- Key Laboratory of Animal Genetics, Breeding and Reproduction of Shaanxi Province, College of Animal Science and Technology, Northwest A&F University, Yangling, China

SETDB1, a histone H3 lysine 9 (H3K9) methyltransferase, is crucial in meiosis and embryo development. This study aimed to investigate whether SETDB1 was associated with spermatogonial stem cells (SSC) homeostasis. We found that knockdown of Setdb1 impaired cell proliferation, led to an increase in reactive oxygen species (ROS) level through NADPH oxidase, and Setdb1 deficiency activated ROS downstream signaling pathways, including JNK and p38 MAPK, which possibly contributed to SSC apoptosis. Melatonin scavenged ROS and rescued the phenotype of Setdb1 KD. In addition, we demonstrated that SETDB1 regulated NADPH oxidase 4 (Nox4) and E2F1. Therefore, this study uncovers the new roles of SETDB1 in mediating intracellular ROS homeostasis for the survival of SSC.

Introduction

Male fertility depends on spermatogenesis, by which the haploid spermatozoa generate in the testes. This process starts with the mitosis of the spermatogonial stem cells (SSCs), followed by meiosis of spermatocytes. Finally, the haploid spermatids transform into spermatozoa (Kanatsu-Shinohara and Shinohara, 2013). This highly organized process of spermatogenesis requires timely coordinated gene expression that is regulated at the transcriptional and post-transcription levels (McSwiggin and O’Doherty, 2018). Histone modification has been implicated in the regulation of gene expression.

Histone H3 lysine 9 (H3K9) can be methylated by the methyltransferase SETDB1 (Mozzetta et al., 2015). Notably, the global level of H3K9me3 and SETDB1 gradually increases during development of the testes (An et al., 2014). Loss of Setdb1 resulted in a reduced number of PGCs and postnatal hypogonadism (Liu et al., 2015). Moreover, depletion of Setdb1 at postnatal day 7 caused germ cell apoptosis at the pachytene stage and defects in XY body formation (Hirota et al., 2018). Setdb1 depletion induced SSC apoptosis through upregulating apoptotic inducers and downregulating apoptotic suppressors, and upregulating cytochrome c oxidase subunit IV isoform 2 (Cox4i2) through decreasing H3K9me3 (An et al., 2014). The up-regulation of COX4i2 is associated with elevated mitochondria-produced reactive oxygen species (ROS) (Singh et al., 2009).

The active NADPH oxidase (NOX) generates superoxide, which spontaneously recombines with other molecules to produce reactive free radicals (Katsuyama et al., 2012; Lambeth and Neish, 2014). Under physiological conditions, the intracellular ROS are thought to act as a second messenger in cell signaling (Bigarella et al., 2014; Lambeth and Neish, 2014; Wang et al., 2018). Recent studies found that ROS generated by NOX1 and NOX3 was essential for SSC self-renewal (Morimoto et al., 2013, 2015). Ablation of Nox1 severely compromises SSC self-renewal, and Nox3-depletion causes apoptosis and impairs SSC proliferation. However, the accumulated ROS is toxic to the cells. Enhancing the expression of NOX4 in cardiac myocytes induces apoptosis and mitochondrial dysfunction (Ago et al., 2010). Excessive ROS causes apoptosis through the p38 MAPK-p16 pathway in hematopoietic stem cells (Ito et al., 2006). High levels of ROS could also induce oxidative stress and activation of FOXO4 that is a regulator of cell cycle, cell death, and cell metabolism (Essers et al., 2004; Urbich et al., 2005; Eijkelenboom and Burgering, 2013). Importantly, oxidative stress is associated with male infertility (Bui et al., 2018). Thus, modest levels of ROS benefits cell proliferation, while accumulated ROS impairs cells. However, the function of SETDB1 in intracellular ROS homeostasis remains elusive. In this study, we revealed that Setdb1 deficiency caused an increased ROS level via the NOX pathway and induced changes in the cell cycle through the JNK-FOXO4 pathway.

Results

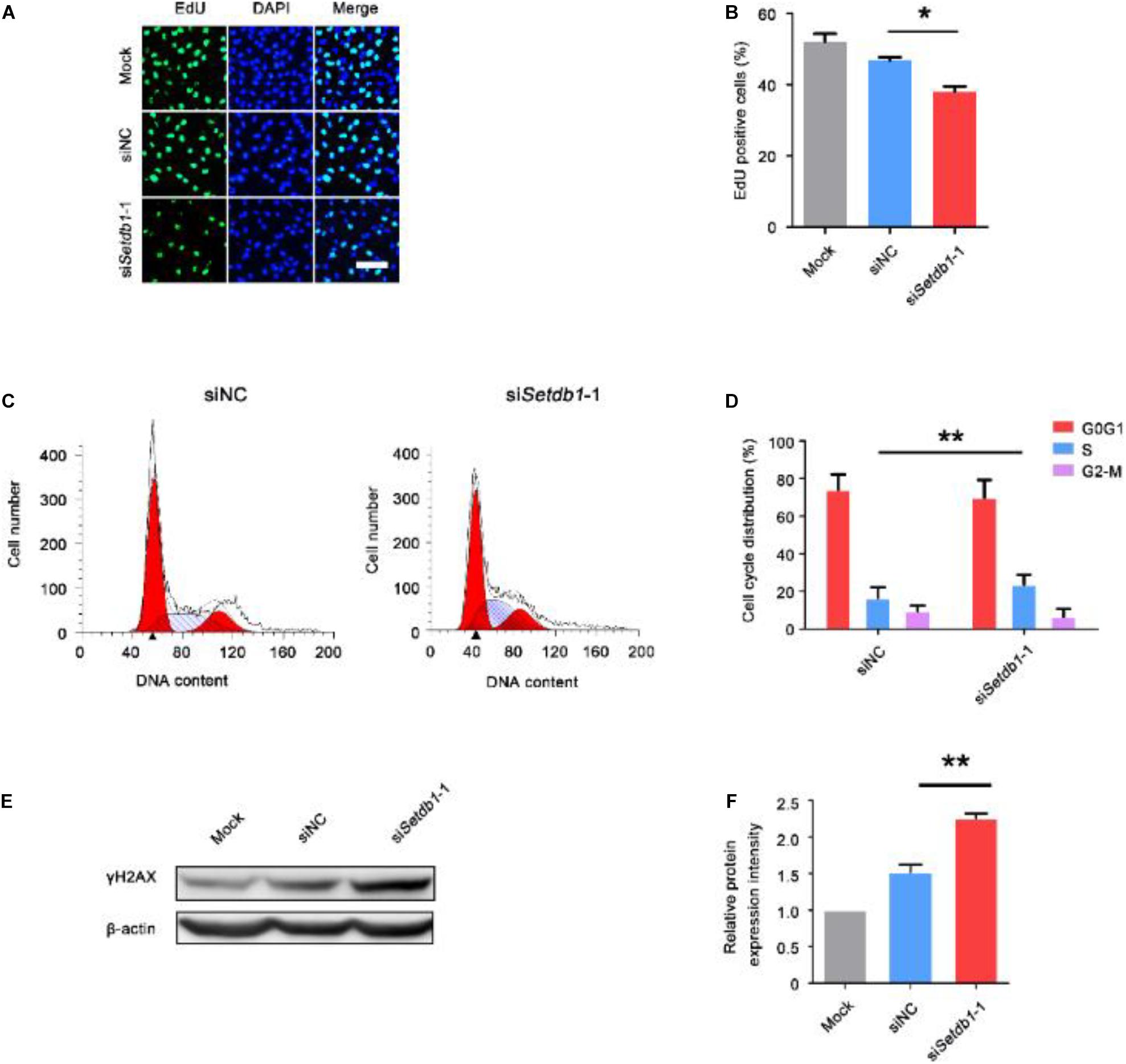

Knockdown of Setdb1 Impairs Proliferation and Induces Apoptosis in Spermatogonial Stem Cells

Using the siRNA oligonucleotides of Setdb1, we efficiently downregulated Setdb1 mRNA expression by approximately 70% (Supplementary Figure S1A). Western blotting analysis confirmed a significant decrease of SETDB1 at protein level after 48 h transfection (Supplementary Figures S1B,C). As shown in Figures 1A,B, the proliferation rate reduced in Setdb1-KD cells compared with the control group (Figures 1A,B). Flow cytometry analysis further confirmed that higher ratio of S phase cells in Setdb1 KD than that of the control at 36 h post transfection (Figures 1C,D). Meanwhile, Setdb1 depletion induced apoptosis at 48 h post transfection (Supplementary Figures S1D,E). Similar to the previous report, Setdb1 KD caused an increase of double-strand DNA breaks (Figures 1E,F) (Supplementary Figures S1F,G) (Kim et al., 2016). Interestingly, overexpression of Setdb1 had no effect on cell survival (Supplementary Figures S1H,J). These observations confirm that SETDB1 is required for the maintenance of SSCs.

