics and Evolution View all 16 articles

The emergence of new physiological races of Puccinia striiformis f. sp. tritici (Pst) causing wheat stripe rust can lead to the loss of resistance of wheat cultivars to stripe rust, thus resulting in severe losses in wheat yield. In this study, after the germination of urediospores of three Pst strains including the original strain (CYR32, a dominant physiological race of Pst in China) and two virulence-mutant strains (CYR32-5 and CYR32-61) acquired from CYR32 via UV-B radiation, proteomic analysis based on isobaric tags for relative and absolute quantification (iTRAQ) technology was performed on the strains. A total of 2,271 proteins were identified, and 59, 74, and 64 differentially expressed proteins (DEPs) were acquired in CYR32-5 vs. CYR32, CYR32-61 vs. CYR32, and CYR32-61 vs. CYR32-5, respectively. The acquired DEPs were mainly involved in energy metabolism, carbon metabolism, and cellular substance synthesis. Furthermore, quantitative reverse transcription PCR assays were used to determine the relative expression of the 6, 7, and 1 DEPs of CYR32-5 vs. CYR32, CYR32-61 vs. CYR32, and CYR32-61 vs. CYR32-5, respectively, at the transcriptional level. The relative expression levels of one, five, and one gene, respectively, encoding the DEPs, were consistent with the corresponding protein abundance determined by iTRAQ technology. Compared with CYR32, the DEPs associated with energy metabolism and stress—including E3JWK6, F4S0Z3, and A8N2Q4—were up-regulated in the mutant strains. The results indicated that the virulence-mutant strains CYR32-5 and CYR32-61 had more tolerance to stress than the original strain CYR32. The results obtained in this study are of great significance for exploring the virulence variation mechanisms of Pst, monitoring the changes in Pst populations, breeding new disease-resistant wheat cultivars, and managing wheat stripe rust sustainably.

Stripe rust (yellow rust), caused by Puccinia striiformis f. sp. tritici (Pst), is a devastating wheat disease in wheat producing regions worldwide (Li and Zeng, 2002; Line, 2002; Chen, 2005; Wan et al., 2007; Chen et al., 2014; Wang et al., 2014). It can have a serious impact on wheat production, and can cause yield losses of 10–30% or even no yield once a disease outbreak or epidemic occurs (Li and Zeng, 2002; Wan et al., 2004, 2007). Pst can mutate in many ways to produce new strains or physiological races (Ma et al., 1993; Li and Zeng, 2002; Jin et al., 2010; Hu et al., 2014; Kang et al., 2015). The emergence of new physiological races can lead to the loss of stripe rust resistance in wheat cultivars and cause periodic epidemics of the disease (Li and Zeng, 2002; Chen, 2007; Chen et al., 2014; Hu et al., 2014; Kang et al., 2015). Hence, exploring the mechanisms of virulence variation of Pst can provide an important basis for wheat breeding and control of stripe rust.

Ultraviolet-B (UV-B) radiation (280–320 nm) is a part of sunlight, and can affect living things on Earth’s surface. In most reported studies, UV-B radiation has been used as a stress condition, and many aspects of its effects on living organisms have been investigated, including physiological and biochemical effects (Fargues et al., 1996; Jansen et al., 1998; Fernandes et al., 2007; Wargent and Jordan, 2013; Braga et al., 2015), genetic effects (Kumar et al., 2004; Braga et al., 2015), and effects on proteins (Wu X. C. et al., 2011; Trentin et al., 2015; Gao et al., 2019). As the main propagules of wheat stripe rust, Pst urediospores, in high-altitude areas of northwestern China with high-intensity UV-B radiation and in processes of long-distance dispersal with upper air flows, are affected by UV-B radiation, and virulence-mutant strains may be induced (Li and Zeng, 2002; Cheng et al., 2014; Hu et al., 2014; Kang et al., 2015).

Reported studies on the effects of UV-B radiation on Pst have focused on changes in the epidemiological components of Pst after UV-B radiation (Jing et al., 1993; Cheng et al., 2014), screening of virulence-mutant strains of Pst by UV-B radiation (Shang et al., 1994; Huang et al., 2005; Wang et al., 2009; Zhao et al., 2019), and random amplified polymorphic DNA (RAPD) analysis of the UV-B-induced virulence-mutant strains of Pst (Huang et al., 2005; Wang et al., 2009). An important study on Pst (Zheng et al., 2013) revealed the whole genome information of CYR32, a dominant physiological race of Pst in China, using high-throughput sequencing technology, which provided an important basis for the identification and functional verification of Pst proteins. More recently, a proteomics method based on isobaric tags for relative and absolute quantification (iTRAQ) technology, combining the isotope labeling method and tandem mass spectrometry, has been used to identify and quantify differentially expressed proteins (DEPs) between different proteomes, particularly in studies on plant-pathogen interactions (Fu et al., 2016; Xu et al., 2017; OuYang et al., 2018). Using this methodology, Zhao et al. (2016) investigated the difference between the proteomes of the urediospores of CYR32 before and after germination. The results showed that most of the DEPs were involved in biological processes such as carbon metabolism, energy metabolism, and transport. In our previous study (Zhao et al., 2018), the urediospores of three physiological races of Pst in China—CYR31, CYR32, and CYR33—were irradiated with a dose of UV-B radiation at which the relative lethal rate of the urediospores of each physiological race was 90%. Proteomic analysis of the irradiated urediospores, using methods based on iTRAQ technology, was then performed to explore the effects of UV-B radiation on Pst at the protein level. The results showed that most of the identified DEPs were mainly involved in energy metabolism, substance metabolism, and DNA biosynthesis. However, there are no reports on the differences in the level of protein expression between the original strains of Pst and the UV-B-induced virulence-mutant strains.

In our previous study (Zhao et al., 2019), two UV-B-induced virulence-mutant strains, CYR32-5 and CYR32-61, were screened from the UV-B-irradiated urediospores of CYR32 on the seedlings of the wheat cultivar Guinong 22. In this study, after germination of the urediospores of the original strain (CYR32) and the two UV-B-induced virulence-mutant strains (CYR32-5 and CYR32-61), proteins were extracted from the germinated urediospores and germ tubes, the DEPs among the proteomes of the three Pst strains were screened by using the proteomics method based on iTRAQ technology, and then the acquired DEPs were subjected to COG (Cluster of Orthologous Groups) annotations, KEGG (Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes) pathway analyses, and quantitative reverse transcription PCR (qRT-PCR) assays. This study is of great significance for exploring mechanisms of Pst virulence variation, and it can provide a reference for wheat resistance breeding and control of wheat stripe rust.

In the previous study (Zhao et al., 2019), the urediospores of the Pst physiological race CYR32 were irradiated with UV-B radiation under a radiation dose (the radiation intensity was 250 μw/cm2, and the radiation time was 95 min) for which the relative lethal rate of urediospores was approximately 90% (i.e., the relative germination rate of urediospores was approximately 10%); then the irradiated urediospores were inoculated on the seedlings of Guinong 22 to screen virulence-mutant strains. Finally, two virulence-mutant strains named CYR32-5 and CYR32-61, with stable infection types on Guinong 22 throughout four successive generations, were obtained. In this study, the original strain of the Chinese physiological race CYR32 of Pst and the two virulence-mutant strains (CYR32-5 and CYR32-61) were used. The wheat cultivar Mingxian 169, which is susceptible to all known Chinese physiological races of Pst, was used for Pst multiplication. Multiplication of the urediospores of each Pst strain was conducted in an artificial climate chamber (environmental parameters: light time, 12 h/d; light intensity, 10,000 lux; temperature, 11–13°C; and relative humidity, 60–70%) using the method described by Cheng et al. (2014).

Fresh urediospores of each of the three strains CYR32, CYR32-5, and CYR32-61 were collected from the diseased leaves of Mingxian 169 seedlings. For each strain, a spore suspension with a concentration of 2.5 mg/mL was prepared with 0.2% Tween-80 solution. Then, 4 mL of the spore suspension was transferred into a Petri dish (16 cm in diameter) containing 1% water agar medium. The urediospores (10 mg) contained in the suspension were evenly scattered in the Petri dish. When the suspension was almost dry, the Petri dish was sealed with plastic wrap and incubated for 10 h at 9°C in a dark environment. After incubation, a small agar block was picked up and placed on a glass slide for microscopic observation. At least 300 urediospores were checked, and the germination rate of the urediospores was recorded. A urediospore with a germ tube longer than half of the diameter of the urediospore was regarded as germinated. If the germination rate of the urediospores was more than 90%, the urediospores and germ tubes on the surface of the water agar medium were gently collected with a cover glass. For each Pst strain, the urediospores and germ tubes collected from five Petri dishes (approximately 50 mg in total) were treated as a sample.

