- 1Philips Institute for Oral Health Research, Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, VA, United States

- 2Department of Microbiology and Immunology, Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, VA, United States

- 3Center for the Study of Biological Complexity, Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, VA, United States

Streptococcus sanguinis is an early colonizer of tooth surfaces and a key player in plaque biofilm development. However, the mechanism of biofilm formation of S. sanguinis is still unclear. Here, we showed that deletion of a transcription factor, brpL, promotes cell aggregation and biofilm formation in S. sanguinis SK36. Glucan, a polysaccharide synthesized from sucrose, was over-produced and aggregated in the biofilm of ΔbrpL, which was necessary for better biofilm formation ability of ΔbrpL. Quantitative RT-PCR demonstrated that gtfP was significantly up-regulated in ΔbrpL, which increased the productions of water-insoluble and water-soluble glucans. The ΔbrpLΔgtfP double mutant decreased biofilm formation ability of ΔbrpL to a level similar like that of ΔgtfP. Interestingly, the biofilm of ΔbrpL had an increased tolerance to ampicillin treatment, which might be due to better biofilm formation ability through the mechanisms of cellular and glucan aggregation. RNA sequencing and quantitative RT-PCR revealed the modulation of a group of genes in ΔbrpL was mediated by activating the expression of ciaR, another gtfP-related biofilm formation regulator. Double deletion of brpL and ciaR decreased biofilm formation ability to the phenotype of a ΔciaR mutant. Additionally, RNA sequencing elucidated a broad range of genes, related to carbohydrate metabolism and uptake, were activated in ΔbrpL. SSA_0222, a gene involved in the phosphotransferase system, was dramatically up-regulated in ΔbrpL and essential for S. sanguinis survival under our experimental conditions. In summary, brpL modulates glucan production, cell aggregation and biofilm formation by regulating the expression of ciaR in S. sanguinis SK36.

Introduction

Biofilms are structured, surface-associated communities of microorganisms, which attach to biotic and abiotic surfaces, leading to several acute and chronic health conditions in humans, such as periodontitis (Brouwer et al., 2016; Bergenfelz and Hakansson, 2017; Kreth et al., 2017). The microorganisms in biofilms are encased in a self-produced matrix of hydrated extracellular polymeric substances (EPS) that comprises of polysaccharides, proteins, nucleic acids, and lipids (Flemming and Wingender, 2010). The EPS confers many advantages to microorganisms in response to environmental stresses encountered in the natural and host environments, such as protection of the cells against oxidizing agents, desiccation or the host’s immune defenses. Biofilms also promote horizontal gene transfer by establishing connections between cells that are in close proximity and not fully immobilized (Flemming and Wingender, 2010). Ultimately, due to multiple tolerance mechanisms, bacterial biofilms are highly resistant to antimicrobial therapy and immune clearance, making them extremely effective and persistent invaders and very difficult to eradicate (Davies, 2003).

Streptococcus sanguinis (S. sanguinis), a Gram-positive facultative anaerobe, exists on tooth surfaces, oral mucosa surfaces and in human saliva (Gross et al., 2012; Francavilla et al., 2014; Seoudi et al., 2015). It does not appear to play a direct role in oral disease, however, it has been reported that oral S. sanguinis is frequently the cause of infective endocarditis, a potentially fatal biofilm-associated disease (Bor et al., 2013; Crump et al., 2014). The bacteria can enter the bloodstream via the mouth, gastrointestinal tract or the skin (Duval and Leport, 2008; Holland et al., 2016). Individuals with damage to their heart valve, such as from a congenital heart condition, form ‘vegetation,’ fibrin-platelet complexes, in which the bacteria colonize causing infective endocarditis (Cahill and Prendergast, 2016).

Within the oral cavity, S. sanguinis might even be considered a beneficial bacterium with regards to dental caries, as it plays an antagonistic role of competitive exclusion against pathogenic S. mutans, depending on the sequence of inoculation (Kreth et al., 2005). However, although thought to be benign, S, sanguinis is a pioneering contributor to the biofilm in the human oral cavity known as dental plaque (Socransky et al., 1977; Xu et al., 2011). The adhesion of pioneer bacterial colonizers, such as S. sanguinis, to a salivary glycol-protein surface via required anchoring receptors, is essential for the initiation of biofilm development. Thus, S. sanguinis may provide a new surface whilst modulating the environment to make it more hospitable for the localization of succeeding microorganisms, which could include pathogens (Maeda et al., 2004).

Hitherto, there are few papers published on the attachment or biofilm formation of S. sanguinis. Carbohydrates consumed in the diet are the primary nutrients influencing biofilm formation and sucrose is considered the most cariogenic dietary carbohydrate. Glucosyltransferases (GTFs) are important in sucrose induced plaque formation (Rölla et al., 1985). When using sucrose as the carbon source, GtfP, the only GTF present in S. sanguinis, is responsible for glucan synthesis and essential for biofilm formation in S. sanguinis (Yoshida et al., 2014; Liu et al., 2017). The overexpression of the gtfP gene promotes the production of water-insoluble glucan (WIG) and water-soluble glucan (WSG), which aids biofilm formation (Yoshida et al., 2014; Liu et al., 2017). Transcription of gtfP is repressed by an increase in the expression of the arginine (arg) biosynthesis gene (Zhu et al., 2017). Arg expression is upregulated by the deletion of the ciaR gene, part of the CiaH/R two-component system response regulator (CiaR), a well-studied transcription regulator that modulates biofilm formation in S. sanguinis (Zhu et al., 2017). It has been shown that a ΔciaR mutant with reduced gtfP expression produces less extracellular glucan resulting in deficient biofilm formation (Zhu et al., 2017). Conversely, the deletion of another transcription regulator, brpT (Biofilm Regulatory Protein TetR), in S. sanguinis, promotes biofilm formation by up-regulating the transcription of gtfP, in turn generating more glucan (Liu et al., 2017).

A further important component of the EPS is extracellular DNA (eDNA) for which a role in initial biofilm formation has been firmly established. Whitchurch et al. (2002) demonstrated that the addition of DNase I to the medium of Pseudomonas aeruginosa markedly inhibited biofilm initiation in the early stages of growth. Established biofilms were minimally affected (Whitchurch et al., 2002). Furthermore, psl (polysaccharide synthesis locus) transcribes a polysaccharide that can react with eDNA to form a fiber-like web that shapes the biofilm skeleton in P. aeruginosa (Wang et al., 2013). In S. mutans, eDNA could also cooperate with polysaccharide to impact the early stage of biofilm formation (Castillo Pedraza et al., 2017). However, it is not yet clear whether eDNA contributes to S. sanguinis biofilm formation.

Our previous work has constructed a comprehensive mutant library of S. sanguinis SK36 (Xu et al., 2011). We performed a high-throughput biofilm assay (unpublished data) in which SSA_0427 was identified as a biofilm-related transcription factor. Genome annotation predicts that the function of coding sequence SSA_0427 is similar to an antibiotic regulatory protein (SARP) family transcription factor in Streptomyces (Xu et al., 2007). However, by using amino acid sequence alignment, we propose an alternative function for BrpL as a LuxR family transcriptional regulator. BrpL is highly conserved in S. sanguinis, S. pyogenes, S. gordonii, S. cristatus, S. dysgalactiae, S. parauberis, and S. canis (Supplementary Figure S1A). No ortholog gene of SSA_0427 was found in S. mutans or S. pneumoniae. The secondary structure of SSA_0427 was predicted by SMART1 (Letunic et al., 2006), to be a classical structure in LuxR family proteins, comprising of a bacterial transcriptional activator domain, a Pfam domain, three TRP domains and a tetratricopeptide repeat (Supplementary Figure S1B).

In this study, we showed that the deletion of the SSA_0427 gene was detrimental to biofilm formation in S. sanguinis SK36. As a result, it was named brpL (Biofilm Regulatory Protein LuxR). We used confocal laser scanning microscopy (CLSM), quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) and functional assays to characterize the role of brpL in the regulation of glucan production, cell aggregation and biofilm formation. RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) data revealed that ciaR mediated the elevation of biofilm formation in ΔbrpL.

Results

Deletion of brpL in S. sanguinis SK36 Increases Cell-Surface Attachment Strength

In our previous work, a comprehensive mutant library of S. sanguinis SK36 was generated by high-throughput PCR (Xu et al., 2011). Firstly, we analyzed biofilm formation of predicted transcriptional regulator mutants by the growth of biofilms plated on polystyrene microtiter plates overnight under microaerobic conditions. All strains were grown in BM media supplemented with 1% sucrose and biofilms examined using CV staining. Our initial screening indicated that deletion of the brpL gene resulted in an increased biofilm phenotype in comparison to the wild-type SK36 (WT) (data not shown). To validate whether brpL was a biofilm related gene, we recorded growth curves of ΔbrpL and WT in BM supplemented with 1% sucrose. More rapid growth of the ΔbrpL mutant biofilm in comparison to the WT was observed in early log phase although a similar cell density was observed at stationary phase (Supplementary Figure S2A). Due to bacterial cell aggregation, colony forming units (CFU) could not be counted accurately. WT and ΔbrpL strains were grown in BM supplemented with 1% sucrose for 7.5 h. The cells were then harvested, stained by crystal violet (CV) and biomass was recorded by digital pictures (Supplementary Figure S2B). It was observed that ΔbrpL accumulated more biomass than WT, indicating a faster growth rate of ΔbrpL. More severe aggregation appeared in ΔbrpL at late log phase, which increased the standard deviations of the OD600 values (Supplementary Figure S2A). Growth curve comparison could not exclude the possibility that better biofilm formation of ΔbrpL was caused by increased growth rate.

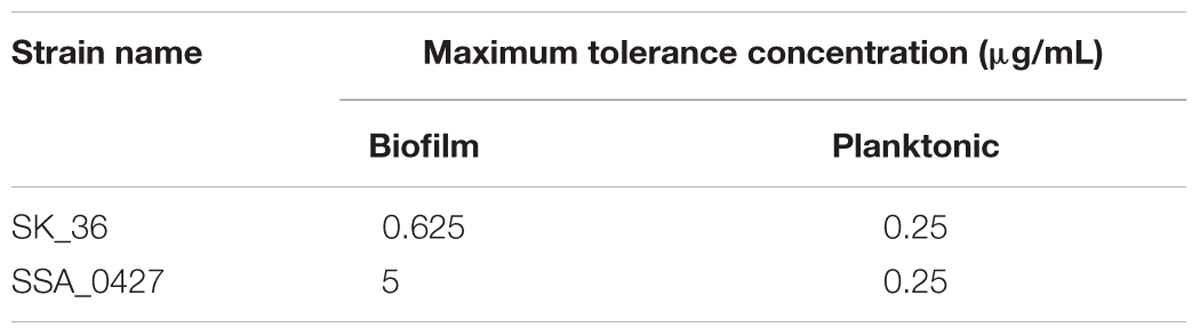

To further explore the precise mechanism for improved biofilm phenotype in the ΔbrpL deletion mutant, the cell-surface attachment of the biofilms was investigated. Resulting biofilms from the growth assay were washed using a Caliper Sciclone G3 liquid handling robot (PerkinElmer, United States) which generated different speeds of washing flow. A higher magnitude of difference was seen after a severe wash (Figure 1), which suggested that the ΔbrpL mutant had better attachment ability to the surface of polystyrene plates (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1. The biofilm attachment of WT and ΔbrpL on polystyrene microtiter plates. The 1-day biofilms of WT and ΔbrpL were quantified by CV staining. The washing steps were done by using a Caliper Sciclone G3 liquid handling robot with different washing speeds. P-values were generated by Student’s t-test. Means and standard deviations from triplicate experiments are shown.

