- 1Department of Biological Sciences, Idaho State University, Pocatello, ID, United States

- 2Idaho National Laboratory, Idaho Falls, ID, United States

- 3California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, CA, United States

- 4Savannah River Ecology Laboratory, University of Georgia, Aiken, SC, United States

- 5Department of Biology, Point Loma Nazarene University, San Diego, CA, United States

The capability of microorganisms to alter metal speciation offers potential for the development of new strategies for immobilization of toxic metals in the environment. A metal-reducing microbe, “Pelosinus lilae” strain UFO1, was isolated under strictly anaerobic conditions from an Fe(III)-reducing enrichment established with uncontaminated soil from the Department of Energy Oak Ridge Field Research Center, Tennessee. “P. lilae” UFO1 is a rod-shaped, spore-forming, and Gram-variable anaerobe with a fermentative metabolism. It is capable of reducing the humic acid analog anthraquinone-2,6-disulfonate (AQDS) using a variety of fermentable substrates and H2. Reduction of Fe(III)-nitrilotriacetic acid occurred in the presence of lactate as carbon and electron donor. Ferrihydrite was not reduced in the absence of AQDS. Nearly complete reduction of 1, 3, and 5 ppm Cr(VI) occurred within 24 h in suspensions containing 108 cells mL−1 when provided with 10 mM lactate; when 1 mM AQDS was added, 3 and 5 ppm Cr(VI) were reduced to 0.1 ppm within 2 h. Strain UFO1 is a novel species within the bacterial genus Pelosinus, having 98.16% 16S rRNA gene sequence similarity with the most closely related described species, Pelosinus fermentans R7T. The G+C content of the genomic DNA was 38 mol%, and DNA-DNA hybridization of “P. lilae” UFO1 against P. fermentans R7T indicated an average 16.8% DNA-DNA similarity. The unique phylogenetic, physiologic, and metal-transforming characteristics of “P. lilae” UFO1 reveal it is a novel isolate of the described genus Pelosinus.

Introduction

The pollution of groundwater by metal and radionuclide contaminants continues to pose a clear threat to public health (EPA, 2003), and remediation of subsurface environments is a growing environmental and economic challenge (White et al., 1997; NABIR, 2003). In the United States, the Department of Energy (DOE) has generated 6.4 trillion L of contaminated groundwater in 5700 distinct plumes and 40 million m3 of contaminated soil and subsurface environs as a result of Cold War era nuclear weapons production (USDOE, 1997). After petroleum fuel and chlorinated hydrocarbons, metals and radionuclides (lead, chromium, arsenic, uranium, strontium-90, and tritium) represent the most common contaminants found in soils and groundwater at DOE facilities (Riley et al., 1992). Moreover, metallic and radioactive contaminants cannot be biodegraded and often prove to be the most challenging of hazardous wastes at DOE sites (NABIR, 2003).

In contrast to organic contaminants that may be completely oxidized to carbon dioxide and water, remediation of metals is more problematic, owing to the fact that the metals cannot be destroyed, and changes in their oxidation or reduction potential often dictate their ultimate environmental fate (Lovley and Lloyd, 2000). Generally, the goal of metal remediation is to limit contaminant mobility. The potential for immobilization of a given metal in the environment is principally dependent upon its chemical speciation. Thus, the aim is to either induce or maintain chemical conditions that result in metal species with reduced mobility. Depending on the ambient redox conditions, many toxic metals and radionuclides can be highly soluble, and thus mobile, in groundwater (Lovley, 2001). Microorganisms are capable of altering chemical speciation via redox reactions, thereby influencing solubility, transport properties, and bioavailability of metallic contaminants in subsurface environments. For example, bioreduction of highly soluble Cr(VI) and U(VI) can result in conversion to insoluble species [e.g., Cr(III) and U(IV)] that precipitate from solution (Tabak et al., 2005).

Microbial Fe(III) reduction is an important environmental process, and many Fe(III)-reducing bacteria have been found to also reduce high-valence metal contaminants (Lloyd, 2003). In addition, Fe(III)-reducing bacteria have been shown to utilize humic acids and synthetic electron-shuttling moieties, such as anthraquinone-2,6-disulfonate (AQDS), as electron acceptors (Lovley et al., 1996; Scott et al., 1998), which in turn can mediate the indirect reduction of Fe(III) and other metals (Lovley et al., 1998; Fredrickson et al., 2000; Nevin and Lovley, 2000). The physiologic diversity of electron transport to ferruginous mineral substrates are distributed into distinct groups of Fe(III)-reducing microorganisms. One group consists of the respiratory Fe(III)-reducers, in which reduction occurs via an electron transfer event coupled to energy generation. Representatives of this group include well-characterized organisms such as Geobacter spp., and Shewanella spp. (Lovley et al., 1987, 1989, 1993; Caccavo et al., 1992, 1994, 1996). The second group includes fermentative microorganisms that use humic acids and Fe(III)-bearing minerals as an electron sink for excess reducing power formed during fermentative metabolism (Benz et al., 1998; Borch et al., 2005; Shelobolina et al., 2007). Although these organisms have been detected in a variety of habitats where Fe(III) reduction is an important ecophysiological process (Kappler et al., 2004), this group is less well understood physiologically and phylogenetically. Recent studies on isolated members of the genus Pelosinus reveals novel mechanisms for metal sequestration and transformation (Beller et al., 2013; Thorgersen et al., 2017), and exhibit unique phylogenomic traits such as multiple, distinct copies of 16S rRNA genes (Ray et al., 2010), potentially confounding phylogenetic analysis of this group common in subsurface environments. Thus, examining new representatives of this group contributes to a broader understanding of the organisms involved in the biotransformation of metals in subsurface environments.

In situ biological treatment can be less expensive and less disruptive than traditional ex situ technologies for remediation of metal-contaminated sites, as it relies on indigenous microorganisms to achieve clean-up of hazardous wastes (NABIR, 2003). Examination of the biological potential for metal reduction among native microorganisms is important for implementation of successful remediation strategies. However, little is known about the potential for fermentative, Fe(III)-reducing subsurface microorganisms to play a role in metal bioremediation. Our goal was to isolate and characterize one such organism from a field study area adjacent to a metals-contaminated environment and evaluate its potential for metal bioremediation. Here, we describe “Pelosinus lilae” UFO1, isolated from the background or “pristine” area at the Oak Ridge Field Research Center (ORFRC), Tennessee. The unique phylogenetic and metal-transforming characteristics of “P. lilae” UFO1 reveal it is a novel species of the described genus designated Pelosinus.

Materials and Methods

Enrichment and Isolation of Strain UFO1

Strict anaerobic techniques were used throughout this study (Miller and Wolin, 1974; Balch and Wolfe, 1976). Sediment cores from the Field Research Center in Oak Ridge, TN, United States were taken from background well 330, section 02-22 (FWB 330-02-22), at a depth of 0.61–1.12 m below the surface. The groundwater pH was 6.13. Samples were shipped and stored in Mason jars under N2 and processed in an anaerobic glove bag under N2-CO2-H2 (75:20:5).

Enrichment cultures were initiated in 27 mL anaerobic pressure tubes (Bellco Glass) containing 9 mL anaerobic freshwater medium (ATCC medium 2129) and ∼1 g FRC sediment. A suspension of 2-line ferrihydrite (∼1 M) was synthesized by dissolving 40 g Fe(NO3)3⋅9H2O in 0.5 L water and adjusting to pH 7.0 with ∼345 mL 1 M KOH, and the resulting precipitate was washed thoroughly in DI water (Schwertmann and Cornell, 2000). The ferrihydrite was used as the terminal electron acceptor for enrichment cultures. Ferrihydrite (∼40 mM) was added to the tubes along with 10 mM acetate, and the tubes were incubated at room temperature. After 9 months, a 30 mM bicarbonate-buffered freshwater medium with 10 mM lactate, 5 mM AQDS as described by Finneran et al. (2002), and ∼20 mM ferrihydrite was used to prepare a dilution series from the iron-reducing culture. Aliquots were removed from the highest dilutions appearing positive for AQDS- and Fe(III)-reduction and streaked on plates of R2A agar (BD Difco™, Franklin Lakes, NJ, United States) supplemented with 20 mM fumarate in an anaerobic chamber. Distinct colonies were picked and re-streaked at least three times prior to transfer to liquid medium.

Routine Cultivation

After isolation, “P. lilae” UFO1 was routinely cultured in anoxic R2A broth and incubated at 30°C. R2A broth was prepared from a dry mix (BD Diagnostic Systems, Franklin Lakes, NJ, United States) or as follows (per liter): 0.5 g yeast extract; 0.5 g proteose peptone; 0.5 g casamino acids; 0.5 g glucose; 0.5 g soluble starch; 0.3 g sodium pyruvate; 0.3 g K2HPO4; 0.05 g MgSO4 (Reasoner and Geldreich, 1985), supplemented with 20 mM fumarate, and adjusted to pH 7. The R2A broth was boiled and cooled under a headspace of N2, dispensed into anaerobic pressure tubes or serum vials with a headspace of N2, sealed with thick butyl-rubber stoppers, and autoclaved. The effects of temperature, pH, and O2 on growth rates were evaluated using R2A broth (adjusted to acidic and alkaline pH where necessary).

Anaerobic, bicarbonate-buffered, freshwater (FW) medium was prepared, as described previously by Finneran et al. (2002) with or without 5 mM AQDS, and dispensed into anaerobic pressure tubes or serum vials under N2:CO2 (80:20). Tubes or vials were sealed with thick butyl-rubber stoppers and sterilized by autoclaving. FW medium was used for experiments examining electron donor and acceptor utilization.

Electron Donor and Acceptor Utilization Studies

Cells were harvested by centrifugation from cultures grown in R2A broth, washed twice in anoxic FW medium, and suspended in sterile, pH 7, anoxic FW medium. For screening of potential electron donors and acceptors, sterile anoxic stock solutions were prepared for a variety of electron donors and acceptors and added to the FW medium. Utilization was evaluated in triplicate incubations.

The ability of “P. lilae” UFO1 to reduce the following electron acceptors was examined: Fe(III)-NTA, 2 line-ferrihydrite, AQDS, Cr(VI), As(V), NO3-, NO2-, SO42-, and SeO42-. The ability of washed cell suspensions to reduce Cr(VI) was examined under non-growth conditions, defined here by the omission of phosphate from the FW medium. Washed cells were added to the medium to give a concentration of 108 cells mL-1.

Carbon substrate utilization by strain UFO1 was examined under anaerobic conditions using the BIOLOG® AN MicroPlate™ (Hayward, CA, United States) (Bochner, 1989). Anaerobic MicroPlates test the ability of a microorganism to utilize or oxidize an array of carbon sources under anaerobic conditions using an artificial tetrazolium colorimetric electron acceptor. A culture of strain UFO1 was grown for 24 h on R2A broth, pelleted and washed in anoxic FW medium, and suspended in the inoculating medium according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Microplates were inoculated in triplicate and incubated at 35°C for 24 h; wells exhibiting a color change due to the reduction of the tetrazolium dye as compared to the negative control (no carbon source) were considered positive for substrate utilization.

Potentially fermentable substrates were examined in FW medium (containing 0.5 mM cysteine as a reducing agent) in the absence of an electron acceptor. The following substrates (10 mM each) were tested: fructose, fumarate, glucose, glycerol, lactate, malate, mannitol, pyruvate, succinate, and 0.3% wt/vol. yeast extract. Fermentation of substrates was defined as the ability to grow after three successive 10% transfers, and growth was monitored by measuring optical density at 600 nm.

