- 1Ocean and Earth Science, University of Southampton, National Oceanography Centre Southampton, Southampton, United Kingdom

- 2National Oceanography Centre, Southampton, United Kingdom

- 3Ocean and Ecosystem Science Division, Department of Fisheries and Oceans Canada, Bedford Institute of Oceanography, Dartmouth, NS, Canada

- 4Trondheim Biological Station, Department of Biology, Centre of Autonomous Marine Operations and Systems, Norwegian University of Science and Technology, Trondheim, Norway

- 5Section of Arctic Biology, University Centre in Svalbard, Longyearbyen, Norway

Diatoms are a keystone algal group, with diverse cell morphology and a global distribution. The biogeography of morphological, functional, and life-history traits of marine diatoms were investigated in Arctic and Atlantic waters of the Labrador Sea during the spring bloom (2013-2014). In this study, trait-based analysis using community-weighted means showed that low temperatures (< 0°C) in Arctic waters correlated positively with diatom species that have traits such as low temperature optimum growth and the ability to produced ice-binding proteins, highlighting their sea ice origin. High silicate concentrations in Arctic waters, as well as sea ice cover and shallow bathymetry, favoured diatom species that were heavily silicified, colonial and capable of producing resting spores, suggesting that these are important traits for this community. In Atlantic waters, diatom species with large surface area to volume ratios were dominant in deep mixed layers, whilst low silicate to nitrate ratios correlated positively with weakly silicified species. Sharp cell projections, such as processes or spines, were positively correlated with water-column stratification, indicating that these traits promote positive buoyancy for diatom cells. Our trait-based analysis directly links cell morphology and physiology with diatom species distribution, allowing new insights on how this method can potentially be applied to explain ecophysiology and shifting biogeographical distributions in a warming climate.

Introduction

Diatoms are one of the most ubiquitous and functionally diverse unicellular eukaryotic groups on the planet, contributing to around 20% of global primary productivity and 40% of oceanic primary production (Malviya et al., 2016). Across the global oceans, marine diatom abundance, species composition, and genus diversity exhibit biogeographical patterns in their spatial distributions (Rytter Hasle, 1976; Malviya et al., 2016; Tréguer et al., 2018). In marine waters, pelagic diatom speciation and biogeography is an evolutionary response to environmental selection rather than dispersal, as opposed to freshwater ecosystems (Cermeno and Falkowski, 2009; Cermeño et al., 2010). Along with the biogeography of diatom species, environmental heterogeneity shapes diatom functional traits and diversity over temporal and spatial scales (Key et al., 2010).

Although it is comparatively simple to study the distribution of phytoplankton species using environmental niche modelling (Brun et al., 2015; Barton et al., 2016), it is more difficult to understand the mechanisms involved in structuring the community as a whole (McGill et al., 2006). Many efforts have been made to map phytoplankton distributions based on their functional biogeochemical role using modelling approaches (phytoplankton functional types, PFTs) (Le Quere et al., 2005; Follows et al., 2007). However, only a few species are used to represent phytoplankton groups, which can lead to an oversimplification of their functions (Irwin and Finkel, 2017). One way to refine functional variability is by using trait-based approaches, which define species in terms of their ecological roles that capture key aspects of organismal functionality in the system (Litchman et al., 2007; Litchman and Klausmeier, 2008; Glibert, 2016). Trait-based research has become a novel approach to interpret the data and elucidate the patterns of species distributions (Violle et al., 2007). Thus, instead of using simple taxonomic ecology to explain species distribution, biogeography, seasonality and/or long-term trends, functional traits analysis has the potential to give a realistic prediction of a biological community's response to changes in the environment (McGill et al., 2006).

Trait-based analyses have been used extensively in terrestrial ecology (Cornelissen et al., 2003; Westoby and Wright, 2006; Lavorel et al., 2011). However, they have only recently been applied to freshwaters systems (Weithoff, 2003; Kruk et al., 2010; Schwaderer et al., 2011; Edwards et al., 2013b; Jamil et al., 2014; Zwart et al., 2015) and, far less frequently, to marine ecosystems (Barton et al., 2013a,b; Edwards et al., 2013a), to understand the distributional patterns and re-organisation of phytoplankton communities under climate change scenarios. Examples of functional traits associated with diatom species and morphotypes, which link to their seasonal and/or spatial occurrence, include: cell size (Alves-de-Souza et al., 2008), shape (Pahlow et al., 1997; Leonilde et al., 2017), morphological characteristics (Ligowski et al., 2012; Assmy et al., 2013b; Allen, 2014), chain formation (Pahlow et al., 1997), colony shape (Passy, 2002), attachment mechanisms to a hard substrate (Algarte et al., 2016), nutritional strategies (Edwards et al., 2015), and the level of cell wall silicification, some of which may confer resistance to grazing (Assmy et al., 2013b) or contribute to carbon export (Tréguer et al., 2018).

Trait-based analyses can be extremely insightful when applied to strong spatial and/or temporal environmental gradients, as well as habitats which are under severe climatic pressure. The Labrador Sea sector of the North Atlantic Ocean is an ideal location to apply trait-based approaches to marine diatom species biogeography due to the intense diatom-dominated spring blooms that occur in contrasting hydrographical zones that sub-divide the region into distinct ecological provinces (Fragoso, 2016; Fragoso et al., 2016, 2017). The surface layer of the Labrador Sea comprises blended waters of distinct origin: warmer and more saline (herein defined as Atlantic-influenced for simplicity) waters covering the central deep basin, and cooler and fresher waters (herein denoted as Arctic-influenced) covering the surrounding shelves and shelf margins, but often extending offshore (Head et al., 2013). While an ice-related (i.e., species that grow in ice-melt waters) and polar diatom community develops on the Labrador Shelf (along the Canadian margin of the Labrador Sea) as sea ice melts during spring, Arctic pelagic and neritic diatom species occur near the Greenland coast and subpolar oceanic species are common in North Atlantic waters of the central basin in late spring and early summer (Fragoso et al., 2016).

The Labrador Sea is also a region that is susceptible to climate change (Dickson et al., 2002; Yashayaev and Loder, 2016, 2017). Accelerated sea ice melt has intensified freshening inflow episodes in the Labrador Sea (Yashayaev et al., 2015), which may affect deep mixing and impact spring diatom bloom phenology and community composition (Zhai et al., 2013). The intrusion of the Pacific diatom Neodenticula seminae into North Atlantic waters, including the Labrador Sea, via the Northwest Passage is thought to be a consequence of intense Arctic sea ice melt during recent summers (Reid et al., 2007). Sea surface temperature has also increased during the last few decades in North Atlantic waters, including the Labrador Sea (Yashayaev et al., 2015), and warmer temperatures have promoted further biogeographical shifts that favour warmer-water plankton species in the North Atlantic (Beaugrand et al., 2002). Projections into the future show displacement of phytoplankton niches and diatom species, due to changes in oceanic circulation in the North Atlantic (Barton et al., 2016). Increasing our understanding of the biogeography of diatom functional traits in Arctic and Atlantic waters will further elucidate the re-organisation of phytoplankton communities as oceans continue to warm.

Here, a trait-based analysis was applied to understand the mechanisms driving diatom species' distributions during spring in the Labrador Sea. The trait analysis was based on gathering ecological information on the main diatom species from distinct bioregions of the Labrador Sea based on the literature. Quantitative and qualitative traits, with the latter converted to numerical variables, were analysed together to calculate the mean trait values of different diatom communities. This trait-based analysis allowed an ecological explanation of why certain diatom species thrive in Arctic or Atlantic waters, further contributing to the plankton biogeography typically observed in the Labrador Sea (Sathyendranath et al., 1995, 2009; Li and Harrison, 2001; Head et al., 2003; Platt et al., 2005; Fragoso et al., 2016, 2017).

Methods

Sampling and Analysis

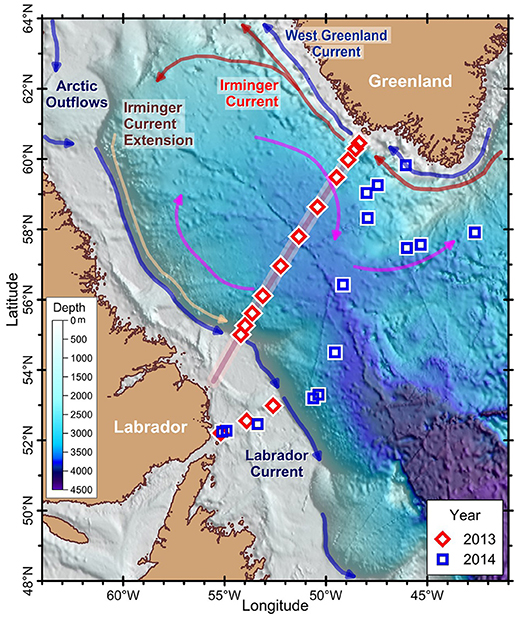

Data for this study were collected on two research cruises (HUD-2013-008, and JR302) to the Labrador Sea during May (2013) and June (2014), where stations were sampled on the AR7W repeat hydrography line (2013), or just south of this transect (2014), running across the Labrador Sea from Misery Point on the Labrador coast northeast to Cape Desolation on the west Greenland coast (Figure 1). Vertical profiles of temperature, salinity and chlorophyll fluorescence were measured with a CTD/rosette system (Sea-Bird, SBE 911). Water samples were collected on the upward casts using 10 L Niskin bottles mounted on a rosette frame. Mixed layer depths were defined as the depth where density (σθ) changes by 0.03 kg m−3 from a stable surface value (~10 m) (Weller and Plueddemann, 1996). Stratification index (SI) was calculated as the difference in σθ values between 60 and 10 m divided by the respective difference in depth (50 m) (Fragoso et al., 2017).

Figure 1. Map showing the stations and a simplified scheme of currents of the Labrador Sea. Stations were sampled along (2013, red diamond) or south of the AR7W transect (background red line) (2014, blue square). Scale refers to bathymetry. Circulation elements of the Labrador Sea: cold currents of Arctic origin (Labrador and West Greenland Currents, blue arrows), warm currents of Atlantic origin [Irminger Current (red arrows) and Extension (brown arrows)] and the anticyclonic circulation gyre (pink arrows).

Water samples were collected from a depth (surface or near surface) from within the surface mixed layer for diatom identification, and nutrient and chlorophyll a (chl a) analyses. Diatom identification and enumeration occurred primarily using a Leitz inverted light microscope (LM), where water samples (0.3 L) were preserved in acidic Lugol's solution at a final concentration of 2%. Most diatoms (>70% of total diatom biomass) were identified to species' level, and in a few cases, only to genus level (e.g., Pseudo-nitzschia spp.). For taxa that could not be identified to species level using the LM (e.g., Thalassiosira spp., Fragilariopsis spp. and small diatoms), further identification and counting occurred using a Leo 1450VP scanning electron microscope (SEM). For SEM analysis, water samples were filtered (0.25–0.5 L) onto polycarbonate filters (0.8 μm pore size, Whatman), rinsed with trace ammonium solution (pH 10) to remove salt water, oven-dried (60°C, 10 h) and stored in Millipore PetriSlides. A subsection of the polycarbonate filters were then fixed onto aluminium stubs and sputter-coated using Hummer VI-A gold coater (Daniels et al., 2012). Cells were counted under a magnification of x3000 across numerous fields of view (Daniels et al., 2012). Nutrient concentrations and chl a analysis, biomass estimations, as well as the literature information used to identify individual phytoplankton species are fully described in Fragoso et al. (2016).

