94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Genet. , 16 September 2020

Sec. Computational Genomics

Volume 11 - 2020 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fgene.2020.577387

This article is part of the Research Topic Graph Embedding Methods for Multiple-Omics Data Analysis View all 20 articles

A new coronavirus called SARS-CoV-2 is rapidly spreading around the world. Over 16,558,289 infected cases with 656,093 deaths have been reported by July 29th, 2020, and it is urgent to identify effective antiviral treatment. In this study, potential antiviral drugs against SARS-CoV-2 were identified by drug repositioning through Virus-Drug Association (VDA) prediction. 96 VDAs between 11 types of viruses similar to SARS-CoV-2 and 78 small molecular drugs were extracted and a novel VDA identification model (VDA-RLSBN) was developed to find potential VDAs related to SARS-CoV-2. The model integrated the complete genome sequences of the viruses, the chemical structures of drugs, a regularized least squared classifier (RLS), a bipartite local model, and the neighbor association information. Compared with five state-of-the-art association prediction methods, VDA-RLSBN obtained the best AUC of 0.9085 and AUPR of 0.6630. Ribavirin was predicted to be the best small molecular drug, with a higher molecular binding energy of −6.39 kcal/mol with human angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2), followed by remdesivir (−7.4 kcal/mol), mycophenolic acid (−5.35 kcal/mol), and chloroquine (−6.29 kcal/mol). Ribavirin, remdesivir, and chloroquine have been under clinical trials or supported by recent works. In addition, for the first time, our results suggested several antiviral drugs, such as FK506, with molecular binding energies of −11.06 and −10.1 kcal/mol with ACE2 and the spike protein, respectively, could be potentially used to prevent SARS-CoV-2 and remains to further validation. Drug repositioning through virus–drug association prediction can effectively find potential antiviral drugs against SARS-CoV-2.

Last December 2019, a novel coronavirus called SARS-CoV-2 by the World Health Organization (WHO), first found in Wuhan, China, was rapidly spreading around the world (Kaiser et al., 2020; Sanche et al., 2020). The SARS-CoV-2 outbreak was declared as a global public health emergency by WHO, and a total of 16,558,289 cases have been confirmed with another 656,093 deaths throughout the world by July 29th, 2020 (World Health Organization [WHO], 2020). SARS-CoV-2 caused a severe acute respiratory syndrome named COVID-19, and no special vaccine or antiviral drug against SARS-CoV-2 has been found at present (Lu, 2020; Wang et al., 2020c). Therefore, finding a special antiviral drug as soon as possible is urgent to stop the spread of SARS-CoV-2 (Lu, 2020; Zhang et al., 2020a).

However, designing a new drug to treat COVID-19 in a short time is almost impossible (Zhang et al., 2020a). One of the best strategies is drug repositioning (Chen et al., 2012, 2016; Peng et al., 2017a; Beck et al., 2020). By repositioning already commercialized drugs, the undesired effects can be inferred to find new uses for these drugs. This strategy can thus greatly shorten the time required for an antiviral drug against SARS-CoV-2.

Although little is known about SARS-CoV-2, its complete genome sequence is strongly homologous to SARS-CoV (Huang et al., 2020; Morse et al., 2020). Therefore, in this study, to prioritize available FDA-approved antiviral drugs against SARS-COV-2 for further clinical trials, 11 well-studied viruses similar to SARS-CoV-2 were selected and 96 virus–drug associations (VDAs) with these 11 viruses were integrated. Regularized least squared classifier (RLS), bipartite local model (BLM), and neighbor association information were applied in our new algorithm named VDA-RLSBN to find novel VDAs for new virus (especially for SARS-CoV-2) or new drug. The results showed that ribavirin, remdesivir, and chloroquine may be antiviral drugs against SARS-CoV-2.

Molecular docking techniques investigate the behavior of small molecular drugs in the binding site of a target protein. As more target protein structures are confirmed experimentally, molecular docking approaches are widely applied to drug design (Zhang et al., 2020b). AutoDock (Goodsell et al., 1996; Ruyck et al., 2016) is an available software applied to identify the bound conformations of a small molecular drug to a macromolecular target. The AutoDock affinity scoring function is applied to rank the candidate poses based on the sum of the van der Waals and electrostatic energies. We conducted molecular docking between the predicted top 10 antiviral drugs against SARS-CoV-2 and two target proteins including the spike protein of SARS-CoV-2 and human angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) molecule (Wang et al., 2020a). The molecular binding energies between the above three drugs and ACE2 are ribavirin with −6.39 kcal/mol, remdesivir with −7.4 kcal/mol, and chloroquine with −6.29 kcal/mol. These three small molecules have been under clinical trial or supported by recent publications. In addition, we found that FK506 shows higher molecular binding energies of −10.1 kcal/mol and −11.06 kcal/mol with these two targets, which suggest that FK506 may be applied to stop COVID-19 although there is no report about its association with SARS-CoV-2.

Aiming at identifying potential VDAs related to SARS-CoV-2, 96 known VDAs between 11 viruses similar to SARS-CoV-2 and 78 small molecular drugs were selected from the DrugBank (Wishart et al., 2018), NCBI (Sayers et al., 2020), and PubMed (Canese and Sarah, 2013) databases. The element in the VDA matrix Yori ∈ ℜn×m was represented as

These similar viruses included SARS-CoV (Ding et al., 2004), MERS-CoV (Groot et al., 2013), human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (Wei et al., 1995) and type 2 (Guyader et al., 1987) (HIV-1 and HIV-2), chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) (Jacobson et al., 2011), influenza A viruses [A-H1N1 (Kumar et al., 2009), A-H5N1 (Subbarao et al., 1998), A-H7N9 (Gao et al., 2013)], Hendra virus (Bonaparte et al., 2005), human cytomegalovirus (Cobbs et al., 2002), and respiratory syncytial virus (Hall, 2001). Complete genome sequences of these 11 viruses and SARS-CoV-2 were downloaded from the NCBI database, and virus similarity matrix Sv ∈ ℜn×n was computed based on MAFFT, a multiple-sequence alignment software. Chemical structures of drugs were downloaded from the DrugBank database, and drug similarity matrix Sd ∈ ℜm×m was obtained by RDKit, an open-source cheminformatics tool. The details are shown in Table 1.

