- 1U. S. Geological Survey, Wetland and Aquatic Research Center, Gainesville, FL, United States

- 2Department of Biology, University of Miami, Coral Gables, FL, United States

All basic processes of ecological populations involve decisions; when and where to move, when and what to eat, and whether to fight or flee. Yet decisions and the underlying principles of decision-making have been difficult to integrate into the classical population-level models of ecology. Certainly, there is a long history of modeling individuals' searching behavior, diet selection, or conflict dynamics within social interactions. When all the individuals are given certain simple rules to govern their decision-making processes, the resultant population–level models have yielded important generalizations and theory. But it is also recognized that such models do not represent the way real individuals decide on actions. Factors that influence a decision include the organism's environment with its dynamic rewards and risks, the complex internal state of the organism, and its imperfect knowledge of the environment. In the case of animals, it may also involve complex social factors, and experience and learning, which vary among individuals. The way that all factors are weighed and processed to lead to decisions is a major area of behavioral theory.

While classic population-level modeling is limited in its ability to integrate decision-making in its actual complexity, the development of individual- or agent-based models (IBM/ABMs) (we use ABM throughout to designate both “agent-based modeling” and an “agent-based model”) has opened the possibility of describing the way that decisions are made, and their effects, in minute detail. Over the years, these models have increased in size and complexity. Current ABMs can simulate thousands of individuals in realistic environments, and with highly detailed internal physiology, perception and ability to process the perceptions and make decisions based on those and their internal states. The implementation of decision-making in ABMs ranges from fairly simple to highly complex; the process of an individual deciding on an action can occur through the use of logical and simple (if-then) rules to more sophisticated neural networks and genetic algorithms. The purpose of this paper is to give an overview of the ways in which decisions are integrated into a variety of ABMs and to give a prospectus on the future of modeling of decisions in ABMs.

Introduction

The role of decision-making by individual organisms is largely ignored in the classical mathematical models of ecology, such as the logistic population models, Lotka-Volterra predator-prey and competition models, and their many variations. These models, as well as their extensions to space, as reaction-diffusion partial differential equation (PDE) models, treat organisms as randomly moving atoms, with added features of growth, reproduction, mortality, and interactions with their environment and other organisms. Because the classical models of ecological populations have been successful in revealing much about ecological systems, one might ask if decision-making by individuals is unimportant enough that it can be ignored at the population level, at least for simple organisms. But something like decisions are continually made, even by organisms perceived as simple. Bray (2009) notes that single-celled animals, like swimming paramecia, “continually encounter different situations… and have to evaluate their options and assign priorities.” Wagner (2009) asks “Does the bacterium choose to change direction?” and concludes that this may be a matter of perspective. In more complex organisms, such as social ants, “each individual is a sensitive unit which can process a lot of information” (Detrain and Deneubourg, 2006). These actions are programmed into the organism's DNA, and are unconscious, but clearly decisions are being made, and we will follow Ydenberg (2010) (cited in Rypstra et al., 2015) in calling a decision “wherever one or two (or more) options is/are selected.”

How important these decisions are at the population level and above is therefore an important question, even for organisms of low cognitive ability. Our perspective in this review is from that of population and community ecology and how modeling helps link individual behaviors to phenomena at the level of collections of individuals. We begin with a brief overview of how decisions have been incorporated in some classical analytic models of ecology. Then we introduce agent-based modeling (ABM) and describe how it has been used to simulate decision-making in individual movement, foraging behavior, population interactions, and social interactions within populations. This is not intended to be comprehensive, but to touch on a variety of ways ABM is used. Finally, we discuss more recent developments in modeling decisions within population models and present a prospectus for future directions.

Decisions in Classical Population Models

The use of modeling to address the question of the effect of individual decisions on population level dynamics developed more slowly than modeling of the converse question of how ecological context influences the effects of decisions on individual fitness. The latter has been explored by behavioral ecologists using classical population models for several decades, focusing especially on decisions regarding foraging movement and its effects on the fitness of individuals. Additionally, some models have been able to incorporate decision-making when modeling collections of individuals, whole populations, and even multiple populations.

Movement of animals toward favorable conditions could be decomposed into simple decisions on directed movement, or taxis, in relation to light, temperature, or resource gradients. Because it may be difficult for organisms to detect gradients, but possible to assess conditions at a current location, many models focused on kinesis, which involves decisions on when to speed up, slow down, or turn in response to detected local conditions (e.g., Gunn and Fraenkel, 1961; Schöne, 1984; Bell, 1991; Grünbaum, 1999; Gautestad, 2016). Other models used “restricted area search” in which organisms evaluate conditions within a limited area before making a movement choice (e.g., Humston et al., 2004). Movement decisions can be combined with decisions on settling at a place or leaving it, for which a variety of modeling approaches are used (Lima and Zollner, 1996). At one extreme, animals may simply move in one direction until they find a spot to settle, or they may use spatial memory and learning to gain knowledge of the landscape such that they can choose the nearest detectable habitat patch (Fahrig, 1988). Decisions on leaving a patch may increase as the level of resources is depleted. Mathematical theory has been applied to predict the optimal time to leave a patch, depending on its resource level relative to other patches and travel costs (Charnov, 1976), or to predict what succession of patches, with varying risks and rewards, to choose in order to maximize fitness over longer times (Mangel and Clark, 1988; Houston and McNamara, 1999; Clark and Mangel, 2000), an approach referred to as Dynamic State Variable Modeling (DSVM).

The step from modeling individuals to modeling collections of individuals could in some cases be done using mathematical models, in which all individuals follow the same basic rules that could be incorporated into PDEs. For example, Skalski and Gilliam (2000) used an advective-diffusion model to simulate patterns of fish formation in which the only decisions involved swimming fast or slow and having an upstream directional bias rather than pure random movement. However, many observed movement patterns of collectives, such as of flocks of birds, schools of fish, swarms of insects, and patterns formed by herding mammals, are more complex. Modeling these patterns requires more than movement decisions based on abiotic conditions, but they can be approximated when the PDEs also incorporate terms that represent decisions to move up or down population density gradients. Such individual movement behavior differs from random walk and can result in various patterns of collections of organisms (Patterson et al., 2008). “Purposeful kinesis” can alter diffusive patterns (Gorban and Çabukoglu, 2018), leading to positive density-dependent diffusion, or “super-diffusion,” and other variations on diffusion through dependence on population density (Topaz and Bertozzi, 2004; Lutscher, 2008; Almeida et al., 2015; Tilles and Petrovskii, 2016). For example, the phenomenon of clustering, in insect swarms and fish shoals, can occur when individuals accelerate in the direction of a positive density gradient (Tyutyunov et al., 2004). Flierl et al. (1999) provide a general review of mathematical modeling of collective behavior.

The influence of individual decisions on the level of whole populations and multi-population systems can also be studied when decision-making is incorporated into models of classical ecology, if the decisions are limited to simple rules, such as optimization of fitness in foraging (MacArthur and Pianka, 1966; Charnov, 1976), or in diet selection (Pulliam, 1974) and life history (Roff, 1992). For example, if all individuals foraging on a spatial environment of habitat patches with different resource levels are assumed to move among them until no further movement would increase their fitness, the population would reach what is called an Ideal Free Distribution (IFD) (Fretwell and Lucas, 1969). The IFD concept applies to a wider range of decisions, such as the choice that organisms in a population have in allocating resources in different proportions to foraging, defense, reproduction, etc. A particular example is that of predator-induced defenses, which are known to exist in many ecological systems and may involve changes in both morphology and behavior. The defended individuals are still edible but less so than undefended prey and, as a tradeoff, have lower resource intake rates than undefended prey. Recently it has been shown that the existence of inducible defenses in species at the bottom or middle of the food chain can affect the stability of the food chain, as well as the ability of the top predator to exert top-down control on the system (Vos et al., 2004). In DeAngelis et al. (2007), a system containing a predator, a prey with an inducible defense, and a resource of the prey, was studied using a differential equation model, with Holling type 2 functional responses describing the trophic interactions. The prey could choose between allocation to induced defense, with the tradeoff of lower resource uptake. The prey population evolved to switching between defense and non-defense, leading to a balance in which certain proportions of prey were in the undefended state and the rest in the defended state, the proportions depending on predator density. The prey in each state had equal fitness, so this was an IFD. This strategy of the prey influenced the populations of the whole food chain.

