94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Microbiol. , 07 August 2019

Sec. Infectious Agents and Disease

Volume 10 - 2019 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2019.01776

This article is part of the Research Topic Regulation of Gene Expression in Enteropathogenic Bacteria, Volume II View all 39 articles

Faiha M. El Abbar

Faiha M. El Abbar Jiaqi Li

Jiaqi Li Harry C. Owen

Harry C. Owen C. Luke Daugherty

C. Luke Daugherty Claudia A. Fulmer

Claudia A. Fulmer Marek Bogacz

Marek Bogacz Stuart A. Thompson*

Stuart A. Thompson*Campylobacter jejuni is a Gram-negative rod-shaped bacterium that commensally inhabits the intestinal tracts of livestock and birds, and which also persists in surface waters. C. jejuni is a leading cause of foodborne gastroenteritis, and these infections are sometimes associated with the development of post-infection sequelae such as Guillain-Barré Syndrome. Flagella are considered a primary virulence factor in C. jejuni, as these organelles are required for pathogenicity-related phenotypes including motility, biofilm formation, host cell interactions, and host colonization. The post-transcriptional regulator CsrA regulates the expression of the major flagellin FlaA by binding to flaA mRNA and repressing its translation. Additionally, CsrA has previously been shown to regulate 120–150 proteins involved in diverse cellular processes. The amino acid sequence of C. jejuni CsrA is significantly different from that of Escherichia coli CsrA, and no previous research has defined the amino acids of C. jejuni CsrA that are critical for RNA binding. In this study, we used in vitro SELEX to identify the consensus RNA sequence mAwGGAs to which C. jejuni CsrA binds with high affinity. We performed saturating site-directed mutagenesis on C. jejuni CsrA and assessed the regulatory activity of these mutant proteins, using a reporter system encoding the 5′ untranslated region (5′ UTR) upstream of flaA linked translationally to the C. jejuni astA gene. These assays allowed us to identify 19 amino acids that were involved in RNA binding by CsrA, with many but not all of these amino acids clustered in predicted beta strands that are involved in RNA binding by E. coli CsrA. Decreased flaA mRNA binding by mutant CsrA proteins L2A and A36V was confirmed by electrophoretic mobility shift assays. The majority of the amino acids implicated in RNA binding were conserved among diverse Campylobacter species.

Campylobacter jejuni is a leading bacterial cause of foodborne gastroenteritis throughout the world (WHO, 2015), with 1.3 million cases of Campylobacter infections in the US (Tack et al., 2019) and 96 million cases globally each year (WHO, 2013). Symptoms typically consist of 4–7 days of severe watery to bloody diarrhea, abdominal cramping, fever, vomiting, and dehydration (Kaakoush et al., 2015). C. jejuni infection is generally acute and self-limiting, but in some patients it is associated with the development of post-infection sequelae such as autoimmune-mediated Guillain-Barré Syndrome, the leading cause of acute paralysis (Nachamkin et al., 2000). C. jejuni commensally colonizes the gastrointestinal tract of animals including poultry, cattle, swine, and sheep (Kaakoush et al., 2015). Therefore, the source of infection is often the consumption of contaminated meat (especially poultry) or drinking of contaminated raw milk (Kaakoush et al., 2015). However, exposure to environmental sources such as surface waters is suggested to cause a large proportion of Campylobacter infections (Champion et al., 2005). To survive in diverse hosts and environmental niches, C. jejuni must accommodate a range of stresses such as changes in temperature, pH, oxygen level, and exposure to host bile, digestive enzymes, and inflammatory responses. Flagella are well-characterized virulence factors in C. jejuni as they are required for pathogenicity-related phenotypes including colonization (Wassenaar et al., 1993), interactions with host cells (Guerry, 2007; Freitag et al., 2017), biofilm formation (Svensson et al., 2014), and the secretion of virulence-associated proteins such as Cia invasion antigens (Konkel et al., 1999). Mutants lacking flagella are highly attenuated in animal models (Guerry, 2007). Flagellar filaments are composed primarily of the major flagellin FlaA, the expression of which is regulated transcriptionally by FlgSR, σ54, and σ28 (Lertsethtakarn et al., 2011), as well as post-transcriptionally by the RNA-binding protein CsrA (carbon storage regulator A) (Fields and Thompson, 2008; Dugar et al., 2016; Fields et al., 2016). A C. jejuni csrA mutant shows significant reduction in epithelial cell adherence, resistance to oxidative stress, motility, biofilm formation, and ability to colonize mice, as well as a paradoxically increased ability to invade host cells (Fields and Thompson, 2008; Fields et al., 2016). Consistent with these phenotypes, a C. jejuni csrA mutant exhibited dysregulation of 120–150 proteins involved in motility, chemotaxis, host cell adherence and invasion, oxidative stress resistance, TCA cycle, respiration, and amino acid and acetate metabolism (Fields et al., 2016; Li et al., 2018). This suggests the importance of CsrA as a major global regulatory protein in C. jejuni.

In Escherichia coli and other studied bacteria, CsrA is a homodimeric protein, with each subunit composed of five beta (β) strands (β1–β5). Two identical RNA-binding pockets are formed by β1 and β5 of opposite subunits (Mercante et al., 2006, 2009; Romeo et al., 2013; Altegoer et al., 2016). CsrA typically binds the 5′ untranslated region (5′ UTR) at one or more sites of its target mRNAs, often at or near the ribosome-binding site (RBS), and usually at a stem-loop containing a conserved AnGGA sequence motif within the hairpin (Romeo and Babitzke, 2018). Binding of CsrA to mRNA blocks ribosome access and represses the initiation of translation, but it can also influence mRNA stability (Romeo and Babitzke, 2018). Regulation of CsrA activity is mediated in E. coli and other bacteria by competitive binding to small RNAs (e.g., csrB, csrC). These sRNAs contain many CsrA-binding sites which sequester CsrA and titrate its binding to target mRNAs (Romeo and Babitzke, 2018). However, C. jejuni lacks these antagonizing sRNAs, and CsrA activity is instead regulated by a mechanism similar to that of Bacillus subtilis where upon secretion of the major flagellin (FlaA), the flagellar chaperone FliW is released and binds its alternate partner CsrA (Mukherjee et al., 2011, 2016; Dugar et al., 2016; Radomska et al., 2016; Li et al., 2018). Binding to FliW modulates CsrA binding to target mRNAs and alleviates CsrA repression of flagellin expression, a regulatory mechanism required for proper flagellar morphogenesis (Mukherjee et al., 2011; Dugar et al., 2016; Li et al., 2018).

In C. jejuni, CsrA binds flaA mRNA and directly represses its translation (Dugar et al., 2016; Fields et al., 2016; Radomska et al., 2016). Although a C. jejuni csrA mutant shows normal flagellar structure (Fields et al., 2016), the decreased motility of the csrA mutant (Fields and Thompson, 2008) suggests that regulation of FlaA expression by CsrA is required for proper motility. The E. coli and C. jejuni CsrA proteins have significant divergence in amino acid sequence (Fields and Thompson, 2012), raising the question of whether features of RNA binding that were determined for E. coli also apply to C. jejuni. C. jejuni CsrA complements an E. coli csrA mutant for some, but not all, phenotypes (Fields and Thompson, 2012), suggesting some divergence of its RNA-binding characteristics. In contrast to E. coli CsrA, there have been no previous studies defining the amino acids of C. jejuni CsrA that are critical for RNA binding. Understanding the mechanism by which CsrA interacts with flaA mRNA may help in future development of strategies to overcome the impact of C. jejuni infection. In addition, the mechanism of flaA mRNA-CsrA interaction could serve as a model for C. jejuni CsrA interaction with other important target mRNAs (Fields et al., 2016; Li et al., 2018). In this study, we identified the consensus RNA sequence to which CsrA binds with high affinity, and determined the amino acid residues of CsrA that are critical for flaA mRNA binding.

The bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. All E. coli strains were grown at 37°C in Luria-Bertani (LB) broth or plates. When appropriate, growth media were supplemented with ampicillin (amp; 100 μg/ml) or chloramphenicol (cm; 30 μg/ml). C. jejuni strain 81–176 was used as a source of chromosomal DNA and was grown on Mueller-Hinton (MH) agar at 42°C in a tri-gas incubator (85% N2, 10% CO2, 5% O2). PCR primers are listed in Supplementary Table S1.

