95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Immunol. , 02 October 2020

Sec. Nutritional Immunology

Volume 11 - 2020 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2020.575173

Previous studies have suggested that the Lactobacillus plantarum bacteria strain could be effective in ulcerative colitis (UC) management. However, its effects are strain-specific and the related mechanisms for its attenuating effects on UC remain unclear. This study aimed to elucidate the underlying mechanisms for the protective effect of L. plantarum on UC. Firstly, 15 L. plantarum strains were screened for potential probiotic characteristics with good tolerance to simulated human gastrointestinal transit and adhesion. Secondly, the inflammatory response of selected strains to the Caco-2 cells induced by lipopolysaccharide (LPS) was measured. Finally, an in vivo mouse model induced by dextran sulfate sodium (DSS) was used to assess the beneficial effects and likely action mechanisms the successfully screened in vitro strain, L. plantarum L15. In vitro results showed that L. plantarum L15 possessed the highest gastrointestinal transit tolerance, adhesion and reduction of pro-inflammatory abilities compared to the other screened strains. In vivo, high dose of L. plantarum L15 supplementation increased the body weight, colon length and anti-inflammatory cytokine production. Pro-inflammatory cytokine production, disease activity index (DAI) levels and myeloperoxidase (MPO) parameters decreased using this strain. In addition, L. plantarum L15 alleviated the histopathological changes in colon, modulated the gut microbiota, and decreased LPS secretion. The activities of this strain down-regulated the expression of TLR4 and MyD88 genes as well as genes associated with NF-κB signaling pathway. Our findings present L. plantarum L15 as a new probiotic, with promising application for UC management.

Ulcerative colitis (UC) is of increasing concern worldwide, with inflammatory characteristics between the rectum and colon sections of sufferers (1). Although the exact causative factors are still unclear at present, several hypotheses have linked UC to genetic variations, environmental changes, and immunomodulatory factors (2). Conventionally, UC can be treated with a number of medications, including 5-aminosalicylic acid drugs, steroids, and immunosuppressants. These therapies have a number of drawbacks, ranging from unpleasant reactions to high cost especially for patients who may need them for a long time frame (3). Therefore, it becomes important to find a healthy and effective way to manage UC.

Microbes in the human intestinal system give tremendous metabolic and health-related support to the body, thus leading to the postulation that the gut microbiota is another body “organ” (4). Cumulative studies on the gut microbiota have informed a research position that this “organ” could be a target for therapeutic interventions as it has been linked with health and well-being (5, 6). In addition, next-generation sequence (NGS) techniques and in vivo reports have recently demonstrated that imbalances in microbiota profiles have been found in highly prevalent diseases, such as inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD), irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) or colorectal cancer, among others (6–9). Furthermore, the decrease in the relative abundance of healthy gut microbiome phyla like Firmicutes and a corresponding increases in Proteobacteria has been observed in both Crohn's Disease (CD) and UC gut microbiomes (10–12). Probiotic bacterial strains, mainly of the Lactobacillus genus, have been used to treat gut dysbiosis incidences and as such, can be a possible alternative in UC treatment. Some species from the Lactobacillus genera can regulate cytokine activities and improve integrity of the gut barrier (13). Furthermore, some species have been reported to have UC-alleviating effects by reducing the production of pro-inflammatory factors, and restoring the balance of the gut microbiota (14–16).

A number of studies involving different L. plantarum strains have demonstrated in vitro and in vivo beneficial effects in UC therapy through normalizing disease activity index (DAI) score, significantly suppressing the expression of pro-inflammatory factors (TNF-α and IL-6), modulating gut microbiota, halting intestinal cell apoptosis as well as inhibiting activation of the NF-κB signaling pathway (17–20). Thus, L. plantarum supplementation could be a fascinating strategy for the patients suffering from UC. However, there is little information about the UC-alleviating mechanisms of L. plantarum strains. In the present study, we selected a potential probiotic L. plantarum L15 strain with good gastrointestinal transit tolerance, adhesion, and reduction of pro-inflammatory abilities and further investigated the effect and the mechanism of L. plantarum L15 supplementation in an in vivo dextran sulfate sodium-induced colitis model, which has been widely used as a representative UC model, because of its simplicity and many similarities with human UC condition (21). DSS is a highly water-soluble compound which is toxic for the colonic epithelial cells and causes defects in the epithelial barrier integrity, resulting in increased colonic epithelial permeability (22). The aim of this study was to determine whether L. plantarum L15 supplementation can ameliorate DSS-induced UC by inhibiting LPS-mediated NF-κB activation and regulate DSS-induced gut microbiota dysbiosis. It is anticipated that this study will enhance our understanding regarding the use of L. plantarum L15 as a potential probiotic against UC in functional foods and supplements formulation.

A total of 15 Lactobacillus plantarum strains (L11, L12, L13, L14, L15, L16, L17, L18, L19, L110, L111, L112, L113, L114, and L115) were isolated from yak yogurt in Gansu Province, China and identified by 16S rDNA similarity analysis. All strains were deposited in the Key Laboratory of Dairy Science (KLDS) of the Northeast Agricultural University (NEAU), Ministry of Education, China. Strains were anaerobically incubated in deMan Rogosa and Sharpe (MRS) broth (Hopebio Company, China) at 37°C for 24 h and sub-cultured twice prior to the experiment.

The tolerance to simulated human GIT of the 15 Lactobacillus strains was evaluated according to the method described by Maragkoudakis et al. (23). Briefly, the cells were harvested by centrifugation at 10,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C after incubation at 37°C for 18 h. Then they were adjusted to 109 CFU/mL and subjected in simulated gastric juice for 3 h and small intestinal juice for 4 h. The microorganisms were harvested by centrifugation at 10,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C and transferred from simulated gastric juice to simulated small intestinal juice. The simulated gastric juice was prepared by supplementing pepsin (1:10,000, P8160, Solarbio Co., China) to normal saline (pH 3.0) at a concentration of 3 g/L. The simulated intestinal juice was prepared by adding 1 g/L trypsin (1:250, T8150, Solarbio Co., China) to normal saline (pH 8.0) to a concentration of 3 g/L bile salt (LP0055, Thermo Fisher Scientific Co., UK). All the prepared juices were filter-sterilized using 0.22 μm membrane filters. Viable cells were counted by plate colony counting method at 0 (N0) and 7 h (N1) to determine tolerance levels after incubation on MRS agar at 37°C for 48 h. The experiment was repeated in triplicate. The survival rate was calculated as follows:

Caco-2 cells are purchased from the Cell Bank of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (Shanghai, China). They were then grown at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere of 95% air and 5% CO2. The cells were cultured in high-glucose Dulbecco's Modified Eagle's Medium (DMEM, Gibco, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Gibco, USA) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (Gibco, USA).

The adhesive ability of the strains using Caco-2 cells were determined as previously described with slight modifications (24). The Caco-2 cells were seeded at 105 cells/well in a 12-well-plate and incubated at 37°C for 24 h. One day before the experiments, medium was replaced by DMEM (without penicillin/streptomycin). The lactobacilli cells were washed with phosphate buffer saline (PBS) thrice, and the cells were collected by centrifugation at 10,000 × g for 10 min followed by suspension with no glucose, no penicillin/streptomycin DMEM, adjusted to 108 CFU (V0), and added in the wells. After being incubated for 2 h, the monolayer was washed three times with PBS to remove free and unattached bacterial cells. After that, 250 μL of 0.25% trypsin-EDTA (Gibco, USA) was added and incubated for 10 min, then the reaction was terminated using 250 μL of fetal bovine serum. Mixtures in each well was collected and used to evaluate the viable count of the strain (V1). The experiment was repeated in triplicate. Adhesion assays were performed in triplicate. The adhesive ability was expressed as:

The induction of inflammatory response in Caco-2 cells was performed following a previously described procedure (25). 250 ng/μl of lipopolysaccharide (LPS) solution (Sigma Chemicals, Bangalore) was used to initiate Caco-2 cells inflammatory response. Cells cultures with LPS were kept in a 5% CO2 incubator for 3 h. Cell cultures without LPS stimulation served as controls. After 4 h of treatment with 108 CFU/mL cells (final concentration) of each Lactobacillus species. The treated Caco-2 cells along with strains were washed twice with PBS (pH 7.0) and the treated cells were detached from the tissue culture plates. Total RNA of Caco-2 cells was extracted using Trizol reagent (Life Technologies, USA). cDNA was obtained by reverse transcription with a PrimeScript RT reagent Kit with gDNA Eraser (Takara, Japan) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The mRNA expression of genes was performed by ABI 7500 fast real time PCR system (Applied Biosystems, USA) using SYBR Premix Ex Taq (Takara, Japan). The primers (Comate Bioscience Co., Ltd, China) used in this study are shown in Supplementary Table 1. The housekeeping gene (GAPDH) was used for normalization and data was analyzed by 2−ΔΔCt method. The experiment was performed in six replications.