In total, two samples of CYR32, three samples of CYR32-5, and three samples of CYR32-61 were acquired for protein extraction. Grinding tools were pre-cooled with liquid nitrogen, and then each of the prepared samples was pulverized with liquid nitrogen in a mortar and pestle. The pulverized sample was suspended in a trichloroacetic acid (TCA) and acetone solution (TCA:acetone = 1:10, w/v; pre-cooled at −20°C) and then precipitated for 2 h at −20°C. After centrifugation at 4°C under 20,000 × g for 30 min, the supernatant was discarded, and the precipitate was suspended in pre-cooled pure acetone, and then precipitated for 30 min at −20°C prior to centrifugation at 4°C under 20,000 × g for another 30 min. This process was repeated several times until the precipitate was substantially white. The precipitate was resuspended in a lysis buffer (8 M urea, 30 mM 4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid, 1 mM phenylmethanesulfonyl fluoride, 2 mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid, and 10 mM dithiothreitol) and sonicated for 5 min (pulse on 2 s, pulse off 3 s, power 180 W), followed by centrifugation at 20,000 × g for 30 min. The supernatant was collected and added to dithiothreitol to a final concentration of 10 mM. After incubation in a water bath at 56°C for 1 h, iodoacetamide was quickly added, to a final concentration of 55 mM. After incubation for 1 h in a dark environment, the supernatant solution was supplemented with a fourfold volume of pre-chilled acetone, and then precipitated at −20°C for more than 3 h. After centrifugation at 4°C under 20,000 × g for 30 min, the precipitate was dissolved in 400 μL of digestion buffer to a final concentration of 50% triethylammonium bicarbonate (TEAB) and 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS). Subsequently, sonication was performed for 3 min with a pulse on time of 2 s and a pulse off time of 3 s at an ultrasonic power of 180 W, and centrifugation was performed for 30 min at 4°C and 20,000 × g. Finally, the supernatant was obtained, and the protein concentration was quantified using the Bradford assay (Supplementary Table 1).

From each sample solution, 100 μg of protein was transferred to a new clean centrifuge tube. The TEAB solution (0.1% SDS) was added to make the protein solution of each sample in the new tube up to the same volume. After adding 3.3 μL of trypsin (1 μg/μL) to the tube for protein digestion, the solution was incubated in a water bath at 37°C for 24 h. Subsequently, the tube was supplemented with 1 μL of trypsin (1 μg/μL), and the mixture in the tube was incubated in a water bath at 37°C for 12 h. After lyophilization of the mixture, 30 μL of TEAB (ddH2O:TEAB = 1:1, v/v) was added to the tube to dissolve the peptides. Using an iTRAQ® Reagent-8Plex Multiplex Kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, United States), peptides from the eight samples were labeled with the iTRAQ tags as follows: CYR32 (tags 113 and 114), CYR32-5 (tags 115, 116, and 117), and CYR32-61 (tags 118, 119, and 121), respectively (Supplementary Table 1).

The solution containing labeled peptides of each sample was diluted tenfold with buffer A (25% acetonitrile (ACN), 10 mM KH2PO4, pH 3.0), and the pH was adjusted to 3.0 with phosphoric acid. After centrifugation for 15 min at 15,000 × g, the labeled peptides in the supernatant were fractionated using a Phenomenex Luna SCX column (250 mm × 4.60 mm, 100Å) with a high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) system (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, United States) at a flow rate of 1 mL/min. The system was equilibrated for 10–20 min with buffer A at a flow rate of 1 mL/min, prior to strong cation exchange fractionation. The HPLC gradient was as follows: 0–45 min, 100% buffer A; 45–46 min, 0–5% buffer B (25% ACN, 2 M KCl, 10 mM of KH2PO4, pH 3.0); 46–66 min, 5–30% buffer B; 66–71 min, 30–50% buffer B; 71–76 min, 50% buffer B; 76–81 min, 50–100% buffer B; 81–91 min, 100% buffer B. Absorbance was recorded at 214 nm. The eluted peptides were desalted with a Strata-X C18 column (Phenomenex, Torrance, CA, United States), and then dried by vacuum centrifugation at a low temperature.

The desalted, dried peptides were resuspended with solvent A (0.1% formic acid (FA) in H2O), transferred to an Acclaim PePmap C18-reversed phase column (75 μm × 2 cm, 3 μm, 100 Å, Thermo Scientific), and then separated using a Dionex Ultimate 3000 Nano LC system with a C18 reversed phase column (75 μm × 10 cm, 5 μm, 300 Å, Agela Technologies) at a flow rate of 400 nL/min. The mobile phases were solvent A and solvent B (0.1% FA in ACN). The elution gradient was as follows: 0–10 min, 5% solvent B; 10–40 min, 5–30% solvent B; 40–45 min, 30–60% solvent B; 45–48 min, 60–80% solvent B; 48–55 min, 80% solvent B; 55–58 min, 80–5% solvent B; 58–65 min, 5% solvent B. Subsequently, 16 pre-isolated and purified components of peptides were detected using a Q-Exactive mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, United States) with set parameters as follows: polarity, positive ion mode; MS scan range, 350–2000 m/z; MS/MS scan resolution, 17,500; capillary temperature, 320°C; ion source voltage, 1,800 V; MS/MS acquisition modes, higher collision energy dissociation; normalized collision energy, 28.

The acquired raw mass spectrometry data were processed using the PD (Proteome Discoverer 1.3; Thermo Fisher Scientific, San Jose, CA, United States) software with the following parameters: mass range of parent ion, 350–6,000 Da; minimum number of peaks in MS/MS spectrum, 10; signal-to-noise ratio (S/N) threshold, 1.5. The spectra extracted using the PD software were searched against the Basidiomycota_UniProt database using Mascot 2.3.0 (Matrix Science, London, United Kingdom) with the following identification parameters: fixed modification, carbamidomethyl (C); variable modification, oxidation (M), Gln→Pyro-Glu (N-term Q), iTRAQ 8 plex (K), iTRAQ 8 plex (Y), iTRAQ 8 plex (N-term); peptide tolerance, 15 ppm; MS/MS tolerance, 20 mmu; max missed cleavages, 1; enzyme, trypsin. Based on the Mascot search results and the extracted spectra, protein quantitative analysis was performed using the PD software with the following parameters: protein ratio type, median; minimum peptides, 1; normalization method, median; P-value, < 0.05; ratio, ≥ 1.2. In this study, proteins with at least two unique peptides, scores more than 70, P-values less than 0.05, and fold changes more than 1.2 or less than 0.83 were identified as DEPs between the different Pst strains. The fold changes of the up-regulated DEPs were more than 1.2, and those of the down-regulated DEPs were less than 0.83. For the convenience of expression, CYR32-5 vs. CYR32, CYR32-61 vs. CYR32, or CYR32-61 vs. CYR32-5 was used to represent the combination in which the proteome of the former was compared with that of the latter to screen DEPs.

Functional annotations of the proteins were carried out using the Blast2Go program1 (Conesa et al., 2005). The COG annotations of proteins were conducted using WebMGA2 (Wu S. T. et al., 2011). The annotations of the identified DEPs at the biological pathway level were performed using the KEGG database3. The KOBAS 2.0 software was used to annotate pathways by comparing similar protein sequences (Xie et al., 2011). Signal peptides were predicted and analyzed using the SignalP 5.0 program4 (Armenteros et al., 2019).

The mass spectrometry proteomics data have been deposited to the ProteomeXchange Consortium5 via the iProX partner repository (Ma et al., 2019) with the dataset identifier PXD018136.

Using the method described above, 20 mg of the germinated urediospores and germ tubes of each of the three strains CYR32, CYR32-5, and CYR32-61 were collected and treated as a sample. Total RNA from each sample was extracted using the RNeasy kit (Omega) according to the manufacturer’s instructions, and then genomic DNA contaminants were removed by DNase I (RNase-free) treatment. The synthesis of the first-strand cDNA was performed by reverse transcription using the PrimeScriptTM RT Master Mix kit (Takara, Dalian, China). Specific primers were designed for the selected DEPs according to their corresponding coding sequences using NCBI Primer-BLAST6 (Table 1). Pst β-tubulin gene TUBB (GenBank accession No. EG374306) was used as the reference gene, and the corresponding primer reported by Huang et al. (2012) (as shown in Table 1) was used in this study. SYBR Green real-time fluorescence quantitative PCR assays were performed using an Applied Biosystems ABI Model 7500 Real Time PCR system. The qRT-PCR reactions were carried out in a total 20 μL volume of reaction mixture containing 10 μL 2 × SYBR Premix DimerEraser, 0.6 μL forward primer (10 μM), 0.6 μL reverse primer (10 μM), 2.0 μL template DNA, 6.4 μL sterile purified water, and 0.4 μL 50 × ROX Reference Dye or Dye II. The amplification procedure was as follows: pre-denaturation at 95°C for 30 s, followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 5 s, 55°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 30 s. The relative gene expression levels were calculated using the 2−ΔΔCT method described by Livak and Schmittgen (2001). The experiment was carried out with three biological replicates.

A total of 337,731 spectra were acquired from the eight samples of the three Pst strains, and 52,290 spectra were matched by searching against the Basidiomycota_UniProt database using Mascot 2.3.0 (false discovery rate < 1%). In total, 8,882 peptides and 2,271 proteins were obtained (Supplementary Table 2).