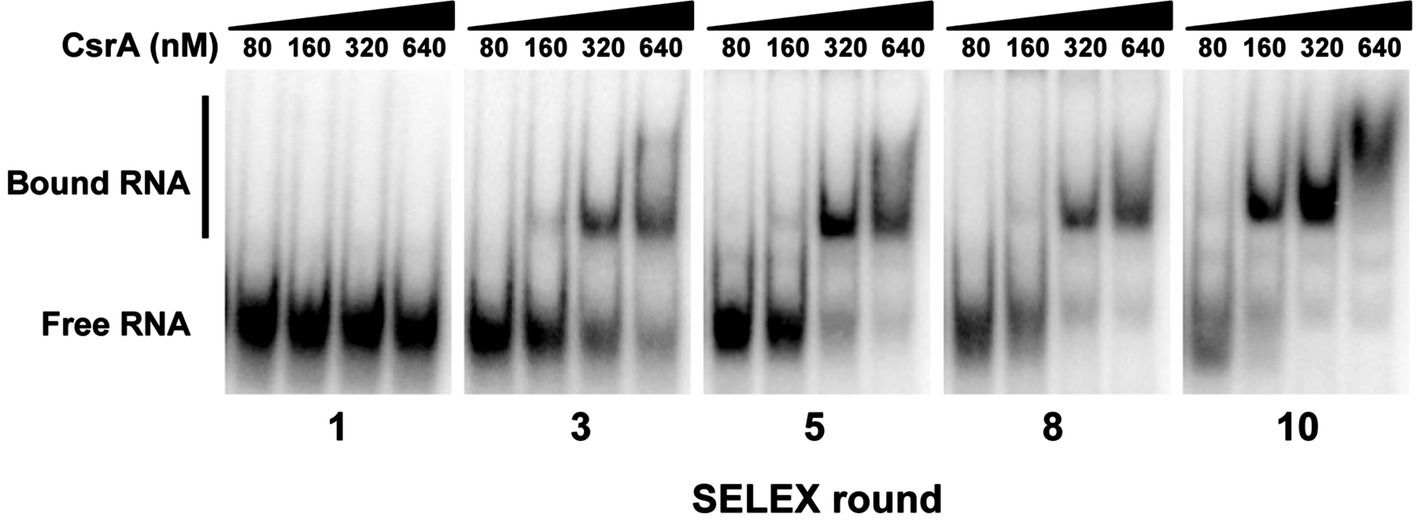

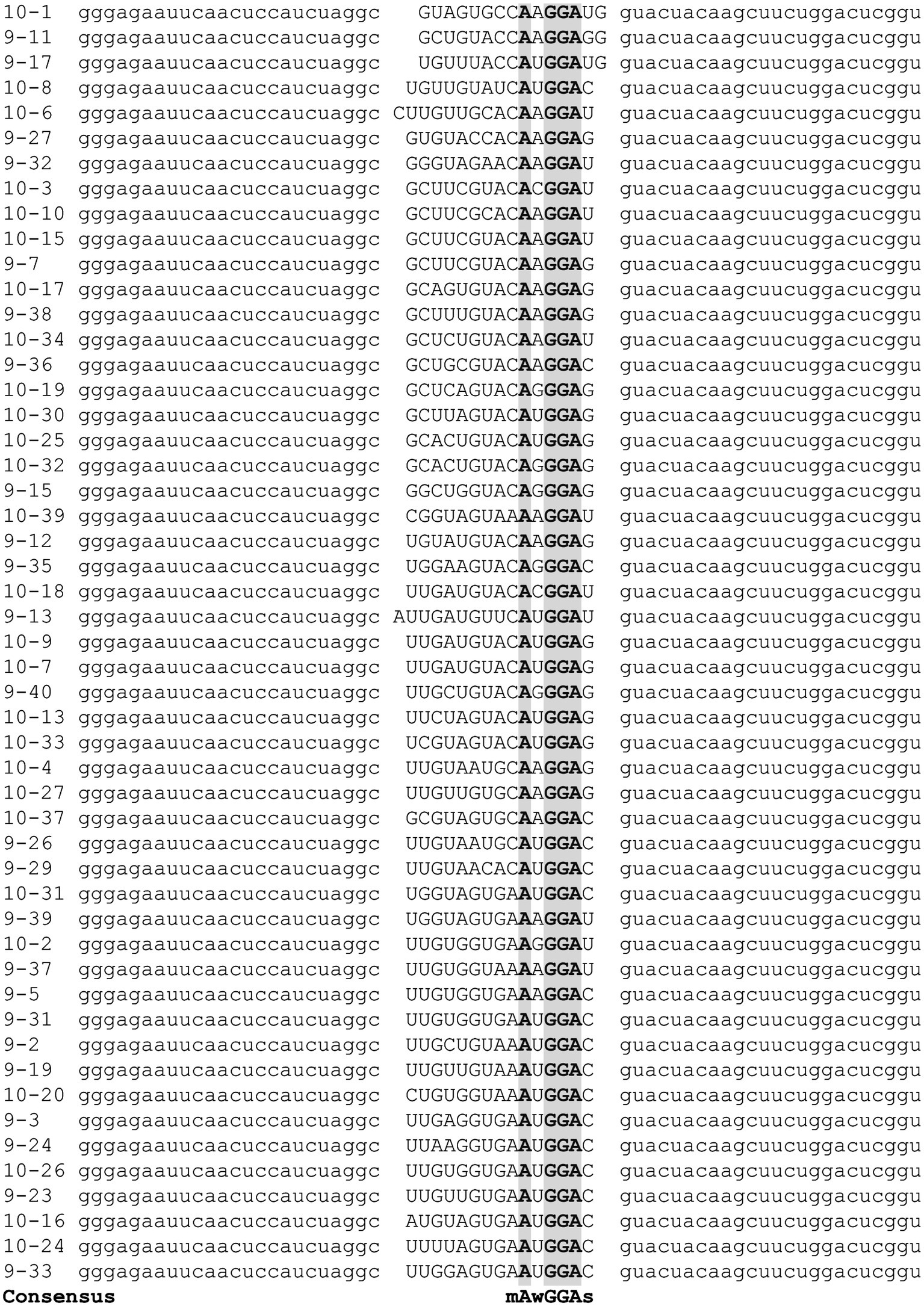

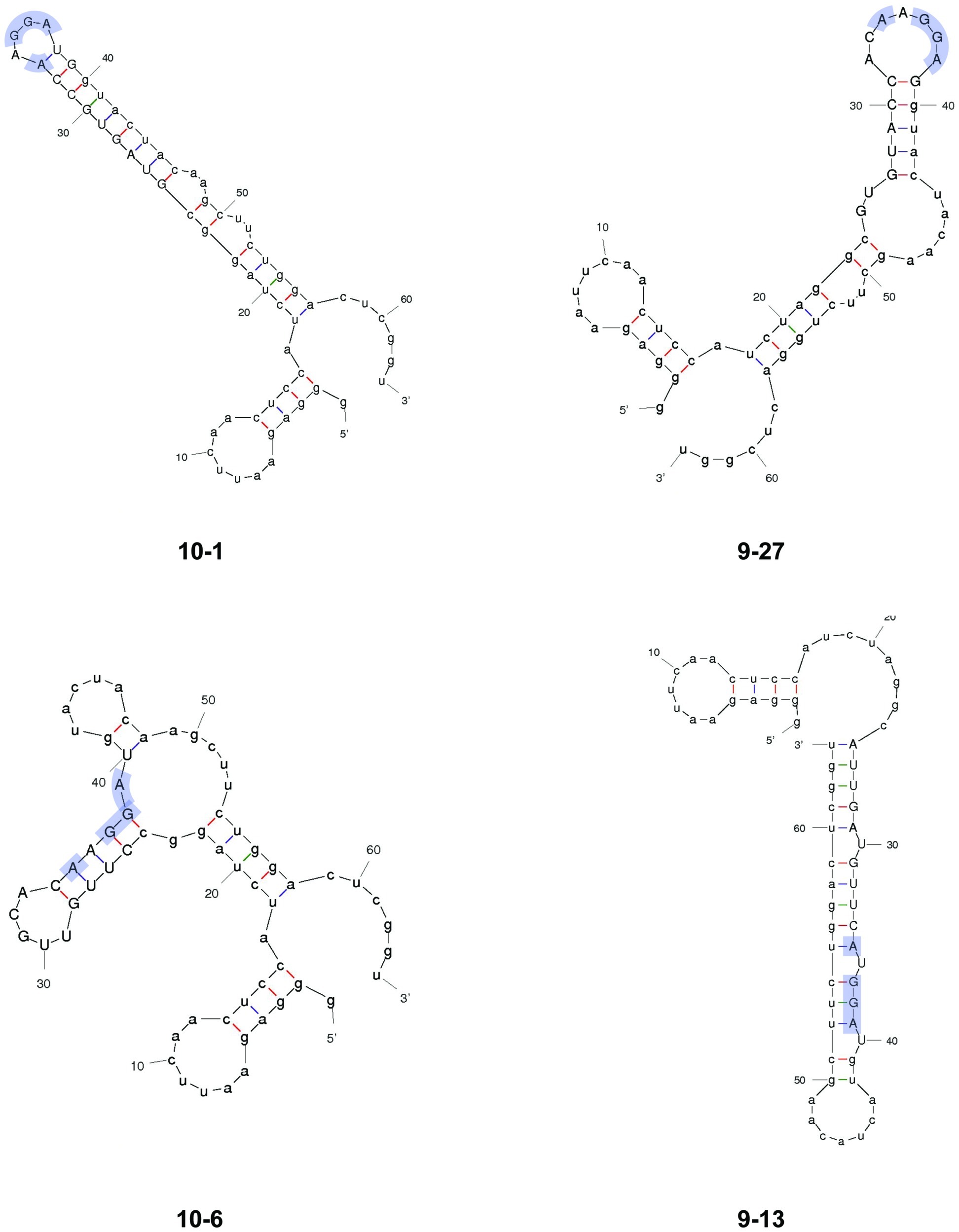

We performed in vitro systematic evolution of ligands by exponential enrichment (SELEX) (Tuerk and Gold, 1990) as modified by (Dubey et al., 2005), using purified C. jejuni CsrA-His6 (see below). Briefly, we first created a DNA template by synthesizing an 81-base oligonucleotide (SELEX15) consisting of a randomized 15-mer (N15, where N = any nucleotide) flanked by two constant regions (Supplementary Table S1). PCR on the SELEX15 template using primers P1 and P2 (Supplementary Table S1) yielded a complex mixture of 81-bp DNA fragments (a total of ~1 × 105 molecules containing every possible sequence of the random central region), which was used for in vitro transcription. Template DNA was removed by DNase I treatment, and transcribed RNA was mixed with C. jejuni CsrA-His6. CsrA-His6-RNA complexes were affinity purified using Ni-NTA slurry. Bound RNA was purified via phenol:chloroform extraction and converted to cDNA. The selected templates were then subjected to a total of 10 rounds of PCR amplification and selection as described above. The progress of the selection process was monitored by using gel mobility shift analysis, observing an increasing ability of C. jejuni CsrA-His6 to retard the mobility of the affinity-selected RNA pools. A total of 57 RT-PCR products from rounds nine and ten were cloned and sequenced; 51 unique sequences were used to generate a consensus C. jejuni CsrA-binding sequence following alignment using Clustal Omega at EMBL-EBI (Sievers et al., 2011; Li et al., 2015). The predicted secondary structure for each sequence was also assessed using MFOLD (Zuker, 2003).

