- 1Division of Life Science, The Hong Kong University of Science and Technology, Hong Kong, China

- 2Department of Ocean Science, The Hong Kong University of Science and Technology, Hong Kong, China

- 3Hong Kong Branch of Southern Marine Science and Engineering Guangdong Laboratory, The Hong Kong University of Science and Technology, Hong Kong, China

In this study, we have for the first time analyzed diel microzooplankton grazing selectivity on unicellular cyanobacterial diazotroph (i.e., Crocosphaera watsonii WH8501) and non-diazotrophic unicellular microalga (i.e., Chlorella autotrophica). A mixed diet consisting of these two phytoplankton was supplied to four species of protistal grazers during daytime and nighttime, respectively. C. watsonii fixes nitrogen during nighttime and showed a stronger diel pattern of cellular C:N ratio than C. autotrophica. All four grazers ingested more nighttime C. watsonii than daytime C. watsonii, suggesting the diazotroph became more nutritious (inferred by C:N ratio) and thus a preferred prey for grazers when it fixes nitrogen. In particular, Oxyrrhis marina changed from preferring C. autotrophica during daytime to preferring C. watsonii during nighttime. The rest grazers showed species-specific grazing preferences, which could be explained by extracellular polysaccharide production of C. watsonii, feeding mode, cingulum size and cell size of grazers.

Introduction

Nitrogen (N) is essential to the growth and metabolism of life, and it often limits primary productivity in the ocean (Moore et al., 2013). N2 fixation by diazotroph is an important source for biologically available N in the euphotic zone, in which its significance equals or exceeds the flux of dissolved inorganic N from deep waters (Capone et al., 2005). In oligotrophic waters, the fixed N is especially a significant N source, contributing to approximately half of primary production (Karl et al., 1997). The fixed N can be released to the marine environment or transferred to other organisms through endogenous and exogenous processes. For example, the most studied diazotroph Trichodesmium could release its fixed N directly (Ohlendieck et al., 2000), through extracellular release (Capone et al., 1994), viral cell lysis (Ian et al., 2004), programmed cell death (Berman-Frank et al., 2004) and grazing (O’Neil et al., 1996). Unlike Trichodesmium, how the unicellular cyanobacterial diazotrophs (UCDs) transfer their fixed N to the environment and other organisms is unclear. In recent years, there was a growing concern about trophic interaction between UCDs and higher trophic levels (Wilson et al., 2017; Horii et al., 2018), with the majority of related studies focusing on mesozooplankton (0.2–20 mm) grazing on UCDs (Scavotto et al., 2015; Conroy et al., 2017).

However, it should be noted that microzooplankton (<200 μm, mainly protists) are the dominant grazers of phytoplankton in the marine environments, especially in oligotrophic waters (Calbet and Landry, 2004). Microzooplankton consume 60–75% of primary production (i.e., daily phytoplankton growth) from estuarine and coastal waters to oligotrophic open ocean (Calbet and Landry, 2004), greatly exceeding the consumption by mesozooplankton such as copepods (Gifford et al., 1995). Therefore, microzooplankton grazing plays an essential role in transferring energy and nutrients from phytoplankton to the consumers of higher trophic levels (John and Davidson, 2001; Strom et al., 2001). Hence, microzooplankton should also be major grazers of UCDs in oligotrophic waters and they might play an important role in transferring fixed N from UCDs to higher trophic levels and to other phytoplankton by releasing N to the surrounding water during grazing. However, the rate and selectivity of microzooplankton grazing on UCDs are unclear.

The grazing rate and selectivity of microzooplankton were proposed to be affected by various cellular properties of the prey (Gonzalez et al., 1990, 1993; González et al., 1990; Monger and Brown, 1999; Breckels et al., 2011). However, the nutritional quality of prey has been increasingly regarded a major factor in prey selection of protists (Verity, 1991; John and Davidson, 2001; Shannon et al., 2007; Siuda and Dam, 2010; Ng et al., 2017). Generally, herbivores have a lower C:N ratio (with a C:N ratio ranging 4–6.3; Koski, 1999; Pertola et al., 2002; Ng et al., 2017) compared to phytoplankton (with a C:N ratio ranging 6–10; Quigg et al., 2003). According to Liebig’s law of the minimum, phytoplankton N contents may determine the growth efficiency of the herbivores in terms of C (i.e., the efficiency of herbivores consuming carbon and converting it into biomass; Hessen et al., 2003). Thus, the C:N ratio of phytoplankton is considered to represent the nutritional value for grazers, with a lower C:N ratio considered as a hint of higher nutritional value (John and Davidson, 2001). Additionally, a number of studies have reported diel variation of grazing behavior of protists on marine phytoplankton (Dolan and Simek, 1999; Suzanne, 2001; Jakobsen and Strom, 2004), which could be partially explained by the diel variation in the nutritional quality of prey (Ng et al., 2017).

So far, studies on the effect of prey nutritional quality on protistan grazing have yielded inconsistent results. When protists were fed with mixtures of prey, both ciliates (Verity, 1991) and microflagellates (John and Davidson, 2001) showed higher ingestion rates on prey with low C:N ratio (i.e., high nutritional quality). Opposing results were found when protists were fed with single prey (Ng et al., 2017). These inconsistent results were obviously related to different experimental designs (i.e., single prey vs. mixed prey grazing experiments). When there is no choice of food, i.e., in single prey experiment, higher ingestion rates on low nutritional quality prey could be a result of compensatory feeding, where grazer compensates for poor nutritional quality (e.g., high C:N) by increasing food consumption to acquire sufficient nutrient (e.g., N) (Siuda and Dam, 2010). Therefore, it is inadequate to use single prey experiments for studying zooplankton feeding selectivity.

There are three distinct groups of UCDs in the ocean (UCYN-A, UCYN-Band UCYN-C). UCYN-A and UCYN-B are widespread in tropical and subtropical oceans, but UCYN-A can extend their distribution to higher latitudes (Zehr et al., 2001; Martínez-Pérez et al., 2016). Based on a recent study of the distribution of diazotrophs in North Pacific Ocean, the abundance of UCYN-B (7.0–8.4 × 109 copies m–2) was comparable to, or higher than that of UCYN-A (4.7–7.4 × 109 copies m−2) in lower latitudes (Shiozaki et al., 2017). UCYN-C is the least studied and descriptions about UCYN-C are rare. These three groups of UCDs may form blooms or dominate diazotrophic community in oligotrophic waters (Robidart et al., 2014; Bonnet et al., 2016; Wilson et al., 2017). Among the groups of the UCDs, only the UCYN-B (i.e., Crocosphaera watsonii) is cultivated. Cyanothece sp. TW3 was proposed as the only representative culture of UCYN-C (Taniuchi et al., 2012). However, the DNA similarity between nifH gene sequence of Cyanothece sp. TW3 and environmental clones of UCYN-C was only 92% (Foster et al., 2007; Cheung et al., 2017). C. watsonii exhibits a diel pattern of C:N ratio, with the cellular C:N ratio increasing during the light period and decreasing during the dark period (Dron et al., 2012). This is because C. watsonii conducts photosynthesis during daytime and N2 fixation during nighttime. Considering that prey with low C:N ratio is more nutritious and it could influence the grazing behavior of grazers (John and Davidson, 2001; Shannon et al., 2007; Ng et al., 2017), we hypothesize that C. watsonii is selectively grazed by microzooplankton when it is fixing nitrogen during nighttime. To test this hypothesis, a mixed diet consisting of C. watsonii and Chlorella autotrophica (non-diazotrophic unicellular microalgae with a similar size to C. watsonii) was used to feed four species of marine protists (Oxyrrhis marina, Euplotes sp., Scuticociliate sp. and Lepidodinium sp.) during daytime and nighttime. With this study, we aim to provide first insight to the diel pattern of microzooplankton grazing on UCD and their selectivity between diazotrophic and non-diazotrophic unicellular microalgae.

