- School of Life Sciences, University of Lincoln, Lincoln, United Kingdom

Vibrio parahaemolyticus is an environmental organism normally found in subtropical estuarine environments which can cause seafood-related human infections. Clinical disease is associated with diagnostic presence of tdh and/or trh virulence genes and identification of these genes in our preliminary isolates from retail shellfish prompted a year-long surveillance of isolates from a temperate estuary in the north of England. The microbial and environmental analysis of 117 samples of mussels, seawater or sediment showed the presence of V. parahaemolyticus from mussels (100%) at all time-points throughout the year including the colder months although they were only recovered from 94.9% of seawater and 92.3% of sediment samples. Throughout the surveillance, 96 isolates were subjected to specific PCR for virulence genes and none tested positive for either. The common understanding that consuming poorly cooked mussels only represents a risk of infection during summer vacations therefore is challenged. Further investigations with V. parahaemolyticus using RAPD-PCR cluster analysis showed a genetically diverse population. There was no distinct clustering for “environmental” or “clinical” reference strains although a wide variability and heterogeneity agreed with other reports. Continued surveillance of isolates to allay public health risks are justified since geographical distribution and composition of V. parahaemolyticus varies with Future Ocean warming and the potential of environmental strains to acquire virulence genes from pathogenic isolates. The prospects for intervention by phage-mediated biocontrol to reduce or eradicate V. parahaemolyticus in mussels was also investigated. Bacteriophages isolated from enriched samples collected from the river Humber were assessed for their ability to inhibit the growth of V. parahaemolyticus strains in-vitro and in-vivo (with live mussels). V. parahaemolyticus were significantly reduced in-vitro, by an average of 1 log−2 log units and in-vivo, significant reduction of the organisms in mussels occurred in three replicate experimental tank set ups with a “phage cocktail” containing 12 different phages. Our perspective biocontrol study suggests that a cocktail of specific phages targeted against strains of V. parahaemolyticus provides good evidence in an experimental setting of the valuable potential of phage as a decontamination agent in natural or industrial mussel processing (343w).

Introduction

V. parahaemolyticus is a Gram-negative bacterium commonly found in marine and estuarine coastal environments (Feldhusen, 2000; Ceccarelli et al., 2013; Letchumanan et al., 2014; Malcolm et al., 2015; Raghunath, 2015) and can cause shellfish-related gastroenteritis (Hazen et al., 2015; Raghunath, 2015), wound infection and septicaemia in sub-tropical environments (Daniels et al., 2000; Zhang and Orth, 2013). Gastrointestinal infections in humans cause vomiting, diarrhea, abdominal pain, nausea, fever, chills with an onset time of 2–48 h after consumption. This organism is frequently isolated from a range of raw seafoods, such as crab, fish, lobster, oyster, shellfish, and shrimp (Wang et al., 2015; Letchumanan et al., 2016) and mussels. V. parahaemolyticus multiplies in the human intestinal tract and produces one or more toxins that contribute to the symptoms. Clinical infections are reported from diverse serovars, but since not all isolates are pathogenic to humans, the ubiquitous distribution of V. parahaemolyticus in the environment poses a challenging problem for predictive diagnosis and control. To monitor the prevalence of V. parahaemolyticus from environmental sources, organisms need to be efficiently identified and differentiated from other Gram-negative bacteria that might be present. Traditional isolation techniques consisting of Thiosulphate Citrate Bile Salt Sucrose (TCBS) agar has caused difficulties distinguishing V. parahaemolyticus from other vibrio species in environmental samples. Although this traditional selective media is based on sugar fermentation, it is still widely used for the isolation of Vibrio species from natural and clinical environments (Blanco-Abad et al., 2009) but a chromogenic agar containing substrates for β-galactosidase has been recognized as an improvement for the detection of V. parahaemolyticus in marine samples. In addition, V. parahaemolyticus can be identified by the detection of haemolysin genes—all strains display a species-specific haemolysin coded by a thermolabile (tlh) gene. In clinical cases, two well-described haemolysins, thermostable direct haemolysin genes (tdh) and tdh—related haemolysin (trh) are present (Honda and Iida, 1993; Nishibuchi and Kaper, 1995; Bej et al., 1999; Harth et al., 2009; Johnson et al., 2012; Zhang and Orth, 2013; Letchumanan et al., 2014; Raghunath, 2015). The detection of these gene sequences by PCR amplification targeted by specific oligonucleotide primers are the most important predictive measure of the pathogenicity of V. parahaemolyticus strains for human illness (Johnson et al., 2012). Reliable molecular methods have been developed for the sub-species typing of V. parahaemolyticus (Wong and Lin, 2001; Khan et al., 2002; Bilung et al., 2005) and RAPD-PCR analysis has commonly been used for the study of genetic relationships in Vibrio species (Tada et al., 1992; Bilung et al., 2005; Gonzalez-Escalona et al., 2005; Ellingsen et al., 2008). The method generates “fingerprints” that can be used to compare bacteria both at the inter-species and intra-species level with high discriminating power and (a) does not require previous knowledge of sequences in the DNA of the isolate under study (b) produces a DNA pattern that allows comparison of many loci simultaneously, (c) simple and relatively low cost and requires only nanogram amounts of template DNA. Previous studies employing RAPD-PCR have analyzed Vibrio communities isolated from many parts of the world (Sudheesh et al., 2002; Domingue et al., 2003; Gonzalez-Escalona et al., 2005) although only Ellingsen et al. (2008) documents RAPD-PCR analysis of V. parahaemolyticus environmental isolates in northern Europe.

The distribution and composition of potentially pathogenic V. parahaemolyticus in the environment requires careful monitoring as ocean warming may well change the geographical distribution in the coastal estuaries (Baker-Austin et al., 2013). With changes in patterns of global warming, human infections with V. parahaemolyticus traditionally confined to warm subtropical geographical areas may represent increased risks developing in temperate regions (McLaughlin et al., 2005). Simple and clear methodology is required to monitor temperate regions for isolates acquiring virulence genes which would represent increased risks for the community. The control and management of many pathogens faces ever increasing challenges for healthcare and food environments due to the increasing rates of antibiotic resistance. The antimicrobial susceptibility of V. parahaemolyticus isolates in particular has changed during the past few decades with diminished sensitivity to antimicrobials (Daramola et al., 2009). Public and professional concerns about the reduction of treatment options in healthcare have triggered global efforts to find novel alternatives to antibiotics, such as bacteriophages (Caplin, 2009). Although bacteriophage therapeutics have been recognized and used for many years in the early to mid-twentieth century their popularity declined rapidly in the West with the introduction of antibiotics. In Poland, between 1983 and 1987, Slopek et al. published a series of research articles on the effectiveness of phages against human infections caused by several bacterial pathogens, including multidrug-resistant mutants, (Slopek et al., 1983a,b, 1984, 1985a,b,c, 1987). Additional studies in Tbilisi, Georgia during 1963 and 1964 (Babalova et al., 1968) reported strong evidence of the effectiveness of phages on Shigella in children having gastrointestinal disorders. More recently there has been a reawakening of interest in “phage therapy” for both human and animal applications (Parisien et al., 2008) revealing that “phage therapy” is effective in clinical situations and virtually free of serious complications (Fortuna et al., 2008). The potential to treat infections in food livestock (Atterbury et al., 2007; Johnson et al., 2008), plants and aquaculture (McIntyre et al., 2007) has been demonstrated at least at a research level with good examples in luminous vibriosis caused by V. harvey in poultry (Vinod et al., 2005), and Aeromonas hydrophila in fish (Wu et al., 1981). Phage interventions are particularly attractive as a potentially useful strategy for the decontamination of live animals during the processing or harvesting stages of the product since phages are considered a GRAS product and have been approved by the FDA (Bren, 2007) and unlike antibiotics they appear not to demonstrate any known negative pharmacological effects (Parasion et al., 2014). More robust control of V. parahaemolyticus by bacteriophage as an intervention could therefore be useful in the harvesting of mussels and oysters from polluted beds in aquaculture. Bacteriophage strategies for bacterial pathogen decontamination have the advantages of being self-perpetuating, highly discriminatory, safe, natural, and cost-effective. Some of the drawbacks with their use is that there is theoretical potential for the transduction of undesirable characteristics from one bacterial strain to another. Although the significance of transduced resistance is yet to be determined the limited host range and potential emergence of phage resistant bacterial mutants may or may not be important in real life situations (Wilton, 2014).

In this study, bacteriophages specific to V. parahaemolyticus from estuarine water, sediments, and mussels will be identified, their host range and their ability to reduce genetically diverse V. parahaemolyticus isolates tested in vitro. The effects of an experimental cocktail of bacteriophage on V. parahaemolyticus in vivo in harvested mussels in the laboratory will be investigated.

Materials and Methods

Retail Supply

Raw shellfish samples (oysters, whelks) for our preliminary study were purchased from a local market that sources shellfish products from Grimsby, a large fishing town in Lincolnshire situated on the south bank of the Humber estuary.

Sampling Site

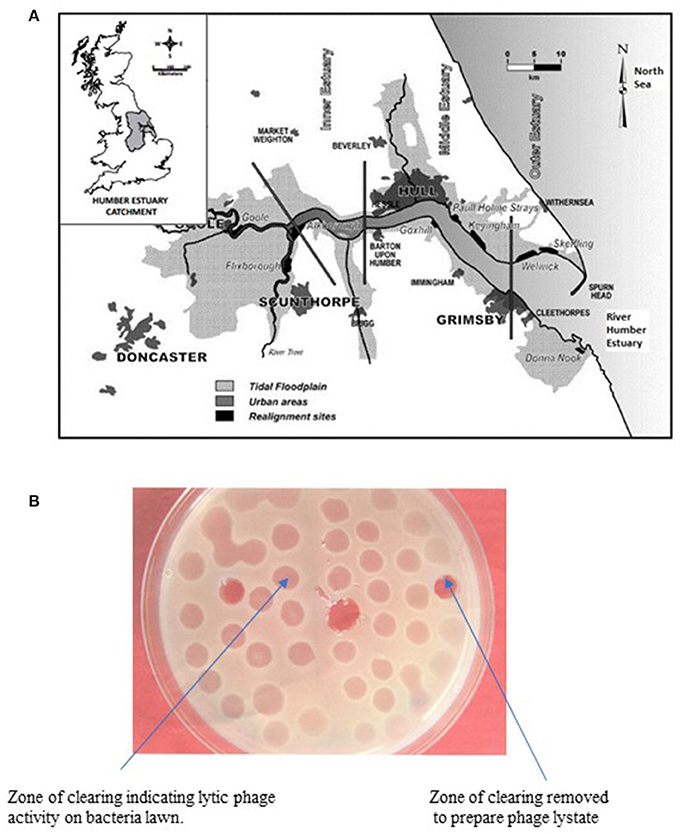

The surveillance study was conducted in Grimsby (Cleethorpes an adjacent resort) on the East coast of England (Figure 1A) situated at the mouth of the Humber estuary on the North Sea. The Humber estuary is one of the largest estuarine sites in Britain at ~9.5 km from “Spurn Point” which is its recognized entrance and 6.5 km wide at its mouth (GPS coordinates; Latitude: 53° 33′ 23.99″ N; Longitude: 0° 01′ 21.60″ E). Grimsby has one of the most important fish docks in Europe and there are over 70 shellfish harvesting point along the River Humber and more than 6 seaside recreation resorts.

