- China-Japan Union Hospital of Jilin University, Changchun, China

Developing cost-efficient and high-performance non-noble metal electrocatalysts for oxygen reduction reaction is of great significance for large-scale commercialization of fuel cells. Here, a novel cobalt phosphate-embedded nitrogen and phosphorus co-doped graphene aerogel [labeled as Co3(PO4)2/N,P-GA] is prepared via combination of a facile hydrothermal apporoach with a pyrolysis procedure. The obtained Co3(PO4)2/N,P-GA catalysts display excellent catalytic performance in base media, with optimal Co3(PO4)2/N,P-GA-900 (the material prepared at pyrolysis temperature of 900°C) showing better catalytic activity for ORR than other as-obtained contrast materials in terms of the onset potential, half-wave potential and diffusion-limiting current density, even superior to the commercial Pt/C catalyst. Furthermore, the Co3(PO4)2/N,P-GA also possesses good methanol tolerance and excellent durability. The superior performance of Co3(PO4)2/N,P-GA is attributed to the hierachical porous structure, large BET surface area, N,P-codoping, cobalt phosphate-based nanoparticles loaded on graphene nanosheets, and synergistic effects between the doped active species. Therefore, it is expected to replace Pt/C as a promising fuel cell catalyst in alkaline direct methanol fuel cells.

Introduction

Fuel cells and metal-air batteries have been identified as clean and efficient energy conversion and storage techniques due to their environmentally-friendly and sustainable features (Ren et al., 2000), in which the electrochemical oxygen reduction reaction (ORR) plays a critical role (Walter et al., 2010; Shao et al., 2012; Katsounaros et al., 2014; Zheng et al., 2014; Dai et al., 2015; Zhang et al., 2015a,b). As an important half-reaction in these energy conversion and storage technologies, ORR is subjected to sluggish kinetics, so using the catalyst to improve the reaction rate is of great significance (Debe, 2012; Chen et al., 2014). At present, the most efficient electrocatalysts for ORR are noble platinum-based catalysts. However, the scarcity and high price of platinum have impeded their large-scale application in energy conversion and storage techniques. Therefore, it is urgent but remains challenging to develop non-noble catalysts with low cost and high activity for ORR (Hou et al., 2014b; Menezes et al., 2015; Yuan et al., 2015).

In recent years, transition metal phosphates have been aroused wide concern for energy conversion and storage applications due to their catalytic efficiency and high stability (Kim et al., 2007; Kanan and Nocera, 2008; Park et al., 2010; Wang et al., 2011a; Gonzalez-Flores et al., 2015). Among them, Mn(II) and Co(II) phosphates have especially attracted tremendous attention because of their potential as a ORR catalyst (Zhan et al., 2016). However, they have accomplished little success in the recent state of investigation and development because of their high tendency for aggregation and low conductivity. Hence, it is necessary to decorate the metal phosphates nanoparticles with conducting carbon materials in order to improve their catalytic activity (Liang et al., 2013; Mao et al., 2014; Xia et al., 2015; Hu et al., 2016; Zhou et al., 2016). Among these carbonaceous materials, graphene is considered as an ideal carbon substrate due to the special sp2-hybrid structure, high electrical conductivity, excellent chemical stability, and large specific surface area (Geim and Novoselov, 2007; Wang et al., 2011b; Yang et al., 2011; Yu et al., 2011). The abundance of functional groups on the graphene surface that can serve as the nucleation sites increases the nanoparticle dispersion and decreases the nanoparticle size, resulting in enhanced activity and a greater utilization of the active material (Wang and Dai, 2013; Hou et al., 2014a; Li et al., 2018).

Many studies have been conducted to improve the ORR activity of graphene-based materials by surface modification with heteroatoms (Wang et al., 2012, 2014; Hou et al., 2014b). Particularly, N-doped graphene materials has been widely studied due to their excellent ORR catalytic activity (Wang et al., 2011c; Hibino et al., 2013; Goran et al., 2015). The reason for improving the catalytic activity is that the N atoms incorporated into carbon matrix can create a lot of active sites and change asymmetry spin density and charge density of the carbon lattice (Gong et al., 2009; Jeon et al., 2013; Cheon et al., 2014). Phosphorus (P), another group-V element, possesses the same valance electron number and similar chemical behavior with N (Hu et al., 2014). P has higher electron-donating ability and stronger n-type effect than N, which make it a good candidate as a dopant in graphene (Some et al., 2012). In addition, P has an electronegativity value of 2.19 that is lower than that of N (3.04). The introduction of N and P with different electronegativity into carbon skeleton can effectively increase defect density, creating more reactive sites for ORR (Wang et al., 2012, 2014). More importantly, the synergistic effect between N and P can further enhance the electrocatalytic activity toward ORR (Maria Rosas et al., 2012; Nasini et al., 2014; Ornelas et al., 2014; Razmjooei et al., 2014).

In addition to modifying the graphene surface, the structure of graphene has much effect on the catalytic activity, two-dimensional (2D) graphene sheets easily lead to aggregation and accumulation during drying due to physical interaction, leading to a decrease in specific surface area (Mao et al., 2015; Fu et al., 2016). Assembling 2D graphene into a 3D architectures is an feasible method to overcome the accumulation problem. The 3D graphene aerogel possesses interconnected pore structures, thus providing more exposed reactive sites as well as high rate of mass transfer and electron transport for the heteroatoms-doped graphene-based composites.

Based on discussion above, it is believed that loading transition metal phosphate nanoparticles on heteroatoms-doped graphene aerogels is an effective method to construct highly-efficient ORR catalysts. Benefiting from high conductivity, large specific surface area and heteroatoms doping effect of graphene aerogel, as well as the cooperativity of transition metal phosphates and heteroatoms-doped graphene aerogels, the obtained hybrids are expected to deliver excellent electrocatalytic activity and good stability for ORR. To the best of our knowledge, there are few reports in this aspect (Yuan et al., 2015).

Herein, we report a novel catalyst composed of Co3(PO4)2 nanoparticles and the 3D N,P-codoped graphene aerogel (Co3(PO4)2/N,P-GA). The hybrid is prepared via a two-step method, consisting of a hydrothermal assembly process and subsequent pyrolysis procedure in the Ar atmosphere. The as-obtained Co3(PO4)2/N,P-GA-900 (where 900 represents the pyrolysis temperature of 900°C) catalyst displays excellent catalytic activity and good operational stability for ORR, and is expected to substitute the commercial Pt/C as a promising electrocatalyst for ORR.

Experimental Section

Materials

Graphite powder was purchased from Beijing Chemical Company (China). Nafion® perfluorinated resin solution (5%) was bought from Sigma-Aldrich. Phytic acid (PA) was purchased from Aladdin Ltd (Shanghai, China). Commercial Pt/C (20 wt% Pt on Vulcan carbon black) catalyst was provided by Alfa Aesar. Ultra-pure water was obtained from a Milli-Q water system. All other reagents were of analytical reagent grade and used directly.

Synthesis of Co3(PO4)2/N,P-GA-900

Graphene oxide (GO) was prepared through the modified Hummers' method according to a previous report (Zhang et al., 2014). Typically, GO was dispersed into water to form a suspension (2 mg mL−1) by ultrasonic vibration. Then, cobalt acetate (10 mg), urea (500 mg), and glucose (20 mg) were dissolved in 10 mL water, followed by adding aqueous ammonia into the above solution to adjust solution pH greater than 12. Finally, PA (20 mg) and GO (10 ml, 2 mg mL−1) were added into the above solution. The obtained suspension was sonicated for 1 h, transferred to a 50 mL Teflon-lined stainless autoclave and hydrothermally treated at 180°C for 12 h. After cooling to the ambient temperature, the hydrogel was obtained. The hydrogel was washed with deionized water until neutral pH, followed by freeze-drying to get the aerogel. The as-synthesized aerogel was directly pyrolyzed at the set temperature in a tube furnace in Ar atmosphere for 1 h and the heating rate is 5°C min−1. The corresponding samples pyrolyzed at 700, 800, 900, and 1,000°C were denoted as Co3(PO4)2/N,P-GA-700, Co3(PO4)2/N,P-GA-800, Co3(PO4)2/N,P-GA- 900, Co3(PO4)2/N,P-GA-1000, respectively. For comparison, the Co/N-doped graphene aerogel (Co/N-GA-900), Co2P/P-doped graphene aerogel (Co2P/P-GA-900), and N,P-doped graphene aerogel (N,P-GA-900) were also prepared by using the same procedures as making Co3(PO4)2/N,P-GA-900, but without the presence of PA, urea and Co(acac)2 during the hydrothermal process, respectively.

