- 1Beijing Advanced Innovation Center for Food Nutrition and Human Health, College of Food Science and Nutritional Engineering, China Agricultural University, Beijing, China

- 2Key Laboratory of Fruit and Vegetable Processing, Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs, Beijing, China

The viable but non-culturable (VBNC) state, in which bacteria fail to grow on routine culture media but are actually alive, has been widely recognized as a strategy adopted by bacteria to cope with stressful environments. However, little is known regarding the molecular mechanism of VBNC formation. Here, we aimed to elucidate the specific roles of cell division regulatory proteins and the cell growth rate during VBNC Escherichia coli O157:H7 formation. We have previously found that expression of dicC is reduced by 20.08-fold in VBNC E. coli O157:H7 compared to non-VBNC cells. Little is known about DicC except that it, along with DicA, appears to act as a regulator of cell division by regulating expression of the cell division inhibitor DicB. First, our results showed that the VBNC cell number increased in the ΔdicC mutant as well as the DicA-overexpressing strain but decreased in the DicC-overexpressing strain induced by high-pressure carbon dioxide, acid, and H2O2. Furthermore, the growth rates of both the DicA-overexpressing strain and the ΔdicC mutant were higher than that of the control strain, while DicC-overexpressing strain grew significantly more slowly than the vector strain. The level of the dicB gene, regulated by dicA and dicC and inhibiting cell division, was increased in the DicC-overexpressing strain and decreased in the ΔdicC mutant and DicA-overexpressing strain, which was consistent with the growth phenotypes. In addition, the dwarfing cell morphology of the ΔdicC mutant and DicA-overexpressing strain were observed by SEM and TEM. Taken together, our study demonstrates that DicC negatively regulates the formation of the VBNC state, and DicA enhances the ability of cells to enter the VBNC state. Besides, the cell growth rate and dwarfing cell morphology may be correlated with the formation of the VBNC state.

Introduction

The viable but non-culturable (VBNC) state, a unique biological state, is a positive response strategy used by a number of bacteria to cope with different adverse environments (Colwell, 2000; Oliver, 2005b; Orruno et al., 2017). Xu et al. (1982) found that Escherichia coli and Vibrio cholerae from seawater could not be cultured on their routine medium but possessed metabolic activity. Based on this finding, they proposed the concept of the VBNC state, in which bacteria cannot grow on the routine culture medium but are actually alive. Subsequently, they further proved that these bacteria can recover from the VBNC state and become culturable again when the environment is suitable, which is termed resuscitation (Roszak et al., 1984). A growing number of VBNC microorganisms have been found in various environments, posing a significant risk to public health (Li et al., 2014; Zhao et al., 2017). To date, approximately 110 species of microorganisms, including bacteria and fungi, have been reported to enter the VBNC state when exposed to diverse forms of stress, and these species can be divided into three categories based on their features and functions, namely, microbes associated with food and medical safety, environmental applications and agricultural diseases (Ramamurthy et al., 2014; Ayrapetyan and Oliver, 2016; Ayrapetyan et al., 2018). Thus, VBNC microorganisms are widely distributed in nature, representing a strategy used by microorganisms to survive in different adverse environments.

A range of stressful environmental conditions during food processing and preservation can also induce the entry of many foodborne pathogens into VBNC state, for instance, high-temperature sterilization of milk, chlorination of wastewater, extreme temperatures, ultraviolet (UV) radiation, ultrasound, irradiation, drying, pulsed electric field (PEF), high-pressure carbon dioxide (HPCD) and high-pressure stress, as well as the addition of preservatives and disinfectants (Oliver, 2005a; Zhao et al., 2013, 2017; Zhang et al., 2015). Therefore, the VBNC bacteria should not be neglected. In addition, a series of morphological and physiological changes occur when microorganisms enter the VBNC state. The morphological changes affect mainly cell size, cell wall composition and the cell membrane (Signoretto, 2000; Signoretto et al., 2002; Day and Oliver, 2004; Oliver, 2010; Chen et al., 2018). The physiological features of VBNC cells are mainly characterized by decreased metabolic activity, slow absorption of nutrients, potential pathogenicity, decreased gene expression and protein translation capacity, and increased resistance to antibiotics (Du et al., 2006; Li et al., 2014; Lin et al., 2017).

Escherichia coli is one of the most widely studied bacteria in VBNC research, and there are many studies on the conditions associated with induction and recovery of the VBNC state of this species as well as on the formation mechanisms (Ding et al., 2016). In this study, E. coli O157:H7 was adopted as the target strain to study the molecular mechanism underlying the formation of the VBNC state. E. coli O157:H7, the major pathogenic serotype of enterohemorrhagic E. coli, can cause diarrhea, hemorrhagic enteritis, and two serious complications, namely, hemolytic uremic syndrome (HUS) and thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura, and produce mortality (Karmali et al., 1985; Nataro and Kaper, 1998). Since it was first discovered in 1983, E. coli O157:H7 has caused a worldwide epidemic. E. coli O157:H7 can enter the VBNC state under a variety of conditions, posing risks to food safety and human health. For example, Liu et al. (2010) showed that the stx gene was continuously expressed in VBNC E. coli O157:H7, which enabled the production of shiga toxins. In addition, serious food poisoning incidents caused by salted salmon roe contaminated with VBNC enterohemorrhagic E. coli O157:H7 were reported in Japan (Makino et al., 2000). Recently, VBNC E. coli O157:H7 in the phyllosphere of lettuce was also regarded as a food safety risk factor (Dinu and Bach, 2011). Therefore, elucidating the formation mechanism of VBNC E. coli O157:H7 will lay a theoretical foundation for preventing the outbreak of foodborne diseases caused by this pathogen.

Although the molecular mechanisms underlying the formation of the VBNC state of E. coli is not fully understood, several genes or proteins have been found to play an integral role in this process. A transcriptional regulator, RpoS, which regulates gene expression and enables bacteria to survive under various forms of environmental stress, was demonstrated to delay the entry of E. coli into the VBNC state (Boaretti et al., 2003). Outer membrane proteins (OMPs) are essential for the exchange of substances and responses to environmental stimuli in bacterial cells. Therefore, changes in the expression of OMPs, including OmpW and EnvZ, have a major impact on the survival of bacteria under stressful conditions, which was thought to be involved in the formation of VBNC E. coli (Asakura et al., 2008). In addition, ppGpp, regulated by the SpoT and RelA proteins, may be an inducer of the VBNC state (Chatterji et al., 1998). E. coli cells lacking ppGpp are less likely to enter the VBNC state than those that harbor this substance (Boaretti et al., 2003).

The formation of the VBNC state is closely related to cell culturability, but to date, few studies have reported the correlation between cell division and the formation of the VBNC state. Previously, our group performed a transcriptomic analysis of the HPCD-induced VBNC state of E. coli O157:H7 by RNA sequencing. The results showed that the expression of the dicC gene was downregulated by 20.08-fold in VBNC cells (Zhao et al., 2016). Nevertheless, how DicC regulates the formation of VBNC cells induced by HPCD remains unclear. In this study, the specific roles of cell division regulatory proteins (DicA and DicC) and the cell growth rate in VBNC E. coli O157:H7 formation were explored.

