- 1Department of Chemical and Biomedical Engineering, Florida State University, Tallahassee, FL, United States

- 2Institute of Molecular Biophysics, Florida State University, Tallahassee, FL, United States

- 3Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry, Florida State University, Tallahassee, FL, United States

Human mesenchymal stem cells (hMSCs) are the most commonly-tested adult stem cells in cell therapy. While the initial focus for hMSC clinical applications was to exploit their multi-potentiality for cell replacement therapies, it is now apparent that hMSCs empower tissue repair primarily by secretion of immuno-regulatory and pro-regenerative factors. A growing trend in hMSC clinical trials is the use of allogenic and culture-expanded cells because they are well-characterized and can be produced in large scale from specific donors to compensate for the donor pathological condition(s). However, donor morbidity and large-scale expansion are known to alter hMSC secretory profile and reduce therapeutic potency, which are significant barriers in hMSC clinical translation. Therefore, understanding the regulatory mechanisms underpinning hMSC phenotypic and functional property is crucial for developing novel engineering protocols that maximize yield while preserving therapeutic potency. hMSC are heterogenous at the level of primary metabolism and that energy metabolism plays important roles in regulating hMSC functional properties. This review focuses on energy metabolism in regulating hMSC immunomodulatory properties and its implication in hMSC sourcing and biomanufacturing. The specific characteristics of hMSC metabolism will be discussed with a focus on hMSC metabolic plasticity and donor- and culture-induced changes in immunomodulatory properties. Potential strategies of modulating hMSC metabolism to enhance their immunomodulation and therapeutic efficacy in preclinical models will be reviewed.

Background

Human mesenchymal stem or stromal cells (hMSCs) are the most commonly-tested adult stem cells in experimental cell therapy and have been used in more than 50% of clinical trials using stem cells since 2000. Clinically, the most beneficial aspects of hMSCs are their multilineage differentiation for damage tissue replacement and their ability to empower tissue repair by secretion of immuno-regulatory and pro-regenerative factors. Clinical applications of hMSC-based therapy initially exploited their multi-potentiality but increasingly focused on their secretion of immunomodulatory and trophic factors. In this immunoregulatory scenario, hMSCs promote tissue regeneration by coordinating an anti-inflammatory response through communication with the host's inflammatory microenvironment, making hMSC logical candidates for the treatment of immune disorders and inflammatory diseases. In contrast to the promising results from preclinical studies and small-scale clinical trials, the clinical outcomes using manufactured hMSC have been inconsistent and suboptimal (1–3). The close scrutiny of the discrepant outcome from these studies suggests that culture expansion, cryopreservation, and inappropriate delivery routes and dosage, are major factors that adversely influence hMSC's therapeutic efficacy (1, 4). For example, in graft-vs.-host disease, 1-year survival for patients receiving hMSC at passages 1–2 was 75% in contrast to 21% using hMSC at passages 3–4 (5). In clinical application, hMSC therapeutics are often cryobanked as “off-the-shelf” products prior to transfusion. However, cryopreservation is known to reduce hMSC immunomodulatory properties as a result of cellular stress such as cellular acidosis and metabolic uncoupling induced during freezing and thaw cycles (6, 7). It is worth noting that many of these functional changes are not readily reflected in the assessment of the minimal criterial and potency assays, suggesting the need for the identification of additional surrogate markers and regulatory pathways that can be readily assessed, and modulated to restore hMSC therapeutic potency.

This immunoregulatory function is achieved through rapid hMSC phenotype polarization and sustained production of immunoregulatory factors in response to inflammatory stimuli, which requires cellular plasticity and metabolic fitness to enable this response (8). The metabolic fitness of hMSCs is dependent on donor age and morbidity, and can be significantly altered by culture conditions imposed on the cells during in vitro expansion. Each of these factors, and probably other, currently unknown factors, can reduce hMSC immunomodulatory capacity and, therefore, reduce their therapeutic potency. A typical clinical dose of hMSCs is on the order of tens- to hundreds- of millions of cells per patient and, with hMSCs being approved for use in an ever-expanding number of clinical indications, it is estimated 300 trillion (300 × 1012) hMSCs will be needed annually by 2030 (9, 10). Current engineering protocols isolate hMSCs from adult donors and expand them under nutrient-rich conditions that significantly promote proliferation but ultimately and inadvertently reduce stemness and therapeutic potency. To compensate for the culture-induced decline of hMSC therapeutics potency, non-genetic preconditioning such as hypoxia pretreatment or 3D culture has demonstrated significant potential in restoring hMSC properties (1). To better preserve hMSC property during cryopreservation, hydrogen peroxide preconditioning has also been shown to enhance adipose derived stem cells (ASCs) resistance and survival under oxidative stress (7). While many of these preconditioning strategies have demonstrated effectiveness in restoring hMSC functional properties, the regulatory mechanism remains to be fully understood for widespread implementation in hMSC manufacturing and translation (11).

Among the core pathways to improving hMSC function, metabolism has emerged as an important hub. In their native environment, hMSCs are present in a quiescent state characterized by low proliferation and high multi-potentiality, which is maintained throughout adult life. In this state, stem cells appear to be primarily glycolytic, with “young” mitochondria maintained by active autophagy and mitophagy (12, 13). However, numerous studies show that transferring hMSC into the nutrient-rich artificial culture environment that promotes rapid proliferation reconfigures their central energy metabolism to become significantly more dependent on oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) to support the rapid proliferation (14, 15). The high OXPHOS-fueled metabolic profile also results in accumulation of cytotoxic metabolic byproducts, including reactive oxygen species (ROS) (16), that reduce the basal autophagy and mitophagy rate while simultaneously increasing the fraction of senescent cells with reduced clinical potency (17). Similar metabolic alterations have been reported for hMSC undergoing large-scale expansion in bioreactor systems (18). The influence of these metabolic changes on hMSC functional properties has just begun to be revealed. Beyond providing cells with building blocks and energy source to power cellular processes, the energy metabolism and intermediate metabolites play important roles in shaping cellular functional properties (19). Therefore, a clearer understanding of how hMSC metabolism is affected by long-term culture and how specific metabolic states impact immunomodulatory function may be the missing link between engineering practices for expansion and consistent, predictable outcomes in hMSC-based therapies. This review focuses on the role of energy metabolism in regulating hMSC immunomodulatory properties and discusses its implication for hMSC large-scale manufacturing and therapy. The specific characteristics of hMSC metabolism, culture-induced metabolic changes, and the metabolism underpinning hMSC's immunomodulatory properties will be discussed. We will also review and discuss recent studies on hMSC metabolic modulation of their immunomodulatory properties and therapeutic efficacy.

