95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Immunol. , 07 August 2019

Sec. Comparative Immunology

Volume 10 - 2019 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2019.01825

Ming Li1†

Ming Li1† Panpan Xi1†

Panpan Xi1† Yuanyuan Xu1

Yuanyuan Xu1 Zhenglei Wang1

Zhenglei Wang1 Xiangan Han2

Xiangan Han2 Wenkai Ren3

Wenkai Ren3 Vanhnaseng Phouthapane4

Vanhnaseng Phouthapane4 Jinfeng Miao1*

Jinfeng Miao1*Taurine may alleviate the inflammatory injury induced by Streptococcus uberis (S. uberis) infection by regulating intracellular Ca2+ levels. However, the underlying mechanisms remain unclear. Infection leads to subversion of phosphoinositides (PIs) which are closely related to Ca2+ signaling. In order to investigate whether taurine regulates inflammation by means of PIs/ Ca2+ systems, competitive inhibitors of taurine (β-alanine) siTauT, siPAT1, siPLC, siCaN, siPKC, and inhibitors of PLC (U73122), PKC (RO31-8220), and CaN (FK 506) were used. The results indicate that taurine transfers the extracellular nutrient signal for intercellular innate immunity to phosphoinositides without a need to enter the cytoplasm while regulating intracellular Ca2+ levels during inflammation. Both the Ca2+-PKCα-NF-κB, and Ca2+-CaM-CaN-NFAT signaling pathways of S. uberis infection and the regulatory roles of taurine follow activation of PIs/Ca2+ systems. These data increase our understanding on the mechanisms of multifunctional nutrient, taurine attenuated inflammatory responses caused by S. uberis infection, and provide theoretical support for the prevention of this disease.

Bovine mastitis is the most important disease of dairy cattle, leading to enormous production losses (1, 2). Streptococcus uberis (S. uberis) is an important mastitis causing pathogen due to its ability to adhere to the surfaces of mammary alveoli and internalize into mammary epithelial cells (MECs) thus escaping elimination by the host (3–5). Conventional mastitis control measures including the use of vaccines and antibiotics are ineffective and may lead to resistant superorganisms and drug residue in milk products (6). Regulating the natural defense mechanisms of the mammary gland and/or MECs to reduce the risk or degree of infection may be useful in controlling various udder pathogens and intracellular infections. It has been reported that Panax ginseng extract is able to trigger an adequate immune response demonstrating its protective effect and potential for preventing bovine intramammary infection with Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus) (7). Helenalin reduces S. aureus intracellular growth and experimental S. aureus infection through the inhibition of inflammatory factors secretion (8). Taurine (2-aminoethanesulfonic acid), one of the most abundant free amino acids in most animal tissues has many fundamental biological roles (9). It is suggested that additional administration of taurine and its derivatives may regulate the host's innate immune response and be effective in the treatment or prevention of various topical infections and inflammatory diseases (10–12). Studies in our lab reveal that taurine can increase antioxidant ability, down-regulate inflammatory responses and moderate injury of mammary gland/MECs from S. uberis challenge (13–15). The underlying mechanism(s) of how taurine attenuates the inflammatory response of mammary gland challenged by S. uberis is confusing and likely complex.

Previous studies established that taurine crosses the cytomembrane via 2 transporters: (1) the high-affinity, low-capacity Na+- and Cl−-dependent transporter TauT (SLC6A6); (2) the low-affinity, high-capacity H+-coupled, pH-dependent, Na+-and Cl− -independent transporter PAT1 (SLC36A1) (16, 17). Taurine influx modulates the activity of voltage-dependent Ca2+, Na+ channels and the activity of the Na+/Ca2+exchanger which results in the regulation of cytoplasmic free Ca2+ concentrations and initiates the triggering of Ca2+ signaling (18, 19). Recently, it has been shown that Ca2+, as a second messenger, participates in variant bacterial infections (20, 21). Our former study found taurine could attenuate inflammatory injury in mouse MECs after S. uberis challenge by regulating intracellular Ca2+ levels and the activities of transcription factors NF-κB and NFAT. The exact means by which taurine affects the intracellular Ca2+ levels and the relationship between Ca2+ changing and inflammatory responses remain unclear.

Phosphoinositides (PIs) form a minor component on the cytosolic side of eukaryotic cell membranes. They mainly consist of phosphatidylinositol (PI) and the 3 polyphosphoinositides, namely phosphatidylinositol 4-phosphate (PI4P), phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate [PI(4,5)P2] and phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-trisphosphate [PI(3,4,5)P3]. The polyphosphoinositides are various phosphorylation states of PI in its headgroup inositol. Research in the last 20 years has disclosed a wide range of biological processes connected with PIs, turning these lipids into one of the most universal signaling entities in cells that play multiple roles in biology (22). Infection leads to the subversion of PIs metabolism (the relative ratios converting among the 4 component of PIs), that facilitate bacterial engulfment and could modulate the inflammatory response (23–25). Turnover among PIs caused by the activation of surface receptors including G-protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) and receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs) when cells are exposed to various extracellular stimuli trigger an increase in cytosolic Ca2+ concentration. This increase results from Ca2+ influx into the cell through Ca2+ channels in the plasma membrane and Ca2+ efflux from intracellular stores in the organelles (26–28). These phenomena led to our interest in determining if modulation of PIs metabolism plays a key role in taurine attenuation of S uberis-induced inflammatory injury in bMECs and if the regulating role of taurine on the inflammatory responses is related to the activition of NF-κB and NFAT mainly by Ca2+ mediated signaling pathways in S. uberis infection. Herein, we provide insight into the mechanism(s) of taurine attenuation of inflammatory injury in bovine MECs in S. uberis infection and the role of phosphoinositides/Ca2+ systems in this bioprocess.

S. uberis 0140J, an encapsulated strain, was purchased from ATCC (USA). For experimental use, bacterial strains were streaked onto Todd-Hewitt broth (THB) solid medium containing 2% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Gibco, Gaithersburg, MD, USA) at 37°C for 24 h. A single colony was put into THB fluid medium at 37°C overnight with shaking. Following 10 μL of overnight culture it was transferred to 1 mL fresh THB at 37°C with shaking until the OD600 reached 0.5–0.6.

MAC-T cells were a gift from Dr. Loor (University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, Champaign, IL, USA). Culture fluid contained 10% FBS (Gibco, Gaithersburg, MD, USA), 5 mg/L insulin, 1 mg/L hydrocortisone, 5 mg/L transferrin, 5 μM/L ascorbic acid and 5 mM/L sodium acetate (all from Sigma, St. Louis, MO) in a humidified environment with 5% CO2:95% air at 37°C.

MAC-T cells were cultured in 6-well plates to 80% confluence, following removal and culture in serum free medium for 4 h. Confluent monolayers were treated with or without 45 mM of taurine (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) for 24 h. For inhibition experiments, 60 mM β-alanine (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA), a competitive inhibitor of taurine; 10 μM U73122, an inhibitor of PLC (dissolved in DMF, Selleck, USA); 10 nM RO31-8220, an inhibitor of PKC (dissolved in DMSO, Selleck, USA); and 100 μM FK 506, an inhibitor of CaN (Astellas, Ireland) were used to pre-treat cells for 1 h. The concentration of taurine, FK 506 and β-alanine was based on previous studies and at these concentrations there was no cytotoxicity (13, 29, 30). Dosages of U73122 and RO31-8220 were based on the manufacturer's recommendations. S. uberis was added at mid-exponential phase at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 10 for 1–4 h at 37°C. Supernatants were collected and cells were trypsinized (Gibco, Gaithersburg, MD, USA) then centrifuged (1,000 rpm for 5 min) resuspended in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; Hyclone, Logan, UT, USA) or lysed by incubating on ice for 30 min with lysis buffer (Beyotime, Nantong, China). Supernatants were collected by centrifugation at 1,500 rpm for 10 min at 4°C for further analysis.

For RNA interference tests, the MAC-T cells monolayer was transfected with 50 nm specific siTauT, siPAT1, siPLC, siCaN, siPKC (Ribobio, Guangzhou, China) for 72 h using Lipofectamine 3000 (Invitrogen, U.S.A) reagent according to the manufacturer's instructions, and then administrated taurine for another 24 h. Subsequently, cells were infected with S. uberis in mid-exponential phase at a MOI of 10 for 3 h at 37°C. Supernatants were collected and the cells were trypsinized (Gibco, Gaithersburg, MD, USA), centrifuged (1,000 rpm for 5 min) and resuspended in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; Hyclone, Logan, UT, USA) for further analysis.

Intracellular ROS was evaluated by staining MAC-T cells with DCFH-DA, a fluorescent ROS-sensitive indicator that freely permeates cell membranes. Briefly, after incubating with 10 μM DCFH-DA for 30 min at 37°C, cells were washed 3 times in phosphate buffered saline (PBS) and detached. They were collected at 400 × g for 5 min, resuspended in PBS and immediately analyzed by flow cytometry using FACSCanto.

For intracellular Ca2+ detection, cells were washed once in HBSS flux buffer (Hank's balanced salt solution) without calcium chloride, chloride, magnesium sulfate, and phenol red. The cells were incubated in 5 μM Fluo-3/AM (Bebytime, Nantong, China) for 30 min at 37°C, washed 3 times with HBSS flux buffer, and immediately analyzed by flow cytometry.

Ten thousand cells per sample were analyzed using CellQuest Pro acquisition and analysis software.

Intracellular protein levels were determined by Western blotting analysis. GAPDH (Bioworld, USA) was employed to ensure equal loading. Cells were washed twice in ice-cold PBS, lysed with RIPA buffer (Beyotime, Nantong, China) added PMSF (Beyotime, Nantong, China) by incubating on ice for 30 min in an Eppendorf tube. The supernatants were collected by centrifuging at 12,000 rpm for 10 min at 4°C; protein concentration was determined by bicinchoninic acid assay (BCA) (Bebytime, Nantong, China). The samples were placed in a polyacrylamide gel by electrophoresis and transferred onto PVDF membranes (Millipore, USA). The membranes were blocked with 5% non-fat milk diluted in Tris buffered saline with Tween-20 (TBST) for 2 h at room temperature, and hybridized overnight with primary antibody at 4°C. Primary antibodies were PLCγ1, p-PLCγ1, NCX1, PI3K, p-PI3K, PTEN, p-PTEN, PKCα, p-PKC, IKKα, p-IKKα, IκBα, p-IκBα, GSK-3β, and p-GSK-3β. NCX1 antibodies were purchased from Albanian Broadband Communication (Abcam, Shanghai, China), and others were from Cell Signaling Technology (CST, Massachusetts, USA). Before and after incubation with the secondary antibodies at room temperature for 2 h, the membranes were washed 3 times with TBST. Secondary antibody is horseradish peroxidase (HRP)—conjugated rabbit anti-goat secondary antibody (CST, Massachusetts, USA). The signals were detected by an ECL Western blot analysis system (Tanon, Shanghai, China). Analysis of bands was quantified with Image J software (NIH, USA).

The cell-free supernatant was collected as described above and TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 measured by ELISA kits (Rigor Bioscience, Beijing, China) according to the manufacturer's instructions. For the detection of PIs, the treated cells were collected in PBS with thawing and refreezing four times and centrifuged at 2,000 rpm for 20 min. The concentrations of PIP3, PIP2, IP3, and CaM in supernatant were detected by commercial ELISA kits (Jianglaibio, Shanghai, China) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, the sample and Streptavidin-HRP was incubated for 60 min at 37°C with gently shanking, and then, washed 3 times followed by addition of solution A and solution B to each well for 10 min at 37°C. Finally, stop solution was added and absorbance detected using a microplate reader (Thermo, USA) at 450 nm.

