94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Microbiol. , 31 July 2020

Sec. Microbial Immunology

Volume 11 - 2020 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2020.01716

Ashish Kumar1

Ashish Kumar1 Saravanan Vijaykumar2

Saravanan Vijaykumar2 Manas Ranjan Dikhit3

Manas Ranjan Dikhit3 Kumar Abhishek3

Kumar Abhishek3 Rimi Mukherjee3

Rimi Mukherjee3 Abhik Sen3

Abhik Sen3 Pradeep Das3

Pradeep Das3 Sushmita Das4*

Sushmita Das4*MicroRNAs are small ribonucleic acid that act as an important regulator of gene expression at the molecular level. However, there is no comparative data on the regulation of microRNAs (miRNAs) in visceral leishmaniasis (VL) and post-kala-azar dermal leishmaniasis (PKDL). In this current study, we compared the expression miRNA profile in host cells (GTHP), with VL strain (GVL) and PKDL strain-infected host cell (GPKDL). Normalized read count comparison between different conditions revealed that the miRNAs are indeed differentially expressed. In GPKDL with respect to GVL and GTHP, a total of 798 and 879 miRNAs were identified, out of which 349 and 518 are known miRNAs, respectively. Comparative analysis of changes in miRNA expression suggested that the involvement of differentially expressed miRNAs in various biological processes like PI3K pathway activation, cell cycle regulation, immunomodulation, apoptosis inhibition, different cytokine production, T-cell phenotypic transitions calcium regulation, and so on. A pathway enrichment study using in silico predicted gene targets of differentially expressed miRNAs showed evidence of potentially universal immune signaling pathway effects. Whereas cytokine–cytokine receptor interaction, phagocytosis, and transforming growth factor beta (TGF-β) signaling pathways were more highly enriched using targets of miRNAs upregulated in GPKDL. These findings could contribute to a better understanding of PKDL pathogenesis. Furthermore, the identified miRNAs could also be used as biomarkers in diagnosis, prognosis, and therapeutics of PKDL infection control.

Visceral leishmaniasis (VL) is a vector-borne disease caused by an intracellular parasite, Leishmania donovani. The highest burden of VL is reported from the states of Bihar, Jharkhand, West Bengal, and Uttar Pradesh of India. Among these, 90% of VL cases in India originate from Bihar (Singh et al., 2010). Post-kala-azar dermal leishmaniasis (PKDL), an enigmatic dermal sequel of VL, may appear after treatment of (VL, kala-azar) (Zijlstra et al., 2000). PKDL has several clinical polymorphic forms from a simple hypopigmented macular form of more developed lesions like papular, nodular, and mixed lesions. PKDL patients may play a role in the transmission of VL (Zijlstra et al., 2003; World Health Organization [WHO], 2010), which is a much-debated aspect. However, several cases have also been reported without a documented history of VL in 10–23% of patients (Zijlstra et al., 2017). Hence, it calls for better management of PKDL, especially susceptibility.

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are small palindromic sequences, which are transcribed by RNA polymerase II or polymerase III to mature miRNA by Drosha and Dicer enzymes. The mature miRNA then binds to targeted RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC) and participates in the degradation of transcriptional silencing of messenger RNAs (Krol et al., 2010; Czech and Hannon, 2011). During the past years, an increasing amount of evidence indicates that miRNAs play an important role in many biological processes, like organ development, cell differentiation, proliferation, apoptosis, signal transduction, innate immunity, metabolism, disease pathogenesis, and tumorigenesis (Tiscornia and Belmonte, 2010; Huang et al., 2011; Zhang et al., 2014; Kumar and Lupold, 2016). Thus, an increased interest has developed for the subject.

“Next-generation sequencing” (NGS) is a high throughput technology allowing the generation and detection of thousands to millions of short sequencing reads in a single machine run, which can be rapidly introduced into clinical and public health laboratory practice (Besser et al., 2018). The profiling of miRNAs by NGS has progressed rapidly and is a promising field for applications in drug development (Liu et al., 2011). NGS is used to screen differential expression levels of microRNA between different disease conditions (Su et al., 2018).

In the field of Leishmania, Geraci et al. (2015) have reported that host cells after infection differentially expressed several miRNAs that may regulate different functions. Similarly, Tiwari et al. (2017) have identified 940 miRNAs in L. donovani-infected macrophages by de novo sequencing out of which levels of 85 miRNAs were found to be consistently modified by parasite infection. Singh et al. (2016) have demonstrated the novel regulatory role of host microRNA, MIR30A-3p in the modulation of host cell autophagy after infection with L. donovani. It was also reported that miRNAs can regulate immune signaling, cytokine production, and immune cell migration to control the VL infection in humans (Pandey et al., 2016).

Post-kala-azar dermal leishmaniasis, a cutaneous form of VL, commonly develops after apparent cure from VL. PKDL cases are treated according to national guidelines with miltefosine for 12 weeks; this regimen (50 mg twice per day) has a cure rate of 78%, but a higher dose showed a high cure rate but increased side effects (Mukhopadhyay et al., 2014). In this study, we are showing the differentially expressed miRNA in host cells infected with a PKDL strain (GPKDL) and that miRNAs may regulate different immunological pathways. The result of the current study may help in targeting the specific pathway, which may involve in PKDL disease progression. Targeting these pathways may help in future rational chemotherapeutic drug designing to counter drug resistance and the spread of PKDL.

Leishmania donovani isolates from a VL patient (MHOM/IN/83/AG83; repository number: RMRI/PB-0078) and from a PKDL patient (repository number: RMRI/PB-0088) were used in this study. Briefly, the collected splenic aspirates of VL were incubated in Roswell Park Memorial Institute (RPMI)-1640 medium (Gibco) (pH 7.4) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Gibco) and 1% of penicillin (50 U/ml)–streptomycin (50 mg/ml) solution (Sigma) at 25°C. The amastigotes from splenic aspirates were transformed into promastigotes, and they were maintained further in RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with FBS. To obtain PKDL isolates, the nodular form of tissue was taken from the PKDL patients in RPMI-1640 media (Gibco, United States) with 20% FBS (Gibco, United States). Tissue cells containing amastigotes were converted into promastigotes form in RPMI-1640 media after 1–2 weeks. Promastigotes were subcultured in RPMI-1640 and maintained in tissue culture flask (Nunc) for infection study. Similarly, the human acute monocytic leukemia-derived THP-1 cell line procured from NCCS Pune was maintained in RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with 10% FBS at 37°C in a humidified mixture of 5% CO2 atmosphere for further studies.

The VL and PKDL isolates were used for infection. Briefly, 104 THP-1 cells/well were cultured in eight-well Lab-Tek chambers (Nunc, Roskilde, Denmark). To differentiate monocyte into a macrophage, cells were treated with phorbol myristate acetate (PMA, Sigma-Aldrich) at 40 ng/ml for 24 h (37°C, 5% CO2). After 24 h, cells were gently washed with warm medium, replenished with fresh medium, and incubated for an additional 24 h. Parasites [at a multiplicity of infection (MOI), ∼10:1] of both VL and PKDL isolates of L. donovani were added into the THP-1-derived macrophage cultures and maintained at 37°C in 5% CO2 overnight. After 12 h, non-internalized promastigotes were eliminated. Infected cells were collected by washing with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; pH 7.2).

RNA isolation from samples THP-1 (GTHP), THP-1 infected with VL parasites (GVL), and THP-1 infected with PKDL parasites (GPKDL) was performed using Ambion mirVANA miRNA isolation kit (Cat-AM1560, as per manufacturer’s instructions). Briefly, cells were lysed with 300 μl of lysis/binding buffer. Homogenate additive was added to the lysate at 1/10th of the lysate volume followed by the addition of acid phenol–chloroform. After brief vortex and centrifugation, the upper aqueous phase was aspirated into a new vial. This aqueous phase was mixed with 1.25 volumes of 100% ethanol and loaded onto a filter cartridge. The remaining steps of the purification were followed as per the manufacturer’s guidelines, including on-column DNase treatment Qiagen (Cat-79254). RNA was eluted in 25 μl of nuclease-free water (Ambion, Cat-AM9938). Eluted RNA was stored at −80°C until further use. The concentration and purity of the RNA extracted were evaluated using the Nanodrop spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific; 2000). The integrity of the extracted RNA was analyzed with the 2100 expert Bioanalyzer (Agilent). We considered RNA to be of good quality based on the 260/280 values (Nanodrop) and optimal RNA integrity profile in the Bioanalyzer.

Small RNA sequencing libraries were prepared using NEXTFLEX Small RNA-Seq Kit v3 (Bio Scientific Corp., TX, United States) using the manufacturer’s protocol. Briefly, 500 ng of total RNA was used as starting material. 3′ adapters were ligated to the specific 3′OH group of microRNAs followed by ligation of 5′ adapter. Adapter-ligated fragments were reverse transcribed with Moloney murine leukemia virus (M-MuLV) reverse transcriptase by priming with reverse transcription primers. Complementary DNA (cDNA) thus formed was enriched and indexed by PCR (15 cycles). Libraries were size selected using the NEXTflex magnetic bead purification system and finally reconstituted in nuclease-free water. The sequencing libraries were quantified by the Qubit fluorometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, United States), and its fragment size distribution was analyzed on Tape Station using Agilent D1000 Screen Tapes (Agilent Technologies, United States). The libraries were sequenced on Illumina NextSeq 500 sequencer (Illumina, Inc., United States) for 75-bp single read chemistry following manufacture’s guidelines.