Site-directed mutagenesis (SDM) was performed with a Q5 SDM kit (NEB, Ipswich, MA) using the primers listed in Supplementary Table S1. Plasmid pET-20b-CsrA (Fields et al., 2016) was used as PCR template. Each CsrA amino acid was changed individually to alanine, except for two native alanine residues (A30 and A36) that were changed to valine. The first methionine was also substituted with alanine, but an additional methionine was added upstream of the M1A mutation to initiate protein translation. The pET-20b plasmids containing csrA point mutations were all verified by DNA sequencing.

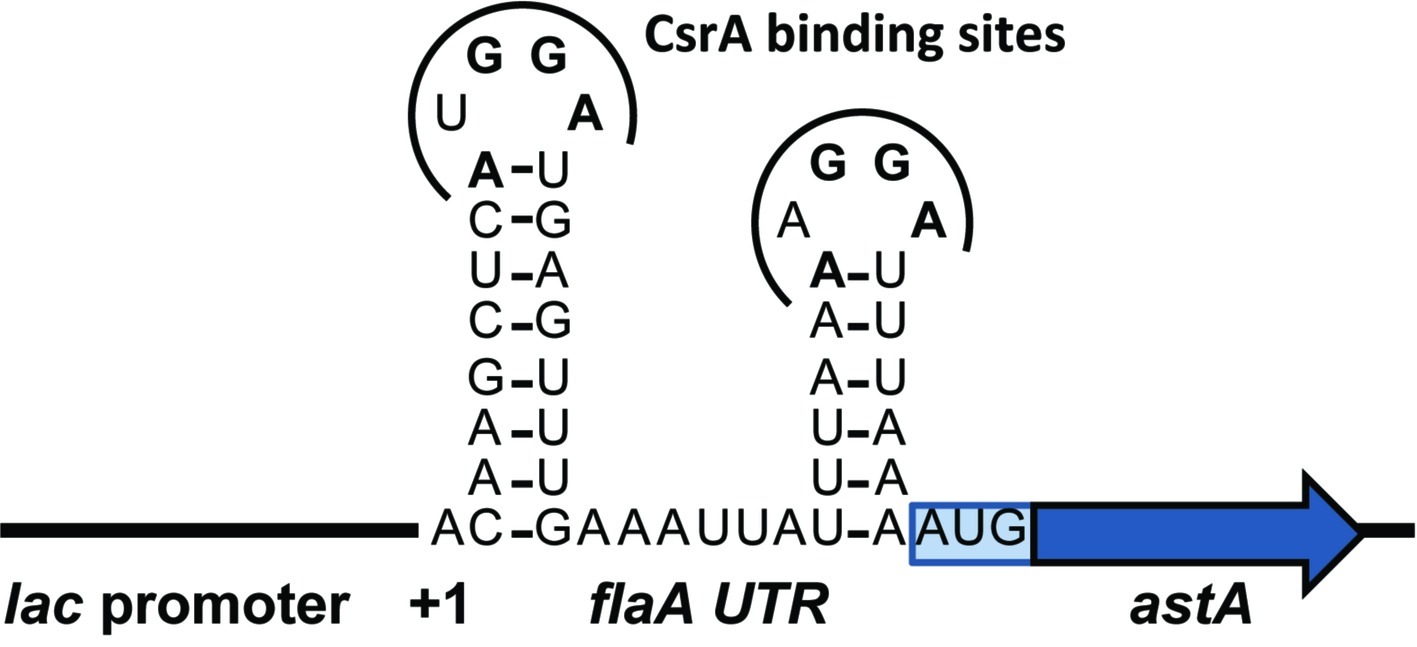

For assessing flaA mRNA binding by CsrA, we designed a translational reporter by cloning DNA encoding the flaA 5′ UTR upstream of the assayable C. jejuni gene astA encoding arylsulfatase (Yao and Guerry, 1996; Hendrixson and DiRita, 2003). DNA encoding the flaA 5′ UTR was synthesized and cloned downstream of the lac promoter in pCR2.1-TOPO by a commercial vendor (IDT, Coralville, IA), yielding plasmid pFE101 (Table 1). Inverse PCR was performed on pFE101 to introduce an NdeI site downstream of the flaA 5′ UTR DNA using primers FME01 and FME02 (Supplementary Table S1). The astA reporter gene was amplified from C. jejuni 81–176 chromosomal DNA using the primers FME03 and FME04 (Supplementary Table S1), and cloned downstream of the flaA 5′ UTR DNA using the restriction enzymes NdeI and NotI, resulting in plasmid pFE102 (Table 1). Inverse PCR using primers JO-4 and JO-5 (Supplementary Table S1) was performed on pFE102 (containing the flaA 5′ UTR translationally linked to astA, under control of the lac promoter) to introduce a SalI site upstream of the lac promoter for subcloning purposes. The SalI fragment of pFE102 was then ligated with SalI-digested pACYC184 to yield pJOFE (Table 1). E. coli BL21(DE3) cells were transformed with pJOFE and pET-20b expressing WT CsrA, CsrA with the aforementioned point mutations, or pET-20b alone (negative control). Expression of AstA from the translational reporter was assessed in two ways. Plates used to recover transformed cells contained 50 μg/ml of arylsulfatase substrate (5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl sulfate potassium salt; Millipore-Sigma, St. Louis, MO). The intensity of blue color of colonies on these plates reflected the degree of AstA expression. To quantify AstA activity, we used an arylsulfatase assay (Hendrixson and DiRita, 2003). Briefly, this assay quantifies the AstA-mediated conversion of the substrate nitrophenylsulfate to nitrophenol, which is measured by absorbance at 410 nm. Results were analyzed using one-way ANOVA in GraphPad Prism (GraphPad Software, Inc.), with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test, using p < 0.05 to indicate significance. To verify expression of CsrA in E. coli, the samples used in the arylsulfatase assay were tested in western blots using CsrA-specific polyclonal antiserum (antibody dilution 1:1,000) (Fields et al., 2016). Experiments were done a minimum of three times, using triplicate samples.

Wild type and mutants of CsrA (L2A) and (A36V) with C-terminal His6-tag were overexpressed in E. coli BL21(DE3) pLysS cells. Cells were grown in LB broth at 37°C until they reached an OD600 of 0.6, and protein expression was subsequently induced with 0.5 mM IPTG and carried out at 20°C overnight. Cells were disrupted in extraction buffer (50 mM Tris–HCl pH 8.5, 1 M NaCl, 20 mM imidazole, 10% glycerol) with a French press (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The lysate was cleared by centrifugation (15,000 × g) and mixed with Ni-NTA chromatography resin (Ni-NTA Agarose, Qiagen). After protein binding (1 h in 4°C), the resin was washed three times with 10 resin volumes of extraction buffer. The protein was eluted with 50 mM Tris–HCl, pH 8.5, 1 M NaCl, 250 mM imidazole, 10% glycerol, and dialyzed into 20 mM sodium phosphate pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl. The final CsrA protein sample was obtained by gel filtration on Superdex 75 10/300 column (GE Healthcare) in the same buffer.