Figure 1. (A) Map of the East Coast Region of England showing sampling site (Cleethorpes) along the River Humber. (B) Representative agar plate showing lytic activity of bacteriophage on lawn of host V. parahaemolyticus.

Sample Collection

For the isolation of V. parahaemolyticus, a total of 117 environmental samples were collected over 39 weeks between September and August and analyzed. Samples collected included shellfish (blue mussels; Mytilus edulis) (n = 39), seawater (n = 39), and sediment (n = 39). For each month between the study period (with exception of the month of June), samples were collected at least twice a month and up to 4 and 5 times per month when this was possible. Samples were collected around noon time when there was low tide. Collection of mussels was achieved at low tide by hand pulling mussels from natural clusters formed on the pillars of the pier, collected samples were then placed directly in a sterile polyethylene bag. Surface water samples were collected directly into a sterile plastic container while surface sediment samples were scooped using a sterile glass container and placed in another sterile glass jar. All samples were transported to the laboratory on ice in a portable insulated box. Samples were analyzed between 4 and 6 h of sample collection.

Environmental Parameters

During collection of samples, temperature and salinity were measured at the sampling site. Temperature (seawater and sediment) and salinity were measured using a portable digital thermometer and a portable calibrated WPA cm35 conductivity meter OHMS-1 (μmhos/cm) respectively.

Culture Media

Chromogenic vibrio (CV) agar (CHROMagar Co., France) and Thiosulphate Citrate Bile Salts Sucrose (TCBS) agar (Fluka, BioChemika, Switzerland) were used for the isolation of V. parahaemolyticus [formula: Agar: 15 g/l; Peptone: 8 g/l; Yeast extract: 8 g/l; Salts: 51.4 g/l; Chromogenic mix: 0.3 g/l; Final pH 9.0 ± 0.2 at 37°C].

Sample Preparation and Isolation Method for V. parahaemolyticus

In the laboratory, mussel samples were immediately removed from the polythene bag, washed, and scrubbed under running potable water to remove sediment, debris, and attached algae. Samples were then opened aseptically with a sterile knife and the mussel flesh and shell liquid were placed in a sterile jar. Isolation of V. parahaemolyticus was carried out by weighing 25 g of individual sample (extracted mussel flesh) into a sterile stomacher bag with 225 ml of Alkaline Peptone Water (APW) containing 2% NaCl. The seawater and sediment sample bag were mixed thoroughly by shaking the bag for ~1 min while the mussels sample was homogenized in a stomacher for 1 min. All samples were then incubated at 37°C for 6–8 h, for pre-enrichment and then individual samples were serially diluted in APW. Using the surface spread plate technique, 0.1 ml of the diluted sample was spread onto the CV and TCBS agar and incubated at 37°C for 18–24 h. After incubation violet and green colonies were recognized on CV and TCBS agars respectively as being typical of V. parahaemolyticus colonies. Three putative V. parahaemolyticus colonies were then randomly selected from a single plate for each sample analyzed. Individual colonies were suspended in Tryptone Soya Broth (TSB) supplemented with 3% sodium chloride, and incubated at 37°C overnight to obtain broth cultures of isolated bacteria.

Statistical Analysis—Surveillance

The relationship between the counts of V. parahaemolyticus and environmental parameter (temperature and salinity) was analyzed by linear multiple regression. Samples without observable V. parahaemolyticus isolates were assigned the lower limits of detection for each sample. The limits of detection assigned for V. parahaemolyticus was 1 × 103cfu per ml or g for seawater and sediment samples. The total V. parahaemolyticus counts were log-transformed (base 10) and analyzed by regression of the mean Log10 counts of duplicate samples against environmental factors (temperature and salinity). Statistical package Microsoft Excel 2013 and XLSTAT 2014 was used to perform all statistical analyses.

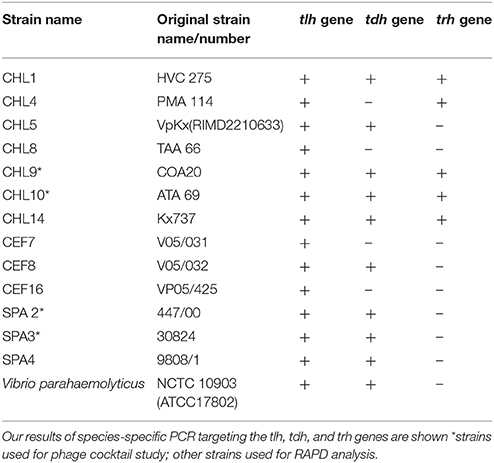

Table 2 provides a list of the pathogenic V. parahaemolyticus strains obtained from Chile and Spain and the reference strain used in this study.

Molecular Analysis

PCR Assays

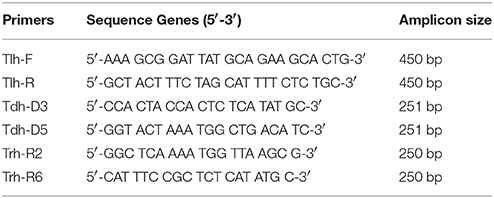

Specific V. parahaemolyticus genes

Bacterial DNA was prepared from overnight broth cultures of individual V. parahaemolyticus colonies grown in Luria Bertani (LB) broth supplemented with 3% NaCl and incubated at 37°C. Supernates containing bacterial template DNA were used (as previously described by Bej et al., 1999) directly in specific-PCR for the detection of tlh gene. The PCR assay was carried out in 0.5 ml Eppendorf tubes with reaction mixtures consisting of sterile PCR grade distilled water: Mercury™ brand Taq DNA 2.0X MasterMix, 6.0 μl DMSO: 2.0 μl; Primer Tlh-F−100 pmol/μl: 1.0 μl; Primer Tlh-R−100 pmol/μl: 1.0 μl, (Table 1A) (Bej et al., 1999); Template DNA−3.0 μl. The reaction mixture was subjected to 35 amplification cycles according to the protocol shown in Table 1B and PCR amplification products (10 μl) and 2 μl of 6x gel loading dye (NEB) were electrophoresed on 1.5% agarose gels at 100 V for 2 h. The gel was stained with ethidium bromide (0.5 μg/ml) and resolved bands visualized under UV transillumination with an imaging system (Kodak, Gel Logic 100).

Pathogenic V. parahaemolyticus genes

PCR was performed separately for trh and tdh genes on isolated V. parahaemolyticus strains and reference organisms (Table 2). The PCR assay was carried out in 0.5 ml Eppendorf tube with reaction mixtures according to the method of Tada et al. (1992). The primers and PCR conditions used are described in Tables 1A,B, PCR amplification products (10 μl) and 2 μl of 6x gel loading dye (NEB) were electrophoresed on 1.5% agarose gels at 100 V for 2 h. The gel was stained with ethidium bromide (0.5 μg/ml) and resolved bands visualized under UV transillumination using an imaging system (Kodak, Gel Logic 100).

Table 2. Clinical isolates of V. parahaemolyticus used in this study including 6 V. parahaemolyticus strains kindly provided by Prof. R.T. Espejo (Chile), 2 strains provided by Dr. Martinez-Urtaza (Spain) and reference strains.

RAPD-PCR Assay

For the genetic diversity studies, genomic DNA was extracted from the organisms by the mini-preparation method described by Ausubel et al. (1987). Amplification reactions were performed in 25 μl volume in a 0.5 ml Eppendorf tubes. The reaction mixture contained 12.5 μl of Mercury™ Taq DNA polymerase master mix (NEB) 8.5 μl of PCR grade water, 1.0 μl of 100 pmol RAPD primer, 1.5 μl of DMSO, and 2.0 μl of template DNA. PCR amplifications were performed as shown in Table 1B. Two primers were chosen for the fingerprinting profile and cluster analysis. The 10-mer oligonucleotide primers were described in previous studies: Gen1-50-08 with oligonucleotide gene sequence 5′-GAG ATG ACG A-′3 (Bilung et al., 2005) and OPD-16 with sequence 5′-AGG GCG TAA G-′3 (Sudheesh et al., 2002). PCR amplification product (7 μl) and 2 μl of gel loading dye were loaded on to a 1.5% agarose gel and electrophoresed at 70 V for 3 h. The resolved bands were visualized under UV transillumination and images captured. Bands were read visually from “fingerprints” generated by the two primers and a data matrix was generated for each primer. A dendrogram was constructed using the data matrix of all the bacterial strains based on Unweighted Pair Group Method with Arithmetic means (UPGMA) using a GelCompar II (Applied Maths) software package.

Determination of Antibiotic Susceptibility of Host Bacteria

Antibiotic sensitivity testing was performed by the Bauer-Kirby disk diffusion method (Bauer et al., 1966).

Isolation of Bacteriophages

Bacteriophages were isolated from seawater or mussels by various enrichment methods described previously by Baross et al. (1978). Briefly, seawater of equal volumes was added to V. parahaemolyticus cultures in log-phase grown in double strength TSB supplemented with 3% NaCl and incubated at 30°C overnight. For isolations from mussels, 25 g of homogenized flesh was added to 225 ml of tryptic soy broth (TSB) or phage buffer (1M Tris HCl, 0.1M NaCl, 8 mM MgSO4, 0.1 g/l gelatin (pH 7.5) and either shaken vigorously for 10 min or enriched at room temperature with slow aeration for 96 h. The mixtures were centrifuged at 13,000 × g for 15 min at 4°C and the supernatant filtered through a 0.45 μm filter. The filtrates (phage lysates) were stored at 4°C until required.

Detection of Lytic Activity of Phages on Panel of V. parahaemolyticus Reference Strains and Isolates

Phage lytic activity was detected by surface inoculation of 25 μl of the filtrate (phage lysates) onto previously prepared lawns of V. parahaemolyticus grown on tryptic soy agar (TSA) supplemented with 3% NaCl in a traditional plaque assay. After incubation at 30°C for 24 h, the presence of zones of clearing (clear or turbid) were measured and recorded (Figure 1B).

Characterization of Phage Lysates

Areas of agar demonstrating clear zones were removed using a sterile pipette and each inoculated into 5 ml of phage broth (prepared by mixing Peptone: 15 g/l; Bacto-Tryptone: 8 g/l; Yeast extract: 1 g/l; NaCl: 25 g/l, pH adjusting to 7.2 with NaOH and autoclaved before aseptically adding 1 mM of MgSO4 and 1 mM of CaCl2.) containing an early log phase culture of V. parahaemolyticus. Following incubation at room temperature for 24 h, the contents was centrifuged at 12,000 × g for 15min at 4°C. Phage titers were determined by the traditional overlay method, i.e., diluted in phage buffer and plated using the soft-agar technique (Adams, 1959). The plates remained at room temperature for 24–48 h. Plaque diameter measurements and numbers were recorded.