In this study, two infected human cell lines (GVL and GPKDL) and one uninfected cell line (GTHP) were sequenced in NGS single-end read chemistry and carried out analysis against Homo sapiens GRCh38 genome data. The raw data of 75 bp length was generated on the Illumina platform and received in FASTQ format. srna-workbenchV3.0_ALPHA was used to trim the adapter and performed length filtering (minimum length of 16 bp and maximum of 40 bp). The low-quality and contaminated reads were removed on the following criteria to obtain final clean reads: (i) elimination of low quality reads (<q30), (ii) elimination of reads without 3′ adapters, (iii) elimination of reads with 5′ adapters, (iv) elimination of reads without insert, (v) elimination of reads <16 and >40 bp, (vi) elimination of reads not matching to reference genome, (vii) elimination of reads matching to other non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs) [ribosomal (rRNA), transfer (tRNA), small nuclear (snRNA), PIWI-interacting (piRNA), and small nucleolar RNAs (snoRNAs)]. Sequences ≥16 and ≤40 bp length were considered for further analysis (Supplementary Figure S1).

miRNAs were identified by a homology approach against matured human miRNAs. The chromosomal location of previously known miRNAs can be obtained from the miRbase1. All the sequences were aligned to H. sapiens GRCh38 build genome using bowtie-1.1.12. Aligned reads were extracted and checked for other ncRNA (rRNA, tRNA, snRNA, snoRNA, and piRNA) contamination. The unaligned reads to ncRNAs were used for known miRNA prediction. Reads were made unique, and hence, read count profile was generated. Furthermore, a homology search of these miRNAs was done against human mature miRNA sequences retrieved from miRbase-21 (Kozomara and Griffiths-Jones, 2014) using NCBI-BLAST 2.2.30 (Altschul et al., 1990) at e−4 and non-gapped alignment (Supplementary Figure S1).

Sequences not showing hits with known miRNAs were extracted and were considered for novel miRNA prediction. These reads were aligned to the reference genome using bowtie. Novel miRNAs were predicted from the aligned data using Mireap_0.22b (https://github.com/liqb/mireap). To identify true novel miRNAs, predicted candidate miRNAs were matched against human miRNAs predicted in the genomes but not present in miRBase. Unaligned predicted miRNAs were considered as potential novel miRNAs if the predicted secondary structure is a proper stem-loop structure defined for an miRNA (Supplementary Figure S1).

Read count table for all the samples was generated. Differential gene expression (DGE) analysis was carried out using the DESeq (Anders and Huber, 2010) tool. Variations in the reads are normalized by the library normalization method opted from the DESeq library. DESeq calculates the size factor; each read count is normalized by dividing with size factor. Mean normalized read counts of the samples in a given condition are used for DGE calculation and heatmap. For regulation calculation between the comparisons, log2fold of 1 was used as a cutoff. Expression values of miRNAs are DESEq normalized values between samples 1 and 2. Normalized expression of a given miRNA may change with respect to the comparison sample and their library size. Fold changes are calculated based on “expression of treated sample/expression of control sample.” miRNAs >1 were considered as “UP” regulated, miRNAs <−1 were considered as “DOWN,” and those between 1 and −1 were flagged as “NEUTRAL” (Supplementary Figure S1 and Supplementary File S1).

To analyze the overrepresentation of miRNA–gene association in selected immunological pathways, miRNA Enrichment Analysis and Annotation tool (miEAA) (Backes et al., 2016) was used. For each analysis, corresponding miRNAs (upregulated, downregulated, and only expressed in each group) as miRBase IDs (Kozomara et al., 2019) were given as test set (GPKDL), and all the miRNAs expressed in the corresponding group were used as reference set (GTHP and GVL). A significance level of 0.05 [false discovery rate (FDR) corrected P-value] and a threshold of 2 (observed miRNA) was chosen for all the analysis. From the obtained results, the ratio between the observed and expected number of miRNA (for each chosen pathway) was computed for selected pathways using in-house Perl script. All the graphs based on sequencing data were generated using R programming environment.

miRNet2 (Fan and Xia, 2018) was used for constructing miRNA–gene target network. Only the upregulated miRNAs of GPKDL were queried. Interactions reported by crosslinking immunoprecipitation (CLIP) were alone considered for the network generation; all other interactions were removed. The targets in the network were chosen using Reactome knowledgebase (Fabregat et al., 2018) with an algorithm set as a hypergeometric test and with a statistical threshold of P < 0.001. In PKDL, the Th2 response shows the presence and persistence in the skin. Therefore, we are trying to find the networking molecule regulated by miRNAs, which are responsible for modulating the Th2-responsive genes.

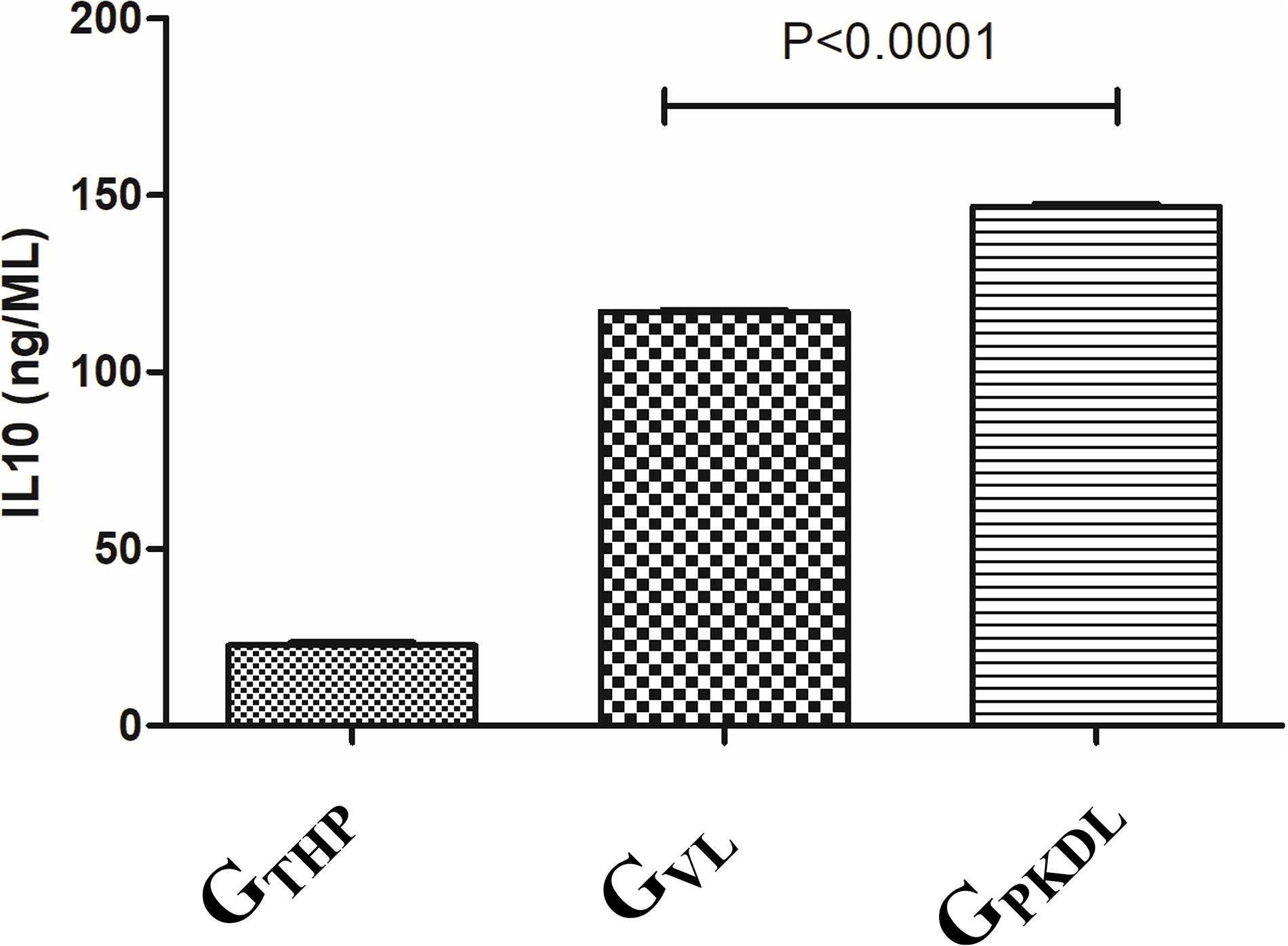

THP cells (1 × 106) were uninfected and infected with 1 × 107 late log phase L. donovani promastigotes (1:10) isolates from VL patients for 12 h. In another set, THP cells were infected with 1 × 107 late log phase L. donovani promastigotes (1:10) isolates from PKDL patients for 12 h. The culture supernatants after incubation were collected and tested for cytokines interleukin (IL)-10 using sandwich ELISA kit (R&D system, United States) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The detection limit of these assays was <5.3 pg/ml for IL-10, respectively. Results are represented as mean ± SD for three independent experiments.