hMSCs Metabolic Plasticity and Culture-Induced Metabolic Changes

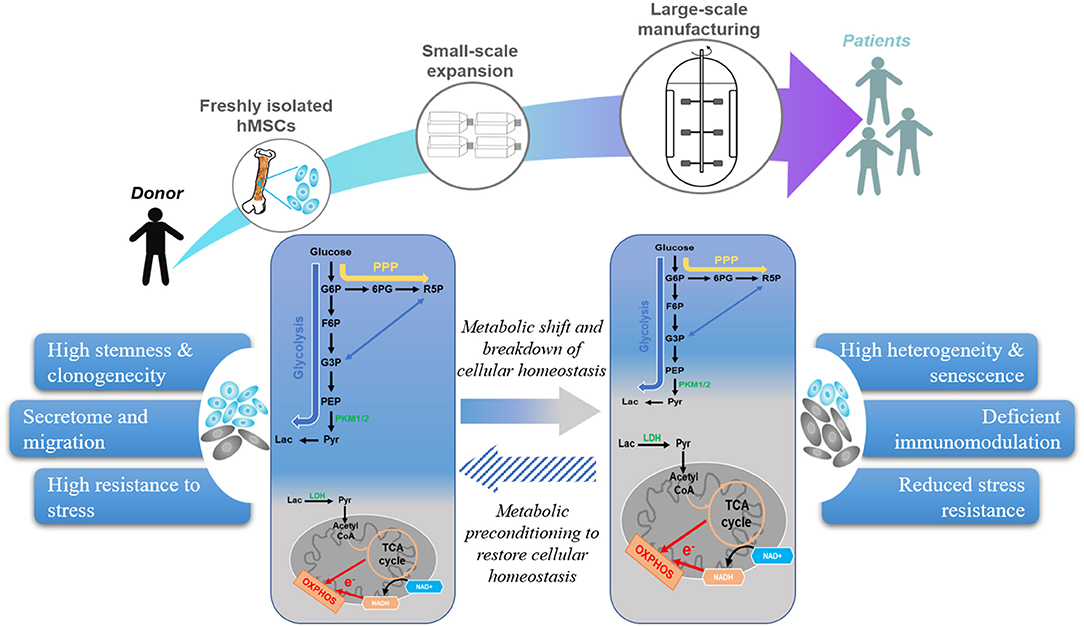

Once viewed as a mere consequence of the cellular state, energy metabolism not only provides energy and substrates for cell growth but is also intimately linked to cell signaling and control of cell fate (16, 20, 21). As depicted in Figure 1, freshly isolated hMSCs mainly compressed a clonogenic subset with high glycolytic activity. Expansion under currently adopted engineering protocols reduces the fraction of clonogenic/glycolytic cells and increases the fraction of mature/OXPHOS-based cells. In fact, this phenotypic and metabolic heterogeneity exists even at the clonal level of hMSCs (22). It has been suggested that changes in the microenvironment and accumulated replicative stress experienced during extended in vitro expansion accelerate hMSC cellular and metabolic heterogeneity by reconfiguring energy metabolism (21, 22). As mentioned above, hMSCs exhibit a quiescent, glycolytic phenotype in a hypoxic in vivo niche such as bone marrow (16, 21). This particular metabolic state may serve to preserve hMSC cellular homeostasis by minimizing ROS production (16, 21, 23), because the high glycolytic flux is also cytoprotective due to increased generation of antioxidant precursors from the pentose phosphate pathway (PPP) (24). Upon removal from this hypoxic, in vivo niche and transfer to the oxygenated, nutrient-rich environment, this quiescent, glycolytic phenotype is no longer of benefit to hMSC (11, 22). During early passages, hMSCs still maintain to an aerobic glycolysis profile, despite its low efficiency for ATP production (25). However, protracted expansion of hMSCs under this nutrient-rich environment induces a metabolic shift from glycolysis toward OXPHOS (22, 26). This metabolic shift is associated with increased coupling between glycolysis and TCA cycle and significantly increased production of ROS and dysfunctional mitochondria (21). A consequence of this culture-induced metabolic shift is a breakdown of cellular homeostasis, characterized by reduced autophagy/mitophagy activity and increased senescence (22, 27–29). A recent proteomic analysis identified several proteins involved in energy metabolism, mitochondrial dysfunction, OXPHOS, and nuclear factor erythroid 2–related factor 2 -mediated oxidative stress response as being among the top canonical pathways that are altered in large-scale production of hMSC in bioreactor system (18). In addition, intrinsic biological factors such as donor disease or chronological age also alter hMSC metabolic profile. For example, hMSCs from obese donors have a higher number of defective mitochondria with reduced dependence on glycolysis and an altered metabolic profile compared to cells obtained from healthy controls (30, 31). hMSCs from aged donors also exhibit greater population heterogeneity with lower mitochondrial-to-cytoplasm area ratio, reduced level of manganese superoxide dismutase (MnSOD) expression, and accumulated ROS compared with cells obtained from young donors (32). Furthermore, hMSCs from donors with age-related atherosclerosis exhibited impaired mitochondrial function that also contributed to metabolic alterations compared to cells obtained from healthy, young donors (33). Culture-based interventions aimed at restoring the mitochondrial function of atherosclerotic-hMSCs by treatment with ROS scavengers effectively restored their immunosuppressive ability to that of healthy donors (33). This study directly linked metabolic alteration due to donor morbidity to reduced hMSC therapeutic potency and demonstrated that metabolic treatment can restore hMSCs to a state capable of delivering the desired therapeutic outcomes. In contrast, the extent of influence of culture-induced metabolic changes on hMSC therapeutic potency is largely unknown because few studies have characterized the metabolic profiles of hMSC used in therapeutic applications. Beyond supplying energy and anabolic production of macromolecules, metabolic circuits engage genetic programs to regulate cellular events and phenotypic and functional properties, reflecting the metabolic substrate, specific pathways, and environmental conditions (23). Although large scale hMSC biomanufacturing often entails significant changes of culture conditions such as media composition and substrates (e.g., sugar vs. fatty acids), supplements (e.g., fetal bovine serum vs. platelet lysate), expansion protocols (e.g., multi-well plates vs. bioreactor), and cryopreservation (e.g., cryogen and freeze-thaw cycles), few studies have elucidated the influence of these changes on hMSC functional properties and clinical outcome (1, 6, 34–38).

Figure 1. Current hMSC manufacturing practices lead to metabolic shift that reduces therapeutic properties. hMSC manufacturing utilizes freshly isolated hMSCs and expand under artificial environment to obtain sufficient cell number for clinical application. However, external stresses during replicative expansion, and cryopreservation shift hMSC metabolism from glycolysis toward OXPHOS, which increases senescent subset and contributes to a breakdown of cellular homeostasis. Metabolic preconditioning targeting specific pathways can restore hMSC cellular homeostasis and enhance their therapeutic potency.

Preclinical studies on the mechanistic connections between metabolism and hMSC phenotype provide specific molecular targets and pathways that can be modulated to maintain, or remodel metabolic profiles of culture expanded hMSCs. For example, hypoxia culture has been widely used in hMSC expansion as it better preserves the clonogenic subset during hMSC expansion by maintaining glycolysis and suppressing TCA cycle and OXPHOS activity (15, 26, 39, 40), most likely through activation of hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF) related genes (41). As a consequence of the glycolytic metabolic profile, hypoxia culture also activates hMSC autophagy while reducing senescence and preserving hMSC functional properties by maintaining cellular homeostasis in vitro (40, 42). However, hMSCs are not only sensitive to the absolute oxygen level but also to the fluctuation in oxygen tension, which significantly complicates implementing hypoxia as an engineering protocol for maintaining stem cell properties in large scale manufacturing (43, 44). More recently, the benefits of hMSC hypoxia culture have been recapitulated at ambient oxygen tensions by treatment of small molecule modulators that target specific metabolic regulatory pathways identified in hypoxia studies. Since HIF is a downstream effector of mTOR, inhibition of Akt/mTOR signaling pathway with rapamycin and LY294002 reduced mitochondrial activity, and glycolysis–TCA coupling, prevented culture-induced senescence (20, 45). These studies highlight the importance for a balance between AKT/mTOR activity and intracellular signaling for maintaining glycolytic metabolism to preserve stem cell functions. Non-hypoxic stabilization of HIF-1α using hypoxia mimetics such as desferoxamine (DFO), ciclopirox olamine, the HIF-prolyl hydroxylase (PHD) inhibitor FG-4497, or cobalt chloride (CoCl2) have also been shown to overcome the challenge of controlling ambient oxygen tension to effectively maintain MSC properties (45–47).

hMSCs have intriguing properties of self-assembly into three-dimensional (3D) aggregates mediated by cell-cell and cell-ECM interaction, which better preserve hMSC phenotypic properties compared to their 2D counterparts (48). The benefits of 3D aggregation culture in preserving hMSC stemness and enhancing secretion of immunomodulatory cytokines can also be attributed to aggregation-induced metabolic reconfiguration, which inhibits mitochondrial activity and increases glycolysis with increased anaplerotic flux (28, 48–50). While the metabolic reprograming in 3D aggregates has been commonly attributed to oxygen diffusion limitation, our recent studies reveal that actin-mediated cellular compaction activates PI3K/Akt pathway and induces metabolic shift toward glycolysis (48, 51), highlighting energy metabolism as a signaling hub in regulating hMSC functions during in vitro culture.

