- 1Center for Clinical Epidemiology and Methodology (CCEM), Guangdong Second Provincial General Hospital, Guangzhou, China

- 2Department of Laboratory Medicine and Central Laboratories, Guangdong Second Provincial General Hospital, Guangzhou, China

- 3Department of Medical Statistics and Epidemiology, School of Public Health, Sun Yat-sen University, Guangzhou, China

- 4Department of Health Research Methods, Evidence, and Impact (HEI), McMaster University, Hamilton, ON, Canada

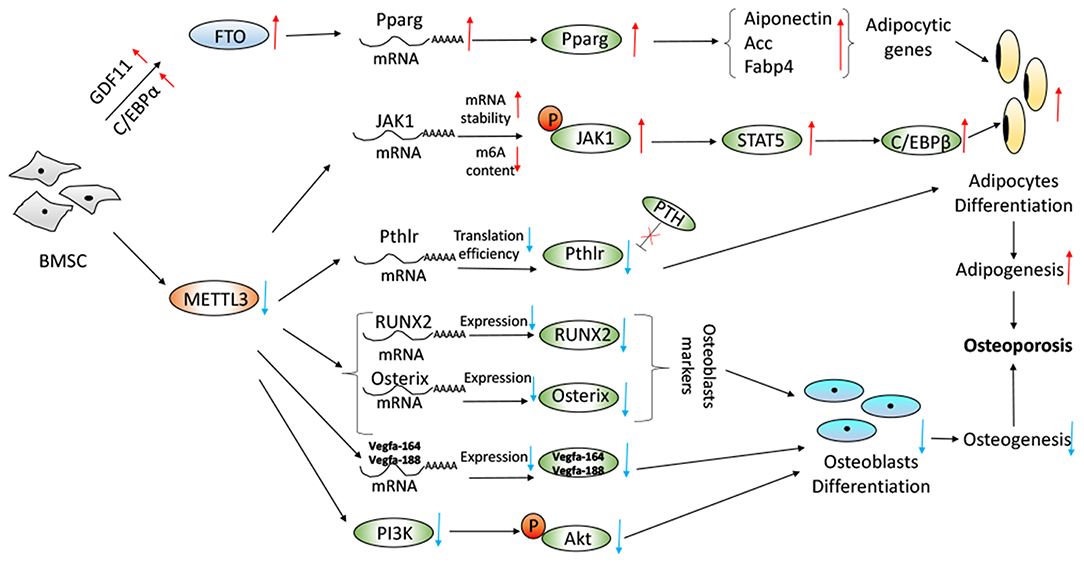

Osteoporosis is a metabolic skeletal disorder in which bone mass is depleted and bone structure is destroyed to the degree that bone becomes fragile and prone to fractures. Emerging evidence suggests that N6-methyladenosine (m6A) modification, a novel epitranscriptomic marker, has a significant role in bone development and metabolism. M6A modification not only participates in bone development, but also plays important roles as writers and erasers in the osteoporosis. M6A methyltransferase METTL3 and demethyltransferase FTO involves in the delicate process between adipogenesis differentiation and osteogenic differentiation, which is important for the pathological development of osteoporosis. Conditional knockdown of the METTL3 in bone marrow stem cells (BMSCs) could suppress PI3K-Akt signaling, limit the expression of bone formation-related genes (such as Runx2 and Osterix), restrain the expression of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and down-regulate the decreased translation efficiency of parathyroid hormone receptor-1 mRNA. Meanwhile, knockdown of the METTL3 significantly promoted the adipogenesis process and janus kinase 1 (JAK1) protein expression via an m6A-dependent way. Specifically, there was a negative correlation between METTL3 expression and porcine BMSCs adipogenesis. The evidence above suggested that the relationship between METTL3 expression and adipogenesis was inverse, and osteogenesis was positive, respectively. Similarly, FTO regulated for BMSCs fate determination during osteoporosis through the GDF11-FTO-PPARγ axis, prompting the shift of MSC lineage commitment to adipocyte and inhibiting bone formation during osteoporosis. In this systematic review, we summarize the most up-to-date evidence of m6A RNA modification in osteoporosis and highlight the potential role of m6A in prevention, treatment, and management of osteoporosis.

Introduction

Osteoporosis is a systemic skeletal disease characterized by decrease in bone mineral density (BMD) and deterioration in bone microarchitecture (1, 2). It is a complex multifactorial disorder due to an interaction between genetic and environmental factors, dietary habits, and lifestyle. Patients suffer from chronic pain and decreased quality of life (3). Osteoporotic fractures increase disability, mortality, and health-care cost, especially among elder peoples (4). For example, the cumulative mortality after 1 year of an osteoporotic hip fracture occurrence varies between 20 and 40% (5). Due to its silent nature, osteoporosis is often under-diagnosed and under-managed, which needs immediate attention.

Epigenetics is the study of heritable changes in gene expression that do not involve alterations in the DNA/RNA sequence, including DNA methylation, histone modification, and RNA modification (6, 7). As a consequence of gene–environment interactions, various environmental factors could trigger different epigenetic processes which regulate gene transcription (8, 9). Among them, DNA methylation and demethylation are the most extensively studied, especially alteration in the methylation of cytosine nucleotides in CpG islands located in the promoter region of genes. Hypomethylation of the cytosine bases of the DNA promoter sequence in CpG islands activates gene expression, and hypermethylation silences gene expression (8, 10). Aberrant DNA methylation patterns can result in developmental disorders (11). Modification of histone molecules within chromatin plays important roles in regulating gene expression. Enzymes, including histone acetyltransferases (HAT), histone methyltransferases (HMT), histone deacetylases (HDAC), histone demethylases (HDM), and others, could modify histones to alter gene expression by regulating promoter activity, chromatin structure, dosage compensation, and epigenetic memory, without changes in the nucleic acid sequences (8, 12). Moreover, epigenetic factors are also involved in bone biology and osteoporosis, which play a bridging role between individual genetic aspects and environmental influences (13).