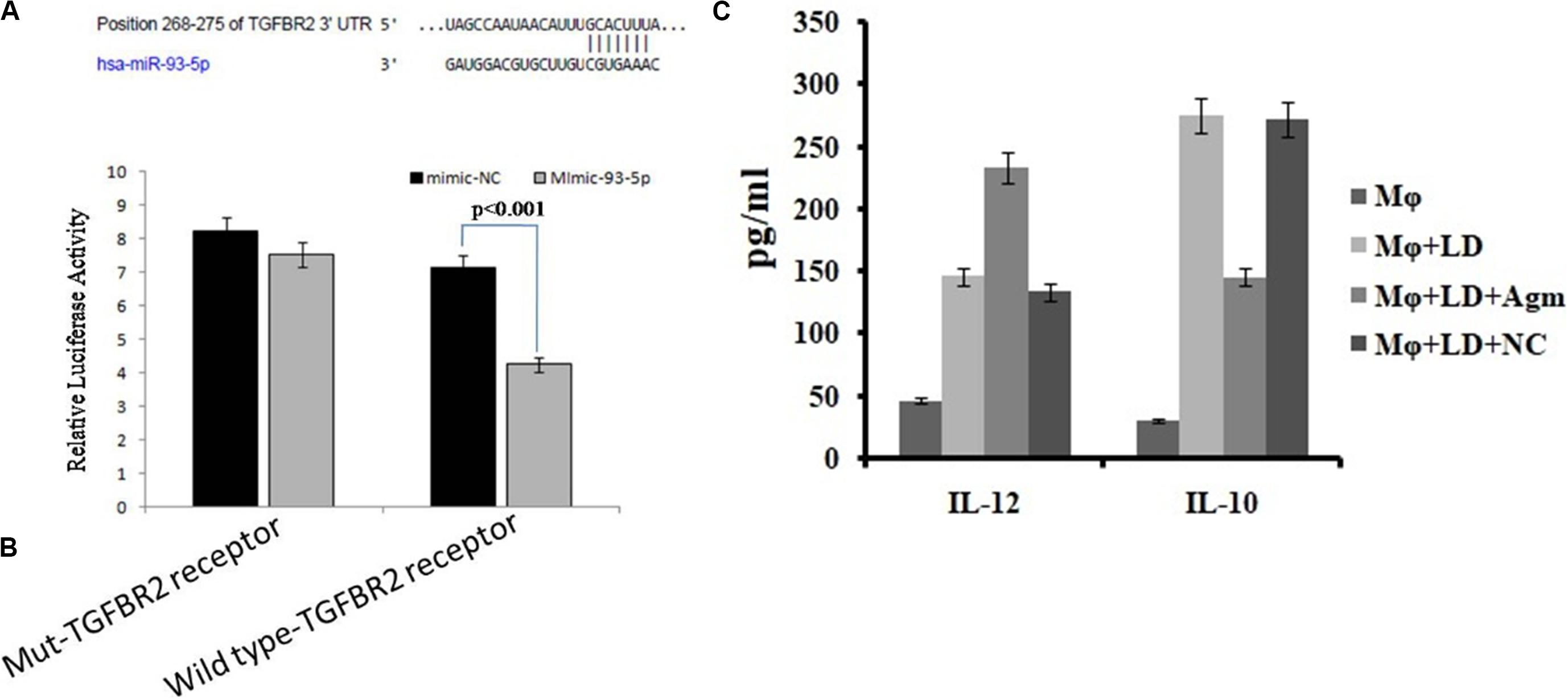

We predicted the target of miRNA-93-5p by online software Target Scan based on target rank and score. The miRNA-93-5p targets TGFBR2 gene, which has a crucial role in immune responses during visceral leishmaniasis. Binding site of miRNA-93-5p and TGFBR2 gene was detected by Target Scan 7.2. The 3′-untranslated region (UTR) of genes of interest containing the putative miRNA target site(s) WT-TGFBR2 gene (wild-type) and Mut-TGFBR2 gene (mutant) was cloned into the XbaI site of the pGL3 control vector containing firefly luciferase gene linked to the 3′-UTR of the gene (Promega, United States). Macrophages were transfected by constructed pGL3 vector with either controls or mimics of miRNA-93-5p Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen, United States). After 24 h, cells were lyzed, and luciferase activity was measured by the dual-gloluciferase assay system (Promega, United States) according to manufacturer’s instruction on luminometer. Firefly luciferase reading was normalized by the renilla luciferase reporter.

The role of miRNA-93-5p in TGFBR2-mediated proinflammatory immune responses was evaluated by silencing with antagomir. The miR-93-5p antagomir was designed in our laboratory and was synthesized by Integrated DNA Technologies, New Delhi, using the sequence, CUACCUGCACGAACAGCACUUUG, with the following modifications: the 2′-OMe-modified bases (2′-hydroxyl of the ribose was replaced with a methoxy group), phosphorothioate (phosphodiester linkages were changed to phosphorothioate) on the first two and last four bases, and an addition of cholesterol motif at 3′ end through a hydroxyproline-modified linkage. Antagomir scramble (mismatched miR-93-5p) was also obtained from the same company and used as negative control. The expression of miR-93-5p was silenced by antagomir according to the standard protocol described previously with required modification. Briefly, macrophages (106 cells/well) were suspended in 500 μl of serum-free media for 2 h at 37°C and 5% CO2 supplemented with 1 mM of antagomir-93-5p or antagomir scramble. After incubation, 150 μl of media containing serum and antibiotics was added and cultured for 24 h in a CO2 incubator. For evaluating the functional role of miR-93-5p, four experimental groups were plotted as follows: (1) uninfected Mφ, (2) Mφ infected with L. donovani, (3) miR-93-5p silenced Mφ infected with L. donovani, and (4) antagomir scramble-treated Mφ infected with L. donovani. Macrophages were incubated in the CO2 incubator with 5% CO2 for 24 h. After 24 h of incubation, supernatants were collected for the measurement of cytokines.

Statistical analysis of the differences between means of groups was performed with two-tailed Student’s t-test and ANOVA on GraphPad Prism 5.0 software. A P < 0.05 was considered significant, and a P < 0.01 was considered highly significant.

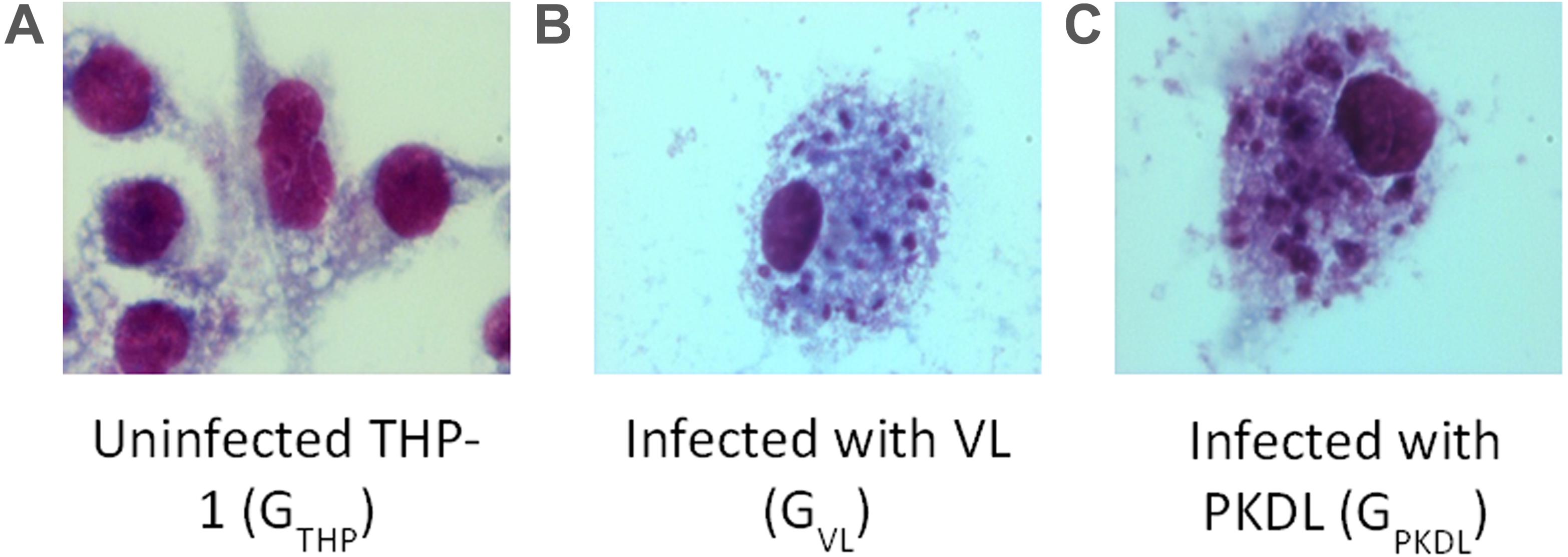

Promastigotes culture of VL and PKDL strains were used for the infection of the human THP-1 cell line. Infection was confirmed by Giemsa staining (Merck) in GVL and GPKDL infection compared to the GTHP groups. At least 100 cells were counted manually for each condition to determine the average number of parasites per macrophage. There were 62 and 64% infected GVL and GPKDL, respectively. Examples of infected cells are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Intracellular Leishmania donovani amastigotes visualized by stain. (A) Uninfected control THP cell. (B) THP cell infected with visceral leishmaniasis (VL) strain (GVL). (C) THP cell infected with post-kala-azar dermal leishmaniasis (PKDL) strain (GPKDL). GVL and GPKDL showed 60–70% infection rate. Optical microscopy at 100× oil immersion.

