94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Energy Res. , 30 August 2018

Sec. Carbon Capture, Utilization and Storage

Volume 6 - 2018 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fenrg.2018.00086

With increasing interest in using or displacing confined water for CH4 recovery or CO2 storage in nanoporous environments, understanding the organization and diffusion of gases is confined water environments is essential. In this study, the effect of hydration on the structure and diffusivity of confined carbon dioxide (CO2) and methane (CH4) in 2 nm slit-shaped calcite nanopore was studied using classical molecular dynamics simulations. The absence of confined water and the effect of different water concentrations including one layer of confined water composed of 150 water molecules, 500 water molecules, and 1,296 water molecules that correspond to the density of bulk water of 1 g/cm3 on the structural arrangement and diffusivity of confined CO2 and CH4 were investigated. Water molecules were found to influence the anisotropic distribution and mobility of confined CO2 and CH4 significantly by altering the structures of the adsorbed gas layers onto the calcite surfaces. The preferential adsorption of water on calcite surface over CO2 and CH4 resulted in the displacement of the adsorbed gas molecules toward the center of the pore. This water-induced displacement impacts the diffusivity of the confined gases by enabling transport through the center of the pore where there are fewer intermolecular collisions and less steric hindrance for transporting the molecules. Therefore, the diffusivity of CO2 and CH4 is higher in the presence of a single water layer as opposed to in pores without water. Energetic calculations showed that van der Waals and electrostatic interactions contributed to the affinity of CO2 for calcite surfaces, while van der Waals interactions dominate CH4 interactions with calcite and the surrounding water molecules. The anisotropic variations in the diffusivities of confined fluids emerge from changes in the organization of confined fluids and potential differences in the free energy distributions as a function of the orientation of the calcite surface. These findings suggest that any efforts to potentially engineer the nano-scale pore environment in calcite for enhanced gas recovery or storage will require us to consider the organization and anisotropic transport behaviors of confined fluids.

With more than 80% of our energy needs being met by the subsurface environments (BP Global, 2015), there is a significant interest in environmentally benign approaches to recover and store fluids in complex materials characterized by chemical and morphological heterogeneity and nano-scale porosity. Various studies have shown that the properties and transport of confined fluids such as water (Bonnaud et al., 2010; Ho and Striolo, 2015; Hu et al., 2015; Chakraborty et al., 2017), gases such as CO2 (Chialvo et al., 2012; Le T. et al., 2017; Striolo and Cole, 2017; Simoes Santos et al., 2018), and hydrocarbons (Cole et al., 2013; Le et al., 2015a,b; Wu et al., 2015; Le T. T. B. et al., 2017; Herdes et al., 2018; Obliger et al., 2018; Simoes Santos et al., 2018) in nanoporous environments differs from bulk behaviors due to changes in the structure and affinity of confined liquids (Wang H. et al., 2016; Johnston, 2017) and gases (Yuan et al., 2015; Sun et al., 2016a,b, 2017; Wang S. et al., 2016a,b) for the solid interfaces. With increasing interest in enhanced gas recovery coupled with subsurface CO2 storage, a fundamental understanding of the changes in the structure of CO2 and CH4 and transport properties of these gases through water-bearing nanoporous environments provides a scientific basis for the observed fate and transport of these gases at the field scale (Glezakou and McGrail, 2013; Gadikota et al., 2017; Gadikota, 2018; Gadikota and Allen, 2018).

Confined geometries impose inhomogeneity and anisotropy on the structure and dynamics of confined fluids due to the interaction of fluid-solid interfaces (Granick, 1991; Relat-Goberna and Garcia-Manyes, 2015) which can be successfully probed using classical Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations. Further, MD simulations explain the underlying subnano- and nano-scale mechanisms including adsorption and interfacial phenomena, and thermophysical properties such as viscosity and transport properties such as diffusion. In this study, the structure and transport properties of CH4 and CO2 in various water-bearing environments at calcite interfaces are probed using classical MD simulations. Calcite interfaces are chosen since calcite-bearing rocks are one of the major constituents of hydrocarbons reservoirs in the world (Addari and Satta, 2015) including shale reservoirs (Xu et al., 2005). Calcite is present in almost all geological systems and represents the main constituent of limestone which forms most of the world's hydrocarbons reservoirs (Meldrum and Cölfen, 2008; Geysermans and Noguera, 2009; Addari and Satta, 2015; Bovet et al., 2015; Côté et al., 2015). For this reason, several studies focused on understanding gas interactions in calcite nano-pores (Franco et al., 2016; Sun et al., 2016b, 2017; Wang S. et al., 2016a,b; Bui et al., 2017; Simoes Santos et al., 2018). Further, shale formations such as the Middle Bakken region in North America are characterized by a significant fraction of calcite which contribute to pore sizes that are 2 nm or greater (Liu et al., 2017). Therefore, a pore size of 2 nm was chosen as a reasonable approximation for a representative pore size of calcite.

This approach is intended to facilitate a calibrated understanding of the influence of confined water on the structure and diffusivity of CO2 and CH4 in calcite nanopores. Further, important scientific insights were developed by probing the interactions of confined mixed gases in calcite nanopores. CO2 was found to displace adsorbed hydrocarbons in calcite nanopores and the adsorption of CO2 was influenced by the quantity of surface adsorption sites (Simoes Santos et al., 2018). As an example, the preferential adsorption of CO2 on the pore surface was found to weaken the adsorption of n-butane (Le et al., 2015a). An evaluation of the diffusivity of methane, nitrogen and CO2 confined in calcite slit-shaped nanopore showed that the diffusivity of the simulated fluids close to the surface differs from the molecules away from the solid interface and toward the center of the pore (Franco et al., 2016). This anisotropic behavior was evident in the diffusivity of methane through hydrated calcite pores (Bui et al., 2017). In the absence of any dissolved gas solutes, the translational and rotational dynamics of confined water were found to be dependent on the local density variation and the local hydrogen bonds connectivity, respectively (Mutisya et al., 2017). Further, the self-diffusion coefficient of water in confined quartz (Ishikawa and Tsuchiya, 2017) and montmorillonite (Rao and Leng, 2016; Gadikota et al., 2017) was lower compared to bulk water.

The chemistry of the solid interface has a significant impact on the diffusion and adsorption of different fluids (Schaef et al., 2013, 2015; Lee et al., 2014, 2017; Kadoura et al., 2016; Sun et al., 2016b; Fazelabdolabadi and Alizadeh-Mojarad, 2017; Gadikota et al., 2017). In addition to the chemistry of the solid interface, the pore size had a strong influence on the diffusivity of fluids. For example, octane diffusion was found to increase rapidly with the size of the montmorillonite interlayer pore (Wang H. et al., 2016). The decrease in the density of octane as it migrates from the nanopore to mesopore enhances the diffusivity which aids hydrocarbon recovery from the subsurface (Wang H. et al., 2016). In this work, MD simulations were performed to investigate the structure and transport behavior of confined CO2 and CH4 in calcite slit shaped nanopore with varying levels of hydration to mimic water-bearing nanopores in the subsurface environments.

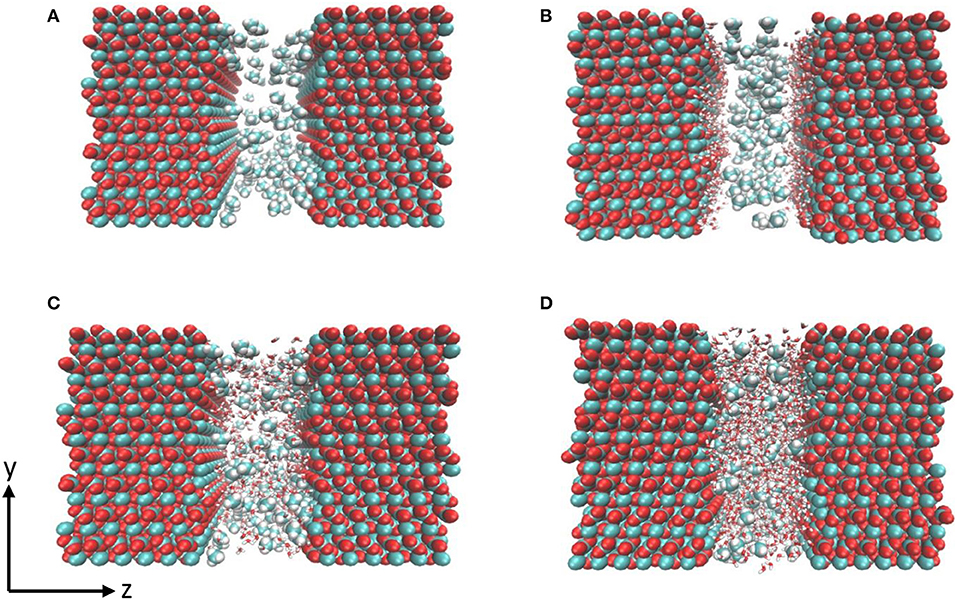

The simulation system is composed of a periodic slit-shaped calcite nanopore with a width of 2 nm. The simulation box with dimensions of 48.57 × 39.92 × 68.58 Å consists of two calcite blocks with each block composed of 6 calcite layers (Figure 1). The calcite surfaces were obtained by cutting calcite along the (104) crystallographic surface based on calcite unit cell. The calcite surfaces were immobilized in the simulation. Table 1 below describes the interatomic parameters used in this study.

