- Photobiology Unit, Dermatology Department, Ninewells Hospital, University of Dundee School of Medicine, Dundee, United Kingdom

Narrowband UVB (NB-UVB) phototherapy and psoralen-UVA (PUVA) photochemotherapy are widely used phototherapeutic modalities for a range of skin diseases. The main indication for NB-UVB and PUVA therapies is psoriasis, and other key diagnoses include atopic eczema, vitiligo, cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL), and the photodermatoses. The decision on choice of phototherapy is important and NB-UVB is usually the primary choice. NB-UVB phototherapy is a safe and effective therapy which is usually considered when topical agents have failed. PUVA requires prior psoralen sensitization but remains a highly effective mainstay therapy, often used when NB-UVB fails, there is rapid relapse following NB-UVB or in specific indications, such as pustular or erythrodermic psoriasis. This review will provide a perspective on the main indications for use of NB-UVB and PUVA therapies and provide comparative information on these important dermatological treatments.

Introduction

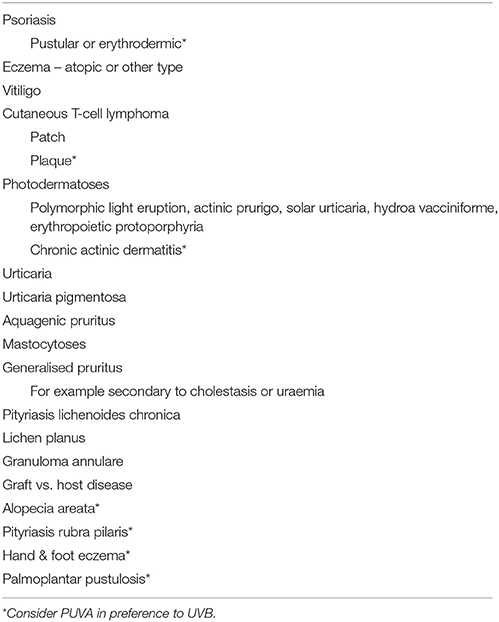

Narrowband UVB (NB-UVB) phototherapy and psoralen-UVA (PUVA) photochemotherapy are widely used light-based treatments for a range of diverse skin diseases and can be highly effective, well-tolerated, safe, cost-saving, and reduce the need for topical therapies (1–6). The main indication for NB-UVB or PUVA is psoriasis (7) but other mainstay indications include atopic dermatitis or dermatitis of other cause, vitiligo, cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL), and a range of other conditions, including the photodermatoses, pityriasis rubra pilaris, urticaria, aquagenic pruritus, urticaria pigmentosum, pityriasis lichenoides, lichen planus, granuloma annulare, alopecia areata, and graft vs. host disease (2, 3, 5, 6) (Table 1).

If topical treatments fail to establish adequate control of disease then a light-based therapy would be a next appropriate treatment choice and in most instances NB-UVB would be selected as the primary phototherapeutic option. However, in certain diseases such as erythrodermic or pustular psoriasis, pityriasis rubra pilaris, or plaque stage CTCL, PUVA would be the desired option (5).

I am going to provide my opinion and perspective on the relative uses of NB-UVB and PUVA for a range of diseases, with particular emphasis on psoriasis as the predominant indication for a UV-light based therapy and with briefer mention on the salient points relative to the use of NB-UVB and PUVA in other conditions. I am restricting my review to NB-UVB and PUVA and am not including BB-UVB or UVA1 phototherapies.

Background

UVB was introduced into increasingly widespread and routine use following developmental work in the 1980s (8–11). NB-UVB phototherapy reduces the need for topical therapies (1) and is a cost effective (12) and safe treatment, which involves repeated controlled delivery of the narrowband region of the UVB spectrum centered on 311 nm (4, 6). The main acute adverse effects of NB-UVB are erythema and induction of photosensitivity diseases, such as polymorphic light eruption (PLE). However, although the risk of erythemal episodes may be increased by concomitant phototoxic drugs (13, 14), this can be minimized by undertaking a baseline minimal erythema dose (MED) and establishing treatment protocols based on an individual's MED (15). This also allows any unsuspected abnormal photosensitivity diseases to be detected, in particular solar urticaria or chronic actinic dermatitis (CAD). Induction of PLE may occur during a treatment course but generally can be accommodated via dose adjustments and judicious use of topical corticosteroid, without the need to stop NB-UVB (16). Other uncommon side-effects, such as psoriatic lesional blistering, occasionally occur but generally treatment is very well-tolerated (17, 18). Importantly, NB-UVB can be safely used in children and in pregnancy and long-term studies to date do not indicate a significantly increased risk of skin cancer over an age- and sex-matched control population who have not received UVB phototherapy (19–21).

PUVA photochemotherapy is delivered using psoralen administration via either systemic (8-methoxypsoralen or 5-methoxypsoralen) or topical (usually now 8-methoxypsoralen as bath, soak, gel, cream, or lotion) routes (5). The mechanism of action of PUVA is quite distinct from that of UVB or of UVA alone, with PUVA inducing a delayed erythemal reaction peaking around 96 h after irradiation of psoralen-sensitized skin (22–27). This contrasts with the peak time for development of erythema after NB-UVB exposure of 12–24 h (28). Treatment is thus logistically slightly more of a challenge as psoralen sensitization is required. With systemic PUVA, appropriate skin and eye protection must be used for 24 h after psoralen ingestion. Oral 8-methoxypsoralen may cause some gastrointestinal upset, although switching to 5-methoxypsoralen minimizes this adverse effect and of course this is not an issue with topical PUVA. However, PUVA treatment can be highly effective and very safely administered in any Dermatology Department with a significantly sized Phototherapy Unit.

With the exception of less common adverse effects such as PUVA pain, treatment is otherwise usually well-tolerated (5). Undoubtedly, there is a longer term risk of skin carcinogenesis with high numbers of PUVA exposures (19, 29–37), but the risks can be minimized by vigilance, limitation of lifetime numbers of PUVA exposures, and avoidance of the use of maintenance PUVA where possible. As with all therapeutic approaches, benefit, and risk must be evaluated and it is important that PUVA is kept firmly in the range of treatment options as it can be highly effective, resulting in clearance, and marked improvement in quality of life for patients with psoriasis and a variety of other diseases.

It is essential that adequate governance is ensured for the safe delivery of both NB-UVB and PUVA therapies. In Scotland we have established the National Managed Clinical Network for phototherapy (Photonet; www.photonet.scot.nhs.uk), which employs a central database (Photosys), enabling standardization of treatment protocols, recording of treatment parameters, and outcomes and facilitating linkage studies to ascertain longer-term risks of treatment, notably skin cancer risk (20, 21). This has been an invaluable asset to allow standardization of phototherapy services in Scotland and delivery of effective and safe treatment for patients. This approach is now being adopted in England and has important roles in delivery of optimized safe care.

