- 1State Key Laboratory of Pharmaceutical Biotechnology, School of Life Sciences, Nanjing University, Nanjing, China

- 2State Key Laboratory for Mineral Deposits Research, School of Earth Sciences and Engineering, Nanjing University, Nanjing, China

- 3Key Laboratory of Mesoscopic Chemistry of MOE and Collaborative Innovation Center of Chemistry for Life Sciences, School of Chemistry and Chemical Engineering, Nanjing, China

Pseudomonas putida (P. putida) MnB1 is a widely used model strain in environment science and technology for determining microbial manganese oxidation. Numerous studies have demonstrated that the growth and metabolism of P. putida MnB1 are influenced by various environmental factors. In this study, we investigated the effects of hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) and manganese (Mn2+) on proliferation, Mn2+ acquisition, anti-oxidative system, and biofilm formation of P. putida MnB1. The related orthologs of 4 genes, mco, mntABC, sod, and bifA, were amplified from P. putida GB1 and their involvement were assayed, respectively. We found that P. putida MnB1 degraded H2O2, and quickly recovered for proliferation, but its intracellular oxidative stress state was maintained, with rapid biofilm formation after H2O2 depletion. The data from mco, mntABC, sod and bifA expression levels by qRT-PCR, elucidated a sensitivity toward bifA-mediated biofilm formation, in contrary to intracellular anti-oxidative system under H2O2 exposure. Meanwhile, Mn2+ ion supply inhibited biofilm formation of P. putida MnB1. The expression pattern of these genes showed that Mn2+ ion supply likely functioned to modulate biofilm formation rather than only acting as nutrient substrate for P. putida MnB1. Furthermore, blockade of BifA activity by GTP increased the formation and development of biofilms during H2O2 exposure, while converse response to Mn2+ ion supply was evident. These distinct cellular responses to H2O2 and Mn2+ provide insights on the common mechanism by which environmental microorganisms may be protected from exogenous factors. We postulate that BifA-mediated biofilm formation but not intracellular anti-oxidative system may be a primary protective strategy adopted by P. putida MnB1. These findings will highlight the understanding of microbial adaptation mechanisms to distinct environmental stresses.

Introduction

Environmental stresses, such as nutrient depletion, extreme temperature and pressure, high salinity, strong ultraviolet light, and radiation, commonly induce microbes to produce cellular oxidative stress with overproduction of reactive oxygen species (ROS) (Teitzel and Parsek, 2003; Matallana-Surget et al., 2009; Chattopadhyay et al., 2011; Murata et al., 2011; Chen et al., 2013). Excessive ROS generation can injure proteins, DNAs and lipids, resulting in gene mutation and cell death (Cabiscol et al., 2000; Green and Paget, 2004; Lewis, 2008; Calabrese et al., 2011; Pan, 2011; Cap et al., 2012; Imlay, 2013; Chua et al., 2016). While low or moderate levels of ROS-induced physiological and biochemical changes are able to achieve an adaptation to the surrounding environment (Sies, 2017). Therefore, microorganisms have developed diverse mechanisms to respond to external ROS stimuli. For most microbial pathogens, the two primary mechanistic adaptations in response to ROS are excitation of anti-oxidative system (Apel and Hirt, 2004) and the formation of biofilms (Kubota et al., 2008). However, for non-pathogenic environmental microorganisms, the mechanistic basis for response to ROS (e.g., tolerance or scavenging) is less well understood.

Microbes in natural environments play important roles in global geochemical cycling, biodegradation of contaminants, and biofouling in the maintenance and evolution of local and global environments (Falkowski et al., 2008; Borch et al., 2010). ROS production in microbes during pathological condition is transient and moderate, while their exposure to consequent adverse factors in environments, results in oxidative stress (Cabiscol et al., 2000; Green and Paget, 2004; Matallana-Surget et al., 2009; Chattopadhyay et al., 2011; Murata et al., 2011; Chen et al., 2013; Imlay, 2013). Of note, microbes acquire energy by uptake of organic matter and redox reaction that take place on the transition metal ions in environment, sometimes producing secondary minerals (Rajkumar and Freitas, 2008; Soldatova et al., 2017). These physiological adaptation strategies allow microbes to survive in changing environments.

Manganese (Mn), as one of the most abundant transition metals in the earth’s crust, is encountered by microbes in the soil, water and atmosphere. In natural water, the concentration of Mn2+ ion ranges from 0.2 ∼ 3 mM (Humphris et al., 1996). Microbial Mn (II) oxidation is the major driving force in the biological formation of manganese oxide, controlling the Mn cycling in natural environments (Nealson et al., 1988; Handley and Lloyd, 2013). The direct oxidation and acquisition of Mn2+ are performed by manganese oxidase (MCO) (Brouwers et al., 1999, 2000; Francis and Tebo, 2001) and manganese transporter (Mnt) (Courville et al., 2006; Nevo and Nelson, 2006; Rees et al., 2009), respectively. In many microbes, Mn acts as a crucial trace nutrient for energy generation through Mn2+ oxidation (Cailliatte et al., 2010), which is influenced by diverse environmental factors, such as O2 levels, temperature, light, salinity and Mn2+ concentration (Hansel, 2017). Mn2+ in microbes also plays an important role in their adaptive response to intracellular and environmental condition changes (Kolenbrander et al., 1998; Loo et al., 2003; Papp-Wallace and Maguire, 2006; Juttukonda et al., 2016; Colomer-Winter et al., 2017; Qin et al., 2017), such as protections against oxidative damage (Latour, 2015) by functioning as a reducing reagent (Mahal et al., 2005), superoxide dismutase (SOD) mimic (Reboucas et al., 2008; Kelso et al., 2012) or SOD cofactor (Kim et al., 1999; Tseng et al., 2001). The uptake and utilization of Mn2+ by microbes favor adaptation to nutrient stresses (Cailliatte et al., 2010; Juttukonda et al., 2016) and defense against oxidative stresses (Kehl-Fie et al., 2013; Latour, 2015; Colomer-Winter et al., 2017). Modulation of Mnts balances Mn2+ availability, protects from the toxicity of excess Mn2+ (Qin et al., 2017), and affects microbial growth (Cailliatte et al., 2010), infection (Papp-Wallace and Maguire, 2006) and biofilm formation (Kolenbrander et al., 1998; Loo et al., 2003). Therefore, Mn oxidizing microbe is a good model for investigating the adaptive mechanisms when facing environmental stresses.

Pseudomonas putida (P. putida) MnB1, a prototype strain of the widely distributed P. putida species, has been widely used as a model strain for studying microbial Mn (II) oxidation in geochemical processes (Caspi et al., 1998; Villalobos et al., 2003; Toner et al., 2005; Parker et al., 2014). Numerous studies have been focused on the adsorption capacity of heavy metals and the formation of biogenic manganese minerals by P. putida MnB1 or P. putida GB1 (highly homologous to P. putida MnB1), which have successfully contributed to the environmental restoration of water, soil, and sediments (Villalobos et al., 2005; Sasaki et al., 2008; Meng et al., 2009; Forrez et al., 2011; Kim et al., 2012). Even though P. putida species are known to survive diverse exogenous stress factors, including heavy metal pollutants, superoxide (Lee et al., 2006; Park et al., 2006; Chavarria et al., 2013), antibiotics (Yeom et al., 2010), and organic compounds (Raiger-Iustman and Ruiz, 2008; Fernandez et al., 2012; Tavita et al., 2012; Lee et al., 2014), how P. putida MnB1 survives environmental stresses is not fully understood (Manara et al., 2012; Banh et al., 2013; Nikel et al., 2013; Ray et al., 2013).

It is known that P. putida biofilm formation correlates with adaptation and persistence in response to environmental stresses, in which cyclic diguanylate (c-di-GMP) signaling plays an essential role (Gjermansen et al., 2006; Matilla et al., 2011; Lee et al., 2016; Sun et al., 2017). c-di-GMP acts as a second messenger that modulates the planktonic to adhesive lifestyle switch, influencing virulence, infection and antibiotic resistance in pathogen (Romling et al., 2013). Generally, a rise in intracellular c-di-GMP promotes biofilm formation, while a decrease in c-di-GMP increases high exercise and dispersal (Wolfe and Visick, 2008; Borlee et al., 2010). Synthesis and hydrolysis of c-di-GMP are catalyzed by diguanylate cyclases (DGCs) and c-di-GMP-specific phosphodiesterases (PDEs), respectively. The role of c-di-GMP-specific PDE, BifA, in biofilm formation has been described in P. putida (Jimenez-Fernandez et al., 2015), P. aeruginosa (Kuchma et al., 2007), and P. syringae (Aragon et al., 2015). In these Pseudomonas species, bifA genes display a high degree of similarity and the proteins possess EAL domains that are essential for c-di-GMP-specific PDE activity. Carbon starvation is reported to induce biofilm collapse, which is directly related to BifA PDE activity of P. putida (Gjermansen et al., 2005; Lopez-Sanchez et al., 2013). ΔbifA mutants increase biofilm formation in Pseudomonas species, and meanwhile exhibit reduction of starvation-induced biofilm dispersal in P. putida KT2442 (Jimenez-Fernandez et al., 2015), flagella-mediated motility in P. aeruginosa (Kuchma et al., 2007), and motility and virulence in P. syringae (Aragon et al., 2015). These observations indicate that c-di-GMP-specific PDEs are modulated by various environmental and/or intracellular signals to affect the microbe function (Gjermansen et al., 2005; Fang et al., 2014).

Several lines of evidence imply that the modulation of c-di-GMP-specific PDE closely interrelates with the cellular anti-oxidative system (Huang et al., 2013; Chua et al., 2016; Strempel et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2017), and responds to the presence of Mn2+ ion (Bobrov et al., 2005; Schmidt et al., 2005; Tamayo et al., 2005; Miner and Kurtz, 2016). Exposure to hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) for more than 120 generations increases rough and small colony variants (RSCV) in pathogenic P. aeruginosa (Chua et al., 2016). The appearance of RSCV, considered as a pre-biofilm form, increases microbial susceptibility to exogenous H2O2, which is restored by antioxidant L-glutathione treatment (Chua et al., 2016). Furthermore, H2O2 exposure leads to mutation in the WspF gene (encoded a c-di-GMP-specific PDE) that increases cellular c-di-GMP concentrations (Chua et al., 2016). Deletion of the yjcC gene (encoded a c-di-GMP-specific PDE) in Klebsiella pneumoniae increases sensitivity to H2O2 stress and decreases survival rate (Huang et al., 2013). Furthermore, ROS over-production causes the overwhelming formation of biofilms in Klebsiella pneumoniae CG43 (Huang et al., 2013). The phytopathogen Xylella fastidiosa with a mutation in the oxidative stress regulatory protein OxyR, exhibits more sensitive to H2O2 exposure but defective in biofilm maturation, suggesting that ROS may be an environmental cue to stimulate biofilm formation during host invasion (Wang et al., 2017). Therefore, c-di-GMP-specific PDE-mediated biofilm formation and intracellular anti-oxidative system may be closely associated with H2O2 stress. Moreover, c-di-GMP-specific PDE responds to Mn2+ ion (Bobrov et al., 2005; Schmidt et al., 2005; Tamayo et al., 2005; Miner and Kurtz, 2016) with significant effect on biofilm formation in pathogenic Yersinia pestis (Bobrov et al., 2005), Vibrio cholera (Tamayo et al., 2005), Eschericia coli (Schmidt et al., 2005), as well as in various environmental microbes, e.g., Thermotoga maritima (Miner and Kurtz, 2016).

In natural environments, microorganisms are commonly exposed to oxidative stresses (Cooper et al., 1988; Mopper and Zhou, 1990; Hakkinen et al., 2004; Kaur and Schoonen, 2017) in which a variety of substances (e.g., pyrite, manganese oxides, and pyrithione) spontaneously react with molecular oxygen to produce H2O2 (Borda et al., 2001; Schoonen et al., 2010; Kong et al., 2015), especially with the mediation of light (Mopper and Zhou, 1990; Zuo and Deng, 1999) and organic substances (Zuo and Hoigne, 1993). In this study, the effects of H2O2 and Mn2+ ion on growth, Mn2+ acquisition, anti-oxidative system and biofilm formation by P. putida MnB1 were assayed. A comparison of cellular response to H2O2 and Mn2+ ion in environmental microbes has the potential to provide insight into a universal mechanism to protect against exogenous stresses and adapt to changing environments.

Materials and Methods

Bacterial Strain

The P. putida MnB1 strain was provided by the China General Microbiological Culture Collection Center (CGMCC). P. putida MnB1 was cultivated in LEP medium (0.50 g yeast powder, 0.50 g acid hydrolyzed casein, 1.00 g glucose, 222 mg CaCl2, 0.39 g MgSO4, 1 mg FeCl3, 2.38 g HEPES (N-2-hydroxyethlpiperazine-N′-2-ethanesulfonic acid) (pH 7.5) per liter, containing 1 mL trace element solution (10 mg/L CaSO4⋅5H2O, 44 mg/L ZnSO4⋅7H2O, 20 mg/L CoCl2⋅6H2O, and 13 mg/L Na2MoO4⋅2H2O) (Boogerd and Devrind, 1987). The cultures were performed in 250 mL glass flasks at 30°C with shaking at 120 r/min.

Cell Growth and Proliferation Monitoring

For measurement of cell growth, 25 mL cultures with a density of approximately 1 × 106 cells/mL were incubated in LEP medium containing MnCl2 (0, 40, 200, 1000, and 5000 μM) or H2O2 (0, 40, 200, and 1000 μM) and monitored. The cultures were incubated with shaking at 30°C. The absorbance was measured at 600 nm (OD600) every 3 h for up to 48 h.

H2O2 Scavenging Capacity

H2O2 concentrations remaining in cultures were assessed with a commercial H2O2 detection kit (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology, Haimen, China). The detected maximum concentration of H2O2 in nature is 400 μM (Gunz and Hoffmann, 1990; Mopper and Zhou, 1990; Borda et al., 2001; Schoonen et al., 2010). Therefore, cells were incubated in LEP medium containing H2O2 (40, 200, and 1000 μM) for 24 h at 30°C with shaking. Cell cultures were harvested every 3 h and centrifuged (10,000 rpm, 30 s) and supernatants were collected. Following the protocol provided by the manufacturer, the absorbance at 560 nm was measured for detection of H2O2 concentration by the xylenol orange reaction.

Inactivated P. putida MnB1 was employed as a control to verify bio-degradation of the microbes on exogenous H2O2. P. putida MnB1 was inactivated in a water bath at 80°C for 30 min. H2O2 (1000 μM) was incubated in LEP medium with alive cells, inactivated cells, or in the absence of cells at 30°C with shaking. The culture supernatants were collected at 3 and 6 h, respectively. The xylenol orange reaction was conducted in polystyrene, flat-bottom, 96-well microplates in 3 replicates.