Characterization

The morphology and microstructure of the catalysts were characterized by using scanning electron microscopy (SEM, JEOL JSM-6701F operating at an accelerating voltage of 5 kV) and transition electron microscopy (TEM, JEOL-2010 operating at 200 kV) techniques. TEM associated energy-dispersive X-ray (EDX) elemental mapping was obtained from a JEOL-2010 transmission electron microscope operating at 200 kV. The crystal structural information was recorded on a power X-ray diffractometer by using Cu-Kα radiation (RIGAKU, D/MAX2250VB/PC). The specific surface area and pore structure were characterized on a Micromeritics ASAP 2020 surface area and porosity analyzer conducted at 77 K with N2 as adsorbate. The specific surface areas of the catalysts were evaluated from the nitrogen adsorption/desorption isotherms by utilizing the Brunauer-Emmett-Teller (BET), whereas the pore size distribution curves were obtained from the Barrett-Joyner-Halenda (BJH) method (for mesopores) and the density functional theory (DFT) method (for micropores). The surface chemical composition was measured by X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS), using an ESCLAB 250 spectrometer with a monochromatized Al Kα X-ray source. Raman spectra were collected on a Lab RAMHR Evolution Raman spectrometer using 532 nm excitation laser.

Electrochemical Test

To research the electrochemical catalytic activity of the as-prepared catalysts, a series of electrochemical tests were conducted on a CHI760E electrochemical workstation assembled with a rotational system with a standard three-electrode glass cell, in which a platinum sheet was served as the counter electrode, saturated calomel electrode (SCE) as the reference electrode and a modified glass carbon electrode as the working electrode. In order to modify the working electrode, 1 mg of the as-prepared catalyst power was dispersed in 1 mL of ethanol and treated by ultrasonic vibration for 2 h, and then 55 uL of the catalyst solution was dropped onto the GCE by a microsyringe. Finally, 1.0 uL of 10% Nafion solution (in ethanol) was placed on the working electrode serving as a protector. After drying at room temperature, the electrocatalyst was loaded on the working electrode with the catalyst loading of around 280 μg cm−2. As a contrast, the commercial Pt/C (20 wt% Pt on Vulcan carbon black) catalyst was used as a reference. All electrochemical tests were proceeded after receiving stable cyclic voltammetry (CV) curves by continuous CV tests. All of the potentials reported in this work were referenced to the reversible hydrogen electrode (RHE) scale according to the Nernst equation (ERHE = ESCE+0.059pH+0.242 V).

Results and Discussion

Characterization of Morphology and Structure

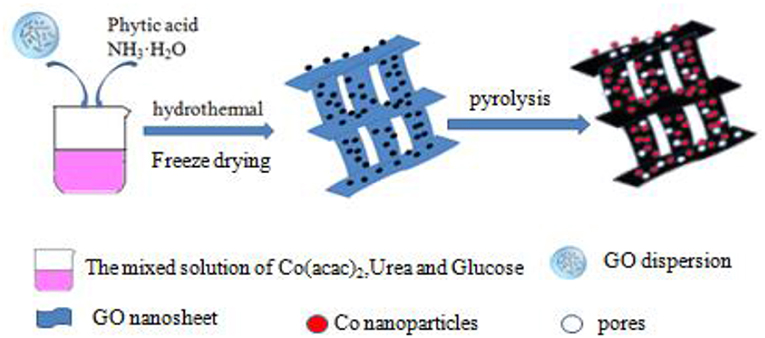

The process for synthesis of the Co3(PO4)2/N,P-GA-900 is illustrated in Scheme 1. In the first step, phytic acid and GO suspension were successively added to a mixture solution of cobalt acetate, urea and glucose containing aqueous ammonia. Then the mixture was hydrothermally treated to form cobalt-based nanoparticles and make the GO sheets assemble into 3D graphene hydrogel. The gas evolution generated micropores, and graphene was further reduced during the process of pyrolysis.

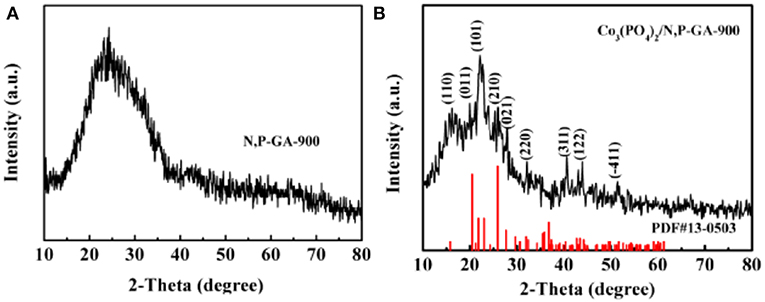

To identify the crystallographic phases of the as-obtained N,P-GA-900 and Co3(PO4)2/N,P-GA-900 catalysts, the X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis was performed. In Figure 1, two composites appear a broad diffraction peak at 2θ≈26.0°, implying the formation of graphitic structure in the hybrids (Liu et al., 2016) For Co3(PO4)2/N,P-GA-900, the characteristic diffraction peaks at 2θ≈21.9, 25.9, 27.8, 32.1, 40.6, 44.1, and 51.7° are recognized, corresponding to the (101), (210), (021), (220), (311), (122), and (−411) crystalline facets of Co3(PO4)2 (JCPDS No.13-0305, Figure 1B), respectively. The XRD results prove the formation of Co3(PO4)2 nanocrystals. As exhibited in Figure S1a, the specific diffractive peaks of Co2P/P-GA-900 are easily indexed to Co2P phase with reference to the standard card (PDF card no.32-0306), which suggests the existence of Co2P. Besides, the XRD pattern of Co/N-GA-900 composite exhibits the full suite of the characteristic peaks of Co (JCPDS file # 15-0806, Figure S1b).

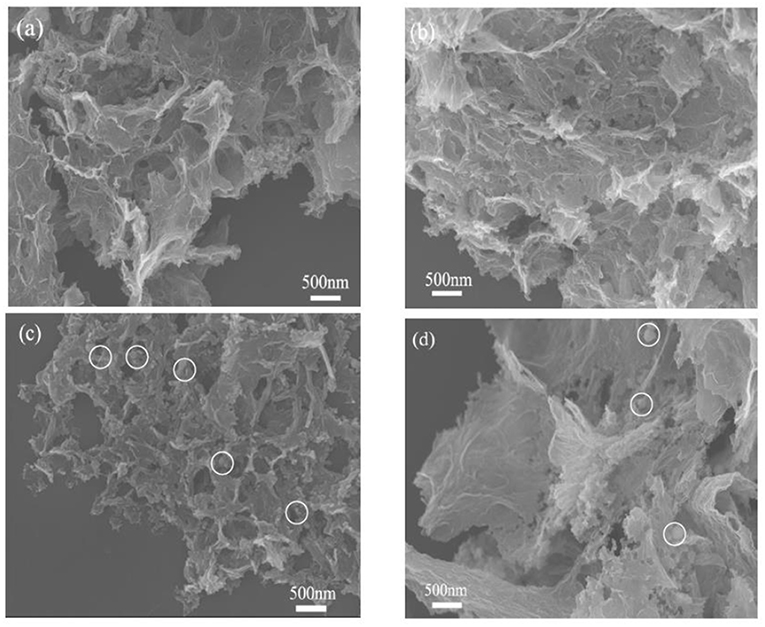

To reveal the morphological and structural information of the obtained catalysts, scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and transmission electron microscopy (TEM) were performed. The N,P-GA-900 exhibits a three-dimensional (3D) crumpled morphology with microsized pores constructed by interconnected GO sheets, which can provide abundant channels for the transportation of ORR-relevant species (Figure 2a). For the as-synthesized Co3(PO4)2/N,P-GA-900 composite, the nanoparticles loaded on N,P-GA can be clearly seen without obvious aggregation (see Figure 2b). The in-situ growth of nanoparticles within pore structure of graphene can enhance the interaction between nanoparticles and graphene. Above SEM results definitely validate that the Co3(PO4)2/N,P-GA-900 with an interconnected porous network was successfully prepared. Additionally, one can also observe the existence of Co2P and Co nanoparticles loaded on folded 3D P-doped and N-doped graphene aerogels, respectively (see Figures 2c,d).

