- 1Division of Rheumatology, Department of Internal Medicine, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, United States

- 2Immunology Program, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, United States

- 3Department of Dermatology, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, United States

Ultraviolet (UV) light is an important environmental trigger for systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) patients, yet the mechanisms by which UV light impacts disease are not fully known. This review covers evidence in both human and murine systems for the impacts of UV light on DNA damage, apoptosis, autoantigen exposure, cytokine production, inflammatory cell recruitment, and systemic flare induction. In addition, the role of the circadian clock is discussed. Evidence is compared in healthy individuals and SLE patients as well as in wild-type and lupus-prone mice. Further research is needed into the effects of UV light on cutaneous and systemic immune responses to understand how to prevent UV-light mediated lupus flares.

Introduction

Ultraviolet (UV) light is a pervasive environmental exposure with pleotropic effects on the skin. Sensitivity to UV light is a shared feature of several autoimmune diseases, including systemic and cutaneous lupus erythematosus (SLE and CLE, respectively), dermatomyositis, and occasionally Sjögren's syndrome. The reported frequency of photosensitivity reaches up to 93% in lupus patients, depending on the underlying disease pathology (1–3), is suggested to be around 50% in dermatomyositis (4), and is poorly documented but reported anecdotally in Sjögren's syndrome. Patients with these disorders can manifest with varied skin reactions including erythema, inflammatory lesions to moderate exposures, and severe skin inflammation and systemic disease flares (especially in SLE) to larger exposures (5, 6). Despite the clinical acknowledgement of photosensitivity, the mechanistic reasons for sensitivity to UV exposure remain unclear. In this review, we discuss the effects of UV light on the skin in both human and murine systems and how disease-associated changes may promote abnormal reactivity and increased inflammation to UV exposure.

Human Healthy and Autoimmune Skin Responses to UV

UV light falls in the spectrum between visible light and gamma irradiation. UVA, UVB, and UVC are divided based on wavelength (UVA = 400–320 nm; UVB = 320–280 nm; UVC = 280–100 nm), with shorter wavelengths associated with higher energy effects. In general the longer wavelengths, such as UVA, which has been shown to have therapeutic potential in SLE patients (7–9), penetrate more deeply in the skin, reaching the dermis, whereas UVB is absorbed almost entirely by the keratinocytes of the epidermis (10). UVC rarely reaches the skin as it is primarily absorbed by atmospheric ozone. Following UV exposure, the keratinocytes act as first responders, trigging inflammatory cytokine, and chemokine production. If the UV exposure is substantial enough, keratinocytes also undergo apoptosis.

UV-Induced DNA Damage and Apoptosis

UV exposure induces DNA damage, which can result in the formation of dimeric photoproducts involving neighboring pyrimidine bases (11–13). UV irradiation can also cause an accumulation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in keratinocytes that results in oxidative damage to DNA, lipids, and proteins and can ultimately induce apoptosis (11, 13–15). Of importance, the oxidative damage to DNA bases can lead to formation of 8-hydroxyguanosine (8-OHG) which has been shown to be immunogenic in patients with lupus erythematosus (LE) and abundantly present in UV-induced LE lesions (16–18).

DNA methylation is also altered by UV exposure, as several groups have shown that UVB irradiation decreases DNA methylation in CD4+ T cells of patients with SLE by inhibiting the catalytic activity of DNA methyltransferase 1 (DNMT1) (19–21). A positive correlation between the levels of DNMT1 expression and global DNA methylation is seen in SLE patients suggesting that aberrant expression of this enzyme is involved in these methylation changes (22). This suppression seems to be mediated by the UVB-induced activation of the aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR) which subsequently inhibits silent mating type information regulation 2 homolog 1 (SIRT1) and DNMT1 activity (21). SIRT1 and AhR have both been suggested to be involved in the pathogenesis of lupus and may provide a link between disease and photosensitivity (21, 23, 24). UV light can cause formation of tryptophan photoproducts that are able to act as AhR agonists (25). Furthermore, activation of AhR correlates with cutaneous expression of interleukin-22 (IL-22), a cytokine that, in the presence of IFNα, can activate STAT1 and upregulate CXCL9 and CXCL10 further contributing to inflammation (24, 26).

High mobility group box 1 protein (HMGB1) is regulated by UV exposure, and serves as a DNA binding protein that plays a role in regulation of transcription. During instances of injury or inflammation, activated macrophages, natural killer cells, and dendritic cells can secrete HMGB1 to help coordinate immune responses by recruiting leukocytes, augmenting production of pro-inflammatory cytokines, and activating NFkB through RAGE and Toll-like receptors (TLRs) (27). HMGB1 can also be released by cells undergoing necrosis or apoptosis and subsequently enhance inflammatory responses (27, 28). SLE patients have increased levels of HMGB1 that correlate with both levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines, including TNFα, IL-6, and IL-1β, and disease activity (29, 30). Following UVB exposure, HMGB1 is released from SLE keratinocytes at an increased rate and in an apoptosis-related manner, which may thus contribute to the development of UV-induced inflammation and lead to skin lesion formation (31).

Following DNA damage, apoptosis is induced in keratinocytes. Research has explored whether SLE patients are more susceptible to this DNA damage. One study, which used immunohistochemistry for cleaved caspase-3, found no difference in epidermal apoptotic cells 24 h after 1x and 2x minimal erythema UV dose in SLE patients (32). However, others have identified increases in apoptotic bodies in the skin of CLE patients after UV treatment when compared with control skin (33). Another group identified increases in TUNEL staining in SLE vs. control skin after UVB; this was also true when SLE vs. normal keratinocytes were treated with UVB in vitro (34). It is important to consider, however, that TUNEL staining may represent other forms of cell death in addition to apoptosis (35–38). CLE lesions themselves also demonstrate increased TUNEL staining, which supports a cell-death phenotype in lesions in vivo (39).

UV- Induced Autoantigen Exposure

UVB irradiation can result in the translocation of Ro/SSA and La/SSB antigens from the nucleus and cytoplasm to the surface of apoptotic human keratinocytes rendering them susceptible to binding by their respective circulating autoantibodies (14, 40–42). Photosensitivity of patients correlates with both the presence of anti-Ro and anti-La autoantibodies and the increased expression of Ro/SSA and La/SSB in keratinocytes (43–46). Both photoprovoked and spontaneous CLE lesions as well as UV-irradiated patient-derived primary keratinocytes show increased Ro52 expression (47).

Another autoantigen suggested to be involved in lupus is interferon-inducible protein 16 (IFI16), a DNA binding protein with diverse roles that is normally localized to the nucleus (48). SLE patient serum often has high titers of anti-IFI16 antibodies, with one study finding these antibodies could be detected in 29% of sera collected from 374 SLE patients (49, 50). Upon UVB irradiation of keratinocytes, IFI16 is redistributed to the cytoplasm and the extracellular space, leaving it exposed for possible immune recognition by autoantibodies and potentially contributing to the inflammatory environment associated with photosensitivity (50). UVB has also been shown to increase autoantibody binding to other autoantigens including Sm, RNP, Ku, and ribosomal-P (51–53). In particular, anti-Sm and anti-ribosomal-P antibodies are strongly associated with photosensitivity and disease activity in lupus patients (53–55).

Following induction of apoptosis, reduced clearance of apoptotic cells in lupus skin has also been suggested to contribute to induction of inflammatory lesions, likely through increased exposure to auto-antigens. Most studies support dysfunctional and reduced phagocytosis in SLE patients, ultimately resulting in reduced clearance of apoptotic cells (56–58). Part of this phenotype may be regulated by UVB as HMGB1can skew macrophage polarization toward an M1-like phenotype diminishing their ability to phagocytose apoptotic cells (59).

Another mechanism regulating apoptotic clearance is opsonization by complement. Homozygous deficiency of complement proteins of the classical pathway is associated with SLE pathogenesis (60, 61). The strongest associations are seen with proteins involved in the earliest steps of the pathway including C1q and C4, with as many as 75–90% of patients with a homozygous deficiency of these proteins reported to have SLE or lupus-like disease (61). A study of Swedish SLE patients found that 16% had homozygous C4A deficiency and photosensitivity was more common among these patients (62). Mechanisms of lupus risk associated with complement deficiencies may be related to decreased apoptotic clearance. For example, C1q binds to the nucleolus of cells undergoing UV-induced apoptosis resulting in activation of C1r/C1s proteases that under normal circumstances facilitate degradation of these potential autoantigens (63–66). In addition, C1q provides anti-inflammatory functions in macrophages (67) and suppresses type I interferon (IFN) production (68, 69), an important component of CLE lesions. Importantly, single nucleotide polymorphisms in C2, particularly in Chinese SLE patients, are strongly associated with photosensitivity among other clinical manifestations of disease (70). These data indicate that defective complement pathways resulting in deficient clearance of apoptotic cells are likely involved in increased photosensitivity and lesion development in lupus patients.

UV-Induced Inflammation

Cytokines

UV exposure may have repressive or activating functions on cytokine production depending on the context. In normal keratinocytes, UVB upregulates suppressor of cytokine signaling (SOCS) 1 and 3 and downregulates activation of STAT1, resulting in resistance to activation effects of IFN-γ (71, 72). Following UVB exposure, cutaneous production of type I IFNs increases, and this may have suppressive effects on inflammation via upregulation of tristetraprolin (73). In addition, narrow-band UVB treatment can be used as a treatment for some inflammatory skin diseases, such as psoriasis, and can result in downregulation of IL-17, IL-12, and IFN-regulated pathways (74, 75).

