- 1State Key Laboratory of Crop Genetics and Germplasm Enhancement, Key Laboratory of Biology and Germplasm Enhancement of Horticultural Crops in East China, Ministry of Agriculture, Nanjing Agricultural University, Nanjing, China

- 2Hunan Vegetable Research Institute, Changsha, China

- 3College of Horticulture, Hunan Agricultural University, Changsha, China

Plant basic helix–loop–helix (bHLH) transcription factors are involved in the regulation of various biological processes in plant growth, development, and stress response. However, members of this important transcription factor family have not been systematically identified and analyzed in pepper (Capsicum annuum L.). In this study, we identified 122 CabHLH genes in the pepper genome and renamed them based on their chromosomal locations. CabHLHs were divided into 21 subfamilies according to their phylogenetic relationships, and genes from the same subfamily had similar motif compositions and gene structures. Sixteen pairs of tandem and segmental duplicated genes were detected in the CabHLH family. Cis-elements identification and expression analysis of the CabHLHs revealed that they may be involved in plant development and stress responses. This study is the first comprehensive analysis of the CabHLH genes and will serve as a reference for further characterization of their molecular functions.

Introduction

The bHLH transcription factor (TF) family, named for its basic helix–loop–helix (bHLH) structure, is the second largest class of TFs and is widely distributed in animals, plants, and microorganisms (Guo et al., 2008). The bHLH domain consists of approximately 60 amino acids and is divided into a basic amino acid region and a helix–loop–helix region (Toledo-Ortiz et al., 2003). The basic region is located on the N-terminal side of the bHLH domain and is approximately 15 amino acids in length. These amino acids are mainly responsible for binding to cis-elements in DNA. The HLH region is located on the C-terminal side of the domain, consists of approximately 40 amino acids, and promotes the formation of homo- and heterodimer complexes (Murre et al., 1989; Ferre-D’Amare et al., 1994).

According to their evolutionary relationships, DNA binding abilities, and functional characteristics, bHLH proteins in animals have been divided into six groups, A–F (Atchley and Fitch, 1997). Many of the plant bHLH proteins that have been identified belong to Group B (Sailsbery and Dean, 2012). According to classification criteria developed in animals, the 133 bHLH genes found in Arabidopsis thaliana have been divided into 12 subfamilies based on conserved amino acids at specific positions and on the presence or absence of additional conserved domains (Heim et al., 2003). Fourteen new bHLH TFs were subsequently discovered and further divided among 21 subfamilies, but this classification was limited to higher terrestrial plants (Toledo-Ortiz et al., 2003). As more family members were identified in species such as moss and seaweed, bHLH TFs were subdivided into 32 subfamilies (Carretero-Paulet et al., 2010). At present, the classification of the plant bHLH TF family is not clearly defined, and there are no corresponding names for each subfamily across species.

In plants, bHLH TFs are involved in various signal transduction and anabolic pathways, such as light signal transduction (Duek and Fankhauser, 2003; Castillon et al., 2007), anthocyanin synthesis (Ludwig et al., 1989; Goodrich et al., 1992; Quattrocchio et al., 1993; Nesi et al., 2000; Sakamoto et al., 2001), tryptophan synthesis (Smolen et al., 2002) and gibberellin synthesis (Arnaud et al., 2010). They also modulate stress responses, including responses to low temperature (LTR) (Feng et al., 2012; Lin et al., 2014; Xu et al., 2014), heat (Ko et al., 2009), drought (Li et al., 2007; Seo et al., 2011), and salt (Murre et al., 1989; Zhou et al., 2009; Liu et al., 2014). For example, Arabidopsis TT8 (AtbHLH42) typically regulates the synthesis of anthocyanins and procyanidins of vegetative organs through the formation of MYB-bHLH-WD (MBW) complexes, specifically the TT2-TT8-TTG1 complex (Baudry et al., 2004). AtNIG1 was the first bHLH TF shown to be involved in the plant salt stress signaling pathway, and Arabidopsis atnig1-1 knockout mutants are significantly more sensitive to salt stress than wild-type plants (Kim and Kim, 2006). AtbHLH122 overexpressing plants have stronger salt and anti-osmotic capacity than wild-type plants (Liu et al., 2014). The expression level of AtbHLH92 is upregulated under NaCl, drought and cold stress (Jiang et al., 2009). In rice, OsbHLH148 regulates the expression of genes associated with jasmonic acid signaling and serves as an initial response factor during drought stress, thereby participating in both drought and trauma responses (Kiribuchi et al., 2004). OsbHLH1 can be specifically induced by cold stress, but is not induced by salt, PEG and ABA (Wang et al., 2003). OsHLH006 participates in drought and wounding responses through the jasmonic acid signaling pathway (Kiribuchi et al., 2005).

Pepper (Capsicum annuum L.) is an economically important vegetable and the most widely grown cooking ingredient in the world. With the completion of the pepper genome sequence (Qin et al., 2014), genome-wide identification and classification of gene families can be performed to study genes that are critical for pepper growth and development. To date, a number of TF families have been characterized in pepper, such as the Dof (Wu et al., 2016) and Hsp70 (Guo et al., 2016) families. However, the pepper bHLH family has not been characterized previously. Here, we use a bioinformatics approach to identify and characterize members of the bHLH family in pepper. We report basic information about each gene, including its conserved domains, evolutionary relationships, chromosomal location, expression in various pepper tissues, and response to abiotic stress. These data provide a reference for further exploration of the molecular functions of bHLH genes in regulating pepper growth and stress responses.

Materials and Methods

Identification of the bHLH Gene Family

Annotated sequences of pepper and tomato genes were downloaded from the Solanaceae Genomics Network1, and annotated sequences of Arabidopsis bHLHs were obtained from TAIR2. We used HMMER 3.0 (Eddy, 1998) to identify Arabidopsis, tomato and pepper sequences that contained the complete bHLH domain (PF00010), using an E-value < 1e–5 threshold. Candidate sequences were verified using the SMART4 and NCBI databases5. Sequences with confirmed bHLH domains were retained for further analysis.

Phylogenetic Analysis and Classification of the CabHLH Gene Family

The sequences of the CabHLH and AtbHLH proteins were extracted, and a multiple alignment of the sequences was performed using ClustalW 2.0 (Larkin et al., 2007). A phylogenetic tree was constructed in MEGA 7.0 using the neighbor joining (NJ) method (Tamura et al., 2007) with the following parameters: 1,000 bootstrap replicates, Poisson model, and pairwise deletion. CabHLHs were placed into subfamilies based on the classification of closely related AtbHLHs and the bootstrap support values at relevant nodes.

Protein Properties, Conserved Motifs and Gene Structures

CabHLH protein sequences were uploaded to the ExPASy website6 to calculate their molecular weights (MW) and isoelectric points (pI). MEME tools7 v5.1.1 (Bailey et al., 2009) were used to identify up to ten conserved motifs in each CabHLH protein with an optimal motif width of 10–200 residues and all other parameters set to their default values. Intron locations were determined based on the GFF3 files of Arabidopsis, pepper and tomato sequences. Gene structures were drawn using TBtools v0.66833 (Chen et al., 2020).

Chromosomal Mapping and Gene Duplication Analysis

The chromosomal positions of the CabHLH genes were obtained from the gene annotation file and visualized using MapGene2Chromosome8 v2. Within a genome, homologous gene pairs located within 100 kb on the same chromosome were considered to be tandem duplicates, whereas blocks of genes copied from one region to another were considered to be segmental duplications (Tang et al., 2008; Liu et al., 2011). Segmental and tandem duplicated gene pairs within the pepper genome and collinear gene pairs among the pepper, tomato and Arabidopsis genomes were identified using MCScanX with a match score of 50, a match size of 5, a gap score of -3, and an E-value of 1e–05 (Wang et al., 2012). The non-synonymous substitution rate (Ka) and synonymous substitution rate (Ks) were calculated using KaKs_Calculator 2.0 (Wang et al., 2010), and a collinearity map was drawn with Circos software (Krzywinski et al., 2009).

Analysis of cis-Regulatory Elements

SeqKit v0.13.0 (Shen et al., 2016) was used to extract the promoter sequences of each CabHLH gene from the pepper genome file, 2000 bp upstream of the ATG start codon. Promoters were uploaded to the PlantCARE website9 (Lescot et al., 2002) to predict their cis-elements.

Expression Analysis of the CabHLH Genes

RNA-Seq data were used to examine the expression of CabHLH genes in multiple tissues and in response to various abiotic stress treatments (Liu et al., 2017). The expression level of each gene was calculated as FPKM (fragments per kilobase of transcript per million mapped reads), transformed as log2 (FPKM + 1). Finally, expression heatmaps were generated in R v3.6.1.

Seeds of the pepper cultivar “6421,” which exhibits good heat, drought, and disease tolerance, were obtained from the Vegetable Institute of the Hunan Academy of Agricultural Sciences. Plants were grown using the substrate floating seedling method at 24/16°C with a 16 h light/8 h dark photoperiod. Following a previously published treatment protocol (Liu et al., 2017), 40-day-old replicate pepper seedlings were exposed to 200 mM NaCl (salt stress), 400 mM mannitol (drought), 10°C (cold stress), or 42°C (heat stress). Salt stress was imposed by adding NaCl to a final concentration of 200 mM in the nutrient solution, and drought stress was applied by adding D-mannitol to a final concentration of 400 mM. For heat and cold stress treatments, the seedlings were transferred to a growth chamber at 42 or 10°C, and the illumination, photoperiod, and relative humidity were identical to those in the control treatment. Leaf tissue of treated and control plants was sampled at four time points 1, 6, 12, and 24 h after treatment initiation. Samples of treated and control plants were harvested at 7:00, 12:00, and 18:00 h on the first day and at 6:00 h on the following day. Three seedlings were randomly selected and combined to create one biological replicate, and three biological replicates were collected for each treatment and time point. Samples were frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at -80°C until further use.

Total RNA was extracted from frozen leaf samples using an RNA kit (TaKaRa, Dalian, China) and reverse transcribed into cDNA with a PrimeScript RT reagent kit (TaKaRa). The SYBR Premix Ex Taq kit (TaKaRa) was used to measure relative gene expression levels following the manufacturer’s instructions of the One-step Real-Time PCR System Time PCR Detection System (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, United States). The cycling steps were 94°C for 30 s, 94°C for 10 s for 40 cycles, and 58°C for 30 s, followed by melting curve analysis at 65°C for 10 s for 61 cycles. The relative expression levels of selected genes were calculated using the 2−ΔΔCt method (Schmittgen and Livak, 2008).