The Role of Metabolism in the hMSC Immune Response and Immunomodulation

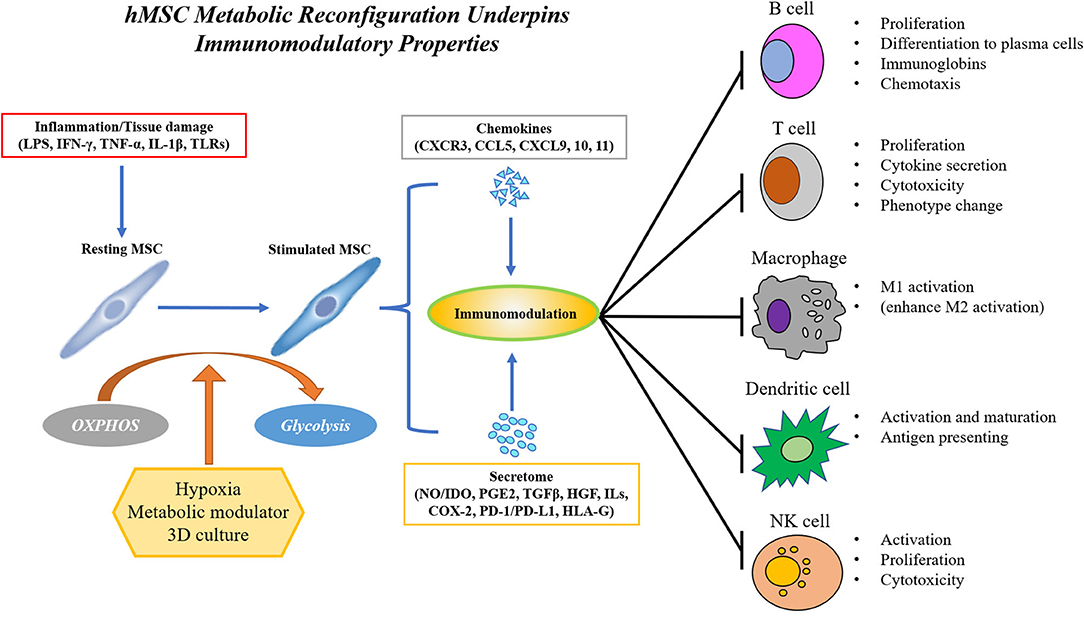

As mentioned earlier in this review, an attractive feature of hMSC as a cell therapy product is their immunomodulatory properties in response to environmental stimuli from surrounding tissues resulting in the secretion of beneficial cytokines and cellular components such as microRNA and extracellular vesicles; as might be expected, these properties are significantly influenced by metabolism. As shown in Figure 2, in the presence of inflammatory cytokines such as interferon-γ (IFN-γ) alone or in combination with tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) or interlukin-1 (IL-1), MSCs secrete chemokines such as CXC-chemokine receptor 3 (CXCR3), CC-chemokine receptor 5 (CCR5) ligands, CXC-chemokine ligand 9 (CXCL9), CXCL10, and CXCL11 (52, 53), which attract immune cells via chemotaxis (52, 54–56). Recruited T cells are inhibited by activated hMSCs through the secretion of indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO), a catabolic enzyme that regulates tryptophan metabolism (54). Besides IDO, hMSC is also a potent source of other soluble immunosuppressive factors, such as nitric oxide (NO, in rodent MSCs), prostaglandin E2 (PGE2), transforming growth factor-β1 (TGF-β1), hepatocyte growth factor (HGF), interleukins and cyclooxygenase 2 (COX-2). MSCs promote the polarization of macrophages from a pro-inflammatory M1 phenotype to an anti-inflammatory M2 phenotype and suppress IL-6 and TNF-α production in macrophages through secretion of PGE2 and IDO (57–61). Similarly, co-culture with MSCs inhibits the maturation and activation of antigen-presenting dendritic cells (DCs) and reduces B cell proliferation by increased production of IL-10, chemokine receptors, and immunoglobulins (62–68). Compared to B cells, MSCs inhibit T cell proliferation regardless of their lineage difference (naïve, CD4+ or CD8+ lineage) (20, 69). Moreover, MSCs from multiple sources exhibit similar effects on inducing apoptosis of T cells (70). IDO, HGF, TGF-β, PGE2, and PD-1/PD-L1 ligation from MSCs all contribute to the immunosuppressive effect (20, 71–75). As the hMSC secretome is central to their immunomodulatory properties, preserving the secretory properties of hMSC during long-term expansion has become an important engineering challenge in hMSC translation (4).

Figure 2. hMSC immunomodulation requires polarization by inflammatory environment and is achieved by the secretion of immunomodulatory factors such as chemokines and cytokines, extracellular vesicles and exosome, and direct cell-cell contact. hMSC's immunomodulatory property requires a metabolic reconfiguration toward aerobic glycolysis to sustain the production of secretome. hMSC's immunomodulatory capacity can be enhanced by modulation of hMSC metabolism via hypoxia, small molecule metabolic mediators, or 3D aggregation.

The profile of MSC secretome is tightly regulated by intrinsic (e.g., donor morbidity and aging) or external (e.g., culture conditions) factors through metabolic regulation. Adipose-derived stem cells showed a higher secretion of immunomodulatory cytokines, such as IL-6 and TGF compared to bone marrow (BM)-MSCs due to higher metabolic activity (76). Conversely, compared to cells obtained from lean patients, ASCs from obese patients exhibiting reduced glycolytic activity and upregulated expression of inflammatory genes and increased secretion of inflammatory cytokines such as IL-6 and IL-8 (30, 77, 78), making them less effective in suppressing lymphocyte proliferation and activating the M2 macrophage phenotype (79). The expression of inflammation-response genes has been reported to decline in hMSC from aged donors as they have altered metabolic profile, although conflicting results were also reported (80–82). Interestingly, recent clinical study has shown that hMSCs isolated from patient with atherosclerosis have impaired mitochondrial functional properties, contributing to the reduced suppression of T cell proliferation (33). To identify the specific role of metabolism in sustaining hMSC secretion of immunomodulatory cytokines, we observed a pronounced shift in hMSC energy metabolism toward glycolysis upon activation by IFN-γ treatment (20) and showed that inhibition of these metabolic changes prevented the production of the key immunosuppressive cytokines such as IDO and PGE2. We also demonstrated that mitochondrial ROS and Akt/mTOR signaling play a critical role in initiating this metabolic remodeling in response to inflammatory stimuli (20, 55, 83). It is not surprising that culture conditions favoring glycolysis also potentiate MSC immunomodulatory properties. As mentioned above, hypoxia culture upregulates MSC secretion of IDO, PGE2, PD-L1, ILs, etc., and enhances inhibition of CD4+/CD8+ T lymphocyte proliferation while increasing the regulatory T cells (T-reg) populations (84–86). In addition to the MSC secretome, direct cell-cell contact could directly interact with immune cells (87–92), but the influence of specific MSC metabolic profiles on these interactions remain to be investigated.

An important subset of the MSC secretome is extracellular vehicles (EVs) and exosomes, which are small membrane vesicles (ranging from 50 to 1,000 nm) derived from multi-vesicular bodies or from the plasma membrane and are enriched with proteins, lipids, and nucleic acids for intercellular communication including immune regulation (93, 94). MSC-derived EVs and exosomes have been tested in several disease models such as acute kidney injury, experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis, type-1 diabetes mellitus and myocardial ischemic injury through microRNA (miRNA) regulation (95–99). Mechanistically, MSC-derived EVs and exosomes are enriched with miRNA such as miR-15a, miR-15b, miR-16 that inhibit CXC ligands and suppress chemotaxis of macrophage (95, 100). Recent studies have shown that metabolism regulates EV biogenesis and cargo composition through regulation of endosomal secretion pathways. In tumor cells, pyruvate kinase type M2 (PKM2), the rate limiting enzyme in glycolysis, acts as a protein kinase to promote exosome release via phosphorylating snaptosome-associated protein 23 (SNAP-23), which mediates the fusion of intracellular vesicles with membrane compartments (101). HIF-1α overexpression in hMSCs significantly enhanced exosome secretion and also upregulated Notch ligand Jagged-1, which induce dendritic cell maturation and regulatory T cell proliferation (102, 103). Hypoxia is known to mediate the expression of Rab22 and Rab20 and ceramide production, which are associated with EV formation and secretion (104). MSCs also manage intracellular oxidative stress by targeting depolarized mitochondria to the plasma membrane and unload partially depolarized mitochondria as EVs to enhance cell survival (105). Conversely, secreted exosomes regulate metabolism of recipient cells. For example, MSC exosome carry a cargo rich in active glycolytic enzymes and promote ischemic myocardium repair by enhancing glycolytic flux to compensate for the reduced OXPHOS in defective mitochondria (106). Future studies are needed to establish the mechanistic connection between hMSC metabolism and biogenesis and cargo composition of hMSC-derived EV.

Targeting hMSC Metabolism to Enhance Immunomodulatory Properties in Preclinical Studies