Psoriasis

The main indication for any light-based therapy is psoriasis, and for the reasons highlighted in terms of practicalities and ease of treatment and its safety and potential for use in children and pregnancy, NB-UVB phototherapy would usually be the light-based therapy of choice, with high clearance rates achieved for chronic plaque psoriasis (6, 38–40).

In an initial controlled comparative half-body study in 10 patients with widespread psoriasis, no significant difference in efficacy was seen between twice weekly NB-UVB or systemic PUVA (41) and this observation was also reported in a separate intra-individual open non-randomized controlled paired comparison study of three times weekly NB-UVB and PUVA, with no significant difference in efficacy seen between the treatment arms. However, there was a trend to superior efficacy with PUVA and this was particularly evident for patients with a higher baseline PASI score (42), possibly suggestive of a role for PUVA in more severe psoriasis or relapsing psoriasis, although given the convenience of NB-UVB this would generally be the preferred initial approach. In a separate inter-individual study of 100 patients with psoriasis, twice weekly PUVA was superior in efficacy to twice-weekly NB-UVB, with 35% of patients still being clear at 6 months after completion of PUVA, compared with only 12% after NB-UVB (43). These findings are supported by those of a separate study in which 93 patients with chronic plaque psoriasis were randomized to receive either twice-weekly oral PUVA or twice-weekly NB-UVB, resulting in 84% achieving clearance with PUVA compared with significantly lower clearance rates (65%) with NB-UVB and shorter remission, as 6 months after treatment 68% of those treated with PUVA were still in remission, compared with only 35% of patients treated with NB-UVB (44). Of note, lower clearance rates were achieved in patients of skin phototype V and VI, with only 24% achieving clearance, although baseline psoriasis severity was not a determinant of response in this study (44). However, high efficacy rates have been reported in patients of higher skin phototypes (IV and V), with 81–82% of patients showing marked improvement with three times weekly 8-MOP PUVA or NB-UVB and no difference between the two treatment regimens, indicating that phototherapy or photochemotherapy should certainly still be considered for patients with higher skin phototypes (45).

Given that three-times weekly NB-UVB results in faster more efficient clearance of psoriasis than twice-weekly treatment (46), comparison of twice weekly PUVA with a twice-weekly NB-UVB regimen is likely to be including a sub-optimal NB-UVB treatment arm. Indeed, in an intra-individual randomized controlled study of three times weekly NB-UVB with twice-weekly TMP bath PUVA, NB-UVB was of superior efficacy and also resulted in more rapid response of psoriasis, with 75% clearance compared with 54% with PUVA (40). Additionally, in a randomized intra-individual half-side study in patients with chronic plaque psoriasis, comparing three times weekly TMP bath PUVA and three times weekly NB-UVB, again NB-UVB was of superior efficacy compared with TMP bath PUVA, although all patients relapsed within 4 months of follow-up (47). In contrast, Salem et al., undertook a randomized controlled trial in 34 patients, comparing 8-MOP bath PUVA three times a week with three times weekly NB-UVB and greater reduction in PASI score was seen with PUVA than NB-UVB, along with greater reduction in peripheral CD4+ T Cells, indicative of possible systemic effects (48). Furthermore, Markham et al., undertook an open randomized inter-individual comparative study of twice-weekly oral 8-MOP PUVA with three times weekly NB-UVB for chronic plaque psoriasis and showed equivalent efficacy in terms of time to clearance and period of remission (49).

Thus, trying to make sensible conclusions from this diverse range of study findings, given the ease, convenience, and safety of treatment and the study evidence, NB-UVB should usually be considered as the first phototherapeutic option for patients with chronic plaque psoriasis, with PUVA used when NB-UVB is not effective or there is rapid relapse once NB-UVB is discontinued (39). A lower threshold for considering PUVA is reasonable if psoriasis is particularly thick and/or extensive at baseline, including erythrodermic and pustular psoriasis (50) or the patient is of higher skin phototype. In addition, 8-MOP bath or oral PUVA may be preferable to TMP bath PUVA, as although no head to head comparison has been undertaken, lower response rates are reported for those studies using TMP bath PUVA rather than 8-MOP (40, 47–49). Erythemogenic doses of PUVA are not a pre-requisite for clearance (51) and maintenance PUVA or NB-UVB for psoriasis should generally be avoided (52). Failure to respond to NB-UVB does not equate to prediction of a lack of response to PUVA and the latter should be considered for those who fail to do well with NB-UVB. For children, NB-UVB phototherapy is preferred and PUVA is relatively contraindicated, although this is not an absolute rule, but given the concerns about long-term safety, PUVA would not be the first line choice.

Eczema

Whilst any light-based treatment approach is less straightforward for eczema than psoriasis, not least for the reason of flaring of eczema in the early stages of treatment mainly due to the heat load of therapy, both NB-UVB and PUVA can be highly effective for the treatment of atopic eczema and other forms of eczema (5, 6). However, the evidence-base is relatively weak and there are no prospective studies comparing head-to-head systemic PUVA with NB-UVB (53). Systemic 5-MOP PUVA was shown to be superior to medium dose UVA1 for atopic eczema in an intra-individual randomized controlled comparison study (54). Bath PUVA can also be highly effective for atopic eczema (55). Bath PUVA using 8-MOP was compared with NB-UVB in a small half-side comparison study, showing that both were effective for severe atopic eczema without a significant difference between the two therapies (56). Thus, NB-UVB would usually be the first line of choice for atopic eczema, given the ease of administration, safety, and potential for use in children (57). Given the response of atopic eczema to several types of light-based therapy and if NB-UVB phototherapy fails or there is early relapse after discontinuation of treatment, then the options of either PUVA or UVA1 exist, although given the lack of evidence of superiority of UVA1, the latter would likely only be considered if PUVA was contraindicated. Indeed, a combination of NB-UVB and UVA or UVA1 could be considered for some patients, although whether this is advantageous compared with UVB alone is unclear and this needs further study (58).

Vitiligo

For the treatment of vitiligo, NB-UVB has been shown to be superior to PUVA with respect to rates of repigmentation, particularly for unstable extensive vitiligo, and in achieving more cosmetically acceptable even repigmentation (59–63). Thus, NB-UVB would be the phototherapy of choice for vitiligo, although PUVA may be considered in certain cases, particularly if there is lack of response to NB-UVB.