Results

Identification, Phylogenetic Analysis, Classification and Protein Properties of the CabHLH Genes

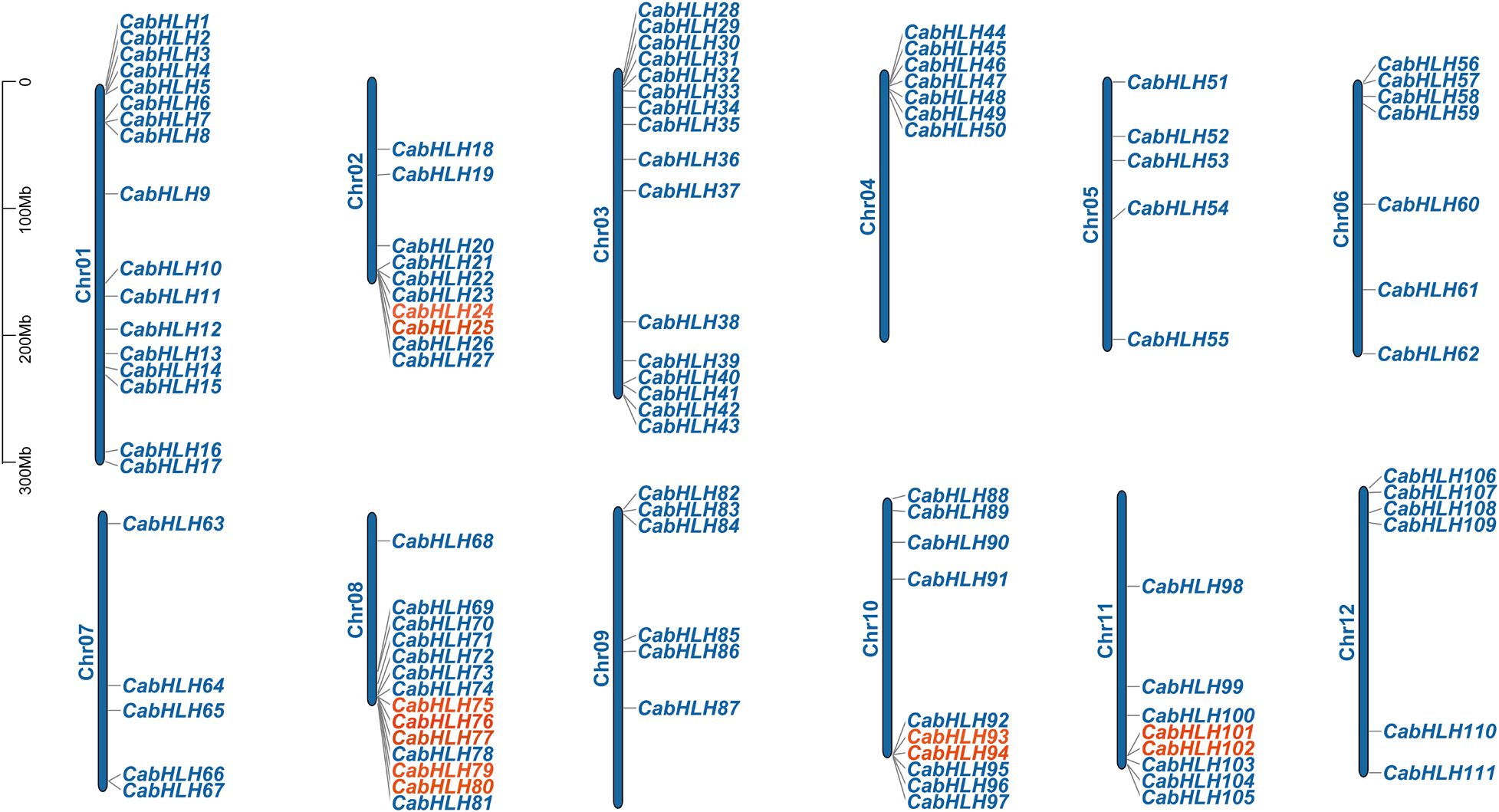

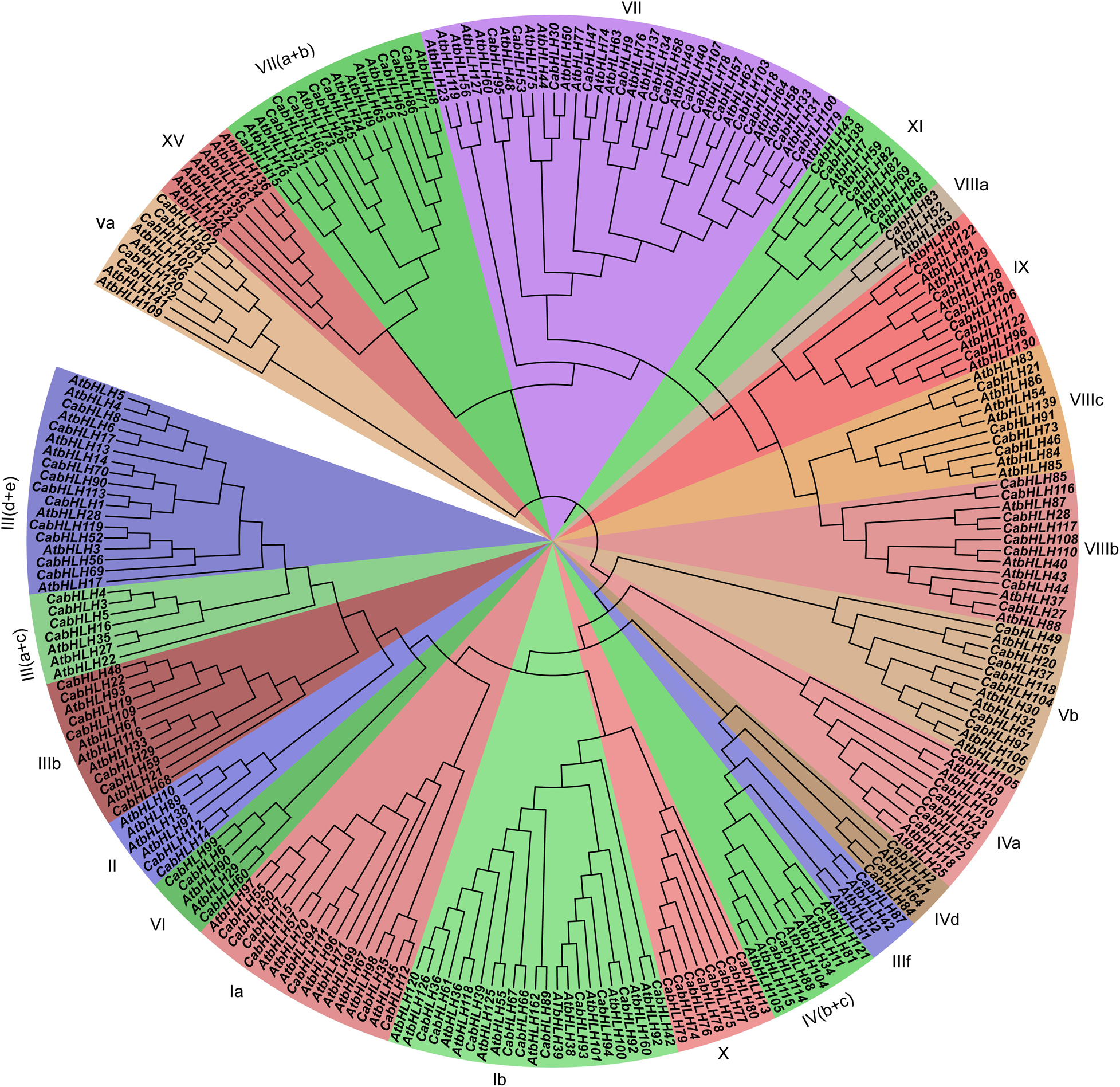

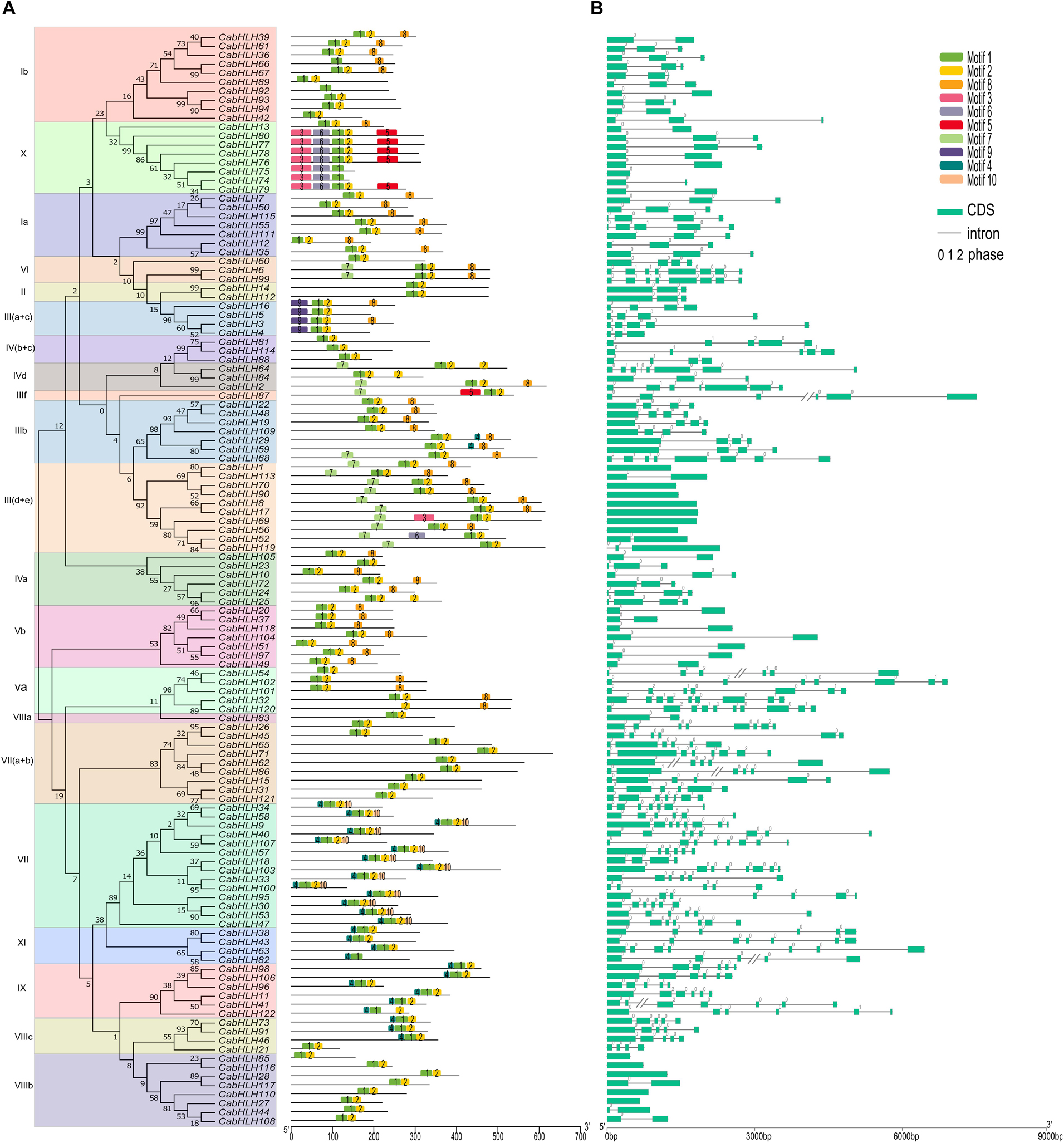

We used HMMER 3.0 to search for bHLH domains (PF00010) in the pepper and tomato proteins using an E-value threshold of <1e–5. All candidate sequences were filtered with NCBI and SMART to further confirm that they contained complete bHLH domains. A total of 122 CabHLHs and 140 SlbHLHs were identified (Supplementary Table S1); the pepper bHLH genes were named CabHLH1 to CabHLH122 based on their arrangement on the pepper chromosomes. We constructed a phylogenetic tree of CabHLH and AtbHLH proteins in order to investigate their evolutionary relationships and to classify the CabHLHs into 21 established subfamilies according to the classifications of their Arabidopsis homologs (Li et al., 2006). Subfamily VII had the largest number of members in pepper (14 genes), whereas subfamilies IIIf and VIIIa had the fewest (one gene each) (Figure 1). Compared with Arabidopsis, pepper had no members of the XV subfamily but contained a unique X subfamily. In many cases, Arabidopsis and pepper had different numbers of genes in a given subfamily.

Figure 1. Phylogenetic analyses of bHLH proteins from pepper and Arabidopsis. The phylogenetic tree was constructed by MEGA7 using the neighbor-joining (NJ) method (1,000 bootstrap). Subfamilies were displayed by different colors.

Comprehensive information on the CabHLH genes, including locus names, gene positions, protein lengths, exon numbers, molecular weights (MW), and isoelectric points (pI), is provided in Supplementary Table S2. The CabHLH proteins range in size from 117 (CabHLH21) to 633 (CabHLH71) amino acids, with an average length of approximately 344 amino acids. The MWs of the CabHLH proteins range from 12.9 kDa (CabHLH31) to 69.3 kDa (CabHLH2), and their pIs range from 4.6 (CabHLH48) to 10.32 (CabHLH108). The CabHLH genes contain 1 to 10 exons, highlighting the diversity of their structures.