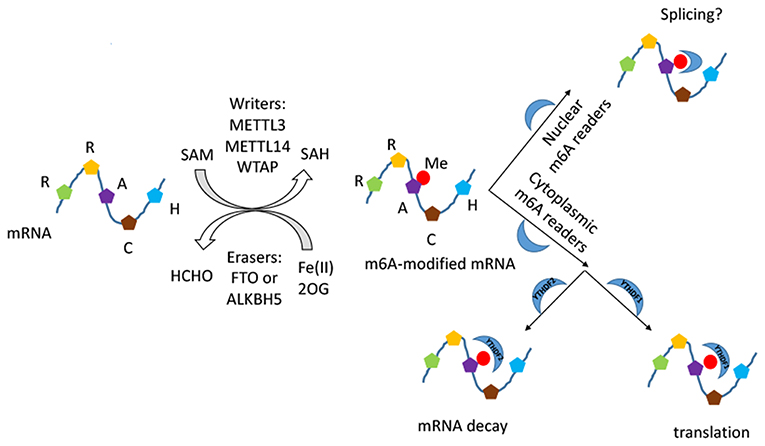

RNA modification is another important post-transcriptional regulation, among which N6-methyladenosine (m6A) modification of mRNA is one of the most highly abundant (14, 15). First reported in 1970s, m6A modification was found to have a broad functional influence on stabilizing homeostasis closely correlated to post-transcriptional gene expression regulation, growth and development (14, 16–20). It regulates the metabolic processes of most RNAs, including the pre-mRNA splicing, mRNA export, turnover, and translation of mRNA (18, 21–23). M6A modification is tightly closely correlated to fundamental biological processes such as adipogenesis (24–26), mammalian spermatogenesis development (27), RNA dynamics of T cells (28), pluripotency differentiation (29–35), and response to heat shock (36, 37). Moreover, it was found to get involved in the etiology of various diseases including cancers (36, 38, 39), systemic lupus erythematosus (40), rheumatoid arthritis (16), and coronary artery disease (41). It was revealed that m6A modification commonly occurred at the consensus motif RRACH (R = A, G; H = A, C, U) (14, 40). The process is catalyzed by the orchestrated action of highly conserved methyltransferase (m6A writers) and demethylase (m6A erasers) enzymes (42). M6A writer is composed of a METTL3 (methyltransferase-like3)-METTL14 (methyltransferase-like 14)-WTAP (Wilm's tumor–associated protein) complex (43–45). Two members of the Fe(II)- and 2-oxoglutarate-dependent oxygenase superfamily, FTO and ALKBH5, act as m6A erasers (46). N6-methyladenosine (m6A) reader proteins of the YTH family serve as recognition elements for the effector proteins. YTHDF1/3 enhance translation efficiency of methylated mRNAs, while YTHDF2 promotes mRNA decay (6) (Figure 1). Recently, it is demonstrated that the DNA demethylase ALKBH1 play an unexpected role in modulating hypoxia-induced genes in human glioblastoma. M6A modification of DNA modification is markedly upregulated and highly associated with the H3K9me3 heterochromatin histone modification in human glioblastoma (47).

Figure 1. The schematic diagram of m6A RNA modification. The process is composed of installation, removal, and identification performed by writers, erasers, and readers. The METTL3–METTL14–WTAP methyltransferase complex catalyses a methyl group transfered from SAM into the N6 position, and the demethylases FTO and ALKBH5 catalyse the oxidative demethylation from methylated adenosine. The methyl group introduced is marked in red. The readers of the YTH domain family are effectors that decode the m6A methylation code and transform it into a functional signal in nucleus and cytoplasm.