Bleakley and Yamanishi (2009) represented a drug–target interaction network as a bipartite graph and developed a BLM-based method to predict possible drug–target interactions. The proposed method first inferred targets of a given FDA-approved drug and drugs targeting a known protein and then combined these two independent predictions. The results demonstrated the excellent performance of BLM. Similar to the drug–target interaction network, the VDA network can also be taken as a bipartite graph. Results in this study are thus presented to evaluate the prediction performance in each of the following four cases for a given putative virus–drug pair:

• The virus with at least one known drug and the drug with at least one known virus.

• The virus with at least one known drug and the drug without any known virus (new drug).

• The virus without any known drug (new virus) and the drug with at least one known virus.

• New virus and new drug.

Based on these four cases, we represent a VDA network as a bipartite graph and thus the predicted VDA matrix can be denoted as Eq. (2):

where is the number of new viruses (for example, SARS-CoV-2), and is the number of new drugs. Y1 represents VDAs from ncv existing viruses and mcv existing drugs, Y2 represents VDAs from ncv existing viruses and new drugs, Y3 denotes VDAs from new viruses and mcv existing drugs, and Y4 denotes VDAs from new viruses and new drugs. Our aims are to identify potential VDAs in the subnetwork Y1 as well as in Y2, Y3, and Y4. Figure 1 shows the flowchart of VDA-RLSBN.

To infer possible VDA candidates, we develop an RLS-based VDA identification model (VDA-RLS) to compute the association profile for each virus–drug pair:

where K represents the kernel matrix, y denotes the original association profile, and σ is a regularization parameter.

To compute VDA matrix Y1 from ncv existing viruses and mcv existing drugs, we consider the ensemble of independent virus-based prediction and drug-based prediction with RLS. The solution of Y1 can be thus divided down into the following four steps:

Step 1 For a given virus vi with at least one known association, its new association profile can be computed from its original association profile and the kernel matrix Kv based on RLS classifier:

where , and represents the ith row of Yori. We can compute virus-based VDA matrix Yv by Eq. (4).

Step 2 For a given drug dj with at least one known association, its new association profile can be computed from its original association profile and the kernel matrix Kd based on RLS classifier:

where , and represents the jth column of Yori. We can compute drug-based VDA matrix Yd by Eq. (5).

Step 3 Integrate Yv with the element and Yd with the element to compute the predicted VDA matrix YRLS based on RLS:

Step 4 Obtain Y1 by Eq. (7):

We can identify novel VDAs between existing viruses and existing drugs, or known/new viruses and new/existing drugs based on RLS and BLM. However, VDA-RLS was not able to predict associations between new viruses and new drugs. To solve this problem, we developed a VDA prediction model (VDA-RLSBN) by integrating neighbor association information into the RLS model.

Based on the “guilt-by-association” method, similar viruses/drugs tend to associate with similar drugs/viruses, so the association profile of an unknown virus could be possibly found by its neighbors’ association information. Viruses highly similar to a new virus can be considered as its neighbors. Since the new virus has no associated drugs (i.e., its current association profile is a vector with all the elements of 0), complete genome sequence similarity of viruses is applied to define its neighbors.

For a new virus vi, its association weight with a drug dj can be computed by its neighbors’ associations with dj and its association profile is defined as Eq. (8):

where is the complete genome sequence similarity between two viruses vi and vj. when the jth associated drug dj exists, i.e., for at least one k and when the jth associated drug dj is new, i.e., for all k. is normalized to make its value in the range of [0,1] by Eq. (9):

Also, an independent virus-based association profile for a virus–drug pair can be represented as Eq. (10):

Similarly, for a new drug dj, its association profile for the same virus–drug pair can be represented as Eq. (10):

where denotes the neighbor association profile of dj.

The final VDA network can be represented as

where can be computed by Eqs (4–7); can be computed by Eqs (4), (11), and (6); can be obtained by Eqs (10), (5), and (6); and can be obtained by Eqs (10), (11), and (6). Specially, the VDA matrix related to SARS-CoV-2 can be obtained from .

Finally, we used AutoDock to analyze the druggability of the predicted top 10 chemical agents and their binding activities with two target proteins including the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein and ACE2.

In this section, we performed extensive experiments to evaluate our proposed VDA-RLSBN method. We compared VDA-RLSBN with five state-of-the-art machine learning-based models, including LRLSHMDA (Wang et al., 2017), SMiR-NBI (Li et al., 2016), CMF (Zheng et al., 2013), NetLapRLS (Xia et al., 2010), and WNN-GIP (Laarhoven and Marchiori, 2013). The experiments were performed on a MAC with 2.4 GHz Inter Core i5, 8 GB 2133 MHz LPDDR3 of the RAM and OS Catalina 10.15.4 operating system.

Sensitivity, specificity, accuracy, AUC, and AUPR are widely applied to evaluate various machine learning-based models. In this study, we used these five metrics to measure the performance of five state-of-the-art models and VDA-RLSBN. Accuracy denotes the ratio of correctly predicted VDAs to all VDAs. Sensitivity denotes the ratio of correctly predicted positive VDAs to all positive VDAs. Specificity is the ratio of correctly predicted negative VDAs to all negative VDAs. AUC is the area under the ROC curve. The ROC curve can be plotted by a true positive rate [TPR, i.e., Eq. (13)] and a false-positive rate [FPR, i.e., Eq. (14)].

where TPR represents the ratio of correctly predicted positive VDAs to all positive VDAs and FPR represents the ratio of mistakenly predicted positive VDAs to all negative VDAs.