Figure 1. Knockdown of Setdb1 impairs SSC proliferation. (A, B) The EdU incorporation assay showing the proliferation capability of SSCs after transfection with siRNA for 36 h. (C,D) Analysis of the cell cycle by flow cytometry after transfection with Setdb1 siRNA or control siRNA for 36 h (C) and the ratios of cells in each phase of the cell cycle (D). (E,F) Expression of γH2AX in SSCs shown by Western blot (E). γH2AX intensity analysis was calculated by ImageJ (F). Data are presented as the mean ± SEM of three independent experiments. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01. Bar = 50 μm.

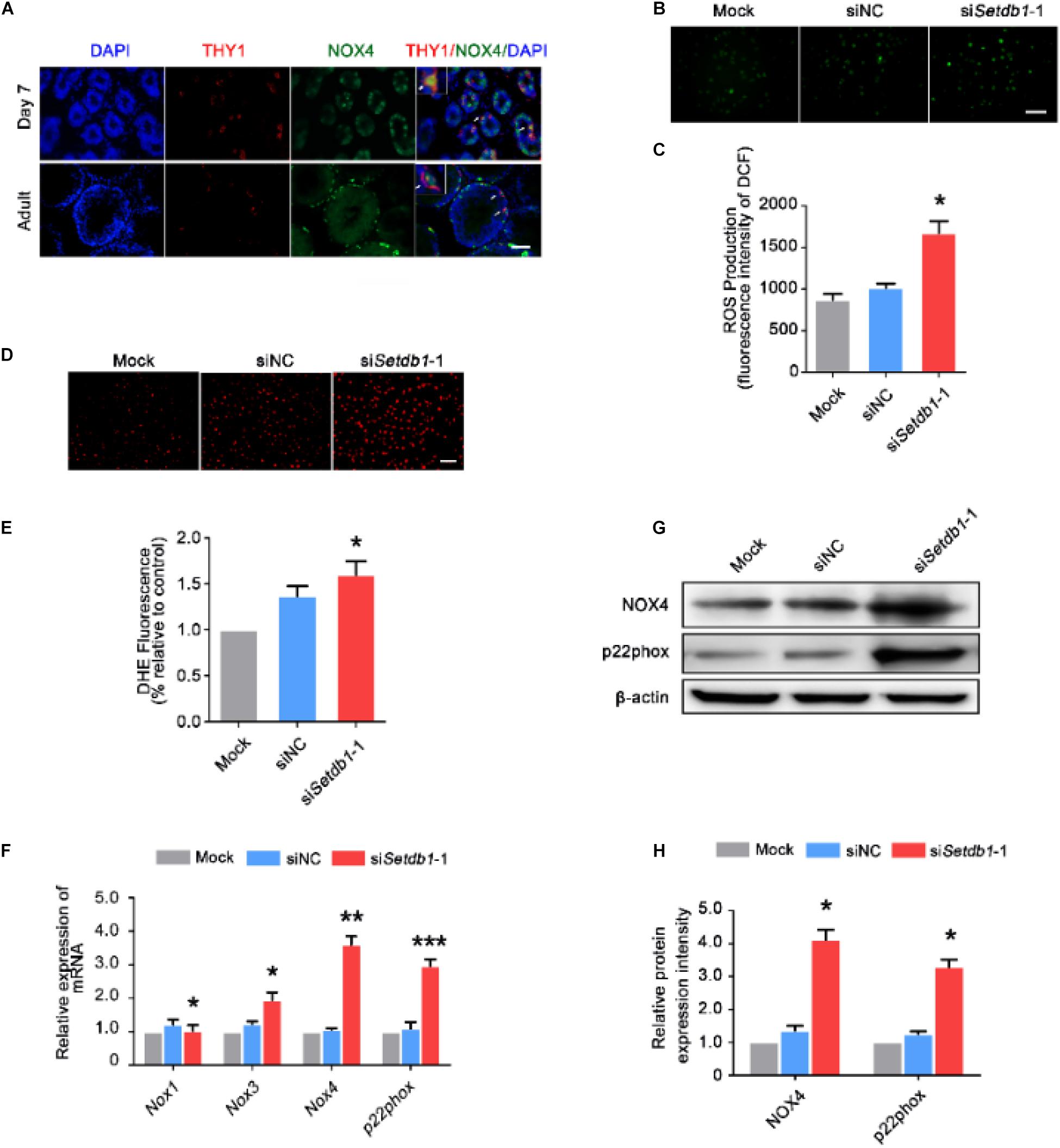

Suppression of Setdb1 Induces ROS Accumulation and NOX Expression

To clarify the expression of NOX4 in male germ cells, we carried out double-immunohistochemistry staining of testes tissue from 7-day-old and adult mice. NOX4 was co-localized with THY1 (SSC/undifferentiated spermatogonia marker) (Figure 2A). Intracellular ROS levels were detected by DCFH-DA and DHE staining. Setdb1 KD increased the level of total intracellular ROS (Figures 2B,E; Supplementary Figure S2). To test the potential roles of SETDB1 in mediating intracellular ROS homeostasis through NADPH oxidase, we detected NOX expression. Setdb1 KD caused an increase of expression of Nox3, Nox4, and p22phox (NOX4 regulatory subunits) (Figure 2F). Western blot assay showed that the level of total NOX4 and p22phox were upregulated (Figure 2G,H). These data suggest that Setdb1 KD resulted in ROS accumulation possibly by NOX expression in SSCs.

Figure 2. Suppression of SETDB1 induces ROS accumulation and the expression of NADPH oxidase. (A) Immunohistochemical analysis of NOX4 and THY1 (an SSC marker) in the testes. (B,C) Representative images of DCFH-DA evaluation for ROS production (B). DCFH-DA method was used to analyze ROS level after Setdb1 knockdown (n = 3) (C). (D,E) Representative images of dihydroethidium fluorescence staining that evaluation for ROS production (D). Quantitative analysis of DHE relative intensity (n = 3) (E). (F) The mRNA expression of Nox1, Nox3, Nox4, and p22phox upon Setdb1 knockdown. (G) The protein expression of NOX4 and p22phox measured by Western blot analysis. β-actin is used as loading control. (H) The protein expression of NOX4 and p22phox were quantitative by ImageJ. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM of three independent experiments. *P < 0.05. Bar = 100 μm.