Cutaneous T-Cell Lymphoma

Whilst there are no direct head-to-head controlled trials of NB-UVB and PUVA for early stage CTCL, both have been shown to be effective for this stage of disease (5, 64). In one retrospective study 81% of patients with early stage CTCL achieved complete remission with NB-UVB, compared with 71% with PUVA (n = 56) (65). This observation has also been supported by two other studies showing equivalent efficacy for NB-UVB and PUVA in achieving remission of early stage CTCL (66, 67) and thus NB-UVB should be the phototherapy of choice for early patch stage CTCL disease, with complete remission in approximately three quarters of patients being achievable, although duration of remission has not been thoroughly evaluated and relapse may occur within 6 months (68). It is unclear whether phototherapy has any impact on limiting natural disease progression. Based on one study it was suggested that tumor stage CTCL was slower to develop and overall survival was improved in those who had previously received phototherapy, although given the retrospective nature of the study these data must not be obver-interpreted (69). For thicker plaque stage CTCL, the increased depth of penetration of PUVA is desirable and NB-UVB would not be indicated, whereas PUVA would be the phototherapeutic modality of choice (5). For tumor stage disease, PUVA as monotherapy would not suffice and combination therapy is likely to be required. Maintenance PUVA should generally be avoided, but occasionally is justified for maintenance use in CTCL (5, 70). However, other adjunctive agents should be considered and combination with retinoids, rexinoids, or interferon may be required or the use of radiotherapy for localized tumor stage disease or total skin electron beam treatment for more extensive involvement (5). Photopheresis may of course be required for Sezary syndrome (71, 72). Thus, in summary NB-UVB for early stage disease and PUVA for plaque stage disease as monotherapy or in combination therapy for more advanced disease should be considered as mainstays in management (5, 64, 73).

The Photodermatoses

There is a relative lack of randomized controlled trial evidence investigating the use of NB-UVB and PUVA for the abnormal photosensitivity conditions. However, for desensitization of PLE, comparative studies show equivalent efficacy for NB-UVB and PUVA (16). As regular annual desensitization courses may be required from a relatively young age, NB-UVB is preferred for PLE as the phototherapy of choice, although PUVA should be considered for treatment failures and when reported its use may be for more severe PLE (74, 75). Induction of PLE during treatment is common and to be expected but does not usually require early termination of the desensitization course and can usually be accommodated with reduction of dose increments and topical corticosteroid use during the treatment course (16, 76). With the other less common photodermatoses, desensitization phototherapies with either NB-UVB or PUVA may be considered and appropriate but will depend on the action spectrum for induction of abnormal photosensitivity and thus which light-based treatment approach can be tolerated. In general, these patients should be investigated and managed through a specialist photodermatology unit as there may be additional needs, such as inpatient requirements for suppression and light-protected care and advice regarding subsequent natural sunlight top up exposure. In CAD, the action spectrum for induction of abnormal photosensitivity is usually maximal in the UVB region and therefore NB-UVB phototherapy cannot often be tolerated. In this setting PUVA may need to be considered, sometimes in combination with topical superpotent or systemic corticosteroids in order to reduce the risk of disease flare, particularly in the early stages of treatment (77, 78).

NB-UVB and PUVA may also be useful therapeutic approaches for the other photodermatoses, such as erythropoietic protoporphyria, hydroa vacciniforme, actinic prurigo, and idiopathic solar urticaria (79). Indeed, in solar urticaria the action spectrum for induction of urticaria is usually in the UVA and visible parts of the spectrum and NB-UVB responses are typically normal, in which case NB-UVB desensitization can be used successfully for desensitization, with UVA rush hardening and/or PUVA considered if NB-UVB is not feasible or successful (79–84).

It would generally also be advisable for patients with solar urticaria to have anti-histamine cover whilst receiving a UV-based therapy. In EPP, as photosensitivity is maximal in the visible part of the spectrum, NB-UVB is usually well-tolerated and can be highly effective and is the phototherapy of choice. Whilst here is limited evidence to support the use of PUVA, given that patients with EPP will usually require annual treatment courses from a young age, NB-UVB is advised and PUVA is rarely justified (85–88). Similarly, whilst there is limited evidence to support the use of NB-UVB and PUVA in actinic prurigo, again given the young age and need for annual treatment, NB-UVB is advised and PUVA rarely needed, although may occasionally be required (79). Factors such as the age of the patient, risk factors such as skin phototype and evidence of photodamage and the action spectrum for induction of abnormal photosensitivity, should always be taken into account in any decision regarding NB-UVB or PUVA and for the photodermatoses, specialist advice regarding timing of desensitization courses, risk of induction of the condition by treatment and management of that, top-up exposure requirements after treatment and the need for annual treatment courses must be addressed in order to establish the optimal approach for any given patient.

Localized Hand and Foot Disease

Hand and foot dermatoses are a mixed group of conditions, which include hyperkeratotic eczema, psoriasis, psoriasiform dermatitis, palmoplantar pustulosis. There is a lack of robust evidence regarding the optimal management of these diseases, including the role of NB-UVB and PUVA therapies and there is no reason to consider that one approach will suit all conditions. Undoubtedly, NB-UVB and PUVA photochemotherapy may be useful for localized hand and foot dermatoses (89). Although oral PUVA and NB-UVB may both be effective for eczema of the palms and soles, oral PUVA has been shown to be superior to NB-UVB in two small studies from the same group, although relapse rates were high following both treatments (5, 90, 91). The depth of penetration of 8-MOP systemic PUVA may be desirable for recalcitrant hand and foot dermatitis and other uncontrolled studies have also shown high levels of efficacy with oral PUVA for hand and foot eczema (5, 92, 93). In contrast, topical PUVA has not been shown to be superior to placebo or any other active treatment, despite uncontrolled studies, and anecdotal observations that efficacy can be achieved and this is an area requiring further research. Thus, for hand and foot eczema, oral PUVA would be the light-based therapy of choice (5). Psoriasis of the palms and soles has been even less well evaluated and, whilst there is some evidence to support the use of PUVA, either with oral or topical psoralens, the strength of evidence is weak and further studies are required (5, 7, 94). For palmoplantar pustulosis, again oral PUVA either as monotherapy or combined with retinoids, may be highly effective (5, 95–97) and the role of NB-UV is less clear as has not been evaluated.