Figure 2. SEM images of (a) the N,P-GA-900; (b) the Co3(PO4)2/N,P-GA-900; (c) the Co2P/P- GA-900; and (d) Co/N-GA-900.

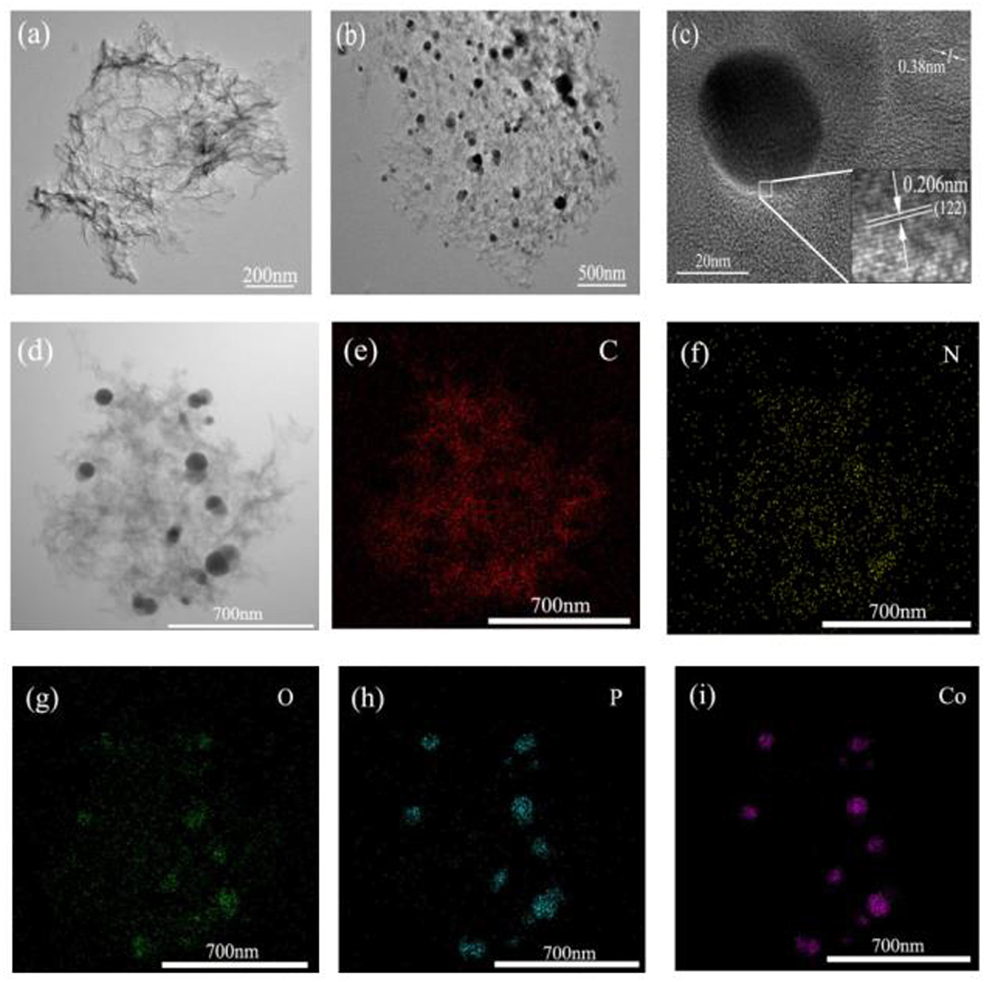

TEM images (see Figure 3a) disclose that the N,P-GA-900 presents crumpled and wrinkle-like structure, in line with those of SEM results. The TEM image and corresponding elemental mappings indicate the presence of C, N, and P in the N,P-GA-900 (Figure S2), manifesting that N and P were successfully doped into graphene skeleton. In Figure 3b, one can clearly see the nanoparticles distributed on wrinkle-like graphene sheets, and the d-spacing of crystalline lattices is 0.206 nm, which corresponds to the (122) plane of Co3(PO4)2 (Figure 3c). The measured interplanar distances of graphene are ~0.38 nm, in accord with the separation of the layers of hexagonal graphite. The EDS elemental mapping shows the presence of C, N, O, P and Co elements (Figures 3d–i). Moreover, Co, P as well as O elements are mainly distributed in the area where nanoparticles exist (Figures 3g–i). These results suggest that the Co3(PO4)2 nanoparticles may have been formed. In addition, the different resolution TEM images of Co2P/P-GA-900 and Co/N-GA-900 are demonstrated in Figure S4. The nanoparticles scattered on graphene sheets can also be observed (Figures S3a,b). Obviously, the lattice fringes with a d-spacing of 0.220 nm are designated to the (121) plane of Co2P (Figure S3c), confirming the formation of Co2P nanoparticles. Moreover, Co (111) and (200) planes can be clearly observed with the lattice plane spacings of 0.205 and 0.175 nm, respectively (Figure S3d).

Figure 3. (a) TEM images of N,P-GA-900; (b–d) tem IMAGES OF cO3(po4)2/n,p-ga-900 AT DIFFERENT MAGNIFICATIONs; (e–i) Elemental mappings of C, N, O, P and Co of Co3(PO4)2/N,P-GA-900.