Chromosome Locations and Duplication Analysis of the CabHLH Genes

A total of 111 CabHLH genes were located on 12 chromosomes (91%) (Figure 2), and the other 11 genes were mapped to scaffolds (CabHLH112-122). CabHLH genes were unevenly distributed on the 12 chromosomes, with the largest number of CabHLHs on chromosome 1 (17 genes) and the smallest number on chromosomes 5 and 7 (five genes each). Chromosomes 3, 8, 2, 10, 11, 6, 4, 12, and 9 contained 16, 14, 10, 10, 8, 7, 7, 6, and 6 CabHLH genes, respectively. CabHLHs from each subfamily were also unevenly distributed among the chromosomes, and most CabHLHs were clustered at the ends of the chromosomes.

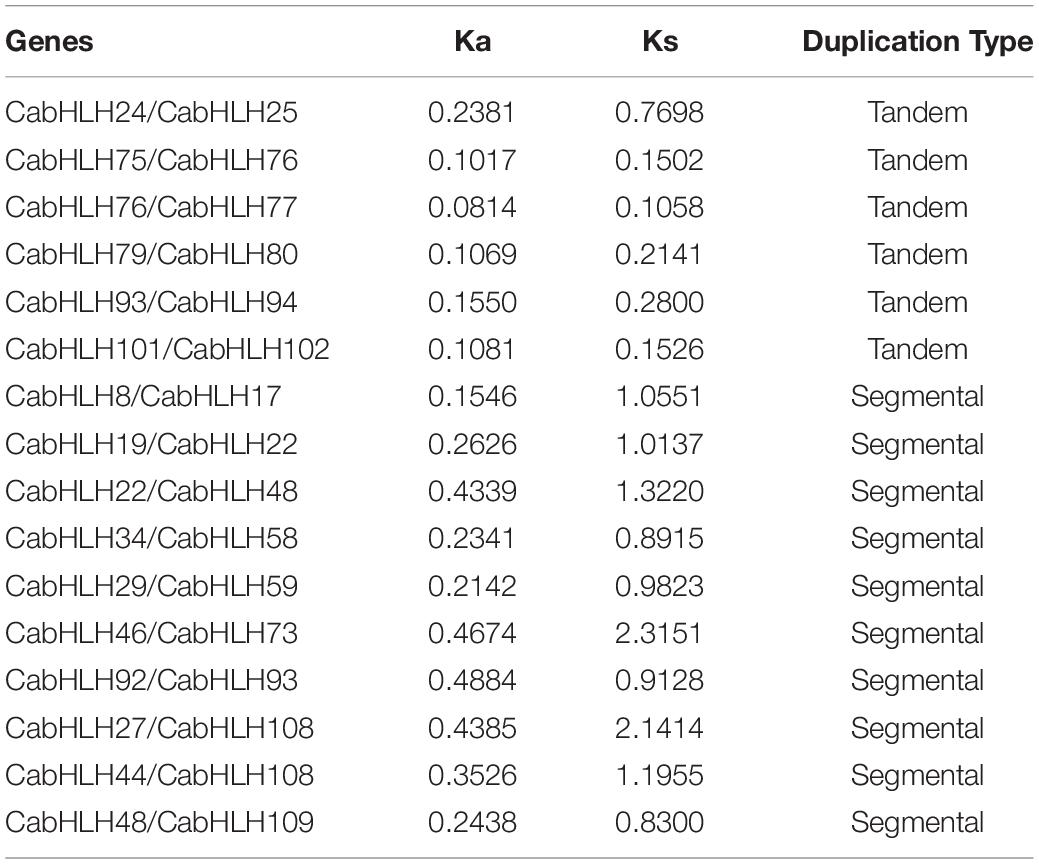

We analyzed the locations of CabHLH duplicates in the C. annuum genome, as tandem duplicates and segmental duplicates play an important role in the expansion of gene families and the generation of new gene functions. As shown in Figure 2, we identified six pairs of tandem duplicates on chromosomes 2, 8, 10, and 11: CabHLH24/25, CabHLH75/76, CabHLH76/77, CabHLH79/80, CabHLH93/94, and CabHLH101/102. In addition, ten gene pairs (CabHLH8/17, CabHLH19/22, CabHLH22/48, CabHLH34/58, CabHLH29/59, CabHLH46/73, CabHLH92/93, CabHLH27/108, CabHLH44/108, CabHLH48/109) appeared to have arisen through segmental duplication (Figure 3). To determine the order of these duplication events, we used the synonymous substitution rate (Ks) to estimate the duplicate divergence times. All segmental duplicates had larger Ks values (0.83–2.32) than did tandem duplicates (0.11–0.77), indicating that they had a relatively earlier origin (Table 1). In addition, the Ks values of CabHLH46/73 and CabHLH27/108 were significantly greater than those of other segmental duplicates, showing that they derived from more ancient duplication events.