The Biofilm of ΔbrpL Contains More Biomass and Cell Aggregation

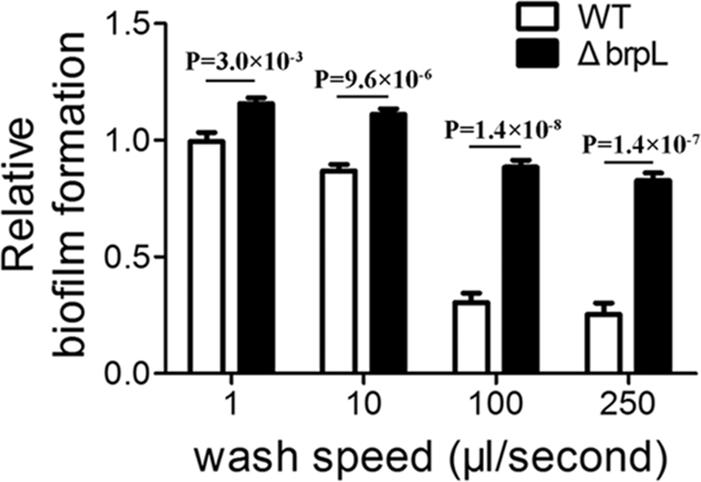

The structure of biofilm (thickness) and microbial characteristics (biomass and live/dead ratio) were investigated using CLSM and quantified using a COMSTAT script in Matlab software (Heydorn et al., 2000). Briefly, biofilms of WT and ΔbrpL were cultured in a 4-well chamber for 24 h and then treated with SYTO9 to mark live cells and propidium iodide (PI) to mark dead cells and eDNA. In comparison to WT biofilm, the biofilm of ΔbrpL was approximately twice as thick (WT: 17.4 ± 1.6 μm, ΔbrpL: 30.3 ± 6.9 μm) and formed nearly twice as much biomass (WT: 8.83 ± 1.28 μm3/μm2, ΔbrpL: 15.13 ± 1.22 μm3/μm2) (Figure 2A). This result demonstrated a superior biofilm formation ability of ΔbrpL in comparison to WT, which was consistent with the finding of increased attachment ability (Figure 1). Moreover, a significantly stronger PI (red) signal appeared in the biofilm of ΔbrpL, indicating a larger amount of dead cells and eDNA (Figure 2A).

FIGURE 2. The characteristic of biomass and cell distribution in the biofilms of WT and ΔbrpL. (A) The biofilms of WT and ΔbrpL were cultured in a 4-well chamber for 24 h, stained by SYTO 9 (green)/PI (red) and captured by CLSM. 3D architectures of biofilms were shown on the top. Biomass (the signal of SYTO 9) and PI signal representing dead cells and eDNA in CLSM images were calculated by COMSTAT analysis (mean ± SD). Average and maximum thickness were quantified by COMSTAT based on the signal of SYTO 9 (mean ± SD). (B) Heat maps showing the thickness of biofilms (overlap of biomass in all slices) were made by COMSTAT analysis, which reflected the distribution of biomass in biofilms. Blue arrows point to cell aggregation in the biofilm of ΔbrpL. Scale bars were indicated on the corresponding images. All the data in (A) are compared with their WT control. ∗∗P ≤ 0.01, Student’s t-test. Means and standard deviations from triplicate experiments are shown.

Figure 2B shows intensity maps of WT and mutant strain biofilms, which illustrates through color change, differences in biofilm thickness. The images were generated by Matlab script, COMSTAT (Heydorn et al., 2000). Cells were uniformly distributed in the biofilm of WT, but markedly aggregated in that of ΔbrpL (Figure 2B). An observation made but not quantified, was that cell aggregation accumulated at upper layers of the ΔbrpL biofilm and a cell cavity formed in the layers under a cell aggregate (Supplementary Figure S3). Cell aggregation could also be seen when strains were cultured in BM supplemented with 1% sucrose under shaking conditions (200 rpm) in 14 mL tubes (Supplementary Figure S4A). Additionally, many macrocolonies formed on the surface of a bacteriological petri dish in BM supplemented with 1% sucrose, providing further evidence of aggregation of the ΔbrpL mutant (Supplementary Figure S4B).

Cell Aggregation Is Not Caused by eDNA in ΔbrpL

Only very little PI signal (red) was seen in the biofilm of WT in comparison to ΔbrpL (Figure 2A). In fact, most of red signal have a cell-like shape, indicating they were dead cells rather than eDNA (Supplementary Figure S3). No eDNA signal smear was observed in the image (Supplementary Figure S3). These data implied that cell aggregation might not be promoted by a larger amount of eDNA. To further confirm this hypothesis, we treated the biofilms with 100 U/mL of DNase I which non-specifically cleaves eDNA. DNase I treatment did not result in any significant difference in biofilm formation, which suggested that eDNA did not impact biofilm formation under our experimental conditions (Supplementary Figure S5).

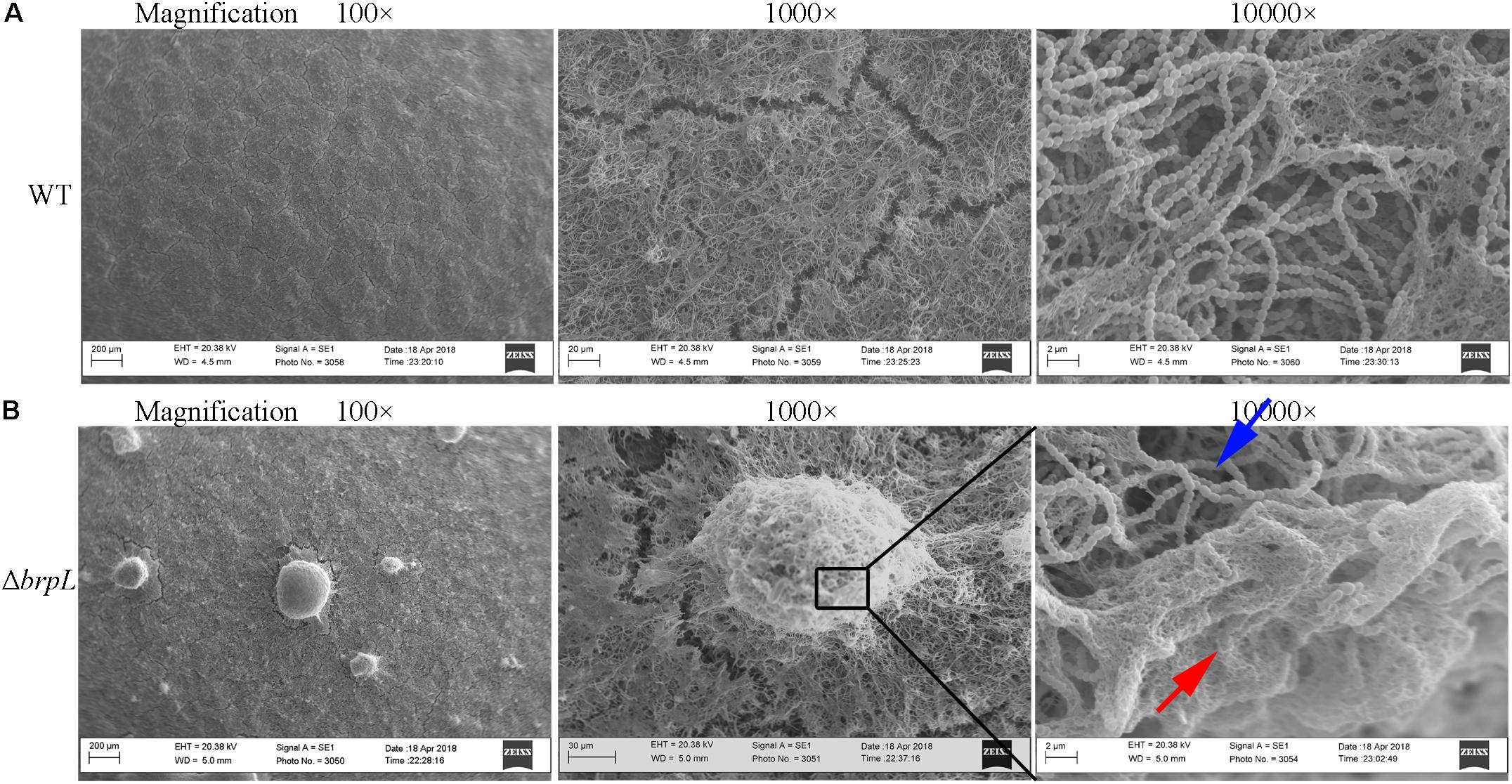

Dense Fiber-Like Matrix Exists in the Biofilm of ΔbrpL

To confirm cells aggregated in the biofilm of ΔbrpL, biofilms were observed by scanning electron microscopy (SEM), which showed a similar phenomenon that much more cell aggregation appeared on the surface of ΔbrpL biofilm than that of WT (Figure 3, 100-fold magnified figures). Fiber-like matrix existed on the surface of both WT but seemingly more abundant in the biofilm of ΔbrpL (Figure 3). A larger amount of fiber-like matrix linked cells together, which might lead to a better biofilm formation ability of ΔbrpL. The 10000-fold magnified figure showed an interesting result that the periphery of cell aggregation in the biofilm of ΔbrpL was fully covered by a layer of fiber-like matrix (Figure 3B, red arrow). However, much less fiber-like matrix was observed in the center of the cell aggregate (Figure 3B, blue arrow). We put forward a theory that the cells closer to the periphery of the cellular aggregate are also closer to any nutrients which would facilitate the synthesis of fiber-like matrix.

FIGURE 3. The fiber-like matrix in the biofilms of WT and ΔbrpL. The 1-day biofilms of WT (A) and ΔbrpL (B) were captured by SEM with magnifications of 100×, 1000×, and 10000×, respectively. Scale bars were shown on each image. The red arrow indicates fiber-like matrix at the periphery of cell aggregation and the blue arrow points to cells inside of the aggregate.