AUPR is the area under the PR curve. The PR curve can be plotted by precision and recall. Precision represents the ratio of correctly predicted positive VDAs to all predicted positive VDAs, and recall represents the ratio of correctly predicted positive VDAs to all positive VDAs.

where TP,FP,TN,andFN represent true positive, false positive, true negative, and false negative, respectively. Generally, larger AUC/AUPR value denotes better performances.

We used five-fold cross validation to train our proposed VDA-RLSBN method. In each round, 80% of VDAs in the known VDA network was used as a training set and the remaining 20% of VDAs was the test set. The experiments were performed 100 times, and the final performance was on average over 100 times. In each round, a virus/drug is new if all of its associated drugs/viruses are selected as a test set.

For the parameters in five comparative methods and VDA-RLSBN, we conducted grid search to determine their optimal values. In VDA-RLSBN, we set the parameter σ in the range of [0, 0.1, 0.2, …, 1] and found that VDA-RLSBN obtained the best performance when σ is set as 0.4. In LRLSHMDA, we set the parameter lw in the range of [0, 0.1, 0.2, …, 1] and found that LRLSHMDA obtained better accuracy when lw is set as 0.1. In CMF, we set the parameters λl,λd,andλt in the range of [2−2,…, 21], [2−3,…, 25], and [2−3,…, 25], respectively. We found that CMF obtained better performance when λl = 1, λd = 0.25, and λt = 0.125. In NetLapRLS, we set four parameters γd, γt, βd, and βt in the range of [1e−6,…, 1e2] and found that NetLapRLS performed better when these four parameters were set as 1e-6. In WNN-GIP, we set five parameters T, αd, αt, σ, and γ in the range of [0, 0.1,…, 1.0] and found that WNN-GIP obtained the optimal performance when T = 0.7, αd = 0.6, αt = 0.6, σ = 1, and γ = 0.5. All parameters in these six models were set as the corresponding values where the corresponding method obtained the optimal performance.

The performance of our proposed VDA-RLSBN and these five machine learning-based models is shown in Table 2. The best performance in each row is shown in bold in Table 2. LRLSHMDA (Wang et al., 2017), NetLapRLS (Xia et al., 2010), WNN-GIP (Laarhoven and Marchiori, 2013), and VDA-RLSBN are RLS-based methods. LRLSHMDA (Wang et al., 2017) used Laplacian RLS to tackle microbe–disease association prediction, NetLapRLS (Xia et al., 2010) extended the standard Laplacian RLS incorporating drug–target network, and WNN-GIP (Laarhoven and Marchiori, 2013) integrated a simple weighted nearest neighbor method and Gaussian kernels into RLS. SMiR-NBI (Li et al., 2016) constructed a heterogeneous network connecting genes, drugs, and miRNAs and then combined a network-based inference algorithm to characterize the responses of anticancer drugs. CMF (Zheng et al., 2013) was a collaborative matrix factorization-based drug–target interaction prediction method.

The results showed that VDA-RLSBN outperformed LRLSHMDA, SMiR-NBI, CMF, and WNN-GIP in terms of five evaluation metrics. Although the specificity value of VDA-RLSBN is slightly lower compared to NetLapRLS, its AUC and AUPR are significantly higher than NetLapRLS. Since AUC and AUPR are more important evaluation metrics compared to other three measurements, VDA-RLSBN, with the highest AUC and AUPR, is considered to be better in finding potential VDAs of novel viruses.

Among six VDA prediction methods, LRLSHMDA, NetLapRLS, WNN-GIP, and VDA-RLSBN are RLS-based methods. VDA-RLSBN obtained better performance than the other three methods. Although other RLS-based prediction methods have good performance, they cannot predict the relationship between new drug candidates and new candidate targets. If a virus/drug has no known drug/virus, it is a new virus/drug. Since there are many new viruses/drugs, our proposed VDA-RLSBN approach learned labeled information from neighbors and used the information to train the model and make predictions. So VDA-RLSBN obtained better performance compared to other RLS-based methods. The results suggest that RLS combining neighbor association information can better identify new VDAs.

The prediction performance of the proposed VDA-RLSBN method was confirmed in the last section. As a means to finding potential antiviral drugs against SARS-CoV-2, small molecular drugs were ranked based on the association scores with SARS-CoV-2 and the top 10 drugs with the highest scores were listed in Table 3. Among the predicted top 10 VDAs, 4 VDAs are reported by related literature, that is, 40% small molecular drugs are confirmed to be possible antiviral drugs against SARS-CoV-2.

Ribavirin is inferred to be the best small molecular drug against SARS-CoV-2. It is a broad-spectrum antiviral drug that can inhibit the replication of respiratory syncytial virus (Laarhoven and Marchiori, 2013). For example, it has been applied to prevent respiratory syncytial virus infection in lung transplant recipients (Hayden and Whitley, 2020) and specially used to treat SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV (Permpalung et al., 2019). Similar to SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV, SARS-CoV-2 is a respiratory syndrome betacoronavirus and may cause serious respiratory diseases. A few studies (Li and De, 2020; Wang et al., 2020b) have reported that ribavirin may take an inhibitory effect on SARS-CoV-2. More importantly, remdesivir and chloroquine are inferred to be other effective antiviral drugs. Wang et al. (2020b) presented that remdesivir and chloroquine can effectively inhibit SARS-CoV-2 and they have been used in the clinical stage. These results suggest that ribavirin, remdesivir, and chloroquine may be applied to the treatment of COVID-19.

We conducted molecular docking between the predicted top 10 small molecules and the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein/ACE2. The chemical structures of these small molecular drugs were downloaded from the DrugBank database. The structure of the virus spike protein was obtained based on homologous modeling from Zhang Lab (2020). The structure of ACE2 can be downloaded from the RCSB Protein Data Bank (Helen et al., 2000) (ID:6MJ0). AutoDock used the genetic algorithm as a search algorithm and selected the entire protein as a grid box.