For simplicity, stations of the Labrador Sea were categorised as being influenced mainly by waters of Arctic or Atlantic origin. This partitioning was based on the vertical profiles of temperature, salinity, and density. Stations herein arbitrarily called “Arctic-influenced” included surface layers (< 50 m) that had a combination of waters of Arctic origin, including the Labrador Current (east of Labrador, Canada) and West Greenland Current (southwest of Greenland) (for details, see Yashayaev, 2007; Fragoso et al., 2016). Additionally, this category can include a contribution of waters of coastal and estuarine origin (Straneo and Saucier, 2008), sea ice, iceberg, and glacier melt (Yankovsky and Yashayaev, 2014). Because of the large freshwater input, the top layer (the upper 50 m) composition of this water type can be easily recognised based on the stratification observed (this study, Fragoso et al., 2016, 2017). A second category of stations, named arbitrarily in this study as “Atlantic-influenced,” has been reported to contain a larger component of Atlantic Water (compared to the Arctic-influenced stations) commonly derived from the Irminger Current and other variations of North Atlantic Current, although it also undergoes mixing and transformation when it reaches the Labrador Sea (Yashayaev, 2007). Although samples in this study were collected from the surface (<10 m), the vertical density profile between these water types were investigated to check the degree of differentiation driven by stratification, transformation and mixing processes within upper 200 m, typically observed in the Labrador Sea (Fragoso et al., 2016, 2017).

Trait-Based Analysis

An extensive literature search of diatom species ecological strategies, life history and morphological traits of diatoms from the Labrador Sea was conducted to identify which functional traits determine species biogeography (see Supplementary Data). In this study, traits were selected based on their ecological role and the availability of information, which could support meaningful insights of species' responses to the environment and diatom species biogeography. As it was difficult to find information about every potential trait for every diatom species occurring in this study, some species were grouped based on trait similarities (i.e., cell morphology; e.g., Rhizosolenia hebetata f. semispina and Proboscia alata are both large, elongated, highly silicified species, with apical cell processes) and trait values were chosen based on the species with the highest biomass in each sample (e.g., Rhizosolenia f. semispina rather than P. alata).

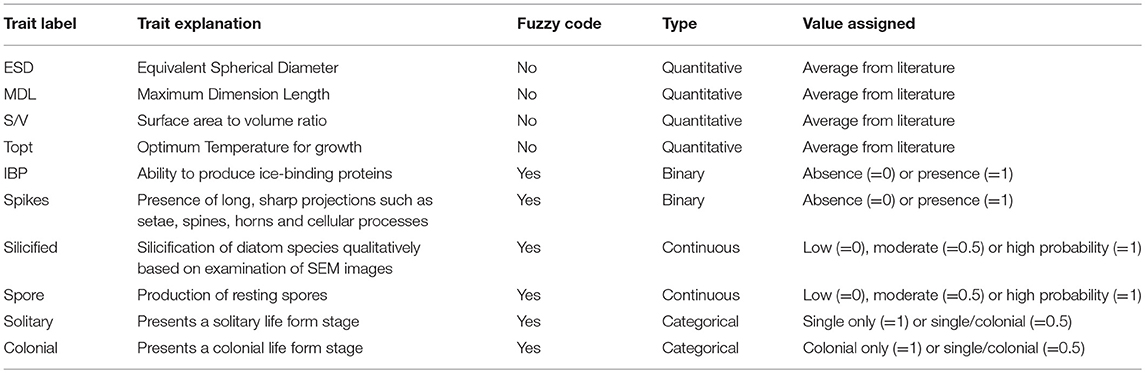

Some functional traits were considered quantitative, such as measurements of cell dimensions and optimum temperature for growth. In this case, average values of these traits were extracted from extensive databases (see Supplementary Data). Other traits were more complex to categorise or quantify, since species can display traits to different extents. For these traits, individual species were coded using a “fuzzy code” (Chevene et al., 1994), which allows species to exhibit a trait to a certain degree. These traits (herein termed continuous traits) were arbitrarily scaled to a value between 0 and 1 [i.e., lowest (= 0), intermediate (0.5), and highest (= 1) probability of species having that trait]. Finally, some traits were more straightforward, such as binary traits (i.e., presence or absence of that trait, so that yes = 1 and no = 0) (see Supplementary Data).

Quantitative cell dimension traits used in this analysis were the average of estimated spherical diameter (ESD), maximum dimension length (MDL), surface area to volume ratio (S/V), and optimum temperature for growth (Topt). Continuous traits, with characteristics that do not fit into defined groups, included traits related to life history strategies, such as those used in survival strategies (e.g., resting spore formation) and cell wall silicification. Resting spores were rarely observed in this study possibly because most have already been germinated at the time of sample collection (spring-summer). The information regarding whether a certain diatom species forms resting spores was based on the literature and on how often a species is found forming resting spores (see Supplementary Data). We found that this is a more valid approach, since it provides information on this life history trait, regardless of whether or not spores are present at the time of observation.

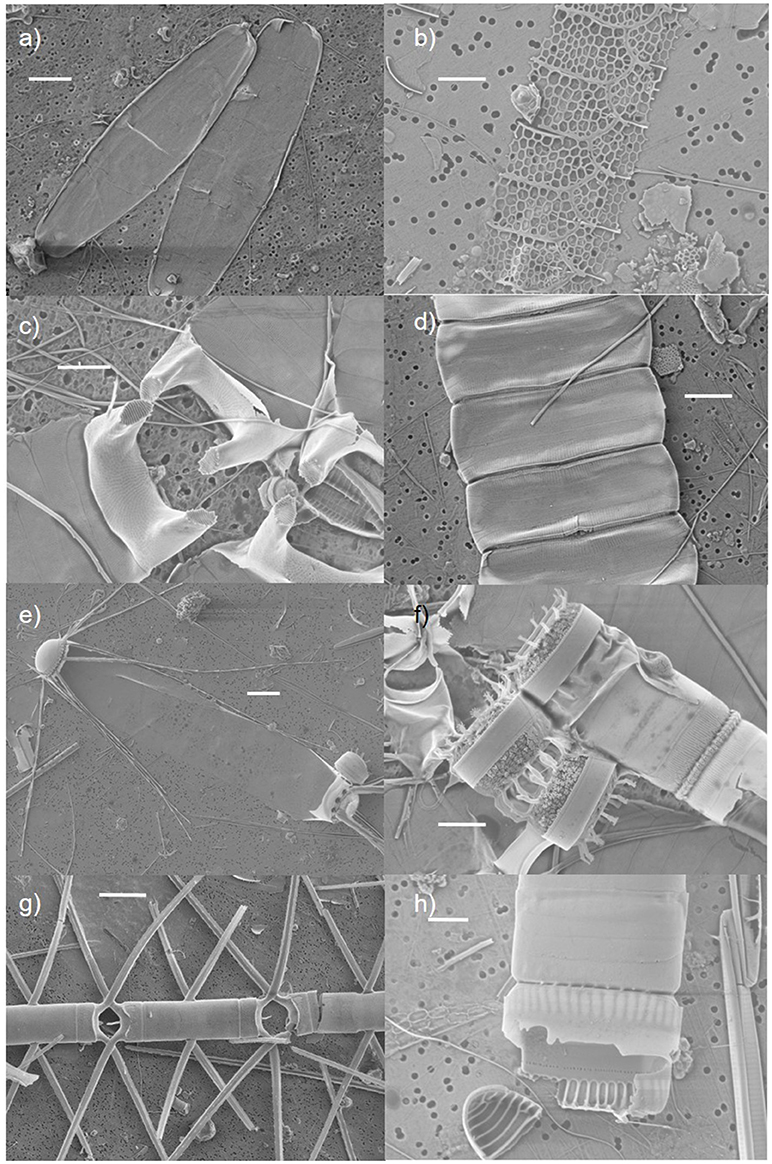

In the case of resting spore formation, traits were categorised as such: low probability of producing spores = 0, resting stages or seldom producing spores = 0.5 and spores produced frequently = 1. Cell wall silicification was qualitatively categorised based on SEM images (see examples in Figure 2). In case of diatom cell wall silicification, traits were categorised as weakly (= 0), moderate (= 0.5), or heavily silicified (= 1). Other functional traits, considered binary (i.e., no = 0; yes = 1), included (a) the ability to produce ice-binding proteins (IBP), and (b) the possession of long, sharp projections such as setae, spines, horns and other cellular processes (see Supplementary Data).

Figure 2. Diatom species images from the Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM). Examples of diatoms considered (1) weakly: (a) Ephemera planamembranacea, (b) Leptocylindrus mediterraneous, (c) Eucampia groenlandica, (2) moderately: (d) Pauliella taeniata, (e) Corethron criophilum, or (3) heavily silicified (f) Detonula confervacea, (g) Chaetoceros atlanticus, (h) Neodenticula seminae. Scale bars are 5 μm in figures (a–d,f,h) and 30 μm in (e,g).

The production of IBP was based on the information from the literature. Unfortunately, it is not possible to have information about the production of IBP for all diatom species listed, which limits our comprehension of how predominant this trait is in polar/subpolar diatoms. To circumvent this issue, we assumed that the production of IBP was absent in species where this information was not found (Supplemental Material). We assumed this as IBP production is regarded as an essential trait found in many sea ice microorganisms and unlikely to occur in temperate/non ice-related organisms (Janech et al., 2006; Raymond and Kim, 2012). Research by Uhlig et al. (2015) has previously shown that IBPs were found in a natural eukaryotic sea ice microbial community, including in many diatoms species found in this study (e.g., Fragilariopsis cylindrus).

Diatom traits, such as life form (solitary species or chain/colonial) were also included in the trait analysis (see Supplementary Data). These traits were selected as they may be used to infer species nutrient acquisition strategies, propensity to sink, and susceptibility to grazing (Litchman and Klausmeier, 2008). Formation of colonies, as well as cell or colonial shape and size, are considered plastic traits (Litchman and Klausmeier, 2008). However, these are particularly difficult to measure using non-automated techniques (e.g., microscopy), given that individual cell sizes may vary and colonies can be broken during sampling and/or preservation and storage. Moreover, some species, which are well-known to form chains or colonies, can also be observed in solitary forms (e.g., most Thalassiosira and Chaetoceros species). These traits were classified based on well-known information derived from the literature, which provides valuable information on the ecological significance of a species. Morphological traits were considered to be categorical traits, meaning that certain species can be found with two or more categories of a certain trait (e.g., Attheya septentronialis can be found in both cell forms: as single cells and small chains) (see Supplementary Data). The 10 diatom traits selected in this study are listed in Table 1.

