- 1School of Food Science, Washington State University, Pullman, WA, United States

- 2Department of Biological Systems Engineering, Washington State University, Pullman, WA, United States

Almond are among the most consumed tree nuts and used in a variety of food products. Recent almond butter recalls due to potential contamination of Listeria monocytogenes highlight the need to control L. monocytogenes in almond products. The objectives of this study were to examine the stability of L. monocytogenes in almond meal during extended storage and analyze thermal resistance of L. monocytogenes in almond meal of controlled moisture contents or water activity (aw) using thermal death time (TDT) cells and thermal water activity (TWA) cells, respectively. L. monocytogenes maintained a stable population in almond meal for 44–48 weeks at 4°C regardless of aw; however, we observed about 1.69 and 2.14 log10 colony-forming units (CFU)/g reduction of L. monocytogenes in aw 0.25 and 0.45 almond meal over 44 to 48 weeks of storage at 22°C. Under all test conditions using either TDT or TWA cells, the inactivation kinetics of L. monocytogenes in almond meal fitted the log-linear model well; thermal resistance of L. monocytogenes in almond meal was inversely related to the aw of samples. D75-/D80-values of L. monocytogenes in aw 0.25 and 0.45 almond meal obtained using TDT cells were 47.6/22.0 versus 17.2/11.0 min, respectively. D80-, D85-, and D90-values of L. monocytogenes in aw 0.25 almond meal obtained using TWA cells were 59.5 ± 2.1, 27.7 ± 0.7, and 13.2 ± 1.1 min, respectively, in contrast to 22.0 ± 1.1, 10.6 ± 0.2, and 4.6 ± 0.4 min obtained using TDT cells. The z-value of L. monocytogenes in aw 0.25 almond meal was not affected by TWA and TDT cell type (15.4–15.5°C), whereas z-value of L. monocytogenes in aw 0.45 almond meal was 10°C higher than that in aw 0.25 almond meal. This study contributes to our understanding of L. monocytogenes in nuts and impacts of aw on the development of thermal resistance in low-moisture foods.

Introduction

Low-moisture foods, also called low water activity (aw) foods (LawF), have been implicated in numerous foodborne pathogen outbreaks linked to diverse foods including the recent Escherichia coli O26 outbreak in wheat flour (CDC, 2019) and nationwide Salmonella outbreaks related to almonds (CDC, 2004), peanut butter, and its products (CDC, 2009). Despite the increasing foodborne outbreaks associated with LawF, there is a general lack of knowledge related to the behavior of Listeria monocytogenes in LawF especially in nuts during thermal treatment.

Listeria monocytogenes is an important foodborne pathogen with a 20 to 30% mortality rate (Buchanan et al., 2017). Listeriosis outbreaks have historically been involved in ready-to-eat meats (CDC, 1999, 2000; Gottlieb et al., 2006), frequently linked to soft-cheese (Todd, 2011; FDA, 2017a), and recently implicated in fresh produce outbreaks such as cantaloupes (CDC, 2011), caramel apples (CDC, 2015), frozen vegetables (CDC, 2016), and mushrooms (CDC, 2020). L. monocytogenes was found in flour and dried nuts and seeds (Mena et al., 2004) and buckwheat flour (Losio et al., 2017). L. monocytogenes remained stable in dry almond kernels or shelled pistachios (Kimber et al., 2012), powdered infant formula (Koseki et al., 2015), and non-fat dry milk (NFDM) powder (Ballom et al., 2020) during 1-year cold storage.

Almonds are one of the most consumed tree nuts with high nutritional values. Dietary almond intakes are beneficial in controlling glycemia, adiposity, and lipid profile (Jenkins et al., 2006; Li et al., 2011). The United States is the largest producer of almonds, accounting for ∼80% of almonds around the world (Perez and Pollack, 2005). Almond meal is a common ingredient used in a variety of food products. In commercial practices, raw almonds or almond meal are often kept for 1 year or longer, depending on storage temperatures. However, foodborne pathogens such as Salmonella, L. monocytogenes, and E. coli O157:H7 can survive in almond kernels and almond meal (Kimber et al., 2012; Cheng and Wang, 2018) over 1-year storage at over a wide range of temperatures. Recent recalls associated with almond butter (FDA, 2018) and roasted unsalted almonds (FDA, 2017c) due to potential contamination with L. monocytogenes heighten a need to control L. monocytogenes in almond and low-moisture almond products. However, no information about thermal resistance of L. monocytogenes in almond meal is available.

The aw of a food system is thermodynamic. The aw of food products changes during heating in sealed containers; the degree of such change depends on the food composition; and initial aw (Labuza, 1968; Syamaladevi et al., 2016; Tadapaneni et al., 2017). To maintain a constant aw during heating, the thermal water activity (TWA) cells were recently designed by Washington State University, where the aw of treatment samples within the test cell microenvironment was controlled by a LiCl solution with a specific molarity (Tadapaneni et al., 2018). This study was to evaluate the thermal resistance of L. monocytogenes in almond meal in sealed thermal death time (TDT) cells, in which the moisture content of foods is maintained constant, whereas the aw of foods changes in response to heat treatment. Survival of L. monocytogenes in almond meal was further tested under constant aw using TWA cells. In addition, the fates of L. monocytogenes in almond meal during 44–48 weeks storage at different temperatures under controlled aw were examined.

Materials and Methods

Proximate Analyses and Particle Distribution of Almond Meal

Almond meal was a generous gift from the Almond Board of California (Modesto, CA, United States). Proximate analyses of moisture content, ash content, crude protein, crude fats, and total carbohydrates of almond meal were determined using the standard methods described by the Association of Official Analytical Chemists (AOAC, 2000). A portion of almond meal was classified into different particle sizes through a set of screens (model 78–700; Fieldmaster, Science First, Yulee, FL, United States).

Bacterial Strains and Bacterial Lawn Preparation

Three L. monocytogenes serotypes, 1/2a, 1/2b, and 4b, cause the majority of human cases (CDC, 2013). Thus, two L. monocytogenes outbreak strains, NRRL B-57618 (1/2a, 2011 cantaloupe outbreak), and NRRL B-33053 (4b, 1983 coleslaw outbreak), and one processing plant L. monocytogenes isolate, NRRL B-33466 (1/2b), were used to prepare a three-strain cocktail. All strains were maintained at −80°C in trypticase soy broth [Becton, Dickinson and Company (BD), Sparks, MD, United States] supplied with 0.6% yeast extract (Fisher Scientific, Fair Lawn, NJ, United States) (TSBYE) and 20% (vol/vol) glycerol in a biosafety level 2 (BSL-2) microbiology laboratory. Lawn grown of each L. monocytogenes on trypticase soy agar with 0.6% yeast extract (TSAYE) plates was collected and mixed in equal proportions to prepare the three-strain cocktail (Taylor et al., 2018; Tsai et al., 2019b).

The inoculum preparation, almond meal inoculation and equilibration, isothermal inactivation, and long-term storage studies were all conducted in a BSL-2 microbiology laboratory.

Inoculation and Equilibration

One hundred grams of almond meal was inoculated with 1.0 mL of a three-strain L. monocytogenes cocktail [∼1 × 1011 colony-forming units (CFU)/mL] inside a stomacher bag (Fisher Scientific) and hand mixed, then stomached for 2 min. For each inoculation batch, the bacterial populations of three 1.0-g inoculated almond meal samples were randomly sampled, serially diluted, plated on TSAYE plates in duplicate, incubated at 35 ± 2°C for 48 h, then enumerated to verify the uniformity of inoculum distribution and initial inoculation level (∼1 × 109 CFU/g).