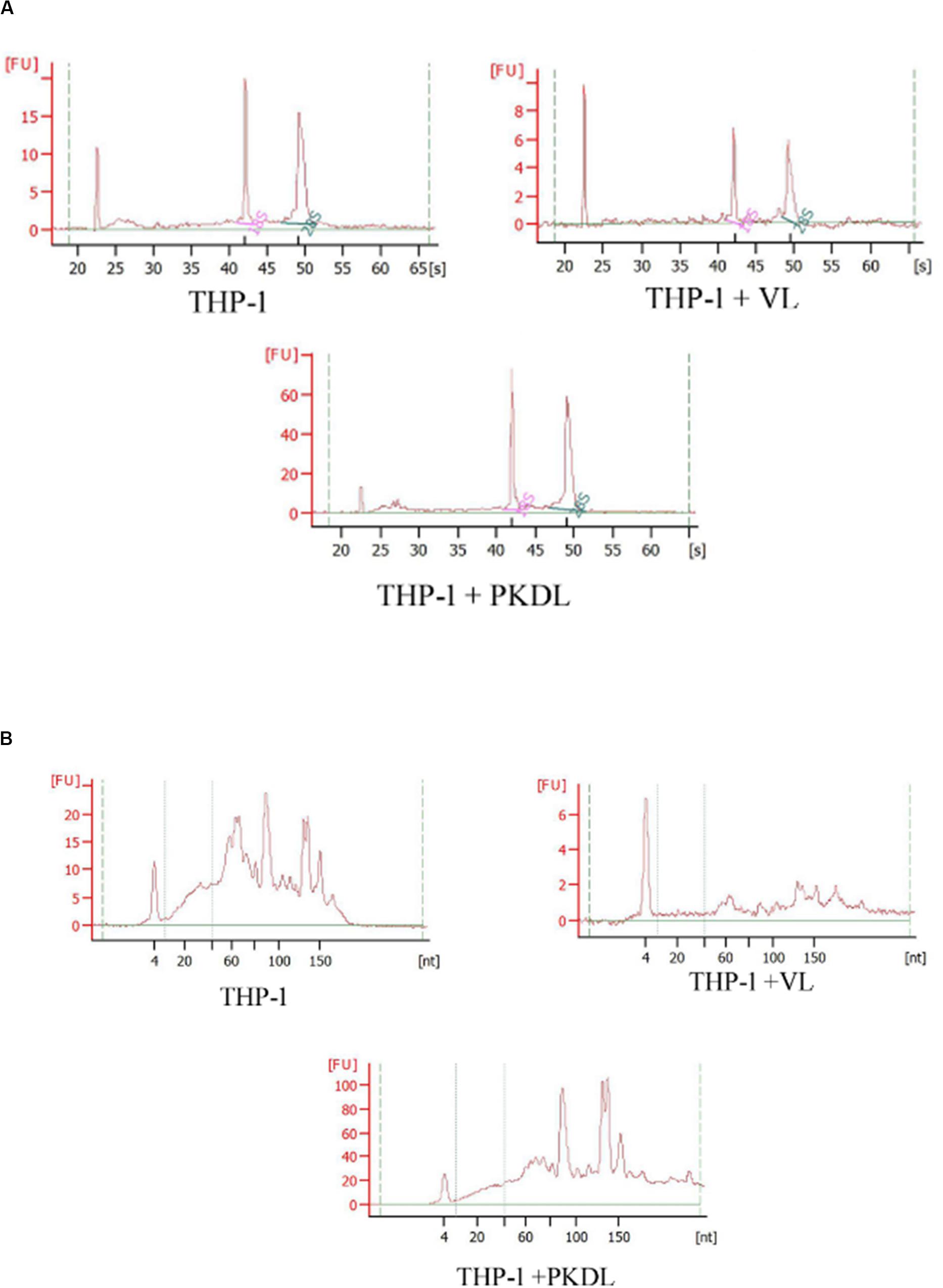

As the quality and integrity of RNA was very crucial for this study, we first evaluated these qualities of the RNA yielded in all experimental infection. Intact eukaryotic total RNA should yield clear 28S and 18S rRNA bands. The 28S rRNA band is approximately twice as intense as the 18S rRNA band (2:1 ratio). Since the human interpretation of gel images is subjective and is inconsistent, we used RNA integrity number (RIN) analysis. Agilent has developed a software algorithm that allows for the calculation of an RIN from a digital representation of the size distribution of RNA molecules (which can be obtained from an Agilent Bioanalyzer). The RIN is based on a numbering system from 1 to 10, with 1 being the most degraded and 10 being the most intact. This approach facilitates the interpretation and reproducibility of RNA quality assessments and provides a means by which samples can be compared in a standardized manner (Figures 2A,B).

Figure 2. RNA integrity assessment based on the ratio of 28S:18S rRNA, estimated from the (A) band integrity or (B) densitometry plot.