Materials and Methods

Bacterial Strains and Culture Conditions

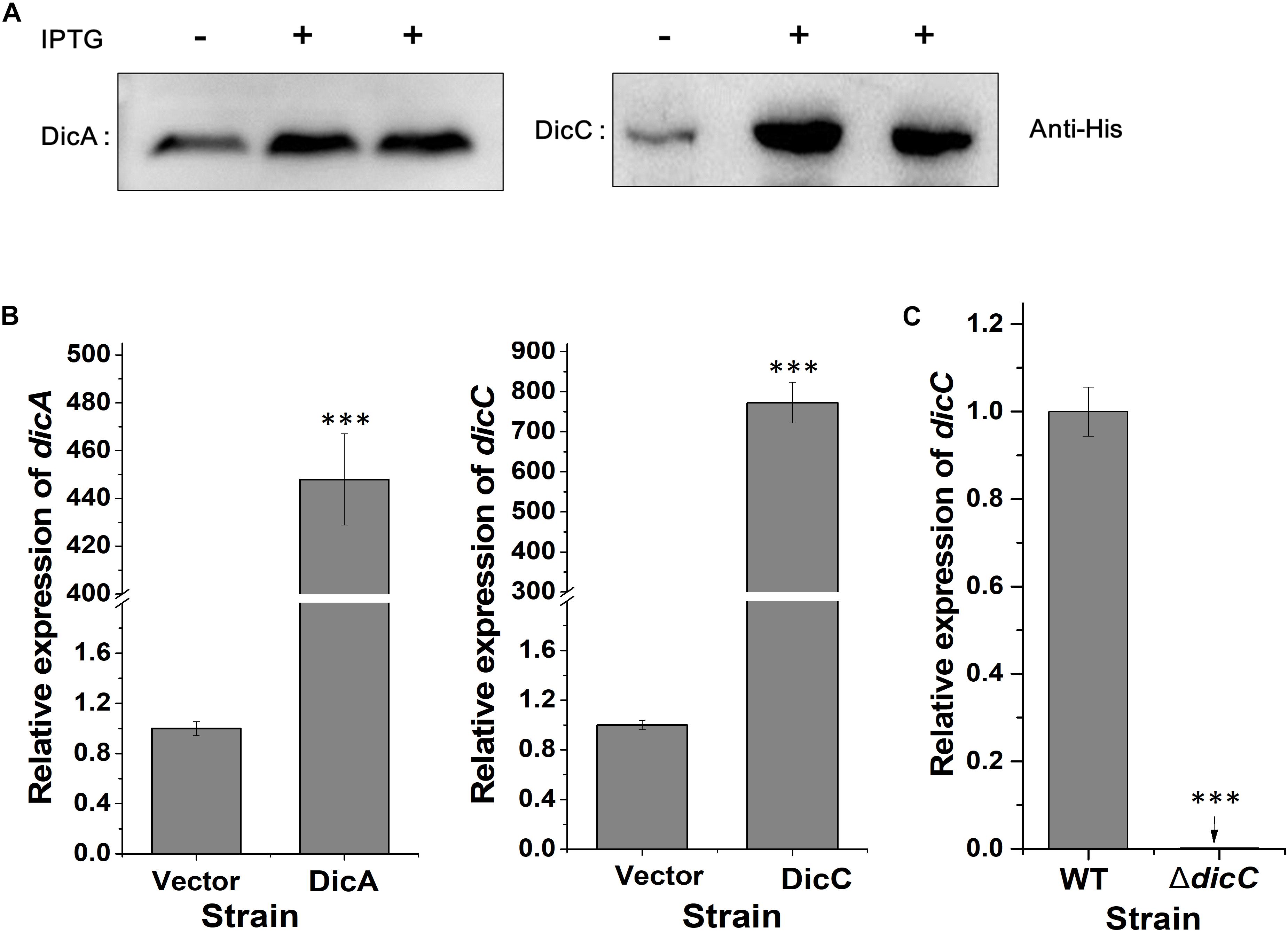

The bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are summarized in Table 1. E. coli O157:H7 NCTC 12900, a stx-negative strain, was used in this study and was obtained from the National Culture Type Collection (Colindale, London, United Kingdom). E. coli O157:H7 was cultured overnight in Luria-Bertani (LB) broth at 37°C (10 g/L tryptone, 5 g/L yeast extract, 10 g/L NaCl). The overnight culture was transferred to fresh LB broth at a dilution of 1:100 and inoculated with shaking (200 rpm) at 37°C to the exponential phase (OD600 = 0.8). LB agar was obtained by adding 1.5% (w/v) agar. When culturing the resistant strains or inducing protein expression, antibiotics or inducers were added into the culture as follows: ampicillin (100 μg/mL), kanamycin (25 μg/mL), arabinose (0.2% [w/v]), IPTG (1 mM).

Construction of Deletion Mutants and Complementary Strains

For the construction of the dicC deletion mutant, the ORF of DicC was replaced with a kanamycin resistance (Kmr) gene cassette. The cassette was amplified from the pKD4 plasmid (obtained from the E. coli Genetic Stock Center, CGSC) by PCR using primer pairs containing an E. coli O157:H7 dicC-specific sequence (the primer sequences are listed in Table 2). Then, the pCP20 plasmid (Table 1) (Datsenko and Wanner, 2000), which can recognize the FRT sequence, was used to remove the Kmr cassette. Since the pCP20 plasmid was temperature-sensitive, it was removed by incubation at 42°C for 12 h. To construct the complemented strain of the ΔdicC mutant, the dicC gene amplified from the genomic DNA of wild-type (WT) strains was purified and cloned into pTrc-His A with the appropriate restriction sites for BamHI and HindIII (New England Biolabs, Inc.) to form the pTHA-DicC plasmid, which was then transformed into the ΔdicC strain.

Recombinant Bacterial Strains Harboring Overexpression Plasmids for DicA and DicC

The full-length dicC and dicA genes were amplified by PCR with E. coli O157:H7 genomic DNA as the template using primer pairs (DicC-BamHI and DicC-HindIII for dicC; DicA-BamHI and DicA-HindIII for dicA) with restriction enzyme linkers (BamHI and HindIII) (Table 2). The amplicons were digested with BamHI and HindIII and then ligated to the vector pTrc-His A digested by the same enzymes and transformed into E. coli DH5α. pTHA-DicA and pTHA-DicC were harvested from the E. coli DH5α cells and transformed into the WT E. coli O157:H7 cells, which were further selected based on their kanamycin resistance. The full-length sequences of the dicA and dicC genes in the recombinant strains were verified by PCR and sequencing.

Induction and Quantification of VBNC E. coli Cells

According to the experimental procedure previously described by Zhao et al. (2013), VBNC E. coli O157:H7 of the WT strain, mutant strains and recombinant strains were induced by HPCD at 5 MPa at 25°C for 40 min. These strains were also induced into the VBNC state under acid or oxidation treatment. The condition of acid induction was treatment with pH 2.5 sodium chloride (0.85% w/v) for 3 h, and the condition of oxidation induction was 50 mM H2O2 treatment for 6 h. The number of VBNC cells was determined by staining with the LIVE/DEAD BacLight Bacterial Viability Kit (Molecular Probes, Inc., Eugene, OR, United States) in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions and a previously published reference (Zhao et al., 2013), followed by analysis with a FACSCalibur flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson Immunocytometry Systems, San Jose, CA, United States). Furthermore, a Declipse C1 confocal laser scanning microscope (CLSM) was used for observation of stained cells. In addition, to determine the culturability of the cells treated with HPCD, the cells were pour-plated on LB agar in duplicate. When the culturable cell concentration was below 0.1 CFU/mL, the cells were considered to be in the VBNC state.

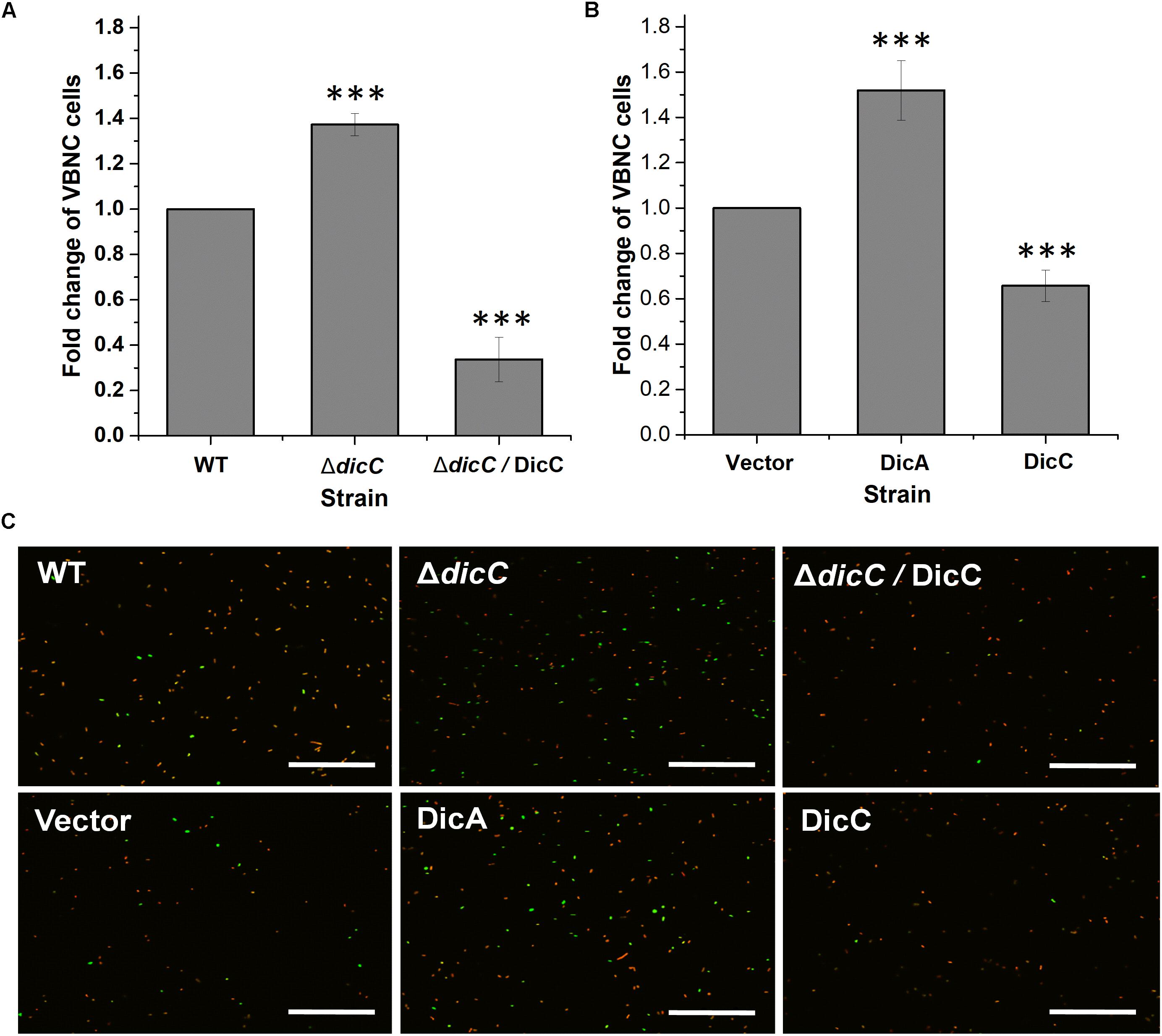

Analysis of dicA, dicB, and dicC Gene Expression

The expression of the dicA, dicB, and dicC genes in the WT, recombinant and mutant strains was confirmed by real-time quantitative reverse transcription PCR (RT-qPCR). Briefly, cells were lysed, and RNA samples were extracted with the RNAprep Pure Cell/Bacteria Kit (TIANGEN BIOTECH, Beijing, China) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. RNA samples were reverse transcribed using the iScriptTM gDNA Clear cDNA Synthesis Kit (Bio-Rad, United States) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Primers (Table 2) were designed using Beacon Designer 7.0 software (Premier Biosoft International, Palo Alto, CA, United States), and 16S rRNA was used as the reference gene. Real-time PCR was performed using the CFX ConnectTM Real-Time PCR Detection System (Bio-Rad, United States) with ssoAdvancedTM SYBR® Green Supermix (Bio-Rad, United States). The relative expression of the genes was calculated using the 2–Δ Δ Ct method (Livak and Schmittgen, 2001). Gene expression analyses were conducted in triplicate in at least two independent experiments.

