95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Mar. Sci. , 08 July 2020

Sec. Marine Ecosystem Ecology

Volume 7 - 2020 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2020.00494

This article is part of the Research Topic Small Scale Spatial and Temporal Patterns in Particles, Plankton, and Other Organisms View all 24 articles

Through in situ holographic imaging of undisturbed water, diatom colonies with high aspect ratios have been found to exhibit preferential horizontal orientation within high biomass subsurface layers. We analyzed holographic video to determine the abundance, size, and orientation of colonies over several vertical profiles from the surface to ~25 m depth. A geometric optics model based on these measurements was then used to estimate light absorption by phytoplankton throughout the water column. Results show a substantial increase in absorption of downwelling irradiance (up to 24.5%) for horizontally oriented colonies when compared to randomized orientations. The effect can be attributed to maximization of the projected area of colonies when oriented perpendicular to the direction of incident light. Formation of high aspect ratio cells and colonies may represent an adaptation to maximize light harvesting in low light environments through interaction with the low velocity shear fields commonly found along pycnoclines at the base of the surface mixed layer. The effect of orientation on light absorption by large chain forming diatoms could influence their abundance and distribution in the ocean as well as the broader structure and function of marine ecosystems.

Marine phytoplankton, responsible for approximately half of global primary production, are fundamental components of marine food webs and play a critical role in biogeochemical cycles linked to climate change (Field et al., 1998). Large phytoplankton (>20 μm) contribute substantially to the downward flux of carbon in the ocean, and large size classes are often dominated by diatoms that form cells or colonies with high aspect ratios (length/width > 10) (Boyd and Newton, 1995, 1999; Smetacek, 1999; Tréguer et al., 2018). It has generally been assumed that these non-spherical phytoplankton are randomly oriented throughout the water column due to turbulence (Basterretxea et al., 2020). However, recent observations using in situ holographic imaging suggest that preferential horizontal orientation may be a common occurrence in the ocean (Talapatra et al., 2013; Nayak et al., 2018). Theoretical and laboratory based experimental studies have shown that non-random orientations result from interaction of particles with low velocity shear fields (Jeffery, 1922; Karp-Boss and Jumars, 1998). In the ocean, shear fields capable of orienting particles can occur within the pycnocline, at the base of the surface mixed layer where phytoplankton biomass is often enhanced (e.g., thin layers or deep chlorophyll maxima, Sullivan et al., 2010b). The resulting orientation can influence light absorption by large phytoplankton and may have important ecological consequences for species-specific growth rates, community structure, and the efficiency of the biological pump (Basterretxea et al., 2020).

To survive in the aquatic environment, phytoplankton require light for photosynthesis and growth. Absorption of light by an individual phytoplankton cell or colony is a function of its size, shape, orientation, and the complex refractive index of its components (Morel and Bricaud, 1986; Bohren and Huffman, 1998). Size, shape, and orientation relative to incident light define the projected area of cells. Light intercepted within this projected area is attenuated exponentially along optical paths through cells by absorption and scattering. Light absorbed by photosynthetic pigments is used to drive the biochemical reactions of photosynthesis, ultimately providing the energy needed for growth. The exponential decrease in intensity results in the self-shading of intracellular photosynthetic pigments, also referred to as the “package effect” (Duysens, 1956; Kirk, 1976; Bricaud et al., 1983, 1995). This self-shading increases with cell size and reduces the total amount of light absorbed by a given amount of pigment (e.g., chlorophyll), cellular volume, or unit of biomass (e.g., carbon).

For non-spherical cells and colonies (most phytoplankton >20 μm, Fogg, 1991; Tomas, 1997), both the projected area and optical path lengths through cells change with orientation relative to the incident light direction. Particles with large aspect ratios, such as colonial diatoms, will maximize their projected area and minimize package effects when their major axis is oriented perpendicular to the direction of incident light. In the ocean, light mostly propagates vertically from surface to depth, therefore, horizontal orientation of elongate phytoplankton will tend to maximize light capture efficiency and increase chlorophyll or biomass specific absorption. In deep or turbid water where light is limiting, this may have a significant impact on rates of photosynthesis and growth.

Currently available methods cannot measure absorption by individual phytoplankton in their natural, undisturbed orientation. Bottle samplers and in situ absorption meters that require pumping of seawater through a reflective flow cell (e.g., ac meters from Sea-bird Scientific, Bellevue, WA) alter natural orientations and size distributions by subjecting particles, cells, and colonies to induced turbulent shear stress. Alternatively, phytoplankton size, shape, and orientation can be observed directly through imaging and their optical absorption can be subsequently modeled. Over the last two decades digital holographic techniques have been developed that can image phytoplankton in situ at video frame rates with minimal disturbance of their natural orientation (Katz et al., 1999; Katz and Sheng, 2010; Talapatra et al., 2013; Nayak et al., 2018). Holography overcomes the narrow depth of field associated with high magnification in standard optical imaging systems and allows for in-focus imaging of particles in a volume of sea water large enough to provide statistically meaningful observations (e.g., several mL). Optically important morphological characteristics of particles such as length, width, projected area, and orientation can be measured directly through automated analysis of reconstructed images.

Measured particle characteristics can be used to calculate optical properties through a variety of modeling techniques (Mishchenko et al., 2000; Kahnert, 2003; Wriedt, 2009). Previous studies have used optical modeling to investigate light scatter by oriented, non-spherical bacterial cells and found that optical backscatter could be enhanced by up to 30% under typical oceanic shear flows (Marcos et al., 2011). Unlike bacteria, however, many large phytoplankton cells and colonies have high aspect ratios (>10) and their Equivalent Spherical Diameter (ESD) is large compared to the wavelengths (λ) of light (size parameters πESD/λ > 150). This can be problematic for methods that explicitly solve Maxwell's Equations for simple particle geometries (i.e., Lorenz-Mie theory, T-Matrix). Finite difference time domain (FDTD) models can accommodate particles of any shape and orientation but are computationally expensive and impractical to compute for populations of many large particles with distinct characteristics. Although an approximation, geometric optics methods (i.e., ray tracing) are efficient to compute and provide accurate results for particles much larger in size than the wavelengths of incident visible light (Macke et al., 1995; Yang and Liou, 1995).

In this study we assess the effect of orientation on light absorption by natural phytoplankton populations. We measured the concentration, length, width, and vertical orientation of large phytoplankton colonies with a submersible digital holographic microscope and used geometric optics to model their light absorption over several depth profiles. The data was acquired in East Sound, WA (USA), a productive and hydrographically constrained coastal fjord where stratification and thin layers of phytoplankton are common (Dekshenieks et al., 2001; McManus et al., 2003).