Inoculated almond meal was partitioned into two 150-mm Petri dishes (Fisher Scientific), 50 g per Petri dish. Samples were placed into an aw equilibration chamber (custom-designed at Michigan State University) (Smith et al., 2016) set at target aw (0.25 and 0.45) and equilibrated for a minimum of 4 days at 22°C to the target aw ± 0.02. The aw of the respective almond meal samples was monitored in triplicate by an Aquameter (Aqualab Series 3; Decagon Devices, Inc., Pullman, WA, United States). Samples were used for thermal inactivation after reaching the target aw ± 0.02.

Isothermal Treatment

TDT and TWA Cells

The isothermal treatments of L. monocytogenes in almond meal of the selected aw were first conducted using the aluminum TDT cells that was designed at Washington State University (Chung et al., 2008) mimicking the commercial heat treatment in a sealed heating unit. In the sealed TDT cells, the moisture content of foods is maintained constant during heat treatment, whereas the aw of foods subjected to dynamic changes in response to heat treatments.

To evaluate the impacts of aw at treatment temperature on L. monocytogenes survival in almond meal, the isothermal inactivation of L. monocytogenes in almond meal was conducted using our newly designed TWA cells under a constant aw (Tadapaneni et al., 2018) as described below. A TWA cell consisted of an aluminum lid, an aluminum base, and a rubber O-ring that was tightly fitted into lid and the base of TWA cells to prevent the leakage of moisture during thermal treatments (Figure 4D). The base part of the TWA cell included a central sample loading well and a surrounding LiCl solution of the selected aw. Given that a LiCl solution has a relatively stable aw during heat treatments, it creates a stable relative humidity environment within the TWA cells to maintain a constant aw of the food sample during heating.

Thermal Inactivation Using TDT Cells

Following the 4-day of equilibration, ∼0.60 g of inoculated almond meal was loaded into and sealed in TDT cells. The loaded TDT test cells were subjected to isothermal treatments (70–85°C) in an ethylene glycol bath (Isotemp Heat Bath Circulator, model 5150 H24; Fisher Scientific). The temperature of ethylene glycol bath was calibrated by Omega Precision RTD temperature recorder (OM-CP-RTDTemp2000; Omega Engineering Inc., Norwalk, CT, United States). Loaded TDT cells with T-type thermocouples at the sample geometrical center were used to measure heat penetration and come-up time (CUT). The resulting CUT was 1.5 min, after which heat treatment timing was initiated. For each heat treatment, triplicate samples at each of five time points were withdrawn and immediately chilled in an ice-water bath for ∼2.0 min. All tests were conducted in triplicate, and each thermal inactivation was repeated three times independently. For each independent repeat, the equilibrated inoculated almond meal of a select aw were subjected to isothermal treatments within 7 days.

Thermal Treatment Using TWA Cells

Parallel to the tests described above, the inoculated aw 0.25 almond meal samples were subjected to isothermal treatment at a constant aw using TWA cells (Tadapaneni et al., 2018). Prior to the tests, ∼0.60 g of inoculated almond meal equilibrated at aw 0.25 was loaded into the center well of a TWA cell. In addition, a 12.86 M LiCl solution, which corresponded to aw of 0.25 or an equilibrium relative humidity of 25%, was loaded into the surrounding well of the TWA cell. The aw of the LiCl solution was confirmed using an Aquameter (Aqualab Series 3). The loaded cell was sealed, carefully placed on a horizontal plate, and equilibrated overnight at 22°C. The TWA cells were subjected to isothermal treatments (80–90°C) in an ethylene glycol bath (Fisher Scientific) as described for thermal inactivation with TDT cells. All tests were conducted in triplicate, and each thermal inactivation was repeated three times independently. For each independent repeat, the equilibrated inoculated almond meal of a select aw were subjected to isothermal treatments within 7 days.

Enumeration of Background Flora in Almond Meal

The absence of L. monocytogenes in receiving almond meal samples was corroborated per our previous method (Sheng et al., 2019). Briefly, ten 10-g samples were randomly sampled and homogenized in 90 mL buffered Listeria enrichment broth (BLEB; BD), non-selectively enriched for 4 h at 30°C, followed by additional 24- to 48-h selective enrichment with 10 mg/L acriflavin (TCI, Portland, OR, United States), 50 mg/L cycloheximide (Amresco, Solon, OH, United States), and 40 mg/L nalidixic acid (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, United States). The enrichment culture was streaked onto modified Oxford agar (MOX; BD) and incubated at 35°C for 48 h.

For background microflora enumeration, three 1.0-g almond meal samples were randomly sampled and serially diluted. The appropriate serial dilutions were plated on TSAYE plates in duplicate and then incubated at 35 ± 2°C for 24 h before enumeration.

L. monocytogenes Survival in Almond Meal

Heat-treated almond meal samples were transferred from TDT or TWA cells to a Whirl-Pak® bag (Nasco, Ft. Atkinson, WI, United States), weighed, and diluted 1:10 with sterile phosphate-buffered saline (pH 7.4) and then homogenized for 2 min at 230 revolutions/min in a stomacher (Seward Stomacher® Circulator 400). The recovered bacterial suspensions were 10-fold serially diluted. The appropriate dilutions were plated TSAYE plates in duplicate, which were incubated at 35 ± 1°C for 3 h for the recovery of injured cells and then overlaid with a thin layer of MOX to discern L. monocytogenes from resident background microflora (Sheng et al., 2018) and then incubated at 35 ± 2°C for additional 40 to 48 h.

L. monocytogenes Survival in Almond Meal Under Different aw and Storage Temperatures

Almond meal was inoculated and equilibrated as described in Inoculation and Equilibration. Following 7 days of equilibration at aw 0.25 ± 0.02 or 0.45 ± 0.02, the inoculated almond meal was aliquoted, sealed in moisture-barrier bags (Dri-Shield 3000®; Desco Industries, Inc., CA, United States), and then subjected to 44- to 48-week storage at room temperature (RT, 22°C) or refrigerated temperature (4°C). The inoculated almond meal under respective storage were sampled at 1 and 4 weeks of storage and then every 4 or 8 weeks until the end of storage. Survival of L. monocytogenes was analyzed at the selected sampling points per the above described method. The aw of samples inside each moisture barrier bag was monitored at each sampling day. Two sets of biologically independent inoculated almond meal were prepared. For each independent set, there were three samples at each storage sampling time.

D-Value and z-Value Analysis

The following first-order kinetic model was utilized to analyze the thermal inactivation kinetics data (Peleg, 2006):

where t is the time of the isothermal treatment (min) after the come-up to the specified treatment temperature; N0 is the initial bacteria population at t = 0; N is the bacteria population at specific time (t); and D is the time in minutes required to reduce the microbial population by 90% at a selected temperature (°C). D-values were estimated from the thermal inactivation curve using log-linear regression analysis at inactivation temperature. The z-values, in °C, were determined from the decimal reduction time curves of log D-value versus temperature and were calculated as z = −slope–1.

Statistical Analyses

Data were analyzed by one-way analysis of variance, and mean differences were separated by Tukey multiple-comparisons test using the generalized linear model from Statistical Analysis Systems (SAS, 2000). P values of less than 0.05 were considered significant.