Bacteriophage DNA Extraction

Phage lysate (500 μl) obtained from individual plaques was added to 100 μl of 0.5 mM EDTA in a sterile 1.5 ml micro-centrifuge tube. Following 30 min at room temperature 600 μl of water-saturated phenol was added and the tube gently mixed following centrifugation at 13,000 × g for 30 s and 300 μl of the aqueous phase was removed. The phage DNA was stored at 4°C until required.

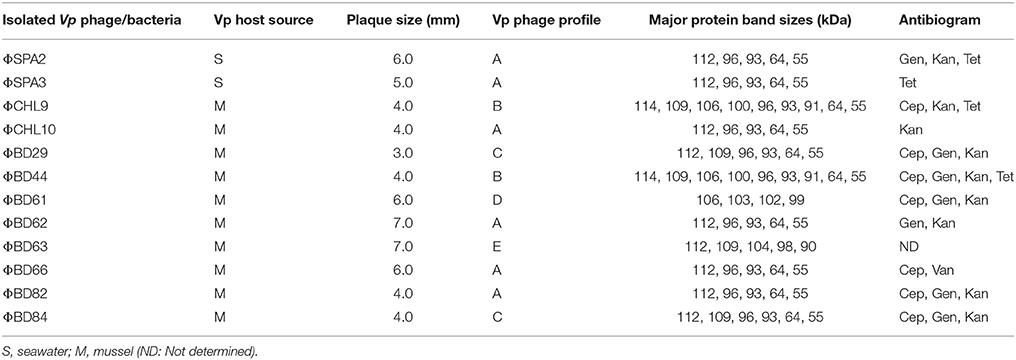

Restriction Fragment Length Polymorphism-PCR (RFLP-PCR) Analysis of Phage DNA

To determine the diversity of phage isolates and the approximate genome sizes from the fragments generated, restriction digestion analyses were carried out with three restriction enzymes. The restriction enzymes HaeIII, HindIII, and EcoRI (Shivu et al., 2007) were used according to the manufacturer's (NEB) instructions. A total volume of 15 μl reaction mixture which contained 13 μl of phage DNA 0.5 μl, HaeIII, HindIII, or EcoRI, and 1.5 μl restriction enzyme buffer (NEB) were placed in 0.5 ml Eppendorf tube. The mixture was then incubated at 37°C for 2 h. The reaction product was subjected to agarose gel electrophoresis (0.8%) at 120 V for 1 h.

Sodium Dodecyl Sulphate-Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) of Phage Protein

SDS-PAGE was performed according to the method of Laemmli (1970), using a separation gel of 12% acrylamide. Phage lysate (7–14 μl) were dissolved in (3–6 μl) SDS-PAGE sample buffer (containing 2-mercaptoethanol), mixture was then heated at 100°C for 5 min. Samples were then inoculated into SDS-PAGE gel and a protein ladder (NEB™) of size ranging from 6.5 to 212 kDa, was used as protein size marker. After electrophoresis the acrylamide gel was submerged in 20 ml of “instant blue” (a coomassie based blue staining solution) obtained from RunBlue™, Expedeon, for 1 h on an orbital shaker and then placed in the fridge overnight. The resulting protein band sizes were determined using GelCompar II software.

Determination of the Host Range of Isolated Phage

A plaque assay method (Adams, 1959) was used to determine the ability of the phages to form individual plaques on one or more V. parahaemolyticus strains. Each phage was named after its respective host bacteria with addition of prefix Φ (phi).

Preparation of VP10 Phage Cocktail

Equal volumes of each prepared phage lysate was centrifuged at 13,000 × g for 15 min. The resulting supernates were then filtered (0.45 μm filter) and stored at 4°C until required.

In-Vitro Activity of Bacteriophage

Overnight cultures (1 ml) of the selected V. parahaemolyticus were added to sterile 1.5 ml Eppendorf tubes and centrifuged at 13,000 × g for 5 min. The supernatant was removed and cell pellets from each strain re-suspended in 1 ml of bacteriophage lysate containing ~1.3 × 102 pfu/ml in TSB supplemented with 3% NaCl. The control samples were also re-suspended in 1 ml of sterile TSB supplemented with 3% NaCl. After thorough mixing, tests and control tubes were incubated at temperatures within the temperature range (5–43°C) for growth of V. parahaemolyticus known to support the growth and multiplication of the organism in the laboratory. Test and control tubes were incubated for 24 h at 30°C, 37°C (optimal temperature) or 40°C for 24 h. Serial dilutions (in sterile distilled water) were prepared and plated onto TSA plates supplemented with 3% NaCl. Plates were incubated at 37°C for 24 h. Bacterial colonies were counted and results expressed in cfu/ml.

In-Vivo Activity of Bacteriophage

In vivo experiments were conducted in 2.5 l glass beakers positioned in a refrigerator at 4°C. Three duplicate containers containing 8–16 harvested mussels each were used together with equal volumes of seawater and sediment and the bacterial numbers of V. parahaemolyticus present in each was determined as cfu/ml (g), before the introduction of the phage cocktail. Ten milliliters of VP10 phage cocktail (~0.1 × 106 pfu) was used. Controls containing mussels, sediment and seawater only in beakers were established. Every 24 h for 3 days samples were removed from treated and controls and 25 g of mussel homogenized prior to plating on to CV agar plates. Colonies were counted after incubation at 37°C for 24 h from both treated and control tanks. Variables such as temperature, salinity and pH were monitored and recorded throughout the period of study with a portable temperature probe and conductivity meter and calibrated pH meter respectively.

Statistical Analysis—Laboratory Analyses

Variations between treatments were analyzed using repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Bonferroni adjustment in SPSS version 14.0. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) is a hypothesis-testing procedure used to determine if mean differences exist for two or more treatments. The purpose of ANOVA in this study is to find out whether the differences between the control and treatment samples are simply due to random error (sampling errors) or whether there are systematic treatment effects that have caused counts in one group to differ from the other. In addition to ANOVA Bonferroni Post- de nova test was used to determine where significant difference between each of the variables lie.

Results

Isolation of V. parahaemolyticus on Selective Agar

CV agar and Thiosulphate Citrate Bile Sucrose Salt (TCBS) were employed as primary isolation media. V. parahaemolyticus were identified as purple and green colonies on CV agar and TCBS respectively. The use of TCBS in differentiating between sucrose positive and negative strains of V. parahaemolyticus was found to be difficult, especially when attempting to detect V. parahaemolyticus within a mixed bacterial culture. The use of chromogenic agar was more effective in detecting V. parahaemolyticus isolates than TCBS. It was observed that more presumptive colonies of V. parahaemolyticus were detected on chromogenic agar than on TCBS, when the same amount of sample was plated onto the different selective agar.

Bacterial Confirmation and Virulence Test (PCR)

PCR amplification of the tlh, tdh, and trh genes yielded amplicons, which were ~450, 251, and 250 bp, respectively. In this present study, detection of these pathogenic markers revealed that 2 V. parahaemolyticus isolated from retail shellfish samples collected during the preliminary study possessed the tdh gene (see Table 2).

Prevalence of V. parahaemolyticus

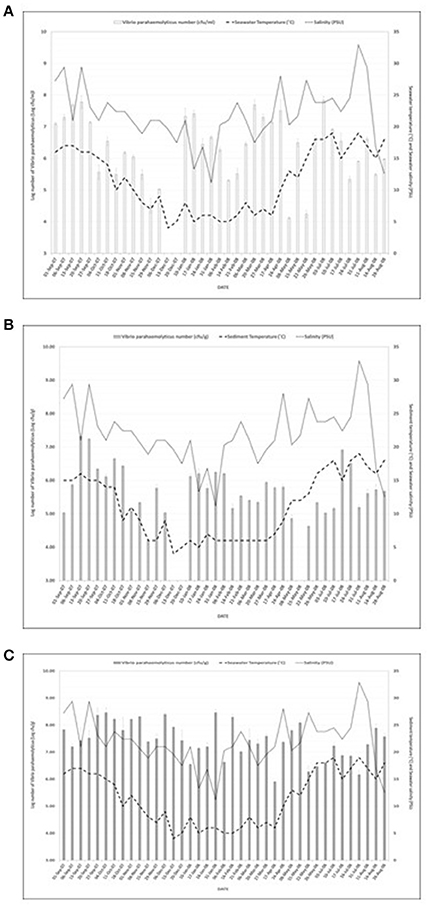

Figure 1A shows the study location of the surveillance study and Figures 2A–C present V. parahaemolyticus counts in seawater, sediment and mussels respectively throughout the year. Isolation of V. parahaemolyticus was 100% (39/39) in mussel, 92.3% (36/39) in sediment, and 94.9% (37/39) in seawater. The organisms were detected in all mussel samples throughout the study period and the counts appeared to be independent of variation recorded in salinity and temperature. Linear regression analysis of the mean Log10 counts of V. parahaemolyticus (in seawater, sediment, and mussels) and environmental parameters showed no significant relationship (P < 0.05) with temperature or salinity. Correlation coefficient and significant level observed when counts of V. parahaemolyticus in seawater were compared with (a) change in seawater temperature were R2 = 0.068 and P = 0.262 respectively, (b) change in salinity were R2 = 0.024 and P = 0.153, respectively. Correlation coefficient and significant level observed when counts of V. parahaemolyticus in sediment were compared with (a) change in sediment temperature were R2 = 0.066 and P = 0.256, respectively, (b) change in salinity were R2 = 0.006 and P = 0.074, respectively. Correlation coefficient and significant level observed when counts of V. parahaemolyticus in mussels were compared with (a) change in seawater temperature were R2 = 0.014 and P = −0.120, respectively, (b) change in salinity were R2 = 0.094 and P = −0.307, respectively.

Figure 2. (A) Number of Vibrio parahaemolyticus isolated from seawater samples in relation to seawater temperature and salinity. R2 = 0.068; P = 0.262 (seawater) and R2 = 0.024; P = 0.153 (salinity). R2 = 0.066; P = 0.256 (temperature) and R2 = 0.006; P = 0.074 (salinity) were observed for counts of V. parahaemolyticus in sediment. And R2 = 0.014; P = −0.120 (temperature) and R2 = 0.094; P = −0.307 (salinity) were observed for counts of V. parahaemolyticus. (B) Number of Vibrio parahaemolyticus isolated from sediment samples in relation to sediment temperature and salinity. R2 = 0.068; P = 0.262 (seawater) and R2 = 0.024; P = 0.153 (salinity). R2 = 0.066; P = 0.256 (temperature) and R2 = 0.006; P = 0.074 (salinity) were observed for counts of V. parahaemolyticus in sediment. And R2 = 0.014; P = - 0.120 (temperature) and R2 = 0.094; P = −0.307 (salinity) were observed for counts of V. parahaemolyticus. (C) Number of Vibrio parahaemolyticus isolated from mussels in relation to seawater temperature and salinity. R2 = 0.068; P = 0.262 (seawater) and R2 = 0.024; P = 0.153 (salinity). R2 = 0.066; P = 0.256 (temperature) and R2 = 0.006; P = 0.074 (salinity) were observed for counts of V. parahaemolyticus in sediment. And R2 = 0.014; P = −0.120 (temperature) and R2 = 0.094; P = −0.307 (salinity) were observed for counts of V. parahaemolyticus.

