- 1Department of Microbiology and Immunology, Tulane University School of Medicine, New Orleans, LA, United States

- 2Department of Pediatrics, Section of Nephrology, Tulane University School of Medicine, New Orleans, LA, United States

Obesity and the resultant metabolic complications have been associated with an increased risk of cancer. In addition to the systemic metabolic disturbances in obesity that are associated with cancer initiation and progression, the presence of adipose tissue in the tumor microenvironment (TME) contributes significantly to malignancy through direct cell-cell interaction or paracrine signaling. This chronic inflammatory state can be maintained by p53-associated mechanisms. Increased p53 levels that are observed in obesity exacerbate the release of inflammatory cytokines that fuel cancer initiation and progression. Dysregulated adipose tissue signaling from the TME can reprogram tumor cell metabolism. The links between p53, cellular metabolism and adipose tissue dysfunction and how they relate to cancer, will be presented in this review.

Introduction

Cancers associated with obesity are estimated to account for up to 40% of all cancers diagnosed in the US (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, CDC). Per CDC reports, the incidence of non-obesity related cancers showed a decline from 2005 to 2014, while the rates of obesity-related cancers increased (1). Causes of obesity and cancer are multifactorial with significant contribution from genetics and environmental factors. TP53 (p53) is the most commonly mutated gene in cancer with nearly half of all human cancers showing protein loss or mutation (2). Of the cancers that do not have mutations in the p53 gene locus, the majority exhibit mutations or altered levels of negative regulators of p53 (3, 4). Classically, p53 is known as a tumor suppressor, but recent work highlights the diverse functions of p53, including p53's contribution to metabolic and adipose tissue regulation. As increasing evidence links obesity to the onset of cancer, in this review, we discuss the crosstalk between adipose tissue and metabolism in cancer and the central role of p53 therein.

p53 Overview

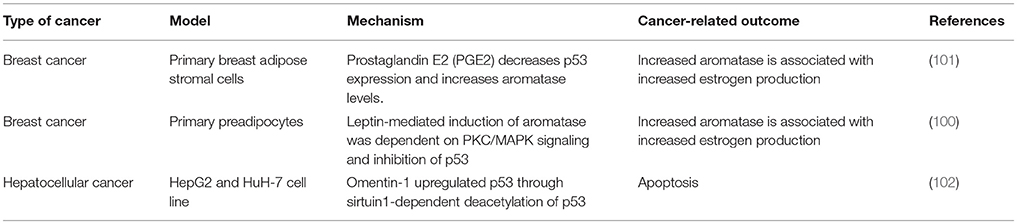

p53 is best known as a tumor suppressor that maintains genomic stability and inhibits cell proliferation pathways (5–11). Its significant role in tumor suppression is dependent on its activity as a transcription factor regulating expression of genes in cell cycle regulation, apoptosis, DNA repair, differentiation, and senescence pathways (Figure 1). Under conditions of mild stress, p53 initiates cell cycle arrest and DNA repair pathways. However, in response to catastrophic stress that inflicts irreparable damage, p53 triggers an apoptotic response designed to limit propagation of impaired cells.

Figure 1. Transcript ion-dependent and -independent p53 function. Different combinations of posttranslational modifications (red circles)—the PTM signature—will dictate the context-specific transcriptional response that will translate to a phenotypic outcome. The PTMs dictate interactions of proteins with p53, enabling stimuli-specific cellular output. Transcription-independent response involving mitochondria require mono-ubiquitination (blue circles) of p53. Localization of p53 at the mitochondrial membrane and interaction with anti-apoptotic Bcl proteins stimulates apoptosis. Translocation into the mitochondrial matrix requires interactions with proteins (denoted in green and yellow) where it interacts with mitochondrial proteins to preserve mitochondrial integrity. See text for details.