In patients with autoimmune diseases, however, UV light may trigger inflammatory responses. This may be due in part to chronic overexpression of type I IFNs. Increased levels of type I IFNs found in SLE patients correlate with systemic disease activity and severity (76). Further, circulating IFN activity also correlates with cutaneous disease activity in CLE patients (77). Supporting a role for type I IFN in SLE skin, a recent trial of anifrolumab, which blocks type I IFN receptor signaling, shows promise for improvement in CLE lesions (78). At baseline, SLE patients demonstrate an increased IFN signature in their “healthy” keratinocytes (79), likely mediated by chronic overproduction of IFNκ (34, 80, 81). In the skin, type I IFNs stimulate chemokine production and activate adaptive immune responses (82). Indeed, supernatants from SLE>control keratinocytes treated with UVB stimulate the activation of dendritic cells in an IFN-dependent manner (34). Further IFN gene expression in the epidermis correlates with upregulation of the adhesion molecules E-selectin and ICAM-1 that enhance T cell and macrophage recruitment into the skin (83–86). Type I IFNs may also come from non-epithelial sources, including plasmacytoid dendritic cells (pDCs: see below). Further, genomic DNA from UV-irradiated epithelial cells can induce primary human monocytes to secrete more IFNα than those exposed to DNA from non-irradiated epithelial cells (18). This suggests that a UV-induced modification of DNA is at least partially responsible for upregulation of type I IFNs. Lending more support to this idea, colocalization of 8-OHG and MxA, an IFN-upregulated gene, is seen in the epidermis of UV-induced LE lesions (18).

Integration of the 8-OHG and IFN response may occur via stimulator of interferon genes (STING). STING coordinates signals from cytoplasmic DNA sensors, and is negatively regulated by the pro-autophagic protein unc-51-like kinase 1 (ULK1) (87). Upon UV-induced DNA damage, ULK1 stability is disrupted by the loss of the activating molecule in Beclin-1-regulated autophagy (AMBRA1) (88). The resulting increase in STING activity causes activation of interferon regulatory factor 3 (IRF3), potentiating type I IFN secretion and exacerbating autoimmunity in response to UV exposure (88).

Another contributor to skin interferons may be the lupus band, which consists of nuclear debris, complement, DNA and IgG and IGM autoantibodies and is induced by ultraviolet light (89). Positive lupus band testing is found at the dermo-epidermal junction in many systemic and cutaneous lupus patients (90, 91), and its presence positively correlates with disease activity (92). Because immune complexes stimulate IFNα production by pDCs (93), and this is further positively regulated by inflammatory cells present in lupus skin (94–96), UV-induced immune complexes may contribute to photosensitive responses. In addition, immune complexes stimulate inflammasome activation (97, 98) and expansion of B cell subsets (99), which may amplify the inflammatory response in the skin once started.

Elevated levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines, including IL-6, TNFα, and IL-1β, in SLE patients are associated with increased disease activity (100). UVB irradiation has been shown to further increase levels of TNFα in normal human keratinocytes, likely mediated through upregulation of IL-1α, (101, 102). UVB exposure induces more IL-6 production from SLE keratinocytes compared to those from healthy controls (81). This difference is driven by increased production of type I IFNs, as control keratinocytes treated with type I IFNs increase their IL-6 production, while lupus keratinocytes treated with type I IFN blockade have decreased IL-6 production (81). More specifically, keratinocyte specific secretion of IFNκ increases after UVB treatment of lupus keratinocytes and neutralization of this type I IFN abrogates IL-6 production (81). Additionally, increased IL-1β and TNFα expression promotes release of inflammatory chemokines CCL5, CCL22, CXCL8, and CCL27 by epidermal keratinocytes and this may support leukocyte recruitment, especially memory T cells, into the skin following UV exposure (82).

Tumor necrosis factor- (TNF-) like weak inducer of apoptosis (TWEAK) and its receptor fibroblast growth factor-inducible 14 (Fn14) play a role in modulation of inflammatory responses in the skin by activating NFκB in keratinocytes (103). Activation of the TWEAK-Fn14 signaling pathway is significantly increased in lesional skin of SLE patients. Additionally, mRNA expression of TWEAK, Fn14, and several genes turned on by this pathway including CCL5, monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1) and CXCL10 is higher in these lesions compared to healthy controls (103). Overlap of Fn14 and Ro52 is observed in the upper epidermis of lesional skin suggesting a possible role for TWEAK-Fn14 activation in Ro-52 mediated photosensitivity of CLE patients, similar to what has been observed in mouse models (104).

Immune Cell Recruitment

UV exposure induces recruitment of innate and adaptive immune cells to the skin. Neutrophils are one of the first cell populations recruited to healthy skin after UV exposure. Once present, they secrete IL-10 which provides immunosuppressant effects (105). Intriguingly, in photosensitive disorders, such as polymorphic light eruption, recruitment of neutrophils is diminished and it is hypothesized that the immunosuppressive functions of neutrophils are subsequently lost (106). Localized O2 depletion by infiltrating neutrophils undergoing respiratory bursts is important for resolution of mucosal inflammation; therefore, loss of this hypoxic environment resulting from decreased neutrophil recruitment may play a role in the increased inflammation seen in lupus skin (107). In CLE lesions, neutrophils have been shown to release neutrophil extracellular traps “NETs” which may participate in tissue damage (108). These NETs are interferonogenic and may contribute to pro-inflammatory, IFN rich environment in lupus skin lesions (109).

Neutrophils from SLE patients have a lowered ability to produce ROS when compared with healthy controls and this decrease correlates with disease severity (110). Polymorphisms in Ncf1, a gene encoding a component of the NADPH oxidase complex, are found in SLE patients and these are associated with decreased ROS generation in neutrophils and an increase in expression of type I IFN regulated genes (111). It is not yet known if UV irradiation further affects the capacity of lupus neutrophils to produce ROS. Additionally, in MRL/lpr lupus-prone mice, treatment with MitoTEMPO, a mitochondrial ROS scavenger, results in decreased neutrophil NETosis, immune complex deposition in the kidney, and type I IFN production; however, the effect in UV-irradiated skin is not known (109).

PDCs are a subset of dendritic cell shown to accumulate in cutaneous lupus lesions and locally produce IFNα (112). UV triggers production of CXCL9, CXCL10, and CXCL11 chemokines that attract pDCs and other inflammatory cells (82). Following UV exposure, pDCs accumulate at the dermoepidermal junction to a greater extent in SLE patients vs. healthy controls (80). Increased translocation of autoantigens such as RNA and DNA fragments by UV can result in formation of immune complexes that can subsequently be internalized via FcγRII on pDCs, activate endosomal TLR7/9, and induce IFNα production by the pDC (113–115). This initiates an amplification loop in which IFNα further promotes chemokine and IFNκ expression in the skin, recruiting additional leukocytes, and furthering inflammation that contributes to cutaneous lesion development (34, 82).

Mast cells may also be involved in UV responses in the skin. The number of mast cells in CLE skin lesions is significantly higher than in normal skin and even higher in sun-exposed diseased skin compared to sun-protected diseased skin. Recruitment of mast cells, which have been shown to produce matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), can be induced by IL-15 and CCL5 (116–119). MMPs are a family of enzymes secreted by a variety of cell types that are known to play a crucial role in processes ranging from tissue degradation and repair to apoptosis and inflammation (120). Sera of lupus patients often have elevated levels of several MMPs and lower levels of tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases (TIMP)-1 compared to healthy controls (121–124). TIMP-1 is also shown to be downregulated in LE skin lesions while TIMP-3, which may promote keratinocyte apoptosis, is upregulated (125, 126). Together, this suggests that UV light may promote mast cell recruitment and MMP production that may be further exacerbated in lupus skin (127).

T cells are also recruited after UVB exposure. Skin resident T cells have a protective role in limiting DNA damage after UVB exposure (128). UVB-mediated activation of regulatory T cells may participate in immunosuppressive effects of UV light (129). Intriguingly, a recent report suggests that T cells may have innate photosensing abilities that discriminate the wavelength of light and in turn modulate chemotactic responses (130). In lupus patients, UV exposure results in accumulation of T cells at the dermoepidermal junction during lesion onset and this infiltration persists in later lesions (131, 132).

Circadian Clock and UV-Induced Skin Inflammation

The circadian clock is a recently understood mechanism that regulates many physiological processes including those of the immune system. A recent study showed that circadian clock-controlled cryptochromes (CRY) 1 and 2 are differentially expressed in narrow band-UVB irradiated human skin with lower levels of CRY2 associating with increased erythema (133). It may be that CRY2 plays a role in protection against skin damage caused by UV exposure (133). CRY2 is involved with regulation of c-MYC degradation and, therefore, may abrogate UV-induced keratinocyte apoptosis (134). It is intriguing to surmise that pathogenesis and photosensitivity of SLE patients may be partially explained by decreased CRY2 expression that inhibits protection against UV, however, further studies will need to be carried out to determine whether disease is associated with differential cryptochrome expression. Studies in mice have also suggested the circadian clock may be a contributing factor in autoimmunity (135).

Wild Type and Autoimmune Murine Models of UV Exposure

Although lupus patients experience sensitivity to UV exposure and display both local and systemic flares, understanding the mechanism is challenging due to variability between patients (136). Thus, murine models are ideal for understanding the mechanisms regulating both the local and systemic UV response with the caveat that no one animal model will mimic every aspect of human disease perfectly. Like in humans, UVA has shown therapeutic effects for autoimmune conditions in mice (137). However, most studies that examine the mechanism behind UV damage utilize UVB; thus, mechanisms involved in local and systemic response following UVB treatment will be reviewed below.