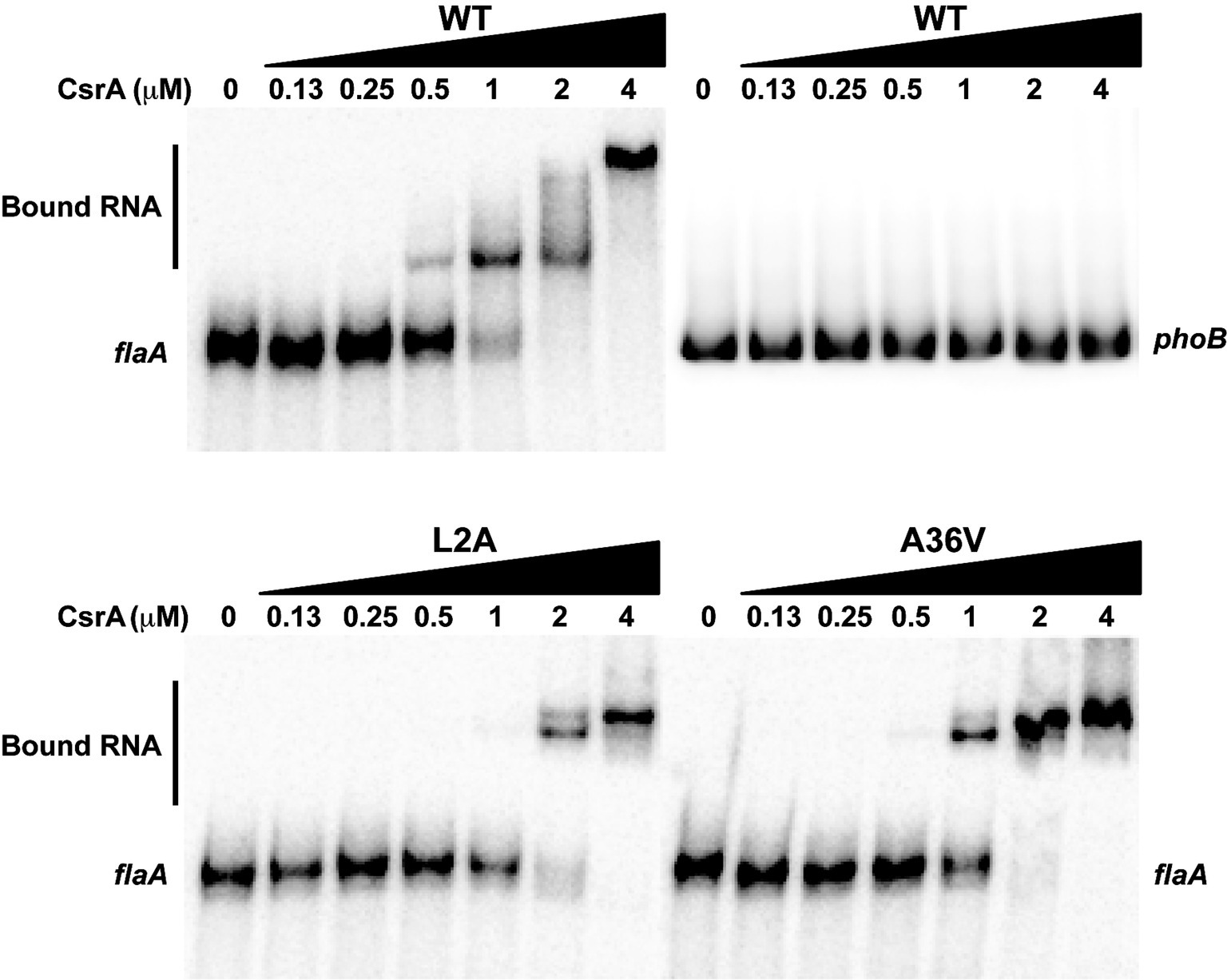

Electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) experiments were performed as described previously (Yakhnin et al., 2012; Fields et al., 2016), using purified C. jejuni CsrA(WT)-His6, CsrA(L2A)-His6, and CsrA(V36A)-His6. PCR using 81–176 chromosomal DNA and primers containing a T7 promoter sequence (Fields et al., 2016) was performed to generate flaA 5′ UTR DNA templates to be used for in vitro transcription. An E. coli phoB 5′ UTR DNA template was generated to be used as a CsrA-non-binding control, as described (Patterson-Fortin et al., 2013; Fields et al., 2016). RNA was synthesized using a MEGAscript™ T7 Transcription kit (Ambion), and purified via phenol:chloroform extraction. Purified RNAs were end-labeled with 32P using a KinaseMax™ 5′ End-Labeling kit (Ambion). Radiolabeled RNA at a concentration of 1 nM was then incubated with different concentrations (0–4 μM) of purified CsrA-His6 (WT, L2A or A36V) in binding reactions. Samples were resolved on 12% native polyacrylamide gels and visualized on a phosphorimager.

The consensus binding sequence of E. coli CsrA was determined previously and shown to be RU

Figure 1. Identification of high-affinity RNA ligands for C. jejuni CsrA using in vitro SELEX. A complex mixture of oligonucleotides was designed containing PCR primers flanking a random N15 central region. RNAs transcribed in vitro from this mixture were bound to CsrA-His6, purified, converted to cDNA, then the enriched pool was subsequently used in a total of 10 rounds of SELEX. To monitor the progress of SELEX, gel shift assays were performed using increasing concentrations of purified CsrA-His6 and enriched RNAs from cycles 1, 3, 5, 8, and 10. Increased conversion of unbound RNA (“Free RNA”) to enriched CsrA-bound RNA ligands (“Bound RNA”) was visible in successive rounds of SELEX.

Figure 2. Alignment of SELEX-derived RNA templates. Following nine and ten cycles of enrichment, cDNAs corresponding to high-affinity C. jejuni CsrA RNA ligands were sequenced and aligned using Clustal Omega (Li et al., 2015) to generate the consensus binding sequence mAwGGAs. Gray shading indicates nucleotides present in every SELEX ligand.

Figure 3. Predicted secondary structures of representative SELEX-enriched CsrA-binding RNAs. Selected RNAs from SELEX were folded using MFOLD. RNAs 10–1 and 9–27 represent the majority of enriched RNAs, in which the AnGGA motif (blue shading) was present at the end of long stem-loops. In RNAs 10–6 and 9–13, the AnGGA motifs were present within the stems instead.