p53 protein levels are ubiquitously high in early embryogenesis in germ layer progenitors and embryonic stem cells until nearly mid-gestation (5, 12, 13), after which time expression is restricted to specific tissues during organogenesis as development progresses. Protein levels decrease postnatally to follow the recognized expression pattern of stabilization under cellular stress (5, 12, 14). Stimuli-induced post-translational modifications (PTM) stabilize the protein (15–21). In the absence of stress stimuli, negative regulation of p53 function is mediated by Mdm2 and Mdmx (22, 23). Different combinations of PTMs—the PTM signature—drive context-specific pathway activation. Protein stability and function are controlled by: (a) phosphorylation (b) acetylation (c) poly-ubiquitination (d) sumoylation (e) neddylation and (f) methylation (17, 21, 24–28). The N-terminus contains the transcription activation domain (TAD). In addition to stabilizing p53, the PTMs dictate the interactions of proteins with p53, enabling stimuli-specific cellular output. For example, p53 interacts with histone modifying enzymes and chromatin remodelers [e.g., HATs p300/CBP (29, 30), lysine-specific demethylase LSD1 (31)] which alter chromatin structure, along with interactions with proteins in the basal transcription machinery complex [TBP (32), and TBP-associated factors such as TFIIA and TAF1 (33, 34)] to regulate gene transcription (33, 35, 36). Transcription-dependent functions of p53 play a key role in cell-fate decisions by regulating expression of genes that control cell cycle arrest, DNA repair, apoptosis, senescence, and autophagy to limit the propagation of cells with damaged genomes (33–36).

Research in the last decade has revealed a critical role for p53 well beyond its role in tumor suppression. These roles include preserving stem cell health and differentiation in embryonic life, development of senescence and maintaining mitochondrial function in aging (5, 7, 37–41). Recent evidence strongly implicates p53 in the regulation of metabolism, linking p53 to metabolic abnormalities observed in aging, obesity, inflammation, and cancer (37, 42).

p53-Mediated Regulation of Intermediary Metabolism

Choice of metabolic pathway usage is determined by the cell's energy, biomass and metabolite demands. Many cancer cells depend on glycolysis, even under aerobic conditions (Warburg Effect) (43, 44). The shift to aerobic glycolysis is an active reprogramming event that enables anabolic growth. Intermediates from the glycolytic pathway serve as precursors for biomass synthesis that are necessary for proliferation. Additionally, the pentose phosphate pathway (PPP) produces precursors for the synthesis of nucleotides that are essential for DNA replication. In contrast, differentiated cells preferentially utilize mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) (45).

Consistent with its role as a tumor suppressor, p53 inhibits multiple steps of glycolysis and the PPP while promoting OXPHOS (46). Expression of glucose transporters Glut1 and Glut4 are downregulated by p53, resulting in the inhibition of glucose uptake. Induction of the phosphatase TP53-induced glycolysis and apoptosis regulator (TIGAR) decreases the production of fructose-2,6-bisphosphate (F2, 6BP) which allosterically activates phosphofructokinase 1 (PFK1) to increase glycolytic flux (9). By inhibiting expression of the negative regulator of the pyruvate dehydrogenase complex that is responsible for the transfer of cytosolic pyruvate to the mitochondria, p53 promotes OXPHOS by directing pyruvate to acetyl CoA rather than lactate (47). Increased lactate levels in the cell due to transcriptional repression of monocarboxylate transporter 1 (mct1) expression, a p53 target gene which transports lactate out of the cell, also decreases glycolytic flux (48).