RAPD-PCR Assay

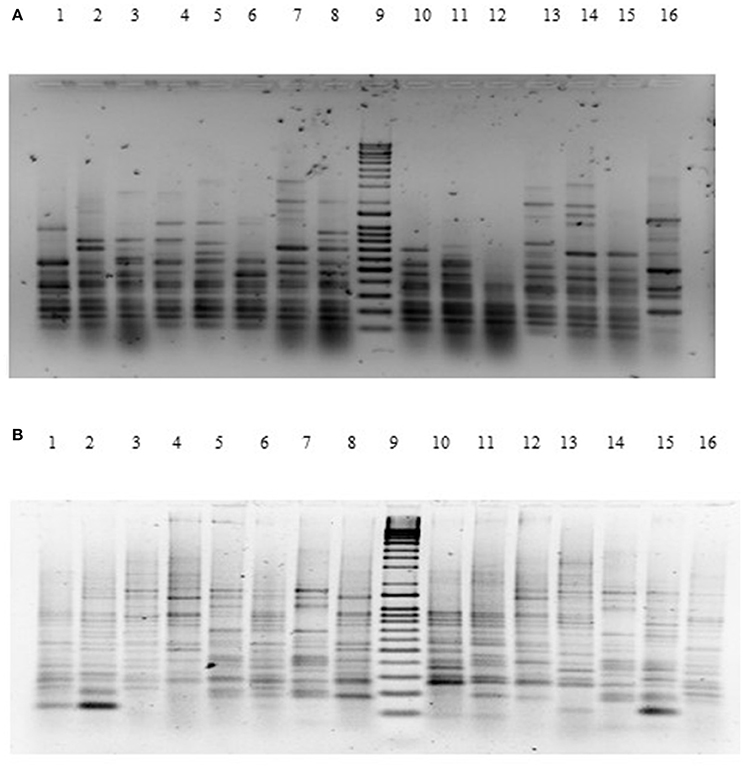

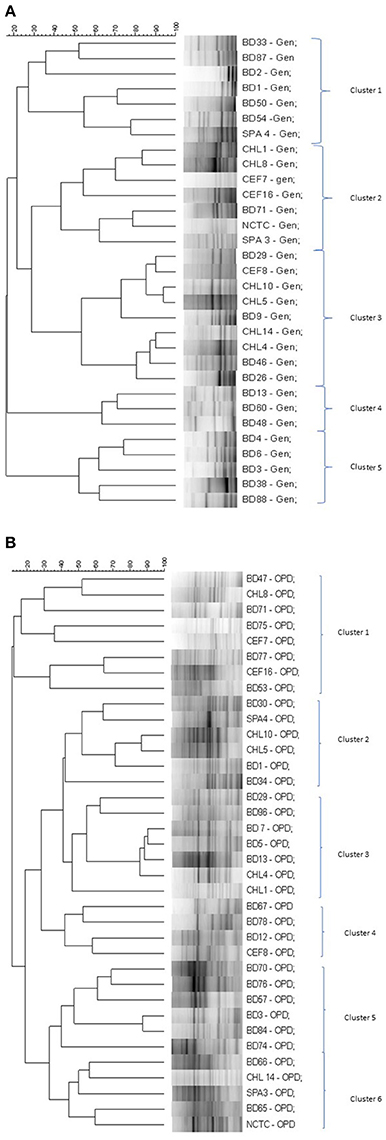

The genetic relatedness of the V. parahaemolyticus isolates studied was demonstrated using RAPD-PCR and revealed a high degree of heterogenicity between V. parahaemolyticus isolates recovered from the Humber and isolates from Chile, Spain, and other regions of the UK. Representative results of the RAPD patterns obtained are shown in Figures 3A,B as examples. GelCompar version 4.1 software was used to construct a phylogenetic dendrogram. The data from primers Gen1-05-08 and OPD-16 generated a distance matrix and V. parahaemolyticus isolates were allocated to 5 and 6 major clusters for each primer respectively (Figures 3A,B).

Figure 3. (A) Agarose (1.5%) gel electrophoresis of RAPD-PCR products for primer GEN1-50-08 of V. parahaemolyticus isolates. Lanes Lane 1: BD1; Lane 2: BD2; Lane 3: BD3; Lane 4: BD4; Lane 5: BD6; Lane 6: BD7; Lane 7: BD35; Lane 8: BD9; Lane 9: Q-4 DNA ladder; Lane 10: BD14; Lane 11: BD37; Lane 13: BD33; Lane 14: BD54; Lane 15: BD34; Lane 16: BD39. (B) Agarose (1.5%) gel electrophoresis of RAPD-PCR products for primer OPD16 of V. parahaemolyticus isolates. Lane 1: CHL16; Lane 2: CHL1; Lane 3: CHL14; Lane 4: BD7; Lane 5: BD84; Lane 6: BD1; Lane 7: BD3; Lane 8: BD5; Lane 9: Q-4 DNA ladder; Lane 10: BD34; Lane 11: BD30; Lane 12: BD29; Lane 13: BD77; Lane 14: BD71; Lane 15: BD47; Lane 16: BD75.

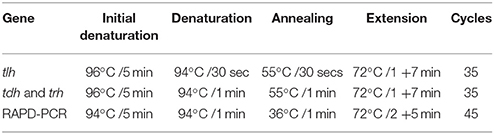

Isolation and Characterization of Bacteriophages

The phage lysate from water or mussel samples after enrichment produced clear zones of lysis on bacterial lawns as shown in Figure 1B. A total of 61 bacteriophages producing distinctive plaque sizes were recovered from the Humber and both turbid and clear plaques were observed. Twelve phages (non-turbid zones of clearing between 3 and 7 mm) were then chosen to study further. The host susceptibility range of isolated phages was determined for the 12 V. parahaemolyticus strains (SPA2, SPA3, CHL9, CHL10, BD29, BD44, BD61, BD62, BD63, BD66, BD82, BD84) which comprised our putative phage cocktail (VP10) and further characterization showing protein band profiles (data not shown) indicated 5 distinct biotypes as described in Table 3. DNA fragments were visualized from individual phages used in VP10 and the overall genome size was estimated to be in the range of 21 kb (Figure 7). Restriction fragment length analysis demonstrated that EcoRI, HindIII, and HaeIII were unable to digest any of the phage isolate DNA at all.

Determination of Antibiotic Susceptibility of Host Bacteria

Antibiotic susceptibility/resistance evaluation of bacteriophage host V. parahaemolyticus by zone diameter around the antibiotic disks revealed that 82% of the bacteria strains were resistant to kanamycin, 64% were resistant to gentamicin and cephazolin while 36% were resistant to tetracycline. No resistance was observed for ampicillin, chloramphenicol, ciprofloxacin, and vancomycin.

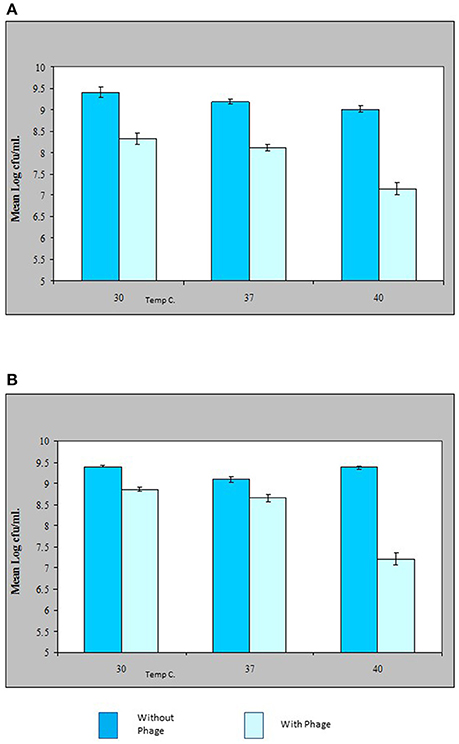

Activity of Phage in-Vitro Against V. parahaemolyticus

The results shown in this study indicate that the VP10 cocktail in vitro was effective in reducing the numbers of pathogenic V. parahaemolyticus in an experimental context. Figure 5 shows some typical results of lytic activity of phages ΦSPA2 and ΦSPA3 against their respective pathogenic V. parahaemolyticus hosts at different incubation temperatures. Viable counts of V. parahaemolyticus strains SPA2 and SPA3 were reduced by an average of 1 log unit at 30 and 37°C, whereas at 40°C viable counts were reduced by an average of 2 log units. Analysis of variance revealed significant differences (p ≤ 0.05) between counts of V. parahaemolyticus obtained with the control and treated samples. There was however no significant different between counts (shown in Fig A+B) of V. parahaemolyticus SPA2 (F = 2.38, p = 0.17) and SPA3 (F = 1.82, p = 0.24) recorded at different temperatures. Multiple comparisons between the effect of phage treatment and temperature of incubation was analyzed using Bonferroni adjustment, and the statistical analysis revealed that there were significance differences (p < 0.05) between results obtained at 40°C as compared to 30 and 37°C, there was however no significant difference (p = 0.44) between results obtained at 30 and 37°C.

Figure 4. (A) Simplified dendrogram based on UPGMA generated by Gel compare software showing genetic similarity from RAPD profiles of V. parahaemolyticus isolates (Gen1-50-08). (B) Simplified dendrogram based on UPGMA generated by Gel compare software showing genetic similarity from RAPD profiles of V. parahaemolyticus isolates (OPD16).

Figure 5. Effect of bacteriophage treatment on Vibrio parahaemolyticus SPA2 (A) or SPA3 (B) in Tryptone Soya Broth incubated at 30, 37, and 40°C. Each bar represents the mean V. parahaemolyticus counts of duplicate samples. Error bars denote the standard error of the means of triplicate experiments.