The Deletion of brpL Promotes Polysaccharide Production and Aggregation

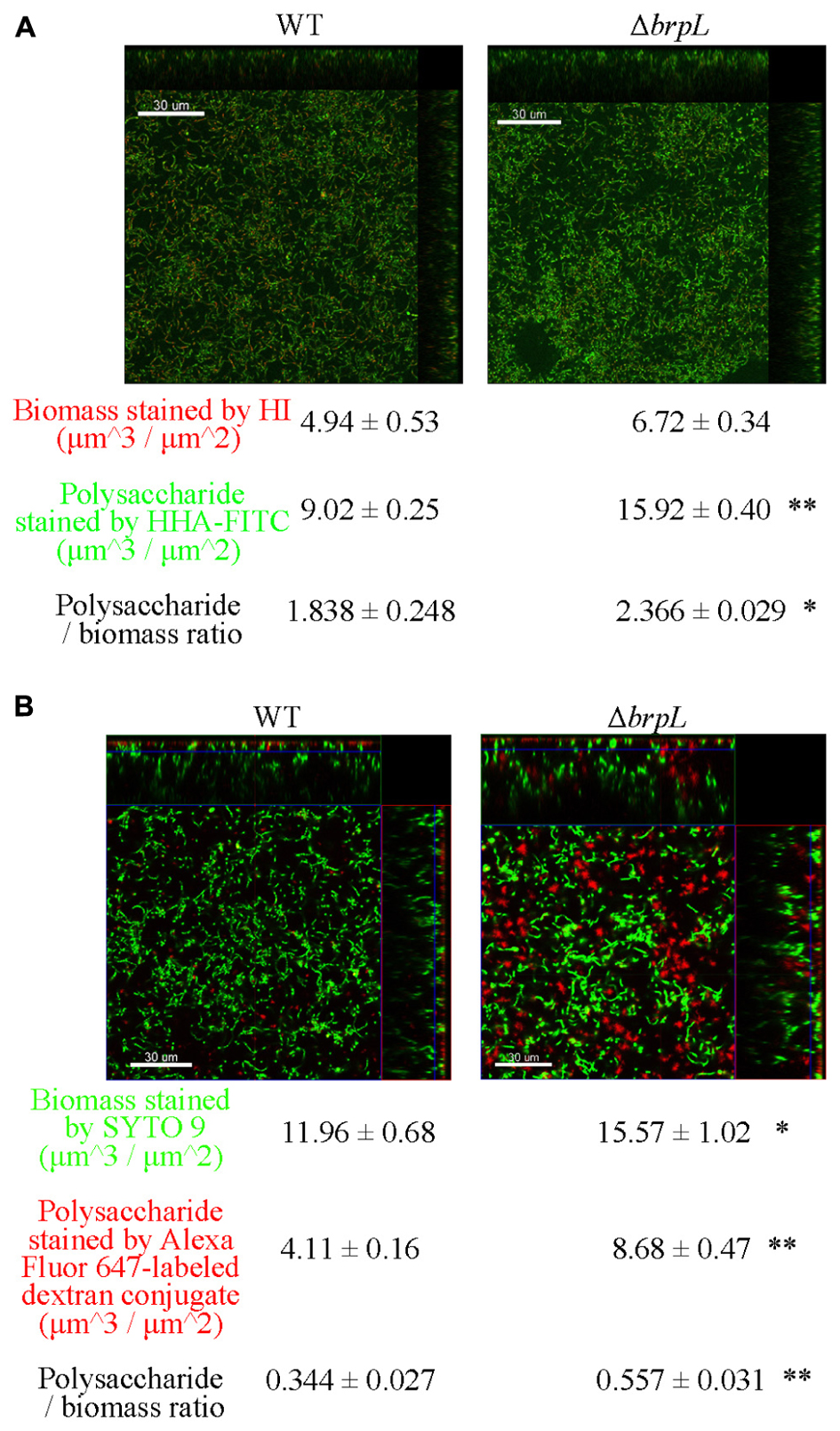

A previous study illustrated that filamentous structures were related to the production of glucan in ΔbrpT (Liu et al., 2017). In addition, the phenomenon of cell aggregation has been associated with the over-production of extracellular polysaccharide in other bacteria (Clark and Gibbons, 1977; McNab and Jenkinson, 1992; Zhu et al., 2016). To quantify the amount of polysaccharide, biofilms were grown in 4-well chambers for 24 h. Two methods were used to stain cells and polysaccharide. In Figure 4A, cells were identified by Hexidium iodide (HI) and polysaccharide, containing α-(1, 3) or α-(1, 6) linked mannosyl units, was stained by Hippeastrum hybrid lectin (HHA)-FITC (Ma et al., 2009). In Figure 4B, cells were marked by SYTO 9 and polysaccharide, with poly-(α-D-1, 6-glucose) linkages, was identified by Alexa Fluor 647-labeled dextran conjugate (Koo et al., 2010). Images were taken by CLSM and quantified using a COMSTAT script in Matlab (Heydorn et al., 2000). Both staining methods showed that the ratio of polysaccharide/biomass of ΔbrpL was greater than that of WT, which suggested ΔbrpL had better polysaccharide production ability (Figure 4). The signal of polysaccharide with mannosyl units overlapped with cells (Figure 4A), indicating that this kind of polysaccharide existed on cell surface or inside of cells. However, the polysaccharide with α-(1, 6) linked glucosyl units localized in the gaps between cells (Figure 4B), which might indicate component of fiber-like matrix.

FIGURE 4. The distribution of polysaccharide in the biofilms of WT and ΔbrpL. The 1-day biofilms were cultured in 4-well chambers for 24 h. (A) Biofilms were stained by HHA-FITC (green)/HI (red), which marked polysaccharide with mannosyl units and cells, respectively. (B) Cells in biofilms were stained by SYTO 9 (green) and polysaccharide with poly-(α-D-1, 6-glucose) linkages was marked by Alexa Fluor 647-labeled dextran conjugate (red). CLSM images were shown. Scale bars were indicated on the corresponding images. Biomass, polysaccharide production and biomass/polysaccharide ratio were calculated by COMSTAT analysis (mean ± SD). All the data in (A,B) are compared with their WT control. ∗P ≤ 0.05, ∗∗P ≤ 0.01, Student’s t-test. Means and standard deviations from triplicate experiments are shown.

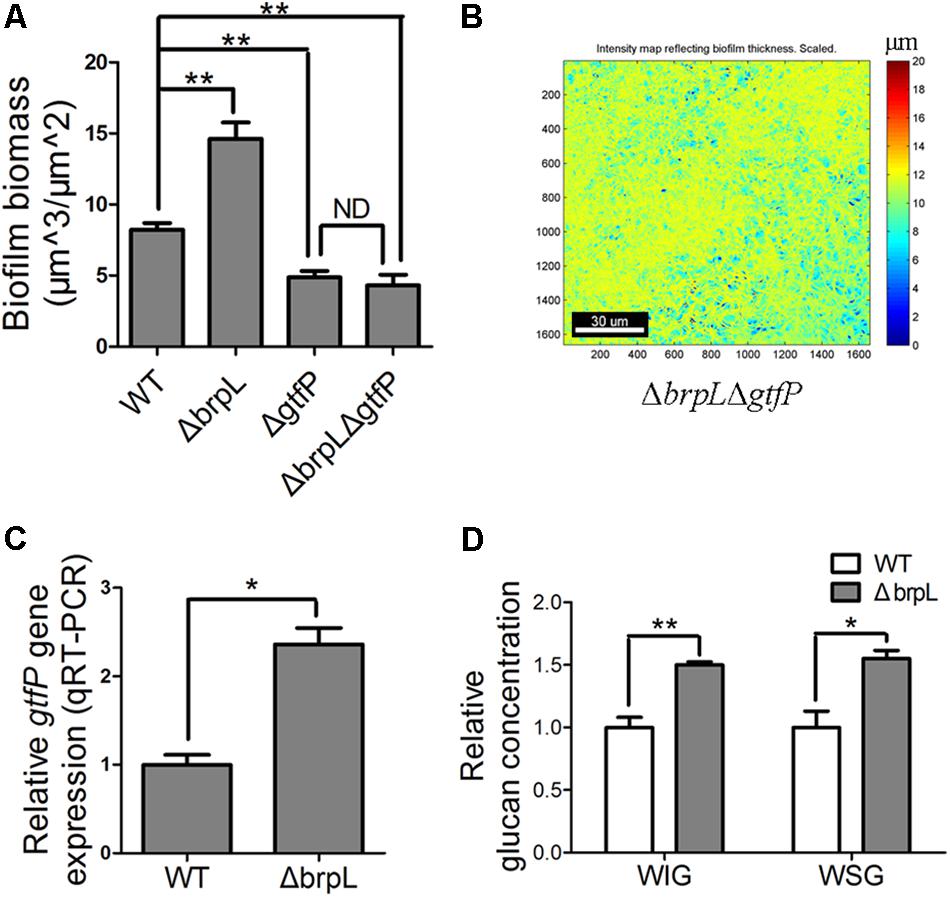

gtfP Is Important for ΔbrpL to Impact Biofilm Formation

Glucan, a polysaccharide of D-glucose monomers, is one of the most important polysaccharide for biofilm formation of S. sanguinis (Yoshida et al., 2014; Liu et al., 2017). GtfP, the only GTF in S. Sanguinis, is essential for glucan production (Yoshida et al., 2014; Liu et al., 2017). To understand the role of glucan in the biofilm of ΔbrpL, a ΔbrpLΔgtfP double mutant was constructed and the biofilm biomass was stained by SYTO 9/PI and observed by CLSM. The biomass of ΔgtfP was significantly (P ≤ 0.01) less than WT (Figure 5A and Supplementary Figure S6). The ΔbrpLΔgtf double decreased biomass to show a similar phenotype to a ΔgtfP mutant (Figure 5A and Supplementary Figure S6). Furthermore, the ΔbrpLΔgtfP mutant could not promote cell aggregation (Figure 5B). These data suggested the effects of the brpL deletion on biofilm formation were solely through its ability to regulate gtfP expression and glucan was essential for cell aggregation.

FIGURE 5. The gtfP gene is important for ΔbrpL to regulate biofilm formation. (A) The biofilms were stained by SYTO 9 (green)/PI (red), visualized by CLSM and quantified by COMSTAT. Biofilm biomass was shown. (B) The heat map of biomass distribution in the biofilm of ΔbrpLΔgtfP was made by COMSTAT analysis. A scale bar was shown on the image. (C) qRT-PCR was performed to examine the expression of gtfP gene in ΔbrpL. (D) The WIG and WSG of WT and ΔbrpL were measured by the method described in section “Materials and Methods.” ∗P ≤ 0.05, ∗∗P ≤ 0.01, Student’s t-test. Means and standard deviations from triplicate experiments are shown. ND indicates no significant difference.

As the polysaccharide with α-(1, 6) linked glucosyl units was over-produced in ΔbrpL (Figure 4B), we hypothesized that gtfP, might be regulated by brpL. We quantified the transcription of gtfP by qRT-PCR, which illustrated that gtfP was significantly activated in ΔbrpL (Figure 5C). It has been demonstrated that GtfP is responsible for the generation of WIG and WSG (Yoshida et al., 2014; Liu et al., 2017). As a result, the concentrations of WIG and WSG were measured. The biofilm of ΔbrpL contained more WIG and WSG, which further confirmed that glucan was over-produced in ΔbrpL (Figure 5D). Glucan may be one of the essential components in the fiber-like matrix and may facilitate cell aggregation.