p53 is a critical regulator of mitochondrial morphology, mitochondrial genomic integrity, mitophagy, aerobic metabolism and cellular redox state (38, 41, 49). In contrast to inhibitory effects on anabolic glycolysis, p53 drives catabolic mitochondrial respiration via induction of key genes such as mitochondrial glutaminase (Gls2), Synthesis of cytochrome c oxidase 2 (Sco2) and Complex 1 proteins that are involved in fueling the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle and driving electron transport (50, 51). p53 was demonstrated to adaptively regulate OXPHOS in Drosophila Myc+ cells and maintain their super-competitive status by enhancing the metabolic flux (52). In contrast to increased proliferation observed in cancer cells upon the loss of p53, the response of Drosophila Myc+ cells to p53 loss is impaired metabolism and reduced viability, suggesting a cell-context dependent regulation of cellular processes. By inducing expression of the mitochondria-eating protein (Mieap), p53 functions as a guardian of mitochondrial health, facilitating the removal of damaged mitochondria by mitophagy (53). Mitochondrial p53 physically interacts with TFAM, the factor that is responsible for mitochondrial DNA transcription, replication, and repair (11). Accordingly, decreased mitochondrial DNA content or mitochondrial DNA mutations are detected in fibroblasts from Li-Fraumeni patients (54).

p53 also plays a critical role in both normal and pathological lipid metabolism (55, 56). Generally, p53 is a negative regulator of lipid synthesis and activates fatty acid oxidation (FAO) via induction of expression of carnitine acetyltransferase genes (CPT1) that transport fatty acids to the mitochondria for oxidation. However, chronic p53 activation by nutrient stress (obesity) leads to hepatic steatosis, insulin resistance, and diabetes, pointing to the complexity of the homeostatic response (57–59). Dysregulated cell metabolism is an accepted hallmark of cancer and p53 can influence the function of many metabolic pathways (60). Obesity is also recognized as a state of dysregulated cell metabolism, and p53 is influential in adipose tissue differentiation, accumulation, and cytokine secretion.

Adipose Tissue

Adipose tissue is broadly subdivided into white and brown adipose tissue. The largest component of white adipose tissue is the large, spherical adipocyte with a unilocular lipid droplet occupying most of the cell volume. The primary role of white adipose tissue is to store energy in the form of triglycerides. When hormones signal the need for energy, fatty acids and glycerol are released through lipolysis. White adipose tissue is subdivided into unique depots highlighting the function and location of the adipose tissue. Visceral adipose tissue surrounds organs, subcutaneous adipose tissue forms a layer between the muscle and dermal fascia, and intramuscular adipose tissue protects tissue and supplies nourishment. Approximately 80% of human adipose tissue is deposited in subcutaneous depots. However, visceral adipose tissue is more metabolically active, and its accumulation is more prognostic of obesity-related mortality (61, 62). Both white adipose tissue depots store excess energy, but visceral fat also protects organs from physical trauma. White adipose tissue is capable of significant expansion that can lead to the accumulation of excess adipose tissue and thus increased propensity for obesity and related metabolic disorders (63).

In contrast to white adipose tissue, brown adipose tissue is specialized to burn sugars and lipids to generate heat and to help maintain body temperature through adaptive thermogenesis. Brown adipose tissue is abundant in neonates but undergoes rapid involution with age in humans. Consequently, adult human brown adipose tissue is relatively limited in mass and restricted to depots near the aorta and within the supraclavicular region of the neck (64). Brown adipose tissue is densely innervated by the sympathetic nervous system and is highly vascularized. Brown adipocytes contain multilocular lipid droplets and large numbers of mitochondria. The hallmark of brown adipose tissue function is the presence and activation of mitochondrial uncoupling protein 1 (UCP1) which uncouples OXPHOS from ATP synthesis in the inner mitochondrial membrane, thereby dissipating chemical energy as heat (65). A third adipose tissue type termed beige or “brown-in-white” (brite) adipose, has recently been characterized. Beige adipocytes can be induced by cold and a broad spectrum of pharmacological substances and, therefore, they are also known as “inducible brown adipocytes.” These depots can be induced to appear morphologically similar to brown adipose tissue, but appear in classical white adipose tissue depots and are derived from a non-classical brown adipose tissue lineage (66, 67).