Cells were cultured on round coverslips up to 50% confluence. NF-κB-GFP or NFAT-GFP reporter plasmids (Yesen Biology, Shanghai, China) were transfected into cells via Lipofectamine 3000 (Thermo, USA) according to the manufacturer's protocol. After transfection for 6 h, MAC-T cells were pretreated with β-alanine for 1 h and then taurine for another 24 h. Subsequently, S. uberis in mid-exponential phase at a MOI of 10 was added. One hour later, the nutrient solution containing Hoechst 33342 (Bebytime, Nantong, China) was used for another 10 min in the dark for nuclear staining. The translocation status of NF-κB or NFAT into the nucleus was detected by confocal microscopy and a fluorescence microscope (Carl Zeiss, LSM 710).

The DNA binding activities of transcription factors (NF-κB and NFAT) in each nucleoprotein extraction solution were sensitively quantified based on DNA-Ag nanocluster molecular beacons and exonuclease III-assisted signal amplification strategy. Briefly, 80 nM of probe (NF-κB or NFAT probe) was mixed with different types of nucleoprotein extracting solutions adjusted to 6 μg/mL. Then, protein binding buffer (10 mM PBS, 1 mM Mg(CH3COOH)2, 10% glycerol, 0.05 mg/mL poly(dI-dC), pH 7.4) was added into the above solution until the volume reached 25 μL. Two microliter of 10 U/μL Exo III and 3 μL of 10 × Exo III reaction buffer were added for digestion for 30 min at 37°C. Fifteen microliter of Ag nanoclusters molecular beacons (AgMBs), 3 μL of DEPC-treated water, and 2 μL of 10 × Exo III reaction buffer was added to the above solution to bring the total volume of the solution to 50 μL. After incubation at 37°C for 30 min, the solution was mixed with 200 μL of 10 mM PBS and fluorescent signals were recorded by Ls55 PerkinElmer fluorescence spectrophotometer (PerkinElmer, America) under excitation at 564 nm. The emission scan range was chosen between 600 and 700 nm. The probe sequences are listed in Table 1.

The activities or levels of CaN, NAGase, LDH, iNOS and NO were determined using commercial kits purchased from the Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute (Nanjing, China), following the manufacturer's instructions. The assay for CaN activity in cells was based on its ability to catalyze disodium 4-nitrophenyl phosphate (PNPP) to generate the chromogenic substrate p-nitrophenol. One unit (U) of CaN activity was defined as the amount that increased absorbance at a wavelength of 405 nm. For the detection of NAGase activity in supernatant, the optical density of paranitrophenol during the reaction at 37°C between 4-methy-lumbelliferyl-N-acetyl-β-glucosaminide substrate with the NAGase contained in the analyzed samples was measured at 400 nm. To measure the activity of LDH, the supernatants were mixed with coenzyme 1 in buffer solution for 15 min at 37°C, mixed with 2, 4-dinitrophenylhydrazine. Sodium hydroxide was used to stop the reaction and measured at 450 nm. For the detection of iNOS activity in cells, the sample was incubated with 0.6 mL reaction buffer and combined with an inhibitor of cNOS (6 mmol/L EGTA). This action was terminated after 15 min at 37°C with 10 mmol/L EDTA and 10 mmol/L HEPES buffer. The formation of a colored chemical compound was photometrically measured at 530 nm. NO production was monitored by measuring the nitrite content in culture medium. The color developing agent was mixed with samples at room temperature for 15 min and measured at 550 nm in a microplate reader (Thermo, USA). Sodium nitrite was the standard. The ABTS method was used to measure total antioxidant capacity; the reason is that ABTS is oxidized to ABTS+; while the generation of ABTS+ is inhibited in the presence of anti-oxidant. The formation of a colored chemical compound was photometrically measured at 520 nm.

Cells supernatants were collected for surveying concentration by BCA utilized for inflammation cytokines/molecules detection by a Quantibody Mouse Inflammation Array Q1 kit (2) (Ray Biotech, Inc, Norcross, GA; Cat. No. QAM-INF- 1) according to the manufacturer's instructions that can semi-quantitatively authenticate 40 factors. The signals, green fluorescence and Cy3 channel, were gathered via a Gene Pix 4000B laser scanner (Bio-Rad, CA) at 555 nm excitation and 565 nm emission and loading using Gene Pix Pro 6.0 microarray analysis software. Semi-quantitative analysis was performed using Ray Biotech mouse Inflammation Array 1 software (QAM-INF-1_Q Analyzer). The mean fluorescence intensities (median values) of the control group were used as standard.

Total RNA was extracted using TRIZOL reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) and reverse transcribed (RT) into cDNA using PrimeScriptTM RT reagent kit (Taraka, Dalian, China). The PCR reaction was in a total volume of 20 μL using a SYBR Premix Ex TaqTM (Taraka, Dalian, China) in which 2 μL cDNA was added as a template. The primer sequences are in Table 2. As an internal control, the same RT products were subjected to PCR in the presence of a second pair of primers specific to GADPH. Analysis of the relative dates of gene expression used the 2−ΔΔCt method.

The dates in this study were computed using statistical software SPSS 19.0 and results were expressed as means ± SEM. Statistical analyses of the date were performed by ANOVA with a post-hoc test. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

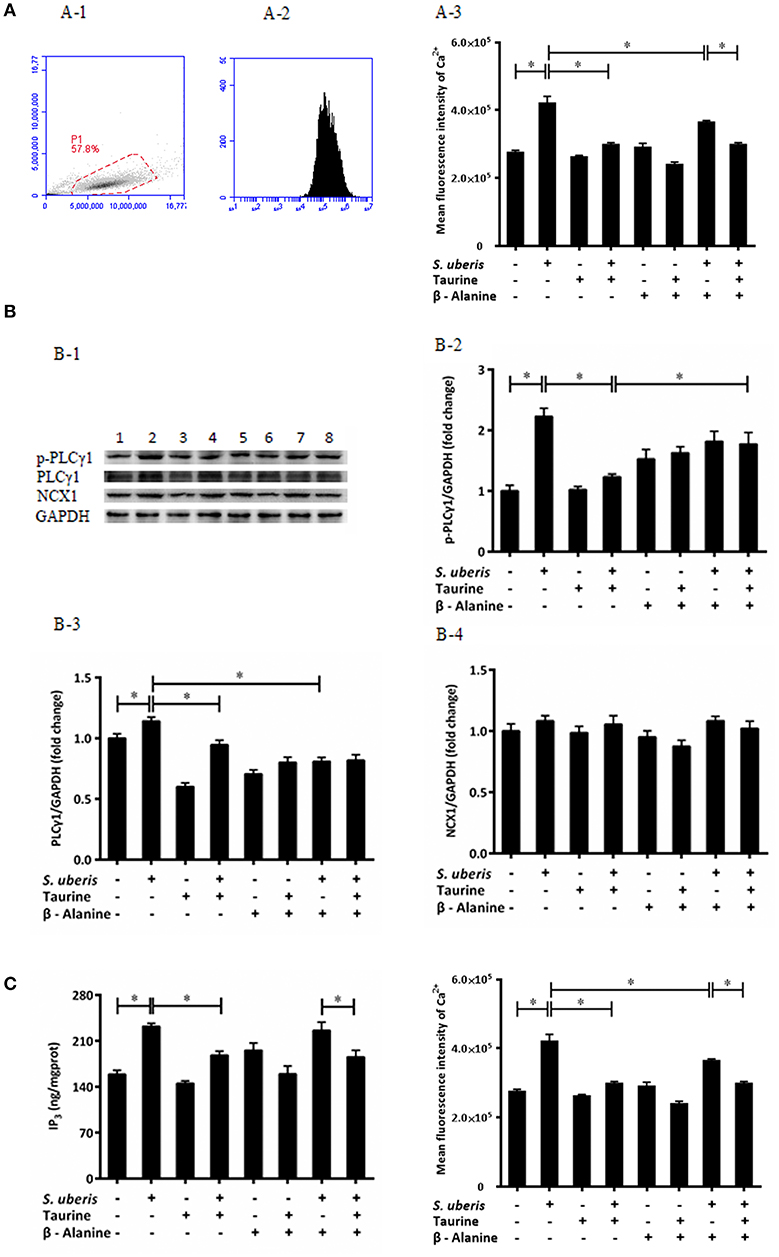

Ca2+ is a universal signaling molecule in cells. An increase of the intracellular concentration of Ca2+ has been confirmed to be closely related to infection of variant bacteria including S. uberis. In the current study, the concentration of intracellular Ca2+ was measured by flow cytometry (Figures 1A-1,A-2). As shown in Figure 1A-3, compared with the control, the concentration of intracellular Ca2+ in the S. uberis challenged group was markedly higher (P < 0.05). Taurine administration significantly decreased intracellular Ca2+ levels (P < 0.05).

Figure 1. Taurine downregulates cytoplasmic Ca2+ concentration in S. uberis challenged MAC-T cells through PLCγ1/IP3 signaling system. (A) MAC-T cells were pretreated with β-alanine for 1 h and then administrated taurine for 24 h. Subsequently, cells were infected with S. uberis in mid-exponential phase at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 10 for 3 h at 37°C. Intracellular Ca2+ concentration was evaluated by staining cells with Fluo-3 AM. 10,000 cells per sample were analyzed using Cell Quest Pro acquisition and analysis software. Gating of the cell population (A-1), pictorial diagram (A-2), and statistic results (A-3). (B) After pretreated with β-alanine and taurine, MAC-T cells were infected with S. uberis for 4 h at 37°C. The protein expression of PLCγ1, NCX1, and the phosphorylation levels of PLCγ1 (p-PLCγ1) were determined by Western blot (B-1). Lines 1-8 represent control, S. uberis, taurine, S. uberis + taurine, β-alanine, β-alanine + taurine, β-alanine + S. uberis, β-alanine + taurine + S. uberis respectively. To confirm equal protein loading, blots were re-probed with an antibody against GADPH. Results of statistical analysis for p-PLCγ1 (B-2), PLCγ1 (B-3), and NCX1 (B-4) compared to GADPH. (C) Two hours after S. uberis challenge, the concentration of IP3 was determined using ELISA kits. Statistic results are representative of 3 independent experiments. Data are presented as the means ± SEM. *(P < 0.05) = significantly different between the indicated groups.

In resting cells, the concentration of cytoplasmic Ca2+ is normally lower than extracellular and intracellular stores (endoplasmic reticulum, mitochondria). Signaling occurs when the cell is stimulated to release Ca2+ from intracellular stores, and/or when calcium enters the cell through plasma membrane ion channels. At the beginning of infection, the sudden increase of cytosolic Ca2+ mainly comes from endoplasmic reticulum through the opening of IP3-gated Ca2+-release channels (31). In order to investigate whether the regulating role of taurine to cytosolic Ca2+ concentration connects with IP3-gated Ca2+-release channels in S. uberis challenged bMECs, we determined the IP3 levels in cytoplasm, protein expression of PLCγ1 and its phosphorylation levels (Figure 1B-1) as this enzyme catalyzes the hydrolysis of PIP2 to generate the second messenger IP3. A considerably up-regulated PLCγ1 and its phosphorylation levels were observed between the control and S. uberis infection groups (P < 0.05). Pre-treatment with taurine significantly reduced this change (P < 0.05) (Figures 1B-2, 3). ELISA results also showed that cytosolic IP3 concentration increased after S. uberis challenge. Taurine pre-treatment subverted this change (Figure 1C).

Na+/Ca2+ exchanger (NCX) is a class of bidirectional ion transporter that couples the translocation of Ca2+ in one direction with that of Na+ in the opposite direction and thus plays an important role in the regulation of intracellular Ca2+. Herein, we used Western blot to assay the expression of NCX1, one of the NCX isoforms, and found there were no significantly differences among different groups (Figure 1B-4). This data is consistent with a previous study that found that taurine mainly inhibits the influx of Ca2+ through NCX and has no effect on the rate of Ca2+ efflux from cytoplasm (32).