Materials and Methods

Culture Conditions of Algae and Protists

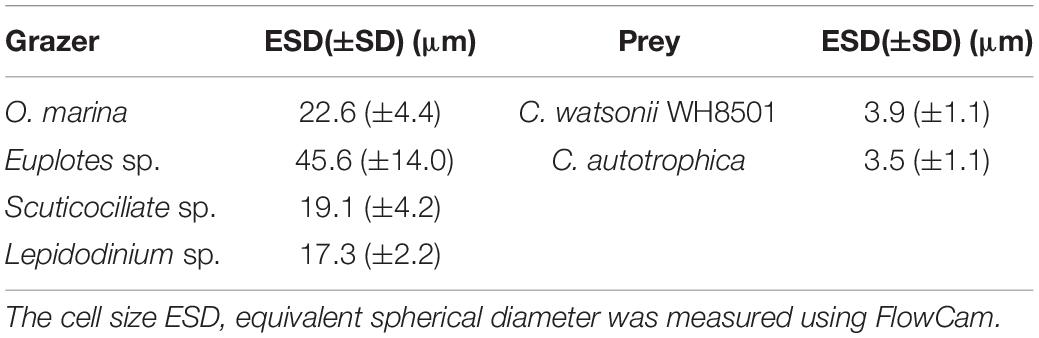

All cultures used in this study were maintained at 23.5°C with a 12:12 h light:dark cycle at the light intensities of 50 μmol photons m–2 s–1 for at least 4 weeks before the grazing experiments. The cell sizes of prey and grazers were listed in Table 1. Two batches of cultures were kept under identical culture conditions but in a reversed 12:12 h light:dark cycle. This means when one batch of cultures was at the beginning of the light period, another batch of cultures was at the beginning of the dark period.

C. watsonii WH8501 was maintained in Scripps Oceanographic medium (Tuit et al., 2004) and C. autotrophica was maintained in f/2 medium (Guillard and Ryther, 1962). Sterile dilution techniques were applied periodically to keep the prey in exponential growth phase. Starting from 2 weeks before the grazing experiments, semi-continuous cultures were diluted every 3 days. All four grazers, heterotrophic dinoflagellate O. marina, ciliates Euplotes sp. and Scuticociliate sp., and the mixotrophic dinoflagellate Lepidodinium sp. were maintained in autoclaved, filtered (0.2 μm) seawater. Lepidodinium sp. and O. marina were fed with Rhodomonas sp. daily. Scuticociliate sp. and Euplotes sp. were supplemented with rice grains to enrich natural bacteria as food. Grazers were starved for 1 day before the grazing experiments.

Measurement of Cellular Content of Carbon and Nitrogen of Prey

Cellular C and N content of C. watsonii and C. autotrophica were determined every 3 h over a 24 h period to investigate the diel variation of cellular C:N ratio.

Ten ml of C. watsonii and C. autotrophica cultures in exponential growth phase were filtered onto pre-combusted (550°C, 5 h) glass-fiber filters (Whatman GF/A) and stored at −80°C before analysis using a CHNS elemental analyzer (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Waltham, MA, United States). Three replicates of culture samples were collected and analyzed at each time point.