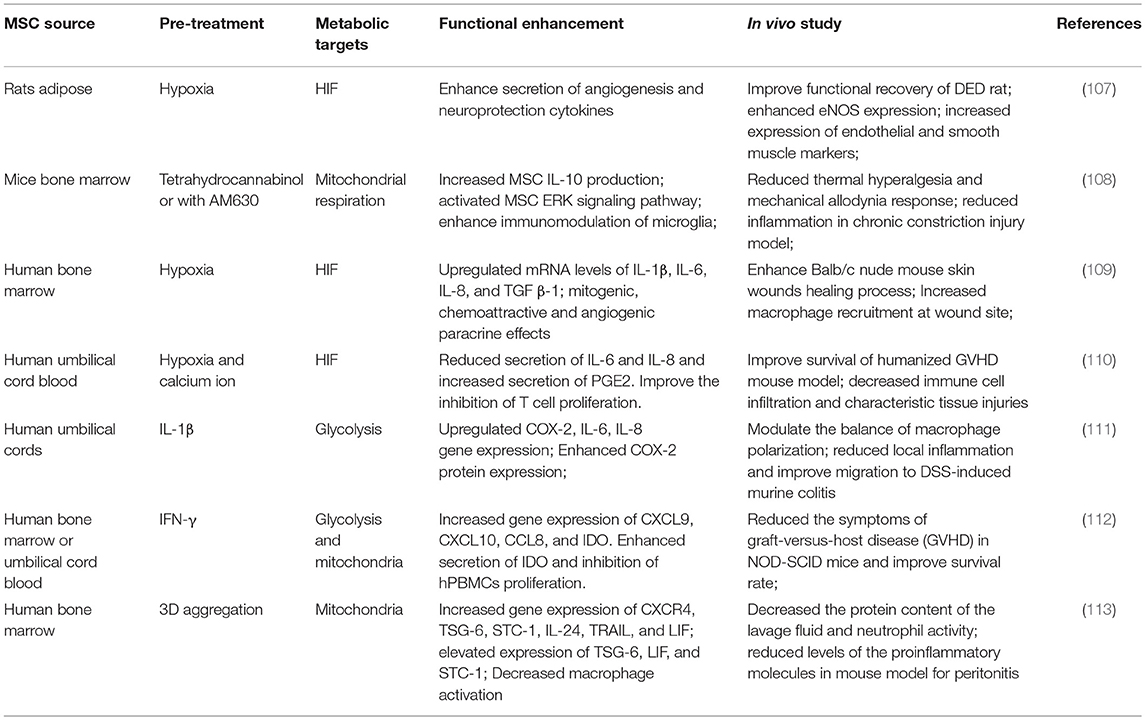

Investigating the mechanistic connections between metabolism and immunomodulation has identified specific molecular targets that can be modulated to overcome metabolic deficiency due to donor age and morbidity, and to enhance the therapeutic potency of culture-expanded hMSCs. Table 1 summarized preclinical studies of enhanced MSC immunomodulation via metabolic regulation. As discussed above, hypoxia treatment is commonly used to enhance hMSC immunoregulatory properties by increasing hMSC anti-inflammatory properties while attenuating the secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines, both in vitro and in vivo (84–86). In a preclinical study, hypoxic pre-treatment of hMSC enhanced the secretion of IL-10 and Fas ligand, thereby reducing recruitment of inflammatory cells, resulting in a more organized granulation tissue at the wound site in an excisional skin-healing mouse model (85). Transplantation of hMSC expanded under hypoxia in a humanized mouse graft vs. host disease (GVHD) model improved animal survival and weight loss, and reduced histopathologic injuries in GVHD target organs, presumably due to enhanced PGE-2 secretion and reduced IL-6/IL-8 secretion (110). To overcome the complexity and inconsistency associated with in vitro hypoxia culture, overexpression of HIF1-α and hypoxia mimetics targeting HIF pathway are being actively pursued to enhance hMSC immunomodulatory properties (114, 115). Oxidative preconditioning of MSCs by ROS leads to redox-dependent HIF-1α stabilization and reduced apoptosis in inflammatory environment (116, 117). Pretreatment with N-acetylcysteine (NAC), which stabilizes HIF-1, improved MSC anti-inflammation and cell retention in bleomycin-induced lung injury model by improving antioxidant capacity (118).

Table 1. Metabolic enhancement of mesenchymal stem cell-mediated immunomodulation in preclinical studies.

Pre-activation of MSCs with immunomodulatory cytokines has been widely reported to enhance MSC immunomodulatory effect in various preclinical models. Interestingly, many such cytokines are also metabolic regulators and the extent of their effects is influenced by oxygen levels and MSC's metabolic plasticity (119, 120). Pretreatment of hMSC with IFN-γ activates hMSC's anti-inflammatory properties by enhancing the secretion of anti-inflammatory cytokines and inhibits the proliferation of NK cells and CD4+/CD8+ T cells (20, 111, 121, 122). Infusion of IFN-γ pretreated MSCs in an immunodeficient mouse model significantly reduced the symptoms of GVHD and improved survival (112). As mentioned above, IFN-γ treatment reconfigures hMSC metabolism toward a glycolytic phenotype, generating a metabolic profile that enhances cell survival and sustains the secretion of immunomodulatory factors (20). Fan et al. reported that MSCs preconditioned by IL-1β exposure significantly attenuated the development of dextran sulfate sodium (DSS)-induced colitis in mice by enhancing MSC migration to the inflammatory site via upregulating CXCR4 expression (111). The IL-1 cytokine family members are important regulators of metabolism and upregulate glycolysis in various cell types (119, 123). TGF- β, a pleiotropic cytokine involved in immune regulation, is also a potent regulator of hMSC immunomodulatory properties and can display either anti-inflammatory or proinflammatory effects depending on the cell niche. TGF-β activates MSC to promote immune response and altered hASC secretory profile (124–126). Interestingly, TGF-β signaling in tumor growth is compartment-specific and induces a “Warburg-like” metabolism in cancer-associated fibroblasts that fuels tumor growth; a similar metabolic shift toward glycolysis is also observed in human chondrocytes and plays important role in maintaining cartilage homeostasis (127, 128). The effects of TGF-β on hMSC metabolic properties during immune activation remains to be elucidated.

As mentioned above, 3D aggregation reconfigures hMSC metabolic state toward glycolysis and this approach has emerged as a novel engineering strategy to potentiate MSC secretory and immunomodulatory functions. Bartosh et al. reported in vivo aggregation of MSCs into 3D spheroid enhanced macrophage activation in mice with regulated expression of inflammation-modulating factors TSG-6, STC-1, and COX-2 (129). Zimmerman et al. demonstrated the enhanced suppression of T cells by MSC spheroids together with IFN-γ via the secretion of IDO from 3D MSC aggregates (130). Increased secretion of PGE2 and COX2 from 3D MSC aggregates converted LPS-activated macrophages into M2 phenotype with reduced production of TNF-α, IL-6, IL-23, and CXCL2 (113, 131). Intraluminal injection of MSC aggregates in mice with DSS-induced colitis reduced local inflammatory cytokines including TNF-α, IFN-γ, IL-6, and the system inflammation marker serum amyloid A (132), whereas the local expression of PGE-2 and COX-2 in mice distal colons were increased, resulting in less body weight loss and lower disease activity score (132). Inhibition of this metabolic reconfiguration in hMSC 3D aggregates reduces secretion of IDO, PGE2, COX2, IL-6, TGF-β and other anti-inflammatory cytokines (113, 129, 131, 133). These studies demonstrate the potential of 3D aggregation to potentiate hMSC immunomodulatory properties.

Conclusions

This review shows that energy metabolism has emerged as a central hub connecting hMSC sourcing and biomanufacturing practices to core signaling pathways that regulate hMSC phenotypic properties and clinical outcome. Modulation of hMSC metabolism by specific engineering practices or metabolic modulators is an effective strategy for enhancing hMSC functional properties and improving therapeutic potency. hMSC metabolic characteristics or fitness can also be used as defining criteria to determine cellular quality in hMSC sourcing and large-scale manufacturing. As summarized in Box 1, many open questions remain in the implementation of metabolic strategies to enhance hMSC therapeutic potency in large scale manufacturing. Future studies that elucidate the signaling roles of other intermediate metabolites are needed to identify novel targets to improve hMSC clinical outcomes.

Box 1. Current knowledge and future directions of metabolic perturbation in hMSC biomanufacturing and immunotherapy.

Energy metabolism in hMSC biomanufacturing and immunotherapy

Current knowledge

• hMSC's are metabolically “plastic” and reconfigure metabolism to match divergent demands of cellular events;

• hMSC's metabolic “fitness” or the ability to adapt metabolically influences their functional properties;

• Donor morbidity and in vitro bioprocessing such as extended expansion and cryopreservation reduce hMSC metabolic fitness by preconditioning is an effective strategy to enhance hMSC therapeutic potency.

Open question and future direction

• What is the mechanistic link between hMSC metabolic profile and therapeutic outcome in a given disease?

• Can hMSC metabolism profile be standardized as a potency indicator as part of Critical Quality Attributes (CQA)?

• How the media composition and culture supplement such as human platelet lysate and lipid contents used in hMSC expansion influence metabolic fitness and functional properties?

• How to maintain a desired metabolic profile during large-scale expansion, harvesting, and cryopreservation (distribution and administration) in hMSC biomanufacturing?

• How does a given metabolic profile influence specific aspect of hMSC functional properties such as angiogenesis, or immunomodulation?

Author Contributions

XY and TM organized the structure, collected references, and wrote the manuscript. TL organized and revised the manuscript. All authors contributed to manuscript revision, read, and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This work is supported by the National Science Foundation (CBET 1743426) and National Institutes of Health (NIH) (R01 NS102395). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NSF and NIH.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

1. Yin JQ, Zhu J, Ankrum JA. Manufacturing of primed mesenchymal stromal cells for therapy. Nat Biomed Eng. (2019) 3:90–104. doi: 10.1038/s41551-018-0325-8

2. Castro-Manrreza ME, Montesinos JJ. Immunoregulation by mesenchymal stem cells: biological aspects and clinical applications. J Immunol Res. (2015) 2015:394917. doi: 10.1155/2015/394917

3. Galipeau J, Krampera M, Barrett J, Dazzi F, Deans RJ, DeBruijn J, et al. International Society for Cellular Therapy perspective on immune functional assays for mesenchymal stromal cells as potency release criterion for advanced phase clinical trials. Cytotherapy. (2016) 18:151–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jcyt.2015.11.008

4. Galipeau J, Sensebe L. Mesenchymal stromal cells: clinical challenges and therapeutic opportunities. Cell Stem Cell. (2018) 22:824–33. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2018.05.004

5. von Bahr L, Sundberg B, Lonnies L, Sander B, Karbach H, Hagglund H, et al. Long-term complications, immunologic effects, and role of passage for outcome in mesenchymal stromal cell therapy. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. (2012) 18:557–64. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2011.07.023