Biofilm Observation and Qualification

Cell suspensions (1.5 mL) were inoculated in 6-well plates at a density of 1 × 106 cells/mL. Coverslips and rhodochrosite slices (0.5 × 0.5 × 0.1 cm) were placed on the bottom of the plates and incubated at 30°C without shaking. After cell adhesion for 6 and 12 h, H2O2 (200 μM) was added to the cultures and incubated for another 2 h. Then coverslips and rhodochrosite slices were taken out and rinsed with phosphate buffer saline (PBS) for three times. Specimens were fixed with 2.5% glutaraldehyde and dehydrated in a graded ethanol series (30, 50, 70, 80, 90, and 100%) for 15 min each after rinsing 3 times. Finally, the samples were frozen at −80°C for 2 h and vacuum dried for 48 h. The samples were coated with platinum in a JEOL JFC-1600 auto fine coater device. Microbes colonized on glass coverslips or rhodochrosite slices were observed using a field emission scanning electron microscope (FESEM, Zeiss Supra55, Germany) at the State Key Laboratory for Mineral Deposits Research in Nanjing University.

Quantification of biofilm formation by P. putida MnB1 was conducted in polystyrene, flat-bottom, 96-well microplates (Thermo ScientificTM NuncTM MicroWellTM Cell-Culture Treated Microplates) with 5 replicates. A 100 μL (1 × 106 cells/mL) cell suspension was incubated in LEP medium containing H2O2 (0, 40, and 200 μM) or MnCl2 (0, 40, 200, 1000, and 5000 μM) at 30°C without shaking for 6 and 12 h, respectively. After supernatants were removed, the biofilms were rinsed three times with PBS and stained with 100 μL of 0.1% (w/v) crystal violet (CV) for 15 min (Sule et al., 2009). CV was removed and the biofilms were rinsed three times before air drying. 100 μL of acetic acid (33%) was added to the biofilms, followed by a 30 min-incubation at 37°C to resolve CV completely. The solution was diluted (1:10) before measuring OD590 with a Safire Microplate Reader (Tecan Group Ltd., Mannedorf, Switzerland) to quantify the amount of CV absorbed by the biofilms.

The effect of H2O2 on biofilm formation after cell adhesion onto solid surfaces was investigated with a confocal laser scanning microscope (CLSM, Leica TCS SP8, Germany) at the State Key Laboratory of Pharmaceutical Biotechnology of Nanjing University. P. putida MnB1 cell cultures (1.5 mL) were inoculated into a 6-well plate at a density of 1 × 106 cells/mL. A coverslip was placed on the bottom of the plate and incubated at 30°C for 6 and 12 h without shaking. After adhesion, H2O2 (0, 40, and 200 μM) was added to the culture for another 2 h. Then coverslips were taken out and rinsed three times with sterile deionized water. The colonized cells were stained with 1.0 mL of PBS containing 3.0 μL of STYO9 (3.34 mM) (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, United States) for 20 min and washed three times with sterile deionized water. The prepared coverslips were fixed onto glass slides, and observed with the excitation and emission wavelength of 480 and 500 nm, respectively. The number of fluorescently labeled cells on the glass coverslips was quantified.

Determination of Cellular Levels of ROS, SOD and Catalase Activity

For detection of catalase (CAT) activity in P. putida MnB1, 10 μL H2O2 (9.7 M) was added to a 10 μL cell suspension to observe bubble formation, in which H2O2 yielded H2O and O2, indicating the existence of CAT activity. Suspensions containing inactive cells (water bath at 80°C for 30 min), and cell culture after removing bacteria by 0.22 μm filtration were served as controls. Bubble formation was visualized by use of a Dissecting Microscope (Olympus SZ61 Stereo Microscope, Japan).

Total ROS was assessed with 10 μM 2′,7′-dichlorofluorescein diacetate (DCFH-DA, Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology, Haimen, China). 0.5 mL of cell suspension was placed in a 12-well plate at a density of 1 × 107 cells/mL. Cell suspensions were incubated with LEP medium containing 200 μM H2O2 at 30°C without shaking for 3, 6, and 12 h. Following H2O2 treatment, the cells were harvested and incubated with DCFH-DA at 25°C for 30 min and then washed twice with PBS. The intensity of the fluorescent signal was analyzed with an excitation wavelength of 488 nm and monitoring the emission wavelength of 525 nm.

Following the H2O2 treatment similar to that of the ROS detection, cell lysates were harvested by liquid nitrogen freeze-thaw (three times) in lysis buffer (Beyotime Biotech, Nanjing, China). The supernatants were obtained by centrifugation (12,000 rpm, 3 min) to determine SOD and CAT activity (Beyotime Biotechnology, Haimen, China) by the WST-8 and the colorimetric method, according to the manufacturer’s instructions, respectively. The total ROS level, CAT, and SOD activity were calibrated and protein concentrations determined using a BCA protein assay kit (Beyotime Biotechnology, Haimen, China).

Genomic DNA Extraction, Gene Amplification, and Alignment

The whole genomic DNA was isolated following the manufacturer’s instructions (BioTeke Corporation, Beijing, China). Cells in logarithmic phase (2 × 109 cells in 2 mL) were centrifuged (10,000 rpm, 30 s) and the supernatants were discarded. After repeating centrifugation, the cells were re-suspended in 200 μL of Lysis Buffer A. 5 μL of lysozyme (10 mg/mL, dissolved in 10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0) was added, mixed, and incubated at 37°C for 15 min. After the addition of 200 μL of Lysis Buffer B, the samples were immediately mixed and then treated with protease K (20 μL, 20 mg/mL) at 70°C for 10 min. After isopropanol precipitation and adsorption with Colum AC, the pellets were rinsed with Liquid Wash Buffer and then re-suspended in Liquid Elution Buffer. The extracted genomic DNA was preserved at −20°C for gene amplification.

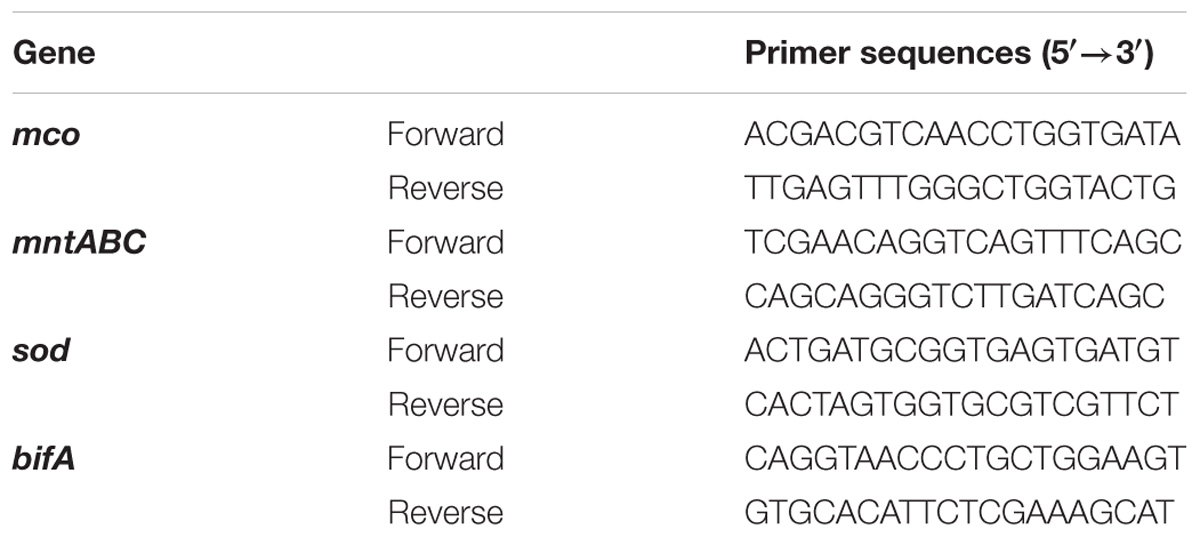

Primers of the following gene orthologs – mco, mntABC, sod, and bifA were designed according to the GenBank whole genome of P. putida GB-1. The primers used for qRT-PCR were synthesized by SunShine Biotechnology (Nanjing, China) and listed in Table 1. The homology of gene and protein sequences (Table 2) were performed by using the alignment search algorithms BLASTN and BLASTX1 and compared to the encoded genes and proteins in P. putida KT2440 (NC_002947.4) and P. putida GB-1 (NC_010322.1).

RNA Extraction and Quantitative Reverse Transcription-Polymerase Chain Reaction (qRT-PCR) Analysis

Planktonic and colonized cells were collected from flask and 6-well plates, respectively. 1.0 mL of cell cultures (1 × 106 cells/mL) were seeded into 100 mL LEP medium and incubated at 30°C with 120 r/min shaking. After 3, 6, 12, and 24 h of cultivation, 2.0 mL cell cultures were harvested by centrifugation at 10,000 rpm for 30 s. The precipitated cells were suspended and rinsed with PBS for three times. These planktonic cells were used for qRT-PCR assay. Cell cultures (1 × 106 cells/mL in 1.5 mL) were seeded into 6-well plates and incubated at 30°C without shaking. After 3, 6, 12, and 24 h of cultivation, the upper culture medium and the floating cells were discarded, the adhesive cells were collected for qRT-PCR assay.

Modulations of gene expression in the biofilm cells treated with exogenous H2O2 and MnCl2 were assayed. Cells were seeded into 6-well plates (1 × 106 cells/well) and incubated at 30°C without shaking to allow biofilm formation. After 6, 12, and 24 h of cultivation for adhesion, microbes were incubated with H2O2 (0, 200 μM) or MnCl2 (0, 200 μM) for another 2 h. The supernatants and the floating cells were removed to collect the adhesive cells for qRT-PCR assay.

Total RNA was isolated with Trizol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, United States) according to the manufacturer’s instructions (n = 5/group). cDNA was synthesized in real time (RT) buffer with MultiScribe reverse transcriptase, and dNTPs (Promega, Madison, WI, United States). Relative mRNA expression was normalized to 16S rRNA. qRT-PCR analysis of mRNA was performed using SYBR Green I dye (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, United States) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The reaction mixture was incubated in a CFX96 Real-Time PCR Detection System (Bio-Rad) (30 s at 94°C followed by 45 cycles of 1 s at 94°C, 15 s at 55°C and 10 s at 72°C). Measurement of the fluorescence signal generated with SYBR Green I DNA dye was conducted at the annealing steps. Specificity of the amplification was confirmed by melting curve analysis. Data were collected and processed by CFX Manager Software (Bio-Rad), and expressed as a function of threshold cycle (Ct). The samples for qRT-PCR analysis were evaluated using a single predominant peak for quality control. The comparative Ct (2−ΔΔCt) method was used for analysis of relative mRNA expression, normalized to 16S rRNA.

GTP Inhibition Evaluation

To investigate the role of BifA in P. putida MnB1, biofilm development was evaluated in the presence or absence of GTP, a potential inhibitor of c-di-GMP specific PDE (Ross et al., 1990; Barraud et al., 2009). Cells were seeded into 6-well plates (1 × 106 cells/well) with and without 250 μM GTP pre-treatment. After 6 h or 12 h incubation, exogenous H2O2 (40, 200, and 1000 μM) or MnCl2 (40, 200, and 1000 μM) were added into the cell culture, respectively. After further incubation for 2 h, biofilm formation was validated by CV staining.

Statistical Analysis

The data were presented as the mean ± SEM. Statistical analysis was performed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by the Dunnett’s Multiple Comparison Test. A value of P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Bacterial Growth and H2O2 Bio-Degradation

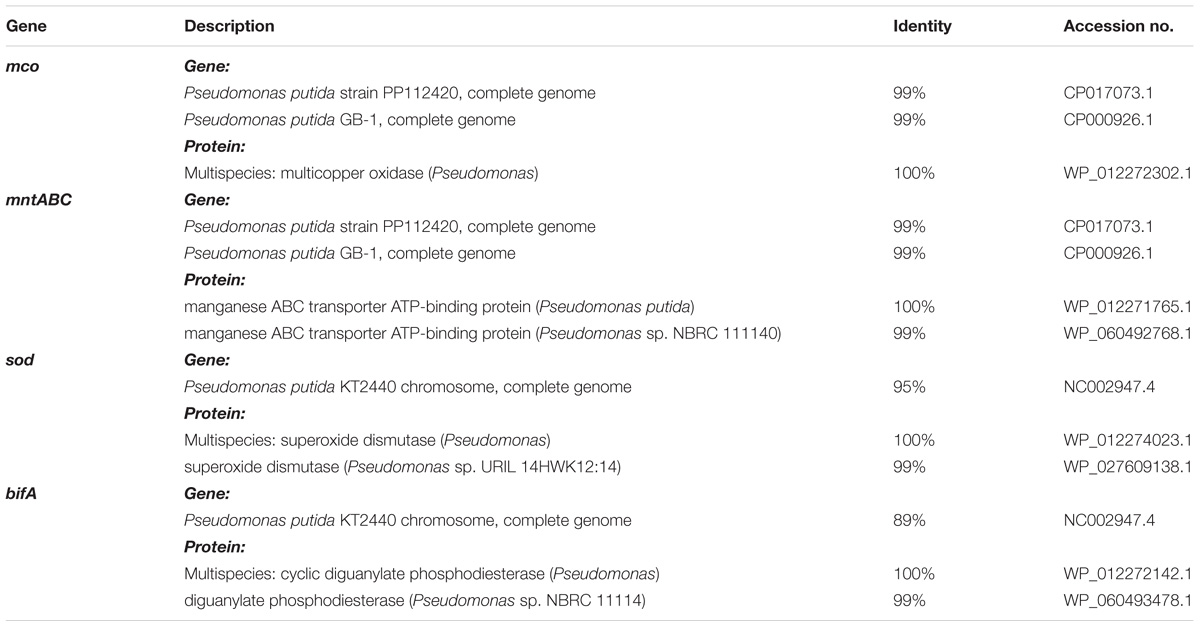

As shown in Figure 1A, 40 μM H2O2 had little effect on proliferation of P. putida MnB1. With 200 μM H2O2, there was a slight retardation in proliferation during the early logarithmic phase. When H2O2 was increased to 1000 μM, proliferation during the first 24 h was remarkably suppressed, although biomass was quickly increased and then exceeded that of other groups at 24 h. H2O2 at the 3 tested dosages was degraded completely within 6 h by P. putida MnB1 (Figure 1B), whereas little H2O2 was decomposed within 6 h by dead cells or in medium alone (Figure 1C). Changes in proliferation indicated a defensive mechanism in P. putida MnB1 in response to exogenous H2O2. Since there was no significant change in proliferation of P. putida MnB1 at 40 and 200 μM of H2O2, these working concentrations were employed for the following experiments.

FIGURE 1. Exogenous H2O2 did not inhibit the growth of P. putida MnB1, but was bio-degraded quickly by P. putida MnB1. (A) Cells were incubated with 0, 40, 200, and 1000 μM H2O2, respectively. Growth of P. putida MnB1 was detected by measuring the absorbance at 600 nm (n = 3). (B) The concentration of H2O2 in culture with P. putida MnB1was assayed by the xylenol orange reaction (n = 3). (C) H2O2 concentration (initial concentration of 1000 μM) in LEP medium was assayed in the presence or absence of alive P. putida MnB1 or inactivated microbes, respectively. The supernatant of the cell culture was reacted with xylenol orange. Data were expressed as mean ± SEM. Significance, ∗∗P < 0.01 and ∗∗∗P < 0.001 vs. control group (0 μM H2O2).