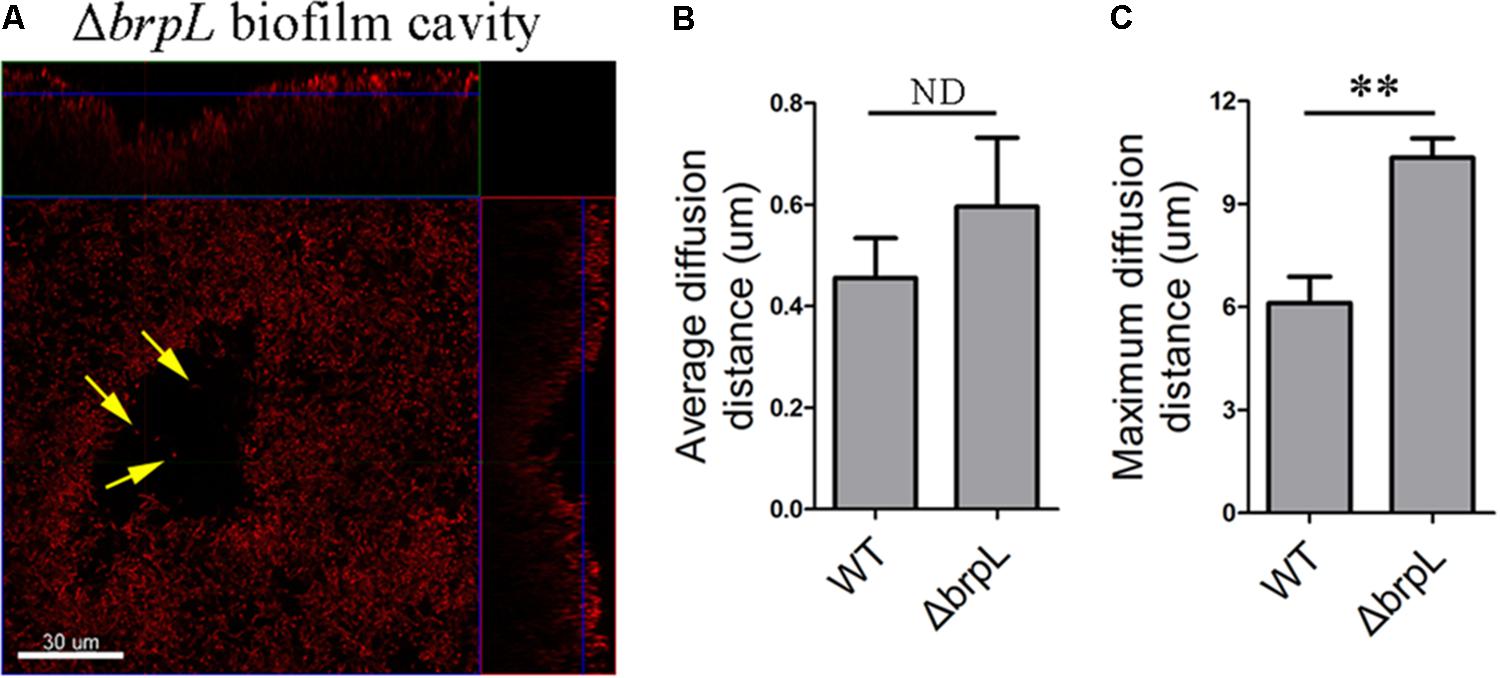

Cell Cavities Observed at the Location of Glucan Aggregation in the Biofilm of ΔbrpL

As illustrated in Supplementary Figure S3, cell cavities were observed in the biofilm of ΔbrpL. A similar phenomenon was well-studied in P. aeruginosa which forms mushroom-like three-dimensional microcolonies (Stoodley et al., 2002; Ma et al., 2009). Psl polysaccharide is distributed on the periphery of these microcolonies. Programed cell death generated cavities in the centers of microcolonies (Ma et al., 2009). Some planktonic cells live in these cavities for seeding dispersal (Ma et al., 2009). In the biofilm of ΔbrpL, a small number of single living cells were observed within cavity boundaries (Figure 6A). However, unlike P.aeruginosa, S. sanguinis SK36 is a non-motile bacterium, therefore it is uncertain whether these single cells were participating in seeding dispersal in S. sanguinis.

FIGURE 6. A biofilm cavity and single cells inside of the cavity. (A) The 1-day biofilm of ΔbrpL was stained by HI and then captured by CLSM. Yellow arrows point to single cells existed inside of the biofilm cavity. A scale bar was shown on the image. Based on the SYTO 9 signal of CLSM images in Figure 2A, average (B) and maximum (C) diffusion distances were measured by COMSTAT analysis to simulate the distance from nutrient to cells. ∗∗P ≤ 0.01, Student’s t-test. ND indicates no significant difference. Means and standard deviations from triplicate experiments are shown.

To examine whether or not cell aggregation was the cause of a cell cavity, we calculated the diffusion distance of nutrient to cells based on CLSM images in Figure 2 by using the COMSTAT script (Heydorn et al., 2000). For example, the maximum diffusion distance is the longest distance from the periphery of a microcolony to its center. The average diffusion distance is the average value from the periphery to every single cell. We found that although the average diffusion distances between WT and ΔbrpL were not significantly different, the ΔbrpL mutant had a significantly larger maximum diffusion distance (P-value ≤ 0.01) (Figures 6B,C). This would suggest a substantial proportion of nutrients may diffuse a much further distance to reach the cells at the center of an aggregate within a ΔbrpL biofilm. We hypothesize that the nutrients may be consumed by cells in closer proximity to the aggregate periphery, resulting in nutrient deficit of the inner cells and hence cell death. Additionally, a longer diffusion distance could also lead to the accumulation of harmful metabolites, such as acid or H2O2, which would to kill cells at the center of the cell aggregate.

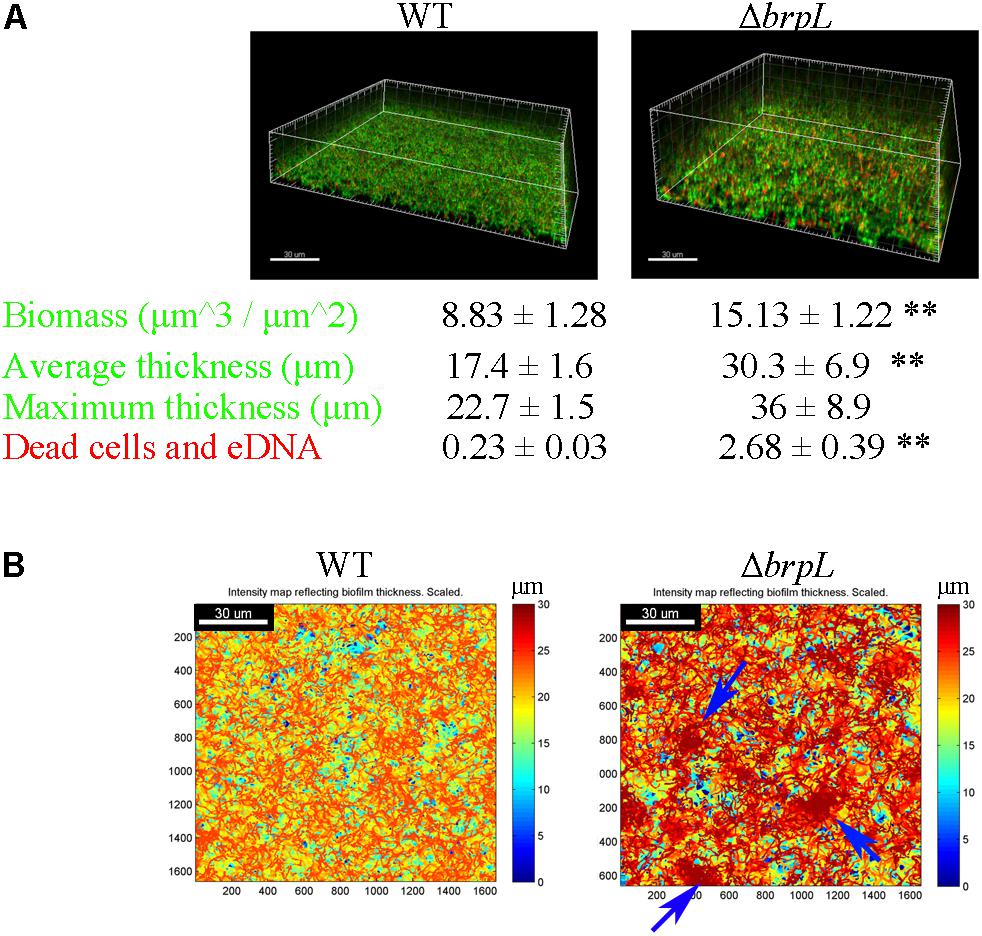

The Deletion of ΔbrpL Increased the Tolerance of Biofilm to Ampicillin Treatment

It has been widely reported that the aggregation of bacteria into EPS-coated biofilm is associated with increased antibiotic resistance (Davies, 2003). Polysaccharide is one of the most important components of EPS and contributes to antibiotic resistance (Flemming and Wingender, 2010). It is conceivable that cells inside of an aggregation might be protected by peripheral cells and polysaccharide from antibiotics attack in the biofilm of ΔbrpL. We treated planktonic cells and biofilms by series concentrations of ampicillin for 2 h, respectively. The tolerance of ΔbrpL was the same as that of WT in planktonic cells but eight times higher than the WT in the biofilm population (Table 1). This suggested that the tolerance to ampicillin treatment was increased by better biofilm formation ability in ΔbrpL (Table 1). Cell aggregation may be essential for this increased tolerance.