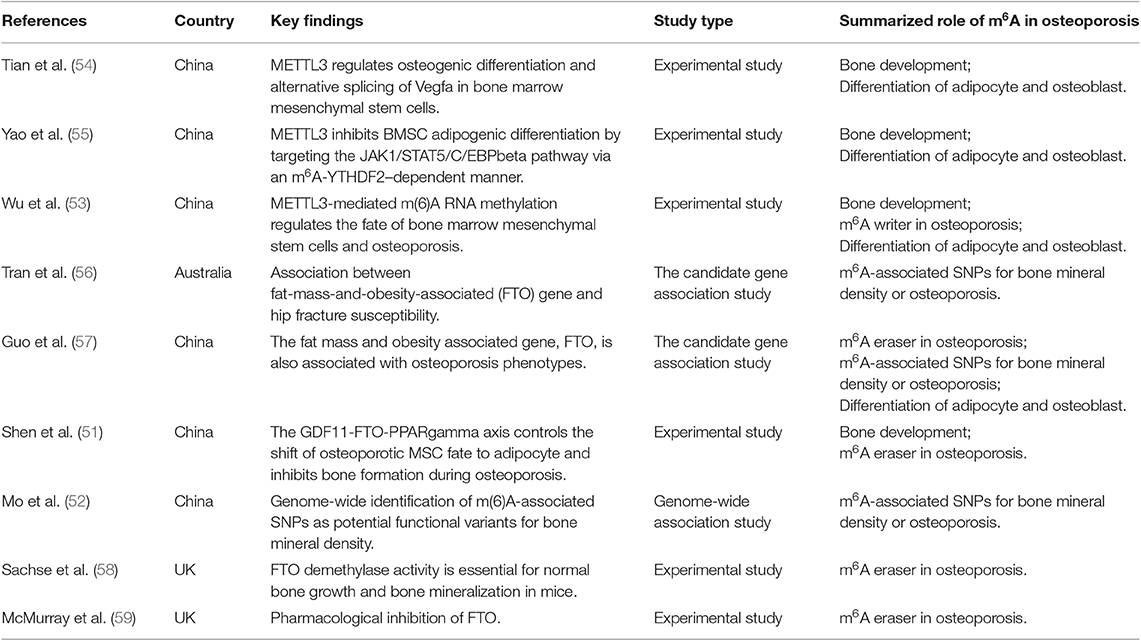

It has been shown that DNA methylation and posttranslational histone modification participant in gene expression of bone cells (48, 49). These epigenetic programs are essential for physiological and pathological process, such as bone remodeling and bone metabolic disorders (6, 50). Besides, there is growing evidence that m6A modification is a potential pathogenesis mechanism in osteoporosis (51–53). We systematically searched PubMed and EMBASE (up to July 2019) using keywords “(mRNA modifications OR epitranscriptomics OR N6-methyladenosine modification OR m6A modification OR m6A OR FTO OR Mettl3) AND (bone OR osteoporosis OR bone marrow stem cells OR BMSCs OR bone mineral density OR BMD)” to decipher the role of m6A modification in osteoporosis, which might help further understand the pathogenesis of osteoporosis and provide theoretical basis for potential epigenetic-based therapeutics of osteoporosis. The inclusion criteria was: (1) to evaluate the association between RNA N6-methyladenosine modification in bone biology and osteoporosis; (2) full-text articles; (3) sufficient data on the regulatory mechanism. We identified 223 and 103 citations in PubMed and EMBASE, respectively. After removing 32 duplicates, 294 citations remained for title and abstract screening, from which nine articles were retrieved for full text screening (Table 1). Studies excluded due to not associated with RNA N6-methyladenosine modification in bone biology and osteoporosis (n = 247), reviews (n = 26), meta-analysis (n = 2), letters (n = 1), case reports (n = 2), meeting abstracts (n = 4), protocol (n = 1), and clinical trials (n = 2). Of the nine relevant studies, six were experimental studies, two were the candidate gene association studies and one was genome-wide association study. Based on the nine included studies, we discussed five parts below in detail related to m6A modification and osteoporosis in this systematic review.

Table 1. Summary of included studies about the regulatory role of m6A mRNA modification in osteoporosis.

M6A Modification Regulates Bone Development

M6A modification of mRNAs has been discovered as a reversible RNA methylation and is widely conserved in mammalian cells (15, 42, 60). It is the most prevalent and internal modification that is tightly related to fundamental biological processes (Figure 1). M6A has recently been reported to play a part in pluripotency differentiation and development of the cell lineage (29, 30, 32, 33), including osteogenic differentiation of bone marrow stem cells (BMSCs) (51, 53, 54). The human skeleton is a metabolically active tissue that undergoes continuous turnover and remodeling throughout life (48). Under homeostatic conditions, there is a delicate balance between osteoblast-mediated bone regeneration and osteoclast-mediated bone resorption (61, 62). Abnormalities of this process can produce a variety of skeletal disorders (63). BMSCs, also known as bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells, are multipotent stromal cells with the ability of differentiating into osteoblast, chondrocyte, and adipocyte both in vitro and in vivo (64). In normal conditions, that would be a dynamic equilibrium for their differentiation of adipocytes and osteoblasts (65).

Recently, Yao et al. found that METTL3 plays an important role in BMSCs differentiation and adipogenesis. There was a negative correlation between METTL3 expression and porcine BMSCs (pBMSCs) adipogenesis (55). Specifically, METTL3 inhibited pBMSCs adipogenic differentiation by targeting the JAK1/STAT5/C/EBPβ pathway via an m6A-YTHDF2–dependent manner. It was demonstrated that the deletion of METTL3 significantly promoted the pBMSCs adipogenesis process and janus kinase 1 (JAK1) protein expression via an m6A-dependent way (55) (Figure 2). Similarly, in Tian's study, it was shown that METTL3 was highly expressed in osteogenically differentiated BMSCs (54). METTL3 knockdown limited the expression of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and its bone formation-related splice variants (Vegfa-164 and Vegfa188) in osteoblast-induced BMSCs, which was implicated in the maturation of osteoblasts, ossification and bone turnover. METTL3 knockdown decreased the expression of bone formation-related genes (such as Runx2 and Osterix), Akt phosphorylation, the alkaline phosphatase activity and the formation of mineralized nodules. PI3K-Akt signaling was suppressed by METTL3 knockdown in BMSCs during the osteogenic differentiation process (54) (Figure 2). Furthermore, METTL3 had a functional role in osteoarthritis progression by regulating NF-kB signaling and extracellular matrix synthesis in chondrocytes (66). RNA demethylase AlkB Homolog 5 (ALKBH5) was amplified in sarcomas and its expression was highly elevated in osteosarcoma patients. Silencing of ALKBH5 inhibited the osteosarcoma growth and migration without affecting the viability of normal human fetal osteoblast cells by sensitizing osteosarcoma cells to DNA damaging agents (67). Moreover, METTL3 promoted osteosarcoma cell progression by regulating the m6A level of lymphoid enhancer-binding factor 1and activating Wnt/b-catenin signaling pathway (68).

Figure 2. Proposed model depicting regulation and role of METTL3 and FTO in BMSC adipogenesis and osteogenesis with regard to osteoporosis. Working model of the mechanism of METTL3 knockdown increased JAK1/STAT5/C/EBPb pathway, decreased PTH/Pth1r signaling axis, decreased expression of RUNX2, Osterix, and Vegfa and decreased PI3K-Akt signaling pathway. Overexpression of FTO in a GDF11-C/EBPα-dependent mechanism resulted in increase of the Pparg mRNA and the promotion of adipogenesis.