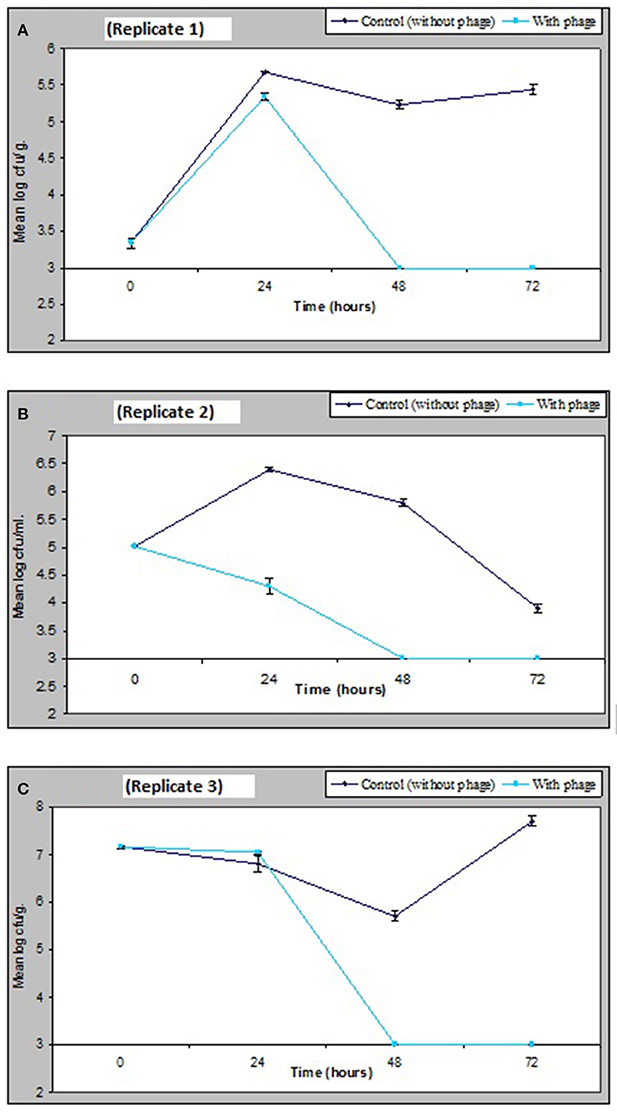

Activity of Phage in-Vivo Against V. parahaemolyticus

The results obtained in Figure 6 demonstrate that a relatively low numbers of phage in a cocktail has the potential of controlling numbers of V. parahaemolyticus impressively in vivo. Figure 6 shows that as little as 1.3 × 103 pfu/ml of VP10 phage cocktail was effective in significantly reducing V. parahaemolyticus to undetectable numbers in mussels from three replicate experimental tanks after 48 h. V. parahaemolyticus was also reduced to undetectable levels after 48 h in seawater and sediment (Figure 6). Analysis of variance revealed significant differences (p < 0.01) between counts of V. parahaemolyticus obtained in the treated and control (no phage) samples throughout the study period (F = 314, p = 0.00 for seawater; F = 281, p = 0.00 for sediment; and F = 205, p = 0.00 for mussel flesh samples). A lower inoculum of phage cocktail tested 6.75 × 102 pfu/ml produced a similar but less pronounced effect with significant difference between the inoculum size differences for treatments for samples (F = 9.9, p = 0.04 for sediment and F = 37.6, p = 0.004 for mussel samples) although not for seawater (F = 6.9, p = 0.059).

Figure 6. Effect of bacteriophage treatment on V. parahaemolyticus in seawater, sediment or mussels after 72 h. Each line represents the mean of duplicate bacteria counts. Error bars denote the standard error of the mean duplicate bacterial counts.

Discussion

CV agar clearly distinguished V. parahaemolyticus colonies from other unwanted colonies, confirming the results of other studies (Hara-Kudo et al., 2001; Duan and Su, 2005; Blanco-Abad et al., 2009; Canizalez-Roman et al., 2011). The violet color of V. parahaemolyticus remained on CV agar even when they were physically covered by other colored colonies produced by different vibrio species or other bacteria whereas V. parahaemolyticus colonies on TCBS agar were occasionally hidden by the yellow color produced by sucrose-fermenting bacteria such as V. alginolyticus. The use of CV agar in combination with PCR assay targeting the tlh gene was found to be a rapid, sensitive, and accurate method for the isolation and identification of V. parahaemolyticus from environmental samples.

The presence of virulence genes tdh and trh in environmental samples has been reported to be very rare, and in this present study, detection of these pathogenic markers revealed that 2 V. parahaemolyticus isolated from retail shellfish samples collected during the preliminary study possessed the tdh gene (see Table 2). The low incidence of pathogenic strains (0.9%) in environmental samples (especially retail shellfish) analyzed in this study is interesting when considering the increased risk of human infection associated with them (Bej et al., 1999; Cook et al., 2002; DePaola et al., 2003). The results in this study are however in agreement with studies that have reported only low percentages of environmental isolates possessing tdh and/or trh (Robert-Pillot et al., 2004; Deepanjali et al., 2005; Canizalez-Roman et al., 2011; Gutierrez West et al., 2013; Letchumanan et al., 2015) and demonstrates that the continued monitoring of environmental V. parahaemolyticus is useful and should be encouraged.

V. parahaemolyticus are frequently recovered from the water, sediments, suspended particles, plankton, and marine species including shellfish (Joseph et al., 1982; Daramola et al., 2009; Zhang and Orth, 2013). As reported by Kaneko and Colwell (1975), El-Sahn et al. (1982), Ristori et al. (2007), and Martinez-Urtaza et al. (2008) the numbers of V. parahaemolyticus in the environment and in seafood has been reported to vary greatly according to season, location, sample type, and analytical methodology employed. Figure 1A shows the study location of the present surveillance study and Figures 2A–C present V. parahaemolyticus counts in seawater, sediment, and mussels, respectively. Although another study by Cook et al. (2002) revealed significant correlation between temperature and level of V. parahaemolyticus in shellfish, others have reported that there was no correlation between temperature and salinity and numbers of V. parahaemolyticus (Kaneko and Colwell, 1973; Thompson and Vanderzant, 1976; Deepanjali et al., 2005; Ristori et al., 2007). In this present study we found no significant correlation between level of V. parahaemolyticus (in seawater and sediment) and temperature and salinity. Similar result were also observed for level of V. parahaemolyticus in mussels and seawater and salinity. For mussel samples V. parahaemolyticus were detected in all mussel samples throughout the study period and the counts appeared to be independent of variation recorded in salinity and temperature. The environmental drivers that affect the population of V. parahaemolyticus in shellfish are complex (Paranjpye et al., 2015) as other factors beyond temperature and salinity have been shown to also play a part. Factors such as nutrients, chlorophyll-a, plankton, dissolved organic carbon and turbidity have varying effects depending on species, geographic location, or environmental niche (Takemura et al., 2014). Although in this study our focus was mainly on observing the effect of seawater and sediment temperature and salinity on level of V. parahaemolyticus, other factors such as temperature of mussel meat, level of nutrients present in the environment were not considered. Further studies incorporating additional variables including internal temperature of mussel meat might provide additional insight into the conditions that impact levels of V. parahaemolyticus in environmental samples.

The prevalence of V. parahaemolyticus in marine animals during cold and warm months and the lack of seasonal variation in numbers of environmental V. parahaemolyticus in temperate zones has been reported by Thompson and Vanderzant (1976). Lack of recent comparative data is surprising and our results clearly suggest the continual presence of V. parahaemolyticus in mussels in the estuarine environment of the temperate River Humber throughout the year.

In the RAPD study, all the clusters generated by the two primers suggest inter-clustering of the “clinical” and “environmental” isolates except clusters 4 and 5 in Figure 4A and cluster 5 in Figure 4B which were observed to group together isolates from the study area. Isolates of V. parahaemolyticus have previously been shown to be heterogeneous by RAPD-PCR from a variety of geographical locations and climates (Sudheesh et al., 2002; Bilung et al., 2005; Ellingsen et al., 2008; Sahilah et al., 2013). Our study confirms a high degree of genetic diversity and strain variation within both “clinical” and “environmental” categories.

Viruses infecting bacteria are an essential biological component in aquatic microbial food webs. They play a key role in controlling cell mortality, nutrient cycles, and microbial diversification for planktonic communities (Jacquet et al., 2010). Phages are similar to antibiotics in that they have remarkable killing activity. All bacteriophages known to date are specific, reacting to only their targeted bacterial host and not to human or other eukaryotic cells. This is in clear contrast to broad spectrum antibiotics which target both pathogenic microorganisms and the normal microbiota. Phages are generally isolated from environments that are habitats for their respective host bacteria (Vinod et al., 2005). In this present study, all the samples from which V. parahaemolyticus has been isolated (seawater, sediment, and shellfish) were tested for the presence of bacteriophage against V. parahaemolyticus and seawater and mussel samples tested positive for the presence of these phages which suggests that marine samples being the habitat for V. parahaemolyticus would be ideal source for isolation of V. parahaemolyticus phages.

The investigation of V. parahaemolyticus phage distribution in the marine environment using cultures of bacterial hosts combined with plaque or lysis assay, shows that phages are ubiquitous and present in varied numbers. However, the isolation of phages from the estuarine environment was not without difficulty. Repeated attempts were carried out before successfully isolating these phages, also after successfully isolating phages it was observed that mussel samples yielded more V. parahaemolyticus specific phage as compared to seawater, this observation is in agreement with Baross et al. (1978) who reported higher incidence of bacteriophage in marine animals as compared to sediment and seawater. Reports of difficulty in isolating bacteriophage from marine samples other than shellfish have also be published by Johnson (1968) who investigated marine mud samples for presence of bacteriophages but was successful only once out of 15 attempts. Also, Hidaka and Tokushige (1978) sampled 18 enriched seawater samples from different locations but found phages for only 11 isolates of V. parahaemolyticus. Hidaka (1973) isolated 165 bacteria from 6 marine locations and obtained only 16 phage-host systems. Remarkably, Baross et al. (1978), also obtained phages from seawater from only two out of 64 trials, and from sediments in four out of 69 attempts. Although further research is required to determine incidence of phages in different marine samples, Baross et al. (1978) however suggests that higher frequency in the isolations of bacteriophages from marine animals might be an indication that these viruses play an important role in the ecology of marine vibrios.

In this present study, isolated bacteriophages produced distinctive plaque morphologies when plated on lawns of their host bacterium using soft-agar overlay technique. Both turbid and clear plaques were isolated and based on the morphology of the plaques produces by the bacteriophages, 12 out of the 61 isolated phages were selected because they produced very clear plaques on lawns of host bacteria which strongly suggested that they were lytic (Jurczak-Kurek et al., 2016).

Molecular characterization of the phages by restriction fragment length analysis of bacteriophage DNA revealed that EcoRI, HindIII, and HaeIII were unable to digest the phage DNA. This observation is in agreement with that of Sen and Ghosh (2005), they have also found resistance to EcoRI in marine bacteriophage of V. cholerae. Also Dutta and Ghosh (2007) observed that vibrio bacteriophage Phage S20 DNA was found to be resistant to EcoRI and other restriction enzymes. Bacteriophage defense adaptations to avoid host restriction systems might be an explanation to the observed restriction enzyme resistance of isolated phage in this study. Among these defense adaptations are the unusual modification of DNA, low frequency of target sequences, and the production of a protein that interferes with one or more of the activities of a Restriction-Modification system (Murray, 2000).

The use of protein analysis to characterize bacteriophage proved to be a straightforward and useful tool in characterizing phages as compared to PCR-RFLP, the band profile was able to reveal 5 patterns. The use of SDS-PAGE has been employed by other researchers and they have also found the method to be useful in characterizing vibrio bacteriophages (Alonso et al., 2002; Walter and Baker, 2003; Dutta and Ghosh, 2007).