Analytical Techniques

AQDS and anthrahydroquinone-2,6-disulfonate (AH2DS) were measured spectrophotometrically at 405 and 325 nm under anoxic conditions. The molar absorptivity coefficients calculated for AQDS were 𝜀405 = 0.13 and 𝜀325 = 6.1 mM-1 cm-1; for AH2DS, the coefficients used were 𝜀405 = 10.3 and 𝜀325 = 0.8 mM-1 cm-1. Aqueous Fe(II) in sample filtrate (filtered through 0.2-μm filter) that was diluted 1:10 in 0.5 N HCl was quantified spectrophotometrically at 562 nm with ferrozine (Lovley and Phillips, 1987). Diphenylcarbazide reagent (Hach, Loveland, CO, United States) was used to quantify Cr(VI) at 540 nm. Ion chromatography (IC25 Ion Chromatograph Ion Pac-ATC-HC Trap Column) was used to measure NO3-, NO2-, SO42-, and SeO42-. Reduction of As(V) was evaluated by measuring soluble As(V) at 865 nm in samples preserved in KIO3 and HCl as described previously (Cummings et al., 1999).

X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) was employed to determine the valence state of Fe in cell suspensions incubated with 5 mM AQDS and 2 line-ferrihydrite or ferrihydrite alone. The extent of Fe(III)-reduction at both uncolonized and colonized Fe(III)-oxide surfaces was examined. Ferrihydrite samples were dried onto a Si wafer before mounting for XPS analysis. Samples were mounted for XPS in an anaerobic glove box and transported to the spectrometer in a plate chamber sealed under an anaerobic atmosphere. Brief (<5 s) exposure to air occurred during introduction of the samples into a N2-flushed antechamber. This antechamber was then evacuated and the sample placed into the spectrometer itself. Spectra were collected on a Perkin–Elmer Physical Electronics Division Model 5600ci spectrometer (Perkin–Elmer Inc., Eden Prairie, MN, United States). The spectrometer was calibrated employing the Au 4f7/2, Cu 2p3/2, and Ag 3d5/2 photopeaks with binding energies of 83.99, 932.66, and 368.27 eV, respectively. A consistent 400-μm spot size was analyzed on all surfaces using a monochromatized Al Kα (hν = 1486.6 eV) X-ray source at 300 W and a pass energy of 46.95 eV for survey scans, and 11.75 eV for high-resolution scans. The system was operated at a base pressure of 10-8 to 10-9 torr. An emission angle (2ϕ) of 45° was used throughout. Following baseline subtraction (Shirley, 1972), curve-fitting was employed using an 80% Gaussian: 20% Lorentzian line shape to estimate the contributions of ferrous and ferric ions to the total Fe photopeak (described below). A common problem associated with the analysis of insulating materials such as Fe(III)-oxides is the accumulation of surface charge during spectral collection leading to photopeak shifts; this was overcome by the use of a 5-eV flood gun and by referencing of the principal C 1 s photopeak [nominally due to carbon of the type (–CH2–CH2–)n] to a binding energy (Eb) of 284.8 eV (Swift, 1982).

Theoretical core p level models describing multiplet splitting associated with ferrous and ferric ions have been demonstrated by Gupta and Sen (Gupta and Sen, 1975) and empirical proofs substantiated by Pratt et al. (1994). Accordingly, ferric ion contributions were fit to high-resolution Fe 2p3/2 core regions with five peaks that decrease in intensity at increased Eb, with all peaks having the same line-shape. Ferrous ion contributions are represented by a major peak accompanied by a pair of multiplet peaks occurring 0.9 eV to either side of the major peak and a shake-up satellite at elevated Eb [ΔEb∼6 eV, (McIntyre and Zetaurk, 1977)]. The relative intensities of the Fe(II) peaks are consistent with the aforementioned models and have been applied elsewhere in the identification of reduced iron in the presence of microorganisms (Herbert et al., 1998; Neal et al., 2001, 2004; Magnuson et al., 2004).

DNA Base Composition and Cell Wall Analysis

Cells were grown overnight on R2A broth supplemented with 20 mM fumarate at 30°C and harvested by centrifugation. Cell pellets were suspended in a mixture of isopropanol and water (1:1). The G+C content of genomic DNA was determined by high-performance liquid chromatography using the method of Mesbah et al. (1989), and peptidoglycan was analyzed by the method of Schleifer and Kandler (1972). Both analyses were performed at Deutsche Sammlung von Mikroorganismen und Zellkulturen (DSMZ).

DNA–DNA Hybridization

Cells of “P. lilae” UFO1 were grown in anoxic R2A broth at 30°C overnight and harvested by centrifugation. The pellet was suspended in a mixture of isopropanol and water (1:1) and submitted to DSMZ for DNA-DNA hybridization with Pelosinus fermentans R7T (DSM 17108). DNA was isolated from the cell pellet using a French pressure cell and purified by chromatography on hydroxyapatite as described by Cashion et al. (1977). DNA-DNA hybridization was carried out as described previously (DeLey et al., 1970) with the modifications described by Huss et al. (1983) using a model Cary 100 Bio UV/VIS-spectrophotometer equipped with a Peltier-thermostatted 6 × 6 multicell changer and a temperature controller with in situ temperature probe (Varian). Percent DNA-DNA similarity was measured in 2X saline sodium citrate (SSC) solution at 65°C.

Fatty Acid Methyl Ester Analysis

An overnight culture of “P. lilae” UFO1 was grown on R2A broth containing 20 mM fumarate at 30°C. The cells were harvested by centrifugation, frozen (-20°C), and analyzed by Microbial ID (Newark, DE, United States) for fatty acid methyl ester content.

Electron Microscopy

Cells were grown overnight at 30°C in R2A broth containing 20 mM fumarate for morphological characterization using a Philips XL 30 Environmental Scanning Electron Microscope (ESEM), operating at 10 kV with a typical target current of 1.75 μA. Prior to imaging, the cells were washed twice and re-suspended in phosphate buffered saline (pH 7). Droplets of the washed cell suspension were placed in a conical ESEM mount to maximize solution volume. The chamber was maintained at ∼45% relative humidity (2.0°C, 2.4 torr of H2O) using a combination of Peltier cooling and differential pumping. ESEM imaging looked first at the edges of the mount then progressed inward to find regions of optimal cell density, minimal desiccation, and minimal precipitation of salts.

16S rRNA Gene Amplification

Genomic DNA was extracted from “P. lilae” UFO1 using the Mo Bio Ultra Clean Microbial DNA kit (Mo Bio Laboratories, Inc., Carlsbad, CA, United States). PCR amplification of the 16S rRNA gene was performed with primers 8F (5′-AGAGTTTGATCCTGGCTCAG-3′) (Eden et al., 1991), 907R (5′-CCGTCAATTCMTTTRAGTTT-3′) (Lane et al., 1985), 704F (5′-GTAGCGGTGAAATGCGTAGA-3′) (Lane et al., 1985), and 1492R (5′-GGTTACCTTGTTACGACTT-3′) (Lane, 1991). Each 50 μL PCR reaction mixture contained 1 U mL-1 of Deep Vent polymerase and 1X ThermoPol reaction buffer (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA, United States), 250 μM dNTPs, 800 nM of each primer, 2 mM MgSO4, and 1.5 μL of genomic DNA template. The PCR amplification conditions were as follows: an initial 95°C denaturation for 5 min, followed by 30 cycles of 95°C denaturation for 1 min, 56.1°C primer annealing for 1 min, and 72°C extension for 2.5 min, and then a final extension at 72°C for 4 min. PCR products were purified using the Qiagen QIAquick PCR Purification Kit (Valencia, CA, United States) per manufacturer’s instructions. The 16S rRNA gene PCR products were sequenced at the Idaho State University Molecular Research Core Facility (MRCF) on an ABI 3100 automated capillary sequencer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, United States) using 8F, 519R (5′-ATTACCGCGGCTGCTGG-3′) (Lane et al., 1985), 907R, 704F, 1100F (5′-CAACGAGCGCAACCCT-3′) (Lane et al., 1985), and 1492R primers in order to guarantee overlap of sequences. PCR products amplified with 8F and 1492R primers were also cloned in order to resolve the 3′ and 5′ ends of the 16S rRNA gene. Immediately following the PCR reaction, 3′-A overhangs were added to blunt-end 16S rRNA gene amplicons generated with 8F/1492R and Deep Vent polymerase using Taq polymerase (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, United States) in an additional 10-min extension performed at 72°C. For addition of 3′-A overhangs, the 25 μL reaction contained the following: 16.2 μL of blunt-end PCR product, 1X buffer, 2 mM MgCl2, 400 μM dATP, and 1 U Taq polymerase. The resulting 16S rRNA gene product was cloned into the pCR4 ®-TOPO® vector using the TOPO TA Cloning® Kit for Sequencing (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, United States) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Plasmids were purified from clones using the Qiagen Qiaprep® Spin Miniprep kit (Valencia, CA, United States) and sequenced directly using primers M13F (5′-GTAAAACGACGGCAG-3′), M13R (5′-CAGGAAACAGCTATGAC-3′), T3 (5′-ATTAACCCTCACTAAAGGGA-3′), and T7 (5′-TAATACGACTCACTATAGGG-3′) at the ISU MRCF. The GenBank accession number for the 16S rRNA sequence of “P. lilae” UFO1 is DQ295866, and the draft genome accession number is CP008852.