Results

Chemical Composition and Particle Size Distribution

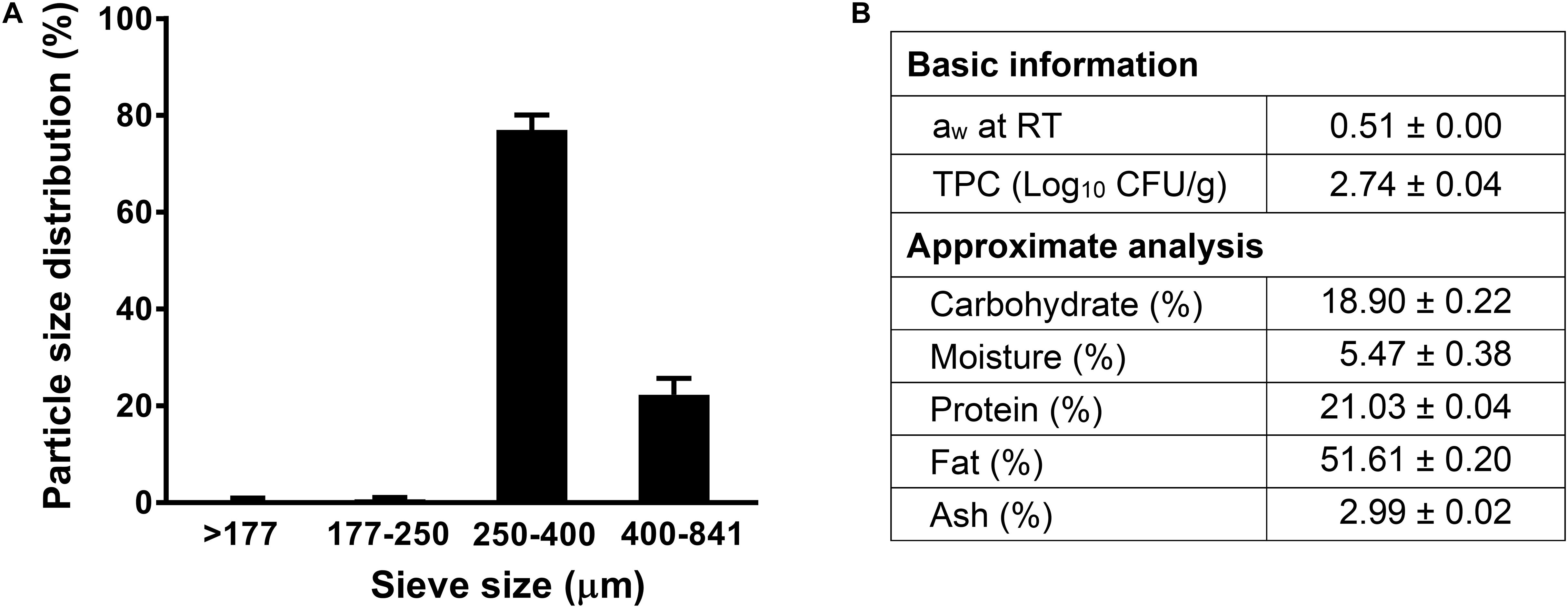

The aw of receiving almond meal used in this study was 0.51 at 22°C (Figure 1). The background microbiota of the non-inoculated almond meal samples was 2.74 ± 0.04 log10 CFU/g. The proximate chemical composition analyses showed that almond meal contained 51.6% fat, 21.0% protein, and 18.9% carbohydrate (Figure 1). The 80% of particle size of almond meal ranged from 250 to 400 μm (Figure 1).

Figure 1. The particle size distribution and proximate analysis composition of almond meal. (A) Particle size distribution; (B) Basic and proximate composition. TPC, total plate count. Mean ± SEM, n = 3. aw, water activity measured at 22°C. RT, room temperature, 22°C.

Fate of L. monocytogenes in Almond Meal During Extended Storage at 4 and 22°C

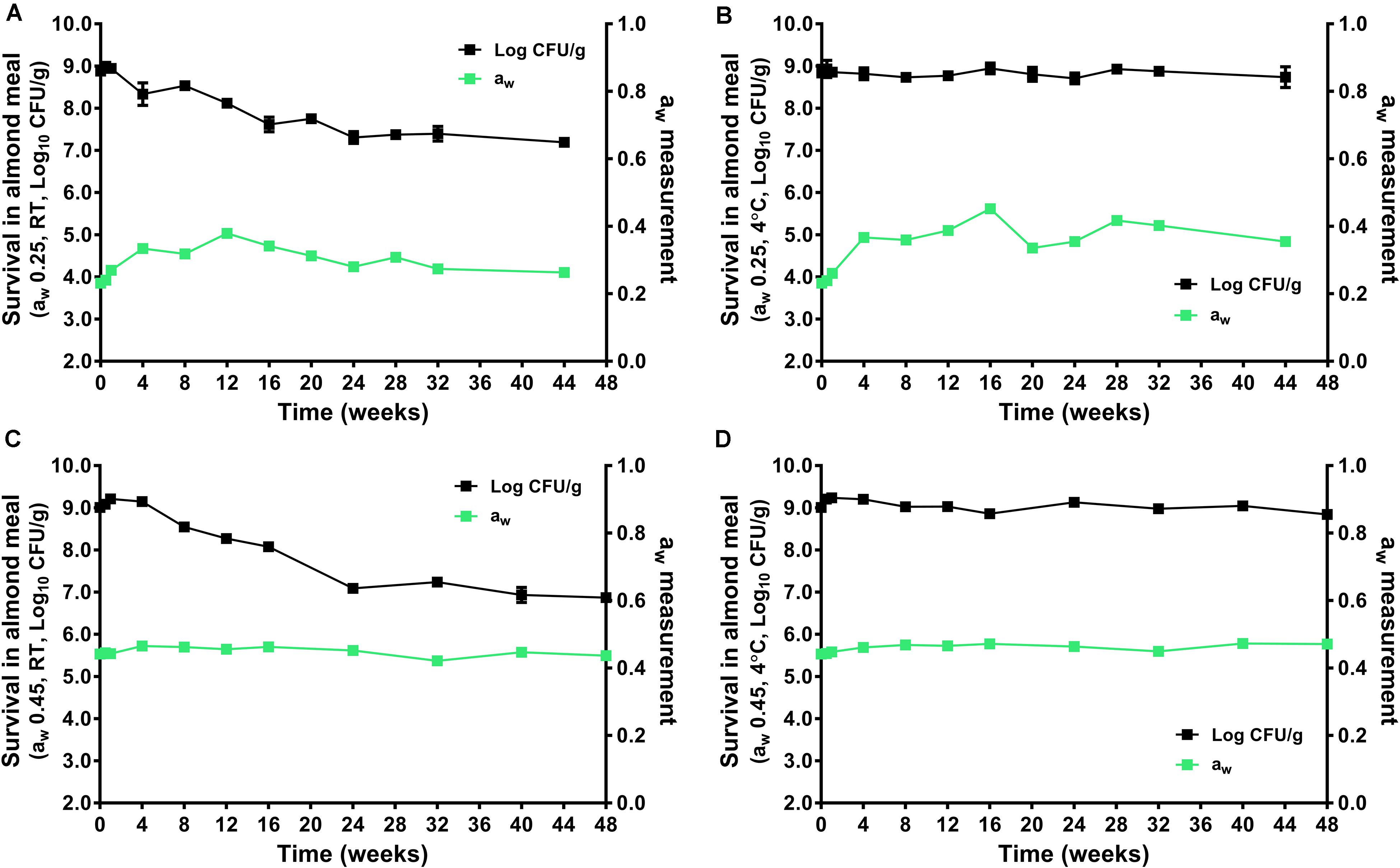

During the 44–48 weeks of storage at 4 and 22°C, the aw of almond did not change significantly (Figure 2). The L. monocytogenes populations remained stable in aw 0.25 and 0.45 almond meal stored at 4°C over 44 to 48 weeks. There was only 0.20 and 0.17 log10 CFU/g reduction for the aw 0.25 and 0.45 almond meal, respectively (Figures 2B,D). But L. monocytogenes populations declined at 22°C, especially in aw 0.45 almond meal. There was 1.69 and 2.14 log10 CFU/g reduction of L. monocytogenes in aw 0.25 and 0.45 almond meal over 44- to 48-week storage, respectively (Figures 2A,C).

