- 1Environmental Science and Policy Program, Michigan State University, East Lansing, MI, United States

- 2School of Criminal Justice, Michigan State University, East Lansing, MI, United States

- 3Department of Geography, Environment, and Spatial Sciences, Michigan State University, East Lansing, MI, United States

- 4Department of Public Health, University of Otago, Wellington, Wellington, New Zealand

- 5Department of Fisheries and Wildlife, Michigan State University, East Lansing, MI, United States

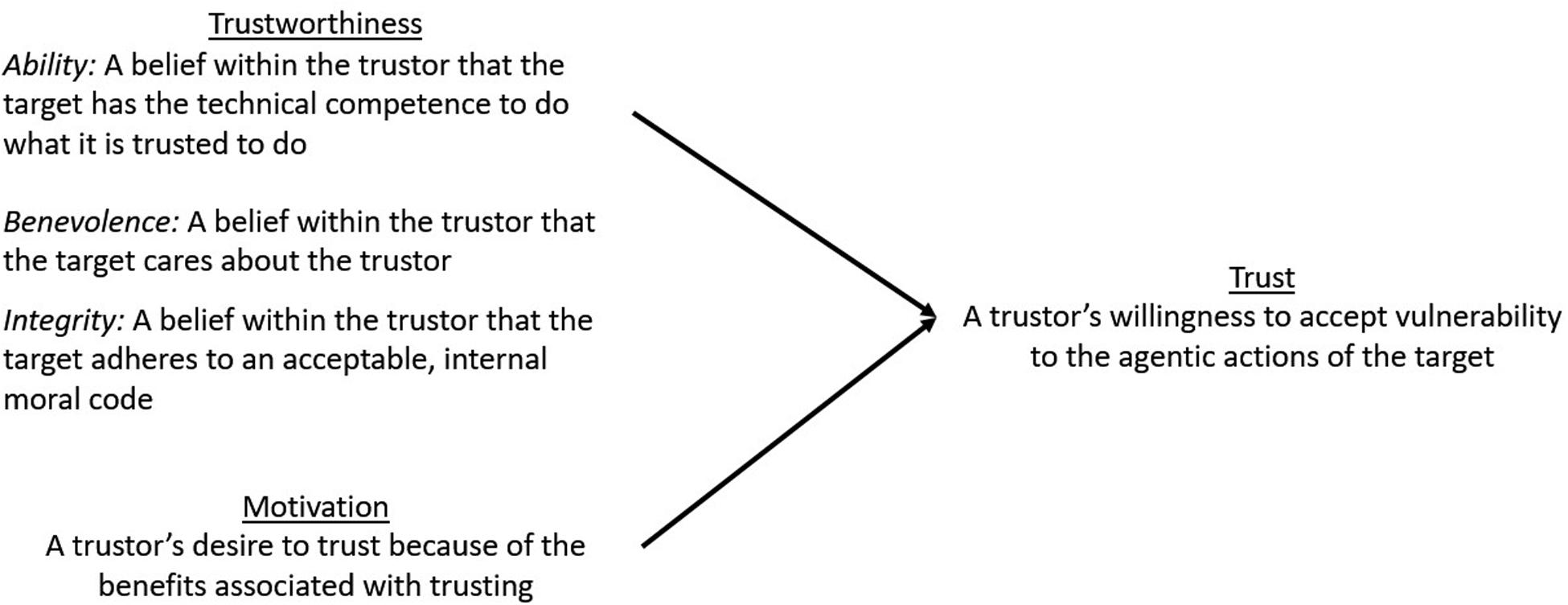

Discipline and context specific inquiries into the nature and dynamics of trust are beginning to give way to cross-boundary understandings which seek to outline its more consistent elements. Of particular note within these is an argument that trust is premised on vulnerability; that it has an important nexus with assessments of the ability, benevolence, and integrity of the trust target; and that it can also be motivated. The current work seeks to shed preliminary light on the applicability of this argument to a context in which it has not previously been examined: community-based water management in southwestern Uganda. Using a deductive, theory-driven analysis of focus group discussions with residents, we show that when our participants were simply asked to discuss their relationships with local management committees, vulnerability, ability, benevolence, and integrity consistently emerged as salient themes. Motivation, however, emerged as most salient for women. Further analysis suggests that this may have been because women are more directly involved in water provision, thereby increasing their perceived need for the resource. Our results, therefore, lend credence to the cross-boundary nature of this increasingly nuanced theoretical understanding of trust but also suggest some general guidance for improving community-based resource management efforts by providing preliminary evidence regarding the relative roles of trustworthiness and motivation.

Introduction

Understanding the nature and dynamics of trust is an important goal of an ever-growing body of scholarly and practical efforts. Hardin (2001) argues that trust always involves three elements—a trustor (A), a target of that trust (B), and the context in which the relationship between A and B occurs—such that changes in any one of these elements fundamentally change the trust at issue. Trust is therefore often understood to be specific to not only the individuals involved but also to the specific context in which their relationship is situated. This particularity has fostered a fragmented literature such that scholars interested in a given relationship tend to focus on only that relationship and typically from the perspective of their own disciplinary lenses (e.g., the study of government and the governed in political science, the study of the police and their communities in criminal justice, the study of news media and its consumers in communication). Recently, however, increasing attention is being paid to working across these boundaries to identify the elements of trust that are or are not consistent (Hamm et al., 2016a). The current research builds upon this work, focusing on three elements of trust that have been supported in a wide variety of contexts to understand their applicability to a new context of significant practical import, that of community-based water management in southwestern Uganda. Specifically, we seek to understand whether the themes that emerge from focus group discussions (FGDs) about trust in the committees responsible for managing community boreholes are consistent with the postulation that cross-boundary trust is premised on vulnerability, that it has an important nexus with assessments of the ability, benevolence, and integrity of the target, and that it can also be motivated.