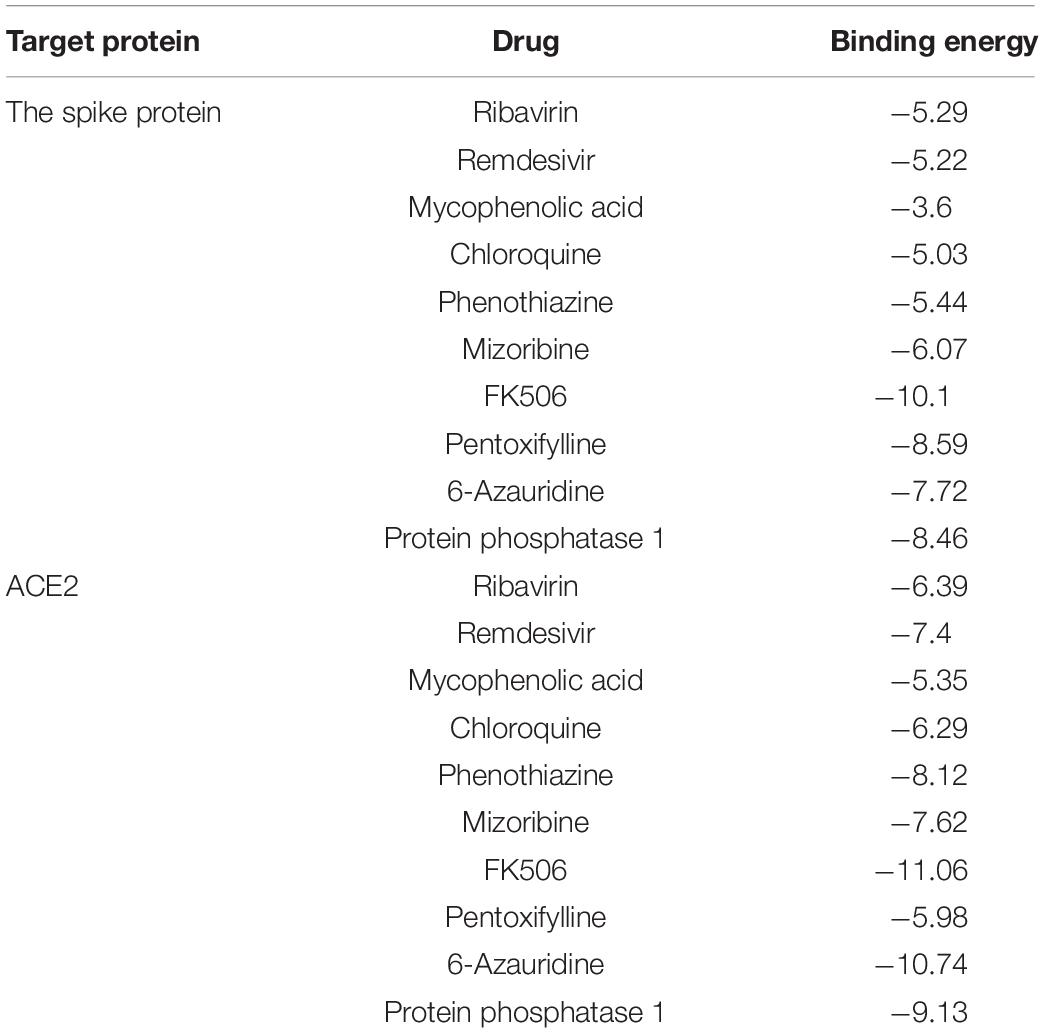

The molecular binding energies between the predicted top 10 small molecules and these two target proteins are described in Table 4. The results show that the predicted top 10 drugs have higher molecular binding activities with the spike protein and/or ACE2. For example, ribavirin, which is predicted to be the most possible drug against SARS-CoV-2, has a higher molecular binding energy of −6.39 kcal/mol with ACE2. In addition, remdesivir, mycophenolic acid, and chloroquine are predicted to have higher association scores with SARS-CoV-2. These three small molecular drugs showed higher binding energies of −7.4, −5.35, and −6.29 kcal/mol with ACE2, respectively. More importantly, ribavirin, remdesivir, and chloroquine have been used for the treatment of SARS, which has about 79% sequence identity with SARS-CoV-2. So the potential use of these three small molecules as a treatment for COVID-19 may be under investigation. Interestingly, FK506 is an immunesuppressive drug and mainly used to decrease the activity of the immune system after organ transplant. The molecular docking results show that FK506 has a strong molecular binding energy of −11.06 and −10.1 kcal/mol with ACE2 and the spike protein, respectively, although it has a slightly lower rank in the predicted drugs against SARS-CoV-2 by VDA-RLSBN.

Table 4. The molecular binding energies between the predicted top 10 antiviral drugs and two target proteins.