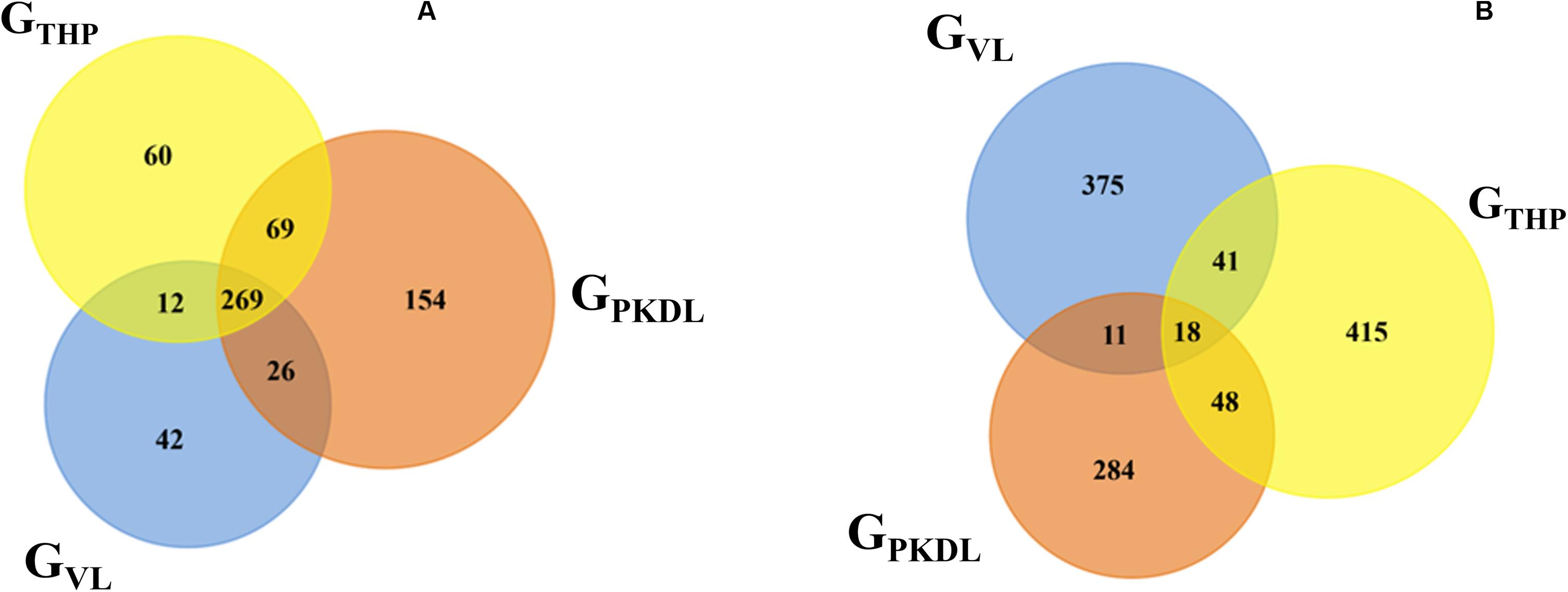

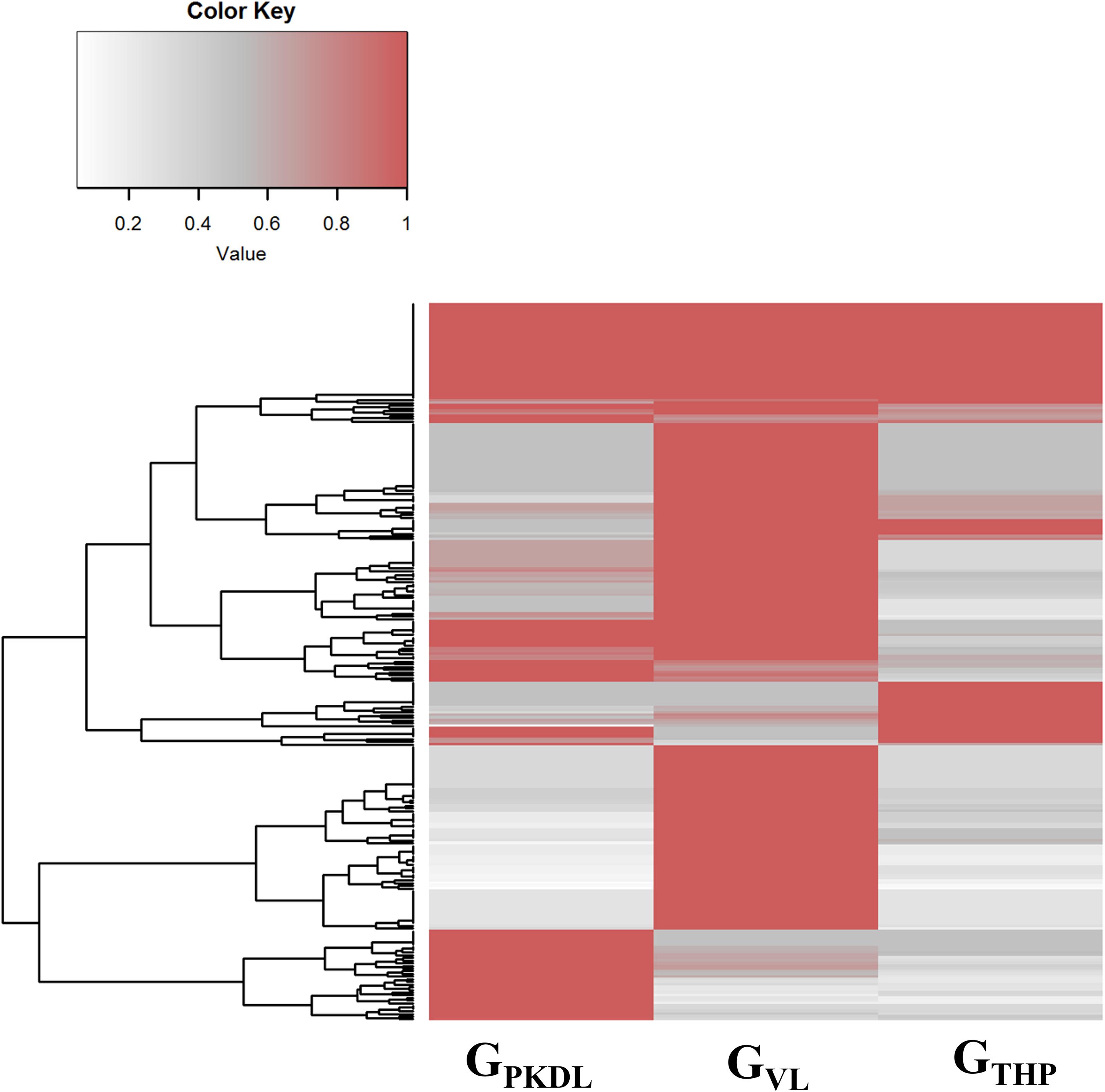

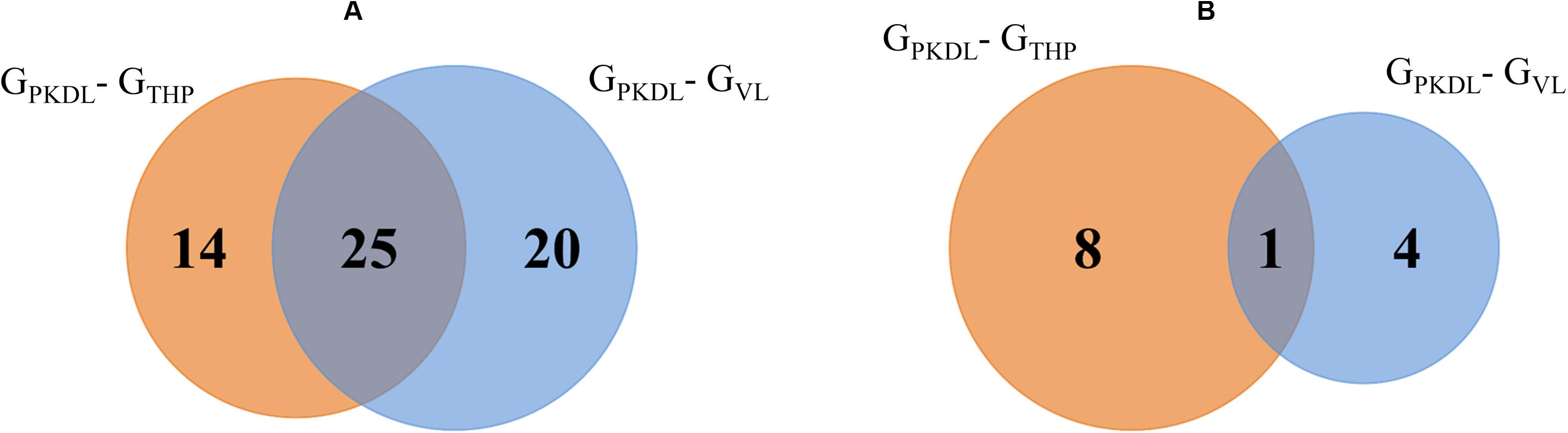

Here, we have identified the differentially expressed known and novel miRNA of GTHP, GVL, and GPKDL groups. NGS analysis confirmed that a total of 935 miRNAs were identified in GTHP, out of which 410 are known miRNAs and 525 are novel miRNAs. With respect to GVL and GPKDL, a total of 798 and 879 miRNAs were identified, out of which 349 and 518 are known miRNAs, respectively. The overlaps of known and novel miRNAs between each group were indicated as the Venn diagram (Figure 3A). It could be observed that a total of 269 known miRNAs was expressed in all three conditions. To infer the difference in miRNA read count between the common identified 269 miRNAs, the read counts of each miRNA were normalized and plotted (Figure 4). The heat map indicates that the read count profile of each group is different. When novel miRNAs were discussed, we identified the 415 novel miRNAs for GTHP, 375 novel miRNAs exclusively for GVL, and 284 novel miRNAs exclusively for GPKDL groups. After the Venn diagram analysis, we observed that 18 novel miRNAs are commonly found in all three conditions (Figure 3B).

Figure 3. Venn diagram showing the differentially expressed overlaps of microRNA (miRNA). (A) Overlaps of known miRNAs between GTHP (THP-1), GVL [visceral leishmaniasis (VL)], and GPKDL [post-kala-azar dermal leishmaniasis (PKDL)] groups. (B) Overlaps of novel miRNAs between GTHP, GVL, and with GPKDL groups.

Figure 4. Commonly expressed microRNAs (miRNAs) of GTHP (THP-1), GVL [visceral leishmaniasis (VL)], and GPKDL [post-kala-azar dermal leishmaniasis (PKDL)] and their corresponding normalized read counts.

To identify the differentially overexpressed miRNAs in GPKDL with respect to GTHP and GVL, we subjected our results to DESeq2 (DGE) analysis:

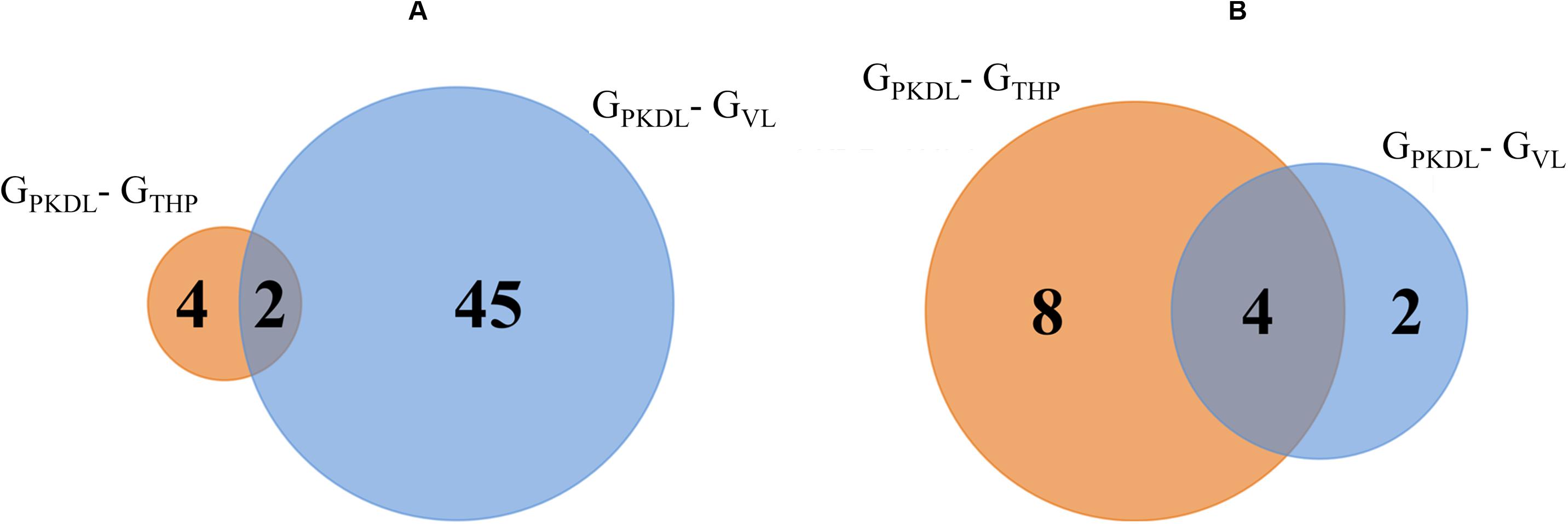

(A) To get separate information about known miRNAs, a total of 39 known miRNAs in GPKDL with respect to GTHP and a total of 45 miRNAs (with respect to GVL) were significantly upregulated in GPKDL (Figure 5A). Moreover, a total of 25 miRNAs are commonly upregulated in both GTHP and GVL groups, while a total of 14 and 20 miRNAs are upregulated only in GTHP and GVL, respectively. The families of miRNA groups are represented in Table 1C and Supplementary Figure S2.

Figure 5. Venn diagram shows the GPKDL upregulated microRNAs (miRNAs). (A) Overlaps of known upregulated miRNAs of GPKDL with respect to GTHP and to GVL. (B) Overlaps of novel upregulated miRNAs of GPKDL with respect to GTHP and GVL.

(B) Similarly, when we focus on novel miRNAs, then we observed eight and four novel miRNAs that are exclusively found in GTHP and GVL, respectively, and one miRNA common among these two conditions (Figure 5B). The sequences of novel miRNAs are represented in Table 1B.

Analysis of known miRNAs that are downregulated in GPKDL condition with respect to GTHP and GVL conditions were performed. We observed that two downregulated miRNAs are common to GTHP and GVL; four miRNAs exclusively downregulated in GTHP and 45 miRNAs exclusively downregulated in GVL (Figure 6A and Table 1D). For novel miRNAs, four miRNAs were commonly observed with GTHP and GVL; eight miRNAs exclusively downregulated in GTHP and two miRNAs exclusively downregulated in GVL (Figure 6B and Table 1A).

Figure 6. Venn diagram shows the post-kala-azar dermal leishmaniasis (PKDL) responsive downregulated microRNA (miRNA). (A) Overlaps of known downregulated miRNAs of GPKDL with respect to GTHP (PKDL–THP-1) and GVL (PKDL–visceral leishmaniasis (VL)]. (B) Overlaps of the novel downregulated miRNAs of GPKDL with respect to GTHP (PKDL–THP-1) and GVL (PKDL–VL).