UV-Induced DNA Damage and Apoptosis

Similar to humans, mice also exhibit increased apoptosis and DNA damage in the skin after UVB exposure. In murine skin, keratinocytes and fibroblasts are susceptible to UVB-induced apoptosis (138–141). Both TLR and TWEAK-Fn14 signaling pathways have been shown to regulate this process. TLR 4-MyD88 signaling pushes cells to undergo apoptotic vs. necrotic cell death pathways after UVB exposure via caspase 3 activation, as mice deficient for either TLR4 or MyD88 display increased necroptosis markers and TNFα production (142). The TWEAK-Fn14 signaling pathway has also been investigated in mice for its role in apoptosis, since Fn14 is upregulated on keratinocytes following UVB exposure. Knockout (KO) of Fn14 led to protection from UVB induced skin inflammation (143), while the addition of TWEAK led to increased apoptosis of keratinocytes from UV treated MRL/lpr mice (144). UV exposure also led to increased DNA damage/release in both wild-type mice and lupus-prone mice, though lupus-prone MRL/lpr mice demonstrate increased susceptibility to UV-mediated DNA release (145). This UV induced DNA damage may play a role in lesion development, as TREX1 KO mice, which lack cytosolic DNase, develop lupus-like lesions (146). Further, UV-modified DNA can induce CLE-like lesions when injected into the skin of MRL/lpr mice (18). These data suggest a role for TLR and TWEAK-Fn14 signaling in mediating increased apoptosis within the skin of lupus-prone mice following UVB exposure. Also the increased DNA damage following UVB exposure plays a part in lesion development. Though DNA damage and apoptosis result from UV irradiation, the differences between wild-type mice and lupus-prone mice regarding mechanisms of immune activation remains understudied.

UV-Induced Autoantigen Exposure

Exposure of autoantigens at the dermoepidermal junction also occurs in lupus-prone mice following UVB treatment. One study identified immune complexes and antibodies to desmoglein 3 at the dermoepidermal junction in NZB/NZW F1 mice exposed to 500 mJ/cm2 UVB every other day (147). While production of anti-Ro antibodies is rare in murine lupus models, UVB induces similar externalization of the Ro autoantigen in mice. Indeed, injection of Ro+ serum from patients with subacute cutaneous lupus into Balb/c mice exposed to UVB results in deposition of anti-Ro antibodies at the dermoepidermal junction (148). Further studies should address the role of autoantibodies in murine lupus models of UV-mediated skin inflammation.

UV-Induced Inflammation

Cytokines

Murine cytokine production after UVB is similar to that seen in human skin: TNFα, IL-6, IL-1, IL-23, and type I IFNs are all increased (139, 142, 149). Most of the cytokine induction is fairly rapid: TNFα and IL-6 production occurs 8–24 h after UVB exposure (150). However, data examining their role in UVB-mediated changes remain limited. In lupus-prone mice, IFN-regulated gene Ifi202 has a pro-inflammatory effect on apoptosis following UVB stimulation (151), but in wild-type mice, IFNs demonstrate a protective effect in the skin as mice lacking the type I IFN receptor have greater inflammatory responses (152). UVB induces colony-stimulating factor-1 (CSF1) which likely enhances macrophage recruitment to the skin (153). Following UVB, TNFα has a pro-inflammatory effect by increasing apoptosis of keratinocytes (149, 154, 155). Though studies on the role of IL-1 family members following UV exposure are limited, mice transgenic for IL-1α demonstrate skin inflammation (156). IL-6 −/− mice demonstrate decreased epidermal proliferation after UVB and also decreased systemic IL-10, suggesting IL-6 may have both epidermal and immune regulatory functions (157). IL-23 in wild-type mice has a protective effect on UVB-mediated damage by reducing DNA damage and increasing T regulatory cells (158); however the function of this cytokine has not been examined in lupus-prone mice following UVB stimulation. Intriguingly, neutralizing antibodies to IL-23 have a protective effect in lupus-prone mice, which suggests a pro-inflammatory function for this cytokine after UVB stimulation (159). Further exploration into the role of these cytokines following UVB exposure in wild-type and lupus-prone mice may yield novel data for therapeutic development for photosensitivity.

Immune Cell Recruitment

Epidermal damage from UVB exposure results in upregulation of chemokines and recruitment of neutrophils, monocytes, macrophages, dendritic cells and T cells (140, 143, 160). The dose of exposure regulates the inflammatory response. Hairless mice exposed to low dose (20 mJ/cm2) UVB demonstrate increased epidermal thickness but not inflammation. The same mice exposed to a single high dose (400 mJ/cm2) demonstrate neutrophil and macrophage recruitment (161). C57BL/6 mice exposed to two doses of 500 mJ/cm2 of UVB also demonstrate infiltration of pDCs within 24 h and macrophages and neutrophils after 24–78 h (162). In wild-type mice, CD4+ T cells and CD8+ T cells exhibit pro-inflammatory functions through production of IFNγ following UVB stimulation (160); this inflammation is downregulated via induction of T regulatory cells in the skin (163). IFNα-producing monocytes are recruited to the skin in wild-type mice following UVB exposure, and they also exhibit a negative regulatory effect on UVB-driven inflammation via type I IFN-mediated pathways (152). Resident Langerhans cells are essential to resolution of UVB induced skin inflammation through their phagocytosis of apoptotic keratinocytes (160) and through promotion of epidermal growth factor receptor signaling (164); thus, they also exhibit an anti-inflammatory role.

The effect of UVB in mice with a propensity for autoimmune conditions is less well-studied. In lupus-prone MRL/lpr mice, markers of neutrophil and macrophage infiltration are present after UVB, but how this compares with wild-type mice was not evaluated (143). Other studies have compared effects in lupus-prone vs. wild type mice. Increased CD8+ and CD4+ cells were noted in MRL/lpr vs. Balb/c mice after 2 and 6 days of 500 mJ/cm2 UVB treatment (153). Production of chimerin and recruitment of pDCs to the skin after UVB exposure is increased in MRL/lpr vs. wild-type mice (162). Ex vivo irradiation of lymph nodes from lupus-prone (both NZB/NZW F1 and MRL/lpr) vs. wild-type mice exhibited greater upregulation of ICAM-1 and LFA-1, which promotes migration of immune cells into the tissues (139). These studies have generated a preliminary understanding of the differential effects of UVB in lupus-prone vs. wild-type mice, but additional research is needed.

UV-Induced Systemic Disease Flares

Anecdotal and case report data support a link between cutaneous UVB exposure and induction of systemic disease flares in patients (5, 6). This connection between the cutaneous and systemic immune system has not been well characterized in human or murine models [reviewed in (165)]. To date the main lupus-prone mouse model that has demonstrated systemic responses to UV is BXSB male mice, which carry an additional copy of TLR7 as part of the Yaa locus (166). In this strain, daily exposure to 400 mJ/cm2 full spectrum UV for 1 week resulted in 66% of mice succumbing to death after 2 weeks. This level of irradiation did not impair survival in Balb/c, MRL/lpr or (NZBxNZW)F1 mice. Chronic exposure to 120 mJ/cm2 thrice weekly also resulted in >85% lethality after 4 weeks of treatment in male BXSB mice. Death in the male BXSB mice was accompanied by changes consistent with lupus nephritis (166). Whether it is TLR7 driving this phenotype has not been elucidated, but stimulation of TLR7 in Balb/c mice with topical TLR7 agonist for 2 weeks followed by UVB resulted in rising autoantibody titers compared to UVB only-treated mice (167), and TLR7 stimulation itself can promote systemic disease flares(168). This suggests that TLR7 signaling may have a role in UVB-mediated systemic immune activation. However, epidermal damage itself may be sufficient to drive lupus flares in lupus-prone mice (169), so the effects of UVB on systemic immune activation may be multivariate.

Sensing of UVB-modified nucleic acids may contribute to systemic flare development following UVB exposure. For example, injection of UVB-induced apoptotic DNA in wild-type and lupus-prone MRL/lpr mice led to development of lupus-like characteristics such as increased dsDNA antibodies and proteinuria (170, 171). Hypomethylation of DNA seems to be important for this process (171). It is tempting to speculate that these systemic effects may be secondary to STING activation as UVB-modified DNA is resistant to degradation by TREX1 and is able to induce IFN responses and cutaneous lupus-like lesions when injected into the ear of MRL/lpr mice (18). Further exploration is needed to understand the role of UVB-mediated DNA changes in driving systemic immune responses in SLE.

Summary

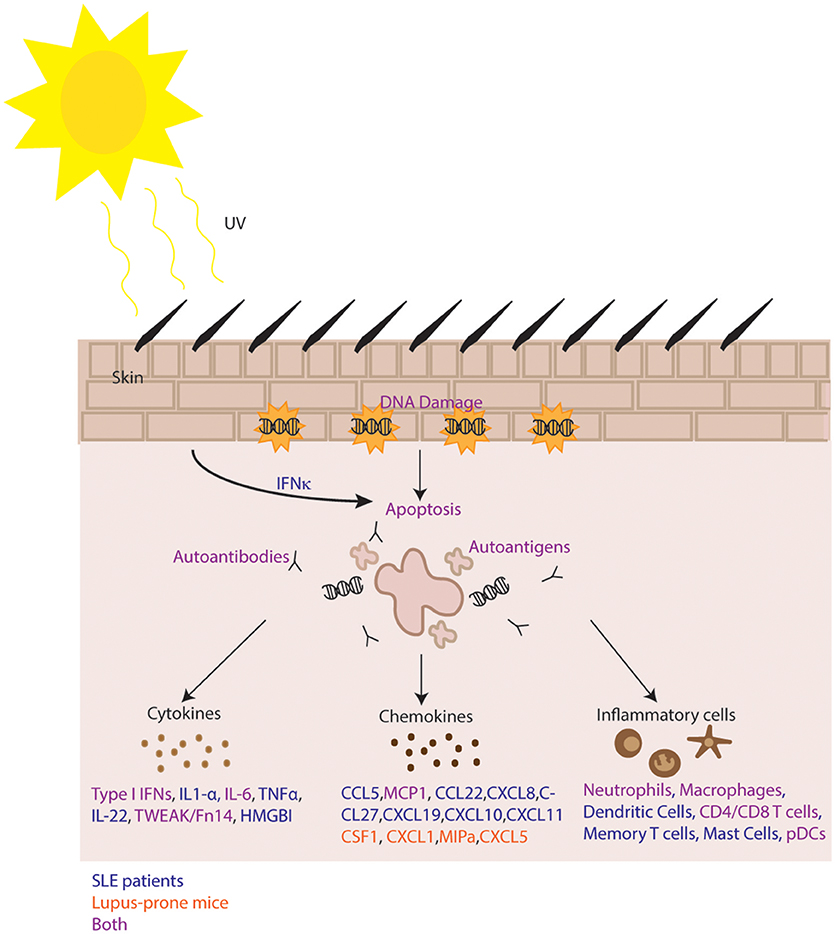

UV irradiation leads to a complex sequence of events in the skin that generates varied inflammatory changes depending on the target (summarized in Figure 1). UV exposure triggers ROS production, DNA damage, and apoptosis that can result in autoantigen translocation to the surface of keratinocytes where they are exposed for immune recognition by autoantibodies. Impaired or inflammatory clearance of these apoptotic cells in SLE patients may occur due to decreased levels of complement proteins and altered complement function. UV exposure modifies DNA and also activates STING to increase production of type I IFNs and other pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines that promote leukocyte recruitment into the skin, further enhancing disease progression and lesion formation. While there is a growing body of knowledge regarding type I IFNs and lupus, the specific sources of these IFNs in the skin as well as the roles they play in processes such as UV-induced apoptosis and immune system activation are yet to be fully understood. Additionally, due to limited knowledge of the changes induced in immune cell populations following UV exposure of lupus patients and lupus-prone mice, further studies will need to elucidate the specific mechanisms that may be at play.