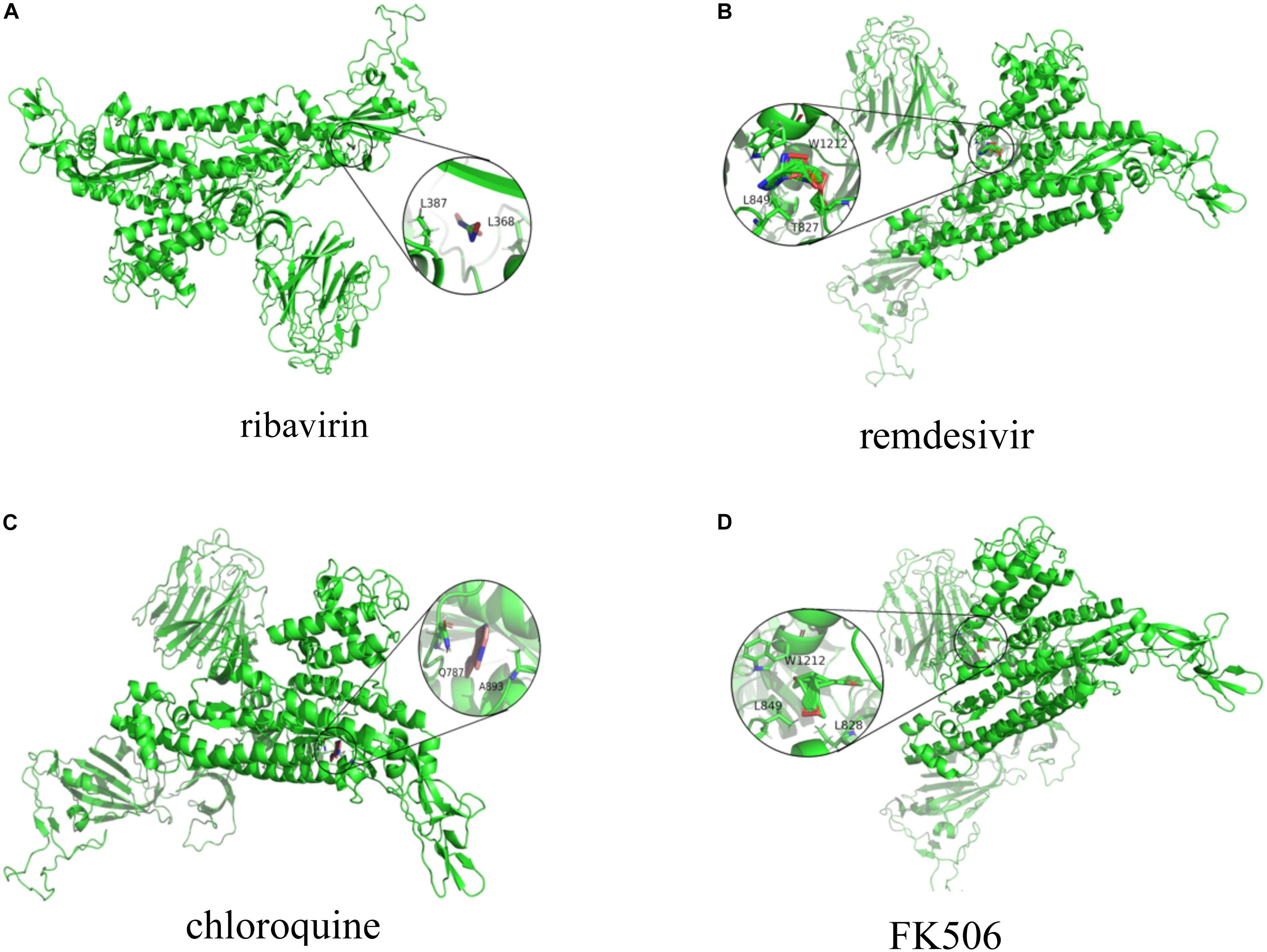

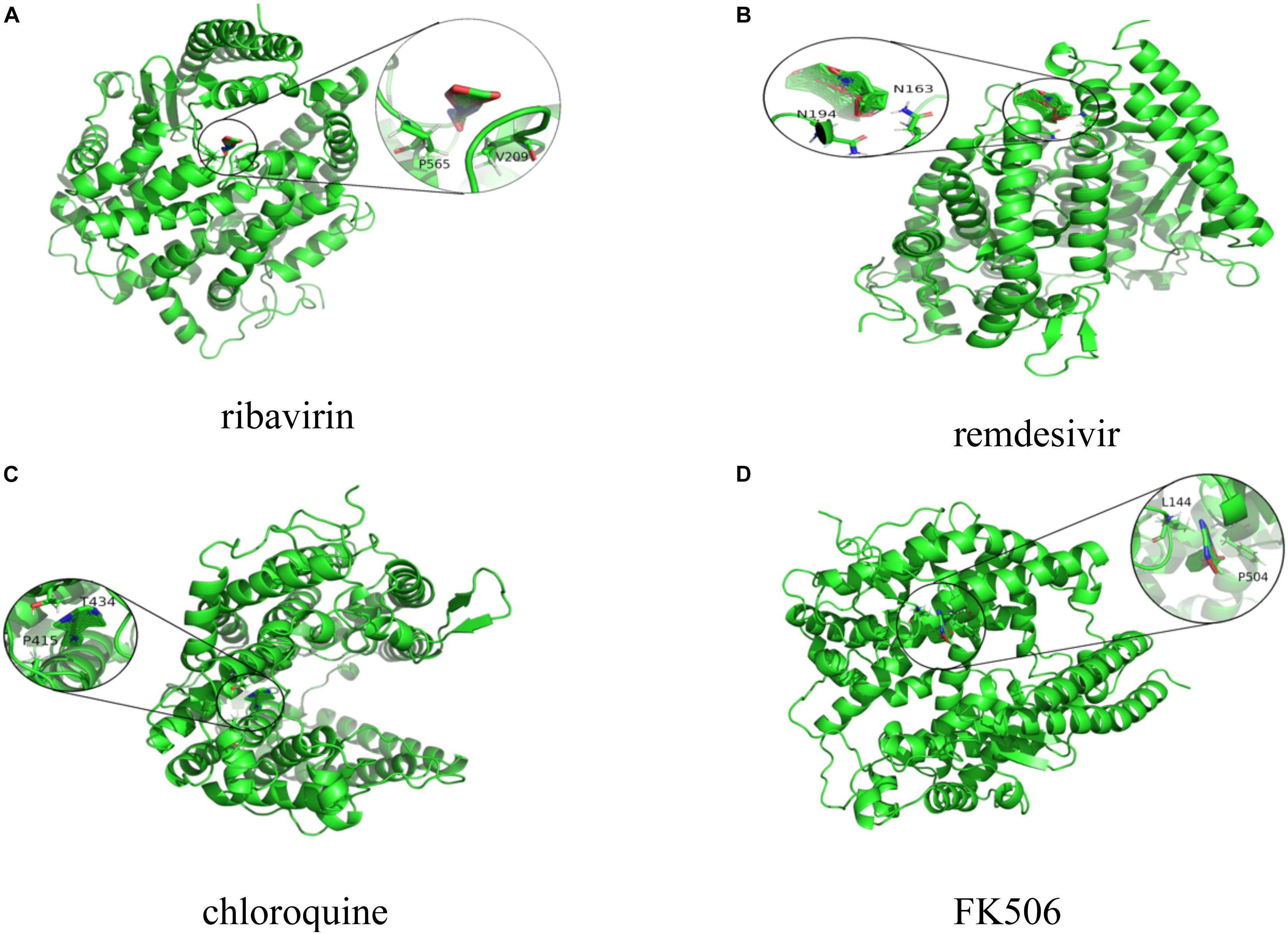

Figures 2, 3 represent the docking results about four small molecules including ribavirin, remdesivir, chloroquine, and FK506 and two target proteins. The subfigure in each circle denotes the residues at the binding site of the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein/ACE2 and their corresponding orientations. For example, the amino acids L387, L368, P565, and V209 were inferred to be the key residues for ribavirin binding to the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein/ACE2 while L828, L849, W1212, N163, and N194 were inferred as the key residues for FK506 binding to the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein/ACE2.

Figure 2. Molecular docking between (A) ribavirin, (B) remdesivir, (C) chloroquine, and (D) FK506 and the spike protein.

Figure 3. Molecular docking between (A) ribavirin, (B) remdesivir, (C) chloroquine, and (D) FK506 and ACE2.

With the spreading of SARS-CoV-2 around the world, the incidence rate is rapidly increasing, and lack of effective treatment options made it a public health threat. Therefore, various strategies are being exploited. Drug repositioning, aiming to offer a potentially valuable opportunity to find new clues of treatment for existing FDA-approved drugs, provides a far more rapid option to the clinic than novel drug design.

In the proposed VDA-RLSBN method, we predicted VDA candidates based on RLS and BLM. However, SARS-CoV-2 is a new coronavirus and has no associated drugs verified by biomedical experiments. We cannot find potential VDAs related to the virus by RLS and BLM. Therefore, we used association information of other RNA viruses similar to SARS-CoV-2 and similarities between SARS-CoV-2 and these viruses. The originality of our proposed method remains, predicting possible antiviral drugs against SARS-CoV-2 by drug repositioning through virus–drug association identification. More importantly, we integrated neighbor association information to RLS to find associated chemical agents for the new virus. The experimental results showed the merits of the VDA-RLSBN model. Higher AUC and AUPR indicated that the predicted antiviral drugs against SARS-CoV-2 are likely to be effective for preventing the rapid transmission of COVID-19.

VDA-RLSBN can obtain superior performance regardless of AUC, AUPR, accuracy, or sensitivity. This observation may be attributed to the following two features. First, VDA-RLSBN divides new VDA prediction into four cases based on BLM, a state-of-the-art method applied in various association prediction areas. More importantly, neighbor association information can help to identify possible antiviral drugs against new viruses (for example, SARS-CoV-2).

The proposed VDA-RLSBN approach is also helpful in designing and interpreting pharmacological experiments. The method can be further applied to select potential antiviral drugs against other new viruses, for example, infectious bronchitis virus.