Total Protein Extraction and Western Blotting

The total proteins from the DicC- and DicA-overexpressing strains grown in LB broth at 37°C were extracted by suspending cells in SDS buffer [100 mM Tris-HCl (pH 6.8), 4% SDS, 20% glycerol, 0.2% bromophenol blue, 5% β-mercaptoethanol] and boiling for 10 min. The proteins were separated on 15% SDS-PAGE gels and then transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes. The membranes were blocked in TBST (Tris-buffered saline, 0.5% Tween-20) with 5% defatted milk, followed by incubation with primary anti-His antibody diluted 1:5,000 (GenScript Biotech, Corp., China) in TBST for 1 h at 37°C. The membranes were washed with TBST three times after incubation. Then, incubation with a horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-linked goat anti-rabbit secondary antibody (Bio-Rad, United States) diluted 1:3,000 in TBST was conducted at 37°C for 45 min. The bands of the target proteins in the membranes were detected by using an Amersham Imager 600 (GE Healthcare UK Ltd., Buckinghamshire, United Kingdom).

Morphological Observation of the ΔdicC Mutant and Recombinant Strains

The morphology of the WT E. coli O157:H7 cells, ΔdicC mutants and recombinant strains was observed using scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and transmission electron microscopy (TEM) in accordance with the procedures described previously (Zhao et al., 2013). All the strains were grown to exponential phase before sample collection for SEM and TEM. For the TEM assay, the bacterial cells were examined on a JEM-1230 TEM instrument (JEOL Japan Electronics, Co., Ltd., Japan) at 80 kV at the Center of Biomedical Analysis, Tsinghua University (Beijing, China). For the SEM assay, observation and photomicrography were performed with a Hitachi S-3400 N SEM instrument (Hitachi Instruments, Inc., Japan) at the Center of Biomedical Analysis, Tsinghua University Center (Beijing, China). Data were recorded for at least six fields of view per strain. Figures in the results represent typical observations in each field. SEM images were used for the measurement of cell length through Image J 1.8.0 (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, United States). For each strain, cell length data were recorded from six fields of view, and at least 300 intact cells were measured.

Statistical Analysis

Graphs were generated using Origin 9.2 software (Origin Lab Corporation, Northampton, MA, United States). Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed by IBM SPSS Statistics 20.0 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, United States), and p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant for all assays.

Results

Construction of the ΔdicC Mutant Strain and DicA/DicC-Overexpressing Strains

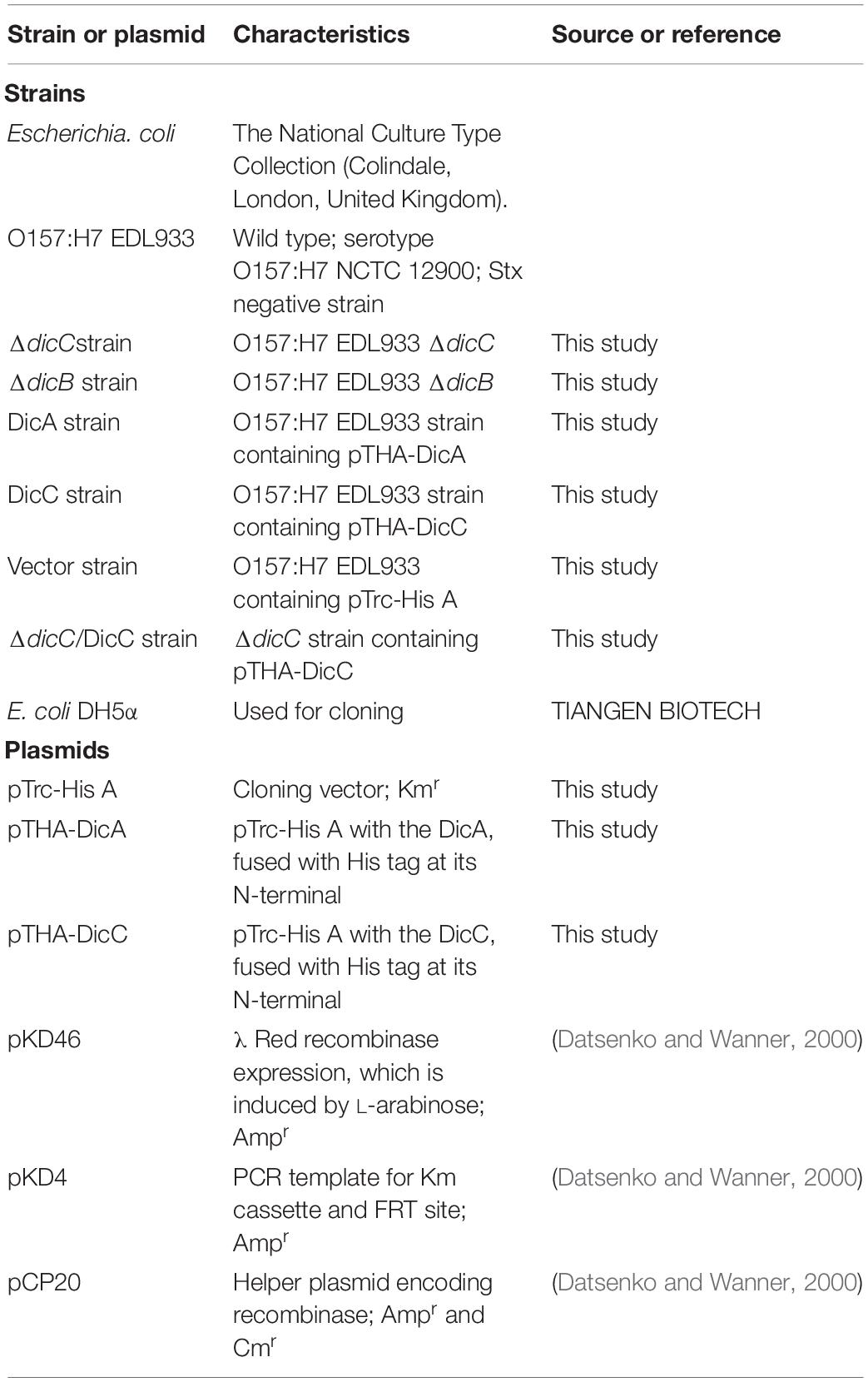

Transcriptomic data from a previous study showed that the expression of the dicC gene was downregulated by 20.08-fold in VBNC E. coli O157:H7 cells induced by HPCD (Zhao et al., 2016). Here, to investigate whether deletion or overexpression of the dicC gene affects the population of HPCD-generated VBNC cells, a ΔdicC mutant strain and a DicC-overexpressing strain harboring the pTHA-DicC vector (DicC strain) were constructed. The DicC protein accumulation induced by IPTG in the DicC strain was verified by western blot analysis (Figure 1A). Compared with the vector strain transformed with the empty vector, the expression level of dicC increased dramatically in the DicC strain (Figure 1B). The ΔdicC mutant strain was obtained by homologous recombination, which was verified by detecting the expression level of dicC with qPCR (Figure 1C). In previous studies, it was found that dicA and dicC in bacteria simultaneously participated in the regulation of cell division (Béjar et al., 1986). Therefore, we also constructed a DicA-overexpressing recombinant strain (DicA strain). Compared with the vector strain, the mRNA and the protein levels of DicA strain were also significantly increased in the DicA strain (Figures 1A,B).

Figure 1. Construction of the DicA- and DicC-overexpressing and ΔdicC mutant strains. (A) Protein expression of DicA and DicC in recombinant strains induced by IPTG was confirmed by western blot analysis. (B) Detection of the dicA and dicC gene expression levels in the DicA and DicC recombinant strains by qPCR. (C) Detection of dicC expression in the ΔdicC mutant strain by qPCR. Error bars show the standard errors of the means. Significance was calculated by the t-test (∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001).