Figure 1. Snapshot of the initial configurations composed of calcite surface and methane (A) with no water, (B) single water layer, (C) 500 water molecules, and (D) 1 g/cm3 of confined water. Water molecules are shown as red and white sticks, carbon and hydrogen in methane are represented in cyan and white respectively.

Four systems were constructed to investigate the effect of hydration on the structure and diffusivity of CO2 and CH4. First, 100 molecules of pure CO2 and CH4 were randomly distributed in the pore space to investigate the structure and dynamics of gases in the absence of pore water as shown in Figure 1A. In the second case, a single layer of water composed of 150 water molecules was added at the calcite interface (Figure 1B). The thickness of water layer was chosen based on experimental observations reported by Fenter et al. (2000). In the third configuration, the nanopore was solvated with 500 number of water molecules (Figure 1C). The fourth scenario, the density of confined water was set to mimic that of bulk water i.e., density of 1 g/cm3 of water (1,296 molecules) for potential comparison with previous studies (Figure 1D) (Mutisya et al., 2017).

Canonical ensemble (NVT) simulation was performed on the product of energy minimization for 10 ns using Nose-Hoover (Nosé, 1984; Hoover, 1985) thermostat with time constant of 1 ps to control the temperature of both surface and the fluids. The energy of the initial configurations was minimized using steepest descent method for 50,000 steps to ensure that the energy is <100 kJ mol−1 nm−1. The simulations were performed at standard temperature and the pressure was calculated based on Ping Robinson equation of state (EOS) (Peng and Robinson, 1976) by inserting specific number of gas molecules to satisfy the required density. One hundred molecules of CH4 were inserted in the system free of water to match a pressure of about 125 bar which was studied experimentally to represent the shale pressure (Zhong et al., 2016; Xing et al., 2018). Number of CO2 molecules was chosen as an equimolar of methane for comparison purposes. Since we are interested in the effect of water on the properties of confined gases, number of CH4 and CO2 molecules were kept constant in all four configurations and various amount of water were added into each system.

Statistics were evaluated by dividing each simulation into three 1.5 ns blocks. Each block was treated as an independent replicate. The SHAKE algorithm was used to keep the water molecules rigid (Ryckaert et al., 1977). Van der Waals (vdW) interactions were modeled by Lennard-Jones (LJ) 12-6 function, and electrostatic interactions, which modeled by Coulomb's function as shown in Equation 1.

In Equation (1), qiand qj are the charges of i and j, rij is the distance between i and j. LJ parameters (i.e., εij and σij) for unlike molecular interactions were calculated based on Lorentz-Berthelot rule as following:

The intramolecular interactions accounted for bond stretching, angle bending and dihedrals. Electrostatic and dispersion interactions were computed in real space up to a distance of 14 Å. Long range electrostatic interactions were evaluated using particle mesh Ewald (PME) (Darden et al., 1993). Simulations were carried out using the GROMACS program. Simulation results were analyzed to determine the structure and diffusivity in the calcite nanopores. The structural changes in the gas molecules in confinement were evaluated using radial distribution functions (RDFs) extracted from the trajectory using VMD (Humphrey et al., 1996).

The self-diffusion coefficients were calculated for each gas (i.e., CO2 and CH4) in the calcite nanopore. The diffusion coefficients were calculated based on the mean square displacement (MSD) for the directions and the plane parallel to the pore dimensions (DX, DY, and DXY) according to the following equation:

Where d is the number of dimensions (1 for DX and DY and 2 for DXY). The diffusion coefficients in x and y directions (i.e., DX and DY) were calculated to determine if diffusion is isotropic or anisotropic for the confined fluids. The diffusivity of the molecules is considered to be isotropic if the diffusion coefficients in X and Y directions are equal, otherwise the diffusion is anisotropic (Bui et al., 2017).

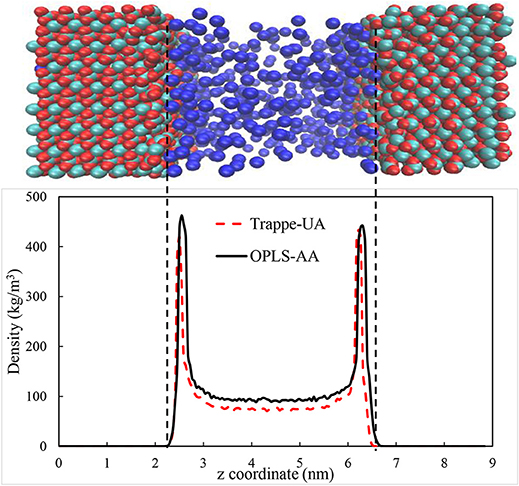

The calcite surface was modeled using forcefield developed by Xiao et al. (2011). CO2, CH4, and water were modeled using EPM2 (Harris and Yung, 1995), OPLS/AA (Jorgensen et al., 1996), and SPC/E (Berendsen et al., 1987) models respectively. Several forcefields were used in the literature to model confined gases. For example, OPLS-UA (Bui et al., 2017), OPLS-AA (Gadikota et al., 2017), CVFF (Yuan et al., 2015), COMPASS (Sun et al., 2016a,b), and TraPPE-UA (Simoes Santos et al., 2018) were used to represent CH4 in confinement. To evaluate the appropriate forcefield, MD simulations were performed using several forcefields to reproduce the properties of the confined CH4 in the calcite pore and compare the governed data from each forcefield with published data. The structure of the confined CH4 in 4 nm calcite pore with density of 96 kg/m3 and 375 K was calculated and compared with the data reported by Simoes Santos et al. (2018). We employed both Trappe-UA and OPLS-AA forcefields to calculate CH4 distribution. As shown in Figure 2, the distribution of CH4 in calcite nanopores are in reasonable agreement. Both forcefields proved the ability to reproduce the required data, however, we used OPLS-AA since the interatomic potentials of C and H are specified independently (Gadikota et al., 2017). To validate the choice of OPLS-AA further, the density of methane was calculated at standard temperature and pressure by simulating 500 methane molecules using NPT ensemble for 10 ns. Nose-Hoover thermostat and Parrinello–Rahman barostat (Parrinello and Rahman, 1982) were used to control the temperature and pressure, respectively. The governed density is 0.648 ± 0.013 kg/m3 which is consistent with the experimental value which is about 0.656.

Figure 2. The distribution of methane in 4 nm calcite nanopore under 375 K and density of 96 Kg/m3. The calcium, carbonate and methane species are shown by cyan, red, and blue colors, respectively.

Similarly, various forcefields such as EPM2 (Headen and Boek, 2010; Liu L. et al., 2015; Fazelabdolabadi and Alizadeh-Mojarad, 2017; Mohammed and Mansoori, 2018a,b,c), TraPPE (Javanbakht et al., 2015; Simoes Santos et al., 2018), and COMPASS (Liu B. et al., 2015; Liu et al., 2016; Fang et al., 2017) were used to model CO2 and its behavior under bulk and confinement conditions. Various studies validated simulated properties such as diffusivity (Moultos et al., 2014, 2016) and solubility (Vlcek et al., 2011) of CO2 in water using the EMP2 forcefield. To validate the choice of EMP2 forcefield in this study, the diffusion coefficient of CO2 in water was calculated by dissolving 5 CO2 molecules in 2000 SPC/E water molecules in an initial cell of 4 × 4 × 4 nm3 to be consistent with previous studies (Moultos et al., 2014). The system was simulated for 5 ns under 1 bar and 323 K using NPT ensemble. The produced self-diffusion coefficient is in reasonable agreement with the experimental and simulated data (Versteeg and Van Swaaij, 1988; Moultos et al., 2014). The diffusion coefficient for CO2 in water is 4.3 (±0.4) × 10−5 cm2/s compared with 4 × 10−5 cm2/s (Moultos et al., 2014) and 3.4 × 10−5 cm2/s (Versteeg and Van Swaaij, 1988) reported in previous studies.