M6A Writers in Osteoporosis

Wu et al. reported that METTL3-mediated m6A RNA methylation could regulate the fate of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells and osteoporosis (53). Conditional knockout of the m6A methyltransferase METTL3 in BMSCs induced pathological features of osteoporosis in mice and resulted in impaired bone formation, incompetent osteogenic differentiation potential, and increased marrow adiposity. Conversely, METTL3 overexpression in BMSCs protected the mice from estrogen deficiency-induced osteoporosis. METTL3 depletion resulted in the decreased translation efficiency of parathyroid hormone receptor-1 mRNA. M6A affected both osteogenic and adipogenic differentiation of MSCs through PTH (parathyroid hormone)/Pth1r (parathyroid hormone receptor-1) signaling axis. METTL3 knockout reduced the translation efficiency of MSCs lineage allocator Pth1r, leading to reduction of the global methylation level of m6A and disruption of the PTH-induced osteogenic and adipogenic responses. PTH, bone-promoting molecule, stimulates bone formation by activating the HSP90-dependent PERK-EIF2α-ATF4 signaling pathway (69) and increasing the receptor activator of nuclear factor κ-B ligand (RANKL)/osteoprotegerin (OPG) ratio through its receptor (70). M6A modification was required for Pth1r translation. Loss of METTL3 changed Pth1r mRNA from the polysome fractions to the sub-polysome fractions (71), leading to slowing down the protein synthesis of Pth1r and blocking the downstream signaling pathways of Pth1r responsive to PTH treatment (53). The regulatory mechanism was shown in Figure 2.

M6A Erasers in Osteoporosis

As an m6A eraser, FTO was associated with osteoporosis phenotypes (57). It was founded that the whole body FTO knockout mice appeared as immediate postnatal growth retardation with shorter body length, lower body weight, and lower bone mineral density (BMD) (72). As Sachse et al. showed that FTO catalytic was essential for normal bone growth and mineralization but was not required for normal body composition except for normal body size and viability (58). They found both BMD and BMC (bone mineral content) were reduced in FTO knockout mice, which was comparable to that seen in osteoporosis. It was indicated that a relatively small amount of catalytic activity, roughly 20–50%, was sufficient to rescue the bone phenotype (58).

Moreover, Shen et al. have reported that FTO was a regulator for BMSCs fate determination during osteoporosis, with a rise in bone marrow in a growth-differentiation factor 11 (GDF11)-C/EBPα-dependent mechanism. Increased serum GDF11 concentration was associated with a high prevalence of osteoporosis by stimulating osteoclastogenesis and inhibiting osteoblast through inducing Smad2/3 phosphorylation (73–75). Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPARγ) promoted the adipocyte differentiation and inhibited osteoblast differentiation from BMSCs (76, 77). The GDF11-FTO-PPARγ axis prompted the shift of MSC lineage commitment to adipocyte and inhibited bone formation during osteoporosis, as a result of the imbalance between bone mass and fat. FTO expression resulted in the increase of the serum concentration of GDF11 in the bone, which was a key risk for osteoporosis. The GDF11-FTO signaling regulated the adipocyte and osteoblast differentiation of MSC by targeting PPARγ dependent of the m6A demethylase activity of FTO. Knock down the expression of FTO by means of lentivirus-mediated shRNA in BMSCs blocked the function of GDF11 and reduced the cells to differentiate to adipocytes. FTO knockout repressed the development of osteopenia in vivo through upregulation of adipocytic and down-regulation of an osteoblastic gene. FTO could regulate the m6A level of the transcriptional factor PPARγ mRNA. Aging and osteopenia were associated with a decline in m6A content in total RNA, which was consistent with the up-regulation of FTO expression (51). McMurray et al. conducted an evaluation to examine the effect of FTO demethylase function, and they found that pharmacologically inhibition FTO with IOX3 did significantly reduce BMD, BMC, and alter adipose tissue distribution. The level of alkaline phosphatase, an indicator of osteoblast function (61), was increased after use of IOX3 in mice compared with the controls (59). The process was revealed in Figure 2.

Identification of m6A-associated SNPs for Bone Mineral Density or Osteoporosis

FTO polymorphisms are associated with elevated body mass index and increased risk for obesity (78, 79). Based on the candidate gene association study, FTO gene was found to be associated with hip fracture susceptibility (57). Specifically, researchers analyzed six single nucleotide polymorphisms (rs1421085, rs1558902, rs1121980, rs17817449, rs9939609, and rs9930506) of the FTO gene and found that female carriers of rs1121980 AA genotype had significantly higher risk of hip fracture with a hazard ratio of 2.06 (95% CI 1.17–3.62) than the female carriers of the wild-type. It was reported that ~17% of the variability in hip fracture risk was attributable to SNP rs1121980. The FTO gene might be a new candidate for BMD variation and osteoporosis in Chinese population, as a candidate genetic marker for peak bone mass acquisition (56). In Zhang's study, it was demonstrated that osteoblast expression of FTO was required for normal bone formation and maintenance of bone mass in mature mice. The results identified an epigenetic pathway in which FTO normally functioned in bone to enhance the stability of mRNA-encoding proteins that protected osteoblasts from genotoxic damage (80). Utilizing the Mendelian randomization analysis, it was founded that the FTO-BMI polymorphism (rs9939609), as an instrument, was significantly associated with total hip and femoral neck BMD but was not correlated with total spine BMD (81). In aggregate, it was revealed that FTO SNPs were not only associated with obesity and type 2 diabetes but also with the BMD at the hip (57, 79).

Currently, based on genome-wide association study, plenty of m6A-associated SNPs were identified as potential functional variants for BMD (52). Mo et al. found that 138, 125, and 993 m6A-SNPs were associated with the BMD of femoral neck, lumbar spine, and quantitative heel ultrasounds, respectively. Among them, the association between two genes (MIR196A2 and ESPL1) and BMD of lumbar spine reached the genome-wide significant level [rs11614913 (P = 8.92 × 10−10) and rs1110720 (P = 2.05 × 10−10), respectively] (52). Furthermore, expression quantitative trait locus analyses indicated that 47 of these BMD-associated m6A-SNPs were related with expressions of the 46 corresponding local genes. Besides, 24 m6A-SNPs were founded to be significantly associated with quantitative heel ultrasounds (P < 5.0 × 10−8) (52). This study provided new clues for further understanding of functional mechanism underlying the associations between SNPs and osteoporosis.