6. Moll G, Alm JJ, Davies LC, von Bahr L, Heldring N, Stenbeck-Funke L, et al. Do cryopreserved mesenchymal stromal cells display impaired immunomodulatory and therapeutic properties? Stem Cells. (2014) 32:2430–42. doi: 10.1002/stem.1729

7. Castro B, Martinez-Redondo D, Gartzia I, Alonso-Varona A, Garrido P, Palomares T. Cryopreserved H2 O2 -preconditioned human adipose-derived stem cells exhibit fast post-thaw recovery and enhanced bioactivity against oxidative stress. J Tissue Eng Regen Med. (2019) 13:328–41. doi: 10.1002/term.2797

8. Waterman RS, Tomchuck SL, Henkle SL, Betancourt AM. A new mesenchymal stem cell (MSC) paradigm: polarization into a pro-inflammatory MSC1 or an Immunosuppressive MSC2 phenotype. PLoS ONE. (2010) 5:e10088. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010088

9. Olsen TR, Ng KS, Lock LT, Ahsan T, Rowley JA. Peak MSC-are we there yet? Front Med. (2018) 5:178. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2018.00178

10. Robb KP, Fitzgerald JC, Barry F, Viswanathan S. Mesenchymal stromal cell therapy: progress in manufacturing and assessments of potency. Cytotherapy. (2018) 21:289–306. doi: 10.1016/j.jcyt.2018.10.014

11. Bara JJ, Richards RG, Alini M, Stoddart MJ. Concise review: bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells change phenotype following in vitro culture: implications for basic research and the clinic. Stem Cells. (2014) 32:1713–23. doi: 10.1002/stem.1649

12. Sbrana FV, Cortini M, Avnet S, Perut F, Columbaro M, De Milito A, et al. The role of autophagy in the maintenance of stemness and differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells. Stem Cell Rev. (2016) 12:621–33. doi: 10.1007/s12015-016-9690-4

13. Katajisto P, Dohla J, Chaffer CL, Pentinmikko N, Marjanovic N, Iqbal S, et al. Stem cells. Asymmetric apportioning of aged mitochondria between daughter cells is required for stemness. Science. (2015) 348:340–3. doi: 10.1126/science.1260384

14. Sherr CJ, DePinho RA. Cellular senescence: mitotic clock or culture shock? Cell. (2000) 102:407–10. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)00046-5

15. Pattappa G, Heywood HK, de Bruijn JD, Lee DA. The metabolism of human mesenchymal stem cells during proliferation and differentiation. J Cell Physiol. (2011) 226:2562–70. doi: 10.1002/jcp.22605

16. Shyh-Chang N, Daley GQ, Cantley LC. Stem cell metabolism in tissue development and aging. Development. (2013) 140:2535–47. doi: 10.1242/dev.091777

17. Ho TT, Warr MR, Adelman ER, Lansinger OM, Flach J, Verovskaya EV, et al. Autophagy maintains the metabolism and function of young and old stem cells. Nature. (2017) 543:205–10. doi: 10.1038/nature21388

18. Cunha B, Aguiar T, Carvalho SB, Silva MM, Gomes RA M., Carrondo JT, et al. Bioprocess integration for human mesenchymal stem cells: from up to downstream processing scale-up to cell proteome characterization. J Biotechnol. (2017) 248:87–98. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2017.01.014

19. Green DR, Galluzzi L, Kroemer G. Cell biology. Metabolic control of cell death. Science. (2014) 345:1250256. doi: 10.1126/science.1250256

20. Liu Y, Yuan X, Munoz N, Logan TM, Ma T. Commitment to aerobic glycolysis sustains immunosuppression of human mesenchymal stem cells. Stem Cells Transl Med. (2019) 8:93–106. doi: 10.1002/sctm.18-0070

21. Liu Y, Ma T. Metabolic regulation of mesenchymal stem cell in expansion and therapeutic application. Biotechnol Prog. (2015) 31:468–81. doi: 10.1002/btpr.2034

22. Liu Y, Munoz N, Bunnell BA, Logan TM, Ma T. Density-dependent metabolic heterogeneity in human mesenchymal stem cells. Stem Cells. (2015) 33:3368–81. doi: 10.1002/stem.2097

23. Folmes CD, Dzeja PP, Nelson TJ, Terzic A. Metabolic plasticity in stem cell homeostasis and differentiation. Cell Stem Cell. (2012) 11:596–606. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2012.10.002

24. Galluzzi L, Kepp O, Vander Heiden MG, Kroemer G. Metabolic targets for cancer therapy. Nat Rev Drug Discov. (2013) 12:829–46. doi: 10.1038/nrd4145

25. Vander Heiden MG, Cantley LC, Thompson CB. Understanding the Warburg effect: the metabolic requirements of cell proliferation. Science. (2009) 324:1029–33. doi: 10.1126/science.1160809

26. Estrada JC, Albo C, Benguría A, Dopazo A, López-Romero P, Carrera-Quintanar L, et al. Culture of human mesenchymal stem cells at low oxygen tension improves growth and genetic stability by activating glycolysis. Cell Death Different. (2011) 19:743. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2011.172

27. Gao L, Cen S, Wang P, Xie Z, Liu Z, Deng W, et al. Autophagy improves the immunosuppression of CD4+ T cells by mesenchymal stem cells through transforming growth factor-beta1. Stem Cells Transl Med. (2016) 5:1496–505. doi: 10.5966/sctm.2015-0420

28. Liu Y, Munoz N, Tsai AC, Logan TM, Ma T. Metabolic reconfiguration supports reacquisition of primitive phenotype in human mesenchymal stem cell aggregates. Stem Cells. (2017) 35:398–410. doi: 10.1002/stem.2510

29. Oh J, Lee YD, Wagers AJ. Stem cell aging: mechanisms, regulators and therapeutic opportunities. Nat Med. (2014) 20:870–80. doi: 10.1038/nm.3651

30. Perez LM, Bernal A, de Lucas B, San Martin N, Mastrangelo A, Garcia A, et al. Altered metabolic and stemness capacity of adipose tissue-derived stem cells from obese mouse and human. PLoS ONE. (2015) 10:e0123397. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0123397

31. Meng Y, Eirin A, Zhu XY, Tang H, Chanana P, Lerman A, et al. Obesity-induced mitochondrial dysfunction in porcine adipose tissue-derived mesenchymal stem cells. J Cell Physiol. (2018) 233:5926–36. doi: 10.1002/jcp.26402

32. Pietila M, Palomaki S, Lehtonen S, Ritamo I, Valmu L, Nystedt J, et al. Mitochondrial function and energy metabolism in umbilical cord blood- and bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells. Stem Cells Dev. (2012) 21:575–88. doi: 10.1089/scd.2011.0023

33. Kizilay Mancini O, Lora M, Cuillerier A, Shum-Tim D, Hamdy R, Burelle Y, et al. Mitochondrial oxidative stress reduces the immunopotency of mesenchymal stromal cells in adults with coronary artery disease. Circ Res. (2018) 122:255–66. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.117.311400

34. Fillmore N, Huqi A, Jaswal JS, Mori J, Paulin R, Haromy A, et al. Effect of fatty acids on human bone marrow mesenchymal stem cell energy metabolism and survival. PLoS ONE. (2015) 10:e0120257. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0120257

35. Heathman TR, Glyn VA, Picken A, Rafiq QA, Coopman K, Nienow AW, et al. Expansion, harvest and cryopreservation of human mesenchymal stem cells in a serum-free microcarrier process. Biotechnol Bioeng. (2015) 112:1696–707. doi: 10.1002/bit.25582

36. Becherucci V, Piccini L, Casamassima S, Bisin S, Gori V, Gentile F, et al. Human platelet lysate in mesenchymal stromal cell expansion according to a GMP grade protocol: a cell factory experience. Stem Cell Res Ther. (2018) 9:124. doi: 10.1186/s13287-018-0863-8

37. Moya A, Paquet J, Deschepper M, Larochette N, Oudina K, Denoeud C, et al. Human mesenchymal stem cell failure to adapt to glucose shortage and rapidly use intracellular energy reserves through glycolysis explains poor cell survival after implantation. Stem Cells. (2018) 36:363–76. doi: 10.1002/stem.2763

38. Savelli S, Trombi L, D'Alessandro D, Moscato S, Pacini S, Giannotti S, et al. Pooled human serum: a new culture supplement for bioreactor-based cell therapies. Preliminary results. Cytotherapy. (2018) 20:556–63. doi: 10.1016/j.jcyt.2017.12.013

39. Dos Santos F, Andrade PZ, Boura JS, Abecasis MM, da Silva CL, Cabral JM. Ex vivo expansion of human mesenchymal stem cells: a more effective cell proliferation kinetics and metabolism under hypoxia. J Cell Physiol. (2010) 223:27–35. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21987