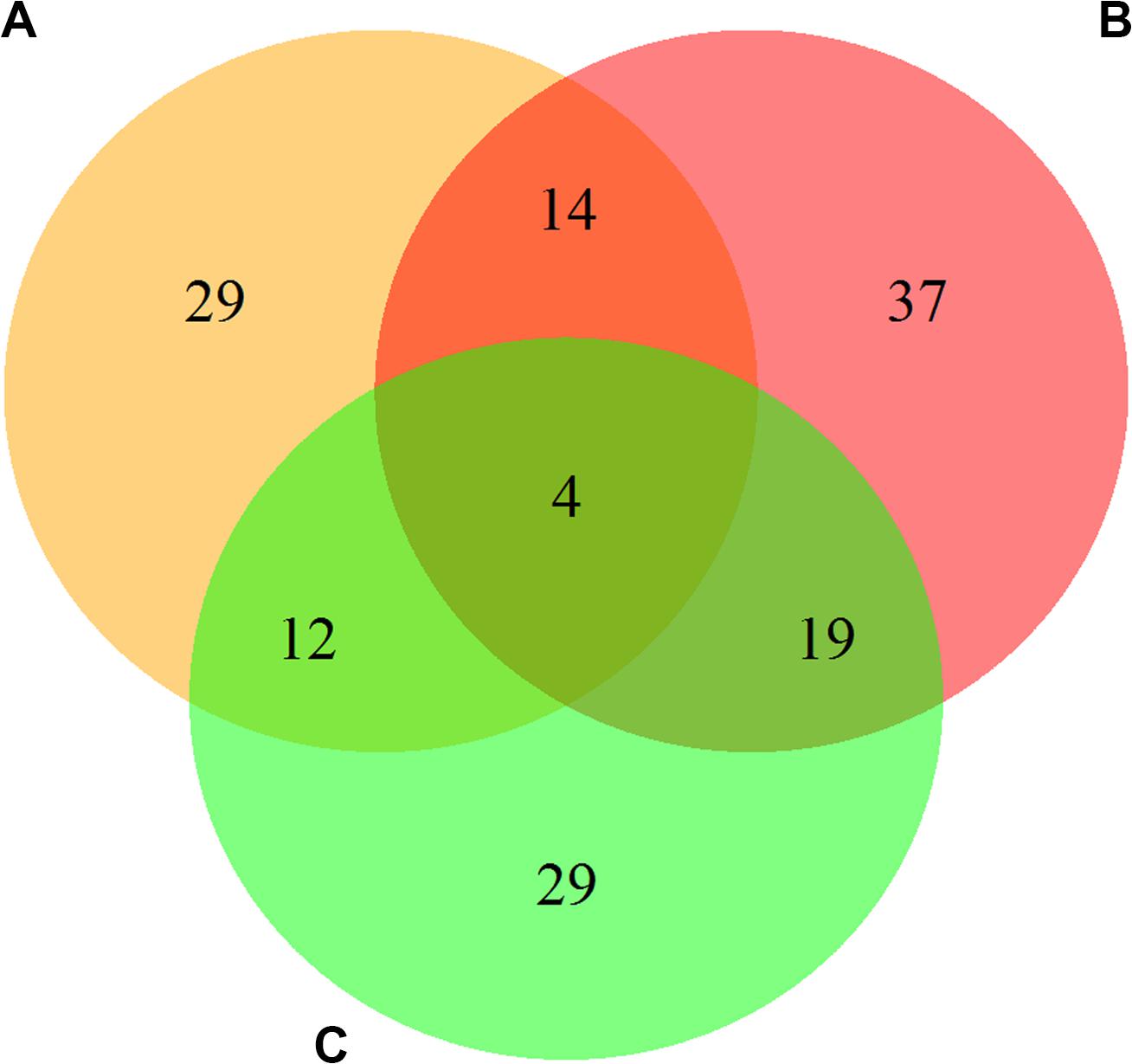

The results of screening the DEPs in the urediospores and germ tubes after germination in three combinations, CYR32-5 vs. CYR32, CYR32-61 vs. CYR32, and CYR32-61 vs. CYR32-5, are shown in Figure 1. As shown in Figure 1, 59 DEPs were obtained in the combination CYR32-5 vs. CYR32, of which 35 proteins were up-regulated and 24 proteins were down-regulated, and the DEPs E3JUB4 and Q9C1C1 (3.39%) were predicted to contain signal peptides. Seventy-four DEPs were obtained in the combination CYR32-61 vs. CYR32, of which 43 proteins were up-regulated and 31 proteins were down-regulated, and the DEPs Q9C1C1, R7SW21, E3JQF7, E3JUB4, E3JSA3, E3KXP2, and E3K3X8 (9.46%) were predicted to contain signal peptides. Sixty-four DEPs were obtained in the combination CYR32-61 vs. CYR32-5, of which 40 were up-regulated and 24 were down-regulated, and the DEPs E3K302, E3KDD8, E3JSA3, and E3JQF7 (6.25%) were predicted to contain signal peptides. In total, 144 DEPs were obtained in the three comparison combinations, of which four were common in CYR32-5 vs. CYR32, CYR32-61 vs. CYR32, and CYR32-61 vs. CYR32-5. The DEPs that were predicted to contain signal peptides may be secretary proteins or membrane proteins.

Figure 1. The overlap among the differentially expressed proteins in the germinated Pst urediospores in the combinations CYR32-5 vs. CYR32 (A), CYR32-61 vs. CYR32 (B), and CYR32-61 vs. CYR32-5 (C) (For each combination, the proteome of the former was compared with that of the latter to screen the differentially expressed proteins).