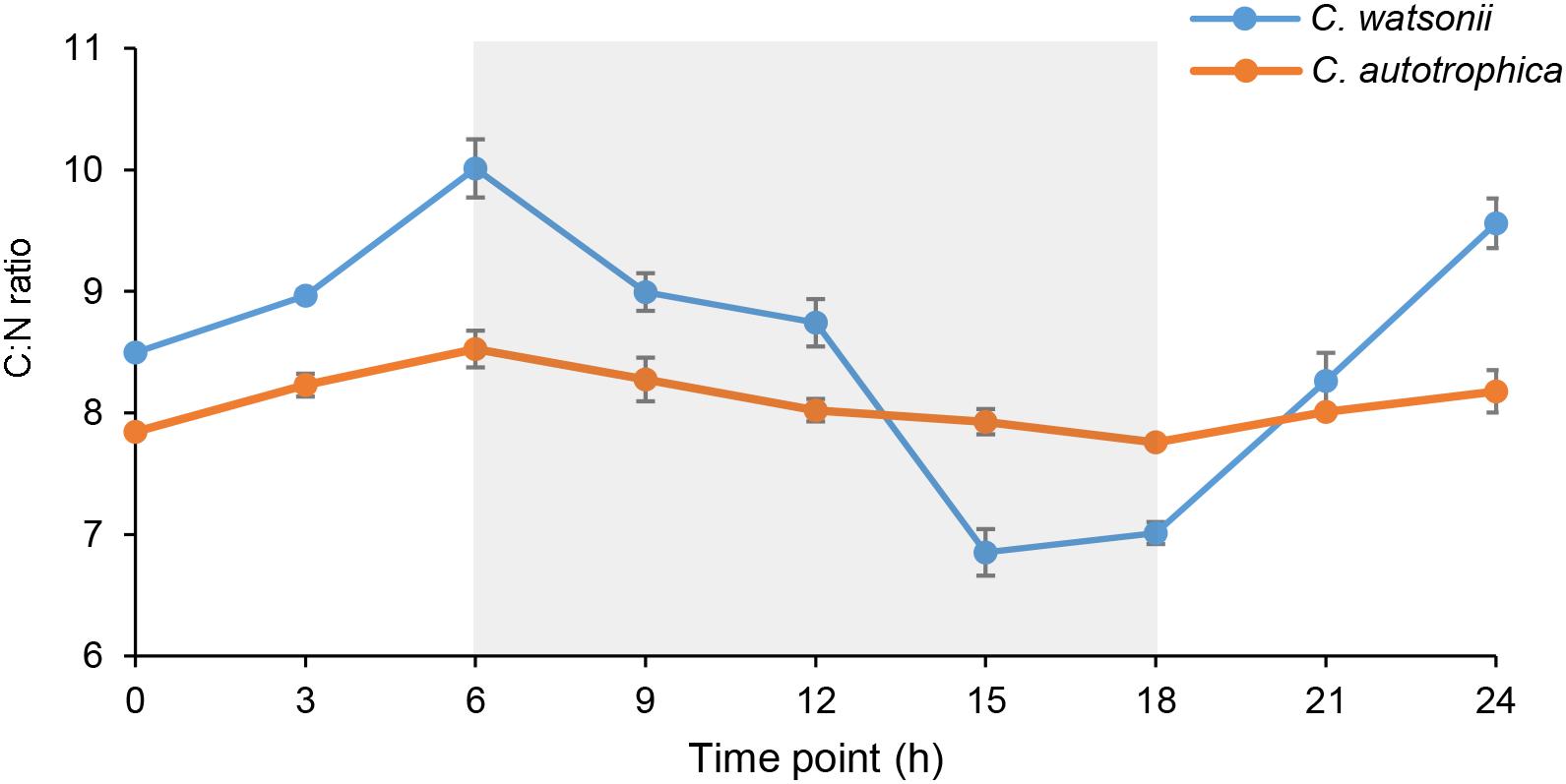

Diel Grazing Experiment on Mixed Prey

The abundance of grazers and prey was quantified with a FlowCam (FlowCam 8000, Fluid Imaging Technologies, Yarmouth, ME, United States) right before the grazing experiments. Diel grazing experiments were carried out with ∼40 ml final volume in 50 ml flasks. C. watsonii and C. autotrophica were mixed in a 1:1 ratio and the ratio of grazers to each prey was around 1:250∼1:1000. For grazing experiments with O. marina, Scuticociliate sp. or Lepidodinium sp., each grazer and the mixture of prey were added to the flasks, followed by adding Scripps Oceanographic medium to make the concentration of grazers and each prey to around 50∼170 cells ml–1 and 50000–150000 cells ml–1, respectively. For grazing experiments with Euplotes sp. as grazer, the concentration of grazer and each prey was approximately 13 and 13000 cells ml–1, respectively. Each grazer was fed with a mixed prey during daytime (4 h before the end of light period) and nighttime (4 h before the end of dark period), respectively, representing the highest and lowest prey C:N ratio at the end of the light and dark period (Figure 1). In parallel, treatments without grazers were carried out as control. The grazing experiments lasted 4 h in darkness (Fulton, 1988; John and Davidson, 2001; Chen et al., 2010; Chrzanowski and Foster, 2014) and all the treatments were carried out in triplicates. To determine the abundance of prey, 1.8 ml of samples were collected from each treatment at the beginning and end of the grazing experiments. These samples were fixed with 50 μl 20% paraformaldehyde solution (0.5% final concentration, Guo et al., 2014) and stored at −80°C until analysis using a Becton-Dickinson FACSCalibur flow cytometer. Samples for determining the concentration of grazers were fixed with formaldehyde solution (4% final concentration, Herfort et al., 2011) at the end of the experiments and analyzed with a FlowCam.

Figure 1. Diel variation of carbon to nitrogen (C:N) molar ratios in Crocosphaera watsonii and Chlorella autotrophica cells. The night-time (6th–8th h) was indicated with shaded area. The C:N ratio of C. watsonii was significantly higher than that of C. autotrophica at the end of daytime; and it was significantly lower than that of C. autotrophica at the end of nighttime (Student’s t-test, p < 0.01).

Data Analysis

Growth rate (μ, h–1) of the prey was assumed to be exponential during the grazing experiment and was calculated as

where C0 and Ct were the concentration of prey (cell ml–1) at the beginning and end of each incubation experiment, and t was the incubation time (h).

Ingestion rate (IR, cell predator–1 h–1) was calculated according to Harris, 2000,

where Cp and Cg were the concentration of prey (cell ml–1) and grazer (predator ml–1) in each incubation experiment, and μc (h–1) and μg (h–1) were the growth rate of prey in the prey-only control and grazing treatments. Cg was the concentration of grazer at the end of each grazing experiment. The significance of the difference between the ingestion rate on two prey was verified by the Student’s t-test.

The average concentration of prey (Cp) was calculated as

Prey selectivity of protists on each prey was quantified using the selectivity index α (Chesson, 1983):

where ri was the proportion of prey i in the diet, ni was the proportion of prey i in the environment.

Results

Prey Diel C:N Stoichiometry

Both C. watsonii and C. autotrophica showed a diel pattern of cellular C:N molar ratio that increased during daytime and decreased during nighttime (Figure 1). The range of the diel variation of C:N ratio was larger in C. watsonii than in C. autotrophica. The C:N ratio of C. watsonii varied from a maximum of 10.0 at the end of daytime to 6.9 during nighttime while that of C. autotrophica ranged from 8.5 to 7.8.