A total of 60 BALB/c mice (6 weeks old) were provided by the Vital River Laboratory Animal Technology Company (Beijing, China) and housed in a room under controlled environmental conditions at 22 ± 2°C, a relatively humidity of 40–60% and with a 12-h light/dark cycle. All conducted animal experiments in this study were approved by the Northeast Agricultural University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (Approval No: SRM-10).

The mice were placed in plastic cages for 1 week in order to acclimatize prior to the experiments and provided with normal chow diet and water ad libitum. They were randomly assigned to 5 groups (n = 12). Firstly, the control group was given distilled water, the DDS-induced colitis group (DSS) was received 3.5% (w/v) DSS (36–50 kDa, MP Biomedicals Ltd., Santa Ana, U.S.A.) in drinking water for 7 days. Then, the low-dose (LD) group and the high-dose (HD) group were given 1 × 109 or 1 × 1010 CFU/mL L. plantarum L15 (1 mL/100 g body weight) (26, 27) by oral gavage once daily for a period of 28 days, respectively. Bacteria were harvested by centrifugation at 5,000 × g for 10 min. Cell pellets were then washed twice with sterile normal saline (9 g of Nacl per liter (0.9%) solution) and re-suspended at the concentration (1 × 109 or 1 × 1010 CFU/mL) in sterile normal saline. The control and DSS groups were given equal volumes of sterile normal saline as no-treatment control and negative control, respectively. The positive control group (PC) was administered at a concentration of 30 mg/mL of salicylazosulfapyridine with the same volume of sterile normal saline (28).

During the experiment, the body weight, stool consistency, and blood in the stool of mice were recorded. Disease activity index (DAI) was scored based on an average score of body weight change, stool consistency, and hemoccult bleeding from a previous scoring system (Supplementary Table 2) (29, 30). The measurement was conducted in six replications.

Histopathologic analysis was performed as described in the previous research (19). Briefly, To observe colon histopathological changes after different treatments, colon samples were fixed in 10%-buffered formalin solution, dehydrated in ethanol, embedded in paraffin, cut into 5 μm sections. They were then stained using standard hematoxylin-eosin (HE) and then observed under a light microscope. Colon samples were observed at ×200 and ×400 magnification, and the histopathology changes were determined using a scoring system taking into account the severity of inflammation (from 0 to 3 as the maximum score), crypt damage (from 0 to 5 as the maximum score) and ulcerations (from 0 to 3 as the maximum score) as previously described (31). The experiment was performed in six replications.

The colon samples were weighed and homogenized in nine volumes of ice-cooled PBS (pH 7.4), centrifuged at 5,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C to collect the supernatant, which was used for biochemical analyses. In this study, myeloperoxidase (MPO), superoxide dismutase (SOD), glutathione (GSH), and malondialdehyde (MDA) levels were determined using commercial detection kits (Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute) following the manufacturer's protocol. Commercial enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kits (Mei Lian Biotechnology Co., Ltd. Shanghai, China) were used to evaluate the concentrations of tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), interleukin-1β (IL-1β), IL-10, and IL-12. Finally, fecal and serum LPS contents were evaluated with the Limulus amebocyte lysate (LAL) assay kit (32). The measurement was conducted in six replications.

Bacterial DNA in the cecal contents of the control, DSS and HD groups were extracted using a QIAamp DNA stool mini kit (Qiagen, Dusseldorf, Germany) following the manufacturer's instructions. The V3-V4 region of the 16S rDNA were selected for generating amplicons by PCR technique. The primers were as follows: (forward primers: 5′-CCTACGGGNGGCWGCAG-3′, and reverse primers: 5′-GACTACHVGGGTATCTAATCC-3′). The PCR products were purified with QIAquick PCR Purification Kit (Qiagen, Dusseldorf, Germany), and quantified using a Qubit 2.0 Fluorometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, USA). Next-generation 16S rDNA sequencing was performed on an Illumina Miseq (Illumina, Santiago, USA). In all, 1,613,856 raw reads were obtained from cecal samples (Supplementary Table 3). The obtained data were merged using FLASH software V1.2.7 (33) and filtered with QIIME software V1.7.0 (34, 35). The chimera sequences were discarded by using the UCHIME algorithm to obtain the high-quality clean tags (36). The tags were clustered into distinct operational taxonomic units (OTUs) using Uparse software with a 97% sequence identity (37). They were annotated to taxonomic information by comparing to the GreenGene database using PyNAST software V1.2 (38). The phylogenetic tree was generated using MUSCLE software. OTUs abundance information was normalized using a standard of sequence number corresponding to the sample with the least sequences. QIIME software V1.7.0 were used to analyze α-diversity and β-diversity. The abundances of functional category of LPS biosynthesis in the KEGG pathway was predicted by Phylogenetic Investigation of Communities by Reconstruction of Unobserved States (PICRUSt) based on the 16S rRNA sequences (39). The measurement was conducted in five replications.

Total RNA of colon tissue was extracted using Trizol reagent (Life Technologies, USA). The primers (Comate Bioscience Co., Ltd, China) used in this study are shown in Supplementary Table 4. Analyses using the qRT-PCR technique was performed as earlier described in this research, and the housekeeping gene (β-actin) was used for normalization. The western blotting technique was used to detect proteins involved in the colonic NF-κB signaling pathway as previously reported with slight modifications (20). Colon tissue samples were homogenized, centrifuged and the obtained supernatant analyzed by electrophoresis on 8–10% sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel. Samples were then placed on a nitrocellulose membrane to measure the expressions of NF-κB p65, p-p65, IκB, p-IκB, and β-actin. The measurement was conducted in six replications.

All values are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation (SD). All experiments were performed at least three times using independent assays. The statistical significance of data comparisons was determined using one-way analysis of variance, followed by Duncan's multiple range test of the statistical software package Social Science version 22.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, U.S.A.). Values of P < 0.05 indicated a significant difference.

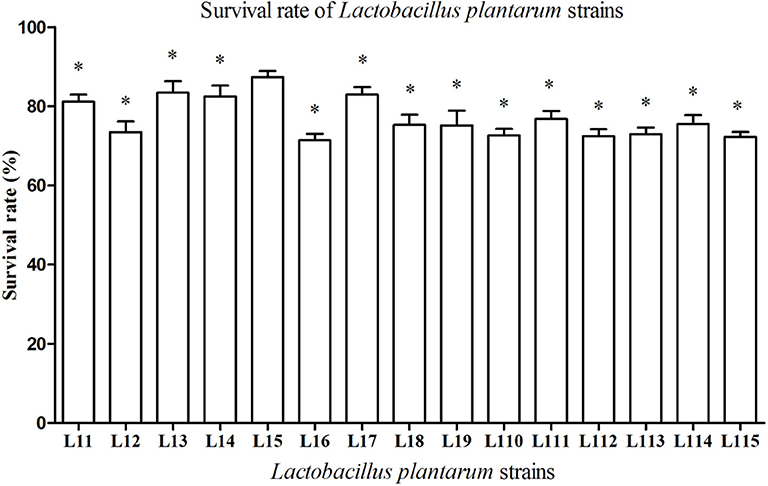

Simulated gastrointestinal juices tolerance pattern of 15 strains was shown in Figure 1. All Lactobacillus strains are able to survive in the simulated gastrointestinal tract for 7 h and the survival rates ranged from 71.40 to 87.36%. It was also observed that L. plantarum L15 exhibited the highest survival rate with 87.36% (P < 0.05), following by L. plantarum L13, L17, L14, and L11.

Figure 1. Tolerance of Lactobacillus plantarum strains to simulated gastrointestinal juices. Values are mean ± SD (n = 3 independent experiment). *P < 0.05: significantly different compared with L. plantarum L15 by using one-way analysis of variance, followed by Duncan's test.

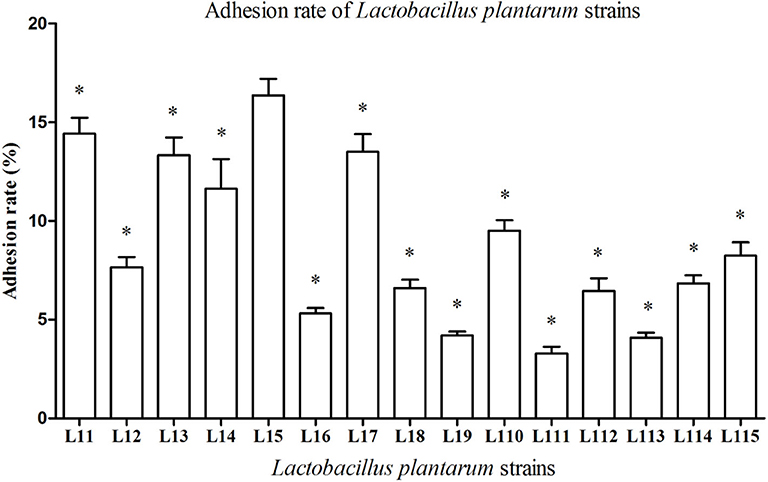

All Lactobacillus strains showed adhesion to the Caco-2 cells, with adhesion rate ranging from 3.28 to 16.37% (Figure 2). The adhesion rate of L. plantarum L15 was markedly higher than other strains (P < 0.05), followed by L. plantarum L11, L17, L13, and L14. Therefore, L. plantarum L15, L11, L13, L14, and L17 strains had good in vitro probiotic properties, including high GIT tolerance and adhesion ability. They were selected to test the protective effect on the inflammatory activities induced by LPS in Caco-2 cells.