40. Munoz N, Kim J, Liu Y, Logan TM, Ma T. Gas chromatography-mass spectrometry analysis of human mesenchymal stem cell metabolism during proliferation and osteogenic differentiation under different oxygen tensions. J Biotechnol. (2014) 169:95–102. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2013.11.010

41. Ma T, Grayson WL, Frohlich M, Vunjak-Novakovic G. Hypoxia and stem cell-based engineering of mesenchymal tissues. Biotechnol Prog. (2009) 25:32–42. doi: 10.1002/btpr.128

42. Liu J, Hao H, Huang H, Tong C, Ti D, Dong L, et al. Hypoxia regulates the therapeutic potential of mesenchymal stem cells through enhanced autophagy. Int J Low Extrem Wounds. (2015) 14:63–72. doi: 10.1177/1534734615573660

43. Wenger RH, Kurtcuoglu V, Scholz CC, Marti HH, Hoogewijs D. Frequently asked questions in hypoxia research. Hypoxia. (2015) 3:35–43. doi: 10.2147/HP.S92198

44. Grayson WL, Zhao F, Bunnell B, Ma T. Hypoxia enhances proliferation and tissue formation of human mesenchymal stem cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. (2007) 358:948–53. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.05.054

45. Gharibi B, Farzadi S, Ghuman M, Hughes FJ. Inhibition of Akt/mTOR attenuates age-related changes in mesenchymal stem cells. Stem Cells. (2014) 32:2256–66. doi: 10.1002/stem.1709

46. Liu XB, Wang JA, Ogle ME, Wei L. Prolyl hydroxylase inhibitor dimethyloxalylglycine enhances mesenchymal stem cell survival. J Cell Biochem. (2009) 106:903–11. doi: 10.1002/jcb.22064

47. Najafi R, Sharifi AM. Deferoxamine preconditioning potentiates mesenchymal stem cell homing in vitro and in streptozotocin-diabetic rats. Expert Opin Biol Ther. (2013) 13:959–72. doi: 10.1517/14712598.2013.782390

48. Tsai AC, Liu Y, Yuan X, Ma T. Compaction, fusion, and functional activation of three-dimensional human mesenchymal stem cell aggregate. Tissue Eng Part A. (2015) 21:1705–19. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2014.0314

49. Sart S, Tsai AC, Li Y, Ma T. Three-dimensional aggregates of mesenchymal stem cells: cellular mechanisms, biological properties, and applications. Tissue Eng Part B Rev. (2014) 20:365–80. doi: 10.1089/ten.teb.2013.0537

50. Yuan X, Tsai AC, Farrance I, Rowley J, Ma T. Aggregation of culture expanded human mesenchymal stem cells in microcarrier-based bioreactor. Biochem Eng J. (2018) 131:39–46. doi: 10.1016/j.bej.2017.12.011

51. Bijonowski BM, Daraiseh SI, Yuan X, Ma T. Size-dependent cortical compaction induces metabolic adaptation in mesenchymal stem cell aggregates. Tissue Eng Part A. (2018) 25:575–87. doi: 10.1089/ten.TEA.2018.0155

52. Ren G, Zhang L, Zhao X, Xu G, Zhang Y, Roberts AI, et al. Mesenchymal stem cell-mediated immunosuppression occurs via concerted action of chemokines and nitric oxide. Cell Stem Cell. (2008) 2:141–50. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2007.11.014

53. Gao F, Chiu SM, Motan DA, Zhang Z, Chen L, Ji HL, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells and immunomodulation: current status and future prospects. Cell Death Dis. (2016) 7:e2062. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2015.327

54. Li W, Ren G, Huang Y, Su J, Han Y, Li J, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells: a double-edged sword in regulating immune responses. Cell Death Differ. (2012) 19:1505–13. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2012.26

55. Turner MD, Nedjai B, Hurst T, Pennington DJ. Cytokines and chemokines: at the crossroads of cell signalling and inflammatory disease. Biochim Biophys Acta. (2014) 1843:2563–82. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2014.05.014

56. Hemeda H, Jakob M, Ludwig AK, Giebel B, Lang S, Brandau S. Interferon-gamma and tumor necrosis factor-alpha differentially affect cytokine expression and migration properties of mesenchymal stem cells. Stem Cells Dev. (2010) 19:693–706. doi: 10.1089/scd.2009.0365

57. Cho DI, Kim MR, Jeong HY, Jeong HC, Jeong MH, Yoon SH, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells reciprocally regulate the M1/M2 balance in mouse bone marrow-derived macrophages. Exp Mol Med. (2014) 46:e70. doi: 10.1038/emm.2013.135

58. Melief SM, Geutskens SB, Fibbe WE, Roelofs H. Multipotent stromal cells skew monocytes towards an anti-inflammatory function: the link with key immunoregulatory molecules. Haematologica. (2013) 98:e121–2. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2013.093864

59. Yen BL, Chang CJ, Liu KJ, Chen YC, Hu HI, Bai CH, et al. Brief report–human embryonic stem cell-derived mesenchymal progenitors possess strong immunosuppressive effects toward natural killer cells as well as T lymphocytes. Stem Cells. (2009) 27:451–6. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2008-0390

60. Sotiropoulou PA, Perez SA, Gritzapis AD, Baxevanis CN, Papamichail M. Interactions between human mesenchymal stem cells and natural killer cells. Stem Cells. (2006) 24:74–85. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2004-0359

61. Thomas H, Jager M, Mauel K, Brandau S, Lask S, Flohe SB. Interaction with mesenchymal stem cells provokes natural killer cells for enhanced IL-12/IL-18-induced interferon-gamma secretion. Mediators Inflamm. (2014) 2014:143463. doi: 10.1155/2014/143463

62. Spaggiari GM, Moretta L. Interactions between mesenchymal stem cells and dendritic cells. Adv Biochem Eng Biotechnol. (2013) 130:199–208. doi: 10.1007/10_2012_154

63. Spaggiari GM, Capobianco A, Becchetti S, Mingari MC, Moretta L. Mesenchymal stem cell-natural killer cell interactions: evidence that activated NK cells are capable of killing MSCs, whereas MSCs can inhibit IL-2-induced NK-cell proliferation. Blood. (2006) 107:1484–90. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-07-2775

64. Nauta AJ, Kruisselbrink AB, Lurvink E, Willemze R, Fibbe WE. Mesenchymal stem cells inhibit generation and function of both CD34+-derived and monocyte-derived dendritic cells. J Immunol. (2006) 177:2080–7. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.4.2080

65. Wang Y, Chen X, Cao W, Shi Y. Plasticity of mesenchymal stem cells in immunomodulation: pathological and therapeutic implications. Nat Immunol. (2014) 15:1009–16. doi: 10.1038/ni.3002

66. Franquesa M, Hoogduijn MJ, Bestard O, Grinyo JM. Immunomodulatory effect of mesenchymal stem cells on B cells. Front Immunol. (2012) 3:212. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2012.00212

67. Tabera S, Perez-Simon JA, Diez-Campelo M, Sanchez-Abarca LI, Blanco B, Lopez A, et al. The effect of mesenchymal stem cells on the viability, proliferation and differentiation of B-lymphocytes. Haematologica. (2008) 93:1301–9. doi: 10.3324/haematol.12857

68. Corcione A, Benvenuto F, Ferretti E, Giunti D, Cappiello V, Cazzanti F, et al. Human mesenchymal stem cells modulate B-cell functions. Blood. (2006) 107:367–72. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-07-2657

69. Wang LT, Ting CH, Yen ML, Liu KJ, Sytwu HK, Wu KK, et al. Human mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) for treatment towards immune- and inflammation-mediated diseases: review of current clinical trials. J Biomed Sci. (2016) 23:76. doi: 10.1186/s12929-016-0289-5

70. Carrade Holt DD, Wood JA, Granick JL, Walker NJ, Clark KC, Borjesson DL. Equine mesenchymal stem cells inhibit T cell proliferation through different mechanisms depending on tissue source. Stem Cells Dev. (2014) 23:1258–65. doi: 10.1089/scd.2013.0537

71. Hsu WT, Lin CH, Chiang BL, Jui HY, Wu KK, Lee CM. Prostaglandin E2 potentiates mesenchymal stem cell-induced IL-10+IFN-gamma+CD4+ regulatory T cells to control transplant arteriosclerosis. J Immunol. (2013) 190:2372–80. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1202996

72. Luz-Crawford P, Noel D, Fernandez X, Khoury M, Figueroa F, Carrion F, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells repress Th17 molecular program through the PD-1 pathway. PLoS ONE. (2012) 7:e45272. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0045272

73. Wang WB, Yen ML, Liu KJ, Hsu PJ, Lin MH, Chen PM, et al. Interleukin-25 mediates transcriptional control of PD-L1 via STAT3 in multipotent Human Mesenchymal Stromal Cells (hMSCs) to suppress Th17 responses. Stem Cell Rep. (2015) 5:392–404. doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2015.07.013

74. Augello Tasso R, Negrini SM, Amateis A, Indiveri F, Cancedda R, et al. Bone marrow mesenchymal progenitor cells inhibit lymphocyte proliferation by activation of the programmed death 1 pathway. Eur J Immunol. (2005) 35:1482–90. doi: 10.1002/eji.200425405