Recently, the bone marrow has been identified as a unique adipose depot. Although the bone marrow contains few adipocytes at birth, the number increases with age, and by adulthood, bone marrow adipose tissue constitutes over 10% of the total fat mass in lean, healthy humans. There are two types of bone marrow adipose tissue classified as “regulated” that may influence hematopoiesis and “constitutive” that is important during early vertebrate development (68). The ontogeny of bone marrow adipose tissue is not well defined. Bone marrow adipose tissue differs in diet response, phenotype, gene expression and physiological actions from other adipose depots [reviewed in (69)]. For example, during conditions of starvation bone marrow adipose tissue volume increases whereas white adipose tissue volume decreases.

It is now clear that all adipose tissue acts in an autocrine/paracrine and endocrine manner. Adipocytes secrete an array of signaling molecules such as leptin, adiponectin, plasminogen activator inhibitor (PAI-1), vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), and interleukin (IL)-6, collectively referred to as adipokines, that communicate with other organs such as the brain, liver, muscle, the immune system, and adipose tissue itself. An example is metabolic symbiosis that occurs between tumor cells and adjacent adipose tissue during cancer progression. Adipokines and lipids are released from mature adipocytes and taken up by cancer cells. Paracrine factors from adipose tissue-derived stromal and immune cells that have infiltrated tumors, are secreted into the tumor microenvironment (70).

Differentiation of preadipocytes to mature adipocytes requires transcription regulators such as the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPARγ) and members of the CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein family (C/EBPs) (71). p53 is a negative regulator of PPARγ expression, and concomitantly of white adipocyte differentiation both in vivo and in vitro (72). p53 inhibits an adipogenic program in 3T3-L1 preadipocytes and mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) (73, 74). Knockdown of p53 by specific shRNA enhances the adipogenic capacity in both mouse and human cell lines, indicated by increased levels of adipogenic markers such as PPARγ, AP2, and adiponectin even without hormonal induction (74). Moreover, differentiation of p53-null MEFs into adipocytes is more robust compared to wild-type cells in an adipogenic medium (73–75). Accordingly, transgenic mice overexpressing active p53 demonstrate decreased adipose tissue deposition and reduction in body mass (76). However, p53 is a positive regulator of brown adipocyte differentiation (75). Also, using a murine model of diet-induced obesity (DIO) weight gain was reduced in p53-null mice, and the mechanism was through an increase in UCP1 expression, both in brown and white adipose tissue (77).

Adipose Tissue Dysfunction—Promoted by p53?