Figure 2. The survival of L. monocytogenes in almond meal during over the course of 44- to 48-week storage period at 4 and 22°C. (A) aw 0.25, 22°C; (B) aw 0.25, 4°C; (C) aw 0.45, 22°C; and (D) aw 0.45, 4°C. The solid line and filled square in black represent the microbial count; the solid line and filled square in green represent aw of almond meal under respective storage. Experiments were repeated independently twice. aw: water activity measured at 22°C. RT: room temperature, 22°C.

Thermal Inactivation of L. monocytogenes in Almond Meal With TDT and TWA Cells

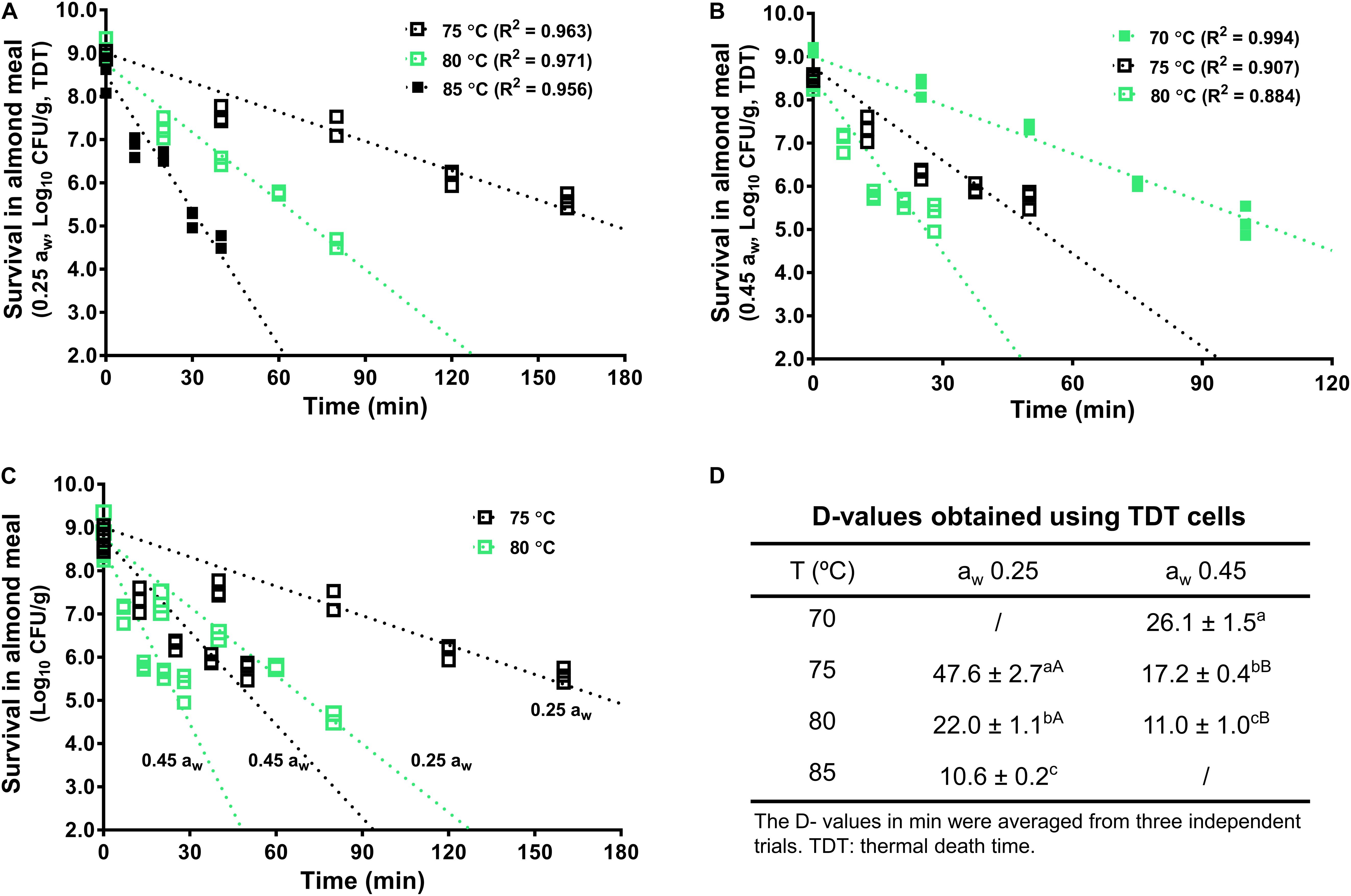

The inactivation kinetics of L. monocytogenes in almond meal using TDT cells were fitted using log-linear modeling (Figure 3). Based on the trend lines of the log-linear model, D-value at 70°C (D70-value) for L. monocytogenes in almond meal preconditioned to aw 0.45 was 26.1 ± 1.5 min (Figure 3). D75-values at aw 0.25 and 0.45 were 47.6 ± 2.7 and 17.2 ± 0.4 min, respectively. D80-values at aw 0.25 and 0.45 were 22.0 ± 1.1 and 11.0 ± 1.0 min, respectively (Figure 3). At each temperature, the inactivation rates of L. monocytogenes in almond meal, as characterized by the slopes of log-linear fitting line, increased as aw increased.

Figure 3. The representative thermal inactivation kinetic curves and D-values of L. monocytogenes in almond meal at the selected temperatures. (A) aw 0.25, (B) aw 0.45, (C) aw 0.25 and 0.45. (D) D-values obtained using TDT cells. a– cMean values within a column without common letter differ significantly (P < 0.05). A,BMean values within a row without common letter differ significantly (P < 0.05). Experiments were repeated independently three times. aw: water activity measured at 22°C.