Mathematical models have also represented simple decisions on allocation of time and energy to foraging vs. avoiding or defending against predators (Abrams, 1982, 1993; Lima and Dill, 1990; Abrams and Matsuda, 1993; Lima and Zollner, 1996; Werner and Peacor, 2003). Other models, using differential equations, describe a forager in an environment of several prey, in which the forager could choose which prey to feed on, based on a maximization of long-term food intake (e.g., Feng et al., 2009). Another approach of classical mathematical theory in ecology is game theory, which can be used to determine the optimal strategy of an individual when the expected pay-off of a decision (e.g., to “fight or flee” when in a confrontation) depends on the decisions made by other individuals (Riechert and Hammerstein, 1983). In all these cases models showed that optimal decisions taken by members of the populations can have large ecosystem consequences.

Agent-based Modeling in Ecology

The fact that mathematical or analytic models based on a few simple decision rules can explain even complex patterns is remarkable, and such modeling is still a lively and important area of theory. But behaviorists recognized that the capacity of these simple models to represent the real decisions of organisms, determined by a multitude of inputs, was limited, and that inclusion of decision-making was important (Dill, 1987). Two trends in ecology that are relevant to that problem have accelerated over the past two decades. One trend is the increasing recognition of marked variability within populations, not just in age, size, or stage, but also in behaviors of individuals within given classes. In fact, individuals across many taxa appear to have their own personalities, or temporally consistent “behavioral tendencies” (Biro and Stamps, 2008; Beekman and Jordan, 2017). The prevalence of behavioral differences, or different personalities, that exists across animal taxa was reviewed in a pivotal paper (Bolnick et al., 2003). Personality differences such as “bold” vs. “conservative” behavior in fish (e.g., Blake et al., 2018) exist and involve various aspects of behavior, such as responses to intra-and inter-specific competition (Araújo et al., 2011; Dall et al., 2012), and tradeoffs between growth and mortality (Biro and Stamps, 2008) and early and late reproduction (Wolf et al., 2011). Bolnick et al. (2011) discuss several ways in which this individual-level specialization can affect community dynamics, which is an impetus to including individual differences in models. Variation in individuals, and therefore in their possible decision-making, casts further doubt on the capability of analytic models to adequately represent real populations. The second trend is the rapid spread of individual- or agent-based modeling (ABM), which has become an established approach with numerous modeling platforms and is encompassed by a vast literature. The latter development may provide a solution to the impasse of creating models of sophistication comparable to what is known about decision-making.

ABMs are ideally suited to accounting for individual differences in organisms. First applied to tree communities (Botkin et al., 1972), in the last few decades ABMs have become well established in all areas of ecology. ABMs simulate the interactions of autonomous “agents,” generally representing individual organisms or other real-world entities, with other agents and with the external environment (DeAngelis and Mooij, 2005). In ABMs, every individual of a population can, in principle, be simulated to almost any level of detail. Each agent may have state variables representing internal states, including behavioral states, and each can have a unique history of interactions with its environment and other agents (DeAngelis and Grimm, 2014). Agent-based modeling attempts to capture the variation among individuals that is relevant to the questions being addressed. In particular, it can incorporate what is known about individual decision-making to explore the consequences in population and community models (Parunak et al., 1998; Railsback, 2001; Vincenot, 2018).

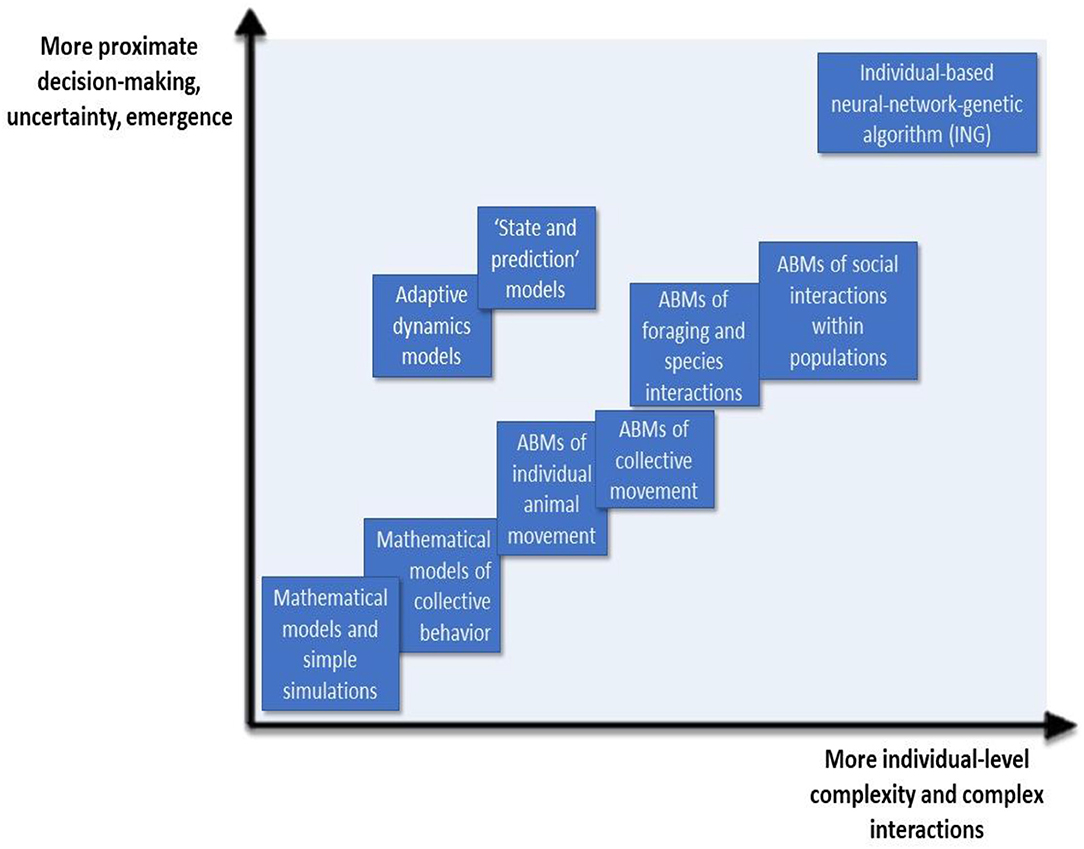

An ABM can be used where decisions are complex and/or are in a setting of populations or communities. The simplest and most straightforward way to represent individual decision-making in an ABM is to utilize logical rules following the “if-then” structure. The behavior of an individual can be modeled when the “if” part contains a condition, and the proceeding “then” part presents the individual's response. The rules governing decision-making processes can be set up in various ways. Strictly logical, deterministic rules would assign only one possible behavior to an individual in a particular circumstance (Grimm and Railsback, 2005). Alternatively, a rule may be probabilistic, with a different probability for each choice in an array of possible actions in response to some stimulus. Rules may also be a combination of probabilistic and deterministic. For many animals, however, decision-making processes may be more complex, and can be influenced by many variables including the internal state of the individual, that may vary among individuals. As will be discussed later, ABMs are increasingly being used in situations where organisms are assumed to have incomplete knowledge of the surrounding environment, and differences in perception and navigation capacities, but are able to employ cognitive skills to make choices that are good proximate decisions, albeit less than optimal. In this way, ABMs are able to encapsulate the basic underlying principles of the decision-making process in a more realistic way than classical models, and may more effectively represent the way individuals actually decide on actions and how the resulting behaviors shape population-level processes (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Schematic representation of the models and methodologies utilized to model decision-making in ecology. Along the horizontal axis, these models and methodologies are able to introduce greater individual complexity and represent more complex interactions. Along the vertical axis, the models' entities can be characterized by more proximate decision-making. There is more uncertainty introduced along this axis, but also a greater level of emergence, or higher-level behaviors resulting from lower-level interactions.