Diel Mixed Prey Grazing Experiment

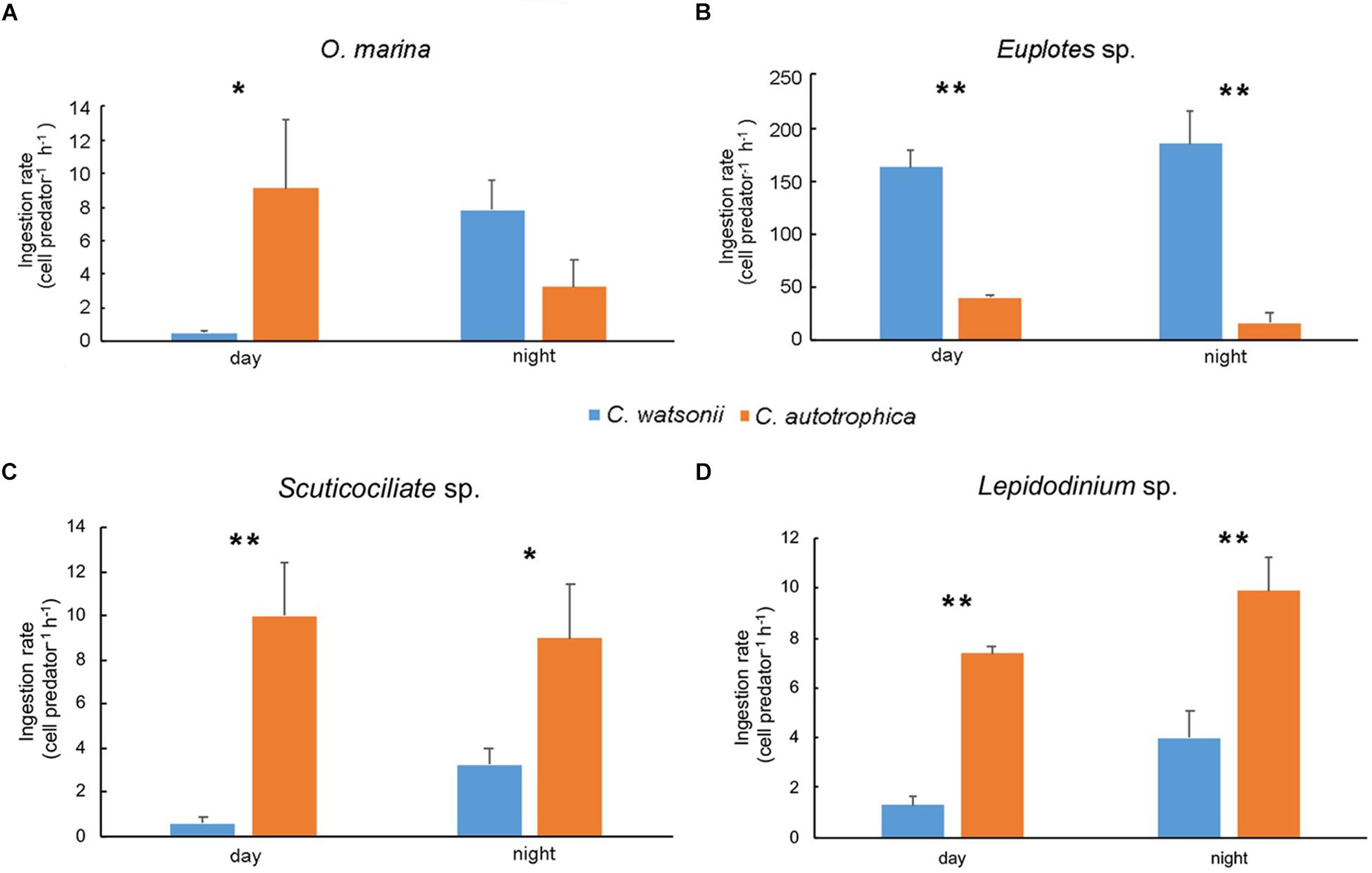

In general, all the grazers ingested more C. watsonii during nighttime than during daytime (Figure 2). In particular, O. marina ingested more C. watsonii (7.82 cell predator–1 h–1) than C. autotrophica (3.24 cell predator–1 h–1) during nighttime, while it preferred C. autotrophica (9.11 cell predator–1 h–1) over C. watsonii (0.54 cell predator–1 h–1) during daytime. The other grazers showed species-specific grazing preferences. Euplotes sp. ingested C. watsonii (163.17 cell predator–1 h–1 during daytime and 184.75 cell predator–1 h–1 during nighttime) at a significantly higher rate than C. autotrophica (41.03 cell predator–1 h–1 and 16.68 cell predator–1 h–1 during daytime and night-time, respectively). In contrast, Scuticociliate sp. ingested much less C. watsonii (0.57 cell predator–1 h–1 during daytime and 3.25 cell predator–1 h–1 during nighttime) than C. autotrophica (9.97 cell predator–1 h–1 and 8.98 cell predator–1 h–1 during daytime and nighttime, respectively). Similarly, Lepidodinium sp. grazed on C. autotrophica at a rate of 7.38 cell predator–1 h–1 during daytime and 9.89 cell predator–1 h–1 during nighttime, which was significantly higher than the ingestion of C. watsonii (1.28 cell predator–1 h–1 and 3.99 cell predator–1 h–1 during daytime and night-time, respectively). Mean prey growth rates in the control experiments, and grazing mortality rates and net growth rates in all grazing experiments was shown in Supplementary Table S1.

Figure 2. Ingestion rate of Oxyrrhis marina (A), Euplotes sp. (B), Scuticociliate sp. (C) and Lepidodinium sp. (D) during daytime and nighttime. Values denote the mean ± standard error based on triplicates. Asterisks represent significant differences between ingestion rate on two prey (Student’s t-test, *, p<0.05, **, p<0.01).