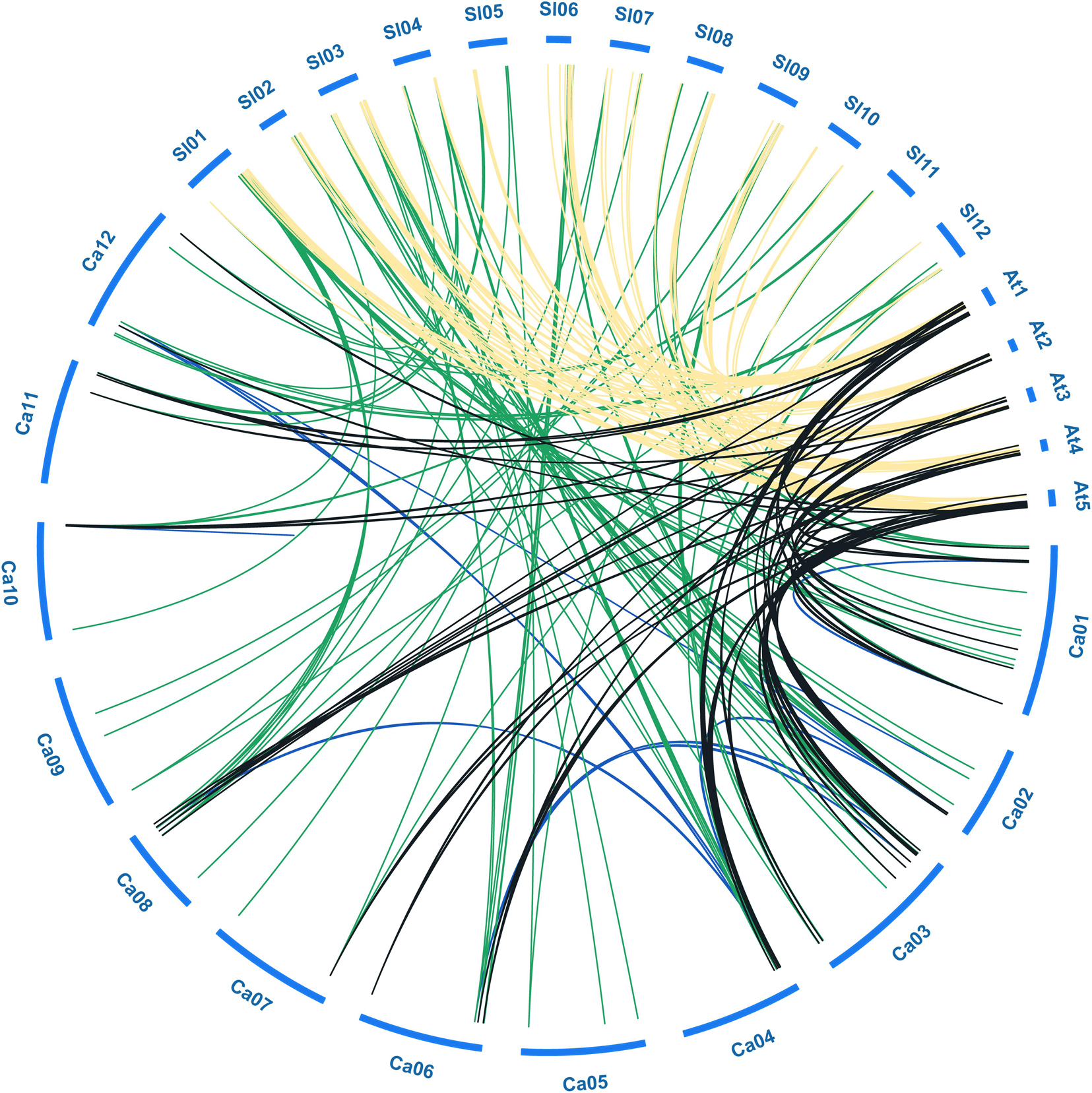

Figure 3. Collinear analysis of bHLH genes among pepper (Ca), tomato (Sl), and Arabidopsis (At). Green, black and yellow lines represent the collinear gene pairs between pepper and tomato, pepper and Arabidopsis, tomato and Arabidopsis chromosomes, respectively. Blue lines indicate the segmental duplicated bHLH genes in pepper.

To further explore the evolutionary relationships among bHLH TFs from different species, we constructed a collinearity plot of the pepper, tomato, and Arabidopsis bHLH gene families (Figure 3). A total of 117, 64, and 105 collinear gene pairs were identified between pepper and tomato, pepper and Arabidopsis, and tomato and Arabidopsis, respectively, indicating that significant expansion of the gene family had occurred before divergence of the three species (Supplementary Table S3). For example, 44 CabHLHs and 54 AtbHLHs had a collinear relationship, and most such relationships were one-to-one matches such as CabHLH2/AtbHLH2 and CabHLH12/AtbHLH45. There were also one-to-many matches, such as CabHLH17/(AtbHLH4, AtbHLH5, AtbHLH6) and CabHLH23/(AtbHLH18, AtbHLH25). Many-to-one cases also existed, such as (CabHLH6, CabHLH8, CabHLH17)/AtbHLH4 and (CabHLH27, CaHLH108, CabHLH44)/AtbHLH88. These results indicate that bHLHs are relatively conserved and that collinear bHLHs between species may originate from the same ancestor.

Gene Structure and Motif Analysis of CabHLH Family

Conserved motifs of the CabHLH proteins were analyzed using MEME tools, and ten conserved motifs from 26 to 154 amino acids in length were identified (Supplementary Figure S1). The number of conserved motifs in each CabHLH protein varied from one to five (Figure 4). Each subfamily contained several common motifs, while few subfamilies possessed unique motifs. For example, motifs 1 and 2 were present in almost all CabHLH proteins and represented the position of the bHLH domain, whereas motifs 9 and 10 were only found in subfamilies III (a + c) and VII, respectively, and may be related to unique functions of individual subfamilies. CabHLH proteins from the same subfamily exhibited similar motifs, suggesting that they may also share a degree of functional similarity. The diversity of motifs in different subfamilies suggests that CabHLH functions have tended to diversify during evolution.

Figure 4. Exon–intron structures of CabHLH genes and conserved motifs of CabHLH proteins. (A) Exon–intron organization of CabHLH genes. Green boxes represent exons and black lines indicate introns. The numbers 0, 1, and 2 denote the intron phases. (B) Conserved motifs in the CabHLH proteins. The conserved motifs were identified using MEME with complete protein sequences. Different motifs are displayed by various colors.

We used TBtools to map the structures of the pepper, tomato and Arabidopsis bHLH genes (Figure 4, Supplementary Figure S2) and found that most bHLHs from the same subfamily shared similar gene structures. For example, subfamily III (d + e) contains 0–2 introns, subfamily IX has 4–6 introns. Intron gain and loss is a frequent phenomenon during evolution and can increase the complexity of gene structures (Roy and Gilbert, 2005). In the CabHLHs, most tandem duplicates (5/6) had different numbers of introns, whereas most segmental duplicates (7/10) had the same number of introns, suggesting that tandem duplicates may have undergone greater divergence in gene function over the course of evolution. In addition, we also analyzed the introns of collinear bHLH pairs. There were 53, 31, and 46 pairs of collinear bHLH pairs with different numbers of introns between pepper and tomato, pepper and Arabidopsis, and tomato and Arabidopsis, respectively, indicating that the functions of these collinear genes may have undergone a degree of differentiation (Supplementary Table S3).

Cis-Element Analysis of the CabHLH Genes

We extracted the 2,000 bp upstream promoter sequences of the CabHLH genes for cis-element analysis using the PlantCARE database. Ten common cis-elements were identified (Supplementary Table S4), and 119 CabHLHs contained at least one cis-element. The ABRE, CGTCA-motif, and GARE-motif elements respond to ABA, JA, and GA stimulation, These motifs were present in the promoters of 86, 77, and 27 CabHLHs, suggesting that the expression of these genes responds to levels of the corresponding hormones. Two light-responsive elements (G-box and Sp1) that are ubiquitous in plants were identified in 90 and 12 CabHLHs, respectively. Stress-responsive cis-elements, including those associated with LTR, defense and stress (TC-rich repeats), drought (MBS), and anaerobic induction (ARE), were identified in the promoters of 33, 42, 52, and 27 CabHLHs, respectively. Diverse response elements indicate the importance of CabHLHs in stress responses.