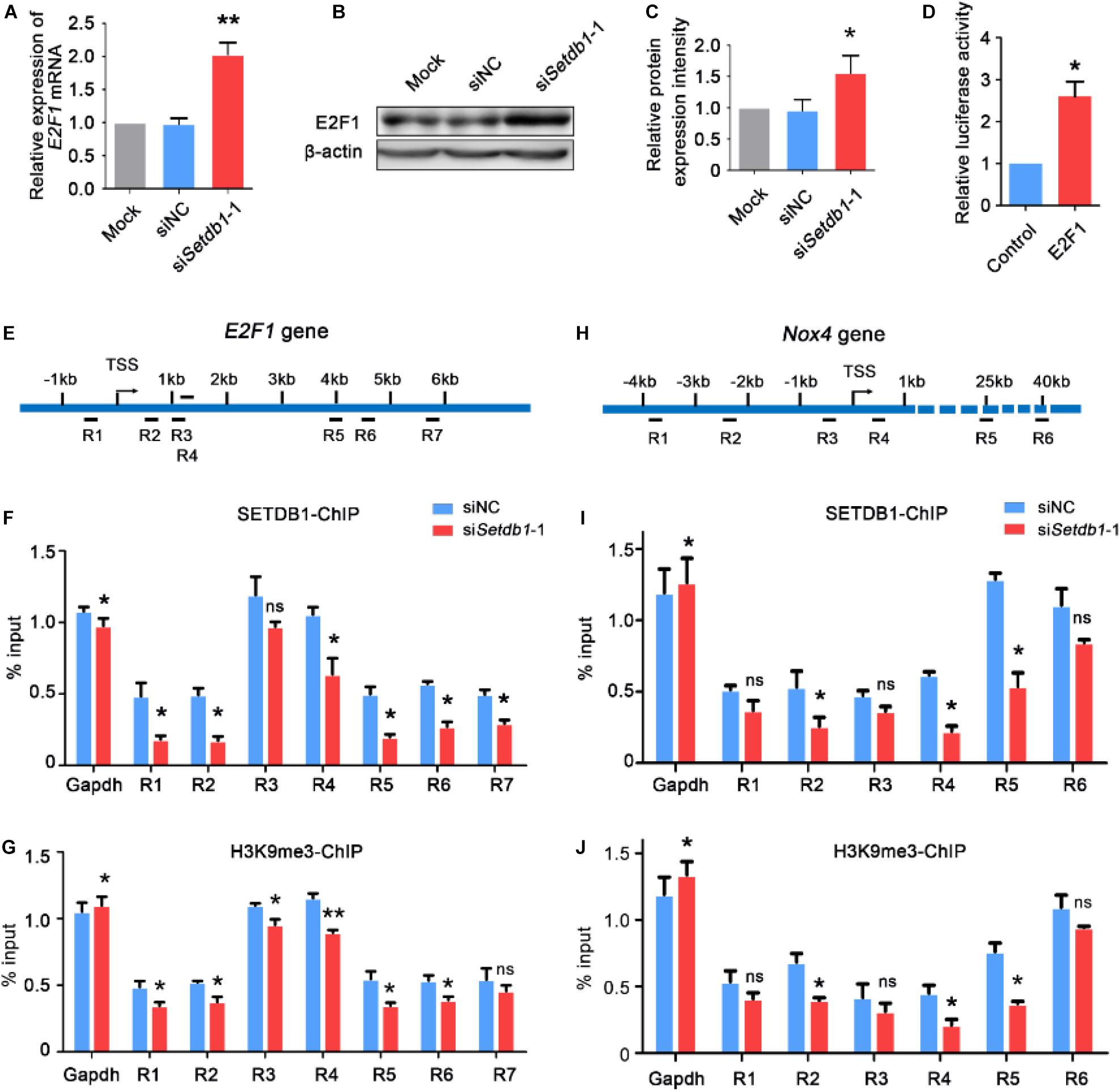

SETDB1 Activates Nox4 Expression via Regulating E2F Transcription Factor 1 (E2F1)

Western blotting and RT-qPCR assay showed that knockdown of Setdb1 led to an increase of E2F1 expression at both mRNA and protein levels (Figures 3A,C). In order to determine whether E2F1 regulates the activity of Nox4 promoter, the vector of luciferase containing Nox4 promotor were co-transfected with E2F1 overexpression vector or empty vector control. As shown in Figure 3D, luciferase reporter assay showed that E2F1 overexpression significantly increased the luciferase activity compared with that in the empty control group. Hence, E2F1 modulated the activity of Nox4 promoter (Figure 3D). Since Setdb1 KD caused the upregulation of E2F1 and NOX4, we test whether E2F1 and Nox4 were repressed by SETDB1-mediated histone modification at their promoter region through H3K9me3 (Supplementary Figure S3). Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) followed by a quantitative real-time PCR (ChIP-qPCR) assay was performed to exam the tentative binding sites of SETDB1 in the promoters of E2F1 and Nox4 (Figures 3E,H). We found that the enrichment of SETDB1 and H3K9me3 in the E2F1 promoter region were only 0.3–1.3% (Figures 3F,G) at these loci. ChIP-qPCR analysis confirmed that there is little enrichment of SETDB1 and H3K9me in the Nox4 promoter region (Figure 3I,J), suggesting that the regulation of SETDB1 on Nox4 expression is independent of H3K9me3.

Figure 3. Setdb1 deficiency in SSCs reduces the enrichment of H3K9me3 at the E2F1 and Nox4 transcriptional start site and increases E2F1 and Nox4 expression. (A) RT-qPCR was performed for detecting E2F1 expression. (B,C) Western blot analysis of E2F1 gene expression after transfection with Setdb1 siRNA (B). The protein expression of E2F1 were quantitative by ImageJ (C). (D) The luciferase assay showing the activity of Nox4 promoter fragment in HEK 293T cells. (E) Scheme of the E2F1 promoter used to analyze the enrichment of SETDB1 on different loci (R1–R7) of E2F1 genomic regions (R1: –549 –329 bp, R2: 496 716 bp, R3: 1167 1278 bp, R4: 1607 1714 bp, R5: 3997 4233 bp, R6: 4548 4707 bp, R7: 5838 5964 bp). (F,G) ChIP assays were carried out using anti-SETDB1 (F) and anti-H3K9me3 (G) antibodies with cell extracts after transfection with Setdb1 siRNA or control siRNA. (H) Scheme of the six different positions (R1–R6) of ChIP primers used to detect the enrichment of SETDB1 and H3K9me3 on Nox4 genomic regions. (R1: –3850 –3637 bp, R2: –2220 –2044 bp, R3: –431 –593 bp, R4: 513 667 bp, R5: 24861 24987 bp, R6: 40409 40512 bp). (I,J) ChIP assays were carried out using anti-SETDB1 (I) and anti-H3K9me3 (J) antibodies, followed by qPCR based on DNA samples. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM of three independent experiments. Ns, not significant. *P < 0.05.