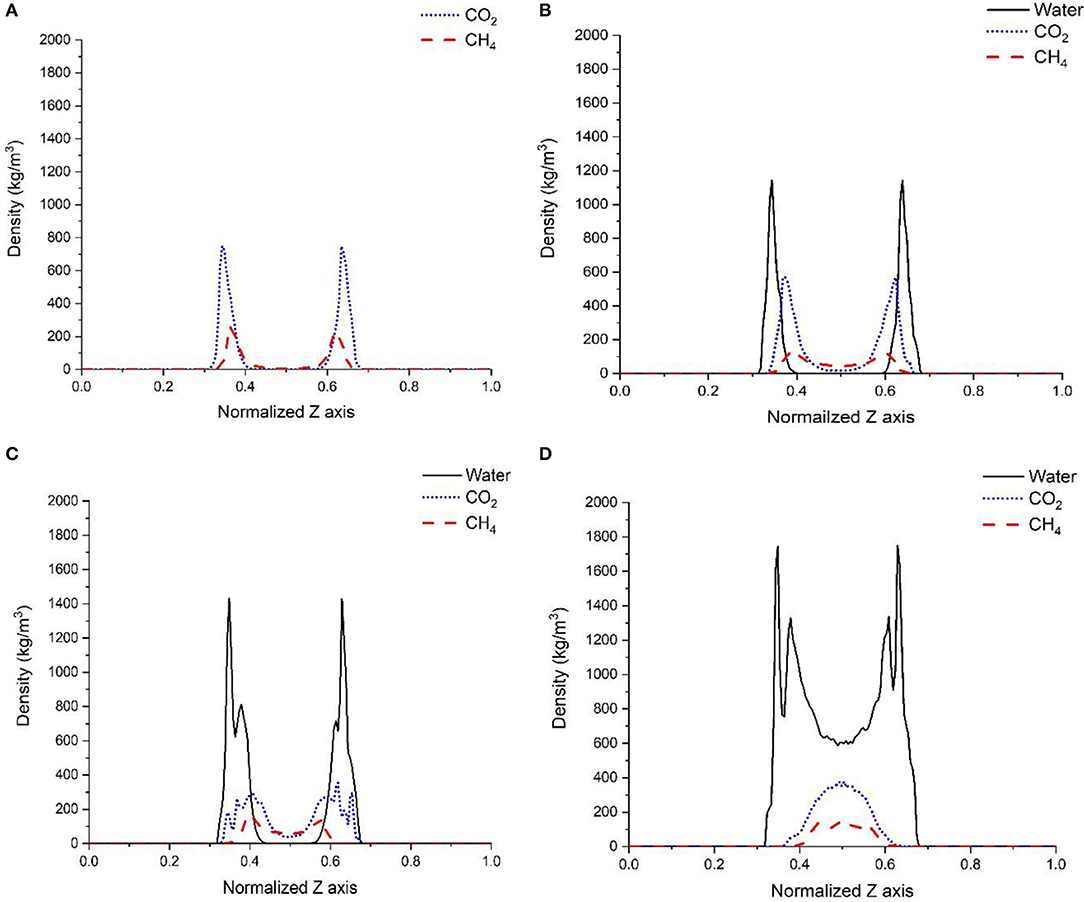

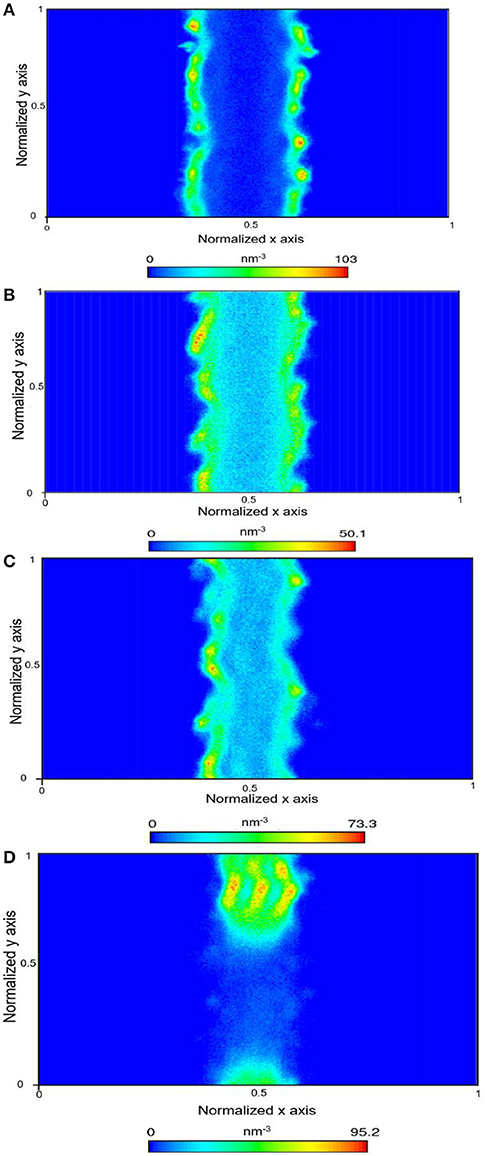

Probing the structure of gases in varying confined water environments provides insights into changes in the affinity of gases for the solid interfaces. As shown in Figure 3, the density profiles of gases (CO2, CH4) differ when there is no water, one layer of interfacial water composed of 150 molecules, 500 molecules of confined water, and confined water mimicking the density of bulk water (with 1,296 water molecules) in the calcite nanopore. In the absence of water, both CO2 and CH4 show a layered structure on the calcite surface and the density profiles are symmetric with respect to the pore center (Figure 3A). These density profiles indicate that CO2 and CH4 are adsorbed to create a single layer on the calcite surface in the absence of water which is consistent with previous studies (Franco et al., 2016; Sun et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2017; Simoes Santos et al., 2018). The higher density of CO2 at the interface compared to CH4 is attributed to the higher energetic affinity of CO2 on the calcite interface compared to CH4 as reported by Wang S. et al. (2016b).

Figure 3. Density profiles of CO2, and CH4 in the absence of pore water (A), one layer of confined water composed of 150 water molecules (B), 500 water molecules (C), and 1,296 water molecules that correspond to a density of bulk water of 1 g/cm3 (D). The X-axis represents the normalized pore surface in the z-direction.

In the presence of a single layer of interfacial water, the peak density of CO2 at the calcite interface decreases from 749 to 550 kg/m3. Similarly, the peak density of CH4 decreases from 239 to 126 kg/m3. Further, a higher density of CO2 and CH4 is noted at the center of the pore in the presence of interfacial water. A reduction in the number of molecules in the adsorbed shells of CO2 and CH4 and the shift of these shells away from the calcite surface is noted. CO2 and CH4 adsorbed layers were shifted by ~1.5 Å compared to the case where there is no water (Figure 3B). The variation in the relative density of CO2 and CH4 due to the presence of water layer can be explained by two factors: the higher adsorption energy of water on the calcite surface compared to CO2 and CH4 (Wang S. et al., 2016b) and the difference in the interfacial tension of CO2 and CH4 with water. CO2 has lower interfacial tension with water compared with CH4 and is partially miscible with water (Bachu and Bennion, 2008; Sakamaki et al., 2011; Yasuda et al., 2016).

In the third scenario, 500 water molecules were randomly distributed in the pore space to represent the abundance of the confined water within the pore. The equilibrium density profiles are shown in Figure 3C. After equilibrating the cell for 5 ns, the water molecules were arranged into two layers on the calcite surface as noted by the peak positions at 0.35 and 0.38 nm in Figure 3C. This specific arrangement of water molecules at calcite interfaces was noted experimentally and computationally (Fenter and Sturchio, 2004; Geissbühler et al., 2004; Argyris et al., 2008; Heberling et al., 2011; Ou et al., 2014; Keller et al., 2015; Fazelabdolabadi and Alizadeh-Mojarad, 2017). A significant reduction in the relative densities of CO2 and CH4 at the calcite interface is noted and compared to the case where a single layer of interfacial water is present. A bi-layered arrangement of CO2 molecules with one peak located near the water-CO2 interface and another at the calcite-water interface was noted. The existence of the water film leads to a wider distribution of CO2 molecules at the calcite interface.

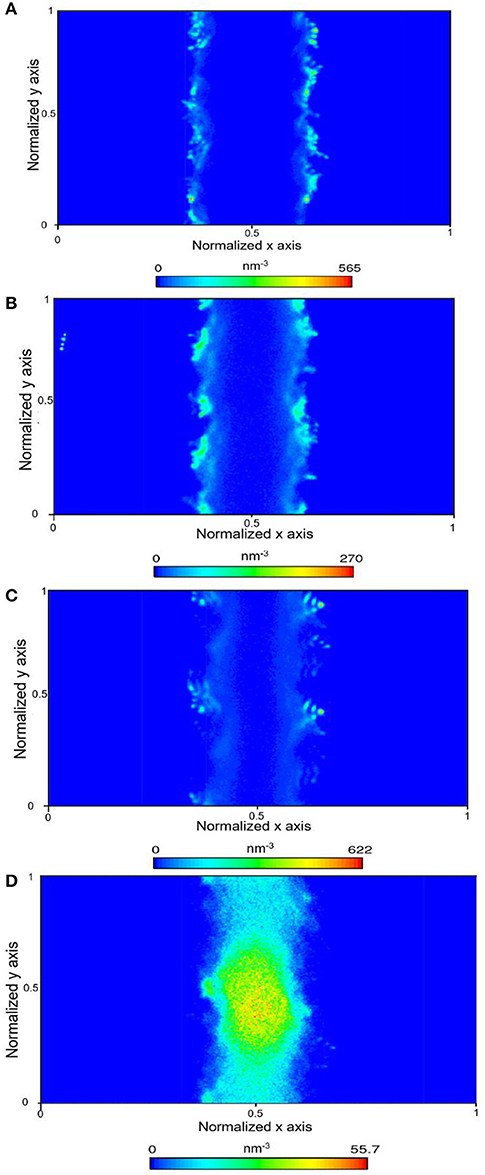

In the presence of interfacial water mimicking the density of bulk water, the bi-layer arrangement of water molecules was noted (Figure 3D) which is consistent with the studies reported by Keller et al. (2015) and Mutisya et al. (2017). Higher concentrations of CO2 and CH4 were noted at the center of the calcite pore in the presence of this interfacial water. The density maps in Figures 4, 5 provide further insights into the distribution of gases in varying levels of confined water. In general, the presence of different amounts of water displaces more CH4 molecules toward the pore center compared with CO2. At a density of 1 g/cm3, a phase separation was noticed between water and CH4 molecules which are concentrated at the pore center. In contrast, CO2 molecules was displaced toward the center of the pore while being solvated in the water phase, as shown in Figures 4, 5d.