Effects of DicC and DicA on the Formation of VBNC E. coli O157:H7 Induced by HPCD

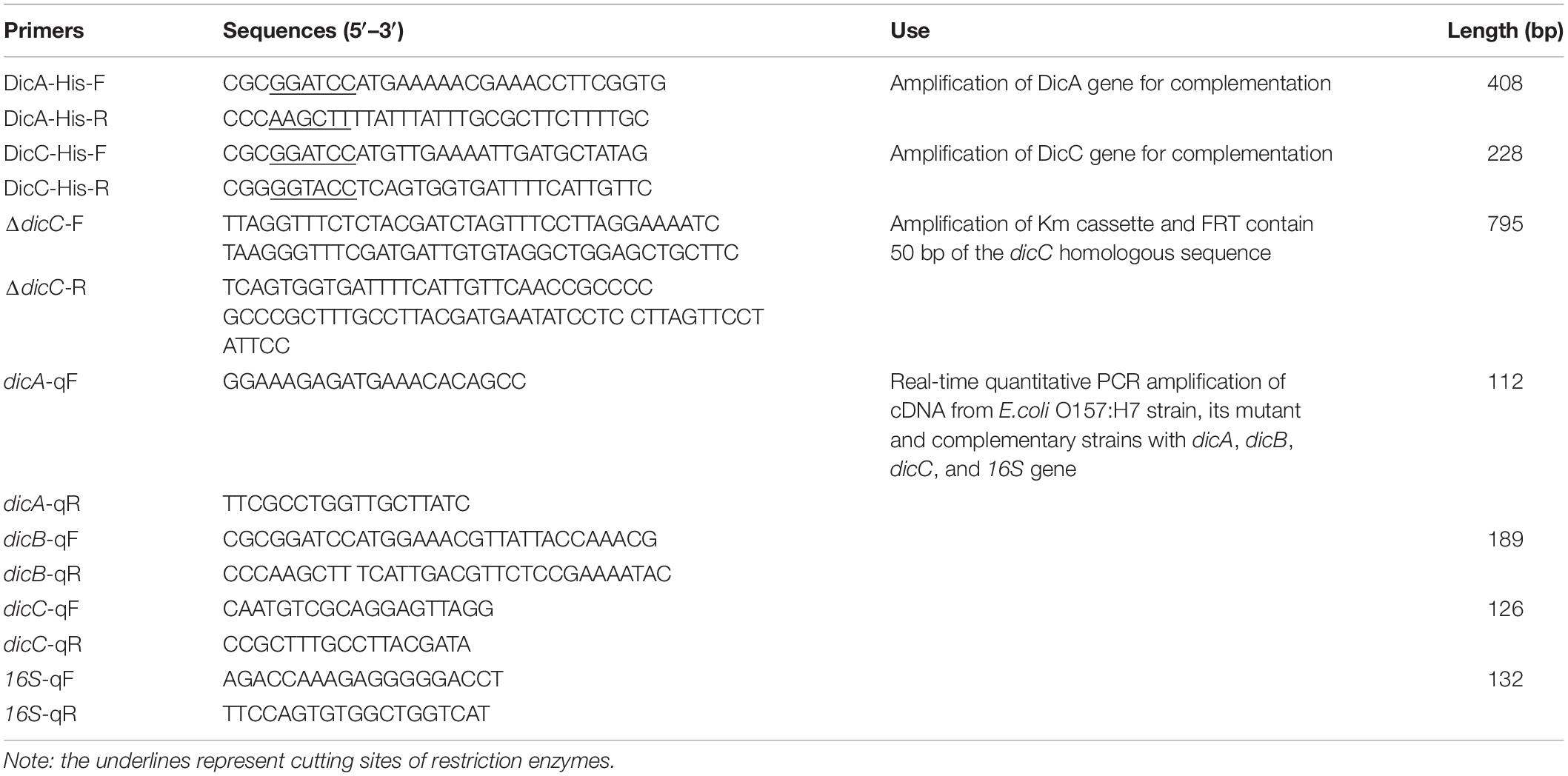

Our previous study found that HPCD could induce the entry of E. coli O157:H7 into the VBNC state (Zhao et al., 2013). The number of VBNC cells of the WT, ΔdicC mutant and DicC complementary strains (ΔdicC/DicC strain) as well as the vector, DicC and DicA strains induced by HPCD were detected using the LIVE/DEAD BacLight Bacterial Viability Kit followed by flow cytometry analysis. The results showed that compared with the WT strain, a larger number of ΔdicC mutant strain cells entered the VBNC state, while fewer VBNC cells were found in the ΔdicC/DicC strain (Figure 2A). Meanwhile, compared to the vector strain, the number of VBNC cells of the DicC strain decreased considerably upon HPCD induction (Figure 2B), which was consistent with our previous results (Zhao et al., 2016). These results suggested that DicC can negatively regulate the formation of VBNC cells induced by HPCD. Interestingly, we found that the number of VBNC cells formed in the DicA strain was higher than that in the vector strain (Figure 2B), which suggested that the DicA protein had the opposite effect on the regulation of the VBNC state, that is, DicA promoted the formation of VBNC cells. In addition, the number of VBNC cells was also observed directly by fluorescence confocal microscopy. The number of VBNC cells (green cells) in the DicC strain was significantly lower than that in the control strain, while the number of VBNC cells in the ΔdicC mutant strain was higher than that in the control strain, but decreasing again after DicC complementation in the mutant strain (Figure 2C). Similar to the above findings, the number of VBNC cells in the DicA strain was higher than that in the control strain (Figure 2C), indicating the role of DicC and DicA in the formation of the VBNC state. These results demonstrated that DicC negatively regulates the formation of VBNC E. coli O157:H7 induced by HPCD, while DicA could promote the process of VBNC cell formation.

Figure 2. Effects of DicA and DicC on the percent changes in the number of VBNC cells induced by HPCD. (A) Changes in VBNC cell percentage generated by HPCD in the WT strain, ΔdicC mutant, and ΔdicC/DicC strain. (B) Changes in VBNC cell percentage generated by HPCD in the vector strain, DicC strain and DicA strain. (C) Photomicrographs of VBNC cells stained with the LIVE/DEAD BacLight Bacterial Viability Kit and examined under a fluorescence confocal microscope. Green: viable cells, red: dead cells. Bar = 20 μm. Error bars show the standard errors of the means. Significance was calculated by the t-test (∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001).

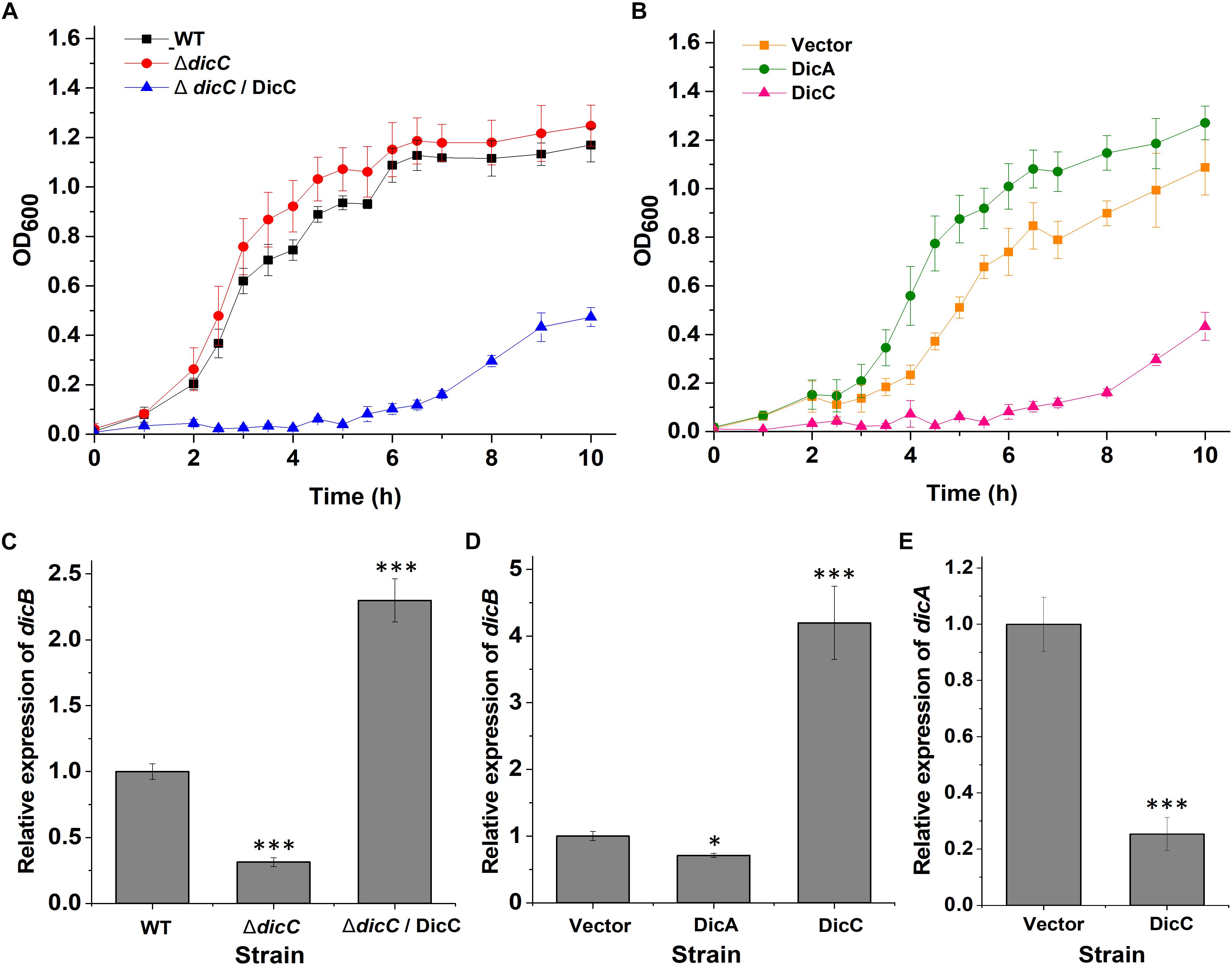

Regulatory Effect of DicC and DicA on the Growth Rate of E. coli O157:H7

DicC and DicA have been shown to regulate cell division in bacteria, suggesting that these genes can affect the bacterial growth rate (Béjar and Bouché, 1985; Béjar et al., 1986; Yun et al., 2012). Therefore, the bacterial growth rates of the WT, ΔdicC mutant and ΔdicC/DicC complementary strains as well as the vector, DicC and DicA strains were tested. The experimental results showed that the ΔdicC mutant grew faster than the WT strain, while the ΔdicC/DicC complementary strain exhibited dramatically slower growth (Figure 3A), which may be due to the significantly high dicC expression level in the complementary strain. In addition, the growth rate of the DicC recombinant strain was obviously slower than that of the vector strain, but the cell growth rate increased in the DicA-overexpressing strain compared with the vector strain (Figure 3B). The above results indicated that DicC can inhibit bacterial cell division and reduce the growth rate, while DicA can promote cell division and enhance the growth rate.