In this study, we considered the clues of treatment from SARS-CoV, MERS-CoV, and other diseases caused by single-strand RNA viruses and developed a VDA prediction method based on RLS, BLM, and neighbor association information. VDA-RLSBN inferred commercially available small molecular drugs that could be applied to experimental therapy options against SARS-CoV-2. We conducted molecular docking between the predicted four chemical compounds including ribavirin, remdesivir, chloroquine, and FK506 and two target proteins including the spike protein and ACE2. The results show that ribavirin, remdesivir, and chloroquine have better molecular binding activities with ACE2 and may be the best small molecular drugs against SARS-CoV-2. In addition, we found that several antiviral drugs, such as FK506, could be used to combat COVID-19. Nevertheless, the 4 predicted drugs ranked 1, 2, 4, and 6 have been supported by recent works. We hope that our predicted small molecules may be helpful in the prevention of the transmission of SARS-CoV-2.

In the future, we will develop ensemble frameworks (Hu et al., 2018; Peng et al., 2020) and positive-unlabeled learning methods (Lan et al., 2016a; Peng et al., 2017b) to further improve the prediction performance. More importantly, we will enlarge the existing dataset. We will also integrate various biological data including long noncoding RNA (Lan et al., 2017; Zhao et al., 2018; Liu et al., 2020) and disease symptom information (Lan et al., 2016b).

Source code is freely downloadable at: https:// github.com/plhhnu/VDA-RLSBN/.

All datasets presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Material.

LP and XT contributed equally to this work. LP, XT, JY, and LZ designed the VDA-RLSBN method. XT and MK ran VDA-RLSBN. XT wrote the original manuscript. LP, TL, and JY revised the original draft. LS conducted molecular docking for the predicted results. LP, GT, JY, and LZ discussed the proposed method and gave further research. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 61803151) and Natural Science Foundation of Hunan Province (Grant Nos. 2018JJ3570 and 2018JJ2461).

GT, TL, and JY were employed by the company Geneis (Beijing) Co., Ltd.

The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

We are thankful for help from Guangyi Liu and Longjie Liao from Hunan University of Technology; Ruyi Dong, Lebin Liang, Qinqin Lu, and Jidong Lang from Geneis (Beijing) Co., Ltd.; and Junlin Xu from Hunan University. We would like to thank all authors of the cited references.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fgene.2020.577387/full#supplementary-material

Beck, B. R., Shin, B., Choi, Y., Park, S., and Kang, K. (2020). Predicting commercially available antiviral drugs that may act on the novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV), Wuhan, China through a drug-target interaction deep learning model. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 18, 784–790. doi: 10.1016/j.csbj.2020.03.025

Bleakley, K., and Yamanishi, Y. (2009). Supervised prediction of drug–target interactions using bipartite local models. Bioinformatics 25, 2397–2403. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp433

Bonaparte, M. I., Dimitrov, A. S., Bossart, K. N., Crameri, G., Mungall, B. A., Bishop, K. A., et al. (2005). Ephrin-B2 ligand is a functional receptor for Hendra virus and Nipah virus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 10652–10657. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504887102

Canese, K., and Sarah, W. (2013). “PubMed: the bibliographic database,” The NCBI Handbook, 2nd edition. United States: National Center for Biotechnology Information.