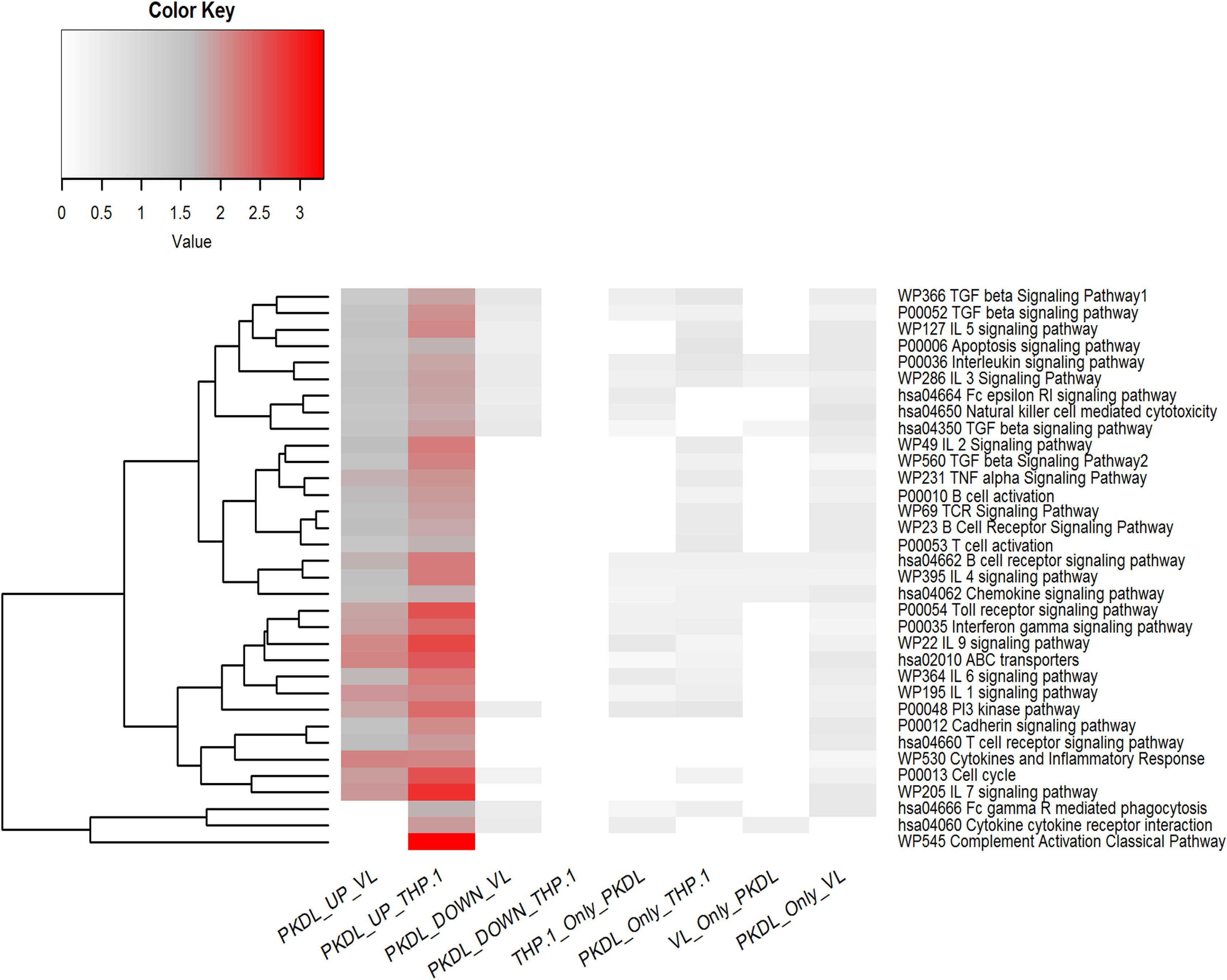

All the differentially expressed miRNAs (up- and downregulated miRNA in GPKDL with respect to GTHP and GVL) were subjected to pathway overrepresentation analysis using the miEAA tool. A total of 35 pathways related to immunological response were selected for the analysis. The expected number of miRNAs and observed number of miRNAs having an miRNA–gene association in selected immunological pathways for each group were analyzed, and the ratio between them was plotted (Figure 7). The result indicates that the miRNAs upregulated in GPKDL (with respect to both GTHP and GVLgroup) are significantly overrepresented in the selected immunological pathways. Interestingly, the downregulated miRNAs and other miRNAs present only in the corresponding groups are underrepresented in the selected immunological pathways. In addition, a marked difference of overrepresentation was observed between GPKDL upregulated miRNAs of GTHP and GVL for three pathways, viz., “hsa04666 Fc gamma R mediated phagocytosis,” “hsa04060 cytokine receptor interaction,” and “P0052 TGF-β signaling pathway.” The miRNA–gene associations of those pathways are overrepresented in GTHP, while in GVL, there was no single miRNA associated with genes of the corresponding three pathways. Studies on the involvement of certain immunological factors such as some cytokines [IL-10, transforming growth factor beta (TGF-β), interferon-gamma (IFN-γ), etc.] and chemokines [macrophage inflammatory protein (MIP-1), regulated upon activation, normal T cell expressed, and secreted (RANTES), etc.] in the dermal lesions of PKDL cases (before and after chemotherapy) may provide insight for any role in the disappearance of lesion and treatment response. The values in the heat map indicate the number of miRNAs having putative gene targets involved in the corresponding pathway.

Figure 7. Pathway enrichment test for differentially expressed microRNAs (miRNAs) (up- and downregulated in GPKDL with respect to GTHP and GVL) and unique miRNAs of GTHP, GVL, and GPKDL. Horizontal lanes are marked with selected immunological pathways, and vertical lanes are marked with comparison groups. The enrichment analysis [false discovery rate (FDR) corrected P < 0.05] for each comparison groups are performed separately with reference set being all expressed miRNAs of the corresponding comparison groups.

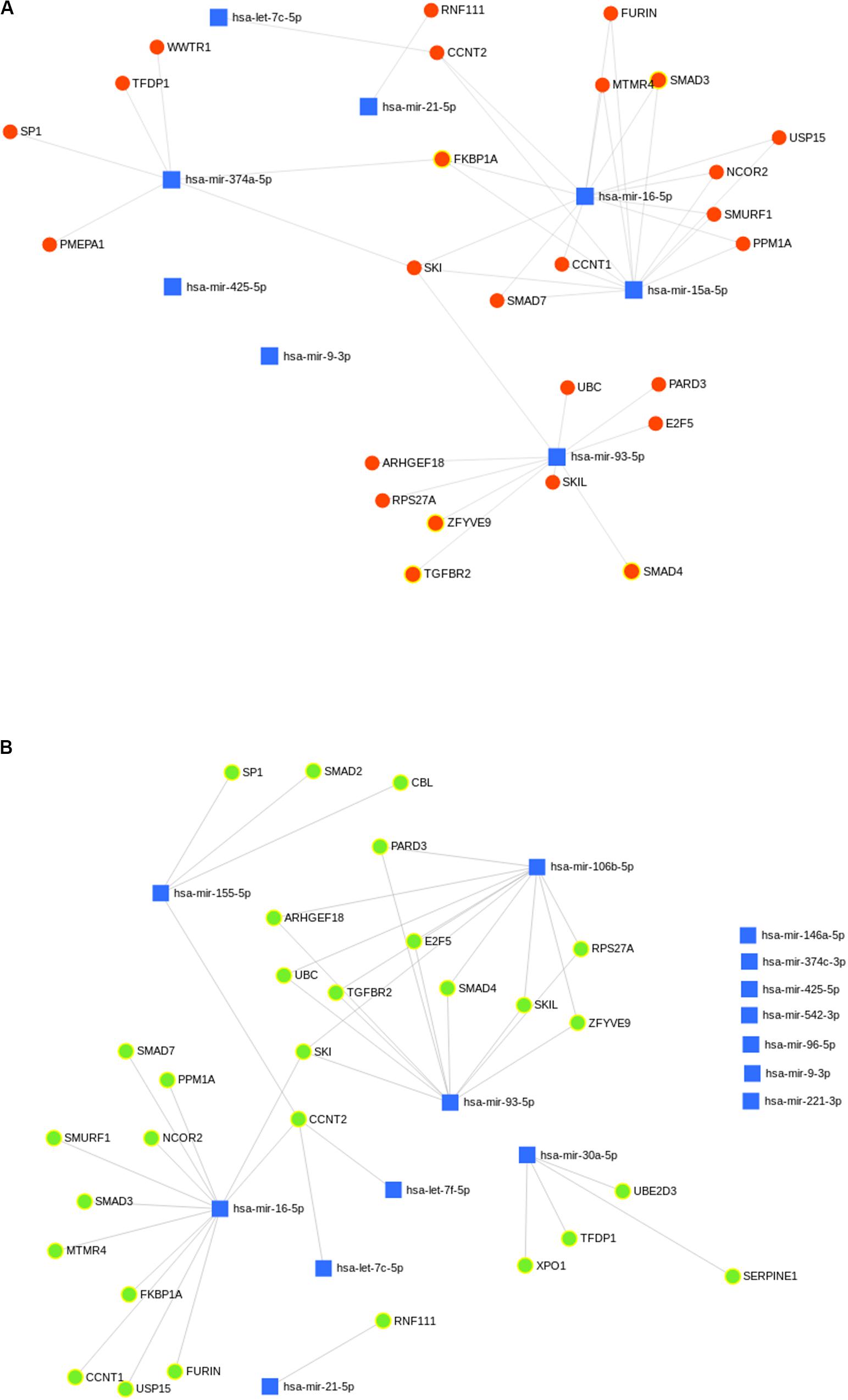

A total of 29 and 26 gene targets belonging to the TGF-beta signaling pathway were mapped to eight and six miRNAs of GTHP and GVL, respectively (Figures 8A,B). Eight and six miRNAs upregulated in GPKDL compared to GTHP and GVL, respectively. Whereas in GVL, out of the 15 upregulated miRNAs, only 8 had one or more gene targets belonging to the TGF-beta signaling pathway. A total of 24 gene targets were commonly observed among the upregulated miRNAs of GTHP and GVL. Gene targets CBL, SERPINE1, SMAD2, UBE2D3, and XPO1 were only observed in the GVL pool, and gene targets PMEPA1 and WWTR1 were only observed in GTHP.

Figure 8. (A,B) Predicted biological processes of upregulated microRNA (miRNA) in GPKDL with respect to (A) GTHP and (B) GVL. The interlinked miRNAs and important pathways linked to macrophage effector functions. The interaction of upregulated miRNAs and their targeted biological processes. The highlighted red and green colors denote interlinked miRNAs with key biological processes relevant to macrophage dysfunction such as cytokine response, immune response, etc.

The immune profile in PKDL cases as well as VL cases was remarkably dissociated mostly; however, due to some differences in immune paradigm, skin rash prevails without systemic illness (Zijlstra et al., 2003). In contrast to the above facts, we have observed ∼1.2-fold production of IL-10 in GPKDL when compared to GVL in the culture supernatant (Figure 9).

Figure 9. THP cells (1 × 106) were uninfected and infected with 1 × 107 late log phase L. donovani promastigotes (1:10) isolates from visceral leishmaniasis (VL) patients for 12 h. In another set, THP cells were infected with 1 × 107 late log phase L. donovani promastigotes (1:10) isolates from post-kala-azar dermal leishmaniasis (PKDL) patients for 12 h. Results are represented as mean ± SD for three independent experiments.

We found that miR-93-5p targets TGFR2 gene, which plays an important role in immune responses during visceral leishmaniasis. Furthermore, for validation of miR-93-5p target genes, we performed the luciferase reporter assay. The transfection with mimic of miR-93-5p significantly (P < 0.001) reduced the luciferase activities of genes fused to TGFBR2 3′-UTR. Mutated 3′-UTR seed sequences of TGFBR2 did not show any significant luciferase activities treated with mimic of miR-93-5p (Figures 10A,B).