Other Indications

There is evidence that NB-UVB and PUVA may be effective for urticaria and indeed randomized controlled trial evidence to show the superior efficacy of NB-UVB plus anti-histamine compared with anti-histamine alone (98–100). More recently, superiority of NB-UVB compared with PUVA has been shown for urticaria (101), and thus NB-UVB should be considered as a treatment option if antihistamines and other pharmacological therapies fail and may provide useful disease remission. A range of other conditions may be effectively treated by NB-UVB and PUVA and include pityriasis lichenoides (102), granuloma annulare (103, 104), urticaria pigmentosa and cutaneous mastocytoses (105–107), aquagenic pruritus (108–110), lichen planus (111–114), alopecia areata (115–118), generalized pruritus, such as secondary to uraemia or cholestasis (119, 120), and graft vs. host disease (2, 3, 5, 6) and these phototherapeutic modalities may be invaluable treatment approaches for these otherwise difficult-to-treat groups of diseases. For conditions such as pityriasis rubra pilaris, which may be aggravated and flared by the use of NB-UVB, 8-MOP systemic PUVA should be considered.

Conclusions

To summarize, NB-UVB phototherapy and PUVA photochemotherapy are both invaluable treatments to have available in any dermatology department and should be prioritized, not only for psoriasis, but in a variety of other inflammatory and proliferative skin diseases, including atopic eczema. Treatment can be safely and easily administered and is well tolerated with few adverse effects. Excellent disease remission may be achieved, whilst sparing the use of other potentially toxic drugs at a relatively early stage in a patient's journey. Head-to-head comparative monotherapy studies with biologic therapies do not exist and are needed. Due to the relative cost-efficacy of the phototherapies and the understanding of their long-term safety profiles compared with the cost and less lengthy follow-up for the biologics, these should be employed prior to consideration of biologic treatments (1). As with any therapy, standardization of optimized treatment regimens, careful observation of treatments delivered and therapeutic outcomes, adverse effects and long-term follow-up studies, including determining any skin cancer risk, are essential. The development of the National Managed Clinical Network for Phototherapy has had a major impact on standardization, safety, and vigilance in delivery of our phototherapy practices in Scotland and has proved to be an invaluable tool, enabling the place of NB-UVB, and PUVA therapies to continue to be well-established in the treatment of skin disease.

Author Contributions

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and approved it for publication.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The reviewer FL and the handling Editor declared their shared affiliation.

References

1. Foerster J, Boswell K, West J, Cameron H, Fleming C, Ibbotson S, et al. Narrowband UVB treatment is highly effective and causes a strong reduction in the use of steroid and other creams in psoriasis patients in clinical practice. PLoS ONE (2017) 12:e0181813. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0181813

2. Norris PG, Hawk JLM, Baker C, Bilsland D, Diffey BL, Farr PM, et al. British Photodermatology Group Guidelines for PUVA. Br J Dermatol. (1994) 130:246–55. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1994.tb02910.x

3. Halpern SM, Anstey AV, Dawe RS, Diffey BL, Farr PM, Ferguson J, et al. Guidelines for topical PUVA: a report of a workshop of the British Photodermatology Group. Br J Dermatol. (2000) 142:22–31. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.2000.03237.x

4. Bilsland D, Dawe R, Diffey BL, Farr P, Ferguson J, George S, et al. An appraisal of narrowband (TL-01) UVB phototherapy. British photodermatology group workshop report (April 1996). Br J Dermatol. (1997) 137:327–30. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.1997.18441939.x

5. Ling TC, Clayton TH, Crawley J, Exton LS, Goulden V, Ibbotson S, et al. British Association of Dermatologists and British photodermatology group guidelines for the safe and effective use of psoralen-ultraviolet a therapy 2015. Br J Dermatol. (2016) 174:24–55. doi: 10.1111/bjd.14317

6. Ibbotson SH, Bilsland D, Cox NH, Dawe RS, Diffey B, Edwards C, et al. An update and guidance on narrowband ultraviolet B phototherapy: a British photodermatology group workshop report. Br J Dermatol. (2004) 151:283–97. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2004.06128.x

7. Chen X, Yang M, Cheng Y, Liu GJ, Zhang M. Narrow-band ultraviolet B phototherapy versus broad-band ultraviolet B or psoralen-ultraviolet A photochemotherapy for psoriasis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (2013) CD009481. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009481.pub2

8. Van Weelden H, De La Faille HB, Young E, Van Der Leun JC. A new development in UVB phototherapy of psoriasis. Br J Dermatol. (1988) 119:11–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1988.tb07096.x

9. Green C, Ferguson J, Lakshmipathi T, Johnson BE. 3II-Nm Uvb phototherapy - An effective treatment for psoriasis. Br J Dermatol. (1988) 119:691–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1988.tb03489.x

10. Karvonen J, Kokkonen EL, Ruotsalainen E. 311-nm UVB lamps in the treatment of psoriasis with the Ingram regime. Acta Derm Venereol. (1989) 69:82–5

12. Boswell K, Cameron H, West J, Fleming C, Ibbotson S, Dawe R, et al. Narrowband-UVB treatment for psoriasis is highly economical and causes significant savings in cost for topical treatments. Br J Dermatol. (2018) doi: 10.1111/bjd.16716. [Epub ahead of print].

13. Cameron H, Dawe RS. Photosensitizing drugs may lower the narrow-band ultraviolet B (TL-01) minimal erythema dose. Br J Dermatol. (2000) 142:389–90. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.2000.03325.x

14. Harrop G, Dawe RS, Ibbotson S. Are photosensitising medications associated with increased risk of important erythemal reactions during UVB phototherapy? Br J Dermatol. (2018). doi: 10.1111/bjd.16800. [Epub ahead of print].

15. Dawe RS, Cameron HM, Yule S, Ibbotson SH, Moseley HH, Ferguson J. A randomized comparison of methods of selecting narrowband UV-B starting dose to treat chronic psoriasis. Arch Dermatol. (2011) 147:168–74. doi: 10.1001/archdermatol.2010.286

16. Man I, Dawe RS, Ferguson J. Artificial hardening for polymorphic light eruption: Practical points from ten years' experience. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. (1999) 15:96–99. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0781.1999.tb00066.x

17. Calzavara-Pinton PG, Zane C, Candiago E, Facchetti F. Blisters on psoriatic lesions treated with TL-01 lamps. Dermatology (2000) 200:115–9. doi: 10.1159/000018342

18. George SA, Ferguson J. Lesional blistering following narrowband (TL-01) UVB phototherapy for psoriasis: a report of four cases. Br J Dermatol. (1992) 127:445–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1992.tb00470.x

19. Archier E, Devaux S, Castela E, Gallini A, Aubin F, Le Maitre M, et al. Carcinogenic risks of psoralen UV-A therapy and narrowband UV-B therapy in chronic plaque psoriasis: a systematic literature review. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. (2012a) 26:(Suppl. 3), 22–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2012.04520.x