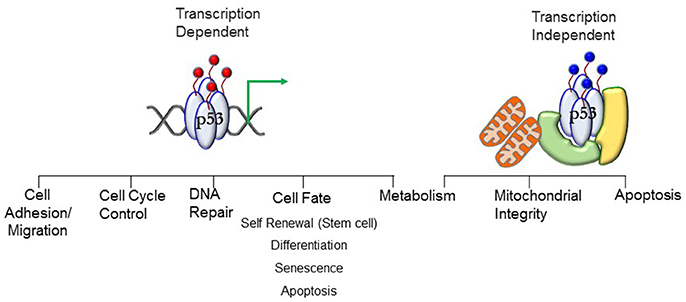

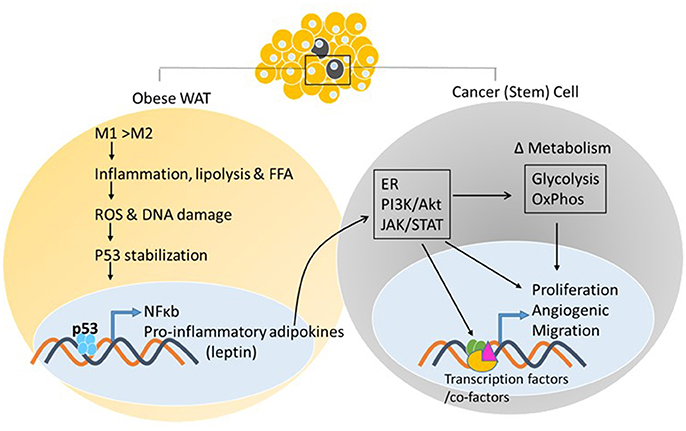

As adipose tissue expands, adipogenesis is upregulated, mature adipocytes enlarge, and angiogenic processes promote neovascularization. In obese states, enlarged adipocytes experience hypoxic conditions due to larger distances from the vasculature (78), as cardiac output and total blood flow do not increase with increased obesity (79). In association with these changes, the adipose tissue starts to produce chemotactic factors, such as monocyte chemoattractant protein (MCP)-1, that attract monocytes/macrophages into adipose tissue (80). Murine studies have demonstrated that excess adiposity increases the proportion of proinflammatory M1 to anti-inflammatory M2 macrophages in white adipose tissue (81). As the adipose tissue becomes inflamed, production of inflammatory cytokines increases and production of adiponectin decreases, resulting in the inability to store surplus free fatty acids (FFAs) leading to further adipose tissue dysfunction (82). In vitro and in vivo studies by Shimizu et al. indicated that increased release of FFAs led to ROS-induced DNA damage and upregulation of p53 in adipose tissue (59) (Figure 2). Activation of p53 upregulated the expression of proinflammatory adipokines via the NF-κB signaling pathway, and promoted adipose tissue inflammation, insulin resistance, and diabetes, whereas inhibiting p53 activity attenuated the inflammation (59). These changes in p53 expression related to obesity have been observed in both murine models and obese human subjects (55, 58, 83–86). The chronic inflammation associated with dysfunctional adipose tissue is thought to contribute to a favorable microenvironment for tumor growth and progression (Figures 2, 3).

Figure 2. White adipose tissue and cancer. Excess adiposity increases the proportion of proinflammatory M1 to anti-inflammatory M2 macrophages in white adipose tissue, resulting in production of inflammatory cytokines and stabilization of p53, further increasing adipokine transcription via p53/NF-κb activation. Adipokine release from the white adipose tissue and action on the neighboring tumor cell, or cancer stem cell, activates oncogenic signaling pathways that can impact energy metabolism pathways and transcriptional output via post-translational modifications of enzymes, transcription factors/co-factors, respectively, facilitating tumor initiation/promotion.

Figure 3. Yin and Yang of p53. (A) The p53/white adipose tissue/Cancer nexus. (B) The adipose tissue microenvironment contributes significantly to malignancy through tumor microenvironment communication. Regardless of the p53 status of the tumor cell, stimulation of oncogenic signaling pathways by p53-dependent adipokine production from the white adipose tissue in the microenvironment may facilitate tumor propagation.

In addition to data indicating p53 stimulation in dysfunctional adipose tissue exacerbates the pathology of adiposity, recent studies implicate p53 as a primary mediator of adiposity. As demonstrated by Kung et al. mice harboring the proline-to-arginine 72 (P72R) variant of p53 developed more severe obesity and glucose intolerance on a high-fat diet than mice with proline 72 variant (87). Further evidence supporting the adverse effect of high p53 activity in promoting obesity was demonstrated in mutant MDM2C305F mice that have impaired p53 regulation of lipid metabolism (88). The mutation disrupts ribosomal protein-MDM2 interaction that serves to sequester MDM2 and allow p53 activation. Also, pharmacological inhibition of p53 was demonstrated to prevent high-fat diet-induced weight gain observed in control mice (89). In summary, the data suggest that high p53 levels, whether induced in response to or as an inducer of adiposity, are likely counter-productive in maintaining adipose tissue homeostasis.