Cross-Boundary Trust

Trust is a critical construct for a wide variety of relationships. Scholars in disciplines from anthropology (e.g., Hewlett et al., 2000) to zoology (e.g., Metcalfe, 1984) have considered the construct, typically using approaches particular to their own disciplinary or contextual paradigm. As a result, there exists a wide variety of conceptualizations and operationalizations, but an increasing body of scholarship has sought to work across these boundaries to build an understanding of the nature and dynamics of trust itself. Within this work, trust is typically understood as the trustor’s willingness to accept their vulnerability to the target of that trust (Mayer et al., 1995; Rousseau et al., 1998; Hamm et al., 2016a). Scholars generally suggest that this vulnerability arises from interdependencies within the relationship between the trustor and the target such that the target’s decisions have the potential to meaningfully impact the trustor (PytlikZillig and Kimbrough, 2016; see also Balliet and Van Lange, 2013). Indeed, for some this vulnerability to harm comprises a “fundamental human dilemma” such that within all interactions, there is some potential for harm rooted in the agentic—that is, deliberate (see Bandura, 1986)—actions of the other (Lind, 2001, p. 61; see also Misztal, 2012). Trust then refers to a psychological state within the trustor that is characterized by a willingness to accept vulnerability to harms that range from disappointment or mild embarrassment to direct, intentional, physical harm. It is for this reason that trust has been called a “social lubricant” (Dasgupta, 2000, p. 64) that facilitates relationships from the interpersonal (Rotter, 1971) to the international (Haukkala et al., 2015).

This postulated role of trust has made a sophisticated understanding of the processes by which it can be increased and maintained particularly important. Scholars working on close, interpersonal relationships (e.g., Rempel et al., 2001); small, temporary groups (e.g., Meyerson et al., 1996); and large, international institutions (e.g., Arnold et al., 2012) have all expended considerable energy in working to identify trust’s most critical antecedents. Most of these can be grouped into a broader notion of trustworthiness—that is, the trustor’s evaluations of the characteristics of the target that make it more or less worthy of being trusted (see Sharp et al., 2013). These multidimensional assessments include constructs like encapsulated interests, benevolence, confidence, shared values, reliability, and so on. Despite their conceptual and statistical distinctiveness, research investigating them suggests that they typically cohere strongly such that it is not usually necessary to capture all of them at a given point in time (PytlikZillig et al., 2016). Instead, this scholarship suggests that three specific evaluations typically account for the bulk of the variance in trustworthiness assessments. Paralleling arguments from the psychology of impression formation (i.e., warmth and competence; Fiske et al., 2007) and the sociology of trust (i.e., competence and fiduciary responsibility; Barber, 1983), this research suggests that trustworthiness evaluations can be captured by assessing the extent to which the trustor believes that the target has the technical ability to do what it is being trusted to do (i.e., ability), cares for the interests of the trustor (i.e., benevolence), and adheres to an internal moral code that the trustor finds acceptable (i.e., integrity; see Colquitt et al., 2007).

These assessments of trustworthiness have received primary emphasis in contemporary trust scholarship, but this perspective is not without criticism (e.g., Zand, 1972; Li, 2008; McEvily, 2011). These critiques generally acknowledge the importance of trustworthiness as one antecedent but stress that trust must be something more than a simple calculation of the probability of harm as deduced from these evaluations of the other (Möllering, 2001, 2014). Often focusing on what has been called trust-as-choice, some have suggested that trust may, under some circumstances, more directly represent a deliberate choice on the part of the trustor motivated by a desire for some benefit (Li, 2015; Hamm, 2017; van der Weff et al., 2019). Research has begun to provide evidence for the importance of this motivation in a variety of governance contexts (e.g., Shepherd and Kay, 2012; Mislin et al., 2015; Shockley and Fairdosi, 2015) and work on invasive species management in the United States specifically has shown a belief that a management agency provides a valued benefit (e.g., by providing someone to call if the trustor has a problem) to be an important predictor of trust-based cooperation (Hamm, 2017). This work further suggests that a motivated choice to trust could occur in the absence of trustworthiness information or, more interestingly, in the face of a perception that the target is not trustworthy.

Community-Based Water Management

Taken together, this literature suggests that vulnerability, trustworthiness, and motivation may be important parts of a cross-boundary understanding of trust and the current work sought to evaluate this argument in the context of community-based water management in southwest Uganda. Water is an essential component of human security and sustainable development. In recognition of this, significant effort has been expended to promote reliable access to safe water and to reduce household water instability. Throughout much of sub-Saharan Africa, reliable access to adequate clean water varies considerably, especially in rural villages, some of which have relatively high access to improved sources while others have virtually none (de Albuquerque, 2012). For those without this access, seasonal variation in water availability creates significant challenges that have been shown to force individuals to switch primary water sources across and even within seasons, often with great negative consequence to livelihoods (Pearson et al., 2016). Climatic factors further compound water insecurity by exacerbating unpredictable rainfall patterns and evaporation of surface water which even further reduce the effectiveness of existing coping strategies (Pearson et al., 2015). Additionally, these pressures are unlikely to be equally felt across individuals within these communities and may, therefore, serve to intensify existing disparities.

Most extant efforts to address water insecurity highlight biophysical challenges like water availability, rainfall, affordability, and water quantity/quality (Soares et al., 2002; Howard and Bartram, 2003; WHO/UNICEF, 2012; Yang et al., 2013; Bain et al., 2014; Jepson, 2014), but it is generally well understood that it is at least as important to address the role of the social context (United Nations, 2015; Wutich et al., 2017). The management of water is inherently social (Rinkus et al., 2016) and its dynamics vary considerably between regions and even within sub-national units. In the sub-Saharan context, local (village-level) committees are typically most directly responsible for the management of water resources and related infrastructure, usually public borehole wells with pump handles (e.g., Adams and Zulu, 2015). These committees’ duties vary but they are generally responsible for ensuring that the borehole continues to function properly by collecting and deploying community funds.

The public value in these committees, therefore, lies in their ability to collect and deploy more resources than are available to individuals but this purpose carries with it the possibility for abuse. As in most cooperative situations (see Misztal, 2012; Balliet and Van Lange, 2013), the interdependence of these actors creates the potential for harms that run from well-meaning but ultimately wasteful uses of community funds to intentional malfeasance. Trust is therefore important because it serves as a mechanism by which community members are able to acknowledge the potential for these harms and yet cooperate (Möllering, 2001, see also Nienaber et al., 2015; Hamm et al., 2016b). When trust is low, however, these vulnerabilities likely complicate and may even preclude cooperation, thereby undermining these committees’ ability to ensure access to safe drinking water.