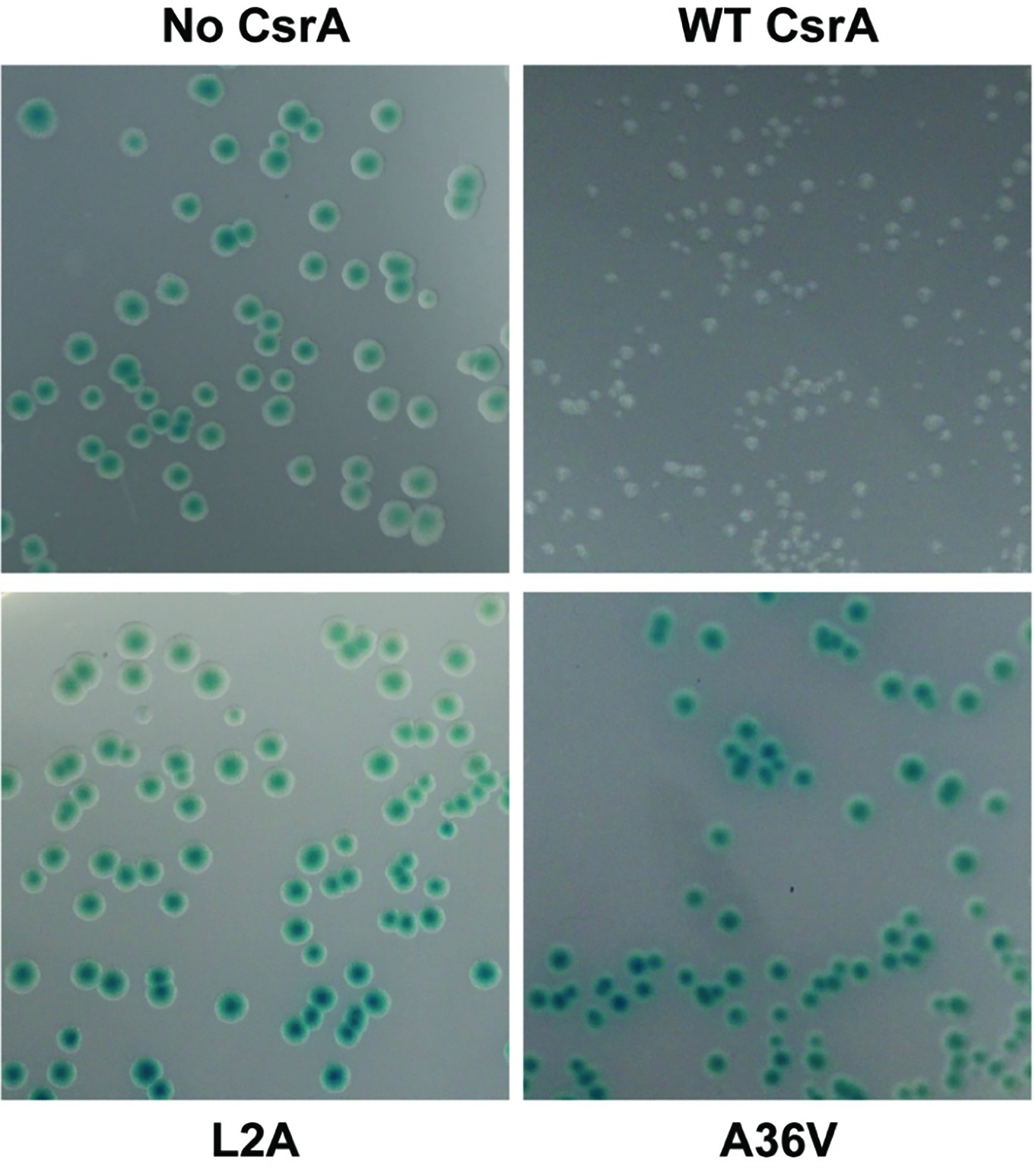

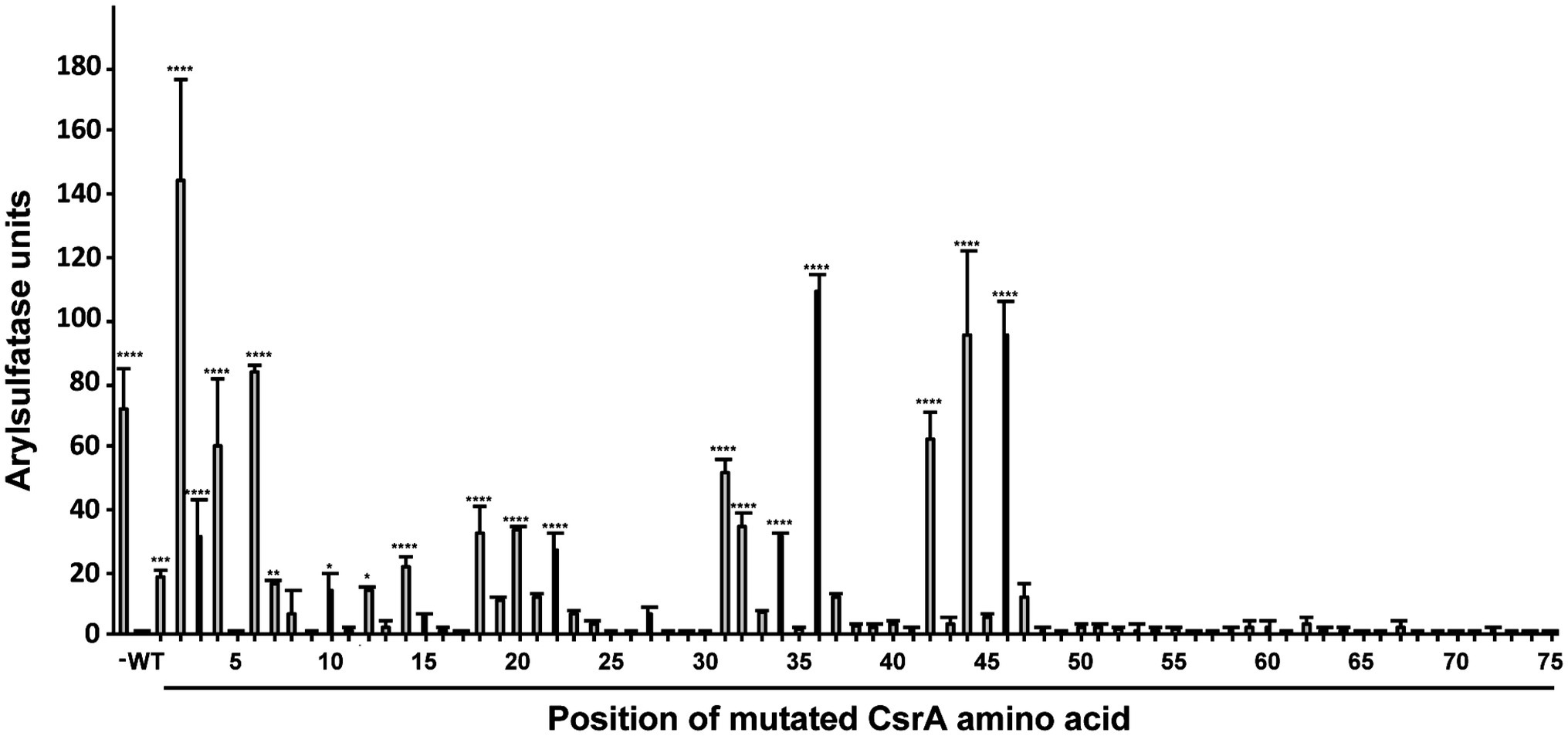

To determine the amino acids of CsrA involved in RNA binding, we constructed a translational reporter system. In this system, we cloned DNA encoding the 5′ UTR of flaA mRNA upstream of the C. jejuni reporter gene astA, under the control of the E. coli lac promoter (Figure 4). This translational reporter plasmid (pJOFE, Table 1) was co-expressed with the pET-20b alone (negative control), or containing either WT CsrA, or CsrA with 75 individual point mutations. In the absence of CsrA binding to the flaA 5′ UTR, AstA activity was high and generated blue colonies (Figure 5, top left, and Figure 6). However, when WT CsrA bound the flaA 5′ UTR it greatly repressed AstA expression, resulting in white colonies and low AstA activity (Figure 5, top right, and Figure 6). The colors of colonies expressing CsrA mutants with individual point mutations ranged from light blue to dark blue, indicating qualitatively varying degrees of CsrA activity in binding the flaA 5′ UTR (Figure 5, bottom panels, and Supplementary Figure S2).

Figure 4. Schematic of translational reporter construct pJOFE. The C. jejuni reporter gene astA was cloned downstream of DNA encoding the flaA 5′ UTR to create a translational fusion under the control of the E. coli lac promoter, then the construct was cloned into pACYC184 to yield pJOFE. The 5′ UTR of flaA is predicted to fold into two stem-loops with two CsrA-binding sites containing the A(U/A)GGA motif.

Figure 5. Repression of AstA translational fusion by WT and mutant CsrA proteins. E. coli BL21(DE3) was co-transformed with the translational reporter pJOFE (encoding the flaA 5′ UTR translationally linked to astA, under control of the lac promoter) and either: pET-20b (“No CsrA”, top left panel), pET-20b-CsrA (“WT CsrA”, top right panel), pET-20b- CsrA-L2A (“L2A”, bottom left panel), or pET-20b-CsrA-A36V (“A36V”, bottom right panel), and plated on LB plates containing 50 μg/ml of arylsulfatase substrate. The intensity of the blue color of the colonies indicates AstA enzyme activity and lack of CsrA regulatory activity. Experiments were done a minimum of three times, using triplicate samples.

Figure 6. Quantification of regulatory activity by WT and mutant CsrA proteins. E. coli BL21(DE3) was co-transformed with the translational reporter pJOFE and either: pET-20b (negative control, labeled “−”), pET-20b-CsrA (positive control, labeled “WT”), or each of the 75 pET-20b-CsrA point mutants. AstA activity in these cells was quantified by arylsulfatase assay (Y axis). The positions of CsrA mutations are indicated below the X axis. Experiments were done a minimum of three times, using triplicate samples. Results were analyzed using one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test, using p < 0.05 to indicate significance. ****p < 0.0001, ***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05.

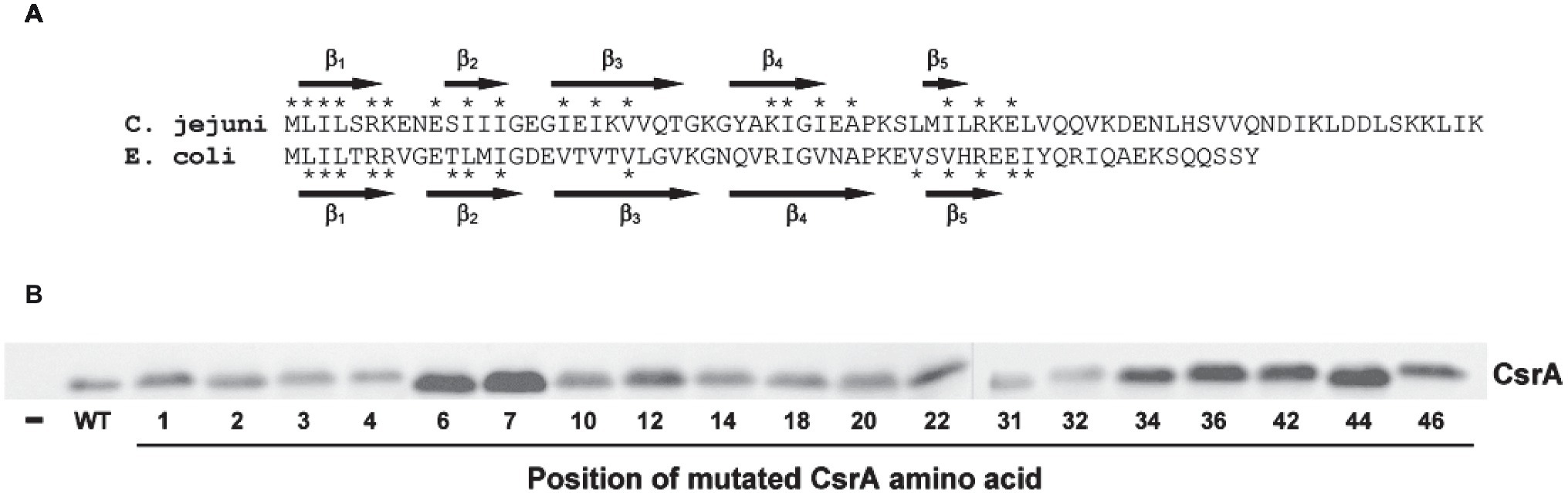

To quantify the degree of CsrA repression of AstA, arylsulfatase assays (Hendrixson and DiRita, 2003) were performed on colonies collected from agar plates (Figure 5). Consistent with plate results, 56 of the 75 site-directed mutants of CsrA exhibited no significant difference in reporter activity compared to WT CsrA (Figure 6). However, CsrA proteins with mutations in 19 amino acids (M1A, L2A, I3A, L4A, R6A, K7A, E10A, I12A, I14A, I18A, I20A, V22A, K31A, I32A, I34A, A36V, I42A, R44A, and E46A) showed significant increases in pJOFE reporter activity, reflecting a decrease in CsrA RNA binding to the flaA 5′ UTR (p < 0.05) (Figure 6). The amino acid mutations that showed the highest AstA activity were (in decreasing order) L2A, A36V, R44A, E46A, R6A, L4A and I42A (p < 0.0001). Most of the detected 19 amino acids were clustered in the five β strands of CsrA predicted by BETApro (Figure 7A; Cheng and Baldi, 2005). We note that some of these CsrA mutations could result in altered CsrA protein structure or potentially non-specific effects on the E. coli cells that might affect reporter activity. It was important to exclude the possibility that the site-directed mutants that showed high AstA activity had simply lost CsrA expression, thus we tested the expression of CsrA in the samples used in the arylsulfatase assay by western blot. The expression level of WT CsrA (Figure 7B) was sufficient to give near complete repression of AstA (Figure 6). Although the expression levels of mutant CsrA proteins varied, each of the 19 mutants with high AstA activity had CsrA expression at levels similar to or higher than that of WT (Figure 7B). This indicates that higher reporter activity was not due to poor expression of mutant CsrA proteins.