Figure 1. Summary of mechanisms of photosensitivity. In lupus, increased IFN kappa promotes UV-mediated apoptosis resulting in immune complex formation, autoantigen exposure and release of numerous inflammatory cytokines and chemokines. Infiltration of inflammatory cells follows and is perpetuated by inhibition of negative regulatory mechanisms. Pathways with evidence in both human and murine systems are shown in purple. Human only pathways are shown in blue, and murine-specific pathways are shown in orange.

Author Contributions

SJW, SNE, JEG, and JMK participated in the writing and editing of the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest Statement

JMK is an Associate Editor for Frontiers in Immunology.

The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health via the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases under Award R01AR071384 (to JMK), the Rheumatology Research Foundation via an Innovative Research Award (to JMK), and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Research Training in Experimental Immunology Training Grant under award T32AI007413.

Abbreviations

CLE, cutaneous lupus erythematosus; IFN, interferon; pDCs, plasmacytoid dendritic cells; ROS, reactive oxygen species; SLE, systemic lupus erythematosus; TLR, toll-like receptor; UV, ultraviolet.

References

1. Hasan T, Nyberg F, Stephansson E, Puska P, Hakkinen M, Sarna S, et al. Photosensitivity in lupus erythematosus, UV photoprovocation results compared with history of photosensitivity and clinical findings. Br J Dermatol. (1997) 136:699–705. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1997.tb03655.x

2. Kuhn A, Sonntag M, Richter-Hintz D, Oslislo C, Megahed M, Ruzicka T, et al. Phototesting in lupus erythematosus tumidus–review of 60 patients. Photochem Photobiol. (2001) 73:532–6. doi: 10.1562/0031-8655(2001)073<0532:PILETR>2.0.CO;2

3. Sanders CJ, Van Weelden H, Kazzaz GA, Sigurdsson V, Toonstra J, Bruijnzeel-Koomen CA. Photosensitivity in patients with lupus erythematosus: a clinical and photobiological study of 100 patients using a prolonged phototest protocol. Br J Dermatol. (2003) 149:131–7. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.2003.05379.x

4. Dourmishev L, Meffert H, Piazena H. Dermatomyositis: comparative studies of cutaneous photosensitivity in lupus erythematosus and normal subjects. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. (2004) 20:230–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0781.2004.00115.x

5. Pirner K, Rubbert A, Salinger R, Kalden JR, Manger B. [Significance of ultraviolet light in the pathogenesis of systemic lupus erythematosus: case report and discussion of the literature]. Z Rheumatol. (1992) 51:20–4.

6. Fruchter O, Edoute Y. First presentation of systemic lupus erythematosus following ultraviolet radiation exposure in an artificial tanning device. Rheumatology (2005) 44:558–9. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keh523

7. Mcgrath H, Martinez-Osuna P, Lee FA. Ultraviolet-A1 (340-400 nm) irradiation therapy in systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus (1996) 5:269–74. doi: 10.1177/096120339600500405

8. Polderman MC, Van Kooten C, Smit NP, Kamerling SW, Pavel S. Ultraviolet-A (UVA-1) radiation suppresses immunoglobulin production of activated B lymphocytes in vitro. Clin Exp Immunol. (2006) 145:528–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2006.03136.x

9. Jabara B, Dahlgren M, Mcgrath H Jr. Interstitial lung disease and pulmonary hypertension responsive to low-dose ultraviolet A1 irradiation in lupus. J Clin Rheumatol. (2010) 16:188–9. doi: 10.1097/RHU.0b013e3181df822d

10. D'orazio J, Jarrett S, Amaro-Ortiz A, Scott T. UV radiation and the Skin. Int J Mol Sci. (2013) 14:12222–12248. doi: 10.3390/ijms140612222

11. De Gruijl FR, Van Kranen HJ, Mullenders LH. UV-induced DNA damage, repair, mutations and oncogenic pathways in skin cancer. J Photochem Photobiol B (2001) 63:19–27. doi: 10.1016/S1011-1344(01)00199-3

12. Ravanat JL, Douki T, Cadet J. Direct and indirect effects of UV radiation on DNA and its components. J Photochem Photobiol B (2001) 63:88–102. doi: 10.1016/S1011-1344(01)00206-8

13. Lee CH, Wu SB, Hong CH, Yu HS, Wei YH. Molecular mechanisms of UV-induced apoptosis and its effects on skin residential cells: the implication in UV-based phototherapy. Int J Mol Sci. (2013) 14:6414–35. doi: 10.3390/ijms14036414

14. Lawley W, Doherty A, Denniss S, Chauhan D, Pruijn G, Van Venrooij WJ, et al. Rapid lupus autoantigen relocalization and reactive oxygen species accumulation following ultraviolet irradiation of human keratinocytes. Rheumatology (Oxford) (2000) 39:253–61. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/39.3.253

15. Shah D, Mahajan N, Sah S, Nath SK, Paudyal B. Oxidative stress and its biomarkers in systemic lupus erythematosus. J Biomed Sci. (2014) 21:23. doi: 10.1186/1423-0127-21-23

16. Garg DK, Moinuddin Ali R. Hydroxyl radical modification of polyguanylic acid: role of modified guanine in circulating SLE anti-DNA autoantibodies. Immunol Invest. (2003) 32:187–99. doi: 10.1081/IMM-120022978

17. Khan F, Khan F, Ali R. Immunogenicity of DNA modified by singlet oxygen: implications in systemic lupus erythematosus and cancer. Biotechnol Appl Biochem. (2007) 46:97–103. doi: 10.1042/BA20060113

18. Gehrke N, Mertens C, Zillinger T, Wenzel J, Bald T, Zahn S, et al. Oxidative damage of DNA confers resistance to cytosolic nuclease TREX1 degradation and potentiates STING-dependent immune sensing. Immunity (2013) 39:482–95. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.08.004

19. Wu Z, Li X, Qin H, Zhu X, Xu J, Shi W. Ultraviolet B enhances DNA hypomethylation of CD4+ T cells in systemic lupus erythematosus via inhibiting DNMT1 catalytic activity. J Dermatol Sci. (2013) 71:167–73. doi: 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2013.04.022

20. Zhu X, Li F, Yang B, Liang J, Qin H, Xu J. Effects of ultraviolet B exposure on DNA methylation in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Exp Ther Med. (2013) 5:1219–25. doi: 10.3892/etm.2013.960

21. Wu Z, Mei X, Ying Z, Sun Y, Song J, Shi W. Ultraviolet B inhibition of DNMT1 activity via AhR activation dependent SIRT1 suppression in CD4+ T cells from systemic lupus erythematosus patients. J Dermatol Sci. (2017) 86:230–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2017.03.006

22. Qin HH, Zhu XH, Liang J, Yang YS, Wang SS, Shi WM, et al. Associations between aberrant DNA methylation and transcript levels of DNMT1 and MBD2 in CD4+T cells from patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Australas J Dermatol. (2013) 54:90–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-0960.2012.00968.x

23. Sequeira J, Boily G, Bazinet S, Saliba S, He X, Jardine K, et al. sirt1-null mice develop an autoimmune-like condition. Exp Cell Res. (2008) 314:3069–74. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2008.07.011

24. Dorgham K, Amoura Z, Parizot C, Arnaud L, Frances C, Pionneau C, et al. Ultraviolet light converts propranolol, a nonselective beta-blocker and potential lupus-inducing drug, into a proinflammatory AhR ligand. Eur J Immunol. (2015) 45:3174–87. doi: 10.1002/eji.201445144

25. Rannug A, Rannug U, Rosenkranz HS, Winqvist L, Westerholm R, Agurell E, et al. Certain photooxidized derivatives of tryptophan bind with very high affinity to the Ah receptor and are likely to be endogenous signal substances. J Biol Chem. (1987) 262:15422–7.