Table 1. List of traits used in this study, in addition to the label, type and values assigned, and whether they were based or not on fuzzy code.

Community-weighted trait mean (CWM) is a straightforward method used to estimate trait variability on a community-level. CWM values were calculated for each trait, in each sample using a macro excel file “FunctDiv.xls” (Leps et al., 2006) (available at http://botanika.bf.jcu.cz/suspa/FunctDiv.php). CWM values were calculated from two matrices: (1) a matrix that gives trait values for each species, and (2) a matrix that has the relative biomass of each species in each sample. CWM calculated in this way gives a single community-wide trait value for each sample, according to the following equation:

where S is the number of species in the community, pi is each species' biomass proportion, and xi is the species-specific trait value. Each of the 10 traits was normalised in relation to the stations that presented the lowest (= 0) and the highest values (= 1) with the intention to standardise the CWM values among stations.

Statistical Analysis

Biogeographical patterns of diatom species in the Labrador Sea were analysed using the software Primer-E v.7 (Clarke and Warwick, 2001). The selection of target diatom species groups included the 50 most significant taxa in terms of biomass concentration (>70% of total biomass) that were identified to species/genus levels and/or were potential indicators of Atlantic and Arctic waters. Other unidentified diatom species that were not significant in terms of biomass (< 30% of total biomass) were excluded from the analysis.

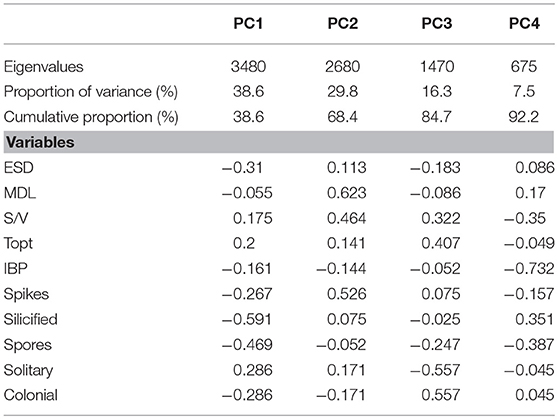

A principal component analyses (PCA, Primer-E v.7) was then used to analyse the overall variance of the standardised CWM diatom traits (explained above) occurring in stations of Arctic and Atlantic-influenced water. The “fuzzy code” method, which converted qualitative data into numerical variables to calculate the CWM, as well as the standardisation of the data, was performed to fulfill the premise of linearity in the PCA. The PCA was reduced to 4 orthogonal vectors to cover 92.2% of the total variance in the data (for factor loadings of PCA see Table 2). The first principal component (PC1), which explained most of the variance of the data (38.6%), was used to visualise the overall variance of CWM across sites of the Labrador Sea.

Non-parametric, pair-wise Spearman correlation coefficients and statistical significance (at p < 0.05) was calculated between diatom traits and environmental values using the statistical software R and the corrplot package. A non-parametric Mann-Whitney U-test was used to derive the statistical differences (p < 0.005) of CWM and environmental variables between sites of Arctic and Atlantic-influenced waters using the software Minitab (Version 18, Minitab, University Park, PA, USA). Similarity of traits (Bray-Curtis similarity) within samples (stations) was calculated using the Primer-E v.7 software. A similarity percentage analysis (SIMPER) routine was also analysed using the Primer-E v.7 software and was used to explore the dissimilarities/similarities (Bray-Curtis similarity) of CWM between/within Arctic and Atlantic regions. The output of SIMPER provides the average and the cumulative contribution of each CWM to the similarity/dissimilarity between regions (Arctic and Atlantic).

Results

Labrador Sea Hydrography

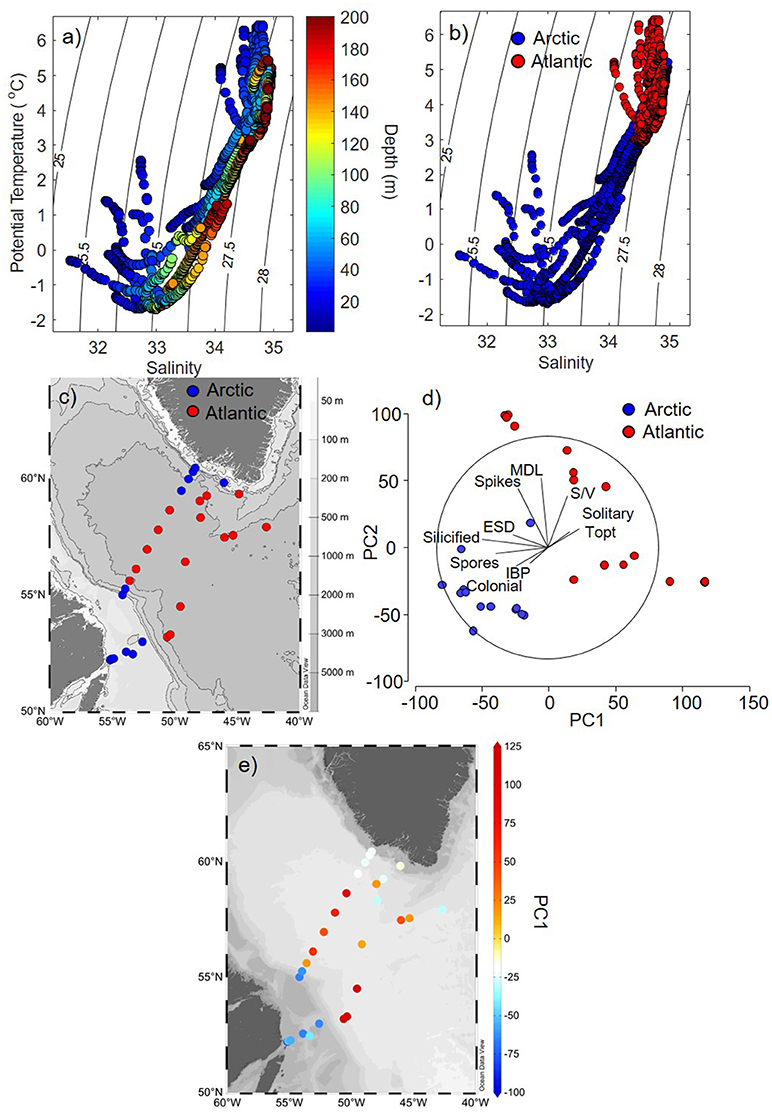

Stations in this study were classified as Arctic or Atlantic-influenced based on vertical distributions of potential temperature (T), salinity (S), and density. For this classification, we used a T-S analysis (Yashayaev, 2007) applied to high-resolution (1 m) vertical profiles covering the top 200 m, revealing all of the distinct water masses from the upper waters (<200 m) of the Labrador Sea. The T-S plots showed the partitioning and distribution of distinct water masses in stations considered Arctic- or Atlantic-influenced waters across the continental shelves, slopes and the central basin of the Labrador Sea (Figures 3a–c). Within the upper 200 m, Arctic-influenced stations (found on and near shelves and slopes) had water masses with a strong pycnocline, where the upper layer (< 100 m) was less dense (σθ < 27 kg m−3), colder (temperatures < 2°C), and fresher (salinity < 34) than waters of Atlantic-influenced stations (Figures 3a–c). In contrast, the stations dominated by Atlantic-related waters found in the central part of the Labrador Sea had a weaker pycnocline (upper 200 m) and were warmer (temperature > 1°C) and saltier (salinity > 33.5) (Figures 3a–c).

Figure 3. Hydrographic and ecological variability in the Labrador Sea. (a) Potential temperature and salinity vertical profiles (upper 200 m) with isopycnal contours as a function of depth and (b) as a function of stations that were characterised as Arctic or Atlantic-influenced. (c) Spatial distribution of stations categorised as belonging to Arctic (blue) or Atlantic-influenced (red) waters in the Labrador Sea. (d) Principal component analysis (PCA) for all diatom trait variables for each station categorised as being influenced by Arctic (blue) and Atlantic (red) waters. (e) Distributions of first axis (PC1, axis x in d) from the PCA analysis for each station of Labrador Sea, revealing common diatom traits found in Atlantic (red, positive PC1) and Arctic (blue, negative PC1) waters. Abbreviations in figure (d) refers to: ESD, equivalent spherical diameter; MDL, maximum dimension length; S/V, surface area to volume ratio; Topt, optimum temperature for growth; IBP, ice-binding proteins. The maps were generated using the software Ocean Data View (ODV, version 4.7.10, https://odv.awi.de/).