Figure 2. Adhesion rate of Lactobacillus plantarum strains to Caco-2 cells. Values are mean ± SD (n = 3 independent experiment). *P < 0.05: significantly different compared with L. plantarum L15 by using one-way analysis of variance, followed by Duncan's test.

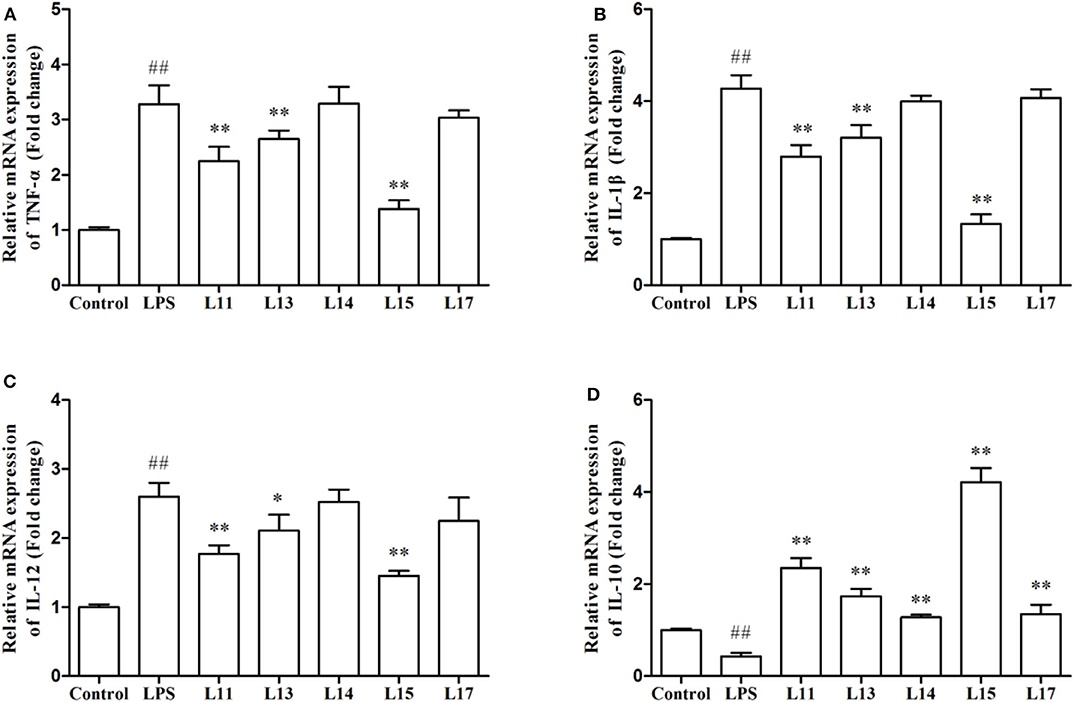

The immune factor responses when Caco-2 cells were first induced with LPS solution and then treated with the selected L. plantarum strains, were determined in the present research (Figure 3). LPS remarkably stimulated the expression of TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-12 genes, compared to the control (P < 0.01). After L. plantarum L15, L11, and L13 treatments, the expression levels of TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-12 were significantly reduced (P < 0.05), whereas there were no significant changes observed in the L. plantarum L14 and L17 treatments (P > 0.05). Although all L. plantarum strains up-regulated the expression level of IL-10. However, treatment with L. plantarum L15 showed the highest IL-10 increase, suggesting its strong anti-inflammatory activity. It was found that L. plantarum L15 had strong reduction of pro-inflammatory effect by down-regulating the pro-inflammatory cytokine expression but up-regulating the anti-inflammatory cytokine expression in the Caco-2 cells. Based on these in vitro screening procedures, L. plantarum L15 was selected to investigate its in vivo anti-UC characteristics.

Figure 3. Effect of Lactobacillus plantarum strains on the expression levels of cytokine genes in Caco-2 cells. (A) TNF-α; (B) IL-1β; (C) IL-12; and (D) IL-10. Control, normal control group; LPS, LPS-induced inflammation group; L11, LPS plus L. plantarum L11; L13, LPS plus L. plantarum L13; L14, LPS plus L. plantarum L14; L15, LPS plus L. plantarum L15; L17, LPS plus L. plantarum L17. Values are mean ± SD (n = 6 independent experiment). ##P < 0.01: significantly different compared with the control group. *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01: significantly different compared with the LPS group by using one-way analysis of variance, followed by Duncan's test.

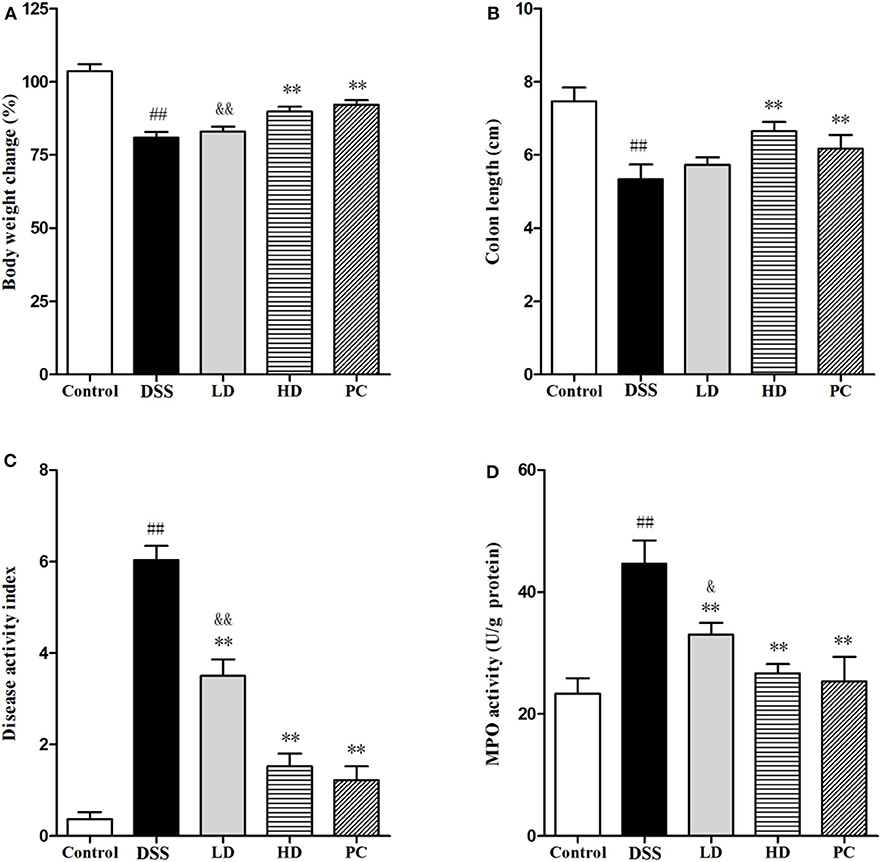

As shown in Figure 4, DSS exposure significantly decreased the body weight and colon length (P < 0.01), but significantly increased the DAI and MPO when compared with the control group (P < 0.05). In the LD group, only the DAI and MPO significantly were reversed (P < 0.01), whereas, no significant changes of the body weight and colon length were observed (P > 0.05). All four indexes were significantly ameliorated in the HD group (P < 0.01), which were not significantly different with the PC group (P > 0.05). These results indicated that the high dose of L. plantarum L15 supplementation could effectively restore physiological changes in mice treated with DSS.

Figure 4. Effects of L. plantarum L15 on DSS-induced colitis in mice. (A) Body weight change (%); (B) Colon length; (C) DAI score; and (D) MPO activity. Control, normal control group; DSS, dextran sulfate sodium-induced colitis group; LD, DSS plus low dose of L. plantarum L15 (1 × 109 CFU/mL, 1 mL/100 g body weight); HD, DSS plus high dose of L. plantarum L15 (1 × 1010 CFU/mL, 1 mL/100 g body weight). Values are mean ± SD (n = 6 independent experiment). ##P < 0.01: significantly different compared with the control group; **P < 0.01: significantly different compared with the DSS group by using one-way analysis of variance; &P < 0.05 and &&P < 0.01: significantly different compared with the PC group by using one-way analysis of variance, followed by Duncan's test.