The Current Study

A limited body of scholarship has investigated the nature and role of trust in this sustainable development context, but it has generally taken a relatively unsophisticated approach to the construct. Typically, this research focuses on imprecise, general notions of trust or related concepts like social capital, the antecedents of which are generally specific to the context and relationships studied (e.g., van Rijn et al., 2012; Venot and Clement, 2013). As a result, it is somewhat difficult to understand how these findings might translate across boundaries. The current research analyzes qualitative data collected from community residents to understand the fit of this cross-boundary understanding of trust and its antecedents to the experiences of our participants. We therefore took a deductive approach, postulating that our participants’ experiences would be consistent with an understanding of trust as a willingness to accept vulnerability and that this willingness would flow, not only from assessments of ability, benevolence, and integrity, but also from a motivation that arises from a desire for the benefits associated with trusting (see Figure 1). To be sure, this theory-driven approach does complicate the definitiveness of this test in that it lacks the benefits of quantitative theory-testing or qualitative theory-building (see Collins and Stockton, 2018). We argue, however, that such an approach provides important preliminary evidence regarding the extent to which ability, benevolence, integrity, and motivation are thought, by participants, to be relevant in the face of a salient vulnerability controlled by another. Thus, our work contributes to the literature an initial evaluation of the applicability of these postulated elements of a cross-boundary understanding of trust and its salient drivers to a new context. We further this contribution, however, by rooting this investigation in a practically important context and thereby provide preliminary evidence from which future efforts can draw when seeking to address cooperation with community-based resource management.

Materials and Methods

This research was conducted in the Kiruhura District of Uganda in the summer of 2016. One village (Rwamuhuku) was selected due to one of the author’s extensive previous experience and knowledge of both existing water sources and the regional history of water management (Pearson and Muchunguzi, 2011). Within Rwamuhuku village, there are two sub-villages. One sub-village (also called Rwamuhuku) has a population of approximately 300 households, a trading center, and is home to a main road servicing Lake Mburo National Park. By contrast, the other sub-village (called Minekye) has approximately 40 households and is more sparsely populated. Each sub-village contains one community-owned borehole that was constructed by the Ugandan government. The older borehole was constructed in 1987 in Rwamuhuku was identified by our participants as more reliable and providing a higher quality of water (i.e., better tasting and clearer appearance) than the newer one which was constructed in 2011 in Minekye. Other research on water quality in this district suggests that boreholes like these are often, but not always, free of Escherichia coli (Pearson et al., 2008). Both boreholes are managed via separate committees whose members are selected as needed by sub-village residents. The nomination and confirmation processes are generally informal but typically include some consideration of how well the individual is known in the community, how trustworthy they are, and their social values. The committees’ major function is to protect, maintain, and—as needed—repair the boreholes through community fees which are solicited on an ad hoc basis.

Sampling

Focus group discussion (FGD) participants were sampled from the Rwamuhuku village registry. We identified the following participant characteristics as relevant to our research questions: age, gender, ethnicity, and sub-village. We then purposively recruited participants to ensure representation in each stratum (Palinkas et al., 2015).

Focus Group Discussions

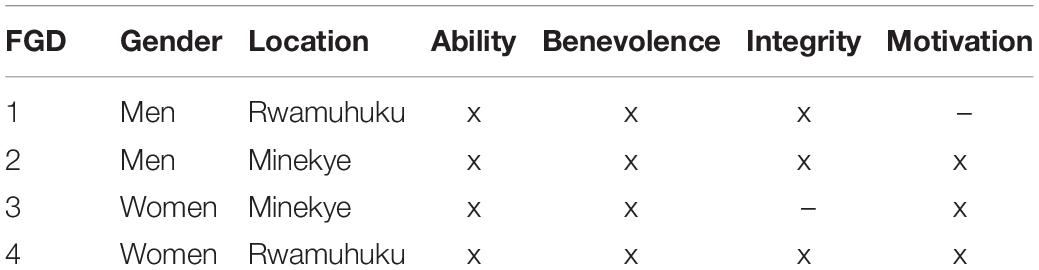

Two FGDs were carried out in each sub-village (k = 4; see Table 1). To increase participants’ willingness to speak freely, groups were conducted separately for male and female participants (Krueger, 2014). The FGDs were conducted in the native language of the participants (Runyankole) by a female research assistant who has worked closely with this community in previous research and is a native speaker. The FGDs occurred on separate days in one of the classrooms at the only school in Rwamuhuku which is roughly equidistant from the two sub-villages. The FGDs were semi-structured, relying on an interview guide with open-ended topics, and responses were probed by the facilitator (Drever, 1995). The interview guide (see Supplementary Material) began with questions about water access for household use during the wet and dry seasons. Participants were next asked about their awareness, use, and experiences with the two boreholes. We then asked about the management of the boreholes and probed in detail regarding the borehole committees, their trustworthiness, responsibilities, and effectiveness. The FGDs lasted an average of 65 min (min = 40; max = 90).

The FGDs were recorded using a digital voice recorder. Audio files were translated into English and transcribed directly by the research assistant. Two researchers then reviewed the transcripts independently and coded them for the three primary themes: vulnerability, trustworthiness dimensions, and motivation. The passages were then re-reviewed by the first author and analyzed for content.

Human Subjects Approval

All study procedures were reviewed and approved by the Michigan State University Human Research Protection Program (IRB x15-836e), the Mbarara University of Science and Technology Institutional Review Board (MUREC 1/7 No. 06/04-16), and the Uganda National Council of Science and Technology (Ps 41).

Results

Twenty-nine residents (15 men and 14 women) between the ages of 27 and 60 (average age was 40.3 years) participated in the FGDs. Twelve participants belonged to the Bahima ethnic group and seventeen to Bairu. All participants reported using the boreholes as their primary source of water for drinking, cooking, and bathing in both wet and dry seasons. Regarding general household use, 18 participants reported relying primarily on water from the Rwamuhuku borehole and 11 on the Minekye borehole. Importantly, however, all participants reported that they prefer to get water for drinking from the Rwamuhuku sub-village borehole because of its higher perceived quality.

Vulnerability

To evaluate the fit of our account of trust to this context we first assessed whether participants’ discussions revealed a salient vulnerability in cooperating with the committees. As discussed above, the responsibility of each sub-village’s borehole committee was to handle all issues related to the management of the resource. Participant discussions revealed that this included specific responsibilities like ensuring cleanliness and order at the site itself but arranging for repair appeared to be most salient. Participants reported that borehole repairs were paid for with money collected from the community by the committee. All participants reported that, at one time or another, they had been asked to contribute some amount of money to the repair of the borehole(s) that they use, ranging from 2,000 to 10,000 Ugandan shillings (about $0.60 to $3.00 when the study was conducted). Participants also reported that the amount paid varied across community members and that some, especially the very poor and elderly, could be exempted from paying.

As expected, this collection of funds created a salient vulnerability for FGD participants. Indeed, the concern of misused money meant for borehole repairs was a common theme that emerged throughout the discussions. Participants reported that some individuals in both communities were known to refuse to cooperate specifically because they did not trust the committee members with the money. Although it was difficult to determine the number of discrete events, there were numerous reports that committee members had stolen or misused funds collected from the community, especially in the Rwamuhuku sub-village. A woman from Rwamuhuku (P5FGD4) noted…

We do not trust them because recently they collected money and the chairman of the borehole committee stole the money and the borehole was never repaired.