In situ holographic video and optical measurements were acquired from East Sound, WA in September, 2015. East Sound is located at 48.64°N latitude, 122.87°W between the Strait of Juan de Fuca and Strait of Georgia. It is 13 km long, 2 km wide, has a mean depth of 30 m, and is surrounded on the north, east, and west by Orcas Island. The sound is open to the south but flow is restricted by a partial sill. Currents and mixing are primarily driven by wind and tides. Due to its depth and restricted hydrography, the water column is often strongly stratified and thin layers of phytoplankton frequently form along the pycnocline (Dekshenieks et al., 2001; Rines et al., 2002). Multiple profiles were conducted over a 2 week field effort, and a subset of three with the highest particle concentrations and strongest orientation were selected for modeling of particulate absorption. The three profiles presented here were collected near the middle of the sound on the morning of September 22nd.

The digital holographic microscope (HOLOCAM) used an in-line configuration to image diffraction patterns produced by cells, colonies, and other particles over a 4 cm open path. The design consisted of two waterproof housings containing an Imperx digital camera and laser light source connected by a rigid support. The 660 nm nanosecond pulsed laser was spatially filtered, expanded, and collimated to produce a coherent plane wave light source. An objective lens in front of the camera was used to increase magnification and position the holographic imaging plane near the edge of the sample volume. The hologram field of view was 9.39 × 9.39 mm, the resolution was 4.58 μm pixel−1, and the total volume imaged per frame was 3.53 mL. Digital holographic video (2,048 × 2,048 pixels) was acquired and viewed in real time at 15 frames per second as the instrument descended slowly through the water column. Video was recorded on a shipboard disk array connected to the submersible unit by a fiber optic cable. The submersible housings had a smooth, hydrodynamic shape designed to minimize any turbulent shear within the sample volume that could alter natural particle orientations when vertically profiling at 5–10 cm per second (Nayak et al., 2018).

The submersible instrument package also included a Sea-Bird Scientific SBE 49 FastCAT conductivity, temperature, and depth sensor (CTD), a WET Labs ac9 multispectral optical absorption and attenuation meter, a WET Labs bb9 multispectral optical backscatter sensor, a WET Labs DH-4 data logger, and a Nortek Vector acoustic doppler velocimeter (ADV) with an inertial motion unit (IMU). The CTD provided information on package depth, descent rate, and water column structure in real time. Data from the ADV IMU was used to correct for package tilt during deployment. Optical sensors were used to determine chlorophyll and particle distributions throughout the water column with high vertical resolution. The ac9 measured the total absorption coefficient, apg, including particulate and dissolved water components. The instrument was calibrated and data was corrected according to Twardowski et al. (1999) and Stockley et al. (2017). The bb9 backscatter sensor was calibrated and the backscatter coefficient bb was determined according to Sullivan et al. (2013). Chlorophyll was calculated from apg spectra using the line height method and a chlorophyll specific absorption line height of 0.0104 m2 mg–1 at 676 nm (Roesler and Barnard, 2013; Nardelli and Twardowski, 2016). The complete instrument package was slightly negatively buoyant and allowed to freely descend through the water column during data acquisition at a rate of 5–6 cm s–1 decoupled from ship motion (Cowles et al., 1998; Rines et al., 2010; Sullivan et al., 2010a). The package was deployed from a 50 foot vessel that remained anchored during data collection to minimize drag on the instrument package. All measurements, including holographic video frames, were associated with a common time stamp that was used to align data points in post processing.

Depth integrated net tows using a 20 μm mesh net were conducted in coordination with profiles. The net was lowered by hand from the surface to ~15 m depth over a period of 5–10 minutes while the research vessel was anchored. Current flow past the ship ensured adequate volumes of water were captured by the net. Contents of the net tow samples were analyzed immediately on board the research vessel with a compound microscope at 100x to 400x magnification. Phytoplankton were identified to the lowest taxonomic level possible in water mounts using phase contrast illumination. Identifications were based on morphological features that could be visualized with light microscopy following published descriptions of taxa (Round et al., 1990; Tomas, 1997; Hoppenrath et al., 2009, and references therein) and extensive previous work conducted in the area (Rines et al., 2002; McManus et al., 2003; Menden-Deuer, 2008; McFarland et al., 2015). Identification of taxa was used to choose appropriate estimates of previously published intracellular chlorophyll concentrations needed for modeling, to provide an ecological context to results, and to better interpret holographic images which were more limited in resolution than standard microscopy.

Processing of digital holograms consisted of background subtraction, image reconstruction throughout the sample volume, and formation of an extended depth of field (EDF) image. The subtracted background image was an average of a subset of frames (≥ 50) recorded over each depth profile. Digital holograms were numerically reconstructed using the Kirchhoff-Fresnel convolution kernel (Katz and Sheng, 2010). Reconstruction was performed for 80 focal planes spaced at 500 μm intervals over the 4 cm sample path. The gradient of each reconstructed plane was divided into 32 × 32 pixel windows and a composite, EDF image was generated by selecting the windows from all planes with the greatest number of pixels above a fixed threshold value. The threshold was pre-determined manually for a subset of reconstructed planes and subsequently applied to all holograms. To avoid duplicate imaging of particles and reduce the total computation time, only every third frame from the holographic video was processed resulting in an effective frame rate of 5 per second.