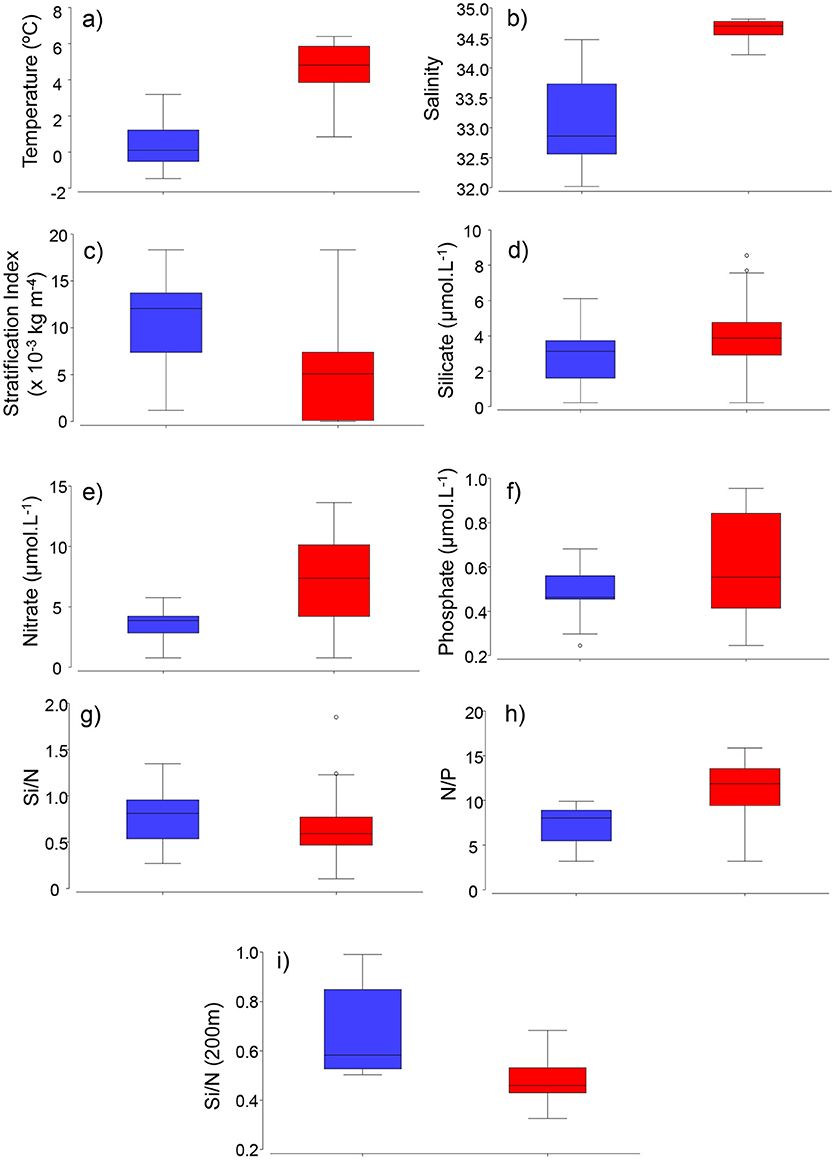

Water-column Stratification Index (SI) was higher at stations dominated by Arctic-related (median = 13 × 10−3 kg m−4) waters than Atlantic waters (median = 5 × 10−3 kg m−4, Figure 4, p = 0.0021, Mann-Whitney U-test). Surface waters (<10 m) of Atlantic-influenced stations presented slightly higher nitrate, silicate and phosphate, although differences were not significant (median = 7, 4, 0.6 μmol L−1, respectively, p > 0.005, Mann-Whitney U-test) when compared to stations with Arctic waters (Figure 4). Ratios of nitrate to phosphate (N/P) were significantly higher in surface waters of Atlantic (median = ratio of 12, Figure 4, p = 0.0005) stations than Arctic ones (Figure 4). Surface waters (<10 m) of Arctic-, compared to Atlantic stations, had slightly higher silicate (Si) to nitrate (N) ratios (p > 0.005, Mann-Whitney U-test), whereas Si/N ratios in deeper waters (>200 m) were significantly higher (p = 0.0001, Mann-Whitney U-test) and represent concentrations similar to pre-bloom conditions (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Boxplots of environmental factors. (a) temperature, (b) salinity, (c) stratification index (x 10−3 kg m−4), (d) silicate (μmol L−1), (e) nitrate (μmol L−1), (f) phosphate (μmol L−1), (g) Si/N, (h) N/P, (i) Si/N ratios at 200 m (winter and/or pre-bloom values) in Arctic (blue) and Atlantic (red) -influenced waters of the Labrador Sea.

Diatom Species Biogeography

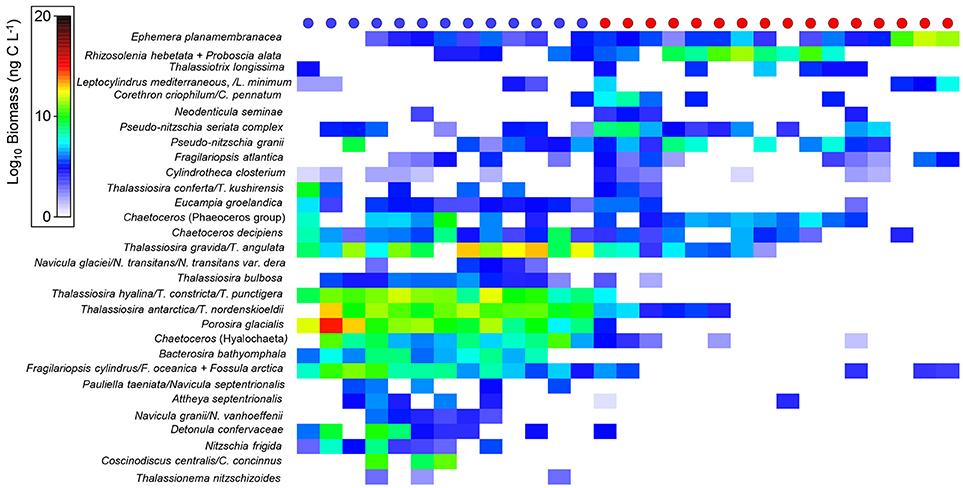

Diatom species biomass varied among the different water types (Arctic vs. Atlantic-influenced), suggesting an effect of hydrography in determining species composition. For instance, some species, such as Nitzschia frigida, Navicula granii, N. glaciei, N. transitans, N. transitans var. derasa, N. vanhoeffenii, Pauliella taeniata, N. septentrionalis, Fossula arctica, Thalassiosira hyalina, T. constricta, T. bulbosa, Bacterosira bathyomphala, were found at stations with Arctic-related waters in this study (see Figure 5 for a complete list of biogeographical partitioning of diatom species). Most diatoms, however, were not categorised as being indicators exclusively of Arctic or North Atlantic waters; instead, trends in biomass among these hydrographic zones were observed to determine the habitat preferences of selected species. For example, in this study, Bacterosira bathyomphala was one of the few diatoms found in Arctic waters, whereas Ephemera planamembranacea was found in both water masses though in considerably higher numbers in Atlantic waters (Figure 5). Rhizosolenia hebetata f. semispina, Proboscia alata, Corethron sp., and Pseudo-nitzschia sp. were also found in high biomasses in Atlantic waters (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Biomass (ng C L−1) (after log-transformation) of diatom species found in stations (circles at the top) categorised as Arctic- (blue) or Atlantic-influenced (red).

Diatom Functional Traits

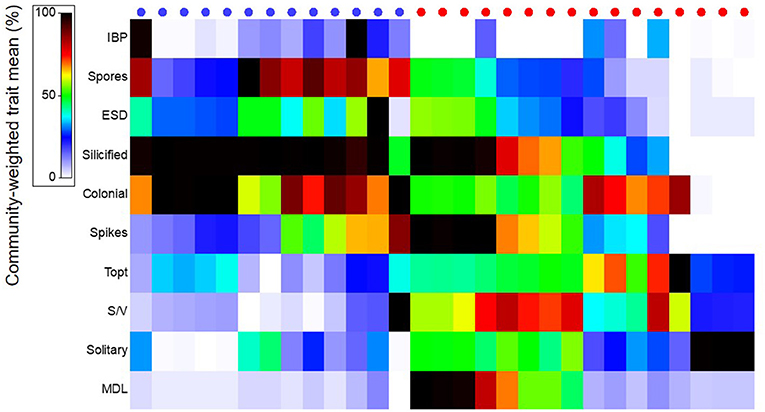

Diatoms from Arctic and Atlantic-originated waters showed distinct functional traits, where the first principal component explained 38.6% of the variance of CWM among stations from different regions (Arctic vs. Atlantic) [Figure 3d, first axis of principal component analysis (PC-1)]. The overall similarity (Bray-Curtis) of species composition in each community in terms of their traits were higher for diatoms from Arctic [average group similarity = 75%, SIMilarity PERcentages (SIMPER) analysis] than Atlantic waters (average group similarity = 60%, SIMPER), indicating that species from the Arctic shared unique characteristics that enable them to thrive in these waters. Diatoms from Arctic waters, when compared to diatoms from Atlantic waters, had the following traits: were more heavily silicified, colonial and had a higher propensity to produce resting spores and form ice-binding proteins (IBPs) (Figures 3d, e, 6, p < 0.005, Mann-Whitney U-test).

Figure 6. Community-weighted trait mean of diatom species (%) found in Arctic- (blue) and Atlantic (red) influenced stations (circles at the top). Trait abbreviations are explained in Figure 3.

Traits observed in diatoms from stations with Atlantic-influenced waters presented opposite trends to those observed from the Arctic (Figures 3d, e, 6). For instance, diatom species from Atlantic waters had higher optimum growth temperatures (Topt) and were single cells prolonged in shape, which contributed to the higher S/V and MDL observed (p < 0.005, Mann-Whitney U-test) when compared to Arctic diatoms. Diatoms at several stations where Atlantic waters were dominant were also weakly silicified compared to the majority of Arctic-related species, and very few of these species produce resting spores (Figure 6, p < 0.005, Mann-Whitney U-test).

Diatom Functional Traits and Environmental Relationships

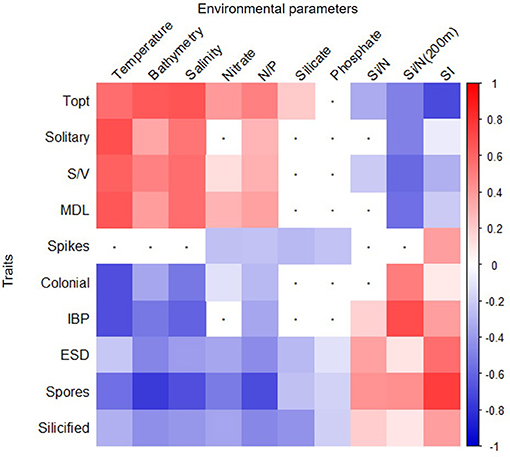

Pairwise correlation showed that certain traits presented similar patterns of correlation with a group of environmental factors (Figure 7). For example, cells that were found in a solitary form, had a high S/V and MDL and had a high Topt (average of 5°C) correlated positively with temperature, bathymetry, salinity, nitrate concentrations, and N/P and negatively correlated with Si/N from winter conditions [Si/N (200 m)] and water column stratification (p < 0.05, Spearman correlation, Figure 7). Conversely, traits, such as large cell size [>equivalent spherical diameter (ESD)], heavy cell wall silicification, colony formation, ability to produce resting spore, and IBPs were positively correlated with cold, fresh, shallow, and stratified waters that had high Si/N as found in spring and winter conditions [Si/N (200 m)] (p < 0.05, Spearman correlation, Figure 7). Figure 7 shows the pairwise correlations between all traits and environmental variables.

Figure 7. Spearman correlation plot of environmental factors and diatom species traits. Statistically significant (p < 0.005) positive (red) and negative (blue) correlations are shown for each combination. White squares with black dots refer to non-statistically significant relationships. Trait abbreviations are explained in Figure 3. Environmental abbreviations refer to Stratification Index (SI) nitrate to phosphate (N/P) and silicate to nitrate concentrations ratio at the surface (Si/N) or at 200 m (Si/N 200 m).

Discussion

The Labrador Sea receives inputs of both North Atlantic and Arctic waters, where marked frontal features shape the hydrography along the water masses boundaries (Yashayaev, 2007). In spite of the hydrographical contrast of water masses of Atlantic and Arctic origin found in the Labrador Sea, modification of these waters occurs to some degree, where strong mesoscale physical processes, such as eddies, in addition to riverine and ice melt input (from sea ice, glaciers, and icebergs) lead to mixing, particularly during spring and summer (Wu et al., 2007; Straneo and Saucier, 2008; Yebra et al., 2009).

Few typical Arctic diatom species, such as Bacterosira bathyomphala and Pauliella taeniata (von Quillfeldt, 2001), were found only in Arctic waters in this study. Rather, the majority of diatom species were not categorised solely as being indicators exclusively of Arctic or North Atlantic waters because of the mixing of water masses and the ubiquitous distribution of certain cold-water species in both water masses (e.g., Chaetoceros decipiens) (Tomas, 1997). The diatom species biomasses, conversely, varied strongly between the different water masses of Arctic and Atlantic origin, suggesting that environmental factors selected for the growth and maintenance of a species' population under distinct conditions. This implies that certain traits, common to the different diatom species that co-occur in a mixed community, shaped the biogeographical distribution of these taxa.