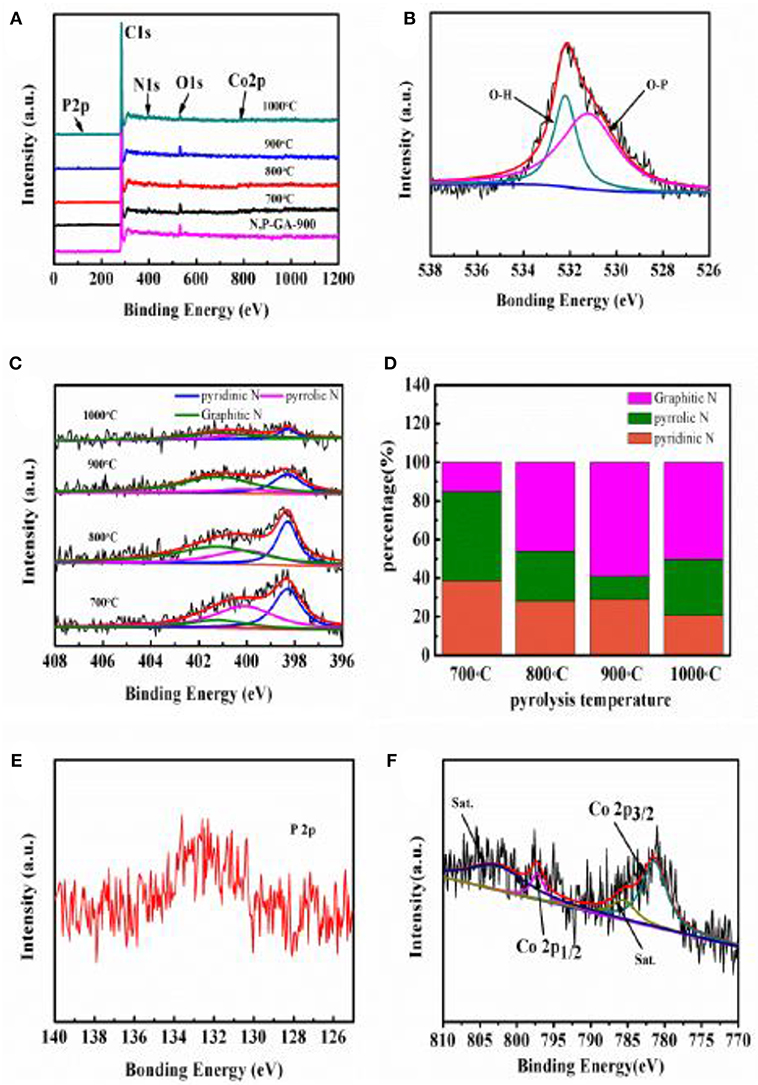

X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy was further used to evaluate the elemental compositions and bonding states on the catalyst surface. As presented in Figure 4A, C, N, O, P, and Co elements are detected from the overall XPS spectra of Co3(PO4)2/N,P-GA-900, in agreement with the EDS mapping results. Obviously, the high-resolution O 1s signals are centered at ca. 530.2, 531.9, and 532.8 eV, which are assigned to the Co-O in Co3(PO4)2, C-O and C = O in graphene, as displayed in Figure 4B (Fei et al., 2015). The high-resolution N 1s spectrum of Co3(PO4)2/N,P-GA-900 can be deconvoluted into three signals, different N species at around 398.3, 400.1, and 401.2 eV are assigned to pyridinic N, pyrrolic N and graphitic N, respectively (Shanmugam and Osaka, 2011; Yang et al., 2011). Moreover, the catalysts pyrolyzed at other temperatures have the same nitrogen forms with Co3(PO4)2/N,P-GA-900 (Figure 4C). The total nitrogen contents of Co3(PO4)2/N,P-GA-700, Co3(PO4)2/N,P-GA-800, Co3(PO4)2/N,P-GA-900 and Co3(PO4)2/N,P-GA-1000 are estimated to be 3.84, 3.7, 2.46, and 2.11 at %, respectively. Obviously, the nitrogen contents decrease rapidly at elevated pyrolysis temperatures, which can be attributed to the instability of nitrogen in high temperature (Zhong et al., 2014). However, the percentage content of graphitic N increases gradually due to the conversion of pyridinic N and pyrrolic N to graphitic N at higher annealing temperatures (Figure 4D). It is proposed that pyridinic N and graphitic N are the main forms to improve the activity for ORR (Lai et al., 2012), and the former enhances the onset potential whereas the latter increases the limiting current density. Taking the highest total percentage content of pyridinic-N and graphitic-N in the Co3(PO4)2/N,P-GA-900 into consideration, it is expected that the as-prepared composite possesses outstanding catalytic performance for oxygen reduction reaction. The information of P 2p spectrum is rendered in Figure 4E. The single peak located at 133 eV can be attributed to the phosphate in the composite (Steinmiller and Choi, 2009). The P is introduced by phytic acid, additional P incorporating into N-doped graphene have proven to create more active sites and generate synergistic effects for ORR electrocatalysis (Yang et al., 2012; Jiang et al., 2014).

Figure 4. (A) The XPS survey spectra of N,P-GA-900 and Co3(PO4)2/N,P-GA at different pyrolysis temperatures; (B,C,E,F) High-resolution XPS spectra of O 1s, N 1s, P 2p, and Co 2p of Co3(PO4)2/N,P-GA-900; (D) The percentage of deconvoluted N 1s species in Co3(PO4)2/N,P-GA.

Co also can be detected from the Co3(PO4)2/N,P-GA-900 specimen surface. High-resolution Co 2p spectrum (Figure 4F) discloses the binding energies of Co 2p3/2 and Co 2p1/2 at 781.4 and 797.2 eV with their corresponding satellite peaks at 787.6 and 802.7 eV, respectively. These binding energies are characteristic of Co(II) in the hybrid material (Zhou et al., 2016). The above observations further demonstrate that the Co3(PO4)2 loaded nitrogen and phosphorus-codoped graphene aerogel [Co3(PO4)2/N,P-GA] hybrid materials were successfully obtained.

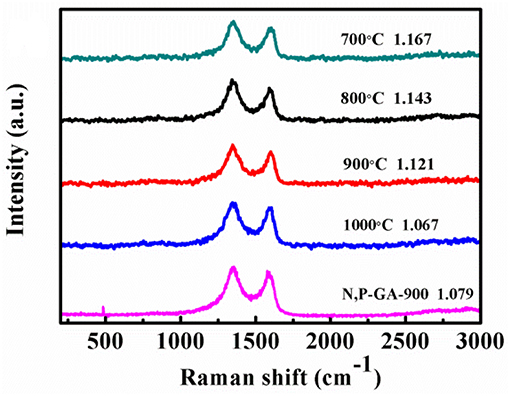

Raman spectroscopy has been widely used to evaluate the degree of graphitization and defect. According to Figure 5, the catalysts obtained at different temperatures show two distinct peaks in 1,349 cm−1 (D-band) and 1,590 cm−1 (G-band), which correspond to the disordered carbon and sp2 hybridized graphitic carbon, respectively (Zhang et al., 2013). The ID/IG proportions of Co3(PO4)2/N,P-GA-700, Co3(PO4)2/N,P-GA-800, Co3(PO4)2/N,P-GA-900, Co3(PO4)2/N,P-GA-1000 and N,P-GA-900 are 1.167, 1.143, 1.121, 1.067, and 1.079, respectively. The ratios of ID to IG for the Co3(PO4)2/N,P-GA decreases with the increase of pyrolysis temperature, which implies that a higher pyrolysis temperature facilitates the generation of more ordered graphitic carbon. High degree of graphitization can improve the electronic conductivity and erosion resistance of the as-obtained composite (Chen et al., 2015). It is worth noting that the ID/IG value (1.121) of Co3(PO4)2/N,P-GA-900 is larger than that (1.079) of N,P-GA-900, suggesting the introduction of Co3(PO4)2 leads to formation of more structure distortion. This result definitely demonstrates that more defects exist in the Co3(PO4)2/N,P-GA-900 hybrid.

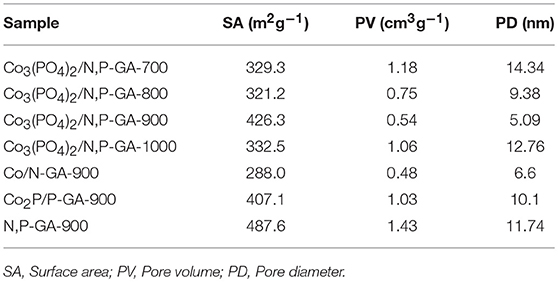

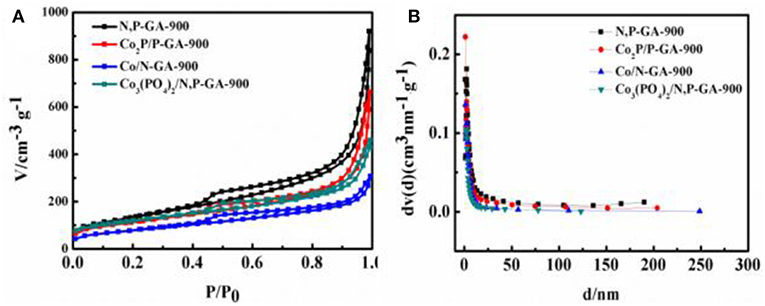

Brunauer-Emmett-Teller (BET) analysis was used to characterize the specific surface areas, pore sizes and pore volumes for the as-prepared catalysts (Figures 6A,B). In Figure 6A, the nitrogen adsorption-desorption curve displays a typical type-IV isotherm with a distinct hysteresis loop at the relative pressures (P/P0) between 0.45 and 1.00, indicating the existence of mesopores in as-prepared Co3(PO4)2/N,P-GA-900 catalyst. The pore structure parameters of all as-prepared composites are presented in Table 1. It can be seen that the BET surface area of Co3(PO4)2/N,P-GA-900 (426.3 m2 g−1) is distinctly larger than those of Co/N-GA-900 (288.0 m2 g−1) and Co2P/P-GA-900 (407.1 m2 g−1), demonstrating that the N/P co-doping is beneficial for an increase in BET surface area. Besides, Co3(PO4)2/N,P-GA-900 possesses the highest specific BET surface area relative to other Co3(PO4)2/N,P-GA-T (T = 700, 800, 1,000) counterparts, which is beneficial for the exposure of more active sites. It is worth noting that the BET surface area of Co3(PO4)2/N,P-GA-900 is slightly reduced when compared to N,P-GA-900 (487.6 m2 g−1), which can be attributable to the incorporation of Co3(PO4)2 nanoparticles into N,P-GA.