Phylogenetic Analysis

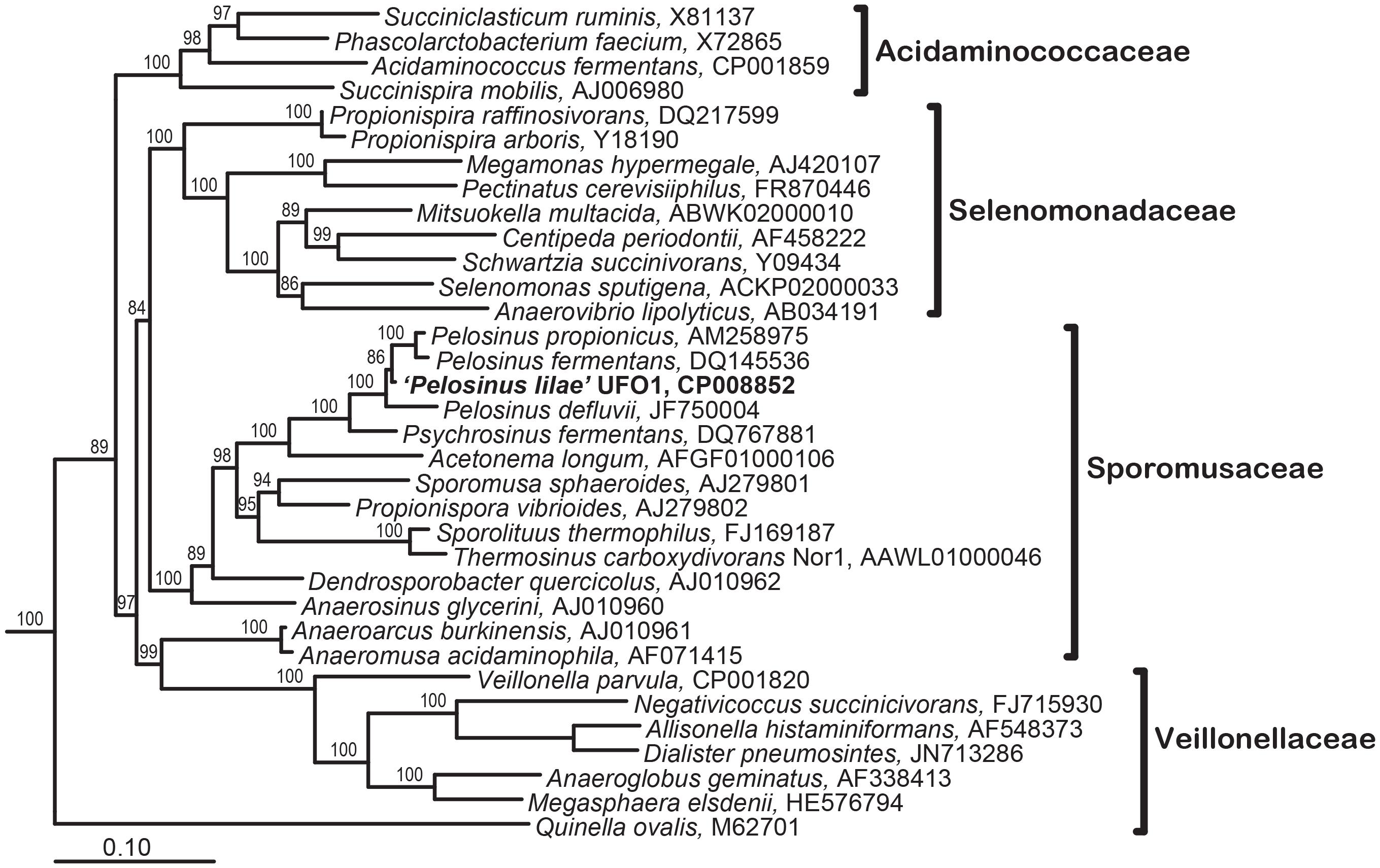

Species representing the Negativicutes Class were determined based on the List of Prokaryotic Names with Standing in Nomenclature (LPSN)1 (Parte, 2014). Phylogenetic analysis was conducted using both ARB, version 6.0.6 (Strunk et al., 1996) software, and the SILVA sequence database SSURef_NR99_128_SILVA_07_09_16_opt2 (Quast et al., 2013). Sequences not available in this SILVA database were downloaded from GenBank3. SILVA sequence alignments were used with a few refinements made manually. Sequences were filtered using SILVA’s positional variability by parsimony filter for bacteria (pos_var_ssuref:bacteria). Phylogenetic tree was inferred within the ARB software by the Maximum Likelihood method PHYML, version 20130708 (Guindon and Gascuel, 2003), using nucleotide substitution model HKY85 (Hasegawa et al., 1985) and branch supports determined by Bayesian estimation.

Results and Discussion

Strain Isolation and Morphology

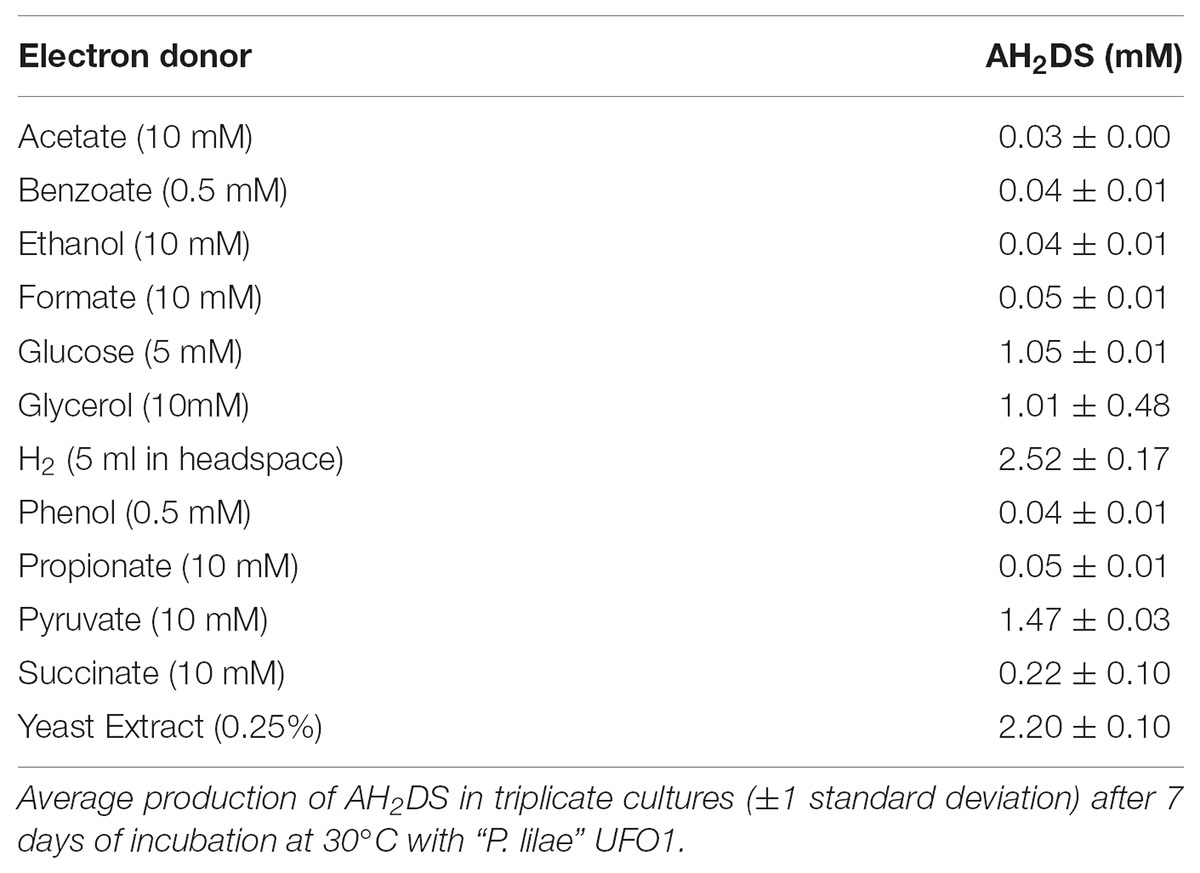

“Pelosinus lilae” UFO1 was isolated under strictly anaerobic conditions from dilution-to-extinction cultivation experiments, and was capable of AQDS reduction, as evident by a color change in growth medium from transparent, pale yellow to bright orange. An aliquot of enrichment culture was streaked on R2A plates containing 20 mM fumarate, and after 48–72 h of anaerobic incubation, small, round, white colonies were apparent. After re-streaking at least three times, a colony was transferred to FW medium containing lactate and AQDS, and the culture reduced AQDS. “P. lilae” UFO1 is a strict anaerobe with a fermentative metabolism, and microscopic observations revealed that it is rod-shaped, 0.2–0.7 × 1.5–4.7 μm in size (Figure 1-left panel), motile, and stains Gram-variable. Structures that appeared to be spores were also visible (Figure 1-right panel). Extracellular polymeric substance (EPS) is associated with individual cells, as judged by electron-dense materials surrounding the cell periphery. The production of spores was supported by the observation that a 10% inoculum from thermally-treated (85°C for 32 min) cell suspensions of “P. lilae” UFO1 could be re-grown in R2A broth and also exhibited the ability to reduce AQDS in the presence of H2 upon transfer to fresh media.

FIGURE 1. Left Panel: Scanning electron micrographs revealing extracellular materials surrounding a cell of “P. lilae” UFO1. Right Panel: Light micrograph of a culture of “P. lilae” UFO1 with apparent spore-like structures, the dark areas within cells, usually located at the cell terminus. Note the extracellular materials associated with the cell.

Temperature and pH Tolerance

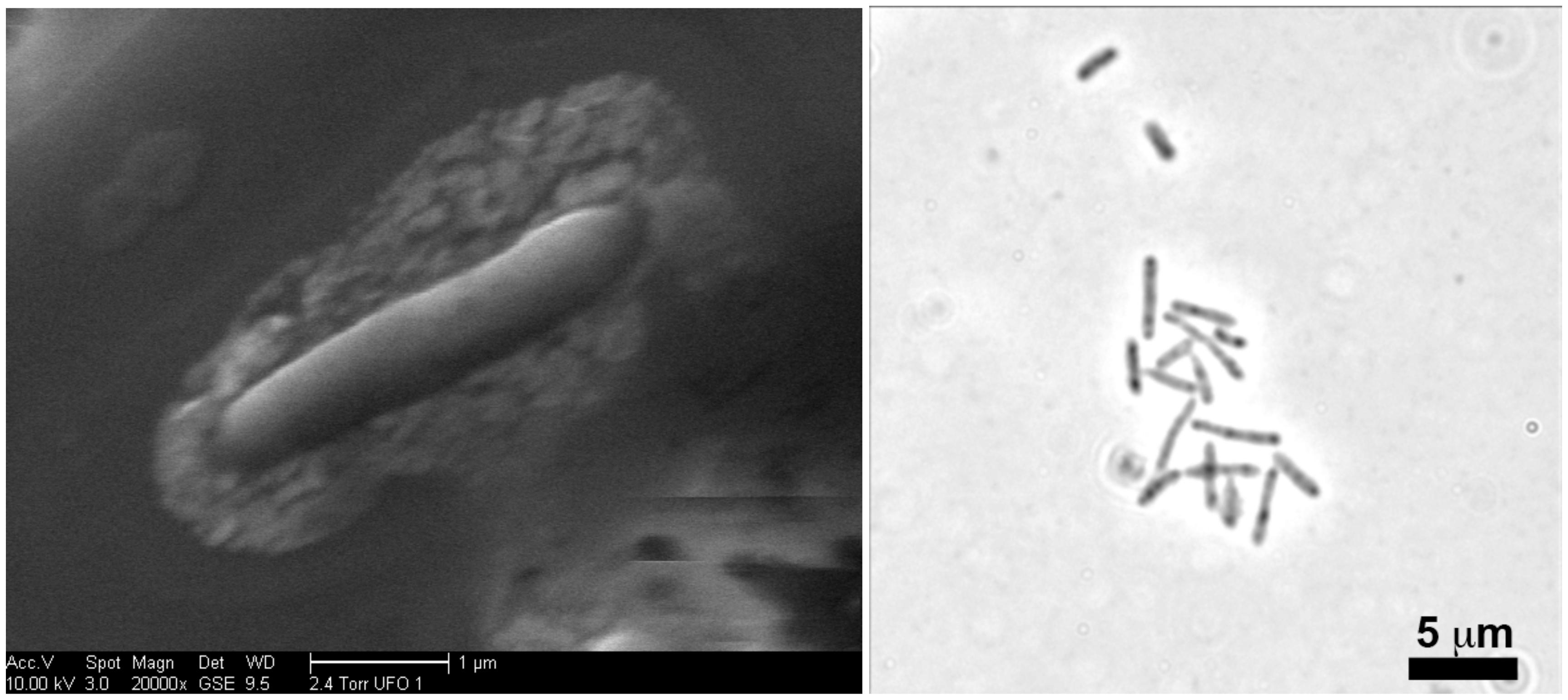

A growth curve for “P. lilae” UFO1 at 30°C is shown in Figure 2. Optimal temperature and pH for growth of “P. lilae” UFO1 were determined using R2A broth supplemented with 20 mM fumarate. The range of growth temperatures was 22–37°C, with an optimum of 37°C; average generation times at 22, 30, and 37°C were 4.6, 2.9, and 1.9 h, respectively. The range of pH for growth on R2A broth with 20 mM fumarate was 5.5–8, with optimum growth at pH 7. No growth was observed at temperatures of 13°C or 42°C, or at pH ≤ 5.4 or pH ≥ 8.5.