Biofilm Formation With Exogenous H2O2

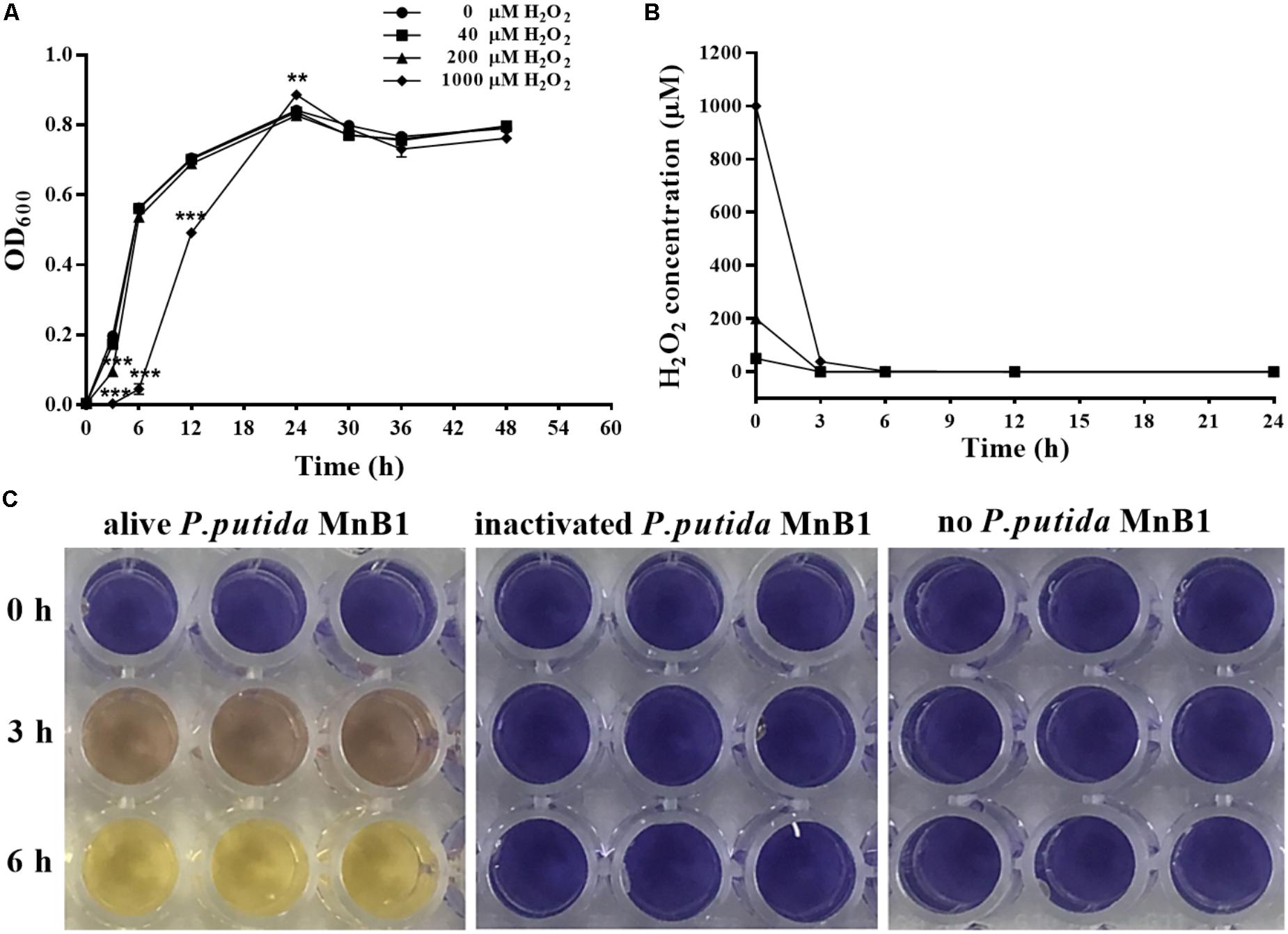

Biofilm formation was investigated by CV staining. Based on preliminary data, biofilm formation could be detected before 3 h and the absorbance at OD590 was maintained steadily between 12 and 48 h. Therefore, most of our experiments were conducted before 12 h, which is defined as the earlier development stage before maturation (O’Toole and Kolter, 1998).

In this study, P. putida MnB1 was pre-cultivated in 96-well plates for 6 h or 12 h before exposure to H2O2. Biofilm biomass in the first 6 h was evidently promoted in the group with 200 μM H2O2 (Figure 2A). However, no distinct changes were observed at 12 h with 40 or 200 μM H2O2 exposure (Figure 2B). By integrating with the concentration changes of H2O2 within 6 h (Figure 1B), it was deduced that the promotion of H2O2 on the biofilm formation at earlier stage was pronounced.

FIGURE 2. Effect of exogenous H2O2 on the biofilm formation by P. putida MnB1. Biofilm formation by P. putida MnB1 was quantified by CV staining with absorbance at 590 nm. Cells were incubated with H2O2 (0, 40, and 200 μM) for 6 h (A) and 12 h (B) (n = 6), respectively. Data were expressed as mean ± SEM. Significance, ∗∗∗P < 0.001 vs. control group (0 μM H2O2).

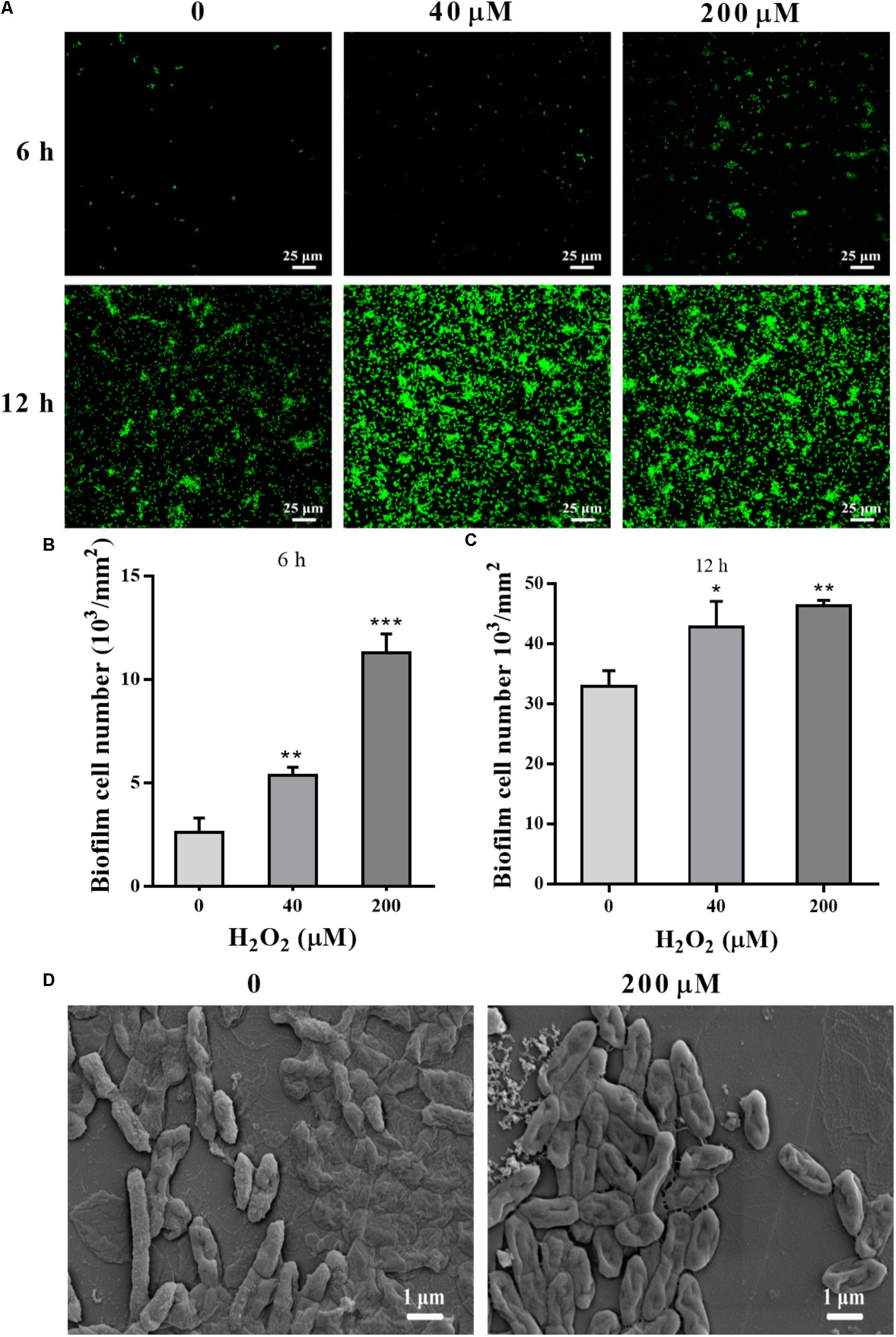

STYO 9 staining also showed that 40 and 200 μM H2O2 increased biofilm formation at 6 and 12 h on glass coverslips (Figures 3A–C). When the adhesion substrate was rhodochrosite, FESEM images showed nanowire development in H2O2-treated group besides of biofilm formation (Figure 3D).

FIGURE 3. Confocal and FESEM observation of P. putida MnB1 biofilm formation with exogenous H2O2. After 6 and 12 h cultivation for adhesion, cells were incubated with H2O2 (0, 40, and 200 μM) for another 2 h, respectively. (A) Confocal observation of biofilm formation onto glass coverslips by STYO 9 staining (scale bar, 25 μm). Fluorescently labeled biofilm cells on the glass coverslips after incubation for 6 h (B) and 12 h (C) were quantified (field of vision, 276.79 × 276.79 μm) (n = 3). (D) FESEM images of P. putida MnB1 adhered to rhodochrosite with and without 200 μM H2O2 incubation for 12 h (scale bar, 1 μm). Data were expressed as mean ± SEM. Significance, ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01, and ∗∗∗P < 0.001 vs. control group (0 μM H2O2).

Intracellular ROS Levels and Anti-oxidative System With Exogenous H2O2 Treatment

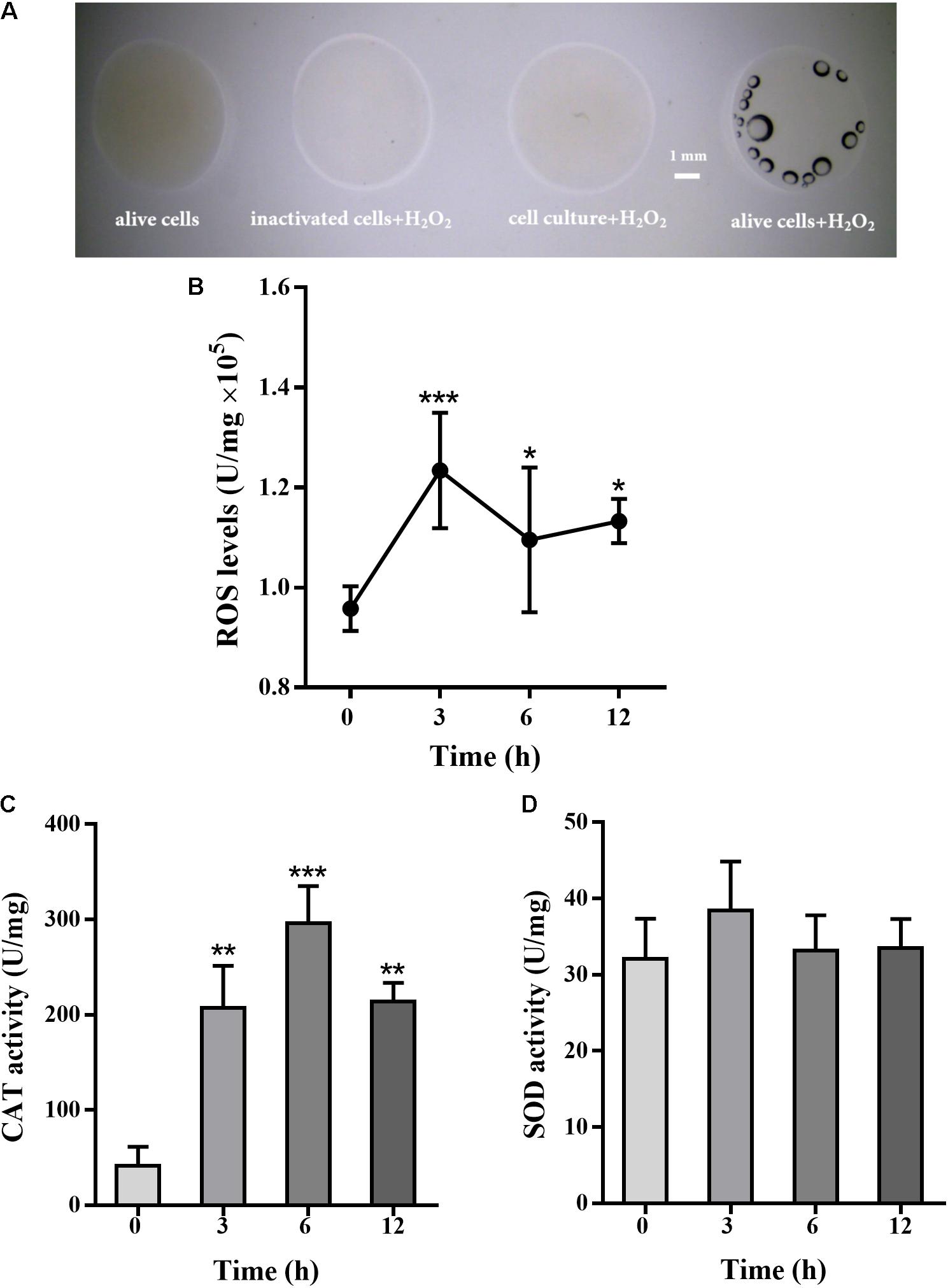

Pseudomonas putida MnB1 is a strict aerobe and possesses CAT. The activity of CAT was detected by oxygen bubble formation upon H2O2 addition. CAT activity was observed in alive P. putida MnB1, while no activity was detected in inactivated cells or culture medium after microbes removing (Figure 4A). Intracellular total ROS levels, when 200 μM H2O2 was added, were increased significantly at 3 h, and maintained until 12 h (Figure 4B). H2O2 exposure for 3, 6, and 12 h significantly increased CAT activity, but failed to change SOD activity (Figures 4C,D).

FIGURE 4. Effect of H2O2 on total cellular ROS levels, CAT and SOD activity in P. putida MnB1. H2O2 (9.7 M) was added to cell suspension, and bubble formation was observed by Dissecting Microscope (scale bar, 1 mm) (A). The volume of four reactions were 20 μL, containing alive microbes (without H2O2), 10 μL cell culture after removing microbes and 10 μL H2O2, 10 μL inactivated bacteria with10 μL H2O2, and 10 μL alive microbes with 10 μL H2O2 (scale bar, 1 mm). Cellular total ROS levels were determined with 200 μM H2O2 incubation for 0, 3, 6, and 12 h (n = 4), respectively (B). Cellular activity of CAT (C) and SOD (D) was analyzed, respectively (n = 4). Total ROS levels, CAT and SOD activity were calibrated to protein concentration in each sample. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. Significance, ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01, and ∗∗∗P < 0.001 vs. control group (0 h incubation).