The inhibitory role of taurine on increasing intracellular Ca2+ is very complex. It is clear that taurine can modulate the activity of various ion channels to regulate Ca2+ homeostasis. These factors affect taurine transport and/or directly bind with different channel proteins and membrane lipids (33, 34). To evaluate if the translocation of taurine is necessary and these ions link with the transmembrane movement of Ca2+, its analog β-alanine was used to compete with it. The results suggest that β-alanine administration did not significantly influence the down-regulatory role of taurine to cytosolic Ca2+ levels, PLCγ1 protein expression, and IP3 concentration. There were no significant differences between the taurine + S. uberis and β-alanine + taurine + S. uberis groups (P > 0.05) (Figures 1A-3,B-3,B-4,C). These data indicate that taurine could significantly decrease intracellular Ca2+ levels through the PLCγ1/IP3 signaling system after S. uberis challenge and taurine may be not enter the cytoplasm in this bioprocess.

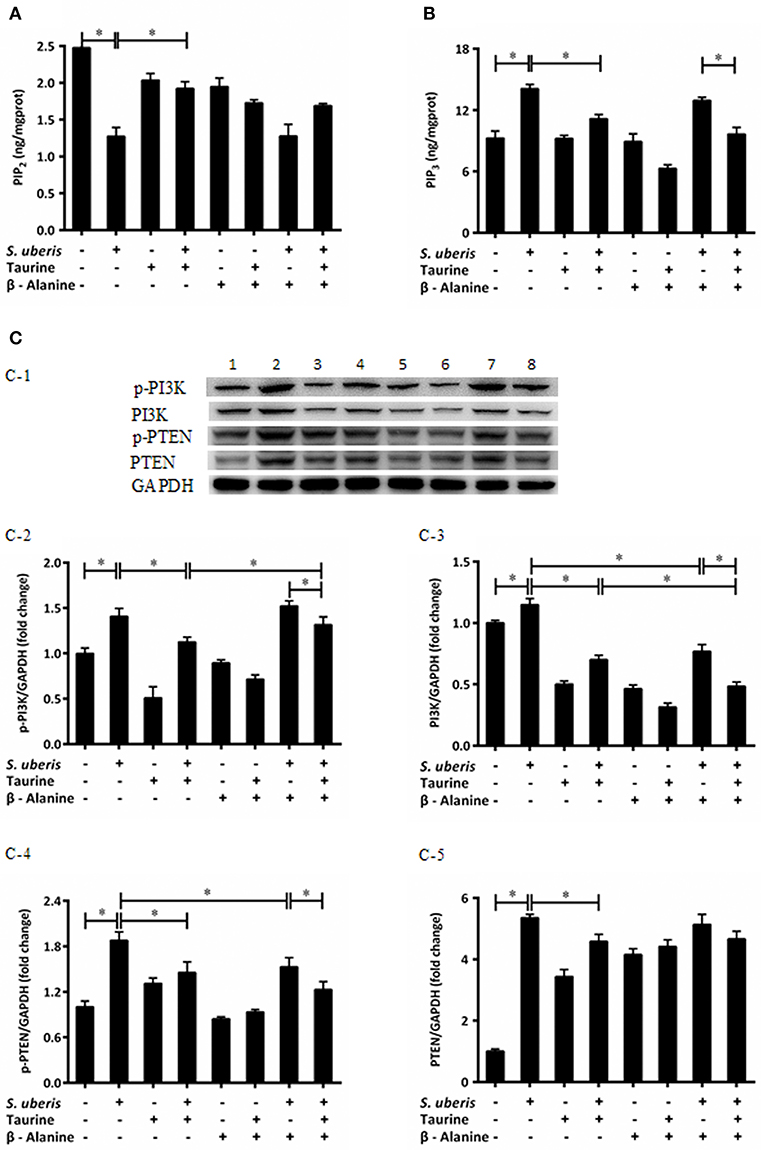

IP3 can be hydrolyzed by PLC from PIP2 post infection. Additionally, there is interconversion among different PIs when cells are attacked. The conversion of PIP2 and PIP3 act on internal membranes to control and initiate complex intracellular signaling transduction pathways (22). To determine whether taurine reduced IP3 in S. uberis infection linked with conversion of PIP2 and PIP3, PIP2, and PIP3 were evaluated by ELISA kits. Enzyme expression and phosphorylation levels of PI3K, PTEN, which catalyze the exchange of PIP2 and PIP3, were measured by Western blot. The results showed that PIP3 was significantly increased in S. uberis challenged cells. Taurine weakens this increase compared with controls. To the contrary, PIP2 was markedly decreased in MAC-T cells in S. uberis infection. Taurine pre-treatment increased its values (P < 0.05). Higher PIP2 and lower PIP3 concentrations were present in taurine + S. uberis groups than in S. uberis challenge only groups (P < 0.05). There were no significantly differences between the taurine + S. uberis and β-alanine + taurine + S. uberis groups (P > 0.05) (Figures 2A,B).

Figure 2. Taurine mediates the intracellular phosphatidylinositols conversion in S. uberis challenged MAC-T cells. (A,B) MAC-T cells were pretreated with β-alanine for 1 h and then administrated taurine for 24 h. Subsequently, cells were infected with S. uberis in mid-exponential phase at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 10 for 2 h at 37°C. Cell lysates were used and the concentration of PIP2 (A) and PIP3 (B) were detected by ELISA kits. (C) After pretreated with β-alanine and taurine, MAC-T cells were infected with S. uberis for 4 h at 37°C. The protein expression of PI3K (C-3), PTEN (C-5), and their phosphorylation levels p-PI3K (C-2), p-PTEN (C-4) were determined by Western blot (C-1). Lines 1–8 represent control, S. uberis, taurine, S. uberis + taurine, β-alanine, β-alanine + taurine, β-alanine + S. uberis, β-alanine + taurine + S. uberis, respectively. To confirm equal protein loading, blots were re-probed with an antibody against GADPH. Results of statistical analysis for p-PI3K (C-2), PI3K (C-3), p-PTEN (C-4), and PTEN (C-5) compared to GADPH. Statistic results are representative of 3 independent experiments. Data are presented as the means ± SEM. *(P < 0.05) = significantly different between the indicated groups.

Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinases (PI3Ks) are key molecules that participate in PIs cytoplasmic metabolism and regulate several key events in the inflammatory response. They selectively phosphorylate PIP2 to PIP3 in the 3-position of the inositol ring. On the contrary, PIP3 is dephosphorylated at the 3-position to re-form PIP2 by the enzyme PTEN (22, 25). So protein expressions and phosphorylation levels of PI3K and PTEN were determined (Figures 2C-1). Exposure of MAC-T cells to S. uberis significantly (P < 0.05) increases PI3K and PTEN expression and their phosphorylation levels. Taurine reduces the role of S. uberis infection (P < 0.05). β-alanine has no effect on the decreased PTEN and phosphorylation of PI3K and PTEN (P < 0.05) (Figures 2C-2,C-4,C-5), but further decreases the expression of PI3K caused by S. uberis infection (P > 0.05) (Figure 2C-3). Together, these results suggest that taurine may influence intracellular phosphatidylinositol conversion. Analog β-alanine has almost no effect on this role of taurine in S. uberis challenged MAC-T cells.

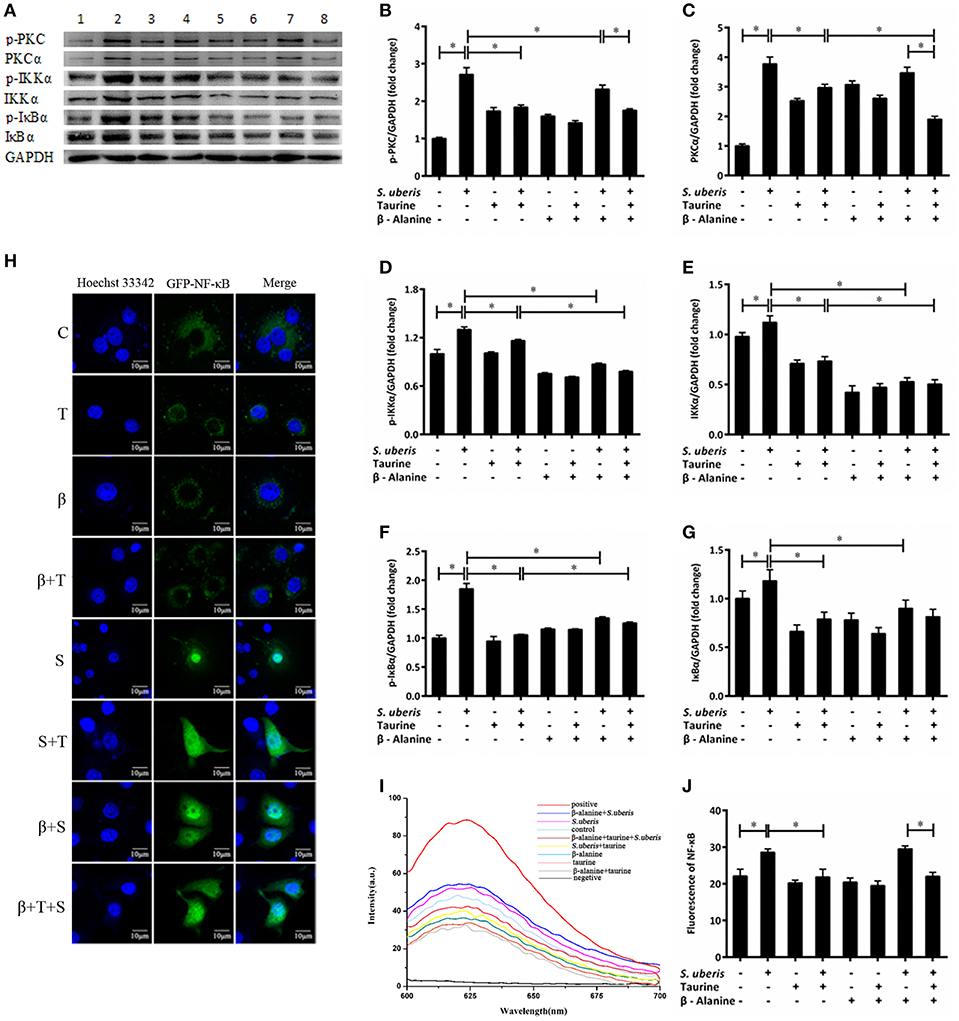

Ca2+ is linked to the inflammatory response mainly through 2 signaling pathways. One is the activation of PKC by a sudden increase in endoplasmic Ca2+ with subsequent activation of nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB); the other is the activation of nuclear factor in activated T cells (NFAT) by CaN (35, 36). Our previous studies suggest that both NF-κB and NFAT may be involved in S. uberis induced inflammation in mouse MECs and taurine has a positive regulatory role on the inflammatory response (14). In S. uberis infection of bovine MECs, following Ca2+ release to cytoplasm PKCα/NF-κB and CaN/NFAT, signaling pathways are activated and induce an intensive inflammatory response. Taurine regulates this process by modulating these changes. Key adaptors, nuclear factors NF-κB and NFAT, inflammatory factors/mediators, and markers to cell injury are assessed in detail in this study. As shown in Figure 3, the expression of PKC, IKKα, and IκBα and their phosphorylation levels were considerably up-regulated in MAC-T cells in response to S. uberis and these changes decrease in response to taurine (Figures 3B–G) (P < 0.05). β-alanine had a similar effect on IKKα and IκBα protein expression and phosphorylation (Figures 3D–G) (P < 0.05). The production p-PKC is also reduced by pre-treatment with β-alanine (Figure 3B) (P < 0.05). Co-administration of taurine and β-alanine further lower PKCα and IKKα expression and the phosphorylation of IKKα, but increase IκBα when compared with the taurine + S. uberis groups (Figures 3C–F) (P < 0.05).