M6A Modification in the Differentiation of Adipocyte and Osteoblast

Obesity and osteoporosis are closely correlated genetically (82–87). BMSCs is the same progenitor for adipocytes and osteoblasts and osteoblasts can also differentiate into adipocytes (87). Candidate genes, such as RANK (88), SP7 (89), and SOX6 (90), are all associated with obesity and osteoporosis. FTO affected not only obesity phenotypes, but also osteoporosis phenotypes, like BMD (57). FTO-knockout mice showed a significant reduction in adipose tissue and body lean mass (91), and in turn, reduced lean mass is associated with weaken femur bone strength (92). METTL3-mediated m6A RNA methylation also participated in the delicate process between pBMSCs adipogenesis differentiation and osteogenic differentiation (53–55, 66). BMI might be the causative role in osteoporosis the same as osteoarthritis on the effect of FTO variation (93). Recently, using a Mendelian randomization approach, Kemp et al. found that fat mass/BMI was strongly positively related to increased bone mineral density of the limbs, pelvis, and spine, but not the skull. In contrast, they reported that no evidence showed BMD could causally affect BMI or measures of adiposity (94). Taken together, m6A modification was closely related to the differentiation of adipocyte and osteoblast, which was important for the pathological development of osteoporosis.

Concluding Remarks

Osteoporosis is a major public health concern with growing prevalence. Studies have indicated the important role of m6A modification in prevention, treatment and management of osteoporosis; however, more endeavors are needed to further understand the mechanism and clarify the relationship between m6A modification and osteoporosis.

Author Contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct and intellectual contribution to the work, and approved it for publication.

Funding

Research grant from the Science Foundation of Guangdong Second Provincial General Hospital (YY2018-002).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

1. Gosch M, Kammerlander C, Neuerburg C. Osteoporosis-epidemiology and quality of care. Z Gerontol Geriatr. (2019) 52:408–13. doi: 10.1007/s00391-019-01559-7

2. Wicklein S, Gosch M. Osteoporosis and multimorbidity. Z Gerontol Geriatr. (2019) 52:433–9. doi: 10.1007/s00391-019-01569-5

3. Wang J, Lu HX, Wang J. Cannabinoid receptors in osteoporosis and osteoporotic pain: a narrative update of review. J Pharm Pharmacol. (2019) 71:1469–74. doi: 10.1111/jphp.13135

4. Cho H, Byun JH, Song I, Kim HY, Ha YC, Kim TY, et al. Effect of improved medication adherence on health care costs in osteoporosis patients. Medicine. (2018) 30:e11470. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000011470

5. Guzon-Illescas O, Perez Fernandez E, Crespi Villarias N, Quiros Donate FJ, Pena M, Alonso-Blas C. Mortality after osteoporotic hip fracture: incidence, trends, and associated factors. J Orthop Surg Res. (2019) 1:203. doi: 10.1186/s13018-019-1226-6

6. Arguello AE, Leach RW, Kleiner RE. In vitro selection with a site-specifically modified RNA library reveals the binding preferences of N(6)-methyladenosine (m6A) reader proteins. Biochemistry. (2019) 31:3386–95. doi: 10.1021/acs.biochem.9b00485

7. McGee SL, Hargreaves M. Epigenetics and exercise. Trends Endocrinol Metab. (2019) doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2019.06.002

8. Goyal D, Limesand SW, Goyal R. Epigenetic responses and the developmental origins of health and disease. J Endocrinol. (2019) 1:T105–19. doi: 10.1530/JOE-19-0009

9. Perera BPU, Faulk C, Svoboda LK, Goodrich JM, Dolinoy DC. The role of environmental exposures and the epigenome in health and disease. Environ Mol Mutagen. (2019). doi: 10.1002/em.22311. [Epub ahead of print].

10. Zeng Y, Chen T. DNA methylation reprogramming during mammalian development. Genes. (2019) 4:E257. doi: 10.3390/genes10040257

11. Hamidi T, Singh AK, Chen T. Genetic alterations of DNA methylation machinery in human diseases. Epigenomics. (2015) 2:247–65. doi: 10.2217/epi.14.80

12. Martin C, Zhang Y. The diverse functions of histone lysine methylation. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. (2005) 11:838–49. doi: 10.1038/nrm1761

13. Marini F, Cianferotti L, Brandi ML. Epigenetic mechanisms in bone biology and osteoporosis: can they drive therapeutic choices? Int J Mol Sci. (2016) 8:E1329. doi: 10.3390/ijms17081329

14. Roundtree IA, He C. RNA epigenetics–chemical messages for posttranscriptional gene regulation. Curr Opin Chem Biol. (2016) 30:46–51. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2015.10.024

15. Pan T. N6-methyl-adenosine modification in messenger and long non-coding RNA. Trends Biochem Sci. (2013) 4:204–9. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2012.12.006

16. Mo XB, Zhang YH, Lei SF. Genome-wide identification of N(6)-Methyladenosine (m6A) SNPs associated with rheumatoid arthritis. Front Genet. (2018) 9:299. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2018.00299

17. Hsu PJ, Shi H, He C. Epitranscriptomic influences on development and disease. Genome Biol. (2017) 1:197. doi: 10.1186/s13059-017-1336-6

18. Wei W, Ji X, Guo X, Ji S. Regulatory role of N(6) -methyladenosine (m6A) methylation in RNA processing and human diseases. J Cell Biochem. (2017) 9:2534–43. doi: 10.1002/jcb.25967

19. Chandola U, Das R, Panda B. Role of the N6-methyladenosine RNA mark in gene regulation and its implications on development and disease. Brief Funct Genomics. (2015) 3:169–79. doi: 10.1093/bfgp/elu039

20. Dominissini D, Moshitch-Moshkovitz S, Schwartz S, Salmon-Divon M, Ungar L, Osenberg S, et al. Topology of the human and mouse m6A RNA methylomes revealed by m6A-seq. Nature. (2012) 7397:201–6. doi: 10.1038/nature11112

21. Maity A, Das B. N6-methyladenosine modification in mRNA: machinery, function and implications for health and diseases. FEBS J. (2016) 9:1607–30. doi: 10.1111/febs.13614