Chen, X., Liu, M., and Yan, G. (2012). Drug-target interaction prediction by random walk on the heterogeneous network. Mol. Biosyst. 8, 1970–1978. doi: 10.1039/c2mb00002d

Chen, X., Yan, C. C., Zhang, X., Zhang, X., Dai, F., Yin, J., et al. (2016). Drug-target interaction prediction: databases, web servers and computational models. Brief Bioinform. 17, 696–712. doi: 10.1093/bib/bbv066

Cobbs, C. S., Harkins, L., Samanta, M., Gillespie, G. Y., Bharara, S., King, P. H., et al. (2002). Human cytomegalovirus infection and expression in human malignant glioma. Cancer Res. 62, 3347–3350.

Ding, Y., He, L., Zhang, Q., Huang, Z., Che, X., Hou, J., et al. (2004). Organ distribution of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) associated coronavirus (SARS-CoV) in SARS patients: implications for pathogenesis and virus transmission pathways. J. Pathol. 203, 622–630. doi: 10.1002/path.1560

Gao, H. N., Lu, H., Cao, B., Du, B., Shang, H., Gan, J., et al. (2013). Clinical findings in 111 cases of influenza A (H7N9) virus infection. N. Engl. J. Med. 368, 2277–2285.

Goodsell, D. S., Morris, G. M., and Olson, A. J. (1996). Automated docking of flexible ligands: applications of AutoDock. J. Mol. Recognit. 9, 1–5. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-1352(199601)9:1<1::aid-jmr241>3.0.co;2-6

Groot, R. J. D., Baker, S. C., Baric, R. S., Brown, C. S., Drosten, C., Enjuanes, L., et al. (2013). Commentary: Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV): announcement of the Coronavirus Study Group. J. Virol. 87, 7790–7792.

Guyader, M., Emerman, M., Sonigo, P., Clavel, F., Montagnier, L., and Alizon, M. (1987). Genome organization and transactivation of the human immunodeficiency virus type 2. Nature 326, 662–669. doi: 10.1038/326662a0

Hall, C. B. (2001). Respiratory syncytial virus and parainfluenza virus. N. Engl. J. Med. 344, 1917–1928. doi: 10.1056/nejm200106213442507

Hayden, F. G., and Whitley, R. J. (2020). Respiratory syncytial virus anti-virals: problems and progress. J. Infect. Dis. 2020:jiaa029. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiaa029

Helen, B. M., John, W., Feng, Z., Gary, G., Bhat, T. N., Helge, W., et al. (2000). The protein data bank. Nucleic Acids Res. 28, 235–242.

Hu, H., Zhang, L., Ai, H., Zhang, H., Fan, Y., Zhao, Q., et al. (2018). HLPI-Ensemble: prediction of human lncRNA-protein interactions based on ensemble strategy. RNA Biol. 15, 797–806.

Huang, C., Wang, Y., Li, X., Ren, L., Zhao, J., Hu, Y., et al. (2020). Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan China. Lancet 395, 497–506.

Jacobson, I. M., McHutchison, J. G., Dusheiko, G., Di Bisceglie, A. M. D., Reddy, K. R., Bzowej, N. H., et al. (2011). Telaprevir for previously untreated chronic hepatitis C virus infection. N. Engl. J. Med. 364, 2405–2416.

Kaiser, U. B., Mirmira, R. G., and Stewart, P. M. (2020). Our response to COVID-19 as endocrinologists and diabetologists. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 105:dgaa148.

Kumar, A., Zarychanski, R., Pinto, R., Cook, D., Marshall, J., and Lacroix, J. (2009). Critically ill patients with 2009 influenza A (H1N1) infection in Canada. JAMA 302, 1872–1879. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1496

Laarhoven, T. V., and Marchiori, E. (2013). Predicting drug-target interactions for new drug compounds using a weighted nearest neighbor profile. PLoS One 8:e66952. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0066952

Lan, W., Li, M., Zhao, K., Liu, J., Wu, F., Pan, Y., et al. (2017). LDAP: a web server for lncRNA-disease association prediction. Bioinformatics 33, 458–460.

Lan, W., Wang, J., Li, M., Liu, J., Li, Y., Wu, F. X., et al. (2016a). Predicting drug–target interaction using positive-unlabeled learning. Neurocomputing 206, 50–57. doi: 10.1016/j.neucom.2016.03.080

Lan, W., Wang, J., Li, M., Liu, J., Wu, F., and Pan, Y. (2016b). Predicting MicroRNA-disease associations based on improved MicroRNA and disease similarities. IEEE/ACM Trans. Computat. Biol. Bioinform. 15, 1774–1782. doi: 10.1109/tcbb.2016.2586190

Li, G., and De, C. E. (2020). Therapeutic options for the 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV). Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 19, 149–150. doi: 10.1038/d41573-020-00016-0

Li, J., Lei, K., Wu, Z., Li, W., Liu, G., Liu, J., et al. (2016). Network-based identification of microRNAs as potential pharmacogenomic biomarkers for anticancer drugs. Oncotarget 7, 45584–45596. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.10052

Liu, H., Ren, G., Chen, H., Liu, Q., Yang, Y., and Zhao, Q. (2020). Predicting lncRNA-miRNA interactions based on logistic matrix factorization with neighborhood regularized. Knowl. Based Syst. 191:105261. doi: 10.1016/j.knosys.2019.105261

Lu, H. (2020). Drug treatment options for the 2019-new coronavirus (2019-nCoV). Biosci. Trends 14, 69–71. doi: 10.5582/bst.2020.01020

Morse, J., Lalonde, T., Xu, S., and Liu, W. (2020). Learning from the past: possible urgent prevention and treatment options for severe acute respiratory infections caused by 2019-nCoV. Chembiochem 21, 730–738. doi: 10.1002/cbic.202000047

Peng, L., Liao, B., Zhu, W., Li, Z., and Li, K. (2017a). Predicting drug–target interactions with multi-information fusion. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inform. 21, 561–572. doi: 10.1109/jbhi.2015.2513200

Peng, L., Zhu, W., Liao, B., Duan, Y., Chen, M., Chen, Y., et al. (2017b). Screening drug-target interactions with positive-unlabeled learning. Sci. Rep. 7, 1–17.