Figure 6. (A) Nitrogen adsorption-desorption isotherms and (B) pore size distribution of N,P-GA-900, Co/N-GA-900, Co2P/P-GA-900, and Co3(PO4)2/N,P-GA-900.

Electrocatalytic Performance for ORR

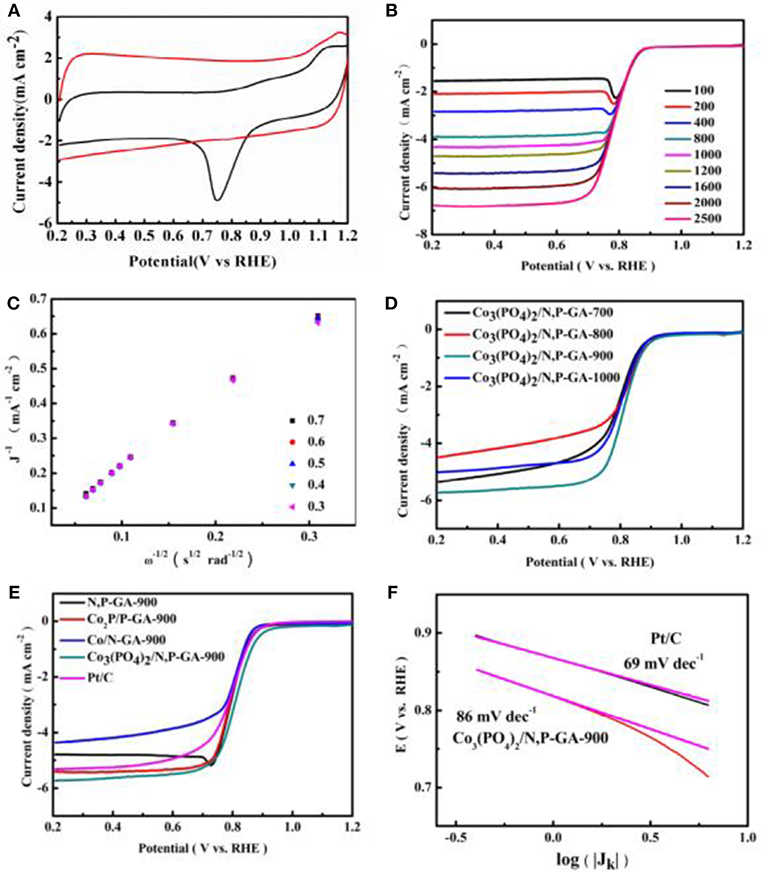

To evaluate the ORR performance of Co3(PO4)2/N,P-GA-900, cyclic voltammetry (CV) curves were firstly recorded to estimate the electrocatalytic activity in O2-/N2-saturated 0.1 M KOH solutions. As seen in Figure 7A, the Co3(PO4)2/N,P-GA-900 shows a palpable cathode reduction peak in an O2-saturated solution whereas no characteristic peak in a N2-saturated electrolyte, suggesting the electroactivity of Co3(PO4)2/N,P-GA-900 for ORR. Linear sweep voltammetry (LSV) curves of Co3(PO4)2/N,P-GA-900 in Figure 7B exhibits the limiting current density augment with the increase of rotating speeds from 100 to 2,500 rpm, due to the reduced diffusion distance at higher speeds. The corresponding Koutecky-Levich (K-L) plots show linearity and parallelism, indicating the first-order kinetics relative to the concentration of dissolved oxygen and similar electron transfer numbers (Figure 7C). Pyrolysis temperature is a significant factor in affecting active sites, and different pyrolysis temperatures result in different catalytic activities. By changing the pyrolysis temperature (700, 800, 900, and 1,000°C), one can see that the catalyst Co3(PO4)2/N,P-GA-900 possesses the best ORR activity in relation to onset potential (E0), half-wave potential (E1/2), and limiting current density (JL), as shown in Figure 7D. Consequently, 900°C is the optimal temperature, and other contrast samples are treated at the same temperature. As displayed in Figure 7E, the Co3(PO4)2/N,P-GA-900 shows more prominent ORR catalytic activity than that of Co/N-GA-900 and Co2P/P-GA-900, confirming that the synergistic effect of nitrogen and phosphorus can improve the performance of catalyst. Moreover, Co3(PO4)2/N,P-GA-900 exhibits more positive onset potential (0.95 V vs. RHE) than N,P-GA-900 (0.91 V vs. RHE), manifesting that the Co3(PO4)2 nanoparticles loaded are also the main active sites in enhancing the ORR activity. Not only that, the E0 and E1/2 of Co3(PO4)2/N,P-GA-900 (0.95 V, 0.81 V) approaches to that of the commercial Pt/C (0.95 V, 0.80 V), while its diffusion limiting current density (5.73 mA cm−2) is superior to the benchmark Pt/C (5.33 mA cm−2). These results distinctly suggest that the Co3(PO4)2/N,P-GA-900 possesses rapid kinetics process for ORR (Figure S5 and Table S1). The ORR kinetics was also evaluated by Tafel slope (see Figure 7F). The Co3(PO4)2/N,P-GA-900 catalyst gives a Tafel slope of 86 mV dec−1, close to 20 wt% Pt/C (69 mV dec−1), verifying the similar ORR mechanism of these two catalysts. The outstanding ORR activity of Co3(PO4)2/N,P-GA-900 in alkaline media may be attributed to the synergistic effects of the following factors: (1) The particular 3D wrinkle porous architecture is beneficial for exposing more active sites and accelerating the accessibility of oxygen; (2) The insertion of N and P heteroatoms into the carbon skeleton is conductive to an increase in BET surface area. Additionally, it can trigger charge redistribution and promote the adsorption of oxygen and the reduction reaction on graphene; (3) The Co3(PO4)2 inserted into N,P-GA can not only produce more defects, but also improve the ORR activity of the obtained hybrid catalyst; (4) The synergistic coupling between the doped active components conduces to enhance the ORR activity markedly.

Figure 7. (A) CV curves of the Co3(PO4)2/N,P-GA- 900 in N2- and O2-saturated 0.1 M KOH at a scan rate of 100 mV s−1; (B) LSV curves on Co3(PO4)2/N,P-GA-900 in an O2-saturated 0.1 M KOH with a scan rate of 10 mV s−1; (C) The corresponding K-L plots of ORR for Co3(PO4)2/N,P- GA-900 catalyst; (D) LSV polarization curves of Co3(PO4)2/N,P-GA-T (T = 700, 800, 900, and 1,000) in O2-saturated 0.1 M KOH at a scan rate of 10 mV s−1 with the rotating speed of 1,600 rpm; (E) LSV polarization curves ofCo3(PO4)2/N,P-GA-900, Co2P/P-GA-900, Co/N-GA-900 and Pt/C in O2-saturated 0.1 M KOH at a scan rate of 10 mV s−1 with the rotating speed of 1,600 rpm; (F) Tafel plots of Co3(PO4)2/N,P-GA-900 and Pt/C in 0.1 M KOH.