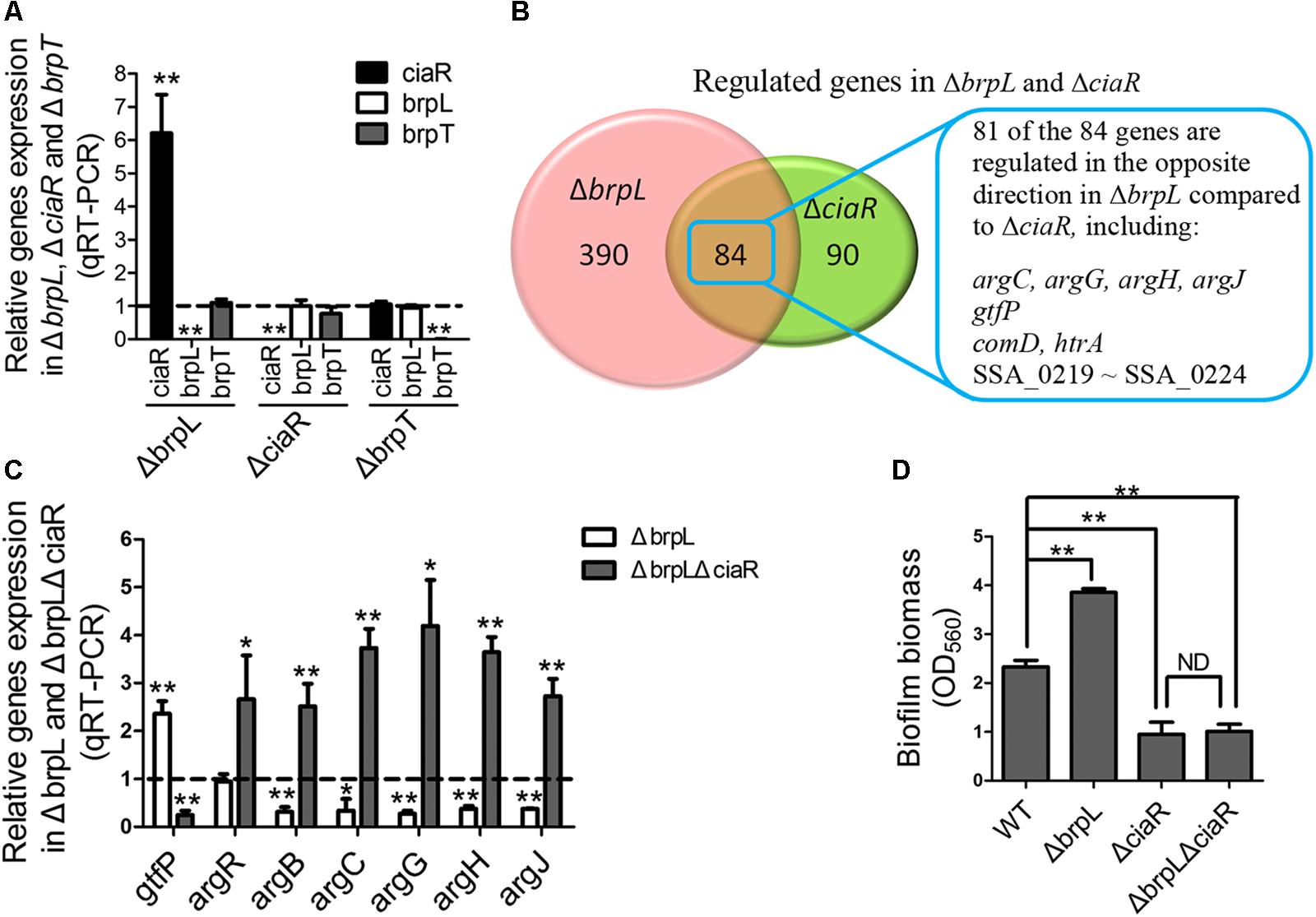

ΔbrpL Regulates a Group of Genes Through Promoting the Expression of ciaR

As mentioned above, previous works show that a response regulator, CiaR, of the CiaRH two-component system and a transcriptional regulator, BrpT, impact biofilm formation by affecting glucan production, which appears to be similar to brpL (Liu et al., 2017; Zhu et al., 2017). By using qRT-PCR, we tested the relationships between these three regulators. The only relationship was that the transcription of the ciaR gene was significantly increased in ΔbrpL (Figure 7A). To further explore the relationship between brpL and ciaR, RNA-seq of ΔbrpL was executed. Consistent with the qRT-PCR result, the expression of the ciaR gene was fivefold increased in ΔbrpL (Supplementary Datasheet 1). Furthermore, there were 474 genes significantly modulated (fold change ≥ 1.5 or ≤ 0.667 and P-value ≤ 0.05 in ΔbrpL), within which 84 genes were also regulated in ΔciaR (Figure 7B). Surprisingly, 81 of the 84 overlapped genes were regulated in the opposite direction in ΔbrpL compared to ΔciaR, including genes associated with arginine biosynthesis (argC, argG, argH, and argJ), glucan production (gtfP) and cell competence (comD and htrA) (Figure 7B). These data suggested that BrpL repressed the expression of ciaR in S. sanguinis SK36.

FIGURE 7. BrpL controls biofilm formation via a downstream regulator CiaR. (A) qRT-PCR was performed to examine the relationships of regulation between ciaR, brpL, and brpT. (B) Based on RNA-seq data (Supplementary Datasheet 1), the number of overlapped genes with differential expression (fold change ≥ 1.5 or ≤ 0.667 and p-value ≤ 0.05) in ΔbrpL and ΔciaR was shown by Venn diagram. (C) The expression of genes in WT, ΔbrpL and ΔbrpLΔciaR was tested by qRT-PCR. All of the data were relative to their WT controls. (D) The biofilm biomass of strains was measured by CV staining. ∗P ≤ 0.05, ∗∗P ≤ 0.01, Student’s t-test. Means and standard deviations from triplicate experiments are shown.

Furthermore, qRT-PCR results confirmed that argB, argC, argG, argH, and argJ were all significantly down-regulated in ΔbrpL (Figure 7C), which was in contrast to the upregulation of these genes seen in the ΔciaR mutant (Zhu et al., 2017). In addition, a ΔbrpLΔciaR double genes deletion mutant resulted in a phenotype similar to that of the ΔciaR where the arg genes were all up-regulated (Figure 7C) (Zhu et al., 2017). Similarly, the expression of gtfP was promoted in ΔbrpL, while suppressed in both ΔciaR and ΔbrpLΔciaR (Figure 7C) (Zhu et al., 2017). These results further confirmed that brpL modulated gtfP and the arg genes through the regulation of ciaR.

ΔbrpL Modulates Biofilm Formation Through the Downstream Regulator ciaR

Our previous work reveals that by promoting the expression of arginine biosynthetic genes, particularly the argB gene, the ciaR mutation reduces the expression of gtfP, resulting in a decreased glucan production and the formation of a fragile biofilm in S. sanguinis (Zhu et al., 2017). Additionally, the ΔargB mutant exhibited severe autoaggregation (Zhu et al., 2017). The transcription level of the argB gene was low in the ΔbrpL mutant (Figure 7C), which might contribute to the cell aggregation phenotype in ΔbrpL (Figures 2B, 3 and Supplementary Figure S4). We hypothesized that the activation of ciaR might facilitate ΔbrpL in enhancing biofilm formation and aggregation. To this end, we showed that the ΔbrpLΔciaR double mutant was deficient in biofilm formation and accumulated less cell aggregation (Figure 7D and Supplementary Figure S4B). Together, these data indicated that ciaR played an essential role in ΔbrpL to affect biofilm formation.

CiaH is the histidine kinase of the CiaH/R two-component system, which senses a stimulus and transfers a signal to the response regulator ciaR (Zähner et al., 2002). Previous works demonstrate that ciaH modulates biofilm formation in S. pneumoniae (Zähner et al., 2002). Here, we showed the deletion of ciaH also reduced biofilm formation in S. sanguinis (Supplementary Figure S7A). Conversely, the expression of ciaH was increased in ΔbrpL, which implied that both ciaH and ciaR participated in the network modulated by brpL (Supplementary Figure S7B). We propose a certain stimulus might be generated by the deletion of brpL, sensed by ciaH and responded to by ciaR to change biofilm formation in S. sanguinis.

Collectively, the above data suggested that ΔbrpL modulated biofilm formation through the downstream regulator ciaR.

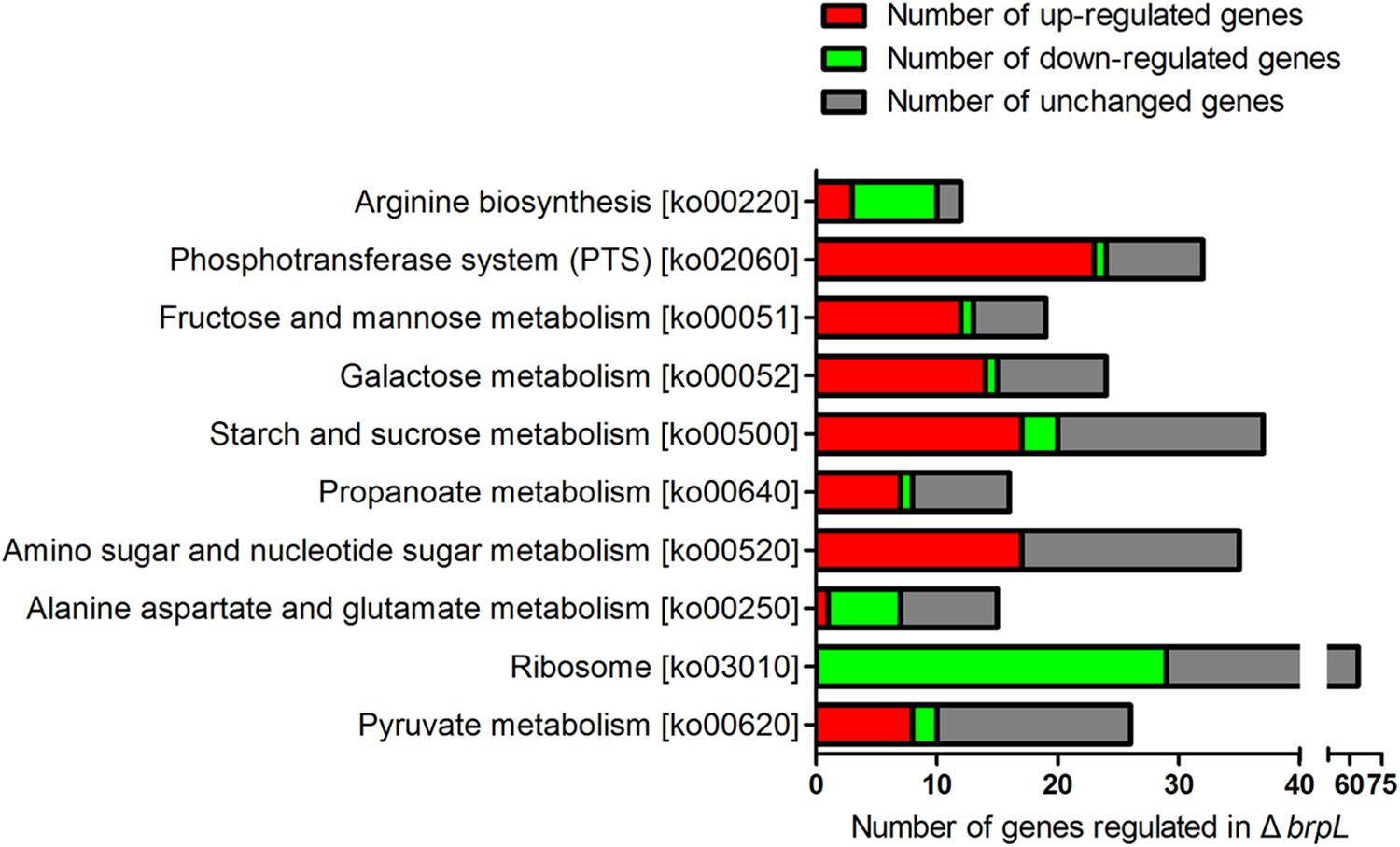

A Broad Range of Carbohydrate Metabolism Pathways Are Controlled by ΔbrpL

To further analyze the RNA-seq data of ΔbrpL, we created a Matlab script to count numbers of regulated genes in each pathway (Supplementary Script of Matlab). The pathway information was obtained from the KEGG database (Kanehisa et al., 2004). We listed the numbers of up- and down-regulated genes, total genes and the ratio of regulated genes/total genes in each pathway (Supplementary Datasheet 2). Pathways were ranked by the ratio of regulated genes/total genes from large to small and top 10 most influenced pathways were exhibited. The data illustrated that a broad range of carbohydrate metabolism pathways were impacted by the deletion of brpL, including fructose and mannose metabolism, galactose metabolism, starch and sucrose metabolism, amino sugar and nucleotide sugar metabolism, alanine, aspartate and glutamate metabolism and pyruvate metabolism (Figure 8). Most of genes involved in these pathways were upregulated except for genes in the alanine, aspartate and glutamate metabolism pathway (Figure 8), which implied that carbohydrate metabolism might be enhanced in ΔbrpL. Additionally, a large amount of phosphotransferase system (PTS) genes were up-regulated (Figure 8), indicating that the uptake of carbohydrate might be promoted in ΔbrpL (Kotrba et al., 2001). The increased uptake and metabolism of carbohydrate might elevate the intracellular concentration of carbon sources, which in turn would have supported polysaccharide production and biofilm formation. These results were consistent with the finding that two kinds of polysaccharide were over-producted in ΔbrpL (Figure 4).

FIGURE 8. Numbers of differential expressed genes involved in each pathway in ΔbrpL. The names of KEGG pathways and their relative ko numbers (originated from KEGG database) were listed in y-title of the figure. Differential expressed genes (fold change ≥ 1.5 or ≤0.667 and p-value ≤ 0.05) were classified into different pathways. The numbers of regulated genes were counted by RPAS script running in Matlab software.