Peng, L., Zhou, L., Chen, X., and Piao, X. (2020). A computational study of potential miRNA-disease association inference based on ensemble learning and kernel ridge regression. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 8:40. doi: 10.3389/fbioe.2020.00040

Permpalung, N., Thaniyavarn, T., Saullo, J. L., Arif, S., Miller, R. A., Reynolds, J. M., et al. (2019). Oral and inhaled ribavirin treatment for respiratory syncytial virus infection in lung transplant recipients. Transplantation 104, 1280–1286. doi: 10.1097/TP.0000000000002985

Ruyck, J. D., Brysbaert, G., Blossey, R., and Lensink, M. F. (2016). Molecular docking as a popular tool in drug design, an in silico travel. Adv. Appl. Bioinform. Chem. 9, 1–11. doi: 10.2147/aabc.s105289

Sanche, S., Lin, Y., Xu, C., Severson, E. R., Hengartner, N. W., and Ke, R. (2020). The novel coronavirus, 2019-nCoV, is highly contagious and more infectious than initially estimated. medRxiv [Preprint], doi: 10.1101/2020.02.07.20021154

Sayers, E. W., Beck, J., Brister, J. R., Bolton, E. E., Canese, K., Comeau, D. C., et al. (2020). Database resources of the national center for biotechnology information. Nucleic Acids Res. 48, D9–D16.

Subbarao, K., Klimov, A., Katz, J., Regnery, H., Lim, W., Hall, H., et al. (1998). Characterization of an avian influenza A (H5N1) virus isolated from a child with a fatal respiratory illness. Science 279, 393–396. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5349.393

Wang, C., Wang, S., Li, D., Zhao, X., Han, S., Wang, T., et al. (2020a). Lectin-like intestinal defensin inhibits 2019-nCoV Spike binding to ACE2. bioRxiv [Preprint], doi: 10.1101/2020.03.29.013490

Wang, M., Cao, R., Zhang, L., Yang, X., Liu, J., Xu, M., et al. (2020b). Remdesivir and chloroquine effectively inhibit the recently emerged novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) in vitro. Cell Res. 30, 269–271. doi: 10.1038/s41422-020-0282-0

Wang, W., Tang, J., and Wei, F. (2020c). Updated understanding of the outbreak of 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) in Wuhan, China. J. Med. Virol. 92, 441–447. doi: 10.1002/jmv.25689

Wang, F., Huang, Z., Chen, X., Zhu, Z., Wen, Z., Zhao, J., et al. (2017). LRLSHMDA: laplacian regularized least squares for human microbe–disease association prediction. Sci. Rep. 7:7601.

Wei, X., Ghosh, S. K., Taylor, M. E., Johnson, V. A., Emini, E. A., Deutsch, P., et al. (1995). Viral dynamics in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection. Nature 373, 117–122.

Wishart, D. S., Feunang, Y. D., Guo, A. C., Lo, E. J., Marcu, A., Grant, J. R., et al. (2018). DrugBank 5.0: a major update to the DrugBank database for 2018. Nucleic Acids Res. 46, D1074–D1082.

World Health Organization [WHO] (2020). Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19): Situation Report-190. Available online at: https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/situation-reports/20200729-covid-19-sitrep-191.pdf?sfvrsn=2c327e9e_2 (June 29th, 2020 (accessed June 30, 2020).

Xia, Z., Wu, L. Y., Zhou, X., and Wong, S. T. (2010). Semi-supervised drug-protein interaction prediction from heterogeneous biological spaces. BMC Syst. Biol. 4(Suppl. 2):S6. doi: 10.1186/1752-0509-4-S2-S6

Zhang, H., Saravanan, K. M., Yang, Y., Hossain, M. T., Li, J., Ren, X., et al. (2020a). Deep learning based drug screening for novel coronavirus 2019-nCoV. Interdiscip. Sci. 1, 1–9.

Zhang, Z., Li, X., Zhang, W., Shi, Z., Zheng, Z., and Wang, T. (2020b). Clinical features and treatment of 2019-nCoV pneumonia patients in Wuhan: report of a couple cases. Virol. Sin. 35, 330–336. doi: 10.1007/s12250-020-00203-208

Zhang Lab (2020). Available online at: https://zhanglab.ccmb.med.umich.edu/C-I-TASSER/2019-nCov (accessed May 29, 2020).

Zhao, Q., Yu, H., Ming, Z., Hu, H., Ren, G., and Liu, H. (2018). The bipartite network projection recommended algorithm for predicting long noncoding RNA–protein interactions. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acid 13, 464–471. doi: 10.1016/j.omtn.2018.09.020

Keywords: SARS-CoV-2, antiviral drugs, drug repositioning, virus-drug association, regularized least square, bipartite local model, neighbor association information

Citation: Peng L, Tian X, Shen L, Kuang M, Li T, Tian G, Yang J and Zhou L (2020) Identifying Effective Antiviral Drugs Against SARS-CoV-2 by Drug Repositioning Through Virus-Drug Association Prediction. Front. Genet. 11:577387. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2020.577387

Received: 29 June 2020; Accepted: 18 August 2020;

Published: 16 September 2020.

Edited by:

Wei Lan, Guangxi University, ChinaCopyright © 2020 Peng, Tian, Shen, Kuang, Li, Tian, Yang and Zhou. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Lihong Peng, cGxoaG51QDE2My5jb20=; Jialiang Yang, eWFuZ2psQGdlbmVpcy5jbg==; Liqian Zhou, emhvdWxxMTFAMTYzLmNvbQ==

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.