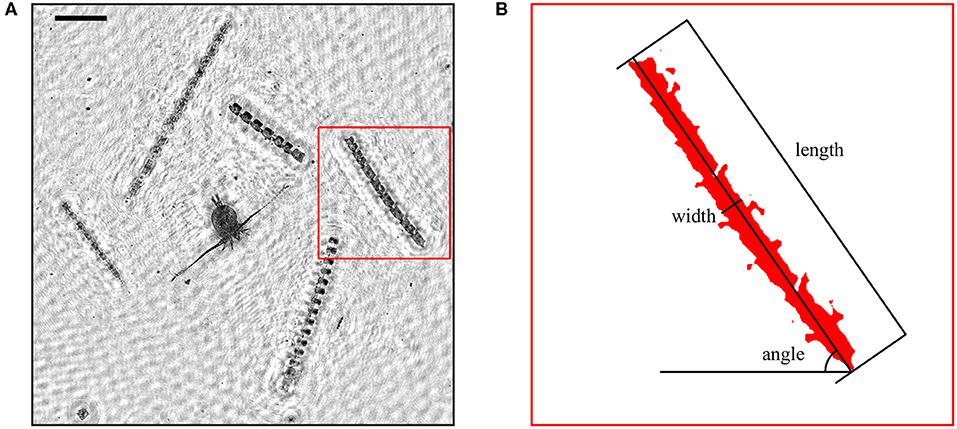

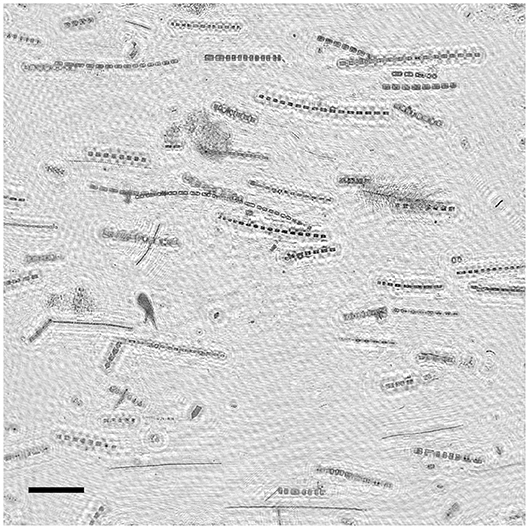

Analysis of EDF images included frequency filtering, segmentation, and region analysis. EDF images were first processed with a band-pass Gaussian frequency filter to reduce high frequency noise and low frequency artifacts (e.g., uneven background intensity). Images were then segmented by thresholding at a fixed, pre-determined intensity value. As for EDF image generation, the intensity threshold was determined manually for a subset of images and later applied to all images. Regions within 10 pixels (45.8 μm) distance from each other were merged to compensate for the fragmentation of regions caused by segmentation. The major axis orientation of each region was determined from the eigenvectors and eigenvalues of the covariance matrix of the segmented region's pixel coordinates (second order central moments). Measured angles ranged from 0–90 degrees. Small angles indicated horizontal orientation while angles close to 90 degrees indicated vertical orientation. The length of each region was defined as the Feret diameter (caliper diameter) along the direction of the major axis. Width was determined by scanning along the major axis and computing the mean of all scan lengths perpendicular to the major axis. Figure 1 illustrates the orientation, length, and width measurements for a typical diatom colony. Regions smaller than 100 μm (22 pixels) in length or with an aspect ratio smaller than 3 were ignored to focus only on particles with sizes and shapes capable of measurable orientation in response to small scale shear fields. These criteria effectively isolated long chain forming diatom colonies from other particles in EDF images. The orientation distribution throughout the water column (i.e., the number of particles at a given orientation and depth) was determined using a two dimensional Gaussian kernel density estimator with standard deviations of 2 degrees and 25 cm calculated over 128 bins in each dimension.

Figure 1. (A) A portion of an extended depth of field (EDF) image obtained after holographic reconstruction showing multiple colonies of Ditylum brightwellii and a copepod. Scale bar (upper left) represents 500 μm. (B) Illustration of the length, width, and angle measurements from image analysis for one D. brightwellii colony.

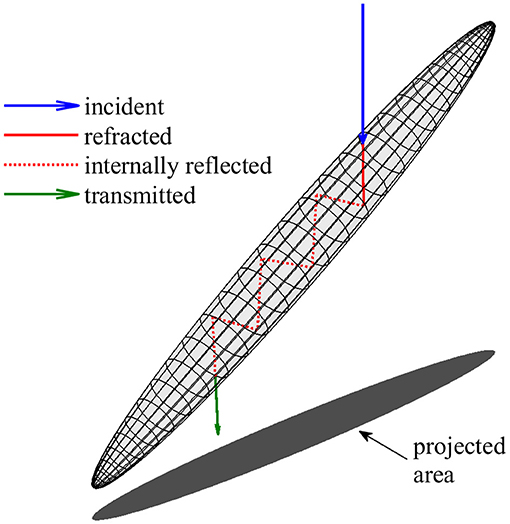

A simplified geometric optics model based on the method of Yang and Liou (1995, 1996) was used to estimate the absorption cross sections of individual diatom colonies at a wavelength of 676 nm, the red chlorophyll absorption peak. This ray tracing approach was selected for its ability to model large, high aspect ratio particles at any orientation relative to incident light with greater computational efficiency than other available methods. To focus exclusively on diatom colonies capable of orientation, the absorption cross section was modeled only for particles in EDF images larger than 100 μm in length and with an aspect ratio greater than 3. Particles were represented as prolate spheroids with major and minor axes lengths determined from image analysis as described above. For each spheroid, the model determined absorptance (the proportion of incident radiant flux absorbed) along ray paths while accounting for external surface reflection, refraction, and internal reflection according to the Fresnel equations (Figure 2) (Kirk, 1994; Yang and Liou, 1996; Bohren and Huffman, 1998; Hecht, 2002). All rays originated from above and included 6 internal reflections. Absorptance along intracellular ray paths was calculated from the decrease in intensity according to the Beer-Lambert law using an absorption coefficient for intracellular material (acm) based on a range of possible intracellular chlorophyll concentrations (Ci). The absorption cross section (Sa) for each spheroid was determined by numerical integration (Shampine, 2008) of absorptance over its projected area (σ). The absorption efficiency (Qa) was calculated as:

This dimensionless parameter describes the ratio of light absorbed by the particle to the light incident on its projected area in the direction of propagation (Morel and Bricaud, 1981). Vertical profiles of the phytoplankton absorption coefficient (aph m−1) for the modeled populations were then computed by summing particle absorption cross sections within ~20 cm vertical depth bins and dividing by the volume analyzed (V) in each bin.

For all particles, we assumed a real refractive index of 1.035 relative to water (Aas, 1996) and a uniform intracellular chlorophyll distribution. Since Ci can vary substantially but could not be measured directly for modeled phytoplankton, results were computed for three different concentrations including 0.3, 1.0, and 3.0 kg m−3 following the range of values for diatoms reported in the literature (Morel and Bricaud, 1986; Haardt and Maske, 1987; Bricaud et al., 1988; Osborne and Geider, 1989; Agustí, 1991; Álvarez et al., 2017). The absorption coefficient of the intracellular material (acm) was calculated as the product of Ci and a chlorophyll specific absorption coefficient, , at 676 nm. A value of 0.014 m2 mg–1 was used for , appropriate for the large coastal phytoplankton found in East Sound (Bricaud et al., 1995; Roesler and Barnard, 2013).

Figure 2. Illustration of the geometric optics model used to estimate absorption by diatom colonies. Cells and colonies are represented by prolate spheroids with major axes, minor axes, and orientation determined from image analysis (Figure 1). Modeled ray paths originated from above and included 6 internal reflections. Absorption cross section was determined from the decrease in radiant flux along internal ray paths (shown in red) and integration over the vertically projected area.