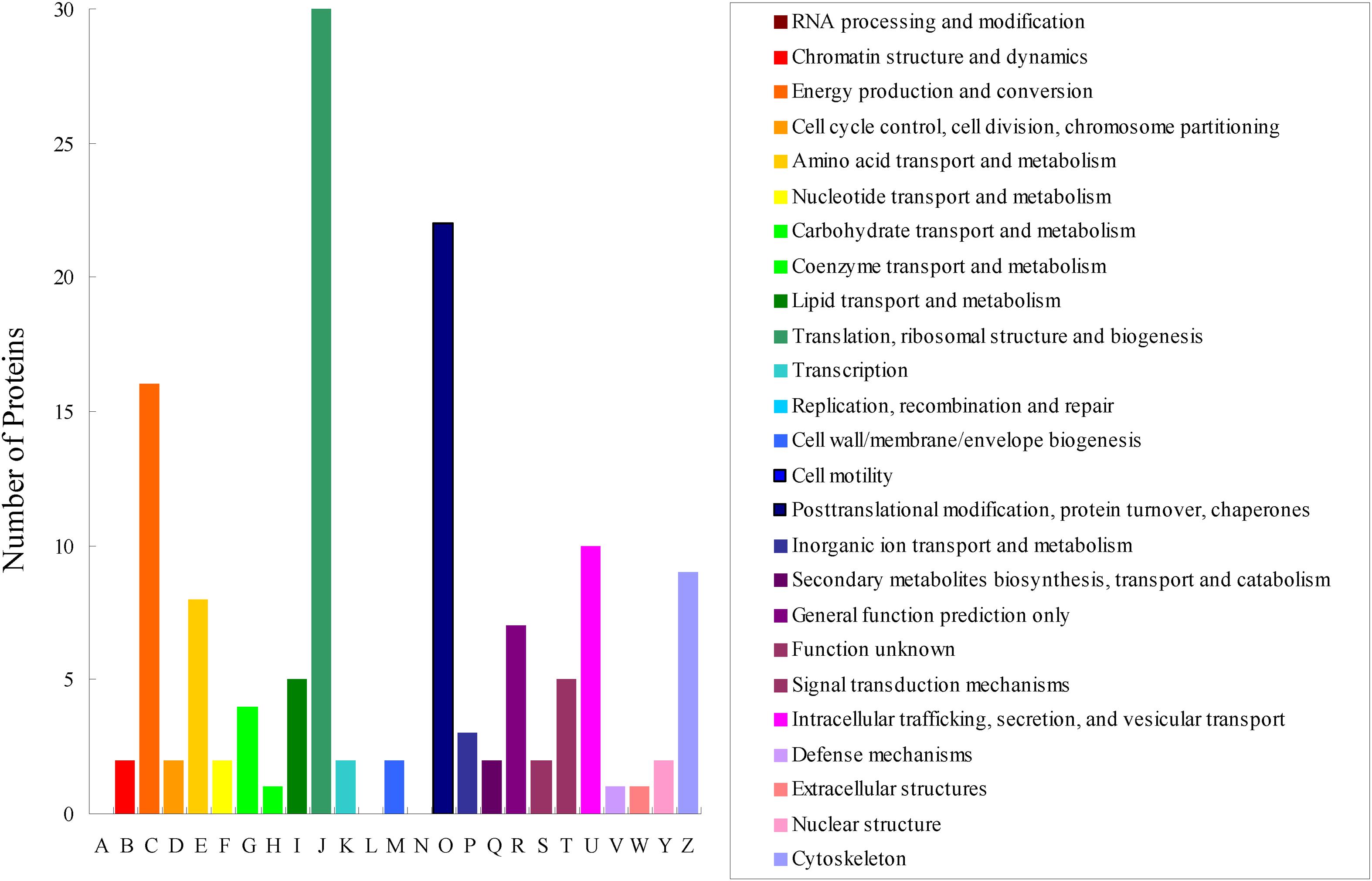

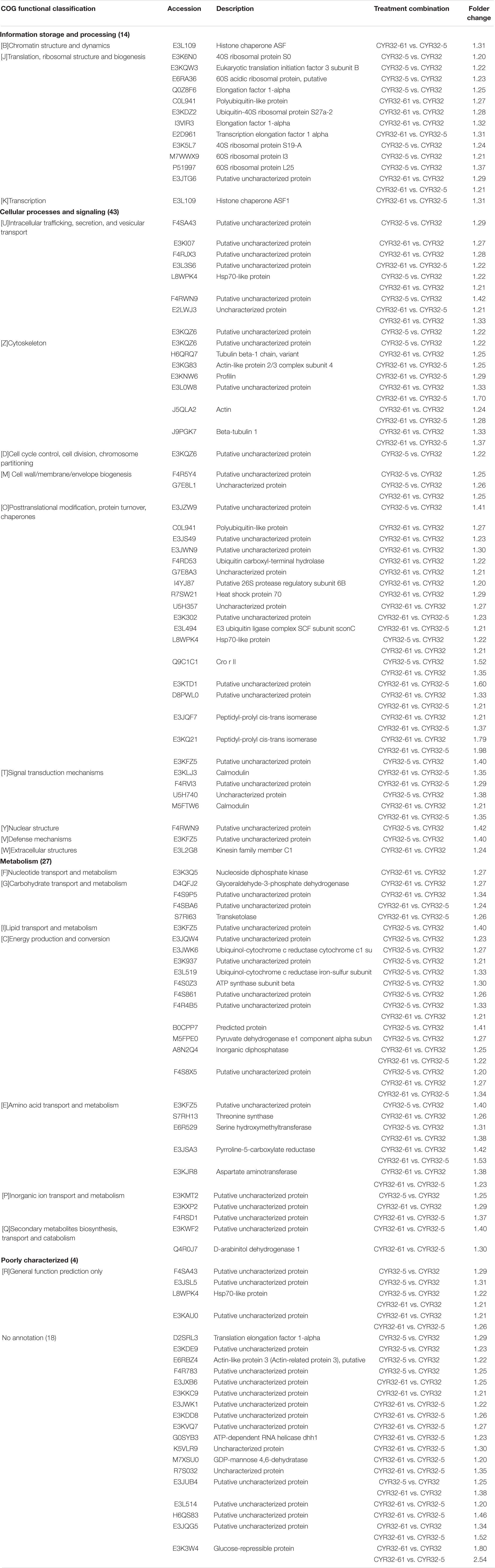

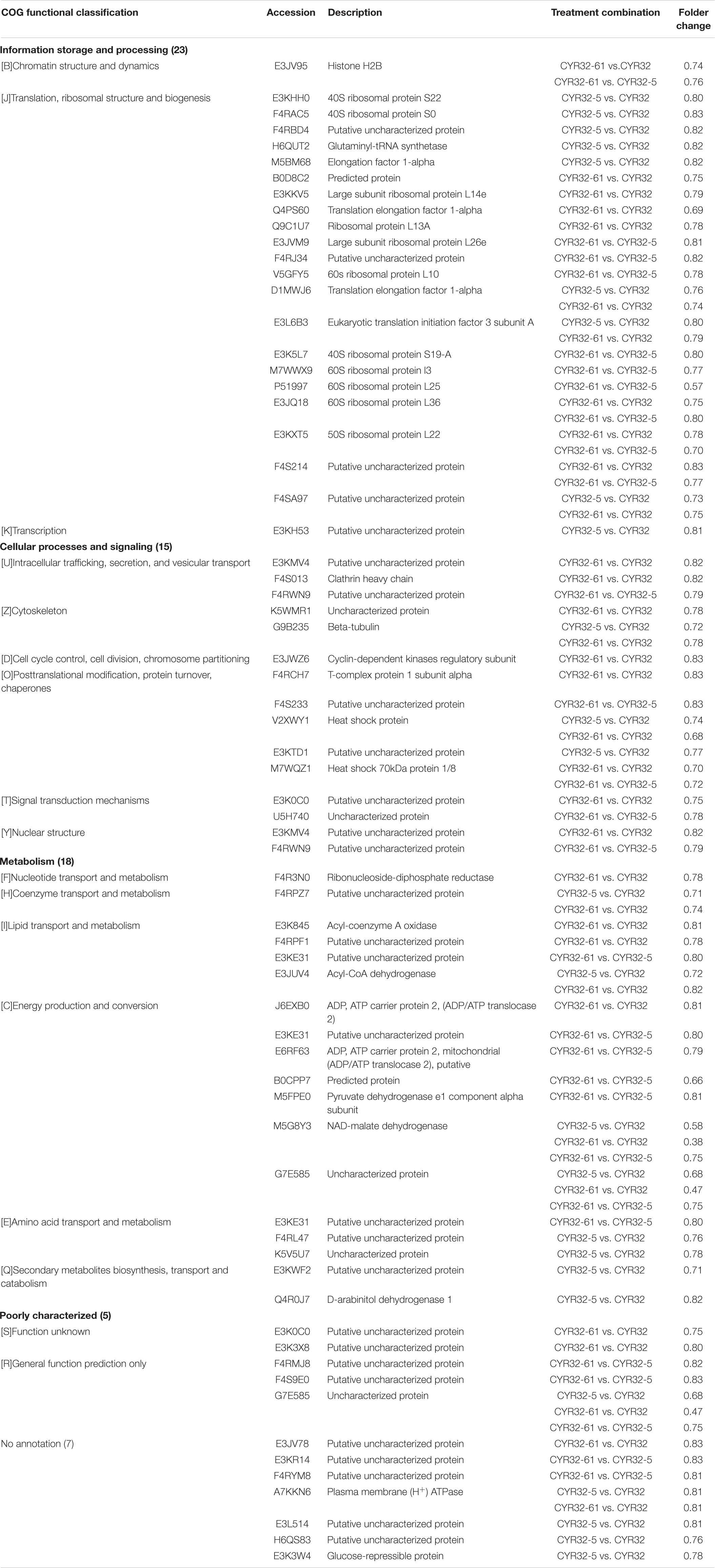

All obtained DEPs were subjected to COG functional annotation, and then assigned to 25 categories that were represented by A–Z (Figure 2). Among all the DEPs, seven were annotated with multiple functions, and 22 were not annotated and had no annotation information. The four main functional categories were as follows: [J] translation, ribosomal structure and biogenesis (31, 21.68%), [O] posttranslational modification, protein turnover, chaperones (24, 16.78%), [C] energy production and conversion (17, 11.89%), and [U] intracellular trafficking, secretion, and vesicular transport (11, 7.69%). The detailed functional annotations of the up-regulated DEPs and the down-regulated DEPs are shown in Tables 2, 3, respectively. The acquired DEPs were classified into four major functional categories, including “information storage and processing,” “cellular processes and signaling,” “metabolism,” and “poorly characterized.” Of the up-regulated DEPs, 14, 43, 27, and 4 were involved in “information storage and processing,” “cellular processes and signaling,” “metabolism,” and “poorly characterized,” respectively, and 18 had no annotation information. Of the down-regulated DEPs, 23, 15, 18, and 5 were involved in “information storage and processing,” “cellular processes and signaling,” “metabolism,” and “poorly characterized,” respectively, and 7 had no annotation information.

Figure 2. COG functional classification of the differentially expressed proteins acquired via iTRAQ technology in the combinations CYR32-5 vs. CYR32, CYR32-61 vs. CYR32, and CYR32-61 vs. CYR32-5.

Table 2. Functional annotations of the up-regulated differentially expressed proteins acquired in the combinations CYR32-5 vs. CYR32, CYR32-61 vs. CYR32, and CYR32-61 vs. CYR32-5.

Table 3. Functional annotations of the down-regulated differentially expressed proteins acquired in the combinations CYR32-5 vs. CYR32, CYR32-61 vs. CYR32, and CYR32-61 vs. CYR32-5.