p53, Adipose Tissue, and Metabolism—an Unexplored Link in Cancer

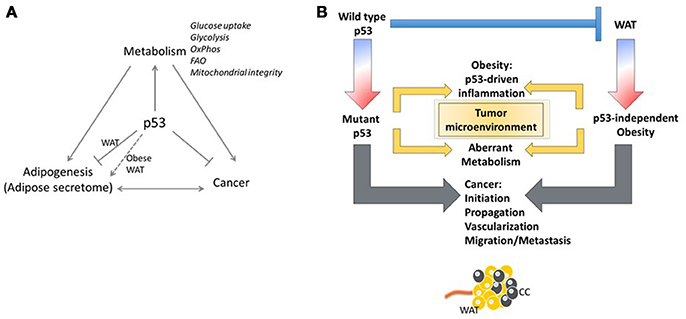

Secretion of adipokines (leptin, adiponectin, endotrophin, etc.) and growth factors from AT promote tumor growth. There are more than 600 different adipokines currently identified and many cancers, such as breast cancer, have adipokine receptors present on the cancer cells (90, 91). Adipokine-linked cancer progression may occur through increased proliferation, migration, inflammation and anti-apoptotic mechanisms. Leptin secretion from adipose tissue near tumors is increased, but not in adipose depots that are distant from the tumors (92). Interestingly, leptin is a known regulator of p53 expression (93). Leptin binding to its receptor enhances the proliferation and growth of breast cancer cells through numerous signaling pathways including estrogen receptor, JAK/STAT3, and PI3K/Akt pathways (94–96) (Figure 2). Aberrant signaling through these pathways activates expression of genes that contribute to cancer cell survival, proliferation, and migration (97–99). Moreover, signaling pathway activation can reprogram cellular metabolism to support the specific metabolite demands of proliferating cells. Thus, ectopic activation of these pathways promotes tumor progression (Figure 2). Leptin was also shown to induce aromatase and this correlated positively with BMI, leading to increased risk for breast cancer (100) (Table 1). Given the participation of p53 in adipose tissue inflammation (as discussed above in section Adipose Tissue Dysfunction—Promoted by p53?) that promote proliferative pathways vs. the known involvement of p53 as a tumor suppressor restricting proliferation and cell growth, the role of p53 in adipose tissue-driven tumorigenesis remains to be elaborated.

Wild-type p53 in an inactivated or dysfunctional form accumulates in the cytoplasm whereas stable p53 binds to target genes in the nucleus. Expression of the p53 transcript, nuclear localization of the protein and phosphorylation at Ser15 was decreased in ASCs due to the effect of prostaglandins (PGE2) (101). Wang et al. showed that the decrease in p53 protein expression and activity is through an inhibitory effect of PGE2 on AMP-activated kinase (AMPK). AMPK can no longer phosphorylate p53 at Ser15 (103, 104), resulting in decreased nuclear localization and transcriptional activity of p53. In clinical samples of breast cancer, tumor-associated ASCs had reduced nuclear p53 staining and increased perinuclear staining compared to normal ASCs (101). This is important as increased PGE2 is linked with many cancers and PGE2 associated inflammation is specifically associated with obesity and breast cancer (105). PGE2 and TNFα may contribute to the Warburg effect due to stimulation of GLUT1 and GLUT3 in ASCs (106). Again, this mechanism is through adipose-derived inflammation altering the metabolic microenvironment resulting in reduced p53 nuclear localization. A mechanism to the observed obesity-associated increase in aromatase and its link to breast cancer has been suggested (100). Adipose or ASC leptin secretion resulted in activation of PKC/MAPK signaling pathways and inhibition of p53. Furthermore, HIF1α and PKM2 were stabilized, resulting in increased expression of aromatase, and an increased risk of estrogen-dependent breast cancer. Conversely, p53 related mechanisms have been shown to promote hepatocellular carcinoma cell apoptosis. Omentin-1, an adipokine, was added to hepatocellular carcinoma cells and resulted in an inhibition of proliferation and an induction of apoptosis (102). It was shown that omentin-1 upregulated p53 through sirtuin1-dependent deacetylation of p53. This is in contrast to the actions of most reports on adipokines and cancer, which show promotion of metastatic potential and cancer cell survival.