Movement Decisions and Their Consequences

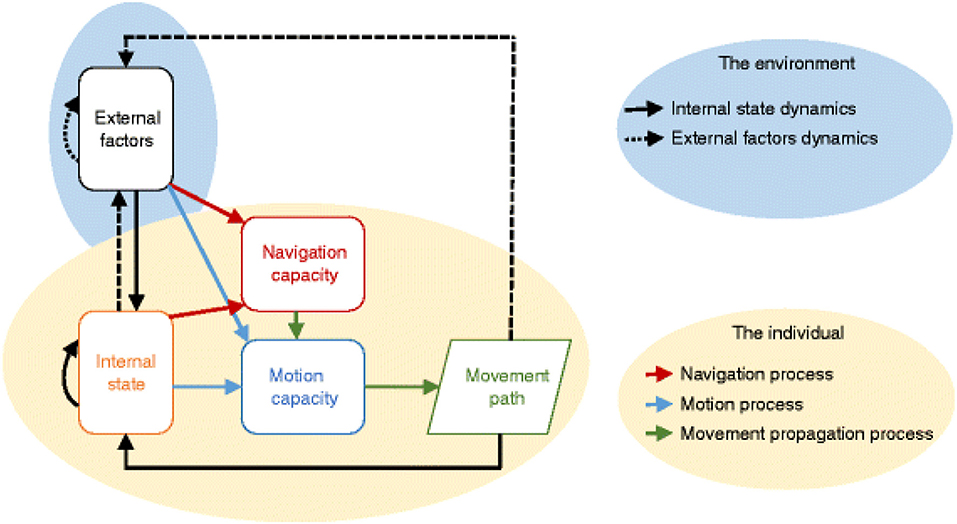

ABMs have been used extensively to simulate the movement behavior of both terrestrial and marine organisms, due in large part to their flexibility in incorporating the various components that influence an individual's movement through space. These components include an individual's internal state, external environment, and navigational and motion capabilities (Tang and Bennett, 2010; Figure 2). ABMs can represent a variety of dynamic physiological and psychological state variables comprising an organism's internal state, including commonly used bioenergetic variables (Tang and Bennett, 2010). When simulating movement through space, the external environment is generally spatially-explicit, often represented as grid cells, such that the location of agents and environmental attributes and the spatial relationship between them is explicitly defined (Duning, 1995; Bauer and Klaassen, 2013).

Figure 2. Schematic illustrating the major components influencing animal movement, all of which can be represented within an ABM (Baguette et al., 2014).

By portraying an individual's dynamic environment and internal state in detail, ABMs can capture the two important decisions that an individual in motion must continually make: when to move, and where to move. The models can also be used to derive the consequences of many organisms moving and interacting with each other at the same time, which gives rise to spatial patterns.

When to Move?

ABMs for movement generally incorporate rules that dictate when an individual agent decides to move from its current location. For real-world organisms, the onset of movement at fine scales may depend on the individual's current internal state, including its physiological and psychological conditions, the condition of the current area that the individual is in, and the presence of competition and predation (Semeniuk et al., 2011; Martin et al., 2013; Doherty and Driscoll, 2017). As such, ABMs simulating the fine-scale movement of individuals often keep track of temporal changes in the individual agent's internal state and its local surroundings. These changes generally prompt agent movement if they somehow increase (or at the very least, not decrease) the agent's fitness. For example, brown and rainbow trout agents decide to move from their position if the previous day's calculated ratio of mortality risk to growth is greater than expected. Thus, at a given time step, fish agents might move to maximize the ratio of growth to risk of mortality (Van Winkle et al., 1998). Bear agents in an ABM simulating human-bear interactions decide to move to a new location if their current location has a low amount of food, or if they are threatened by human activity (Marley et al., 2017).

An individual's decision on when to move may be influenced by the individual's life cycle and social factors. ABMs can track important biological changes of many individuals through time and be utilized to explore how these changes influence movement when placed within a social context. For example, Neuert et al. (1995) developed a model of the territorial group-living green woodhoopoe (Phoeniculus purpureus) to address the question of when a subdominant (and thus non-breeding) individual should decide to leave the group and scout for a territory on which it could breed, vs. waiting around to become high enough in status to breed at its natal site. In the model, the decision was based on its own age and rank, where the rank is correlated with age. The simple decision trait of higher propensity to go on scouting forays with increasing age provided the best agreement with empirical data.

Large scale movement, such as migration, may be triggered by temporal changes in resource availability (Van Moorter et al., 2013) along with a number of other factors, and ABMs have been utilized to explore the potential decision-rules that may dictate the timing of such behavior for various species. For example, (Duriez et al., 2009) assumed the following factors to be important for the timing of pink-footed geese migration; (1) having minimal body stores, (2) having maximal stores, (3) date, (4) temperature, (5) plant phenology, and (6) fixed duration of stay. The authors found that decision-rules related to food resources were important for dictating the onset of migration, but later in the season, decision-rules related to the geese agents' internal clocks and date are likely used.

Movement is also involved in the range expansion of a population, and Bocedi et al. (2014) modeled range expansion by considering three phases. Within the ABM, there is an initial probability of offspring dispersing from a natal cell, which can depend on population density. Then there is “transfer probability,” the direction of which is weighted by the costs of moving to each adjacent cell, which depends on landscape composition of the cell and neighboring animals. In the final phase, four alternative strategies were compared to determine which best described settlement probability, and each of which was based on a combination of several factors, including habitat suitability, presence of a potential mate, and density of conspecifics.

Where to Move?

Many organisms can process information about their environment and make movement decisions to satisfy internal desires. Changes in the internal state of an organism may result in changes in the organism's goals, movement decisions, and subsequent movement behavior (Tang and Bennett, 2010). When deciding where to move, mobile animals rely on their navigation capacity, which links the animals' internal states and external variables and manifests itself as either non-oriented, oriented, or memory-driven movement (Nathan et al., 2008; Doherty and Driscoll, 2017). The ABM framework lends itself to representing dynamic environmental cues, particularly when the spatiotemporal relationships between the agent and the environment is explicitly represented, as in spatially explicit ABMs. The internal states of individuals can be represented as dynamic state variables and integrated with the cognitive capabilities of individuals, which allows model agents to assess various movement decisions within complex landscapes and ultimately decide on their next destination (Tang and Bennett, 2010). Additionally, some stochasticity in selecting an area to move to is incorporated within many ABMs by using a combination of probabilistic and logical rules, reflecting imperfect knowledge of the environment and perception capabilities.

Many ABMs simulating animal movement explicitly represent and track various components of an individual agent's internal state in detail, often resulting in movement characteristics that closely mimic those of real-world organisms. For example, Semeniuk et al. (2012) explored potential habitat-selection strategies employed by woodland caribou in response to industrial features in the landscape and represented the caribou's internal states by primarily tracking an individual's energy gain and loss. The caribou's decision on selecting a destination cell was influenced by its daily energetic state, reproductive energy requirement, and predation risk. The way that the internal state of the agent influenced movement varied for each alternative habitat-selection strategy. The authors found that the behavioral strategy concerned with balancing daily energy intake, conserving energy for reproduction, and minimizing predation risk agreed with real-world data better than the other strategies (Semeniuk et al., 2012). Watkins et al. (2015) kept track of energy reserves of jaguar agents within a model landscape representing central Belize. The landscape cells were characterized by attributes including food availability, the presence of marks from other jaguars, and the presence of roads. When agents decide to move, their decision-making process concerning cell selection depends on the habitat attributes underlying a specific cell and the agent's internal state, namely, energy reserves. The individual jaguar's energy reserve levels modulate the preference of different attributes; consequently, agents with high energy reserve levels may decide to move to a cell that does not necessarily have high food availability; see also Lewison and Carter (2004) for an ABM simulating hippopotamus foraging behavior.

When information on the dynamics of an individual's internal state is lacking, it may be appropriate to simulate movement by using simple decision rules based on empirical observations of the resistance that different habitat types may confer to the movement of real-world individuals. For example, Aben et al. (2014) developed and explored the effectiveness of an ABM in simulating forest bird movement, in which a bird agent's selection of a cell (habitat area) to move to at any given time step was partially determined by the land-cover class that characterized a given cell. Land-cover classes conferring more resistance to movement were given higher “cost” values. Spatial cells characterized as having a low cost to birds that are moving through the cells had a higher probability of being selected than cells characterized as having a high cost. Similarly, simple decisions rules governing the selection of destination cells may be based on the quality of the surrounding environment, such that agents generally move toward preferred or favorable areas. In an ABM developed to estimate landscape connectivity for bighorn sheep, each cell in the landscape is represented by landscape attributes including its proximity to escape terrain and the presence of roads (Allen et al., 2016). Bighorn sheep agents have a higher probability of moving to cells closer to escape terrain and away from roads as these cells represent more favorable habitats to real-world bighorn sheep. The characteristics of the surrounding environment also played a major role for agents deciding on a destination in ABMs simulating movement for tiger (Kanagaraj et al., 2013), tortoise (Anadón et al., 2012), and capercaillie (Graf et al., 2007).

Collective Movement Behavior

Many of the above models of animal movement are single-agent ABMs, as opposed to multi-agent ABMs used to simulate collections of interacting individuals. One of the enigmas of natural history is the striking coordinated collective movements of various taxa (birds, insects, fish, mammals, etc.). Investigation of these phenomena is based on the recognition that the movement characteristics of individuals are often influenced by the spatial position and movement of conspecifics, which results in collective movement (Krause et al., 2010). Individuals must make decisions on the initialization and direction of movement, and these decisions somehow incorporate the states of their neighbors. As Sumpter (2006) notes, the key to understanding collective behavior lies in identifying the principles of the behavioral algorithms followed by individual animals and how information flows between the animals. The decision-making process of individuals involved in collective movement has been represented by a spectrum of simple to complex rules within ABMs.