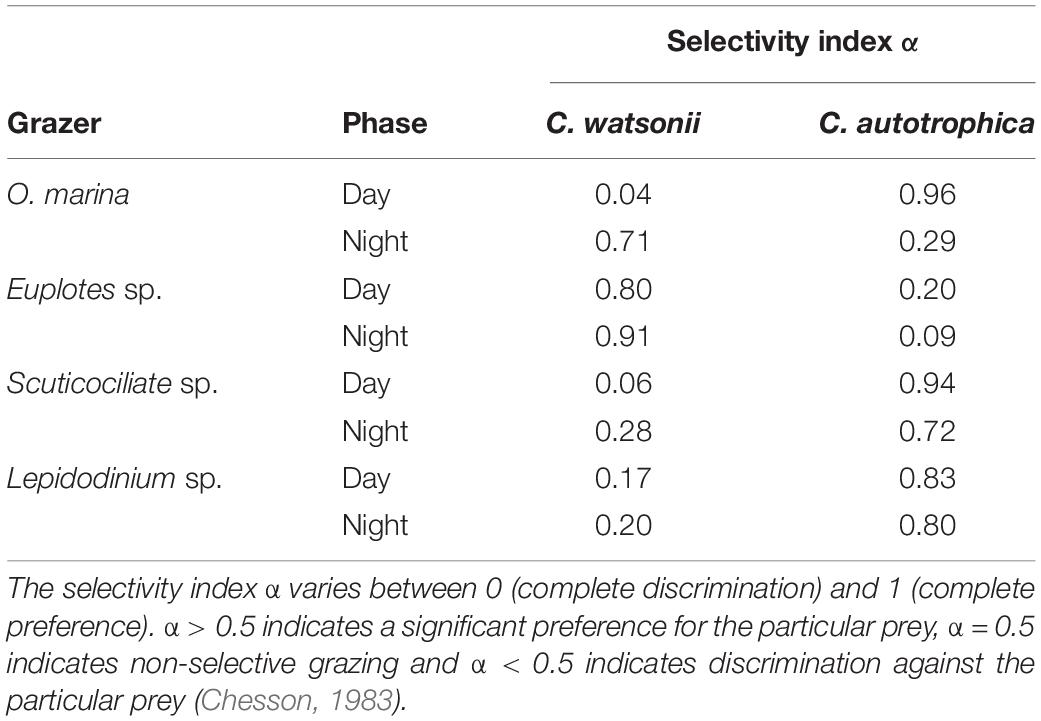

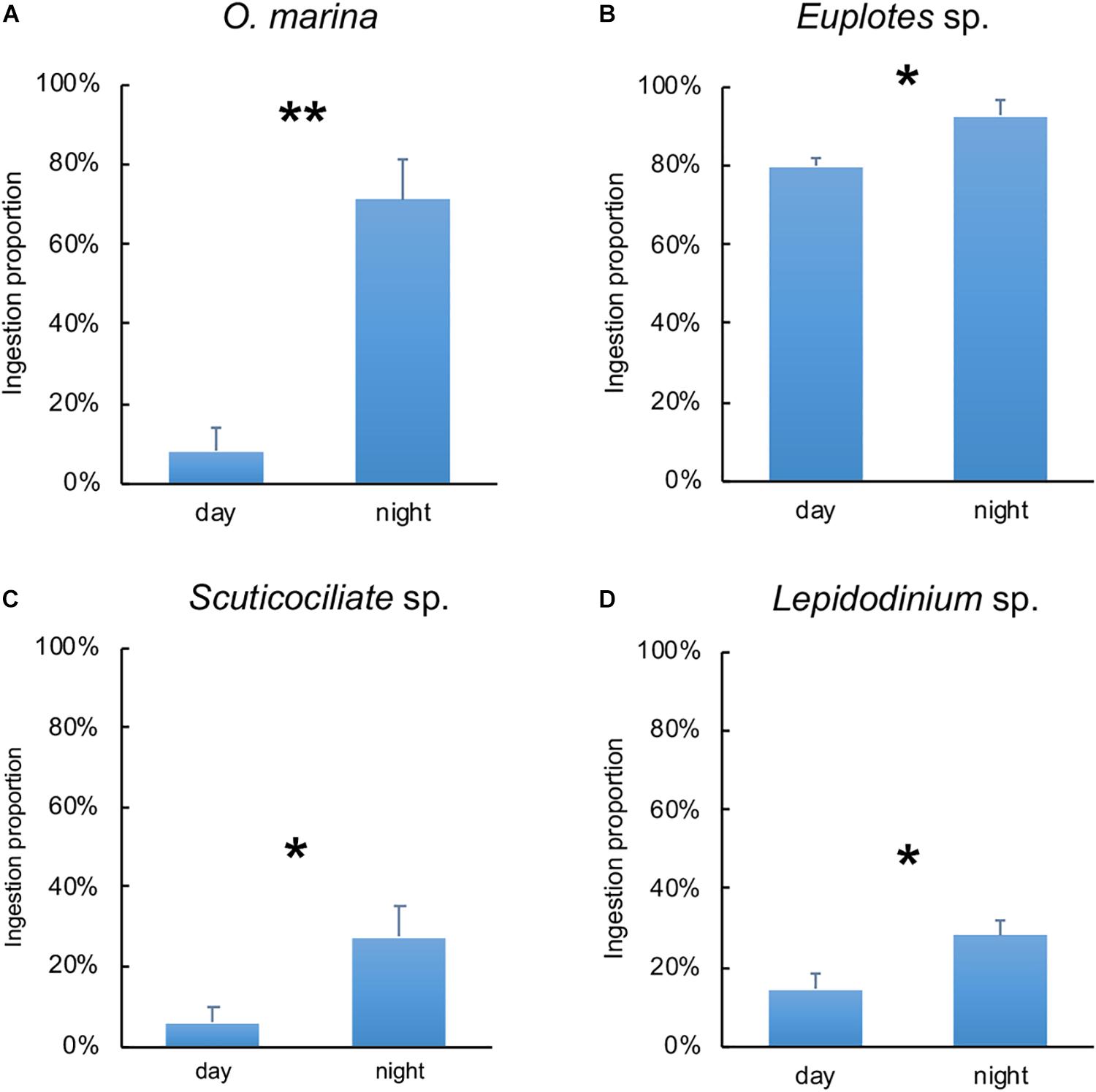

The diel pattern of ingestion proportion of O. marina, Euplotes sp., Scuticociliate sp. and Lepidodinium sp. on C. watsonii revealed that the ingestion proportion increased during nighttime (Figure 3). During nighttime, the ingestion proportion of O. marina on C. watsonii was around 71%, nearly nine times more than during daytime (8%). The ingestion proportion of Euplotes sp. on C. watsonii was 92% in the dark, higher than that in the light (80%). The ingestion proportion of Scuticociliate sp. on C. watsonii increased by more than four times from 6% to 27%. There was also a twofold increase in the ingestion proportion of Lepidodinium sp. on C. watsonii during nighttime. The selectivity index also indicated that all the grazers appeared to be more selective toward C. watsonii during nighttime (Table 2), when C. watsonii was richer in nitrogen (lower C:N ratio) than that of C. autotrophica.

Table 2. Manly–Chesson selectivity index α of grazers feeding on mixed prey C. watsonii and C. autotrophica during daytime and night-time.

Figure 3. Ingestion proportion of Oxyrrhis marina (A), Euplotes sp. (B), Scuticociliate sp. (C) and Lepidodinium sp. (D) on C. watsonii during daytime and nighttime. Values denote the mean ± standard error based on triplicates. Asterisks represent significant differences between ingestion proportion on C. watsonii during daytime and nighttime (Student’s t-test, *, p<0.05, **, p<0.01).

Discussion

Comparison of Diel C:N Ratio Patterns of C. watsonii and C. autotrophica

The diel C:N ratio pattern of C. watsonii has never been compared with that of other non-diazotrophic phytoplankton in the same study. In our result, C. watsonii and C. autotrophica exhibited a diel C:N ratio variation with similar pattern (higher C:N ratio during daytime than during night-time), while the magnitude of the diel variation was much greater in the case of C. watsonii (Figure 1). During nighttime, the C:N ratio of C. watsonii decreased and the decreasing trend suddenly accelerated after 6 h in darkness (Figure 1), which agreed with the previous findings about C and N metabolism of C. watsonii during nighttime. C. watsonii was found to enhance respiration during the late light-early dark period for creating an oxygen depleted condition (Shi et al., 2010; Dron et al., 2012), and to promote the onset of the oxygen-sensitive nitrogenase at 3–6 h after entering dark phase (Dron et al., 2012). In contrast, the non-diazotrophic C. autotrophica showed a higher C:N ratio than C. watsonii at the end of nighttime. During daytime, it was interesting that the C:N ratio of C. watsonii was higher than that of C. autotrophica, which indicated that the C fixation through photosynthesis may exceed the requirements for N assimilation. Considering N2 fixation is an energy expensive process and requires respiration of carbohydrate as energy source (Mullineaux et al., 1980; Mitsui et al., 1986), C. watsonii may enhance photosynthesis compared to non-diazotrophic phytoplankton, resulting in a higher C:N ratio during daytime.

Increased Grazing on UCDs by Microzooplankton During Night Time

Despite the fact that different grazers showed specific preferences for different prey, all showed higher selectivity for C. watsonii during nighttime (with the lowest C:N ratio) than during daytime (Figure 3). In particular, O. marina, a widely distributed free-living protist in marine ecosystems (Watts et al., 2011), closely followed the changes in C:N ratio over time with its grazing behavior. O. marina preferentially grazed on diazotrophs when they had a lower C:N ratio during nighttime and switched to prefer C. autotrophica when they had a lower C:N ratio during daytime. Therefore, our results are partially in line with the previous finding that prey C:N ratio determines the protistan grazing selectivity (Verity, 1991; John and Davidson, 2001), which suggested that the C:N ratio of prey is at least acting as a secondary controlling factor on protistan grazing selectivity. Additionally, given that mixed-prey experiments (Verity, 1991; John and Davidson, 2001) were much rarer than single-prey experiments (Shannon et al., 2007; Siuda and Dam, 2010; Ng et al., 2017), our results provide a more realistic assessment of microzooplankton grazing selectivity.

Moreover, our results suggest that microzooplankton tends to ingest more C. watsonii when the latter is fixing nitrogen during nighttime, independent of the grazer species. Although different microzooplankton show their preference on different kinds of phytoplankton prey, they seem to ingest more nutritious actively nitrogen fixing UCDs during nighttime as a supplement of bioavailable nitrogen. This could be an indication of the importance of diazotrophs as a nitrogen source to the microzooplankton in nitrogen limited oceanic waters. Furthermore, it has been reported that phytoplankton nutritional quality (C:N ratio) is important in regulating microzooplankton NH4+ -N excretion, in which the grazers excrete more NH4+ when they were fed with more nutritious prey (Lehrter et al., 1999; Davidson et al., 2005). The excretion of dissolved inorganic N from zooplankton could stimulate bacterial/phytoplankton activity in nitrogen limited ocean (Ikeda and Motoda, 1978; Carman, 1994; Legendre and Rassoulzadegan, 1995). Microzooplankton has been proposed to be the dominant grazers of phytoplankton in oligotrophic oceans where the microbial loop is the dominant component of the planktonic food web (Jackson, 1980; Calbet, 2008). In the light of our finding, the grazing pattern of protists on diazotrophs might play a role in mediating protistal nutrient excretion and hence diel variation in bacterial/phytoplankton activity in oligotrophic waters. It should be noted that another dominant UCD Candidatus Atelocyanobacterium thalassa (UCYN-A) fixes N during daytime and they were found to be able to grow in higher latitude regions than C. watsonii (Sohm et al., 2011b; Martínez-Pérez et al., 2016; Shiozaki et al., 2017; Tang et al., 2019a, b). UCYN-A is a symbiont and the sizes of the UCYN-A1 and UCYN-A2 cell consortia are 1–3 and 4–10 μm in diameter, respectively (Farnelid et al., 2016). In general, protists graze on prey that are about 1/10 of their own size (Kirchman, 2012). Therefore, protistal microzooplankton (<200 μm) might be also the important grazers of UCYN-A. Diel protistal grazing activity on different UCDs and the effects on bacterial/phytoplankton growth and metabolism in different oligotrophic ecosystems worth to be further studied.