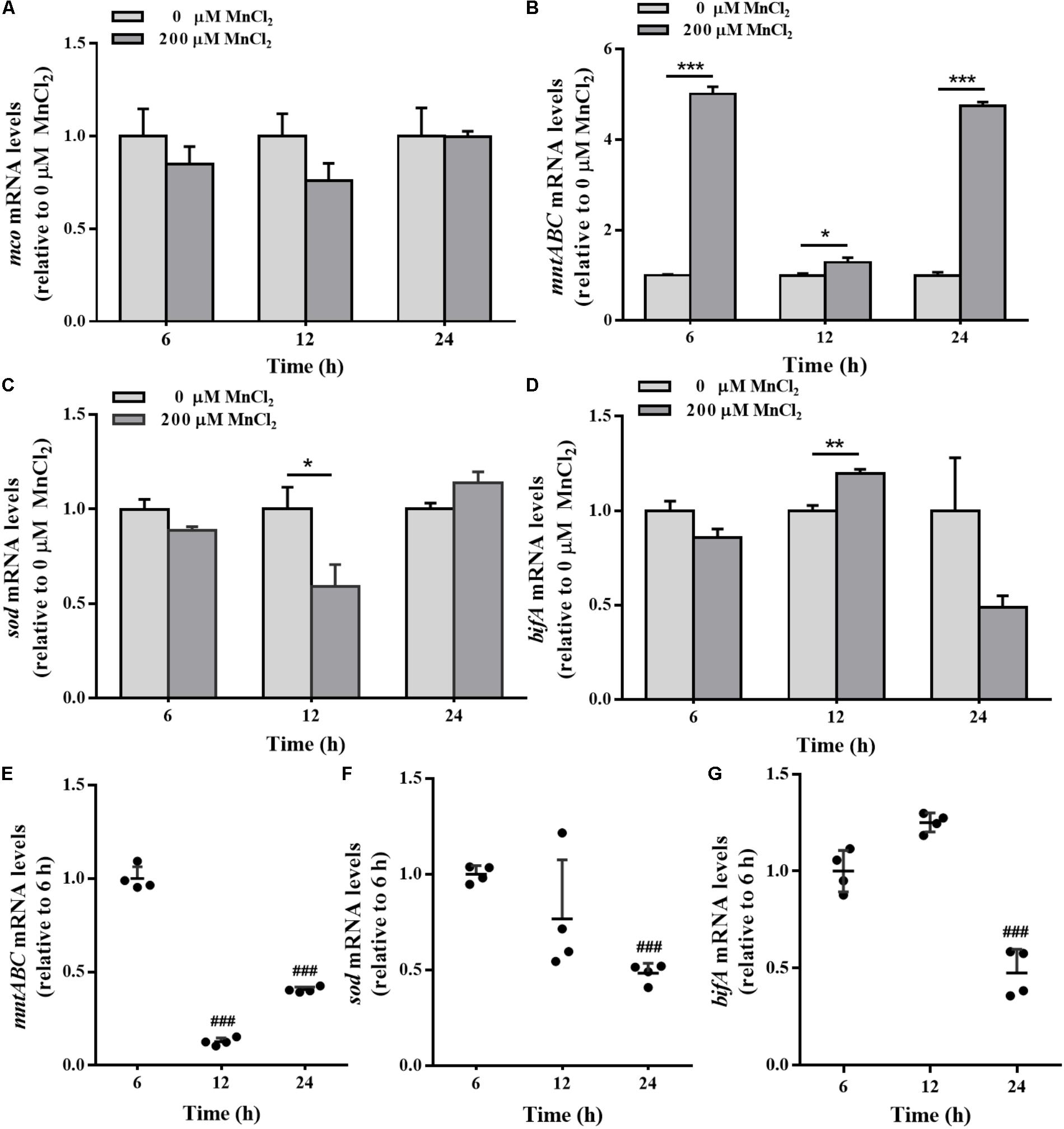

mntABC, sod, and bifA Gene Modulation in Planktonic and Colonized Cells

Sequence similarity in nucleic acid and protein for the amplified products mco, mntABC, sod, and bifA was investigated by NCBI Blast. Most of the PCR products shared at least 98% homology with that of P. putida KT2440 or P. putida GB-1 (Table 2). The homology of each encoded protein predicted by NCBI Blast suggested the existence of conserved motifs.

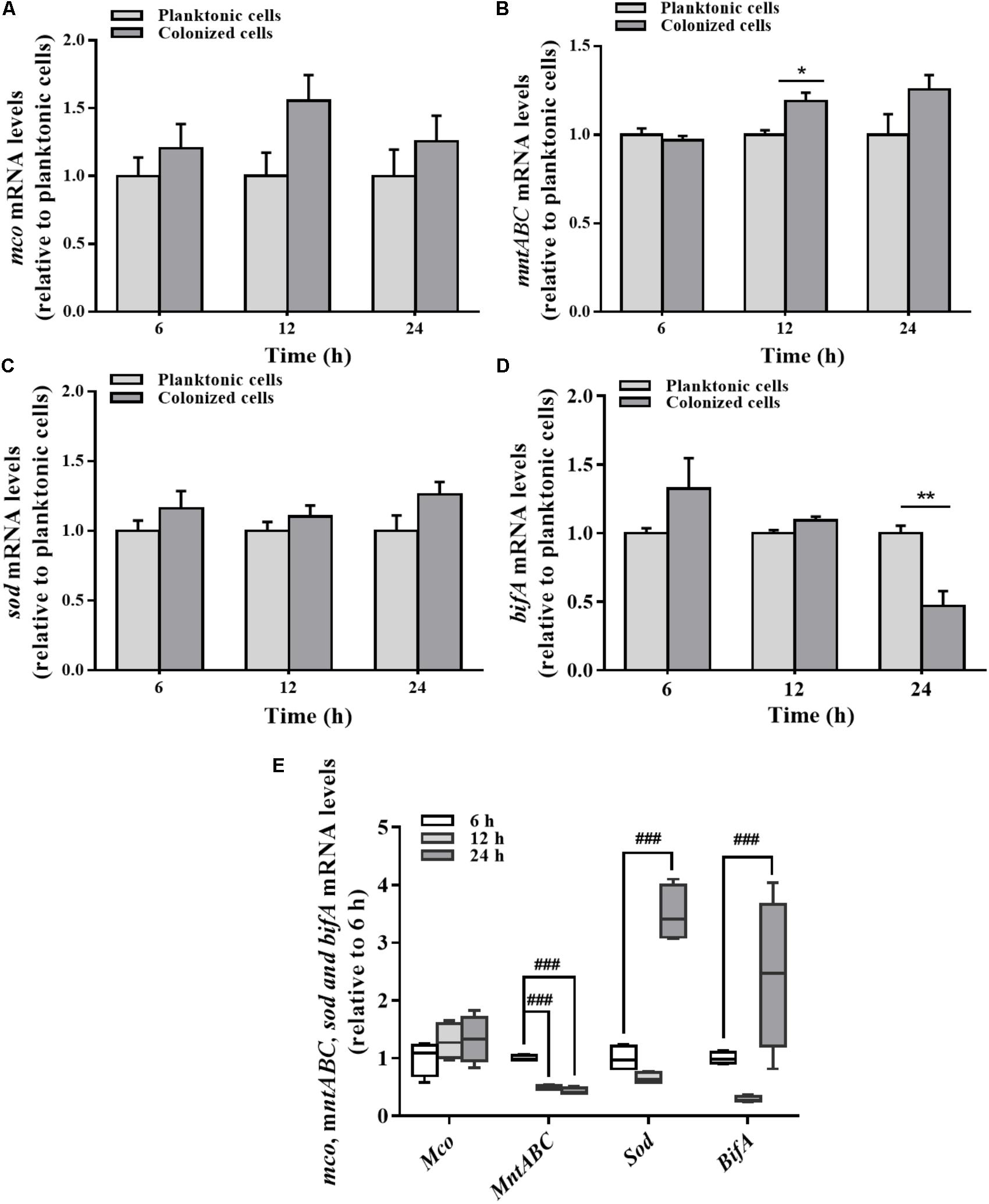

Differences in mRNA expression between planktonic and colonized cells were assayed by qRT-PCR. mco gene expression in the colonized cells was varied slightly at different stages relative to the planktonic cells (Figure 5A). No significant change in mco mRNA levels was detected during the stabilization and maturation of biofilms (Figure 5E). In contrast to the planktonic cells, mntABC mRNA levels were increased in colonized cells at 12 h (Figure 5B). However, mntABC gene expression was markedly decreased during biofilm maturation (Figure 5E).

FIGURE 5. Expression of mco, mntABC, sod, and bifA gene between the planktonic and biofilm lifestyles as well as during biofilm development. mco (A), mntABC (B), sod (C), and bifA (D) mRNA levels in planktonic cells and colonized cells at 6, 12, and 24 h incubation were determined by qRT-PCR, respectively. (E) The cellular mRNA levels of mco, mntABC, sod and bifA during biofilm development in the colonized cells were determined by qRT-PCR. These expression levels were normalized to 16s rRNA (n = 4). Data were expressed as mean ± SEM. Significance, ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01, and ∗∗∗P < 0.001 vs. planktonic cell group. ##P < 0.01 and ###P < 0.001 vs. 6 h-biofilm formation group.

There was no significant difference in the expression of sod gene between planktonic and colonized P. putida MnB1 cells (Figure 5C). But, sod mRNA levels were increased clearly when the biofilm was developed at 24 h (Figure 5E). Compared to planktonic cells, bifA gene expression in colonized cells was declined evidently, especially at 24 h (Figure 5D). bifA mRNA levels during the middle stage were lower than the earlier stage, but increased greatly at 24 h (Figure 5E).

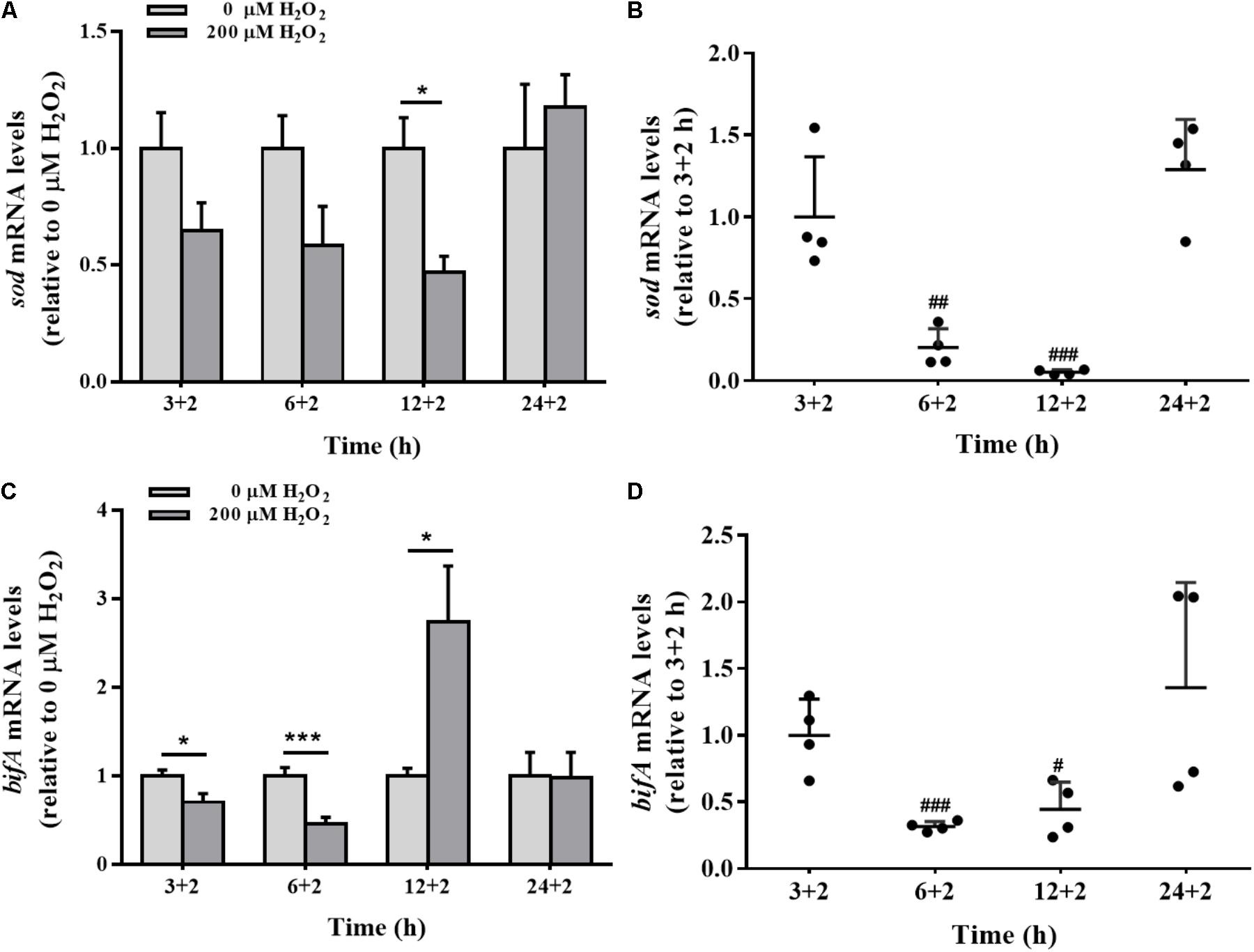

bifA and sod Gene Modulation by Exogenous H2O2

The effects of H2O2 on sod gene expression were time-dependent. Compared to the control group, H2O2 significantly down-regulated the expression of sod gene in biofilm cells at 12 h, with no apparent effect at 3, 6, or 24 h (Figure 6A). H2O2 significantly repressed sod mRNA levels at 6 and 12 h biofilm development, but such a repression was restored when the biofilm was developed to 24 h (Figure 6B).

FIGURE 6. The sod and bifA mRNA levels in biofilm cells as well as during biofilm development with exogenous H2O2. sod (A) and bifA (C) mRNA levels were detected by qRT-PCR analysis in colonized cells incubated with 200 μM H2O2 for 2 h after 3 h, 6, 12, and 24 h cultivation for adhesion, respectively. Relative gene expression levels of sod and bifA were normalized to 16s rRNA (n = 4), respectively. The cellular mRNA levels of sod (B) and bifA (D) during different stages of biofilm formation. Data were expressed as mean ± SEM. Significance, ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01, and ∗∗∗P < 0.001 vs. control group (0 μM H2O2). #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01, and ###P < 0.001 vs. 3 h-biofilm formation group.

The sensitivity of bifA gene expression modulation in biofilm cells under H2O2 exposure was evaluated at 3, 6, and 12 h. H2O2 significantly reduced the expression of bifA gene at 3 and 6 h, which were consistent with H2O2-promoted biofilm formation at the initial stage (Figure 2A). But, the decrease in the bifA mRNA levels was restored at 12 h of biofilm development (Figures 6C,D), being consistent with the CV staining results in which the effect of H2O2 on biofilm formation was nearly disappeared at that stage (Figure 2B). bifA gene expression was dysregulated by H2O2 throughout biofilm development.