Figure 4. Density map density of CO2 within the calcite nanopore in the absence of pore water (A), one layer of confined water composed of 150 water molecules (B), 500 water molecules (C), and 1296 water molecules that correspond to a density of bulk water of 1 g/cm3 (D).

Figure 5. Density map density of CH4 within the calcite nanopore in the absence of pore water (A), one layer of confined water composed of 150 water molecules (B), 500 water molecules (C), and 1,296 water molecules that correspond to a density of bulk water of 1 g/cm3 (D).

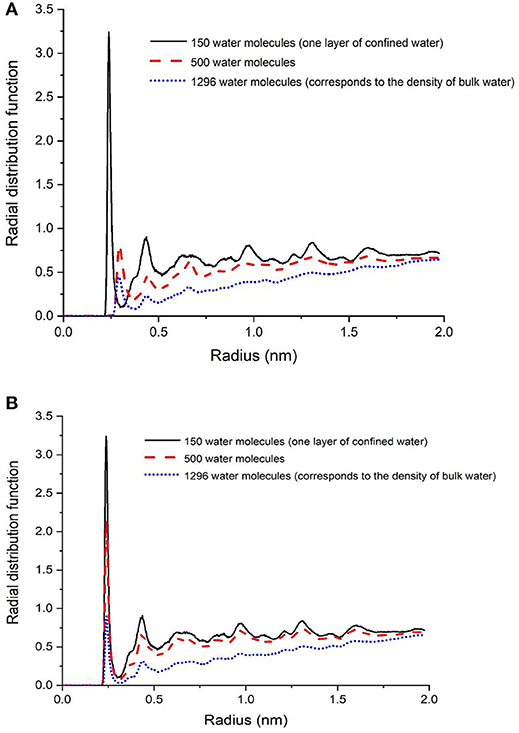

It was interesting to note that the structure of a single layer of interfacial water (Figure 1B) did not change in the presence of CO2 or CH4 (Figures 6A,B). In the presence of 500 and 1,296 water molecules with 100 molecules of CO2 (Figure 6A), the Cacalcite-Owater interface changed significantly unlike in the case with 100 molecules of CH4 (Figure 6B). The water layer in the system bearing CO2 is about 1.3 times wider than CH4 and is shifted away from the calcite surface. One hypothesis is that the higher solubility of CO2 in water compared to CH4 influences the interfacial structure of water. For example, at 298 K, the solubility of CO2 and CH4 in water are 0.0286 and 0.0008 mol/kgwater, respectively (Wiesenburg and Guinasso, 1979; Duan and Sun, 2003). The hydration of CO2 in water potentially results in less sharp water layer. In the presence of interfacial water with a density similar to bulk water, fewer number of oxygen atoms corresponding to the water molecules are present in the first shell of Ca2+ in calcite.

Figure 6. Radial distribution function of calcium in calcite with respect to oxygen in water in systems composed of a single water layer, 500 water molecules, and 1 g/cm3 of confined water in presence of CO2 (A) and CH4 (B).

Higher confined water concentrations reduced the number of oxygen atoms corresponding to calcite in the first coordination shell of CCH4 and CCO2. In the absence of water, about 11 and 9 oxygen atoms corresponding to calcite in the first coordination shell of CCO2 and CCH4 are noted. These data are consistent with the higher adsorption affinity of CO2 for the calcite interface compared to CH4. In the presence of 300, 500, and 1,296 water molecules, the number of oxygen atoms corresponding to calcite in the first coordination shell of CCO2 are about 4, 3, and 1. Similarly, in the presence of CH4, 300, 500, and 1,296 water molecules, the number of oxygen atoms corresponding to calcite in the first coordination shell of CCH4 are about 3, 2, and <1, respectively. These data suggest that increasing the number of water molecules reduces the affinity of the gas molecules for the calcite interface.

The number of oxygen atoms corresponding to water in the first coordination shell of CCH4 were in the range of 4–6 in varying confined water concentrations. The number of oxygen atoms corresponding to water in the first coordination shell of CCO2 were about 10, 5, and 4 in the presence of 300, 500, and 1,296 water molecules. These data suggested that the number of water molecules in the confinement had a much stronger influence on the coordination behavior of water molecules with CO2, unlike CH4.

The orientation of the CO2 molecules is determined by comparing the coordination behavior of oxygen and carbon in CO2 with calcite and water interfaces. In all the simulated systems, the number of oxygen atoms in CO2 are about twice the number of carbon atoms in CO2 in the first shell. This observation suggests that the CO2 molecules orientated parallel to the calcite surface, which is consistent with previous reports of CO2 orientation with Na-montmorillonite surface (Botan et al., 2010; Myshakin et al., 2013; Yang et al., 2015; Kadoura et al., 2016). Also, the number of oxygen atoms of CO2 in the first shell of the oxygen atoms of water is twice the number of carbon atoms in the case where a single layer of interfacial water is present. This observation is consistent with the orientation of CO2 parallel to the water interface (Zhao et al., 2011).

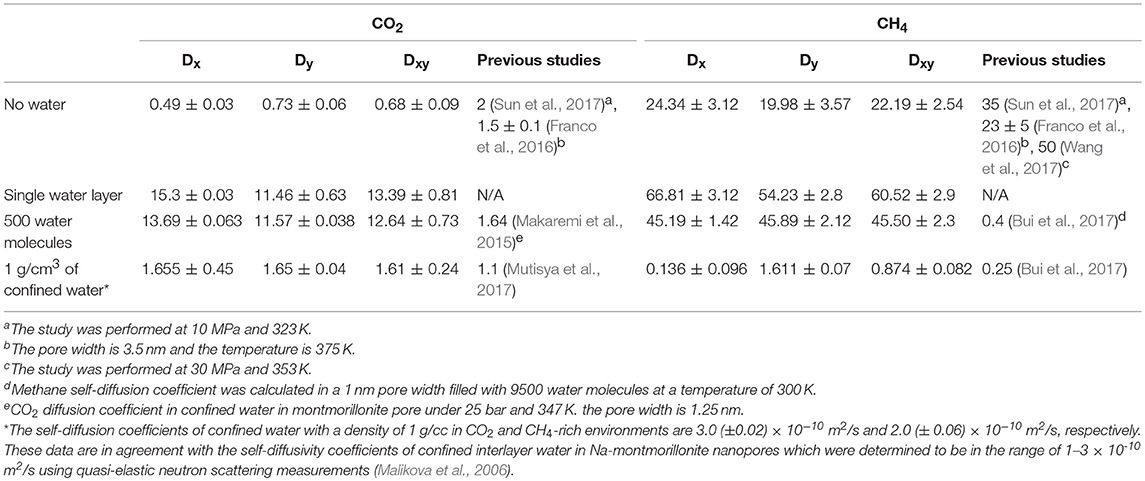

The diffusivity of CO2 and CH4 through calcite nanopores without water, one layer of interfacial water composed of 150 water molecules, 500 water molecules, and 1,296 water molecules to mimic the density of bulk water yielded interesting insights. In general, the diffusion coefficients of CO2 and CH4 in the absence of water are in reasonable agreement with Sun et al. (2017) after accounting for the differences in temperature. The temperature used in this study is 298 K compared with 323 K studied by Sun et al. (2017). The diffusion coefficient for CO2 in the absence of water is 0.4 x 10−5 cm2/s at 298 K compared with 2 × 10−5 cm2/s at 323 K. The diffusion coefficient for CH4 is ~20 × 10−5 cm2/s at 298 K compared with 35 × 10−5 cm2/s at 323 K. CO2 and CH4 diffusivities in the presence of interfacial water with a density similar to bulk water are in the range reported by Mutisya et al. (2017) and Bui et al. (2017) (Table 2).

Table 2. The self-diffusion coefficients (10−9 m2/s) of CO2 and CH4 in the absence of pore water, one layer of confined water composed of 150 water molecules, 500 water molecules, and 1,296 water molecules that correspond to a density of bulk water of 1 g/cm3.

The diffusivities are calculated in X, Y directions and in XY plane. The anisotropic variations in the diffusivity of gases in the X and Y directions are noted and shown in Table 2, which is consistent with the data reported by Franco et al. (2016). The diffusion coefficients of CH4 in X and Y directions are not equal in systems without water and in the presence of single water layer which is consistent with previous studies (Wang S. et al., 2016a; Bui et al., 2017). CH4 diffusivity in the X direction is higher than that in Y direction by about 4.36 × 10−5 and 12.58 × 10−5 cm2/s in the absence of water and the presence of one layer of interfacial water, respectively. However, this difference is much smaller in systems containing more water molecules (Table 2).