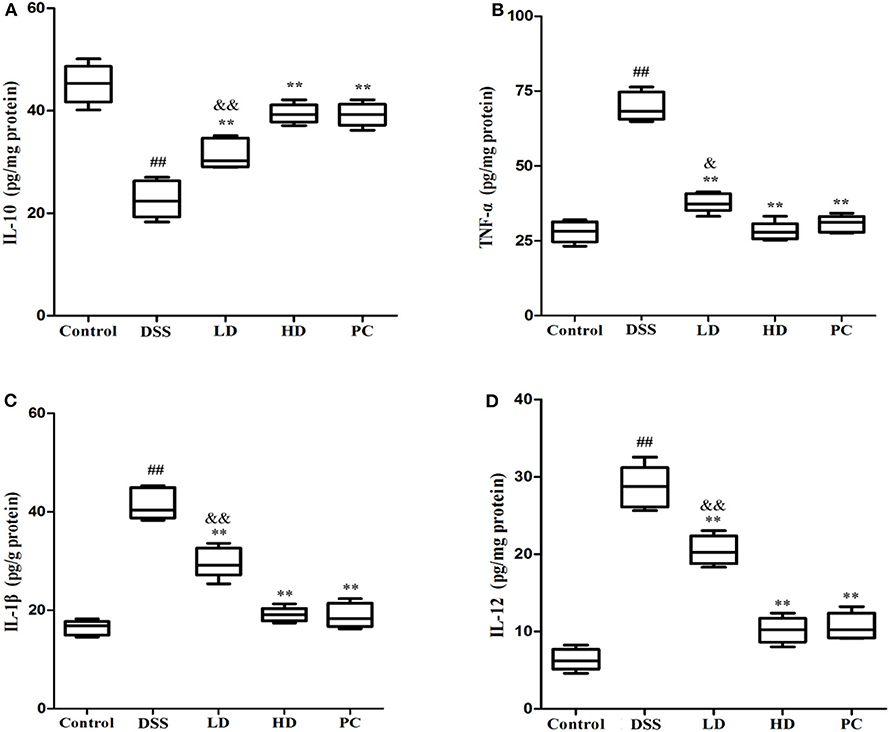

As shown in Figure 5, the IL-10 concentration in the DSS group was significantly lower than that in the control group, while the concentration of TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-12 was significantly increased (P < 0.01), implying that DSS administration could increase the secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokine with a corresponding decrease in anti-inflammatory cytokine levels. The IL-10 concentration was conspicuously increased compared with the DSS group (P < 0.01) after low and high doses of L. plantarum L15 supplementation. It was also observed that TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-12 were significantly decreased in these two supplementation groups compared to the DSS group (P < 0.01). More so, there were no significant differences of cytokine production between the HD and PC groups (P > 0.05). These results implied that high dose of L. plantarum L15 supplementation could more effectively alleviate UC by regulating Inflammatory cytokines.

Figure 5. Effects of L. plantarum L15 on cytokines production (protein level) in colon tissues from DSS-induced colitis in mice determing by ELISAs. (A) IL-10; (B) TNF-α; (C) IL-1β; and (D) IL-12. Control, normal control group; DSS, dextran sulfate sodium-induced colitis group; LD, DSS plus low dose of L. plantarum L15 (1 × 109 CFU/mL, 1 mL/100 g body weight); HD, DSS plus high dose of L. plantarum L15 (1 × 1010 CFU/mL, 1 mL/100 g body weight). Values are mean ± SD (n = 6 independent experiment). ##P < 0.01: significantly different compared with the control group; **P < 0.01: significantly different compared with the DSS group by using one-way analysis of variance; &P < 0.05 and &&P < 0.01: significantly different compared with the PC group by using one-way analysis of variance, followed by Duncan's test.

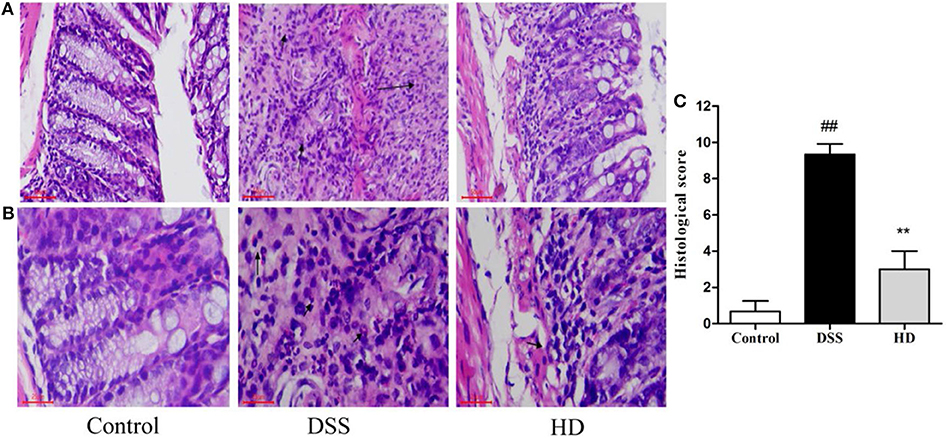

To observe the effect of L. plantarum L15 supplementation on histopathological changes of UC mice, the HE staining of colonic tissue was performed. As presented in Figures 6A,B, the colon epithelial cells of mice in the control group were arranged in order, and there were abundant goblet cells without inflammatory cell infiltration. In the DSS group, colon edema was severe, epithelial structure was damaged, most of goblet cells were absent, and a noticeably high number of inflammatory cells infiltration. Compared to the DSS group, high dose of L. plantarum L15 supplementation attenuated the extent and severity of lesions, improved the epithelium architecture and reduced inflammatory cell infiltration. As shown in Figure 6C, the score value of the DSS group was significantly higher than that of the control group. In contrast, the score value of the HD group was lower than that of the DSS group. These results implied that high dose of L. plantarum L15 can alleviate and repair injuries caused in colon tissues by DSS induction.

Figure 6. Effects of L. plantarum L15 on the colon histology. (A) Representative photomicrographs of colon histology (magnification 200×); (B) Representative photomicrographs of colon histology (magnification 400×) and (C) Associated histological scores. Control, normal control group; DSS, dextran sulfate sodium-induced colitis group; HD, DSS plus high dose of L. plantarum L15 (1 × 1010 CFU/mL, 1 mL/100 g body weight). Values are mean ± SD (n = 6 independent experiment). ##P < 0.01: significantly different compared with the control group; **P < 0.01: significantly different compared with the DSS group by using one-way analysis of variance, followed by Duncan's test.

Among the bacterial α-diversity, Chao 1, and Shannon indexes were used to estimate the richness and diversity of gut microbiota. As shown in Supplementary Figure 1A, the Chao 1 and Shannon indexes in the DSS group were significantly decreased when compared with the control group (P < 0.05). However, the two indexes in the HD group were significantly higher than that in the DSS group (P < 0.05). Among the bacterial β-diversity, the hierarchical clustering tree of weighted UniFrac distances showed that the HD group was grouped with the control group and then clustered with the DSS group (Supplementary Figure 1B). These findings indicated that high dose supplementation of L. plantarum L15 shifted the overall structure of the DSS mice gut microbiota to the control group.