Figure 7. RNA-binding amino acids and expression of CsrA. (A) Sequence alignment of C. jejuni and E. coli CsrA proteins. Proteins were aligned using Clustal Omega (Li et al., 2015), and the location of β strands β1-β5 were predicted using BETApro (Cheng and Baldi, 2005). Asterisks indicate amino acids involved in RNA binding by the adjacent protein. E. coli data were taken from Mercante et al. (2006). (B) Expression of C. jejuni CsrA proteins in E. coli containing pJOFE. E. coli cells transformed with the translational reporter pJOFE and pET-20b (“−”), pET-20b-CsrA (“WT”), or the 19 CsrA point mutants that showed significantly higher AstA activity were tested in western blots using CsrA-specific polyclonal antiserum (Fields et al., 2016). All CsrA mutant proteins were expressed at levels equivalent to or higher than WT.

CsrA mutations L2A and A36V showed the most significant loss of CsrA regulatory activity on flaA 5′ UTR. To confirm that these CsrA mutants had lost their ability to bind flaA mRNA, EMSA was performed using labeled flaA 5′ UTR mRNA and different concentrations (0–4 μM) of purified CsrA-His6 (WT, L2A or A36V). Labeled E. coli phoB 5′ UTR mRNA was used as a CsrA-non-binding control (Patterson-Fortin et al., 2013; Fields et al., 2016). As seen previously (Fields et al., 2016), CsrA WT bound the flaA 5′ UTR with shifted species seen at a CsrA concentration as low as of 0.25 μM (Figure 8). Shifts with L2A and A36V occurred only at higher concentrations of the protein, 1 and 0.5 μM, respectively (Figure 8).

Figure 8. RNA-binding ability of CsrA mutants assessed using EMSA. Purified CsrA-His6 proteins (WT, L2A, and A36V) were incubated at different protein concentrations (0–4 μM) with 32P-labeled flaA mRNA (1 nM), resolved on 12% native polyacrylamide gels, and visualized by a phosphorimager. RNA binding by CsrA resulted in decreased migration of the RNA (“Bound RNA”). Labeled E. coli phoB 5′ UTR mRNA was used as a CsrA-non-binding control.

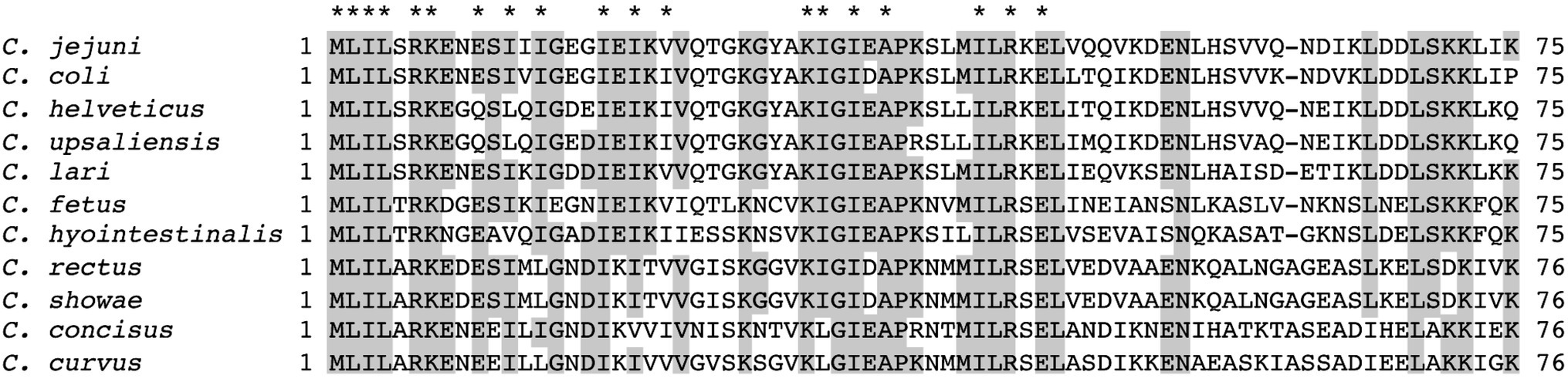

To determine whether the amino acids that were identified as important for the binding of C. jejuni CsrA to flaA mRNA were conserved among members of the Campylobacter genus, we used Clustal Omega (Sievers et al., 2011) to align CsrA proteins from 11 different Campylobacter species (Figure 9). Of the 19 CsrA amino acids that had a role in binding flaA RNA, 13 were identical among all Campylobacter species examined (M1, L2, I3, L4, R6, K7, I18, K31, I34, A36, I42, R44, and E46), with an additional five showing conservative substitutions among the different species (I12, I14, I20, V22, and I32) (Figure 9).

Figure 9. Alignment of CsrA proteins from 11 Campylobacter species. CsrA proteins (75 or 76 amino acids in length) from 11 representative Campylobacter species were aligned using Clustal Omega (Li et al., 2015). Amino acids that are identical in at least 7 of 11 orthologs are shaded gray. The amino acids identified as having roles in RNA binding by C. jejuni CsrA are indicated above the alignment by asterisks and are highly conserved among Campylobacter CsrA proteins.

Post-transcriptional control of protein expression by the RNA-binding regulator CsrA is reported in many bacterial species including the gastrointestinal pathogen C. jejuni (Fields et al., 2016; Li et al., 2018; Romeo and Babitzke, 2018). CsrA binds target mRNAs and alters their translation or stability (Romeo and Babitzke, 2018). The flagellar protein FlaA is a well-established target of C. jejuni CsrA regulation (Dugar et al., 2016; Fields et al., 2016; Radomska et al., 2016). Flagella are considered a major virulence factor in C. jejuni, and the extensive transcriptional and post-transcriptional regulation of C. jejuni flagellar synthesis ensures proper biosynthesis of flagella (Lertsethtakarn et al., 2011). Furthermore, FlaA is one the most abundant proteins in the cell and flagellar synthesis is energetically costly, so tight regulation of its synthesis is necessary from a metabolic standpoint. The growth-phase dependent regulation of flagellin synthesis (Fields et al., 2016; Li et al., 2018) also suggests that the timing of flagellar assembly could be critical for colonization and pathogenesis. In this study, we used purified C. jejuni CsrA to examine CsrA-RNA interactions, using both affinity-selected RNA ligands and C. jejuni flaA mRNA as targets.

To begin to understand the mechanisms underlying CsrA-RNA interactions, we first determined high-affinity RNA ligands that are recognized by CsrA. A previous RIP-Seq study identified C. jejuni CsrA-binding sites by affinity purification of CsrA-binding RNAs from C. jejuni cell lysates, with a consensus sequence of (C/A)A(A/U)GGA found in the loops of stem-loops (Dugar et al., 2016). However, in that study, the presumptive CsrA regulon was composed primarily of FlaA and other flagellar proteins. Because the mRNA encoding FlaA is one of the most abundant transcripts in C. jejuni (Dugar et al., 2013), the possibility existed that the CsrA-binding site in that study was heavily influenced by enrichment of transcripts encoding flaA and related motility proteins. Since our previous results indicated a much more extensive presumptive CsrA regulon, we chose to use the independent in vitro SELEX method for defining the CsrA-binding site. Using SELEX, from a pool of randomized RNA oligonucleotides, we selected an enriched pool of RNA ligands that bind C. jejuni CsrA with high affinity (Figure 1). The consensus RNA sequence to which C. jejuni CsrA binds is m

The C. jejuni CsrA-binding site is similar, but not identical, to the consensus high-affinity RNA-binding site for E. coli CsrA, which is RUAC