Further, an increase in the diffusivity of CO2 and CH4 in the presence of one layer of interfacial water was noted. The diffusivity of CO2 increased from ~ 0.4 × 10−5 to ~ 13 × 10−5 cm2/s on introducing a single layer of interfacial water in the simulation system. To date, studies have not reported the diffusivity of CO2 in calcite nanopores in the presence of one layer of interfacial water. In the absence of pore water, CO2 has a strong preference for the calcite interface as shown in Figure 3A. In the presence of interfacial water, the density of CO2 at the interface is reduced which potentially allows for greater mobility within the pore space. Similar diffusivities of CO2 are noted in the presence of a single layer of interfacial water and in the presence of 500 water molecules.

Similarly, the diffusivity of CH4 in calcite nanopore composed of a single water layer is about three times higher than the diffusivity in calcite nanopores without water. The reduced affinity of CH4 for the calcite surface in aqueous environments may be one of the factors enhancing the diffusivity of CH4 at these conditions. CH4 diffusivity in the system without water is much higher compared with CO2 due to the reduced adsorption affinity to the calcite surface. Another contributing factor to the variation in the diffusivity is the molecular weight. The molecular weight of CO2 is higher than CH4. Enhanced diffusivity of CH4 in the calcite nanopore in the presence of a single layer of interfacial water and 500 water molecules is noted.

The in-plane diffusivity (Dxy) of both CO2 and CH4 interestingly increased in the systems contain a single water layers compared to the systems free of water due to the reduction in the concentration of the gases adsorbed layers onto the pore surfaces in the presence of water molecule. In the systems free of water, the predominant movement of the molecules is the surface diffusion onto the calcite surface, however, when a preconstructed water layer added to the system, it prevents some of the gases molecules to be adsorbed which are consequently could move faster in the pore space. When additional water added to the system, the diffusivities of CO2 and CH4 decreased compared to the scenario of single water layer due the increase in the overall systems density which leads to more intermolecular collisions and higher steric hindrance.

Diffusivities of CO2 and CH4 in interfacial water with a density similar to bulk water are 1.6 × 10−5 and 0.87 × 10−5 cm2/s, respectively. The diffusivities of CO2 and CH4 in Na-montmorillonite nanopore bearing two layers of interlayer water at similar conditions are 1.04 × 10−5 and 0.85 × 10−5 cm2/s (Gadikota et al., 2017) which are in reasonable agreement with this study. It is interesting to note that despite the differences in the solid interface i.e., calcite vs. Na-montmorillonite, similar diffusivities of CO2 and CH4 in interfacial water are predicted. These data suggest that the diffusivities of fully solvated CO2 and CH4 are much lower compared to gases in the absence of confined water.

One of the important outcomes of this study is the observed differences in the diffusivities of confined CO2 and CH4 in the x and y directions. These data are the first systematic observations of the influence of varying levels of confined water on the diffusivities of confined CH4 and CO2. These differences are attributed to the organization of the water molecules in confinement and the interfacial interactions between the gases, water, and solid interfaces. In the absence of water, one of the key factors influencing the transport of gases is their interactions with calcium and carbonate species on the calcite surface. Previous studies by Bui et al. (2017) showed that the anisotropy in the diffusivity of gas molecules such as CH4 in calcite pores is significantly greater compared to other solid substrates such as silica, MgO, alumina, and muscovite using Principal Component Analyses. The anisotropic variation in the diffusivities of the confined gas molecules is attributed to the difference in the energy barriers as the gas molecules are transported along a specific direction. It is important to note that the x- and y-orientations are interchanged in the data in this study with respect to the studies performed by Bui and co-workers. Regardless the scientific insights are similar.

In this study, diffusivity of methane in the x-direction is greater than that of the diffusivity in the y-direction in the absence of water suggesting that the free energy barrier for the movement of methane molecules in the x-direction is lower compared to the energy barrier associated with diffusivity in the y-direction. It was also interesting to note that as the water content in calcite pores is increased to 500 molecules and then 1,296 molecules, the diffusivity of methane molecules in the x and y directions are roughly equal, and then diffusivity in the y-direction exceeds that in the x-direction. These data suggest that the solvation free energy distributions of confined methane within the calcite pores vary with the water content. Our observations noted in Figure 5d suggest that in the presence of 1,296 water molecules, methane molecules undergo phase separation, which allows the molecules to move freely in the y-direction relative to the x-direction.

However, the observed diffusion behaviors of CO2 in varying levels of confined water differ significantly from that of CH4. Previous studies also showed that the solvation free energies of CO2 in confined water are much lower compared to CH4 (Gadikota et al., 2017). Unlike methane, the phase separation of CO2 molecules in environments composed of 1,296 water molecules is not observed (Figure 4d). This observation is consistent with the similar diffusivities of CO2 in the x and y directions in 1,296 water molecules. In the absence of confined water, the diffusivity of CO2 in the y-direction is greater compared to that in the x-direction. However, the trends in the observed diffusivities are switched in the presence of a single layer of water and 500 water molecules. These data suggest that the energy barriers associated with the movement of CO2 vary significantly in the x and y directions in the presence of fewer water molecules.

The van der Waals and electrostatic energies associated with the interactions of CO2 and CH4 with calcite interfaces with varying levels of water hydration were determined. These calculations provide insights into the energetics driving the interactions of CO2 and CH4 in confined water environments. In the absence of confined pore water, the affinity of CH4 for the calcite interface was driven by van der Waals interactions. In the case of CO2, however, the electrostatic and van der Waals interactions enhance the affinity of the calcite surface (Table 3). The overall energetic affinity of CO2 for the calcite interface is much higher compared to that of CH4. These findings are consistent with previous studies that pointed to the higher adsorption affinity of CO2 for the calcite surface compared to CH4 at the same conditions (Sun et al., 2016b; Wang S. et al., 2016b; Simoes Santos et al., 2018). The quadruple moment of CO2 gives rise to the enhanced electrostatic interactions leading to higher affinity of CO2 for calcite interfaces compared to CH4 (Lithoxoos et al., 2010; Saha et al., 2010; Skarmoutsos et al., 2013; Duan et al., 2016; Liu et al., 2016; Molyanyan et al., 2016).

In the presence of a single layer of interfacial water, the van der Waals affinity of CO2 and CH4 for the calcite interface is lower than the systems free of water (Table 3). These data are consistent with the reduced number of first shell oxygen atoms corresponding to calcite with respect to the carbon atoms in CO2 and CH4. The number of oxygen atoms in calcite in the first shell of CO2 decrease from 9 to about 3. Similarly, the number of oxygen atoms in calcite in the first shell of CO2 decrease from 11 to about 4. The van der Waals and electrostatic affinity of CO2 for the single layer of interfacial water compared to CH4 is noted (Table 3).

When the number of water molecules in the calcite nanopore is increased to 500, the solvation of CO2 and CH4 in the confined water close to the calcite surface is noted from the overlap in the density distributions of gases with that of confined water (Figure 3C). The van der Waals affinity of gases corresponding to the solvation behavior increases with the increase in the number of water molecules (Table 3). The increase in the electrostatic energetic interactions of CO2 with the calcite surface from −801 kJ/mol in the presence of a single layer of interfacial water to −1,412 kJ/mol in the presence of 500 water molecules is attributed to CO2 solvation close to the calcite interface. The electrostatic interactions of methane with calcite in the presence of 500 water molecules are negligible.

The interaction of gases with the calcite surfaces are significantly reduced when the density of the interfacial water is similar to that of bulk water. The progressive reduction in the van der Waals affinity associated with CO2 and CH4 interactions with calcite with increasing water levels is noted (Table 3). This observation is consistent with the reduced number of oxygen atoms of calcite in the first coordination shell corresponding to Cgas-Ocalcite. The number of oxygen atoms in calcite in the first shell of CO2 or CH4 are less than one when the density of interfacial water is similar to that of bulk water. Previous studies reported high van der Waals affinity of solvated gases for the solid interface (i.e., Na and Ca-montmorillonite) (see Schaef et al., 2013, 2015; Lee et al., 2014, 2015, 2017) with a pore size smaller than 1 nm. In this study, a pore size of 2 nm is simulated. With smaller pore sizes i.e., when the solid interfaces are closer, the overall energetic contributions arising from interactions with the solid interface may differ. In case of CO2, the van der Waals and electrostatic interactions arising from interactions with water contribute to CO2 solvation. However, the van der Waals interactions are the primary contributors to CH4 solvation in confined water.