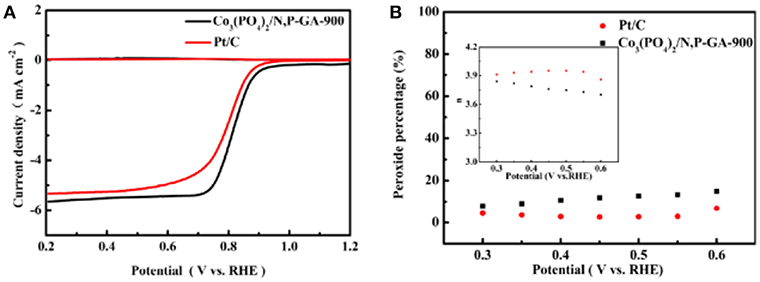

The ORR in an alkaline medium can be achieved via two possible pathways: involving a two-electron process to generate H2O2/, or the other, a direct four-electron pathway to produce H2O/OH−. In order to explore the ORR pathway of the obtained Co3(PO4)2/N,P-GA-900, the rotating ring disk electrode (RRDE) experiments were performed. The electron transfer number (n) and percentage of hydrogen peroxide can be calculated according to the following equations (Liu et al., 2013).

Where ID is the disk current, IR is the ring current, and N (= 0.37) is the current collection efficiency of the Pt ring.

The RRDE test results present the disk and ring current density for Co3(PO4)2/N,P-GA-900 and Pt/C (Figure 8A). Figure 8B shows the yield of hydrogen peroxide (H2O2%) and the electron transfer number (n) at different potentials for the two catalysts. It can be observed that the percentage of H2O2 for Co3(PO4)2/N,P-GA-900 is less than 15%, and the calculated electron transfer number is 3.7–3.84 in the potential range of 0.3–0.6 V vs. RHE. These results suggest that the Co3(PO4)2/N,P-GA-900 catalyze ORR undergoes a predominant 4e process by reducing O2 directly to OH−.

Figure 8. (A) Rotating ring disk electrode (RRDE) measurements of Co3(PO4)2/N,P-GA-900 and Pt/C in 0.1 M KOH; (B) Peroxide percentage and electron transfer number (inset) at different potentials based on the corresponding RRDE data in (A).

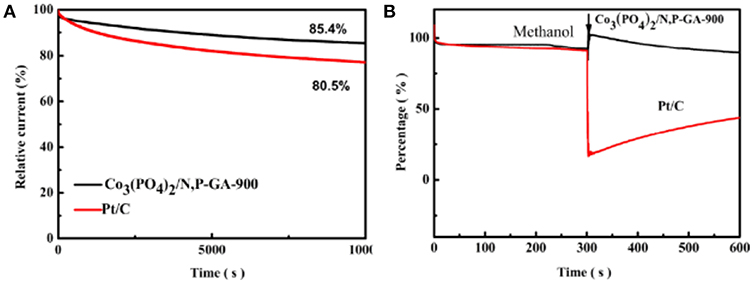

Methanol poisoning and the durability are significant matters challenging the cathode catalysts in current fuel cell devices (Yu et al., 2012; Jin et al., 2014). For estimating the long-term stability of the Co3(PO4)2/N,P-GA-900 hybrid, the chronoamperometry test over a period of 10,000 s at 1,600 rpm and 10 mV s−1 was conducted (see Figure 9A). Remarkably, the current retention of Co3(PO4)2/N,P-GA-900 is 85.4%, while Pt/C reserves only 80.5% of its initial current under the same conditions, indicating the better durability of the Co3(PO4)2/N,P-GA-900 catalyst relative to Pt/C. In order to explore the selectivity of Co3(PO4)2/N,P-GA-900, a methanol crossover test was conducted (Figure 9B). Obviously, the Co3(PO4)2/N,P-GA-900 hybrid demonstrates almost no distinct current density variation when 3 M methanol is injected, while the current density of the Pt/C decreases sharply under the same operation, manifesting the more excellent methanol tolerance of our as-prepared catalyst than Pt/C.

Figure 9. (A) Chronoamperometric curves of Co3(PO4)2/N,P-GA-900 and Pt/C in 0.1 M KOH solution saturated with O2 at a rotating speed of 1,600 rpm and the scan rate of 10 mV s −1; (B) Chronoamperometric response for ORR on Co3(PO4)2/N,P-GA-900 and Pt/C in O2-saturated 0.1 M KOH at a rotating speed of 1,600 rpm and the scan rate of 10 mV s −1 with 3 M methanol added after 300 s.

Conclusion

In summary, a novel Co3(PO4)2/N,P-GA electrocatalyst for ORR was prepared by a facile two-step method, including a hydrothermal reaction and subsequent pyrolysis treatment. The optimized Co3(PO4)2/N,P-GA-900 (where 900 represents the pyrolysis temperature) catalyst displays better ORR activity than the N,P-GA-900, Co/N-GA-900 and Co2P/P-GA-900, which is ascribed to the synergistic effect between Co3(PO4)2 and N,P-GA-900. In addition, the as-obtained Co3(PO4)2/N,P-GA-900 also exhibits better operational stability and methanol tolerance than the commercial Pt/C. Therefore, this work may offer the basis to prepare Co,N,P-tridoped graphene aerogel with hierarchical porosity, and provide an unprecedented avenue to design more three-dimensional electrocatalysts as a replacement to noble metals for electrochemical energy conversion and storage devices.

Author Contributions

L-LX makes substantial contributions to conception and design. X-JL makes contributions to acquisition of data. XW makes contributions to analysis and interpretation of data.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmats.2019.00022/full#supplementary-material

References

Chen, S., Duan, J., Jaroniec, M., and Qiao, S. Z. (2014). Nitrogen and oxygen dual-doped carbon hydrogel film as a substrate-free electrode for highly efficient oxygen evolution reaction. Adv. Mater. 26, 2925–2930. doi: 10.1002/adma.201305608

Chen, Y. Z., Wang, C., Wu, Z. Y., Xiong, Y., Xu, Q., Yu, S. H., et al. (2015). From bimetallic metal-organic framework to porous carbon: high surface area and multicomponent active dopants for excellent electrocatalysis. Adv. Mater. 27, 5010–5016. doi: 10.1002/adma.201502315

Cheon, J. Y., Kim, J. H., Kim, J. H., Goddeti, K. C., Park, J. Y., and Joo, S. H. (2014). Intrinsic relationship between enhanced oxygen reduction reaction activity and nanoscale work function of doped carbons. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136, 8875–8878. doi: 10.1021/ja503557x

Dai, L., Xue, Y., Qu, L., Choi, H. J., and Baek, J. B. (2015). Metal-free catalysts for oxygen reduction reaction. Chem. Rev. 115, 4823–4892. doi: 10.1021/cr5003563

Debe, M. K. (2012). Electrocatalyst approaches and challenges for automotive fuel cells. Nature 486, 43–51. doi: 10.1038/nature11115

Fei, H., Dong, J., Arellano-Jime′nez, M. J., Ye, G., Kim, N. D., Errol, L. G., et al. (2015). Atomic cobalt on nitrogen-doped graphene for hydrogen generation. Nat. Commun. 6:8668. doi: 10.1038/ncomms9668

Fu, X., Choi, J. Y., Zamani, P., Jiang, G., Hoque, M. A., Hassan, F. M., et al. (2016). Co-N decorated hierarchically porous graphene aerogel for efficient oxygen reduction reaction in acid. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 8, 6488–6495. doi: 10.1021/acsami.5b12746

Geim, A. K., and Novoselov, K. S. (2007). The rise of graphene. Nat. Mater. 6, 183–191. doi: 10.1038/nmat1849

Gong, K., Du, F., Xia, Z., Durstock, M., and Dai, L. (2009). Nitrogen-doped carbon nanotube arrays with high electrocatalytic activity for oxygen reduction. Science 323, 760–764. doi: 10.1126/science.1168049