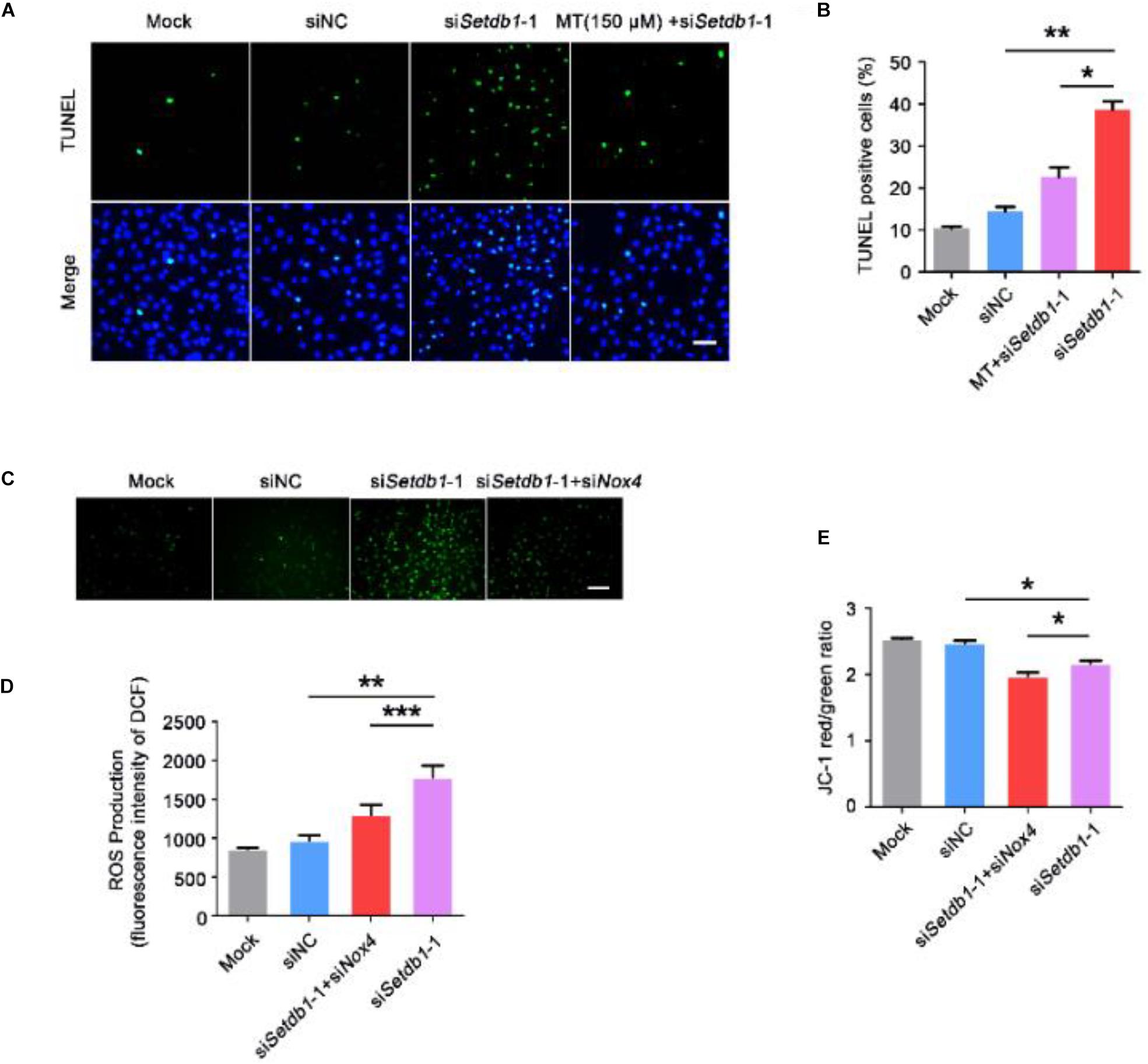

SETDB1 Regulates Intracellular ROS Homeostasis Through NOX4

To clarify whether Setdb1-KD induces apoptosis via the ROS pathway, we pretreated the cells with melatonin, a ROS scavenger, before Setdb1 knockdown (Tan et al., 2002; Schaefer et al., 2019). As shown in Figures 4A,B, addition of melatonin alleviated the apoptosis induced by Setdb1 KD (Figures 4A,B), confirming that Setdb1 KD induces apoptosis through the ROS pathway. We found that addition of melatonin reduced the expressions of Nox2 and Nox4 in SSCs, which are similar to preciously published results (Supplementary Figure S4; Najafi et al., 2019). These results indicate that abolition of ROS partially rescued the death phenotype.

Figure 4. Elimination of ROS helps to prevent the cell death induced by Setdb1 knockdown. (A,B) The TUNEL assay revealing apoptotic SSCs pretreated with ROS scavenger melatonin (MT) before transfection with Setdb1 siRNA or control siRNA. (C,D) Representative images of DCFH-DA evaluation for ROS production (C). DCFH-DA staining showing the generation of ROS after transfection with siRNA for 36 h (D). (E) Effects of Setdb1 knockdown on mitochondrial membrane potential. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM of three independent experiments. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01. Bar = 50 μm.

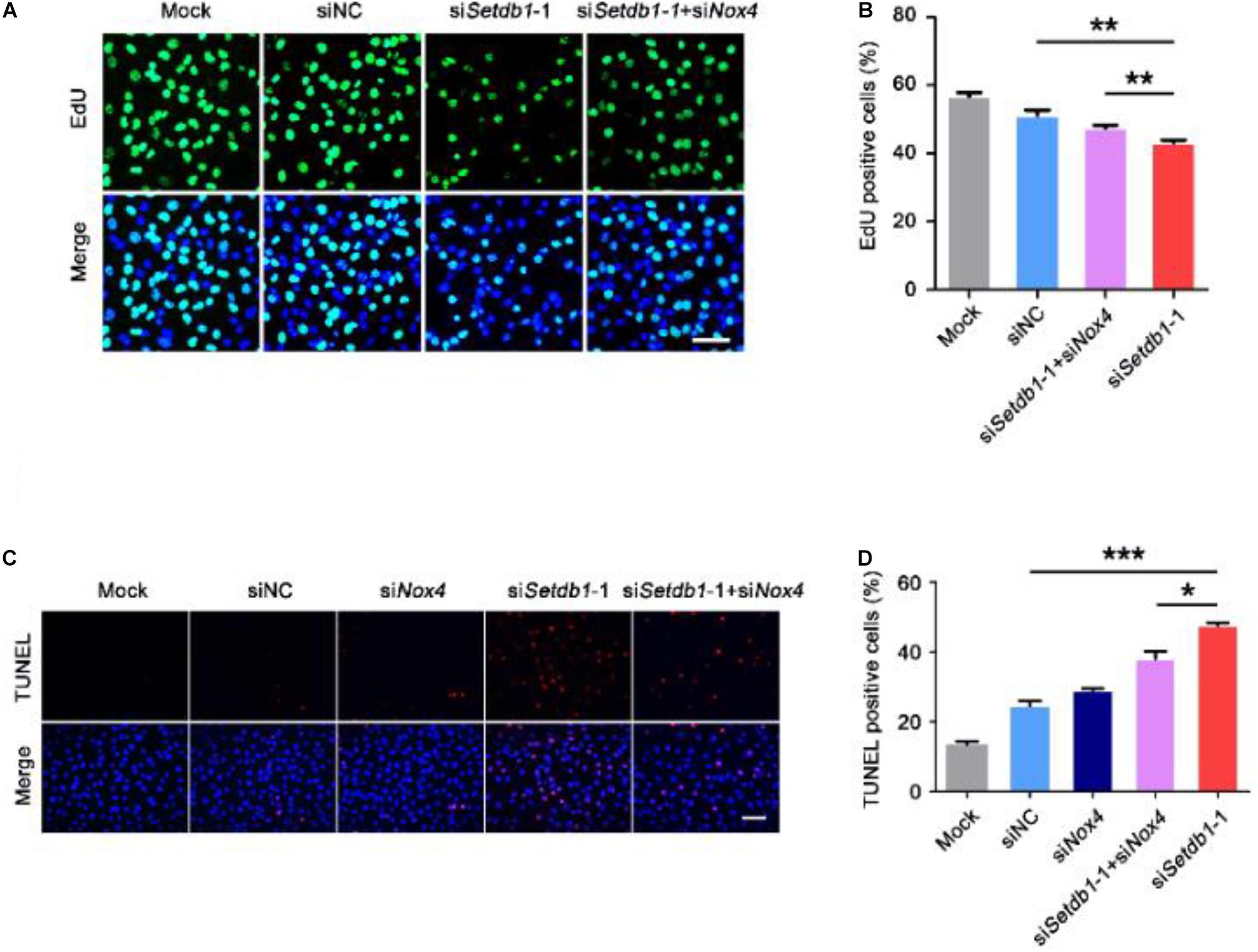

To test whether the ROS level is upregulated by NOX4, we co-transfected specific siRNA against Setdb1 and Nox4 and analyzed the knockdown efficiency (Supplementary Figure S5). As shown in Figures 4C,D, ROS were decreased in cells co-transfected with both siRNAs against Setdb1 and Nox4 compared with the group that was solely transfected with the Setdb1 siRNA (Figures 4C,D). To address whether Setdb1 KD led to mitochondrial dysfunction by upregulating NOX4, both siRNAs of Setdb1 and Nox4 were introduced to the cells simultaneously. JC-1 assay showed that mitochondrial dysfunction was reduced in cells co-transfected with both siRNAs of Setdb1 and Nox4 compared with the group only transfected with the Setdb1 siRNA (Figure 4E). Subsequently, we detected the role of NOX4 in apoptosis and cell proliferation. As shown in Figures 5A,B, Nox4 KD could partly alleviate the phenotype induced by Setdb1 KD (Figures 5A,B). In addition, TUNEL positive cells were reduced in cells co-transfected with both Setdb1 siRNA and Nox4 siRNA compared with the group transfected with the Setdb1 siRNA (Figures 5C,D). Based on these data, we conclude SETDB1 regulates intracellular ROS homeostasis through NOX4.

Figure 5. SETDB1 regulates intracellular ROS homeostasis through NADPH oxidase 4. (A,B) The EdU incorporation assay showing the proliferation capability of SSCs. (C,D) The TUNEL assay showing apoptotic SSCs. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM of three independent experiments. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.005. Bar = 100 μm.