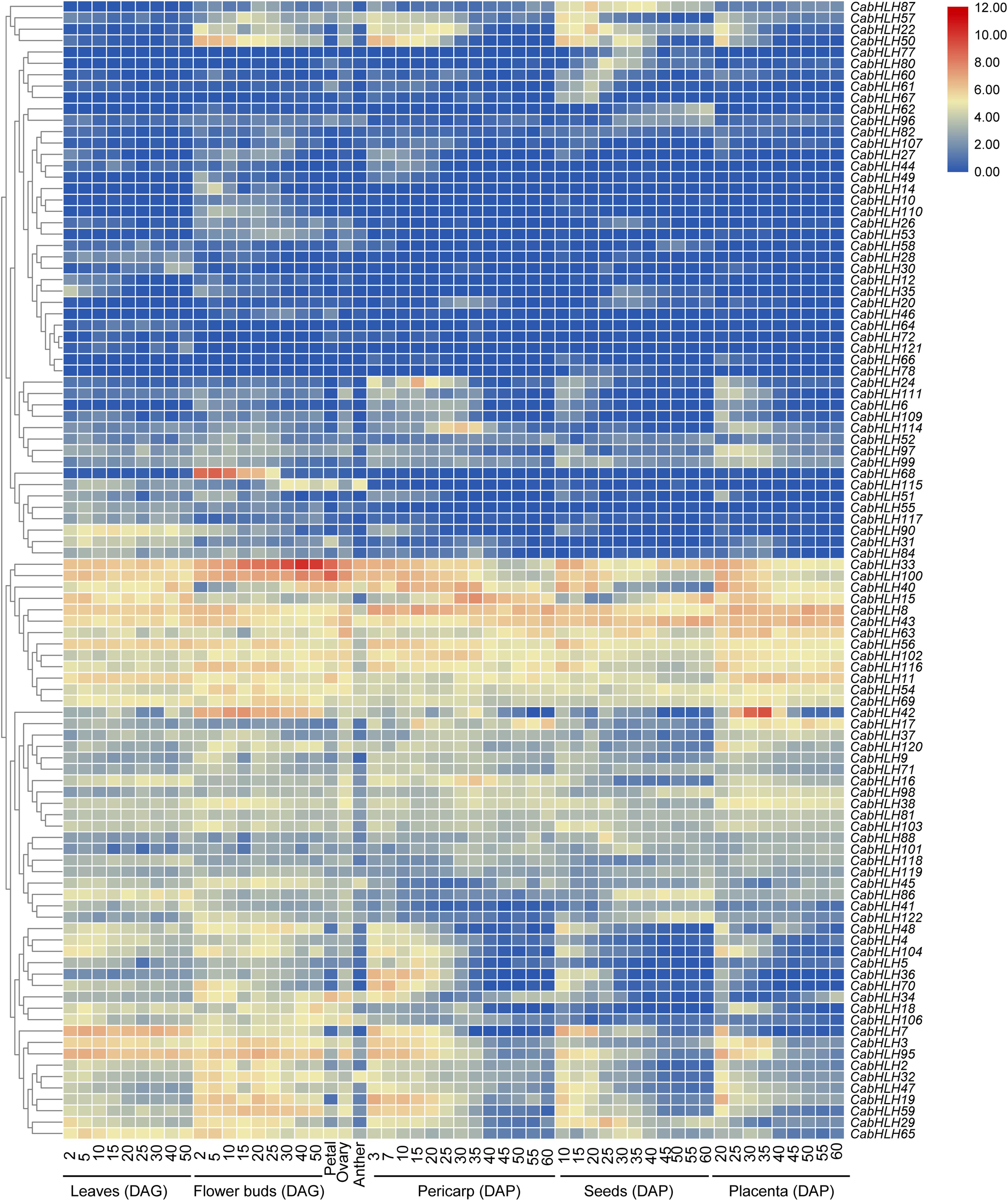

Expression Patterns of CabHLH Genes in Various Tissues

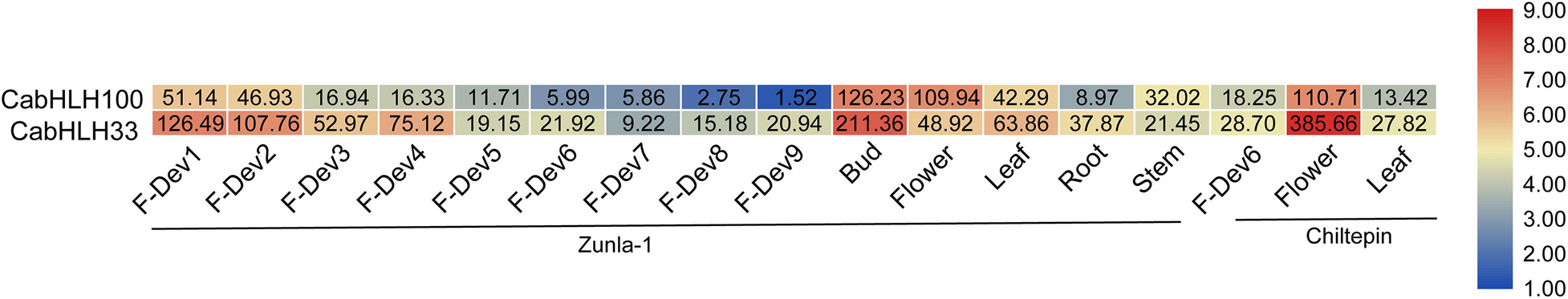

We obtained the expression data of CabHLH genes from previous research (Liu et al., 2017) and removed 22 CabHLH genes with FPKM values of less than one in all tissues (Zhuo et al., 2018). An expression heatmap was created using the remaining 100 genes (Figure 5, Supplementary Table S5). Most CabHLHs differed in their expression patterns, although a few showed similar expression patterns. Some CabHLHs (such as CabHLH100, CabHLH11, CabHLH8, and CabHLH43) showed high expression levels (FPKM > 10) in most tissues analyzed, whereas other CabHLHs (such as CabHLH23, CabHLH85, CabHLH39, CabHLH105, and CabHLH108) were not expressed in any tissues. In addition, several CabHLHs showed extremely high expression in specific tissues, such as CabHLH33/CabHLH100 in flower buds, CabHLH33 in petals, and CabHLH42 in the placenta. We obtained transcriptome data for CabHLH33 and CabHLH100 from another study and found that their expression was also significantly higher in flowers or flower buds than in any other tissues (Figure 6) (Qin et al., 2014). These genes may therefore have specific roles in flower development. We also analyzed the expression of duplicated genes in various tissues and found that most duplicated gene pairs had similar expression patterns, such as CabHLH48/CabHLH109, CabHLH75/CabHLH76, and CabHLH46/CabHLH73, which were expressed at low levels in most tissues. By contrast, the expression of CabHLH34 in flowers was much higher than that of its duplicate CabHLH58, and the expression of CabHLH8 was higher than that of its duplicate CabHLH17 in all tissues analyzed.

Figure 5. Expression patterns of CabHLH genes in different tissues and organs. Heatmap of expression profiles [in log2 (FPKM + 1)] for CabHLH genes in different tissues and organs. The expression levels are displayed by the color bar. DAG, days after germination; DAP, days after pollination.

Figure 6. Heatmap of expression profiles [in log 2 (RPKM + 1)] of CabHLH33 and CabHLH100 in two pepper cultivars “Zunla-1” (Capsicum annuum L.) and “Chiltepin” (C. annuum var. glabriusculum). The expression levels are displayed by the color bar. F-Dev-1, F-Dev-2, F-Dev-3, F-Dev-4, and F-Dev-5 (0–1 cm, 1–3 cm, 3–4 cm, 4–5 cm, and mature green fruit), F-Dev-6 (fruit turning red), F-Dev-7, F-Dev-8, and F-Dev-9 (3, 5, and 7 days after turning red). RPKM, reads per kilobase million.

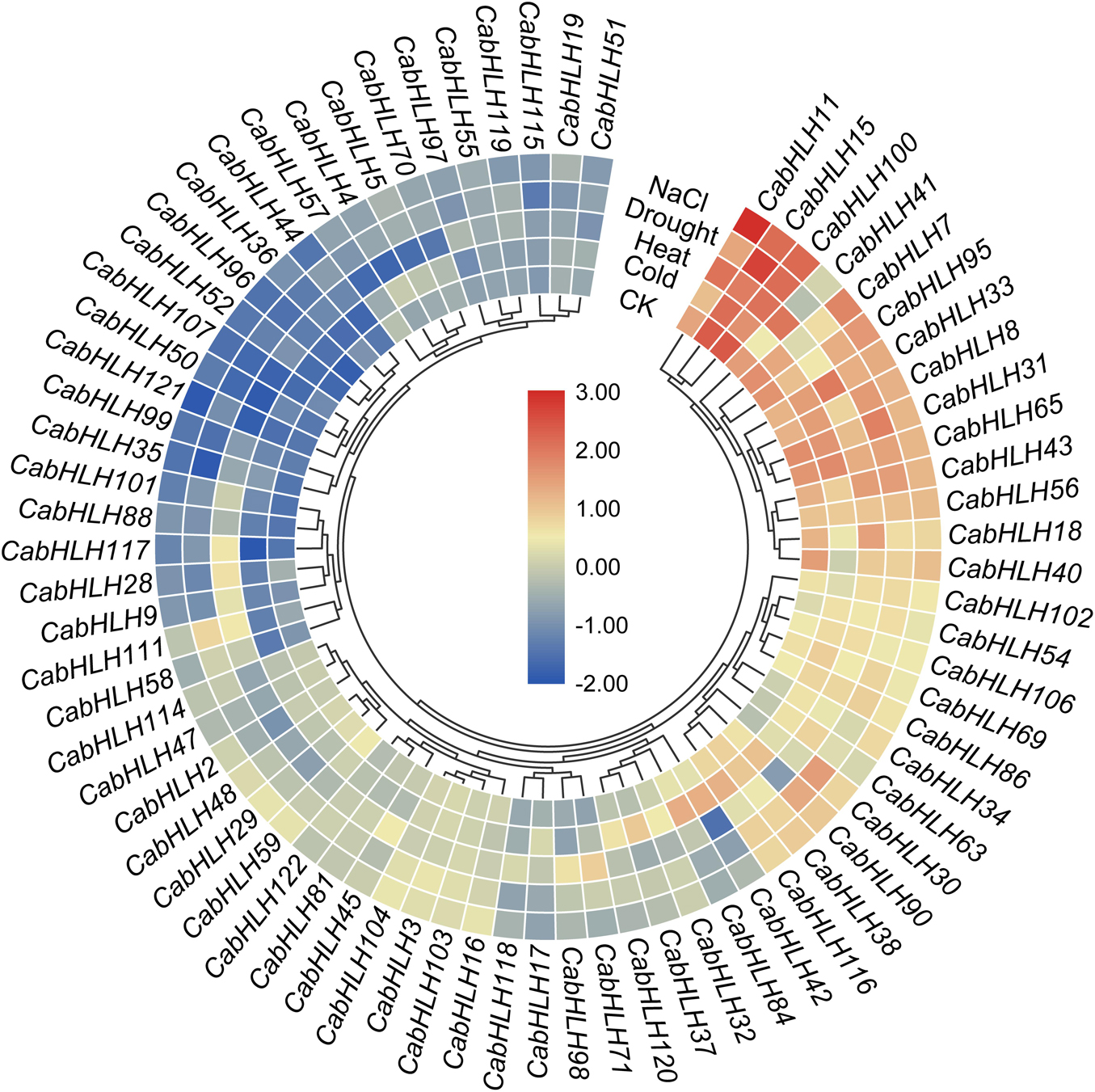

Expression Analysis of CabHLH Genes Under Abiotic Stresses

To analyze the response of the CabHLH genes to abiotic stress, we extracted transcriptome data for CabHLH gene expression after 6 h of cold, heat, salt, and drought stress. We used genes with FPKM values of bigger than one in at least one group to create a clustered heatmap and found many CabHLHs responded to abiotic stress (Figure 7, Supplementary Table S6). We also analyzed the relationship between transcriptome data and cis-elements and found that gene expression results were not clearly correlated with the presence/absence of specific cis-elements. For example, some CabHLHs with LTR promoter elements, such as CabHLH5/17/32/65/90, were upregulated under LTR treatment. However, some CabHLHs with LTR elements, such as CabHLH16/36/48/114, were downregulated or remained unchanged (Figure 7). This result indicates that the expression of these CabHLHs might induced by several cis-elements, and unidentified cis-elements might contribute to regulating the expression of these CabHLHs under abiotic stress.

Figure 7. Expression heatmap of CabHLH genes under multiple abiotic treatments. The color scale represents log2 (FPKM + 1) values.