Obesity has long been linked to increased local inflammation. As discussed above, obesity also reprograms metabolism systemically and can lead to increased levels of glucose and dyslipidemia in the blood (107). Although these examples are associated with obesity, the distribution of adipose tissue results in proximate or direct contact of tumors with adipose tissue, both in obese and non-obese conditions. This growing field of study suggests that the adipose tissue microenvironment contributes significantly to malignancy through tumor-microenvironment communication (Figure 3). In an invasive ductal carcinoma breast cancer model, increased lymph node metastasis was reportedly linked to adipose tissue invasion at the tumor margin (108). Tumor cells have been reported to induce delipidation of adipocytes and promote lipolysis in the tumor microenvironment (109). Regardless of the p53 status of the tumor cell, stimulation of oncogenic signaling pathways by p53-dependent adipokine production from the white adipose tissue in the microenvironment may facilitate tumor propagation (Figure 3).

Finally, bone marrow adipose tissue (BMAT) has recently been shown to affect metastatic progression and drug resistance in prostate and breast cancer. The mechanisms involved in this new adipose depot are currently being resolved. Fairfield et al. used a 3D culture model of BMAT to show that BMAT adipocytes, when co-cultured with tumor cells, undergo delipidation (110). This supports the model of exogenous lipid dependency by tumor cells for metabolic flexibility within the metastatic niche. Lipids from adipocytes in the tumor microenvironment could potentially regulate metabolic and signaling pathways in cancer cells, providing them with a survival advantage. A role for p53 in bone marrow adipose tissue has not yet been investigated.

Conclusions and Future Directions

An increased risk of cancer development and a poorer cancer prognosis is associated with increased obesity (107, 111–114). Cancer survivors with a higher body mass index are more likely to experience a cancer recurrence (115). The mechanisms linking increased adiposity to malignancy are not entirely understood. Altered interactions between adipose tissue and systemic or neighboring tissue, changing endocrine hormone and adipokine secretion that would facilitate tumor invasion and metastasis are hypothesized to drive metabolic reprogramming in tumor cells and provide metabolites and lipids required for tumor progression and growth. Although brown adipose tissue is metabolically more active than white adipose tissue, the link between chronic metabolic diseases and brown adipose tissue is unknown. Given the differential regulation by p53 of white vs. brown adipose tissue, it will be interesting to compare the influence of these different adipose depots for their potential to contribute to cancer. A thorough understanding of the crosstalk between cancer cells and the adipose microenvironment may well reveal novel therapeutic targets for cancer treatment.

Author Contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct and intellectual contribution to the work, and approved it for publication.

Funding

Funded in part by grants from the Louisiana Board of Regents (LEQSF(2018-20)-RD-A-20 to ZS) and the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases of the National Institute of Health (R56DK104779 to ZS).

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

1. Cancers Associated with Overweight and Obesity Make up 40 Percent of Cancers Diagnosed in the United States (2017). Available online at: https://www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2017/p1003-vs-cancer-obesity.html

2. Olivier M, Hollstein M, Hainaut P. TP53 mutations in human cancers: origins, consequences, and clinical use. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. (2010) 2:a001008. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a001008

4. Zhang Y, Lu H. Signaling to p53: ribosomal proteins find their way. Cancer Cell (2009) 16:369–77. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.09.024

5. Molchadsky A, Rivlin N, Brosh R, Rotter V, Sarig R. p53 is balancing development, differentiation and de-differentiation to assure cancer prevention. Carcinogenesis (2010) 31:1501–8. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgq101

6. Bondar T, Medzhitov R. p53-mediated hematopoietic stem and progenitor cell competition. Cell Stem Cell 6:309–22. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2010.03.002

7. Cicalese A, Bonizzi G, Pasi CE, Faretta M, Ronzoni S, Giulini B, et al. The tumor suppressor p53 regulates polarity of self-renewing divisions in mammary stem cells. Cell (2009) 138:1083–95. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.06.048