To provide a fundamental understating of the influence of hydration on CO2 storage and CH4 recovery from calcite nanopore, classical molecular dynamics simulations were performed. Introducing water molecules into the nanopores showed a significant impact on the dynamics and transport properties of CO2 and CH4. The preferential adsorption of water onto the calcite surface enabled the displacement of the adsorbed gases toward the center of the pore, which is an advantage for CH4 recovery. Higher water concentrations facilitated the solvation of CO2 molecules in the center of pore while CH4 was found to phase separate at similar conditions. In the presence of water films at calcite interfaces, the density of CO2 and CH4 closer to the solid interface is higher compared to the center of the pore which is attributed to the van der Waals affinity in the case of CO2 and CH4 and, electrostatic affinity in the case of CO2. Anisotropic diffusivities of CO2 and CH4 in specific water environments are attributed the differences in the directional free energy distributions, influence of solvation and the structure of confined water. While previous studies suggested that the diffusivities of gases vary in bulk and confined fluid environments, our results show that the extent of hydration has a strong influence on the adsorption and diffusivity of confined gases. With increasing interest in the recovery of gases such as CH4 using water or storage of CO2 by displacing pore fluids in the subsurface environments, understanding the changes in the organization, and transport of confined fluids is increasingly important as discussed in this study.

SM performed the MD simulations and the analyses. GG developed the concept and assisted in writing the manuscript.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The reviewer VG and handling editor declared their shared affiliation at the time of the review.

The authors gratefully acknowledge the Wisconsin Alumni Research Foundation and the College of Engineering at the University of Wisconsin, Madison for supporting this research effort.

Addari, D., and Satta, A. (2015). Influence of HCOO–on calcite growth from first principles. J. Phys. Chem. C 119, 19780–19788. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpcc.5b04161

Argyris, D., Tummala, N. R., Striolo, A., and Cole, D. R. (2008). Molecular structure and dynamics in thin water films at the silica and graphite surfaces. J. Phys. Chem. C, 112, 13587–13599. doi: 10.1021/jp300679v

Bachu, S., and Bennion, D. B. (2008). Interfacial tension between CO2, freshwater, and brine in the range of pressure from (2 to 27) MPa, temperature from (20 to 125) C, and water salinity from (0 to 334 000) mg· L– 1. J. Chem. Eng. Data 54, 765–775. doi: 10.1021/je800529x

Berendsen, H. J. C., Grigera, J. R., and Straatsma, T. P. (1987). The missing term in effective pair potentials. J. Phys. Chem. 91, 6269–6271. doi: 10.1021/j100308a038

Bonnaud, P. A., Coasne, B., and Pellenq, R. J. (2010). Molecular simulation of water confined in nanoporous silica. J. Phys. Condens. Mat. 22:284110. doi: 10.1088/0953-8984/22/28/284110

Botan, A., Rotenberg, B., Marry, V., Turq, P., and Noetinger, B. (2010). Carbon dioxide in montmorillonite clay hydrates: thermodynamics, structure, and transport from molecular simulation. J. Phys. Chem. C 114, 14962–14969. doi: 10.1021/jp1043305

Bovet, N., Yang, M., Javadi, M. S., and Stipp, S. L. S. (2015). Interaction of alcohols with the calcite surface. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 17, 3490–3496. doi: 10.1039/C4CP05235H

Bui, T., Phan, A., Cole, D. R., and Striolo, A. (2017). Transport mechanism of guest methane in water-filled nanopores. J. Phys. Chem. C 121, 15675–15686. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpcc.7b02713

Côté, A. S., Darkins, R., and Duffy, D. M. (2015). Deformation twinning and the role of amino acids and magnesium in calcite hardness from molecular simulation. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 17, 20178–20184. doi: 10.1039/C5CP03370E

Chakraborty, S., Kumar, H., Dasgupta, C., and Maiti, P. K. (2017). Confined water: structure, dynamics, and thermodynamics. Accounts Chem. Res. 50, 2139–2146. doi: 10.1021/acs.accounts.6b00617

Chialvo, A. A., Vlcek, L., and Cole, D. R. (2012). Aqueous CO2 solutions at silica surfaces and within nanopore environments. Insights from isobaric–isothermal molecular dynamics. J. Phys. Chem. C 116, 13904–13916. doi: 10.1021/jp3001948

Cole, D. R., Ok, S., Phan, A., Rother, G., Striolo, A., and Vlcek, L. (2013). Carbon-bearing fluids at nanoscale interfaces. Proc. Earth Plan. Sci. 7, 175–178. doi: 10.1016/j.proeps.2013.03.226

Darden, T., York, D., and Pedersen, L. (1993). Particle mesh Ewald: an N·log(N) method for Ewald sums in large systems. J. Chem. Phys. 98, 10089–10092. doi: 10.1063/1.464397

Duan, S., Gu, M., Du, X., and Xian, X. (2016). Adsorption equilibrium of CO2 and CH4 and their mixture on Sichuan basin shale. Energy Fuels 30, 2248–2256. doi: 10.1021/acs.energyfuels.5b02088

Duan, Z., and Sun, R. (2003). An improved model calculating CO2 solubility in pure water and aqueous NaCl solutions from 273 to 533 K and from 0 to 2000 bar. Chem. Geol. 193, 257–271. doi: 10.1016/S0009-2541(02)00263-2

Fang, T., Wang, M., Wang, C., Liu, B., Shen, Y., Dai, C., et al. (2017). Oil detachment mechanism in CO2 flooding from silica surface: molecular dynamics simulation. Chem. Eng. Sci. 164, 17–22. doi: 10.1016/j.ces.2017.01.067

Fazelabdolabadi, B., and Alizadeh-Mojarad, A. (2017). A molecular dynamics investigation into the adsorption behavior inside {001} kaolinite and {1014} calcite nano-scale channels: the case with confined hydrocarbon liquid, acid gases, and water. Appl. Nanosci. 7, 155–165. doi: 10.1007/s13204-017-0563-1

Fenter, P., Geissbühler, P., DiMasi, E., Srajer, G., Sorensen, L. B., and Sturchio, N. C. (2000). Surface speciation of calcite observed in situ by high-resolution X-ray reflectivity. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 64, 1221–1228. doi: 10.1016/S0016-7037(99)00403-2

Fenter, P., and Sturchio, N. C. (2004). Mineral–water interfacial structures revealed by synchrotron X-ray scattering. Prog. Surf. Sci. 77, 171–258. doi: 10.1016/j.progsurf.2004.12.001

Franco, L. F., Castier, M., and Economou, I. G. (2016). Anisotropic parallel self-diffusion coefficients near the calcite surface: a molecular dynamics study. J. Chem. Phys. 145:084702. doi: 10.1063/1.4961408

Gadikota, G. (2018). “Multi-scale X-ray scattering for probing chemo-morphological coupling in pore-to-field and process scale energy and environmental applications,” in Small Angle Scattering and Diffraction, eds M. K. K. Dias Franco and F. Yokaichiya (London, UK: Intech Open), 71–83.

Gadikota, G., and Allen, A. (2018). “Microstructural and structural characterization of materials for CO2 storage using multi-scale X-ray scattering methods,” in Materials and Processes for CO2 Capture, Conversion, and Sequestration, eds L. Li and W. Wong-Ng (Hoboken, NJ: Wiley Books), 296–313.

Gadikota, G., Dazas, B., Rother, G., Cheshire, M. C., and Bourg, I. C. (2017). Hydrophobic solvation of gases (CO2, CH4, H2, noble gases) in clay interlayer nanopores. J. Phys. Chem. C 121, 26539–26550. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpcc.7b09768

Geissbühler, P., Fenter, P., DiMasi, E., Srajer, G., Sorensen, L. B., and Sturchio, N. C. (2004). Three-dimensional structure of the calcite–water interface by surface X-ray scattering. Surf. Sci. 573, 191–203. doi: 10.1016/j.susc.2004.09.036

Geysermans, P., and Noguera, C. (2009). Advances in atomistic simulations of mineral surfaces. J. Mater. Chem. 19, 7807–7821. doi: 10.1039/b903642c

Glezakou, V.-A., and McGrail, B. P. (2013). “Density functional simulations as a tool to probe molecular interactions in wet supercritical CO2,” in Applications of Molecular Modeling to Challenges in Clean Energy, Vol. 1133, eds G. Fitzgerald and N. Govind (Washington, DC: American Chemical Society), 31–49.

Granick, S. (1991). Motions and relaxations of confined liquids. Science 253, 1374–1379. doi: 10.1126/science.253.5026.1374

Harris, J. G., and Yung, K. H. (1995). Carbon dioxide's liquid-vapor coexistence curve and critical properties as predicted by a simple molecular model. J. Phys. Chem. B 99, 12021–12024. doi: 10.1021/j100031a034

Headen, T. F., and Boek, E. S. (2010). Molecular dynamics simulations of asphaltene aggregation in supercritical carbon dioxide with and without limonene. Energy Fuels 25, 503–508. doi: 10.1021/ef1010397

Heberling, F., Trainor, T. P., Lützenkirchen, J., Eng, P., Denecke, M. A., and Bosbach, D. (2011). Structure and reactivity of the calcite–water interface. J. Colloid Interf. Sci. 354, 843–857. doi: 10.1016/j.jcis.2010.10.047

Herdes, C., Petit, C., Mejía, M. A., and Muller, E. A. (2018). Combined experimental, theoretical and molecular simulation approach for the description of the fluid phase behavior of hydrocarbon mixtures within shale rocks. Energy Fuels 32, 5750–5762. doi: 10.1021/acs.energyfuels.8b00200

Ho, T. A., and Striolo, A. (2015). Water and methane in shale rocks: flow pattern effects on fluid transport and pore structure. AICHE J. 61, 2993–2999. doi: 10.1002/aic.14869

Hoover, W. G. (1985). Canonical dynamics: equilibrium phase-space distributions. Phys. Rev. A 31:1695.