Both Sumpter (2006) and Couzin and Krause (2003) provide reviews of the use of ABM in describing collective behaviors of organisms based on relatively small sets of decision rules. In an early use of a spatially explicit ABM, Huth and Wissel (1992) showed that the complex movement of fish schools could be described by a few rules; the fish tend to keep a certain distance between themselves and a number of its close neighbors and move parallel to other fish when they are within a certain range. The fish agents decide to move away from neighbors if they are too close (repulsion) or align themselves with their neighbors if they are too far (attraction). Size sorting also occurs in fish schools, which may be represented by simple rules, where individuals tend to actively stay with individuals of similar size and avoid those of a different size (Hemelrijk and Kunz, 2005). Couzin et al. (2002) proposed a similarly simple model in which individual animals followed three rules of thumb; (1) move away from very nearby neighbors, (2) adopt the same direction as those that are close by, and (3) avoid becoming isolated; thus, the authors utilized the simple rules of repulsion, alignment, and attraction. In taking into account the location of an individual's neighbors at all times, the authors' model was able to reproduce collective behavior often seen in nature, including swarming and torus behavior.

Dynamics of a small herd of mammal browsers were described by a more complex decision tree than those used by Huth and Wissel (1992), and Couzin et al. (2002). Gueron et al. (1996) integrated a combination of “stress zones,” “attraction zones,” “neutral zones,” and “rear zones” in the decision-making process of individuals moving within a herd. The various zones corresponded to specific distances extending from each individual, and each individual could invade the zones of other individuals. Probabilities and directions of movement depended on the type of zone an individual invaded. For example, if an individual sensed another individual within its “stress zone,” the individual slowed down to avoid collision. If neighbors were all on one side of the individual, the individual moved toward neighbors. Even though this sort of collective behavior is a much looser kind of group cohesion than fish schooling, the ABM showed that by simply integrating information about an individual's neighbors into the decision rules, many patterns of collective movement could emerge. Hoare et al. (2004) used a similar model to explain the group size distributions of fish, where dynamic “zones of interactions” strongly influence the size of groups in simulations.

Foraging Decisions and Population Interactions

The use of ABM in modeling foraging behavior changes the emphasis from predicting the fitness of the individual based on its decisions to predicting temporal and spatial patterns formed by large collections of individuals foraging and competing for resources (though sometimes interacting positively).

A common, though not universal, characteristic of ABMs is that they are based on observations of real populations in real locations. Thus, the assumptions built into the models constitute hypotheses that can be tested against observational data. A few models will be mentioned here: Barnacle geese (Branta leucopsis) in Helgeland, Norway, white-fronted geese (Anser albifrons) in Lake Miyajimanuma, Japan, oystercatchers (Haematopus ostralegus) in the Exe estuary, England, salmonids in Little Jones Creek, California, USA, and dusky dolphins (Lagenorrhyncus obscurus) and killer whales (Orcinus orca) near Kaikoura, New Zealand.

Kanarek et al. (2008) modeled barnacle geese that return to the same group of islands each year as a migration stop. The geese are assumed to vary in age, energy reserves, genetic disposition, and spatial memory of previously visited locations. A goose chooses a specific island based on a combination of factors; constraint due to rank in the dominance hierarchy, memories of previously visited sites and past reproductive success, inherited genetic influences toward site faithfulness, and knowledge of the available biomass density. Within the island the goose chooses to forage on a particular patch until its intake rate drops below a certain amount. Once a goose decides to leave a patch, it uses its knowledge to choose where to go next, assigning a score to a patch based on several factors. A bioenergetics model keeps track of the body mass of the goose, and the goose leaves the staging area either when a threshold of the amount of energy stored or when the end of the stopover period is reached. Each year that a goose returns to the same patch, its familiarity and ability to locate food increases as well as its hierarchical rank.

A dominance hierarchy is also incorporated into the ABM of a migratory bird, the oystercatcher, feeding on mussels in a tidal estuary in England during the winter (Stillman et al., 1997). A population of individual oystercatchers was modeled on a two-dimensional patch, and the individuals were assigned to places in a dominance hierarchy. When two individuals come within a certain distance, and one is handling prey, the other might attack to attempt to steal the prey, prompting the other to fight back, with the dominant individual always winning. The alternative behavior is avoidance, an action taken with higher probability by less dominant individuals. Avoidance subtracts less time from foraging than fighting. The authors assumed that individuals could calculate the costs vs. benefits of a given action and decide accordingly. The results of the model show, in accord with observations, much less incidence of interference than equivalent analytic models, because, given the differences in rank that are incorporated in the ABM, dominants wasted less time avoiding subdominants, and subdominants avoided fighting.

In the case of white-fronted geese, an ABM explored possible positive interactions among the geese (Amano et al., 2006). The model tested the hypothesis that geese foraging in patches usually have no prior information on patch quality before making a choice but can benefit from choosing patches already occupied by conspecifics; i.e., the presence of conspecifics in the patch has the potential positive effect of decreasing the need for vigilance, although it also causes prey to be depleted faster. The authors tested the hypothesis and found that it was better than alternatives foraging models at describing empirical data, indicating that the assumptions are realistic bases of foraging decisions.

In the classical DSVM theory mentioned earlier, tradeoffs are assumed between risks of starvation and predation. Many ABM foraging models also incorporate these risks. Railsback and Harvey (2002) used ABM to predict empirical patterns of habitat selection in drift-feeding juvenile trout foraging in a stream, based on assumptions concerning their decisions to choose habitat to forage in, given a range of empirical factors; e.g., water depth, velocity, available food, in the stream environment. The risks involved in deciding to move to a given location were starvation, predation by terrestrial animals, predation by fish, high water velocity (which requires energy to stay in place), stranding, and competition. A bioenergetics model was used to follow daily growth, and daily predation mortality depended on the size of the fish and water depth at its location, which gave the current “state” of the individual. Three foraging strategies were compared, based on the agent's state and prediction of conditions over the near term (thus the authors label their approach “state and prediction theory”). The strategy that compared well with all observed patterns involved daily decisions that maximized, over a longer term, the “expected maturity” (EM), or the product of predicted survival from starvation and other mortality risks and the fraction of reproductive size reached over the period of the 75-day simulation. The EM strategy, in which the fish agent maximizes both growth and survival, gives better results than other maximization criteria, such as maximizing only growth or only survival probability, used in many classical models.

These studies all illustrate the ability of ABMs not only to incorporate high amounts of the complexity of real ecological systems and their ability to compare output with empirically observed patterns, but also to derive more realistic pictures of the decision-making process.

Lima (2002) noted the importance of the behavioral decisions of the predator when studying predator-prey interactions, rather than treating predators as “unresponsive black boxes.” Accordingly, ABMs have also been used to extend the focus of predation risk beyond merely the prey strategy to include feedbacks from the predator or from competitors. A detailed investigation of tradeoffs of dusky dolphins choosing between feeding and avoiding predation by killer whales is given in a spatially explicit ABM of Srinivasan et al. (2010). The authors explored the fitness costs and benefits of various escape strategies potentially used by dusky dolphins, including the time spent hiding in a refuge from predation and degree of vigilance when feeding. The model included counter strategies of the amount of time a killer whale would wait for a dolphin to emerge from a refuge, so the model contains a version of game theory. Another example of feedback effects, in this case coming from competition, is illustrated by a model of Peacor et al. (2007). Individual foragers and a common resource for which they compete were simulated, both with and without the presence of a predator. The density of competing foragers affected the tradeoff in foraging. Under low density of competitors, the forager spent 40% of its time eating, but the time eating decreased to 7% when the forager density was high. This outcome resulted from the decreased benefits of foraging, as the resource was reduced by competitors. Such an outcome could not easily be anticipated or incorporated in simple models. A species' response to predation risk can affect whole food chains. An illustration of how behaviors of herbivores can modify top-down effects of predators on plants is the ABM of Schmitz and Booth (1997) for a tri-trophic chain (spiders, grasshoppers, and a food base of two plant types, grass and a herbaceous plant) of individual organisms on a spatial lattice. The spiders could affect the grasshoppers directly, by predation, and indirectly, by causing grasshoppers within a certain radius to move from grass to the safer herb sites. The model allowed the relative effects of direct predation and the predator avoidance by grasshoppers to be examined individually. The model predicted long-term field observations of the predator's top-down effect and showed the importance of including the behavioral response of the herbivore.