20. Man I, Crombie IK, Dawe RS, Ibbotson SH, Ferguson J. The photocarcinogenic risk of narrowband UVB (TL-01) phototherapy: early follow-up data. Br J Dermatol. (2005) 152:755–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2005.06537.x

21. Hearn RMR, Kerr AC, Rahim KF, Ferguson J, Dawe RS. Incidence of skin cancers in 3867 patients treated with narrow-band ultraviolet B phototherapy. Br J Dermatol. (2008) 159:931–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2008.08776.x

22. Behrens-Williams S, Gruss C, Grundmann-Kollmann M, Peter RU, Kerscher M. Assessment of minimal phototoxic dose following 8- methoxypsoralen bath: maximal reaction on average after 5 days. Br J Dermatol. (2000) 142:112–5. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.2000.03250.x

23. Grundmann-Kollmann M, Leiter U, Behrens S, Gottlober P, Mooser G, Krahn G, et al. The time course of phototoxicity of topical PUVA: 8- methoxypsoralen cream-PUVA vs. 8-methoxypsoralen gel-PUVA. Br J Dermatol. (1999) 140:988–90. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.1999.02855.x

24. Berroeta L, Attili S, Wong A, Man I, Dawe RS, Ferguson J, et al. Time course for development of psoralen plus ultraviolet a erythema following oral administration of 5-methoxypsoralen. Br J Dermatol. (2009) 160:717–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2008.09007.x

25. Kerscher M, Gruss C, Von Kobyletzki G, Volkenandt M, Neumann NJ, Altmeyer P, et al. Time course of 8-MOP-induced skin photosensitization in PUVA bath photochemotherapy. Br J Dermatol. (1997) 136:473–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1997.tb14978.x

26. Ibbotson SH, Farr PM. The time-course of psoralen ultraviolet a (PUVA) erythema. J Invest Dermatol. (1999) 113:346–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.1999.00700.x

27. Man I, Kwok YK, Dawe RS, Ferguson J, Ibbotson SH. The time course of topical PUVA erythema following 15-and 5-minute methoxsalen immersion. Arch Dermatol. (2003b) 139:331–4. doi: 10.1001/archderm.139.3.331

28. Man I, Dawe RS, Ferguson J, Ibbotson SH. An intraindividual study of the characteristics of erythema induced by bath and oral methoxsalen photochemotherapy and narrowband ultraviolet B. Photochem Photobiol. (2003a) 78:55–60. doi: 10.1562/0031-8655(2003)078<0055:AISOTC>2.0.CO;2

29. Stern RS, Thibodeau LA, Kleinerman RA, Parrish JA, Fitzpatrick TB. Risk of cutaneous carcinoma in patients treated with oral methoxsalen photochemotherapy for psoriasis. N Engl J Med. (1979) 300:809–13. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197904123001501

30. Stern RS, Laird N, Melski J, Parrish JA, Fitzpatrick TB, Bleich HL. Cutaneous squamous-cell carcinoma in patients treated with PUVA. N Engl J Med. (1984) 310:1156–61. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198405033101805

31. Stern RS, Lange R. Non-melanoma skin cancer occurring in patients treated tiwh PUVA 5 to 10 years after 1st treatment. J Invest Dermatol. (1988) 91:120–4. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12464137

32. Lindelof B, Sigurgeirsson B, Tegner E, Larko O, Johannesson A, Berne B, et al. PUVA and cancer - a large-scale epidemiologic study. Lancet (1991) 338:91–3. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(91)90083-2

33. Bruynzeel I, Bergman W, Hartevelt HM, Kenter CC, Van De Velde EA, Schothorst AA, et al. ‘High single-dose' European PUVA regimen also causes an excess of non-melanoma skin cancer. Br J Dermatol. (1991) 124:49–55. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1991.tb03281.x

34. Lever LR, Farr PM. Skin cancers or premalignant lesions occur in half of high-dose PUVA patients. Br J Dermatol. (1994) 131:215–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1994.tb08494.x

35. Stern RS. The risk of melanoma in association with long-term exposure to PUVA. J Am Acad Dermatol. (2001) 44:755–61. doi: 10.1067/mjd.2001.114576

36. Stern RS, Nichols KT, Vakeva LH. Malignant melanoma in patients treated for psoriasis with methoxsalen (psoralen) and ultraviolet A radiation (PUVA). N Eng J Med. (1997) 336:1041–5. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199704103361501

37. Stern RS, Laird N. The carcinogenic risk of treatments for severe psoriasis. Cancer (1994) 73:2759–64. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19940601)73:11<2759::AID-CNCR2820731118>3.0.CO;2-C

38. Dawe RS. A quantitative review of studies comparing the efficacy of narrow-band and broad-band ultraviolet B for psoriasis. Br J Dermatol. (2003) 149:655–80. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.2003.05498.x

39. Archier E, Devaux S, Castela E, Gallini A, Aubin F, Le Maitre M, et al. Efficacy of psoralen UV-A therapy vs. narrowband UV-B therapy in chronic plaque psoriasis: a systematic literature review. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. (2012b) 26:(Suppl. 3), 11–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2012.04519.x

40. Dawe RS, Cameron H, Yule S, Man I, Wainwright NJ, Ibbotson SH, et al. A randomized controlled trial of narrowband ultraviolet B vs. bath-psoralen plus ultraviolet. A photochemotherapy for psoriasis. Br J Dermatol. (2003) 148:1194–204. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.2003.05482.x

41. Van Weelden H, De La Faille HB, Young E, Van Der Leun JC. Comparison of narrow-band UV-B phototherapy and PUVA photochemotherapy in the treatment of psoriasis. Acta Derm Venereol. (1990) 70:212–5

42. Tanew A, Radakovic-Fijan S, Schemper M, Honigsmann H. Narrowband UV-B phototherapy vs photochemotherapy in the treatment of chronic plaque-type psoriasis - A paired comparison study. Arch Dermatol. (1999b) 135:519–24. doi: 10.1001/archderm.135.5.519

43. Gordon PM, Diffey BL, Matthews JNS, Farr PM. A randomized comparison of narrow-band TL-01 phototherapy and PUVA photochemotherapy for psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. (1999) 41:728–32. doi: 10.1016/S0190-9622(99)70008-3

44. Yones SS, Palmer RA, Garibaldinos TT, Hawk JLM. Randomized double-blind trial of the treatment of chronic plaque psoriasis - efficacy of psoralen-UV-A therapy vs narrowband UV-B therapy. Arch Dermatol. (2006) 142:836–42. doi: 10.1001/archderm.142.7.836