A man from the Minekye sub-village (P5FGD1) similarly highlighted the issue in discussing a belief that committee members view the breaking down of the borehole as personal financial opportunity.

The committee members use the breaking down of the borehole as an opportunity to make money and benefit from the community people who contribute for its repair… These leaders go about in the village collecting money, about 10,000 Ugandan shillings [$3.00] per household, the person will raise about 1,500,000 shillings [about $450.50] yet the borehole only requires 700,000 shillings [about $210.00] for repair and the remaining 800,000 shillings [about $240.00] is pocketed by the members of the committee… They never keep that money so that in case the borehole breaks down again, they can repair it… All the leaders want is to collect a certain amount of money where they can make money for their pockets/personal gains.

A man from Rwamuhuku who had served on a borehole committee (P5FGD2) elaborated on this vulnerability, suggesting that it was a major driver in subsequent refusals to cooperate which, in turn, often delayed the repair process.

The problems start when I go to the community to collect money and after 2 weeks, the borehole breaks down yet the money that was collected the first time did not do anything. So, when we go back the second time to collect the money, that is when the people start to complain and they tell us they are tired of us. They always tell us that we steal their money and then we come lying to them that the borehole broke down again.

Many participants felt that the borehole in Minekye was managed better. Following the dissolution of what appeared to be an ineffective committee, the participants argued that the current Minekye committee was more effective. One woman from Minekye (P5FGD3) noted:

The chairman that we selected in Minekye is very responsible because the moment we tell him the borehole has broken down, he ensures that the committee comes together, they collect money in order to have the borehole repaired.

This perception of greater effectiveness among participants was often coupled with a perception that there was a reduced likelihood that funds collected for repair would be misused. A woman from Rwamuhuku (P5FGD4) noted that when money is collected for repair,

They use some of the money they have collected to repair it and the rest is kept for the future in case it breaks down again.

This relatively better situation was typically attributed by participants to the very different community composition. A woman from Minekye (P4FGD3) focused specifically on the fact that her community was relatively smaller and that its residents were typically more connected to the community when she noted,

We also know each other which is not the case with the people in Rwamuhuku. They have many youthful people and most of them migrated here from different regions. So, it is very hard for them to work together for the common good.

Trustworthiness Themes

Our analysis moved next to evaluate the major reasons why a community member would (or would not) be willing to accept this vulnerability and cooperate. Regarding trustworthiness, the committee’s capacity to perform their responsibilities as expected (ability) emerged as salient and the majority of these comments were made in the context of the relatively greater ability of the committee in Minekye. A man from Minekye (P5FGD1) suggested that, unlike Rwamuhuku, the committee in his sub-village was made up of individuals who had the technical capacity to manage.

The borehole committee in Minekye has about five people and they understand how to deal with finances properly.

A woman from Minekye (P1FGD3) echoed and expanded on this, suggesting that the committee’s relatively higher degree of ability in Minekye was the result of a community that was generally more competent.

But when our borehole here breaks down, most of us here know what to do, that is why the borehole is always repaired in time.

The comments regarding ability that were not directed to the committee in Minekye tended to focus on the relatively low perceived ability of the Rwamuhuku borehole committee. A man from Rwamuhuku (P7FGD3) addressed a specific individual within the committee noting:

[redacted name] was put as an advisor and he stopped being one on that day; he does not even know the responsibility that was assigned to him.

A man from Rwamuhuku (P5FGD2) suggested that this lack of ability flowed from a lack of education saying,

Most people we select are not educated so they do not know why they have been selected and what their responsibilities are. We pick those who are asleep and they do not know what to do.

Participants also addressed the committees’ benevolence—that is, their care for the communities they serve. Unlike those regarding ability, most of these comments were negative and although there were discussions of a lack of benevolence regarding both committees, they were more pronounced in Rwamuhuku. A woman from Rwamuhuku (P3FGD4) highlighted this general concern, arguing that her chairman didn’t care enough to act when individuals visiting the boreholes were threatened.

Even if you reported to the chairman, what would he do? He is also not serious like his committee members.

A woman from Rwamuhuku (P6FGD4) echoed this perceived lack of care for the community, suggesting that her committee chairman was only visible when asking for funds for a repair.

Whenever the borehole breaks down and he [the chairman] is asking for money, he really works so hard and tries to show us that he is making a lot of effort. But after, you can never see him again.

Benevolence concerns in Minekye, although less common, were very similar. For example, a man from Minekye (P5FGD1) argued that his committee also did not care about the needs of the community and was only interested in money.

You see every committee we select; they are only interested in money. They do not mind about the lives of the people.

Other responses offered further insight into these benevolence concerns, suggesting that the reason that the committees didn’t care was because their members didn’t share the experiences and values of the wider community. A man from Minekye (P5FGD1) directly compared the two communities and argued that the relatively lower perceived concern for the community in Rwamuhuku came from the diversity of origins of its committee’s members.

But in Rwamuhuku, we have all sorts of people, some committee members are even immigrants. So, such people know they won’t be in this community for long and are not ashamed to steal our money.

Another participant, a woman from Minekye (P4FGD3) argued that gender played an important role in care when she noted;

Most of the committee members are men; when they go home, they just find food ready; they do not care about where the wife fetched the water.

Finally, participant responses also addressed perceptions of integrity—that is, adherence to an acceptable internal code of conduct. Again, comments were directed at both committees but were more negative in Rwamuhuku. A woman from Minekye (P1FGD4) noted that her lack of trust in the committee was driven by their dishonesty in managing the community’s repair funds.

They are just dishonest. They refunded their friends and those people who are very tough in the community. But for us the women, they ignored us because they know we cannot fight for the money.

In one of the sessions, participants discussed a situation in which a committee member had stolen replacement parts. A man from Minekye (P5FGD1) recounted;

I know someone who was given the responsibility of storing some of the borehole equipment… pipes and some chains for the borehole. There are pipes that were removed from the borehole and he was told to store them. We later discovered that this person sold off the equipment and never accounted for the money.

A fellow participant, a man from Rwamuhuku (P1FGD1), went on to say that this integrity violation had resulted in the entire committee’s dissolution.

Every committee member knew what was going on. That is why that person was not dismissed by the other committee members so as the community, we decided to dissolve the whole committee because we cannot trust them with more of our money.