The community-weighted trait mean (CWM) approach used in this study assumes that functional traits occurring in a system result from the quantitative records (abundance or biomass) of the individuals carrying these traits (Frainer et al., 2017). Trait-based analysis using CWM is relatively novel in phytoplankton research (Kruk et al., 2015; Klais et al., 2017), perhaps because of the difficulty in identifying phytoplankton to a species level and finding relevant trait information in the literature. CWM was suitable for this study because of the high degree of taxonomic resolution (>70% of total diatom biomass were identified to species' level using the SEM) and trait information available for polar/subpolar diatoms. Other methods, such as modelling of key species are also useful in trait-based approaches because they investigate the mechanisms underlying the structure of a community, in addition to providing future predictions (Edwards et al., 2013a, 2016). However, because of their simplistic resolution, such model-based approaches may also lead to underestimation of other meaningful traits present in a community (Irwin and Finkel, 2017), by disregarding the multi-faceted functions of a species (Paganelli et al., 2012). The main advantage of using CWM when taxonomy (species) information is provided is that the whole (or at least the majority) of the community is assessed, giving an overall picture of the key functional traits of a community. Although considered a hypothetical approach, trait-based analysis based on CWM can be very insightful and can lead to further hypothesis-testing.

According to the trait-based approach based on CWM, the ability to produce IBPs was one trait commonly found in diatom assemblages from Arctic waters, indicating that these species originated from sea ice. Examples of sea ice diatoms found in the water column in this study (though in low concentrations) are Navicula glaciei, Attheya septentrionalis, and Nitzschia frigida, with the latter forming arborescent colonies that help to anchor them under ice-floes (Olsen et al., 2017). Release of sea ice diatoms from melting ice, transfer of sympagic (ice-associated) algae to the pelagic community and accumulation in the water column has been assumed to be the primary causes for bloom development in ice melting regions (Syvertsen, 1991; Leventer and Dunbar, 1996; Ichinomiya et al., 2008), although most sympagic diatoms tend to sink to the seafloor, given that they are unable to adapt to ice free waters (Riaux-Gobin et al., 2011). As the Labrador Shelf is a seasonal ice zone (SIZ), where sea ice melts from spring to early summer (Wu et al., 2007), this explains the presence of sea ice diatoms that are also typically found as planktonic forms (e.g., Fragilariopsis cylindrus) and were present in high concentrations in Arctic waters in this study. Sea ice-melt also provides a haline-stratified layer, where species associated with the transition from sea ice to meltwater and pelagic habitats are suddenly exposed to high-light levels (Smith and Nelson, 1985). This implies that while sympagic diatoms are known to be adapted to low light, transitional (from ice to water column) species have a high plasticity to cope with rapid and relatively large changes in irradiance.

Fragilariopis cylindrus, a diatom species found in large abundances in the sea ice as well as in the water column has been shown to display high degrees of phenotypic plasticity to environmental fluctuations (Kropuenske et al., 2009, 2010; Petrou et al., 2010; Sackett et al., 2013), which suggest that this might be an underlying functional trait in this study. The whole-genome sequence of F. cylindrus shows a high number (25%) of divergent alleles that are differently expressed across variable conditions, and which might be involved in adaptation of this species to rapid environmental fluctuations (Mock et al., 2017). The high gene number of chlorophyll a/c light-harvesting complexes and proteins involved in photo-protection (Mock et al., 2017) may help to explain why F. cylindrus is successful in low and high-light conditions, such as the transition from sea ice to the water column. Other physiological traits, such as the production of photosynthetic carotenoids, UV-protection, and intracellular osmoregulation, have been suggested to be associated with species that produce IBP and could explain the success of ice-related algae in Arctic waters (Mock and Junge, 2007).

Diatom assemblages in Arctic waters also included species that were able to form heavily silicified resting spores. Resting spore formation is a strategy to overcome unfavourable environmental conditions commonly found in Arctic waters, such as low (Zhang et al., 1998) or high light (Oku and Kamatani, 1999), low temperatures (Durbin, 1978), and low nitrate (Kuwata and Takahashi, 1999), phosphorus (Oku and Kamatani, 1995), or iron (Sugie and Kuma, 2008) concentrations. High silicate to nitrate ratios (Si/N) are typical of Arctic waters, including those of the Labrador Shelf, particularly in pre-bloom conditions (> Si/N are found in Arctic waters as compared to Atlantic waters in winter) (Fragoso et al., 2017). These high Si/N ratios likely promote the occurrence of diatom species able to form resting spores, since formation often occurs when there is an excess of Si (relative to N) (Kuwata and Takahashi, 1990). The ability to produce resting spores is also a trait common among neritic diatom species (Garrison, 1981) and, as expected, its level of occurrence was negatively correlated with bathymetry in this study. As the winter progresses, the growth conditions become sub-optimal and resting spores are formed and passively incorporated into sea-floor sediments (and/or sea ice), to be re-introduced into the water-column during spring-time mixing (and sea ice melting) prior to bloom formation. Resting spores are often interpreted as a proxy for sea ice melting (Crosta et al., 2008), and are an important life-cycle strategy for planktonic species that thrive on sea ice melt (e.g., many Thalassiosira, Fragilariopsis, and Chaetoceros species) (Tsukazaki et al., 2013). This suggests that resting spore formation is a common trait in Arctic waters influenced by the seasonal presence of sea ice.

Arctic-related diatoms also shared morphological traits, regardless of their phylogenetic relationship, in this study and elsewhere (Ichinomiya et al., 2008; Arrigo et al., 2010, 2014; Riaux-Gobin et al., 2011; Tsukazaki et al., 2013; Johnsen et al., 2018), such as similar cell and colony shape and low cellular surface-to-volume ratio (S/V). The morphological shapes in Arctic diatoms resembled rectangular prism cells and ribbon-shaped chains (e.g., Fragilariopsis cylindrus, F. oceanica, Fossula arctica, Pauliella taeniata, Navicula septentrionalis, N. granii, N. vanhoeffenii), as well as cylindrical cells and thread-like chains (e.g., most Thalassiosira spp., Porosira glacialis). The “bulky” shape of these diatoms contributed to the low S/V ratios, such as those observed in Coscinodiscus centralis and C. concinnus, Porosira glacialis, and Bacterosira bathyomphala; all species typically found in Arctic waters. Large centric diatoms, with low S/V ratios, also have lower optical absorption cross-sections, which protects them from visible and ultraviolet damage during the high-light levels (Key et al., 2010) typically observed in well-illuminated, ice-melt and shallow stratified Arctic waters (Fragoso et al., 2016, 2017).

Large and heavily silicified diatoms, such as those found in stratified Arctic waters in this study, would tend to sink faster, particularly in non-turbulent waters (Margalef, 1978). However, to avoid sinking, healthy diatoms (> 200 μm3 in cell volume = c.a. 8 μm equivalent spherical diameter) have developed trade-off strategies to encourage positive buoyancy, such as cellular vacuoles filled with low-density ions (Woods and Villareal, 2008), light-weight fatty acids (Duerksen et al., 2014), and extracellular mucous material (Assmy et al., 2013a). Another strategy is the presence of cellular protrusions, such as setae, spines, and long processes, which improves the cell's ability to increase its shear rate (and slow its sinking). In our study, the presence of cellular protrusions was positively correlated with stratification, suggesting that these may slow-down sinking rates of large, dense cells (Nguyen et al., 2011). Arctic diatoms also control their buoyancy in order to mine deeper waters for essential nutrients under low nutrient concentrations, similar to those observed in this study. These diatoms can be categorised as “S-strategists” (stress-tolerant), given that they are large-celled species with low S/V ratios, slow growth rates and are adapted to high-light conditions (Alves-de-Souza et al., 2008).

The Atlantic-related diatom species also shared similar traits among themselves, such as large S/V, MDL, high optimum growth temperatures, and many were solitary forms. Diatoms from Atlantic waters, however, showed less similarity in their CWM (average similarity = 60%, SIMPER analysis) compared to those in Arctic waters (75%). This may be due to high environmental variability, such as may occur during the transition from un-stratified to thermally-stratified waters, as typically occurs in the Atlantic waters of the central Labrador Sea between May and June (Fragoso et al., 2016, 2017). In our study, large S/V and MDL were correlated, and in North Atlantic waters diatom assemblages were characterised by species resembling needle-like cells, such as Cylindrotheca closterium, Thalassiothrix longissima, Thalassionema nitzschoides, and Pseudo-nitzchia granii. Elongated cell shapes have been suggested to improve a cell's ability to maximise nutrient uptake efficiency and light harvesting in a turbulently mixed environment, since it may increase the spin of cells and maintain concentration gradients across the diffusive boundary layer (Smetacek, 1985; Pahlow et al., 1997; Nguyen et al., 2011). Atlantic waters were also less well-stratified (with the exception of a few stations where Rhizosolenia hebetata f. semispina dominated) and had deeper mixed layers, which may favour species which are able to cope with turbulent environments. These diatoms are typical “R-strategists” (disturbance-tolerant), which are species that grow under high nutrient concentrations and are often elongated in cell shape, despite their large dimensions (high S/V), conferring on them the advantage of effectively harvesting light under high mixing (low average light) conditions (Alves-de-Souza et al., 2008).

Diatoms at several stations of Atlantic waters were also weakly silicified compared to the majority of Arctic-related species (Figure 2). Such low cell silicification may relate to the low pre-bloom Si/N ratios characteristic of Atlantic waters, as observed more generally in the North Atlantic (Fragoso et al., 2017). Weakly silicified species include Leptocylindrus mediterraneous and Ephemera planamembranacea, both of which bloom in North Atlantic waters (Le Moigne et al., 2015; Fragoso et al., 2016).

Diatom species optimum growth temperatures in this study were correlated positively with in situ water temperature in both Arctic and Atlantic water masses. However, several diatom species appeared to be restricted to cold, Arctic-influenced waters, whereas others that were more abundant in Atlantic water were also found in Arctic waters, although in lower concentrations (e.g., E. planamembranacea and Pseudo-nitzschia granii). Generally, temperate and polar diatom species have wider thermal tolerances than tropical species and are able to survive under a wide range of environmental conditions (Thomas et al., 2012), which suggests that temperature may have little influence in shaping diatom species distribution in the Labrador Sea. Rather, other factors such as sea ice-melt phenology may serve to confine Arctic diatoms in the Labrador Sea, of which many are sea ice species and/or able to grow in highly stratified, ice melt-regions.