Antibiotic treatment is necessary for controlling V. parahaemolyticus infections however the overuse of antibiotics has brought about antimicrobial resistant bacteria, which is becoming a major concern for human health (Ji et al., 2011; Shaw et al., 2014; Blair et al., 2015; Letchumanan et al., 2015). The overall resistance pattern of the phage host V. parahaemolyticus investigated in this study reveals resistance to cephalozin (64%) which is in agreement with Li et al. (2017), gentamicin (64%), kanamycin (82%), and tetracycline (36%). No resistance was however recorded for ampicillin, chloramphenicol, ciprofloxacin, and vancomycin. The result obtained for ampicillin and chloramphenicol is agreement with the data published by Letchumanan et al. (2015). Letchumanan et al. (2015) reported that only 4 and 5% of strains tested were resistant to ampicillin and chloramphenicol respectively. This is however contrary to the result obtained by Li et al. (2017) especially for ampicillin for which 100% resistance was reported for strains tested in their study. Foods contaminated with antibiotic resistant determinants may be transferred to other bacteria of clinical significance; and V. parahaemolyticus is a candidate vehicle for such transfer because of its diversity and its ability survive in the gastrointestinal tracts of both human and animals (Zulkifli et al., 2009).

The results obtained from this present research confirms the role of the environment and most especially contaminated shellfish as a reservoir of antibiotic resistant bacteria some of which contain antibiotic resistance genes which can easily be transferred to other bacteria of clinical significance and so causing a major problem for humans and a threat to public health.

Bacteriophages are natural and most abundant biological entities in the environment, it is estimated that there are about 1031 phages on earth and they are ~10 times more than their bacterial hosts (Abedon et al., 2011; Burrowes et al., 2011). The potential effect of specific bacteriophage in controlling the population of their target host bacteria has been studied extensively and quantified over the past decades however to the best of our knowledge the impact of bacteriophages already present in the environment on marine bacterial population has not been quantitatively measured. Although the effect of viruses on the populations of microbes that co-exist with them in the same environment is unknown and has not been quantified in this study however, the fact that vibrio phages could not be isolated without previously propagating in enrichment medium indicates that densities of specific vibrio phages (able to infect our isolated and reference strains) are relatively low in the marine samples tested. Also some samples from which V. parahaemolyticus were isolated did not harbor their corresponding phages, suggesting that specific hosts and lytic phages did not always coexist in the same environment (Tan et al., 2014).

The majority of all marine phages are highly host specific (Coetzee, 1987) and 75% lyse only the original host bacterium. One of the phages (ΦBD61) in our study formed clear plaques on 2 other V. parahaemolyticus isolates (BD62 and BD63), but was unable to form plaques on lawns of 9 of our V. parahaemolyticus isolates. This result is in agreement with Sklarow et al. (1973) who showed that V. parahaemolyticus phages are highly specific; giving no lytic response on 53 V parahaemolyticus strains or 95 other Vibrio strains in their study. For effective phage applications it is probably necessary to design highly multi-component cocktails as demonstrated here. Also for identification and selection of phages for phage therapy the use the efficiency of plating (EOP) method can enhance the selection of rather than the spot test (Mirzaei and Nilsson, 2015) which reflects the bactericidal effect of phages.

Studies into the potential of bacteriophage as agents of therapy against bacterial pathogens in aquaculture have been reviewed (Nakai and Park, 2002; Jun et al., 2013; Madsen et al., 2013). In the present study, in comparison with controls remarkably small inocula tested significantly reduced the recovery from naturally contaminated mussels and seawater. Temperature, pH, and salinity play important roles in the ability of phage-control of bacterial pathogens. Phage are generally more stable in alkaline pH than in acidic pH, and vibriophage are stable at pH range of 5.0–9.0 (Dutta and Ghosh, 2007). Lower pH can interfere with lysozyme or protein coats preventing phage attachment to receptor sites of the host cell (Leverentz et al., 2004). Vibriophage can be sensitive to elevated temperatures interfering with phage attachment, and V. parahaemolyticus phages have a requirement for salts at marine concentrations for infection and growth. However, very high salt concentrations can adversely affect the protein coat and phage enzyme activity. At low salt concentrations, salt ions interact with proteins and stabilize protein structure by neutralizing protein charges (Baross et al., 1978; Fennema, 1996).

Phage biocontrol of foodborne pathogens is an interesting idea, which is gaining momentum as a feasible alternative to antibiotic use. Several studies describing such uses have now been published and reviewed. These include the application of phage to control Salmonella species in bean sprouts (Ye et al., 2010), broiler carcasses (Fiorentin et al., 2005; Atterbury et al., 2007), frankfurters (Guenther et al., 2012), chicken skin (Hungaro et al., 2013), cheese (Modi et al., 2001), and melon (Leverentz et al., 2001); Listeria monocytogenes on melon (Leverentz et al., 2003, 2004; Hong et al., 2015) and cheeses (Guenther and Loessner, 2011); Campylobacter on chicken skin (Atterbury et al., 2003); and Escherichia coli O157 on retail beef (Wang et al., 2017). Commercial production of the first phage for use in foods was in the Netherlands, with the Listex™ P100 product (Carlton et al., 2005) which was launched to control Listeria in cheese and meat. This preparation received FDA approval.

Considerations in designing phage biocontrol strategies must include pH, temperature, and salt concentration in the microenvironment although the possible response of the host defense in shellfish and physiology of the pathogen in-vivo may be equally important. A more complete understanding of the environmental and physiological influences should provide some explanation for the disparity among phage lytic activities in vitro and in vivo, and enable the design of the more effective phage biocontrol strategies in the future. Another important impediment to phage biocontrol is the requirement for a threshold density of bacterial host cells. The need for bacterial populations of 3 to 5 log cfu/ml has been reported for phage to have an impact upon hosts (Wiggins and Alexander, 1985; Kennedy and Bitton, 1987).

In phage therapy a key determinant of the phage potential to eradicate bacterial targets is phage density in relation to the host cells. Multiplicity of infection (MOI) is the ratio between the number of viruses in an infection and the number of host cells and can be determined by adjusting the relative concentration of virus and host (Thomas, 2001). It is important to be able to adjust these concentration of virus and host and calculate phage dose (phage density) required for effective phage therapy (Thomas, 2001; Abedon et al., 2011). However, defining MOI in terms of the number of phages that have to be added to bacteria can be misleading especially so when densities of bacteria are low or phage adsorption slow (Abedon, 2016). The use of MOI as the sole means of describing dosing during phage-mediated biocontrol of bacteria (Payne and Jansen, 2001; Harper, 2006; Abedon, 2009) can be a problem during phage therapy. The simple ratio of virus particles to cells given by the MOI is also shown by Kasman et al. (2002), to be illogical in the absence of information about other parameters such as the density of host cells, the adsorption constant of the phage, the number of phage, and the length of time for which they interact.

In our in vitro and in vivo studies, the levels of V. parahaemolyticus at the point of introduction of the phages were 103 and 109 cfu/ml respectively, from these studies it seems that number of bacteria (whether low or high) are unlikely to affect the effectiveness of phage in bacteriophage therapy. This result shows the potential of the use phages in systems where low level of bacterial pathogens are found (i.e. in naturally contaminated food which can sometimes have as low as 1 × 10 CFU/g or ml of pathogen present). As discussed by Hagens and Loessner (2010), in as much as the concentration of the reaction partners (phage) is sufficient enough to enable contact and subsequent reaction (infection and killing) the other reaction partner can be present at a very low Concentration (numbers of bacteria). The researchers state that, in fact, once a critical concentration threshold of phage numbers is reached to enable it to cover the entire available space within any given matrix, the concentration of the bacterial host is not important, i.e., it does not matter whether only 1 or 106 cells per ml are present, they will all be infected (Hagens and Loessner, 2010).

Another problem with phage therapy is the narrow host specificity of bacteriophages, in a study conducted to control food spoilage organisms it was shown that if the host range of a bacteriophage is too narrow biocontrol is ineffective (Greer and Dilts, 1990). For effective biocontrol therefore, phages should have a well-balanced/almost perfect host range which is neither too narrow nor too broad. An example of such phage is Felix O1 which lyses 96–99.5% of Salmonella serovars (Lindberg, 1967). Also for successful biocontrol the use of phage cocktail (rather than a single phage) is required and this approach has proved successful in a study published by O'Flynn et al. (2004) who investigated the use of phages for controlling Escherichia coli O157:H7 on beef.

Finally, another obstacle to phage therapy is public perception, would the average consumer respond favorably to the introduction of viruses to their food? The proof of the safety of phage have been demonstrated by phage therapy pioneers who deliberately ingested the phage preparations themselves. In 1919, d'Herelle, Hutinel, and several hospital interns ingested a phage preparation which was intended to treat dysentery before administering it to a 12-year old boy in order to confirm the safety of the phage preparation (Summers, 1999). Bruttin and Brussow (2005) also reported the safe intake of T4 phage by volunteers. In addition in an American article it was indicated that some people see phages as “green” and environmentally friendly (Fox, 2005). Phages have also been seen as a “natural” alternative to chemical preservatives. Whatever the perceptions concerning safety of phages it is a fact that phages are globally numerous (1031) and a natural component of foods (Tsuei et al., 2007) which are being ingested by everyone every day. The direct application of phages to food or food processing protocols is only one of many biocontrol approaches that might be adopted.

Conclusion

The results obtained in this study reveal the occurrence of V. parahaemolyticus in the temperate conditions of the River Humber throughout the year. In particular V. parahaemolyticus contaminated mussels were recovered from the temperate estuary throughout the colder months in contrast to other studies. Uncooked or partly cooked non-farmed shellfish consumption presents increased risk from temperate estuarine harvests at any time of the year. No distinct clustering occurred following RAPD-PCR analysis between environmental and “clinical” isolates. Specific cocktails of bacteriophages tested against recovered isolates of V. parahaemolyticus in experimental settings significantly reduced the organism in vitro and in vivo. Our preliminary work reported here shows that potential eradication in-vitro and in vivo by specific cocktails of phage in low numbers in an experimental setting provides evidence of the valuable potential of phage as a decontamination agent in mussel processing.

Author Contributions

BO designed and performed all the experiments and associated data analysis and prepared a draft manuscript. BO also participated in the coordination of the project. RD conceived the study, designed and coordinated the project. RD co-authored the manuscript revising it for important intellectual content. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

BO was self-funded and consumables supported by infrastructural funding from the University of Lincoln.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

Clinical V. parahaemolyticus strains; CHL1, CHL4, CHL5, CHL8, CHL10, and CHL14 were provided by Prof. R.T. Espejo, clinical strains: SPA3 and SPA4 were provided by Dr. J. Martinez-Urtaza and strains: CEF7, CEF8, and CEF16 were provided by Dr. R. Rangdale, CEFAS, Weymouth UK. We thank Dr. Ross Williams for very useful discussions and Joseph Brown for reading and commenting on the draft manuscript.