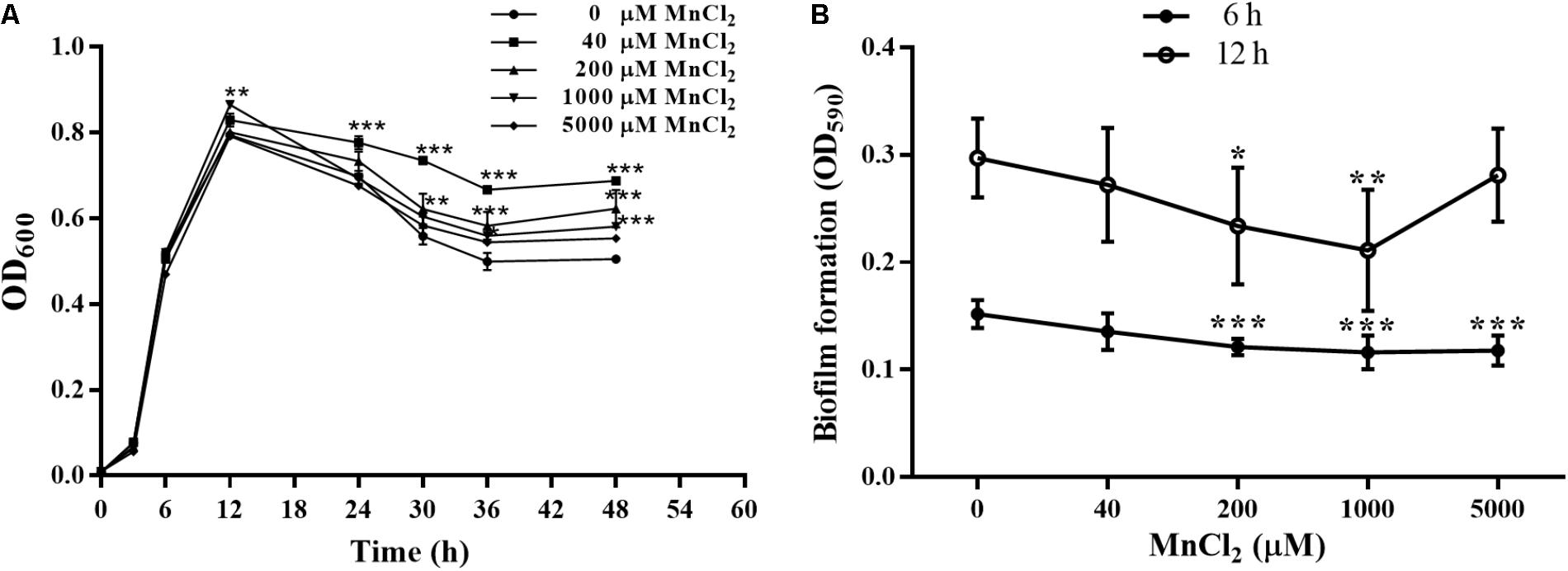

Bacterial Growth and Biofilm Formation With Exogenous Mn2+ Ion Supply

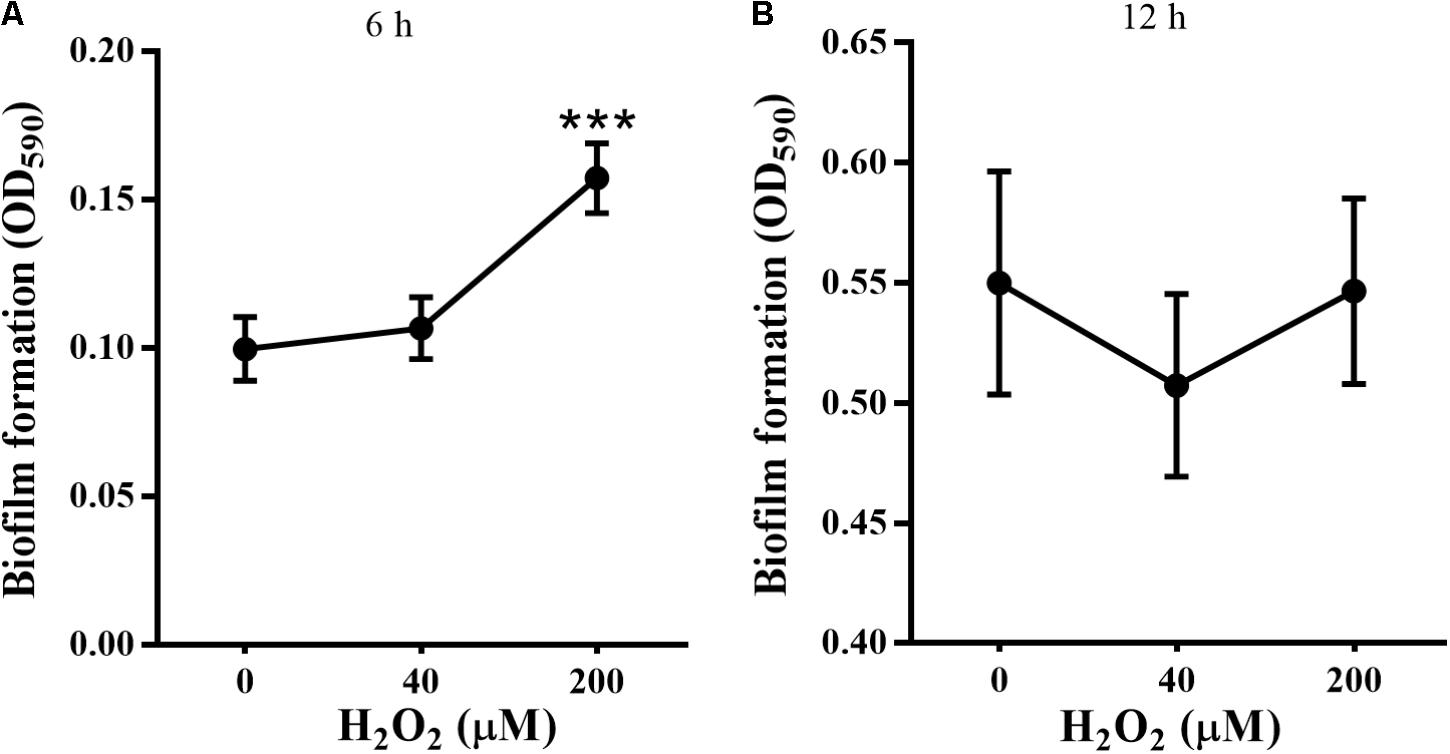

Concentrations of 40, 200, 1000, and 5000 μM MnCl2 were selected as working dosages. As shown in Figure 7A, MnCl2 at all dosages had little effect on the proliferation of P. putida MnB1 within 12 h, but proliferation was promoted after the logarithmic growth period. Interestingly, 200 and 1000 μM MnCl2 were found to reduce biofilm formation significantly at 6 and 12 h (Figure 7B). Similar suppression effect was observed at 6 h with 5000 μM Mn2+ ion supply (Figure 7B).

FIGURE 7. Effect of exogenous Mn2+ ion on the growth and biofilm formation by P. putida MnB1. (A) Microbial growth was detected by measuring the absorbance at 600 nm. P. putida MnB1 was incubated with 0, 40, 200, 1000, and 5000 μM Mn2+, respectively. Biofilm formation by P. putida MnB1 was quantified by CV staining with absorbance at 590 nm. Cells were incubated with Mn2+ (0, 40, 200, 1000, and 5000 μM) for 6 and 12 h (n = 6) (B). Data were expressed as mean ± SEM. Significance, ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01, and ∗∗∗ P < 0.001 vs. control group (0 μM MnCl2).

mco, mntABC, sod, and bifA Gene Modulation by Exogenous Supply of Mn2+ Ion

mco gene expression in the colonized cells was not sensitive to exogenous Mn2+ ion supply (Figure 8A). During biofilm development, the expression levels of mntABC in the colonized cells were remarkably up-regulated by 200 μM Mn2+ compared to planktonic cells (Figure 8B). Down-regulation of sod and up-regulation of bifA mRNA was also induced by 200 μM Mn2+ at 12 h (Figures 8C,D). Biofilm mntABC mRNA levels were decreased in the colonized cells at 24 h relative to 6 and 12 h (Figure 8E), indicating adaption to exogenous Mn2+ overload. Furthermore, sod mRNA levels were down-regulated, exactly similar to H2O2 exposure (Figure 8F). Additionally, bifA expression was increased at 12 h, but declined in biofilms at 24 h (Figure 8G) in the colonized cells exposed to 200 μM Mn2+.

FIGURE 8. The mco, mntABC, sod, and bifA mRNA levels in biofilm cells as well as during biofilm development with exogenous Mn2+. mco (A), mntABC (B), sod (C), and bifA (D) mRNA levels in colonized cells incubated with 200 μM Mn2+ for 2 h after 6, 12, and 24 h cultivation for adhesion, were detected by qRT-PCR, respectively. The cellular mRNA levels of mntABC (E), sod (F), and bifA (G) at different stages of biofilm formation were detected by qRT-PCR, respectively. Relative gene expression levels of mco, mntABC, sod and bifA were normalized to 16s rRNA (n = 4), respectively. Data were expressed as mean ± SEM. Significance, ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01, and ∗∗∗P < 0.001 vs. control group (0 μM MnCl2). ###P < 0.001 vs. 3 h-biofilm formation group.

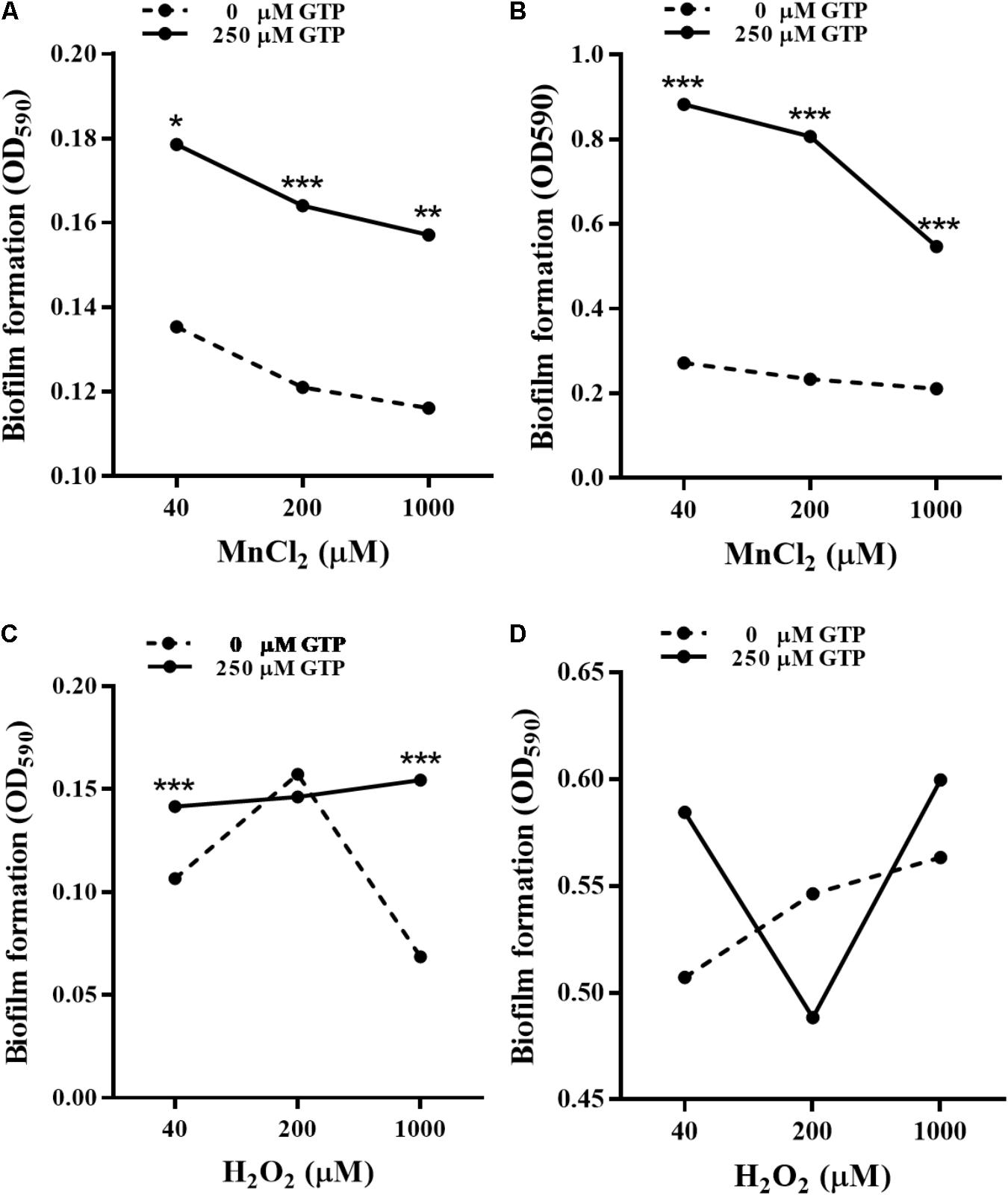

Regulatory Effect of GTP on Biofilm Formation

bifA mRNA levels in P. putida MnB1 were down-regulated by H2O2 at 3 and 6 h (Figure 6C), while the opposite modulation was observed with MnCl2 incubation at 12 h (Figure 8D). GTP is an effective inhibitor of BifA that partially blocks BifA-mediated degradation of c-di-GMP, promoting biofilm formation (Barraud et al., 2009). At different Mn2+ concentrations, pre-incubation with 200 μM GTP significantly promoted biofilm formation at 6 h (Figure 9A), this promotion was further strengthened to nearly 3–5 fold at 12 h (Figure 9B). GTP also increased biofilm formation at 6 h with 40 and 1000 μM H2O2 (Figure 9C). But, the amplification effect of GTP on biofilm formation did not show demonstrable at 12 h with H2O2 exposure at 3 dosages (Figure 9D).

FIGURE 9. Effect of GTP on biofilm formation by P. putida MnB1. Microbes were incubated with Mn2+ at 40, 200, and 1000 μM for 6 h (A) and 12 h (B) in the presence or absence of 250 μM GTP (n = 6), respectively. Microbes were incubated with H2O2 at 40, 200, and 1000 μM for 6 h (C) and 12 h (D) in the presence or absence of 250 μM GTP (n = 6), respectively. Biofilm formation of P. putida MnB1 was quantified by CV staining with absorbance at 590 nm. Data were expressed as mean ± SEM. Significance, ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01, and ∗∗∗P < 0.001 vs. control group (0 μM GTP).

Discussion

In general, activation of anti-oxidative system (Kubota et al., 2008) and biofilm formation (Falkowski et al., 2008) are strategies utilized by pathogenic microorganisms to achieve stress tolerance. However, the mechanisms by which environmental microbes adapt to varying environments are not fully understood. In this study, the involvement of anti-oxidative system and c-di-GMP signaling in response to H2O2 and MnCl2 by P. putida MnB1 were investigated to elucidate the microbial adaptive mechanisms within natural environments.