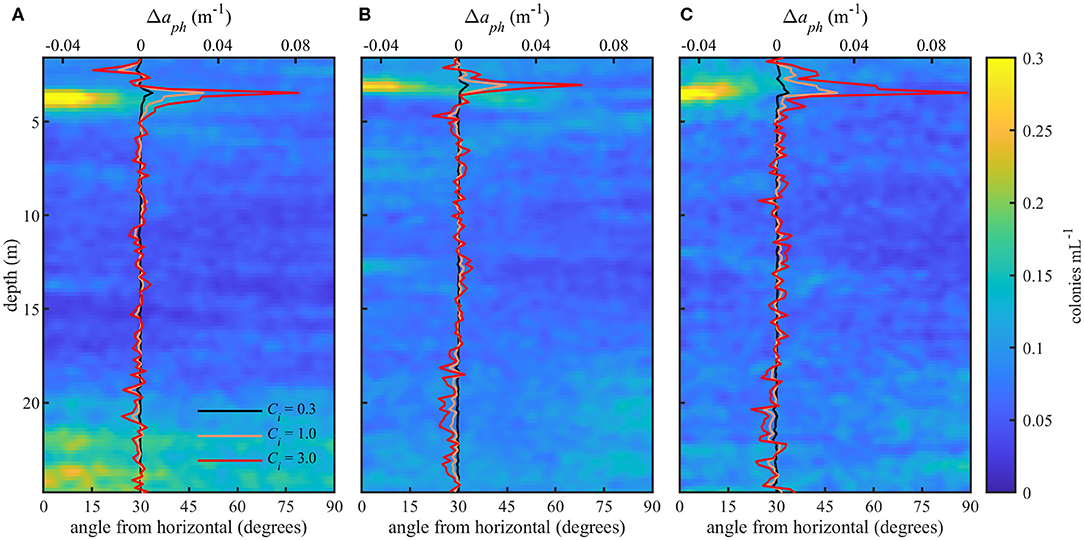

Vertical profiles of aph at 676 nm were modeled for phytoplankton populations in their measured orientations (aph) and in simulated random orientations () by assigning randomly generated angles to all spheroids. Random angles were assigned five times and was determined as the mean over all randomized orientations. We computed the parameter Δaph as the difference between aph and (). Δaph, therefore, represents the effect of the measured, non-random orientation distribution on absorption. Positive values indicate a net increase in aph relative to random orientations while negative values indicate a net decrease.

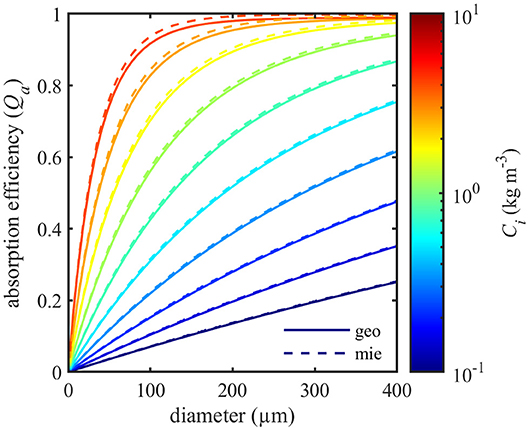

Accuracy of the geometric optics model was assessed by comparison with Lorenz-Mie theory for homogeneous spheres of various diameter and complex refractive index (Bohren and Huffman, 1998). The imaginary part of the complex refractive index (n′) was calculated according to Morel and Bricaud (1986):

Where acm is the intracellular absorption coefficient at wavelength λ (676 nm) and m is the corresponding refractive index of sea water (1.3368) at a temperature of 12°C and salinity of 30 PSU (Quan and Fry, 1995). Model estimates of Qa at 676 nm were compared for intracellular chlorophyll concentrations between 0.1 and 4 kg m–3 and cell diameters ranging from 2 to 400 μm (Figure 3). The geometric optics model produced slightly smaller estimates of absorption than Lorenz-Mie theory. Comparison of model outputs showed that absorption efficiencies varied by less than 2.5% between the two models for this range of sizes and refractive indices. The largest difference between the models was found at high intracellular chlorophyll concentrations for 60 μm diameter spheres. Differences decreased with increasing particle size.

Figure 3. Comparison of absorption efficiencies (Qa) at 676 nm calculated with geometric optics (geo, solid lines) and Lorenz-Mie theory (mie, dashed lines) for spheres of various size and intracellular chlorophyll content (Ci).

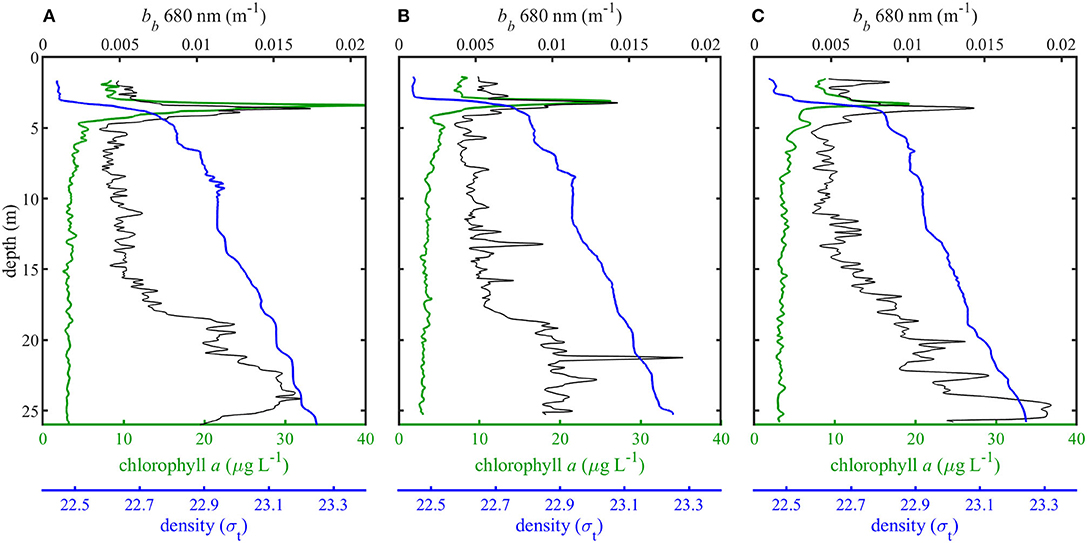

Vertical profiles of density, backscatter, and chlorophyll a for three separate casts revealed shallow thin layers of high phytoplankton biomass along the pycnocline (Figure 4). EDF images reconstructed from in situ holographic video showed these thin layers to be composed primarily of the colonial diatom Ditylum brightwellii (Figure 5). Other less abundant chain forming diatoms included Eucampia zodiacus, various species of Chaetoceros, Dactyliosolen fragillisimus, Skeletonema sp., Stephanopyxis turris, Leptocylindrus danicus, Cerataulina pelagica, and Pseudo-nitzschia sp. Phytoplankton samples collected with a net tow and examined with a conventional microscope confirmed these identifications. Backscatter profiles also show an increase in non-algal or detrital particles at depths >15 m, most likely due to sinking detrital material and particle flocculation (Figure 4, Alldredge et al., 2002; Sullivan et al., 2005; McFarland et al., 2015).