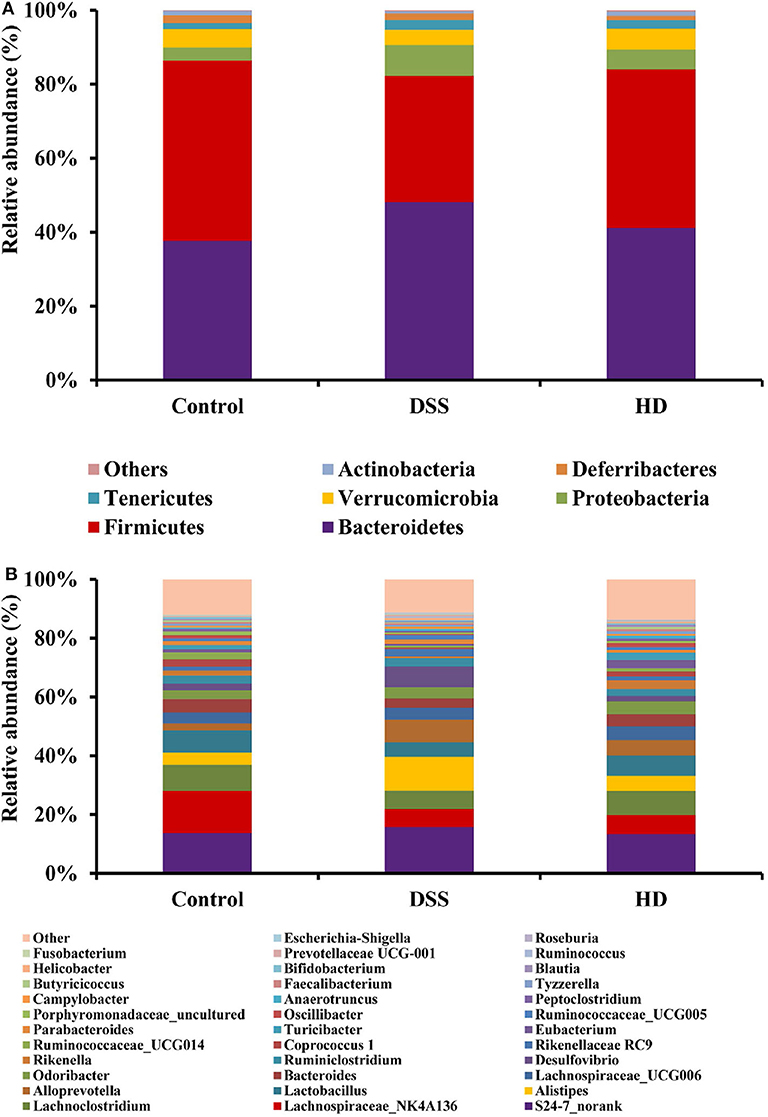

The gut microbiota composition at the phyla and genera levels in three groups (control, DSS, and HD) shown in Figure 7. It was observed that the relative abundances of Bacteroidetes and Proteobacteria increased in the DSS group compared to the control, but the relative abundances of Actinobacteria and Firmicutes decreased (Figure 7A). After high dose supplementation with L. plantarum L15, the Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes ratio, and abundances of Proteobacteria and Actinobacteria were restored, thus suggesting its efficacy. At the genus level (Figure 7B), the abundances of Lachnospiraceae_NK4A136 group, Lactobacillus, Turicibacter, Bacteroides, Butyricicoccus, Bifidobacterium and Faecalibacterium were reduced in the DSS group, confirming DSS induction. Interestingly, L. plantarum L15 supplementation normalized the disruptions in these genera. In addition, the relative abundances of other pathogenic genera such as Alistipes, Alloprevotella, Desulfovibrio, Blautia, Odoribacter, Helicobacter, Parabacteroides, Campylobacter, and Escherichia-Shigella increased in the DSS group, but inhibited by high doses of L. plantarum L15 supplementation.

Figure 7. Relative abundance of gut microbiota at the phylum level (A) and genus (B) levels in the feces of mice. Control, normal control group; DSS, dextran sulfate sodium-induced colitis group; HD, DSS plus high dose of L. plantarum L15 (1 × 1010 CFU/mL, 1 mL/100 g body weight). Values are mean (n = 5 independent experiment).

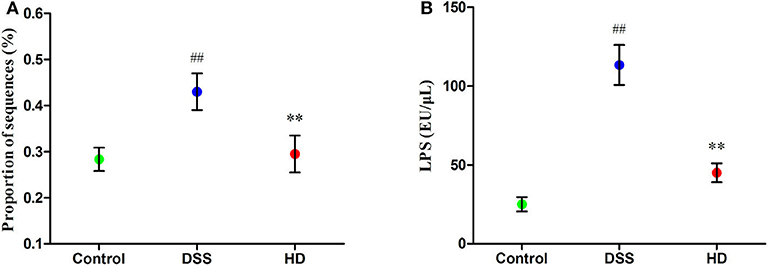

The abundances of functional category of LPS biosynthesis in the KEGG pathway was shown in Figure 8A. Compared to the control group, the microbial gene associated with LPS biosynthesis significantly increased in the DSS group (P < 0.01), but this pattern was reversed by L. plantarum L15 supplementation. As shown in Figure 8B, the concentration of LPS in the cecal contents in the HD group were significantly lower than that in the DSS group (P < 0.01).

Figure 8. Function of LPS biosynthesis inferred from gut microbiota by PICRUSt annotation based on 16S rRNA gene sequences (A) and the LPS level in the cecal contents (B). Control, normal control group; DSS, dextran sulfate sodium-induced colitis group; HD, DSS plus high dose of L. plantarum L15 (1 × 1010 CFU/mL, 1 mL/100 g body weight). Values are mean (n = 5 independent experiment). ##P < 0.01: significantly different compared with the control group; **P < 0.01: significantly different compared with the DSS group by using one-way analysis of variance, followed by Duncan's test.

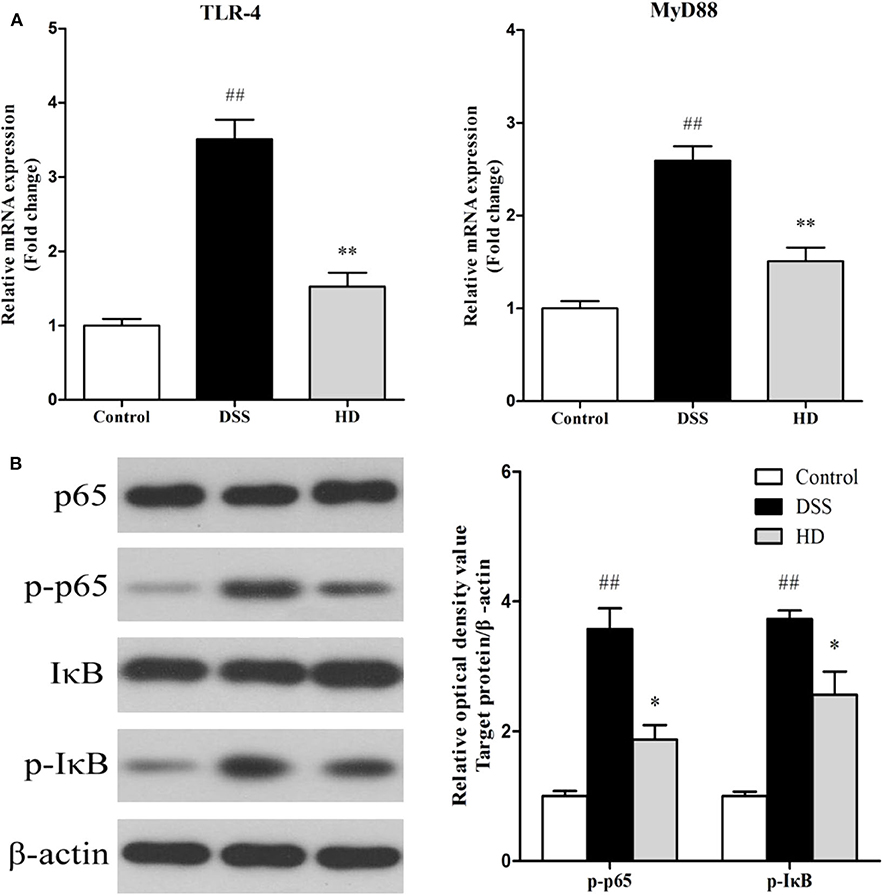

The effects of L. plantarum L15 supplementation on the colonic TLR4 and MyD88 expression genes at mRNA level are shown in Figure 9A. Compared with the control group, TLR4, and MyD88 genes in the DSS group were significantly (P < 0.01) up-regulated, while L. plantarum L15 administration significantly down-regulated their expression levels (P < 0.01), when compared with the DSS group. Expression of genes involved in NF-κB signaling pathway in the colonic tissue at protein level determined by western-blot are shown in Figure 9B. DSS induction resulted in a significant increase in the expression of p-p65 and p-IκB factors as compared to the control group (P < 0.01). Interestingly, L. plantarum L15 supplementation significantly reduced the expression of p-p65 and p-IκB (P < 0.05). These results indicated that L. plantarum L15 supplementation could attenuate chemical-induced colitis by DSS through inhibiting the TLR4-MyD88-NF-κB signaling pathways.

Figure 9. The mRNA levels of TLR4 and MyD88 (A) and the protein levels of NF-κB signaling pathway in colon tissue (B). Control, normal control group; DSS, dextran sulfate sodium-induced colitis group; HD, DSS plus high dose of L. plantarum L15 (1 × 1010 CFU/mL, 1 mL/100 g body weight). Values are mean (n = 6 independent experiment). ##P < 0.01: significantly different compared with the control group. *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01: significantly different compared with the DSS group by using one-way analysis of variance, followed by Duncan's test.

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), including ulcerative colitis (UC) and Crohn's Disease (CD), is a global health challenge that is currently on the rise (2, 40). According to several epidemiology and micro-ecology studies, findings suggest that its pathogenic mechanism is related to deregulation of the host immune response and intestinal micro-ecosystem (6). It is thus proposed by many researchers that improving the gut microbiota and boosting the immune response, can be safe and promising strategies for the patients suffering from UC (2).