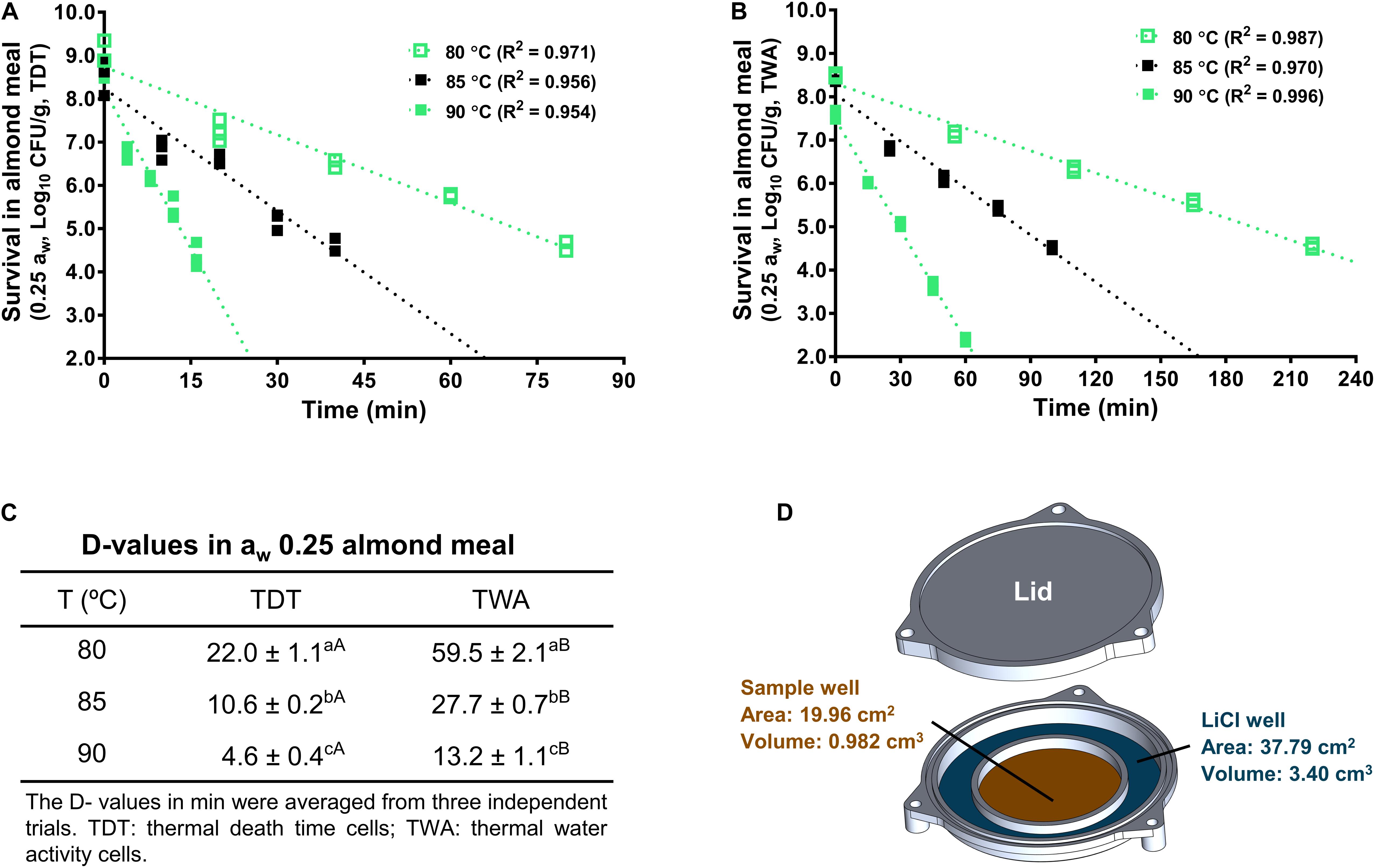

The LiCl solution has a relatively stable aw during heating treatment, which creates a stable relative humidity within TWA cell microenvironment (Figure 4D). Therefore, aw of almond meal inside TWA is stable during heating. Like TDT cells, the inactivation kinetics of L. monocytogenes in almond meal using TWA cells fitted well to a log-linear model (Figures 4A,B). Based on the trend lines of the log-linear model, D80-, D85-, and D90-values for L. monocytogenes in almond meal preconditioned to aw 0.25 were 59.5 ± 2.1, 27.7 ± 0.7, and 13.2 ± 1.1 min, respectively. At each temperature, D-value obtained from TWA cells was 2.5 times of that obtained from TDT cells (Figure 4C), suggesting that the aw at a specific treatment temperature played a critical role in inactivation of L. monocytogenes in almond meal.

Figure 4. D-values of L. monocytogenes in aw 0.25 almond meal calculated from thermal inactivation kinetic curves using both TDT and TWA cells. (A) A representative death curve using TDT cells. (B) A representative death curve using TWA cells. (C) D-value comparison between TDT and TWA cells. (D) Schematic diagram of TWA cells. a– cMean values within a column without common letter differ significantly (P < 0.05). A,BMean values within a row without common letter differ significantly (P < 0.05). Experiments were repeated independently three times. aw: water activity measured at 22°C.