Figure 4. Density (σt), chlorophyll a concentrations (μg L−1), and backscatter (m−1) for each of three vertical profiles (A–C).

Figure 5. Example extended depth of field image from the phytoplankton thin layer in profile C showing predominantly horizontal orientation of diatom colonies. Scale bar (lower left) represents 1 mm.

Preferential horizontal orientation of long diatom chains was clearly visible in EDF images acquired within the thin layer (Figure 5). The orientation distributions for each profile (Figure 6) revealed high concentrations of large (>100 μm), horizontally oriented particles at 3–4 m depth with angles below ~20 degrees. Particle concentrations were lower and orientation distributions were more uniform above and below the thin layer. As seen with backscatter, particle concentrations determined from image analysis were also higher at depths >20 m, especially in profile A (Figure 6A), most likely due to sinking and flocculating detritus (Alldredge et al., 2002). Total modeled particle concentrations for all orientations ranged from 5.45 to 22.3 particles mL−1. The mean volume analyzed for estimates of aph at each depth was 61.2 mL. This varied somewhat with the descent rate of the instrument package (standard deviation of 24.2 mL).

Figure 6. Orientation distributions (bottom x-axis) for three profiles (A–C) and modeled change in absorption (Δaph) due to orientation (top x-axis) at 0.3, 1.0, and 3.0 kg m−3 intracellular chlorophyll concentrations (Ci). Color scale shows the concentration of colonies at a particular depth and orientation. Modeled Δaph values are the difference between measured and simulated random orientations.

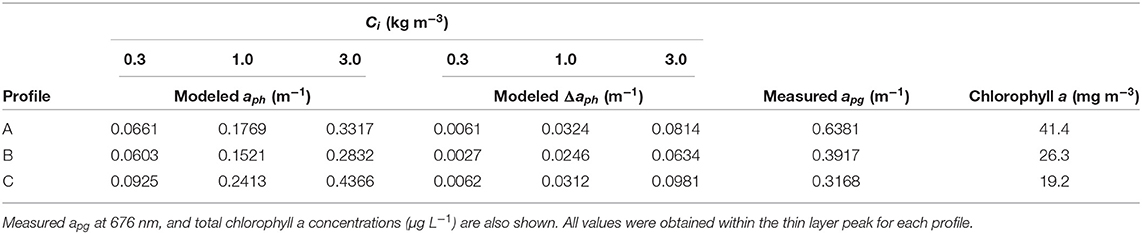

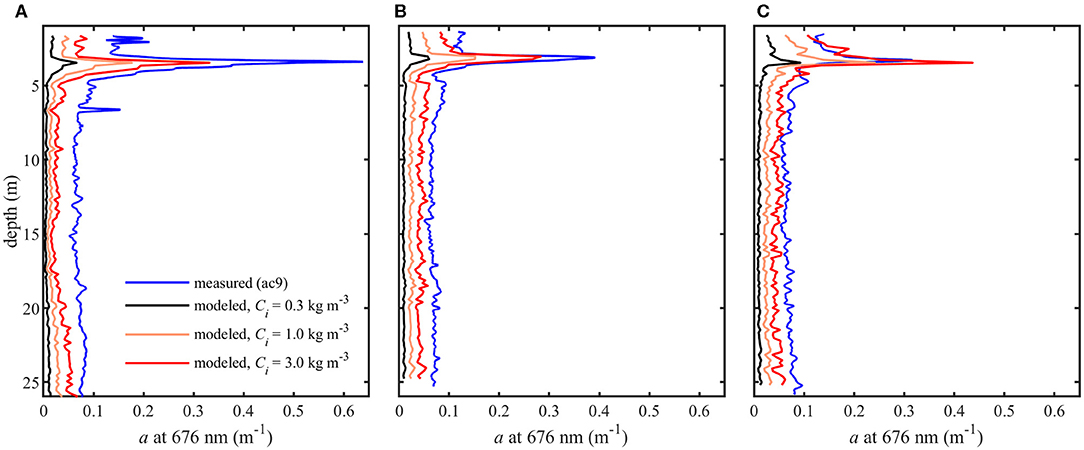

Model results show absorption peaks in vertical profiles corresponding to the depth of the thin layer (Figure 7). Modeled aph (676 nm) at the thin layer peak for each Ci is shown in Table 1. Intracellular chlorophyll a concentrations had a substantial impact on modeled values of aph which increased approximately five fold between the lowest and highest values of Ci (0.3 and 3 kg m−3) at the thin layer peak. A slight increase in modeled aph values at depths >20 m was seen in profile A (Figure 7), but no increase was observed in measured apg at these depths despite higher backscatter (Figure 4).

Table 1. aph and Δaph (m−1) at 676 nm modeled for colonial diatoms using three Ci values (0.3, 1.0, and 3.0 kg m−3).

Figure 7. Modeled phytoplankton absorption coefficients (aph) at 0.3, 1.0, and 3.0 kg m−3 intracellular chlorophyll concentrations (Ci) and measured total absorption coefficients (apg) at 676 nm for three profiles (A–C).

The effect of orientation on absorption, Δaph, is shown in Table 1 and in Figure 6 overlaid on the observed orientation distributions for each profile. We found positive modeled values of Δaph for colonies within the thin layer. Δaph also increased with increasing Ci. When compared to modeled and measured absorption (Table 1), values of Δaph ranged from 4.5 to 24.5% of modeled aph and from 0.7 to 31% of measured apg. There was no increase in Δaph at depths >20 m in profile A despite indication of some preferential horizontal orientation.

The optical model used in this study showed an increase in absorption of 4.5–24.5% for populations of horizontally oriented diatom colonies relative to random orientations. Computations were based on the measured orientation and size distribution of a natural phytoplankton community, and the modeled effects were repeated over three separate profiles. Results suggest that horizontal orientation helps maximize light absorption by relatively large (>100 μm length), high aspect ratio (length/width > 3) phytoplankton. This may allow horizontally oriented cells and colonies to achieve higher rates of photosynthesis and growth under light limited conditions.