References

Abedon, S. T. (2009). Kinetics of phage-mediated biocontrol of bacteria. Foodborne Pathog. Dis. 6, 807–815. doi: 10.1089/fpd.2008.0242

Abedon, S. T. (2016). Phage therapy dosing: the problem(s) with multiplicity of infection (MOI). Bacteriophage 6:e1220348. doi: 10.1080/21597081.2016.1220348

Abedon, S. T., Kuhl, S. J., Blasdel, B. G., and Kutter, E. M. (2011). Phage treatment of human infections. Bacteriophage 1, 66–85. doi: 10.4161/bact.1.2.15845

Alonso, M. D., Rodriguez, J., and Borrego, J. J. (2002). Characterization of marine bacteriophages isolated from Alboran sea (Western Mediterranean). J. Plankton Res. 24, 1079–1087. doi: 10.1093/plankt/24.10.1079

Atterbury, R. J., Connerton, P. L., Dodd, C. E., Rees, C. E., and Connerton, I. F. (2003). Application of host-specific bacteriophages to the surface of chicken skin leads to a reduction in recovery of Campylobacter jejuni. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69, 6302–6306. doi: 10.1128/AEM.69.10.6302-6306.2003

Atterbury, R. J., Van Bergen, M. A., Ortiz, F., Lovell, M. A., Harris, J. A., De Boer, A., et al. (2007). Bacteriophage therapy to reduce Salmonella colonization of broiler chickens. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 73, 4543–4549. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00049-07

Ausubel, F. M., Brent, R., Kingston, R. E., Moore, D. D., Sideman, J., Smith, J., et al. (1987). Preparation of Genomic DNA from Bacteria. Curr. Protoc. Mol. Biol. Unit 24, Supplement 27. 2.4.1–2.4.5.

Babalova, E. G., Katsitadze, K. T., Sakvarelidze, L. A., Imnaishvili, N. S., Sharashidze, T. G., Badashvili, V. A., et al. (1968). Preventive value of dried dysentery bacteriophage. Zh. Mikrobiol. Epidemiol. Immunobiol. 2, 143–145.

Baker-Austin, C., Trinanes, J. A., Taylor, N. G., Hartnell, R., Siitonen, A., and Martinez-Urtaza, J. (2013). Emerging Vibrio risk at high latitudes in response to ocean warming. Nat. Clim. Change 3, 73–77. doi: 10.1038/nclimate1628

Baross, J. A., Liston, J., and Morita, R. Y. (1978). Incidence of Vibrio parahaemolyticus bacteriophages and other Vibrio bacteriophages in marine samples. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 36, 492–499.

Bauer, A. W., Kirby, W. M., Sherris, J. C., and Turk, M. (1966). Antibiotic by standarized single disk method. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 45, 493–496. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/45.4_ts.493

Bej, A. K., Patterson, D. P., Brasher, C. W., Vickery, M. C., Jones, D. D., and Kaysner, C. A. (1999). Detection of total and hemolysin-producing Vibrio parahaemolyticus in shellfish using multiplex PCR amplification of tlh, tdh and trh. J. Microbiol. Methods 36, 215–225. doi: 10.1016/S0167-7012(99)00037-8

Bilung, L. M., Radu, S., Bahaman, A. R., Rahim, R. A., Napis, S., Kqueen, C. Y., et al. (2005). Random amplified polymorphic DNA-PCR typing of Vibrio parahaemolyticus isolated from local Cockles (Anadara granosa). Am. J. Immunol. 1, 31–36. doi: 10.3844/ajisp.2005.31.36

Blair, J. M., Webber, M. A., Baylay, A. J., Ogbolu, D. O., and Piddock, L. J. (2015). Molecular mechanisms of antibiotic resistance. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 13, 42–51. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro3380

Blanco-Abad, V., Ansede-Bermejo, J., Rodriguez-Castro, A., and Martinez-Urtaza, J. (2009). Evaluation of different procedures for the optimised detection of Vibrio parahaemolyticus in mussels and environmental samples. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 129, 229–236. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2008.11.028

Bruttin, A., and Brüssow, H. (2005). Human volunteers receiving Escherichia coli phage T4 orally: a safety test of phage therapy. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 49, 2874–2878. doi: 10.1128/AAC.49.7.2874-2878.2005

Burrowes, B., Harper, D. R., Anderson, J., McConville, M., and Enright, M. C. (2011). Bacteriophage therapy: potential uses in the control of antibiotic resistant pathogens. Expert Rev. Anti Infect. Ther. 9, 775–785. doi: 10.1586/eri.11.90

Canizalez-Roman, A., Flores-Villaseñor, H., Zazueta-Beltran, J., Muro-Amador, S., and León-Sicairos, N. (2011). Comparative evaluation of a chromogenic agar medium-PCR protocol with a conventional method for isolation of Vibrio parahaemolyticus strains from environmental and clinical samples. Can. J. Microbiol. 57, 136–142. doi: 10.1139/w10-108

Caplin, J. (2009). Bacteriophage therapy, old treatment, new focus? Microbiol. Soc. Appl. Microbiol. 10, 20–23.

Carlton, R. M., Noordman, W. H., Biswas, B., de Meester, E. D., and Loessner, M. J. (2005). Bacteriophage P100 for control of Listeria monocytogenes in foods: genome sequence, bioinformatic analyses, oral toxicity study, and application. Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 43, 301–312. doi: 10.1016/j.yrtph.2005.08.005

Ceccarelli, D., Hasan, N. A., Huq, A., and Colwell, R. R. (2013). Distribution and dynamics of epidemic and pandemic Vibrio parahaemolyticus virulence factors. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 3:97. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2013.00097

Coetzee, J. N. (1987). “Bacteriophage taxonomies,” in Phage Ecology, eds S. M. Goyal, C. P. Gerba, and G. Bitton (New York, NY: Wiley and Sons Interscience).

Cook, D. W., Bowers, J. C., and DePaola, A. (2002). Density of total and pathogenic (tdh+) Vibrio parahaemolyticus in Atlantic and Gulf Coast molluscan shellfish at harvest. J. Food Prot. 65, 1873–1880. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X-65.12.1873

Daniels, N. A., MacKinnon, L., Bishop, R., Altekruse, S., Ray, B., Hammond, R. M., et al. (2000). Vibrio parahaemolyticus infections in the United States, 1973-1998. J. Infect. Dis. 181, 1661–1666. doi: 10.1086/315459

Daramola, B. A., Williams, R., and Dixon, R. A. (2009). In vitro antibiotic susceptibility of Vibrio parahaemolyticus from environmental sources in northern England. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 34, 499–500. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2009.06.015

Deepanjali, D., Kumar, H. S., Karunasagar, I., and Karunasagar, I. (2005). Seasonal varaiation in abundance of total and pathogenic Vibrio parahaemolyticus bacteria in oysters along the south west coast of India. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71, 3575–3580. doi: 10.1128/AEM.71.7.3575-3580.2005

DePaola, A., Ulaszek, J., Kaysner, C. A., Tenge, B. J., Nordstrom, J. L., Wells, J., et al. (2003). Molecular, serological, and virulence characteristics of Vibrio parahaemolyticus isolated from environmental, food, and clinical sources in North America and Asia. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69, 3999–4005. doi: 10.1128/AEM.69.7.3999-4005.2003

Domingue, G., Willshaw, G. A., Smith, H. R., Perry, M., Radforth, D., and Cheasty, T. (2003). DNA-based sub-typing of verocytotoxin-producing Escherichia coli (VTEC) O128ab:H2 strains from human and raw meat sources. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 37, 433–437. doi: 10.1046/j.1472-765X.2003.01424.x

Duan, J., and Su, Y. C. (2005). Comparison of a chromogenic medium with thiosulfate-citrate-bile salts-sucrose agar for detecting Vibrio parahaemolyticus. J. Food Sci. 70, 125–128. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2621.2005.tb07102.x

Dutta, M., and Ghosh, A. N. (2007). Physicochemical characterisation of El Tor vibriophages S20. Intervirology 50, 264–272. doi: 10.1159/000102469

Ellingsen, A. B., Jørgensen, H., Wagley, S., Monshaugen, M., and Rørvik, L. M. (2008). Genetic diversity among Norwegian Vibrio parahaemolyticus. J. Appl. Microbiol. 105, 2195–2202. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2008.03964.x

El-Sahn, M. A., El-Banna, A. A., and Shehata, A. M. E. (1982). Occurrence of Vibrio parahaemolyticus in selected marine invertebrates, sediments, and seawater around Alexandria, Egypt. Can. J. Microbiol. 28, 1261–1264. doi: 10.1139/m82-187

Feldhusen, F. (2000). The role of seafood in bacterial foodborne diseases. Microbes Infect. 2, 1651–1660. doi: 10.1016/S1286-4579(00)01321-6

Fiorentin, L., Vieira, N. D., and Barioni, W. Jr. (2005). Oral treatment with bacteriophages reduces the concentration of Salmonella Enteritidis PT4 in caecal contents of broilers. Avian Pathol. 34, 258–263. doi: 10.1080/01445340500112157

Fortuna, W., Miedzybrodzki, R., Weber-Dabrowska, B., and Górski, A. (2008). Bacteriophage therapy in children: facts and prospects. Med. Sci. Monit. 14, 126–132.

Fox, J. L. (2005). Therapy with phage: mirage or potential barrage of products? ASM News 71, 453–455.

Gonzalez-Escalona, N., Cachicas, V., Acevedo, C., Rioseco, M. L., Vergara, J. A., Cabello, F., et al. (2005). Vibrio parahaemolyticus diarrhoea in Chile - 1998 and 2004. Emerging Infect. Dis. 11, 129–131. doi: 10.3201/eid1101.040762

Greer, G. G., and Dilts, B. D. (1990). Inability of a bacteriophage pool to control beef spoilage. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 10, 331–342.

Guenther, S., Herzig, O., Fieseler, L., Klumpp, J., and Loessner, M. J. (2012). Biocontrol of Salmonella Typhimurium in RTE foods with the virulent bacteriophage FO1-E2. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 154, 66–72. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2011.12.023

Guenther, S., and Loessner, M. J. (2011). Bacteriophage biocontrol of Listeria monocytogenes on soft-ripened white mold and red-smear cheeses. Bacteriophage 1, 94–100. doi: 10.4161/bact.1.2.15662

Gutierrez West, C. K., Klein, S. L., and Lovell, C. R. (2013). High frequency of virulence factor genes tdh, trh, and tlh in Vibrio parahaemolyticus strains isolated from a pristine estuary. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 79, 2247–2252. doi: 10.1128/AEM.03792-12

Hagens, S., and Loessner, M. J. (2010). Bacteriophage for biocontrol of foodborne pathogens: calculations and considerations. Curr. Pharm. Biotechnol. 11, 58–68. doi: 10.2174/138920110790725429

Hara-Kudo, Y., Nishina, T., Nakagawa, H., Konuma, H., Hasegawa, J., and Kumagai, S. (2001). Improved method for the detection of Vibrio parahaemolyticus in seafood. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67, 5819–5823. doi: 10.1128/AEM.67.12.5819-5823.2001

Harper, D. R. (2006). Biological Control by Microorganisms. The Encyclopaedia of Life Sciences. Chichester: John Wiley and Sons.