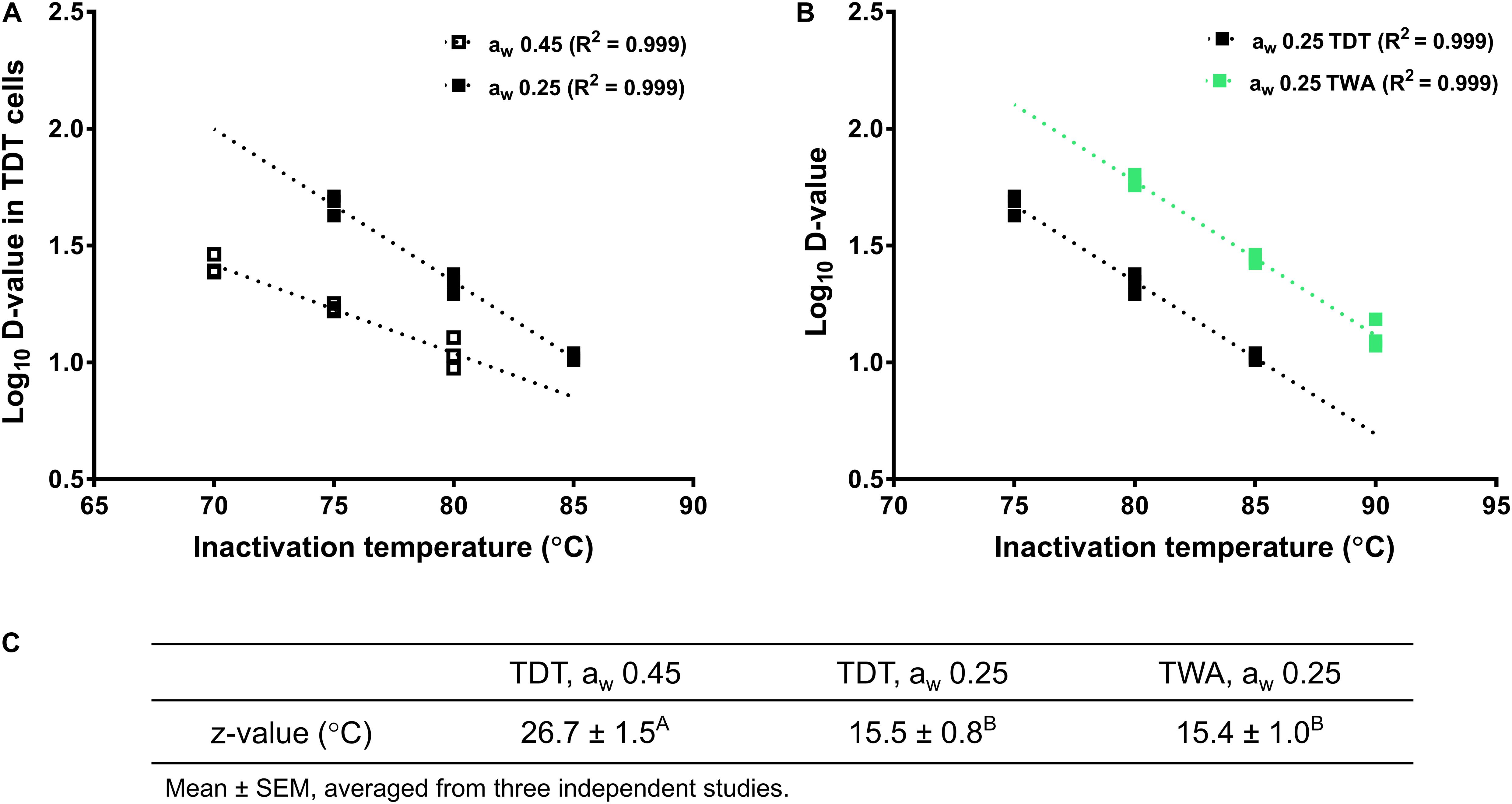

The z-value of L. monocytogenes in aw 0.25 almond meal obtained with TWA cells was 15.4 ± 1.0°C, which was not different from z-value of L. monocytogenes in aw 0.25 almond meal obtained with TDT cells. However, the z-value of L. monocytogenes in aw 0.45 almond meal obtained with TDT cells was more than 10°C higher than that in aw 0.25 almond meal (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Log D-values (decimal reduction time to achieve 90% population reduction at the selected temperature) of L. monocytogenes in almond meal at different temperatures. (A) Log D-values at aw 0.25 and 0.45 almond meal using TDT cells. (B) Log D-values at aw 0.25 almond meal using TDT and TWA cells. (C) z-values. A,BMean values within a row without common letter differ significantly (P < 0.05). The thermal inactivation tests were conducted three times independently. TDT: thermal death time cells; TWA: thermal water activity cells; aw: water activity measured at 22°C.

Discussion

It is assumed that almonds are subjected to microbial contamination during production and processing. A long survey documented an average 0.87% prevalence of Salmonella in raw almonds over more than 5 years (Danyluk et al., 2007). The microbial safety risks of almond and almond products was highlighted by Salmonella outbreaks implicated in raw almonds in Canada and the United States (CDC, 2004; Isaacs et al., 2005), as well as recent almond product recalls associated with potential L. monocytogenes contamination (FDA, 2017bFDA, 2017c; FDA, 2018FDA, 2019). However, the current thermal intervention studies in almond/almond meal have been focused on Salmonella (Du et al., 2010; Villa-Rojas et al., 2013; Limcharoenchat et al., 2019; Xu et al., 2019). As an important foodborne pathogen with high mortality, it is important to evaluate the factors that impact desiccation and thermal stability of L. monocytogenes in almond meal.

Factors Influence Desiccation Stability of L. monocytogenes in Low-Moisture Foods

Raw almonds or almond meal can be stored for more than 1 year at room, refrigerated, or frozen temperatures (Lambertini et al., 2012). L. monocytogenes can survive for months or even years in various LawF (Kenney and Beuchat, 2004; Kimber et al., 2012; Brar et al., 2015; Koseki et al., 2015; Rachon et al., 2016; Taylor et al., 2018; Tsai et al., 2019b; Ballom et al., 2020), with their survival in LawF influenced by aw, storage temperature and food composition.

Storage Temperature and Water Activity

In general, L. monocytogenes is stable in almond meal when stored at 4°C. Consistently, L. monocytogenes was very stable in almonds kernels, in-shell pistachios and pecans (Kimber et al., 2012; Brar et al., 2015) during 1-year 4°C storage. Compared to cold storage, L. monocytogenes was less stable in almond meal stored at 22°C. This is also the case for almonds kernels, in-shell pistachios (Kimber et al., 2012) and pecans (Brar et al., 2015). Given the high fat content, it is preferred to store tree nut products at cooler temperature to maintain desirable quality attributes, which might compromise the microbial safety of tree nuts.

The previous study showed that the desiccation stability of L. monocytogenes increased in wheat flour when aw decreased from 0.56 to 0.30 (Taylor et al., 2018). Concordantly, the stability of L. monocytogenes in almond meal stored at 22°C increased as aw decreased, but the increment was much smaller than that in wheat flour. The observed difference might be due to the interaction between L. monocytogenes and different food matrices. It could also be due to a different aw range. In contrast, the stability of L. monocytogenes in almond meal stored at 4°C was not influenced by aw. In support of our finding, impacts of storage atmosphere on survival of E. coli ATCC 25922 in almond meal were more dramatic as temperature increased from 4 to 24°C (Cheng and Wang, 2018).

Food Matrix

Listeria monocytogenes showed more stability in fat-rich almond meal than in protein-rich NFDM (Ballom et al., 2020) and carbohydrate-rich wheat flour (Taylor et al., 2018). The L. monocytogenes population was reduced by 0.20 and 1.69 log10 CFU/g in aw 0.25 almond meal compared to 1.75 and 2.93 log10 CFU/g reduction in aw 0.25 NFDM over 44- to 48-week storage at 4 and 22°C, respectively (Ballom et al., 2020). However, L. monocytogenes had a comparable stability in aw 0.30 wheat flour as aw 0.25 NFDM (Taylor et al., 2018; Ballom et al., 2020). Cocoa powder had the same carbohydrate contents (∼57%) (Tsai et al., 2019a) as that of wheat flour (Taylor et al., 2018), but a 5.20 log10 CFU/g reduction of L. monocytogenes was observed in aw 0.30 cocoa powder over ∼200 days storage at 22°C (Tsai et al., 2019b) in contrast to 2.52 log10 CFU/g reduction in aw 0.30 wheat flour (Taylor et al., 2018), indicating other components such as polyphenols might impact the stability of L. monocytogenes in LawF. Of note, a higher magnitude of L. monocytogenes decline was observed in almond kernels (0.71 log10 CFU/g per month), in-shell pistachios (0.86 log10 CFU/g per month) (Kimber et al., 2012) and pecans (1.17 log10 CFU/g per month) (Brar et al., 2015) during 1-year ambient storage. This might be due to different aw, relative humidity and food microstructure in addition to food matrix, given the aw/relative humidity was not controlled during storage in these studies.

Impacts of Water Activity on Thermal Resistance of L. monocytogenes in Almond Meal

The aw was recognized as a primary factor influencing bacterial thermal resistance in LawF. The thermal resistance of Salmonella in LawF is inversely related to aw (He et al., 2013; Villa-Rojas et al., 2013; Smith et al., 2016; Xu et al., 2019; Tsai et al., 2019a). The same is true for L. monocytogenes in wheat flour (Taylor et al., 2018), cocoa powder (Tsai et al., 2019b), milk powder (Ballom et al., 2020), and almond meal in the present study. The D75-value of L. monocytogenes in aw 0.25 almond meal was over two times of that in aw 0.45 almond meal.

The previous study showed that the change in aw of almond flour during heat treatment depended on its initial equilibrated aw at 22°C. The aw of almond flour with initial aw 0.25 increased as the temperature increased from 20 to 80°C, whereas the aw of almond flour with initial aw 0.45 was relatively stable between 20 and 80°C (Tadapaneni et al., 2017). To evaluate alteration of aw at treatment temperatures as a contributing factor to thermal resistance of L. monocytogenes, we further evaluated thermal stability of L. monocytogenes in aw 0.25 almond meal under constant aw using TWA cells (Tadapaneni et al., 2018). The D80- and D85-values of L. monocytogenes in aw 0.25 almond meal obtained from TWA cells were approximately 2.6 to 2.7 times of those determined using TDT cells. In support of our findings, D80-value of Salmonella in aw 0.25 blanched almond flour or wheat flour obtained from TWA cells was approximately 2 or 4 times of that obtained using TDT cells (Xu et al., 2019). These data highlight that aw at treatment temperature is an important factor affecting bacterial thermal resistance, which provide insights to the different thermal resistance of L. monocytogenes in different LawF.