Because C. jejuni CsrA is rather divergent in amino acid sequence from that of E. coli (24% identical/52% similar), our next goal was to determine the amino acids of C. jejuni CsrA that are important for RNA binding. To achieve this, we constructed a translational reporter system (pJOFE) in which the C. jejuni reporter gene astA was cloned downstream of DNA encoding the flaA 5′ UTR, under the control of the E. coli lac promoter (Figure 4). In the absence of C. jejuni CsrA expressed from a compatible vector, E. coli cells containing pJOFE appear as large blue colonies (Figure 5, Supplementary Figure S2). When WT CsrA is co-expressed with pJOFE, it binds the flaA 5′ UTR and represses the expression of AstA, resulting in small white colonies. It is worth mentioning that E. coli colonies with expression of a functional C. jejuni CsrA protein are consistently smaller than those not expressing a functional protein, suggesting that C. jejuni CsrA is also able to regulate proteins in E. coli BL21(DE3) that affect E. coli colony size (Figure 5 and data not shown). We next constructed site-directed mutants of each of the 75 amino acids of C. jejuni CsrA and tested them for their ability to repress AstA activity from pJOFE, using both qualitative plate and quantitative enzymatic assays. Mutations of CsrA that do not significantly affect CsrA-RNA interaction (56 of 75 mutants in total) give the same results as WT CsrA, appearing on plates as small white colonies, with low AstA enzymatic activity (Figures 5, 6, and data not shown). In contrast, we identified 19 amino acids presumptively involved in CsrA-RNA interaction, yielding large blue colonies similar to the vector control (Figure 5, Supplementary Figure S2). As expected, these mutants all had significantly higher AstA enzymatic activity than WT (Figure 6). Interestingly, the AstA activities of E. coli containing the L2A, A36V, R44A, and E46A mutants are somewhat higher than that of cells not expressing C. jejuni CsrA. It is possible that these mutants have a non-specific effect on E. coli phenotypes related to transcription or translation, as some of these factors are known targets of E. coli CsrA (Edwards et al., 2011) and possibly C. jejuni CsrA (Fields and Thompson, 2012). These mutants may still bind flaA mRNA with reduced affinity compared to WT (Figure 8). However, it is possible that they bind with an altered specificity, for example to the upstream of the two CsrA-binding sites of the flaA 5′ UTR (Figure 4) rather than the downstream site that contains the RBS. This could result in stabilization of the mRNA and increased translation. This mechanism of CsrA activation of expression is reported in other bacteria (Patterson-Fortin et al., 2013; Yakhnin et al., 2013; Ren et al., 2014; Romeo and Babitzke, 2018).

Of the 19 identified amino acids, 11 were at positions previously identified as important for the regulatory activity of E. coli CsrA (Mercante et al., 2006). These amino acids tended to cluster within the five predicted β strands of CsrA, with the most significant amino acids present in or near the β1 and β5 strands (Figure 7A). In known structures of CsrA orthologs, these two β strands form an edge of inter-subunit β-sheet (Gutierrez et al., 2005; Rife et al., 2005; Heeb et al., 2006), where CsrA binds its target mRNA (Schubert et al., 2007). In C. jejuni CsrA, L2A shows the greatest loss in regulatory activity based on results from both arylsulfatase assay and EMSA gel shifts, followed by A36V, R44A, E46A, R6A, L4A, and I42A. This is somewhat different than in E. coli, in which the CsrA mutants that had the strongest RNA-binding phenotypes were (in decreasing order) R44A, V42A, L2A, I47A, V40A, L4A, R6A, and R7A (Mercante et al., 2006). While C. jejuni CsrA mutant I42A shows significantly reduced regulatory activity, the phenotype is not as strong as the analogous mutation in E. coli CsrA. Amino acid R44 is a significant residue for CsrA-RNA interaction in Yersinia enterocolitica (Heeb et al., 2006), while in Pseudomonas fluorescens mutation of R44 and L4 causes loss of RsmE (CsrA) ability to repress its target mRNA (Schubert et al., 2007). While the reduced regulatory activity of the C. jejuni CsrA mutants is likely due to the importance of the mutated amino acids in RNA interactions, it is also possible that some of the mutations affect overall CsrA protein structure, although the use of alanine as the substituted amino acid is a standard approach to minimize such disruptions. The secondary structure of the CsrA mutant proteins was predicted using two different programs [BETApro and PredictProtein (not shown)], and β strands were present in all of the mutant proteins. However, the two programs made slightly different predictions, with some subtle variations in β strand locations. Thus, without an experimentally determined structure of CsrA, predicted secondary structures of the mutants cannot be confirmed. Furthermore, we cannot exclude potential non-specific effects of the mutations on E. coli as described above.

The nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) structure of CsrA ortholog from P. fluorescens (RsmE) complexed to a target mRNA indicates that RNA-binding surfaces are highly positively charged and formed by the aforementioned edges of β-sheets composed of the β1 and β5 strands of the opposite subunits of the dimer and the regions around the β3-β4 and β4-β5 loops (Schubert et al., 2007). The

To exclude the possibility that the mutants with reduced regulatory activity had lost CsrA expression, we performed western blots on the same samples used in the arylsulfatase assays and showed that each of the 19 CsrA mutants has expression levels similar to or higher than that of WT CsrA (Figure 7B). This confirms that the reduced regulatory activity of these mutants was due specifically to loss of protein functionality rather than poor CsrA expression. To confirm that reduced CsrA regulatory activity was due to altered RNA binding, we performed EMSA using purified proteins of the two most significant mutants (L2A and A36V) and radiolabeled flaA mRNA. These experiments showed decreased RNA binding by both mutants relative to WT (Figure 8), as shifts occurred only at higher concentrations of CsrA. The CsrA amino acids of C. jejuni detected in this study as being important for CsrA regulatory activity on flaA mRNA are highly conserved among 11 selected Campylobacter species, with 13 of the 19 amino acids being identical and five being conservative substitutions (Figure 9). Nine of the 19 identified amino acids (L2, R6, K7, I14, I18, A36, I42, R44, and E46) are also conserved in CsrA proteins from diverse bacterial species (Fields and Thompson, 2012).

Identification of the consensus CsrA-binding site and amino acids critical for CsrA binding to flaA mRNA serves as a model for studying C. jejuni CsrA interaction with other important target mRNAs. The findings of this study are also a precursor to fully understand the mechanism of antagonism of C. jejuni CsrA by the flagellar chaperone FliW. In B. subtilis, FliW inhibits CsrA RNA binding by a noncompetitive allosteric mechanism where FliW binds CsrA at a surface distinct from its RNA-binding pocket (Mukherjee et al., 2016). Ongoing studies by our group are exploring whether FliW antagonizes CsrA activity toward target mRNAs through direct competition for the CsrA RNA-binding site, by steric hindrance, or by a noncompetitive allosteric mechanism. In addition, understanding the mechanism by which CsrA regulates the expression of a major C. jejuni virulence factor (flagella) may allow the development of novel strategies to limit C. jejuni infection.

The datasets generated for this study are available on request to the corresponding author.

FE, JL, HO, CD, CF, MB, and ST contributed to the conception and design of the study. FE performed the statistical analysis and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. FE, MB, and ST wrote sections of the manuscript. All authors contributed to manuscript revision, read and approved the submitted version.

The research described in this manuscript was funded by US National Institutes of Health grants 5R01AI103267 and 1R56AI084160, and an Intramural Grant from Augusta University (all to ST).

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

We gratefully acknowledge the Medical College of Georgia at Augusta University Medical Scholars Program for supporting HO.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmicb.2019.01776/full#supplementary-material

Altegoer, F., Rensing, S. A., and Bange, G. (2016). Structural basis for the CsrA-dependent modulation of translation initiation by an ancient regulatory protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 113, 10168–10173. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1602425113

Black, R. E., Levine, M. M., Clements, M. L., Hughes, T. P., and Blaser, M. J. (1988). Experimental Campylobacter jejuni infection in humans. J. Infect. Dis. 157, 472–479. doi: 10.1093/infdis/157.3.472

Champion, O. L., Gaunt, M. W., Gundogdu, O., Elmi, A., Witney, A. A., Hinds, J., et al. (2005). Comparative phylogenomics of the food-borne pathogen Campylobacter jejuni reveals genetic markers predictive of infection source. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 102, 16043–16048. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0503252102

Cheng, J., and Baldi, P. (2005). Three-stage prediction of protein beta-sheets by neural networks, alignments and graph algorithms. Bioinformatics 21(Suppl. 1), i75–i84. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti1004

Dubey, A. K., Baker, C. S., Romeo, T., and Babitzke, P. (2005). RNA sequence and secondary structure participate in high-affinity CsrA-RNA interaction. RNA 11, 1579–1587. doi: 10.1261/rna.2990205

Dugar, G., Herbig, A., Forstner, K. U., Heidrich, N., Reinhardt, R., Nieselt, K., et al. (2013). High-resolution transcriptome maps reveal strain-specific regulatory features of multiple Campylobacter jejuni isolates. PLoS Genet. 9:e1003495. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003495

Dugar, G., Svensson, S. L., Bischler, T., Waldchen, S., Reinhardt, R., Sauer, M., et al. (2016). The CsrA-FliW network controls polar localization of the dual-function flagellin mRNA in Campylobacter jejuni. Nat. Commun. 7:11667. doi: 10.1038/ncomms11667

Edwards, A. N., Patterson-Fortin, L. M., Vakulskas, C. A., Mercante, J. W., Potrykus, K., Vinella, D., et al. (2011). Circuitry linking the Csr and stringent response global regulatory systems. Mol. Microbiol. 80, 1561–1580. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2011.07663.x

Fields, J. A., Li, J., Gulbronson, C. J., Hendrixson, D. R., and Thompson, S. A. (2016). Campylobacter jejuni CsrA regulates metabolic and virulence associated proteins and is necessary for mouse colonization. PLoS One 11:e0156932. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0156932

Fields, J. A., and Thompson, S. A. (2008). Campylobacter jejuni CsrA mediates oxidative stress responses, biofilm formation, and host cell invasion. J. Bacteriol. 190, 3411–3416. doi: 10.1128/JB.01928-07

Fields, J. A., and Thompson, S. A. (2012). Campylobacter jejuni CsrA complements an Escherichia coli csrA mutation for the regulation of biofilm formation, motility and cellular morphology but not glycogen accumulation. BMC Microbiol. 12:233. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-12-233