Previous studies have indicated the possible link between activities of Lactobacillus strains and enhancement of host immunity. Generally, different Lactobacillus strains may exert positive or negative effects on the UC severity in vivo. This diversity is strain-specific and closely related to several key factors. GIT tolerance and Caco-2 cell adhesion characteristics are widely used in vitro screening procedure to ascertain potential probiotic strains with possible beneficial intestinal functions as they are associated with the survival of a strain and its colonization in the intestine (41). Furthermore, while good tolerance levels are indicative of the ecological resilience of a given strain (42), its adhesion ability can be a good predictor of immune modulation enhancement and maintenance gut barrier integrity (43). The present study selected potential probiotic strains from 15 L. plantarum strains in vitro based on these two procedures. Based on the in vitro results, L. plantarum L15 was selected for further investigations in vivo using a DSS-induced UC model.

DAI and MPO are widely used to evaluate UC condition (44, 45). DAI is composed of body weight change, diarrhea, and hematochezia, which are measured every day. It plays an important role in evaluating the clinical progression of UC (46). It has been reported that MPO is a simple, non-invasive, and relevant marker of UC activity (47). In present study, the DAI and MPO significantly increased in the DSS group, indicating that the UC model was successfully constructed. The two indexes were reversed by the high dose of L. plantarum L15 supplementation. These results indicated that L. plantarum L15 supplementation could effectively restore physiological changes in mice treated with DSS.

Cytokines are protein substances that mediate immunity and inflammation activities. One type of cytokine, the TNF-α has been linked with pro-inflammatory responses. Similarly, another category of cytokines secreted from macrophages, the IL-1β, is involved in pro-inflammatory regulations that facilitates UC progression (48). In addition, T and natural killer cells are mediated by the IL-12 cytokine, which in turn fuels TNF-α secretion (49). As reported previously, pro-inflammatory cytokine levels (TNF-α, IL-12, and IL-1β) in colonic tissues were elevated significantly by DSS exposure (50, 51). These cytokines have been inhibited by Lactobacillus species, endowing the latter with reduction of pro-inflammatory properties (52–54). Results from the current study showed that pro-inflammatory cytokine levels (TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-12) in the DSS group were significantly higher compared to the control group but these anomalies were also significantly reversed by high-dose administration of L. plantarum L15. Furthermore, the amounts of an anti-inflammatory cytokine, IL-10, was markedly increased by this probiotic supplementation. These observations posited that a high-dose administration of L. plantarum L15 had UC-alleviating effects and thus could be a potential candidate in UC therapy.

The gut ecosystem is a diverse collection of bacteria genera that play specific and inter-related roles in host immunity, disease prevention, and beneficial intestinal functions. This makes the gut microbiota a key research area in many intervention studies. It is no surprise therefore that an unstable gut ecology was previously linked with the onset of many diseases, including UC and CD (55, 56). Observations from the present study showed that the relative abundances of the Bacteriodetes and Proteobaceria phyla increased in the DSS group compared with the control group, agrees with previous reports (20).

At the genus level, the distribution varied in all studied groups. The relative abundances of Lachnospiraceae._NK4A136 group, Lactobacillus, Turicibacter, Bacteroides, Butyricicoccus, Bifidobacterium, and Faecalibacterium were reduced in DSS-induced mice but increased after high dose of L. plantarum L15 administration. The Lactobacillus genera is a well-known probiotic group with colitis-alleviating effects in in vivo mouse models (45, 57). Samples from IBD patients indicate that the relative abundance of the Butyricicoccus genera was reduced (58). This genera is known to improve colitis status by inhibiting the NF-κB transcription factor in lamina propria macrophages of UC patients (59, 60). Another genera, Bifidobacterium, is an extensively-used probiotic group and it was previously reported that its consumption could alleviate inflammations in mice intestine, thus inferring that it could play beneficial roles in UC management (61, 62). In addition to these, activities of the Faecalibacterium genera have been linked in intestinal health integrity and that the relative abundance of F. prausnitzii was significantly reduced according to an earlier study involving UC patients (10).

In contrast, up-regulation of some pathogenic genera like Alistipes, Alloprevotella, Desulfovibrio, Blautia, Odoribacter, Helicobacter, Parabacteroides, Campylobacter, and Escherichia-Shigella was noticed in the DSS group, which was suppressed by high-dose L. plantarum L15 administration. The Bacteroides, Alistipes, Parabacteroides and Alloprevotella genera belong to the Bacteroidetes phylum, and are known for LPS secretion (63). In addition, a previous research reported that two gastrointestinal pathogens, Helicobacter. pylori and Campylobacter jejuni not only belong to the epsilon-proteobacteria class, but also possess specific lipid A structures which implicates them in LPS-related infections. These researchers also reported that the proteobacterium pathogen, Desulfovubrio desulfuricans could secrete LPS, which could exacerbate UC and CD conditions (64). Furthermore, elevated E. coli levels have been reported in UC sufferers and in vivo mouse models (65). Cani et al. confirmed previous postulations by demonstrating that a significant portion of these gram-negative pathogenic bacteria membranes are composed of LPS, and this explains why they are endowed with the propensity for pro-inflammatory activities in the gastrointestinal tract and promote gut dysbiosis (66).

Previously, Ning et al. postulated that the TLR4 receptor is triggered by LPS activities, and that the former has been linked with low-grade chronic inflammatory diseases (67). Inflammatory cytokines secretion are activated by the TLR4/NF-κB complex, formed upon successful binding of the TLR4 receptor and LPS (68). The NF-κB transcription factor has been shown to activate key genes involved in pro-inflammatory cytokine production, which lower the body's defense system over time. These pathways and processes eventually contribute to UC onset (69, 70). Thus, we further assessed the TLR4 -NF-κB signaling pathway. In the present study, the expression of TLR4, p-p65, and p-IκB was higher in the DSS group than that in the control group, but this trend was reversed by high dose of L. plantarum L15 administration. In addition, TLR4 up-regulation has been detected during intestinal examination of IBD patients, its activation by DSS administration has been reported (71, 72).

In summary, in vitro and in vivo results from our study demonstrated that L. plantarum L15 possessed good gastrointestinal transit tolerance, adhesion, and reduction of pro-inflammatory abilities. In addition, the gut microbiota of UC mice were positively regulated by high dose of L. plantarum L15 supplementation, as evidenced in down-regulating LPS levels, which in turn suppressed the activation of the TLR4-NF-κB signaling pathway.

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/, PRJNA4501.

The animal study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Northeast Agricultural University.

BL and XZ conceived the study and designed the project. PY and CK performed the experiment, analyzed the data, and drafted the manuscript. JG helped to revise the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Present research was financially supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (No. 45YFD0400303), the Natural Science Foundation of Heilongjiang Province, China (No. YQ2020C013) and the Academic Backbone Plan of Northeast Agricultural University (No. 19YJXG10).

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fimmu.2020.575173/full#supplementary-material

1. Ungaro R, Mehandru S, Allen PB, Peyrin-Biroulet L, Colombel J-F. Ulcerative colitis. Lancet. (2017) 389:1756–70. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)32126-2

2. Ng SC, Bernstein CN, Vatn MH, Lakatos PL, Loftus EV, Tysk C, et al. Geographical variability and environmental risk factors in inflammatory bowel disease. Gut. (2013) 62:630–49. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2012-303661

3. Matsuoka K, Saito E, Fujii T, Takenaka K, Kimura M, Nagahori M, et al. Tacrolimus for the treatment of ulcerative colitis. Intest Res. (2015) 13:219–26. doi: 10.5217/ir.2015.13.3.219

4. Sánchez B, Delgado S, Blanco-Míguez A, Lourenço A, Gueimonde M, Margolles A. Probiotics, gut microbiota, and their influence on host health and disease. Mol Nutr Food Res. (2017) 61:1600240. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.201600240

5. Faith JJ, Guruge JL, Charbonneau M, Subramanian S, Seedorf H, Goodman AL, et al. The long-term stability of the human gut microbiota. Science. (2013) 341:1237439. doi: 10.1126/science.1237439

6. Ryan FJ, Ahern A, Fitzgerald R, Laserna-Mendieta E, Power E, Clooney A, et al. Colonic microbiota is associated with inflammation and host epigenomic alterations in inflammatory bowel disease. Nat Commun. (2020) 11:1512. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-15342-5

7. Sartor RB. Microbial influences in inflammatory bowel diseases. Gastroenterology. (2008) 134:577–94. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.11.059

8. Gevers D, Kugathasan S, Denson LA, Vázquez-Baeza Y, van Treuren W, Ren B, et al. The treatment-naive microbiome in new-onset Crohn's disease. Cell Host Microbe. (2014) 15:382–92. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2014.02.005