Fewer integrity concerns were noted regarding Minekye but what was most noteworthy was the suggestion that this may be short-lived. A woman from Rwamuhuku (P5FGD4) addressed the committee in Minekye saying that the reason that its committee was able to better manage the water is simply that:

…their leadership has not been corrupted yet.

Motivation Themes

Although ability, benevolence, and integrity appeared to be somewhat challenged overall, it was clear that participants felt that their communities often accepted the potential for harm and paid. In fact, despite the salient discussion of a lack of trustworthiness in Rwamuhuku noted above, cooperation generally appeared to be normative in both communities. Discussions of this non-payment were typically couched in terms of what “some” people do and often explicitly noted that many of those individuals who do not pay, could not pay. A woman from Minekye (P4FGD4) said:

…some people pay that money but others do not because they cannot afford that money.

In response to a direct question about whether people fail to pay for reasons other than that they are unable, a woman from Minekye (P1FGD3) succinctly answered “no.” Other participants, however, indicated that refusal to pay when the individual, at least in their opinion, should be able to pay does happen. It was also suggested that there may have been periods during which greater percentages of the community refused to cooperate but the discussions regarding the situation now tended to suggest that this was abnormal. In one case it even seemed that these offenders could be identified by name. A woman from Rwamuhuku (P5FGD4) noted;

Some people just refuse to pay. They just don’t make any effort to pay but there are those people who refuse to pay like the wife of [name redacted].

Review of the transcripts suggested that participants were often willing to cooperate, in large part because of a need for the water itself. A woman from Minekye (P1FGD4) addressed this directly saying:

We do not trust them, most of the time we are just desperate and all we want is to get water, so we have to pay the money.

Reporting this need for the resource appeared to vary by gender. Only one man (P4FGD2) addressed this motivation at all and then only in passing. In the focus groups with women, however, the discussion was more sustained. In both communities, it was clear that, as in much of rural sub-Saharan Africa (World Bank, 2006), water collection responsibilities typically fell to the women. The women in our FGDs suggested that this relatively greater familiarity with the difficulties in accessing water when the boreholes are not working created a greater sensitivity to requests for repair funds. A woman from Minekye (P6FGD3) addressed this saying;

Sometimes when we have not paid the money and we tell them [men/husbands] that we have been sent away from the borehole, the man will say “why don’t you try the other sources like the wells.” To avoid such, the women just get the little money they had saved for other needs like food and pay for the borehole.

One participant, a woman from Minekye (P4FGD3) went so far as to suggest that payment may generally be more likely to come from women, specifically because of this relatively greater motivation.

It is the women who contribute the money because they are the ones who know the pain of trying to access water.

Discussion

The emergent themes within the data tracked well with our expectations regarding cross-boundary trust. As expected, cooperating with committee requests for funds posed a salient vulnerability to participants. It was clear that participants generally understood that providing money to the borehole committees empowered the committees to make decisions regarding those funds that could (and did) include mismanagement and malfeasance and that those outcomes constituted a salient harm. Additionally, although non-payment seemed to primarily occur because of an inability to pay, participants directly connected the decision to pay to an assessment of the probability of harm.

Participants in all four FGDs noted this risk but it was clear that the potential for harm was more significant in Rwamuhuku than Minekye, at least when the FGDs were conducted. The primary reason for this in the minds of our participants was a pervasive belief that the committee in Minekye was less likely to misuse the funds but participants offered various explanations for that assessment. Some pointed to relatively greater ability in Minekye, while others argued that the greater homogeneity and longer average resident tenure meant that the committee members cared more for their community. Integrity was not addressed as a salient driver of this relatively lower vulnerability but given that integrity was strongly connected to misuse of the funds in Rwamuhuku, it stands to reason that the committee in Minekye may have been more positively perceived on this evaluation as well.

Interestingly, a willingness to cooperate appeared to be normative despite a pervasive vulnerability that—although reduced in Minekye—was present in both communities. Throughout the conversations, participants reported a general willingness to accept their vulnerability to the committees even though some did so while explicitly expecting to be harmed. It is important to note that the focus group context may have created a pressure on participants to not report their own failures to pay but it should also be noted, that the participants did not suggest that other people tended to fail to pay which would have been expected if non-payment was normative and individuals were simply trying to hide their own lack of cooperation. Instead, incidents of non-payment seemed relatively isolated and tended to focus on situations in which the individual could not pay.

Our analysis sheds some light on the reasons why participants were willing to accept this vulnerability and, as would be expected, the hypothesized subthemes of ability, benevolence, and integrity emerged as salient antecedents in the discussions but only ability and benevolence appeared in all four FGDs (see Table 1). Most of these trustworthiness mentions focused on the relatively greater ability in Minekye as compared to Rwamuhuku. Benevolence was also a major theme in the discussions and although these comments were primarily negative in both communities, they were discernably more negative regarding Rwamuhuku and were typically rooted in its relatively greater community heterogeneity. Integrity was only discussed in three FGDs (was not addressed in FGD3) and these discussions usually focused on a lack of honesty or a willingness to treat demographic groups disparately. Thus, our work suggests that these specific three subconstructs of trustworthiness are salient enough to be highlighted by participants who are simply asked to discuss the trustworthiness of a local water management committee. Deeper evaluation of our data may suggest that this salience is moderated such that when things are relatively positive, as in Minekye, ability is most salient. When they are more negative, as in Rwamuhuku, benevolence and—to some extent—integrity appeared to become more salient, but the limited nature of the current data mean that this is largely speculative. Future research is needed to confirm this.

Motivation was less discussed in the meetings with only one passing reference in a FGD with men (FGD2). Female participants, however, consistently noted that individuals were often willing to accept vulnerability, at least in part, because of a need for the water. Given the cost of repairing the boreholes and their prominence within the community as a source of water, especially during the dry season, the committees appeared to be the only viable option for access when repairs were needed.1 Participants explicitly suggested that, because procuring water typically falls to women in these communities, they experience greater motivation than do the men. It was even suggested that when community members do cooperate with the requests for funds, the individual who pays is more likely to be a woman. This suggests that motivation may have been more salient for women than men but leaves open at least two possibilities regarding this differential salience. As noted by the participants, women’s typical responsibilities regarding water likely make the need for the resource more important for them but it is unclear whether this motivation was also an important driver for men that was simply less salient, or if its importance was weaker. No previous work assessing motivation as an antecedent of trust has reported differences by gender, but it should be noted that these studies have not typically directly addressed this question. Nonetheless, it does stand to reason that motivation would be more important when the need is more salient and, in this community, that salience was clearly gendered.