Figure 3. The active PKCα/NF-κB signaling pathway is attenuated by taurine in S. uberis challenged MAC-T cells. (A–G) MAC-T cells were pretreated with β-alanine for 1 h and then administrated taurine for 24 h. Subsequently, cells were infected with S. uberis in mid-exponential phase at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 10 for 4 h at 37°C. The protein expression of PKCα (C), IKKα (E), and IκBα (G) and their phosphorylation levels p-PKC (B), p-IKKα (D), p-IκBα (F) were determined by Western blot (A). Lines 1–8 represent control, S. uberis, taurine, S. uberis + taurine, β-alanine, β-alanine + taurine, β-alanine + S. uberis, β-alanine + taurine + S. uberis, respectively. To confirm equal protein loading, blots were re-probed with an antibody against GADPH. Results of statistical analysis for p-PKC (B), PKCα (C), p-IKKα (D), IKKα (E), p-IκBα (F), and IκBα (G) compared to GADPH. (H) The translocation status of NF-κB into nucleus was detected by confocal. Blue light: nucleus; Green light: NF-κB labeled by GFP; Merge: images that the two lights simultaneously display. C, control; S, S. uberis; T,taurine; S + T, S. uberis + taurine; β, β-alanine; β + T, β-alanine + taurine; β + S, β-alanine + S. uberis; β + T + S, β-alanine + taurine + S. uberis. (I,J) The contents of NF-κB in nucleoprotein were detected by electrochemistry. The pictorial diagram (I) and statistic results (J). Statistic results are representative of three independent experiments. Data are presented as the means ± SEM. *(P < 0.05) = significantly different between the indicated groups.

NF-κB controls many genes involved in inflammation and sequesters cytoplasmic IκB. After IκB phosphorylation and detachment, free NF-κB dimers may enter the nucleus. This process can be quantified by cytochemical methods. In the current study, confocal observation demonstrated green fluorescence in the nucleus of control cells. Almost all of this fluorescence appeared in the nucleus 1 h after S. uberis challenge. Taurine administration attenuated the translocation of NF-κB. In the taurine + S. uberis group, the green fluorescence was present both in the nucleus and cytoplasm (Figure 3H). To quantify the translocation levels of NF-κB, we extracted nuclear protein using a strategy based on DNA-Ag nanocluster molecular beacons and an exonuclease III-assisted signal. As shown in Figure 3J, infection with S. uberis enhanced the translocation level of NF-κB to nucleus and taurine reversed this change. These data established that the PKCα/NF-κB signaling pathway is activated by S. uberis and the attenuation of this activity may be one of the mechanisms of taurine-associated anti-inflammation in S. uberis induced mastitis.

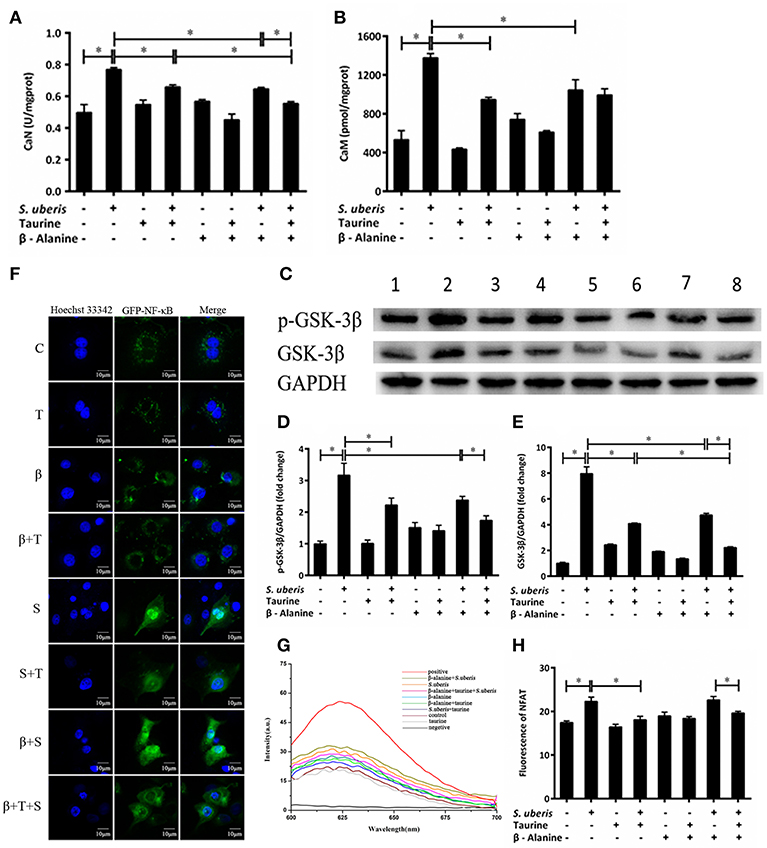

CaN is a Ca2+/CaM dependent phosphatase that is particularly relevant in the modulation of nuclear signaling events, proceeding through the family of NFAT transcription factors. Its activity is markedly increased in response to S. uberis, whereas the addition of taurine inhibits this increase (P < 0.05). β-alanine significantly inhibits the activity of CaN in response to S. uberis challenge. Co-administration of taurine further lowers the activation of CaN (P < 0.05) (Figure 4A). CaM increases significantly after S. uberis infection (P < 0.05). Taurine, β-alanine, individually or together, greatly reduce its expression (P < 0.05). There was no significant difference between the taurine + S. uberis and β-alanine + taurine + S. uberis groups (P > 0.05) (Figure 4B). Glycogen synthase kinase 3 (GSK-3) regulates the NFAT phosphorylation state and export from the nucleus (37). We quantified GSK-3β and its phosphorylation by Western blot and found they were increased in response to S. uberis (P < 0.05) and taurine decreased them (Figures 4C–E). Confocal microscopy results showed that, similar to NF-κB, more green fluorescence appeared in the nuclear region in infected cells than in controls. Taurine pre-treatment reduces the translocation of NFAT (Figure 4F). This was confirmed by quantitative detection (Figure 4H). The results suggested that the active CaN/NFAT signaling pathway can be attenuated by taurine in S. uberis challenged MAC-T cells.

Figure 4. The active CaN/NFAT signaling pathway is attenuated by taurine in S. uberis challenged MAC-T cells. (A–G) MAC-T cells were pretreated with β-alanine for 1 h and then administrated taurine for 24 h. Subsequently, cells were infected with S. uberis in mid-exponential phase at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 10 for 4 h at 37°C. (A,B) The activities of CaN and the concentration of CaM were determined by commercial kits. (C) The protein expression of GSK-3β and its phosphorylation level p-GSK-3β were determined by Western blot. Lines 1–8 represent control, S. uberis, taurine, S. uberis + taurine, β-alanine, β-alanine + taurine, β-alanine + S. uberis, β-alanine + taurine + S. uberis, respectively. To confirm equal protein loading, blots were re-probed with an antibody against GADPH. Results of statistical analysis for p-GSK-3β (D) and GSK-3β (E) compared to GADPH. (F) The translocation status of NFAT into nucleus was detected by confocal microscopy. Blue light: for the nucleus; Green light: for the NFAT labeled by GFP; Merge: images that the two lights simultaneously display. C, control; S, S. uberis; T, taurine; S + T, S. uberis + taurine; β, β-alanine; β + T, β-alanine + taurine; β + S, β-alanine + S. uberis; β + T + S, β-alanine + taurine + S. uberis. (G,H) The contents of NFAT in nucleoprotein were detected by electrochemistry. The pictorial diagram (G) and statistic results (H). Statistic results are representative of three independent experiments. Data are presented as the means ± SEM. *(P < 0.05) = significantly different between the indicated groups.

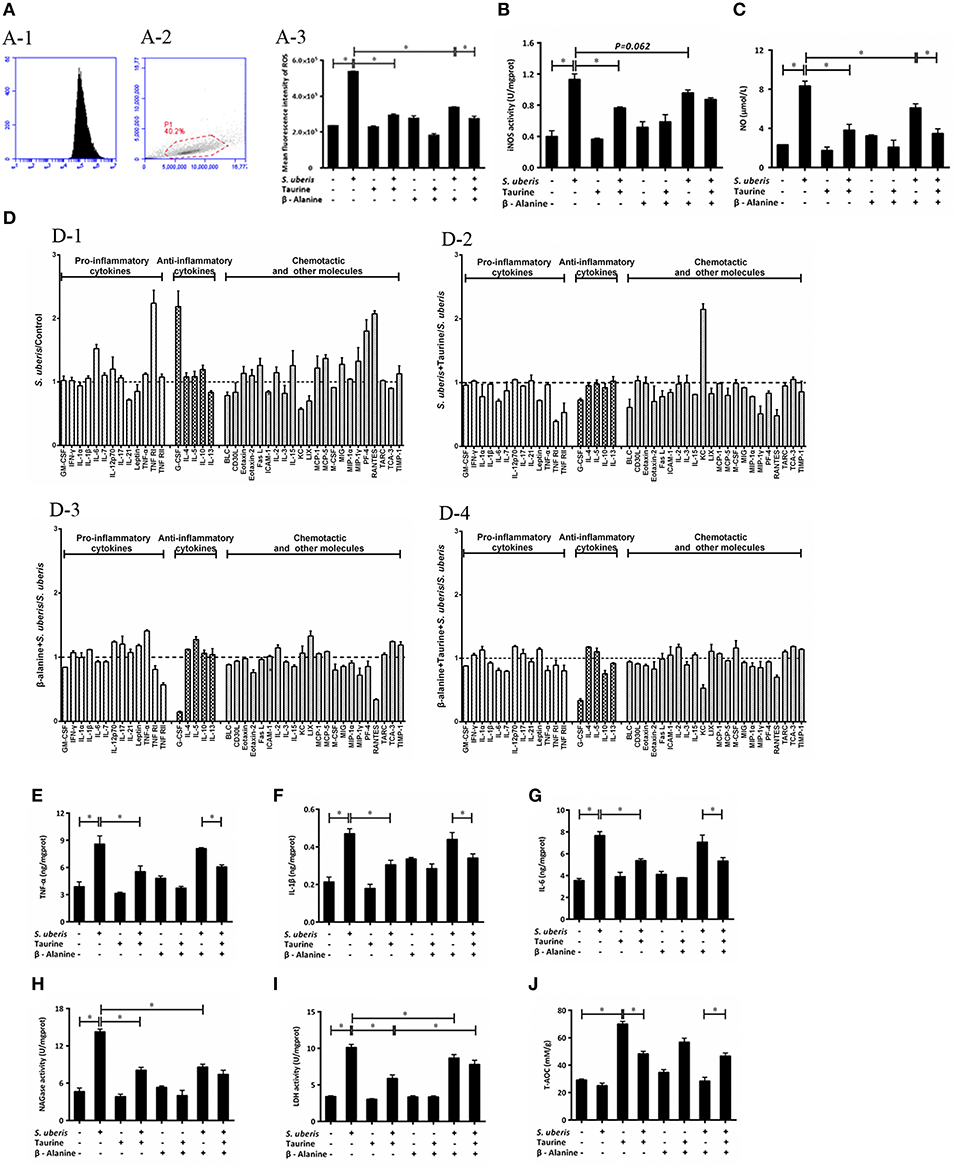

Inflammatory mediators and cell injury indexes were measured. Flow cytometry detection via staining cells with 10 μM DCFH-DA indicate that intracellular ROS level increased after S. uberis co-culture with MAC-T cells (Figures 5A-1,A-2); significant differences were observed when bacterial challenged groups were compared to controls (P < 0.05). Pre-treatment with taurine or/and β-alanine decreased its production when compared with the S. uberis challenged group (P < 0.05). No significant difference was seen between the taurine + S. uberis and β-alanine + taurine + S. uberis groups (P > 0.05) (Figure 5A-3).