Impacts of Food Matrix on Thermal Resistance of L. monocytogenes in Low-Moisture Foods

While aw is an important factor in determining thermal death–time curves, food matrices have a complex relationship with bacterial survival in LawF during thermal treatments. Previous studies showed that, in general, the thermal resistance of L. monocytogenes in NFDM (Ballom et al., 2020) were higher than that in wheat flour (Taylor et al., 2018) or cocoa powder (Tsai et al., 2019b) at their respective aw and inactivation temperatures. D75- and D80-values at aw 0.45 NFDM, wheat flour, and cocoa powder were 9.4/4.3, 7.7/3.1, and 3.4/1.8 min, respectively. This study showed that the D75- and D80-values of L. monocytogenes in almond meal preconditioned to aw 0.25/0.45 obtained in TDT cells were higher than the respective D-values in aw 0.25/0.45 NFDM (47.6/17.2 and 22.0/11.0 versus 33.5/9.4 and 14.6/4.3 min; Ballom et al., 2020). Data indicated that L. monocytogenes is most resistant in fat-rich food matrix and least resistant in antimicrobial-rich matrices such as cocoa powder during thermal treatment. The exact mechanism for the observed different thermal resistance is unknown, which could result from unique aw alteration at the treatment temperature, and/or complicated interaction between food components and bacteria, warranting future research.

Conclusion

Listeria monocytogenes was stable in almond meal; there was approximately 0.20/0.17 and 1.69/2.14 log10 CFU/g reduction in aw 0.25/0.45 almond meal over 44- to 48-week storage at 4 and 22°C, respectively. Thermal resistance of L. monocytogenes in almond meal was inversely related to the aw of samples. The aw of samples at treatment temperature plays an important role in thermal stability of L. monocytogenes in almond meal; the D80-, D85-, and D90-values of L. monocytogenes obtained by TWA cells were 59.5, 27.7, and 13.2 min, respectively, compared to 22.0, 10.6, and 4.6 min from TDT cells. Data herein contribute to our understanding on the survival of L. monocytogenes on tree nuts as well as other LawF during desiccation and thermal processing and provide guidelines for developing practical strategies to control L. monocytogenes in almond meal and other LawF.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author Contributions

MZ designed the experiment, analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript. XSo performed the experiment. XSh assisted the sample analyses. JT revised the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This work was supported by the ILSI North America Food Microbiology Committee (ILSI 20160225) and USDA National Institute of Food and Agriculture (NIFA) award 2015-68003-23415. The funding agents had no role in the design, analysis, interpretation, or presentation of the data and results.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Almond Board of California for their in-kind contributions of almond meal and Mr. Mike Taylor for his criticial proofread of the manuscript.

References

Ballom, K. F., Tsai, H. C., Taylor, M., Tang, J., and Zhu, M. J. (2020). Stability of Listeria monocytogenes in non-fat dry milk powder during isothermal treatment and storage. Food Microbiol. 87:103376. doi: 10.1016/j.fm.2019.103376

Brar, P. K., Proano, L. G., Friedrich, L. M., Harris, L. J., and Danyluk, M. D. (2015). Survival of Salmonella, Escherichia coli O157:H7, and Listeria monocytogenes on raw peanut and pecan kernels stored at -24, 4, and 22 degrees C. J. Food Prot. 78, 323–332. doi: 10.4315/0362-028x.jfp-14-327

Buchanan, R. L., Gorris, L. G. M., Hayman, M. M., Jackson, T. C., and Whiting, R. C. (2017). A review of Listeria monocytogenes : an update on outbreaks, virulence, dose-response, ecology, and risk assessments. Food Control 75, 1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.foodcont.2016.12.016

CDC (1999). Update: multistate outbreak of listeriosis–United States, 1998-1999. Morb. Mortal Wkly. Rep. 47, 1117–1118.

CDC (2000). Multistate outbreak of listeriosis–United States, 2000. Morb. Mortal Wkly. Rep. 49, 1129–1130.

CDC (2004). Outbreak of Salmonella serotype Enteritidis infections associated with raw almonds — United States and Canada, 2003–2004. Morb. Mortal Wkly. Rep. 53, 484–487.

CDC (2009). Multistate outbreak of Salmonella infections associated with peanut butter and peanut butter–containing products — United States, 2008–2009. Morb. Mortal Wkly. Rep. 58, 85–90.

CDC (2011). Multistate Outbreak of Listeriosis Linked to Whole Cantaloupes from Jensen Farms, Colorado. Atlanta: CDC.

CDC (2013). National Listeria Surveillance Annual Summary, 2013. Atlanta: US Department of Health and Human Services, CDC, 2015.

CDC (2015). Multistate Outbreak of Listeriosis Linked to Commercially Produced, Prepackaged Caramel Apples Made From Bidart Bros. Atlanta: CDC.

Cheng, T., and Wang, S. J. (2018). Influence of storage temperature/time and atmosphere on survival and thermal inactivation of Escherichia coli ATCC 25922 inoculated to almond powder. Food Control 86, 350–358. doi: 10.1016/j.foodcont.2017.11.029

Chung, H. J., Birla, S. L., and Tang, J. (2008). Performance evaluation of aluminum test cell designed for determining the heat resistance of bacterial spores in foods. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 41, 1351–1359. doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2007.08.024

Danyluk, M. D., Jones, T. M., Abd, S. J., Schlitt-Dittrich, F., Jacobs, M., and Harris, L. J. (2007). Prevalence and amounts of Salmonella found on raw California almonds. J. Food Prot. 70, 820–827. doi: 10.4315/0362-028x-70.4.820

Du, W. X., Abd, S. J., McCarthy, K. L., and Harris, L. J. (2010). Reduction of Salmonella on inoculated almonds exposed to hot oil. J. Food Prot. 73, 1238–1246. doi: 10.4315/0362-028x-73.7.1238

FDA (2017a). FDA Investigates Listeria Outbreak Linked to Soft Cheese Produced by Vulto Creamery. Silver Spring, MD: FDA.

FDA (2017b). Gomacro Recalls Limited Number of Macrobars and Thrive Bars Because of Possible Health Risk. Silver Spring, MD: FDA.

FDA (2017c). Recall Expansion in New Jersey on Fewer than 650 Units of Ava’s Brand Organic Roasted Unsalted Cashews and Organic Roasted Unsalted Almonds. Silver Spring, MD: FDA.

FDA (2018). Inspired Organics Issues Voluntary Recall of Organic Nut & Seed Butters Due to Potential Health Risk. Silver Spring, MD: FDA.

FDA (2019). Oskri Organics Corporation Recalls all Nut Butters Because of Possible health risk. Silver Spring, MD: FDA.