22. Edupuganti RR, Geiger S, Lindeboom RGH, Shi H, Hsu PJ, Lu Z, et al. N(6)-methyladenosine (m6A) recruits and repels proteins to regulate mRNA homeostasis. Nat Struct Mol Biol. (2017) 10:870–8. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.3462

23. Saletore Y, Meyer K, Korlach J, Vilfan ID, Jaffrey S, Mason CE. The birth of the Epitranscriptome: deciphering the function of RNA modifications. Genome Biol. (2012) 10:175. doi: 10.1186/gb-2012-13-10-175

24. Zhang M, Zhang Y, Ma J, Guo F, Cao Q, Zhang Y, et al. The demethylase activity of FTO (fat mass and obesity associated protein) is required for preadipocyte differentiation. PLoS ONE. (2015) 7:e0133788 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0133788

25. Zhao X, Yang Y, Sun BF, Shi Y, Yang X, Xiao W, et al. FTO-dependent demethylation of N6-methyladenosine regulates mRNA splicing and is required for adipogenesis. Cell Res. (2014) 12:1403–19. doi: 10.1038/cr.2014.151

26. Wang X, Sun B, Jiang Q, Wu R, Cai M, Yao Y, et al. mRNA m(6)A plays opposite role in regulating UCP2 and PNPLA2 protein expression in adipocytes. Int J Obes. (2018) 11:1912–24. doi: 10.1038/s41366-018-0027-z

27. Lin Z, Tong MH. m(6)A mRNA modification regulates mammalian spermatogenesis. Biochim Biophys Acta Gene Regul Mech. (2019) 3:403–11. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2018.10.016

28. Furlan M, Galeota E, de Pretis S, Caselle M, Pelizzola M. m6A-dependent RNA dynamics in T cell differentiation. Genes. (2019) 10:E28. doi: 10.3390/genes10010028

29. Geula S, Moshitch-Moshkovitz S, Dominissini D, Mansour AA, Kol N, Salmon-Divon M, et al. Stem cells. m6A mRNA methylation facilitates resolution of naive pluripotency toward differentiation. Science. (2015) 6225:1002–6. doi: 10.1126/science.1261417

30. Ji P, Wang X, Xie N, Li Y. N6-methyladenosine in RNA and DNA: an epitranscriptomic and epigenetic player implicated in determination of stem cell fate. Stem Cells Int. (2018) 2018:3256524. doi: 10.1155/2018/3256524

31. Kudou K, Komatsu T, Nogami J, Maehara K, Harada A, Saeki H, et al. The requirement of Mettl3-promoted MyoD mRNA maintenance in proliferative myoblasts for skeletal muscle differentiation. Open Biol. (2017) 9:170119. doi: 10.1098/rsob.170119

32. Zhao BS, He C. Fate by RNA methylation: m6A steers stem cell pluripotency. Genome Biol. (2015) 16:43. doi: 10.1186/s13059-015-0609-1

33. Batista PJ, Molinie B, Wang J, Qu K, Zhang J, Li L, et al. m(6)A RNA modification controls cell fate transition in mammalian embryonic stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. (2014) 6:707–19. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2014.09.019

34. Frye M, Blanco S. Post-transcriptional modifications in development and stem cells. Development. (2016) 21:3871–81. doi: 10.1242/dev.136556

35. Chen T, Hao YJ, Zhang Y, Li MM, Wang M, Han W, et al. m(6)A RNA methylation is regulated by microRNAs and promotes reprogramming to pluripotency. Cell Stem Cell. (2015) 3:289–301. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2015.02.011

36. Wang S, Chai P, Jia R, Jia R. Novel insights on m(6)A RNA methylation in tumorigenesis: a double-edged sword. Mol Cancer. (2018) 1:101. doi: 10.1186/s12943-018-0847-4

37. Yu J, Li Y, Wang T, Zhong X. Modification of N6-methyladenosine RNA methylation on heat shock protein expression. PLoS ONE. (2018) 6:e0198604. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0198604

38. Chen J, Du B. Novel positioning from obesity to cancer: FTO, an m(6)A RNA demethylase, regulates tumour progression. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. (2019) 1:19–29. doi: 10.1007/s00432-018-2796-0

39. Li Z, Weng H, Su R, Weng X, Zuo Z, Li C, et al. FTO plays an oncogenic role in acute myeloid leukemia as a N(6)-methyladenosine RNA demethylase. Cancer Cell. (2017) 1:127–41. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2016.11.017

40. Li LJ, Fan YG, Leng RX, Pan HF, Ye DQ. Potential link between m(6)A modification and systemic lupus erythematosus. Mol Immunol. (2018) 93:55–63. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2017.11.009

41. Mo XB, Lei SF, Zhang YH, Zhang H. Detection of m(6)A-associated SNPs as potential functional variants for coronary artery disease. Epigenomics. (2018) 10:1279–87. doi: 10.2217/epi-2018-0007

42. Jia G, Fu Y, He C. Reversible RNA adenosine methylation in biological regulation. Trends Genet. (2013) 2:108–15. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2012.11.003

43. Meyer KD, Jaffrey SR. Rethinking m(6)A readers, writers, and erasers. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. (2017) 33:319–42. doi: 10.1146/annurev-cellbio-100616-060758

44. Balacco DL, Soller M. The m(6)A writer: rise of a machine for growing tasks. Biochemistry. (2019) 5:363–78. doi: 10.1021/acs.biochem.8b01166

45. Scholler E, Weichmann F, Treiber T, Ringle S, Treiber N, Flatley A, et al. Interactions, localization, and phosphorylation of the m(6)A generating METTL3-METTL14-WTAP complex. RNA. (2018) 4:499–512. doi: 10.1261/rna.064063.117

46. Romano G, Veneziano D, Nigita G, Nana-Sinkam SP. RNA methylation in ncRNA: classes, detection, and molecular associations. Front Genet. (2018) 9:243. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2018.00243