An increase in modeled values of Δaph within the thin layer indicated an increase in phytoplankton absorption caused by their horizontal orientation. At depths >20 m, however, the relative proportion of horizontally oriented particles in profile A (Figure 6) appeared insufficient to influence values of Δaph. The increase in Δaph with increasing Ci showed the effect of orientation on absorption was more pronounced for higher intracellular pigment concentrations. As expected, measured values of apg were generally higher than modeled values since we modeled aph for only a portion of the phytoplankton community and measured apg included some absorption by dissolved organic material. However, modeled aph exceeded measured values at the thin layer peak in profile C for the highest Ci value (Table 1). This may be due to the instruments measuring different parcels of water, or may indicate that a Ci value of 3.0 kg m−3 was not representative of these phytoplankton. Alternatively, it may indicate an underestimation of apg by the ac meter which randomizes particle orientations within the instrument's pumped flow cell.

The increase in absorption can be primarily attributed to an increase in the projected area of colonies as their major axes become perpendicular to the direction of incident light. Assuming incident illumination from above, horizontal orientation results in a net increase in absorption cross section (Sa = σQa) despite a decrease in Qa relative to vertical. For a typical D. brightwellii colony with a width of 50 μm, length of 800 μm, and Ci of 1.0 kg m–3, Qa decreases by half while σ increases by a factor of 16 as orientation changes from vertical to horizontal. The effect is especially pronounced for cells with high Ci since Qa remains high in any orientation. Closer inspection of model output shows almost all absorption occurs over the initial refracted internal ray path and the path of the first internal reflection. These path lengths are longer for vertical orientations resulting in higher Qa and greater self shading of pigments (i.e., package effects).

In this study, horizontally oriented colonies were found in a shallow (3–4 m deep) thin layer of high phytoplankton biomass along the pycnocline. Previous studies have shown similar particle orientation within regions of low velocity shear and low turbulent dissipation (Talapatra et al., 2013; Nayak et al., 2018). Orientation distributions of these natural particle assemblages closely match those predicted by physical models of spheroidal particle motion in simple shear flow (Jeffery, 1922; Nayak et al., 2018). The low shear conditions that promote horizontal orientation can be found along density gradients and at the base of surface mixed layers throughout the ocean. Such locations likely represent an ecological niche for which elongate, colonial diatoms are well-adapted. Their interaction with small scale shear fields could be considered a form of passive heliotropism, similar to the solar tracking behavior of plant leaves (Niinemets, 2010; Kutschera and Briggs, 2016). Large diatoms may even adjust their buoyancy to remain within layers of low shear to optimize light and nutrient resource acquisition (Moore and Villareal, 1996; Richardson et al., 1996; Cullen and MacIntyre, 1998; Klausmeier and Litchman, 2001).

Enhanced light absorption by horizontally oriented diatom colonies could also have an impact on phytoplankton community structure and the biological pump. Phytoplankton growth is often light limited at the base of surface mixed layers. Even a modest increase in absorption under these light limited conditions is likely to substantially increase rates of photosynthesis and growth (Edwards et al., 2015). Orientation may allow large chain forming diatoms to more effectively compete for available light at depths where shear is low (Litchman and Klausmeier, 2001; Yoshiyama et al., 2009). These large forms also sink more readily, transport carbon more efficiently to depth, and their relative abundance may influence net carbon export from surface layers (Smetacek, 1999; Tréguer et al., 2018).

Although the model incorporated fundamental morphological features of diatom colonies such as length and width, prolate spheroids provided only a coarse approximation of true diatom morphology. The shape and three dimensional structure of actual cells and colonies is considerably more complex (Round et al., 1990). The model also assumes a homogeneous intracellular distribution of chlorophyll. In eukaryotic phytoplankton cells, however, chlorophyll is embedded in thylakoid membranes and packaged within chloroplasts that have a variable and non-uniform distribution throughout the cell. Furthermore, incident light within the model came directly from above and propagated straight down. The actual propagation of light in the ocean is not so simple or uniform, although natural light fields are dominated by downwelling light (Kirk, 1994; Mobley, 1994). Despite lacking these more detailed morphological and optical features, we believe the modeled results reflect a substantial effect of orientation on light harvesting by colonial diatoms and other elongate forms. The effect appears strong enough to have important ecological consequences to the broader structure and function of marine ecosystems.

The datasets generated for this study are available on request to the corresponding author.

MM was responsible for collection and processing of holograms, analysis of holographic data, optical modeling, and manuscript preparation. AN also participated in holographic data collection, processing, and analysis, and assisted with manuscript preparation. NS assisted with data collection and was responsible for processing of optical data. MT and JS coordinated field data collection and provided project guidance. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding for this study was provided by the Office of Naval Research, Coastal Geophysics Program, contract # N00014-15-1-2628 (MT and JS). MM, AN, and JS were also supported by National Science Foundation grants OCE-1657332 and OCE-1634053.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

We thank Alan Weidemann, Bradley Penta, and the Naval Research Laboratory for their assistance and participation in the field research for this project.

Aas, E. (1996). Refractive index of phytoplankton derived from its metabolite composition. J. Plankton Res. 18, 2223–2249. doi: 10.1093/plankt/18.12.2223

Agustí, S. (1991). Allometric scaling of light absorption and scattering by phytoplankton cells. Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 48, 763–767. doi: 10.1139/f91-091

Alldredge, A. L., Cowles, T. J., MacIntyre, S., Rines, J. E. B., Donaghay, P. L., Greenlaw, C. F., et al. (2002). Occurrence and mechanisms of formation of a dramatic thin layer of marine snow in a shallow Pacific fjord. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 233, 1–12. doi: 10.3354/meps233001

Álvarez, E., Nogueira, E., and López-Urrutia, N. (2017). In-vivo single-cell fluorescence and the size-scaling of phytoplankton chlorophyll content. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 83:e03317-16. doi: 10.1128/AEM.03317-16

Basterretxea, G., Font-Munoz, J. S., and Tuval, I. (2020). Phytoplankton orientation in a turbulent ocean: a microscale perspective. Front. Mar. Sci. 7:185. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2020.00185

Bohren, C. F., and Huffman, D. R. (1998). Absorption and Scattering of Light by Small Particles. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons. doi: 10.1002/9783527618156

Boyd, P., and Newton, P. (1995). Evidence of the potential influence of planktonic community structure on the interannual variability of particulate organic carbon flux. Deep Sea Res. I Oceanogr. Res. Pap. 42, 619–639. doi: 10.1016/0967-0637(95)00017-Z

Boyd, P. W., and Newton, P. P. (1999). Does planktonic community structure determine downward particulate organic carbon flux in different oceanic provinces? Deep Sea Res. I Oceanogr. Res. Pap. 46, 63–91. doi: 10.1016/S0967-0637(98)00066-1

Bricaud, A., Babin, M., Morel, A., and Claustre, H. (1995). Variability in the chlorophyll-specific absorption coefficients of natural phytoplankton: analysis and parameterization. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 100, 13321–13332. doi: 10.1029/95JC00463

Bricaud, A., Bedhomme, A. L., and Morel, A. (1988). Optical properties of diverse phytoplanktonic species: experimental results and theoretical interpretation. J. Plankton Res. 10, 851–873. doi: 10.1093/plankt/10.5.851

Bricaud, A., Morel, A., and Prieur, L. (1983). Optical efficiency factors of some phytoplankters. Limnol. Oceanogr. 28, 816–832. doi: 10.4319/lo.1983.28.5.0816

Cowles, T. J., Desiderio, R. A., and Carr, M. E. (1998). Small-scale planktonic structure: persistence and trophic consequences. Oceanography 11, 4–9. doi: 10.5670/oceanog.1998.08

Cullen, J. J., and MacIntyre, J. G. (1998). Behavior, physiology and the niche of depth-regulating phytoplankton. Nato ASI Ser. G Ecol. Sci. 41, 559–580.