Figure 10. Prediction and validation of TGFBR as target gene of miRNA-93-5p. (A) Schematic representation of miRNA-93-5p sequence bound to TGFBR receptor. The luciferase constructs fused to 30 untranslated regions (UTRs) (or Mut) of TGFB receptor were cotransfected in macrophages cells with mimic miRNA-93 or mimic-NC. The luciferase activities were expressed as the ratio of firefly luciferase over renilla luciferase. (B) The macrophages transfected with mimic of miRNA-93 significantly reduced the luciferase activities (P < 0.001) of genes fused to the TGFB receptor family 30 UTR. (C) Effect of antagomir miRNA-93-5p in the activation of interleukin (IL)-10/IL-12 secretion from macrophages after infection.

The release of cytokines in cultured supernatant was measured by cytokine ELISA and is depicted in Figure 10C. The level of proinflammatory cytokines, i.e., IL-12, was significantly higher (P < 0.05) in antagomir-treated macrophages compared to untreated macrophages. However, the level of anti-inflammatory cytokines, i.e., IL-10, in antagomir-treated macrophages was found to be lower (P < 0.001) compared to that in untreated macrophages. The macrophages treated with antagomir scramble did not show significant change in pro- or anti-inflammatory cytokine level compared to untreated macrophages. These results indicated that miR-93-5p has an important role in IL-10 cytokine production during Leishmania infection, and its control can upregulate the production of inflammatory cytokines.

Change in the dynamic cellular environment after infection of any organism depends on the various factors of the cells, and one of the important factors is microRNA. MicroRNA profiling of human macrophage THP-1 cell line infected with L. donovani has revealed enormous information leading to the identification of several key miRNAs that target several immunological signaling cascades (Tiwari et al., 2017). In this study, we have, for the first time, shown the unique microRNA that is exclusively differentially expressed in human macrophage THP-1 cell line after infection with L. donovani isolated from PKDL patients (GPKDL) compared with uninfected THP-1 (GTHP) and THP-1 infected with L. donovani isolated from visceral leishmaniasis patients (GVL) by NGS and their role in immunological pathway regulation.

Next-generation sequencing has become a popular means for miRNA profiling and has led to the identification of 150 known miRNAs and 415 novel miRNAs using the de novo sequencing approach, in which expression levels were largely altered in GPKDL. miRNAs are known to regulate the expression of target genes both at the levels of messenger RNA (mRNA) translation and mRNA stability, leading to a negative correlation between expression levels of these master regulators and their target mRNAs. Furthermore, the in silico analysis acknowledged the role of the immunological pathway that possibly facilitates parasite survival through differential regulation of macrophage effector genes.

As we know, PKDL is a dermal condition that, in Asia, occurs in patients after VL treatment and without any prior infection of VL (Mukhopadhyay et al., 2014). Immune responses in leishmaniasis are often described in terms of a (T helper) Th1 and Th2 response. Elevation of IL-10 and TGF-β probably reflects the role of these cytokines in reactivation of the disease in the form of PKDL (Ismail et al., 1999). TGF-β, TNF-α, IL-10, and IL-12 produced by keratinocyte plays a major role in disease progression while the expression of IFN-γR and TNFR1 was lower in patients with PKDL in India and increased after treatment (Ansari et al., 2006, 2008). It was also reported that, in the PKDL lesion, the upregulation of IL-17 induces TNF-α and NO level (Mukhopadhyay et al., 2014). Biological pathway enrichments were performed using all potential in silico-predicted targets of up- or downregulated miRNAs, regulating the immune responses either by different cytokine regulation, T-cell regulation, TGF-β signaling pathway, Toll-like receptor (TLR)-mediated regulation, ABC transporter regulation, cell cycle analysis, PI3K pathway, etc. in GPKDL with respect to GTHP and GVL. Our analysis showed that miRNAs may reciprocally regulate these pathways and help the parasites in pathogenesis.

The results of the present study demonstrate the regulation of IL-10 as well as of TGF-β in PKDL by different miRNAs, which adds vital information on the mechanism of disease pathogenesis, implicating a role for these cytokines in derailing Th1 responses. Interleukin-10 has a major role in the pathogenesis of VL and PKDL (Ismail et al., 1999). Differences in serum IL-10 levels in VL and PKDL cases provide clue for disease profile and parasite behavior. In a previous study, increased IL-10 is regarded as hallmark of Indian PKDL, as they found IL-10 production enhanced as in PKDL cases as compared to VL cases (Ganguly et al., 2008). Accordingly our results also showed high level of IL-10 and highlighting the importance of the dynamics of the cytokine profiles between VL and PKDL. miRNA levels play an important role in regulating macrophage functions during infection (Lemaire et al., 2013). Several studies have shown the importance of IL-10 and TGF-β in different types of leishmaniasis. In mouse and human studies, both IL-10 and TGF-β have been associated with activation/differentiation of Treg cells (Maloy and Powrie, 2001), which regulate Th1 and Th2 responses. Moreover, Tregs can suppress the activation/maturation, expansion, and differentiation of a variety of immune cell types via several mechanisms, including secretion of anti-inflammatory cytokines like IL-10 and TGF-β, and sequestering IL-2 (Levings et al., 2006). T regulatory cells (Tregs) are a proportion of T cells usually identified by the expression of the transcription factor FoxP3 and a high level of expression of CD25 and in Indian PKDL, an increased presence of forkhead box P3 (FoxP3), a key molecular marker of Tregs (Ganguly et al., 2010). In PKDL, enhanced secretion of IL-10 and TGF-β by antigen-stimulated peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) has been associated with disease severity (Saha et al., 2007). However, TGF-β signaling pathways were among the top 10 most significantly enriched Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathways only for miRNAs upregulated in cells infected with L. donovani (Tiwari et al., 2017). It was reported that miR-21 was shown to facilitate Th17 development through enhancement of the TGF-β signaling pathway by repressing SMAD-7, a negative regulator of TGF-β signaling (Murugaiyan et al., 2015). When we analyzed the TGF-β signaling protein in GPKDL compared to GTHP, we observed the important role of hsa-let7c-5p, hsa-mir21-5p, hsa-mir374-5p, hsa-mir16-5p, hsa-mir15a-5p, and hsa-mir93-5p miRNAs, which regulate these pathways. On the other hand, when we analyzed the GPKDL infected host compared to GVL; then, we observed the significant changes in hsa-mir (155, 106, 30, 93, 6-5p) and Let-7c and 7f-5p miRNAs regulating the TGF-β signaling pathway of the host. Differential expression of miRNA (miR-135, 126, 155, 98, Let-7a-5p,7c etc.) regulates T-cell differentiation and plasticity during VL Infection (Pandey et al., 2016). It was also reported that inhibition of miR-181c-5p, miR-294-3p, miR-30e-5p, and miR-302d-3p reduces the infectivity of Leishmania amazonensis by modulation of Nos2, Tnf, Mcp-1/Ccl2, and RANTES/Ccl5 mRNA expression (Fernandes et al., 2019). Regulation of TGF-β by differentially expressed miRNAs may modulate host immune responses; the rapid onset and termination of diverse effector mechanisms must be efficiently controlled to prevent the adverse consequences of excessive inflammation or pathogenesis. Importantly, IL-10 and TGF-β have been associated with the activation and differentiation of Treg cells. Thus, it might be possible that the negative regulation of TGF-β from infected macrophages can activate Tregs, which then produce more TGF-β, facilitating parasite persistence. miRNAs also help in regulating autophagy by targeting BECN1, and it may have a significant impact on the treatment of leishmaniasis (Singh et al., 2016). Studies on the involvement of immunological factors have shown certain cytokines (IL-10, TGF-β, etc.) in PKDL, which may provide insight for any role in the treatment response (Verma et al., 2014). These references have clearly shown the importance of TGF-β, which is modulated by different miRNAs and validated our in silico data.

In addition, after Leishmania infection, parasites may delay the apoptosis process of the host cells, and we also observed that the mir-155, mir-335, mir-143, mir 221, mir-93, and let7c were found to be associated with negative regulation of apoptosis process, which further suggested the possibility of these miRNAs to obstruct normal functions of macrophage activation in PKDL condition. Our study also states that the upregulation of hsa-miR-146, miR-106, mir-324, mir-221, mir-9, and miR-155 have the potential to downregulate the IFN-γ signaling to help in disease progression during PKDL.

Our study represents a preliminary investigation of host response modulation by host miRNAs associated with PKDL. These findings emphasize the potential of miRNAs in the regulation of macrophage effector functions and highlight their importance in leishmanial pathogenesis that can be targeted to curb PKDL. Besides, the identified miRNAs elucidate their role under immune responses in Indian PKDL patients, revealing a spectral pattern of disease progression where disease severity could be correlated inversely with proliferation and directly with TGF-beta and IL-10. This information will assist in furthering our knowledge of parasitic influences upon host cell responses in PKDL condition at a molecular level, ultimately providing opportunities to investigate new targets for rapid diagnostics or even therapeutic interventions.

The original contributions presented in the study are publicly available. This data can be found here: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/, with accession number PRJNA641999.

SD, AK, and PD designed the experiments. AK, SV, MD, AS, and PD analyzed the data. AK, SD, SV, and RM wrote the manuscript. RM, SV, SD, KA, and AK performed and optimized the experiments. All authors critically revised and approved the manuscript.

This work was supported by the Indian Council of Medical Research, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India and Science and Engineering Research Board under the Department of Science and Technology, Government of India (EMR/2016/002213).

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The authors are extremely grateful to Mr. Amar Kant Singh for providing technical assistance throughout this study.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmicb.2020.01716/full#supplementary-material

FIGURE S1 | Flow chart of work done.

FIGURE S2 | Scatter plot of changes in regulations of known miRNAs in GPKDL versus GVL (A) and versus GTHP (B) shows the scatter plot of upregulation of known miRNAs.

FILE S1 | Fold change information of differentially expressed miRNAs.