Modulation of Anti-oxidative System in Response to Exogenous H2O2

In this study, no cytotoxic effect of H2O2 (40–1000 μM) on P. putida MnB1 proliferation was observed. However, at 1000 μM H2O2, proliferation was retarded in the first 24 h (Figure 1A). Rapid recovery from high H2O2 levels suggests an effective defense mechanism against exogenous H2O2. P. putida MnB1 could quickly degrade H2O2 and produce O2 bubbles (Figure 4A), suggesting H2O2 decomposition (Figures 1B,C) by CAT activity (An et al., 2011; Chiang et al., 2011). However, cellular oxidative stress was maintained until 12 h even though the H2O2 had been scavenged (Figures 1B,C), with increased ROS levels (Figure 4B). Meanwhile, CAT activity increased significantly until 12 h (Figure 4C) induced by H2O2 exposure for decomposition. This decomposition improves cell viability by reducing oxidative damage to DNA and RNA in Bifidobacterium longum (Zuo et al., 2014) and in several UV-sensitive bacteria, during intracellular oxidative stress (Santos et al., 2012). During this procedure, sod over-expression synergistically accelerates the decomposition of exogenous H2O2 catalyzed by CAT. Sod-regulated anti-oxidative mechanisms are commonly adaptive processes for microbial protection (Green and Paget, 2004; Imlay, 2013). Intracellular ROS is produced not only physiologically, but also in response to environmental stimuli, including lack of nutrients, heavy metals contamination and ultraviolet light (Cabiscol et al., 2000; Green and Paget, 2004; Matallana-Surget et al., 2009; Chattopadhyay et al., 2011; Murata et al., 2011; Chen et al., 2013; Imlay, 2013). Herein, no significant SOD activation (Figure 4D) or sod up-regulation was observed during biofilm formation of P. putida MnB1 with H2O2 exposure (Figure 6A). In the presence of H2O2, sod up-regulation relieves oxidative stress and allows microbial adaptation to environmental change (Green and Paget, 2004; Imlay, 2013). Therefore, the function of SOD involved anti-oxidative system in the resistance to H2O2 in P. putida MnB1 is not observably crucial.

Biofilm Formation in Response to Exogenous H2O2

In the present study, bifA gene expression was altered significantly when P. putida MnB1 cells were transformed from a planktonic to an adhesive lifestyle, as well as during the development of biofilms (Figure 5D). c-di-GMP specific PDEs modulate biofilm formation by decreasing cellular c-di-GMP levels as well as the sensitivity of microbes to environmental stresses (Osterberg et al., 2013; Fang et al., 2014; Aragon et al., 2015). It has been well disclosed that biofilm cells are more resistant to oxidative stress than planktonic cells in phytopathogenic microbes (Haque et al., 2017) and in animal pathogens (Hisert et al., 2005; Huang et al., 2013; Chua et al., 2016; Echeverz et al., 2017), which favors adaption and survival (Hisert et al., 2005; Dean et al., 2011; Wang et al., 2011; DePas et al., 2013; Chua et al., 2016). In this study, bifA gene expression (Figures 6C,D) and associated biofilm development (Figures 2, 3) in P. putida MnB1 were clearly modulated by H2O2 exposure. Therefore, bifA-involved biofilm formation may be a defensive strategy utilized by P. putida MnB1 to survive H2O2 exposure-induced oxidative stress. Furthermore, the initiation of biofilm formation by P. putida MnB1 was more susceptible to H2O2 exposure than the mature biofilm (Figures 6C,D), being consistent with results obtained with P. putida KT2440 in response to ZnO nanoparticles (Ouyang et al., 2017). c-di-GMP-mediated adsorption is normally a key process for microbial leaching, in which biofilm formation is a defensive strategy against exogenous H2O2. 50 μM H2O2 promotes the adsorption of Thiobacillus ferrooxidans onto pyrite surfaces, enhancing the microbial oxidation of pyrite (Bellenberg et al., 2014). A significant increase in c-di-GMP content in colonized but not suspended cells has been reported in T. ferrooxidans (Ruiz et al., 2012).

It has been indicated that bacteria develop nanowires to facilitate efficient electron transport within the biofilm of microbial fuel cells (Reguera et al., 2005; Gorby et al., 2006) and clinical pathogens (Wanger et al., 2013). The nanowires formed between cells and the interface between cells and solid-phase, may contribute to biofilm development (Reguera et al., 2006, 2007), biofilm stabilization (Reguera et al., 2005; Gorby et al., 2006), and pathogenicity (Wanger et al., 2013). Acyl-homoserine lactone is a second messenger to regulate biofilm formation and triggers nanowires occurrence in Aeromonas hydrophila (Castro et al., 2014). Nanowires are proved to increase biofilm stabilization and decrease sensitivity to antibiotic treatment (Wanger et al., 2013). The nanowires observed in this study may exhibit the role of biofilm formation in response of P. putida MnB1 to H2O2 exposure (Figure 3D). This is an interesting observation that provides a foundation for further investigation of BifA-mediated biofilm development. Therefore, biofilm formation by P. putida MnB1 may defend against unfavorable environmental condition and it may be more sensitive than the intracellular anti-oxidative system.

Mn2+ Ion Functions to Modulate Biofilm Formation

Effective acquisition of Mn2+ is normally involved in microbial resistance to oxidative stress and in bacterial pathogenesis (Papp-Wallace and Maguire, 2006; Coady et al., 2015). In this study, colonized cells exhibited an up-regulation of mntABC at mRNA level, suggesting the increased capacity for Mn2+ uptake (Figure 5B). Mn2+ overload increased mntABC gene expression as the biofilm was developed, demonstrating the adaptation potential (Figure 8B). Pathogens generally produce ROS for protection from the host immune response by increasing expression of Mn transporter proteins (Kehl-Fie et al., 2013; Park et al., 2017). Mutation or down-regulation of Mn transporters (MntABC, MntC, and MntH) significantly interferes with Mn2+ acquisition, increasing susceptibility to oxidative damage in Streptococcus (Wang et al., 2014; Chen et al., 2017), Staphylococcus aureus (Horsburgh et al., 2002; Coady et al., 2015), and Neisseria gonorrhoeae (Tseng et al., 2001; Kehl-Fie et al., 2013). SOD is an important oxygen free radical scavenger, and possibly use Mn2+ as a cofactor to influence disease progression (Miao and St Clair, 2009). MCO is the major Mn oxidation enzyme to supply energy for Mn-oxidizing microbes (Brouwers et al., 1999, 2000; Francis and Tebo, 2001; Dick et al., 2008). In the present study, mco levels were barely changed with exogenous Mn2+ (Figure 8A) and H2O2 (data not shown), indicating that Mn2+ ion supply did not remarkably affect Mn2+ oxidation. Similar to H2O2, exogenous Mn2+ ion decreased the expressions of sod significantly (Figure 8C), but negatively related to biofilm formation (Figure 7B). Mn2+ ion function to scavenge ROS as a cofactor for SOD, the effective acquisition of which is found to be closely associated with the repair of oxidative damage (DePas et al., 2013), thus ensuring the effective growth of bacteria after phagocytosis (Tseng et al., 2001; Horsburgh et al., 2002; Kehl-Fie et al., 2013; Wang et al., 2014; Coady et al., 2015; Chen et al., 2017).

As a type of trace nutrient, Mn2+ ion supply is an important factor affecting the biofilm formation (Shrout et al., 2006; Amaya-Gomez et al., 2015). In one respect, Mn2+ ion supply can promote the biofilm formation, which is restored by Mn2+ depletion in Streptococcus mutans, P. aeruginosa, and Agrobacterium tumefaciens (Shrout et al., 2006; Amaya-Gomez et al., 2015). In contrast, Mn2+ ion can inhibit biofilm formation by some microbes (e.g., Yersinia pestis), possibly through the activation of c-di-GMP specific PDE HmsP, being strictly dependent on Mn2+ (Bobrov et al., 2005). Suppression of sod demonstrates a ROS scavenger of Mn2+, which serves as a substitution for the protective role of biofilm formation. Consistently, bifA up-regulation was accompanied by biofilm suppression in P. putida MnB1 (Figures 6, 8). Mutation of an oxidative stress regulatory protein, OxyR, makes cells more sensitive to H2O2, resulting in defective biofilm maturation in Xylella fastidiosa. Thus, ROS may be a potential environmental stimulus for biofilm formation during host invasion by the bacterial phytopathogen, Xylella fastidiosa (Wang et al., 2017), further suggesting a potential relationship between anti-oxidative system and biofilm formation. Therefore, biofilm formation may be a universal mechanism for adaptation to environmental changes, and Mn2+ ion may decrease biofilm formation through regulation of bifA in P. putida MnB1.

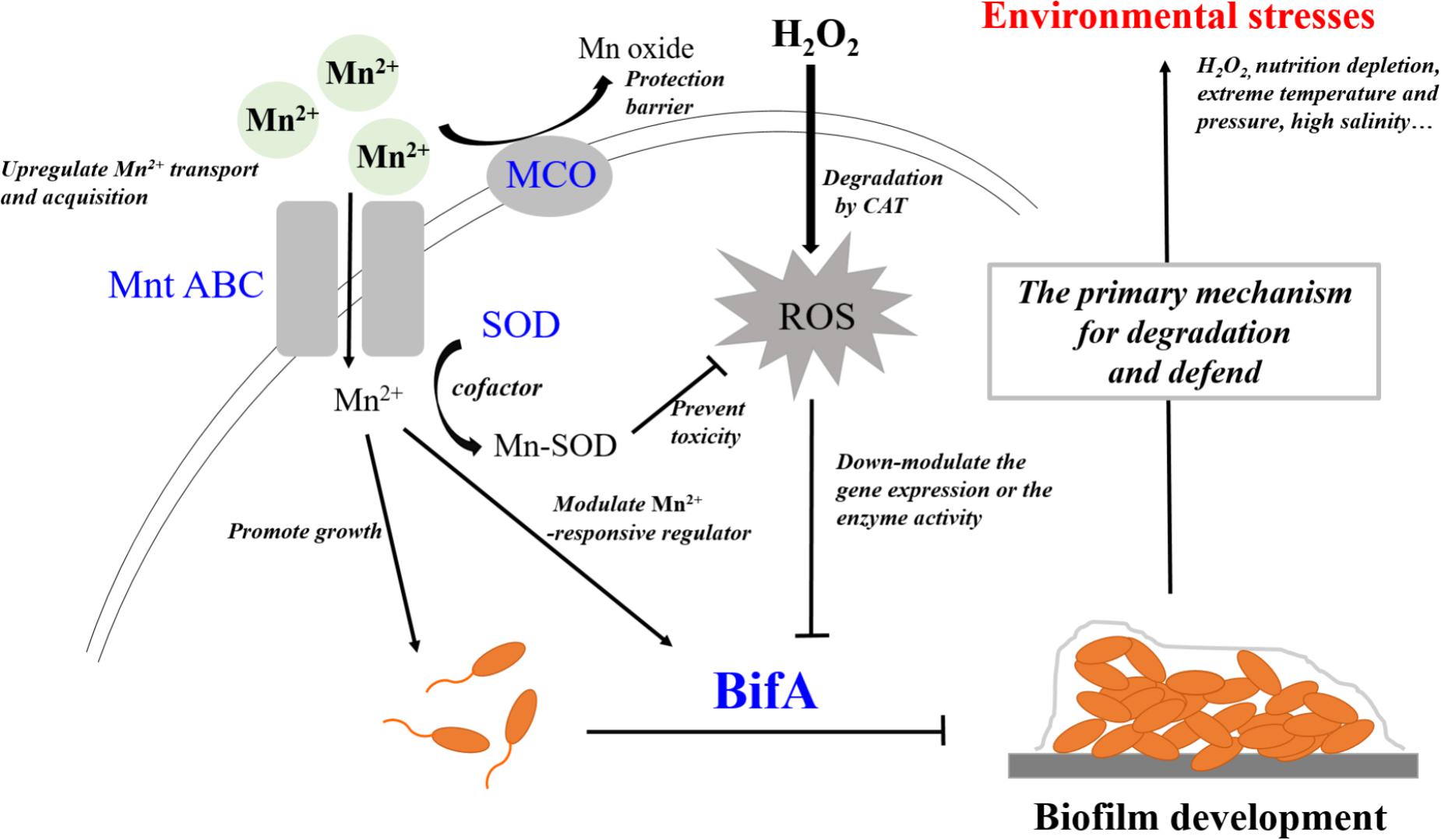

BifA-Involved Biofilm Formation: A Sensitive Strategy for Protection

Mn2+ and H2O2 can be considered a trace nutrient supply and an environmental stress for P. putida MnB1, respectively. A close relationship was observed between regulation by Mn2+ and H2O2 and the formation and development of biofilms (Figures 2, 3, 7). Moreover, GTP reversed the suppressive effect of Mn2+ on biofilm formation and greatly increased biofilm development for P. putida MnB1 (Figures 9A,B). GTP also accelerated biofilm formation at the initiation stage following the addition of H2O2 (Figures 9C,D). A bifA ortholog was amplified from the P. putida MnB1 genome, sharing 89% homology with the c-di-GMP PDE of P. putida GB1. Analysis with the alignment search algorithm BLASTX showed that the P. putida MnB1 BifA ortholog contain an EAL motif, which is crucial for c-di-GMP specific PDE activity. DGC synthesizes c-di-GMP in a GTP-dependent manner (Chen and Schaap, 2012) and c-di-GMP specific PDE is highly responsive to intracellular GTP availability (Christen et al., 2005; Barraud et al., 2009; An et al., 2010; Purcell et al., 2017). In response to diverse stresses on P. aeruginosa, c-di-GMP specific PDE mediates biofilm formation as well as the production and secretion of virulence factors that play a vital role in escape from host defense. In P. aeruginosa, biofilm dispersal and intracellular c-di-GMP specific PDE activity are significantly abrogated in the presence of GTP (Barraud et al., 2009). The gene rbdA encodes a bifunctional protein containing highly conserved DGC (GGDEF) and c-di-GMP specific PDE (EAL) motifs. GTP increases the c-di-GMP specific PDE activity of RbdA by allosterically modulating the GGDEF domain, promoting biofilm dispersal and production of virulence factors (rhamnolipids and exopolysaccharides) (An et al., 2010). Consistent with the results from P. aeruginosa (Barraud et al., 2009), we also manifested that GTP improved biofilm formation of P. putida MnB1, suggesting a key role for BifA in the formation of P. putida MnB1 biofilms as a sensitive defense to environmental stresses (Figure 10).

FIGURE 10. BifA regulated-biofilm formation is a primary mechanism to defend exogenous H2O2 exposure and closely correlates to cellular oxidative stress. Mn2+ ion and H2O2 represent 2 types of environmental factors, a trace nutrient substrate and an oxidative stress, respectively. Four genes that encode MCO, Mn2+ transporter, SOD and BifA were assayed for their expression during bacterial growth following exposure to the two environmental factors Mn2+ ion and H2O2 on the growth, Mn2+ acquisition, anti-oxidative system and biofilm formation in P. putida MnB1. Exogenous Mn2+ promoted Mn2+ uptake and acquisition. An increase in intracellular Mn2+ may act as nutrient substrate promoting microbial growth. Alternatively, Mn2+ may function as a cofactor for important enzymes, such as SOD, which scavenges ROS. Mn oxide, catalyzed by MCO is a barrier to protect from invasion, heavy metal and oxidative damage. Mn2+ may target Mn2+-responsive regulators to inhibit biofilm formation by BifA up-regulation. Decrements in intracellular anti-oxidative system and the inhibition of biofilm formation suggests that Mn2+ favors the microbial growth but suppresses biofilm development. Exogenous H2O2 triggers intracellular ROS over-production, but does not significantly affect the proliferation of P. putida MnB1. Bio-degradation of exogenous H2O2 and quick recovery of proliferative capacity at high H2O2 levels are due to CAT activity. In contrast to the activation of anti-oxidative system, promotion of the biofilms by down-regulation of BifA gene or the blockade of BifA activity suggests that biofilm formation may be a primary mechanism by which P. putida MnB1 defends unfavorable environmental factors. Therefore, BifA-mediated biofilm formation may be more sensitive than anti-oxidative system in response to Mn2+ ion and H2O2 in P. putida MnB1. The sensitivity of BifA-mediated biofilm formation may highlight its role in the adaption of microbes to environment stress. MCO, Manganese oxidase; MntABC, ABC-Type manganese transporter; SOD, Superoxide dismutase; CAT, Catalase; PDE, Phosphodiesterase; ROS, Reactive oxygen species.