Figure 3. Effect of DicA and DicC on the growth rate of E. coli O157:H7. (A) Growth curves of the WT E. coli O157:H7, ΔdicC mutant and DicC complementary strains cultured at 37°C in LB. (B) Growth curves of the empty vector strain and DicA- and DicC-overexpressing strains cultured at 37°C in LB. (C) Detection of dicB gene expression in the WT, ΔdicC mutant and DicC complementary strains by qPCR. (D) Detection of dicB gene expression in the empty vector strain and DicA- and DicC-overexpressing strains by qPCR. (E) Relative expression of the dicA gene in the empty vector strain and DicC-overexpressing strain. Error bars show the standard errors of the means. Significance was calculated by the t-test (∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001).

It has been reported that DicC and DicA affect cell division and growth rate by regulating the expression of the dicB gene (Yun et al., 2012; Yang et al., 2016). Therefore, the expression of the dicB gene in the WT, mutant, vector and recombinant strains was determined by qPCR. The results showed that the transcription level of dicB was lower in the ΔdicC mutant strain and DicA strain than in the WT strain and vector strain, respectively, while it was significantly higher in the DicC recombinant strain than in the vector strain (Figures 3C,D). The different expression levels of dicB correlated with the differences in bacterial growth rates among the WT, ΔdicC mutant, vector, DicA recombinant and DicC recombinant strains. These results indicated that DicA could inhibit the expression of dicB and thereby promote cell division and increase the growth rate, while overexpression of DicC promoted the expression of the dicB gene and thereby inhibited cell division and decreased the growth rate.

To elucidate why overexpression of DicC promoted the expression of the dicB gene, we further tested the expression of the dicA gene in the DicC-overexpressing strain. Compared with the vector strain, the expression of the dicA gene was dramatically downregulated in the DicC-overexpressing strain (Figure 3E), which suggested that upregulation of dicB gene expression in the DicC-overexpressing strain was due to inhibition of dicA expression. These results indicated that overexpression of the dicC gene decreased the level of the dicA gene and that DicA plays a role in the inhibition of dicB gene expression. In this experiment, we found that the growth rates of the ΔdicC mutant and DicA strains increased, while that of the DicC strain decreased. Coincidentally, the ability of the two strains to form VBNC cells changed similarly compared with the control strains. These results suggest that changes in the bacterial growth rate may positively regulate the formation of VBNC cells. In addition, since DicA and DicC affect cell division by regulating dicB, we constructed ΔdicB mutant strain, and the experimental results showed that compared with the WT strain, the dicB gene was not expressed in the ΔdicB mutant. We also determined the number of VBNC cells formed in the ΔdicB mutant strain under HPCD treatment, and the results showed that, compared with the WT strain, the number of VBNC cells formed in the ΔdicB mutant strain increased significantly (Supplementary Figure S1). These results indicated that deletion of dicB could also promote VBNC formation.

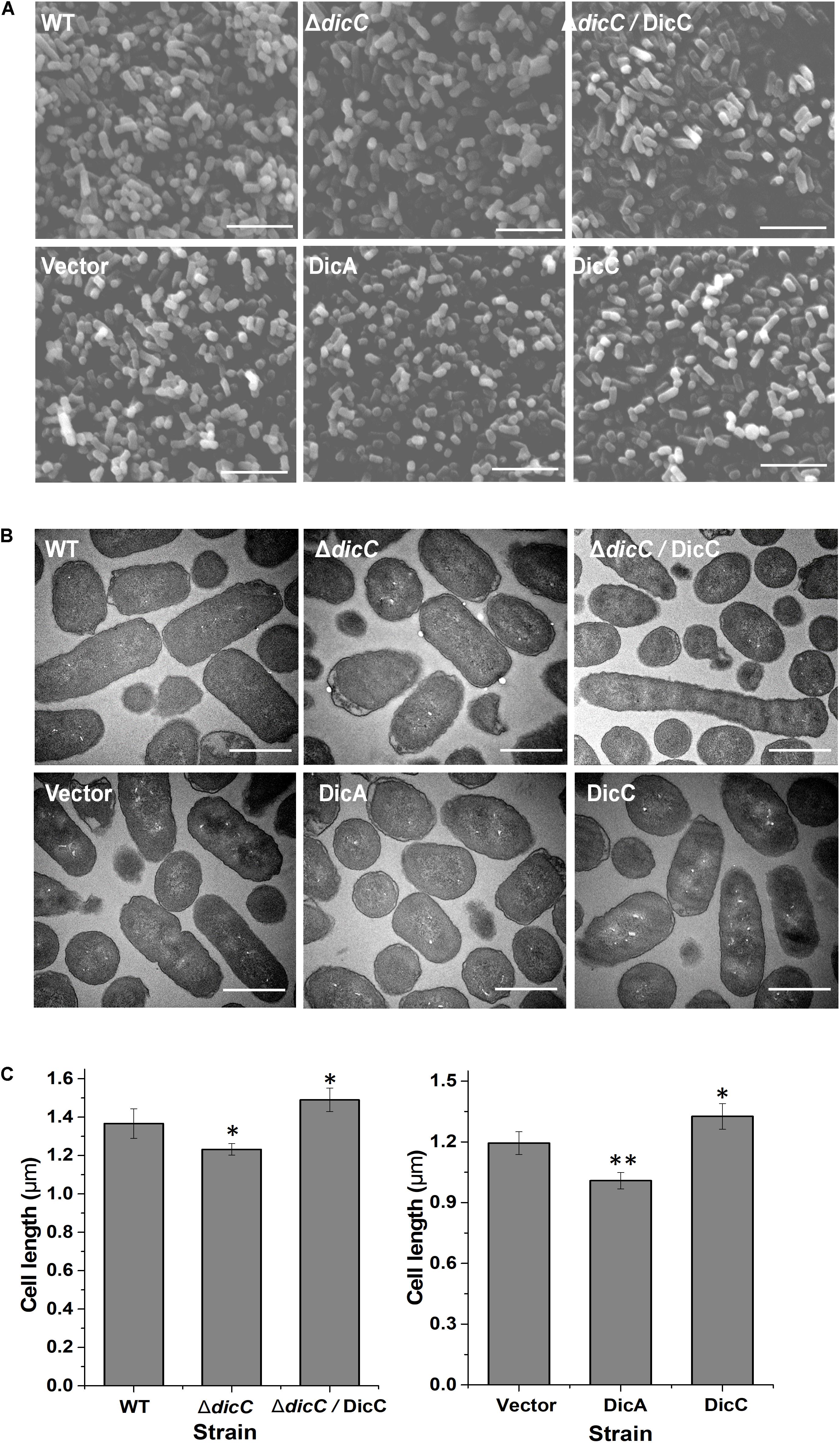

Morphological Changes in Cells of the ΔdicC Mutants and DicA/DicC-Overexpressing Strains

Changes in cell morphology are related to the adaptation of bacteria to external adversities (Justice et al., 2008). Many bacterial cell morphological changes occur after entry into the VBNC state (Chaiyanan et al., 2007; Oh et al., 2015; Zhao et al., 2017). One of the most important characteristics is that the cells exhibit dwarfism or shift from bacilli to cocci when entering the VBNC state, which helps bacterial cells better cope with external stress conditions. However, it is rarely studied whether the changes in bacterial cell morphology affect the formation of the VBNC state. Therefore, we observed the cell morphology of the ΔdicC mutant and DicC-overexpressing recombinant strains by SEM and TEM. The results showed that the cells of the ΔdicC mutant strain were shorter and rounder than those of the WT strain, while the cells of the ΔdicC/DicC complementary strain were longer (Figures 4A,B, top). The cell morphologies of the vector strain, DicC strain, and DicA strain were also observed. The cells of the DicC strain were much longer and the cells of the DicA strain were rounder and shorter than vector strain (Figures 4A,B, bottom). Furthermore, the cell lengths of the strains were recorded. The results showed that the cell lengths of the ΔdicC mutant strain and the DicA-overexpressing strain were significantly lower than those of the WT strain and the empty vector strain, respectively (Figure 4C). The cell lengths of the DicC complementary strain and DicC-overexpressing strain were higher than those of the WT strain and empty vector strain, respectively (Figure 4C). These results further indicated that the dicC and dicA genes had an impact on the cell length of E. coli O157:H7 cells. The different morphologies of the ΔdicC mutant and DicC/DicA-overexpressing strains may also be responsible for the different abilities of the strains to form VBNC cells. Therefore, these results suggested that the different morphologies of bacteria may affect their entry into the VBNC state.