26. Bachmann M, Ulziibat S, Hardle L, Pfeilschifter J, Muhl H. IFNalpha converts IL-22 into a cytokine efficiently activating STAT1 and its downstream targets. Biochem Pharmacol. (2013) 85:396–403. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2012.11.004

27. Lotze MT, Tracey KJ. High-mobility group box 1 protein (HMGB1): nuclear weapon in the immune arsenal. Nat Rev Immunol. (2005) 5:331–42. doi: 10.1038/nri1594

28. Bell CW, Jiang W, Reich CF III, Pisetsky DS. The extracellular release of HMGB1 during apoptotic cell death. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. (2006) 291:C1318–25. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00616.2005

29. Barkauskaite V, Ek M, Popovic K, Harris HE, Wahren-Herlenius M, Nyberg F. Translocation of the novel cytokine HMGB1 to the cytoplasm and extracellular space coincides with the peak of clinical activity in experimentally UV-induced lesions of cutaneous lupus erythematosus. Lupus (2007) 16:794–802. doi: 10.1177/0961203307081895

30. Lu M, Yu S, Xu W, Gao B, Xiong S. HMGB1 promotes systemic lupus erythematosus by enhancing macrophage inflammatory response. J Immunol Res. (2015) 2015:946748. doi: 10.1155/2015/946748

31. Abdulahad DA, Westra J, Reefman E, Zuidersma E, Bijzet J, Limburg PC, et al. High mobility group box1 (HMGB1) in relation to cutaneous inflammation in systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). Lupus (2013) 22:597–606. doi: 10.1177/0961203313483377

32. Reefman E, Kuiper H, Jonkman MF, Limburg PC, Kallenberg CG, Bijl M. Skin sensitivity to UVB irradiation in systemic lupus erythematosus is not related to the level of apoptosis induction in keratinocytes. Rheumatology (Oxford) (2006) 45:538–44. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kei249

33. Gaipl US, Munoz LE, Grossmayer G, Lauber K, Franz S, Sarter K, et al. Clearance deficiency and systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). J Autoimmun. (2007) 28:114–21. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2007.02.005

34. Sarkar M, Hile G, Tsoi L, Xing X, Liu J, Liang Y, et al. Photosensitivity and type I IFN responses in cutaneous lupus are driven by epidermal derived interferon kappa. Ann Rheum Dis. (2018) 77:1653–664. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2018-213197

35. Charriaut-Marlangue C, Ben-Ari Y. A cautionary note on the use of the TUNEL stain to determine apoptosis. Neuroreport (1995) 7:61–4. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199512000-00014

36. Grasl-Kraupp B, Ruttkay-Nedecky B, Koudelka H, Bukowska K, Bursch W, Schulte-Hermann R. In situ detection of fragmented DNA (TUNEL assay) fails to discriminate among apoptosis, necrosis, and autolytic cell death: a cautionary note. Hepatology (1995) 21:1465–8.

37. Ohno M, Takemura G, Ohno A, Misao J, Hayakawa Y, Minatoguchi S, et al. “Apoptotic” myocytes in infarct area in rabbit hearts may be oncotic myocytes with DNA fragmentation: analysis by immunogold electron microscopy combined with In situ nick end-labeling. Circulation (1998) 98:1422–30. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.98.14.1422

38. Kawashima K, Doi H, Ito Y, Shibata MA, Yoshinaka R, Otsuki Y. Evaluation of cell death and proliferation in psoriatic epidermis. J Dermatol Sci. (2004) 35:207–14. doi: 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2004.05.008

39. Saenz-Corral CI, Vega-Memije ME, Martinez-Luna E, Cuevas-Gonzalez JC, Rodriguez-Carreon AA, De La Rosa JJ, et al. Apoptosis in chronic cutaneous lupus erythematosus, discoid lupus, and lupus profundus. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. (2015) 8:7260–5.

40. Furukawa F, Kashihara-Sawami M, Lyons MB, Norris DA. Binding of antibodies to the extractable nuclear antigens SS-A/Ro and SS-B/La is induced on the surface of human keratinocytes by ultraviolet light (UVL): implications for the pathogenesis of photosensitive cutaneous lupus. J Invest Dermatol. (1990) 94:77–85. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12873930

41. Jones SK. Ultraviolet radiation (UVR) induces cell-surface Ro/SSA antigen expression by human keratinocytes in vitro: a possible mechanism for the UVR induction of cutaneous lupus lesions. Br J Dermatol. (1992) 126:546–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1992.tb00098.x

42. Wang B, Dong X, Yuan Z, Zuo Y, Wang J. SSA/Ro antigen expressed on membrane of UVB-induced apoptotic keratinocytes is pathogenic but not detectable in supernatant of cell culture. Chin Med J (Engl). (1999) 112:512–5.

43. Mond CB, Peterson MG, Rothfield NF. Correlation of anti-Ro antibody with photosensitivity rash in systemic lupus erythematosus patients. Arthritis Rheum. (1989) 32:202–4. doi: 10.1002/anr.1780320213

44. Mchugh N, James I, Maddison P. Clinical significance of antibodies to a 68 kDa U1RNP polypeptide in connective tissue disease. J Rheumatol. (1990) 17:1320–8.

45. Ioannides D, Golden BD, Buyon JP, Bystryn JC. Expression of SS-A/Ro and SS-B/La antigens in skin biopsy specimens of patients with photosensitive forms of lupus erythematosus. Arch Dermatol. (2000) 136:340–6. doi: 10.1001/archderm.136.3.340

46. Menendez A, Gomez J, Caminal-Montero L, Diaz-Lopez JB, Cabezas-Rodriguez I, Mozo L. Common and specific associations of anti-SSA/Ro60 and anti-Ro52/TRIM21 antibodies in systemic lupus erythematosus. ScientificWorldJournal (2013) 2013:832789. doi: 10.1155/2013/832789

47. Oke V, Vassilaki I, Espinosa A, Strandberg L, Kuchroo VK, Nyberg F, et al. High Ro52 expression in spontaneous and UV-induced cutaneous inflammation. J Invest Dermatol. (2009) 129:2000–10. doi: 10.1038/jid.2008.453

48. Mondini M, Vidali M, Airo P, De Andrea M, Riboldi P, Meroni PL, et al. Role of the interferon-inducible gene IFI16 in the etiopathogenesis of systemic autoimmune disorders. Ann N Y Acad Sci. (2007) 1110:47–56. doi: 10.1196/annals.1423.006

49. Seelig HP, Ehrfeld H, Renz M. Interferon-gamma-inducible protein p16. A new target of antinuclear antibodies in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. (1994) 37:1672–83. doi: 10.1002/art.1780371117

50. Costa S, Borgogna C, Mondini M, De Andrea M, Meroni PL, Berti E, et al. Redistribution of the nuclear protein IFI16 into the cytoplasm of ultraviolet B-exposed keratinocytes as a mechanism of autoantigen processing. Br J Dermatol. (2011) 164:282–90. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2010.10097.x

51. Golan TD, Elkon KB, Gharavi AE, Krueger JG. Enhanced membrane binding of autoantibodies to cultured keratinocytes of systemic lupus erythematosus patients after ultraviolet B/ultraviolet A irradiation. J Clin Invest. (1992) 90:1067–76. doi: 10.1172/JCI115922

52. Caricchio R, Mcphie L, Cohen PL. Ultraviolet B radiation-induced cell death: critical role of ultraviolet dose in inflammation and lupus autoantigen redistribution. J Immunol. (2003) 171:5778–86. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.11.5778

53. Shi ZR, Cao CX, Tan GZ, Wang L. The association of serum anti-ribosomal P antibody with clinical and serological disorders in systemic lupus erythematosus: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lupus (2015) 24:588–96. doi: 10.1177/0961203314560003

54. Gerli R, Caponi L, Tincani A, Scorza R, Sabbadini MG, Danieli MG, et al. Clinical and serological associations of ribosomal P autoantibodies in systemic lupus erythematosus: prospective evaluation in a large cohort of Italian patients. Rheumatology (Oxford) (2002) 41:1357–66. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/41.12.1357

55. Fredi M, Cavazzana I, Quinzanini M, Taraborelli M, Cartella S, Tincani A, et al. Rare autoantibodies to cellular antigens in systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus (2014) 23:672–7. doi: 10.1177/0961203314524850

56. Herrmann M, Voll RE, Zoller OM, Hagenhofer M, Ponner BB, Kalden JR. Impaired phagocytosis of apoptotic cell material by monocyte-derived macrophages from patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. (1998) 41:1241–50. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(199807)41:7<1241::AID-ART15>3.0.CO;2-H

57. Ren Y, Tang J, Mok MY, Chan AW, Wu A, Lau CS. Increased apoptotic neutrophils and macrophages and impaired macrophage phagocytic clearance of apoptotic neutrophils in systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. (2003) 48:2888–97. doi: 10.1002/art.11237

58. Bijl M, Reefman E, Horst G, Limburg PC, Kallenberg CG. Reduced uptake of apoptotic cells by macrophages in systemic lupus erythematosus: correlates with decreased serum levels of complement. Ann Rheum Dis. (2006) 65:57–63. doi: 10.1136/ard.2005.035733

59. Schaper F, De Leeuw K, Horst G, Bootsma H, Limburg PC, Heeringa P, et al. High mobility group box 1 skews macrophage polarization and negatively influences phagocytosis of apoptotic cells. Rheumatology (Oxford) (2016) 55:2260–70. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kew324

60. Walport MJ. Complement and systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Res. (2002) 4(Suppl. 3):S279–93. doi: 10.1186/ar586

61. Lipsker D, Hauptmann G. Cutaneous manifestations of complement deficiencies. Lupus (2010) 19:1096–106. doi: 10.1177/0961203310373370

62. Sturfelt G, Truedsson L, Johansen P, Jonsson H, Nived O, Sjoholm AG. Homozygous C4A deficiency in systemic lupus erythematosus: analysis of patients from a defined population. Clin Genet. (1990) 38:427–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.1990.tb03608.x

63. Koide M, Shirahama S, Tokura Y, Takigawa M, Hayakawa M, Furukawa F. Lupus erythematosus associated with C1 inhibitor deficiency. J Dermatol. (2002) 29:503–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1346-8138.2002.tb00316.x

64. Namjou B, Gray-Mcguire C, Sestak AL, Gilkeson GS, Jacob CO, Merrill JT, et al. Evaluation of C1q genomic region in minority racial groups of lupus. Genes Immun. (2009) 10:517–24. doi: 10.1038/gene.2009.33

65. Cai Y, Teo BH, Yeo JG, Lu J. C1q protein binds to the apoptotic nucleolus and causes C1 protease degradation of nucleolar proteins. J Biol Chem. (2015) 290:22570–80. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.670661