47. Xie Q, Wu TP, Gimple RC, Li Z, Prager BC, Wu Q, et al. N(6)-methyladenine DNA modification in glioblastoma. Cell. (2018) 5:1228–43.e20. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.10.006

48. Vrtacnik P, Marc J, Ostanek B. Epigenetic mechanisms in bone. Clin Chem Lab Med. (2014) 5:589–608. doi: 10.1515/cclm-2013-0770

49. Huang T, Peng X, Li Z, Zhou Q, Huang S, Wang Y, et al. Epigenetics and bone diseases. Genet Res. (2018) 100:e6. doi: 10.1017/S0016672318000034

50. Shin Y, Ghate NB, Moon B, Park K, Lu W, An W. DNMT and HDAC inhibitors modulate MMP-9-dependent H3 N-terminal tail proteolysis and osteoclastogenesis. Epigenetics Chromatin. (2019) 1:25. doi: 10.1186/s13072-019-0270-0

51. Shen GS, Zhou HB, Zhang H, Chen B, Liu ZP, Yuan Y, et al. The GDF11-FTO-PPARgamma axis controls the shift of osteoporotic MSC fate to adipocyte and inhibits bone formation during osteoporosis. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis Dis. (2018) 12:3644–54. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2018.09.015

52. Mo XB, Zhang YH, Lei SF. Genome-wide identification of m(6)A-associated SNPs as potential functional variants for bone mineral density. Osteoporos Int. (2018) 9:2029–39. doi: 10.1007/s00198-018-4573-y

53. Wu Y, Xie L, Wang M, Xiong Q, Guo Y, Liang Y, et al. Mettl3-mediated m(6)A RNA methylation regulates the fate of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells and osteoporosis. (2018) 1:4772. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-06898-4

54. Tian C, Huang Y, Li Q. Mettl3 regulates osteogenic differentiation and alternative splicing of vegfa in bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells. Int J Mol Sci. (2019) 3:E551. doi: 10.3390/ijms20030551

55. Yao Y, Bi Z, Wu R, Zhao Y, Liu Y, Liu Q, et al. METTL3 inhibits BMSC adipogenic differentiation by targeting the JAK1/STAT5/C/EBPbeta pathway via an m(6)A-YTHDF2-dependent manner. FASEB J. (2019) 6:7529–44. doi: 10.1096/fj.201802644R

56. Tran B, Nguyen ND, Center JR, Eisman JA, Nguyen TV. Association between fat-mass-and-obesity-associated (FTO) gene and hip fracture susceptibility. Clin Endocrinol. (2014) 2:210–7. doi: 10.1111/cen.12335

57. Guo Y, Liu H, Yang TL, Li SM, Li SK, Tian Q, et al. The fat mass and obesity associated gene, FTO, is also associated with osteoporosis phenotypes. PLoS ONE. (2011) 11:e27312. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0027312

58. Sachse G, Church C, Stewart M, Cater H, Teboul L, Cox RD, et al. FTO demethylase activity is essential for normal bone growth and bone mineralization in mice. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis Dis. (2018) 3:843–50. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2017.11.027

59. McMurray F, Demetriades M, Aik W, Merkestein M, Kramer H, Andrew DS, et al. Pharmacological inhibition of FTO. PLoS ONE. (2015) 4:e0121829. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0121829

60. Meyer KD, Saletore Y, Zumbo P, Elemento O, Mason CE, Jaffrey SR. Comprehensive analysis of mRNA methylation reveals enrichment in 3' UTRs and near stop codons. Cell. (2012) 7:1635–46. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.05.003

61. Feng X, McDonald JM. Disorders of bone remodeling. Annu Rev Pathol. (2011) 6:121–45. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pathol-011110-130203

62. Yang S, Duan X. Epigenetics, bone remodeling and osteoporosis. Curr Stem Cell Res Ther. (in press).

64. Caplan AI. Mesenchymal stem cells: time to change the name! Stem Cells Transl Med. (2017) 6:1445–51. doi: 10.1002/sctm.17-0051

65. Chen Q, Shou P. Fate decision of mesenchymal stem cells: adipocytes or osteoblasts? (2016) 23:1128–39. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2015.168

66. Both J, Wu T, Bras J, Schaap GR, Baas F, Hulsebos TJ. Identification of novel candidate oncogenes in chromosome region 17p11.2-p12 in human osteosarcoma. PLoS ONE. (2012) 1:e30907. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0030907

67. Yadav P, Subbarayalu P, Abdelfattah N, Eedunuri VK, Chen Y, Rao MK. Methyladenosine RNA demethylase ALKBH5 as a novel therapeutic target for osteosarcoma. Cancer Res. (2018) 13(Suppl.):4146. doi: 10.1158/1538-7445.AM2018-4146

68. Miao W, Chen J, Jia L, Ma J, Song D. The m6A methyltransferase METTL3 promotes osteosarcoma progression by regulating the m6A level of LEF1. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. (2019) 516:719–25. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2019.06.128

69. Zhang K, Wang M, Li Y, Li C, Tang S, Qu X, et al. The PERK-EIF2alpha-ATF4 signaling branch regulates osteoblast differentiation and proliferation by PTH. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. (2019) 4:E590–604. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00371.2018

70. Silva BC, Bilezikian JP. Parathyroid hormone: anabolic and catabolic actions on the skeleton. Curr Opin Pharmacol. (2015) 22:41–50. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2015.03.005

72. Gao X, Shin YH, Li M, Wang F, Tong Q, Zhang P. The fat mass and obesity associated gene FTO functions in the brain to regulate postnatal growth in mice. PLoS ONE. (2010) 11:e14005. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0014005

73. Jin M, Song S, Guo L, Jiang T, Lin ZY. Increased serum GDF11 concentration is associated with a high prevalence of osteoporosis in elderly native Chinese women. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. (2016) 11:1145–7. doi: 10.1111/1440-1681.12651

74. Lu Q, Tu ML, Li CJ, Zhang L, Jiang TJ, Liu T, et al. GDF11 inhibits bone formation by activating Smad2/3 in bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells. Calcif Tissue Int. (2016) 5:500–9. doi: 10.1007/s00223-016-0173-z