Changes in the Arctic are increasingly evident, including rising temperatures, sea ice decline and increasing freshening of surface waters (Anisimov et al., 2007). Several ecological questions have thus arisen, including whether “the Arctic will be the New Atlantic” if sea ice-melt persists (Yool et al., 2015). Many studies have revealed changes in phytoplankton community composition as a consequence of climate change, such as the intrusion of Atlantic species into high Arctic waters (Hegseth and Sundfjord, 2008). In this study, several phytoplankton species appeared to be restricted to Arctic-influenced waters, whereas some other species, abundant in North Atlantic waters, were also found in Arctic waters but in lower concentrations (e.g., Ephemera planamembranacea). This suggests that species abundant in Arctic-related waters have a more restricted distribution, potentially indicating a greater dependence of certain species to a sea ice or ice-influenced habitat, and well-illuminated and strongly stratified waters.

Sea ice is one of the largest and most extreme habitats in polar oceans, comprising up to 13% of Earth's surface at its maximum (Mock and Junge, 2007). Predictions show that the Arctic will have a total ice free summer by mid-twenty-first century (Wang and Overland, 2012). Loss of sea ice coverage indicates loss of species habitat, with potential losses of diversity and reductions in diatom blooms associated with sea ice melting (Yool et al., 2015). Our results have shown that diatoms from Arctic waters had more similar traits (and consequently less functional diversity) compared to Atlantic diatoms, indicating that the species from the Arctic shared unique characteristics that enable them to thrive in these waters. Traits that are linked to sea ice or Arctic phytoplankton species, such as ability to survive under extreme cold and harsh environments will also tend to decline, implying a great risk to seeding algae and bloom initiation. Diatoms that rely on sea ice to hibernate as resting spores and germinate under stratified conditions will be affected as sea ice cover declines.

In this study, we found that morphological and physiological traits are strongly linked to spring diatom biogeography in Arctic and Atlantic waters. This demonstrates that a functional trait evaluation is a valuable approach to understand changes in phytoplankton communities. Potential applications include examining species succession during seasonal events, such as spring blooms, in long-term time-series data (Barton et al., 2016), or during future environmental perturbation (Tortell et al., 2002).

Author Contributions

GF designed and led the study, collecting and analysing the data. IY and EH provided part of the data. GF wrote the initial draft of the paper and GF, AP, and DP supervised the project and together with GJ edited subsequent drafts. All authors provided critical comments on the final manuscript.

Funding

GF was funded by a Brazilian PhD studentship, Science without Borders (CNPq, 201449/2012-9). This research was also partially funded by the National Environment Research Council (NERC) via its UK Ocean Acidification research program as an added value award to AP (NE/H017097/1). GJ was funded by contributions from the Centre of Excellence at NTNU AMOS (NRC, Norwegian Research Council, Project 223254).

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the officers, crew, technicians and scientists on board of the CCGS Hudson and RSS James Clark Ross. The contribution of Fisheries and Oceans Canada to this work was carried as a part of the Atlantic Zone Off-Shelf Monitoring Program (AZOMP) providing annual Labrador-to-Greenland full-ocean-depth physical and biochemical sampling of the Labrador Sea. Specific thanks go to Mark Stinchcombe and Sinhue Torres-Valdes for sample collection and access to nutrient data. Part of the data of this study has been published in: Fragoso (2016). Biogeography of spring phytoplankton communities from the Labrador Sea: drivers, trends, ecological traits, and biogeochemical implications. PhD thesis, University of Southampton.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmars.2018.00297/full#supplementary-material

Abbreviations

chl a, chlorophyll a; CWM, community-weighted trait mean; ESD, equivalent spherical diameter; IBP, ice-binding proteins; LM, light microscope; MDL, maximum dimension length; N/P, nitrate to phosphate concentration ratio at the surface (<10 m); PC1, first principal component; PCA, Principal component analyses; SEM, Scanning electron microscope; SI, stratification index; Si/N, silicate to nitrate concentration ratio at the surface (<10 m); Si/N (200 m), silicate to nitrate concentration ratio at 200 m; SIMPER, similarity percentage analysis; S/V, surface area to volume ratio; Topt, optimum temperature for growth.

References

Algarte, V. M., Pavan, G., Ferrari, F., and Ludwig, T. A. V. (2016). Biological traits of diatoms in the characterization of a reservoir and a stream in a subtropical region. Braz. J. Bot. 40, 137–144. doi: 10.1007/s40415-016-0322-7

Allen, C. S. (2014). Proxy development: a new facet of morphological diversity in the marine diatom Eucampia antarctica (Castracane) Mangin. J. Micropalaeontol. 33, 131–142. doi: 10.1144/jmpaleo2013-025

Alves-de-Souza, C., Gonzalez, M. T., and Iriarte, J. L. (2008). Functional groups in marine phytoplankton assemblages dominated by diatoms in fjords of southern Chile. J. Plankton Res. 30, 1233–1243. doi: 10.1093/plankt/fbn079

Anisimov, O. A., Vaughan, D. G., Callaghan, T. V., Furgal, C., Marchant, H., Prowse, T. D., et al. (2007). “Polar regions (Arctic and Antarctic),” in Climate Change 2007, Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), 653–685.

Arrigo, K. R., Brown, Z. W., and Mills, M. M. (2014). Sea ice algal biomass and physiology in the Amundsen Sea, Antarctica. Elem. Sci. Anthrop. 2:28. doi: 10.12952/journal.elementa.000028

Arrigo, K. R., Mock, T., and Lizotte, M. P. (2010). “Primary producers and sea ice,” in Sea Ice, eds D. N. Thomas and G. S. Dieckmann (Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell), 283–325.

Assmy, P., Ehn, J. K., Fernández-Méndez, M., Hop, H., Katlein, C., Sundfjord, A., et al. (2013a). Floating ice-algal aggregates below melting arctic sea ice. PLoS ONE 8:e76599. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0076599

Assmy, P., Smetacek, V., Montresor, M., Klaas, C., Henjes, J., Strass, V. H., et al. (2013b). Thick-shelled, grazer-protected diatoms decouple ocean carbon and silicon cycles in the iron-limited Antarctic circumpolar current. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110, 20633–20638. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1309345110

Barton, A. D., Finkel, Z. V., Ward, B. A., Johns, D. G., and Follows, M. J. (2013a). On the roles of cell size and trophic strategy in North Atlantic diatom and dinoflagellate communities. Limnol. Oceanogr. 58, 254–266. doi: 10.4319/lo.2013.58.1.0254

Barton, A. D., Irwin, A. J., Finkel, Z. V., and Stock, C. A. (2016). Anthropogenic climate change drives shift and shuffle in North Atlantic phytoplankton communities. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 113, 2964–2969. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1519080113

Barton, A. D., Pershing, A. J., Litchman, E., Record, N. R., Edwards, K. F., Finkel, Z. V., et al. (2013b). The biogeography of marine plankton traits. Ecol. Lett. 16, 522–534. doi: 10.1111/ele.12063

Beaugrand, G., Reid, P. C., Ibañez, F., Lindley, J. A., and Edwards, M. (2002). Reorganization of North Atlantic marine copepod biodiversity and climate. Science 296, 1692–1694. doi: 10.1126/science.1071329

Brun, P., Vogt, M., Payne, M. R., Gruber, N., O'Brien, C. J., Buitenhuis, E. T., et al. (2015). Ecological niches of open ocean phytoplankton taxa. Limnol. Oceanogr. 60, 1020–1038. doi: 10.1002/lno.10074

Cermeño, P., de Vargas, C., Abrantes, F., and Falkowski, P. G. (2010). Phytoplankton biogeography and community stability in the ocean. PLoS ONE 5:e10037. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010037

Cermeno, P., and Falkowski, P. G. (2009). Controls on diatom biogeography in the ocean. Science 325, 1539–1541. doi: 10.1126/science.1174159

Chevene, F., Doleadec, S., and Chessel, D. (1994). A fuzzy coding approach for the analysis of long-term ecological data. Freshw. Biol. 31, 295–309. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2427.1994.tb01742.x

Clarke, K. R., and Warwick, R. M. (2001). Change in Marine Communities: An Approach to Statistical Analysis and Interpretation, 2nd Edn. Plymouth: PRIMER-E.

Cornelissen, J. H. C. A., Lavorel, S. B., Garnier, E. B., Díaz, S. C., Buchmann, N. D., Gurvich, D. E. C., et al. (2003). A handbook of protocols for standardised and easy measurement of plant functional traits worldwide. Aust. J. Bot. 51, 335–380. doi: 10.1071/BT02124

Crosta, X., Denis, D., and Ther, O. (2008). Sea ice seasonality during the Holocene, Adélie Land, East Antarctica. Mar. Micropaleontol. 66, 222–232. doi: 10.1016/j.marmicro.2007.10.001

Daniels, C. J., Tyrrell, T., Poulton, A. J., and Pettit, L. (2012). The influence of lithogenic material on particulate inorganic carbon measurements of coccolithophores in the Bay of Biscay. Limnol. Oceanogr. 57, 145–153. doi: 10.4319/lo.2012.57.1.0145

Dickson, B., Yashayaev, I., Meincke, J., Turrell, B., Dye, S., and Holfort, J. (2002). Rapid freshening of the deep North Atlantic Ocean over the past four decades. Nature 416, 832–837. doi: 10.1038/416832a

Duerksen, S. W., Thiemann, G. W., Budge, S. M., Poulin, M., Niemi, A., and Michel, C. (2014). Large, omega-3 rich, pelagic diatoms under arctic sea ice: sources and implications for food webs. PLoS ONE 9:e114070. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0114070

Durbin, E. G. (1978). Aspects of the biology of resting spores of Thalassiosira nordenskioeldii and Detonula confervacea. Mar. Biol. 45, 31–37. doi: 10.1007/BF00388975

Edwards, K. F., Klausmeier, C. A., and Litchman, E. (2015). Nutrient utilization traits of phytoplankton. Ecology 96, 2311–2311. doi: 10.1890/14-2252.1

Edwards, K. F., Litchman, E., and Klausmeier, C. A. (2013a). Functional traits explain phytoplankton community structure and seasonal dynamics in a marine ecosystem. Ecol. Lett. 16, 56–63. doi: 10.1111/ele.12012

Edwards, K. F., Litchman, E., and Klausmeier, C. A. (2013b). Functional traits explain phytoplankton responses to environmental gradients across lakes of the United States. Ecology 94, 1626–1635. doi: 10.1890/12-1459.1

Edwards, K. F., Thomas, M. K., Klausmeier, C. A., and Litchman, E. (2016). Phytoplankton growth and the interaction of light and temperature: a synthesis at the species and community level. Liminol. Oceanogr. 61, 1232–1244. doi: 10.1002/lno.10282

Follows, M. J., Dutkiewicz, S., Grant, S., and Chisholm, S. W. (2007). Emergent biogeography of microbial communities in a model ocean. Science 315, 1843–1846. doi: 10.1126/science.1138544

Fragoso, G. M. (2016). Biogeography of Spring Phytoplankton Communities from the Labrador Sea: Drivers, Trends, Ecological Traits and Biogeochemical Implications. Doctoral thesis, University of Southampton, Ocean & Earth Science, 187.