66. Cai Y, Wee SYK, Chen J, Teo BHD, Ng YLC, Leong KP, et al. Broad susceptibility of nucleolar proteins and autoantigens to complement C1 protease degradation. J Immunol. (2017) 199:3981–90. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1700728

67. Benoit ME, Clarke EV, Morgado P, Fraser DA, Tenner AJ. Complement protein C1q directs macrophage polarization and limits inflammasome activity during the uptake of apoptotic cells. J Immunol. (2012) 188:5682–93. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1103760

68. Lood C, Gullstrand B, Truedsson L, Olin AI, Alm GV, Ronnblom L, et al. C1q inhibits immune complex-induced interferon-alpha production in plasmacytoid dendritic cells: a novel link between C1q deficiency and systemic lupus erythematosus pathogenesis. Arthritis Rheum. (2009) 60:3081–90. doi: 10.1002/art.24852

69. Santer DM, Hall BE, George TC, Tangsombatvisit S, Liu CL, Arkwright PD, et al. C1q deficiency leads to the defective suppression of IFN-alpha in response to nucleoprotein containing immune complexes. J Immunol. (2010) 185:4738–49. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1001731

70. Chen HH, Tsai LJ, Lee KR, Chen YM, Hung WT, Chen DY. Genetic association of complement component 2 polymorphism with systemic lupus erythematosus. Tissue Antigens (2015) 86:122–33. doi: 10.1111/tan.12602

71. Aragane Y, Kulms D, Luger TA, Schwarz T. Down-regulation of interferon γ-activated STAT1 by UV light. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. (1997) 94:11490–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.21.11490

72. Friedrich M, Holzmann R, Sterry W, Wolk K, Truppel A, Piazena H, et al. Ultraviolet B radiation-mediated inhibition of interferon-gamma-induced keratinocyte activation is independent of interleukin-10 and other soluble mediators but associated with enhanced intracellular suppressors of cytokine-signaling expression. J Invest Dermatol. (2003) 121:845–52. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.2003.12482.x

73. Sauer I, Schaljo B, Vogl C, Gattermeier I, Kolbe T, Müller M, et al. Interferons limit inflammatory responses by induction of tristetraprolin. Blood (2006) 107:4790–7. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-07-3058

74. Walters IB, Ozawa M, Cardinale I, Gilleaudeau P, Trepicchio WL, Bliss J, et al. Narrowband (312-nm) uv-b suppresses interferon γ and interleukin (il) 12 and increases il-4 transcripts: differential regulation of cytokines at the single-cell level. Arch Dermatol. (2003) 139:155–61. doi: 10.1001/archderm.139.2.155

75. Racz E, Prens EP, Kurek D, Kant M, De Ridder D, Mourits S, et al. Effective treatment of psoriasis with narrow-band UVB phototherapy is linked to suppression of the IFN and Th17 pathways. J Invest Dermatol. (2011) 131:1547–58. doi: 10.1038/jid.2011.53

76. Bengtsson AA, Sturfelt G, Truedsson L, Blomberg J, Alm G, Vallin H, et al. Activation of type I interferon system in systemic lupus erythematosus correlates with disease activity but not with antiretroviral antibodies. Lupus (2000) 9:664–71. doi: 10.1191/096120300674499064

77. Braunstein I, Klein R, Okawa J, Werth VP. The interferon-regulated gene signature is elevated in subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus and discoid lupus erythematosus and correlates with the cutaneous lupus area and severity index score. Br J Dermatol. (2012) 166:971–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2012.10825.x

78. Furie R, Khamashta M, Merrill JT, Werth VP, Kalunian K, Brohawn P, et al. Anifrolumab, an anti-interferon-alpha receptor monoclonal antibody, in moderate-to-severe systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheumatol. (2017) 69:376–86. doi: 10.1002/art.39962

79. Der E, Ranabothu S, Suryawanshi H, Akat KM, Clancy R, Morozov P, et al. Single cell RNA sequencing to dissect the molecular heterogeneity in lupus nephritis. JCI Insight (2017) 2:e93009. doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.93009

80. Zahn S, Graef M, Patsinakidis N, Landmann A, Surber C, Wenzel J, et al. Ultraviolet light protection by a sunscreen prevents interferon-driven skin inflammation in cutaneous lupus erythematosus. Exp Dermatol. (2014) 23:516–8. doi: 10.1111/exd.12428

81. Stannard JN, Reed TJ, Myers E, Lowe L, Sarkar MK, Xing X, et al. Lupus skin is primed for IL-6 inflammatory responses through a keratinocyte-mediated autocrine type I interferon loop. J Invest Dermatol. (2017) 137:115–22. doi: 10.1016/j.jid.2016.09.008

82. Meller S, Winterberg F, Gilliet M, Muller A, Lauceviciute I, Rieker J, et al. Ultraviolet radiation-induced injury, chemokines, and leukocyte recruitment: an amplification cycle triggering cutaneous lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. (2005) 52:1504–16. doi: 10.1002/art.21034

83. Norris DA, Lyons MB, Middleton MH, Yohn JJ, Kashihara-Sawami M. Ultraviolet radiation can either suppress or induce expression of intercellular adhesion molecule 1 (ICAM-1) on the surface of cultured human keratinocytes. J Invest Dermatol. (1990) 95:132–8. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12477877

84. Stephansson E, Ros AM. Expression of intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1) and OKM5 in UVA- and UVB-induced lesions in patients with lupus erythematosus and polymorphous light eruption. Arch Dermatol Res. (1993) 285:328–33. doi: 10.1007/BF00371832

85. Nyberg F, Hasan T, Skoglund C, Stephansson E. Early events in ultraviolet light-induced skin lesions in lupus erythematosus: expression patterns of adhesion molecules ICAM-1, VCAM-1 and E-selectin. Acta Derm Venereol. (1999) 79:431–6. doi: 10.1080/000155599750009852

86. Reefman E, Kuiper H, Limburg PC, Kallenberg CG, Bijl M. Type I interferons are involved in the development of ultraviolet B-induced inflammatory skin lesions in systemic lupus erythaematosus patients. Ann Rheum Dis. (2008) 67:11–8. doi: 10.1136/ard.2007.070359

87. Ahn J, Barber GN. Self-DNA, STING-dependent signaling and the origins of autoinflammatory disease. Curr Opin Immunol. (2014) 31:121–6. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2014.10.009

88. Kemp MG, Lindsey-Boltz LA, Sancar A. UV light potentiates STING (Stimulator of Interferon Genes)-dependent innate immune signaling through deregulation of ULK1 (Unc51-like Kinase 1). J Biol Chem. (2015) 290:12184–94. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.649301

89. Fabre VC, Lear S, Reichlin M, Hodge SJ, Callen JP. Twenty percent of biopsy specimens from sun-exposed skin of normal young adults demonstrate positive immunofluorescence. Arch Dermatol. (1991) 127:1006–11. doi: 10.1001/archderm.1991.01680060080008

90. Reich A, Marcinow K, Bialynicki-Birula R. The lupus band test in systemic lupus erythematosus patients. Ther Clin Risk Manage. (2011) 7:27–32. doi: 10.2147/TCRM.S10145

91. Koopman K, Romeijn TR, De Leeuw K, Jonkman MF, Pas HH, Diercks GFH. Nuclear proteins and apoptotic bodies are found in the lupus band of patients with cutaneous lupus erythematosus. J Invest Dermatol. (2017) 137:2652–4. doi: 10.1016/j.jid.2017.08.006

92. Zecevic RD, Pavlovic MD, Stefanovic D. Lupus band test and disease activity in systemic lupus erythematosus: does it still matter? Clin Exp Dermatol. (2006) 31:358–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.2006.02113.x

93. Lovgren T, Eloranta ML, Kastner B, Wahren-Herlenius M, Alm GV, Ronnblom L. Induction of interferon-alpha by immune complexes or liposomes containing systemic lupus erythematosus autoantigen- and Sjogren's syndrome autoantigen-associated RNA. Arthritis Rheum. (2006) 54:1917–27. doi: 10.1002/art.21893

94. Hagberg N, Berggren O, Leonard D, Weber G, Bryceson YT, Alm GV, et al. IFN-alpha production by plasmacytoid dendritic cells stimulated with RNA-containing immune complexes is promoted by NK cells via MIP-1beta and LFA-1. J Immunol. (2011) 186:5085–94. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1003349

95. Berggren O, Hagberg N, Weber G, Alm GV, Ronnblom L, Eloranta ML. B lymphocytes enhance interferon-alpha production by plasmacytoid dendritic cells. Arthritis Rheum. (2012) 64:3409–19. doi: 10.1002/art.34599

96. Leonard D, Eloranta ML, Hagberg N, Berggren O, Tandre K, Alm G, et al. Activated T cells enhance interferon-alpha production by plasmacytoid dendritic cells stimulated with RNA-containing immune complexes. Ann Rheum Dis. (2016) 75:1728–34. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2015-208055

97. Shin MS, Kang Y, Lee N, Kim SH, Kang KS, Lazova R, et al. U1-small nuclear ribonucleoprotein activates the NLRP3 inflammasome in human monocytes. J Immunol. (2012) 188:4769–75. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1103355

98. Shin MS, Kang Y, Lee N, Wahl ER, Kim SH, Kang KS, et al. Self double-stranded (ds)DNA induces IL-1β production from human monocytes by activating NLRP3 inflammasome in the presence of anti–dsDNA antibodies. J Immunol. (2013) 190:1407–15. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1201195

99. Berggren O, Hagberg N, Alexsson A, Weber G, Ronnblom L, Eloranta ML. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells and RNA-containing immune complexes drive expansion of peripheral B cell subsets with an SLE-like phenotype. PLoS ONE (2017) 12:e0183946. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0183946

100. Umare V, Pradhan V, Nadkar M, Rajadhyaksha A, Patwardhan M, Ghosh KK, et al. Effect of proinflammatory cytokines (IL-6, TNF-alpha, and IL-1beta) on clinical manifestations in Indian SLE patients. Mediators Inflamm. (2014) 2014:385297. doi: 10.1155/2014/385297

101. Avalos-Diaz E, Alvarado-Flores E, Herrera-Esparza R. UV-A irradiation induces transcription of IL-6 and TNF alpha genes in human keratinocytes and dermal fibroblasts. Rev Rhum Engl Ed. (1999) 66:13–9.