45. Chauhan PS, Kaur I, Dogra S, De D, Kanwar AJ. Narrowband ultraviolet B versus psoralen plus ultraviolet A therapy for severe plaque psoriasis: an Indian perspective. Clin Exp Dermatol. (2011) 36:169–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.2010.03874.x

46. Cameron H, Dawe RS, Yule S, Murphy J, Ibbotson SH, Ferguson J. A randomized, observer-blinded trial of twice vs. three times weekly narrowband ultraviolet B phototherapy for chronic plaque psoriasis. Br J Dermatol. (2002) 147:973–78. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.2002.04996.x

47. Snellman E, Klimenko T, Rantanen T. Randomized half-side comparison of narrowband UVB and trimethylpsoralen bath plus UVA treatments for psoriasis. Acta Dermato Venereol. (2004) 84:132–7. doi: 10.1080/00015550310022916

48. Salem SAM, Barakat MAET, Morcos CMZM. Bath psoralen+ultraviolet A photochemotherapy vs. narrow band-ultraviolet B in psoriasis: a comparison of clinical outcome and effect on circulating T-helper and T-suppressor/cytotoxic cells. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. (2010) 26:235–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0781.2010.00525.x

49. Markham T, Rogers S, Collins P. Narrowband UV-B (TL-01) phototherapy vs oral 8-methoxypsoralen psoralen-UV-A for the treatment of chronic plaque psoriasis. Arch Dermatol. (2003) 139:325–8. doi: 10.1001/archderm.139.3.325

50. Robinson A, Van Voorhees AS, Hsu S, Korman NJ, Lebwohl MG, Bebo BF, et al. Treatment of pustular psoriasis: from the medical board of the national psoriasis foundation. J Am Acad Dermatol. (2012) 67:279–88. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2011.01.032

51. Tanew A, Ortel B, Honigsmann H. Half-side comparison of erythemogenic versus suberythemogenic UVA doses in oral photochemotherapy of psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. (1999a) 41:408–413. doi: 10.1016/S0190-9622(99)70113-1

52. Radakovic S, Seeber A, Honigsmann H, Tanew A. Failure of short-term psoralen and ultraviolet A light maintenance treatment to prevent early relapse in patients with chronic recurring plaque-type psoriasis. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. (2009) 25:90–3. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0781.2009.00413.x

53. Garritsen FM, Brouwer MWD, Limpens J, Spuls PI. Photo(chemo)therapy in the management of atopic dermatitis: an updated systematic review with implications for practice and research. Br J Dermatol. (2014) 170:501–13. doi: 10.1111/bjd.12645

54. Tzaneva S, Kittler H, Holzer G, Reljic D, Weber M, Honigsmann H, et al. 5-Methoxypsoralen plus ultraviolet (UV) A is superior to medium-dose UVA1 in the treatment of severe atopic dermatitis: a randomized crossover trial. Br J Dermatol. (2010) 162:655–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2009.09514.x

55. De Kort WJA, Van Weelden H. Bath psoralen-ultraviolet A therapy in atopic eczema. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. (2000) 14:172–4. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-3083.2000.00067.x

56. Der-Petrossian M, Seeber A, Honigsmann H, Tanew A. Half-side comparison study on the efficacy of 8-methoxypsoralen bath-PUVA versus narrow-band ultraviolet B phototherapy in patients with severe chronic atopic dermatitis. Br J Dermatol. (2000) 142:39–43. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.2000.03239.x

57. Clayton TH, Clark SM, Turner D, Goulden V. The treatment of severe atopic dermatitis in childhood with narrowband ultraviolet B phototherapy. Clin Exp Dermatol. (2007) 32:28–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.2006.02292.x

58. Fernandez-Guarino M, Aboin-Gonzalez S, Barchino L, Velazquez D, Arsuaga C, Lazaro P. Treatment of moderate and severe adult chronic atopic dermatitis with narrow-band UVB and the combination of narrow-band UVB/UVA phototherapy. Dermatol Ther. (2016) 29:19–23. doi: 10.1111/dth.12273

59. Yones SS, Der D, Palmer RA, Garibaldinos TM, Hawk JLM. Randomized double-blind trial of treatment of vitiligo. Arch Dermatol. (2007) 143:578–84. doi: 10.1001/archderm.143.5.578

60. Westerhof W, Nieuweboer-Krobotova L. Treatment of vitiligo with UV-B radiation vs topical psoralen plus UV-A. Arch Dermatol. (1997) 133:1525–8. doi: 10.1001/archderm.1997.03890480045006

61. Bhatnagar A, Kanwar AJ, Parsad D, De D. Comparison of systemic PUVA and NB-UVB in the treatment of vitiligo: an open prospective study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. (2007a) 21:638–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2006.02035.x

62. Bhatnagar A, Kanwar AJ, Parsad D, De D. Psoralen and ultraviolet A and narrow-band B in inducing stability in vitiligo, assessed by vitiligo disease activity score: an open prospective comparative study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. (2007b) 21:1381–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2007.02283.x

63. Sapam R, Agrawal S, Dhali TK. Systemic PUVA vs. narrowband UVB in the treatment of vitiligo: a randomized controlled study. Int J Dermatol. (2012) 51:1107–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2011.05454.x

64. Grandi V, Fava P, Rupoli S, Alberti Violetti S, Canafoglia L, Quaglino P, et al. Standardization of regimens in Narrowband UVB and PUVA in early stage mycosis fungoides: position paper from the Italian task force for Cutaneous Lymphomas. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. (2018) 32:683–91. doi: 10.1111/jdv.14668

65. Diederen PVMM, Van Weelden H, Sanders CJG, Toonstra J, Van Vloten WA. Narrowband UVB and psoralen-UVA in the treatment of early-stage mycosis fungoides: a retrospective study. J Am Acad Dermatol. (2003) 48:215–9. doi: 10.1067/mjd.2003.80

66. Ahmad K, Rogers S, Mcnicholas PD, Collins P. Narrowband UVB and PUVA in the treatment of mycosis fungoides: a retrospective study. Acta Derm Venereol. (2007) 87:413–7. doi: 10.2340/00015555-0283

67. El-Mofty M, El-Darouty M, Salonas M, Bosseila M, Sobeih S, Leheta T, et al. Narrow band UVB (311 nm), psoralen UVB (311 nm) and PUVA therapy in the treatment of early-stage mycosis fungoides: a right-left comparative study. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. (2005) 21:281–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0781.2005.00183.x