Setdb1 Knockdown Activates p38/JNK-FOXO4 Pathway

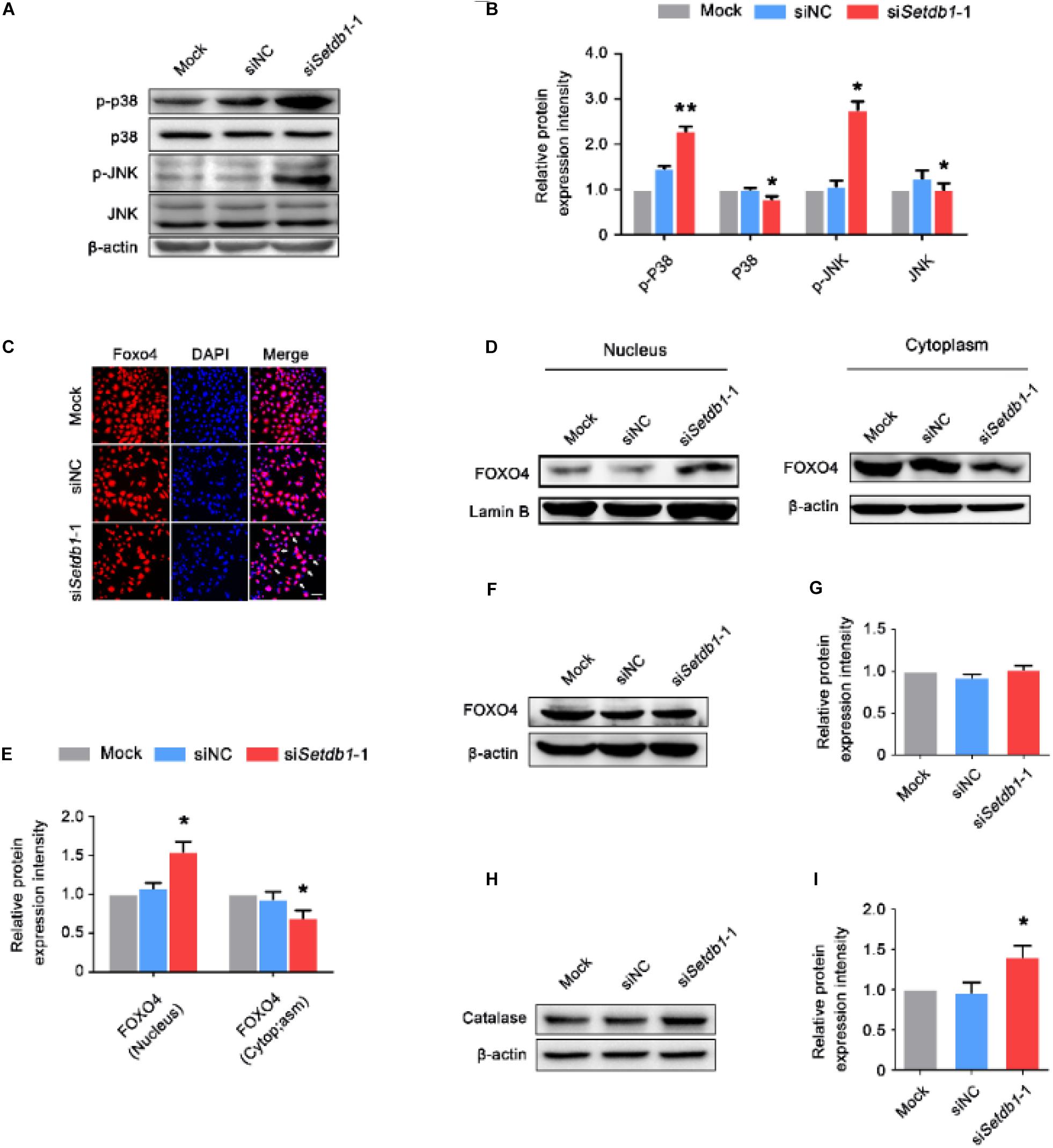

We examined whether SETDB1 mediated the phosphorylation of p38 MAPK and c-jun N-terminal kinase (JNK). We found that Setdb1 KD led to the activation of p38 and JNK signaling in SSCs (Figures 6A,B).

Figure 6. Setdb1 knockdown activates p38/JNK-FOXO4 pathway. (A, B) Western blot analysis showing the phosphorylation of p38 MAPK and JNK after Setdb1 depletion (A). The expression of p-P38, P38, p-JNK, and JNK proteins were calculated by Image J (B). (C) Immunofluorescence staining of FOXO4 in SSCs. FOXO4: red, DAPI: blue. (D, E) Immunoblotting for FOXO4 in cytoplasm and nuclei after downregulation of Setdb1 by specific siRNA (D). Intensity analysis of FOXO4 expression in the cell components was quantitative by ImageJ (E). β-actin and Laminin B are used as loading controls. (F, G) Western blot analysis for FOXO4 after transfection with Setdb1 siRNA for 48 h (F). Quantitative result was illustrated for FOXO4 (G). (H, I) Western blot analysis of Catalase in SSCs transfected with Setdb1 siRNA for 48 h (H). The protein expression of Catalase was calculated by ImageJ (I). Data are presented as the mean ± SEM of three independent experiments. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01. Bar = 100 μm.

We further investigated whether Setdb1-KD induced activation and translocation of FOXO4. The immunofluorescence assay showed Setdb1 KD resulted in FOXO4 translocation (Figure 6C). To further confirm the nuclear translocation of FOXO4 after Setdb1 KD, we extracted protein of the nucleus and cytoplasm. The western blot assay confirmed that FOXO4 translocated from the cytoplasm to the nucleus (Figures 6D, E). However, the expression of FOXO4 almost did not change at 48 h after Setdb1 KD (Figures 6F,G). Setdb1 KD upregulated the expression of the target gene encoded Catalase (Figures 6H,I). These results suggest that Setdb1 KD activates the p38/JNK-FOXO4 pathway.

Discussion

SETDB1 catalyzes H3K9me3, which is a repressive marker (Mozzetta et al., 2015). In the present study, we found that SETDB1 repressed expression of Nox4 and E2F1 and mediated ROS levels.

NOX consumes oxygen to generate O2– using NADPH as an electron donor, and the O2– subsequently forms H2O2 (Katsuyama et al., 2012; Bigarella et al., 2014). Previous studies have shown that ROS generated by NOX enhanced growth factor signaling and acts as anti-microbial molecules (Nathan and Cunningham-Bussel, 2013). Excessive ROS production induces cellular injury and lipid peroxidation (Su et al., 2019). In this study, we found that Setdb1 KD induced accumulation of ROS and upregulation of Nox3, Nox4, p22phox, and E2F1. Importantly, melatonin alleviated the apoptosis in Setdb1-KD group. Co-transfecting with siRNAs of Nox4 and Setdb1 simultaneously resulted in the decrease of ROS and increase of mitochondrial membrane potential compared with the Setdb1 depleted cells. Furthermore, melatonin reduced the expression of Nox2 and Nox4, which is consistent with the previous report (Najafi et al., 2019). Therefore, melatonin alleviated Setdb1-KD induced SSC apoptosis, probably by down-regulating Nox2 and Nox4. The excess ROS was generated from NOX4 and was responsible for the apoptosis in Setdb1-KD cells. In this study, we also found that Setdb1 KD led to increase of Nox3. Together, SETDB1 mediates ROS homeostasis and likely keeps ROS below a threshold level via NADPH oxidase.

It has been reported that ROS generated by NOX4 was associated with DNA damage (Weyemi et al., 2012), which was consistent with the present findings on SSCs. Except for double-strand DNA breaks, ROS activates the signal-transducing molecules including JNK, p38, and FOXO4 (Ma et al., 2002; Essers et al., 2004; Hua et al., 2017; Zheng et al., 2017). In mammals, the FOXO family consists of four members (FOXO1, FOXO3, FOXO4, and FOXO6) (Eijkelenboom and Burgering, 2013). These FOXO transcription factors regulate multiple cellular pathways, including apoptosis, inflammation, proliferation, oxidative stress resistance, and aging (Henderson and Johnson, 2001; Lin et al., 2001; Tuteja and Kaestner, 2007a, b; Zanella et al., 2010; Genin et al., 2014; Webb and Brunet, 2014; Murtaza et al., 2017; Jiramongkol and Lam, 2020). Meanwhile, FOXO nuclear translocation triggers apoptosis by inducing the expression of death genes, such as the FasL, and thereby participates actively in the process of apoptosis (Brunet et al., 2004). In this study, knockdown of Setdb1 activated the ROS-JNK signaling pathway and FOXO4 that was translocated into the nuclei, which led to an increase of expression of the Catalase gene (FOXO4 target gene) that encodes an anti-oxidant enzyme (Nandi et al., 2019). Taken together, we propose that Setdb1 KD activates ROS downstream signaling pathways, which partially contributes to the apoptotic phenotype in SSCs.

SETDB1 is involved in heterochromatin formation and transcription silencing via histone H3 methyltransferase activity (Zhu et al., 2020). In this study, we found that Setdb1 KD led to the upregulation of Nox4 and E2F1. ChIP-qPCR showed that 0.3–1.4% of input for SETDB1 and H3K9me3 at the loci of the E2F1 and Nox4 promoters, indicating that SETDB1 does not target E2F1 and Nox4 promoters. Recent studies revealed that Setdb1 KD resulted in the activation of endogenous retroviruses (ERVs) and the long terminal repeat (LTR) and led to dysregulation expression of neighboring genes (Tan et al., 2012). Thus, SETDB1 may regulate the expression of Nox4 and E2F1 due to silencing of cis-regulatory elements or retrotransposons in SSCs.