Social Interactions in Populations

Social behavior requires decisions involving, among other things, reproduction, parental care, and territorial or home range defense. These, plus a wider range of activities, have been represented in ABMs.

Several studies have addressed the question of when to reproduce, incorporating external factors such as population density and the availability and quality of resources in an area (Stewart et al., 2005; Brouwer et al., 2015). When deciding to reproduce, individual agents within an ABM often consider information of the surrounding environment. An individual agent's decision to reproduce is frequently represented in a logistical or probabilistic manner, in which agents may decide to reproduce if they meet some requirement or threshold. For example, Ye et al. (2014) used a grid-based spatially explicit ABM to gain insight on how the population dynamics of a virtual species is influenced by landscape structure and various life history traits. In the ABM, the resource share of an individual reflects the number of individuals in a spatial cell and the cell's underlying habitat quality. Only individual agents with a resource fraction over a given threshold may reproduce in a given time step with a given probability, reflecting the importance of competition and the quality of the surrounding habitat in driving reproductive success.

The agent's internal state also influences its decision to reproduce. Hancock et al. (2005) developed an ABM to predict the population dynamics of Bornean bearded pigs, tracking the “fatness index” of each pig agent in the model. The reproduction status of each agent varied according to their respective fatness index, which in turn depended on the available food supply and the density of the pig population. A pig agent decides to reproduce if its fatness index is above a specific threshold, such that agents in a large population with low food supply are unlikely to reproduce due to low fatness indices (Hancock et al., 2005). Fish agents within another ABM also took their internal state into consideration in deciding when to spawn. The ratio of actual weight to expected weight of a fish of a given length (a “condition index”) is tracked for each fish agent, and only agents with ratios over 0.75 were able to spawn (Rashleigh and Grossman, 2005).

After reproduction, decisions must be made on parental care. Different strategies of parental investment reflect variation in the decision-making process of individuals, and ultimately have consequences for the dynamics of the population. Decisions involved in provisioning of offspring by bluebirds were studied by Davis et al. (1999), from the point of view of survival of the offspring under different conditions of food availability in the environment. The authors performed model simulations for different levels of food availability by assuming four different strategies on feeding decisions: (1) Feed the smallest first, (2) feed the largest first, or (3) feed the hungriest first, in each case going to the next larger, smaller, or less hungry, respectively, if the offspring representing the first choice was full. These choices were compared to random feeding (strategy 4). Environmental conditions determined which strategy maximizes the nest success, in terms of total biomass of surviving fledglings, with strategies (1), (2), and (3) performing best, successively, with increasing food availability. The random strategy was never the best.

The formation and maintenance of territories and home ranges occurs in many taxa. ABMs can simulate the spatiotemporal changes in resource availability throughout the environment and interactions between various agents through time, potentially elucidating the mechanisms underlying territory and home range dynamics. In order to aid conservation planning for the tiger (Panthera tigris) by providing an estimate of population number, location and size of territories, Carter et al. (2015), modeled territory formation of both females and males using a spatially explicit ABM. Females at 3 years of age were assumed to move to a site within 33 km of their natal site, and at least 2 km away from any other female, and to establish the center of her territory where prey density was highest. If the female failed to find such a site, she lowered the limit on neighboring females from 2 to 1 km. A female was assumed to be able to sense the total prey in her territory and in neighboring spatial cells. She could try to add habitat cells to their territories based on a few decision rules, including prey availability and the status of the neighboring female tiger's hierarchical status (avoiding cells near a female of higher status, which is correlated with age). When possible, she adds habitat cells to her territory until the total amount of prey reaches a certain threshold. Another spatially explicit model of home range dynamics is that of Wang and Grimm (2007) for the common shrew (Sorex araneus). Shrews were assumed to continually adjust their territories by sensing the amount of food in a cell of the habitat and the presence of other individuals. Individuals tried to optimize their home range by preferentially selecting cells with high food sources and avoiding cells occupied by other individuals. Acquisition and release of cells followed an optimization procedure, in which the shrew is assumed capable of ranking all the cells in its territory and releasing the worst ones in favor of adding new ones. These simple model rules predicted realistic territories for both tigers and shrews.

Developments in the Modeling of Decisions in Population Models

The papers reviewed above show that ABM is an important departure from earlier mathematical approaches, which, collectively, have been critical theoretical frameworks over the past few decades. In many earlier approaches, the individual was assumed to make a sequence of decisions through time that would result in optimal fitness at some end time. These approaches often assume knowledge of future conditions and ignore the feedbacks on the individuals through changes in the environment created by the individual's own decisions. To incorporate the feedbacks and uncertainty that are present in real ecological systems, a trend in ABMs has been to simulate how proximate decisions are made based on the individual's current state and short-term predictions. This is modeled differently by different modeling groups. As noted earlier, Railsback and Harvey (2002) (see also Railsback et al., 1999) use a “state and prediction theory” strategy for individuals, which estimate an “expected survival” over a specified time horizon over which little appreciable change in the environment is expected, considering the risks of predation, starvation, etc., and choosing the behavior that achieves the best fitness over that time. Giske and his group (e.g., Eliassen et al., 2016) find the adaptive behaviors for situations encountered through selection in genetic algorithms (GA) and artificial neural networks (ANNs). Other ABM modeling approaches include the computational system Digital Organisms in a Virtual Ecosystem (DOVE), in which a GA is used to allow phenotypic plasticity to evolve and interact with a dynamic environment (Peacor et al., 2007).

Borrowing concepts from machine learning and artificial life studies, modelers such as those noted above have utilized ANN and GA (together referred to as individual-based neural-network-genetic algorithm, or ING techniques) to represent the decision-making processes and consequent behaviors of organisms. Instead of fixed rules governing the way an organism makes decisions, ING techniques are flexible approaches that use principles of neurobiology and natural selection to solve optimization problems, resulting in individuals making adaptive decisions (Huse et al., 1999; Hamblin, 2013). ABMs that use genetic algorithms to govern decisions initialize a population of individuals with different solutions to a given optimization problem. Optimization problems may include finding the decision that will maximize fitness during foraging, or the probability of survival when selecting a patch (Hamblin, 2013). The individuals with the best solutions to the problem are allowed to reproduce through various commonly recognized selection operators, and reproduction continues for many generations. Trebitz (1991) was an early user of a GA-type approach to estimate the optimal spawning time for largemouth bass. In the model a female that spawned too early in spring risked the loss of eggs or larvae due to random cold snaps, while if it spawned too late it risked zooplankton being depleted by the offspring of earlier spawning females.

ANNs “train” the weights of input data by continuously modifying these weights until the resulting decisions and subsequent behaviors of individuals reach a specific fitness measure. In this way, ANNs and the way they capture the decision-making process of individuals mirror brain functions by “learning” from the outputs of the various input data weight modifications. Once an ANN is trained, it can be used on new input data to determine the decisions and behaviors that satisfy the specific fitness measure (Huse et al., 1999; Lek and Guégan, 1999). In GAs and ANNs, as in the more fixed logical and probabilistic decision-making rules within ABMs discussed earlier, the decision-making processes of individuals are generally geared to optimize some sort of fitness measure, but the decision-making strategy evolves through selection.

ANNs have been increasingly used to represent the decision-making processes of organisms, particularly with respect to movement through space. As the decisions of real-world individuals are driven by neuronal responses to internal and external stimuli, neural networks are well-suited to represent decision-making in an individual agent (Eliassen et al., 2016). Once a fitness criterion is identified for a given ABM, the ANN can be trained to find the input weights that correspond to outputs best fitting the fitness criterion (Huse et al., 1999). ANN training can occur in several ways, but here we focus on training with GAs, an approach common within ABMs utilizing ANNs. GAs are optimization tools that utilize the principles of crossing over and mutation to essentially “evolve” the decision-making processes of individuals, without the need for probabilistic or logistical rules.

For example, Okunishi et al. (2009) developed an ABM to simulate the growth and large-scale movements of Japanese sardines with the goal of exploring the effects of climate change on the population dynamics of the species, primarily its distribution and production in the North Pacific. The authors utilized an ANN to represent the way fish decide on movement directions when migrating to spawn. The inputs to the ANN were environmental factors known to influence the migration of sardines and included ocean current speed, the distance from land, and the experienced temperature change during subsequent days. Back propagation (a training method where weights are assigned to the various inputs based on a training data set) was one method used to train the ANN on spawning migration trajectories from actual sardines. The authors also used a GA to find the sardine offspring's input weights that would produce optimal outputs through crossing over and mutation of the parent sardine's weights. In training the ANN with a GA, the sardines' decisions representing swimming directions were allowed to evolve through many simulations; subsequently, the authors were able to find optimal combinations of weights that produce realistic migration trajectories. They found that combining back propagation with a GA to determine input weights produced the most realistic migration trajectories, indicating that utilizing the principles underlying the GA (in tandem with observed movement data) adequately captures the decision-making process of migrating sardines (Okunishi et al., 2009).