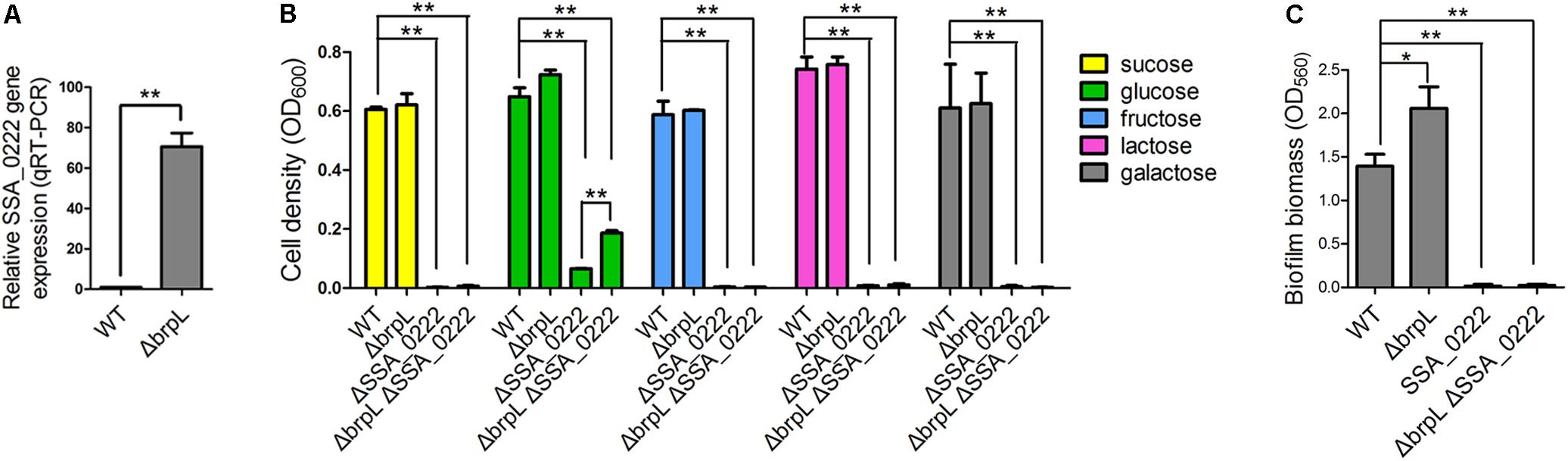

A PTS Gene SSA_0222 Is Essential for the Growth of S. sanguinis

RNA-seq data revealed that a gene cluster (SSA_0219, SSA_0220, SSA_0221, SSA_0222, and SSA_0224) showed high fold upregulation in ΔbrpL (fold change > 110 for all of the five genes) and relative downregulation in ΔciaR (fold change < 0.25 for all of the five genes) (Figure 7B, Supplementary Figure S8 and Supplementary Datasheet 1). The qRT-PCR results confirmed SSA_0222 was over-expressed in ΔbrpL (Figure 9A). Genome annotation predicts that SSA_0219, SSA_0220, SSA_0221, and SSA_0222 were PTS system mannose-specific transporter subunits, while the function of SSA_0224 was unknown (Supplementary Datasheet 1). Since PTS genes are related to the uptake of carbohydrate (Kotrba et al., 2001), we tested the growth of these PTS gene mutants in BM supplemented with five kinds of carbon sources: sucrose, glucose, fructose, lactose and galactose. The deletion of SSA_0219, SSA_0220, and SSA_0221 had no impact on cell growth or biofilm formation (data not shown). Surprisingly, the SSA_0222 mutant had only minimal growth in BM supplemented with glucose and failed to grow in all other media (Figure 9B). Although it remains unclear if SSA_0222 had a direct impact on carbohydrate uptake, under our experimental conditions, this gene was essential for the survival of S. sanguinis. The biofilm formation of ΔSSA_0222 was severely decreased which could have been caused by the growth deficiency of the bacteria (Figure 9C).

FIGURE 9. The effect of SSA_0222 on growth and biofilm formation. (A) The expression of SSA_0222 in WT and ΔbrpL was tested by qRT-PCR. The relative expression of SSA_0222 was shown. (B) Strains were cultured in BM supplemented with different kinds of carbohydrate for 24 h. Cell growth was monitored at 600 nm with a plate reader. (C) The 1-day biofilms of strains were quantified by CV staining. All of the data were relative to their WT controls. ∗P ≤ 0.05, ∗∗P ≤ 0.01, Student’s t-test. Means and standard deviations from triplicate experiments are shown.

As SSA_0222 was dramatically up-regulated in ΔbrpL, we proposed that SSA_0222 was involved in the influence of brpL biofilm formation control. To this end, a ΔbrpLΔSSA_0222 double gene deletion mutant was constructed. The mutant showed similar characteristics to a ΔSSA_0222 mutant in growth and biofilm formation (Figures 9B,C). Since the growth of ΔbrpLΔSSA_0222 was severely inhibited, it was uncertain whether SSA_0222 contributed to an increased biofilm formation in ΔbrpL. However, ΔbrpL grew faster than WT at log phase (Supplementary Figure S2), indicating that an over-expression of SSA_0222 might promote carbohydrate uptake and as a result supply more carbon source for the biofilm formation of ΔbrpL. Further studies are required to elucidate the precise function of SSA_0222 and its relationship with BrpL as these initial findings suggest importance in biofilm regulation.

It was interesting to observe that ΔbrpLΔSSA_0222 grew better than ΔSSA_0222 in BM supplemented with 1% glucose, indicating that the expression of other genes might be altered in ΔbrpL to promote the uptake and/or metabolism of glucose in ΔbrpL (Figure 9B). This result was consistent with the RNA-seq data that a broad range of genes related to carbohydrate metabolism and uptake were activated in ΔbrpL (Figure 8).

Discussion

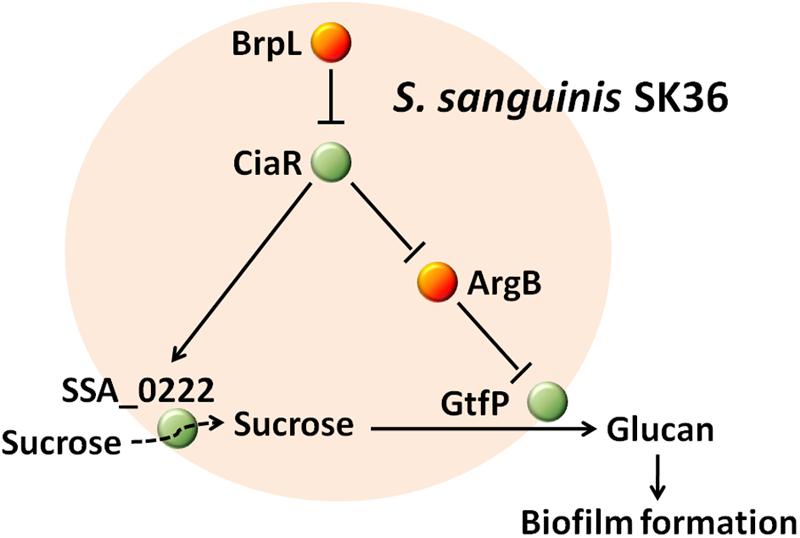

The effectiveness of S. sanguinis, as a pioneering organism, to form attachments to surfaces within the oral cavity, could be attributed to particular cell-surface attachment traits and/or particular initial biofilm properties (Socransky et al., 1977; Maeda et al., 2004). As S. sanguinis lays the foundations for biofilm that may lead to disease-contributing plaque formation, it is essential to identify and characterize biofilm related genes to aid in developing novel therapeutic agents against oral disease. In this study, we present coding sequence SSA_0427 as a new LuxR family transcription regulator that controls biofilm formation by modulating glucan production and may also function to increase sucrose uptake through SSA_0222 (Figure 10). The deletion of SSA_0427, which we have called brpL, resulted in a mutant with a higher tolerance to ampicillin exposure and better cell-surface attachment ability to prevent it from being washed away (Table 1 and Figure 1). These characteristics would both be beneficial for maintenance of S. sanguinis in oral cavity in the presence of sucrose as carbon source. Cell and glucan aggregation formed in the biofilm of ΔbrpL may be important factors leading to these phenotypes (Flemming and Wingender, 2010; Hobley et al., 2015). However, it is still not clear about whether or when the expression of brpL is decreased to improve the biofilm formation of S. sanguinis. To reduce the biofilm formation, further studies on what influences the activation of brpL expression need to be performed in future.

FIGURE 10. The mechanism by which BrpL modulates biofilm formation in Streptococcus sanguinis SK36. GtfP, a glucosyltransferase, is responsible for glucan production. SSA_0222, a component of a PTS, may play an important role in the uptake of sucrose and is essential for survival in BM supplemented with 1% sucrose. BrpL regulates the expression of gtfP and SSA_0222 through the inhibition of another biofilm-related regulator ciaR and as a result controls the biofilm formation of S. sanguinis SK36.

Notwithstanding, the current research on brpL helped us elucidate an interesting PTS gene SSA_0222 that is essential for the uptake of carbon sources and further confirm the mechanisms by which CiaR modulates biofilm formation. SSA_0222 and CiaR may be better targets to decrease biofilm formation of S. sanguinis.

Streptococcus sanguinis SK36 is non-motile and cells are not assembled by a proactive movement which raises the question of how the cells aggregate. A previous work demonstrated that localized cell death focuses mechanical forces during biofilm development (Asally et al., 2012). These forces promote the self-assembly of a wrinkle structure (Asally et al., 2012), which could explain the phenomenon of aggregation in S. sanguinis. However, it is certain that polysaccharide is an essential skeleton for bacteria to produce biofilms with a complex three-dimensional structure (Flemming and Wingender, 2010; Wang et al., 2013; Hobley et al., 2015). In S. sanguinis, the biofilm formed by ΔgtfP was very thin and flat, which perhaps may not contain enough glucan to support the manufacture of a complex structure (Supplementary Figure S6). In contrast, the biofilm of ΔbrpL might contain enough glucan to construct an aggregated structure. Additionally, the aggregation phenotype of ΔbrpL was reversed in the double deletion mutant of ΔbrpL/ΔgtfP (Figure 5B).

An interesting phenomenon observed was the presence of cavities in the center of some aggregations. As mentioned above, a similar phenomenon was also seen in P. aeruginosa (Ma et al., 2009). Previous works demonstrate that the formation of cell cavities is mediated by programmed cell death inside of biofilms in P. aeruginosa (Ma et al., 2009). Here, we also showed cavities existed in the biofilm in the layers below a cell aggregate in the biofilm of ΔbrpL (Figure 6A), which might be caused by programmed cell death. In S. sanguinis, SpxB-mediated H2O2 induces programmed cell death (Li et al., 2016). RNA-seq data showed that the spxB gene was over-expressed in ΔbrpL (Supplementary Datasheet 1), which might facilitate the accumulation of H2O2 and promote programmed cell death at the site of cavities.

Our previous work showed that ciaR affected biofilm formation through the arginine biosynthesis pathway (Zhu et al., 2017). The comparison of RNA-seq data from ΔbrpL and ΔciaR implied that ΔbrpL increased biofilm formation by stimulating the expression of ciaR. We discovered that a PTS gene, SSA_0222, was controlled by both brpL and ciaR and was essential for the survival of S. sanguinis under our experimental conditions. However, although the expression of SSA_0222 was repressed in ΔciaR, the ΔciaR mutant was not defective in growth in BM supplemented with 1% sucrose (Zhu et al., 2017). It is still not clear whether the down-regulation of SSA_0222 contributes to reduced biofilm formation ability in ΔciaR. Future efforts need to be directed into further defining the role and functionality of SSA_0222.

Materials and Methods

Bacterial Strains, Growth and Antibiotics

Strains used in this study are listed in Supplementary Table S1. Unless otherwise stated, strains were grown in brain heart infusion broth (BHI; Difco Inc., Detroit, MI, United States) media overnight and then diluted 100-fold into biofilm media (BM) supplemented with 1% sucrose and incubated under microaerobic conditions (6% O2, 7.2% CO2, 7.2% H2, and 79.6% N2) at 37°C using an Anoxomat® system (Spiral Biotech, Norwood, MA, United States). BM supplemented with 1% sucrose was used for the growth of static biofilms and the measurement of bacterial growth (Loo et al., 2000). Kanamycin was added to a concentration of 500 μg/ml for mutant cultures. The growth of PTS mutants was tested in BM supplemented with different kinds of carbohydrate, including 1% sucrose, 1% glucose, 1% fructose, 1% lactose, and 1% galactose. OD600 was measured after incubation for 24 h under microaerobic conditions at 37°C.