68. Hofer A, Cerroni L, Kerl H, Wolf P. Narrowband (311-nm) UV-B therapy for small plaque parapsoriasis and early-stage mycosis fungoides. Arch Dermatol. (1999) 135:1377–80. doi: 10.1001/archderm.135.11.1377

69. Hoot JW, Wang L, Kho T, Akilov OE. The effect of phototherapy on progression to tumors in patients with patch and plaque stage of mycosis fungoides. J Dermatol Treat. (2018) 29:272–6. doi: 10.1080/09546634.2017.1365113

70. Carter J, Zug KA. Phototherapy for cutaneous T-cell lymphoma: online survey and literature review. J Am Acad Dermatol. (2009) 60:39–50. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2008.08.043

71. Mckenna KE, Whittaker S, Rhodes LE, Taylor P, Lloyd J, Ibbotson S, et al. Evidence-based practice of photopheresis 1987–2001: a report of a workshop of the British photodermatology group and the U.K. Skin Lymphoma Group Br J Dermatol. (2006) 154:7–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2005.06857.x

72. Knobler R, Berlin G, Calzavara-Pinton P, Greinix H, Jaksch P, Laroche L, et al. Guidelines on the use of extracorporeal photopheresis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. (2014) 28:(Suppl.), 1–37. doi: 10.1111/jdv.12311

73. Olsen EA, Hodak E, Anderson T, Carter JB, Henderson M, Cooper K, et al. Guidelines for phototherapy of mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome: a consensus statement of the United States Cutaneous Lymphoma Consortium. J Am Acad Dermatol. (2016) 74:27–58. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2015.09.033

74. Mastalier U, Kerl H, Wolf P. Clinical, laboratory phototest and phototherapy findings in polymorphic light eruption: a retrospective study of 133 patients. Eur J Dermatol. (1998) 8:554–9.

75. Bilsland D, George SA, Gibbs NK, Aitchison T, Johnson BE, Ferguson J. A comparison of narrow-band phototherapy (TL-01) and photchemotherapy (PUVA) in the management of polymorphic light eruption. Br J Dermatol. (1993) 129:708–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1993.tb03337.x

76. Aslam A, Fullerton L, Ibbotson SH. Phototherapy and photochemotherapy for polymorphic light eruption desensitisation: a five year case series review from a university teaching hospital. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. (2017) 33:225–7. doi: 10.1111/phpp.12310

77. Hindson C, Downey A, Sinclair S, Cominos B. PUVA therapy of chronic actinic dermatitis - A 5-year follow-up. Br J Dermatol. (1990) 123:273. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1990.tb01869.x

78. Hindson C, Spiro J, Downey A. PUVA therapy of chronic actinic dermatitis. Br J Dermatol. (1985) 113:157–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1985.tb02058.x

79. Collins P, Ferguson J. Narrow-band UVB (TL-01) phototherapy - an effective preventative treatment for the photodermatoses. Br J Dermatol. (1995) 132:956–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1995.tb16955.x

80. Parrish JA, Jaenicke KF, Morison WL, Momtaz K, Shea C. Solar Urticaria - treatment with PUVA and mediator inhibitors. Br J Dermatol. (1982) 106:575–80. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1982.tb04561.x

81. Hudson-Peacock MJ, Farr PM, Diffey BL, Goodship THJ. Combined treatment of solar urticaria with plasmapheresis and PUVA. Br J Dermatol. (1993) 128:440–2. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1993.tb00206.x

82. Calzavara-Pinton P, Zane C, Rossi M, Sala R, Venturini M. Narrowband ultraviolet B phototherapy is a suitable treatment option for solar urticaria. J Am Acad Dermatol. (2012) 67: e5–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2011.01.030

84. Dawe RS, Ferguson J. Prolonged benefit following ultraviolet A phototherapy for solar urticaria. Br J Dermatol. (1997) 137:144–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1997.tb03719.x

85. Roelandts R. Photo(chemo)therapy and general management of erythropoietic protoporphyria. Dermatology (1995) 190:330–1. doi: 10.1159/000246734

87. Warren LJ, George S. Erythropoietic protoporphyria treated with narrow-band (TL-01) UVB phototherapy. Australas J Dermatol. (1998) 39:179–82. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-0960.1998.tb01278.x

88. Sivaramakrishnan M, Woods J, Dawe R. Narrowband ultraviolet B phototherapy in erythropoietic protoporphyria: case series. Br J Dermatol. (2014) 170:987–8. doi: 10.1111/bjd.12714

89. Sevrain M, Richard MA, Barnetche T, Rouzaud M, Villani AP, Paul C, et al. Treatment for palmoplantar pustular psoriasis: systematic literature review, evidence-based recommendations and expert opinion. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. (2014) 28:(Suppl. 5), 13–16. doi: 10.1111/jdv.12561

90. Rosen K, Mobacken H, Swanbeck G. Chronic eczematous dermatitis of the hands: a comparison of PUVA and UVB treatment. Acta Derm Venereol. (1987a) 67:48–54

91. Rosen K, Jontell M, Mobacken H, Rosdahl I. Epidermal Langerhans' cells in chronic eczematous dermatitis of the palms treated with PUVA and UVB. Acta Derm Venereol. (1989) 69:200–5.

92. Mobacken H, Rosen K, Swanbeck G. Oral psoralen photochemotherapy (PUVA) of hyperkeratotic dermatitis of the palms. Br J Dermatol. (1983) 109:205–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1983.tb07082.x

93. Tegner E, Thelin I. PUVA treatment of chronic eczematous dermatitis of the palms and soles. Acta Derm Venereol. (1985) 65:451–3.

94. Sezer E, Erbil AH, Kurumlu Z, Taştan HB, Etikan I. Comparison of the efficacy of local narrowband ultraviolet B (NB-UVB) phototherapy versus psoralen plus ultraviolet A (PUVA) paint for palmoplantar psoriasis. J Dermatol. (2007) 34:435–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1346-8138.2007.00306.x

95. Murray D, Corbett MF, Warin AP. A controlled trial of photochemotherapy for persistent palmoplantar pustulosis. Br J Dermatol. (1980) 102:659–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1980.tb06565.x

96. Rosen K, Mobacken H, Swanbeck G. PUVA, etretinate and PUVA-etretinate therapy for pustulosis palmoplantaris - A plceob-controlled comparative trial. Arch Dermatol. (1987b) 123:885–9. doi: 10.1001/archderm.1987.01660310053013

97. Chalmers RJG, Hollis S, Leonardi-Bee J, Griffiths CEM, Marsland A. Interventions for chronic palmoplantar pustulosis. Coch Database Syst Rev. (2006) CD001433. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001433.pub2