Figure 4. Changes in the cell morphology of the ΔdicC mutant train, ΔdicC/DicC complementary strain and dicA, dicC-overexpressing strain. (A) Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) (magnification of × 15,000). (B) Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) (magnification of × 15,000) photomicrographs. (C) Cell length statistical data of the WT, ΔdicC mutant, ΔdicC/DicC complementary, vector, DicA, and DicC strains. Bar = 5 μm (A), bar = 1 μm (B). SEM images were used for the measurement of cell length. For each strain, cell length data were recorded from six fields of view, and at least 300 intact cells were measured. Significance was calculated by the t-test (∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001).

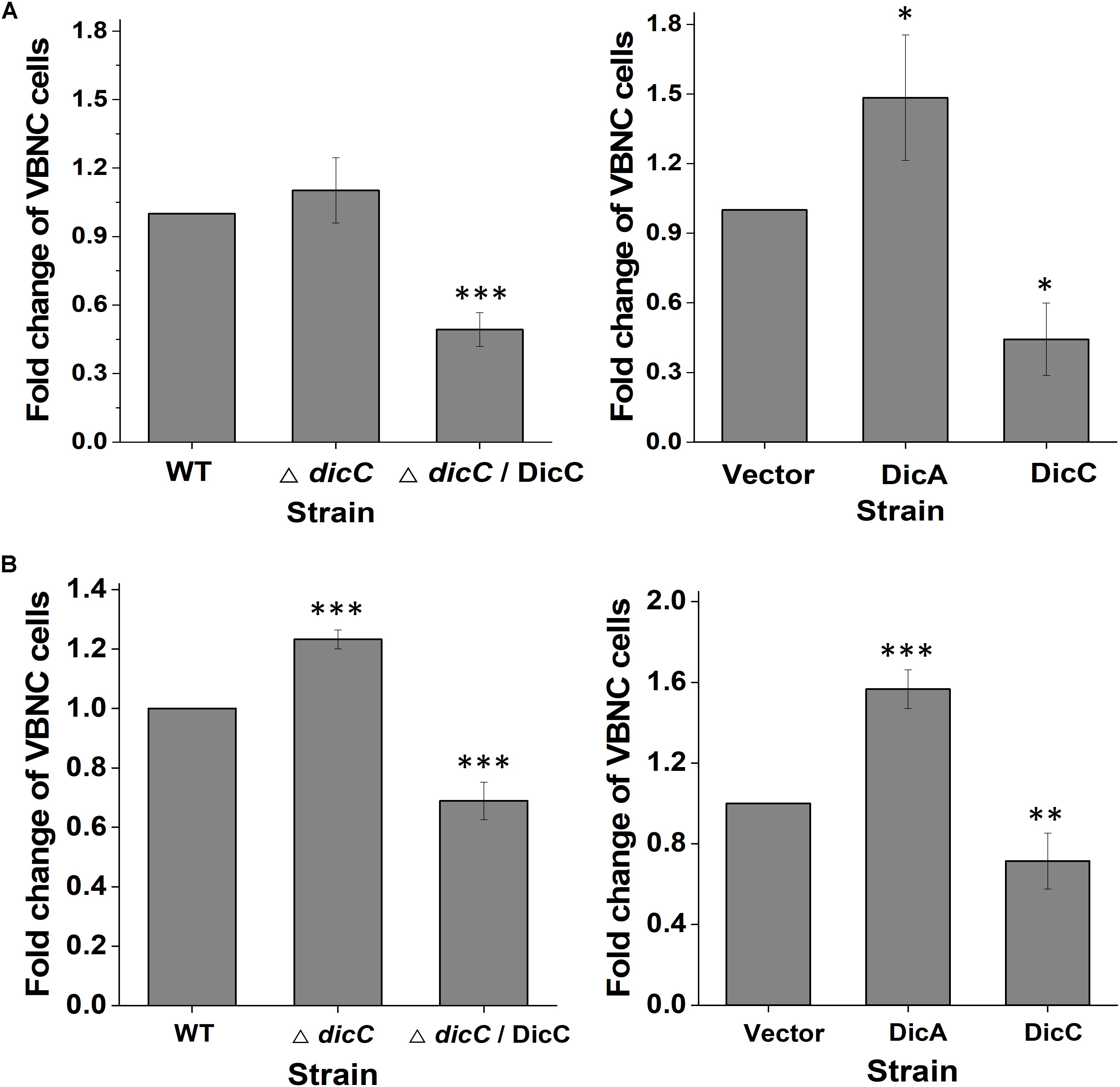

Impacts of DicC and DicA on the Formation of VBNC E. coli O157:H7 Cells Under Acid and H2O2 Stress

Previous studies have shown that E. coli can enter the VBNC state under different adverse conditions, including acid and oxidative stress (Ding et al., 2016). To confirm whether the DicC and DicA proteins influence the ability of E. coli to form a VBNC state under other adverse conditions, E. coli O157:H7 in the exponential growth phase was treated with pH 2.5 sodium chloride (0.85% w/v) and 50 mM H2O2. The results showed that compared with the WT strain, the proportion of ΔdicC mutant strain cells entering the VBNC state was higher under acid and H2O2 stress, while the proportion was significantly lower for the ΔdicC/DicC complementary strain (Figures 5A,B). We also tested the ability of DicC- and DicA-overexpressing strains to form VBNC cells under acid and H2O2 stress. The results showed that the ability of the DicC-overexpressing recombinant strain to form VBNC state under acid and H2O2 stress was poorer than that of the vector strain, but the ability of the DicA-overexpressing strain was stronger than that of the vector strain (Figures 5A,B). Meanwhile, compared with the WT strain, the number of VBNC cells formed in the ΔdicB mutants increased significantly under acidic and oxidative conditions (Supplementary Figure S1). These results indicated that similar to HPCD induction, DicC can also delay the formation of VBNC E. coli cells, and DicA can promote this process under acid and H2O2 stress, suggesting that the regulation of cell division and growth rate by DicC may also be positively correlated with bacterial VBNC state formation under acidic and oxidative stress.

Figure 5. Effects of DicC and DicA on the ability of E. coli O157:H7 to form the VBNC state under acid stress (A) and H2O2 stress (B). (A) Changes in the VBNC cell percentage in the WT, ΔdicC mutant, ΔdicC/DicC, vector, DicC strain and DicA strains under pH 2.5 sodium chloride. (B) Changes in the VBNC cell percentage in the WT, ΔdicC mutant, and ΔdicC/DicC, vector, DicC and DicA strains under 50 mM H2O2. Error bars show the standard errors of the means. Significance was calculated by the t-test (∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001).

Discussion

Our previous transcriptomic and proteomic study suggested that DicC might be involved in the formation of the VBNC state of E. coli O157:H7 induced by HPCD (Zhao et al., 2013). In this study, the specific role of DicC and DicA, as well as the association with cell growth rate and cell morphology in the formation of VBNC E. coli O157:H7, was demonstrated through gene deletion and overexpression. DicC delays the formation of the VBNC state, while DicA facilitates the formation of the VBNC state.

In E. coli, phage-encoded genes play an important role in host survival under adverse environmental conditions (Brussow et al., 2004; Wang et al., 2010). The Dic family proteins of E. coli encoded by the Kim (Qin) phage, one of nine cryptic prophages in E. coli, contains three genes encoding the DicA, DicB and DicC proteins and one sRNA transcribed by DicF (Cam et al., 1988; Yang et al., 2016). FtsZ, a bacterial cytoskeletal protein, plays a key role in bacterial cell division, which is spatially regulated by Min oscillation through inhibition of Z ring formation (Zhuo et al., 2007; Erickson et al., 2010). Nevertheless, the DicB protein can enhance the division-inhibitory activity of MinC, which is associated with Min oscillation and can restrain the division of bacterial cells (Johnson et al., 2002). Under normal circumstances, the expression of the dicB gene in cells is relatively low, and cells can divide normally; however, when the expression of the dicB gene is activated, cell division rapidly ceases (Labie et al., 1989). A previous study indicated that DicA can inhibit the transcription of the dicB gene (Béjar et al., 1988). In addition, recent advances indicated that downregulation of the dicA gene by CnuK9E, a mutant of the OriC-binding nucleoid protein (Cnu), could induce a burst of dicB expression and inhibit cell division (Yun et al., 2012). In this study, we found that overexpression of the dicA gene resulted in an increase in the cell growth rate, implying that the expression levels of dicB decreased and cell division was suppressed, which is consistent with previous studies.

Relevant studies on the function of dicC gene are relatively rare. Previous studies have shown that the DicC protein can complement the function of the DicA protein, thereby inhibiting the expression of the dicB gene, but the evidence is unclear (Béjar et al., 1986). In this study, we observed the opposite phenomenon: when dicC was overexpressed, the cell growth rate of the DicC strain decreased. In the ΔdicC mutants, the expression level of the dicB gene decreased, and the cell growth rate became higher than that in the WT strain. To further explain this phenomenon, the regulatory relationship between the dicA and dicC genes was demonstrated. It was demonstrated for the first time that the expression level of the dicB gene increased and that dicA was downregulated in the DicC-overexpressing strain, which suggested that the increased expression of dicB was due to the inhibition of dicA. This finding also indirectly indicated that dicA plays a major role in inhibiting the expression of dicB. In addition, the results also implied that DicC might inhibit the expression of the dicA gene to some extent, possibly because these two genes share a common promoter region, but the direction of transcription is the opposite. Yun et al. (2012) found that overexpression of the dicA gene could significantly inhibit the expression of dicC, which was consistent with the results of this study. Here, we confirmed that overexpression of dicC can also inhibit the expression of DicA, thereby initiating dicB transcription and finally inhibiting bacterial growth. The construction of the dicA deletion mutant was not successful in this study, which may be due to the deletion of dicA leading to significantly increased expression of dicB and bacterial growth was suppressed, so positive bacterial colonies could not be screened.