Freitag, C. M., Strijbis, K., and van Putten, J. P. M. (2017). Host cell binding of the flagellar tip protein of Campylobacter jejuni. Cell. Microbiol. 19, 1–13. doi: 10.1111/cmi.12714

Guerry, P. (2007). Campylobacter flagella: not just for motility. Trends Microbiol. 15, 456–461. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2007.09.006

Gutierrez, P., Li, Y., Osborne, M. J., Pomerantseva, E., Liu, Q., and Gehring, K. (2005). Solution structure of the carbon storage regulator protein CsrA from Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 187, 3496–3501. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.10.3496-3501.2005

Heeb, S., Kuehne, S. A., Bycroft, M., Crivii, S., Allen, M. D., Haas, D., et al. (2006). Functional analysis of the post-transcriptional regulator RsmA reveals a novel RNA-binding site. J. Mol. Biol. 355, 1026–1036. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.11.045

Hendrixson, D. R., and DiRita, V. J. (2003). Transcription of σ54-dependent but not σ28-dependent flagellar genes in Campylobacter jejuni is associated with formation of the flagellar secretory apparatus. Mol. Microbiol. 50, 687–702. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03731.x

Kaakoush, N. O., Castano-Rodriguez, N., Mitchell, H. M., and Man, S. M. (2015). Global epidemiology of Campylobacter infection. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 28, 687–720. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00006-15

Konkel, M. E., Kim, B. J., Rivera-Amill, V., and Garvis, S. G. (1999). Bacterial secreted proteins are required for the internalization of Campylobacter jejuni into cultured mammalian cells. Mol. Microbiol. 32, 691–701. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01376.x

Lertsethtakarn, P., Ottemann, K. M., and Hendrixson, D. R. (2011). Motility and chemotaxis in Campylobacter and Helicobacter. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 65, 389–410. doi: 10.1146/annurev-micro-090110-102908

Li, W., Cowley, A., Uludag, M., Gur, T., McWilliam, H., Squizzato, S., et al. (2015). The EMBL-EBI bioinformatics web and programmatic tools framework. Nucleic Acids Res. 43, W580–W584. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv279

Li, J., Gulbronson, C. J., Bogacz, M., Hendrixson, D. R., and Thompson, S. A. (2018). FliW controls growth-phase expression of Campylobacter jejuni flagellar and non-flagellar proteins via the post-transcriptional regulator CsrA. Microbiology 164, 1308–1319. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.000704

Mercante, J., Edwards, A. N., Dubey, A. K., Babitzke, P., and Romeo, T. (2009). Molecular geometry of CsrA (RsmA) binding to RNA and its implications for regulated expression. J. Mol. Biol. 392, 511–528. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2009.07.034

Mercante, J., Suzuki, K., Cheng, X., Babitzke, P., and Romeo, T. (2006). Comprehensive alanine-scanning mutagenesis of Escherichia coli CsrA defines two subdomains of critical functional importance. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 31832–31842. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M606057200

Morris, E. R., Hall, G., Li, C., Heeb, S., Kulkarni, R. V., Lovelock, L., et al. (2013). Structural rearrangement in an RsmA/CsrA ortholog of Pseudomonas aeruginosa creates a dimeric RNA-binding protein, RsmN. Structure 21, 1659–1671. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2013.07.007

Mukherjee, S., Oshiro, R. T., Yakhnin, H., Babitzke, P., and Kearns, D. B. (2016). FliW antagonizes CsrA RNA binding by a noncompetitive allosteric mechanism. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 113, 9870–9875. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1602455113

Mukherjee, S., Yakhnin, H., Kysela, D., Sokoloski, J., Babitzke, P., and Kearns, D. B. (2011). CsrA-FliW interaction governs flagellin homeostasis and a checkpoint on flagellar morphogenesis in Bacillus subtilis. Mol. Microbiol. 82, 447–461. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2011.07822.x

Nachamkin, I., Allos, B. M., and Ho, T. W. (2000). “Campylobacter jejuni infection and the association with Guillain-Barré syndrome” in Campylobacter. 2nd Edn. eds. I. Nachamkin and M. J. Blaser (Washington, DC: ASM Press), 155–175.

Patterson-Fortin, L. M., Vakulskas, C. A., Yakhnin, H., Babitzke, P., and Romeo, T. (2013). Dual posttranscriptional regulation via a cofactor-responsive mRNA leader. J. Mol. Biol. 425, 3662–3677. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2012.12.010

Radomska, K. A., Ordonez, S. R., Wosten, M. M., Wagenaar, J. A., and van Putten, J. P. (2016). Feedback control of Campylobacter jejuni flagellin levels through reciprocal binding of FliW to flagellin and the global regulator CsrA. Mol. Microbiol. 102, 207–220. doi: 10.1111/mmi.13455

Ren, B., Shen, H., Lu, Z. J., Liu, H., and Xu, Y. (2014). The phzA2-G2 transcript exhibits direct RsmA-mediated activation in Pseudomonas aeruginosa M18. PLoS One 9:e89653. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0089653

Rife, C., Schwarzenbacher, R., McMullan, D., Abdubek, P., Ambing, E., Axelrod, H., et al. (2005). Crystal structure of the global regulatory protein CsrA from pseudomonas putida at 2.05 A resolution reveals a new fold. Proteins 61, 449–453. doi: 10.1002/prot.20502

Romeo, T., and Babitzke, P. (2018). Global regulation by CsrA and its RNA antagonists. Microbiol. Spectr. 6, 1–24. doi: 10.1128/microbiolspec.RWR-0009-2017

Romeo, T., Vakulskas, C. A., and Babitzke, P. (2013). Post-transcriptional regulation on a global scale: form and function of Csr/Rsm systems. Environ. Microbiol. 15, 313–324. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2012.02794.x

Schubert, M., Lapouge, K., Duss, O., Oberstrass, F. C., Jelesarov, I., Haas, D., et al. (2007). Molecular basis of messenger RNA recognition by the specific bacterial repressing clamp RsmA/CsrA. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 14, 807–813. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1285

Sievers, F., Wilm, A., Dineen, D., Gibson, T. J., Karplus, K., Li, W., et al. (2011). Fast, scalable generation of high-quality protein multiple sequence alignments using Clustal Omega. Mol. Syst. Biol. 7:539. doi: 10.1038/msb.2011.75

Svensson, S. L., Pryjma, M., and Gaynor, E. C. (2014). Flagella-mediated adhesion and extracellular DNA release contribute to biofilm formation and stress tolerance of Campylobacter jejuni. PLoS One 9:e106063. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0106063

Tack, D. M., Marder, E. P., Griffin, P. M., Cieslak, P. R., Dunn, J., Hurd, S., et al. (2019). Preliminary incidence and trends of infections with pathogens transmitted commonly through food - Foodborne Diseases Active Surveillance Network, 10 U.S. Sites, 2015–2018. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly Rep. 68, 369–373. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6816a2

Tuerk, C., and Gold, L. (1990). Systematic evolution of ligands by exponential enrichment: RNA ligands to bacteriophage T4 DNA polymerase. Science 249, 505–510. doi: 10.1126/science.2200121

Wassenaar, T. M., van der Zeijst, B. A., Ayling, R., and Newell, D. G. (1993). Colonization of chicks by motility mutants of Campylobacter jejuni demonstrates the importance of flagellin A expression. J. Gen. Microbiol. 139, 1171–1175. doi: 10.1099/00221287-139-6-1171

WHO (2013). The global view of campylobacteriosis. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization, 1–59. https://www.who.int/foodsafety/publications/campylobacteriosis/en/

WHO (2015). WHO estimates of the global burden of foodborne diseases: Foodborne disease burden epidemiology reference group 2007–2015. Geneva, Switzerland: Publications of the World Health Organization.

Yakhnin, A. V., Baker, C. S., Vakulskas, C. A., Yakhnin, H., Berezin, I., Romeo, T., et al. (2013). CsrA activates flhDC expression by protecting flhDC mRNA from RNase E-mediated cleavage. Mol. Microbiol. 87, 851–866. doi: 10.1111/mmi.12136

Yakhnin, A. V., Yakhnin, H., and Babitzke, P. (2012). Gel mobility shift assays to detect protein-RNA interactions. Methods Mol. Biol. 905, 201–211. doi: 10.1007/978-1-61779-949-5_12

Yao, R., and Guerry, P. (1996). Molecular cloning and site-specific mutagenesis of a gene involved in arylsulfatase production in Campylobacter jejuni. J. Bacteriol. 178, 3335–3338. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.11.3335-3338.1996

Keywords: motility, flagella, biofilm, regulation, flagellin

Citation: El Abbar FM, Li J, Owen HC, Daugherty CL, Fulmer CA, Bogacz M and Thompson SA (2019) RNA Binding by the Campylobacter jejuni Post-transcriptional Regulator CsrA. Front. Microbiol. 10:1776. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2019.01776

Received: 13 June 2019; Accepted: 18 July 2019;

Published: 07 August 2019.

Edited by:

Xihui Shen, Northwest A&F University, ChinaReviewed by:

Marguerite Clyne, University College Dublin, IrelandCopyright © 2019 El Abbar, Li, Owen, Daugherty, Fulmer, Bogacz and Thompson. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Stuart A. Thompson, c3R0aG9tcHNAYXVndXN0YS5lZHU=

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.