98. Aydogan K, Karadogan SK, Tunali S, Saricaoglu H. Narrowband ultraviolet B (311 nm, TL01) phototherapy in chronic ordinary urticaria. Int J Dermatol. (2012) 51:98–103. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2011.05056.x

99. Khafagy NH, Salem SAM, Ghaly EG. Comparative study of systemic psoralen and ultraviolet A and narrowband ultraviolet B in treatment of chronic urticaria. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. (2013) 29:12–7. doi: 10.1111/phpp.12008

100. Engin B, Ozdemir M, Balevi A, Mevlitoglu I. Treatment of chronic urticaria with narrowband ultraviolet B phototherapy: a randomized controlled trial. Acta Derm Venereol. (2008) 88:247–51. doi: 10.2340/00015555-0434

101. Bishnoi A, Parsad D, Vinay K, Kumaran MS. Phototherapy using narrowband ultraviolet B and psoralen plus ultraviolet A is beneficial in steroid-dependent antihistamine-refractory chronic urticaria: a randomized, prospective observer-blinded comparative study. Br J Dermatol. (2017) 176:62–70. doi: 10.1111/bjd.14778

102. Farnaghi F, Seirafi H, Ehsani AH, Agdari ME, Noormohammadpour P. Comparison of the therapeutic effects of narrow band UVB vs. PUVA in patients with pityriasis lichenoides. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. (2011) 25:913–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2010.03879.x

103. Pavlovsky M, Samuelov L, Sprecher E, Matz H. NB-UVB phototherapy for generalized granuloma annulare. Dermatol Ther. (2016) 29:152–4. doi: 10.1111/dth.12315

104. Cunningham L, Kirby B, Lally A, Collins P. The efficacy of PUVA and narrowband UVB phototherapy in the management of generalized granuloma annulare. J Dermatol Treat, (2016) 27:136–9. doi: 10.3109/09546634.2015.1087461

105. Brazzelli V, Grassi S, Merante S, Grasso V, Ciccocioppo R, Bossi G, et al. Narrow-band UVB phototherapy and psoralen-ultraviolet A photochemotherapy in the treatment of cutaneous mastocytosis: a study in 20 patients. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. (2016) 32:238–46. doi: 10.1111/phpp.12248

106. Godt O, Proksch E, Streit V, Christophers E. Short- and long-term effectiveness of oral and bath PUVA therapy in urticaria pigmentosa and systemic mastocytosis. Dermatology (1997) 195:35–9. doi: 10.1159/000245681

107. Kolde G, Frosch PJ, Czarnetzki BM. Response of cutaneous mast cells to PUVA in patients with urticaria pigmentosa: histomorphometric, ultrastructural, and biochemical investigations. J Invest Dermatol. (1984) 83:175–8. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep,12263520

108. Morgado-Carrasco D, Riera-Monroig J, Fusta-Novell X, Podlipnik S, Aguilera P. Resolution of aquagenic pruritus with intermittent UVA/NBUVB combined therapy. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. (2017) 33:291–2. doi: 10.1111/phpp.12320

109. Holme SA, Anstey AV. Aquagenic pruritus responding to intermittent photochemotherapy. Clin Exp Dermatol. (2001) 26:40–1. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2230.2001.00757.x

110. Menage HD, Norris PG, Hawk JL, Graves MW. The efficacy of psoralen photochemotherapy in the treatment of aquagenic pruritus. Br J Dermatol. (1993) 129:163–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1993.tb03520.x

111. Iraji F, Faghihi G, Asilian A, Siadat AH, Larijani FT, Akbari M. Comparison of the narrow band UVB versus systemic corticosteroids in the treatment of lichen planus: A randomized clinical trial. J Res Med Sci. (2011) 16:1578–82.

112. Solak B, Sevimli Dikicier B, Erdem T. Narrow band ultraviolet B for the treatment of generalized lichen planus. Cutan Ocul Toxicol. (2016) 35:190–3. doi: 10.3109/15569527.2015.1074587

113. Wackernagel A, Legat FJ, Hofer A, Quehenberger F, Kerl H, Wolf P. Psoralen plus UVA vs. UVB-311 for the treatment of lichen planus. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. (2007) 23:15–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0781.2007.00261.x

114. Atzmony L, Reiter O, Hodak E, Gdalevich M, Mimouni D. Treatments for cutaneous lichen planus: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Clin Dermatol. (2016) 17:11–22. doi: 10.1007/s40257-015-0160-6

115. Mohamed Z, Bhouri A, Jallouli A, Fazaa B, Kamoun MR, Mokhtar I. Alopecia areata treatment with a phototoxic dose of UVA and topical 8-methoxypsoralen. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. (2005) 19:552–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2005.01226.x

116. Taylor CR, Hawk JL. PUVA treatment of alopecia areata partialis, totalis and universalis: audit of 10 years' experience at St John's Institute of Dermatology. Br J Dermatol. (1995) 133:914–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1995.tb06925.x

117. Healy E, Rogers S. PUVA treatment for alopecia areata–does it work? A retrospective review of 102 cases. Br J Dermatol. (1993) 129:42–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1993.tb03309.x

118. Messenger AG, Mckillop J, Farrant P, Mcdonagh AJ, Sladden M. British Association of Dermatologists' guidelines for the management of alopecia areata 2012. Br J Dermatol. (2012) 166:916–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2012.10955.x

119. Decock S, Roelandts R, Steenbergen WV, Laleman W, Cassiman D, Verslype C, et al. Cholestasis-induced pruritus treated with ultraviolet B phototherapy: an observational case series study. J Hepatol. (2012) 57:637–41. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2012.04.023

Keywords: UVB, PUVA therapy, phototherapy, skin diseases, psoriasis, eczema, vitiligo

Citation: Ibbotson SH (2018) A Perspective on the Use of NB-UVB Phototherapy vs. PUVA Photochemotherapy. Front. Med. 5:184. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2018.00184

Received: 21 February 2018; Accepted: 01 June 2018;

Published: 02 July 2018.

Edited by:

Peter Wolf, Medizinische Universität Graz, AustriaReviewed by:

Thilo Gambichler, University Hospitals of the Ruhr-University of Bochum, GermanyPiergiacomo Calzavara-Pinton, University of Brescia, Italy

Franz J. Legat, Medizinische Universität Graz, Austria

Copyright © 2018 Ibbotson. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Sally H. Ibbotson, cy5oLmliYm90c29uQGR1bmRlZS5hYy51aw==

Sally H. Ibbotson

Sally H. Ibbotson