NOX4 was involved in various physiological processes such as apoptosis and differentiation in various cell types (Pedruzzi et al., 2004; McKallip et al., 2006; Carmona-Cuenca et al., 2008; Caja et al., 2009). It was reported that SETDB1 was recruited to the E2F1 promoter and co-operated with Alien complex to regulate the expression of E2F1 (Hong et al., 2011). Meanwhile, E2F1 positively regulates the transcription of Nox4 in vascular smooth muscle cells (Zhang et al., 2008). In this study, the expression of E2F1 and NOX4 were elevated in Setdb1-KD group. The expression of E2F1 was upregulated in Setdb1-KD cells, which in turn lead to upregulation of NOX4.

The role of SETDB1 has been explored extensively in the development of male germ lines (An et al., 2014; Liu et al., 2015, 2017; Hirota et al., 2018; Mochizuki et al., 2018). SETDB1 is recruited to repress ERVs transcription via H3K9me3 in primordial germ cells (Liu et al., 2015), and suppresses the expression of Dppa2, Otx2, and Utf1 during PGC determination (Mochizuki et al., 2018). Setdb1 knockout disrupts spermatogenesis and expression of meiosis-related genes (Hirota et al., 2018). Therefore, SETDB1 regulates different clusters of genes in the development of male germ cells. It would be interesting to further elucidate the mechanisms of recruitment in SETDB1 to different genes.

In conclusion, SETDB1 regulates the expression of E2F1 and Nox4. Setdb1 depletion causes the derepression of E2F1 and upregulation of Nox4. On the other hand, NOX4 was upregulated by E2F1 dysregulation. Thus, NOX4 contributes to ROS generation and activates ROS downstream signaling pathways. Meanwhile, excessive amounts of ROS induces cell cycle arrest and apoptosis in SSCs. This study will provide a new perspective on SETDB1 function and understanding of male infertility.

Materials and Methods

Cell Culture and Transfection

C18-4 cell line was obtained from Dr. Zuping He at Shanghai Jiao Tong University, China. The cell line was established from mouse type A spermatogonia from 6-day-old mice (Hofmann et al., 2005). C18-4 cells were maintained in Dulbecco modified Eagle medium (DMEM)/F12 (Hyclone, Logan, UT, United States) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (BI, Israel), 100 U/ml penicillin and streptomycin (Gibco), 100 mM non-essential amino acids (Gibco), and 2 mM L-glutamine (Gibco) at 37°C and 5% CO2. The 293T cell line was cultured in DMEM/Basic medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 100 U/ml penicillin and streptomycin, 100 mM non-essential amino acids, and 2 mM L-glutamine at 37°C and 5% CO2.

A pair of Setdb1 small interfering RNAs (siRNAs), Setdb1-1 and Setdb1-2, were ordered from GenePharma (Shanghai, China). Sequences of mouse Setdb1 siRNA were as follows: 5′-CCAACC UGUUUGUCCAGAAUGUGUU-3′ (Setdb1-1), 5′-UCAAGUUUGGCAUCAAUGAUGUAGC-3′ (Setdb1-2), 5′-UU CUCCGAACGU GUCACGUTT-3′ (Scramble). The sequence of mouse Nox4 siRNA was as follows: 5′-GTAGGAGAC TGGACAGAAC-3′. The cells were transfected with siRNAs using Lipofectamine 2000 Transfection Reagent (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Reverse Transcription-Quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction (RT-qPCR)

Total RNA was extracted using RNAiso Plus reagent (TaKaRa, Dalian, China). RT-qPCR was performed as described previously using the primers listed in Supplementary Table S1 (Chen et al., 2017).

Western Blot

The cells were transfected with Setdb1 siRNA for 48 h. Approximately 30 μg protein was separated by 8–12% SDS-PAGE and transferred to PVDF membranes (Millipore). The membranes were probed using the following primary antibodies: NOX4 (1:500; NB110-58849; Novus), beta-Actin (1:2000; CW0096; CWBIO), SETDB1 (1:1000; 11231-1-AP; Proteintech), E2F1 (1:500; sc-193; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), FOXO4 (1:500; sc-5221; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), Lamin B (1:500; sc-6217; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), JNK (1:500; sc-7345; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), p-JNK (1:400; WL01813; WanleiBio), γH2AX (1:000; 2577; Cell signaling technology), p38 (1:500; sc-7972; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), and p-P38 (1:500; sc-17852-R; Santa Cruz Biotechnology). All were used as the manufacturer’s recommendation. The secondary antibodies were horse radish peroxidase-linked anti-mouse, anti-rabbit, or anti-goat IgG for 2 h at room temperature. The membranes were visualized on a Bio-Rad Chemidoc XRS using a Western Bright ECL Kit (Bio-Rad, Berkeley, CA, United States).

ROS Measurement

Intracellular ROS was determined using the 2′, 7′-dichlorofluorescein diacetate (DCFH-DA, Beyotime) and Dihydroethidium (DHE, Beyotime) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Cells were incubated with 10 μM 2′, 7′-dichlorofluorescein diacetate or dihydroethidium at 37°C for 30 min. Subsequently, the fluorescence signals of the cells were observed using a multi-detection microplate reader. The excitation/emission of DCFH-DA is 488/525 nm, and the excitation/emission of DHE staining are 370/420 and 300/610 nm.

Cell Cycle Assay

The cell cycle analysis was performed with Flow cytometry. The cells were harvested at 36 h post transfection of Setdb1 siRNA or control siRNA. After being fixed in 70% cold ethanol, the cells were incubated with RNase and finally stained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI, Bioworld). DNA content was analyzed by Flow cytometry (BD FACSAriaTM III, United States). The data were analyzed with ModFit LT 5.0.

TUNEL Staining

Apoptotic cells were detected with TUNEL BrightGreen or BrightRed Apoptosis Detection Kit (Vazyme, Nanjing, China) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The cells were seeded on 96-well plates and transfected with siRNA. After washing with PBS, the cells were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) for 30 min. Then the cells were treated with proteinase K (20 mg/ml) for 5 min at room temperature and incubated in TUNEL reaction mixture at 37°C for 1 h in darkness. The nuclei were counterstained with DAPI (Bioworld). The cells were observed under a fluorescence microscope (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan).

Immunocytochemistry

The cells were seeded onto a 96-well plate and transfected with siRNA for 48 h. The cells were fixed with 4% PFA for 30 min, permeabilized in 0.5% TritonX-100 for 10 min, and blocked in 3% BSA for 2 h. The cells were incubated with primary antibody for FOXO4 (sc-5221; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and γH2AX (2577; Cell signaling technology) overnight at 4°C. After washing with PBS, the cells were incubated for 1 h with secondary antibody, followed by incubation with DAPI.

Immunohistochemistry

Testes from 6-d- and 3-m-old C57BL/6J mice were used for histologic analyses. In brief, the slides (5 μm thick) were blocked with 10% donkey serum for 2 h to block non-specific reactions. The following primary antibodies were used: anti-NOX4 (NB110-58849; Novus) and anti-THY1 (sc-9163, Santa Cruz Biotechnology). The following secondary antibodies were used: Alexa 594-conjugated donkey anti-mouse IgG and Alexa 488-conjugated donkey anti-rabbit IgG (1: 400, Invitrogen). Photomicrographs were captured under a Nikon i90 microscope (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan).

Plasmid Construction

The 2 kb region of the Nox4 gene promoter was amplified by polymerase chain reaction (PCR). Subsequently, PCR product was purified using AxyPrepTM PCR Clean-Up Kit (Axygen, CA, United States). The resulting fragments digested by KpnI/BgI II were inserted into the KpnI/BgI II restriction sites of digested pGL3-Basic vector. The ligated mixtures were transformed into competent cells of Escherichia Coli DH5α using the heat shock method.