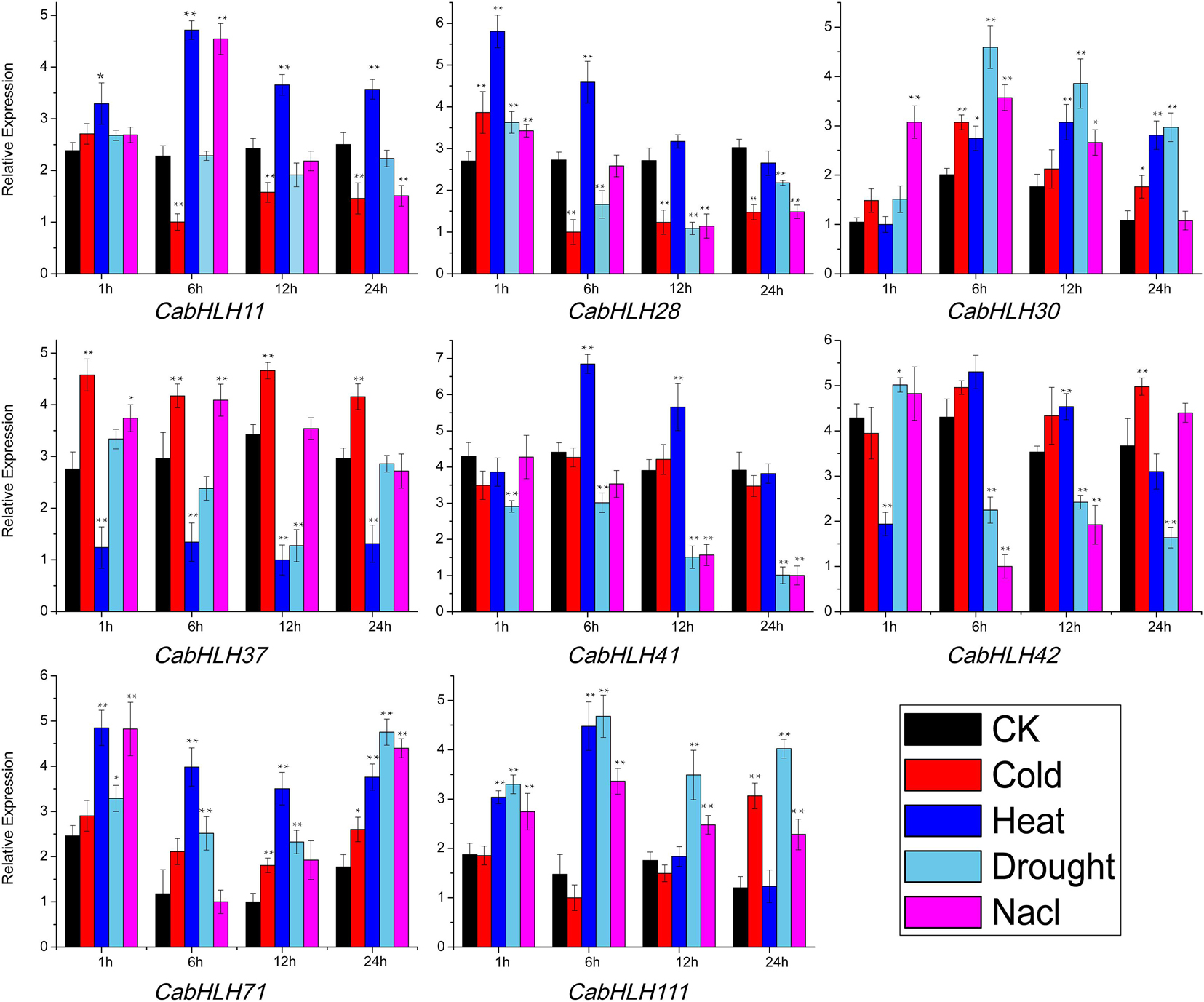

To further validate the effects of abiotic stress on the expression of CabHLH genes, we selected eight genes that responded to abiotic stress (Supplementary Table S6) and verified the expression patterns of these genes using qRT-PCR (Figure 8). The specific primers used are listed in Supplementary Table S7. After cold stress treatment, the expression levels of CabHLH30, CabHLH37, CabHLH42, CabHLH71, and CabHLH111 were upregulated, CabHLH11 was downregulated, CabHLH28 was first upregulated and then downregulated, and CabHLH41 remained unchanged. After high temperature treatment, the expression levels of CabHLH37 and CabHLH42 were downregulated, and the expression levels of the remaining genes were upregulated. After drought treatment, CabHLH30, CabHLH71, and CabHLH111 were upregulated, CabHLH41 and CabHLH37 were downregulated, and CabHLH42 was first upregulated and then downregulated. Under salt stress, the expression levels of CabHLH30, CabHLH37, CabHLH71, and CabHLH111 were upregulated, CabHLH11 and CabHLH28 were first upregulated and then downregulated, CabHLH41 and CabHLH42 were downregulated. In general, there was good correspondence between the RNA-seq data and the qRT-PCR results. However, few exceptions existed. For example, in the qRT-PCR experiment, the expression level of CabHLH11 decreased after 6 h of cold treatment, but its expression was unchanged in the RNA-seq analysis, perhaps due to different sampling time points (qRT-PCR at 12:00, RNA-seq at 14:00).

Figure 8. qRT-PCR analysis of CabHLH genes under cold, heat, salt and drought treatments following a 24 h time course. y-axis: relative expression levels; x-axis: the time (hours) course of stress treatments. t-test: one asterisk denotes significant differences (P < 0.05) between treatment group and control group (CK); two asterisks denote extremely significant differences (P < 0.01).

Discussion

A growing body of evidence suggests that plant bHLH genes are involved in physiological and biochemical processes such as stress resistance, growth and development, biosynthesis, and signaling (Duek and Fankhauser, 2003; Hernandez et al., 2004; Castillon et al., 2007). Members of the bHLH TF family have been identified in Arabidopsis (Toledo-Ortiz et al., 2003), rice (Li et al., 2006), apple (Yang et al., 2017), cabbage (Song et al., 2014), tomato (Sun et al., 2015), ginseng (Chu et al., 2018), and other species by comparative genomics. Until now, this family had not been characterized in pepper. In this study, we systematically analyzed the pepper bHLH TF family and provided a reference for further exploration of the roles of bHLH genes in regulation of pepper growth and stress responses.

A total of 122 CabHLH genes were identified and classified into 21 subfamilies according to their phylogenetic relationships with known bHLH genes from Arabidopsis (Li et al., 2006). Compared with Arabidopsis, pepper lacks members of the XV subfamily but contains a unique X subfamily. The acquired genes may counter gene losses, or even evolve novel functions (Qian et al., 2010). The functions of some AtbHLHs have been identified in previous studies. For example, AtbHLH15 and AtbHLH8 from subfamily VII (a + b) can combine with active phytochromes and mediate light signaling responses (Castillon et al., 2007). AtbHLH44, AtbHLH58, and AtbHLH50 in subfamily VII are early response BR signaling components required for full BR response (Friedrichsen et al., 2002). Overexpression of AtbHLH116 from subfamily IIIb in wild-type plants improves the expression of the CBF regulon in the cold and enhances freezing tolerance of transgenic plants (Chinnusamy et al., 2003). AtbHLH1 from subfamily IIIf encodes a bHLH protein that regulates trichome development in Arabidopsis through interaction with GLABRA3 and TESTA GLABRA1 (Payne et al., 2000). CabHLHs and AtbHLHs from the same subfamilies may have similar functions, although this will require further experimental verification.

Gene duplication, including tandem duplication and segmental duplication, is the most important pathway for the evolution and expansion of gene families (Vision et al., 2000). We identified six tandem duplicated CabHLHs and ten segmental duplicated CabHLHs in the pepper genome. Collinear genes derive from a common ancestor and are present in the same relative positions in the genomes of two or more species. We identified 117, 64 and 105 collinear bHLH pairs between pepper and tomato, Arabidopsis and pepper, and Arabidopsis and tomato, respectively. In the process of evolution, collinear blocks may be disrupted by various factors. The greater the evolutionary distance, the fewer collinear gene pairs will be identified between species, and collinearity can therefore be used as a measure of the evolutionary distance between species (Wicker et al., 2010). There were more collinear gene pairs between tomato and pepper, consistent with the fact that both are members of the Solanaceae family (Qin et al., 2014). Previous studies have shown that the amplification of transposable elements has eroded collinearity in the pepper genome (Wicker et al., 2010; Qin et al., 2014), which may explain why the number of collinear gene pairs between pepper and Arabidopsis is much lower than that between Arabidopsis and tomato.

We identified ten highly conserved motifs in the CabHLH proteins. Similar to the bHLHs of potato, lotus and Arabidopsis (Wang et al., 2018; Mao et al., 2019), motif 1 and motif 2 were present in almost all CabHLH proteins and represented the position of the bHLH domain, which is highly conserved among species. However, motif 9 and 10 were only present in subfamilies III (a + c) and VII, respectively. Variation in conserved motifs permits the classification of proteins into subfamilies and reflects each subfamily’s specific functions (Jiang et al., 2019). Gene structure can also provide information for the study of gene family evolution (Guo et al., 2013). The number of introns varied from 0 to 9, indicating that the gain and loss of introns had occurred, which may be another reason for the differences among CabHLH subfamilies (Paquette et al., 2000).

We analyzed the expression profiles of CabHLHs in different tissues and found a large variety of expression patterns. Some CabHLHs (such as CabHLH100, CabHLH11, CabHLH8, and CabHLH43) were highly expressed (FPKM > 10) in most tissues analyzed and may participating in various development processes of pepper. Several CabHLHs were highly expressed in specific tissues, suggesting that they may have a role in those tissues’ development. For example, CabHLH33, a homolog of AtbHLH31, was highly expressed in flower buds and petals. Previous studies suggest that AtbHLH31 regulates petal growth by controlling cell expansion (Varaud et al., 2011), and CabHLH33 may have a similar function in pepper. However, CabHLHs that were not expressed in any tissues (such as CabHLH23, CabHLH85, CabHLH39, CabHLH105, and CabHLH108) may have lost their functions during evolution and become pseudogenes, as has been demonstrated in the evolution of other plant genomes (Innan and Kondrashov, 2010; Xie et al., 2019). In addition, several duplicated pairs (such as CabHLH34/CabHLH58 and CabHLH8/CabHLH17) had significantly different expression patterns, indicating that functional diversification of duplicated CabHLH pairs had occurred during the course of evolution (Blanc and Wolfe, 2004).

Plant bHLHs modulate stress responses, including responses to LTR (Feng et al., 2012; Lin et al., 2014; Xu et al., 2014), drought (Li et al., 2007; Seo et al., 2011), heat (Ko et al., 2009), and salt (Murre et al., 1989; Zhou et al., 2009; Liu et al., 2014). In this work, cis-element analysis indicated that CabHLHs contained elements (such as LTR, ABRE, and TC-rich) that are responsive to various stresses, which was consistent with previous research on potato and lotus bHLHs (Wang et al., 2018; Mao et al., 2019). In addition, we extracted the transcriptome data of CabHLHs and performed a qRT-PCR experiment to validate the response of the CabHLH genes to abiotic stress. These upregulated CabHLHs (such as CabHLH30/37/42/71/111 under cold, CabHLH11/28/30/41/71/111 under heat, CabHLH30/71/111 under drought, and CabHLH30/37/71/111 under NaCl) may regulate downstream bHLH-related genes, thus enhancing the stress tolerance of pepper. Our research provides a framework for further functional characterization of CabHLH genes.

Data Availability Statement

All datasets presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Material.

Author Contributions

ZZ, FL, XH, and XZ conceived and designed the experiments. ZZ, JC, and CL performed the experiments. ZZ, CL, FL, and XH analyzed data. ZZ and XZ wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2019YFD1000300).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fgene.2020.570156/full#supplementary-material

FIGURE S1 | Sequence logos of conserved motifs of CabHLHs.

FIGURE S2 | Exon-intron structures of AtbHLHs and SlbHLHs. The phylogenetic tree of AtbHLHs and SlbHLH proteins was constructed by MEGA7 using the neighbor-joining (NJ) method (1,000 bootstrap). Green boxes represent exons and black lines indicate introns.