Mutant Construction

We have constructed ΔgtfP, ΔciaR, and ΔSSA_0222 single gene mutants in our previous work (Ge and Xu, 2012). Based on these mutants, the brpL gene was deleted to construct ΔbrpLΔgtfP,ΔbrpLΔciaR, and ΔbrpLΔSSA_0222 double mutants. For double mutant construction, three sets of primers were used to independently PCR amplify the 1-kb sequence of the upstream fragment of target gene, the downstream fragment of target gene and the erm gene for erythromycin resistance. Primers listed in Supplementary Table S2. The three fragments were combined by a second round of PCR. The final recombinant PCR product was transformed into S. sanguinis SK36 single mutants. Double mutants were selected by erythromycin resistance and confirmed by PCR analysis. BHI medium was used in all processes of mutant construction.

CV Staining Assay

Overnight cultures were diluted 1:100 into BM supplemented with 1% sucrose in a 96-well microtiter plate (Falcon 3911). After incubation at 37°C for 24 h under microaerobic conditions, the supernatant was gently removed by pipetting. Biofilms were washed once with distilled water and stained by the addition of 0.4% CV for 30 min at room temperature. CV was then gently removed by pipetting. Biofilms were washed twice with distilled water, solubilized in 30% acetic acid and measured at A560 as described previously (Ma et al., 2006).

Biofilm Attachment Assay

Biofilms were tested by a protocol similar to the CV staining assay. The differences were: CV and water were injected into 96 wells at the CV staining step and washing step, respectively, by using a Caliper Sciclone G3 liquid handling robot (PerkinElmer, United States) with different speeds of injection.

Static Biofilm Assay

Static biofilms were grown in 4-chambered glass coverslip wells (Chambered Coverglass, Thermo Scientific) in BM supplemented with 1% sucrose at 37°C under micro-aerobic conditions for 24 h. The supernatant was discarded and biofilms were washed with PBS. For testing biomass, biofilms were stained with a live/dead staining kit (Invitrogen, United States) in darkness for 10 min. STYO9 (green signal) stained live cells and PI (red signal) stained dead cells and eDNA. Two methods were used to stain cells and polysaccharide. In Figure 4A, cells (red signal) were marked with Hexidium iodide (HI) (Invitrogen, United States) at 4.7 μM and polysaccharide containing α-(1, 3) or α-(1, 6) linked mannosyl units (green signal) was stained by 100 μg/mL of Hippeastrum hybrid lectin (HHA)-FITC (EY Labs, United States) (Ma et al., 2009). Biofilms were stained in darkness for 2 h. In Figure 4B, biofilms were cultured in BM supplemented with 1% sucrose and 10 μM of Alexa Fluor 647-labeled dextran conjugate (Invitrogen, United States) for 24 h in darkness. The fluorescently labeled dextran was used as an acceptor and was incorporated into newly formed glucan by Gtfs (Koo et al., 2010). Then the supernatant was discarded and biofilms were stained by 5 μM of SYTO 9 (Invitrogen, United States) for 10 min. The fluorescent images were acquired with a Zeiss LSM710 CLSM (Zeiss, Germany) and quantified by COMSTAT in Matlab (Heydorn et al., 2000). Three images of each sample were quantified to calculate the means and standard deviations.

Growth Curve Measurement

Strains were cultured in BM supplemented with 1% sucrose in 96-well plates with continuous shaking and growth was monitored every 30 min at 600 nm with a Synergy H1 Hybrid Reader (BioTek, United States). The microaerobic conditions (6% O2, 6% CO2) were maintained by injection of CO2 and N2 to maintain CO2/O2 set concentrations (BioTek, United States). Three replicates were examined to calculate the means and standard deviations.

Biofilms Treated by DNase I

Biofilms were grown in BM supplemented with 1% sucrose for 24 h and then supernatant was discarded by pipetting. PBS buffer or PBS supplemented with 100 U/mL of DNase I was added to the wells. Biofilms were treated by DNase I for 2 h under microaerobic condition at 37°C and then biomass was measured using CV staining. Two kinds of DNase I (QIAGEN, catalog number: 79254; Thermo Scientific, catalog number: FEREN0525) were used in this assay and results were the same.

Scanning Electronic Microscopy (SEM) Analysis of Biofilm

Biofilms were grown as previously described, on the surface of cover glasses (Fisher Scientific, catalog number: 083110-9). The 1-day biofilms were washed twice with PBS in Petri dishes and fixed with 2% glutaraldehyde overnight. Following dehydration through a graded series of ethanol, the cover glasses were air dried and sputter coated with gold. Samples were then scoped by a SEM machine (Zeiss EVO 50 XVP, Jena, Germany).

Maximum Tolerance Concentration of Strains to Ampicillin

Biofilms were grown in BM for 24 h and then supernatant discarded by pipetting. Biofilms were treated with different concentrations of ampicillin for 2 h in microaerobic condition at 37°C. After ampicillin treatment, supernatant was discarded and cells were resuspended in PBS by pipetting. Bacteria cultures were centrifuged, resuspended in PBS and diluted 100-fold into fresh BHI in 96-well plates. After overnight culturing, if cells could survive after ampicillin treatment, they would grow in fresh BHI and let medium turbid. Failure to grow would result is a completely clear media. Three replicates were examined to get the results.

The tolerance of cells to ampicillin in planktonic form was similar to biofilm cell tolerance. Cells were cultured overnight in BHI. OD600 of planktonic cells was tested by a Synergy H1 Hybrid Reader (BioTek, United States). As the biofilm biomass of ΔbrpL was nearly two times higher than WT, we collected planktonic ΔbrpL cells of biomass two times more than that of WT. These planktonic cells were treated with ampicillin using the same processes as mentioned above.

The Measurement of WIG and WSG

Water-insoluble glucan and WSG was measured as previously described (Liu et al., 2017; Zhu et al., 2017). Biofilms were grown in BM for 24 h in 24-well plates. The supernatant was then removed and biofilms were resuspended in 1 mL of distilled water. One-half mL of cell suspension was prepared for the determination of total protein concentration. Another 500 μL of bacterial suspension was centrifuged. The supernatant was prepared for the measurement of WSG. The sediment was dissolved in the same volume of 1 N NaOH for 3 h and centrifuged. The supernatants were precipitated by three volumes of isopropanol for 1 day at -20°C. The precipitates obtained by centrifugation were then air dried and dissolved in 250 μL of ddH2O for WSG or 1 N NaOH for WIG. The amount of glucans in each fraction was quantified by the phenol-sulfuric acid method as previously described (Decker et al., 2011). Glucose was used as a reference carbohydrate to generate a standard curve. The concentrations of WIG and WSG were normalized by total protein concentration in the biofilm. Three replicates were examined to calculate the means and standard deviations.

The Measurement of Protein Concentration

Cells were harvested and resuspended in lysis buffer (Tris pH7.4 50 mM, NaCl 150 mM, glycerol 10%, NP-40 1%, SDS 0.1%). Cell suspensions were incubated on ice for 30 min and then lysed by mechanical disruption using FastPrep lysing matrix B (Qbiogene, Irvine, CA, United States). The protein concentration of cell lysate was measured by following the standard protocol of PierceTM BCA Protein Assay Kit (Thermo Scientific). Four replicates were analyzed to calculate the means and standard deviations.

qRT-PCR Assay

The WT and mutants were cultured in BHI overnight and then diluted into fresh BHI and grown for 3 h in microaerobic conditions at 37°C. Samples were collected, treated with RNA protect bacteria reagent (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, United States) for 5 min to stabilize RNA and stored at -80°C. Cells were lysed by mechanical disruption using FastPrep lysing matrix B (Qbiogene, Irvine, CA, United States). Total RNA was treated with DNase I (Qiagen) and prepared using RNA easy mini kits (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. RNA extraction was performed as described below for the RNA-seq assay. Reverse transcription followed the standard procedure provided with the SuperScriptTM III Reverse Transcriptase Kit (Qiagen). The cDNA was used as the template, combined with 2X SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Qiagen) and the q-PCR primers were shown in Supplementary Table S2. Gene expression in mutants is relative to that in WT. The housekeeping gene gyrA was used as a normalization control (Ge et al., 2016). Three replicates were analyzed to calculate the means and standard deviations.

RNA-seq and Data Analysis

The WT and ΔbrpL were cultured in BHI medium overnight and then diluted into fresh BHI medium. After incubation in microaerobic conditions at 37°C for 3 h, samples were collected, treated with RNA protect bacteria reagent (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, United States) for 5 min to stabilize RNA and stored at -80°C. Cells were lysed by mechanical disruption using FastPrep lysing matrix B (Qbiogene, Irvine, CA, United States). Total RNA was treated with DNase I (Qiagen) and prepared using RNA easy mini kits (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Ribo-Zero Magnetic Kit for Bacteria (Illumina) was used to deplete ribosomal RNA from 2 μg of total RNA. NEBNext Ultra Directional RNA Library Prep Kit for Illumina (New England BioLabs) was used for the following RNA-seq library preparation according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Library sequencing was performed by the Nucleic Acids Research Facilities at Virginia Commonwealth University using an Illumina HiSeq2000 instrument. The raw RNA sequencing data are available in the NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO)2 under the accession number: GSE110307. Reads obtained from RNA-seq were aligned against the S. sanguinis SK36 genome using EDGE-pro (Magoc et al., 2013). Differential gene expression was analyzed by DESeq2 (Love et al., 2014). P-values shown in RNA-seq data are adjusted p-values generated by DESeq2. Four replicates were performed for analysis. The RNA-seq data of ΔciaR was reanalyzed by EDGE-pro and DESeq2 (Magoc et al., 2013; Love et al., 2014).

Based on the knowledge of KEGG database (Kanehisa et al., 2004), the regulated genes (fold change ≥ 1.5 or ≤0.667 and p-value ≤ 0.05) in ΔbrpL were classified into different function groups. We wrote a script, named RPAS, in Matlab software to count the number of genes involved in each group (Supplementary Script of Matlab).

Statistical Analysis

All data were obtained from at least three biological replicates. Student’s t-test was applied to analyze data on biofilm assay, COMSTAT results, qRT-PCR, cell growth and the production of WIG and WSG.

Data Availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Author Contributions

BZ and PX conceived and designed this study. BZ carried out all the experiments with the assistance of LS and LM. BZ, XK, and PX analyzed the data and wrote this manuscript. All authors reviewed and discussed the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants R01DE023078 and R01DE018138 (PX).