To date, there have been some reports regarding the relationship between cell division and VBNC formation; however, these studies were conducted at the omics level, while few studies regarding specific mechanisms have been reported. Xu et al. (2018) showed that the expression of cell division-related genes, including ftsZ, ftsA, ftsQ, and ftsH, was downregulated in VBNC V. cholerae, while minC and slmA were upregulated, leading to inhibition of cell division. Rozen et al. (2002) reported that the suppressed genes were related to cell division and suggested mechanisms for the cessation of growth in VBNC E. coli. In addition to these omics studies, a recent study found that the cpdA gene, encoding cAMP phosphodiesterase, delayed the formation of the E. coli VBNC state by reducing intracellular cAMP levels, which negatively regulated cell division and growth under stress conditions. That is, the lack of cAMP-CRP effectively led to retention of high colony forming activity and promoted cell division, which was not conducive to the formation of the VBNC state (Nosho et al., 2018). These results suggested that the growth rate of E. coli cells was negatively correlated with VBNC formation. Contrary to the results in this study, our results indicated that the bacterial growth rate was positively correlated with the formation of the VBNC state. A previous report proposed that VBNC state may be part of a dormant state in which active cells exist stochastically (Ayrapetyan et al., 2015b). Interestingly, studies have also shown that the VBNC state exists stochastically in unstressed growing cultures, similar to the characteristics of persister cells (Orman and Brynildsen, 2013; Ayrapetyan et al., 2015a). It was found that even during the logarithmic phase, there were more viable cells than culturable cells of Vibrio vulnificus, suggesting that VBNC cells existed stochastically during logarithmic-phase growth (Ayrapetyan et al., 2015a). Therefore, we speculate that in this study, with the increase in the cell growth rate of the DicA-overexpressing strain and the ΔdicC mutant strain, the number of VBNC cells randomly generated during logarithmic growth may also increase, eventually leading to an increase in the number of VBNC cells induced by stress; however, this hypothesis needs to be further verified.

Changes in cell morphology and cell size are distinct characteristics of VBNC cells (Zhao et al., 2017). Compared with culturable cells, VBNC cells may exhibit dwarfism. This condition provides the cells with increased surface area for nutrient uptake, which is beneficial for cell survival under stressful conditions such as starvation, low temperature and extreme pH (Zhao et al., 2017). Gupte et al. (2003) observed that Salmonella typhi cells exhibited gradual rounding after entering the VBNC state. The change from a bacillary to a coccoid form was also observed in VBNC Vibrio parahaemolyticus, with the occurrence of wrinkles and herpes-like structures on the cell surface (Chen et al., 2009). Similar structures were reported in VBNC E. coli cells, accompanied by enriched intracellular DNA (Signoretto et al., 2002; Sachidanandham et al., 2005). In addition, the shapes of Campylobacter jejuni and Edwardsiella tarda were found to transform from the spiral to coccoid form and from short rods to the coccoid form, respectively (Chaisowwong et al., 2012). Currently, the study of morphological changes in VBNC cells is limited to the description of characteristics, but there is no evidence regarding whether the changes affect the formation of VBNC cells. In this study, it was found that after deletion of the dicC gene and overexpression of the dicA gene, an increase in bacterial growth rate was accompanied by the formation of a short and round shape compared with the WT strain, which was similar to the morphology of VBNC bacteria. Moreover, an increased number of cells of the two strains entered the VBNC state after induction by different stress factors. Hence, these results indirectly indicated that changes in morphology could affect bacterial entry into the VBNC state. It was presented for the first time that a short and round shape might be favorable for bacterial entry into the VBNC state.

Conclusion

This study proved for the first time that the formation of the VBNC state induced by HPCD was associated with the cell division-related genes dicC and dicA. Our investigation demonstrated that the cell growth rate regulated by DicC and DicA with changes in cell morphology may be positively correlated with the formation of the VBNC state. Elucidation of the molecular mechanism of the VBNC state will provide insights into bacterial stress responses and the physiological characteristics of the VBNC state, which may provide inspiration for the development of novel detection methods for VBNC bacteria or direct prevention of the entry of cells into this hard-to-detect state.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated for this study are available on request to the corresponding author.

Author Contributions

HP and KD carried out the experiments and wrote the manuscript. LR gave advice and assistance during the experiments. YW and LZ designed the experiments and revised the manuscript. XL revised the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC) (No. 31571933).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmicb.2019.02850/full#supplementary-material

References

Asakura, H., Kawamoto, K., Haishima, Y., Igimi, S., Yamamoto, S., and Makino, S. (2008). Differential expression of the outer membrane protein W (OmpW) stress response in enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157:H7 corresponds to the viable but non-culturable state. Res. Microbiol. 159, 709–717. doi: 10.1016/j.resmic.2008.08.005

Ayrapetyan, M., and Oliver, J. D. (2016). The viable but non-culturable state and its relevance in food safety. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 8, 127–133. doi: 10.1016/j.cofs.2016.04.010

Ayrapetyan, M., Williams, T., and Oliver, J. D. (2018). Relationship between the viable but nonculturable state and antibiotic persister cells. J. Bacteriol. 200:e249-18. doi: 10.1128/JB.00249-18

Ayrapetyan, M., Williams, T. C., Baxter, R., Oliver, J. D., and Camilli, A. (2015a). Viable but nonculturable and persister cells coexist stochastically and are induced by human serum. Infect. Immun. 83, 4194–4203. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00404-15

Ayrapetyan, M., Williams, T. C., and Oliver, J. D. (2015b). Bridging the gap between viable but non-culturable and antibiotic persistent bacteria. Trends Microbiol. 23, 7–13. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2014.09.004

Béjar, S., Bouche, F., and Bouche, J. P. (1988). Cell-division inhibition gene Dicb is regulated by a locus similar to Lambdoid Bacteriophage Immunity Loci. Mol. Gen. Genet. 212, 11–19. doi: 10.1007/bf00322439

Béjar, S., and Bouché, J. P. (1985). A new dispensable genetic locus of the terminus region involved in control of cell division in Escherichia coli. Mol. Gen. Genet. 201, 146–150. doi: 10.1007/bf00425651

Béjar, S., Cam, K., and Bouché, J. P. (1986). Control of cell division in Escherichia coli. DNA sequence of dicA and of a second gene complementing mutation dicA1, dicC. Nucleic Acids Res. 14, 6821–6833. doi: 10.1093/nar/14.17.6821

Boaretti, M., del Mar Lleo, M., Bonato, B., Signoretto, C., and Canepari, P. (2003). Involvement of rpoS in the survival of Escherichia coli in the viable but non-culturable state. Environ. Microbiol. 5, 986–996. doi: 10.1046/j.1462-2920.2003.00497.x

Brussow, H., Canchaya, C., and Hardt, W. D. (2004). Phages and the evolution of bacterial pathogens: from genomic rearrangements to lysogenic conversion. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 68, 560–602. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.68.3.560-602.2004

Cam, K., Béjar, S., Gil, D., and Bouché, J. P. (1988). Identification and sequence of gene dicB: translation of the division inhibitor from an in-phase internal start. Nucleic Acids Res. 16, 6327–6338. doi: 10.1093/nar/16.14.6327

Chaisowwong, W., Kusumoto, A., Hashimoto, M., Harada, T., Maklon, K., and Kawamoto, K. (2012). Physiological characterization of Campylobacter jejuni under cold stresses conditions: its potential for public threat. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 74, 43–50. doi: 10.1292/jvms.11-0305

Chaiyanan, S., Chaiyanan, S., Grim, C., Maugel, T., and Colwell, R. R. (2007). Ultrastructure of coccoid viable but non-culturable Vibrio cholerae. Environ. Microbiol. 9, 393–402. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2006.01150.x

Chatterji, D., Fujita, N., and Ishihama, A. (1998). The mediator for stringent control, ppGpp, binds to the beta-subunit of Escherichia coli RNA polymerase. Genes Cells 3, 279–287. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2443.1998.00190.x

Chen, S., Li, X., Wang, Y., Zeng, J., Ye, C., Li, X., et al. (2018). Induction of Escherichia coli into a VBNC state through chlorination/chloramination and differences in characteristics of the bacterium between states. Water Res. 142, 279–288. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2018.05.055

Chen, S. Y., Jane, W. N., Chen, Y. S., and Wong, H. C. (2009). Morphological changes of Vibrio parahaemolyticus under cold and starvation stresses. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 129, 157–165. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2008.11.009

Colwell, R. R. (2000). Viable but nonculturable bacteria: a survival strategy. J. Infect. Chemother. 6, 121–125. doi: 10.1007/pl00012151

Datsenko, K. A., and Wanner, B. L. (2000). One-step inactivation of chromosomal genes in Escherichia coli K-12 using PCR products. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 97, 6640–6645. doi: 10.1073/pnas.120163297

Day, A. P., and Oliver, J. D. (2004). Changes in membrane fatty acid composition during entry of Vibrio vulnificus into the viable but nonculturable state. J. Microbiol. 42, 69–73. doi: 10.1016/j.optcom.2006.05.068

Ding, T., Suo, Y., Xiang, Q., Zhao, X., Chen, S., Ye, X., et al. (2016). Significance of viable but nonculturable Escherichia coli: induction, detection, and control. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 27, 417–428. doi: 10.4014/jmb.1609.09063