FIGURE 2. Growth curve of “P. lilae” UFO1 on R2A broth supplemented with 20 mM fumarate at 30°C. Symbols are means of triplicate analyses, and error bars indicate ± 1 standard deviation.

Electron Donor Utilization

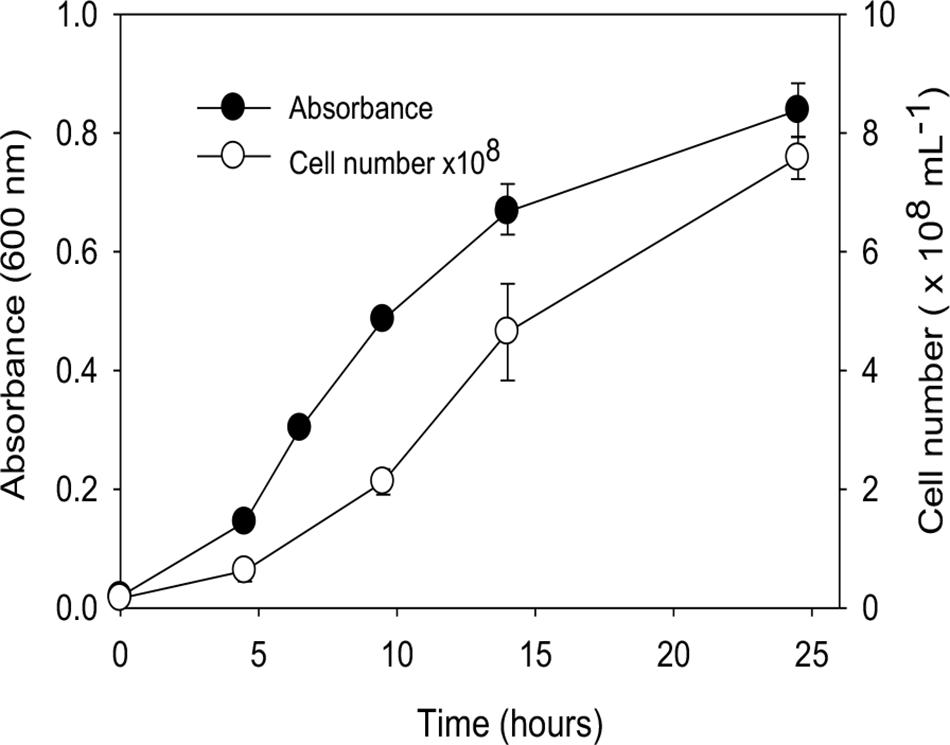

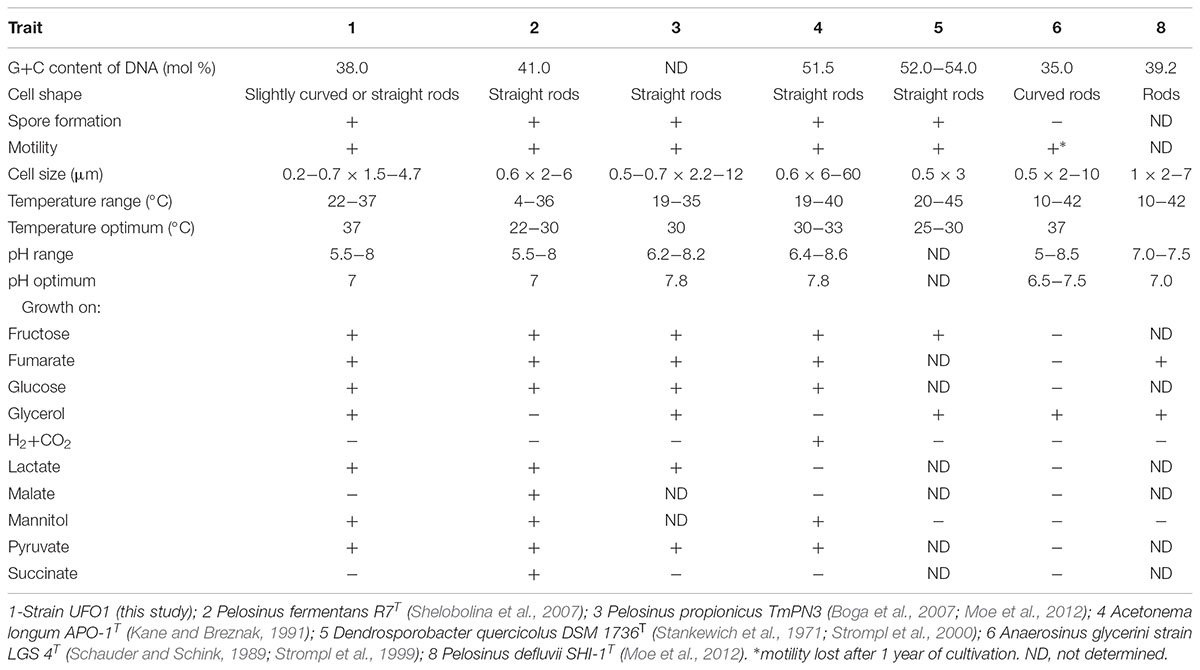

Carbon sources utilized in Biolog AN microplates were D-fructose, L-fucose, D-galactose, D-galacturonic acid, D-glucose-6-phosphate, glycerol, 3-methyl-D-glucose, palatinose, L-rhamnose, α-ketobutyric acid, α-ketovaleric acid, pyruvic acid, and succinic acid. “P. lilae” UFO1 fermented the following substrates (as evidenced by growth in the absence of an externally supplied electron acceptor): fructose, fumarate, glucose, glycerol, lactate, mannitol, pyruvate, and yeast extract. Malate and succinate were tested but not fermented. “P. lilae” UFO1 did not grow chemoautotrophically on H2-CO2 (see Table 1).

Metal Transformation

Although “P. lilae” UFO1 was isolated from an Fe(III)-reducing enrichment by cultivation with acetate and AQDS, this “P. lilae” was not capable of respiratory growth on AQDS when 10 mM acetate was provided as the electron donor. AQDS was reduced to AH2DS only in the presence of fermentable substrates or H2 (Table 1). In the presence of 10 mM lactate, nitrate was reduced to nitrite following 1 week of incubation. As(V), NO3-, SeO42-, and SO42- were not reduced in the presence of 10 mM lactate.

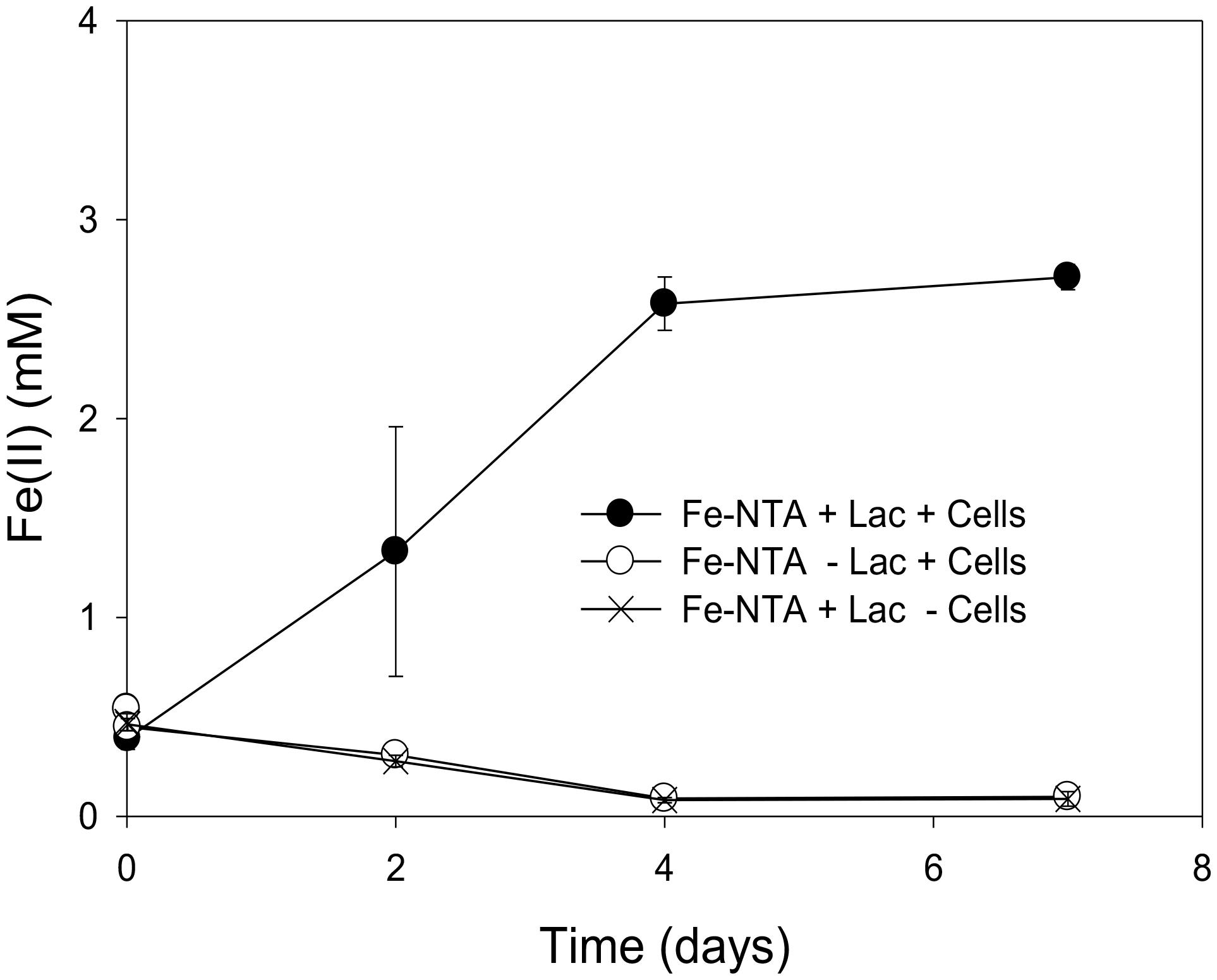

The incomplete reduction of 10 mM Fe(III)-NTA by “P. lilae” UFO1 is shown in Figure 3. In the presence of 10 mM lactate, nearly 3 mM Fe(II) was produced after 1 week of incubation. Production of Fe(II) was not evident in abiotic controls. Biotic reduction of Fe(III)-NTA in the absence of lactate did not occur.

FIGURE 3. Incomplete reduction of Fe(III)-NTA (10 mM) by “P. lilae” UFO1 in the presence of a fermentable substrate, 10 mM lactate after 7 days of incubation. Symbols are means of triplicate cultures, and error bars indicate ± 1 standard deviation.