Morales et al. (2005) utilized several ANNs, each in combination with a GA, to determine efficient movement decisions for elk within a spatially explicit ABM. Movement decisions to be made by the elk included when to switch behaviors from foraging to exploring, where to move if foraging or exploring, and which type of plant to consume at a given time if foraging. The fitness measures that characterized the efficiency of elk agent decisions were energy gain for fat reserves and survival probability associated with predation risks. Percent body fat, forage biomass, and local predation risks were a few of the ANN inputs representing both internal and external movement stimuli. Rather than setting specific rules to guide the decision-making processes, the authors allowed the process to evolve over many generations.

ANNs were also used to model movement in Mueller and Fagan (2008), who noted three basic types of pattern resulting from movement (or lack thereof): sedentary, migratory, and nomadism. The authors assumed that landscape structure drove individual-level movement types and that there were four gradients in hierarchical order; resource abundance, spatial configuration of resources, temporal variability of resource locations, and temporal predictability of resources. Mueller et al. (2011) followed up by using ANNs to evolutionarily train model organisms to use and combine different types of information representing the different movement behaviors (memory, oriented, and non-oriented movements). 240 individual animals were simulated moving across landscape and making choices of patches and, in doing so, depleting exhaustible resources. Different movement strategies involving combinations of these movement types worked better on different landscape types. After 5,000 generations with inheritance, survivors using unique movement strategies had optimized fitness on particular landscapes.

In incorporating optimization of fitness, classic analytic models omit consideration of the immediate, or proximate, complexities that organisms encounter. This allows the integration of individual strategies with ultimate fitness, but the proximate mechanisms through which organisms solve problems are largely ignored (Sih et al., 2004; Fawcett et al., 2013; Eliassen et al., 2016). Animals need to be able to respond quickly and adequately in situations they have never experienced before; that is, the world is too complex for evolution to produce rules for every possible circumstance. It is likely that animals will evolve rules that perform well on average in their natural environment (McNamara and Houston, 2009). One of the basic advantages of ABMs is their ability to incorporate such heuristic, or rule of thumb, decision-making to perform well in complex environments. The GA approach allows one to simulate how such rules evolve.

Toward this end Giske et al. (2013) formulated a model based on recent insights from a range of empirical disciplines that sheds light on the processes involved with decision making. In vertebrates, multipurpose rules are arbitrated through an “emotion system,” which describes the integration of information, motivation, and physiological state in determining physiological and behavioral outcomes. These outcomes affect the survival, growth, development, space use, and life history of the organism. Giske et al. (2013) modeled fish, where the fish had the choice of moving among different depths. Fish at deeper depths were generally safer from predation, but food was more limited, though uncertainty was entered into the model by letting both food levels and predation risk vary stochastically from fish generation to generation. The authors employed the survival-circuit concept (LeDoux, 2012), in which emotions form the basis for decisions, and they contribute to the survival or fitness of the organism. The first half of the survival-circuit is “emotional appraisal.” It starts with sensory input, considers motivational impact related to developmental stage, and may potentially activate the organism into a “global organismic state,” such that the whole organism is focusing on the situation. The second half of the survival circuit; the “emotional response,” consists of physiological responses and behavior. Physiological activation enables the organism to focus its sensory attention, brain activity, and potentially also bodily functions, such as heartbeat and muscle tension, toward the present situation. Fear and hunger are the emotions, and the ABM includes sensory inputs. The options for a fish are to stay at its current depth or move a short distance upward or downward, as determined by equations incorporating hunger and fear. On the basis of its global organismic state, the motivated fish behaves in a way that maximizes its net neuronal response.

The model of Giske et al. (2013) predicted the same general type of spatial distribution patterns that classic optimization and game models produce, such as diel vertical migration with some extension around the average. But the model of Giske et al. (2013) differed from the classic models by allowing the fish to respond on immediate timescales to food and perceived risk, as opposed to optimization criteria involving only long-term goals. For example, danger is avoided because of an evolved proximate preference to stay with others or in darker waters when afraid, while danger is largely ignored when hungry. This is important in a fluctuating environment, where simple rules of thumb couple proximate constraints in determining behavior, with long-term adaptive value.

Prospectus

In his book “Sociobiology,” Wilson (1975) foresaw the gradual merger of population biology and behavioral ecology and the growing importance of neurophysiology to the latter (Wilson's Figure 1.2). These developments have been accelerated through ABM and ANN, particularly through using ABM as a means through which population and community dynamics emerge from the adaptive traits of individuals, including “how individuals make decisions in response to other individuals, the environment, or changes in themselves” (Grimm and Railsback, 2005).

Future development of ABM in modeling decision-making in ecology will be influenced by the continued refinement of modeling methodology and increases in needed data for parameterizing ABMs. Two of the modeling methodologies, the “state and predict” (Railsback and Harvey, 2002) and ING (Eliassen et al., 2016) continue to be developed. In particular, a cognitive architecture based on the survival-circuit concept (LeDoux 2012) forms a general modeling framework for linking decision-making to neurobiological mechanisms (Bach and Dayan, 2017; Landsrød, 2017; Budaev et al., 2018). Other approaches to providing rules of thumb for individuals, such as Fuzzy Cognitive Maps (FCM), based on Fuzzy Set Theory (Berkes and Berkes, 2009), are also being used in evolving predator-prey systems. In addition, off the shelf ABM modeling programs such as NetLogo and Ecobeaker are making development and use of ABM easier (e.g., Railsback and Grimm, 2011). Concerning relevant data, ABMs generally require a large amount of data at the individual level and site level. Such data are generally only available for ecological systems that have been intensively studied. But technology is rapidly increasing data collection capabilities, and the availability of remote sensing data and the ease with which these data are integrated within the ABM framework facilitates the development of decision rules based on a plethora of environmental attributes that potentially drive animal decisions. This may facilitate wider use of ABM, though this will require more coordinated efforts in making data broadly available to the modeling community (Hampton et al., 2013).

Recent advancements in technological tools should facilitate the parameterization of future ABMs developed for simulating dispersal, migration, and local-scale movements of animal groups. In particular, developments in GPS telemetry (and satellite telemetry in general) and biotelemetry devices have allowed for remote tracking of an individual's movement, physiological state, and behavior over long periods of time at relatively fine temporal resolutions (Cooke et al., 2004). This is especially useful considering the challenges ecologists face when attempting to directly observe and study free-ranging animals in a non-invasive manner. Basic movement parameters, including step length and turning angle distributions, can be derived from a time series of relocation data obtained from GPS and satellite telemetry and together shed light onto the limits of an individual's motion capacity. Subsequently, parameters driving agent movement within an ABM can be made more accurate. Bioenergetic models used to track agents' growth and reproduction within ABMs can be further parametrized with information gained from biotelemetry monitoring of undisturbed animals in their natural environments. The wealth of data generated for many species thus far should allow ecologists to more accurately model how individuals decide on an action in response to dynamic internal and external variables. What will most define the future success of ABM will be its ability to address complex questions that are difficult for traditional approaches. These questions include, among many others, the origin of collective actions, the interactions of tradeoffs at the individual level and the whole ecological system, the dynamics of complex social systems, and applications to conservation and management issues.

How collective actions such as migration are initiated, usually by a small fraction of leaders, has been discussed as resulting from differences in experience within populations (Ferno et al., 1998; Krause et al., 2000). Collective actions that benefit the whole group, but which may have negative fitness consequences for individuals, have long attracted attention, but are still not well-understood and may profit from use of ABM. An example is “mobbing action” by birds against nest threats. Unrelated birds and even birds of different species may be involved in these aggressive actions against a threat to nests, such as hawks or owls. While there is clear benefit to each individual in protecting its nest, there are also costs, such as becoming a victim of the threat or revealing the location of one's nest. Wheatcroft and Price (2018), in an empirical/theoretical study, proposed that collective action in this case can build up among birds whose nest locations are distributed across various distances from the threat. Birds nearest the nest respond first, and others that have nests farther and farther away decide to join as the risk to any individual declines with the growing size of the mob. The authors used a mathematical model with two individuals to analyze the amount of investment in each in aggressiveness to the threat. While the mathematical model provides insight, this is the type of problem where an ABM, which can simulate the actions of many birds with individual variation, could provide output directly comparable with observations of mobbing behavior.