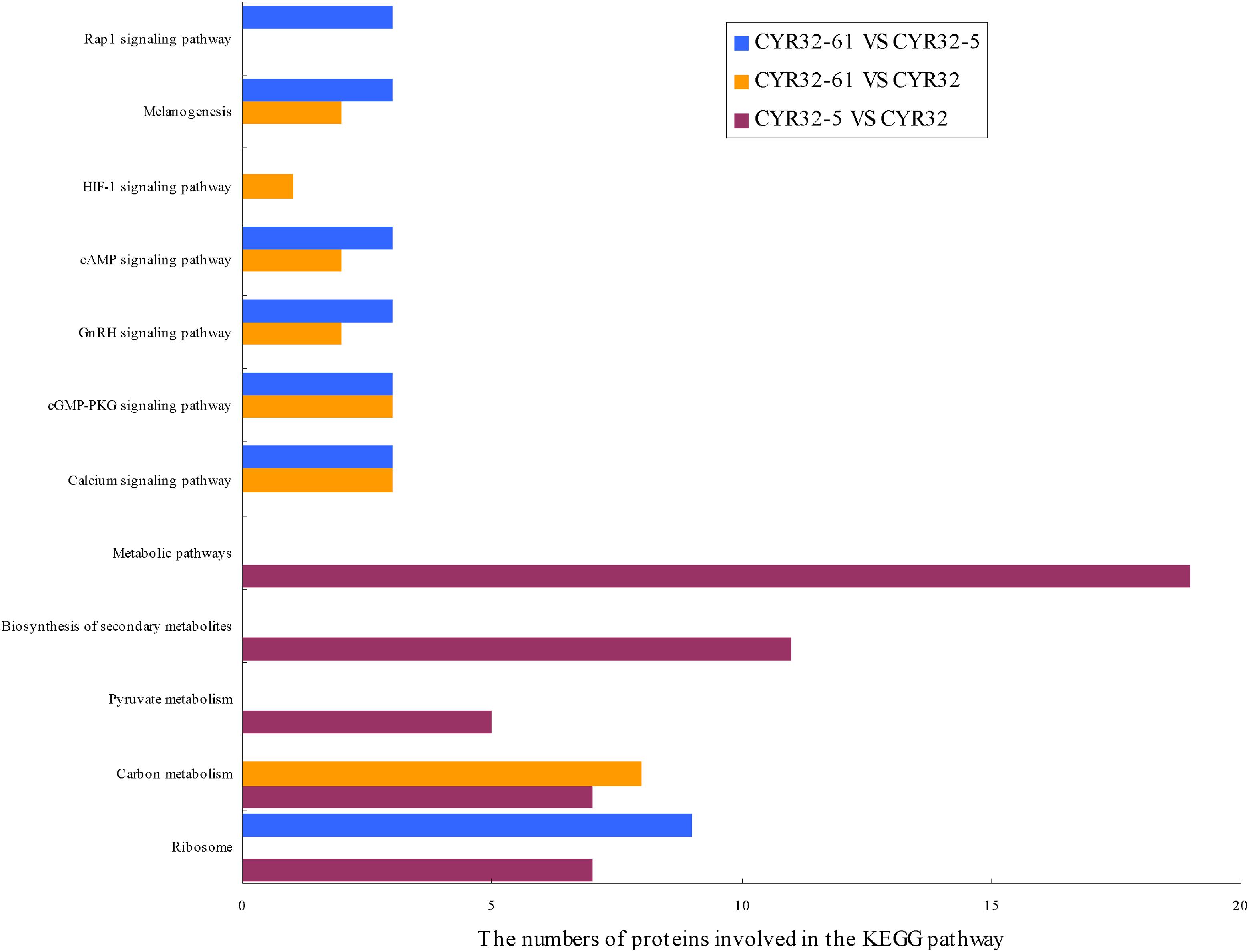

The biological pathways that the DEPs were involved in were investigated using the KEGG database, and 5, 7, and 7 significant enriched KEGG pathways (P < 0.05) were acquired for the DEPs of CYR32-5 vs. CYR32, CYR32-61 vs. CYR32, and CYR32-61 vs. CYR32-5, respectively (Figure 3 and Supplementary Table 3). The DEPs of CYR32-5 vs. CYR32 were involved in pathways including metabolic pathways, biosynthesis of secondary metabolites, carbon metabolism, ribosome, and pyruvate metabolism. The DEPs of CYR32-61 vs. CYR32 were mainly involved in the carbon metabolism pathway, calcium signaling pathway, and melanogenesis pathway. The DEPs of CYR32-61 vs. CYR32-5 were mainly involved in the ribosome pathway, melanogenesis pathway, and calcium signaling pathway.

Figure 3. KEGG pathway enrichment of the differentially expressed proteins acquired in the combinations CYR32-5 vs. CYR32, CYR32-61 vs. CYR32, and CYR32-61 vs. CYR32-5 (P < 0.05).

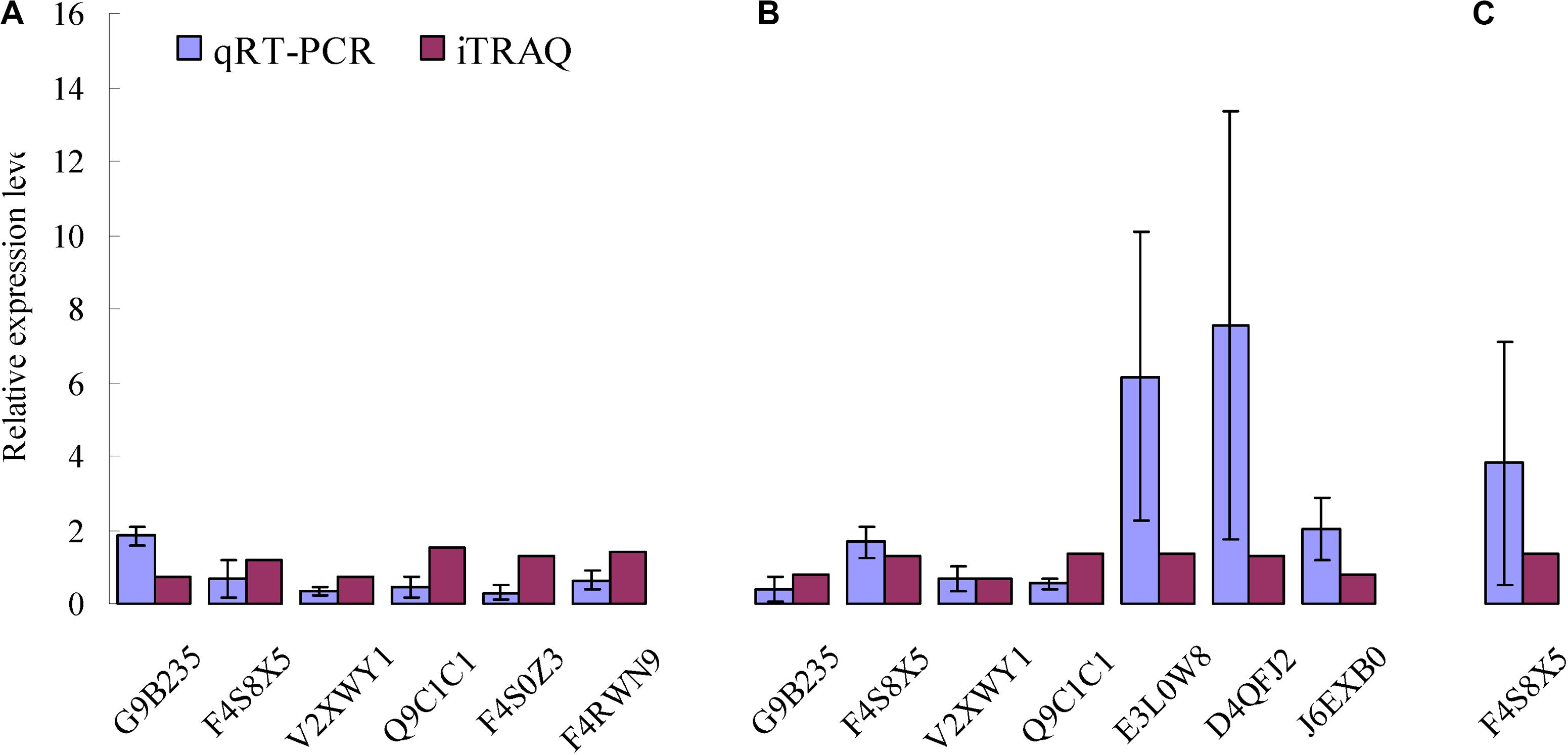

To confirm the differences in protein abundance in each of the three combinations including CYR32-5 vs. CYR32, CYR32-61 vs. CYR32, and CYR32-61 vs. CYR32-5, after germination of the urediospores, qRT-PCR was used to investigate the relative expression levels of the genes encoding the DEPs identified by iTRAQ analysis. The relative expression levels of the genes encoding six proteins (G9B235, F4S8X5, V2XWY1, Q9C1C1, F4S0Z3, and F4RWN9) in CYR32-5 vs. CYR32, seven proteins (G9B235, F4S8X5, V2XWY1, Q9C1C1, E3L0W8, D4QFJ2, and J6EXB0) in CYR32-61 vs. CYR32, and one protein (F4S8X5) in CYR32-61 vs. CYR32-5 were determined, and the results are shown in Figure 4. In CYR32-5 vs. CYR32, the relative expression levels of the genes encoding Q9C1C1, G9B235, F4S8X5, F4RWN9, and F4S0Z3 were not consistent with the corresponding protein abundance based on iTRAQ data, but the relative expression of the gene encoding V2XWY1 was consistent with the corresponding protein abundance. In CYR32-61 vs. CYR32, the relative expression levels of the genes encoding Q9C1C1 and J6EXB0 were inconsistent with the corresponding protein levels, and the genes encoding G9B235, F4S8X5, V2XWY1, E3L0W8, and D4QFJ2 were consistent with the corresponding protein levels. In CYR32-61 vs. CYR32-5, the relative expression level of the gene encoding F4S8X5 at the transcriptional level was consistent with the corresponding protein abundance obtained via iTRAQ analysis.

Figure 4. Comparison of encoding gene expression levels and protein levels of the selected enriched proteins identified by iTRAQ analysis in the combinations CYR32-5 vs. CYR32 (A), CYR32-61 vs. CYR32 (B), and CYR32-61 vs. CYR32-5 (C).

In this study, using the proteomics method based on iTRAQ technology, a total of 144 DEPs were obtained from the germinated urediospores with germ tubes in the CYR32-5 vs. CYR32, CYR32-61 vs. CYR32, and CYR32-61 vs. CYR32-5 conditions. Nine DEPs, including E3JQF7, E3JSA3, E3JUB4, E3K302, E3K3X8, E3KDD8, E3KXP2, Q9C1C1, and R7SW21, were predicted to contain signal peptides. Peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans isomerase (PPI, E3JQF7) is a high-efficiency foldase. In biological cells, after ribosome transcription, the peptide chain functions properly only through correct folding and positioning. PPI is associated with the correct folding of a protein (Lu et al., 2007). Heat shock protein 70 (R7SW21) can play an important role in the folding and stretching of newly synthesized polypeptides, can repair denatured proteins, and can prevent protein denaturation by up-regulating protein expression under adverse conditions (Tsan and Gao, 2004). In the present study, both E3JQF7 and R7SW21 were up-regulated in CYR32-61 vs. CYR32, and E3JQF7 was up-regulated in CYR32-61 vs. CYR32-5, indicating that strain CYR32-61 may be more resistant to stress than strains CYR32 and CYR32-5.