Transfections and Luciferase Assays

The 293T cells were transiently transfected using TurbofectTM (Thermo Fisher Scientific) reagent according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The cells were seeded onto 24-well plates, and transfected with 1 μg total plasmid containing 0.5 μg pGL3-basic-Nox4, 0.5 μg pCDNA3.1-E2F1, and 0.2 μg pRL-CMV, which were transfected as reference plasmid. The transfected cells were cultured for 48 h and analyzed using a dual-luciferase reporter assay system kit (Promega, Madison, WI, United States) according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation-qPCR

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation analysis was performed as previously described using EZ-Magna ChIP A/G (Millipore) (Liu et al., 2017). In brief, the cells were fixed with 1% formaldehyde and lysed in lysis buffer. After the sonication the cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with SETDB1 (11231-1-AP; Proteintech), H3K9me3 (07-442, millipore), or normal IgG (millipore) antibodies. IgG is as a background of the IP. The purified DNA was analyzed by RT-qPCR. The primer was designed by published H3K9me3 ChIP-seq data in mouse undifferentiated spermatogonia cells (Liu et al., 2019). Then, ChIP-qPCR primers were designed around the transcription initiation site, and the size of the product was about 200 bp (Asp, 2018). Finally, the statistical calculation methodology was performed as described previously (Nelson et al., 2006). Briefly, the ChIP-qPCR data output from RT-qPCR software was in the form of Cycle threshold (Ct) values. The relative occupancy of the SETDB1 and H3K9me3 at a locus is measured by the equation 2^(Ctmock-Ctspecific), where Ctmock and Ctspecific are mean threshold cycles of RT-qPCR. Primers were listed in Supplementary Table S2.

Statistics

The statistical analysis of the differences between two groups was performed by Student’s t-test. P < 0.05 indicated statistical significance.

Data Availability Statement

All data used to support the findings of this study are included in the article.

Author Contributions

XL and XC: conceptualization and writing – original draft preparation. XL, YL, and PZ: methodology. XL: data curation. YZ and WZ: writing – review and editing and funding acquisition. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 31772605) to WZ, the Natural Science Foundation of Shaanxi Province, China (Grant No. 2019JQ-430), Young Talent Fund of University Association for Science and Technology in Shaanxi, China (Grant No. 20180204), China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (Grant No. 2018M641032), and a startup fund from Northwest A&F University (Grant No. 2452018037) to YZ.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Zuping He for his generous gift of mouse progenitor spermatogonia cell line C18-4 cells and our laboratory members for technical support.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fgene.2020.00997/full#supplementary-material

References

Ago, T., Kuroda, J., Pain, J., Fu, C., Li, H., and Sadoshima, J. (2010). Upregulation of Nox4 by hypertrophic stimuli promotes apoptosis and mitochondrial dysfunction in cardiac myocytes. Circ. Res. 106, 1253–1264. doi: 10.1161/circresaha.109.213116

An, J., Zhang, X., Qin, J., Wan, Y., Hu, Y., Liu, T., et al. (2014). The histone methyltransferase ESET is required for the survival of spermatogonial stem/progenitor cells in mice. Cell Death Dis. 5:e1196. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2014.171

Asp, P. (2018). How to combine ChIP with qPCR. Methods Mol. Biol. 1689, 29–42. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-7380-4_3

Bigarella, C. L., Liang, R., and Ghaffari, S. (2014). Stem cells and the impact of ROS signaling. Development 141, 4206–4218. doi: 10.1242/dev.107086

Brunet, A., Sweeney, L. B., Sturgill, J. F., Chua, K. F., Greer, P. L., Lin, Y., et al. (2004). Stress-dependent regulation of FOXO transcription factors by the SIRT1 deacetylase. Science 303, 2011–2015. doi: 10.1126/science.1094637

Bui, A. D., Sharma, R., Henkel, R., and Agarwal, A. (2018). Reactive oxygen species impact on sperm DNA and its role in male infertility. Andrologia 50:e13012. doi: 10.1111/and.13012

Caja, L., Sancho, P., Bertran, E., Iglesias-Serret, D., Gil, J., and Fabregat, I. (2009). Overactivation of the MEK/ERK pathway in liver tumor cells confers resistance to TGF-β-induced cell death through impairing up-regulation of the NADPH oxidase NOX4. Cancer Res. 69, 7595–7602. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.can-09-1482

Carmona-Cuenca, I., Roncero, C., Sancho, P., Caja, L., Fausto, N., Fernandez, M., et al. (2008). Upregulation of the NADPH oxidase NOX4 by TGF-beta in hepatocytes is required for its pro-apoptotic activity. J. Hepatol. 49, 965–976. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2008.07.021

Chen, X., Che, D., Zhang, P., Li, X., Yuan, Q., Liu, T., et al. (2017). Profiling of miRNAs in porcine germ cells during spermatogenesis. Reproduction 154, 789–798. doi: 10.1530/rep-17-0441

Eijkelenboom, A., and Burgering, B. M. (2013). FOXOs: signalling integrators for homeostasis maintenance. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 14, 83–97. doi: 10.1038/nrm3507

Essers, M. A., Weijzen, S., De Vries-Smits, A. M., Saarloos, I., De Ruiter, N. D., Bos, J. L., et al. (2004). FOXO transcription factor activation by oxidative stress mediated by the small GTPase Ral and JNK. EMBO J. 23, 4802–4812. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600476

Genin, E. C., Caron, N., Vandenbosch, R., Nguyen, L., and Malgrange, B. (2014). Concise review: forkhead pathway in the control of adult neurogenesis. Stem Cells 32, 1398–1407. doi: 10.1002/stem.1673

Henderson, S. T., and Johnson, T. E. (2001). daf-16 integrates developmental and environmental inputs to mediate aging in the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Curr. Biol. 11, 1975–1980. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(01)00594-2

Hirota, T., Blakeley, P., Sangrithi, M. N., Mahadevaiah, S. K., Encheva, V., Snijders, A. P., et al. (2018). SETDB1 links the meiotic DNA damage response to sex chromosome silencing in mice. Dev. Cell 47:e646.

Hofmann, M. C., Braydich-Stolle, L., Dettin, L., Johnson, E., and Dym, M. (2005). Immortalization of mouse germ line stem cells. Stem Cells 23, 200–210. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2003-0036

Hong, W., Li, J., Wang, B., Chen, L., Niu, W., Yao, Z., et al. (2011). Epigenetic involvement of Alien/ESET complex in thyroid hormone-mediated repression of E2F1 gene expression and cell proliferation. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 415, 650–655. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2011.10.130

Hua, X., Chi, W., Su, L., Li, J., Zhang, Z., and Yuan, X. (2017). ROS-induced oxidative injury involved in pathogenesis of fungal keratitis via p38 MAPK activation. Sci. Rep. 7:10421.

Ito, K., Hirao, A., Arai, F., Takubo, K., Matsuoka, S., Miyamoto, K., et al. (2006). Reactive oxygen species act through p38 MAPK to limit the lifespan of hematopoietic stem cells. Nat. Med. 12, 446–451. doi: 10.1038/nm1388

Jiramongkol, Y., and Lam, E. W. (2020). FOXO transcription factor family in cancer and metastasis. Cancer Metast. Rev. 39, 681–709. doi: 10.1007/s10555-020-09883-w

Kanatsu-Shinohara, M., and Shinohara, T. (2013). Spermatogonial stem cell self-renewal and development. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 29, 163–187. doi: 10.1146/annurev-cellbio-101512-122353

Katsuyama, M., Matsuno, K., and Yabe-Nishimura, C. (2012). Physiological roles of NOX/NADPH oxidase, the superoxide-generating enzyme. J. Clin. Biochem. Nutr. 50, 9–22. doi: 10.3164/jcbn.11-06sr

Kim, J., Zhao, H. B., Dan, J. M., Kim, S., Hardikar, S., Hollowell, D., et al. (2016). Maternal setdb1 is required for meiotic progression and preimplantation development in mouse. PLoS Genet. 12:e1005970. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1005970

Lambeth, J. D., and Neish, A. S. (2014). Nox enzymes and new thinking on reactive oxygen: a double-edged sword revisited. Annu. Rev. Pathol. 9, 119–145. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pathol-012513-104651

Lin, K., Hsin, H., Libina, N., and Kenyon, C. (2001). Regulation of the Caenorhabditis elegans longevity protein DAF-16 by insulin/IGF-1 and germline signaling. Nat. Genet. 28, 139–145. doi: 10.1038/88850

Liu, S., Brind’amour, J., Karimi, M. M., Shirane, K., Bogutz, A., Lefebvre, L., et al. (2015). Setdb1 is required for germline development and silencing of H3K9me3-marked endogenous retroviruses in primordial germ cells (vol 28, pg 2041, 2014). Genes Dev. 29, 108–108.