Gonzalez-Flores, D., Sanchez, I., Zaharieva, I., Klingan, K., Heidkamp, J., Chernev, P., et al. (2015). Heterogeneous water oxidation: surface activity versus amorphization activation in cobalt phosphate catalysts. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 54, 2472–2476. doi: 10.1002/anie.201409333

Goran, J. M., Phan, E. N. H., Favela, C. A., and Stevenson, K. J. (2015). H2O2 detection at carbon nanotubes and nitrogen-doped carbon nanotubes: oxidation, reduction, or disproportionation? Anal. Chem. 87, 5989–5996. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.5b00059

Hibino, T., Kobayashi, K., and Heo, P. (2013). Oxygen reduction reaction over nitrogen-doped graphene oxide cathodes in acid and alkaline fuel cells at intermediate temperatures. Electrochim. Acta 112, 82–89. doi: 10.1016/j.electacta.2013.08.101

Hou, Y., Huang, T., Wen, Z., Mao, S., Cui, S., and Chen, J. (2014a). Metal-organic framework-derived nitrogen-doped core-shell-structured porous Fe/Fe3C@C nanoboxes supported on graphene sheets for efficient oxygen reduction reactions. Adv. Energy Mater. 4:1400337. doi: 10.1002/aenm.201400337

Hou, Y., Wen, Z., Cui, S., Ci, S., Mao, S., and Chen, J. (2014b). An advanced nitrogen-doped graphene/cobalt-embedded porous carbon polyhedron hybrid for efficient catalysis of oxygen reduction and water splitting. Adv. Funct. Mater. 25, 872–882. doi: 10.1002/adfm.201403657

Hu, H., Han, L., Yu, M., Wang, Z., and Lou, X. W. (2016). Metal-organic-framework-engaged formation of Co nanoparticle-embedded carbon@Co9S8 double-shelled nanocages for efficient oxygen reduction. Energ. Environ. Sci. 9, 107–111. doi: 10.1039/C5EE02903A

Hu, Y., Liu, H., Ke, Q., and Wang, J. (2014). Effects of nitrogen doping on supercapacitor performance of a mesoporous carbon electrode produced by a hydrothermal soft-templating process. J. Mater. Chem. A 2, 11753–11758. doi: 10.1039/C4TA01269K

Jeon, I. Y., Zhang, S., Zhang, L., Choi, H. J., Seo, J. M., Xia, Z., et al. (2013). Edge-selectively sulfurized graphene nanoplatelets as efficient metal-free electrocatalysts for oxygen reduction reaction: the electron spin effect. Adv. Mater. 25, 6138–6145. doi: 10.1002/adma.201302753

Jiang, H., Zhu, Y., Feng, Q., Su, Y., Yang, X., and Li, C. (2014). Nitrogen and phosphorus dual-doped hierarchical porous carbon foams as efficient metal-free electrocatalysts for oxygen reduction reactions. Chem. Eur. J. 20, 3106–3112. doi: 10.1002/chem.201304561

Jin, J., Pan, F., Jiang, L., Fu, X., Liang, A., Wei, Z., et al. (2014). Catalyst-free synthesis of crumpled boron and nitrogen co-doped graphite layers with tunable bond structure for oxygen reduction reaction. ACS Nano 8, 3313–3321. doi: 10.1021/nn404927n

Kanan, M. W., and Nocera, D. G. (2008). In situ formation of an oxygen-evolving catalyst in neutral water containing phosphate and Co2+. Science 321, 1072–1075. doi: 10.1126/science.1162018

Katsounaros, I., Cherevko, S., Zeradjanin, A. R., and Mayrhofer, K. J. J. (2014). Oxygen electrochemistry as a cornerstone for sustainable energy conversion. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 53, 102–121. doi: 10.1002/anie.201306588

Kim, C., Lee, B., Park, Y., Park, B., Lee, J., and Kim, H. (2007). Iron-phosphate/platinum/carbon nanocomposites for enhanced electrocatalytic stability. Appl. Phys. Lett. 91, 113101. doi: 10.1063/1.2783035

Lai, L., Potts, J. R., Zhan, D., Wang, L., Poh, C. K., Tang, C., et al. (2012). Exploration of the active center structure of nitrogen-doped graphene-based catalysts for oxygen reduction reaction. Energ. Environ. Sci. 5, 7936–7942. doi: 10.1039/c2ee21802j

Li, J., Mao, S., Hou, Y., Lei, L., and Yuan, C. (2018). 3D Edge-enriched Fe3C@C nanocrystals with a core-shell structure grown on reduced graphene oxide networks for efficient oxygen reduction reaction. ChemSusChem 11, 3292–3298. doi: 10.1002/cssc.201801084

Liang, Y., Li, Y., Wang, H., and Dai, H. (2013). Strongly coupled lnorganic/nanocarbon hybrid materials for advanced electrocatalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135, 2013–2036. doi: 10.1021/ja3089923

Liu, Y., Wu, Y. Y., Lv, G. J., Pu, T., He, X. Q., and Cui, L. L. (2013). Iron(II) phthalocyanine covalently functionalized graphene as a highly efficient non-precious-metal catalyst for the oxygen reduction reaction in alkaline media. Electrochim. Acta 112, 269–278. doi: 10.1016/j.electacta.2013.08.174

Liu, Z. Q., Cheng, H., Li, N., Ma, T. Y., and Su, Y. Z. (2016). ZnCo2O4 quantum dots anchored on nitrogen-doped carbon nanotubes as reversible oxygen reduction/evolution electrocatalysts. Adv. Mater. 28, 3777–3784. doi: 10.1002/adma.201506197

Mao, S., Lu, G., and Chen, J. (2015). Three-dimensional graphene-based composites for energy applications. Nanoscale 7, 6924–6943. doi: 10.1039/C4NR06609J

Mao, S., Wen, Z., Huang, T., Hou, Y., and Chen, J. (2014). High-performance bi-functional electrocatalysts of 3D crumpled graphene-cobalt oxide nanohybrids for oxygen reduction and evolution reactions. Energ. Environ. Sci. 7, 609–616. doi: 10.1039/C3EE42696C

Maria Rosas, J., Ruiz-Rosas, R., Rodriguez-Mirasol, J., and Cordero, T. (2012). Kinetic study of the oxidation resistance of phosphorus-containing activated carbons. Carbon N. Y. 50, 1523–1537. doi: 10.1016/j.carbon.2011.11.030

Menezes, P. W., Indra, A., Gonzalez-Flores, D., Sahraie, N. R., Zaharieva, I., Schwarze, M., et al. (2015). High-performance oxygen redox catalysis with multifunctional cobalt oxide nanochains: morphology-dependent activity. ACS Catal. 5, 2017–2027. doi: 10.1021/cs501724v

Nasini, U. B., Bairi, V. G., Ramasahayam, S. K., Bourdo, S. E., Viswanathan, T., and Shaikh, A. U. (2014). Phosphorous and nitrogen dual heteroatom doped mesoporous carbon synthesized via microwave method for supercapacitor application. J. Power Sources 250:257–265. doi: 10.1016/j.jpowsour.2013.11.014

Ornelas, O., Sieben, J. M., Ruiz-Rosas, R., Morallon, E., Cazorla-Amoros, D., Geng, J., et al. (2014). On the origin of the high capacitance of nitrogen-containing carbon nanotubes in acidic and alkaline electrolytes. Chem. Comm. 50, 11343–11346. doi: 10.1039/C4CC04876H

Park, Y., Lee, B., Kim, C., Kim, J., Nam, S., Oh, Y., et al. (2010). Modification of Gold Catalysis with Aluminum Phosphate for Oxygen-Reduction Reaction. J. Phys. Chem. C 114, 3688–3692. doi: 10.1021/jp9103323

Razmjooei, F., Singh, K. P., Song, M. Y., and Yu, J. S. (2014). Enhanced electrocatalytic activity due to additional phosphorous doping in nitrogen and sulfur-doped graphene: a comprehensive study. Carbon N. Y. 78:257–267. doi: 10.1016/j.carbon.2014.07.002