75. Liu W, Zhou L, Zhou C, Zhang S, Jing J, Xie L, et al. GDF11 decreases bone mass by stimulating osteoclastogenesis and inhibiting osteoblast differentiation. Nat Commun. (2016) 7:12794. doi: 10.1038/ncomms12794

76. Xu C, Wang J, Zhu T, Shen Y, Tang X, Fang L, et al. Cross-talking between PPAR and WNT signaling and its regulation in mesenchymal stem cell differentiation. Curr Stem Cell Res Ther. (2016) 3:247–54. doi: 10.2174/1574888X10666150723145707

77. Yuan Z, Li Q, Luo S, Liu Z, Luo D, Zhang B, et al. PPARγ and Wnt signaling in adipogenic and osteogenic differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells. Curr Stem Cell Res Ther. (2016) 3:216–25. doi: 10.2174/1574888X10666150519093429

78. Fawcett KA, Barroso I. The genetics of obesity: FTO leads the way. Trends Genet. (2010) 6:266–74. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2010.02.006

79. Scuteri A, Sanna S, Chen WM, Uda M, Albai G, Strait J, et al. Genome-wide association scan shows genetic variants in the FTO gene are associated with obesity-related traits. PLoS Genet. (2007) 7:e115. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0030115

80. Zhang Q, Riddle RC, Yang Q, Rosen CR, Guttridge DC, Dirckx N, et al. The RNA demethylase FTO is required for maintenance of bone mass and functions to protect osteoblasts from genotoxic damage. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. (2019) 36:17980–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1905489116

81. Warodomwichit D, Sritara C, Thakkinstian A, Chailurkit LO, Yamwong S, Ratanachaiwong W, et al. Causal inference of the effect of adiposity on bone mineral density in adults. Clin Endocrinol. (2013) 5:694–9. doi: 10.1111/cen.12061

82. Toth E, Ferenc V, Meszaros S, Csupor E, Horvath C. [Effects of body mass index on bone mineral density in men]. Orv Hetil. (2005) 28:1489–93.

83. Rosen CJ, Bouxsein ML. Mechanisms of disease: is osteoporosis the obesity of bone? Nat Clin Pract Rheumatol. (2006) 1:35–43. doi: 10.1038/ncprheum0070

84. Albala C, Yanez M, Devoto E, Sostin C, Zeballos L, Santos JL. Obesity as a protective factor for postmenopausal osteoporosis. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. (1996) 11:1027–32.

85. Zhao LJ, Liu YJ, Liu PY, Hamilton J, Recker RR, Deng HW. Relationship of obesity with osteoporosis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. (2007) 5:1640–6. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-0572

86. Choi YJ, Song I, Jin Y, Jin HS, Ji HM, Jeong SY, et al. Transcriptional profiling of human femoral mesenchymal stem cells in osteoporosis and its association with adipogenesis. Gene. (2017) 632:7–15. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2017.08.015

87. Gimble JM, Robinson CE, Wu X, Kelly KA. The function of adipocytes in the bone marrow stroma: an update. Bone. (1996) 5:421–8. doi: 10.1016/S8756-3282(96)00258-X

88. Zhao LJ, Guo YF, Xiong DH, Xiao P, Recker RR, Deng HW. Is a gene important for bone resorption a candidate for obesity? An association and linkage study on the RANK (receptor activator of nuclear factor-kappaB) gene in a large Caucasian sample. Hum Genet. (2006) 4:561–70. doi: 10.1007/s00439-006-0243-9

89. Zhao J, Bradfield JP, Li M, Zhang H, Mentch FD, Wang K, et al. BMD-associated variation at the Osterix locus is correlated with childhood obesity in females. Obesity. (2011) 6:1311–4. doi: 10.1038/oby.2010.324

90. Liu YZ, Pei YF, Liu JF, Yang F, Guo Y, Zhang L, et al. Powerful bivariate genome-wide association analyses suggest the SOX6 gene influencing both obesity and osteoporosis phenotypes in males. PLoS ONE. (2009) 8:e6827. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006827

91. Fischer J, Koch L, Emmerling C, Vierkotten J, Peters T, Bruning JC, et al. Inactivation of the Fto gene protects from obesity. Nature. (2009) 7240:894–8. doi: 10.1038/nature07848

92. Travison TG, Araujo AB, Esche GR, Beck TJ, McKinlay JB. Lean mass and not fat mass is associated with male proximal femur strength. J Bone Miner Res. (2008) 2:189–98. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.071016

93. Panoutsopoulou K, Metrustry S, Doherty SA, Laslett LL, Maciewicz RA, Hart DJ, et al. The effect of FTO variation on increased osteoarthritis risk is mediated through body mass index: a Mendelian randomisation study. Ann Rheum Dis. (2014) 12:2082–6. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-203772

Keywords: RNA N6-methyladenosine modification, m6A writers, m6A erasers, bone development, osteoporosis

Citation: Chen X, Hua W, Huang X, Chen Y, Zhang J and Li G (2020) Regulatory Role of RNA N6-Methyladenosine Modification in Bone Biology and Osteoporosis. Front. Endocrinol. 10:911. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2019.00911

Received: 09 September 2019; Accepted: 13 December 2019;

Published: 10 January 2020.

Edited by:

Marco Invernizzi, University of Eastern Piedmont, ItalyReviewed by:

Stefano Pagano, University of Perugia, ItalyAlessandro de Sire, University of Eastern Piedmont, Italy

Copyright © 2020 Chen, Hua, Huang, Chen, Zhang and Li. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Guowei Li, bGlnMjhAbWNtYXN0ZXIuY2E=

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Xuejiao Chen

Xuejiao Chen Wenfeng Hua

Wenfeng Hua Xin Huang

Xin Huang Yuming Chen3

Yuming Chen3 Junguo Zhang

Junguo Zhang Guowei Li

Guowei Li