Harth, E., Matsuda, L., Hernández, C., Rioseco, M. L., Romero, J., González-Escalona, N., et al. (2009). Epidemiology of Vibrio parahaemolyticus outbreaks, southern Chile. Emerging Infect. Dis. 15, 163–168. doi: 10.3201/eid1502.071269

Hazen, T. H., Lafon, P. C., Garrett, N. M., Lowe, T. M., Silberger, D. J., Rowe, L. A., et al. (2015). Insights into the environmental reservoir of pathogenic Vibrio parahaemolyticus using comparative genomics. Front. Microbiol. 6:204. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2015.00204.

Hidaka, T. (1973). Characterisation of Marine Bacteriophages Newly Isolated. Memoirs of the Faculty of Fisheries, Kagoshima University, 47–61.

Hidaka, T., and Tokushige, A. (1978). Isolation and Characterisation of Vibrio parahaemolyticus Bacteriophages in Seawater. Memoirs of the Faculty of Fisheries, Kagoshima University, 79–90.

Honda, T., and Iida, T. (1993). The pathogenicity of Vibrio parahaemolyticus and the role of the thermostable direct haemolysin and related haemolysins. Rev. Med. Microbiol. 4, 106–113. doi: 10.1097/00013542-199304000-00006

Hong, Y., Choi, S. T., Lee, B. H., and Conway, W. S. (2015). Combining of bacteriophage and G. asaii application to reduce L. monocytogenes on honeydew melon pieces. Food Technol. 3, 115–122.

Hungaro, H. M., Mendonça, R. C. S., Gouvêa, D. M., Vanetti, M. C. D., and de Oliveira Pinto, C. L. (2013). Use of bacteriophages to reduce Salmonella in chicken skin in comparison with chemical agents. Food Res. Int. 52, 75–81. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2013.02.032

Jacquet, S., Miki, T., Noble, R., Peduzzi, P., and Wilhelm, S. (2010). Viruses in aquatic ecosystems: important advancements of the last 20 years and prospects for the future in the field of microbial oceanography and limnology. Adv. Oceanogr. Limnol. 1, 97–141. doi: 10.4081/aiol.2010.5297

Ji, H., Chen, Y., Guo, Y., Liu, X., Wen, J., and Liu, H. (2011). Occurrence and characteristics of Vibrio vulnificus in retail marine shrimp in China. Food Control 22, 1935–1940. doi: 10.1016/j.foodcont.2011.05.006

Johnson, C. N., Bowers, J. C., Griffitt, K. J., Molina, V., Clostio, R. W., Pei, S., et al. (2012). Ecology of Vibrio parahaemolyticus and Vibrio vulnificus in the Coastal and Estuarine Waters of Louisiana, Maryland, Mississippi, and Washington (United States). Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 78, 7249–7257. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01296-12

Johnson, P. T. (1968). A new medium for maintenance of marine bacteria. J. Invert. Pathol. 11:144. doi: 10.1016/0022-2011(68)90065-7

Johnson, R. P., Gyles, C. L., Huff, W. E., Ojha, S., Huff, G. R., Rath, N. C., et al. (2008). Bacteriophages for prophylaxis and therapy in cattle, poultry and pigs. Anim. Health Res. Rev. 9, 201–215. doi: 10.1017/S1466252308001576

Joseph, S. W., Colwell, R. R., and Kaper, J. B. (1982). Vibrio parahaemolyticus and related halophilic Vibrios. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 10, 77–124. doi: 10.3109/10408418209113506

Jun, J. W., Kim, J. H., Shin, S. P., Han, J. E., Chai, J. Y., and Park, S. C. (2013). Protective effects of the Aeromonas phages pAh1-C and pAh6-C against mass mortality of the cyprinid loach (Misgurnus anguillicaudatus) caused by Aeromonas hydrophila. Aquaculture 416–417, 289–295. doi: 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2013.09.045

Jurczak-Kurek, A., Gasior, T., Nejman-Falenczyk, B., Bloch, S., Dydecka, A., Topka, G., et al. (2016). Biodiversity of bacteriophages: morphological and biological properties of a large group of phages isolated from urban sewage. Sci. Rep. 6:34338. doi: 10.1038/srep34338

Kaneko, T., and Colwell, R. R. (1973). Ecology of Vibrio parahaemolyticus in Chesapeake Bay. J. Bacteriol. 113, 24–32.

Kaneko, T., and Colwell, R. R. (1975). Incidence of Vibrio parahaemolyticus in Chesapeake Bay. Appl. Microbiol. 30, 251–257.

Kasman, L. M., Kasman, A., Westwater, C., Dolan, J., Schmidt, M. G., and Norris, J. S. (2002). Overcoming the phage replication threshold : a mathematical model with implications for phage therapy. J. Virol. 76, 5557–5564. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.11.5557-5564.2002

Kennedy, J. E. J., and Bitton, G. (1987). “Bacteriophages in foods,” in Phage Ecology, eds S. M. Goyal, C. P. Gerba, and G. Bitton (New York, NY: John Wiley and Sons), 289–316.

Khan, A. A., McCarthy, S., Wang, R. F., and Cerniglia, C. E. (2002). Characterization of United States outbreak isolates of Vibrio parahaemolyticus using enterobacterial repetitive intergenic consensus (ERIC) PCR and development of a rapid PCR method for detection of O3:K6 isolates. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 206, 209–214. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2002.tb11011.x

Laemmli, U. K. (1970). Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature 227, 680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0

Letchumanan, V., Chan, K. G., Pusparajah, P., Saokaew, S., Duangjai, A., Goh, B. H., et al. (2016). Insights into bacteriophage application in controlling Vibrio species. Front. Microbiol. 19:1114. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.01114

Letchumanan, V., Chan, K. G., and Lee, L. H. (2014). Vibrio parahaemolyticus: a review on the pathogenesis, prevalence and advance molecular identification techniques. Front. Microbiol. 5:705. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2014.00705

Letchumanan, V., Yin, W. F., Lee, L. H., and Chan, K. G. (2015). Prevalence and antimicrobial susceptibility of Vibrio parahaemolyticus isolated from retail shrimps in Malaysia. Front. Microbiol. 6:33. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2015.00033

Leverentz, B., Conway, W. S., Alavidze, Z., Janisiewicz, W. J., Fuchs, Y., Camp, M. J., et al. (2001). Examination of bacteriophage as a biocontrol method for Salmonella on fresh-cut fruit: a model study. J. Food Prot. 64, 1116–1121. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X-64.8.1116

Leverentz, B., Conway, W. S., Camp, M. J., Janisiewicz, W. J., Abuladze, T., Yang, M., et al. (2003). Biocontrol of Listeria monocytogenes on fresh-cut produce by treatment with lytic bacteriophages and a bacteriocin. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69, 4519–4526. doi: 10.1128/AEM.69.8.4519-4526.2003

Leverentz, B., Conway, W. S., Janiswicz, W. J., and Camp, M. J. (2004). Optimising concentration and timing of phage spray application to reduce Listeria monocytogenes on honeydew melon tissue. J. Food Prot. 67, 1682–1686. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X-67.8.1682

Li, H., Tang, R., Lou, Y., Cui, Z., Chen, W., Hong, Q., et al. (2017). A comprehensive epidemiological research for clinical Vibrio parahaemolyticus in Shanghai. Front. Microbiol. 8:1043. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.01043

Lindberg, A. A. (1967). Studies of a receptor for Felix O-1 phage in Salmonella minnesota. J. Gen. Microbiol. 48, 225–233. doi: 10.1099/00221287-48-2-225

Madsen, L., Bertelsen, S. K., Dalsgaard, I., and Middleboe, M. (2013). Dispersal and survival of Flavobacterium psychrophilum phages in vivo in rainbow trout and in vitro under laboratory conditions: implications for their use in phage therapy. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 79, 4853–4861. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00509-13

Malcolm, T. T. H., Cheah, Y. K., Radzi, C. W. J. W.M., Kasim, F. A., Kantilal, H. K., John, T. Y. H., et al. (2015). Detection and quantification of pathogenic Vibrio parahaemolyticus in shellfish by using multiplex PCR and loop-mediated isothermal amplification assay. Food Control 47, 664–671. doi: 10.1016/j.foodcont.2014.08.010

Martinez-Urtaza, J., Lozano-Leon, A., Varela-Pet, J., Trinanes, J., Pazos, Y., and Garcia-Martin, O. (2008). Environmental determinants of the occurrence and distribution of Vibrio parahaemolyticus in the rias of Galicia, Spain. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 74, 265–274. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01307-07

McIntyre, L., Hudson, J. A., Billington, C., and Withers, H. (2007). Biocontrol of foodborne bacteria: past, present and future strategies. Food N. Z. Sci. Rev. Art. 7, 25–32.

McLaughlin, J. B., DePaola, A., Bopp, C. A., Martinek, K. A., Napolilli, N. P., Allison, C. G., et al. (2005). Outbreak of Vibrio parahaemolyticus gastroenteritis associated with Alaskan oysters. New Engl. J. Med. 353, 1463–1470. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa051594

Mirzaei, K. M., and Nilsson, A. S. (2015). Isolation of phages for phage therapy: a comparison of spot tests and efficiency of plating analyses for determination of host range and efficacy. PLoS ONE 10:e0118557. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0118557

Modi, R., Hirvi, Y., Hill, A., and Griffiths, M. W. (2001). Effect of phage on survival of Salmonella Enteritidis during manufacture and storage of cheddar cheese made from raw and pasteurized milk. J. Food Prot. 64, 927–933. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X-64.7.927

Murray, N. (2000). Type I restriction systems: sophisticated molecular machines (a legacy of Bertani and Weigle). Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 64, 412–434.

Nakai, T., and Park, S. C. (2002). Bacteriophage therapy of infectious diseases in aquaculture. Res. Microbiol. 153, 13–18.

Nishibuchi, M., and Kaper, J. B. (1995). Thermostable direct hemolysin gene of Vibrio parahaemolyticus: a virulence gene acquired by a marine bacterium. Infect. Immun. 63, 2093–2099.

O'Flynn, G., Ross, R. P., Fitzgerald, G. F., and Coffey, A. (2004). Evaluation of a cocktail of three bacteriophages for biocontrol of Escherichia coli O157:H7. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70, 3417–3424. doi: 10.1128/AEM.70.6.3417-3424.2004

Paranjpye, R. N., Nilsson, W. B., Liermann, M., Hilborn, E. D., George, B. J., Li, Q., et al. (2015). Environmental influences on the seasonal distribution of Vibrio parahaemolyticus in the Pacific Northwest of the USA. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 91, 1–12. doi: 10.1093/femsec/fiv121