The histone chaperone ASF1 (anti-silencing function 1) is a molecular chaperone of histone H3-H4. It has been reported that ASF1 plays important roles in the processes of DNA replication and repair in yeast (Le et al., 1997) and Arabidopsis (Zhu et al., 2011). In this study, ASF1 (E3L109) was up-regulated in CYR32-61 vs. CYR32-5, indicating that strain CYR32-61 may be more resistant to stress than strain CYR32-5.

G proteins are involved in various cellular activities, including regulation of intracellular Ca2+ concentration, protein synthesis, and the binding of ribosomes to the endoplasmic reticulum (Lagerstedt et al., 2005). The DEPs G9B235, H6QRQ7, and J9PGK7 acquired in this study were involved in G protein regulation. G9B235 was down-regulated in CYR32-5 vs. CYR32, J9PGK7 was up-regulated in CYR32-61 vs. CYR32-5, and H6QRQ7 and J9PGK7 were up-regulated, and G9B235 was down-regulated in CYR32-61 vs. CYR32. Furthermore, the relative expression level of G9B235 determined by qRT-PCR was consistent with the corresponding protein abundance obtained by iTRAQ technology in CYR32-61 vs. CYR32, but the former was inconsistent with the latter in CYR32-5 vs. CYR32. Therefore, the results indicated that there was little correlation between the expression levels at the transcriptional level and the protein level for some DEPs, which was consistent with a previous report by Zhao et al. (2016).

As an important component of the second messenger system, calmodulin plays a key role in the regulation of the calcium signal system, and is associated with physiological metabolism regulation, gene expression, and normal growth and development of cells (Chin and Means, 2000). In both CYR32-61 vs. CYR32 and CYR32-61 vs. CYR32-5, putative uncharacterized protein (E3L0W8) with the role of calcium ion binding and calmodulin (M5FTW6) were up-regulated, and the relative expression level of E3L0W8 determined by qRT-PCR was consistent with the protein level obtained by iTRAQ technology. Calmodulin (E3KLJ3) was up-regulated in CYR32-61 vs. CYR32-5.

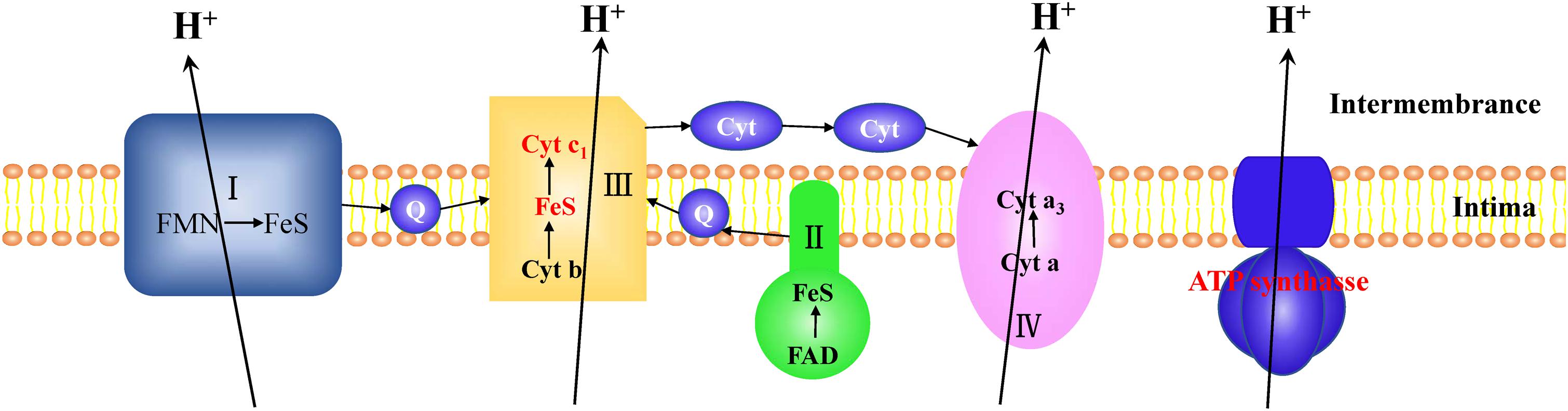

In CYR32-5 vs. CYR32, three DEPs involved in energy production, including ubiquinol-cytochrome c reductase cytochrome c1 subunit (E3JWK6), ubiquinol-cytochrome c reductase iron-sulfur subunit (E3L519), and ATP synthase subunit beta (F4S0Z3), were up-regulated. E3JWK6 and E3L519 are components of complex III of the electron transport chain, and are associated with electron transport. F4S0Z3 is the β subunit of the F1 part of ATP synthase, and contains a site to catalyze ATP synthesis. In living organisms, the electron transport chain and ATP synthesis are coupled together (Mitchell, 1961). A model for the coupling of electron transport and ATP synthesis in the combination CYR32-5 vs. CYR32 is shown in Figure 5. In this study, the acquired DEPs involved in the electron transport chain and in ATP synthesis were up-regulated, indicating that the processes of energy production during urediospore germination may be promoted in strain CYR32-5 compared to strain CYR32.

Figure 5. Model for the coupling of electron transport and ATP synthesis. The differentially expressed proteins (marked in red) in the electron transport chain complex III, including ubiquinol-cytochrome c reductase cytochrome c1 subunit (E3JWK6) and ubiquinol-cytochrome c reductase iron-sulfur subunit (E3L519), were up-regulated in CYR32-5 vs. CYR32. The β subunit (F4S0Z3) of ATP synthase marked in red was up-regulated in CYR32-5 vs. CYR32.