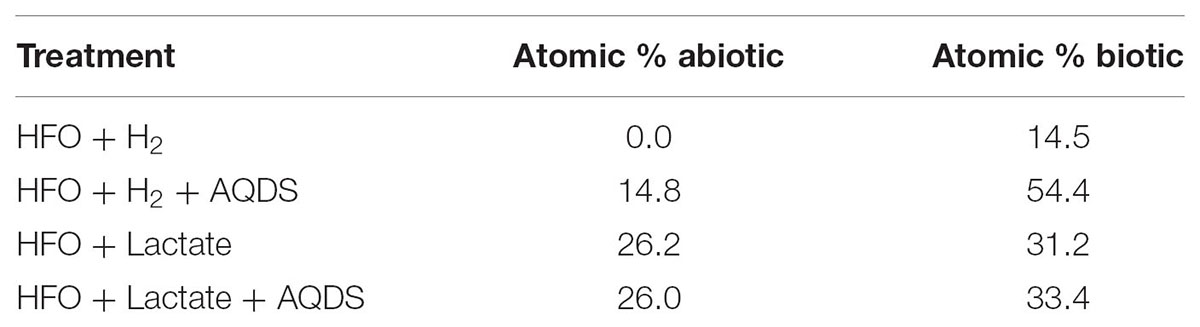

High-resolution core Fe 2p3/2 spectra collected on a cell-free control containing ferrihydrite incubated with culture medium and H2 suggested that abiotic Fe(III)-reduction did not take place under these conditions (Table 2). The collected peak envelope is described well by the Fe(III) multiplet splitting model and is in agreement with published iron oxide spectra (data not shown). However, cell-free controls incubated with H2 + AQDS, lactate, or lactate + AQDS revealed the presence of 14.8, 26.2, and 26.0 atom% Fe(II), respectively, indicating some abiotic reduction of ferrihydrite occurred. Incubation of ferrihydrite with strain UFO1 and H2, both with and without AQDS, revealed a significant increase in the Fe(II) contribution compared to the abiotic controls. Addition of a principal Fe(II) peak at 708.4 eV for the ferrihydrite spectra (together with associated multiplet and satellite peaks) was required to complete the model (not shown). In contrast, lactate did not appear to significantly enhance reduction of ferrihydrite by “P. lilae” UFO1 regardless of the presence of AQDS.

TABLE 2. Results of fitting multiplet splitting peak models to X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy–derived Fe 2p3/2 photopeaks collected from 2-line ferrihydrite recovered from cultures of UFO1 in the presence and absence of AQDS with H2 and lactate compared to abiotic controls.

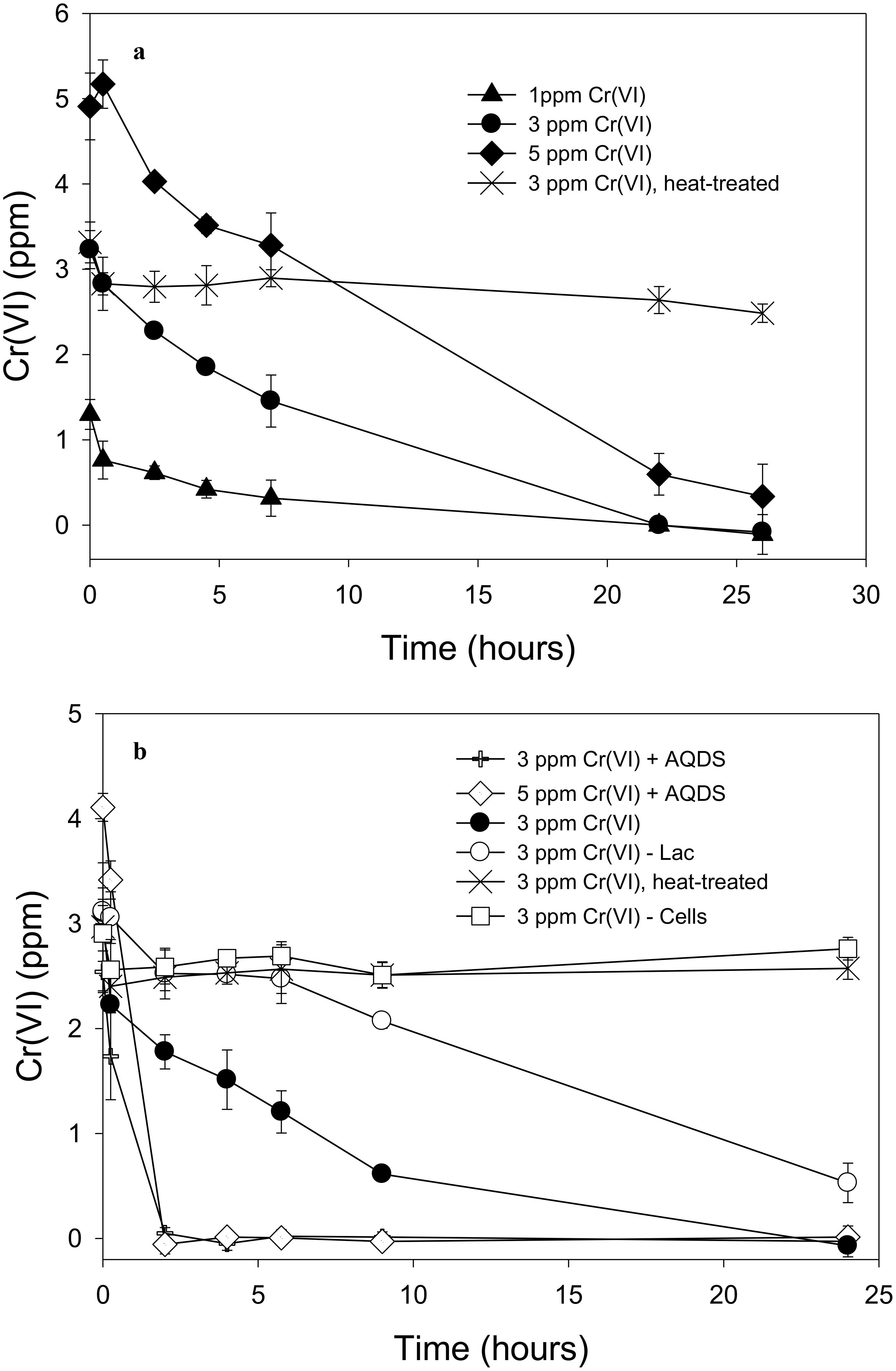

Soluble Cr(VI) was removed from solution in cell suspensions of “P. lilae” UFO1 under non-growth conditions. Figure 4A shows the nearly complete removal of 1 and 3 ppm Cr(VI) by strain UFO1 within 24 h when lactate (10 mM) was provided as an electron donor, whereas 5 ppm Cr(VI) decreased to an average 0.3 ppm in 26 h. Over the course of the experiment, controls containing heat-treated cells (90°C, 32 min) did not exhibit significant Cr(VI) removal suggesting that sorption to cell surfaces did not contribute to the removal of Cr(VI) seen in other treatments. In Figure 4B, it is evident that Cr(VI) removal was dramatically enhanced in the presence of 1 mM AQDS. For treatments containing 3 and 5 ppm Cr(VI) with lactate (10 mM) plus 1 mM AQDS, Cr(VI) concentrations dropped to less than 0.1 ppm after just 2 h of incubation with cell suspensions of strain UFO1. There was no significant change in Cr(VI) concentrations in cell-free and heat-treated controls. In contrast to the Fe(III)-NTA results, where lactate appeared to be required for Fe(III) reduction, Cr(VI) was removed in the absence of lactate from 3 to 0.5 ppm in 24 h, which may suggest the use of endogenous carbon reserves by “P. lilae” UFO1, if removal is assumed to be the result of reduction. Others have similarly observed removal of soluble Cr(VI) by other bacterial species in the absence of exogenous electron donors (Ishibashi et al., 1990; Shen and Wang, 1993; Sani et al., 2002), suggesting that Cr(VI) removal occurs via the action of an enzyme utilizing endogenous electron donors (i.e., cellular NADH, FADH2) with a non-specific NADH oxidoreductase activity that can reduce Cr(VI) to Cr(III). In Pelosinus sp. HCF1 (Beller et al., 2013), Cr reduction was thought to be linked to a flavoprotein related to the ChrR family of chromate reductases, with potential involvement of hydrogenases. Genome analysis suggests a similar potential in “P. lilae” UFO1 (see below).

FIGURE 4. (A) Removal of 1, 3, and 5 ppm Cr(VI) by “P. lilae” UFO1. Lactate (10 mM) was present in all treatments. (B) Cr(VI) removal in the presence or absence of 1 mM AQDS, and removal of Cr(VI) in lactate-free controls. Lactate (10 mM) was present in all treatments unless otherwise noted. Symbols are means of triplicate analyses, and error bars indicate ± 1 standard deviation.

“P. lilae” UFO1 was previously evaluated for its U(VI) transformation abilities (Ray et al., 2011), and a potential mechanism for U(VI) sequestration in this isolate was discovered (Thorgersen et al., 2017). Interactions of U(VI) with extracellular materials led to the discovery of S-layer mediated binding of U(VI), as well as some reduction activity [appearance of U(IV)]. While the precise mechanisms of sequestration and reduction of Cr, U, and Fe in strain UFO1 remain poorly characterized, we propose that a combined sequestration/transformation mechanism is at play for dealing with Cr, U, Fe, and perhaps a variety of other metals not yet evaluated. Previous studies examining S-layer metal binding in Bacillus support this idea (Velásquez and Dussan, 2009), but the true functionality of “P. lilae” UFO1 S-layer proteins in toxic metal binding and sequestration remains to be investigated.