Implications for Community-Based Water Management

Taken together, our results provide support for our postulation that cooperating with requests for funds from committees responsible for managing water created a salient vulnerability that ability, benevolence, integrity, and motivation likely have roles to play in assuaging, at least for our participants. In our data, all four themes were explicitly connected to a willingness to accept vulnerability by participants who indicated that low ability, benevolence, and—to some extent—integrity inhibit that willingness while high motivation facilitates it. This matters for future efforts to improve local water management because it may suggest the existence of two, independent pathways to cooperation through trust. Our analysis lends credence to the argument that fostering a willingness to accept vulnerability does matter for increasing cooperation and that evaluations of the water management committee’s ability, benevolence, and integrity are important such that when they are relatively more positive, the willingness to accept vulnerability is greater.

Importantly, however, these assessments seemed to be objectively low in our discussions. In fact, even when participants were relatively more positive, they were quick to note that previous committees were less trustworthy and to suggest that currently trustworthy committees may yet be corrupted. Despite this, however, cooperation appeared high and this suggests that understanding trust and its place in increasing cooperation requires attention to the role of motivation that arises from a need for the resource itself. At its simplest, this requires a recognition that trust does not presuppose trustworthiness. Instead, committees who are low in trustworthiness may yet be able to attain an acceptance of vulnerability with sufficient motivation. More interestingly, however, this may suggest that the willingness to accept vulnerability that is trust itself may be accessible in the absence of trustworthiness. In either case, this matters because it could suggest that successful efforts to provide more reliable access to resources may, paradoxically, reduce cooperation with their management. To the extent that they are able to reduce motivation by making resource provision easier and more reliable, these efforts may remove a driver of cooperation and make trustworthiness—which may be more difficult to sustain in these contexts—all the more important. A failure to attend to this potentiality may render otherwise positive efforts ineffective and, when trustworthiness is low, leave communities worse than they were originally.

Limitations

Despite our belief in the scholarly contribution of this paper, it is important to note three major limitations that arise primarily from its exploratory nature. The first is the use of a relatively small sample in a single community. Although efforts were made to ensure representation of a variety of viewpoints, the reality remains that our conclusions rely on the responses of 29 individuals, leaving open questions of the sufficiency of our data for generalizing beyond our work.

A second important limitation of this work involves its lack of attention to causal influence. Although we can say that our participants believed that trustworthiness and motivation exerted distinct causal influences over their willingness to accept vulnerability, our data are unable to confirm this. Thus, it remains possible that the antecedents may have been influenced by each other or that we may have excluded an important third variable that had the central causal influence. Encouragingly, there is reason to believe that the account presented here is most defensible. Some research does suggest that the primary impact of motivation may be on assessments of trustworthiness (e.g., Shockley and Fairdosi, 2015; see also Williams, 2001), but this did not appear to be the case in our data, especially in Rwamuhuku where participants reported high motivation but low trustworthiness. Regarding the potential third variable problem, our study does neglect a major variable in local culture but it is important to recognize that it was neglected, not because it was not considered by the researchers, but because it was not addressed by the participants. When asked what considerations impacted their cooperation with the committees, no participants argued that they did or did not cooperate because it was their custom to do so or because of social pressure from their neighbors. Although this cannot be taken as evidence that culture and norms do not matter, it does suggest that it was at least not consciously a salient driver of these decisions for our participants.

A third limitation of the current research regards the nexus of trust and cooperation. Trust, as defined here refers to the trustor’s willingness to accept vulnerability to the agentic actions of the target of that trust. This definition explicitly distinguishes trust from cooperation in that trust lies, not in the behavioral acceptance of vulnerability, but in the willingness that facilitates it (see Mayer et al., 1995). Most relevantly, this means that it is possible to cooperate in the absence of trust when, for example, individuals feel they have no alternative. At first blush, this may suggest that the cooperation at the core of this research is distinct of trust, but our data do not suggest that that this cooperation was forced. Participants were clear in arguing that failures to cooperate do happen and did not suggest that these individuals were subjected to sanctions they considered to be important. Instead, our participants appeared to espouse a willingness to take a chance by contributing to these committees, even when they felt that it was likely that their trust would be violated. We, therefore, feel justified in arguing that this cooperation co-occurred with a willingness to accept the potential for harm and, to the extent that this is true, our results remain consistent with the conceptualization of cross-boundary trust presented in the introduction. We note, however, that other methods are needed to more convincingly separate motivated trust from what may simply be motivated cooperation and call on future researchers to consider methodologies that would permit a more rigorous treatment of these related phenomena.

Conclusion

Although not without limitations, our work contributes to the literature preliminary evidence in support of the applicability of a cross-boundary argument regarding the nature of trust that focuses on its nexus with vulnerability, ability, benevolence, integrity, and motivation. Our work cannot be taken as a final word on either this understanding of trust or its applicability to community-based water management in Uganda, but it does provide an important platform for future work. In particular, we highlight a need for quantitative investigations that could use our work as a basis for operationalizing trust, ability, benevolence, integrity, motivation, and cooperation in this context. Our work also offers potential evidence of practical implications. Specifically, our work cautions that well-intentioned efforts to improve community-based resource management that fail to give adequate attention to the balance among cooperation, trust, trustworthiness, and motivation may cause unintended harm.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated for this study will not be made publicly available to protect the anonymity of participants. Requests to access the data can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the Michigan State University Human Research Protection Program (IRB x15-836e), the Mbarara University of Science and Technology Institutional Review Board (MUREC 1/7 No. 06/04-16), and the Uganda National Council of Science and Technology (Ps 41). Written informed consent for participation was not required for this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

Author Contributions

JH, AP, and MG: conception and design. JN: data collection. JH and JN: data analysis. JH: interpretation. JH, AP, JN, and MG: writing.

Funding

This work was supported by Michigan State University through an Interdisciplinary Team Building Initiative award from AgBio Research and the Environmental Science and Policy Program.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Mr. Katungye Lawrence for his permission for participant recruitment and help in securing a venue. We also thank the participants themselves for sharing their experiences. Without them, this work would not have been possible. Finally, we thank Drs. Caitlin Cavanagh, Carole Gibbs, Scott Wolfe, and Adam Zwickle for their feedback and collegial support in developing and presenting the ideas reported here.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fenvs.2020.00047/full#supplementary-material

Footnotes

- ^ In one of the sessions it was mentioned that the local national park and the Ugandan government had provided funds for repair at least once in the past but there was no sense that these contributions could be requested or counted on in the future, or that they would be less susceptible to mismanagement or malfeasance.