Deletion of the yjcCT gene of Klebsiella pneumoniae CG43 (a c-di-GMP specific PDE), promotes sensitivity to H2O2 treatment, with the reduction of survival rate. At the same time, ROS overproduction generally accompanies biofilm development (Huang et al., 2013). For the pathogenic bacteria P. aeruginosa, exogenous H2O2 promotes biofilm formation (Chua et al., 2016). Furthermore, mutation in WspF is induced by H2O2, with high intracellular c-di-GMP concentration and biofilm development (Chua et al., 2016). cdgR encodes a c-di-GMP specific PDE in Salmonella enteric var. Typhimurium, interference of which decreases resistance to H2O2 (Hisert et al., 2005). Therefore, bifA can respond to environmental factors by regulating biofilm formation, which is more sensitive than the intracellular anti-oxidative system in P. putida MnB1.

Conclusion

In this study, the effects of H2O2 and Mn2+ ion on P. putida MnB1 growth, Mn2+ ion acquisition, anti-oxidative system, and biofilm formation were investigated. Exogenous Mn2+ ion supply promoted the growth and Mn2+ uptake capacity of P. putida MnB1, but suppressed biofilm formation. Exogenous H2O2 was bio-degraded quickly in the presence of P. putida MnB1, with maintained cellular oxidative stress after H2O2 depletion. No significant SOD activation or sod gene up-regulation was detected in P. putida MnB1with H2O2 exposure. In contrast, bifA gene expression and subsequent biofilm formation were significantly modulated by Mn2+ ion and H2O2. The correlation between bifA-mediated biofilm formation and effect of Mn2+ ion and H2O2 was further manifested by blocking BifA activity in the presence of GTP. Sensitivity differences between intracellular anti-oxidative system and biofilm formation suggests that BifA-mediated biofilm formation may be a primary defense mechanism by P. putida MnB1 in response to environmental factors. These findings highlight the role of biofilm development in adaption of microbes to environment stresses.

Author Contributions

DZ conceived and designed the study. YZ conducted the experiments and prepared the manuscript. YL, HL, XZ, and KJ conducted the experiments. JL, LW, and RW analyzed and interpreted the data. DZ and XL wrote and revised the manuscript.

Funding

This work was financially supported by grants from the National Basic Research Program of China (No. 2014CB846004) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 41425009).

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Footnotes

References

Amaya-Gomez, C. V., Hirsch, A. M., and Soto, M. J. (2015). Biofilm formation assessment in Sinorhizobium meliloti reveals interlinked control with surface motility. BMC Microbiol. 15:58. doi: 10.1186/s12866-015-0390-z

An, H. R., Zhai, Z. Y., Yin, S., Luo, Y. B., Han, B. Z., and Hao, Y. L. (2011). Coexpression of the superoxide dismutase and the catalase provides remarkable oxidative stress resistance in Lactobacillus rhamnosus. J. Agric. Food Chem. 59, 3851–3856. doi: 10.1021/jf200251k

An, S. W., Wu, J. E., and Zhang, L. H. (2010). Modulation of Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm dispersal by a cyclic-Di-GMP phosphodiesterase with a putative hypoxia-sensing domain. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 76, 8160–8173. doi: 10.1128/Aem.01233-10

Apel, K., and Hirt, H. (2004). Reactive oxygen species: metabolism, oxidative stress, and signal transduction. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 55, 373–399. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.55.031903.141701

Aragon, I. M., Perez-Mendoza, D., Gallegos, M. T., and Ramos, C. (2015). The c-di-GMP phosphodiesterase BifA is involved in the virulence of bacteria from the Pseudomonas syringae complex. Mol. Plant Pathol. 16, 604–615. doi: 10.1111/mpp.12218

Banh, A., Chavez, V., Doi, J., Nguyen, A., Hernandez, S., Ha, V., et al. (2013). Manganese (Mn) oxidation increases intracellular Mn in Pseudomonas putida GB-1. PLoS One 8:e77835. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0077835

Barraud, N., Schleheck, D., Klebensberger, J., Webb, J. S., Hassett, D. J., Rice, S. A., et al. (2009). Nitric oxide signaling in Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms mediates phosphodiesterase activity, decreased cyclic di-GMP levels, and enhanced dispersal. J. Bacteriol. 191, 7333–7342. doi: 10.1128/JB.00975-09

Bellenberg, S., Diaz, M., Noel, N., Sand, W., Poetsch, A., Guiliani, N., et al. (2014). Biofilm formation, communication and interactions of leaching bacteria during colonization of pyrite and sulfur surfaces. Res. Microbiol. 165, 773–781. doi: 10.1016/j.resmic.2014.08.006

Bobrov, A. G., Kirillina, O., and Perry, R. D. (2005). The phosphodiesterase activity of the HmsP EAL domain is required for negative regulation of biofilm formation in Yersinia pestis. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 247, 123–130. doi: 10.1016/j.femsle.2005.04.036

Boogerd, F. C., and Devrind, J. P. M. (1987). Manganese oxidation by Leptothrix discophora. J. Bacteriol. 169, 489–494. doi: 10.1128/jb.169.2.489-494.1987

Borch, T., Kretzschmar, R., Kappler, A., Cappellen, P. V., Ginder-Vogel, M., Voegelin, A., et al. (2010). Biogeochemical redox processes and their impact on contaminant dynamics. Environ. Sci. Technol. 44, 15–23. doi: 10.1021/es9026248

Borda, M. J., Elsetinow, A. R., Schoonen, M. A., and Strongin, D. R. (2001). Pyrite-induced hydrogen peroxide formation as a driving force in the evolution of photosynthetic organisms on an early earth. Astrobiology 1, 283–288. doi: 10.1089/15311070152757474

Borlee, B. R., Goldman, A. D., Murakami, K., Samudrala, R., Wozniak, D. J., and Parsek, M. R. (2010). Pseudomonas aeruginosa uses a cyclic-di-GMP-regulated adhesin to reinforce the biofilm extracellular matrix. Mol. Microbiol. 75, 827–842. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2009.06991.x

Brouwers, G. J., de Vrind, J. P. M., Corstjens, P. L. A. M., Cornelis, P., Baysse, C., and DeJong, E. W. D. V. (1999). cumA, a gene encoding a multicopper oxidase, is involved in Mn2+ oxidation in Pseudomonas putida GB-1. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65, 1762–1768.

Brouwers, G. J., Vijgenboom, E., Corstjens, P. L. A. M., De Vrind, J. P. M., and de Vrind-de Jong, E. W. (2000). Bacterial Mn2+ oxidizing systems and multicopper oxidases: an overview of mechanisms and functions. Geomicrobiol. J. 17, 1–24. doi: 10.1080/014904500270459

Cabiscol, E., Tamarit, J., and Ros, J. (2000). Oxidative stress in bacteria and protein damage by reactive oxygen species. Int. Microbiol. 3, 3–8.

Cailliatte, R., Schikora, A., Briat, J. F., Mari, S., and Curie, C. (2010). High-affinity manganese uptake by the metal transporter NRAMP1 is essential for arabidopsis growth in low manganese conditions. Plant Cell 22, 904–917. doi: 10.1105/tpc.109.073023

Calabrese, V., Cornelius, C., Cuzzocrea, S., Iavicoli, I., Rizzarelli, E., and Calabrese, E. J. (2011). Hormesis, cellular stress response and vitagenes as critical determinants in aging and longevity. Mol. Aspects Med. 32, 279–304. doi: 10.1016/j.mam.2011.10.007

Cap, M., Vachova, L., and Palkova, Z. (2012). Reactive oxygen species in the signaling and adaptation of multicellular microbial communities. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2012:976753. doi: 10.1155/2012/976753

Caspi, R., Tebo, B. M., and Haygood, M. G. (1998). c-type cytochromes and manganese oxidation in Pseudomonas putida MnB1. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 64, 3549–3555.

Castro, L., Vera, M., Munoz, J. A., Blazquez, M. L., Gonzalez, F., Sand, W., et al. (2014). Aeromonas hydrophila produces conductive nanowires. Res Microbiol. 165, 794–802. doi: 10.1016/j.resmic.2014.09.005

Chattopadhyay, M. K., Raghu, G., Sharma, Y. V., Biju, A. R., Rajasekharan, M. V., and Shivaji, S. (2011). Increase in oxidative stress at low temperature in an antarctic bacterium. Curr. Microbiol. 62, 544–546. doi: 10.1007/s00284-010-9742-y

Chavarria, M., Nikel, P. I., Perez-Pantoja, D., and de Lorenzo, V. (2013). The Entner-Doudoroff pathway empowers Pseudomonas putida KT2440 with a high tolerance to oxidative stress. Environ. Microbiol. 15, 1772–1785. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.12069

Chen, J., Shen, J., Solem, C., and Jensen, P. R. (2013). Oxidative stress at high temperatures in Lactococcus lactis due to an insufficient supply of Riboflavin. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 79, 6140–6147. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01953-13

Chen, Z., Wang, X., Yang, F., Hu, Q., Tong, H., and Dong, X. (2017). Molecular insights into hydrogen peroxide-sensing mechanism of the metalloregulator MntR in controlling bacterial resistance to oxidative stresses. J. Biol. Chem. 292, 5519–5531. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M116.764126

Chen, Z. H., and Schaap, P. (2012). The prokaryote messenger c-di-GMP triggers stalk cell differentiation in Dictyostelium. Nature 488, 680–683. doi: 10.1038/nature11313

Chiang, S. M., Dong, T., Edge, T. A., and Schellhorn, H. E. (2011). Phenotypic diversity caused by differential RpoS activity among environmental Escherichia coli isolates. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 77, 7915–7923. doi: 10.1128/Aem.05274-11

Christen, M., Christen, B., Folcher, M., Schauerte, A., and Jenal, U. (2005). Identification and characterization of a cyclic di-GMP-specific phosphodiesterase and its allosteric control by GTP. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 30829–30837. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M504429200

Chua, S. L., Ding, Y., Liu, Y., Cai, Z., Zhou, J., Swarup, S., et al. (2016). Reactive oxygen species drive evolution of pro-biofilm variants in pathogens by modulating cyclic-di-GMP levels. Open Biol. 6:160162. doi: 10.1098/rsob.160162

Coady, A., Xu, M., Phung, Q., Cheung, T. K., Bakalarski, C., Alexander, M. K., et al. (2015). The Staphylococcus aureus ABC-type manganese transporter MntABC is critical for reinitiation of bacterial replication following exposure to phagocytic oxidative burst. PLoS One 10:e0138350. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0138350

Colomer-Winter, C., Gaca, A. O., and Lemos, J. A. (2017). Association of metal homeostasis and (p) ppGpp regulation in the pathophysiology of Enterococcus faecalis. Infect. Immun. 85:e00260-17. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00260-17

Cooper, W. J., Zika, R. G., Petasne, R. G., and Plane, J. M. C. (1988). Photochemical formation of H2O2 in natural-waters exposed to sunlight. Environ. Sci. Technol. 22, 1156–1160. doi: 10.1021/es00175a004

Courville, P., Chaloupka, R., and Cellier, M. F. M. (2006). Recent progress in structure-function analyses of Nramp proton-dependent metal-ion transporters. Biochem. Cell Biol. 84, 960–978. doi: 10.1139/O06-193

Dean, S. N., Bishop, B. M., and van Hoek, M. L. (2011). Susceptibility of Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm to alpha-helical peptides: D-enantiomer of LL-37. Front. Microbiol. 2:128. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2011.00128

DePas, W. H., Hufnagel, D. A., Lee, J. S., Blanco, L. P., Bernstein, H. C., Fisher, S. T., et al. (2013). Iron induces bimodal population development by Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110, 2629–2634. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1218703110

Dick, G. J., Podell, S., Johnson, H. A., Rivera-Espinoza, Y., Bernier-Latmani, R., McCarthy, J. K., et al. (2008). Genomic insights into Mn(II) oxidation by the marine alphaproteobacterium Aurantimonas sp. strain SI85-9A1. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 74, 2646–2658. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01656-07

Echeverz, M., Garcia, B., Sabalza, A., Valle, J., Gabaldon, T., Solano, C., et al. (2017). Lack of the PGA exopolysaccharide in Salmonella as an adaptive trait for survival in the host. PLoS Genet. 13:e1006816. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1006816

Falkowski, P. G., Fenchel, T., and Delong, E. F. (2008). The microbial engines that drive Earth’s biogeochemical cycles. Science 320, 1034–1039. doi: 10.1126/science.1153213

Fang, N., Qu, S., Yang, H. Y., Fang, H. H., Liu, L., Zhang, Y. Q., et al. (2014). HmsB enhances biofilm formation in Yersinia pestis. Front. Microbiol. 5:685. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2014.00685

Fernandez, M., Niqui-Arroyo, J. L., Conde, S., Ramos, J. L., and Duque, E. (2012). Enhanced tolerance to naphthalene and enhanced rhizoremediation performance for Pseudomonas putida KT2440 via the NAH7 catabolic plasmid. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 78, 5104–5110. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00619-12

Forrez, I., Carballa, M., Fink, G., Wick, A., Hennebel, T., Vanhaecke, L., et al. (2011). Biogenic metals for the oxidative and reductive removal of pharmaceuticals, biocides and iodinated contrast media in a polishing membrane bioreactor. Water Res. 45, 1763–1773. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2010.11.031

Francis, C. A., and Tebo, B. M. (2001). cumA multicopper oxidase genes from diverse Mn(II)-oxidizing and non-Mn(II)-oxidizing Pseudomonas strains. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67, 4272–4278. doi: 10.1128/Aem.67.9.4272-4278.2001

Gjermansen, M., Ragas, P., Sternberg, C., Molin, S., and Tolker-Nielsen, T. (2005). Characterization of starvation-induced dispersion in Pseudomonas putida biofilms. Environ. Microbiol. 7, 894–906. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2005.00775.x

Gjermansen, M., Ragas, P., and Tolker-Nielsen, T. (2006). Proteins with GGDEF and EAL domains regulate Pseudomonas putida biofilm formation and dispersal. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 265, 215–224. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2006.00493.x

Gorby, Y. A., Yanina, S., McLean, J. S., Rosso, K. M., Moyles, D., Dohnalkova, A., et al. (2006). Electrically conductive bacterial nanowires produced by Shewanella oneidensis strain MR-1 and other microorganisms. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 11358–11363. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0604517103

Green, J., and Paget, M. S. (2004). Bacterial redox sensors. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2, 954–966. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1022

Gunz, D. H., and Hoffmann, M. R. (1990). Atmospheric chemistry of peroxides—a review. Atmos. Environ. A Gen. Top. 24, 1601–1633. doi: 10.1016/0960-1686(90)90496-A

Hakkinen, P. J., Anesio, A. M., and Graneli, W. (2004). Hydrogen peroxide distribution, production, and decay in boreal lakes. Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 61, 1520–1527. doi: 10.1139/F04-098

Handley, K. M., and Lloyd, J. R. (2013). Biogeochemical implications of the ubiquitous colonization of marine habitats and redox gradients by Marinobacter species. Front. Microbiol. 4:136. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2013.00136

Hansel, C. M. (2017). Manganese in marine microbiology. Microbiol. Metal Ions 70, 37–83. doi: 10.1016/bs.ampbs.2017.01.005

Haque, M. M., Oliver, M. M. H., Nahar, K., Alam, M. Z., Hirata, H., and Tsuyumu, S. (2017). CytR homolog of Pectobacterium carotovorum subsp. carotovorum controls air-liquid biofilm formation by regulating multiple genes involved in cellulose production, c-di-GMP signaling, motility, and type III secretion system in response to nutritional and environmental signals. Front. Microbiol. 8:972. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.00972

Hisert, K. B., MacCoss, M., Shiloh, M. U., Darwin, K. H., Singh, S., Jones, R. A., et al. (2005). A glutamate-alanine-leucine (EAL) domain protein of Salmonella controls bacterial survival in mice, antioxidant defence and killing of macrophages: role of cyclic diGMP. Mol. Microbiol. 56, 1234–1245. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04632.x

Horsburgh, M. J., Wharton, S. J., Cox, A. G., Ingham, E., Peacock, S., and Foster, S. J. (2002). MntR modulates expression of the PerR regulon and superoxide resistance in Staphylococcus aureus through control of manganese uptake. Mol. Microbiol. 44, 1269–1286. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2002.02944.x

Huang, C. J., Wang, Z. C., Huang, H. Y., Huang, H. D., and Peng, H. L. (2013). YjcC, a c-di-GMP phosphodiesterase protein, regulates the oxidative stress response and virulence of Klebsiella pneumoniae CG43. PLoS One 8:e66740. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0066740

Humphris, S., Zierenberg, R. A., Mullineaux, L. S., and Thomson, R. E. (1996). Seafloor hydrothermal systems: Physical, chemical, biological, and geological interactions. Science 271, 1508–1508.