Social interactions of at least moderate complexity already occur in several of the models noted above, in which social hierarchies constrain actions, but extension to much more complex interactions is possible using ABM. For example, in many primate troops the type and level of interaction between individuals, whether positive (cooperation) or negative (e.g., fighting) depends on genetic relatedness. Because there is kin-recognition, any interaction, such as a fight between two unrelated individuals, can give rise to a larger complex of interactions involving their relatives (Cheney and Seyfarth, 1992). Modeling the behavior of such societies may require ABM to represent a network of relevant interactions.

Behavioral ecologists and modelers like to think that their work can have some useful applications in conservation and wildlife management. A review by Caro (2007) of application of ecological theory found little evidence that many of the applications proposed so far by behavioral ecology, based on hypothetical conditions, would be effective in practice. However, ABM may be able to bridge the gap between theory and real conservation issues (Wood et al., 2015). For example, to elucidate whether specific predation strategies influenced the nesting success of waterfowl, Ringelman (2014) simulated the movements of different predators in a landscape with clumped and dispersed nests. The results of the ABM suggested that managers concerned with nesting success of waterfowl should consider the various behavioral strategies used by nest predators when creating and managing potential nesting habitat. The results highlight the practical applications of ABMs, particularly when utilized as tools for wildlife ecology investigations (some examples of which are detailed in McLane et al., 2011).

The above are all areas in which ABM incorporating decision-making has room to expand. ABM is still a young field, and its potential for contributing to the understanding of how decisions are made by animals and how they affect whole ecosystems has yet to be fully exploited.

Author Contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct and intellectual contribution to the work, and approved it for publication.

Funding

DD was supported in part by the U. S. Geological Survey's Greater Everglades Priority Ecosystem Science Program (KA30CTF). SD was supported by a McKnight Dissertation Fellowship.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We greatly appreciate the very useful help of Jacoby Carter of U. S. Geological Survey and of two reviewers. Any use of trade, firm, or product names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government.

References

Aben, J., Strubbe, D., Adriaensen, F., Palmer, S. C. F., Travis, J. M. J., Lens, L., et al. (2014). Simple individual-based models effectively represent Afrotropical forest bird movement in complex landscapes. J. Appl. Ecol. 51, 693–702. doi: 10.1111/1365-2664.12224

Abrams, P., and Matsuda, H. (1993). Effects of adaptive predatory and anti-predator behaviour in a two-prey-one-predator system. Evol. Ecol. 7, 312–326. doi: 10.1007/BF01237749

Abrams, P. A. (1993). Why predation rate should not be proportional to predator density. Ecology 74, 726–733.

Allen, C. H., Parrott, L., and Kyle, C. (2016). An individual-based modelling approach to estimate landscape connectivity for bighorn sheep (Ovis canadensis). PeerJ 4:e2001. doi: 10.7717/peerj.2001

Almeida, P. J. A. L., Vieira, M. V., Prevedello, J. A., Kajin, M., Forero-Medina, G., and Cerqueira, R. (2015). What if it gets crowded? Density-dependent tortuosity in individual movements of a Neotropical mammal. Austral Ecol. 40, 758–764. doi: 10.1111/aec.12250

Amano, T., Ushiyama, K., Moriguchi, S., Fujita, G., and Higuchi, H. (2006). Decision-making in group foragers with incomplete information: test of individual-based model in geese. Ecol. Monograp. 76, 601–616.doi: 10.1890/0012-9615(2006)076[0601:DIGFWI]2.0.CO;2

Anadón, J. D., Wiegand, T., and Giménez, A. (2012). Individual-based movement models reveals sex-biased effects of landscape fragmentation on animal movement. Ecosphere 3:art64. doi: 10.1890/ES11-00237.1

Araújo, M. S., Bolnick, D. I., and Layman, C. A. (2011). The ecological causes of individual specialization. Ecol. Lett. 14, 948–958. doi: 10.1111/j.1461-0248.2011.01662.x

Bach, D. R., and Dayan, P. (2017). Algorithms for survival: a comparative perspective on emotions. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 18, 311–319. doi: 10.1038/nrn.2017.35

Baguette, M., Stevens, V. M., and Clobert, J. (2014). The pros and cons of applying the movement ecology paradigm for studying animal dispersal. Move. Ecol. 2, 1–13. doi: 10.1186/s40462-014-0013-6

Bauer, S., and Klaassen, M. (2013). Mechanistic models of animal migration behaviour - their diversity, structure and use. J. Anim. Ecol. 82, 498–508. doi: 10.1111/1365-2656.12054

Beekman, M., and Jordan, L. A. (2017). Does the field of animal personality provide any new insights for behavioral ecology? Behav. Ecol. 28, 617–623. doi: 10.1093/beheco/arx022

Bell, W. J. (1991). Searching Behaviour: The Behavioral Ecology of Finding Resources. London, UK: Chapman and Hall

Berkes, F., and Berkes, M. K. (2009). Ecological complexity, fuzzy logic, and holism in indigenous knowledge. Futures 41, 6–12. doi: 10.1016/j.futures.2008.07.003

Biro, P. A., and Stamps, J. A. (2008). Are animal personality traits linked to life-history productivity? Trends Ecol. Evol. 23, 361–368. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2008.04.003

Blake, C. A., Andersson, M. L., Hulthén, K., Nilsson, P. A., and Brönmark, C. (2018). Conspecific boldness and predator species determine predation-risk consequences of prey personality. Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 72:133. doi: 10.1007/s00265-018-2544-0

Bocedi, G., Zurell, D., Reineking, B., and Travis, J. M. J. (2014). Mechanistic modelling of animal dispersal offers new insights into range expansion dynamics across fragmented landscapes. Ecography 37, 1240–1253. doi: 10.1111/ecog.01041

Bolnick, D. I., Amarasekare, P., Araújo, M. S., Bürger, R., Levine, J. M., Novak, M., et al. (2011). Why intraspecific trait variation matters in community ecology. Trends Ecol. Evol. 26, 183–192. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2011.01.009

Bolnick, D. I., Svanbäck, R., Fordyce, J. A., Yang, L. H., Davis, J. M., Hulsey, C. D., et al. (2003). The ecology of individuals: Incidence and implications of individual specialization. Am. Nat. 161, 1–28. doi: 10.1086/343878

Botkin, D. B., Janak, J. F., and Wallis, J. R. (1972). Some ecological consequences of a computer model of forest growth. J. Ecol. 60, 849–872. doi: 10.2307/2258570

Brouwer, L., Tinbergen, J. M., Both, C., Bristol, R., David, S., Komdeur, J., et al. (2015). Experimental evidence for density-dependent reproduction in a cooperatively breeding passerine. Ecology 90, 729–741. doi: 10.1890/07-1437.1

Budaev, S., Giske, J., and Eliassen, S. (2018). AHA: a general cognitive architecture for Darwinian agents. Biol. Inspired Cogn. Arch. 25, 51–57. doi: 10.1016/j.bica.2018.07.009

Caro, T. (2007). Behavior and conservation: a bridge too far? Trends Ecol. Evol. 22, 394–400. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2007.06.003

Carter, N., Levin, S., Barlow, A., and Grimm, V. (2015). Modeling tiger population and territory dynamics using an agent-based approach. Ecol. Model. 312, 347–362. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolmodel.2015.06.008

Charnov, E. L. (1976). Optimal foraging, the marginal value theorem. Theoret. Popul. Biol. 9, 129–136. doi: 10.1016/0040-5809(76)90040-X

Cheney, D. L., and Seyfarth, R. M. (1992). How Monkeys See the World: Inside the Mind of Another Species. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Clark, C. W., and Mangel, M. (2000). Dynamic State Variable Models in Ecology: Methods and Applications. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Cooke, S. J., Hinch, S. G., Wikelski, M., Andrews, R. D., Kuchel, L. J., Wolcott, T. G., et al. (2004). Biotelemetry: a mechanistic approach to ecology. Trends Ecol. Evol. 19, 334–343. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2004.04.003

Couzin, I. D., and Krause, J. (2003). Self-organization and collective behavior in vertebrates. Adv. Study Behav. 32, 1–75.