Fragoso, G. M., Poulton, A. J., Yashayaev, I. M., Head, E. J. H., and Purdie, D. A. (2017). Spring phytoplankton communities of the labrador sea (2005–2014): pigment signatures, photophysiology and elemental ratios. Biogeosciences 14, 1235–1259. doi: 10.5194/bg-14-1235-2017

Fragoso, G. M., Poulton, A. J., Yashayaev, I. M., Head, E. J. H., Stinchcombe, M. C., and Purdie, D. A. (2016). Biogeographical patterns and environmental controls of phytoplankton communities from contrasting hydrographical zones of the labrador Sea. Prog. Oceanogr. 141, 212–226. doi: 10.1016/j.pocean.2015.12.007

Frainer, A., Primicerio, R., Kortsch, S., Aune, M., Dolgov, A. V., Fossheim, M., et al. (2017). Climate-driven changes in functional biogeography of Arctic marine fish communities. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 114, 12202–12207. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1706080114

Garrison, D. L. (1981). Monterey Bay phytoplankton. II. Resting spore cycles in coastal diatom populations. J. Plankton Res. 3, 137–156. doi: 10.1093/plankt/3.1.137

Glibert, P. M. (2016). Margalef revisited: a new phytoplankton mandala incorporating twelve dimensions, including nutritional physiology. Harmful Algae 55, 25–30. doi: 10.1016/j.hal.2016.01.008

Head, E. J. H., Harris, L. R., and Yashayaev, I. (2003). Distributions of Calanus spp. and other mesozooplankton in the labrador sea in relation to hydrography in spring and summer (1995-2000). Prog. Oceanogr. 59, 1–30. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6611(03)00111-3

Head, E. J. H., Melle, W., Pepin, P., Bagøien, E., and Broms, C. (2013). On the ecology of Calanus finmarchicus in the Subarctic North Atlantic: a comparison of population dynamics and environmental conditions in areas of the Labrador Sea-Labrador/Newfoundland Shelf and Norwegian Sea Atlantic and Coastal Waters. Prog. Oceanogr. 114, 46–63. doi: 10.1016/j.pocean.2013.05.004

Hegseth, E. N., and Sundfjord, A. (2008). Intrusion and blooming of Atlantic phytoplankton species in the high Arctic. J. Mar. Syst. 74, 108–119. doi: 10.1016/j.jmarsys.2007.11.011

Ichinomiya, M., Nakamachi, M., Fukuchi, M., and Taniguchi, A. (2008). Resting cells of microorganisms in the 20–100μm fraction of marine sediments in an Antarctic coastal area. Polar Sci. 2, 27–32. doi: 10.1016/j.polar.2007.12.001

Irwin, A. J., and Finkel, Z. (2017). Phytoplankton functional types: a trait perspective. bioRxiv. [preprint] doi: 10.1101/148312

Jamil, T., Kruk, C., and ter Braak, C. J. F. (2014). A unimodal species response model relating traits to environment with application to phytoplankton communities. PLoS ONE 9:e97583. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0097583

Janech, M. G., Krell, A., Mock, T., Kang, J.-S., and Raymond, J. A. (2006). Ice-Binding Proteins From Sea Ice Diatoms (Bacillariophyceae)1. J. Phycol. 42, 410–416. doi: 10.1111/j.1529-8817.2006.00208.x

Johnsen, G., Norli, M., Moline, M., Robbins, I., von Quillfeldt, C., Sørensen, K., et al. (2018). The advective origin of an under-ice spring bloom in the Arctic Ocean using multiple observational platforms. Polar Biol. 41, 1197–1216. doi: 10.1007/s00300-018-2278-5

Key, T., McCarthy, A., Campbell, D. A., Six, C., Roy, S., and Finkel, Z. V. (2010). Cell size trade-offs govern light exploitation strategies in marine phytoplankton. Environ. Microbiol. 12, 95–104. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2009.02046.x

Klais, R., Norros, V., Lehtinen, S., Tamminen, T., and Olli, K. (2017). Community assembly and drivers of phytoplankton functional structure. Funct. Ecol. 31, 760–767. doi: 10.1111/1365-2435.12784

Kropuenske, L. R., Mills, M. M., Van Dijken, G. L., Alderkamp, A. C., Mine Berg, G., Robinson, D. H., et al. (2010). Strategies and rates of photoacclimation in two major southern ocean phytoplankton taxa: Phaeocystis antarctica (haptophyta) and Fragilariopsis cylindrus (bacillariophyceae). J. Phycol. 46, 1138–1151. doi: 10.1111/j.1529-8817.2010.00922.x

Kropuenske, L. R., Mills, M. M., van Dijken, G. L., Bailey, S., Robinson, D. H., Welschmeyer, N. A., et al. (2009). Photophysiology in two major Southern Ocean phytoplankton taxa: Photoprotection in Phaeocystis antarctica and Fragilariopsis cylindrus. Limnol. Oceanogr. 54, 1176–1196. doi: 10.4319/lo.2009.54.4.1176

Kruk, C., Huszar, V. L. M., Peeters, E. T. H. M., Bonilla, S., Costa, L., Lurling, M., et al. (2010). A morphological classification capturing functional variation in phytoplankton. Freshw. Biol. 55, 614–627.doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2427.2009.02298.x

Kruk, C., Martínez, A., Nogueira, L., Alonso, C., and Calliari, D. (2015). Morphological traits variability reflects light limitation of phytoplankton production in a highly productive subtropical estuary (Río de la Plata, South America). Mar. Biol. 162, 331–341. doi: 10.1007/s00227-014-2568-6

Kuwata, A., and Takahashi, M. (1990). Life-form population responses of a marine planktonic diatom, Chaetoceros pseudocurvisetus, to oligotrophication in regionally upwelled water. Mar. Biol. 107, 503–512. doi: 10.1007/BF01313435

Kuwata, A., and Takahashi, M. (1999). Survival and recovery of resting spores and resting cells of the marine planktonic diatom Chaetoceros pseudocurvisetus under fluctuating nitrate conditions. Mar. Biol. 134, 471–478. doi: 10.1007/s002270050563

Lavorel, S., Grigulis, K., Lamarque, P., Colace, M.-P., Garden, D., Girel, J., et al. (2011). Using plant functional traits to understand the landscape distribution of multiple ecosystem services. J. Ecol. 99, 135–147. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2745.2010.01753.x

Le Moigne, F. A. C., Poulton, A. J., Henson, S. A., Daniels, C. J., Fragoso, G. M., Mitchell, E., et al. (2015). Carbon export efficiency and phytoplankton community composition in the Atlantic sector of the Arctic Ocean. J. Geophys. Res. Ocean. 120, 3896–3912. doi: 10.1002/2015JC010700

Le Quere, C., Harrison, S. P., Colin Prentice, I., Buitenhuis, E. T., Aumont, O., Bopp, L., et al. (2005). Ecosystem dynamics based on plankton functional types for global ocean biogeochemistry models. Glob. Change Biol. 11, 2016–2040. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2486.2005.1004.x

Leonilde, R., Elena, L., Elena, S., Francesco, C., and Alberto, B. (2017). Individual trait variation in phytoplankton communities across multiple spatial scales. J. Plankton Res. 39, 577–588. doi: 10.1093/plankt/fbx001

Leps, J., De Bello, F., Lavorel, S., and Berman, S. (2006). Quantifying and interpreting functional diversity of natural communities: practical considerations matter. Preslia 78, 481–501.

Leventer, A., and Dunbar, R. B. (1996). Factors influencing the distribution of diatoms and other algae in the Ross Sea. J. Geophys. Res. Ocean 101, 18489–18500. doi: 10.1029/96JC00204

Li, W. K. W., and Harrison, W. G. (2001). Chlorophyll, bacteria and picophytoplankton in ecological provinces of the North Atlantic. Deep Res. Part II Top. Stud. Oceanogr. 48, 2271–2293. doi: 10.1016/S0967-0645(00)00180-6

Ligowski, R., Jordan, R. W., and Assmy, P. (2012). Morphological adaptation of a planktonic diatom to growth in Antarctic sea ice. Mar. Biol. 159, 817–827. doi: 10.1007/s00227-011-1857-6

Litchman, E., and Klausmeier, C. A. (2008). Trait-based community ecology of phytoplankton. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 39, 615–639. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.39.110707.173549

Litchman, E., Klausmeier, C. A., Schofield, O. M., and Falkowski, P. G. (2007). The role of functional traits and trade-offs in structuring phytoplankton communities: Scaling from cellular to ecosystem level. Ecol. Lett. 10, 1170–1181. doi: 10.1111/j.1461-0248.2007.01117.x

Malviya, S., Scalco, E., Audic, S., Vincent, F., Veluchamy, A., Poulain, J., et al. (2016). Insights into global diatom distribution and diversity in the world's ocean. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 113, E1516–E1525. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1509523113

Margalef, R. (1978). Life-forms of phytoplankton as survival alternatives in an unstable environment. Oceanol. Acta 1, 493–509.

McGill, B., Enquist, B., Weiher, E., and Westoby, M. (2006). Rebuilding community ecology from functional traits. Trends Ecol. Evol. 21, 178–185. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2006.02.002

Mock, T., and Junge, K. (2007). “Psychrophilic diatoms: mechanism for survival in freeze-thaw cycles,” in Algae and Cyanobacteria in Extreme Environments, ed J. Seckbach (New York, NY: Springer), 345–364.

Mock, T., Otillar, R. P., Strauss, J., McMullan, M., Paajanen, P., Schmutz, J., et al. (2017). Evolutionary genomics of the cold-adapted diatom Fragilariopsis cylindrus. Nature 541, 536–540. doi: 10.1038/nature20803

Nguyen, H., Karp-Boss, L., Jumars, P. A., and Fauci, L. (2011). Hydrodynamic effects of spines: a different spin. Limnol. Oceanogr. Fluids Environ. 1, 110–119. doi: 10.1215/21573698-1303444

Oku, O., and Kamatani, A. (1995). Resting spore formation and phosphorus composition of the marine diatom Chaetoceros pseudocurvisetus under various nutrient conditions. Mar. Biol. 393–399.

Oku, O., and Kamatani, A. (1999). Resting spore formation and biochemical composition of the marine planktonic diatom Chaetoceros pseudocurvisetus in culture: ecological significance of decreased nucleotide content and activation of the xanthophyll cycle by resting spore formation. Mar. Biol. 135, 425–436.