Dekshenieks, M. M., Donaghay, P. L., Sullivan, J. M., Rines, J. E. B., Osborn, T. R., and Twardowski, M. S. (2001). Temporal and spatial occurrence of thin phytoplankton layers in relation to physical processes. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 223, 61–71. doi: 10.3354/meps223061

Duysens, L. N. M. (1956). The flattening of the absorption spectrum of suspensions, as compared to that of solutions. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 19, 1–12. doi: 10.1016/0006-3002(56)90380-8

Edwards, K. F., Thomas, M. K., Klausmeier, C. A., and Litchman, E. (2015). Light and growth in marine phytoplankton: allometric, taxonomic, and environmental variation. Limnol. Oceanogr. 60, 540–552. doi: 10.1002/lno.10033

Field, C. B., Behrenfeld, M. J., Randerson, J. T., and Falkowski, P. (1998). Primary production of the biosphere: Integrating terrestrial and oceanic components. Science 281, 237–240. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5374.237

Fogg, G. E. (1991). Tansley review No. 30. The phytoplanktonic ways of life. N. Phytol. 118, 191–232. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.1991.tb00974.x

Haardt, H., and Maske, H. (1987). Specific in vivo absorption coefficient of chlorophyll a at 675 nm. Limnol. Oceanogr. 32, 608–619. doi: 10.4319/lo.1987.32.3.0608

Hoppenrath, M., Elbrachter, M., and Drebes, G. (2009). Marine Phytoplankton. Stuttgart: Schweizerbart Science Publishers.

Jeffery, G. B. (1922). The Motion of Ellipsoidal Particles Immersed in a Viscous Fluid. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. Ser. A 102, 161–179. doi: 10.1098/rspa.1922.0078

Kahnert, F. M. (2003). Numerical methods in electromagnetic scattering theory. J. Quant. Spectrosc. Radiat. Transfer 79–80, 775–824. doi: 10.1016/S0022-4073(02)00321-7

Karp-Boss, L., and Jumars, P. A. (1998). Motion of diatom chains in steady shear flow. Limnol. Oceanogr. 43, 1767–1773. doi: 10.4319/lo.1998.43.8.1767

Katz, J., Donaghay, P. L., Zhang, J., King, S., and Russell, K. (1999). Submersible holocamera for detection of particle characteristics and motions in the ocean. Deep Sea Res. I 46, 1455–1481. doi: 10.1016/S0967-0637(99)00011-4

Katz, J., and Sheng, J. (2010). Applications of holography in fluid mechanics and particle dynamics. Annu. Rev. Fluid Mech. 42, 531–555. doi: 10.1146/annurev-fluid-121108-145508

Kirk, J. T. O. (1976). A theoretical analysis of the contribution of algal cells to the attenuation of light within natural waters. III. Cylindrical and spheroidal cells. N. Phytol. 77, 341–358. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.1976.tb01524.x

Kirk, J. T. O. (1994). Light and Photosynthesis in Aquatic Ecosystems, 2nd Edn. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi: 10.1017/CBO9780511623370

Klausmeier, C. A., and Litchman, E. (2001). Algal games: The vertical distribution of phytoplankton in poorly mixed water columns. Limnol. Oceanogr. 46, 1998–2007. doi: 10.4319/lo.2001.46.8.1998

Kutschera, U., and Briggs, W. R. (2016). Phototropic solar tracking in sunflower plants: an integrative perspective. Ann. Bot. 117, 1–8. doi: 10.1093/aob/mcv141

Litchman, E., and Klausmeier, C. A. (2001). Competition of phytoplankton under fluctuating light. Am. Natural. 157, 170–187. doi: 10.1086/318628

Macke, A., Mishchenko, M. I., Muinonen, K., and Carlson, B. E. (1995). Scattering of light by large nonspherical particles: ray-tracing approximation versus T-matrix method. Optics Lett. 20:1934. doi: 10.1364/OL.20.001934

Marcos Seymour, J. R., Luhar, M., Durham, W. M., Mitchell, J. G., Macke, A., et al. (2011). Microbial alignment in flow changes ocean light climate. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108, 3860–3864. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1014576108

McFarland, M. N., Rines, J., Sullivan, J., and Donaghay, P. (2015). Impact of phytoplankton size and physiology on particulate optical properties determined with scanning flow cytometry. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 531, 43–61. doi: 10.3354/meps11325

McManus, M. A., Alldredge, A. L., Barnard, A. H., Boss, E., Case, J. F., Cowles, T. J., et al. (2003). Characteristics, distribution and persistence of thin layers over a 48 hour period. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 261, 1–19. doi: 10.3354/meps261001

Menden-Deuer, S. (2008). Spatial and temporal characteristics of plankton-rich layers in a shallow, temperate fjord. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 355:21. doi: 10.3354/meps07265

Mishchenko, M. I., Hovenier, J. W., and Travis, L. D. (2000). Light Scattering by Nonspherical Particles: Theory, Measurements, and Applications. San Diego, CA: Academic press. doi: 10.1016/B978-012498660-2/50029-X

Mobley, C. D. (1994). Light and Water: Radiative Transfer in Natural Waters. San Diego: Academic press.

Moore, J. K., and Villareal, T. A. (1996). Buoyancy and growth characteristics of three positively buoyant marine diatoms. Marine ecology progress series. Oldendorf 132, 203–213. doi: 10.3354/meps132203

Morel, A., and Bricaud, A. (1981). Theoretical results concerning light absorption in a discrete medium, and application to specific absorption of phytoplankton. Deep Sea Res. 28, 375–1. doi: 10.1016/0198-0149(81)90039-X

Morel, A., and Bricaud, A. (1986). “Inherent optical properties of algal cells including picoplankton: theoretical and experimental results,” in Photosynthetic Picoplankton, eds T. Platt and W. K. W. Li (Ottawa: Department of Fisheries and Oceans) 521–559.