Liu, T. T., Chen, X. X., Li, T. J., Li, X. L., Lyu, Y. H., Fan, X. T., et al. (2017). Histone methyltransferase SETDB1 maintains survival of mouse spermatogonial stem/progenitor cells via PTEN/AKT/FOXO1 pathway. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Gene Regul. Mech. 1860, 1094–1102. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2017.08.009

Liu, Y., Zhang, Y., Yin, J., Gao, Y., Li, Y., Bai, D., et al. (2019). Distinct H3K9me3 and DNA methylation modifications during mouse spermatogenesis. J. Biol. Chem. 294, 18714–18725. doi: 10.1074/jbc.ra119.010496

Ma, X., Du, J., Nakashima, I., and Nagase, F. (2002). Menadione biphasically controls JNK-linked cell death in leukemia Jurkat T cells. Antioxid. Redox. Signal. 4, 371–378. doi: 10.1089/15230860260196173

McKallip, R. J., Jia, W., Schlomer, J., Warren, J. W., Nagarkatti, P. S., and Nagarkatti, M. (2006). Cannabidiol-induced apoptosis in human leukemia cells: a novel role of cannabidiol in the regulation of p22phox and Nox4 expression. Mol. Pharmacol. 70, 897–908. doi: 10.1124/mol.106.023937

McSwiggin, H. M., and O’Doherty, A. M. (2018). Epigenetic reprogramming during spermatogenesis and male factor infertility. Reproduction 156, R9–R21.

Mochizuki, K., Tandot, Y., Sekinaka, T., Otsuka, K., Hayashi, Y., Kobayashi, H., et al. (2018). SETDB1 is essential for mouse primordial germ cell fate determination by ensuring BMP signaling. Development 145:dev164160. doi: 10.1242/dev.164160

Morimoto, H., Iwata, K., Ogonuki, N., Inoue, K., Atsuo, O., Kanatsu-Shinohara, M., et al. (2013). ROS are required for mouse spermatogonial stem cell self-renewal. Cell Stem Cell 12, 774–786. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2013.04.001

Morimoto, H., Kanatsu-Shinohara, M., and Shinohara, T. (2015). ROS-generating oxidase Nox3 regulates the self-renewal of mouse spermatogonial stem cells. Biol. Reprod. 92:147.

Mozzetta, C., Boyarchuk, E., Pontis, J., and Ait-Si-Ali, S. (2015). Sound of silence: the properties and functions of repressive Lys methyltransferases. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 16, 499–513. doi: 10.1038/nrm4029

Murtaza, G., Khan, A. K., Rashid, R., Muneer, S., Hasan, S. M. F., and Chen, J. (2017). FOXO transcriptional factors and long-term living. Oxid. Med. Cell Longev. 2017:3494289.

Najafi, M., Shirazi, A., Motevaseli, E., Geraily, G., Amini, P., Tooli, L. F., et al. (2019). Melatonin modulates regulation of NOX2 and NOX4 following irradiation in the lung. Curr. Clin. Pharmacol. 14, 224–231. doi: 10.2174/1574884714666190502151733

Nandi, A., Yan, L. J., Jana, C. K., and Das, N. (2019). Role of catalase in oxidative stress- and age-associated degenerative diseases. Oxid. Med. Cell Longev. 2019:9613090.

Nathan, C., and Cunningham-Bussel, A. (2013). Beyond oxidative stress: an immunologist’s guide to reactive oxygen species. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 13, 349–361. doi: 10.1038/nri3423

Nelson, J. D., Denisenko, O., and Bomsztyk, K. (2006). Protocol for the fast chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) method. Nat. Protoc. 1, 179–185. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.27

Pedruzzi, E., Guichard, C., Ollivier, V., Driss, F., Fay, M., Prunet, C., et al. (2004). NAD(P)H oxidase Nox-4 mediates 7-ketocholesterol-induced endoplasmic reticulum stress and apoptosis in human aortic smooth muscle cells. Mol. Cell. Biol. 24, 10703–10717. doi: 10.1128/mcb.24.24.10703-10717.2004

Schaefer, M., Gebhard, M. M., and Gross, W. (2019). The effect of melatonin on hearts in ischemia/reperfusion experiments without and with HTK cardioplegia. Bioelectrochemistry 129, 170–178. doi: 10.1016/j.bioelechem.2019.05.017

Singh, S., Misiak, M., Beyer, C., and Arnold, S. (2009). Cytochrome c oxidase isoform IV-2 is involved in 3-nitropropionic acid-induced toxicity in Striatal astrocytes. Glia 57, 1480–1491. doi: 10.1002/glia.20864

Su, L. J., Zhang, J. H., Gomez, H., Murugan, R., Hong, X., Xu, D., et al. (2019). Reactive oxygen species-induced lipid peroxidation in apoptosis, autophagy, and ferroptosis. Oxid. Med. Cell Longev. 2019:5080843.

Tan, D. X., Reiter, R. J., Manchester, L. C., Yan, M. T., El-Sawi, M., Sainz, R. M., et al. (2002). Chemical and physical properties and potential mechanisms: melatonin as a broad spectrum antioxidant and free radical scavenger. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2, 181–197. doi: 10.2174/1568026023394443

Tan, S. L., Nishi, M., Ohtsuka, T., Matsui, T., Takemoto, K., Kamio-Miura, A., et al. (2012). Essential roles of the histone methyltransferase ESET in the epigenetic control of neural progenitor cells during development. Development 139, 3806–3816. doi: 10.1242/dev.082198

Tuteja, G., and Kaestner, K. H. (2007a). Forkhead transcription factors II. Cell 131:192. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.09.016

Urbich, C., Knau, A., Fichtlscherer, S., Walter, D. H., Bruhl, T., Potente, M., et al. (2005). FOXO-dependent expression of the proapoptotic protein Bim: pivotal role for apoptosis signaling in endothelial progenitor cells. FASEB J. 19, 974–976. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-2727fje

Wang, Y., Branicky, R., Noe, A., and Hekimi, S. (2018). Superoxide dismutases: dual roles in controlling ROS damage and regulating ROS signaling. J. Cell Biol. 217, 1915–1928. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201708007

Webb, A. E., and Brunet, A. (2014). FOXO transcription factors: key regulators of cellular quality control. Trends Biochem. Sci. 39, 159–169. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2014.02.003

Weyemi, U., Lagente-Chevallier, O., Boufraqech, M., Prenois, F., Courtin, F., Caillou, B., et al. (2012). ROS-generating NADPH oxidase NOX4 is a critical mediator in oncogenic H-Ras-induced DNA damage and subsequent senescence. Oncogene 31, 1117–1129. doi: 10.1038/onc.2011.327

Zanella, F., Link, W., and Carnero, A. (2010). Understanding FOXO, new views on old transcription factors. Curr. Cancer Drug Targets 10, 135–146. doi: 10.2174/156800910791054158

Zhang, L., Sheppard, O. R., Shah, A. M., and Brewer, A. C. (2008). Positive regulation of the NADPH oxidase NOX4 promoter in vascular smooth muscle cells by E2F. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 45, 679–685. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2008.05.019

Zheng, L., Wang, C., Luo, T., Lu, B., Ma, H., Zhou, Z., et al. (2017). JNK activation contributes to oxidative stress-induced parthanatos in glioma cells via increase of intracellular ROS production. Mol. Neurobiol. 54, 3492–3505. doi: 10.1007/s12035-016-9926-y

Keywords: SETDB1, H3K9me3, NOX4, ROS, spermatogonial stem cell

Citation: Li X, Chen X, Liu Y, Zhang P, Zheng Y and Zeng W (2020) The Histone Methyltransferase SETDB1 Modulates Survival of Spermatogonial Stem/Progenitor Cells Through NADPH Oxidase. Front. Genet. 11:997. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2020.00997

Received: 18 January 2020; Accepted: 05 August 2020;

Published: 02 October 2020.

Edited by:

Huiming Zhang, Shanghai Institutes for Biological Sciences (CAS), ChinaReviewed by:

Danny Chi Yeu Leung, Hong Kong University of Science and Technology, Hong KongMatthew Wong, Children’s Cancer Institute Australia, Australia

Copyright © 2020 Li, Chen, Liu, Zhang, Zheng and Zeng. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Yi Zheng, y.zheng@nwafu.edu.cn; Wenxian Zeng, zengwenxian2015@126.com

Xueliang Li

Xueliang Li Xiaoxu Chen

Xiaoxu Chen Wenxian Zeng

Wenxian Zeng