Imlay, J. A. (2013). The molecular mechanisms and physiological consequences of oxidative stress: lessons from a model bacterium. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 11, 443–454. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro3032

Jimenez-Fernandez, A., Lopez-Sanchez, A., Calero, P., and Govantes, F. (2015). The c-di-GMP phosphodiesterase BifA regulates biofilm development in Pseudomonas putida. Environ. Microbiol. Rep. 7, 78–84. doi: 10.1111/1758-2229.12153

Juttukonda, L. J., Chazin, W. J., and Skaar, E. P. (2016). Acinetobacter baumannii coordinates urea metabolism with metal import to resist host-mediated metal limitation. mBio 7:e01475-16. doi: 10.1128/mBio.01475-16

Kaur, J., and Schoonen, M. A. (2017). Non-linear hydroxyl radical formation rate in dispersions containing mixtures of pyrite and chalcopyrite particles. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 206, 364–378. doi: 10.1016/j.gca.2017.03.011

Kehl-Fie, T. E., Zhang, Y., Moore, J. L., Farrand, A. J., Hood, M. I., Rathi, S., et al. (2013). MntABC and MntH contribute to systemic Staphylococcus aureus infection by competing with calprotectin for nutrient manganese. Infect. Immun. 81, 3395–3405. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00420-13

Kelso, G. F., Maroz, A., Cocheme, H. M., Logan, A., Prime, T. A., Peskin, A. V., et al. (2012). A mitochondria-targeted macrocyclic Mn(II) superoxide dismutase mimetic. Chem. Biol. 19, 1237–1246. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2012.08.005

Kim, D. G., Jiang, S., Jeong, K., and Ko, S. O. (2012). Removal of 17 alpha-ethinylestradiol by biogenic manganese oxides produced by the Pseudomonas putida strain MnB1. Water Air Soil Pollut. 223, 837–846. doi: 10.1007/s11270-011-0906-6

Kim, Y. C., Miller, C. D., and Anderson, A. J. (1999). Transcriptional regulation by iron of genes encoding iron- and manganese-superoxide dismutases from Pseudomonas putida. Gene 239, 129–135. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1119(99)00369-8

Kolenbrander, P. E., Andersen, R. N., Baker, R. A., and Jenkinson, H. F. (1998). The adhesion-associated sca operon in Streptococcus gordonii encodes an inducible high-affinity ABC transporter for Mn2+ uptake. J. Bacteriol. 180, 290–295.

Kong, L., Hu, X., and He, M. (2015). Mechanisms of Sb(III) oxidation by pyrite-induced hydroxyl radicals and hydrogen peroxide. Environ. Sci. Technol. 49, 3499–3505. doi: 10.1021/es505584r

Kubota, H., Senda, S., Nomura, N., Tokuda, H., and Uchiyama, H. (2008). Biofilm formation by lactic acid bacteria and resistance to environmental stress. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 106, 381–386. doi: 10.1263/jbb.106.381

Kuchma, S. L., Brothers, K. M., Merritt, J. H., Liberati, N. T., Ausubel, F. M., and O’Toole, G. A. (2007). BifA, a cyclic-di-GMP phosphodiesterase, inversely regulates biofilm formation and swarming motility by Pseudomonas aeruginosa PA14. J. Bacteriol. 189, 8165–8178. doi: 10.1128/Jb.00586-07

Lee, S., Takahashi, Y., Oura, H., Suzuki-Minakuchi, C., Okada, K., Yamane, H., et al. (2016). Effects of carbazole-degradative plasmid pCAR1 on biofilm morphology in Pseudomonas putida KT2440. Environ. Microbiol. Rep. 8, 261–271. doi: 10.1111/1758-2229.12376

Lee, S. W., Parker, D. L., Geszvain, K., and Tebo, B. M. (2014). Effects of exogenous pyoverdines on Fe availability and their impacts on Mn(II) oxidation by Pseudomonas putida GB-1. Front. Microbiol. 5:301. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2014.00301

Lee, Y., Pena-Llopis, S., Kang, Y. S., Shin, H. D., Demple, B., Madsen, E. L., et al. (2006). Expression analysis of the fpr (ferredoxin-NADP + reductase) gene in Pseudomonas putida KT2440. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 339, 1246–1254. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.11.135

Lewis, K. (2008). Multidrug tolerance of biofilms and persister cells. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 322, 107–131. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-75418-3_6

Loo, C. Y., Mitrakul, K., Voss, I. B., Hughes, C. V., and Ganeshkumar, N. (2003). Involvement of the adc operon and manganese Homeostasis in Streptococcus gordonii biofilm formation. J. Bacteriol. 185, 2887–2900. doi: 10.1128/Jb.185.9.2887-2900.2003

Lopez-Sanchez, A., Jimenez-Fernandez, A., Calero, P., Gallego, L. D., and Govantes, F. (2013). New methods for the isolation and characterization of biofilm-persistent mutants in Pseudomonas putida. Environ. Microbiol. Rep. 5, 679–685. doi: 10.1111/1758-2229.12067

Mahal, H. S., Kapoor, S., Satpati, A. K., and Mukherjee, T. (2005). Radical scavenging and catalytic activity of metal-phenolic complexes. J. Phys. Chem. B 109, 24197–24202. doi: 10.1021/jp0549430

Manara, A., DalCorso, G., Baliardini, C., Farinati, S., Cecconi, D., and Furini, A. (2012). Pseudomonas putida response to cadmium: changes in membrane and cytosolic proteomes. J. Proteome Res. 11, 4169–4179. doi: 10.1021/pr300281f

Matallana-Surget, S., Joux, F., Raftery, M. J., and Cavicchioli, R. (2009). The response of the marine bacterium Sphingopyxis alaskensis to solar radiation assessed by quantitative proteomics. Environ. Microbiol. 11, 2660–2675. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2009.01992.x

Matilla, M. A., Travieso, M. L., Ramos, J. L., and Ramos-Gonzalez, M. I. (2011). Cyclic diguanylate turnover mediated by the sole GGDEF/EAL response regulator in Pseudomonas putida: its role in the rhizosphere and an analysis of its target processes. Environ. Microbiol. 13, 1745–1766. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2011.02499.x

Meng, Y. T., Zheng, Y. M., Zhang, L. M., and He, J. Z. (2009). Biogenic Mn oxides for effective adsorption of Cd from aquatic environment. Environ. Pollut. 157, 2577–2583. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2009.02.035

Miao, L., and St Clair, D. K. (2009). Regulation of superoxide dismutase genes: Implications in disease. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 47, 344–356. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2009.05.018

Miner, K. D., and Kurtz, D. M. Jr. (2016). Active site metal occupancy and cyclic Di-GMP phosphodiesterase activity of Thermotoga maritima HD-GYP. Biochemistry 55, 970–979. doi: 10.1021/acs.biochem.5b01227

Mopper, K., and Zhou, X. (1990). Hydroxyl radical photoproduction in the sea and its potential impact on marine processes. Science 250, 661–664. doi: 10.1126/science.250.4981.661

Murata, M., Fujimoto, H., Nishimura, K., Charoensuk, K., Nagamitsu, H., Raina, S., et al. (2011). Molecular strategy for survival at a critical high temperature in Eschierichia coli. PLoS One 6:e20063. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0020063

Nealson, K. H., Tebo, B. M., and Rosson, R. A. (1988). Occurrence and mechanisms of microbial oxidation of manganese. Adv. Appl. Microbiol. 33, 279–318. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2164(08)70209-0

Nevo, Y., and Nelson, N. (2006). The NRAMP family of metal-ion transporters. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1763, 609–620. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2006.05.007

Nikel, P. I., Chavarria, M., Martinez-Garcia, E., Taylor, A. C., and de Lorenzo, V. (2013). Accumulation of inorganic polyphosphate enables stress endurance and catalytic vigour in Pseudomonas putida KT2440. Microb. Cell Fact. 12:50. doi: 10.1186/1475-2859-12-50

Osterberg, S., Aberg, A., Herrera Seitz, M. K., Wolf-Watz, M., and Shingler, V. (2013). Genetic dissection of a motility-associated c-di-GMP signalling protein of Pseudomonas putida. Environ. Microbiol. Rep. 5, 556–565. doi: 10.1111/1758-2229.12045

O’Toole, G. A., and Kolter, R. (1998). Initiation of biofilm formation in Pseudomonas fluorescens WCS365 proceeds via multiple, convergent signalling pathways: a genetic analysis. Mol. Microbiol. 28, 449–461. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00797.x

Ouyang, K., Yu, X. Y., Zhu, Y., Gao, C., Huang, Q., and Cai, P. (2017). Effects of humic acid on the interactions between zinc oxide nanoparticles and bacterial biofilms. Environ. Pollut. 231(Pt 1), 1104–1111. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2017.07.003

Pan, Y. (2011). Mitochondria, reactive oxygen species, and chronological aging: a message from yeast. Exp. Gerontol. 46, 847–852. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2011.08.007

Papp-Wallace, K. M., and Maguire, M. E. (2006). Manganese transport and the role of manganese in virulence. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 60, 187–209. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.60.080805.142149

Park, S. H., Singh, H., Appukuttan, D., Jeong, S., Choi, Y. J., Jung, J. H., et al. (2017). PprM, a cold shock domain-containing protein from Deinococcus radiodurans, confers oxidative stress tolerance to Escherichia coli. Front. Microbiol. 7:2124. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.02124

Park, W., Pena-Llopis, S., Lee, Y., and Demple, B. (2006). Regulation of superoxide stress in Pseudomonas putida KT2440 is different from the SoxR paradigm in Escherichia coli. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 341, 51–56. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.12.142

Parker, D. L., Lee, S. W., Geszvain, K., Davis, R. E., Gruffaz, C., Meyer, J. M., et al. (2014). Pyoverdine synthesis by the Mn(II)-oxidizing bacterium Pseudomonas putida GB-1. Front. Microbiol. 5:202. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2014.00202

Purcell, E. B., McKee, R. W., Courson, D. S., Garrett, E. M., McBride, S. M., Cheney, R. E., et al. (2017). A nutrient-regulated cyclic diguanylate phosphodiesterase controls clostridium difficile biofilm and toxin production during stationary phase. Infect. Immun. 85:e00347-17. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00347-17

Qin, L., Han, P. P., Chen, L. Y., Walk, T. C., Li, Y. S., Hu, X. J., et al. (2017). Genome-wide identification and expression analysis of NRAMP family genes in soybean (Glycine max L.). Front. Plant Sci. 8:1436. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2017.01436

Raiger-Iustman, L. J., and Ruiz, J. A. (2008). The alternative sigma factor, sigmaS, affects polyhydroxyalkanoate metabolism in Pseudomonas putida. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 284, 218–224. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2008.01203.x

Rajkumar, M., and Freitas, H. (2008). Influence of metal resistant-plant growth-promoting bacteria on the growth of Ricinus communis in soil contaminated with heavy metals. Chemosphere 71, 834–842. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2007.11.038

Ray, P., Girard, V., Gault, M., Job, C., Bonneu, M., Mandrand-Berthelot, M. A., et al. (2013). Pseudomonas putida KT2440 response to nickel or cobalt induced stress by quantitative proteomics. Metallomics 5, 68–79. doi: 10.1039/c2mt20147j

Reboucas, J. S., Spasojevic, I., and Batinic-Haberle, I. (2008). Quality of potent Mn porphyrin-based SOD mimics and peroxynitrite scavengers for pre-clinical mechanistic/therapeutic purposes. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 48, 1046–1049. doi: 10.1016/j.jpba.2008.08.005

Rees, D. C., Johnson, E., and Lewinson, O. (2009). ABC transporters: the power to change. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 10, 218–227. doi: 10.1038/nrm2646

Reguera, G., McCarthy, K. D., Mehta, T., Nicoll, J. S., Tuominen, M. T., and Lovley, D. R. (2005). Extracellular electron transfer via microbial nanowires. Nature 435, 1098–1101. doi: 10.1038/nature03661

Reguera, G., Nevin, K. P., Nicoll, J. S., Covalla, S. F., Woodard, T. L., and Lovley, D. R. (2006). Biofilm and nanowire production leads to increased current in Geobacter sulfurreducens fuel cells. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72, 7345–7348. doi: 10.1128/Aem.01444-06

Reguera, G., Pollina, R. B., Nicoll, J. S., and Lovley, D. R. (2007). Possible nonconductive role of Geobacter sulfurreducens pilus nanowires in biofilm formation. J. Bacteriol. 189, 2125–2127. doi: 10.1128/Jb.01284-06

Romling, U., Galperin, M. Y., and Gomelsky, M. (2013). Cyclic di-GMP: the first 25 years of a universal bacterial second messenger. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 77, 1–52. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00043-12

Ross, P., Mayer, R., Weinhouse, H., Amikam, D., Huggirat, Y., Benziman, M., et al. (1990). The cyclic diguanylic acid regulatory system of cellulose synthesis in Acetobacter xylinum. Chemical synthesis and biological activity of cyclic nucleotide dimer, trimer, and phosphothioate derivatives. J. Biol. Chem. 265, 18933–18943.

Ruiz, L. M., Castro, M., Barriga, A., Jerez, C. A., and Guiliani, N. (2012). The extremophile Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans possesses a c-di-GMP signalling pathway that could play a significant role during bioleaching of minerals. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 54, 133–139. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-765X.2011.03180.x