102. Bashir MM, Sharma MR, Werth VP. UVB and pro-inflammatory cytokines synergistically activate TNF-α production in keratinocytes through enhanced gene transcription. J Invest Dermatol. (2009) 129:994–1001. doi: 10.1038/jid.2008.332

103. Liu Q, Xiao S, Xia Y. TWEAK/Fn14 activation participates in skin inflammation. Mediators Inflamm. (2017) 2017:6746870. doi: 10.1155/2017/6746870

104. Liu Y, Xu M, Min X, Wu K, Zhang T, Li K, et al. TWEAK/Fn14 activation participates in Ro52-mediated photosensitization in cutaneous lupus erythematosus. Front Immunol. (2017) 8:651. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2017.00651

105. Aubin F. Mechanisms involved in ultraviolet light-induced immunosuppression. Eur J Dermatol. (2003) 13:515–23.

106. Schornagel IJ, Sigurdsson V, Nijhuis EH, Bruijnzeel-Koomen CA, Knol EF. Decreased neutrophil skin infiltration after UVB exposure in patients with polymorphous light eruption. J Invest Dermatol. (2004) 123:202–6. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-202X.2004.22734.x

107. Campbell EL, Bruyninckx WJ, Kelly CJ, Glover LE, Mcnamee EN, Bowers BE, et al. Transmigrating neutrophils shape the mucosal microenvironment through localized oxygen depletion to influence resolution of inflammation. Immunity (2014) 40:66–77. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.11.020

108. Villanueva E, Yalavarthi S, Berthier CC, Hodgin JB, Khandpur R, Lin AM, et al. Netting neutrophils induce endothelial damage, infiltrate tissues, and expose immunostimulatory molecules in systemic lupus erythematosus. J Immunol. (2011) 187:538–52. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1100450

109. Lood C, Blanco LP, Purmalek MM, Carmona-Rivera C, De Ravin SS, Smith CK, et al. Neutrophil extracellular traps enriched in oxidized mitochondrial DNA are interferogenic and contribute to lupus-like disease. Nat Med. (2016) 22:146–53. doi: 10.1038/nm.4027

110. Bengtsson AA, Pettersson A, Wichert S, Gullstrand B, Hansson M, Hellmark T, et al. Low production of reactive oxygen species in granulocytes is associated with organ damage in systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Res Ther. (2014) 16:R120. doi: 10.1186/ar4575

111. Olsson LM, Johansson ÅC, Gullstrand B, Jönsen A, Saevarsdottir S, Rönnblom L, et al. A single nucleotide polymorphism in the < NCF1 gene leading to reduced oxidative burst is associated with systemic lupus erythematosus. Ann Rheum Dis. (2017) 76:1607–13. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2017-211287

112. Farkas L, Beiske K, Lund-Johansen F, Brandtzaeg P, Jahnsen FL. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells (natural interferon- alpha/beta-producing cells) accumulate in cutaneous lupus erythematosus lesions. Am J Pathol. (2001) 159:237–43. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)61689-6

113. Barrat FJ, Meeker T, Gregorio J, Chan JH, Uematsu S, Akira S, et al. Nucleic acids of mammalian origin can act as endogenous ligands for Toll-like receptors and may promote systemic lupus erythematosus. J Exp Med. (2005) 202:1131–9. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050914

114. Means TK, Latz E, Hayashi F, Murali MR, Golenbock DT, Luster AD. Human lupus autoantibody-DNA complexes activate DCs through cooperation of CD32 and TLR9. J Clin Invest. (2005) 115:407–17. doi: 10.1172/JCI23025

115. Lande R, Gregorio J, Facchinetti V, Chatterjee B, Wang YH, Homey B, et al. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells sense self-DNA coupled with antimicrobial peptide. Nature (2007) 449:564–9. doi: 10.1038/nature06116

116. Mattoli S, Ackerman V, Vittori E, Marini M. Mast cell chemotactic activity of RANTES. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. (1995) 209:316–21. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1995.1505

117. Juremalm M, Olsson N, Nilsson G. Selective CCL5/RANTES-induced mast cell migration through interactions with chemokine receptors CCR1 and CCR4. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. (2002) 297:480–5. doi: 10.1016/S0006-291X(02)02244-1

118. Jackson NE, Wang HW, Tedla N, Mcneil HP, Geczy CL, Collins A, et al. IL-15 induces mast cell migration via a pertussis toxin-sensitive receptor. Eur J Immunol. (2005) 35:2376–85. doi: 10.1002/eji.200526154

119. Kimata M, Ishizaki M, Tanaka H, Nagai H, Inagaki N. Production of matrix metalloproteinases in human cultured mast cells: involvement of protein kinase C-mitogen activated protein kinase kinase-extracellular signal-regulated kinase pathway. Allergol Int. (2006) 55:67–76. doi: 10.2332/allergolint.55.67

120. Parks WC, Wilson CL, Lopez-Boado YS. Matrix metalloproteinases as modulators of inflammation and innate immunity. Nat Rev Immunol. (2004) 4:617–29. doi: 10.1038/nri1418

121. Zucker S, Mian N, Drews M, Conner C, Davidson A, Miller F, et al. Increased serum stromelysin-1 levels in systemic lupus erythematosus: lack of correlation with disease activity. J Rheumatol. (1999) 26:78–80.

122. Faber-Elmann A, Sthoeger Z, Tcherniack A, Dayan M, Mozes E. Activity of matrix metalloproteinase-9 is elevated in sera of patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Clin Exp Immunol. (2002) 127:393–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.2002.01758.x

123. Mawrin C, Brunn A, Rocken C, Schroder JM. Peripheral neuropathy in systemic lupus erythematosus: pathomorphological features and distribution pattern of matrix metalloproteinases. Acta Neuropathol. (2003) 105:365–72. doi: 10.1007/s00401-002-0653-2

124. Mandel M, Gurevich M, Pauzner R, Kaminski N, Achiron A. Autoimmunity gene expression portrait: specific signature that intersects or differentiates between multiple sclerosis and systemic lupus erythematosus. Clin Exp Immunol. (2004) 138:164–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2004.02587.x

125. Salmela MT, Karjalainen-Lindsberg ML, Jeskanen L, Saarialho-Kere U. Overexpression of tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases-3 in intestinal and cutaneous lesions of graft-versus-host disease. Mod Pathol. (2003) 16:108–14. doi: 10.1097/01.MP.0000051681.43441.82

126. Jarvinen TM, Kanninen P, Jeskanen L, Koskenmies S, Panelius J, Hasan T, et al. Matrix metalloproteinases as mediators of tissue injury in different forms of cutaneous lupus erythematosus. Br J Dermatol. (2007) 157:970–80. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2007.08166.x

127. Van Nguyen H, Di Girolamo N, Jackson N, Hampartzoumian T, Bullpitt P, Tedla N, et al. Ultraviolet radiation-induced cytokines promote mast cell accumulation and matrix metalloproteinase production: potential role in cutaneous lupus erythematosus. Scand J Rheumatol. (2011) 40:197–204. doi: 10.3109/03009742.2010.528020

128. Macleod AS, Rudolph R, Corriden R, Ye I, Garijo O, Havran WL. Skin-resident T cells sense ultraviolet radiation-induced injury and contribute to DNA repair. J Immunol. (2014) 192:5695–702. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1303297

129. Bruhs A, Schwarz T. Ultraviolet radiation-induced immunosuppression: induction of regulatory T cells. Methods Mol Biol. (2017) 1559:63–73. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-6786-5_5

130. Phan TX, Jaruga B, Pingle SC, Bandyopadhyay BC, Ahern GP. Intrinsic photosensitivity enhances motility of T lymphocytes. Sci Rep. (2016) 6:39479. doi: 10.1038/srep39479

131. Peter Kind PL, Plewig G. Phototesting in lupus erythematosus. J Invest Dermatol. (1993) 100:S53–7. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12355594

132. Sole C, Gimenez-Barcons M, Ferrer B, Ordi-Ros J, Cortes-Hernandez J. Microarray study reveals a TGFbeta-dependent mechanism of fibrosis in discoid lupus erythematosus. Br J Dermatol. (2016). 175:302–13. doi: 10.1111/bjd.14539

133. Nikkola V, Gronroos M, Huotari-Orava R, Kautiainen H, Ylianttila L, Karppinen T, et al. Circadian time effects on NB-UVB-induced erythema in human skin in vivo. J Invest Dermatol. (2018) 138:464–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jid.2017.08.016

134. Huber AL, Papp SJ, Chan AB, Henriksson E, Jordan SD, Kriebs A, et al. CRY2 and FBXL3 cooperatively degrade c-MYC. Mol Cell (2016) 64:774–89. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2016.10.012

135. Cao Q, Zhao X, Bai J, Gery S, Sun H, Lin DC, et al. Circadian clock cryptochrome proteins regulate autoimmunity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. (2017) 114:12548–53. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1619119114

136. Leone J, Pennaforte JL, Delhinger V, Detour J, Lefondre K, Eschard JP, et al. [Influence of seasons on risk of flare-up of systemic lupus: retrospective study of 66 patients]. Rev Med Interne (1997) 18:286–91. doi: 10.1016/S0248-8663(97)84013-1

137. Mcgrath HJr, Bak E, Michalski JP. Ultraviolet-A light prolongs survival and improves immune function in (New Zealand black x New Zealand white)F1 hybrid mice. Arthritis Rheum. (1987) 30:557–61. doi: 10.1002/art.1780300510