Hu, Y., Devegowda, D., Striolo, A., Phan, A., Ho, T. A., Civan, F., et al. (2015). The dynamics of hydraulic fracture water confined in nano-pores in shale reservoirs. J. Unconv. Oil Gas Resour. 9, 31–39. doi: 10.1016/j.juogr.2014.11.004

Humphrey, W., Dalke, A., and Schulten, K. (1996). VMD: visual molecular dynamics. J. Mol. Graph. 14, 33–38. doi: 10.1016/0263-7855(96)00018-5

Ishikawa, S., and Tsuchiya, N. (2017). Structure of interfacial water on quartz and its self-diffusion coefficient revealed by molecular dynamics simulations. Proc. Earth Plan. Sci. 17, 853–856. doi: 10.1016/j.proeps.2017.01.036

Javanbakht, G., Sedghi, M., Welch, W., and Goual, L. (2015). Molecular dynamics simulations of CO2/water/quartz interfacial properties: impact of CO2 dissolution in water. Langmuir 31, 5812–5819. doi: 10.1021/acs.langmuir.5b00445

Johnston, C. T. (2017). “Infrared studies of clay mineral-water interactions,” in Developments in Clay Science, Vol. 8, eds W. P. Gates, J. T. Kloprogge, J. Madejová, and F. Bergaya (Amsterdam: Elsevier), 288–309.

Jorgensen, W. L., Maxwell, D. S., and Tirado-Rives, J. (1996). Development and testing of the OPLS all-atom force field on conformational energetics and properties of organic liquids. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 118, 11225–11236. doi: 10.1021/ja9621760

Kadoura, A., Narayanan Nair, A. K., and Sun, S. (2016). Molecular dynamics simulations of carbon dioxide, methane, and their mixture in montmorillonite clay hydrates. J. Phys. Chem. C 120, 12517–12529. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpcc.6b02748

Keller, K. S., Olsson, M. H. M., Yang, M., and Stipp, S. L. S. (2015). Adsorption of ethanol and water on calcite: dependence on surface geometry and effect on surface behavior. Langmuir 31, 3847–3853. doi: 10.1021/la504319z

Le, T., Striolo, A., and Cole, D. R. (2015a). CO2-C4H10 mixtures simulated in silica slit pores: relation between structure and dynamics. J. Phys. Chem. C 119, 15274–15284. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpcc.5b03160

Le, T., Striolo, A., and Cole, D. R. (2015b). Propane simulated in silica pores: adsorption isotherms, molecular structure, and mobility. Chem. Eng. Sci. 121, 292–299. doi: 10.1016/j.ces.2014.08.022

Le, T., Striolo, A., Turner, C. H., and Cole, D. R. (2017). Confinement effects on carbon dioxide methanation: a novel mechanism for abiotic methane formation. Sci. Rep. 7:9021. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-09445-1

Le, T. T. B., Striolo, A., Gautam, S. S., and Cole, D. R. (2017). Propane–water mixtures confined within cylindrical silica nanopores: structural and dynamical properties probed by molecular dynamics. Langmuir 33, 11310–11320. doi: 10.1021/acs.langmuir.7b03093

Lee, M. S., McGrail, B. P., and Glezakou, V. A. (2014). Microstructural response of variably hydrated Ca-rich montmorillonite to supercritical CO2. Environ. Sci. Technol. 48, 8612–8619. doi: 10.1021/es5005889

Lee, M. S., McGrail, B. P., Rousseau, R., and Glezakou, V. A. (2017). Molecular level investigation of CH4 and CO2 adsorption in hydrated calcium–montmorillonite. J. Phys. Chem. C 122, 1125–1134. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpcc.7b05364

Lee, M. S., Peter McGrail, B., Rousseau, R., and Glezakou, V. A. (2015). Structure, dynamics and stability of water/scCO2/mineral interfaces from ab initio molecular dynamics simulations. Sci. Rep. 5:14857. doi: 10.1038/srep14857

Lithoxoos, G. P., Labropoulos, A., Peristeras, L. D., Kanellopoulos, N., Samios, J., and Economou, I. G. (2010). Adsorption of N2, CH4, CO and CO2 gases in single walled carbon nanotubes: a combined experimental and Monte Carlo molecular simulation study. J. Supercrit. Fluid 55, 510–523. doi: 10.1016/j.supflu.2010.09.017

Liu, B., Shi, J., Sun, B., Shen, Y., Zhang, J., Chen, X., et al. (2015). Molecular dynamics simulation on volume swelling of CO2-alkane system. Fuel 143, 194–201. doi: 10.1016/j.fuel.2014.11.046

Liu, B., Shi, J., Wang, M., Zhang, J., Sun, B., Shen, Y., et al. (2016). Reduction in interfacial tension of water–oil interface by supercritical CO2 in enhanced oil recovery processes studied with molecular dynamics simulation. J. Supercrit. Fluid 111, 171–178. doi: 10.1016/j.supflu.2015.11.001

Liu, K., Ostadhassan, M., Zhou, J., Gentzis, T., and Rezaee, R. (2017). Nanoscale pore structure characterization of the Bakken shale in the USA. Fuel 209, 567–578. doi: 10.1016/j.fuel.2017.08.034

Liu, L., Nicholson, D., and Bhatia, S. K. (2015). Adsorption of CH4 and CH4/CO2 mixtures in carbon nanotubes and disordered carbons: a molecular simulation study. Chem. Eng. Sci. 121, 268–278. doi: 10.1016/j.ces.2014.07.041

Makaremi, M., Jordan, K. D., Guthrie, G. D., and Myshakin, E. M. (2015). Multiphase Monte Carlo and molecular dynamics simulations of water and CO2 intercalation in montmorillonite and beidellite. J. Phys. Chem. C 119, 15112–15124. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpcc.5b01754

Malikova, N., Cadène, A., Marry, V., Dubois, E., and Turq, P. (2006). Diffusion of water in clays on the microscopic scale: modeling and experiment. J. Phys. Chem. B 110, 3206–3214. doi: 10.1021/jp056954z

Meldrum, F. C., and Cölfen, H. (2008). Controlling mineral morphologies and structures in biological and synthetic systems. Chem. Rev. 108, 4332–4432. doi: 10.1021/cr8002856

Mohammed, S., and Mansoori, G. A. (2018a). Effect of CO2 on the interfacial and transport properties of water/binary and asphaltenic oils: insights from molecular dynamics. Energy Fuels 32, 5409–5417. doi: 10.1021/acs.energyfuels.8b00488

Mohammed, S., and Mansoori, G. A. (2018b). The role of supercritical/dense CO2 Gas in altering aqueous/oil interfacial properties: a molecular dynamics study. Energy Fuels 32, 2095–2103. doi: 10.1021/acs.energyfuels.7b03863

Mohammed, S., and Mansoori, G. A. (2018c). Molecular insights on the interfacial and transport properties of supercritical CO2/brine/crude oil ternary system. J. Mol. Liq. 263, 268–273. doi: 10.1016/j.molliq.2018.05.009

Molyanyan, E., Aghamiri, S., Talaie, M. R., and Iraji, N. (2016). Experimental study of pure and mixtures of CO2 and CH4 adsorption on modified carbon nanotubes. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 13, 2001–2010. doi: 10.1007/s13762-016-0989-0

Moultos, O. A., Tsimpanogiannis, I. N., Panagiotopoulos, A. Z., and Economou, I. G. (2014). Atomistic molecular dynamics simulations of CO2 diffusivity in H2O for a wide range of temperatures and pressures. J. Phys. Chem. B 118, 5532–5541. doi: 10.1021/jp502380r

Moultos, O. A., Tsimpanogiannis, I. N., Panagiotopoulos, A. Z., and Economou, I. G. (2016). Self-diffusion coefficients of the binary (H2O+ CO2) mixture at high temperatures and pressures. J. Chem. Thermodyn. 93, 424–429. doi: 10.1016/j.jct.2015.04.007

Mutisya, S. M., Kirch, A., de Almeida, J. M., Sánchez, V. M., and Miranda, C. R. (2017). Molecular dynamics simulations of water confined in calcite slit pores: an NMR spin relaxation and hydrogen bond analysis. J. Phys. Chem. C 121, 6674–6684. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpcc.6b12412

Myshakin, E. M., Saidi, W. A., Romanov, V. N., Cygan, R. T., and Jordan, K. D. (2013). Molecular dynamics simulations of carbon dioxide intercalation in hydrated Na-montmorillonite. J. Phys. Chem. C 117, 11028–11039. doi: 10.1021/jp312589s

Nosé, S. (1984). A molecular dynamics method for simulations in the canonical ensemble. Mol. Phys. 52, 255–268. doi: 10.1080/00268978400101201