9. Bennet SM, Böhn L, Störsrud S, Liljebo T, Collin L, Lindfors P, et al. Multivariate modelling of faecal bacterial profiles of patients with IBS predicts responsiveness to a diet low in FODMAPs. Gut. (2018) 67:872–81. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2016-313128

10. Sokol H, Seksik P. The intestinal microbiota in inflammatory bowel diseases: time to connect with the host. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. (2010) 26:327–31. doi: 10.1097/MOG.0b013e328339536b

11. Huttenhower C, Kostic AD, Xavier RJ. Inflammatory bowel disease as a model for translating the microbiome. Immunity. (2014) 40:843–54. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.05.013

12. Jacobs JP, Goudarzi M, Singh N, Tong M, McHardy IH, Ruegger P, et al. A disease-associated microbial and metabolomics state in relatives of pediatric inflammatory bowel disease patients. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol. (2016) 2:750–66. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmgh.2016.06.004

13. Krishna Rao R, Samak G. Protection and restitution of gut barrier by probiotics: nutritional and clinical implications. Curr Nutr Food Sci. (2013) 9:99–107. doi: 10.2174/1573401311309020004

14. Lim S-M, Jang H-M, Jeong J-J, Han MJ, Kim D-H. Lactobacillus johnsonii CJLJ103 attenuates colitis and memory impairment in mice by inhibiting gut microbiota lipopolysaccharide production and NF-κB activation. J Funct Foods. (2017) 34:359–68. doi: 10.1016/j.jff.2017.05.016

15. Rodríguez-Nogales A, Algieri F, Garrido-Mesa J, Vezza T, Utrilla MP, Chueca N, et al. Differential intestinal anti-inflammatory effects of Lactobacillus fermentum and Lactobacillus salivarius in DSS mouse colitis: impact on microRNAs expression and microbiota composition. Mol Nutr Food Res. (2017) 61:1700144. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.201700144

16. Di Luccia B, Mazzoli A, Cancelliere R, Crescenzo R, Ferrandino I, Monaco A, et al. Lactobacillus gasseri SF1183 protects the intestinal epithelium and prevents colitis symptoms in vivo. J Funct Foods. (2018) 42:195–202. doi: 10.1016/j.jff.2017.12.049

17. Štofilová J, Langerholc T, Botta C, Treven P, Gradišnik L, Salaj R, et al. Cytokine production in vitro and in rat model of colitis in response to Lactobacillus plantarum LS/07. Biomed Pharmacother. (2017) 94:1176–85. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2017.07.138

18. Choi S-H, Lee S-H, Kim MG, Lee HJ, Kim G-B. Lactobacillus plantarum CAU1055 ameliorates inflammation in lipopolysaccharide-induced RAW264. 7 cells and a dextran sulfate sodium–induced colitis animal model. J Dairy Sci. (2019) 102:6718–25. doi: 10.3168/jds.2018-16197

19. Wang G, Liu Y, Lu Z, Yang Y, Xia Y, Lai PF-H, et al. The ameliorative effect of a Lactobacillus strain with good adhesion ability against dextran sulfate sodium-induced murine colitis. Food Funct. (2019) 10:397–409. doi: 10.1039/C8FO01453A

20. Liu Y, Sheng Y, Pan Q, Xue Y, Yu L, Tian F, et al. Identification of the key physiological characteristics of Lactobacillus plantarum strains for ulcerative colitis alleviation. Food Funct. (2020) 11:1279–91. doi: 10.1039/C9FO02935D

21. Perše M, Cerar A. Dextran sodium sulphate colitis mouse model: traps and tricks. BioMed Res Int. (2012) 2012:718617. doi: 10.1155/2012/718617

22. Chen X, Zhao X, Wang H, Yang Z, Li J, Suo H. Prevent effects of Lactobacillus fermentum HY01 on dextran sulfate sodium-induced colitis in mice. Nutrients. (2017) 9:545. doi: 10.3390/nu9060545

23. Maragkoudakis PA, Zoumpopoulou G, Miaris C, Kalantzopoulos G, Pot B, Tsakalidou E. Probiotic potential of Lactobacillus strains isolated from dairy products. Int Dairy J. (2006) 16:189–99. doi: 10.1016/j.idairyj.2005.02.009

24. Nuenopalop C, Narbad A. Probiotic assessment of Enterococcus faecalis CP58 isolated from human gut. Int J Food Microbiol. (2011) 145:390–4. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2010.12.029

25. Devi SM, Kurrey NK, Halami PM. In vitro anti-inflammatory activity among probiotic Lactobacillus species isolated from fermented foods. J Funct Foods. (2018) 47:19–27. doi: 10.1016/j.jff.2018.05.036

26. Liu Y, Ong W, Su Y, Hsu C, Cheng T, Tsai Y. Anti-inflammatory effects of Lactobacillus brevis K65 on RAW 264.7 cells and in mice with dextran sulphate sodium-induced ulcerative colitis. Benef Microb. (2016) 7:387–96. doi: 10.3920/bm2015.0109

27. Cai H, Wen Z, Li X, Meng K, Yang P. Lactobacillus plantarum FRT10 alleviated high-fat diet-induced obesity in mice through regulating the PPARα signal pathway and gut microbiota. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. (2020) 104:5959–72. doi: 10.1007/s00253-020-10620-0

28. Zhou F-X, Chen L, Liu X-W, Ouyang C-H, Wu X-P, Wang X-H, et al. Lactobacillus crispatus M206119 exacerbates murine DSS-colitis by interfering with inflammatory responses. World J Gastroenterol. (2012) 18:2344–56. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i19.2344

29. Murthy S, Cooper HS, Shim H, Shah RS, Ibrahim SA, Sedergran DJ. Treatment of dextran sulfate sodium-induced murine colitis by intracolonic cyclosporin. Digest Dis Sci. (1993) 38:1722–34. doi: 10.1007/BF01303184

30. Camuesco D, Comalada M, Rodríguez-Cabezas ME, Nieto A, Lorente MD, Concha A, et al. The intestinal anti-inflammatory effect of quercitrin is associated with an inhibition in iNOS expression. Br J Pharmacol. (2004) 143:908–18. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0705941

31. Laroui H, Ingersoll S, Liu H, Baker M, Ayyadurai S, Charania M, et al. Dextran sodium sulfate (DSS) induces colitis in mice by forming nano-lipocomplexes with medium-chain-length fatty acids in the colon. PLoS ONE. (2012) 7:e32084. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0032084

32. Kim K-A, Jeong J-J, Kim D-H. Lactobacillus brevis OK56 ameliorates high-fat diet-induced obesity in mice by inhibiting NF-κB activation and gut microbial LPS production. J Funct Foods. (2015) 13:183–91. doi: 10.1016/j.jff.2014.12.045

33. Magoč T, Salzberg SL. FLASH: fast length adjustment of short reads to improve genome assemblies. Bioinformatics. (2011) 27:2957–63. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr507

34. Caporaso JG, Kuczynski J, Stombaugh J, Bittinger K, Bushman FD, Costello EK, et al. QIIME allows analysis of high-throughput community sequencing data. Nat Methods. (2010) 7:335–6. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.f.303

35. Bokulich NA, Subramanian S, Faith JJ, Gevers D, Gordon JI, Knight R, et al. Quality-filtering vastly improves diversity estimates from Illumina amplicon sequencing. Nat Methods. (2013) 10:57–9. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2276

36. Edgar RC, Haas BJ, Clemente JC, Quince C, Knight R. UCHIME improves sensitivity and speed of chimera detection. Bioinformatics. (2011) 27:2194–200. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr381

37. Edgar RC. UPARSE: highly accurate OTU sequences from microbial amplicon reads. Nat Methods. (2013) 10:996–8. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2604

38. Yilmaz P, Parfrey LW, Yarza P, Gerken J, Pruesse E, Quast C, et al. The SILVA and “All-species living tree project (LTP)” taxonomic frameworks. Nucleic Acids Res. (2014) 42:D643–8. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1209

39. Langille MGI, Zaneveld J, Caporaso JG, Mcdonald D, Dan K, Reyes JA, et al. Predictive functional profiling of microbial communities using 16S rRNA marker gene sequences. Nature Biotechnol. (2013) 31:814–21. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2676

40. Cosnes J, Gower–Rousseau C, Seksik P, Cortot A. Epidemiology and natural history of inflammatory bowel diseases. Gastroenterology. (2011) 140:1785–94.e84. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.01.055

41. Jensen H, Grimmer S, Naterstad K, Axelsson L. In vitro testing of commercial and potential probiotic lactic acid bacteria. Int J Food Microbiol. (2012) 153:216–22. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2011.11.020

42. Arena MP, Capozzi V, Spano G, Fiocco D. The potential of lactic acid bacteria to colonize biotic and abiotic surfaces and the investigation of their interactions and mechanisms. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. (2017) 101:2641–57. doi: 10.1007/s00253-017-8182-z