Figure 5. Effect of taurine on inflammatory response in S. uberis challenged MAC-T cells. MAC-T cells were pretreated with β-alanine for 1 h and then administrated taurine for 24 h. Subsequently, cells were infected with S. uberis in mid-exponential phase at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 10 for 4 h at 37°C. (A) Intracellular ROS content was evaluated by staining cells with DCFH-DA. 10,000 cells per sample were analyzed using CellQuest Pro acquisition and analysis software. Gating of the cell population (A-1), pictorial diagram (A-2) and statistic results (A-3). (B,C) The activities or levels of iNOS and NO in cells or supernatant were determined using commercial kits. (B): iNOS activity, (C): NO level. Statistic results are representative of three independent experiments. Data are presented as the means ± SEM. *(P < 0.05) = significantly different between the indicated groups. (D) Cell culture supernatants were collected and 300 μg of protein of each sample were used for cytokine expression using a Quantibody Mouse Inflammation Array 1 kit. The array was designed to quantitatively detect 40 cytokines (pro-inflammatory cytokines, anti-inflammatory cytokines, chemotactic and other molecules) simultaneously. The mean fluorescence intensities (median values) of control groups or treated groups were chosen as standards. For (D-1): S. uberis vs. Control; (D-2): S. uberis + Taurine vs. S. uberis; (D-3): β-alanine + S. uberis vs. S. uberis and (D-4): β-alanine + Taurine + S. uberis vs. S. uberis. Statistic results are representative of three independent experiments. (E–G) The production of cytokines in the supernatant was measured by ELISA commercial kits. For (E): TNF-α; (F): IL-1β and (G): IL-6. (H,I) The activities NAGase and LDH in supernatant were determined using commercial kits. (H): NAGase activity and (I): LDH activity. (J) The cells were used to detect the ability of antioxidant capacity (T-AOC) by a commercial kit. Statistic results are representative of 3 independent experiments. Data are presented as the means ± SEM. *(P < 0.05) = significantly different between the indicated groups.

Intracellular iNOS activities and NO were detected by commercial kits. S. uberis infection significantly elevated iNOS activity; NO and taurine significantly reduced these increases (P < 0.05). β-alanine also lessened NO dramatically and iNOS activity to a lesser extent. Co-administration of β-alanine and taurine had no additive effect when compared with the taurine + S. uberis group (P > 0.05) (Figures 5B,C).

To determine the influence of taurine on the production of inflammatory cytokines/molecules, the Quantibody Mouse Inflammation Array Q1 kit was used to semi-quantitatively assay 40 cytokines/molecules. These molecules are divided into 3 groups: pro-inflammatory cytokines (13), anti-inflammatory cytokines (5) and chemotactic and other molecules in culture supernatants (22) (Figure 5D). Data indicate the secretion of the majority of these molecules (28/40) are increased (fold change > 1) 4 h after S. uberis challenge; for 12/40 molecules the fold change (>1.2) is significant. Of the 28 changed molecules, 10/13 are pro-inflammatory cytokines, 4/5 are anti-inflammatory cytokines and the rest are chemotactic and other molecules (Figure 5D-1). Taurine pre-treatment of the S. uberis infected cells results in decreased secretion of 33/40 molecules (fold change < 1), including 10/13 pro-inflammatory cytokines, 4/5 anti-inflammatory cytokines and 19/22 chemotactic and other molecules; 13 of these 33 molecules had a significant reduction (fold change < 0.8) (Figure 5D-2). In Figure 5D-3, β-alanine pre-treatment of S. uberis infected cells results in the decreased secretion of 20/40 molecules (fold change < 1), including 6/13 pro-inflammatory cytokines, 1/5 anti-inflammatory cytokines, and 13/22 chemotactic and other molecules. Only five had a significant reduction (fold change < 0.8). Twenty four molecules decreased (fold change < 1), including 8/13 pro-inflammatory cytokines, 3/5 anti-inflammatory cytokines and 13/22 chemotactic and other molecules (Figure 5D-4, where 5 had a significant reduction (fold change < 0.8). These results suggest that taurine may reduce the secretion of inflammation-associated factors induced by S. uberis in MAC-T cells while the effects of β-alanine are not so obvious compared with taurine.

In our previous studies, we focused on TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6, 3 pro-inflammatory cytokines that are expressed at elevated levels following activation of nuclear transcription factors and are closely related to the inflammatory response. In the current study, ELISA testing determined that TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 expression were all considerably up-regulated in MAC-T cells in response to S. uberis infection; the opposite results were observed in taurine pre-treatment groups compared with the S. uberis group (P < 0.05) Figures 5E–G.

The cell injury biomarkers NAGase and LDH in the cell culture supernatants were significantly higher in S. uberis infection groups. Pre-treatment with taurine or/and β-alanine down-regulated their activities (P < 0.05). There were no significant differences between the taurine + S. uberis and β-alanine + taurine + S. uberis groups for NAGase (P > 0.05) Figures 5H,I. β-alanine also did not inhibit taurine induced T-AOC increasing in S. uberis challenged cells (Figure 5J). These data indicate that taurine inhibits inflammation and cell injury in S. uberis challenged MAC-T cells.

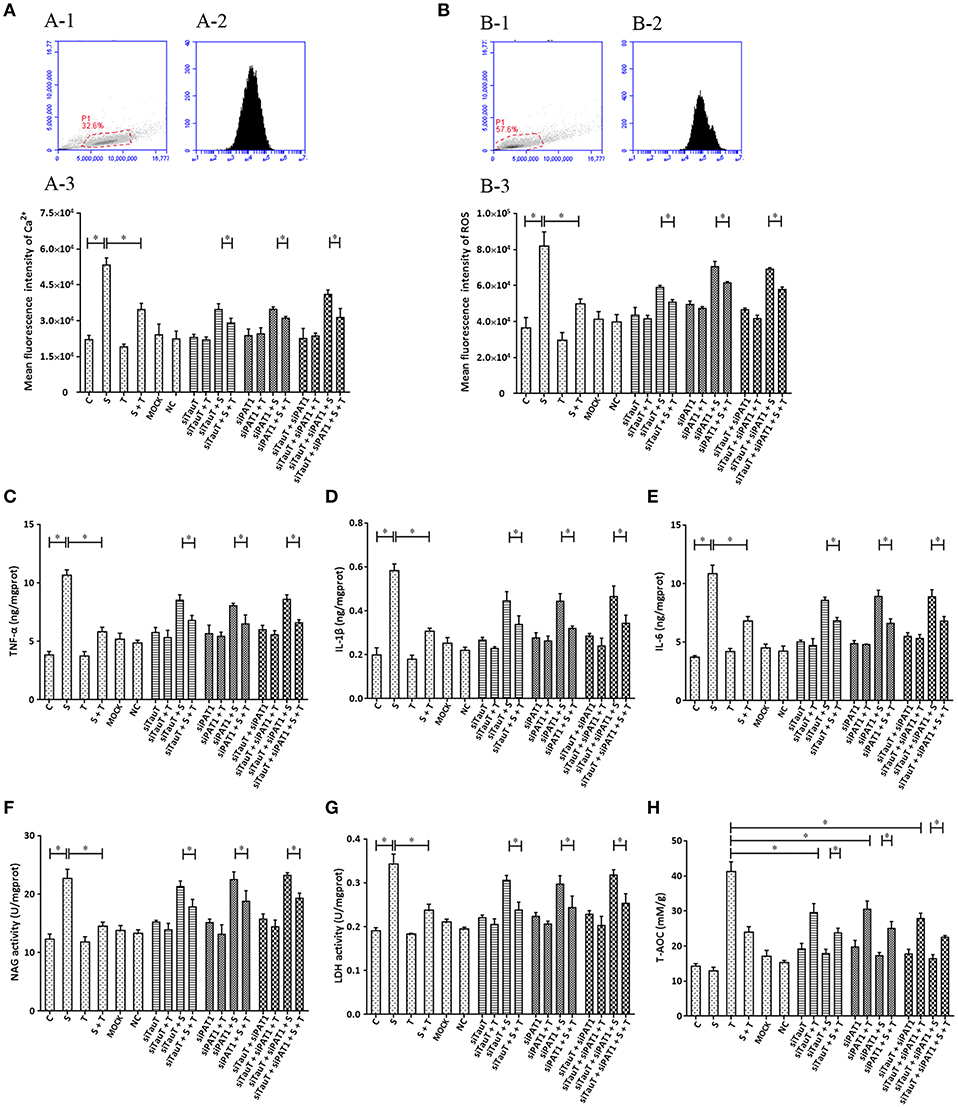

Taurine uptake across the cell membrane is via two transporters: H+-coupled PAT1 (SLC36A1) and Na+- and Cl−-dependent TauT (SLC6A6). We explored the possibility that taurine regulation of S. uberis challenged cells might not depend on entry into the cytoplasm. Cells were transfected with siTauT or/and siPAT1 to inhibit the expression of these two transporters. The results showed that cells co-cultured with siTauT or/and siPAT1 and then administrated taurine had significantly decreased intracellular Ca2+ concentrations after S. uberis challenge. The inhibition rates for siTauT, siPAT1, and siTauT + siPAT1 were 16.06, 10.85, and 23.59%, respectively (P < 0.05), lower then when taurine is directly added (34.97% (P < 0.05) Figure 6A. The inhibition rate of ROS due to taurine in S. uberis infection is 39.18% (P < 0.05). With siTauT, siPAT1, or siTauT + siPAT1, the percent inhibition is 13.96, 12.74, and 16.38%, respectively (P < 0.05) Figure 6B. In association with TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6, taurine reduced secretion after S. uberis challenge; the suppression ratio is 45.38, 47.30, and 37.17%, respectively (P < 0.05). The ratio is higher than that of cells pretreated with siTauT, siPAT1, or siTauT + siPAT1 (Figures 6C–E). Similar changes were observed regarding the activities of NAGase and LDH in supernatant (Figures 6F,G). The total intracellular antioxidant capacity (T-AOC) was determined by a commercial kit. The data established that siTauT, siPAT1, or siTauT + siPAT1 may significantly decrease the content of T-AOC in cells with taurine (P < 0.05) (Figure 6H). These data suggest that downregulated TauT and PAT1 expression reduce taurine uptake, although its inhibition related to S. uberis inflammation persists.

Figure 6. The influence of interference in the expression of TauT expression and PAT1 on the effect of taurine on inflammatory responses induced by S. uberis in MAC-T cells. MAC-T cells were transfected with the siTauT or/and siPAT1 for 72 h and then administrated taurine for 24 h. Subsequently, cells were infected with S. uberis in mid-exponential phase at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 10 for 3 h at 37°C. Intracellular Ca2+ concentration was evaluated by staining cells with Fluo-3 AM. 10,000 cells per sample were analyzed using Cell Quest Pro acquisition and analysis software. Gating of the cell population (A-1), pictorial diagram (A-2), and statistic results (A-3). (B-H) Cells were infected with S. uberis in mid-exponential phase at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 10 for 4 h at 37°C. (B) Intracellular ROS content was evaluated by staining cells with DCFH-DA. 10,000 cells per sample were analyzed using CellQuest Pro acquisition and analysis software. Gating of the cell population (B-1), pictorial diagram (B-2), and statistic results (B-3). The production of cytokines in the supernatant was measured by ELISA kits. For (C): TNF-α; (D): IL-1β and (E): IL-6. The activities NAGase and LDH in supernatant were determined using commercial kits. For (F): NAGase activity and (G): LDH activity. (H) The cells were used to detect the ability of antioxidant capacity (T-AOC) by a commercial kit. Statistic results are representative of three independent experiments. Data are presented as the means ± SEM. *(P < 0.05) = significantly different between the indicated groups.