Other Factors Possibly Influencing the Grazing Selectivity

The grazer specific preference for C. watsonii (Euplotes sp.) and C. autotrophica (Scuticociliate sp. and Lepidodinium sp.) indicated that prey selection of protists is complicated; it is not determined by a single factor of the nutritional quality of the prey, but a number of other cellular properties of the prey and the feeding mode of the grazers. Considering that the cell size of prey also plays a crucial role in determining the grazing selectivity of protists (Chrzanowski and Simek, 1990; Gonzalez et al., 1990), we have chosen C. autotrophica, which has a similar size to C. watsonii (Table 1). There was a slight diel variation of cell size, in which the cell size of both prey types slightly increased during daytime (Supplementary Figure S1). Therefore, we suggest that the diel variation in prey cell size did not contribute significantly to diel grazing selectivity on C. watsonii. Besides cell size, cell surface characteristics, like extracellular polysaccharides (EPS), have been reported to adhere to the cilia and clog the feeding apparatus of ciliates and hence inhibit their grazing (Liu and Buskey, 2000). Moreover, EPS could cause aggregation of cells through adsorption and stickiness (Lürling and Donk, 2000). It has been reported that C. watsonii could produce significant amounts of EPS (Sohm et al., 2011a). Regarding the grazers, both O. marina and Lepidodinium sp. are phagotrophic dinoflagellates, grazing on prey by raptorial feeding (Jeong et al., 2010). Although the cell sizes of the two protists are similar (Table 1), O. marina is heterotrophic with a large cingulum, whereas Lepidodinium sp. is mixotrophic with a smaller cingulum (Hansen et al., 2007; Jeong et al., 2010). Hence, O. marina may have an advantage in engulfing larger prey cells, which may facilitate its ingestion on C. watsonii bounded by the EPS and even the aggregation of C. watsonii. In addition, although both Euplotes sp. and Scuticociliate sp. are filter-feeding ciliates, the former is two times larger in cell size than the latter (Table 1). It has been reported that Euplotes sp. prefers to feed on bacterial aggregates rather than on free-living bacteria (Albright et al., 1987), which may explain why the Euplotes sp. preferred C. watsonii to C. autotrophica.

Author Contributions

LD and SC conducted the experiment and wrote the manuscript. HL designed the experiment and wrote the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by a research grants from the Research Grants Council of Hong Kong (16101917) and the Hong Kong Branch of Southern Marine Science and Engineering Guangdong Laboratory (Guangzhou) (SMSEGL20SC01).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge Dr. Jonathan Zehr for providing the culture of Crocosphaera watsonii WH8501. Our acknowledgment is also extended to Dr. Shuwen Zhang and Ms. Candy Lee for their suggestions on the experimental setup and Esther Mak for some early trial experiments.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmars.2020.00135/full#supplementary-material

References

Albright, L. J., Sherr, E. B., Sherr, B. F., and Fallon, R. D. (1987). Grazing of ciliated protozoa on free and particle-attached bacteria. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 38, 125–129. doi: 10.3354/meps038125

Berman-Frank, I., Bidle, K. D., Haramaty, L., and Falkowski, P. G. (2004). The demise of the marine cyanobacterium, Trichodesmium spp., via an autocatalyzed cell death pathway. Limnol. Oceanogr. 49, 997–1005. doi: 10.4319/lo.2004.49.4.0997

Bonnet, S., Baklouti, M., Gimenez, A., Berthelot, H., and Berman-Frank, I. (2016). Biogeochemical and biological impacts of diazotroph blooms in a low-nutrient, low-chlorophyll ecosystem: synthesis from the VAHINE mesocosm experiment (New Caledonia). Biogeosciences 13, 4461–4479. doi: 10.5194/bg-13-4461-2016

Breckels, M. N., Roberts, E. C., Archer, S. D., Malin, G., and Steinke, M. (2011). The role of dissolved infochemicals in mediating predator–prey interactions in the heterotrophic dinoflagellate Oxyrrhis marina. J. Plankton Res. 33, 629–639. doi: 10.1093/plankt/fbq114

Calbet, A. (2008). The trophic roles of microzooplankton in marine systems. ICES J. Mar. Sci. 65, 325–331. doi: 10.1093/icesjms/fsn013

Calbet, A., and Landry, M. R. (2004). Phytoplankton growth, microzooplankton grazing, and carbon cycling in marine systems. Limnol. Oceanogr. 49, 51–57. doi: 10.4319/lo.2004.49.1.0051

Capone, D. G., Burns, J. A., Montoya, J. P., Subramaniam, A., Mahaffey, C., Gunderson, T., et al. (2005). Nitrogen fixation by Trichodesmium spp.: an important source of new nitrogen to the tropical and subtropical North Atlantic Ocean. Global Biogeochem. Cycles 19:GB2024. doi: 10.1029/2004gb002331

Capone, D. G., Ferrier, M. D., and Carpenter, E. J. (1994). Amino acid cycling in colonies of the planktonic marine cyanobacterium Trichodesmium thiebautii. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 60, 3989–3995. doi: 10.1002/bit.260440917

Carman, K. R. (1994). Stimulation of marine free-living and epibiotic bacterial activity by copepod excretions. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 14, 255–261. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6941.1994.tb00111.x

Chen, B., Liu, H., and Lau, M. T. S. (2010). Grazing and growth responses of a marine oligotrichous ciliate fed with two nanoplankton: does food quality matter for micrograzers? Aquat. Ecol. 44, 113–119. doi: 10.1007/s10452-009-9264-5

Chesson, J. (1983). The estimation and analysis of preference and its relatioship to foraging models. Ecology 64, 1297–1304. doi: 10.2307/1937838

Cheung, S., Suzuki, K., Saito, H., Umezawa, Y., Xia, X., and Liu, H. (2017). Highly heterogeneous diazotroph communities in the kuroshio current and the Tokara Strait, Japan. PLoS One 12:e0186875. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0186875

Chrzanowski, T. H., and Foster, B. L. (2014). Prey element stoichiometry controls ecological fitness of the flagellate Ochromonas danica. Aquat. Microb. Ecol. 71, 257–269. doi: 10.3354/ame01680

Chrzanowski, T. H., and Simek, K. (1990). Prey-size selection by freshwater flagellated protozoa. Limnol. Oceanogr. 35, 1429–1436. doi: 10.4319/lo.1990.35.7.1429

Conroy, B. J., Steinberg, D. K., Bongkuen, S., Andrew, K., Carpenter, E. J., and Foster, R. A. (2017). Mesozooplankton graze on cyanobacteria in the Amazon River plume and western tropical north Atlantic. Front. Microbiol. 8:1436. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.01436

Davidson, K., Roberts, E. C., Wilson, A. M., and Mitchell, E. (2005). The role of prey nutritional status in governing protozoan nitrogen regeneration efficiency. Protist 156, 45–62. doi: 10.1016/j.protis.2004.10.001

Dolan, J. R., and Simek, K. (1999). Diel periodicity in Synechococcus populations and grazing by heterotrophic nanoflagellates: analysis of food vacuole contents. Limnol. Oceanogr. 44, 1565–1570. doi: 10.4319/lo.1999.44.6.1565

Dron, A., Rabouille, S., Claquin, P., Le Roy, B., Talec, A., and Sciandra, A. (2012). Light-dark (12:12) cycle of carbon and nitrogen metabolism in Crocosphaera watsonii WH8501: relation to the cell cycle. Environ. Microbiol. 14, 967–981. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2011.02675.x