References

Adams, E. A., and Zulu, L. C. (2015). Participants or customers in water governance? Community-public partnerships for peri-urban water supply. Geoforum 65, 112–124. doi: 10.1016/j.geoforum.2015.07.017

Arnold, C., Sapir, E. V., and Zapryanova, G. (2012). Trust in the Institutions of the European Union: A cross-country examination. In: Beaudonnet, L., and Mauro, D. D., 2012. Editors. Beyond Euro-Skepticism: Understanding Attitudes towards the EU. (Special Mini-Issue 2 of European Integration Online Papers. Available online at: http://eiop.or.at/eiop/texte/2012- 008a.htm (accessed April 22, 2020).

Bain, R., Cronk, R., Wright, J., Yang, H., Slaymaker, T., and Bartram, J. (2014). Fecal contamination of drinking-water in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med. 11:e1001644. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001644

Balliet, D., and Van Lange, P. (2013). Trust, conflict, and cooperation: a meta-analysis. Psychol. Bull. 139, 1090–1112. doi: 10.1037/a0030939

Bandura, A. (1986). The explanatory and predictive scope of self-efficacy theory. J. Soc. Clin. Psychol. 4, 359–373. doi: 10.1521/jscp.1986.4.3.359

Collins, C. S., and Stockton, C. M. (2018). The central role of theory in qualitative research. Intern. J. Q. Methods 17, 1–10. doi: 10.1177/1609406918797475

Colquitt, J., Scott, B., and LePine, J. (2007). Trust, trustworthiness, and trust propensitY: a meta-analytic test of their unique relationships with risk taking and job performance. J. Appl. Psychol. 92, 909–927. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.92.4.909

Dasgupta, P. (2000). “Trust as a commodity,” in Trust: Making and Breaking Cooperative Relations, ed. D. Gambetta (Oxford: University of Oxford).

de Albuquerque, C. (2012). Report of the Special Rapporteur on the Human Right To Safe Drinking Water And Sanitation. Addendum: Mission to Namibia.

Drever, E. (1995). Using Semi-Structured Interviews In Small-Scale Research: A Teacher’s Guide. Edinburgh: SCRE.

Fiske, S., Cuddy, A., and Glick, P. (2007). Universal dimensions of social cognition: warmth and competence. Trends Cogn. Sci. 11, 77–83. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2006.11.005

Hamm, J. (2017). Trust, trustworthiness, and motivation in the natural resource management context. Soc. Nat. Resour. 30, 919–933. doi: 10.1080/08941920.2016.1273419

Hamm, J., Lee, J., Trinkner, R., Wingrove, T., Leben, S., and Breuer, C. (2016a). “On the cross-domain scholarship of trust in the institutional context,” in Interdisciplinary Perspectives on Trust, eds E. Shockley, T. Neal, L. PytlikZillig, and B. Bornstein (Berlin: Springer International Publishing).

Hamm, J., Hoffman, L., Tomkins, A., and Bornstein, B. (2016b). On the influence of trust in predicting rural land owner cooperation with natural resource management institutions. J. Trust Res. 6, 37–62. doi: 10.1080/21515581.2015.1108202

Hardin, R. (2001). “Conceptions and explanations of trust,” in Trust in Society, ed K. S. Cook (New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation), 3–39.

Haukkala, H., Vuorelma, J., and van de Wetering, C. (2015). Trust in international relations—A useful tool? J. Trust Res. 5, 3–7. doi: 10.1080/21515581.2015.1008009

Hewlett, B. S., Lamb, M. E., Leyendecker, B., and Scholmerich, A. (2000). Internal working models, trust, and sharing among foragers. Curr. Anthropol. 41, 287–297. doi: 10.1086/300135

Howard, G., and Bartram, J. (2003). Domestic Water Quantity, Service, Level And Health. Geneva: World Health Organization.

Jepson, W. (2014). Measuring ‘no-win’ waterscapes: experience-based scales and classification approaches to assess household water security in colonies on the US–Mexico border. Geoforum 51, 107–120. doi: 10.1016/j.geoforum.2013.10.002

Li, P. (2008). Toward a geocentric framework of trust: an application to organizational trust. Manag. Organ. Rev. 4, 413–439. doi: 10.1111/j.1740-8784.2008.00120.x

Li, P. (2015). “Trust as a leap of hope for transaction value: a two-way street above and beyond trust propensity and expected trustworthiness,” in Motivating Cooperation and Compliance with Authority, eds B. Bornstein and A. Tomkins (Cham: Springer International Publishing).

Lind, E. (2001). “Fairness heuristic theory: justice judgements as pivotal cognitions in organizational relations,” in Advances in Organization Justice, eds J. Greenberg and R. Cropanzano (Stanford: Stanford University Press).

Mayer, R., Davis, J., and Schoorman, F. (1995). An integrative model of organizational trust. Acad. Manag. Rev. 20, 709–734. doi: 10.5465/AMR.1995.9508080335

McEvily, B. (2011). Reorganizing the boundaries of trust: from discrete alternatives to hybrid forms. Organ. Sci. 22, 1266–1276. doi: 10.1287/orsc.1110.0649

Metcalfe, N. B. (1984). The effects of mixed-species flocking on the vigilance of shorebirds: who do they trust? Anim. Behav. 32, 986–993. doi: 10.1016/S0003-3472(84)80211-0

Meyerson, D., Weick, K. E., and Kramer, R. M. (1996). “Swift trust and temporary groups,” in Trust in Organizations: Frontiers of Theory and Research, eds R. Kramer and T. Tyler (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications).

Mislin, A., Williams, L., and Shaughnessy, B. (2015). Motivating trust: can mood and incentives increase interpersonal trust? J. Behav. Exp. Econ. 58, 11–19. doi: 10.1016/j.socec.2015.06.001

Misztal, B. A. (2012). “Trust: acceptance of, precaution against, and case of vulnerability,” in Trust: Comparative Perspectives, eds M. Sasaki and R. M. Marsh (Leiden: Brill), doi: 10.1163/9789004221383_010

Möllering, G. (2001). The nature of trust: from Georg Simmel to a theory of expectation, interpretation, and suspension. Sociology 35, 403–420. doi: 10.1017/S0038038501000190

Möllering, G. (2014). Trust, calculativeness, and relationships: a special issue 20 years after Williamson’s warning. J. Trust Res. 4, 1–21. doi: 10.1080/21515581.2014.891316

Nienaber, A.-M., Hofeditz, M., and Romeike, P. D. (2015). Vulnerability and trust in leader-follower relationships. Personnel Review. doi: 10.1108/PR-09-2013-0162

Palinkas, L., Horwitz, S., Green, C., Wisdom, J., Duan, N., and Hoagwood, K. (2015). Purposeful sampling for qualitative data collection and analysis in mixed method implementation research. Admin. Policy Ment. Health Serv. Res. 42, 533–544. doi: 10.1007/s10488-013-0528-y

Pearson, A., Mayer, J., and Bradley, D. (2015). Coping with household water scarcity in the Savannah today: implications for health and climate change into the future. Earth Interact. 19, 1–14. doi: 10.1175/ei-d-14-0039.1

Pearson, A., and Muchunguzi, C. (2011). Contextualizing privatization and conservation in the history of resource management in southwestern Uganda: ethnicity, political privilege and resource access over time. Intern. J. Afr. Hist. Stud. 44, 1–27.