43. Ouwehand AC, Salminen S, Isolauri E. Probiotics: an overview of beneficial effects. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek. (2002) 82:279–89. doi: 10.1007/978-94-017-2029-8_18

44. Zhang Z, Shen P, Liu J, Gu C, Lu X, Li Y, et al. In vivo study of the efficacy of the essential oil of Zanthoxylum bungeanum pericarp in dextran sulfate sodium-induced murine experimental colitis. J Agric Food Chem. (2017) 65:3311–9. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.7b01323

45. Sun MC, Zhang FC, Yin X, Cheng BJ, Zhao CH, Wang YL, et al. Lactobacillus reuteri F-9-35 prevents DSS-induced colitis by inhibiting proinflammatory gene expression and restoring the gut microbiota in Mice. J Food Sci. (2018) 83:2645–52. doi: 10.1111/1750-3841.14326

46. Kim JJ, Shajib MS, Manocha MM, Khan WI. Investigating intestinal inflammation in DSS-induced model of IBD. J Vis Exp. (2012) 60:e3678. doi: 10.3791/3678

47. Saiki T. Myeloperoxidase concentrations in the stool as a new parameter of inflammatory bowel disease. Kurume Med J. (1998) 45:69–73. doi: 10.2739/kurumemedj.45.69

48. Tatiya-Aphiradee N, Chatuphonprasert W, Jarukamjorn K. Immune response and inflammatory pathway of ulcerative colitis. J Basic Clin Physiol Pharmacol. (2018) 30:1–10. doi: 10.1515/jbcpp-2018-0036

49. Wang XM, Lu Y, Wu LY, Yu SG, Zhao BX, Hu HY, et al. Moxibustion inhibits interleukin-12 and tumor necrosis factor alpha and modulates intestinal flora in rat with ulcerative colitis. World J Gastroenterol. (2012) 018:6819–28. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i46.6819

50. Alex P, Zachos NC, Nguyen T, Gonzales L, Chen T-E, Conklin LS, et al. Distinct cytokine patterns identified from multiplex profiles of murine DSS and TNBS-induced colitis. Inflamm Bowel Dis. (2008) 15:341–52. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20753

51. Boussenna A, Goncalves-Mendes N, Joubert-Zakeyh J, Pereira B, Fraisse D, Vasson M-P, et al. Impact of basal diet on dextran sodium sulphate (DSS)-induced colitis in rats. Eur J Nutr. (2015) 54:1217–27. doi: 10.1007/s00394-014-0800-2

52. Geier MS, Butler RN, Giffard PM, Howarth GS. Lactobacillus fermentum BR11, a potential new probiotic, alleviates symptoms of colitis induced by dextran sulfate sodium (DSS) in rats. Int J Food Microbiol. (2007) 114:267–74. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2006.09.018

53. Liu YW, Su YW, Ong WK, Cheng TH, Tsai YC. Oral administration of Lactobacillus plantarum K68 ameliorates DSS-induced ulcerative colitis in BALB/c mice via the anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory activities. Int Immunopharmacol. (2011) 11:2159–66. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2011.09.013

54. Satish Kumar CSV, Kondal Reddy K, Reddy AG, Vinoth A, Ch SRC, Boobalan G, et al. Protective effect of Lactobacillus plantarum 21, a probiotic on trinitrobenzenesulfonic acid-induced ulcerative colitis in rats. Int Immunopharmacol. (2015) 25:504–10. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2015.02.026

55. Vemuri R, Gundamaraju R, Shinde T, Eri R. Therapeutic interventions for gut dysbiosis and related disorders in the elderly: antibiotics, probiotics or faecal microbiota transplantation? Benef Microbes. (2017) 8:179–92. doi: 10.3920/BM2016.0115

56. Garcia-Mantrana I, Selma-Royo M, Alcántara Baena C, Collado MC. Shifts on gut microbiota associated to mediterranean diet adherence and specific dietary intakes on general adult population. Front Microbiol. (2018) 9:890. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.00890

57. Zhang F, Li Y, Wang X, Wang S, Bi D. The impact of Lactobacillus plantarum on the gut microbiota of Mice with DSS-induced colitis. BioMed Res. Int. (2019) 2019:3921315. doi: 10.1155/2019/3921315

58. Imhann F, Vila AV, Bonder MJ, Fu J, Gevers D, Visschedijk MC, et al. Interplay of host genetics and gut microbiota underlying the onset and clinical presentation of inflammatory bowel disease. Gut. (2018) 67:108–19. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2016-312135

59. Louis P, Flint HJ. Diversity, metabolism and microbial ecology of butyrate-producing bacteria from the human large intestine. FEMS Microbiol Lett. (2009) 294:1–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2009.01514.x

60. Reichardt N, Duncan SH, Young P, Belenguer A, Leitch CM, Scott KP, et al. Phylogenetic distribution of three pathways for propionate production within the human gut microbiota. ISME J. (2014) 8:1323–35. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2014.14

61. Imaoka A, Shima T, Kato K, Mizuno S, Uehara T, Matsumoto S, et al. Anti-inflammatory activity of probiotic Bifidobacterium: enhancement of IL-10 production in peripheral blood mononuclear cells from ulcerative colitis patients and inhibition of IL-8 secretion in HT-29 cells. World J Gastroenterol. (2008) 14:2511–6. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.2511

62. Jeon SG, Kayama H, Ueda Y, Takahashi T, Asahara T, Tsuji H, et al. Probiotic Bifidobacterium breve induces IL-10-producing Tr1 cells in the colon. PLoS Pathog. (2012) 8:e1002714. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002714

63. Di Lorenzo F, de Castro C, Silipo A, Molinaro A. Lipopolysaccharide structures of Gram-negative populations in the gut microbiota and effects on host interactions. FEMS Microbiol Rev. (2019) 43:257–72. doi: 10.1093/femsre/fuz002

64. Goldstein EJ, Citron DM, Peraino VA, Cross SA. Desulfovibrio desulfuricans bacteremia and review of human Desulfovibrio infections. J Clin Microbiol. (2003) 41:2752–4. doi: 10.1128/JCM.41.6.2752-2754.2003

65. Lupp C, Robertson ML, Wickham ME, Sekirov I, Champion OL, Gaynor EC, et al. Host-mediated inflammation disrupts the intestinal microbiota and promotes the overgrowth of Enterobacteriaceae. Cell Host Microbe. (2007) 2:119–29. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2007.06.010

66. Cani PD, Amar J, Iglesias MA, Poggi M, Knauf C, Bastelica D, et al. Metabolic endotoxemia initiates obesity and insulin resistance. Diabetes. (2007) 56:1761–72. doi: 10.2337/db06-1491

67. Ning W, Wang H, Hua Y, Qin W, Mao XM, Tao J, et al. Expression and activity of the TLR4/NF-κB signaling pathway in mouse intestine following administration of a short-term high-fat diet. Exp Ther Med. (2013) 6:635–40. doi: 10.3892/etm.2013.1214

68. Wang Y, Tu Q, Wei Y, Dan X, Zeng Z, Ouyang Y, et al. CXC195 suppresses proliferation and inflammatory response in LPS-induced human hepatocellular carcinoma cells via regulating TLR4-MyD88-TAK1-mediated NF-κB and MAPK pathway. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. (2015) 456:373–9. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2014.11.090

69. Makarov SS. NF-κB as a therapeutic target in chronic inflammation: recent advances. Mol Med Today. (2000) 6:441–8. doi: 10.1016/S1357-4310(00)01814-1

70. Tak PP, Firestein GS. NF-κB: a key role in inflammatory diseases. J Clin Invest. (2001) 107:7–11. doi: 10.1172/JCI11830

71. Chen L, Lin M-J, Zhan L-L, Lv X-P. Analysis of TLR4 and TLR2 polymorphisms in inflammatory bowel disease in a Guangxi Zhuang population. World J Gastroenterol. (2012) 18:6856–60. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i46.6856

Keywords: Lactobacillus plantarum, DSS-colitis, gut microbiota, lipopolysaccharide (LPS), NF-κB signaling

Citation: Yu P, Ke C, Guo J, Zhang X and Li B (2020) Lactobacillus plantarum L15 Alleviates Colitis by Inhibiting LPS-Mediated NF-κB Activation and Ameliorates DSS-Induced Gut Microbiota Dysbiosis. Front. Immunol. 11:575173. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.575173

Received: 24 June 2020; Accepted: 02 September 2020;

Published: 02 October 2020.

Edited by:

Margarida Castell, University of Barcelona, SpainReviewed by:

Leonardo Borges Acurcio, Centro Universitário de Formiga, BrazilCopyright © 2020 Yu, Ke, Guo, Zhang and Li. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Xiuling Zhang, MTQ1Nzk0NTIwMUBxcS5jb20=; Bailiang Li, MTU4NDYwOTIzNjJAMTYzLmNvbQ==

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.