Ren, X., Zelenay, P., Thomas, S., Davey, J., and Gottesfeld, S. (2000). Recent advances in direct methanol fuel cells at Los Alamos National Laboratory. J. Power Sources 86, 111–116. doi: 10.1016/S0378-7753(99)00407-3

Shanmugam, S., and Osaka, T. (2011). Efficient electrocatalytic oxygen reduction over metal free-nitrogen doped carbon nanocapsules. Chem. Comm. 47, 4463–4465. doi: 10.1039/c1cc10361j

Shao, Y., Park, S., Xiao, J., Zhang, J. G., Wang, Y., and Liu, J. (2012). Electrocatalysts for nonaqueous lithium-air batteries: status, challenges, and perspective. ACS Catal. 2, 844–857. doi: 10.1021/cs300036v

Some, S., Kim, J., Lee, K., Kulkarni, A., Yoon, Y., Lee, S., et al. (2012). Highly air-stable phosphorus-doped n-type graphene field-effect transistors. Adv. Mater. 24, 5481–5486. doi: 10.1002/adma.201202255

Steinmiller, E. M. P., and Choi, K. S. (2009). Photochemical deposition of cobalt-based oxygen evolving catalyst on a semiconductor photoanode for solar oxygen production. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 20633–20636. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0910203106

Walter, M. G., Warren, E. L., McKone, J. R., Boettcher, S. W., Mi, Q., Santori, E. A., et al. (2010). Solar water splitting cells. Chem. Rev. 110, 6446–6473. doi: 10.1021/cr1002326

Wang, H., and Dai, H. (2013). Strongly coupled inorganic-nano-carbon hybrid materials for energy storage. Chem. Soc. Rev. 42, 3088–3113. doi: 10.1039/c2cs35307e

Wang, H., Yang, Y., Liang, Y., Cui, L. F., Casalongue, H. S., Li, Y., et al. (2011a). LiMn1-xFexPO4 nanorods grown on graphene sheets for ultrahigh-rate-performance lithium ion batteries. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 50, 7364–7368. doi: 10.1002/anie.201103163

Wang, H., Yang, Y., Liang, Y., Robinson, J. T., Li, Y., Jackson, A., et al. (2011b). Graphene-wrapped sulfur particles as a rechargeable lithium-sulfur battery cathode material with high capacity and cycling stability. Nano Lett. 11, 2644–2647. doi: 10.1021/nl200658a

Wang, X., Cao, X., Bourgeois, L., Guan, H., Chen, S., Zhong, Y., et al. (2012). N-doped graphene-SnO2 sandwich paper for high-performance lithium-ion batteries. Adv. Funct. Mater. 22, 2682–2690. doi: 10.1002/adfm.201103110

Wang, X., Weng, Q., Liu, X., Wang, X., Tang, D. M., Tian, W., et al. (2014). Atomistic origins of high rate capability and capacity of N-doped graphene for lithium storage. Nano Lett. 14, 1164–1171. doi: 10.1021/nl4038592

Wang, Z., Jia, R., Zheng, J., Zhao, J., Li, L., Song, J., et al. (2011c). Nitrogen-promoted self-assembly of N-Doped carbon nanotubes and their intrinsic catalysis for oxygen reduction in fuel cells. ACS Nano 5, 1677–1684. doi: 10.1021/nn1030127

Xia, W., Zou, R., An, L., Xia, D., and Guo, S. (2015). A metal-organic framework route to in situ encapsulation of Co@Co3O4@C core@bishell nanoparticles into a highly ordered porous carbon matrix for oxygen reduction. Energ. Environ. Sci. 8, 568–576. doi: 10.1039/C4EE02281E

Yang, D. S., Bhattacharjya, D., Inamdar, S., Park, J., and Yu, J. S. (2012). Phosphorus-doped ordered mesoporous carbons with different lengths as efficient metal-free electrocatalysts for oxygen reduction reaction in alkaline media. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 16127–16130. doi: 10.1021/ja306376s

Yang, S., Feng, X., Wang, X., and Muellen, K. (2011). Graphene-based carbon nitride nanosheets as efficient metal-free electrocatalysts for oxygen reduction reactions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 50, 5339–5343. doi: 10.1002/anie.201100170

Yu, D., Xue, Y., and Dai, L. (2012). vertically aligned carbon nanotube arrays Co-doped with phosphorus and nitrogen as efficient metal-free electrocatalysts for oxygen reduction. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 3, 2863–2870. doi: 10.1021/jz3011833

Yu, G., Hu, L., Vosgueritchian, M., Wang, H., Xie, X., McDonough, J. R., et al. (2011). Solution-processed graphene/MnO2 nanostructured textiles for high-performance electrochemical capacitors. Nano Lett. 11, 2905–2911. doi: 10.1021/nl2013828

Yuan, H., Hou, Y., Wen, Z., Guo, X., Chen, J., and He, Z. (2015). Porous carbon nanosheets codoped with nitrogen and sulfur for oxygen reduction reaction in microbial fuel cells. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 7, 18672–18678. doi: 10.1021/acsami.5b05144

Zhan, Y., Lu, M., Yang, S., Xu, C., Liu, Z., and Lee, J. Y. (2016). Activity of transition-metal (manganese, iron, cobalt, and nickel) phosphates for oxygen electrocatalysis in alkaline solution. ChemCatChem 8, 372–379. doi: 10.1002/cctc.201500952

Zhang, C., Mahmood, N., Yin, H., Liu, F., and Hou, Y. (2013). Synthesis of phosphorus-doped graphene and its multifunctional applications for oxygen reduction reaction and lithium ion batteries. Adv. Mater. 25, 4932–4937. doi: 10.1002/adma.201301870

Zhang, J., Xia, Z., and Dai, L. (2015a). Carbon-based electrocatalysts for advanced energy conversion and storage. Sci. Adv. 1:e1500564. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.1500564

Zhang, J., Zhao, Z., Xia, Z., and Dai, L. (2015b). A metal-free bifunctional electrocatalyst for oxygen reduction and oxygen evolution reactions. Nat. Nanotechnol. 10, 444–452. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2015.48

Zhang, Q., Li, R., Zhang, M., Zhang, B., and Gou, X. (2014). SnS2/reduced graphene oxide nanocomposites with superior lithium storage performance. Electrochim. Acta 115, 425–433. doi: 10.1016/j.electacta.2013.10.193

Zheng, Y., Jiao, Y., Zhu, Y., Li, L. H., Han, Y., Chen, Y., et al. (2014). Hydrogen evolution by a metal-free electrocatalyst. Nat. Commun. 5:3783. doi: 10.1038/ncomms4783

Zhong, H. X., Wang, J., Zhang, Y. W., Xu, W. L., Xing, W., Xu, D., et al. (2014). ZIF-8 Derived graphene-based nitrogen-doped porous carbon sheets as highly efficient and durable oxygen reduction electrocatalysts. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 53, 14235–14239. doi: 10.1002/anie.201408990

Keywords: cobalt phosphate, graphene aerogel, electrocatalyst, N,P-codoped, oxygen reduction reaction

Citation: Xuan L-L, Liu X-J and Wang X (2019) Cobalt Phosphate Nanoparticles Embedded Nitrogen and Phosphorus-Codoped Graphene Aerogels as Effective Electrocatalysts for Oxygen Reduction. Front. Mater. 6:22. doi: 10.3389/fmats.2019.00022

Received: 14 November 2018; Accepted: 05 February 2019;

Published: 26 February 2019.

Edited by:

Jie-Sheng Chen, Shanghai Jiao Tong University, ChinaReviewed by:

Bao Yu Xia, Huazhong University of Science and Technology, ChinaYang Hou, Zhejiang University, China

Copyright © 2019 Xuan, Liu and Wang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Xiao-Jun Liu, MTcxMDIwOTYzQHFxLmNvbQ==

Xue Wang, MzQ5NTAwMjk2QHFxLmNvbQ==

Li-Li Xuan

Li-Li Xuan Xiao-Jun Liu*

Xiao-Jun Liu*