Obliger, A., Ulm, F. J., and Pellenq, R. J. M. (2018). Impact of nanoporosity on hydrocarbon transport in shales' organic matter. Nano Lett. 18, 832–837. doi: 10.1021/acs.nanolett.7b04079

Ou, X., Li, J., and Lin, Z. (2014). Dynamic behavior of interfacial water on Mg (OH)2 (001) surface: a molecular dynamics simulation work. J. Phys. Chem. C 118, 29887–29895. doi: 10.1021/jp509373d

Parrinello, M., and Rahman, A. (1982). Strain fluctuations and elastic constants. J. Chem. Phys. 76, 2662–2666. doi: 10.1063/1.443248

Peng, D. Y., and Robinson, D. B. (1976). A new two-constant equation of state. Ind. Eng. Chem. Fund. 15, 59–64. doi: 10.1021/i160057a011

Rao, Q., and Leng, Y. (2016). Molecular understanding of CO2 and H2O in a montmorillonite clay interlayer under CO2 geological sequestration conditions. J. Phys. Chem. C, 120, 2642–2654. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpcc.5b09683

Relat-Goberna, J., and Garcia-Manyes, S. (2015). Direct observation of the dynamics of self-assembly of individual solvation layers in molecularly confined liquids. Phys. Rev. Lett. 114:258303. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.114.258303

Ryckaert, J. P., Ciccotti, G., and Berendsen, H. J. (1977). Numerical integration of the cartesian equations of motion of a system with constraints: molecular dynamics of n-alkanes. J. Comput. Phys. 23, 327–341. doi: 10.1016/0021-9991(77)90098-5

Saha, D., Bao, Z., Jia, F., and Deng, S. (2010). Adsorption of CO2, CH4, N2O, and N2 on MOF-5, MOF-177, and zeolite 5A. Environ. Sci. Technol. 44, 1820–1826. doi: 10.1021/es9032309

Sakamaki, R., Sum, A. K., Narumi, T., Ohmura, R., and Yasuoka, K. (2011). Thermodynamic properties of methane/water interface predicted by molecular dynamics simulations. J. Chem. Phys. 134:144702. doi: 10.1063/1.3579480

Schaef, H. T., Glezakou, V. A., Owen, A. T., Ramprasad, S., Martin, P. F., and McGrail, B. P. (2013). Surface condensation of CO2 onto kaolinite. Environ. Sci. Tech. Lett. 1, 142–145. doi: 10.1021/ez400169b

Schaef, H. T., Loring, J. S., Glezakou, V. A., Miller, Q. R., Chen, J., Owen, A. T., et al. (2015). Competitive sorption of CO2 and H2O in 2: 1 layer phyllosilicates. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 161, 248–257. doi: 10.1016/j.gca.2015.03.027

Simoes Santos, M., Franco, L., Castier, M., and Economou, I. G. (2018). Molecular dynamics simulation of n-alkanes and CO2 confined by calcite nanopores. Energy Fuels 32, 1934–1941. doi: 10.1021/acs.energyfuels.7b02451

Skarmoutsos, I., Tamiolakis, G., and Froudakis, G. E. (2013). Carbon-based nanoporous networks as media for the separation of CO2/CH4 mixtures: a molecular dynamics approach. J. Phys. Chem. C 117, 19373–19381. doi: 10.1021/jp401978m

Striolo, A., and Cole, D. R. (2017). Understanding shale gas: recent progress and remaining challenges. Energy Fuels 31, 10300–10310. doi: 10.1021/acs.energyfuels.7b01023

Sun, H., Sun, W., Zhao, H., Sun, Y., Zhang, D., Qi, X., et al. (2016a). Adsorption properties of CH4 and CO2 in quartz nanopores studied by molecular simulation. RSC Adv. 6, 32770–32778. doi: 10.1039/C6RA05083B

Sun, H., Zhao, H., Qi, N., and Li, Y. (2017). Effects of surface composition on the microbehaviors of CH4 and CO2 in slit-nanopores: a simulation exploration. ACS Omega 2, 7600–7608. doi: 10.1021/acsomega.7b01185

Sun, H., Zhao, H., Qi, N., Qi, X., Zhang, K., Sun, W., et al. (2016b). Mechanistic insight into the displacement of CH4 by CO2 in calcite slit nanopores: the effect of competitive adsorption. RSC Adv. 6, 104456–104462. doi: 10.1039/C6RA23456A

Versteeg, G. F., and Van Swaaij, W. P. (1988). Solubility and diffusivity of acid gases (carbon dioxide, nitrous oxide) in aqueous alkanolamine solutions. J. Chem. Eng. Data 33, 29–34. doi: 10.1021/je00051a011

Vlcek, L., Chialvo, A. A., and Cole, D. R. (2011). Optimized unlike-pair interactions for water–carbon dioxide mixtures described by the SPC/E and EPM2 models. J. Phys. Chem. B 115, 8775–8784. doi: 10.1021/jp203241q

Wang, H., Wang, X., Jin, X., and Cao, D. (2016). Molecular dynamics simulation of diffusion of shale oils in montmorillonite. J. Phys. Chem. C 120, 8986–8991. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpcc.6b01660

Wang, S., Feng, Q., Javadpour, F., and Yang, Y. B. (2016a). Breakdown of fast mass transport of methane through calcite nanopores. J. Phys. Chem. C 120, 14260–14269. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpcc.6b05511

Wang, S., Feng, Q., Zha, M., Javadpour, F., and Hu, Q. (2017). Supercritical methane diffusion in shale nanopores: effects of pressure, mineral types, and moisture content. Energy Fuels 32, 169–180. doi: 10.1021/acs.energyfuels.7b02892

Wang, S., Zhou, G., Ma, Y., Gao, L., Song, R., Jiang, G., et al. (2016b). Molecular dynamics investigation on the adsorption behaviors of H2O, CO2, CH4 and N2 gases on calcite (1 1− 0) surface. Appl. Surf. Sci. 385, 616–621. doi: 10.1016/j.apsusc.2016.05.026

Wiesenburg, D. A., and Guinasso, N. L. Jr. (1979). Equilibrium solubilities of methane, carbon monoxide, and hydrogen in water and sea water. J. Chem Eng. Data, 24, 356–360. doi: 10.1021/je60083a006

Wu, H., Chen, J., and Liu, H. (2015). Molecular dynamics simulations about adsorption and displacement of methane in carbon nanochannels. J. Phys. Chem. C, 119, 13652–13657.

Xiao, S. E., Edwards, S. A., and Grater, F. (2011). A new transferable forcefield for simulating the mechanics of CaCO3 crystals. J. Phys. Chem. C 115, 20067–20075. doi: 10.1021/jp202743v

Xing, J., Hu, S., Jiang, Z., Wang, X., Wang, J., Sun, L., et al. (2018). Classification of controlling factors and determination of a prediction model for shale gas adsorption capacity: a case study of Chang 7 shale in the Ordos Basin. J. Nat. Gas. Sci. Eng. 49, 260–274. doi: 10.1016/j.jngse.2017.11.015

Xu, T., Apps, J. A., and Pruess, K. (2005). Mineral sequestration of carbon dioxide in a sandstone–shale system. Chem. Geol. 217, 295–318. doi: 10.1016/j.chemgeo.2004.12.015

Yang, N., Liu, S., and Yang, X. (2015). Molecular simulation of preferential adsorption of CO2 over CH4 in Na-montmorillonite clay material. Appl. Surf. Sci. 356, 1262–1271. doi: 10.1016/j.apsusc.2015.08.101

Yasuda, K., Mori, Y. H., and Ohmura, R. (2016). Interfacial tension measurements in water– methane system at temperatures from 278.15 K to 298.15 K and pressures up to 10 MPa. Fluid Phase Equilibr. 413, 170–175. doi: 10.1016/j.fluid.2015.10.006

Yuan, Q., Zhu, X., Lin, K., and Zhao, Y. P. (2015). Molecular dynamics simulations of the enhanced recovery of confined methane with carbon dioxide. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 17, 31887–31893. doi: 10.1039/C5CP06649B

Zhao, L., Lin, S., Mendenhall, J. D., Yuet, P. K., and Blankschtein, D. (2011). Molecular dynamics investigation of the various atomic force contributions to the interfacial tension at the supercritical CO2-water interface. J. Phys. Chem. B 115, 6076–6087. doi: 10.1021/jp201190g

Keywords: structure, diffusivity, carbon dioxide, methane, confined water, calcite

Citation: Mohammed S and Gadikota G (2018) The Effect of Hydration on the Structure and Transport Properties of Confined Carbon Dioxide and Methane in Calcite Nanopores. Front. Energy Res. 6:86. doi: 10.3389/fenrg.2018.00086

Received: 11 May 2018; Accepted: 08 August 2018;

Published: 30 August 2018.

Edited by:

David J. Heldebrant, Pacific Northwest National Laboratory (DOE), United StatesReviewed by:

Junfeng Wang, Institute of Process Engineering (CAS), ChinaCopyright © 2018 Mohammed and Gadikota. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Greeshma Gadikota, Z2FkaWtvdGFAd2lzYy5lZHU=

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.