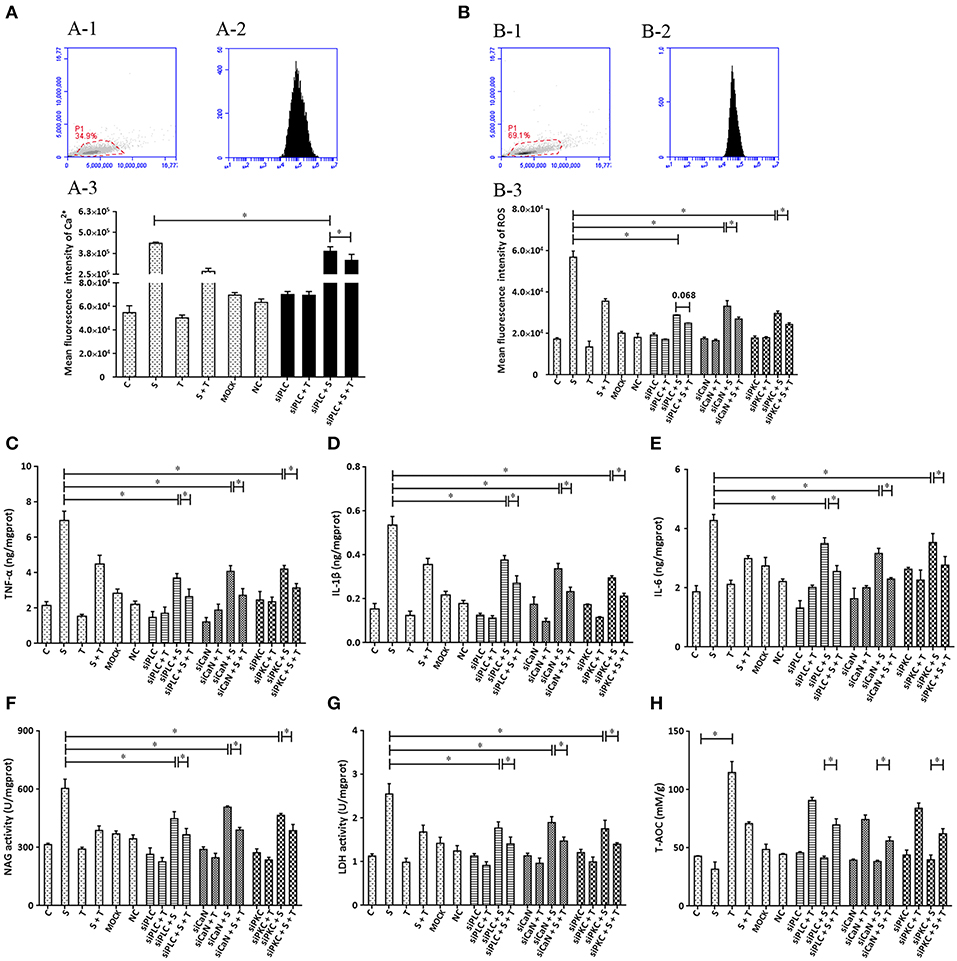

To further confirm that phosphoinositides/Ca2+ systems mediate inflammatory signals participate in the inhibition of taurine on S. uberis induced inflammation, special interfering RNA targeting to PLC (isoform PLCγ1) was used. As shown in Figure 7, siPLC reduces the increase of intracellular Ca2+ in the face of S. uberis infection (P < 0.05). Taurine also decreases the sharp elevation resulting from S. uberis challenge regardless of the presence or absence of siPLC (P < 0.05). Inhibition by siPLC was 13.92 and 38.43% (Figure 7A-3). SiPLC downregulates S. uberis induced intracellular ROS; TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6; NAGase, LDH. T-AOC is upregulated (Figures 7B–H). Pretreatment with siPLC significantly decreases the suppressive role of taurine on the inflammatory response and cell injury indexes. When comparing S. uberis challenge only groups with taurine + S. uberis groups, the suppression ratio is 37.37% for ROS (Figure 7B); 35.42% for TNF-α (Figure 7C), 33.53% for IL-1β (Figure 7D), 30.03% for IL-6 (Figure 7E); 35.92% for NAGase (Figure 7F), and 34.19% for LDH (Figure 7G). These were higher than those between the siPLC + S. uberis and siPLC + taurine + S. uberis groups. The suppression ratio was 13.49% for ROS (Figure 7B); 28.53% for TNF-α (Figure 7C), 28.10% for IL-1β (Figure 7D), 26.97% for IL-6 (Figure 7E); 18.43% for NAGase (Figure 7F), and 20.54% for LDH (Figure 7G). T-AOC was markedly improved by taurine administration (P < 0.05). S. uberis challenge attenuated these changes. Pretreatment of cells with siPLC followed by S. uberis challenge increased T-AOC levels compared to the S. uberis challenge only group (31.66 ± 6.19 vs. 41.21 ± 1.63) (P > 0.05) (Figure 7H). Taken together, these data provide evidence that PLC/phosphoinositides/Ca2+ mediated signaling pathways may participate in the anti-inflammatory role of taurine. Two key downstream adaptors, CaN and PKC, may initiate the activation of NFAT and NF-κB as target proteins for siRNA (Figures 7B–H).

Figure 7. The influence of interference in the expression of PLC, CaN, and PKC on the effect of taurine on inflammatory responses induced by S. uberis in MAC-T cells. MAC-T cells were transfected with the siPLC, siCaN, or siPKC for 72 h and then administrated taurine for 24 h. Subsequently, cells were infected with S. uberis in mid-exponential phase at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 10 for 3 h at 37°C. Intracellular Ca2+ was evaluated by staining cells with Fluo-3 AM. 10,000 cells per sample were analyzed using Cell Quest Pro acquisition and analysis software. Gating of the cell population (A-1), pictorial diagram (A-2), and statistic results (A-3). (B–H) Cells were infected with S. uberis in mid-exponential phase at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 10 for 4 h at 37°C. (B) Intracellular ROS content was evaluated by staining cells with DCFH-DA. 10,000 cells per sample were analyzed using CellQuest Pro acquisition and analysis software. Gating of the cell population (B-1), pictorial diagram (B-2), and statistic results (B-3). The production of cytokines in the supernatant was measured by ELISA kits. For (C): TNF-α; (D): IL-1β and (E): IL-6. The activities NAGase and LDH in supernatant were determined using commercial kits. (F): NAGase activity and (G): LDH activity. (H) The cells were used to detect the ability of antioxidant capacity (T-AOC) by a commercial kit. Statistic results are representative of 3 independent experiments. Data are presented as the means ± SEM. *(P < 0.05) = significantly different between the indicated groups.

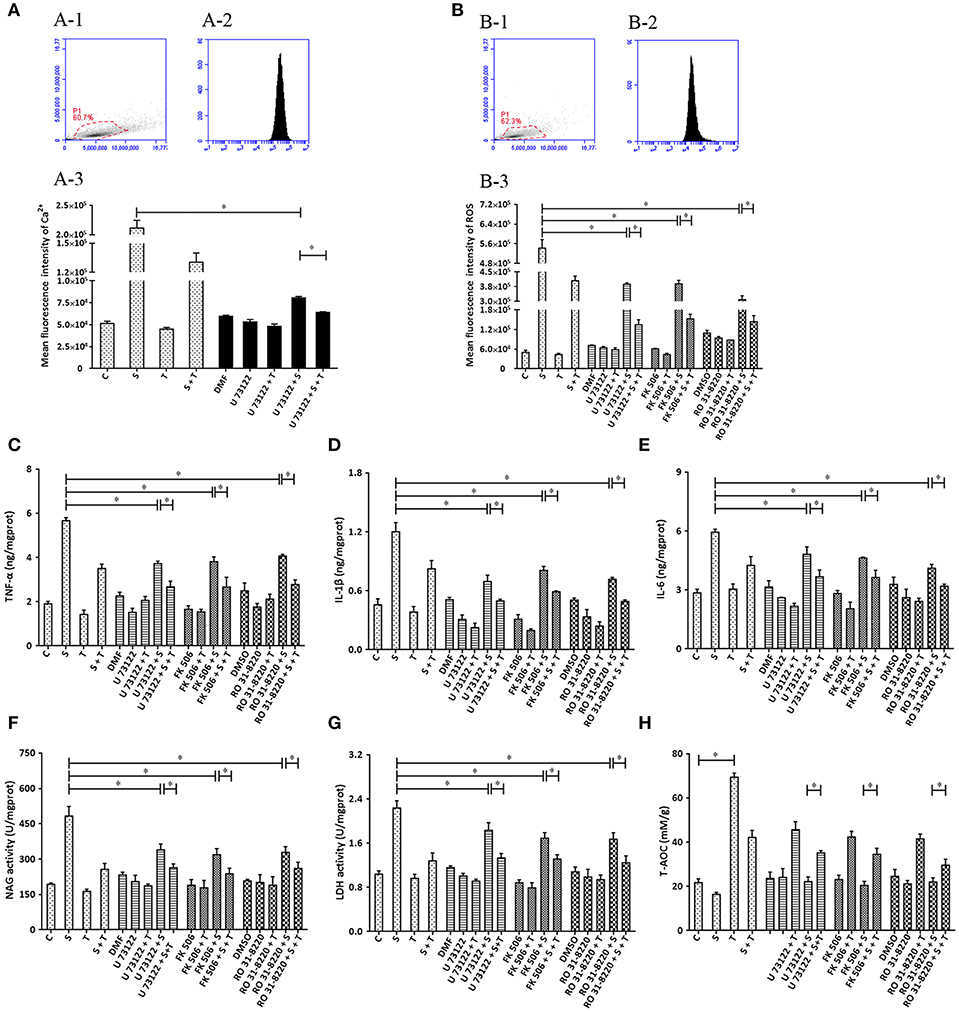

Based on the ability of siRNA to disturb the expression of target genes (PLC, CaN and PKC), various inhibitors (U 73122, FK506 and RO 31-8220) were applied and biochemical parameters related to inflammation assayed. The results indicate that U 73122 down-regulates intracellular Ca2+ elevated by S. uberis challenge. A significant difference was observed between the S. uberis challenge group and the U 73122 + S. uberis group (P < 0.05). Taurine reduced Ca2+ levels both in U 73122 pretreated and untreated S. uberis infected groups (P < 0.05) (Figure 8A). The patterns of these 3 inhibitors to inflammation and cell injury are similar to those siRNAs targeting PLC, CaN and PKC. In summary, blocking PLC, CaN, and PKC with inhibitors decreased intracellular ROS; TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6; NAGase, and LDH in cell culture supernatants. Taurine suppressed these indexes whether the inhibitors were present or not (Figures 8B–H).

Figure 8. The influence of the inhibitors of PLC (U73122), CaN (FK506), and PKC (RO31-8220) on the effect of taurine on inflammatory responses induced by S. uberis in MAC-T cells. MAC-T cells were exposed to pretreatment inhibitors (U73122, FK506, or RO31-8220) for 1 h, and then administrated taurine for 24 h. Subsequently, cells were infected with S. uberis in mid-exponential phase at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 10 for 3 h at 37°C. Intracellular Ca2+ concentration was evaluated by staining cells with Fluo-3 AM. 10,000 cells per sample were analyzed using Cell Quest Pro acquisition and analysis software. Gating of the cell population (A-1), pictorial diagram (A-2), and statistic results (A-3). (B–H) Cells were infected with S. uberis in mid-exponential phase at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 10 for 4 h at 37°C. (B) Intracellular ROS content was evaluated by staining cells with DCFH-DA. 10,000 cells per sample were analyzed using CellQuest Pro acquisition and analysis software. Gating of the cell population (B-1), pictorial diagram (B-2), and statistic results (B-3). The production of cytokines in the supernatant was measured by ELISA kits. (C): TNF-α; (D): IL-1β and (E): IL-6. NAGase and LDH in supernatant were determined using commercial kits. (F): NAGase activity and (G): LDH activity. (H) The cells were used to detect antioxidant capacity (T-AOC) by a commercial kit. Statistic results are representative of 3 independent experiments. Data are presented as the means ± SEM. *(P < 0.05) = significantly different between the indicated groups.