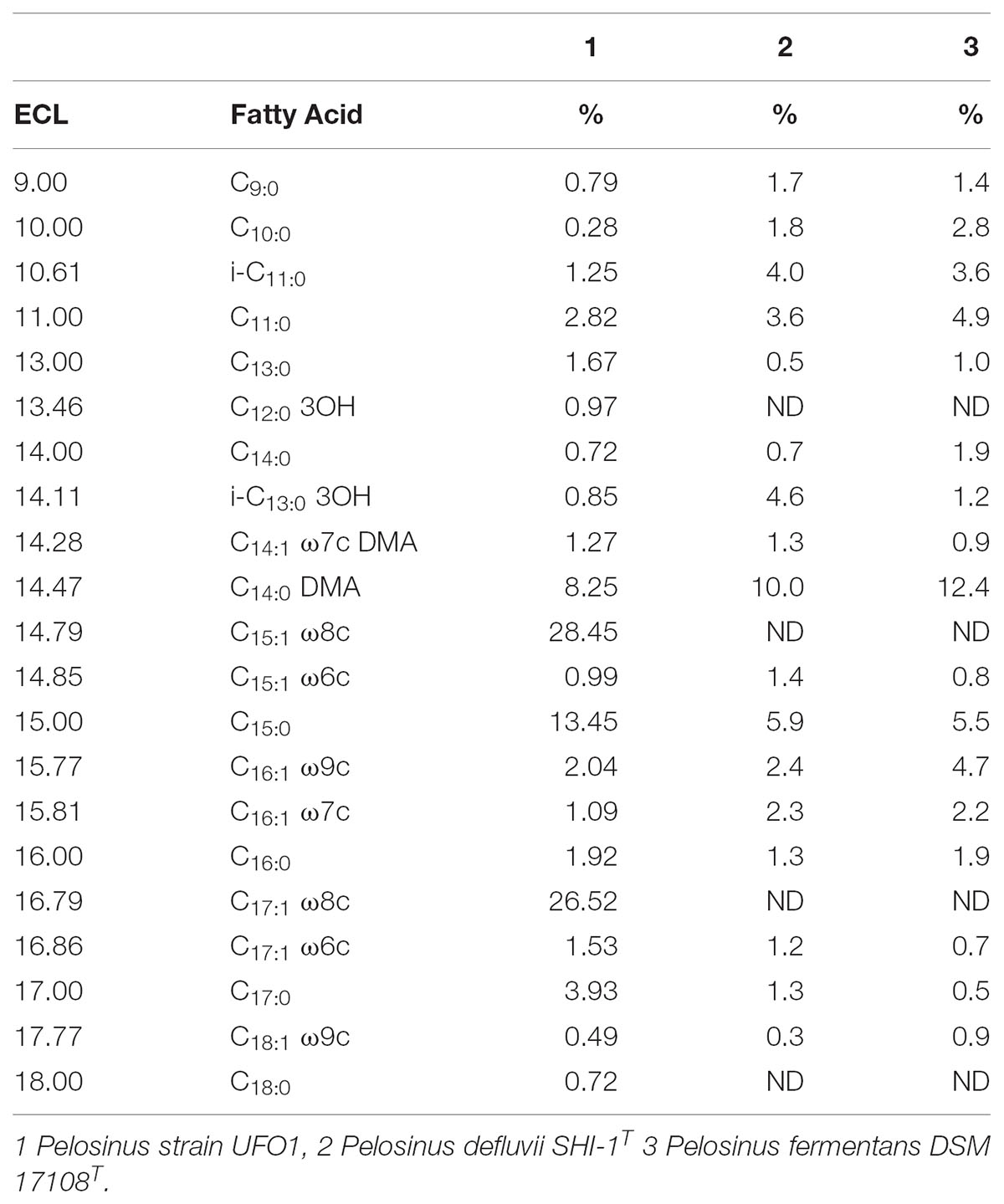

Biochemical Characteristics

The majority of fatty acids identified in strain UFO1 were straight unsaturated chains in cis conformation (Table 3). The predominant fatty acids identified were C15:1 ω8c, C17:1 ω8c, and C15:0. “P. lilae” UFO1 had straight saturated (35.52%) and unsaturated (62.38%) chains, 6.59% C11 and C13 fatty acids, 74.87% C15 and C17. The fatty acid profile of strain UFO1 is consistent with profiles characteristic of members of the Class Negativicutes described previously (Strompl et al., 1999) with the exception of 3-hydroxy fatty acids, which were only present at 1.82%. Dimethyl acetals (C14:0 DMA and C14:1 ω7c DMA) accounted for 9.52% of the total fatty acids identified and are characteristic of anaerobic bacteria. Significant amounts of dimethyl acetals among members of the Class Negativicutes have been reported previously (Moore et al., 1994).

TABLE 3. Equivalent chain length (ECL) and fatty acid composition (%) of “P. lilae” UFO1 and comparator strains.

The cell wall of “P. lilae” UFO1 contained meso-diaminopimelic acid (m-Dpm) as the diagnostic diamino acid in the total hydrolysate of the peptidoglycan. Alanine and glutamic acid were also present in the peptidoglycan. Partial hydrolysis of the peptidoglycan revealed the presence of the peptides L-ala—D-glu and Dpm—D-ala. From these data, it was concluded that “P. lilae” UFO1 shows the directly cross-linked peptidoglycan type, A1γ m-Dpm-direct (Schleifer and Kandler, 1972).

The G+C content of the genomic DNA of “P. lilae” UFO1 was 38.0 mol% (Table 4). The DNA G+C content of P. fermentans R7T, is 41.0 mol% (Shelobolina et al., 2007). Additionally, duplicate DNA-DNA hybridizations conducted with strain UFO1 against P. fermentans R7T showed 9.8 and 23.7% DNA-DNA similarity, indicating that strain UFO1 does not belong to the species P. fermentans as defined by the threshold value of 70% DNA-DNA relatedness (Wayne et al., 1987).

TABLE 4. Distinguishing features of strain UFO1 compared to the most closely related described species in the Class Negativicutes.

16S rRNA Gene Sequence and Phylogenetic Analysis

“Pelosinus lilae” UFO1 is firmly included within the Pelosinus clade in the Sporomusaceae family with branch support of 100 (Figure 5). Results indicate that “P. lilae” UFO1 is phylogenetically distinct from the most closely related organisms P. fermentans R7T (Shelobolina et al., 2007), Pelosinus propionicus strains TmPN3Tand TmPM3 (originally published as Sporotalea propionica) (Boga et al., 2007), and Pelosinus defluvii (Moe et al., 2012). The distances between 16S sequences from “P. lilae” UFO1 and the closest type strains, P. fermentans strain R7T and P. propionicus TmPN3T, were 1.84 and 2.40% respectively, which are greater than the distance between the described type strains, 0.9%. A BLAST search of the 16S rRNA gene sequence of strain UFO1 revealed 99% similarity (over 1041 nucleotide bases) with a clone detected in a pH 5, Fe(III)-reducing enrichment established with background sediments from the FRC, pH5lac302-37 (AY527741) (Petrie et al., 2003). Additionally, two clones detected by Petrie and co-workers (Petrie et al., 2003) that were from Fe(III)-reducing enrichments established with contaminated FRC sediments also shared a high degree of 16S rRNA gene sequence similarity with “P. lilae” UFO1: 97% for Gly030-8A (AY524569) and 97% for Gly030-5C (AY524568). A recent paper by Newsome et al. (2015) report the presence of Pelosinus in enrichments of sediments from a United Kingdom nuclear site. Stimulation with glycerol phosphate resulted in substantial increases in bacteria closely related to Pelosinus, which comprised 33% of bacteria identified at the genus level. This work implicates Pelosinus species as having a key role in the removal of soluble U(VI) via precipitation to a reduced, crystalline U(IV) phosphate mineral, considered to be more recalcitrant to oxidative remobilization, in contaminated sediments.

FIGURE 5. Maximum Likelihood tree showing phylogenetic relationships of the 16S rRNA genes in the Class Negativicutes; the types species for each genus in the four families within this class is included. Branch supports determined by Bayesian estimation ≥80 are shown at branch points. Scale bar indicates 0.1 changes per nucleotide. Tree was rooted with 4 species (not shown): Bacillus subtilis (AB042061), Clostridium acetobutylicum (AE001437), Desulfotomaculum acetoxidans (Y11566), and Heliobacillus mobilis (AB100835).

During the analysis of the 16S rRNA gene sequence of “P. lilae” UFO1, significant inter-operon heterogeneity among 16S rRNA gene clones from “P. lilae” UFO1 was detected. Sequencing of cloned 16S rRNA gene PCR products revealed two distinct 16S rRNA gene sequences were present in strain UFO1. These differences were not due to the presence of a contaminant, as the culture was extensively purified prior to analysis (Ray et al., 2010). In one group of clones a 100-bp insertion was present near the 5′ end of the sequence. This type of 16S rRNA gene sequence heterogeneity was previously reported for the, proposed but not validly published, member of the Class Negativicutes “Anaerospora hongkongensis” (Woo et al., 2005; Beller et al., 2013). 16S rRNA length heterogeneity has also been reported in a few other unrelated species, notably Paenibacillus polymyxa (Nubel et al., 1996), Desulfotomaculum kuznetsovii (Tourova et al., 2001), Aeromonas strains (Morandi et al., 2005), Bacillus clausii (Kageyama et al., 2007), and the archaeon Haloarcula marismortui (Mylvaganam and Dennis, 1992; Amann et al., 2000). Further work has demonstrated that the insert-bearing 16S rRNA gene sequence was not functional in the ribosomes of strain UFO1 (Ray et al., 2010).

Genome Annotation and Implications for Metal Transformation

The draft genome sequence for strain UFO1 (Brown et al., 2014) was data-mined for genes potentially involved in metal transformation. Pathways relevant to metal transformation include 2 loci encoding arsenate reductase (UFO1_2328, UFO1_2536), subunits for a cytochrome c-dependent nitrate reductase (UFO1_1541, UFO1_1544), and several loci for flavin reductases (thought to be involved in chromium transformation). A predicted Co-Zn-Cd efflux system (UFO1_2233) is also present. Additionally, “P. lilae” UFO1 has a chrA locus for chromate transport (UFO1_3236), and a NiFe-hydrogenase (UFO1_2674) linked to a cytochrome b (UFO1_2673). Obviously, characterized metal-reducing Firmicutes, including strain UFO1, harbor a multiplicity of genes conferring metal detoxification ability, further extending the importance of these organisms in the biogeochemical processing of toxic metals.

Potential Ecophysiologic Role of “Pelosinus lilae” UFO1 in Subsurface Environments

“Pelosinus lilae” UFO1 represents a novel addition to a recently described and poorly characterized genus of fermentative bacteria. The most closely-related species, P. fermentans R7T, was similarly isolated from an Fe(III)-reducing enrichment; however, the enrichment was established with kaolin lenses originating from Plast, Russia (Shelobolina et al., 2007). This suggests that representatives of Pelosinus may be widespread in anoxic environmental systems. Kappler et al. (2004) demonstrated that fermenting bacteria were one of the largest populations of bacteria in freshwater lake sediments and had an important role in humic acid reduction; the results suggested that humic acid-mediated reduction of poorly soluble Fe(III) oxides is an important reductive pathway in anoxic natural environments. “P. lilae” UFO1 demonstrated the ability to reduce the humic acid analog, AQDS, in the presence of H2 and fermentable substrates; in addition, AQDS mediated the reduction of the insoluble Fe(III)-oxide, ferrihydrite. The presence of AQDS also enhanced Cr(VI) removal from solution. The AQDS-AH2DS couple has a standard potential (Eo) of -184 mV at pH 7 (Fultz and Durst, 1982; Wolf et al., 2009), which is well below that for the CrO42--Cr(OH)3 couple (+480 mV at pH 7) (Takeno, 2005); therefore, the transfer of electrons from AH2DS to CrO42- is thermodynamically favorable and suggests Cr(VI) removal in the presence of AQDS was likely due to reduction. These findings suggest that fermentative bacteria such as strain UFO1 may play a role in the reduction of humic acids, which may in turn facilitate the reduction of metallic contaminants in subsurface environments.

“Pelosinus lilae” UFO1 was isolated from pristine sediments beneath Oak Ridge National Laboratory, Oak Ridge, TN, United States. Organisms with high 16S rRNA gene sequence similarity to strain UFO1 have been detected in Fe(III)-reducing (Petrie et al., 2003) and U(VI)-reducing (Nyman et al., 2007) enrichments initiated with contaminated sediments, which may suggest the prevalence of Pelosinus species in the subsurface. Strain UFO1, and organisms with similar metabolic capabilities also offer potential for the removal of soluble U(VI) from cell suspensions (Ray et al., 2011). “P. lilae” UFO1 has been shown to reduce metals with or without an exogenous “electron shuttle” such as AQDS, and genome analysis predicts additional metal-transformation pathways that have not yet been verified. The transformation of an array of electron acceptors such as AQDS, Fe(III), Cr(VI) and U(VI) by UFO1 suggest a potentially important role for this and similar organisms in influencing the biogeochemistry of pristine and contaminated geologic media at the ORFRC.

Author Contributions

AR, SC, AN, JI, and DC conducted the experiments. AR, SC, YF, DC, and TM designed the experiments. All authors contributed to the preparation of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by funding from the Inland Northwest Research Alliance (INRA) and Idaho National Laboratory (INL) under DOE Idaho Operations Office Contract DE-AC07-05ID14517. AR was supported by INRA and INL Subsurface Science Graduate Fellowship, TM and DC were supported by INRA Subsurface Science Initiative Grant Number ISU-004.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We thank E. O’Leary-Jepson and M. Andrews of the ISU MRCF for DNA sequencing; P. Pinhero and T. Trowbridge for help with electron microscopy; J. Taylor for ion chromatography; M. Thomas for assistance with phylogenetic analysis; A. Eddingsaas, L. Wendt, T. Gresham, D. Reed, and J. Barnes for technical assistance. We would also like to thank D. Watson for providing core samples from ORFRC. XPS was performed at the Image and Chemical Analysis Laboratory, Department of Physics, Montana State University, Bozeman, MT, United States.