75. English K, Barry FP, Field-Corbett CP, Mahon BP. IFN-gamma and TNF-alpha differentially regulate immunomodulation by murine mesenchymal stem cells. Immunol Lett. (2007) 110:91–100. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2007.04.001

76. Melief SM, Zwaginga JJ, Fibbe WE, Roelofs H. Adipose tissue-derived multipotent stromal cells have a higher immunomodulatory capacity than their bone marrow-derived counterparts. Stem Cells Transl Med. (2013) 2:455–63. doi: 10.5966/sctm.2012-0184

77. Silva KR, Liechocki S, Carneiro JR, Claudio-da-Silva C, Maya-Monteiro CM, Borojevic R, et al. Stromal-vascular fraction content and adipose stem cell behavior are altered in morbid obese and post bariatric surgery ex-obese women. Stem Cell Res Ther. (2015) 6:72. doi: 10.1186/s13287-015-0029-x

78. Perez LM, de Lucas B, Lunyak VV, Galvez BG. Adipose stem cells from obese patients show specific differences in the metabolic regulators vitamin D and Gas5. Mol Genet Metab Rep. (2017) 12:51–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgmr.2017.05.008

79. Serena C, Keiran N, Ceperuelo-Mallafre V, Ejarque M, Fradera R, Roche K, et al. Obesity and type 2 diabetes alters the immune properties of human adipose derived stem cells. Stem Cells. (2016) 34:2559–73. doi: 10.1002/stem.2429

80. Baker N, Boyette LB, Tuan RS. Characterization of bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells in aging. Bone. (2015) 70:37–47. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2014.10.014

81. Killer MC, Nold P, Henkenius K, Fritz L, Riedlinger T, Barckhausen C, et al. Immunosuppressive capacity of mesenchymal stem cells correlates with metabolic activity and can be enhanced by valproic acid. Stem Cell Res Ther. (2017) 8:100. doi: 10.1186/s13287-017-0553-y

82. Siegel G, Kluba T, Hermanutz-Klein U, Bieback K, Northoff H, Schafer R. Phenotype, donor age and gender affect function of human bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stromal cells. BMC Med. (2013) 11:146. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-11-146

83. Cham CM, Gajewski TF. Glucose availability regulates IFN-gamma production and p70S6 kinase activation in CD8+ effector T cells. J Immunol. (2005) 174:4670–7. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.8.4670

84. Kadle RL, Abdou SA, Villarreal-Ponce AP, Soares MA, Sultan DL, David JA, et al. Microenvironmental cues enhance mesenchymal stem cell-mediated immunomodulation and regulatory T-cell expansion. PLoS ONE. (2018) 13:e0193178. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0193178

85. Jiang CM, Liu J, Zhao JY, Xiao L, An S, Gou YC, et al. Effects of hypoxia on the immunomodulatory properties of human gingiva-derived mesenchymal stem cells. J Dent Res. (2015) 94:69–77. doi: 10.1177/0022034514557671

86. Bobyleva PI, Andreeva ER, Gornostaeva AN, Buravkova LB. Tissue-related hypoxia attenuates proinflammatory effects of allogeneic PBMCs on adipose-derived stromal cells in vitro. Stem Cells Int. (2016) 2016:4726267. doi: 10.1155/2016/4726267

87. Di Nicola M, Carlo-Stella C, Magni M, Milanesi M, Longoni PD, Matteucci P, et al. Human bone marrow stromal cells suppress T-lymphocyte proliferation induced by cellular or nonspecific mitogenic stimuli. Blood. (2002) 99:3838–43. doi: 10.1182/blood.V99.10.3838

88. Sheng H, Wang Y, Jin Y, Zhang Q, Zhang Y, Wang L, et al. A critical role of IFNgamma in priming MSC-mediated suppression of T cell proliferation through up-regulation of B7-H1. Cell Res. (2008) 18:846–57. doi: 10.1038/cr.2008.80

89. Majumdar MK, Keane-Moore M, Buyaner D, Hardy WB, Moorman MA, McIntosh KR, et al. Characterization and functionality of cell surface molecules on human mesenchymal stem cells. J Biomed Sci. (2003) 10:228–41. doi: 10.1007/BF02256058

90. Han KH, Ro H, Hong JH, Lee EM, Cho B, Yeom HJ, et al. Immunosuppressive mechanisms of embryonic stem cells and mesenchymal stem cells in alloimmune response. Transpl Immunol. (2011) 25:7–15. doi: 10.1016/j.trim.2011.05.004

91. Raicevic G, Najar M, Najimi M, El Taghdouini A, van Grunsven LA, Sokal E, et al. Influence of inflammation on the immunological profile of adult-derived human liver mesenchymal stromal cells and stellate cells. Cytotherapy. (2015) 17:174–85. doi: 10.1016/j.jcyt.2014.10.001

92. Najar M, Raicevic G, Fayyad-Kazan H, De Bruyn C, Bron D, Toungouz M, et al. Immune-related antigens, surface molecules and regulatory factors in human-derived mesenchymal stromal cells: the expression and impact of inflammatory priming. Stem Cell Rev. (2012) 8:1188–98. doi: 10.1007/s12015-012-9408-1

93. Mathieu M, Martin-Jaular L, Lavieu G, Thery C. Specificities of secretion and uptake of exosomes and other extracellular vesicles for cell-to-cell communication. Nat Cell Biol. (2019) 21:9–17. doi: 10.1038/s41556-018-0250-9

94. Robbins PD, Morelli AE. Regulation of immune responses by extracellular vesicles. Nat Rev Immunol. (2014) 14:195–208. doi: 10.1038/nri3622

95. Zou X, Zhang G, Cheng Z, Yin D, Du T, Ju G, et al. Microvesicles derived from human Wharton's Jelly mesenchymal stromal cells ameliorate renal ischemia-reperfusion injury in rats by suppressing CX3CL1. Stem Cell Res Ther. (2014) 5:40. doi: 10.1186/scrt428

96. Nojehdehi S, Soudi S, Hesampour A, Rasouli S, Soleimani M, Hashemi SM. Immunomodulatory effects of mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes on experimental type-1 autoimmune diabetes. J Cell Biochem. (2018) 119:9433–43. doi: 10.1002/jcb.27260

97. Bai L, Shao H, Wang H, Zhang Z, Su C, Dong L, et al. Effects of mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes on experimental autoimmune uveitis. Sci Rep. (2017) 7:4323. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-04559-y

98. Yu B, Kim HW, Gong M, Wang J, Millard RW, Wang Y, et al. Exosomes secreted from GATA-4 overexpressing mesenchymal stem cells serve as a reservoir of anti-apoptotic microRNAs for cardioprotection. Int J Cardiol. (2015) 182:349–60. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2014.12.043

99. Aghajani N, Lerman LO, Eirin A. Mesenchymal stem cell-derived extracellular vesicles for kidney repair: current status and looming challenges. Stem Cell Res Ther. (2017) 8:273. doi: 10.1186/s13287-017-0727-7

100. Toh WS, Zhang B, Lai RC, Lim SK. Immune regulatory targets of mesenchymal stromal cell exosomes/small extracellular vesicles in tissue regeneration. Cytotherapy. (2018) 20:1419–26. doi: 10.1016/j.jcyt.2018.09.008

101. Wei Y, Wang D, Jin F, Bian Z, Li L, Liang H, et al. Pyruvate kinase type M2 promotes tumour cell exosome release via phosphorylating synaptosome-associated protein 23. Nat Commun. (2017) 8:14041. doi: 10.1038/ncomms14041

102. Gonzalez-King H, Garcia NA, Ontoria-Oviedo I, Ciria M, Montero JA, Sepulveda P. Hypoxia inducible factor-1alpha potentiates jagged 1-mediated angiogenesis by mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes. Stem Cells. (2017) 35:1747–59. doi: 10.1002/stem.2618

103. Cahill EF, Tobin LM, Carty F, Mahon BP, English K. Jagged-1 is required for the expansion of CD4+ CD25+ FoxP3+ regulatory T cells and tolerogenic dendritic cells by murine mesenchymal stromal cells. Stem Cell Res Ther. (2015) 6:19. doi: 10.1186/s13287-015-0021-5

104. Zhang W, Zhou X, Yao Q, Liu Y, Zhang H, Dong Z. HIF-1-mediated production of exosomes during hypoxia is protective in renal tubular cells. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. (2017) 313:F906–13. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00178.2017

105. Phinney DG, Di Giuseppe M, Njah J, Sala E, Shiva S, St Croix CM, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells use extracellular vesicles to outsource mitophagy and shuttle microRNAs. Nat Commun. (2015) 6:8472. doi: 10.1038/ncomms9472

106. Arslan F, Lai RC, Smeets MB, Akeroyd L, Choo A, Aguor EN, et al. Mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes increase ATP levels, decrease oxidative stress and activate PI3K/Akt pathway to enhance myocardial viability and prevent adverse remodeling after myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury. Stem Cell Res. (2013) 10:301–12. doi: 10.1016/j.scr.2013.01.002