138. Okamoto H, Mizuno K, Itoh T, Tanaka K, Horio T. Evaluation of apoptotic cells induced by ultraviolet light B radiation in epidermal sheets stained by the TUNEL technique. J Invest Dermatol. (1999) 113:802–7. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.1999.00757.x

139. Foltyn VN, Golan TD. In vitro ultraviolet irradiation induces pro-inflammatory responses in cells from premorbid SLE mice. Lupus (2001) 10:272–83. doi: 10.1191/096120301680416968

140. Choubey D, Kotzin BL. Interferon-inducible p202 in the susceptibility to systemic lupus. Front Biosci. (2002) 7:e252–62. doi: 10.2741/A921

141. Theofilopoulos AN, Baccala R, Beutler B, Kono DH. Type I interferons (alpha/beta) in immunity and autoimmunity. Annu Rev Immunol. (2005) 23:307–36. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.23.021704.115843

142. Harberts E, Fishelevich R, Liu J, Atamas SP, Gaspari AA. MyD88 mediates the decision to die by apoptosis or necroptosis after UV irradiation. Innate Immun. (2014) 20:529–39. doi: 10.1177/1753425913501706

143. Doerner J, Chalmers SA, Friedman A, Putterman C. Fn14 deficiency protects lupus-prone mice from histological lupus erythematosus-like skin inflammation induced by ultraviolet light. Exp Dermatol. (2016) 25:969–76. doi: 10.1111/exd.13108

144. Doerner JL, Wen J, Xia Y, Paz KB, Schairer D, Wu L, et al. TWEAK/Fn14 signaling involvement in the pathogenesis of cutaneous disease in the MRL/lpr model of spontaneous lupus. J Invest Dermatol. (2015) 135:1986–95. doi: 10.1038/jid.2015.124

145. Golan DT, Borel Y. Increased photosensitivity to near-ultraviolet light in murine SLE. J Immunol. (1984) 132:705–10.

146. Scholtissek B, Zahn S, Maier J, Klaeschen S, Braegelmann C, Hoelzel M, et al. Immunostimulatory endogenous nucleic acids drive the lesional inflammation in cutaneous lupus erythematosus. J Invest Dermatol. (2017) 137:1484–92. doi: 10.1016/j.jid.2017.03.018

147. Lee YF, Cheng CC, Lan JL, Hsieh TY, Lin NN, Lin HY, et al. Effects of mycophenolate mofetil on cutaneous lupus erythematosus in (NZB x NZW) F1 mice. J Chin Med Assoc. (2013) 76:615–23. doi: 10.1016/j.jcma.2013.07.010

148. Herrera-Esparza R, Villalobos R, Bollain YGJJ, Ramirez-Sandoval R, Sanchez-Rodriguez SH, Pacheco-Tovar G, et al. Apoptosis and redistribution of the Ro autoantigen in Balb/c mouse like in subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus. Clin Dev Immunol. (2006) 13:163–6. doi: 10.1080/17402520600876796

149. Lu KQ, Brenneman S, Burns RJr, Vink A, Gaines E, Haake A, et al. Thalidomide inhibits UVB-induced mouse keratinocyte apoptosis by both TNF-alpha-dependent and TNF-alpha-independent pathways. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. (2003) 19:272–80. doi: 10.1046/j.1600-0781.2003.00055.x

150. Paz ML, Ferrari A, Weill FS, Leoni J, Maglio DH. Time-course evaluation and treatment of skin inflammatory immune response after ultraviolet B irradiation. Cytokine (2008) 44:70–7. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2008.06.012

151. Xin H, D'souza S, Jorgensen TN, Vaughan AT, Lengyel P, Kotzin BL, et al. (2006). Increased expression of Ifi202, an IFN-activatable gene, in B6.Nba2 lupus susceptible mice inhibits p53-mediated apoptosis. J Immunol. 176, 5863–70. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.10.5863

152. Sontheimer C, Liggitt D, Elkon KB. Ultraviolet B irradiation causes stimulator of interferon genes-dependent production of protective type i interferon in mouse skin by recruited inflammatory monocytes. Arthritis Rheumatol. (2017) 69:826–36. doi: 10.1002/art.39987

153. Menke J, Hsu MY, Byrne KT, Lucas JA, Rabacal WA, Croker BP, et al. Sunlight triggers cutaneous lupus through a CSF-1-dependent mechanism in MRL-Fas(lpr) mice. J Immunol. (2008) 181:7367–79. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.10.7367

154. Schwarz A, Bhardwaj R, Aragane Y, Mahnke K, Riemann H, Metze D, et al. Ultraviolet-B-induced apoptosis of keratinocytes: evidence for partial involvement of tumor necrosis factor-alpha in the formation of sunburn cells. J Invest Dermatol. (1995) 104:922–7. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12606202

155. Zhuang L, Wang B, Shinder GA, Shivji GM, Mak TW, Sauder DN. TNF receptor p55 plays a pivotal role in murine keratinocyte apoptosis induced by ultraviolet B irradiation. J Immunol. (1999) 162:1440–7.

156. Groves RW, Mizutani H, Kieffer JD, Kupper TS. Inflammatory skin disease in transgenic mice that express high levels of interleukin 1 alpha in basal epidermis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. (1995) 92:11874–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.25.11874

157. Nishimura N, Tohyama C, Satoh M, Nishimura H, Reeve VE. Defective immune response and severe skin damage following UVB irradiation in interleukin-6-deficient mice. Immunology (1999) 97:77–83. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.1999.00733.x

158. Majewski S, Jantschitsch C, Maeda A, Schwarz T, Schwarz A. IL-23 antagonizes UVR-induced immunosuppression through two mechanisms: reduction of UVR-induced DNA damage and inhibition of UVR-induced regulatory T cells. J Invest Dermatol. (2010) 130:554–62. doi: 10.1038/jid.2009.274

159. Kyttaris VC, Kampagianni O, Tsokos GC. Treatment with anti-interleukin 23 antibody ameliorates disease in lupus-prone mice. Biomed Res Int. (2013) 2013:861028. doi: 10.1155/2013/861028

160. Hatakeyama M, Fukunaga A, Washio K, Taguchi K, Oda Y, Ogura K, et al. Anti-inflammatory role of langerhans cells and apoptotic keratinocytes in ultraviolet-B-induced cutaneous inflammation. J Immunol. (2017) 199:2937–47. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1601681

161. Cela EM, Friedrich A, Paz ML, Vanzulli SI, Leoni J, Gonzalez Maglio DH. Time-course study of different innate immune mediators produced by UV-irradiated skin: comparative effects of short and daily versus a single harmful UV exposure. Immunology (2015) 145:82–93. doi: 10.1111/imm.12427

162. Yin Q, Xu X, Lin Y, Lv J, Zhao L, He R. Ultraviolet B irradiation induces skin accumulation of plasmacytoid dendritic cells: a possible role for chemerin. Autoimmunity (2014) 47:185–92. doi: 10.3109/08916934.2013.866105

163. Schwarz A, Maeda A, Wild MK, Kernebeck K, Gross N, Aragane Y, et al. Ultraviolet radiation-induced regulatory T cells not only inhibit the induction but can suppress the effector phase of contact hypersensitivity. J Immunol. (2004) 172:1036–43. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.2.1036

164. Shipman WD, Chyou S, Ramanathan A, Izmirly PM, Sharma S, Pannellini T, et al. A protective Langerhans cell-keratinocyte axis that is dysfunctional in photosensitivity. Sci Transl Med. (2018) 10:eaap9527. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aap9527

165. Ghoreishi M, Dutz JP. Murine models of cutaneous involvement in lupus erythematosus. Autoimmun Rev. (2009) 8:484–7. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2009.02.028

166. Ansel JC, Mountz J, Steinberg AD, Defabo E, Green I. Effects of UV radiation on autoimmune strains of mice: increased mortality and accelerated autoimmunity in BXSB male mice. J Invest Dermatol. (1985) 85:181–6. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12276652

167. Sano S, Kataoka S, Kamijima R, Fujimoto C, Ohko K, Takaishi M, et al. Ultraviolet B irradiation accelerates the development of lupus-like autoimmunity in wild-type mice induced by topical treatment with TLR7 agonist (BA4P.212). J Immunol. (2014) 192:46.43.

168. Wolf SJ, Theros J, Reed TJ, Liu J, Grigorova IL, Martinez-Colon G, et al. TLR7-Mediated Lupus Nephritis Is Independent of Type I IFN Signaling. J Immunol. (2018) 201:393–405. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1701588

169. Clark KL, Reed TJ, Wolf SJ, Lowe L, Hodgin JB, Kahlenberg JM. Epidermal injury promotes nephritis flare in lupus-prone mice. J Autoimmun. (2015) 65:38–48. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2015.08.005

170. Mevorach D, Zhou JL, Song X, Elkon KB. Systemic exposure to irradiated apoptotic cells induces autoantibody production. J Exp Med. (1998) 188:387–92. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.2.387

Keywords: ultraviolet light, lupus (SLE), photosensitivity, cytokines, apoptosis

Citation: Wolf SJ, Estadt SN, Gudjonsson JE and Kahlenberg JM (2018) Human and Murine Evidence for Mechanisms Driving Autoimmune Photosensitivity. Front. Immunol. 9:2430. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.02430

Received: 23 July 2018; Accepted: 02 October 2018;

Published: 23 October 2018.

Edited by:

Anne Davidson, Feinstein Institute for Medical Research, United StatesReviewed by:

Christian Jan Lood, University of Washington, United StatesUmesh S. Deshmukh, Oklahoma Medical Research Foundation, United States

Nicholas Arthur Soter, New York University, United States

Copyright © 2018 Wolf, Estadt, Gudjonsson and Kahlenberg. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: J. Michelle Kahlenberg, bWthaGxlbmJAdW1pY2guZWR1

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Sonya J. Wolf

Sonya J. Wolf Shannon N. Estadt

Shannon N. Estadt Johann E. Gudjonsson

Johann E. Gudjonsson J. Michelle Kahlenberg

J. Michelle Kahlenberg