Nardelli, S. C., and Twardowski, M. S. (2016). Assessing the link between chlorophyll concentration and absorption line height at 676 nm over a broad range of water types. Optics Exp. 24, A1374–A1389. doi: 10.1364/OE.24.0A1374

Nayak, A. R., McFarland, M. N., Sullivan, J. M., and Twardowski, M. S. (2018). Evidence for ubiquitous preferential particle orientation in representative oceanic shear flows. Limnol. Oceanogr. 63, 122–143. doi: 10.1002/lno.10618

Niinemets, l. (2010). A review of light interception in plant stands from leaf to canopy in different plant functional types and in species with varying shade tolerance. Ecol. Res. 25, 693–714. doi: 10.1007/s11284-010-0712-4

Osborne, B. A., and Geider, R. J. (1989). Problems in the assessment of the package effect in five small phytoplankters. Mar. Biol. 100, 151–159. doi: 10.1007/BF00391954

Quan, X., and Fry, E. S. (1995). Empirical equation for the index of refraction of seawater. Appl. Optics 34, 3477–3480. doi: 10.1364/AO.34.003477

Richardson, T. L., Ciotti, U. M., Cullen, J. J., and Villareal, T. A. (1996). Physiological and optical properties of Rhizosolenia formosa (bacillariophyceae) in the context of open-ocean vertical migration. J. Phycol. 32, 741–757. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-3646.1996.00741.x

Rines, J., McFarland, M., Donaghay, P., and Sullivan, J. (2010). Thin layers and species-specific characterization of the phytoplankton community in Monterey Bay, California, USA. Continent. Shelf Res. 30, 66–80. doi: 10.1016/j.csr.2009.11.001

Rines, J. E. B., Donaghay, P. L., Dekshenieks, M. M., Sullivan, J. M., and Twardowski, M. S. (2002). Thin layers and camouflage: hidden Pseudo-nitzschia spp. (Bacillariophyceae) populations in a fjord in the San Juan Islands, Washington, USA. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 225, 123–137. doi: 10.3354/meps225123

Roesler, C. S., and Barnard, A. H. (2013). Optical proxy for phytoplankton biomass in the absence of photophysiology: rethinking the absorption line height. Methods Oceanogr. 7, 79–94. doi: 10.1016/j.mio.2013.12.003

Round, F. E., Crawford, R. M., and Mann, D. G. (1990). Diatoms: Biology and Morphology of the Genera. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Shampine, L. F. (2008). Vectorized adaptive quadrature in MATLAB. J. Comput. Appl. Math. 211, 131–140. doi: 10.1016/j.cam.2006.11.021

Smetacek, V. (1999). Diatoms and the ocean carbon cycle. Protist 150, 25–32. doi: 10.1016/S1434-4610(99)70006-4

Stockley, N. D., Rottgers, R., McKee, D., Lefering, I., Sullivan, J. M., and Twardowski, M. S. (2017). Assessing uncertainties in scattering correction algorithms for reflective tube absorption measurements made with a WET Labs ac-9. Optics Exp. 25, A1139–A1153. doi: 10.1364/OE.25.0A1139

Sullivan, J. M., Donaghay, P. L., and Rines, J. E. (2010a). Coastal thin layer dynamics: Consequences to biology and optics. Continent. Shelf Res. 30, 50–65. doi: 10.1016/j.csr.2009.07.009

Sullivan, J. M., Twardowski, M. S., Donaghay, P. L., and Freeman, S. A. (2005). Use of optical scattering to discriminate particle types in coastal waters. Appl. Optics 44, 1667–1680. doi: 10.1364/AO.44.001667

Sullivan, J. M., Twardowski, M. S., Zaneveld, J., and Moore, C. C. (2013). “Measuring optical backscattering in water,” in Light Scattering Reviews 7, Springer Praxis Books, ed A. A. Kokhanovsky (Berlin; Heidelberg: Springer), 189–224. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-21907-8_6

Sullivan, J. M., Van Holliday, D., McFarland, M., McManus, M. A., Cheriton, O. M., Benoit-Bird, K. J., et al. (2010b). Layered organization in the coastal ocean: an introduction to planktonic thin layers and the LOCO project. Continent. Shelf Res. 30:1. doi: 10.1016/j.csr.2009.09.001

Talapatra, S., Hong, J., McFarland, M., Nayak, A. R., Zhang, C., Katz, J., et al. (2013). Characterization of biophysical interactions in the water column using in situ digital holography. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 473, 29–51. doi: 10.3354/meps10049

Tréguer, P., Bowler, C., Moriceau, B., Dutkiewicz, S., Gehlen, M., Aumont, O., et al. (2018). Influence of diatom diversity on the ocean biological carbon pump. Nat. Geosci. 11:27. doi: 10.1038/s41561-017-0028-x

Twardowski, M. S., Sullivan, J. M., Donaghay, P. L., and Zaneveld, J. R. V. (1999). Microscale quantification of the absorption by dissolved and particulate material in coastal waters with an ac-9. J. Atmos. Ocean. Technol. 16, 691–707. doi: 10.1175/1520-0426(1999)016<0691:MQOTAB>2.0.CO;2

Wriedt, T. (2009). Light scattering theories and computer codes. J. Quant. Spectrosc. Radiat. Transfer 110, 833–843. doi: 10.1016/j.jqsrt.2009.02.023

Yang, P., and Liou, K. N. (1995). Light scattering by hexagonal ice crystals: comparison of finite-difference time domain and geometric optics models. JOSA A 12, 162–176. doi: 10.1364/JOSAA.12.000162

Yang, P., and Liou, K. N. (1996). Geometric-optics-integral-equation method for light scattering by nonspherical ice crystals. Appl. Optics 35, 6568–6584. doi: 10.1364/AO.35.006568

Keywords: phytoplankton, orientation, diatoms, absorption, holography, optical model, thin layer, Ditylum brightwellii

Citation: McFarland M, Nayak AR, Stockley N, Twardowski M and Sullivan J (2020) Enhanced Light Absorption by Horizontally Oriented Diatom Colonies. Front. Mar. Sci. 7:494. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2020.00494

Received: 31 January 2020; Accepted: 03 May 2020;

Published: 08 July 2020.

Edited by:

Alberto Basset, University of Salento, ItalyReviewed by:

Jun Sun, Tianjin University of Science and Technology, ChinaCopyright © 2020 McFarland, Nayak, Stockley, Twardowski and Sullivan. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Malcolm McFarland, bW1jZmFybGFuZEBmYXUuZWR1

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.