Gottlieb, S. L., Newbern, E. C., Griffin, P. M., Graves, L. M., Hoekstra, R. M., Baker, N. L., et al. (2006). Multistate outbreak of Listeriosis linked to turkey deli meat and subsequent changes in US regulatory policy. Clin. Infect. Dis. 42, 29–36. doi: 10.1086/498113

He, Y., Li, Y., Salazar, J. K., Yang, J., Tortorello, M. L., and Zhang, W. (2013). Increased water activity reduces the thermal resistance of Salmonella enterica in peanut butter. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 79, 4763–4767. doi: 10.1128/aem.01028-13

Isaacs, S., Aramini, J., Ciebin, B., Farrar, J. A., Ahmed, R., Middleton, D., et al. (2005). An international outbreak of salmonellosis associated with raw almonds contaminated with a rare phage type of Salmonella Enteritidis. J. Food Prot. 68, 191–198. doi: 10.4315/0362-028x-68.1.191

Jenkins, D. J., Kendall, C. W., Josse, A. R., Salvatore, S., Brighenti, F., Augustin, L. S., et al. (2006). Almonds decrease postprandial glycemia, insulinemia, and oxidative damage in healthy individuals. J. Nutr. 136, 2987–2992. doi: 10.1093/jn/136.12.2987

Kenney, S. J., and Beuchat, L. R. (2004). Survival, growth, and thermal resistance of Listeria monocytogenes in products containing peanut and chocolate. J. Food Prot. 67, 2205–2211. doi: 10.4315/0362-028x-67.10.2205

Kimber, M. A., Kaur, H., Wang, L., Danyluk, M. D., and Harris, L. J. (2012). Survival of Salmonella, Escherichia coli O157:H7, and Listeria monocytogenes on inoculated almonds and pistachios stored at -19, 4, and 24 degrees C. J. Food Prot. 75, 1394–1403. doi: 10.4315/0362-028x.jfp-12-023

Koseki, S., Nakamura, N., and Shiina, T. (2015). Comparison of desiccation tolerance among Listeria monocytogenes, Escherichia coli O157:H7, Salmonella enterica, and Cronobacter sakazakii in powdered infant formula. J. Food Prot. 78, 104–110. doi: 10.4315/0362-028x.jfp-14-249

Lambertini, E., Kaur, H., Danyluk, M. D., Schaffner, D. W., Winter, C. K., and Harris, L. J. (2012). Risk of salmonellosis from consumption of almonds in the North American market. Food Res. Int. 45, 1166–1174. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2011.05.039

Li, S. C., Liu, Y. H., Liu, J. F., Chang, W. H., Chen, C. M., and Chen, C. Y. (2011). Almond consumption improved glycemic control and lipid profiles in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Metabolism 60, 474–479. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2010.04.009

Limcharoenchat, P., James, M. K., and Marks, B. P. (2019). Survival and thermal resistance of Salmonella Enteritidis PT 30 on almonds after long-term storage. J. Food Prot. 82, 194–199. doi: 10.4315/0362-028x.jfp-18-152

Losio, M. N., Dalzini, E., Pavoni, E., Merigo, D., Finazzi, G., and Daminelli, P. (2017). A survey study on safety and microbial quality of “gluten-free” products made in Italian pasta factories. Food Control 73, 316–322. doi: 10.1016/j.foodcont.2016.08.020

Mena, C., Almeida, G., Carneiro, L., Teixeira, P., Hogg, T., and Gibbs, P. A. (2004). Incidence of Listeria monocytogenes in different food products commercialized in Portugal. Food Microbiol. 21, 213–216. doi: 10.1016/s0740-0020(03)00057-1

Peleg, M. (2006). Advanced Quantitative Microbiology for Foods and Biosystems: Models for Predicting Growth and Inactivation. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press.

Perez, A., and Pollack, S. (2005). Fruit and Tree Nuts Outlook: Commodity Highlight: Almond. Available online at: https://www.ers.usda.gov/webdocs/publications/37046/32390_fts353.pdf?v=0 (accessed June 16, 2020).

Rachon, G., Penaloza, W., and Gibbs, P. A. (2016). Inactivation of Salmonella, Listeria monocytogenes and Enterococcus faecium NRRL B-2354 in a selection of low moisture foods. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 231, 16–25. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2016.04.022

Sheng, L., Hanrahan, I., Sun, X., Taylor, M. H., Mendoza, M., and Zhu, M. J. (2018). Survival of Listeria innocua on Fuji apples under commercial cold storage with or without low dose continuous ozone gaseous. Food Microbiol. 76, 21–28. doi: 10.1016/j.fm.2018.04.006

Sheng, L., Shen, X., Benedict, C., Su, Y., Tsai, H. C., Schacht, E., et al. (2019). Microbial safety of dairy manure fertilizer application in raspberry production. Front. Microbiol. 10:2276. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2019.02276

Smith, D. F., Hildebrandt, I. M., Casulli, K. E., Dolan, K. D., and Marks, B. P. (2016). Modeling the effect of temperature and water activity on the thermal resistance of Salmonella Enteritidis PT 30 in wheat flour. J. Food Prot. 79, 2058–2065. doi: 10.4315/0362-028x.jfp-16-155

Syamaladevi, R. M., Tadapaneni, R. K., Xu, J., Villa-Rojas, R., Tang, J. M., Carter, B., et al. (2016). Water activity change at elevated temperatures and thermal resistance of Salmonella in all purpose wheat flour and peanut butter. Food Res. Int. 81, 163–170. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2016.01.008

Tadapaneni, R. K., Xu, J., Yang, R., and Tang, J. M. (2018). Improving design of thermal water activity cell to study thermal resistance of Salmonella in low-moisture foods. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 92, 371–379. doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2018.02.046

Tadapaneni, R. K., Yang, R., Carter, B., and Tang, J. (2017). A new method to determine the water activity and the net isosteric heats of sorption for low moisture foods at elevated temperatures. Food Res. Int. 102, 203–212. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2017.09.070

Taylor, M. H., Tsai, H. C., Rasco, B., Tang, J. M., and Zhu, M. J. (2018). Stability of Listeria monocytogenes in wheat flour storage and isothermal treatment. Food Control 91, 434–439. doi: 10.1016/j.foodcont.2018.04.008

Todd, E. C. D. (2011). The international risk governance council framework and its application to Listeria monocytogenes in soft cheese made from unpasteurised milk. Food Control 22, 1513–1524. doi: 10.1016/j.foodcont.2010.07.020

Tsai, H. C., Ballom, K. F., Xia, S., Tang, J., Marks, B. P., and Zhu, M. J. (2019a). Evaluation of Enterococcus faecium NRRL B-2354 as a surrogate for Salmonella during cocoa powder thermal processing. Food Microbiol. 82, 135–141. doi: 10.1016/j.fm.2019.01.005

Tsai, H. C., Taylor, M. H., Song, X., Sheng, L., Tang, J., and Zhu, M. J. (2019b). Thermal resistance of Listeria monocytogenes in natural unsweetened cocoa powder under different water activity. Food Control 102, 22–28. doi: 10.1016/j.foodcont.2019.03.006

Villa-Rojas, R., Tang, J., Wang, S., Gao, M., Kang, D. H., Mah, J. H., et al. (2013). Thermal inactivation of Salmonella Enteritidis PT 30 in almond kernels as influenced by water activity. J. Food Prot. 76, 26–32. doi: 10.4315/0362-028x.jfp-11-509

Keywords: Listeria monocytogenes, almond meal, water activity, thermal resistance, storage

Citation: Zhu M, Song X, Shen X and Tang J (2020) Listeria monocytogenes in Almond Meal: Desiccation Stability and Isothermal Inactivation. Front. Microbiol. 11:1689. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2020.01689

Received: 12 May 2020; Accepted: 29 June 2020;

Published: 07 August 2020.

Edited by:

Jean-christophe Augustin, INRA École Nationale Vétérinaire d’Alfort (ENVA), FranceReviewed by:

Krzysztof Skowron, Nicolaus Copernicus University in Toruń, PolandFrancisco Diez-Gonzalez, University of Georgia, United States

Copyright © 2020 Zhu, Song, Shen and Tang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Meijun Zhu, bWVpanVuLnpodUB3c3UuZWR1

Meijun Zhu

Meijun Zhu Xia Song

Xia Song Xiaoye Shen

Xiaoye Shen Juming Tang2

Juming Tang2