TABLE S1 | Genes with complete bHLH domain in pepper, tomato, and Arabidopsis.

TABLE S2 | Basic information of the CabHLH transcription factor family.

TABLE S3 | Collinear bHLHs among tomato, pepper and Arabidopsis.

TABLE S4 | Cis-elements analysis of the CabHLH genes.

TABLE S5 | The FPKM values of CabHLH genes in different tissues and organs.

TABLE S6 | FPKM values of CabHLH genes under salt, drought, cold, and heat stress.

TABLE S7 | Primer sequences used in qRT-PCR.

Footnotes

- ^ https://solgenomics.net/

- ^ https://www.Arabidopsis.org/

- ^ http://smart.embl-heidelberg.de/

- ^ http://smart.embl-heidelberg.de/

- ^ http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/

- ^ http://web.expasy.org/

- ^ http://meme-suite.org

- ^ http://mg2c.iask.in/mg2c_v2.0/

- ^ http://bioinformatics.psb.ugent.be/webtools/plantcare/html/

References

Arnaud, N., Girin, T., Sorefan, K., Fuentes, S., Wood, T. A., Lawrenson, T., et al. (2010). Gibberellins control fruit patterning in Arabidopsis thaliana. Genes Dev. 24, 2127–2132. doi: 10.1101/gad.593410

Atchley, W. R., and Fitch, W. M. (1997). A natural classification of the basic helix-loop-helix class of transcription factors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci U.S.A. 94, 5172–5176. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.10.5172

Bailey, T. L., Boden, M., Buske, F. A., Frith, M., Grant, C. E., Clementi, L., et al. (2009). MEME SUITE: tools for motif discovery and searching. Nucleic Acids Res. 37, W202–W208. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp335

Baudry, A., Heim, M. A., Dubreucq, B., Caboche, M., Weisshaar, B., and Lepiniec, L. (2004). TT2, TT8, and TTG1 synergistically specify the expression of BANYULS and proanthocyanidin biosynthesis in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 39, 366–380. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2004.02138.x

Blanc, G., and Wolfe, K. H. (2004). Widespread paleopolyploidy in model plant species inferred from age distributions of duplicate genes. Plant Cell 16, 1667–1678. doi: 10.1105/tpc.021345

Carretero-Paulet, L., Galstyan, A., Roig-Villanova, I., Martinez-Garcia, J. F., Bilbao-Castro, J. R., and Robertson, D. L. (2010). Genome-wide classification and evolutionary analysis of the bHLH family of transcription factors in Arabidopsis, poplar, rice, moss, and algae. Plant Physiol. 153, 1398–1412. doi: 10.1104/pp.110.153593

Castillon, A., Shen, H., and Huq, E. (2007). Phytochrome Interacting Factors: central players in phytochrome-mediated light signaling networks. Trends Plant Sci. 12, 514–521. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2007.10.001

Chen, C., Chen, H., Zhang, Y., Thomas, H. R., Frank, M. H., He, Y., et al. (2020). TBtools: an integrative toolkit developed for interactive analyses of big biological data. Mol. Plant 13, 1194–1202. doi: 10.1016/j.molp.2020.06.009

Chinnusamy, V., Ohta, M., Kanrar, S., Lee, B. H., Hong, X., Agarwal, M., et al. (2003). ICE1: a regulator of cold-induced transcriptome and freezing tolerance in Arabidopsis. Genes Dev. 17, 1043–1054. doi: 10.1101/gad.1077503

Chu, Y., Xiao, S., Su, H., Liao, B., Zhang, J., Xu, J., et al. (2018). Genome-wide characterization and analysis of bHLH transcription factors in Panax ginseng. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 8, 666–677. doi: 10.1016/j.apsb.2018.04.004

Duek, P. D., and Fankhauser, C. (2003). HFR1, a putative bHLH transcription factor, mediates both phytochrome A and cryptochrome signalling. Plant J. 34, 827–836. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2003.01770.x

Eddy, S. R. (1998). Profile hidden Markov models. Bioinformatics 14, 755–763. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/14.9.755

Feng, X. M., Zhao, Q., Zhao, L. L., Qiao, Y., Xie, X. B., Li, H. F., et al. (2012). The cold-induced basic helix-loop-helix transcription factor gene MdCIbHLH1 encodes an ICE-like protein in apple. BMC Plant Biol. 12:22. doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-12-22

Ferre-D’Amare, A. R., Pognonec, P., Roeder, R. G., and Burley, S. K. (1994). Structure and function of the b/HLH/Z domain of USF. EMBO J. 13, 180–189. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06247.x

Friedrichsen, D. M., Nemhauser, J., Muramitsu, T., Maloof, J. N., Alonso, J., Ecker, J. R., et al. (2002). Three redundant brassinosteroid early response genes encode putative bHLH transcription factors required for normal growth. Genetics 162, 1445–1456.

Goodrich, J., Carpenter, R., and Coen, E. S. (1992). A common gene regulates pigmentation pattern in diverse plant species. Cell 68, 955–964. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90038-e

Guo, A. Y., Chen, X., Gao, G., Zhang, H., Zhu, Q. H., Liu, X. C., et al. (2008). PlantTFDB: a comprehensive plant transcription factor database. Nucleic Acids Res. 36, D966–D969. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm841

Guo, M., Liu, J. H., Ma, X., Zhai, Y. F., Gong, Z. H., and Lu, M. H. (2016). Genome-wide analysis of the Hsp70 family genes in pepper (Capsicum annuum L.) and functional identification of CaHsp70-2 involvement in heat stress. Plant Sci. 252, 246–256. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2016.07.001

Guo, R., Xu, X., Carole, B., Li, X., Gao, M., Zheng, Y., et al. (2013). Genome-wide identification, evolutionary and expression analysis of the aspartic protease gene superfamily in grape. BMC Genomics 14:554. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-14-554

Heim, M. A., Jakoby, M., Werber, M., Martin, C., Weisshaar, B., and Bailey, P. C. (2003). The basic helix-loop-helix transcription factor family in plants: a genome-wide study of protein structure and functional diversity. Mol. Biol. Evol. 20, 735–747. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msg088

Hernandez, J. M., Heine, G. F., Irani, N. G., Feller, A., Kim, M. G., Matulnik, T., et al. (2004). Different mechanisms participate in the R-dependent activity of the R2R3 MYB transcription factor C1. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 48205–48213. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M407845200

Innan, H., and Kondrashov, F. (2010). The evolution of gene duplications: classifying and distinguishing between models. Nat. Rev. Genet. 11, 97–108. doi: 10.1038/nrg2689

Jiang, S. Y., Jin, J., Sarojam, R., and Ramachandran, S. (2019). A comprehensive survey on the terpene synthase gene family provides new insight into its evolutionary patterns. Genome Biol. Evol. 11, 2078–2098. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evz142

Jiang, Y., Yang, B., and Deyholos, M. K. (2009). Functional characterization of the Arabidopsis bHLH92 transcription factor in abiotic stress. Mol. Genet. Genomics 282, 503–516. doi: 10.1007/s00438-009-0481-3

Kim, J., and Kim, H. Y. (2006). Functional analysis of a calcium-binding transcription factor involved in plant salt stress signaling. FEBS Lett. 580, 5251–5256. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2006.08.050

Kiribuchi, K., Jikumaru, Y., Kaku, H., Minami, E., Hasegawa, M., Kodama, O., et al. (2005). Involvement of the basic helix-loop-helix transcription factor RERJ1 in wounding and drought stress responses in rice plants. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 69, 1042–1044. doi: 10.1271/bbb.69.1042

Kiribuchi, K., Sugimori, M., Takeda, M., Otani, T., Okada, K., Onodera, H., et al. (2004). RERJ1, a jasmonic acid-responsive gene from rice, encodes a basic helix-loop-helix protein. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 325, 857–863. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.10.126

Ko, D. K., Lee, M. O., Hahn, J. S., Kim, B. G., and Hong, C. B. (2009). Submergence-inducible and circadian rhythmic basic helix-loop-helix protein gene in Nicotiana tabacum. J. Plant Physiol. 166, 1090–1100. doi: 10.1016/j.jplph.2008.12.008

Krzywinski, M., Schein, J., Birol, I., Connors, J., Gascoyne, R., Horsman, D., et al. (2009). Circos: an information aesthetic for comparative genomics. Genome Res. 19, 1639–1645. doi: 10.1101/gr.092759.109

Larkin, M. A., Blackshields, G., Brown, N. P., Chenna, R., McGettigan, P. A., McWilliam, H., et al. (2007). Clustal W and Clustal X version 2.0. Bioinformatics 23, 2947–2948. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm404

Lescot, M., Dehais, P., Thijs, G., Marchal, K., Moreau, Y., Van de Peer, Y., et al. (2002). PlantCARE, a database of plant cis-acting regulatory elements and a portal to tools for in silico analysis of promoter sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 30, 325–327. doi: 10.1093/nar/30.1.325

Li, H., Sun, J., Xu, Y., Jiang, H., Wu, X., and Li, C. (2007). The bHLH-type transcription factor AtAIB positively regulates ABA response in Arabidopsis. Plant Mol. Biol. 65, 655–665. doi: 10.1007/s11103-007-9230-3

Li, X., Duan, X., Jiang, H., Sun, Y., Tang, Y., Yuan, Z., et al. (2006). Genome-wide analysis of basic/helix-loop-helix transcription factor family in rice and Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 141, 1167–1184. doi: 10.1104/pp.106.080580

Lin, Y., Zheng, H., Zhang, Q., Liu, C., and Zhang, Z. (2014). Functional profiling of EcaICE1 transcription factor gene from Eucalyptus camaldulensis involved in cold response in tobacco plants. J. Plant Biochem. Biotechnol. 23, 141–150. doi: 10.1007/s13562-013-0192-z

Liu, F., Yu, H., Deng, Y., Zheng, J., Liu, M., Ou, L., et al. (2017). PepperHub, an informatics hub for the chili pepper research community. Mol. Plant 10, 1129–1132. doi: 10.1016/j.molp.2017.03.005

Liu, W., Tai, H., Li, S., Gao, W., Zhao, M., Xie, C., et al. (2014). bHLH122 is important for drought and osmotic stress resistance in Arabidopsis and in the repression of ABA catabolism. New Phytol. 201, 1192–1204. doi: 10.1111/nph.12607