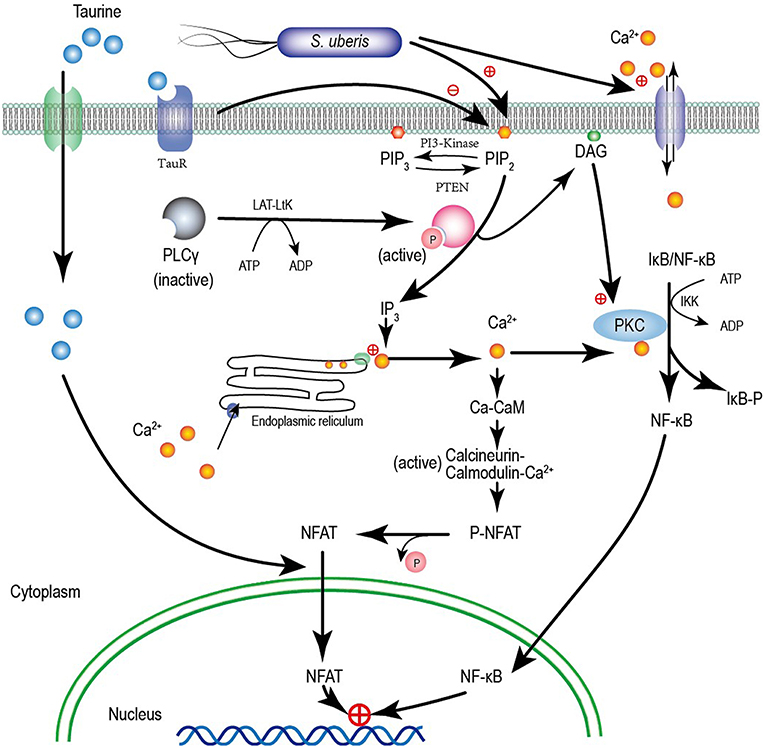

Calcium has long been considered the most common message carrier in cells (38–40). The data presented here are consistent with our previous study demonstrating significantly elevated cytoplasmic Ca2+ by S. uberis infection (14). This is associated with the activation of PLC and hydrolyzation PIP2 to produce IP3 which bonds to Ca2+ channels allowing Ca2+ entry (41, 42). We found that the expression and activation of PLCγ1 the main isoform of PLC in epithelial cells (43) and cytoplasmic IP3 increases after S. uberis challenge. NCX1 which allows bidirectional Ca2+ crossing of cell membranes is unaltered. Taurine protects against various infection induced injuries and may be linked to the regulatory role of taurine in cytoplasmic Ca2+ levels. Taurine significantly decreases intracellular Ca2+, but its competitive inhibitor β-alanine has no effect on the down-regulation of taurine. Although special siRNA targeting to TauT and PAT1 have been used, taurine still significantly decreases intracellular Ca2+ concentration after S. uberis challenge These data indicate that taurine does not need to enter cytoplasm to regulate intracellular Ca2+. A model for taurine regulating the S. uberis-induced inflammatory responses via the phosphoinositides/Ca2+ systems was showed in Figure 9.

Figure 9. A model for taurine regulating the S. uberis induced inflammatory responses via the phosphoinositides/Ca2+ systems which followed by the Ca2+-PKCα-NF-κB, and Ca2+-CaM-CaN-NFAT signaling pathways.

PIs are a minority family of acidic phospholipids in cell membranes. They are known as lipid regulators of membrane proteins. The signature PI attracts a specific complement of functionally important, loosely attached, peripheral membrane proteins that cooperate with other signal recognition proteins (44). PIP2 and PIP3 are 2 principal phosphoinositides. Regulation of their levels at the plasma membrane plays a critical role in the pathogenic mechanism of some bacterial pathogens. Enteropathogenic Escherichia coli (EPEC) infection subverts PIP2 and PIP3 and modulates cell death and innate immunity (45). S. uberis challenge significantly increases PIP3 levels and decreases PIP2. PLC, which breaks down PIP2 to IP3 and phosphatidic acid, and by phosphorylation of the inositol ring in the 3′ position by PI3K, generates PIP3 in the infection site. Our data confirms detection of PLC and IP3. The expression and phosphorylation of PI3K and PTEN, which are key enzymes that mediate the switch of PIP2 and PIP3 are elevated after S. uberis infection. This suggests complete metabolism of phosphoinositides by MAC-T cells. Pretreatment with taurine increases PIP2 and decreases PIP3 with S. uberis challenge. PI3K and PTEN levels are also moderated by taurine. We assume that taurine transfers the extracellular nutrient signal to trigger intercellular innate immunity.

NF-κB is an important transcription factor regulating expression of many genes. Upon activation by various factors, NF-κB translocates to the nucleus (46). Our observations suggest that NF-κB activity is up-regulated as a result of S. uberis infection. Employing immunofluorescence analysis, we detected increased NF-κB in nuclear regions. Utilizing DNA-Ag nanocluster molecular beacons and exonuclease III-assisted signals, the DNA binding signal was increased for only activated NF-κB. The phosphorylation levels of IKKα and IκBα were elevated in MAC-T cells. Mean IκBα was activated by IKKα; IκBα detaches from the NF-κB dimer which is then free to enter the nucleus. Protein kinase C (PKC, EC 2.7.11.13), is a family of protein kinase enzymes. It is activated by Ca2+ signaling and regulates metabolism, cell division, apoptosis and other cell functions. Recently, it has been shown that PKC is closely linked to the inflammatory response through Ca2+ via the influence of NF-κB. PKC-α is unique within the PKC family because its primary mode of regulation involves its interaction with the cell membrane. It plays a vital role in epithelial tissue (47, 48). Taurine negatively affects the concentration and activity of PKCα in S. uberis challenged bovine MECs. It seems that the PLCγ1-IP3- Ca2+-PKCα-NF-κB signaling pathway is involved the bioprocesses of S. uberis infection and the regulatory role of taurine.

In contrast with NF-κB, NFAT is a multiply faceted transcription factor involved in inflammatory regulation. The precise roles of NFAT are pathogen and cell type dependent. Zanoni et al. found that CD14 signaling triggers the CaN/NFAT pathway in DCs but not in macrophages strongly indicating that NFAT has distinct roles in different cells (49). Our previous study reported that in mouse MECs, S. uberis provokes NFAT activation and taurine alleviates this process. This process is connected with alteration of cytoplasmic Ca2+. This phenomenon is validated in the current study in MAC-T cells. CaN and GSK-3, which are known to coordinate the import and export of NFAT, were detected. They were markedly activated by S. uberis; taurine subverts these changes. CaN and GSK-3 take part in inflammatory regulation. The enhancing role of GSK-3 kinases in CaN signaling has been reported in Staphylococcus aureus and other inflammatory diseases. CaM, a bridge protein between Ca2+ signaling and Ca2+ regulating proteins/enzymes, had a similar change. Taken together, the PLCγ1-IP3- Ca2+-CaM-CaN-NFAT signaling pathway may mediate taurine regulation of S. uberis infection.

Transcription factors NF-κB and NFAT initiate the inflammatory cascade characterized by the overexpression ROS, RNS, cytokines and other inflammatory mediators. The induced cell damage accompanies the elimination of pathogens if uncontrolled. Our results suggest that intracellular ROS, iNOS, and NO are significantly increased after S. uberis challenge. Taurine pretreatment significantly downregulates their production in MAC-T cells. Forty cytokines/molecules in cell culture supernatants were simultaneously assayed by protein microarray. S. uberis elevated the expression of most pro-inflammatory cytokines (10/13), anti-inflammatory cytokines (4/5) and taurine largely inhibited these changes. TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6, 3 important pro-inflammatory cytokines, are widely accepted as downstream factors subsequent to pathogen infection and demonstrated a similar pattern. These data indicate that the inflammatory responses were fully activated following S. uberis targeting and excitation of PIs/Ca2+ systems. Taurine alleviated these bioprocess as confirmed by the detection of the cell injury biomarkers NAGase and LDH.

The results and phenomena described above denote an integration of all involved active signaling pathways. To ensure that phosphoinositids/Ca2+ systems play an important role in taurine regulation of the inflammatory response associated with S. uberis infection and the importance of PLCγ1-IP3-Ca2+-PKCα-NF-κB, and PLCγ1-IP3- Ca2+-CaM-CaN-NFAT signaling pathways, siPLC, siCaN, and siPKC were used to inhibit the two signaling pathways through interference with the expression of the target proteins. SiPLC decreased intracellular Ca2+ resulting from S. uberis challenge. Taurine performed this function whether or not siPLC was present. Inhibitory rates were lower when siPLC was present. ROS, cytokines, NAGase, and LDH had similar patterns. There were no significant differences in the regulatory roles of taurine in siPLC, siCaN, and siPKC systems. The phosphoinositides/Ca2+ systems participated in taurine regulating S. uberis-induced inflammation. Both Ca2+-PKCα-NF-κB, and Ca2+-CaM-CaN-NFAT mediated this process. It was further confirmed by the use of three inhibitors of U73122, FK506, and RO31-8220 which restrained the activity or function of PLC, CaN, and PKC, respectively.

In summary, S. uberis induced inflammatory responses are elicited through lipid products mainly by IP3 that acts on membrane phosphoinositides and activate the Ca2+-PKCα-NF-κB, and Ca2+-CaM-CaN-NFAT signaling pathways. There is negative regulation of these inflammatory responses by taurine via the phosphoinositides/Ca2+ systems. These data augment our understanding of the mechanisms of multifunctional nutrient taurine attenuation of the inflammatory responses causing by S. uberis infection, and provides theoretical support for the prevention of this disease.

Requests to access the datasets should be directed to Miao Jinfeng, bWlhb2ppbmZlbmdAbmphdS5lZHUuY24=.

ML and PX performed the whole experiments and wrote the manuscript. YX and XH participated in the design of this study. YX and ZW provided assistance for data acquisition, data analysis, and statistical analysis. WR collected important background information. VP performed manuscript review. JM carried out the definition of intellectual content and provided the support platform and funding. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

This project was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 31672515 and 31572546) and the Project Funded by the Priority Academic Program Development of Jiangsu Higher Education Institutions.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The authors express their thanks to Dr. Howard Gelberg (Oregon State University) for manuscript editing.