Altschul, S. F., Gish, W., Miller, W., Myers, E. W., and Lipman, D. J. (1990). Basic local alignment search tool”. J. Mol. Biol. 215, 403–410. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2

Anders, S., and Huber, W. (2010). Differential expression analysis for sequence count data. Genome Biol. 11:R106. doi: 10.1186/gb-2010-11-10-r106

Ansari, N. A., Katara, G. K., Ramesh, V., and Balotra, P. (2008). Evidence for involvement of TNFR1 and TIMPs in pathogenesis of post kala-azar dermal leishmaniasis. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 154, 391–398. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2008

Ansari, N. A., Ramesh, V., and Salotra, P. (2006). Interferon (IFN)-γ, tumor necrosis factor-α, interleukin-6, and IFN-γ receptor 1 are the major immunological determinants associated with post kala-azar dermal leishmaniasis. J. Infect. Dis. 194, 958–965. doi: 10.1086/506624

Backes, C., Khaleeq, Q. T., Meese, E., and Keller, A. (2016). miEAA: microRNA enrichment analysis and annotation. Nucleic Acids Res. 44, W110–W116. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw345

Besser, J., Carleton, H. A., Gerner-Smidt, P., Lindsey, R. L., and Trees, E. (2018). Next-generation sequencing technologies and their application to the study and control of bacterial infections. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 24, 335–341. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2017.10.013

Czech, B., and Hannon, G. J. (2011). Small RNA sorting: matchmaking for Argonautes. Nat. Rev. Genet. 12, 19–31. doi: 10.1038/nrg2916

Fabregat, A., Jupe, S., Matthews, L., Sidiropoulos, K., Gillespie, M., Hausmann, K., et al. (2018). The reactome pathway knowledgebase. Nucleic Acids Res. 46, 649–655. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkx1132

Fan, Y., and Xia, J. (2018). miRNet—functional analysis and visual exploration of miRNA–target interactions in a network context. Methods Mol. Biol. 1819, 215–233. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-8618-7_10

Fernandes, J. C. R., Aoki, J. I., Acuña, S. M., Zampieri, R. A., Markus, R. P., Floeter-Winter, L. M., et al. (2019). Melatonin and Leishmania amazonensis infection altered miR-294, miR-30e, and miR-302d Impacting on Tnf, Mcp-1, and Nos2 expression. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 9:60. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2019.00060

Ganguly, S., Das, N. K., Panja, M., Pal, S., Modak, D., Rahaman, M., et al. (2008). Increased levels of interleukin-10, and IgG3 are hallmarks of Indian post-kala-azar dermal leishmaniasis. J. Infect. Dis. 197, 1762–1771.

Ganguly, S., Mukhopadhayay, D., Das, N. K., Chadhuvula, M., Sadhu, S., Chatterjee, U., et al. (2010). Enhanced lesional Foxp3 expression and peripheral anergic lymphocytes indicate a role for regulatory T cells in Indian post kala-azar dermal leishmaniasis. J. Invest. Dermatol 130, 1013–1022. doi: 10.1038/jid.2009.393

Geraci, N. S., Tan, J. C., and McDowell, M. A. (2015). Characterization of microRNA expression profiles in leishmania infected human phagocytes. Parasite Immunol. 37, 43–51. doi: 10.1111/pim.12156

Huang, Y., Shen, X. J., Zou, Q., Wang, S. P., Tang, S. M., and Zhang, G. Z. (2011). Biological functions of microRNAs: a review. J. Physiol. Biochem. 67, 129–139. doi: 10.1007/s13105-010-0050-6

Ismail, A., El Hassan, A. M., Kemp, K., Gasim, S., Kadaru, A. E., Moller, T., et al. (1999). Immunopathology of post kala-azar dermal leishmaniasis (PKDL): T-cell phenotypes and cytokine profile. J. Pathol. 189, 615–622. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9896(199912)189

Kozomara, A., Birgaoanu, M., and Griffiths-Jones, S. (2019). miRBase: from microRNA sequences to function. Nucleic Acids Res. 47, D155–D162. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky1141

Kozomara, A., and Griffiths-Jones, S. (2014). miRBase: annotating high confidence microRNAs using deep sequencing data. Nucleic Acids Res. 42, 68–73. doi: 10.4236/nar/gkt1181

Krol, J., Loedige, I., and Filipowicz, W. (2010). The widespread regulation of microRNA biogenesis, function and decay. Nat. Rev. Genet. 11, 597–610. doi: 10.1038/nrg2843

Kumar, B., and Lupold, S. E. (2016). MicroRNA expression and function in prostate cancer: a review of current knowledge and opportunities for discovery. Asian J. Androl. 18, 559–567. doi: 10.4103/1008-682x.177839

Lemaire, J., Mkannez, G., Guerfali, F. Z., Gustin, C., Attia, H., Sghaier, R. M., et al. (2013). MicroRNA expression profile in human macrophages in response to Leishmania in L. major infection. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 7:e2478. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0002478

Levings, M. K., Allan, S., d’Hennezel, E., and Piccirillo, C. A. (2006). Functional dynamics of naturally occurring regulatory T cells in health and autoimmunity. Adv. Immunol. 92, 119–155. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2776(06)92003-3

Liu, J., Jennings, S. F., Tong, W., and Hong, H. (2011). Next generation sequencing for profiling expression of miRNAs: technical progress and applications in drug development. J. Biomed. Sci. Eng. 4, 666–676. doi: 10.4236/jbise.2011.410083

Maloy, K. J., and Powrie, F. (2001). Regulatory T cells in the control of immune pathology. Nat. Immunol. 2, 816–822. doi: 10.1038/ni0901-816

Mukhopadhyay, D., Dalton, J. E., Kaye, P. M., and Chatterjee, M. (2014). Post kala-azar dermal leishmaniasis: an unresolved mystery. Trends Parasitol. 30, 65–74. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2013.12.004

Murugaiyan, G., da Cunha, A. P., Ajay, A. K., Joller, N., Garo, L. P., Kumaradevan, S., et al. (2015). MicroRNA-21 promotes Th17 differentiation and mediates experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J. Clin. Invest 125, 1069–1080. doi: 10.1172/JCI74347

Pandey, R. K., Sundar, S., and Prajapati, V. K. (2016). Differential expression of miRNA regulates T cell differentiation and plasticity during visceral leishmaniasis infection. Front. Microbiol. 7:206. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.00206

Saha, S., Mondal, S., Ravindran, R., Bhowmick, S., Modak, D., Mallick, S., et al. (2007). IL-10- and TGF-beta-mediated susceptibility in Kala-azar and Post-kala-azar dermal leishmaniasis: the significance of amphotericin B in the control of Leishmania donovani infection in India. J. Immunol. 179, 5592–5603. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.8.5592

Singh, A. K., Pandey, R. K., Shahab, C., and Madhubala, R. (2016). MicroRNA expression profiling of Leishmania donovani-infected host cells uncovers the regulatory role of MIR30A-3p in host autophagy. Autophagy 12, 1817–1831. doi: 10.1080/15548624.2016.1203500

Singh, V. P., Ranjan, A., Topno, R. K., Verma, R. B., Siddique, N. A., Ravidas, V. N., et al. (2010). Estimation of under-reporting of visceral leishmaniasis cases in Bihar, India. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 82, 9–11. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2010.09-0235

Su, Y. J., Lin, I. C., Wang, L., Lu, C. H., Huang, Y. L., and Kuo, H. C. (2018). Next generation sequencing identifies miRNA-based biomarker panel for lupus nephritis. Oncotarget 9, 11–19. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.25575

Tiscornia, G., and Belmonte, J. C. I. (2010). MicroRNAs in embryonic stem cell function and fate. Genes Dev. 24, 2732–2741. doi: 10.1101/gad.1982910

Tiwari, N., Kumar, V., Gedda, M. R., Singh, A. K., Singh, V. K., Singh, S. P., et al. (2017). Identification and characterization of miRNAs in response to Leishmania donovani infection: delineation of their roles in macrophage dysfunction. Front. Microbiol. 8:314. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.00314

Verma, N., Bimal, S., Das, V. N. R., Pandey, K., Singh, D., Lal, C., et al. (2014). Clinicopathological and immunological changes in indian post kala-azar dermal leishmaniasis (PKDL) cases in relation to treatment. A retrospective study. BioMed Res. Int. 2015:745062. doi: 10.1155/2015/745062

World Health Organization [WHO] (2010). Control of the leishmaniases. World Health Organ. Tech. Rep. Ser. 949, 22–26.

Zhang, W. D., Yu, X., Fu, X., Huang, S., Jin, S. J., Ning, Q., et al. (2014). MicroRNAs function primarily in the pathogenesis of human anencephaly via the mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling pathway. Genet. Mol. Res. 13, 1015–1029. doi: 10.4238/2014.February.20.3

Zijlstra, E. E., Alves, F., Rijal, S., Arana, B., and Alvar, J. (2017). Post-kala-azar dermal leishmaniasis in the Indian subcontinent: a threat to the South-East Asia Region Kala-azar elimination program. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 11:e0005877. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0005877

Zijlstra, E. E., Khalil, E. A., Kager, P. A., and El-Hassan, A. M. (2000). Post-kala-azar dermal leishmaniasis in the Sudan: clinical presentation and differential diagnosis. Br. J. Dermatol. 143, 136–143. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.2000

Keywords: PKDL, miRNA, TGF-β, T cell, immune regulation

Citation: Kumar A, Vijaykumar S, Dikhit MR, Abhishek K, Mukherjee R, Sen A, Das P and Das S (2020) Differential Regulation of miRNA Profiles of Human Cells Experimentally Infected by Leishmania donovani Isolated From Indian Visceral Leishmaniasis and Post-Kala-Azar Dermal Leishmaniasis. Front. Microbiol. 11:1716. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2020.01716

Received: 27 March 2020; Accepted: 30 June 2020;

Published: 31 July 2020.

Edited by:

Juarez Antonio Simões Quaresma, Evandro Chagas Institute, BrazilReviewed by:

Saikat Majumder, University of Pittsburgh, United StatesCopyright © 2020 Kumar, Vijaykumar, Dikhit, Abhishek, Mukherjee, Sen, Das and Das. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Sushmita Das, c3VzaG1pdGEuZGUyMDA4QGdtYWlsLmNvbQ==

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.