Footnotes

References

Amann, G., Stetter, K. O., Llobet-Brossa, E., Amann, R., and Anton, J. (2000). Direct proof for the presence and expression of two 5% different 16S rRNA genes in individual cells of Haloarcula marismortui. Extremophiles 4, 373–376. doi: 10.1007/s007920070007

Balch, W. E., and Wolfe, R. S. (1976). New approach to the cultivation of methanogenic bacteria: 2-mercaptoethanesulfonic acid (HS-CoM)-dependent growth of Methanobacterium ruminantium in a pressurized atmosphere. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 32, 781–789.

Beller, H. R., Han, R., Karaoz, U., Lim, H., and Brodie, E. L. (2013). Genomic and physiological characterization of the chromate-reducing, aquifer-derived firmicute Pelosinus sp. strain HCF1. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 79, 63–73. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02496-12

Benz, M., Schink, B., and Brune, A. (1998). Humic acid reduction by Propionibacterium freudenreichii and other fermenting bacteria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 64, 4507–4512.

Bochner, B. R. (1989). Sleuthing out bacterial identities. Nature 339, 157–158. doi: 10.1038/339157a0

Boga, H., Ji, R., Ludwig, W., and Brune, A. (2007). Sporotalea propionica gen. nov. sp. nov., a hydrogen-oxidizing, oxygen-reducing, propionigenic firmicute from the intestinal tract of a soil-feeding termite. Arch. Microbiol. 187, 15–27. doi: 10.1007/s00203-006-0168-7

Borch, T., Inskeep, W. P., Harwood, J. A., and Gerlach, R. (2005). Impact of ferrihydrite and anthraquinone-2,6-disulfonate on the reductive transformation of 2,4,6-trinitrotoluene by a gram-positive fermenting bacterium. Environ. Sci. Technol. 39, 7126–7133. doi: 10.1021/es0504441

Brown, S. D., Utturkar, S. M., Magnuson, T. S., Ray, A. E., Poole, F. L., Lancaster, W. A., et al. (2014). Complete genome sequence of Pelosinus sp. strain UFO1 assembled using single-molecule real-time DNA sequencing technology. Genome Announc. 2:e00881-14. doi: 10.1128/genomeA.00881-14

Caccavo, F. Jr., Blakemore, R. P., and Lovley, D. R. (1992). A hydrogen-oxidizing, Fe(III)-reducing microorganism from the Great Bay Estuary, New Hampshire. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 58, 3211–3216.

Caccavo, F. Jr., Frolund, B., Kloeke, F. V.-O., and Nielsen, P. H. (1996). Deflocculation of activated sludge by the dissimilatory Fe(III)-reducing bacterium Shewanella alga BrY. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 62, 1487–1490.

Caccavo, F. Jr., Lonergan, D. J., Lovley, D. R., Davis, D. D., Stolz, J. F., and McInerney, M. J. (1994). Geobacter sulfurreducens sp. nov., a hydrogen- and acetate-oxidizing dissimilatory metal-reducing microorganism. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 60, 3752–3759.

Cashion, P., Hodler-Franklin, M. A., McCully, J., and Franklin, M. (1977). A rapid method for base ratio determination of bacterial DNA. Anal. Biochem. 81, 461–466. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(77)90720-5

Cummings, D. E., Caccavo, F., Fendorf, S., and Rosenzweig, R. F. (1999). Arsenic mobilization by the dissimilatory Fe(III)-reducing bacterium Shewanella alga BrY. Environ. Sci. Technol. 33, 723–729. doi: 10.1021/es980541c

DeLey, J., Cattoir, H., and Reynaerts, A. (1970). The quantitative measurement of DNA hybridization from renaturation rates. Eur. J. Biochem. 12, 133–142. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1970.tb00830.x

Eden, P. A., Schmidt, T. M., Blakemore, R. P., and Pace, N. R. (1991). Phylogenetic analysis of Aquaspirillum magnetotacticum using polymerase chain reaction-amplified 16S rRNA-specific DNA. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 41, 324–325. doi: 10.1099/00207713-41-2-324

EPA (2003). EPA National Primary Drinking Water Standards. www.epa.gov/safewater/mcl.html#mcls

Finneran, K. T., Forbush, H. M., Van Praagh, C. G., and Lovley, D. R. (2002). Desulfitobacterium metallireducens sp. nov., an anaerobic bacterium that couples growth to the reduction of metals and humic acids as well as chlorinated compounds. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 52, 1929–1935.

Fredrickson, J. K., Kostandarithes, H. M., Li, S. W., Plymale, A. E., and Daly, M. J. (2000). Reduction of Fe(III), Cr(VI), U(VI), and Tc(VII) by Deinococcus radiodurans R1. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66, 2006–2011. doi: 10.1128/AEM.66.5.2006-2011.2000

Fultz, M. L., and Durst, R. A. (1982). Mediator compounds for the electrochemical study of biological redox systems: a compilation. Anal. Chim. Acta 140, 1–18. doi: 10.1016/S0003-2670(01)95447-9

Guindon, S., and Gascuel, O. (2003). A simple, fast, and accurate algorithm to estimate large phylogenies by maximum likelihood. Syst. Biol. 52, 696–704. doi: 10.1080/10635150390235520

Gupta, R. P., and Sen, S. K. (1975). Calculation of multiplet structure of core p-vacancy levels II. Phys. Rev. B 12, 15–19. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.12.15

Hasegawa, M., Kishino, H., and Yano, T. (1985). Dating of the Human-Ape splitting by a molecular clock of mitochondrial-DNA. J. Mol. Evol. 22, 160–174. doi: 10.1007/BF02101694

Herbert, R. B., Benner, S. G., Pratt, A. R., and Blowes, D. W. (1998). Surface chemistry and morphology of poorly crystalline iron sulfides precipitated in media containing sulfate-reducing bacteria. Chem. Geol. 87–97. doi: 10.1016/S0009-2541(97)00122-8

Huss, V. A. R., Festl, H., and Schleifer, K. H. (1983). Studies on the spectrophotometric determination of DNA hybridization from renaturation rates. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 4, 184–192. doi: 10.1016/S0723-2020(83)80048-4

Ishibashi, Y. C., Cervantes, C., and Silver, S. (1990). Chromium reduction in Pseudomonas putida. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 56, 2268–2270.

Kageyama, Y., Takaki, Y., Shimamura, S., Nishi, S., Nogi, Y., Uchimura, K., et al. (2007). Intragenomic diversity of the V1 regions of 16S rRNA genes in high-alkaline protease-producing Bacillus clausii spp. Extremophiles 11, 597–603. doi: 10.1007/s00792-007-0074-1

Kane, M. D., and Breznak, J. A. (1991). Acetonema longum gen. nov. sp. nov., an H2/CO2 acetogenic bacterium from the termite, Pterotermes occidentis. Arch. Microbiol. 156, 91–98. doi: 10.1007/BF00290979

Kappler, A., Benz, M., Schink, B., and Brune, A. (2004). Electron shuttling via humic acids in microbial iron(III) reduction in a freshwater sediment. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 47, 85–92. doi: 10.1016/S0168-6496(03)00245-9

Lane, D. J. (1991). “16S/23S rRNA sequencing,” in Nucleic Acid Techniques in Bacterial Systematics, eds E. Stackebrandt and M. Goodfellow (New York, NY: John Wiley and Sons).

Lane, D. L., Pace, B., Olsen, G. J., Stahl, D., Sogin, M. L., and Pace, N. R. (1985). Rapid determination of 16S ribosomal RNA sequences for phylogenetic analysis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 82, 6955–6959. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.20.6955

Lloyd, J. R. (2003). Microbial reduction of metals and radionuclides. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 27, 411–425. doi: 10.1016/S0168-6445(03)00044-5

Lovley, D. R., Coates, J. D., Blunt-Harris, E. L., Phillips, E. J. P., and Woodward, J. C. (1996). Humic substances as electron acceptors for microbial respiration. Nature 382, 445–448. doi: 10.1038/382445a0

Lovley, D. R., Fraga, J. L., Blunt-Harris, E. L., Hayes, L. A., Phillips, E. J. P., and Coates, J. D. (1998). Humic substances as a mediator for microbially catalyzed metal reduction. Acta Hydrochim. Hydrobiol. 26, 151–157. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-401X(199805)26:3<152::AID-AHEH152>3.0.CO;2-D

Lovley, D. R., Giovannoni, S. J., White, D. C., Champine, J. E., Phillips, E. J. P., Gorby, Y. A., et al. (1993). Geobacter metallireducens gen. nov. sp. nov., a microorganism capable of coupling the complete oxidation of organic compounds to the reduction of iron and other metals. Arch. Microbiol. 159, 336–344. doi: 10.1007/BF00290916

Lovley, D. R., and Lloyd, J. R. (2000). Microbes with a mettle for bioremediation. Nat. Biotechnol. 18, 600–601. doi: 10.1038/76433

Lovley, D. R., and Phillips, E. J. P. (1987). Rapid assay for microbially reducible ferric iron in aquatic sediments. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 53, 1536–1540.

Lovley, D. R., Phillips, E. J. P., and Lonergan, D. J. (1989). Hydrogen and formate oxidation coupled to dissimilatory reduction of iron or manganese by Alteromonas putrefaciens. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 55, 700–706.

Lovley, D. R., Stolz, J. F., Nord, G. L., and Phillips, E. J. P. (1987). Anaerobic production of magnetite by a dissimilatory iron-reducing microorganism. Nature 330, 252–254. doi: 10.1038/330252a0

Magnuson, T. S., Neal, A. L., and Geesey, G. G. (2004). Combining in situ reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction, optical microscopy, and X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy to investigate mineral surface-associated microbial activities. Microb. Ecol. 48, 578–588. doi: 10.1007/s00248-004-0253-x

McIntyre, N. S., and Zetaurk, D. G. (1977). X-ray photoelectron spectroscopic studies of iron oxides. Anal. Chem. 49, 1521–1529. doi: 10.1021/ac50019a016

Mesbah, M., Premachandran, U., and Whitman, W. B. (1989). Precise measurement of the G+C content of deoxyribonucleic-acid by high-performance liquid-chromatography. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 39, 159–167. doi: 10.1099/00207713-39-2-159

Miller, T. L., and Wolin, M. J. (1974). A serum bottle modification of the Hungate technique for cultivating obligate anaerobes. Appl. Microbiol. 27, 985–987.

Moe, W. M., Stebbing, R. E., Rao, J. Y., Bowman, K. S., Nobre, N. F., da Costa, M. S., et al. (2012). Pelosinus defluvii sp. nov., isolated from chlorinated solvent-contaminated groundwater, emended description of the genus Pelosinus and transfer of Sporotalea propionica to Pelosinus propionicus comb. nov. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 62, 1369–1376. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.033753-0

Moore, L. V., Bourne, D. M., and Moore, W. E. (1994). Comparative distribution and taxonomic value of cellular fatty acids in thirty-three genera of anaerobic gram-negative bacilli. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 44, 338–347. doi: 10.1099/00207713-44-2-338

Morandi, A., Zhaxybayeva, O., Gogarten, J. P., and Graf, J. (2005). Evolutionary and diagnostic implications of intragenomic heterogeneity in the 16S rRNA gene in Aeromonas strains. J. Bacteriol. 187, 6561–6564. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.18.6561-6564.2005

Mylvaganam, S., and Dennis, P. P. (1992). Sequence heterogeneity between the two genes encoding 16S rRNA from the halophilic archaebacterium Haloarcula marismortui. Genetics 130, 399–410.