Pearson, A., Roberts, M., Soge, O., Ivanova, I., Mayer, J., and Meschke, J. (2008). Utility of EC 3MTM petrifilmsTM and sanitary surveys for source water assessment in south-western Uganda Water. Water SA 34, 1–5.

Pearson, A., Zwickle, A., Namanya, J., Rzotkiewicz, A., and Mwita, E. (2016). Seasonal shifts in primary water source type: a comparison of largely pastoral communities in Uganda and Tanzania. Intern. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 13:169. doi: 10.3390/ijerph13020169

PytlikZillig, L., Hamm, J., Shockley, E., Herian, M., Neal, T., Kimbrough, C., et al. (2016). The dimensionality of trust-relevant constructs in four institutional domains: results from confirmatory factor analyses. J. Trust Res. 6, 111–150. doi: 10.1080/21515581.2016.1151359

PytlikZillig, L., and Kimbrough, C. (2016). “Consensus on conceptualizations and definitions of trust: Are we there yet?,” in Interdisciplinary Perspectives on Trust, eds E. Shockley, T. Neal, L. PytlikZillig, and B. Bornstein (New York, NY: Springer International Publishing).

Rempel, J., Ross, M., and Holmes, J. (2001). Trust and communicated attributions in close relationships. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 81, 57–65. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.81.1.57

Rinkus, M. A., Dobson, T., Gore, M. L., and Dreelin, E. A. (2016). Collaboration as a process: a case study of Michigan’s watershed permit. Water Policy 18, 182–196. doi: 10.2166/wp.2015.202

Rotter, J. (1971). Generalized expectancies for interpersonal trust. Am. Psychol. 26, 443–452. doi: 10.1037/h0031464

Rousseau, D., Sitkin, S., Burt, R., and Camerer, C. (1998). Introduction to special topic forum: not so different after all: a cross-discipline view of trust. Acad. Manag. Rev. 23, 393–404. doi: 10.5465/amr.1998.926617

Sharp, E., Thwaites, R., Curtis, A., and Millar, J. (2013). Trust and trustworthiness: conceptual distinctions and their implications for natural resources management. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 56, 1246–1265. doi: 10.1080/09640568.2012.717052

Shepherd, S., and Kay, A. (2012). On the perpetuation of ignorance: system dependence, system justification, and the motivated avoidance of sociopolitical information. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 102, 264–280. doi: 10.1037/a0026272

Shockley, E., and Fairdosi, A. (2015). Power to the people? Psychological mechanisms of disengagement from direct democracy. Soc. Psychol. Pers. Sci. 6, 579–586. doi: 10.1177/1948550614568159

Soares, L. C. R., Griesinger, M. O., Dachs, J. N. W., Bittner, M. A., and Tavares, S. (2002). Inequities in access to and use of drinking water service in Latin America and the Caribbean. Rev. Panam. Salud Publica 11, 386–396. doi: 10.1590/s1020-49892002000500013

United Nations (2015). Resolution Adopted by the General Assembly. Available online at: http://www.un.org/ga/search/view_doc.asp?symbol=A/RES/70/1&Lang=E (accessed April 22, 2020).

van der Weff, L., Legood, A., Buckley, F., Wiebel, A., and de Cremer, D. (2019). Trust motivation: the self-underlying regulatory processes underlying trust decisions. Organ. Psychol. Rev. doi: 10.1177/2F2041386619873616

van Rijn, F., Bulte, E., and Adwkunle, A. (2012). Social capital and agricultural innovation in sub-Saharan Africa. Agric. Syst. 108, 112–122. doi: 10.1016/j.agsy.2011.12.003

Venot, J., and Clement, F. (2013). Justice in development? An analysis of water interventions in the rural South. Nat. Resour. Forum 37, 19–30. doi: 10.1111/1477-8947.12002

WHO/UNICEF (2012). Report of the Second Consultation on Post 2015 Monitoring of Drinking-water, Sanitation and Hygiene. The Hague: WHO/UNICEF.

Williams, M. (2001). In whom we trust: group membership as an affective context for trust development. Acad. Manag. Rev. 26, 377–396. doi: 10.5465/AMR.2001.4845794

World Bank (2006). Gender, Time Use, and Poverty in Sub-Saharan Africa. Available online at: https://elibrary.worldbank.org/doi/pdf/10.1596/978-0-8213-6561-8#page = 29 (accessed April 22, 2020).

Wutich, A. Y., Budds, J., Eichelberger, L., Geere, J., Harris, L., Horney, J., et al. (2017). Advancing methods for research on household water insecurity: studying entitlements and capabilities, socio-cultural dynamics, and political processes, institutions, and governance. Water Secur. 2, 1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.wasec.2017.09.001

Yang, H., Bain, R., Bartram, J., Gundry, S., Pedley, S., and Wright, J. (2013). Water safety and inequality in access to drinking-water between rich and poor households. Environ. Sci. Technol. 47, 1222–1230. doi: 10.1021/es303345p

Keywords: motivation, trustworthiness, Uganda, community-based resource management, gender

Citation: Hamm JA, Pearson AL, Namanya J and Gore ML (2020) Vulnerability, Trustworthiness, and Motivation as Emergent Themes in Cooperation With Community-Based Water Management in Southwestern Uganda. Front. Environ. Sci. 8:47. doi: 10.3389/fenvs.2020.00047

Received: 27 November 2019; Accepted: 08 April 2020;

Published: 05 May 2020.

Edited by:

Anders Hansen, University of Leicester, United KingdomReviewed by:

Karen M. Taylor, University of Alaska Fairbanks, United StatesJoe Campbell, The Ohio State University, United States

Copyright © 2020 Hamm, Pearson, Namanya and Gore. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Joseph A. Hamm, amhhbW1AbXN1LmVkdQ==

Joseph A. Hamm

Joseph A. Hamm Amber L. Pearson1,3,4

Amber L. Pearson1,3,4