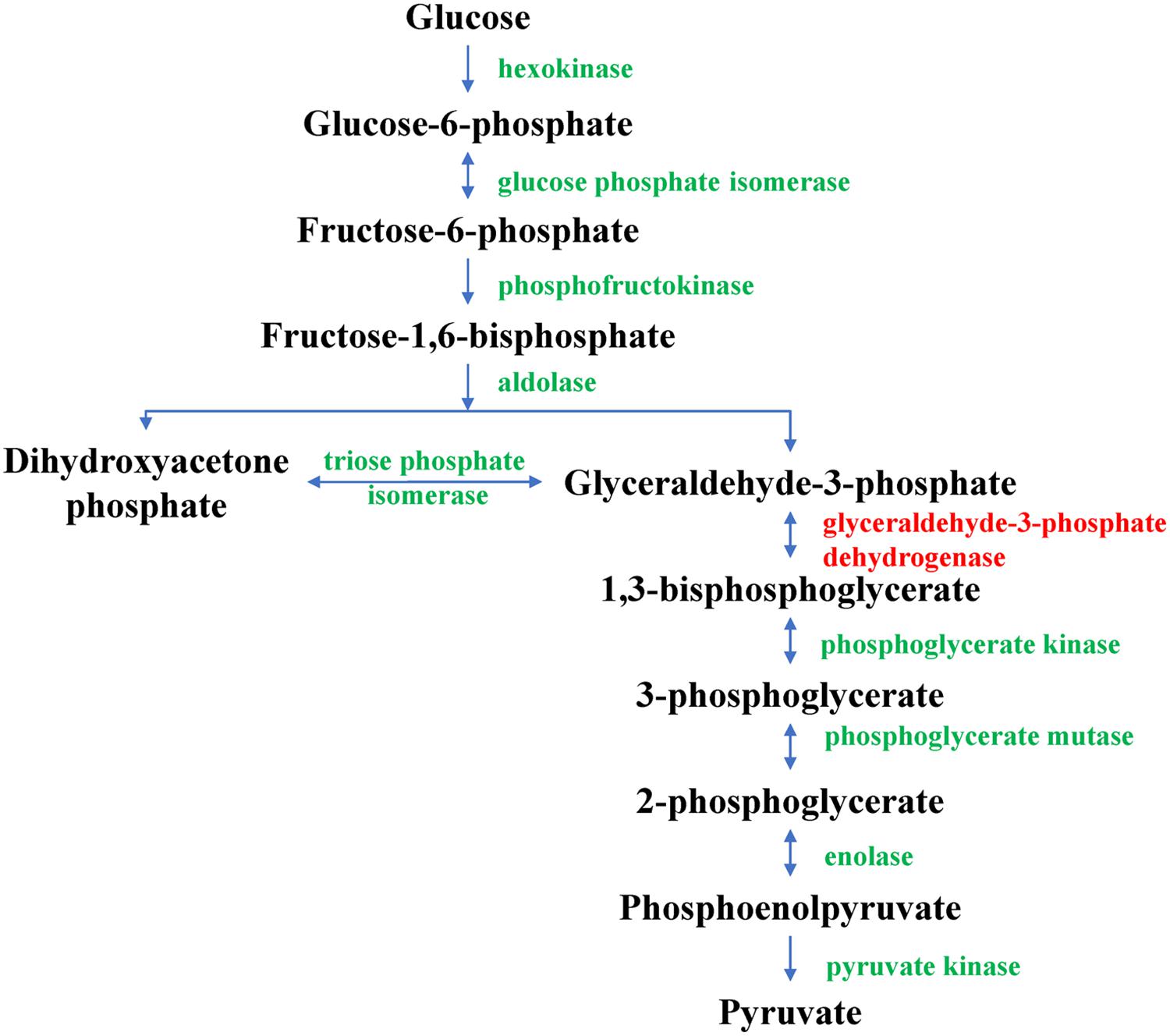

In the glycolysis pathway, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase can catalyze the formation of 1,3-diphosphoglycerate from 3-phosphoglyceraldehyde in the presence of NAD+ and phosphoric acid; it is, hence, an important enzyme in glycolysis. In this study, D4QFJ2, annotated as glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase, was up-regulated in CYR32-61 vs. CYR32 according to iTRAQ analysis, which was consistent with the relative expression level determined by qRT-PCR. The results indicated that, during urediospore germination, the glycolysis pathway (as shown in Figure 6) of virulence-mutant strain CYR32-61 may be promoted in comparison with that of strain CYR32. Glycolysis is the main process for the formation of ATP in carbohydrate metabolism. The results obtained in this study showed that the DEPs involved in the glycolysis pathway were up-regulated, further indicating that, during urediospore germination of the virulence-mutant strain CYR32-61 (as compared to the original strain CYR32), polysaccharide may be utilized to form ATP to promote the biological processes of urediospores. In addition, during glycolysis, the final product, pyruvate, can be irreversibly catalyzed by pyruvate dehydrogenase multi-enzyme complex (PDHc) to form acetyl-coenzyme A, which can be oxidatively decomposed in the tricarboxylic acid cycle. Pyruvate dehydrogenase E1 is a component of PDHc, and if its activity is inhibited, aerobic metabolism can be blocked, thus affecting the normal metabolism of living organisms (Danson et al., 1978). In CYR32-5 vs. CYR32, the expression of M5FPE0—annotated as pyruvate dehydrogenase E1 component alpha subunit—was up-regulated, indicating that the formation of ATP during oxidative phosphorylation in the germinated urediospores and germ tubes may be promoted in strain CYR32-5 in comparison with strain CYR32.

Figure 6. Glycolysis pathway. The glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase marked in red was found to be up-regulated in CYR32-61 vs. CYR32.

Inorganic diphosphatase (A8N2Q4) mainly involved in DNA synthesis, can catalyze the conversion of one molecule of pyrophosphate into two molecules of phosphate, accompanied by the generation of high levels of energy (Kukko and Saarento, 1984). A8N2Q4 was up-regulated in CYR32-61 vs. CYR32 and CYR32-61 vs. CYR32-5 in this study. The results indicated that in comparison with strains CYR32 and CYR32-5, the energy metabolism pathway during urediospore germination may be promoted in strain CYR32-61, which may contribute to the progress in biological processes of urediospores.

It has been reported that UV-B radiation can induce virulence variation in Pst (Shang et al., 1994; Huang et al., 2005; Wang et al., 2009; Zhao et al., 2019). Similarly, in studies on two other important pathogens—Puccinia triticina (Neugebauer et al., 2018) and P. graminis f. sp. tritici (Zhang et al., 2017), causing wheat leaf rust and wheat stem rust, respectively, it has also been reported that mutation may be the main mechanism of virulence variation of the two pathogens, thus resulting in the loss of wheat resistance and severe losses of wheat yield. In this study, after the germination of urediospores, the expression levels of many proteins in UV-B-induced virulence-mutant strains, CYR32-5 and CYR32-61, were different from those in CYR32, the original strain. The changes in the related biological processes in which the DEPs are involved may result in changes in virulence phenotypes of Pst and may be responsible for virulence variation. To further explore the virulence variation mechanisms of Pst, it is of great importance to conduct studies by pathogen sequencing at the genome level and to investigate the metabolomics of Pst after mutations.

In this study, using the proteomics method based on iTRAQ technology, a quantitative proteomic analysis of the germinated urediospores (with germ tubes) of the original strain, CYR32, and two UV-B-induced virulence-mutant strains, CYR32-5 and CYR32-61, was undertaken. A total of 2,271 proteins were identified in eight samples of the three Pst strains, and 59, 74, and 64 DEPs were obtained in each of the three combinations, i.e., CYR32-5 vs. CYR32, CYR32-61 vs. CYR32, and CYR32-61 vs. CYR32-5, respectively. The identified DEPs were mainly involved in energy metabolism, carbon metabolism and cellular substance synthesis. The relative expression levels of the genes encoding some DEPs, quantified using qRT-PCR, were consistent with the corresponding protein abundance obtained via iTRAQ analysis. Compared with the original strain, CYR32, the DEPs involved in stress-related and energy metabolism were up-regulated in the virulence-mutant strains, indicating that the virulence-mutant strains, CYR32-5 and CYR32-61, were more tolerant to stress than the original strain. These results are of great significance for further studies on the mechanisms of Pst virulence variation and for implementing control measures for wheat stripe rust.

The datasets generated for this study can be found in the ProteomeXchange Consortium (http://proteomecentral.proteomexchange.org) via the iProX partner repository with the dataset identifier PXD018136.

HW contributed conception of the study. HW and YaZ designed the experiments. YaZ, PC, and YuZ performed the experiments. YaZ and HW analyzed the data and wrote the draft of the manuscript. All authors contributed to manuscript revision, read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

This study was supported by the National Key Basic Research Program of China (Grant No. 2013CB127700) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 31101393).

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmicb.2020.542961/full#supplementary-material

Armenteros, J. J. A., Tsirigos, K. D., Sønderby, C. K., Petersen, T. N., Winther, O., Brunak, S., et al. (2019). SignalP 5.0 improves signal peptide predictions using deep neural networks. Nat. Biotechnol. 37, 420–423. doi: 10.1038/s41587-019-0036-z

Braga, G. U. L., Rangel, D. E. N., Fernandes, ÉK. K., Flint, S. D., and Roberts, D. W. (2015). Molecular and physiological effects of environmental UV radiation on fungal conidia. Curr. Genet. 61, 405–425. doi: 10.1007/s00294-015-0483-0

Chen, W. Q., Wellings, C., Chen, X. M., Kang, Z. S., and Liu, T. G. (2014). Wheat stripe (yellow) rust caused by Puccinia striiformis f. sp. tritici. Mol. Plant Pathol. 15, 433–446. doi: 10.1111/mpp.12116

Chen, X. M. (2005). Epidemiology and control of stripe rust [Puccinia striiformis f. sp. tritici] on wheat. Can. J. Plant Pathol. 27, 314–337. doi: 10.1080/07060660509507230

Chen, X. M. (2007). Challenges and solutions for stripe rust control in the United States. Aust. J. Agric. Res. 58, 648–655. doi: 10.1071/AR07045

Cheng, P., Ma, Z. H., Wang, X. J., Wang, C. Q., Li, Y., Wang, S. H., et al. (2014). Impact of UV-B radiation on aspects of germination and epidemiological components of three major physiological races of Puccinia striiformis f. sp. tritici. Crop Prot. 65, 6–14. doi: 10.1016/j.cropro.2014.07.002

Chin, D., and Means, A. R. (2000). Calmodulin: a prototypical calcium sensor. Trends Cell Biol. 10, 322–328. doi: 10.1016/S0962-8924(00)01800-6

Conesa, A., Götz, S., García-Gómez, J. M., Terol, J., Talón, M., and Robles, M. (2005). Blast2GO: a universal tool for annotation, visualization and analysis in functional genomics research. Bioinformatics 21, 3674–3676. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti610

Danson, M. J., Fersht, A. R., and Perham, R. N. (1978). Rapid intramolecular coupling of active sites in the pyruvate dehydrogenase complex of Escherichia coli: mechanism for rate enhancement in a multimeric structure. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 75, 5386–5390. doi: 10.1073/pnas.75.11.5386

Fargues, J., Goettel, M. S., Smits, N., Ouedraogo, A., Vidal, C., Lacey, L. A., et al. (1996). Variability in susceptibility to simulated sunlight of conidia among isolates of entomopathogenic Hyphomycetes. Mycopathologia 135, 171–181. doi: 10.1007/BF00632339

Fernandes, ÉK. K., Rangel, D. E. N., Moraes, ÁM. L., Bittencourt, V. R. E. P., and Roberts, D. W. (2007). Variability in tolerance to UV-B radiation among Beauveria spp. isolates. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 96, 237–243. doi: 10.1016/j.jip.2007.05.007

Fu, Y., Zhang, H., Mandal, S. N., Wang, C. Y., Chen, C. H., and Ji, W. Q. (2016). Quantitative proteomics reveals the central changes of wheat in response to powdery mildew. J. Proteomics 130, 108–119. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2015.09.006

Gao, L. M., Wang, X. F., Li, Y. F., and Han, R. (2019). Chloroplast proteomic analysis of Triticum aestivum L. seedlings responses to low levels of UV-B stress reveals novel molecular mechanism associated with UV-B tolerance. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 26, 7143–7155. doi: 10.1007/s11356-019-04168-4

Hu, X. P., Wang, B. T., and Kang, Z. S. (2014). Research progress on virulence variation of Puccinia striiformis f. sp. tritici in China. J. Tri. Crops 34, 709–716. doi: 10.7606/j.issn.1009-1041.2014.05.22

Huang, L. L., Wang, X. L., Kang, Z. S., and Zhao, J. (2005). Mutation of pathogenicity induced by ultraviolet radiation in Puccinia striiformis f. sp. tritici and RAPD analysis of mutants. Mycosystema 24, 400–406. doi: 10.13346/j.mycosystema.2005.03.015

Huang, X. L., Feng, H., and Kang, Z. S. (2012). Selection of reference genes for quantitative real-time PCR normalization in Puccina striiformis f. sp. tritici. J. Agric. Biotechnol. 20, 181–187. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1674-7968.2012.02.010