NABIR (2003). Bioremediation of Metals and Radionuclides: What it is and How it Works. Available at: https://escholarship.org/uc/item/7md2589q

Neal, A. L., Clough, L. K., Perkins, T. D., Little, B. J., and Magnuson, T. S. (2004). In situ measurement of Fe(III) reduction activity of Geobacter pelophilus by simultaneous in situ RT-PCR and XPS analysis. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 49, 163–169. doi: 10.1016/j.femsec.2004.03.014

Newsome, L., Morris, K., Trivedi, D., Bewsher, A., and Lloyd, J. R. (2015). Biostimulation by glycerol phosphate to precipitate recalcitrant uranium(IV) phosphate. Environ. Sci. Technol. 49, 11070–11078. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.5b02042

Neal, A. L., Techkarnjanaruk, S., Dohnalkova, A., McCready, D., Peyton, B. M., and Geesey, G. G. (2001). Iron sulfides and sulfur species produced at hematite surfaces in the presence of sulfate-reducing bacteria. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 65, 223–235. doi: 10.1016/S0016-7037(00)00537-8

Nevin, K. P., and Lovley, D. R. (2000). Potential for nonenzymatic reduction of Fe(III) via electron shuttling in subsurface sediments. Environ. Sci. Technol. 34, 2472–2478. doi: 10.1021/es991181b

Nubel, U., Engelen, B., Felske, A., Snaidr, J., Wieshuber, A., Amann, R. I., et al. (1996). Sequence heterogeneities of genes encoding 16S rRNAs in Paenibacillus polymyxa detected by temperature gradient gel electrophoresis. J. Bacteriol. 178, 5636–5643. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.19.5636-5643.1996

Nyman, J., Gentile, M., and Criddle, C. (2007). Sulfate requirement for the growth of U(VI)-reducing bacteria in an ethanol-fed enrichment. Bioremediat. J. 11, 21–32. doi: 10.1080/10889860601185848

Parte, A. C. (2014). LPSN—list of prokaryotic names with standing in nomenclature. Nucleic Acids Res. 40, D613–D616. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1111

Petrie, L., North, N. N., Dollhopf, S. L., Balkwill, D. L., and Kostka, J. E. (2003). Enumeration and characterization of iron(III)-reducing microbial communities from acidic subsurface sediments contaminated with uranium(VI). Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69, 7467–7479. doi: 10.1128/AEM.69.12.7467-7479.2003

Pratt, A. R., Muir, I. J., and Nesbitt, H. W. (1994). X-ray photoelectron and Auger electron spectroscopic studies of pyrrhotite and mechanism of air oxidation. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 58, 827–841. doi: 10.1016/0016-7037(94)90508-8

Quast, C., Pruesse, E., Yilmaz, P., Gerken, J., Schweer, T., Yarza, P., et al. (2013). The SILVA ribosomal RNA gene database project: improved data processing and web-based tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 41, D590–D596. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks1219

Ray, A. E., Bargar, J. R., Sivaswamy, V., Dohnalkova, A. C., Fujita, Y., Peyton, B. M., et al. (2011). Evidence for multiple modes of uranium immobilization by an anaerobic bacterium. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 75, 2684–2695. doi: 10.1016/j.gca.2011.02.040

Ray, A. E., Connon, S. A., Sheridan, P. P., Gilbreath, J., Shields, M., Newby, D. T., et al. (2010). Intragenomic heterogeneity of the 16S rRNA gene in strain UFO1 caused by a 100 bp insertion in helix 6. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 72, 343–353. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6941.2010.00868.x

Reasoner, D. J., and Geldreich, E. E. (1985). A new medium for the enumeration and subculture of bacteria from potable water. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 49, 1–7.

Riley, R. G., Zachara, J. M., and Wobber, F. J. (1992). Chemical Contaminants on DOE Lands and Selection of Contaminant Mixtures for Subsurface Research. Washington, DC: US-DOE.

Sani, R. K., Peyton, B. M., Smith, W. A., Apel, W. A., and Petersen, J. N. (2002). Dissimilatory reduction of Cr(VI), Fe(III), and U(VI) by Cellulomonas isolates. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 60, 192–199. doi: 10.1007/s00253-002-1069-6

Schauder, R., and Schink, B. (1989). Anaerovibrio glycerini sp. nov., an anaerobic bacterium fermenting glycerol to propionate, cell matter, and hydrogen. Arch. Microbiol. 152, 473–478. doi: 10.1007/BF00446932

Schleifer, K. H., and Kandler, O. (1972). Peptidoglycan types of bacterial cell walls and their taxonomic implications. Bacteriol. Rev. 36, 407–477.

Schwertmann, U., and Cornell, R. M. (2000). Iron Oxides in the Laboratory: Preparation and Characterization. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH. doi: 10.1002/9783527613229

Scott, D. T., McKnight, D. M., Blunt-Harris, E. L., Kolesar, S. E., and Lovley, D. R. (1998). Quinone moieties act as electron acceptors in the reduction of humic substances by humics-reducing microorganisms. Environ. Sci. Technol. 32, 2984–2989. doi: 10.1021/es980272q

Shelobolina, E. S., Nevin, K. P., Blakeney-Hayward, J. D., Johnsen, C. V., Plaia, T. W., Krader, P., et al. (2007). Geobacter pickeringii sp. nov., Geobacter argillaceus sp. nov. and Pelosinus fermentans gen. nov., sp. nov., isolated from subsurface kaolin lenses. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 57, 126–135. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.64221-0

Shen, H., and Wang, Y. T. (1993). Characterization of enzymatic reduction of hexavalent chromium by Escherichia coli ATCC 33456. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 59, 3771–3777.

Shirley, D. A. (1972). High-resolution X-ray photoemission spectrum of the valence bands of gold. Phys. Rev. B 5, 4709–4714. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.5.4709

Stankewich, J. P., Cosenza, B. J., and Shigo, A. L. (1971). Clostridium quercicolum, sp. nov., isolated from discolored tissues in living oak trees. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 37, 299–302. doi: 10.1007/BF02218500

Strompl, C., Tindall, B. J., Jarvis, G. N., Lunsdorf, H., Moore, E. R. B., and Hippe, H. (1999). A re-evaluation of the taxonomy of the genus Anaerovibrio, with the reclassification of Anaerovibrio glycerini as Anaerosinus glycerini gen. nov., comb. nov., and Anaerovibrio burkinabensis as Anaeroarcus burkinensis [corrig.] gen. nov., comb. nov. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 49, 1861–1872. doi: 10.1099/00207713-49-4-1861

Strompl, C., Tindall, B. J., Lunsdorf, H., Wong, T. Y., Moore, E. R. B., and Hippe, H. (2000). Reclassification of Clostridium quercicolum as Dendrosporobacter quercicolus gen. nov., comb. nov. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 50, 101–106. doi: 10.1099/00207713-50-1-101

Strunk, O., Ludwig, W., Gross, O., Reichel, B., May, M., Hermann, S., et al. (1996). ARB—a Software Environment for Sequence Data, 2.5b. Munich: Technical University of Munich.

Swift, P. (1982). Adventitious carbon–the panacea for energy referencing? Surf. Interface Anal. 4, 47–51. doi: 10.1002/sia.740040204

Tabak, H., Lens, P., van Hullebusch, E., and Dejonghe, W. (2005). Developments in bioremediation of soils and sediments polluted with metals and radionuclides – 1. Microbial processes and mechanisms affecting bioremediation of metal contamination and influencing metal toxicity and transport. Rev. Environ. Sci. Biotechnol. 4, 115–156. doi: 10.1007/s11157-005-2169-4

Takeno, N. (2005). Atlas of Eh-pH diagrams. Intercomparison of thermodynamic databases. Geol. Surv. Japan Open File Rep. 419:285.

Thorgersen, M. P., Lancaster, W. A., Rajeev, L., Ge, X., Vaccaro, B. J., Poole, F. L., et al. (2017). A highly expressed high-molecular-weight S-layer complex of Pelosinus sp. strain ufo1 binds uranium. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 83:e03044-16. doi: 10.1128/AEM.03044-16

Tourova, T. P., Kuznetzov, B. B., Novikova, E. V., Poltaraus, A. B., and Nazina, T. N. (2001). Heterogeneity of the nucleotide sequences of the 16S rRNA genes of the type strain of Desulfotomaculum kuznetsovii. Microbiology 70, 678–684. doi: 10.1023/A:1013135831669

USDOE (1997). Linking Legacies Report: Connecting the Cold War Nuclear Weapons Production Processes to Their Environmental Consequences. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Energy.

Velásquez, L., and Dussan, J. (2009). Biosorption and bioaccumulation of heavy metals on dead and living biomass of Bacillus sphaericus. J. Hazard. Mater. 167, 713–716. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2009.01.044

Wayne, L. G., Brenner, D. J., Colwell, R. R., Grimont, P. A. D., Kandler, O., Krichevsky, M. I., et al. (1987). Report of the ad hoc committee on reconcilication of approaches to bacterial systematics. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 37, 463–464. doi: 10.1099/00207713-37-4-463

White, C., Sayer, J. A., and Gadd, G. M. (1997). Microbial solubilization and immobilization of toxic metals: key biogeochemical processes for treatment of contamination. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 20, 503–516. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.1997.tb00333.x

Wolf, M., Kappler, A., Jiang, J., and Meckenstock, R. U. (2009). Effects of humic substances and quinones at low concentrations on ferrihydrite reduction by Geobacter metallireducens. Environ. Sci. Technol. 43, 5679–5685. doi: 10.1021/es803647r

Woo, P. C. Y., Teng, J. L. L., Leung, K. W., Lau, S. K. P., Woo, G. K. S., Wong, A. C. Y., et al. (2005). Anaerospora hongkongensis gen. nov. sp. nov., a novel genus and species with ribosomal DNA operon heterogeneity isolated from an intravenous drug abuser with pseudobacteremia. Microbiol. Immunol. 49, 31–39. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.2005.tb03637.x

Keywords: toxic metal reduction, bioremediation, subsurface environment, fermentative bacterium, Pelosinus

Citation: Ray AE, Connon SA, Neal AL, Fujita Y, Cummings DE, Ingram JC and Magnuson TS (2018) Metal Transformation by a Novel Pelosinus Isolate From a Subsurface Environment. Front. Microbiol. 9:1689. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.01689

Received: 29 December 2017; Accepted: 06 July 2018;

Published: 17 August 2018.

Edited by:

Pankaj Kumar Arora, Babasaheb Bhimrao Ambedkar University, IndiaReviewed by:

Ramprasad E.V.V., University of Hyderabad, IndiaBärbel Ulrike Fösel, Helmholtz Zentrum München and Helmholtz-Gemeinschaft Deutscher Forschungszentren (HZ), Germany

Copyright © 2018 Ray, Connon, Neal, Fujita, Cummings, Ingram and Magnuson. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Timothy S. Magnuson, bWFnbnRpbW9AaXN1LmVkdQ==

†Present address: Andrew L. Neal, Department of Sustainable Soils and Grassland Systems, Rothamsted Research, Hertfordshire, United Kingdom; Jani C. Ingram, Department of Chemistry & Biochemistry, Northern Arizona University, Flagstaff, AZ, United States

Allison E. Ray

Allison E. Ray Stephanie A. Connon

Stephanie A. Connon Andrew L. Neal

Andrew L. Neal Yoshiko Fujita2

Yoshiko Fujita2 David E. Cummings

David E. Cummings Jani C. Ingram

Jani C. Ingram Timothy S. Magnuson

Timothy S. Magnuson