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We are thankful to Dr. Xiuchun Ge, Victoria Stone, and Fadi El-Rami for previously constructing and maintaining the S. sanguinis mutant library. We thank Dr. Vladimir Lee at Virginia Commonwealth University for helping us with the biofilm attachment assay.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmicb.2018.01154/full#supplementary-material

Footnotes

References

Asally, M., Kittisopikul, M., Rue, P., Du, Y., Hu, Z., Cagatay, T., et al. (2012). Localized cell death focuses mechanical forces during 3D patterning in a biofilm. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109, 18891–18896. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1212429109

Bergenfelz, C., and Hakansson, A. P. (2017). Streptococcus pneumoniae otitis media pathogenesis and how it informs our understanding of vaccine strategies. Curr. Otorhinolaryngol. Rep. 5, 115–124. doi: 10.1007/s40136-017-0152-6

Bor, D. H., Woolhandler, S., Nardin, R., Brusch, J., and Himmelstein, D. U. (2013). Infective endocarditis in the U.S., 1998-2009: a nationwide study. PLoS One 8:e60033. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0060033

Brouwer, S., Barnett, T. C., Rivera-Hernandez, T., Rohde, M., and Walker, M. J. (2016). Streptococcus pyogenes adhesion and colonization. FEBS Lett. 590, 3739–3757. doi: 10.1002/1873-3468.12254

Cahill, T. J., and Prendergast, B. D. (2016). Infective endocarditis. Lancet 387, 882–893. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(15)00067-7

Castillo Pedraza, M. C., Novais, T. F., Faustoferri, R. C., and Quivey, R. G. Jr. (2017). Extracellular DNA and lipoteichoic acids interact with exopolysaccharides in the extracellular matrix of Streptococcus mutans biofilms. Biofouling 33, 722–740. doi: 10.1080/08927014.2017.1361412

Clark, W. B., and Gibbons, R. J. (1977). Influence of salivary components and extracellular polysaccharide synthesis from sucrose on the attachment of Streptococcus mutans 6715 to hydroxyapatite surfaces. Infect. Immun. 18, 514–523.

Crump, K. E., Bainbridge, B., Brusko, S., Turner, L. S., Ge, X., Stone, V., et al. (2014). The relationship of the lipoprotein SsaB, manganese and superoxide dismutase in Streptococcus sanguinis virulence for endocarditis. Mol. Microbiol. 92, 1243–1259. doi: 10.1111/mmi.12625

Davies, D. (2003). Understanding biofilm resistance to antibacterial agents. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2, 114–122. doi: 10.1038/nrd1008

Decker, E. M., Dietrich, I., Klein, C., and von Ohle, C. (2011). Dynamic production of soluble extracellular polysaccharides by Streptococcus mutans. Int. J. Dent. 2011:435830. doi: 10.1155/2011/435830

Duval, X., and Leport, C. (2008). Prophylaxis of infective endocarditis: current tendencies, continuing controversies. Lancet Infect. Dis. 8, 225–232. doi: 10.1016/s1473-3099(08)70064-1

Flemming, H. C., and Wingender, J. (2010). The biofilm matrix. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 8, 623–633. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2415

Francavilla, R., Ercolini, D., Piccolo, M., Vannini, L., Siragusa, S., De Filippis, F., et al. (2014). Salivary microbiota and metabolome associated with celiac disease. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 80, 3416–3425. doi: 10.1128/aem.00362-14

Ge, X., Shi, X., Shi, L., Liu, J., Stone, V., Kong, F., et al. (2016). Involvement of NADH oxidase in biofilm formation in Streptococcus sanguinis. PLoS One 11:e0151142. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0151142

Ge, X., and Xu, P. (2012). Genome-wide gene deletions in Streptococcus sanguinis by high throughput PCR. J. Vis. Exp. 69:4356. doi: 10.3791/4356

Gross, E. L., Beall, C. J., Kutsch, S. R., Firestone, N. D., Leys, E. J., and Griffen, A. L. (2012). Beyond Streptococcus mutans: dental caries onset linked to multiple species by 16S rRNA community analysis. PLoS One 7:e47722. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0047722

Heydorn, A., Nielsen, A. T., Hentzer, M., Sternberg, C., Givskov, M., Ersboll, B. K., et al. (2000). Quantification of biofilm structures by the novel computer program COMSTAT. Microbiology 146(Pt 10), 2395–2407. doi: 10.1099/00221287-146-10-2395

Hobley, L., Harkins, C., MacPhee, C. E., and Stanley-Wall, N. R. (2015). Giving structure to the biofilm matrix: an overview of individual strategies and emerging common themes. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 39, 649–669. doi: 10.1093/femsre/fuv015

Holland, T. L., Baddour, L. M., Bayer, A. S., Hoen, B., Miro, J. M., and Fowler, V. G. Jr. (2016). Infective endocarditis. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2:16059. doi: 10.1038/nrdp.2016.59

Kanehisa, M., Goto, S., Kawashima, S., Okuno, Y., and Hattori, M. (2004). The KEGG resource for deciphering the genome. Nucleic Acids Res. 32, D277–D280. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh063

Koo, H., Xiao, J., Klein, M. I., and Jeon, J. G. (2010). Exopolysaccharides produced by Streptococcus mutans glucosyltransferases modulate the establishment of microcolonies within multispecies biofilms. J. Bacteriol. 192, 3024–3032. doi: 10.1128/jb.01649-09

Kotrba, P., Inui, M., and Yukawa, H. (2001). Bacterial phosphotransferase system (PTS) in carbohydrate uptake and control of carbon metabolism. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 92, 502–517. doi: 10.1016/S1389-1723(01)80308-X

Kreth, J., Giacaman, R. A., Raghavan, R., and Merritt, J. (2017). The road less traveled - defining molecular commensalism with Streptococcus sanguinis. Mol. Oral Microbiol. 32, 181–196. doi: 10.1111/omi.12170

Kreth, J., Merritt, J., Shi, W., and Qi, F. (2005). Competition and coexistence between Streptococcus mutans and Streptococcus sanguinis in the dental biofilm. J. Bacteriol. 187, 7193–7203. doi: 10.1128/jb.187.21.7193-7203.2005

Letunic, I., Copley, R. R., Pils, B., Pinkert, S., Schultz, J., and Bork, P. (2006). SMART 5: domains in the context of genomes and networks. Nucleic Acids Res. 34, D257–D260. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkj079

Li, T., Zhai, S., Xu, M., Shang, M., Gao, Y., Liu, G., et al. (2016). SpxB-mediated H2O2 induces programmed cell death in Streptococcus sanguinis. J. Basic Microbiol. 56, 741–752. doi: 10.1002/jobm.201500617

Liu, J., Stone, V. N., Ge, X., Tang, M., Elrami, F., and Xu, P. (2017). TetR family regulator brpT modulates biofilm formation in Streptococcus sanguinis. PLoS One 12:e0169301. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0169301

Loo, C. Y., Corliss, D. A., and Ganeshkumar, N. (2000). Streptococcus gordonii biofilm formation: identification of genes that code for biofilm phenotypes. J. Bacteriol. 182, 1374–1382. doi: 10.1128/JB.182.5.1374-1382.2000

Love, M. I., Huber, W., and Anders, S. (2014). Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 15:550. doi: 10.1186/s13059-014-0550-8

Ma, L., Conover, M., Lu, H., Parsek, M. R., Bayles, K., and Wozniak, D. J. (2009). Assembly and development of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm matrix. PLoS Pathog. 5:e1000354. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000354

Ma, L., Jackson, K. D., Landry, R. M., Parsek, M. R., and Wozniak, D. J. (2006). Analysis of Pseudomonas aeruginosa conditional psl variants reveals roles for the psl polysaccharide in adhesion and maintaining biofilm structure postattachment. J. Bacteriol. 188, 8213–8221. doi: 10.1128/jb.01202-06

Maeda, K., Nagata, H., Nonaka, A., Kataoka, K., Tanaka, M., and Shizukuishi, S. (2004). Oral streptococcal glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase mediates interaction with Porphyromonas gingivalis fimbriae. Microbes Infect. 6, 1163–1170. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2004.06.005

Magoc, T., Wood, D., and Salzberg, S. L. (2013). EDGE-pro: estimated degree of gene expression in prokaryotic genomes. Evol. Bioinform. Online 9, 127–136. doi: 10.4137/ebo.s11250

McNab, R., and Jenkinson, H. (1992). Aggregation-deficient mutants of Streptococcus gordonii Channon altered in production of cell-surface polysaccharide and proteins. Microb. Ecol. Health Dis. 5, 277–289. doi: 10.3109/08910609209141549

Rölla, G., Scheie, A. A., and Ciardi, J. E. (1985). Role of sucrose in plaque formation. Eur. J. Oral Sci. 93, 105–111. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0722.1985.tb01317.x

Seoudi, N., Bergmeier, L. A., Drobniewski, F., Paster, B., and Fortune, F. (2015). The oral mucosal and salivary microbial community of Behcet’s syndrome and recurrent aphthous stomatitis. J. Oral Microbiol. 7, 27150. doi: 10.3402/jom.v7.27150

Socransky, S. S., Manganiello, A. D., Propas, D., Oram, V., and van Houte, J. (1977). Bacteriological studies of developing supragingival dental plaque. J. Periodontal Res. 12, 90–106. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.1977.tb00112.x

Stoodley, P., Sauer, K., Davies, D. G., and Costerton, J. W. (2002). Biofilms as complex differentiated communities. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 56, 187–209. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.56.012302.160705

Wang, S., Parsek, M. R., Wozniak, D. J., and Ma, L. Z. (2013). A spider web strategy of type IV pili-mediated migration to build a fibre-like Psl polysaccharide matrix in Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms. Environ. Microbiol. 15, 2238–2253. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.12095

Whitchurch, C. B., Tolker-Nielsen, T., Ragas, P. C., and Mattick, J. S. (2002). Extracellular DNA required for bacterial biofilm formation. Science 295:1487. doi: 10.1126/science.295.5559.1487

Xu, P., Alves, J. M., Kitten, T., Brown, A., Chen, Z., Ozaki, L. S., et al. (2007). Genome of the opportunistic pathogen Streptococcus sanguinis. J. Bacteriol. 189, 3166–3175. doi: 10.1128/jb.01808-06

Xu, P., Ge, X., Chen, L., Wang, X., Dou, Y., Xu, J. Z., et al. (2011). Genome-wide essential gene identification in Streptococcus sanguinis. Sci. Rep. 1:125. doi: 10.1038/srep00125

Yoshida, Y., Konno, H., Nagano, K., Abiko, Y., Nakamura, Y., Tanaka, Y., et al. (2014). The influence of a glucosyltransferase, encoded by gtfP, on biofilm formation by Streptococcus sanguinis in a dual-species model. APMIS 122, 951–960. doi: 10.1111/apm.12238

Zähner, D., Kaminski, K., van der Linden, M., Mascher, T., Merai, M., and Hakenbeck, R. (2002). The ciaR/ciaH regulatory network of Streptococcus pneumoniae. J. Mol. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 4, 211–216.

Zhu, B., Ge, X., Stone, V., Kong, X., El-Rami, F., Liu, Y., et al. (2017). ciaR impacts biofilm formation by regulating an arginine biosynthesis pathway in Streptococcus sanguinis SK36. Sci. Rep. 7:17183. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-17383-1

Keywords: Streptococcus, biofilm, transcription factor, glucan, aggregation, CiaR, carbohydrate metabolism

Citation: Zhu B, Song L, Kong X, Macleod LC and Xu P (2018) A Novel Regulator Modulates Glucan Production, Cell Aggregation and Biofilm Formation in Streptococcus sanguinis SK36. Front. Microbiol. 9:1154. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.01154

Received: 13 February 2018; Accepted: 14 May 2018;

Published: 29 May 2018.

Edited by:

Weiwen Zhang, Tianjin University, ChinaReviewed by:

Jens Kreth, Oregon Health & Science University, United StatesNick Stephen Jakubovics, Newcastle University, United Kingdom

Copyright © 2018 Zhu, Song, Kong, Macleod and Xu. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Ping Xu, pxu@vcu.edu

Bin Zhu

Bin Zhu Lei Song1

Lei Song1 Lorna C. Macleod

Lorna C. Macleod Ping Xu

Ping Xu