Farnelid, H., Turk-Kubo, K., Muñoz-Marín, M. C., and Zehr, J. P. (2016). New insights into the ecology of the globally significant uncultured nitrogen-fixing symbiont UCYN-A. Aquat. Microb. Ecol. 77, 125–138. doi: 10.3354/ame01794

Foster, R. A., Subramaniam, A., Mahaffey, C., Carpenter, E. J., Capone, D. G., and Zehr, J. P. (2007). Influence of the Amazon River plume on distributions of free-living and symbiotic cyanobacteria in the western tropical north Atlantic Ocean. Limnol. Oceanogr. 52, 517–532. doi: 10.4319/lo.2007.52.2.0517

Fulton, R. S. (1988). Grazing on filamentous algae by herbivorous zooplankton. Freshw. Biol. 20, 263–271. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2427.1988.tb00450.x

Gifford, D. J., Fessenden, L. M., Garrahan, P. R., and Martin, E. (1995). Grazing by microzooplankton and mesozooplankton in the high-latitude North Atlantic Ocean: spring versus summer dynamics. J. Geophys. Res. 100, 6665–6675. doi: 10.1029/94jc00983

González, J. M., Iriberri, J., Egea, L., and Barcina, I. (1990). Differential rates of digestion of bacteria by freshwater and marine phagotrophic protozoa. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 56, 1851–1857. doi: 10.1002/bit.260360114

Gonzalez, J. M., Sherr, E. B., and Sherr, B. F. (1990). Size-selective grazing on bacteria by natural assemblages of estuarine flagellates and ciliates. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 56, 583–589. doi: 10.1002/bit.260350513

Gonzalez, J. M., Sherr, E. B., and Sherr, B. F. (1993). Differential feeding by marine flagellates on growing versus starving, and on motile versus nonmotile, bacterial prey. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 102, 257–267. doi: 10.3354/meps102257

Guillard, R. R. L., and Ryther, J. H. (1962). Studies of marine planktonic diatoms: i. cyclotella nana hustedt, and detonula confervacea (cleve) gran. Can. Can. J. Microbiol. 8, 229–239. doi: 10.1139/m62-029

Guo, C., Liu, H., Yu, J., Zhang, S., and Wu, C. J. (2014). Role of microzooplankton grazing in regulating phytoplankton biomass and community structure in response to atmospheric aerosol input. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 507, 69–79. doi: 10.3354/meps10809

Hansen, G., Botes, L., and De Salas, M. (2007). Ultrastructure and large subunit rDNA sequences of Lepidodinium viride reveal a close relationship to Lepidodinium chlorophorum comb. nov. (=Gymnodinium chlorophorum). Psychol. Res. 55, 25–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1835.2006.00442.x

Herfort, L., Peterson, T., McCue, L. A., and Zuber, P. (2011). Protist 18S rRNA gene sequence analysis reveals multiple sources of organic matter contributing to turbidity maxima of the Columbia River estuary. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 438, 19–31. doi: 10.3354/meps09303

Hessen, D. O., Andersen, T., Brettum, P., and Faafeng, B. A. (2003). Phytoplankton contribution to sestonic mass and elemental ratios in lakes: implications for zooplankton nutrition. Limnol. Oceanogr. 3, 1289–1296. doi: 10.4319/lo.2003.48.3.1289

Horii, S., Takahashi, K., Shiozaki, T., Hashihama, F., and Furuya, K. (2018). Stable isotopic evidence for the differential contribution of diazotrophs to the epipelagic grazing food chain in the mid-Pacific Ocean. Global. Ecol. Biogeogr. 27, 1467–1480. doi: 10.1111/geb.12823

Ian, H., Sarah, R. G., Douglas, G. C., Edward, J. C., and Jed, A. F. (2004). Evidence of Trichodesmium viral lysis and potential significance for biogeochemical cycling in the oligotrophic ocean. Aquat. Microb. Ecol. 36, 1–8. doi: 10.3354/ame036001

Ikeda, T., and Motoda, S. (1978). Estimated zooplankton production and their ammonia excretion in Kuroshio and adjacent seas. Fish. Bull. 76, 357–367.

Jackson, G. A. (1980). Phytoplankton growth and zooplankton grazing in oligotrophic oceans. Nature 284, 439–441. doi: 10.1038/284439a0

Jakobsen, H. H., and Strom, S. L. (2004). Circadian cycles in growth and feeding rates of heterotrophic protist plankton. Limnol. Oceanogr. 49, 1915–1922. doi: 10.4319/lo.2004.49.6.1915

Jeong, H. J., Yoo, Y. D., Kim, J. S., Seong, K. A., Kang, N. S., and Kim, T. H. (2010). Growth, feeding and ecological roles of the mixotrophic and heterotrophic dinoflagellates in marine planktonic food webs. Ocean Sci. J. 45, 65–91. doi: 10.1007/s12601-010-0007-2

John, E. H., and Davidson, K. (2001). Prey selectivity and the influence of prey carbon:nitrogen ratio on microflagellate grazing. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 260, 93–111. doi: 10.1016/s0022-0981(01)00244-1

Karl, D., Letelier, R., Tupas, L., Dore, J., Christian, J., and Hebel, D. (1997). The role of nitrogen fixation in biogeochemical cycling in the subtropical North Pacific Ocean. Nature 388, 533–538. doi: 10.1038/41474

Kirchman, D. L. (2012). Predation and Protists. Processes in Microbial Ecology. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 117–136. doi: 10.1093/oso/9780198789406.001.0001

Koski, M. (1999). Carbon:nitrogen ratios of Baltic Sea copepods–indication of mineral limitation? J. Plankton Res. 21, 1565–1573. doi: 10.1093/plankt/21.8.1565

Legendre, L., and Rassoulzadegan, F. (1995). Plankton and nutrient dynamics in marine waters. Ophelia 41, 153–172. doi: 10.1080/00785236.1995.10422042

Lehrter, J. C., Pennock, J. R., and McManus, G. B. (1999). Microzooplankton grazing and nitrogen excretion across a surface estuarine-coastal interface. Estuaries 22, 113–125. doi: 10.2307/1352932

Liu, H., and Buskey, E. J. (2000). The exopolymer secretions (EPS) layer surrounding Aureoumbra lagunensis cells affects growth, grazing, and behavior of protozoa. Limnol. Oceanogr. 45, 1187–1191. doi: 10.4319/lo.2000.45.5.1187

Lürling, M., and Donk, E. V. (2000). Grazer-induced colony formation in Scenedesmus: are there costs to being colonial? Oikos 88, 111–118. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0706.2000.880113.x

Martínez-Pérez, C., Mohr, W., Löscher, C., Dekaezemacker, H., Littmann, S., Yilmaz, P., et al. (2016). The small unicellular diazotrophic symbiont, UCYN-A, is a key player in the marine nitrogen cycle. Nat. Microbiol. 1:16163. doi: 10.1038/nmicrobiol.2016.163

Mitsui, A., Kumazawa, S., Takahashi, A., Ikemoto, H., Cao, S., and Arai, T. (1986). Strategy by which nitrogen-fixing unicellular cyanobacteria grow photoautotrophically. Nature 323, 720–722. doi: 10.1038/323720a0

Monger, B. C., and Brown, L. S. L. (1999). Feeding selection of heterotrophic marine nanoflagellates based on the surface hydrophobicity of their picoplankton prey. Limnol. Oceanogr. 44, 1917–1927. doi: 10.4319/lo.1999.44.8.1917