Jansen, M. A. K., Gaba, V., and Greenberg, B. M. (1998). Higher plants and UV-B radiation: balancing damage, repair and acclimation. Trends Plant Sci. 3, 131–135. doi: 10.1016/S1360-1385(98)01215-1

Jin, Y., Szabo, L. J., and Carson, M. (2010). Century-old mystery of Puccinia striiformis life history solved with the identification of Berberis as an alternate host. Phytopathology 100, 432–435. doi: 10.1094/phyto-100-5-0432

Jing, J. X., Shang, H. S., and Li, Z. Q. (1993). The biological effects of ultraviolet ray radiation on wheat stripe rust (Puccinia striiformis West.). Acta Phytopathol. Sin. 23, 299–304. doi: 10.13926/j.cnki.apps.1993.04.004

Kang, Z. S., Wang, X. J., Zhao, J., Tang, C. L., and Huang, L. L. (2015). Advances in research of pathogenicity and virulence variation of the wheat stripe rust fungus Puccinia striiformis f. sp. tritici. Sci. Agr. Sin. 48, 3439–3453. doi: 10.3864/j.issn.0578-1752.2015.17.011

Kukko, E., and Saarento, H. (1984). Diphosphate concentration does not correlate with the level of inorganic diphosphatase in Escherichia coli. Folia Microbiol. 29, 282–287. doi: 10.1007/BF02875958

Kumar, V., Lockerbie, O., Keil, S. D., Ruane, P. H., Platz, M. S., Martin, C. B., et al. (2004). Riboflavin and UV-light based pathogen reduction: extent and consequence of DNA damage at the molecular level. Photochem. Photobiol. 80, 15–21. doi: 10.1562/2003-12-23-RA-036.1

Lagerstedt, J. O., Reeve, I., Voss, J. C., and Persson, B. L. (2005). Structure and function of the GTP binding protein Gtr1 and its role in phosphate transport in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Biochemistry 44, 511–517. doi: 10.1021/bi048659v

Le, S. Y., Davis, C., Konopka, J. B., and Sternglanz, R. (1997). Two new S-phase-specific genes from Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast 13, 1029–1042. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0061(19970915)13:11<1029::AID-YEA160<3.0.CO;2-1

Line, R. F. (2002). Stripe rust of wheat and barley in North America: a retrospective historical review. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 40, 75–118. doi: 10.1146/annurev.phyto.40.020102.111645

Livak, K. J., and Schmittgen, T. D. (2001). Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔGT method. Methods 25, 402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262

Lu, K. P., Finn, G., Lee, T. H., and Nicholson, L. K. (2007). Prolyl cis-trans isomerization as a molecular timer. Nat. Chem. Biol. 3, 619–629. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.2007.35

Ma, J., Chen, T., Wu, S. F., Yang, C. Y., Bai, M. Z., Shu, K. X., et al. (2019). iProX: an integrated proteome resource. Nucleic Acids Res. 47, D1211–D1217. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky869

Ma, Q., Kang, Z. S., and Li, Z. Q. (1993). The fusion of urediospore germ tubes in Puccinia striiformis West. on wheat leaves. Acta Univ. Agric. Boreali Occidentalis 21, 97–98.

Mitchell, P. (1961). Coupling of phosphorylation to electron and hydrogen transfer by a chemi-osmotic type of mechanism. Nature 191, 144–148. doi: 10.1038/191144a0

Neugebauer, K. A., Bruce, M., Todd, T., Trick, H. N., and Fellers, J. P. (2018). Wheat differential gene expression induced by different races of Puccinia triticina. PLoS One 13:e0198350. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0198350

OuYang, Q. L., Tao, N. G., and Zhang, M. L. (2018). A damaged oxidative phosphorylation mechanism is involved in the antifungal activity of citral against Penicillium digitatum. Front. Microbiol. 9:239. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.00239

Shang, H. S., Jing, J. X., and Li, Z. Q. (1994). Mutations induced by ultraviolet radiation affecting virulence in Puccinia striiformis. Acta Phytopathol. Sin. 24, 347–351. doi: 10.13926/j.cnki.apps.1994.04.019

Trentin, A. R., Pivato, M., Mehdi, S. M. M., Barnabas, L. E., Giaretta, S., Fabrega-Prats, M., et al. (2015). Proteome readjustments in the apoplastic space of Arabidopsis thaliana ggt1 mutant leaves exposed to UV-B radiation. Front. Plant Sci. 6:128. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2015.00128

Tsan, M. F., and Gao, B. C. (2004). Cytokine function of heat shock proteins. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 286, C739–C744. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00364.2003

Wan, A. M., Chen, X. M., and He, Z. H. (2007). Wheat stripe rust in china. Aust. J. Agric. Res. 58, 605–619. doi: 10.1071/AR06142

Wan, A. M., Zhao, Z. H., Chen, X. M., He, Z. H., Jin, S. L., Jia, Q. Z., et al. (2004). Wheat stripe rust epidemic and virulence of Puccinia striiformis f. sp. tritici in China in 2002. Plant Dis. 88, 896–904. doi: 10.1094/PDIS.2004.88.8.896

Wang, X. J., Ma, Z. H., Jiang, Y. Y., Shi, S. D., Liu, W. C., Zeng, J., et al. (2014). Modeling of the overwintering distribution of Puccinia striiformis f. sp. tritici based on meteorological data from 2001 to 2012 in China. Front. Agr. Sci. Eng. 1:223–235. doi: 10.15302/J-FASE-2014025

Wang, X. L., Zhu, F., Huang, L. L., Wei, G. R., and Kang, Z. S. (2009). Effects of ultraviolet radiation on pathogenicity mutation of Puccinia striiformis f. sp. tritici. J. Nucl. Agric. Sci. 23, 375–379. doi: 10.11869/hnxb.2009.03.0375

Wargent, J. J., and Jordan, B. R. (2013). From ozone depletion to agriculture: understanding the role of UV radiation in sustainable crop production. New Phytol. 197, 1058–1076. doi: 10.1111/nph.12132

Wu, S. T., Zhu, Z. W., Fu, L. M., Niu, B. F., and Li, W. Z. (2011). WebMGA: a customizable web server for fast metagenomic sequence analysis. BMC Genomics 12:444. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-12-444

Wu, X. C., Fang, C. X., Chen, J. Y., Wang, Q. S., Chen, T., Lin, W. X., et al. (2011). A proteomic analysis of leaf responses to enhanced ultraviolet-B radiation in two rice (Oryza sativa L.) cultivars differing in UV sensitivity. J. Plant Biol. 54, 251–261. doi: 10.1007/s12374-011-9162-y

Xie, C., Mao, X. Z., Huang, J. J., Ding, Y., Wu, J. M., Dong, S., et al. (2011). KOBAS 2.0: a web server for annotation and identification of enriched pathways and diseases. Nucleic Acids Res. 39, (Suppl. 2), W316–W322. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr483

Xu, J. Y., Shao, X. F., Wei, Y. Y., Xu, F., and Wang, H. F. (2017). iTRAQ proteomic analysis reveals that metabolic pathways involving energy metabolism are affected by tea tree oil in Botrytis cinerea. Front. Microbiol. 8:1989. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.01989

Zhang, J. P., Zhang, P., Karaoglu, H., and Park, R. F. (2017). Molecular characterization of Australian isolates of Puccinia graminis f. sp. tritici supports long-term clonality but also reveals cryptic genetic variation. Phytopathology 107, 1032–1038. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO-09-16-0334-R

Zhao, J., Zhuang, H., Zhan, G. M., Huang, L. L., and Kang, Z. S. (2016). Proteomic analysis of Puccina striiformis f. sp. tritici (Pst) during uredospore germination. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 144, 121–132. doi: 10.1007/s10658-015-0756-y

Zhao, Y. Q., Cheng, P., Li, T. T., Ma, J. X., Zhang, Y. Z., and Wang, H. G. (2019). Investigation of urediospore morphology, histopathology and epidemiological components on wheat plants infected with UV-B-induced mutant strains of Puccinia striiformis f. sp. tritici. MicrobiologyOpen 8:e870. doi: 10.1002/mbo3.870

Zhao, Y. Q., Cheng, P., Li, T. T., and Wang, H. G. (2018). Proteomic changes in urediospores of Puccinia striiformis f. sp. tritici after UV-B radiation. Int. J. Agric. Biol. 20, 1961–1969. doi: 10.17957/IJAB/15.0715

Zheng, W. M., Huang, L. L., Huang, J. Q., Wang, X. J., Chen, X. M., Zhao, J., et al. (2013). High genome heterozygosity and endemic genetic recombination in the wheat stripe rust fungus. Nat. Commun. 4:2673. doi: 10.1038/ncomms3673

Keywords: Puccinia striiformis f. sp. tritici, virulence variation, proteomics, iTRAQ, UV-B radiation, wheat stripe rust

Citation: Zhao Y, Cheng P, Zhang Y and Wang H (2020) Proteomic Analysis of UV-B-Induced Virulence-Mutant Strains of Puccinia striiformis f. sp. tritici Based on iTRAQ Technology. Front. Microbiol. 11:542961. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2020.542961

Received: 15 March 2020; Accepted: 14 September 2020;

Published: 02 October 2020.

Edited by:

Hiran A. Ariyawansa, National Taiwan University, TaiwanReviewed by:

Qingping Zhong, South China Agricultural University, ChinaCopyright © 2020 Zhao, Cheng, Zhang and Wang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Haiguang Wang, d2FuZ2hhaWd1YW5nQGNhdS5lZHUuY24=

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.