1. Gilbert FB, Cunha P, Jensen K, Glass EJ, Foucras G, Robert-Granié C, et al. Differential response of bovine mammary epithelial cells to Staphylococcus aureus or Escherichia coli agonists of the innate immune system. Vet Res. (2013) 44:40. doi: 10.1186/1297-9716-44-40

2. Johnzon C-F, Artursson K, Söderlund R, Guss B, Rönnberg E, Pejler G. Mastitis pathogens with high virulence in a mouse model produce a distinct cytokine profile in vivo. Front Immunol. (2016) 7:368. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2016.00368

3. Almeida RA, Luther DA, Kumar SJ, Calvinho LF, Bronze MS, Oliver SP. Adherence of Streptococcus uberis to bovine mammary epithelial cells and to extracellular matrix proteins. J Vet Med Ser B. (1996) 43:385–92. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0450.1996.tb00330.x

4. Almeida RA, Dunlap JR, Oliver SP. Binding of host factors influences internalization and intracellular trafficking of Streptococcus uberis in bovine mammary epithelial cells. Vet Med Int. (2010) 2010:319192. doi: 10.4061/2010/319192

5. Tamilselvam B, Almeida RA, Dunlap JR, Oliver SP. Streptococcus uberis internalizes and persists in bovine mammary epithelial cells. Microb Pathog. (2006) 40:279–85. doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2006.02.006

6. Hillerton JE, Berry EA. Treating mastitis in the cow-a tradition or an archaism. J Appl Microbiol. (2005) 98:1250–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2005.02649.x

7. Silvestrini P, Beccaría C, Pereyra EAL, Renna MS, Ortega HH, Calvinho LF, et al. Intramammary inoculation of panax ginseng plays an immunoprotective role in Staphylococcus aureus infection in a murine model. Res Vet Sci. (2017) 115:211–20. doi: 10.1016/j.rvsc.2017.05.010

8. Boulanger D, Brouillette E, Jaspar F, Malouin F, Mainil J, Bureau F, et al. Helenalin reduces Staphylococcus aureus infection in vitro and in vivo. Vet Microbiol. (2007) 119:330–8. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2006.08.020

9. Grimble RF. The effects of sulfur amino acid intake on immune function in humans. J Nutr. (2006) 136:1660S–5S. doi: 10.1093/jn/136.6.1660S

10. Erdem A, Sevgili AM, Akbiyik F, Atilla P, Cakar N, Balkanci ZD, et al. The effect of taurine on mesenteric blood flow and organ injury in sepsis. Amino Acids. (2008) 35:403–10. doi: 10.1007/s00726-007-0622-0

11. Nam S-Y, Kim H-M, Jeong H-J. The potential protective role of taurine against experimental allergic inflammation. Life Sci. (2017) 184:18–24. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2017.07.007

12. De Paepe B, Martin J-J, Herbelet S, Jimenez-Mallebrera C, Iglesias E, Jou C, et al. Activation of osmolyte pathways in inflammatory myopathy and Duchenne muscular dystrophy points to osmoregulation as a contributing pathogenic mechanism. Lab Invest. (2016) 96:872–84. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.2016.68

13. Zheng L, Xu Y, Lu J, Liu M, Bin D, Miao J, et al. Variant innate immune responses of mammary epithelial cells to challenge by Staphylococcus aureus, Escherichia coli and the regulating effect of taurine on these bioprocesses. Free Radic Biol Med. (2016) 96:166–80. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2016.04.022

14. Dai B, Zhang J, Liu M, Lu J, Zhang Y, Xu Y, et al. The role of Ca2+ mediated signaling pathways on the effect of taurine against Streptococcus uberis infection. Vet Microbiol. (2016) 192:26–33. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2016.06.008

15. Li B, Xi P, Wang Z, Han X, Xu Y, Zhang Y, et al. PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling pathway participates in Streptococcus uberis-induced inflammation in mammary epithelial cells in concert with the classical TLRs/NF-κB pathway. Vet Microbiol. (2018) 227:103–11. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2018.10.031

16. Tomi M, Tajima A, Tachikawa M, Hosoya K. Function of taurine transporter (Slc6a6/TauT) as a GABA transporting protein and its relevance to GABA transport in rat retinal capillary endothelial cells. Biochim Biophys Acta Biomembranes. (2008) 1778:2138–42. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2008.04.012

17. Nielsen CU, Bjerg M, Ulaganathan N, Holm R. Oral and intravenous pharmacokinetics of taurine in sprague-dawley rats: the influence of dose and the possible involvement of the proton-coupled amino acid transporter, PAT1, in oral taurine absorption. Physiol Rep. (2017) 5:e13467. doi: 10.14814/phy2.13467

18. Militante JD, Lombardini JB. Pharmacological characterization of the effects of taurine on calcium uptake in the rat retina. Amino Acids. (1998) 15:99–108. doi: 10.1007/BF01345283

19. De Luca A, Pierno S, Camerino DC. Taurine: the appeal of a safe amino acid for skeletal muscle disorders. J Transl Med. (2015) 13:243. doi: 10.1186/s12967-015-0610-1

20. Christensen MG, Fagerberg SK, de Bruijn PI, Bjaelde RG, Jakobsen H, Leipziger J, et al. [Ca2+]i oscillations and IL-6 release induced by α-hemolysin from escherichia coli require P2 receptor activation in renal epithelia. J Biol Chem. (2015) 290:14776–84. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.639526

21. Xuan NT, Shumilina E, Matzner N, Zemtsova IM, Biedermann T, Goetz F, et al. Ca2+-dependent functions in peptidoglycan-stimulated mouse dendritic cells. Cell Physiol Biochem. (2009) 24:167–76. doi: 10.1159/000233243

22. Balla T. Phosphoinositides: tiny lipids with giant impact on cell regulation. Physiol Rev. (2013) 93:1019–137. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00028.2012

23. Bierne H, Gouin E, Roux P, Caroni P, Yin HL, Cossart P. A role for cofilin and LIM kinase in Listeria-induced phagocytosis. J Cell Biol. (2001) 155:101–12. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200104037

24. Vessichelli M, Mariggiò S, Varone A, Zizza P, Di Santo A, Amore C, et al. The natural phosphoinositide derivative glycerophosphoinositol inhibits the lipopolysaccharide-induced inflammatory and thrombotic responses. J Biol Chem. (2017) 292:12828–41. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M116.773861

25. Pizarro-Cerdá J, Cossart P. Subversion of phosphoinositide metabolism by intracellular bacterial pathogens. Nat Cell Biol. (2004) 6:1026–33. doi: 10.1038/ncb1104-1026

26. Yang S, Huang X-Y. Ca2+ influx through L-type Ca2+ channels controls the trailing tail contraction in growth factor-induced fibroblast cell migration. J Biol Chem. (2005) 280:27130–7. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M501625200

27. Zhu X, Jiang M, Peyton M, Boulay G, Hurst R, Stefani E, et al. trp, a novel mammalian gene family essential for agonist-activated capacitative Ca2+ entry. Cell. (1996) 85:661–71. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81233-7

28. Dai G, Yu H, Kruse M, Traynorkaplan A, Hille B. Osmoregulatory inositol transporter SMIT1 modulates electrical activity by adjusting PI(4,5)P2 levels. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. (2016) 113:E3290. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1606348113

29. Qian X, Vinnakota S, Edwards C, Sarkar HK. Molecular characterization of taurine transport in bovine aortic endothelial cells. Biochim Biophys Acta. (2000) 1509:324–34. doi: 10.1016/S0005-2736(00)00315-1

30. Liu G, Fan G, Guo G, Kang W, Wang D, Xu B, et al. FK506 Attenuates the inflammation in rat spinal cord injury by inhibiting the activation of NF-κB in microglia cells. Cell Mol Neurobiol. (2017) 37:843–55. doi: 10.1007/s10571-016-0422-8

32. Chen WQ, Jin H, Nguyen M, Carr J, Lee YJ, Hsu CC, et al. Role of taurine in regulation of intracellular calcium level and neuroprotective function in cultured neurons. J Neurosci Res. (2001) 66:612–9. doi: 10.1002/jnr.10027

33. Kumari N, Prentice H, Wu J-Y. Taurine and its neuroprotective role. Adv Exp Med Biol. (2013) 775:19–27. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4614-6130-2_2

34. Ye H-B, Shi H-B, Yin S-K. Mechanisms underlying taurine protection against glutamate-induced neurotoxicity. Can J Neurol Sci. (2013) 40:628–34. doi: 10.1017/S0317167100014840

35. Feske S. Calcium signalling in lymphocyte activation and disease. Nat Rev Immunol. (2007) 7:690–702. doi: 10.1038/nri2152

36. Sasaki-Osugi K, Imoto C, Takahara T, Shibata H, Maki M. Nuclear ALG-2 protein interacts with Ca2+ homeostasis endoplasmic reticulum protein (CHERP) Ca2+-dependently and participates in regulation of alternative splicing of inositol trisphosphate receptor type 1 (IP3R1) pre-mRNA. J Biol Chem. (2013) 28:33361–75. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.497479

37. Fric J, Zelante T, Wong AYW, Mertes A, Yu H-B, Ricciardi-castagnoli P. NFAT control of innate immunity. Blood. (2012) 120:1380–9. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-02-404475

38. Pollak AJ, Liu C, Gudlur A, Mayfield JE, Dalton ND, Gu Y, et al. A secretory pathway kinase regulates sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca homeostasis and protects against heart failure. Elife. (2018) 7:e41378. doi: 10.7554/eLife.41378

39. Luganini A, Di Nardo G, Munaron L, Gilardi G, Fiorio Pla A, Gribaudo G. Human cytomegalovirus US21 protein is a viroporin that modulates calcium homeostasis and protects cells against apoptosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. (2018) 115:E12370–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1813183115

40. Marchi S, Corricelli M, Branchini A, Vitto VAM, Missiroli S, Morciano G, et al. Akt-mediated phosphorylation of MICU1 regulates mitochondrial Ca levels and tumor growth. EMBO J. (2019) 38:e99435. doi: 10.15252/embj.201899435

41. Lee S, Kim G-L, Kim NY, Kim S-J, Ghosh P, Rhee D-K. ATF3 stimulates IL-17A by regulating intracellular Ca/ROS-dependent IL-1β activation during infection. Front Immunol. (2018) 9:1954. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.01954

42. Xu S, Huo J, Lee K-G, Kurosaki T, Lam K-P. Phospholipase Cγ2 is critical for Dectin-1-mediated Ca2+ flux and cytokine production in dendritic cells. J Biol Chem. (2009) 284:7038–46. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M806650200

43. Cho I-H, Gong J-H, Kang M-K, Lee E-J, Park JHY, Park S-J, et al. Astragalin inhibits airway eotaxin-1 induction and epithelial apoptosis through modulating oxidative stress-responsive MAPK signaling. BMC Pulm Med. (2014) 14:122. doi: 10.1186/1471-2466-14-122

44. Schink KO, Tan K-W, Stenmark H. Phosphoinositides in control of membrane dynamics. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. (2016) 32:143–71. doi: 10.1146/annurev-cellbio-111315-125349

45. Sason H, Milgrom M, Weiss AM, Melamed-Book N, Balla T, Grinstein S, et al. Enteropathogenic Escherichia coli subverts phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate and phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-trisphosphate upon epithelial cell infection. Mol Biol Cell. (2009) 20:544–55. doi: 10.1091/mbc.e08-05-0516

46. Hoesel B, Schmid JA. The complexity of NF-κB signaling in inflammation and cancer. Mol Cancer. (2013) 12:86. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-12-86

47. Rosson D, O'Brien TG, Kampherstein JA, Szallasi Z, Bogi K, Blumberg PM, et al. Protein kinase C-alpha activity modulates transepithelial permeability and cell junctions in the LLC-PK1 epithelial cell line. J Biol Chem. (1997) 272:14950–3. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.23.14950

48. Mullin JM, Laughlin K V, Ginanni N, Marano CW, Clarke HM, Peralta Soler A. Increased tight junction permeability can result from protein kinase C activation/translocation and act as a tumor promotional event in epithelial cancers. Ann N Y Acad Sci. (2000) 915:231–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2000.tb05246.x

Keywords: taurine, phosphoinositides, Ca2+, Streptococcus uberis, inflammation

Citation: Li M, Xi P, Xu Y, Wang Z, Han X, Ren W, Phouthapane V and Miao J (2019) Taurine Attenuates Streptococcus uberis-Induced Bovine Mammary Epithelial Cells Inflammation via Phosphoinositides/Ca2+ Signaling. Front. Immunol. 10:1825. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.01825

Received: 03 June 2019; Accepted: 18 July 2019;

Published: 07 August 2019.

Edited by:

Fabrizio Ceciliani, University of Milan, ItalyReviewed by:

Stefano Rocca, University of Sassari, ItalyCopyright © 2019 Li, Xi, Xu, Wang, Han, Ren, Phouthapane and Miao. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Jinfeng Miao, bWpmMTcxNjQ3QDEyNi5jb20=

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.