Liu, Y., Jiang, H., Chen, W., Qian, Y., Ma, Q., Cheng, B., et al. (2011). Genome-wide analysis of the auxin response factor (ARF) gene family in maize (Zea mays). Plant Growth Regul. 63, 225–234. doi: 10.1007/s10725-010-9519-0

Ludwig, S. R., Habera, L. F., Dellaporta, S. L., and Wessler, S. R. (1989). Lc, a member of the maize R gene family responsible for tissue-specific anthocyanin production, encodes a protein similar to transcriptional activators and contains the myc-homology region. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci U.S.A. 86, 7092–7096. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.18.7092

Mao, T. Y., Liu, Y. Y., Zhu, H. H., Zhang, J., Yang, J. X., Fu, Q., et al. (2019). Genome-wide analyses of the bHLH gene family reveals structural and functional characteristics in the aquatic plant Nelumbo nucifera. PeerJ 7:e7153. doi: 10.7717/peerj.7153

Murre, C., McCaw, P. S., and Baltimore, D. (1989). A new DNA binding and dimerization motif in immunoglobulin enhancer binding, daughterless, MyoD, and myc proteins. Cell 56, 777–783. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90682-x

Nesi, N., Debeaujon, I., Jond, C., Pelletier, G., Caboche, M., and Lepiniec, L. (2000). The TT8 gene encodes a basic helix-loop-helix domain protein required for expression of DFR and BAN genes in Arabidopsis siliques. Plant Cell 12, 1863–1878. doi: 10.1105/tpc.12.10.1863

Paquette, S. M., Bak, S., and Feyereisen, R. (2000). Intron-exon organization and phylogeny in a large superfamily, the paralogous cytochrome P450 genes of Arabidopsis thaliana. DNA Cell Biol. 19, 307–317. doi: 10.1089/10445490050021221

Payne, C. T., Zhang, F., and Lloyd, A. M. (2000). GL3 Encodes a bHLH Protein That Regulates Trichome Development in Arabidopsis Through Interaction With GL1 and TTG1. Genetics 156, 1349–1362.

Qian, W., Liao, B. Y., Chang, A. Y., and Zhang, J. (2010). Maintenance of duplicate genes and their functional redundancy by reduced expression. Trends Genet. 26, 425–430. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2010.07.002

Qin, C., Yu, C., Shen, Y., Fang, X., Chen, L., Min, J., et al. (2014). Whole-genome sequencing of cultivated and wild peppers provides insights into Capsicum domestication and specialization. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci U.S.A. 111, 5135–5140. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1400975111

Quattrocchio, F., Wing, J. F., Leppen, H., Mol, J., and Koes, R. E. (1993). Regulatory Genes Controlling Anthocyanin Pigmentation Are Functionally Conserved among Plant Species and Have Distinct Sets of Target Genes. Plant Cell 5, 1497–1512. doi: 10.1105/tpc.5.11.1497

Roy, S. W., and Gilbert, W. (2005). Rates of intron loss and gain: implications for early eukaryotic evolution. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci U.S.A. 102, 5773–5778. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0500383102

Sailsbery, J. K., and Dean, R. A. (2012). Accurate discrimination of bHLH domains in plants, animals, and fungi using biologically meaningful sites. BMC Evol. Biol. 12:154. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-12-154

Sakamoto, W., Ohmori, T., Kageyama, K., Miyazaki, C., Saito, A., Murata, M., et al. (2001). The Purple leaf (Pl) locus of rice: the Pl(w) allele has a complex organization and includes two genes encoding basic helix-loop-helix proteins involved in anthocyanin biosynthesis. Plant Cell Physiol. 42, 982–991. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pce128

Schmittgen, T. D., and Livak, K. J. (2008). Analyzing real-time PCR data by the comparative C(T) method. Nat. Protoc. 3, 1101–1108. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.73

Seo, J. S., Joo, J., Kim, M. J., Kim, Y. K., Nahm, B. H., Song, S. I., et al. (2011). OsbHLH148, a basic helix-loop-helix protein, interacts with OsJAZ proteins in a jasmonate signaling pathway leading to drought tolerance in rice. Plant J. 65, 907–921. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2010.04477.x

Shen, W., Le, S., Li, Y., and Hu, F. (2016). SeqKit: a cross-platform and ultrafast toolkit for FASTA/Q file manipulation. PLoS One 11:e0163962. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0163962

Smolen, G. A., Pawlowski, L., Wilensky, S. E., and Bender, J. (2002). Dominant alleles of the basic helix-loop-helix transcription factor ATR2 activate stress-responsive genes in Arabidopsis. Genetics 161, 1235–1246.

Song, X. M., Huang, Z. N., Duan, W. K., Ren, J., Liu, T. K., Li, Y., et al. (2014). Genome-wide analysis of the bHLH transcription factor family in Chinese cabbage (Brassica rapa ssp. pekinensis). Mol. Genet. Genomics 289, 77–91. doi: 10.1007/s00438-013-0791-3

Sun, H., Fan, H. J., and Ling, H. Q. (2015). Genome-wide identification and characterization of the bHLH gene family in tomato. BMC Genomics 16:9. doi: 10.1186/s12864-014-1209-2

Tamura, K., Dudley, J., Nei, M., and Kumar, S. (2007). MEGA4: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis (MEGA) software version 4.0. Mol. Biol. Evol. 24, 1596–1599. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msm092

Tang, H., Bowers, J. E., Wang, X., Ming, R., Alam, M., and Paterson, A. H. (2008). Synteny and collinearity in plant genomes. Science 320, 486–488. doi: 10.1126/science.1153917

Toledo-Ortiz, G., Huq, E., and Quail, P. H. (2003). The Arabidopsis basic/helix-loop-helix transcription factor family. Plant Cell 15, 1749–1770. doi: 10.1105/tpc.013839

Varaud, E., Brioudes, F., Szecsi, J., Leroux, J., Brown, S., Perrot-Rechenmann, C., et al. (2011). AUXIN RESPONSE FACTOR8 regulates Arabidopsis petal growth by interacting with the bHLH transcription factor BIGPETALp. Plant Cell 23, 973–983. doi: 10.1105/tpc.110.081653

Vision, T. J., Brown, D. G., and Tanksley, S. D. (2000). The origins of genomic duplications in Arabidopsis. Science 290, 2114–2117. doi: 10.1126/science.290.5499.2114

Wang, D., Zhang, Y., Zhang, Z., Zhu, J., and Yu, J. (2010). KaKs_Calculator 2.0: a toolkit incorporating gamma-series methods and sliding window strategies. Genomics Proteomics Bioinformatics 8, 77–80. doi: 10.1016/S1672-0229(10)60008-3

Wang, R., Zhao, P., Kong, N., Lu, R., Pei, Y., Huang, C., et al. (2018). Genome-wide identification and characterization of the potato bHLH transcription factor family. Genes 9:54. doi: 10.3390/genes9010054

Wang, Y., Tang, H., Debarry, J. D., Tan, X., Li, J., Wang, X., et al. (2012). MCScanX: a toolkit for detection and evolutionary analysis of gene synteny and collinearity. Nucleic Acids Res. 40:e49. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr1293

Wang, Y. J., Zhang, Z. G., He, X. J., Zhou, H. L., Wen, Y. X., Dai, J. X., et al. (2003). A rice transcription factor OsbHLH1 is involved in cold stress response. Theor. Appl. Genet. 107, 1402–1409. doi: 10.1007/s00122-003-1378-x

Wicker, T., Buchmann, J. P., and Keller, B. (2010). Patching gaps in plant genomes results in gene movement and erosion of colinearity. Genome Res. 20, 1229–1237. doi: 10.1101/gr.107284.110

Wu, Z., Cheng, J., Cui, J., Xu, X., Liang, G., Luo, X., et al. (2016). Genome-wide identification and expression profile of Dof transcription factor gene family in pepper (Capsicum annuum L.). Front. Plant Sci. 7:574. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2016.00574

Xie, J., Li, Y., Liu, X., Zhao, Y., Li, B., Ingvarsson, P. K., et al. (2019). Evolutionary origins of Pseudogenes and their association with regulatory sequences in plants. Plant Cell 31, 563–578. doi: 10.1105/tpc.18.00601

Xu, W., Jiao, Y., Li, R., Zhang, N., Xiao, D., Ding, X., et al. (2014). Chinese wild-growing Vitis amurensis ICE1 and ICE2 encode MYC-type bHLH transcription activators that regulate cold tolerance in Arabidopsis. PLoS One 9:e102303. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0102303

Yang, J., Gao, M., Huang, L., Wang, Y., van Nocker, S., Wan, R., et al. (2017). Identification and expression analysis of the apple (Malus x domestica) basic helix-loop-helix transcription factor family. Sci. Rep. 7:28. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-00040-y

Zhou, J., Li, F., Wang, J. L., Ma, Y., Chong, K., and Xu, Y. Y. (2009). Basic helix-loop-helix transcription factor from wild rice (OrbHLH2) improves tolerance to salt- and osmotic stress in Arabidopsis. J. Plant Physiol. 166, 1296–1306. doi: 10.1016/j.jplph.2009.02.007

Keywords: genome-wide, pepper, bHLH transcription factor family, phylogenetic relationships, expression analysis

Citation: Zhang Z, Chen J, Liang C, Liu F, Hou X and Zou X (2020) Genome-Wide Identification and Characterization of the bHLH Transcription Factor Family in Pepper (Capsicum annuum L.). Front. Genet. 11:570156. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2020.570156

Received: 06 June 2020; Accepted: 03 September 2020;

Published: 25 September 2020.

Edited by:

Wei Chen, North China University of Science and Technology, ChinaReviewed by:

Xiyin Wang, North China University of Science and Technology, ChinaPeng Wu, Yangzhou University, China

Copyright © 2020 Zhang, Chen, Liang, Liu, Hou and Zou. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Feng Liu, bGl1ZmVuZ3JpY2hAMTI2LmNvbQ==; Xilin Hou, aHhsQG5qYXUuZWR1LmNu; Xuexiao Zou, em91eHVleGlhbzQyOEAxNjMuY29t

Zhishuo Zhang

Zhishuo Zhang Juan Chen2

Juan Chen2 Xilin Hou

Xilin Hou Xuexiao Zou

Xuexiao Zou