Olsen, L. M., Laney, S. R., Duarte, P., Kauko, H. M., Fernández-Méndez, M., Mundy, C. J., et al. (2017). The seeding of ice algal blooms in Arctic pack ice: the multiyear ice seed repository hypothesis. J. Geophys. Res. Biogeosci. 122, 1–20. doi: 10.1002/2016JG003668

Paganelli, D., Marchini, A., and Occhipinti-Ambrogi, A. (2012). Functional structure of marine benthic assemblages using biological traits analysis (BTA): a study along the Emilia-Romagna coastline (Italy, North-West Adriatic Sea). Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 96, 245–256. doi: 10.1016/j.ecss.2011.11.014

Pahlow, M., Riebesell, U., and Wolf-Gladrow, D. A. (1997). Impact of cell shape and chain formation on nutrient acquisition by marine diatoms. Limnol. Oceanogr. 42, 1660–1672. doi: 10.4319/lo.1997.42.8.1660

Passy, S. I. (2002). Environmental randomness underlies morphological complexity of colonial diatoms. Funct. Ecol. 16, 690–695. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2435.2002.00671.x

Petrou, K., Hill, R., Brown, C. M., Campbell, D. A., Doblin, M. A., and Ralph, P. J. (2010). Rapid photoprotection in sea-ice diatoms from the East Antarctic pack ice. Limnol. Oceanogr. 55, 1400–1407. doi: 10.4319/lo.2010.55.3.1400

Platt, T., Bouman, H., Devred, E., Fuentes-Yaco, C., and Sathyendranath, S. (2005). Physical forcing and phytoplankton distributions. Sci. Mar. 69, 55–73. doi: 10.3989/scimar.2005.69s155

Raymond, J. A., and Kim, H. J. (2012). Possible role of horizontal gene transfer in the colonization of sea ice by algae. PLoS ONE 7:e35968. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0035968

Reid, P. C., Johns, D. G., Edwards, M., Starr, M., Poulin, M., and Snoeijs, P. (2007). A biological consequence of reducing Arctic ice cover: arrival of the Pacific diatom Neodenticula seminae in the North Atlantic for the first time in 800 000 years. Glob. Chang. Biol. 13, 1910–1921. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2486.2007.01413.x

Riaux-Gobin, C., Poulin, M., Dieckmann, G., Labrune, C., and Vétion, G. (2011). Spring phytoplankton onset after the ice break-up and sea-ice signature (Adélie Land, East Antarctica). Polar Res. 30, 1–11. doi: 10.3402/polar.v30i0.5910

Rytter Hasle, G. (1976). The biogeography of some marine planktonic diatoms. Deep Sea Res. Oceanogr. Abstr. 23, 319–338. doi: 10.1016/0011-7471(76)90873-1

Sackett, O., Petrou, K., Reedy, B., De Grazia, A., Hill, R., Doblin, M., et al. (2013). Phenotypic plasticity of southern ocean diatoms: key to success in the sea ice habitat? PLoS ONE 8:e81185. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0081185

Sathyendranath, S., Longhurst, A., Caverhill, C. M., and Platt, T. (1995). Regionally and seasonally differentiated primary production in the North Atlantic. Deep Res. 42, 1773–1802.

Sathyendranath, S., Stuart, V., Nair, A., Oka, K., Nakane, T., Bouman, H., et al. (2009). Carbon-to-chlorophyll ratio and growth rate of phytoplankton in the sea. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 383, 73–84. doi: 10.3354/meps07998

Schwaderer, A. S., Yoshiyama, K., de Tezanos Pinto, P., Swenson, N. G., Klausmeier, C. A., and Litchman, E. (2011). Eco-evolutionary differences in light utilization traits and distributions of freshwater phytoplankton. Limnol. Oceanogr. 56, 589–598. doi: 10.4319/lo.2011.56.2.0589

Smetacek, V. S. (1985). Role of sinking in diatom life-hystory: ecological, evolutionary and geological significance. Mar. Biol. 84, 239–251. doi: 10.1007/BF00392493

Smith, W. O., and Nelson, D. M. (1985). Phytoplankton bloom produced by a receding ice edge in the Ross Sea: spatial coherence with the density field. Science 227, 163–166.

Straneo, F., and Saucier, F. (2008). The outflow from Hudson Strait and its contribution to the Labrador Current. Deep Sea Res. Part I Oceanogr. Res. Pap. 55, 926–946. doi: 10.1016/j.dsr.2008.03.012

Sugie, K., and Kuma, K. (2008). Resting spore formation in the marine diatom Thalassiosira nordenskioeldii under iron- and nitrogen-limited conditions. J. Plankton Res. 30, 1245–1255. doi: 10.1093/plankt/fbn080

Syvertsen, E. E. (1991). Ice algae in the Barents Sea: types of assemblages, origin, fate and role in the ice-edge phytoplankton bloom. Polar Res. 10, 277–288.

Thomas, M. K., Kremer, C. T., Klausmeier, C. A, and Litchman, E. (2012). A global pattern of thermal adaptation in marine phytoplankton. Science 338, 1085–1088. doi: 10.1126/science.1224836

Tortell, P. D., DiTullio, G. R., Sigman, D. M., and Morel, F. M. M. (2002). CO2 effects on taxonomic composition and nutrient utilization in an Equatorial Pacific phytoplankton assemblage. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 236, 37–43. doi: 10.3354/meps236037

Tréguer, P., Bowler, C., Moriceau, B., Dutkiewicz, S., Gehlen, M., Aumont, O., et al. (2018). Influence of diatom diversity on the ocean biological carbon pump. Nat. Geosci. 11, 27–37. doi: 10.1038/s41561-017-0028-x

Tsukazaki, C., Ishii, K. I., Saito, R., Matsuno, K., Yamaguchi, A., and Imai, I. (2013). Distribution of viable diatom resting stage cells in bottom sediments of the eastern Bering Sea shelf. Deep Res. Part II Top. Stud. Oceanogr. 94, 22–30. doi: 10.1016/j.dsr2.2013.03.020

Uhlig, C., Kilpert, F., Frickenhaus, S., Kegel, J. U., Krell, A., Mock, T., et al. (2015). In situ expression of eukaryotic ice-binding proteins in microbial communities of Arctic and Antarctic sea ice. ISME J. 9, 2537–2540. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2015.43

Violle, C., Navas, M.-L., Vile, D., Kazakou, E., Fortunel, C., Hummel, I., et al. (2007). Let the concept of trait be functional! Oikos 116, 882–892. doi: 10.1111/j.2007.0030-1299.15559.x

von Quillfeldt, C. H. (2001). Identification of some easily confused common diatom species in Arctic Spring blooms. Bot. Mar. 44, 375–389. doi: 10.1515/BOT.2001.048

Wang, M., and Overland, J. E. (2012). A sea ice free summer Arctic within 30 years: An update from CMIP5 models. Geophys. Res. Lett. 39, 2–6. doi: 10.1029/2012GL052868

Weithoff, G. (2003). The concepts of “plant functional types” and “functional diversity” in lake phytoplankton - a new understanding of phytoplankton ecology? Freshw. Biol. 48, 1669–1675. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2427.2003.01116.x

Weller, R. A., and Plueddemann, A. J. (1996). Observations of the vertical structure of the oceanic boundary layer. J. Geophys. Res. 101, 8789–8806.

Westoby, M., and Wright, I. J. (2006). Land-plant ecology on the basis of functional traits. Trends Ecol. Evol. 21, 261–268. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2006.02.004

Woods, S., and Villareal, T. A. (2008). Intracellular ion concentrations and cell sap density in positively buoyant oceanic phytoplankton. Nov. Hedwigia Beiheft 133, 131–145.

Wu, Y., Peterson, I. K., Tang, C. C. L., Platt, T., Sathyendranath, S., and Fuentes-Yaco, C. (2007). The impact of sea ice on the initiation of the spring bloom on the newfoundland and labrador shelves. J. Plankton Res. 29, 509–514. doi: 10.1093/plankt/fbm035

Yankovsky, A. E., and Yashayaev, I. (2014). Surface buoyant plumes from melting icebergs in the Labrador Sea. Deep Sea Res. Part I Oceanogr. Res. Pap. 91, 1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.dsr.2014.05.014

Yashayaev, I. (2007). Hydrographic changes in the Labrador Sea, 1960-2005. Prog. Oceanogr. 73, 242–276. doi: 10.1016/j.pocean.2007.04.015

Yashayaev, I., and Loder, J. W. (2016). Recurrent replenishment of Labrador Sea Water and associated decadal-scale variability. J. Geophys. Res. Ocean. 121, 8095–8114. doi: 10.1002/2016JC012046

Yashayaev, I., and Loder, J. W. (2017). Further intensification of deep convection in the Labrador Sea in 2016. Geophys. Res. Lett. 44, 1429–1438. doi: 10.1002/2016GL071668

Yashayaev, I., Seidov, D., and Demirov, E. (2015). A new collective view of oceanography of the Arctic and North Atlantic basins. Prog. Oceanogr. 132, 1–21. doi: 10.1016/j.pocean.2014.12.012

Yebra, L., Harris, R. P., Head, E. J. H., Yashayaev, I., Harris, L. R., and Hirst, A. G. (2009). Mesoscale physical variability affects zooplankton production in the Labrador Sea. Deep Sea Res. Part I Oceanogr. Res. Pap. 56, 703–715. doi: 10.1016/j.dsr.2008.11.008

Yool, A., Popova, E. E., and Coward, A. C. (2015). Future change in ocean productivity: is the Arctic the new Atlantic? J. Geophys. Res. Ocean. 120, 7771–7790. doi: 10.1002/2015JC011167

Zhai, L., Platt, T., Tang, C., Sathyendranath, S., and Walne, A. (2013). The response of phytoplankton to climate variability associated with the North Atlantic oscillation. Deep Sea Res. Part II Top. Stud. Oceanogr. 93, 159–168. doi: 10.1016/j.dsr2.2013.04.009

Zhang, Q., Gradinger, R., and Spindler, M. (1998). Dark survival of marine microalgae in the high arctic (Greenland Sea). Polarforschung 65, 111–116.

Keywords: marine diatom, biogeography, trait-based analyses, Arctic, Atlantic

Citation: Fragoso GM, Poulton AJ, Yashayaev IM, Head EJH, Johnsen G and Purdie DA (2018) Diatom Biogeography From the Labrador Sea Revealed Through a Trait-Based Approach. Front. Mar. Sci. 5:297. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2018.00297

Received: 28 February 2018; Accepted: 06 August 2018;

Published: 05 September 2018.

Edited by:

Senjie Lin, University of Connecticut, United StatesReviewed by:

Xin Lin, Xiamen University, ChinaDongyan Liu, State Key Laboratory of Estuarine and Coastal Research (ECNU), China

Copyright © 2018 Fragoso, Poulton, Yashayaev, Head, Johnsen and Purdie. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Glaucia M. Fragoso, Z2xhdWNpYS5tLmZyYWdvc29AbnRudS5ubw==

†Present Address: Glaucia M. Fragoso, Trondheim Biological Station, Dept. Biology, Norwegian University of Science and Technology, Trondheim, Norway

Alex J. Poulton, The Lyell Centre for Earth and Marine Science and Technology, Heriot-Watt University, Edinburgh, United Kingdom

Glaucia M. Fragoso

Glaucia M. Fragoso Alex J. Poulton

Alex J. Poulton Igor M. Yashayaev3

Igor M. Yashayaev3 Geir Johnsen

Geir Johnsen Duncan A. Purdie

Duncan A. Purdie