107. Wang X, Liu C, Li S, Xu Y, Chen P, Liu Y, et al. Hypoxia precondition promotes adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells based repair of diabetic erectile dysfunction via augmenting angiogenesis and neuroprotection. PLoS ONE. (2015) 10:e0118951. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0118951

108. Xie J, Xiao D, Xu Y, Zhao J, Jiang L, Hu X, et al. Up-regulation of immunomodulatory effects of mouse bone-marrow derived mesenchymal stem cells by tetrahydrocannabinol pre-treatment involving cannabinoid receptor CB2. Oncotarget. (2016) 7:6436–47. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.7042

109. Chen L, Xu Y, Zhao J, Zhang Z, Yang R, Xie J, et al. Conditioned medium from hypoxic bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells enhances wound healing in mice. PLoS ONE. (2014) 9:e96161. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0096161

110. Kim Y, Jin HJ, Heo J, Ju H, Lee HY, Kim S, et al. Small hypoxia-primed mesenchymal stem cells attenuate graft-versus-host disease. Leukemia. (2018) 32:2672–84. doi: 10.1038/s41375-018-0151-8

111. Fan H, Zhao G, Liu L, Liu F, Gong W, Liu X, et al. Pre-treatment with IL-1beta enhances the efficacy of MSC transplantation in DSS-induced colitis. Cell Mol Immunol. (2012) 9:473–81. doi: 10.1038/cmi.2012.40

112. Kim DS, Jang IK, Lee MW, Ko YJ, Lee DH, Lee JW, et al. Enhanced immunosuppressive properties of human mesenchymal stem cells primed by interferon-gamma. EBio Med. (2018) 28:261–73. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2018.01.002

113. Bartosh TJ, Ylostalo JH, Mohammadipoor A, Bazhanov N, Coble K, Claypool K, et al. Aggregation of human mesenchymal stromal cells (MSCs) into 3D spheroids enhances their antiinflammatory properties. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. (2010) 107:13724–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1008117107

114. Martinez VG, Ontoria-Oviedo I, Ricardo CP, Harding SE, Sacedon R, Varas A, et al. Overexpression of hypoxia-inducible factor 1 alpha improves immunomodulation by dental mesenchymal stem cells. Stem Cell Res Ther. (2017) 8:208. doi: 10.1186/s13287-017-0659-2

115. Fujisawa K, Takami T, Okada S, Hara K, Matsumoto T, Yamamoto N, et al. Analysis of metabolomic changes in mesenchymal stem cells on treatment with desferrioxamine as a hypoxia mimetic compared with hypoxic conditions. Stem Cells. (2018) 36:1226–36. doi: 10.1002/stem.2826

116. Calvani M, Comito G, Giannoni E, Chiarugi P. Time-dependent stabilization of hypoxia inducible factor-1alpha by different intracellular sources of reactive oxygen species. PLoS ONE. (2012) 7:e38388. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0038388

117. Li S, Deng Y, Feng J, Ye W. Oxidative preconditioning promotes bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells migration and prevents apoptosis. Cell Biol Int. (2009) 33:411–8. doi: 10.1016/j.cellbi.2009.01.012

118. Wang Q, Zhu H, Zhou WG, Guo XC, Wu MJ, Xu ZY, et al. N-acetylcysteine-pretreated human embryonic mesenchymal stem cell administration protects against bleomycin-induced lung injury. Am J Med Sci. (2013) 346:113–22. doi: 10.1097/MAJ.0b013e318266e8d8

119. Tan Q, Huang Q, Ma YL, Mao K, Yang G, Luo P, et al. Potential roles of IL-1 subfamily members in glycolysis in disease. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. (2018) 44:18–27. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2018.11.001

120. Andreeva ER, Udartseva OO, Zhidkova OV, Buravkov SV, Ezdakova MI, Buravkova LB. IFN-gamma priming of adipose-derived stromal cells at “physiological” hypoxia. J Cell Physiol. (2018) 233:1535–47. doi: 10.1002/jcp.26046

121. Krampera M, Cosmi L, Angeli R, Pasini A, Liotta F, Andreini A, et al. Role for interferon-gamma in the immunomodulatory activity of human bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells. Stem Cells. (2006) 24:386–98. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2005-0008

122. Li H, Wang W, Wang G, Hou Y, Xu F, Liu R, et al. Interferon-gamma and tumor necrosis factor-alpha promote the ability of human placenta-derived mesenchymal stromal cells to express programmed death ligand-2 and induce the differentiation of CD4(+)interleukin-10(+) and CD8(+)interleukin-10(+)Treg subsets. Cytotherapy. (2015) 17:1560–71. doi: 10.1016/j.jcyt.2015.07.018

123. Ben-Shlomo Kol S, Roeder LM, Resnick CE, Hurwitz A, Payne DW, et al. Interleukin (IL)-1beta increases glucose uptake and induces glycolysis in aerobically cultured rat ovarian cells: evidence that IL-1beta may mediate the gonadotropin-induced midcycle metabolic shift. Endocrinology. (1997) 138:2680–8. doi: 10.1210/endo.138.7.5229

124. Zhao G, Miao H, Li X, Chen S, Hu Y, Wang Z, et al. TGF-beta3-induced miR-494 inhibits macrophage polarization via suppressing PGE2 secretion in mesenchymal stem cells. FEBS Lett. (2016) 590:1602–13. doi: 10.1002/1873-3468.12200

125. Xu C, Yu P, Han X, Du L, Gan J, Wang Y, et al. TGF-beta promotes immune responses in the presence of mesenchymal stem cells. J Immunol. (2014) 192:103–9. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1302164

126. Rodriguez TM, Saldias A, Irigo M, Zamora JV, Perone MJ, Dewey RA. Effect of TGF-beta1 stimulation on the secretome of human adipose-derived mesenchymal stromal cells. Stem Cells Transl Med. (2015) 4:894–8. doi: 10.5966/sctm.2015-0012

127. Guido C, Whitaker-Menezes D, Capparelli C, Balliet R, Lin Z, Pestell RG, et al. Metabolic reprogramming of cancer-associated fibroblasts by TGF-beta drives tumor growth: connecting TGF-beta signaling with “Warburg-like” cancer metabolism and L-lactate production. Cell Cycle. (2012) 11:3019–35. doi: 10.4161/cc.21384

128. Wang C, Silverman RM, Shen J, O'Keefe RJ. Distinct metabolic programs induced by TGF-beta1 and BMP2 in human articular chondrocytes with osteoarthritis. J Orthop Translat. (2018) 12:66–73. doi: 10.1016/j.jot.2017.12.004

129. Bartosh TJ, Ylostalo JH, Bazhanov N, Kuhlman J, Prockop DJ. Dynamic compaction of human mesenchymal stem/precursor cells into spheres self-activates caspase-dependent IL1 signaling to enhance secretion of modulators of inflammation and immunity (PGE2, TSG6, and STC1). Stem Cells. (2013) 31:2443–56. doi: 10.1002/stem.1499

130. Zimmermann JA, Hettiaratchi MH, McDevitt TC. Enhanced immunosuppression of T cells by sustained presentation of bioactive interferon-gamma within three-dimensional mesenchymal stem cell constructs. Stem Cells Transl Med. (2017) 6:223–37. doi: 10.5966/sctm.2016-0044

131. Ylostalo JH, Bartosh TJ, Coble K, Prockop DJ. Human mesenchymal stem/stromal cells cultured as spheroids are self-activated to produce prostaglandin E2 that directs stimulated macrophages into an anti-inflammatory phenotype. Stem Cells. (2012) 30:2283–96. doi: 10.1002/stem.1191

132. Molendijk I, Barnhoorn MC, de Jonge-Muller ES, Mieremet-Ooms MA, van der Reijden JJ, van der Helm D, et al. Intraluminal injection of mesenchymal stromal cells in spheroids attenuates experimental colitis. J Crohns Colitis. (2016) 10:953–64. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjw047

Keywords: MSCs (mesenchymal stromal cells), immunomodulation, metabolic plasticity, biomanufacturing, therapeutic potentials

Citation: Yuan X, Logan TM and Ma T (2019) Metabolism in Human Mesenchymal Stromal Cells: A Missing Link Between hMSC Biomanufacturing and Therapy? Front. Immunol. 10:977. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.00977

Received: 14 February 2019; Accepted: 16 April 2019;

Published: 08 May 2019.

Edited by:

Guido Moll, Charité Medical University of Berlin, GermanyReviewed by:

Peiman Hematti, University of Wisconsin-Madison, United StatesRaghavan Chinnadurai, University of Wisconsin-Madison, United States

Copyright © 2019 Yuan, Logan and Ma. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Teng Ma, dGVuZ0BlbmcuZnN1LmVkdQ==

Xuegang Yuan1

Xuegang Yuan1 Teng Ma

Teng Ma