Moore, C. M., Mills, M. M., Arrigo, K. R., Berman-Frank, I., Bopp, L., Boyd, P. W., et al. (2013). Processes and patterns of oceanic nutrient limitation. Nat. Geosci. 6, 701–710. doi: 10.1038/ngeo1765

Mullineaux, P. M., Chaplin, A. E., and Gallon, J. R. (1980). Effects of a light to dark transition on carbon reserves, nitrogen fixation and ATP concentrations in cultures of Gloeocapsa (Gloeothece) sp. 1430/3. J. Gen. Microbiol. 120, 227–232. doi: 10.1099/00221287-120-1-227

Ng, W. H. A., Liu, H., and Zhang, S. (2017). Diel variation of grazing of the dinoflagellate Lepidodinium sp. and ciliate Euplotes sp. on algal prey: the effect of prey cell properties. J. Plankton Res. 39, 450–462. doi: 10.1093/plankt/fbx020

Ohlendieck, U., Stuhr, A., and Siegmund, H. (2000). Nitrogen fixation by diazotrophic cyanobacteria in the Baltic Sea and transfer of the newly fixed nitrogen to picoplankton organisms. J. Mar. Syst. 25, 213–219. doi: 10.1016/s0924-7963(00)00016-6

O’Neil, J. M., Metzler, P. M., and Glibert, P. M. (1996). Ingestion of 15N2-labelled Trichodesmium spp. and ammonium regeneration by the harpacticoid copepod Macrosetella gracilis. Mar. Biol. 125, 89–96. doi: 10.1007/bf00350763

Pertola, S., Koski, M., and Viitasalo, M. (2002). Stoichiometry of mesozooplankton in N- and P-limited areas of the Baltic Sea. Mar. Biol. 140, 425–434. doi: 10.1007/s00227-001-0723-3

Quigg, A., Finkel, Z., Irwin, A., Rosenthal, Y., Ho, T., Reinfelder, J. R., et al. (2003). The evolutionary inheritance of elemental stoichiometry in marine phytoplankton. Nature 425, 291–294. doi: 10.1038/nature01953

Robidart, J. C., Church, M. J., Ryan, J. P., Ascani, F., Wilson, S. T., Bombar, D., et al. (2014). Ecogenomic sensor reveals controls on N2-fixing microorganisms in the North Pacific Ocean. ISME J. 8, 1175–1185. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2013.244

Scavotto, R. E., Dziallas, C., Bentzon-Tilia, M., Riemann, L., and Moisander, P. H. (2015). Nitrogen-fixing bacteria associated with copepods in coastal waters of the North Atlantic Ocean. Environ. Microbiol. 17, 3754–3765. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.12777

Shannon, S. P., Chrzanowski, T. H., and Grover, J. P. (2007). Prey food quality affects flagellate ingestion rates. Microb. Ecol. 53, 66–73. doi: 10.1007/s00248-006-9140-y

Shi, T., Ilikchyan, I., Rabouille, S., and Zehr, J. P. (2010). Genome-wide analysis of diel gene expression in the unicellular N2-fixing cyanobacterium Crocosphaera watsonii WH 8501. ISME J. 4, 621–632. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2009.148

Shiozaki, T., Bombar, D., Riemann, L., Hashihama, F., Takeda, S., Yamaguchi, T., et al. (2017). Basin scale variability of active diazotrophs and nitrogen fixation in the North Pacific, from the tropics to the subarctic Bering Sea. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 31, 996–1009. doi: 10.1002/2017GB005681

Siuda, A. N. S., and Dam, H. G. (2010). Effects of omnivory and predator-prey elemental stoichiometry on planktonic trophic interactions. Limnol. Oceanogr. 55, 2107–2116. doi: 10.4319/lo.2010.55.5.2107

Sohm, J. A., Edwards, B. R., Wilson, B. G., and Webb, E. A. (2011a). Constitutive extracellular polysaccharide (EPS) production by specific isolates of Crocosphaera watsonii. Front. Microbiol. 2:229. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2011.00229

Sohm, J. A., Webb, E. A., and Capone, D. G. (2011b). Emerging patterns of marine nitrogen fixation. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 9, 499–508. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2594

Strom, S. L., Brainard, M. A., Holmes, J. L., and Olson, M. B. (2001). Phytoplankton blooms are strongly impacted by microzooplankton grazing in coastal North Pacific waters. Mar. Biol. 138, 355–368. doi: 10.1007/s002270000461

Suzanne, L. S. (2001). Light-aided digestion, grazing and growth in herbivorous protists. Aquat. Microb. Ecol. 23, 253–261. doi: 10.3354/ame023253

Tang, W., Li, Z., and Cassar, N. (2019a). Machine learning estimates of global oceanic nitrogen fixation. J. Geophys. Res. Biogeosci. 124, 717–730. doi: 10.1029/2018JG004828

Tang, W., Wang, S., Fonseca-Batista, D., Dehairs, F., Gifford, S., Gonzalez, A. G., et al. (2019b). Revisiting the distribution of oceanic N2 fixation and estimating diazotrophic contribution to marine production. Nat. Commun. 10:831. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-08640-0

Taniuchi, Y., Chen, Y. L., Chen, H., Tsai, M., and Ohki, K. (2012). Isolation and characterization of the unicellular diazotrophic cyanobacterium Group C TW3 from the tropical western Pacific Ocean. Environ. Microbio. 14, 641–654. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2011.02606.x

Tuit, C., Waterbury, J., and Ravizza, G. (2004). Diel variation of molybdenum and iron in marine diazotrophic cyanobacteria. Limnol. Oceanogr. 49, 978–990. doi: 10.4319/lo.2004.49.4.0978

Verity, P. G. (1991). Measurement and simulation of prey uptake by marine planktonic ciliates fed plastidic and aplastidic nanoplankton. Limnol. Oceanogr. 36, 729–750. doi: 10.4319/lo.1991.36.4.0729

Watts, P. C., Martin, L. E., Kimmance, S. A., Montagnes, D. J. S., and Lowe, C. D. (2011). The distribution of Oxyrrhis marina: a global disperser or poorly characterized endemic? J. Plankton Res. 33, 579–589. doi: 10.1093/plankt/fbq148

Wilson, S. T., Aylward, F. O., Ribalet, F., Barone, B., Casey, J. R., Connell, P. E., et al. (2017). Coordinated regulation of growth, activity and transcription in natural populations of the unicellular nitrogen-fixing cyanobacterium Crocosphaera. Nat. Microbiol. 2:17118. doi: 10.1038/nmicrobiol.2017.118

Keywords: C:N ratio, Crocosphaera, Chlorella, protist, grazing selectivity

Citation: Deng L, Cheung S and Liu H (2020) Protistal Grazers Increase Grazing on Unicellular Cyanobacteria Diazotroph at Night. Front. Mar. Sci. 7:135. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2020.00135

Received: 15 October 2019; Accepted: 19 February 2020;

Published: 10 March 2020.

Edited by:

Lasse Riemann, University of Copenhagen, DenmarkReviewed by:

Carolin Regina Löscher, University of Southern Denmark, DenmarkQian Li, University of Hawai‘i, United States

Copyright © 2020 Deng, Cheung and Liu. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Hongbin Liu, bGl1aGJAdXN0Lmhr

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Lixia Deng

Lixia Deng Shunyan Cheung

Shunyan Cheung Hongbin Liu

Hongbin Liu