Dinu, L. D., and Bach, S. (2011). Induction of viable but nonculturable Escherichia coli O157:H7 in the phyllosphere of lettuce: a food safety risk factor. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 77, 8295–8302. doi: 10.1128/AEM.05020-11

Du, M., Chen, J., Zhang, X., Li, A., Li, Y., and Wang, Y. (2006). Retention of virulence in a viable but nonculturable Edwardsiella tarda isolate. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 73, 1349–1354. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02243-06

Erickson, H. P., Anderson, D. E., and Osawa, M. (2010). FtsZ in bacterial cytokinesis: cytoskeleton and force generator all in one. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 74, 504–528. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00021-10

Gupte, A. R., de Rezende, C. L. E., and Joseph, S. W. (2003). Induction and resuscitation of viable but nonculturable Salmonella enterica serovar typhimurium DT104. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69, 6669–6675. doi: 10.1128/aem.69.11.6669-6675.2003

Johnson, J. E., Lackner, L. L., and de Boer, P. A. J. (2002). Targeting of DMinC/MinD and DMinC/DicB complexes to septal rings in Escherichia coli suggests a multistep mechanism for MinC-Mediated destruction of nascent FtsZ rings. J. Bacteriol. 184, 2951–2962. doi: 10.1128/JB.184.11.2951-2962.2002

Justice, S. S., Hunstad, D. A., Cegelski, L., and Hultgren, S. J. (2008). Morphological plasticity as a bacterial survival strategy. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 6:162. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1820

Karmali, M. A., Petric, M., Lim, C., Fleming, P. C., Arbus, G. S., and Lior, H. (1985). The association between idiopathic hemolytic uremic syndrome and infection by verotoxin-producing Escherichia coli. J. Infect. Dis. 151, 775–782. doi: 10.1086/jid/189.3.566

Labie, C., Bouche, F., and Bouche, J. P. (1989). Isolation and mapping of Escherichia coli mutations conferring resistance to division inhibition protein DicB. J. Bacteriol. 171, 4315–4319. doi: 10.1016/0003-6870(82)90111-9

Li, L., Mendis, N., Trigui, H., Oliver, J. D., and Faucher, S. P. (2014). The importance of the viable but non-culturable state in human bacterial pathogens. Front. Microbiol. 5:258. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2014.00258

Lin, H., Ye, C., Chen, S., Zhang, S., and Yu, X. (2017). Viable but non-culturable E. coli induced by low level chlorination have higher persistence to antibiotics than their culturable counterparts. Environ. Poll. 230, 242–249. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2017.06.047

Liu, Y., Wang, C., Tyrrell, G., and Li, X. F. (2010). Production of Shiga-like toxins in viable but nonculturable Escherichia coli O157:H7. Water Res. 44, 711–718. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2009.10.005

Livak, K., and Schmittgen, T. (2001). Analysis of relative gene expression data using Real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods 25, 402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262

Makino, S. I., Kii, T., Asakura, H., Shirahata, T., Ikeda, T., Takeshi, K., et al. (2000). Does enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157:H7 enter the viable but nonculturable state in salted salmon roe? Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66, 5536–5539. doi: 10.1128/AEM.66.12.5536-5539.2000

Nataro, J. P., and Kaper, J. B. (1998). Diarrheagenic Escherichia coli. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 11, 142–201. doi: 10.1128/CMR.11.2.403

Nosho, K., Fukushima, H., Asai, T., Nishio, M., Takamaru, R., Kobayashi-Kirschvink, K. J., et al. (2018). cAMP-CRP acts as a key regulator for the viable but non-culturable state in Escherichia coli. Microbiol. 164, 410–419. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.000618

Oh, E., McMullen, L., and Jeon, B. (2015). Impact of oxidative stress defense on bacterial survival and morphological change in Campylobacter jejuni under aerobic conditions. Front. Microbiol. 6:295. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2015.00295

Oliver, J. D. (2005a). Induction of Escherichia coli and Salmonella typhimurium into the viable but nonculturable state following chlorination of wastewater. J. Water Health. 3, 249–257. doi: 10.2166/wh.2005.040

Oliver, J. D. (2010). Recent findings on the viable but nonculturable state in pathogenic bacteria. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 34, 415–425. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2009.00200.x

Orman, M. A., and Brynildsen, M. P. (2013). Establishment of a method to rapidly assay bacterial persister metabolism. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 57, 4398–4409. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00372-13

Orruno, M., Kaberdin, V. R., and Arana, I. (2017). Survival strategies of Escherichia coli and Vibrio spp.: contribution of the viable but nonculturable phenotype to their stress-resistance and persistence in adverse environments. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 33:45. doi: 10.1007/s11274-017-2218-5

Ramamurthy, T., Ghosh, A., Pazhani, G. P., and Shinoda, S. (2014). Current perspectives on viable but non-culturable (VBNC) pathogenic bacteria. Front. Publ. Health 2:103. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2014.00103

Roszak, D. B., Grimes, D. J., and Colwell, R. R. (1984). Viable but nonrecoverable stage of Salmonella-Enteritidis in aquatic systems. Can. J. Microbiol. 30, 334–338. doi: 10.1139/m84-049

Rozen, Y., Larossa, R. A., Templeton, L. J., Smulski, D. R., and Belkin, S. (2002). Gene expression analysis of the response by Escherichia coli to seawater. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 81, 15–25. doi: 10.1023/a:1020500821856

Sachidanandham, R., Gin, K. Y., and Poh, C. L. (2005). Monitoring of active but non-culturable bacterial cells by flow cytometry. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 89, 24–31. doi: 10.1002/bit.20304

Signoretto, C. (2000). Cell wall chemical composition of Enterococcus faecalis in the viable but nonculturable state. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66, 1953–1959. doi: 10.1128/AEM.66.5.1953-1959.2000

Signoretto, C., del Mar Lleo, M., and Canepari, P. (2002). Modification of the peptidoglycan of Escherichia coli in the viable but nonculturable state. Curr. Microbiol. 44, 125–131. doi: 10.1007/s00284-001-0062-0

Wang, X., Kim, Y., Ma, Q., Hong, S. H., Pokusaeva, K., Sturino, J. M., et al. (2010). Cryptic prophages help bacteria cope with adverse environments. Nat. Commun. 1:147. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1146

Xu, H. S., Roberts, N., Singleton, F. L., Attwell, R. W., Grimes, D. J., and Colwell, R. R. (1982). Survival and viability of nonculturable Escherichia coli and Vibrio cholerae in the estuarine and marine environment. Microb. Ecol. 8, 313–323. doi: 10.1007/BF02010671

Xu, T., Cao, H., Zhu, W., Wang, M., Du, Y., Yin, Z., et al. (2018). RNA-seq-based monitoring of gene expression changes of viable but non-culturable state of Vibrio cholerae induced by cold seawater. Environ. Microbiol. Rep. 10, 594–604. doi: 10.1111/1758-2229.12685

Yang, S., Pei, H., Zhang, X., Wei, Q., Zhu, J., Zheng, J., et al. (2016). Characterization of DicB by partially masking its potent inhibitory activity of cell division. Open Biol. 6, 160082. doi: 10.1098/rsob.160082

Yun, S. H., Ji, S. C., Jeon, H. J., Wang, X., Kim, S. W., Bak, G., et al. (2012). The CnuK9E H-NS complex antagonizes DNA binding of DicA and leads to temperature-dependent filamentous growth in E. coli. PLoS one 7:e45236. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0045236

Zhang, S., Ye, C., Lin, H., Lv, L., and Yu, X. (2015). UV disinfection induces a Vbnc State in Escherichia coli and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Environ. Sci. Technol. 49, 1721–1728. doi: 10.1021/es505211e

Zhao, F., Bi, X., Hao, Y., and Liao, X. (2013). Induction of viable but nonculturable Escherichia coli O157:H7 by high pressure CO2 and its characteristics. PLoS one 8:e62388. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0062388

Zhao, F., Wang, Y., An, H., Hao, Y., Hu, X., and Liao, X. (2016). New insights into the formation of viable but nonculturable Escherichia coli O157:H7 induced by high-pressure CO2. mBio 7:e961-16. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00961-16

Zhao, X., Zhong, J., Wei, C., Lin, C. W., and Ding, T. (2017). Current perspectives on viable but non-culturable state in foodborne pathogens. Front. Microbiol. 8:580. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.00580

Keywords: VBNC, DicC, cell division, growth rate, cell morphology

Citation: Pan H, Dong K, Rao L, Zhao L, Wang Y and Liao X (2019) The Association of Cell Division Regulated by DicC With the Formation of Viable but Non-culturable Escherichia coli O157:H7. Front. Microbiol. 10:2850. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2019.02850

Received: 29 September 2019; Accepted: 25 November 2019;

Published: 10 December 2019.

Edited by:

Hari S. Misra, Bhabha Atomic Research Centre (BARC), IndiaReviewed by:

William Doerrler, Louisiana State University, United StatesHarapriya Mohapatra, National Institute of Science Education and Research (NISER), India

Copyright © 2019 Pan, Dong, Rao, Zhao, Wang and Liao. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Yongtao Wang, d2FuZ3lvbmd0YW8xMDJAMTYzLmNvbQ==; Xiaojun Liao, bGlhb3hqdW5AaG90bWFpbC5jb20=

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Hanxu Pan1,2†

Hanxu Pan1,2† Lei Rao

Lei Rao Yongtao Wang

Yongtao Wang Xiaojun Liao

Xiaojun Liao