Couzin, I. D., Krause, J., James, R., Ruxton, G. D., and Franks, N. R. (2002). Collective memory and spatial sorting in animal groups. J. Theoret. Biol. 218, 1–11. doi: 10.1006/yjtbi.3065

Dall, S. R. X., Bell, A. M., Bolnick, D. I., and Ratnieks, F. L. W. (2012). An evolutionary ecology of individual differences. Ecol. Lett. 15, 1189–1198. doi: 10.1111/j.1461-0248.2012.01846.x

Davis, J. N., Todd, P. M., and Bullock, S. (1999). Environment quality predicts parental provisioning decisions. Procee. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 266, 1791–1797. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1999.0848

DeAngelis, D. L, Vos, M., Mooij, W. M., and Abrams, P. A. (2007). “Feedback effects between the food chain and induced defense strategies,” in From Energetics to Ecosystems: The Dynamics and Structure of Ecological Systems, eds N. Rooney, K. McCann, and D. Noakes. (Dordrecht: Springer-Verlag), 213–236.

DeAngelis, D. L., and Grimm, V. (2014). Individual-based models in ecology after four decades. F1000prime 6:39. doi: 10.12703/P6-39

DeAngelis, D. L., and Mooij, W. M. (2005). Individual-based modeling of ecological and evolutionary processes. Ann. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syste. 36, 147–168. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.36.102003.152644

Detrain, C., and Deneubourg, J. L. (2006). Self-organized structures in a superorganism: do ants “behave” like molecules? Phys. Life Rev. 3, 162–187. doi: 10.1016/j.plrev.2006.07.001

Dill, L. M. (1987). Animal decision making and its ecological consequences: the future of aquatic ecology and behaviour. Can. J. Zool. 65, 803–811.

Doherty, T., and Driscoll, D. A. (2017). Coupling landscape and movement ecology for species conservation in production landscapes. Proceedings B, 285:20172272. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2017.2272

Duning, J. B. (1995). Spatially explicit population models: current forms and future uses. Ecol. Appl. 5, 3–11. doi: 10.2307/1942045

Duriez, O., Bauer, S., Destin, A., Madsen, J., Nolet, B. A., Stillman, R. A., et al. (2009). What decision rules might pink-footed geese use to depart on migration? an individual-based model. Behav. Ecol. 20, 560–569. doi: 10.1093/beheco/arp032

Eliassen, S., Snorre, B., Jørgensen, C., and Giske, J. (2016). From sensing to emergent adaptations: modelling the proximate architecture for decision-making. Ecol. Model. 326, 90–100. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolmodel.2015.09.001

Fawcett, T. W., Hamblin, S., and Giraldeau, L. A. (2013). Exposing the behavioral gambit: the evolution of learning and decision rules. Behav. Ecol. 24, 2–11. doi: 10.1093/beheco/ars085

Feng, Z., Liu, R., DeAngelis, D. L., Bryant, J. P., Kielland, K., Chapin, F. S., et al. (2009). Plant toxicity, adaptive herbivory, and plant community dynamics. Ecosystems 12, 534–547. doi: 10.1007/s10021-009-9240-x

Ferno, A., Pitcher, T. J., Melle, W., Nøttestad, L., Mack, S., Hollingworth, C., et al. (1998). The challenge of the herring in the Norwegian Sea: making optimal collective spatial decisions. Sarsia 83, 149–167.

Flierl, G., Grünbaum, D., Levins, S., and Olson, D. (1999). From individuals to aggregations: the interplay between behavior and physics. J. Theor. Biol. 196, 397–454.

Fretwell, S. D., and Lucas, H. L. (1969). On territorial behavior and other factors influencing habitat distribution in birds. Acta Biotheor. 19, 16–36.

Gautestad, A. O. (2016). Animal Space Use: Memory Effects, Scaling Complexity, and Biophysical Model Coherence. Indianapolis, IN: Dog Ear Publishing.

Giske, J., Eliassen, S., Fiksen, Ø., Jakobsen, P. J., Aksnes, D. L., Jørgensen, C., et al. (2013). Effects of the emotion system on adaptive behavior. Am. Nat. 182, 689–703. doi: 10.1086/673533

Gorban, A. N., and Çabukoglu, N. (2018). Mobility cost and degenerated diffusion in kinesis models. Ecol. Compl. 36, 16–21. doi: 10.1016/j.ecocom.2018.06.007

Graf, R. F., Kramer-Schadt, S., Fernandez, N., and Grimm, V. (2007). What you see is where you go? Modeling dispersal in mountainous landscapes. Landscape Ecol. 22, 853–866. doi: 10.1007/s10980-006-9073-3

Grimm, V., and Railsback, S. (2005). Individual-Based Modeling and Ecology. Princeton: University Press. 241–247.

Grünbaum, D. (1999). Advection-diffusion equations for generalized tactic searching behaviors. J. Math. Biol. 38, 169–194. doi: 10.1007/s002850050145

Gueron, S., Levin, S. A., and Rubenstein, D. I. (1996). The dynamics of herds: from individuals to aggregations. J. Theoret. Biol. 182, 85–98. doi: 10.1006/jtbi.1996.0144

Gunn, D. L., and Fraenkel, G. S. (1961). The Orientation of Animals: Kineses, Taxes, and Compass Reactions. New York, NY: Dover Publications, Inc.

Hamblin, S. (2013). On the practical usage of genetic algorithms in ecology and evolution. Methods Ecol. Evol. 4, 184–194. doi: 10.1111/2041-210X.12000

Hampton, S. E., Strasser, C. A., Tewksbury, J. J., Gram, W. K., Budden, A. E., Batcheller, A. L., et al. (2013). Big data and the future of ecology. Front. Ecol. Environ. 11, 156–162. doi: 10.1890/120103

Hancock, P. A., Milner-Gulland, E. J., and Keeling, M. J. (2005). An individual based model of bearded pig abundance. Ecol. Model. 181, 123–137. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolmodel.2004.06.026

Hemelrijk, C. K., and Kunz, H. (2005). Density distribution and size sorting in fish schools: an individual-based model. Behav. Ecol. 16, 178–187. doi: 10.1093/beheco/arh149

Hoare, D. J., Couzin, I. D., Godin, J. G. J., and Krause, J. (2004). Context-dependent group size choice in fish. Anim. Behav. 67, 155–164. doi: 10.1016/j.anbehav.2003.04.004

Houston, A. I., and McNamara, J. M. (1999). Models of Adaptive Behaviour: An Approach Based on State. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Humston, R., Olson, D. B., and Ault, J. S. (2004). Behavioral assumptions in models of fish movement and their influence on population dynamics. Trans. Am. Fish. Soc. 133, 1304–1328. doi: 10.1577/T03-040.1

Huse, G., Strand, E., and Giske, J. (1999). Implementing behaviour in individual-based models using neural networks and genetic algorithms. Evol. Ecol. 13, 469–483. doi: 10.1023/A:1006746727151

Huth, A., and Wissel, C. (1992). The simulation of the movement of fish schools. J. Theoret. Biol. 156, 365–385. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5193(05)80681-2

Kanagaraj, R., Wiegand, T., Kramer-Schadt, S., and Goyal, S. P. (2013). Using individual-based movement models to assess inter-patch connectivity for large carnivores in fragmented landscapes. Biol. Conserv. 167, 298–309. doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2013.08.030

Kanarek, A. R., Lamberson, R. H., and Black, J. M. (2008). An individual-based model for traditional foraging behaviour: investigating effects of environmental fluctuation. Nat. Res. Model. 21, 93–116. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-7445.2008.00002.x/full

Krause, J., Hoare, D., Krause, S., Hemelrijk, C. K., and Rubenstein, D. I. (2000). Leadership in fish shoals. Fish Fish. 1, 82–89. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-2979.2000.tb00001.x

Krause, J., Ruxton, G. D., and Krause, S. (2010). Swarm intelligence in animals and humans. Trends Ecol. Evol. 25, 28–34. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2009.06.016

Landsrød, L. R. (2017). Decision-Making in a Proximate Model Framework: How Behavior Flexibility is Generated by Arousal and Attention. Master of Science in Biology. Department of Biology, University of Bergen, Bergen, Norway.

LeDoux, J. (2012). Rethinking the emotional brain. Neuron 73, 653–676. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.02.004

Lek, S., and Guégan, J. F. (1999). Artificial neural networks as a tool in ecological modelling, an introduction. Ecol. Model. 120, 65–73. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3800(99)00092-7

Lewison, R. L., and Carter, J. (2004). Exploring behavior of an unusual megaherbivore: a spatially explicit foraging model of the hippopotamus. Ecol. Model. 171, 127–138. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3800(03)00305-3

Lima, S. L. (2002). Putting predators back into behavioral predator–prey interactions. Trends Ecol. Evol. 17, 70–75. doi: 10.1016/S0169-5347(01)02393-X