8. Balaburski GM, Hontz RD, Murphy ME. p53 and ARF: unexpected players in autophagy. Trends Cell Biol. (2010) 20:363–9. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2010.02.007

9. Bensaad K, Tsuruta A, Selak MA, Vidal MNC, Nakano K, Bartrons R, et al. TIGAR, a p53-inducible regulator of glycolysis and apoptosis. Cell (2006) 126:107–20. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.05.036

10. Donehower LA. The p53-deficient mouse: a model for basic and applied cancer studies. Semin Cancer Biol. (1996) 7:269–78.

11. Park JY, Wang PY, Matsumoto T, Sung HJ, Ma W, Choi JW, et al. p53 improves aerobic exercise capacity and augments skeletal muscle mitochondrial DNA content. Circ Res. (2009) 105:705–12, 711 p following 712. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.205310

12. Schmid P, Lorenz A, Hameister H, Montenarh M. Expression of p53 during mouse embryogenesis. Development (1991) 113:857–65.

13. Komarova EA, Chernov MV, Franks R, Wang K, Armin G, Zelnick CR, et al. Transgenic mice with p53-responsive lacZ: p53 activity varies dramatically during normal development and determines radiation and drug sensitivity in vivo. EMBO J. (1997) 16:1391–400. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.6.1391

14. Gottlieb E, Haffner R, King A, Asher G, Gruss P, Lonai P, et al. Transgenic mouse model for studying the transcriptional activity of the p53 protein: age- and tissue-dependent changes in radiation-induced activation during embryogenesis. EMBO J. (1997) 16:1381–90.

15. Loughery J, D. M. Switching on p53: an essential role for protein phosphorylation? BioDiscovery (2013) 8:1–20.

16. Giaccia AJ, Kastan MB. The complexity of p53 modulation: emerging patterns from divergent signals. Genes Dev. (1998) 12:2973–83.

17. Dai C, Gu W. p53 post-translational modification: deregulated in tumorigenesis. Trends Mol Med. (2010) 16:528–36. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2010.09.002

18. Kruse J-P, Gu W. SnapShot: p53 posttranslational modifications. Cell (2008) 133:930–930.e931. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.05.020

19. Kruse J-P, Gu W. Modes of p53 regulation. Cell (2009) 137:609–22. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.04.050

20. Vousden KH, Prives C. Blinded by the light: the growing complexity of p53. Cell (2009) 137:413–31. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.04.037

21. Meek DW, Anderson CW. Posttranslational modification of p53: cooperative integrators of function. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. (2009) 1:a000950. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a000950

22. Huang L, Yan Z, Liao X, Li Y, Yang J, Wang Z-G, et al. The p53 inhibitors MDM2/MDMX complex is required for control of p53 activity in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. (2011) 108:12001–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1102309108

23. Wang X, Jiang X. Mdm2 and MdmX partner to regulate p53. FEBS Lett. (2012) 586:1390–6. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2012.02.049

24. Knights CD, Catania J, Giovanni SD, Muratoglu S, Perez R, Swartzbeck A, et al. Distinct p53 acetylation cassettes differentially influence gene-expression patterns and cell fate. J Cell Biol. (2006) 173:533–44. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200512059

25. Ivanov GS, Ivanova T, Kurash J, Ivanov A, Chuikov S, Gizatullin F, et al. Methylation-acetylation interplay activates p53 in response to DNA damage. Mol Cell Biol. (2007) 27:6756–69. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00460-07

26. An W, Kim J, Roeder RG. Ordered cooperative functions of PRMT1, p300, and CARM1 in transcriptional activation by p53. Cell (2004) 117:735–48. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.05.009

27. Jansson M, Durant ST, Cho E-C, Sheahan S, Edelmann M, Kessler B, et al. Arginine methylation regulates the p53 response. Nat Cell Biol. (2008) 10:1431–9. doi: 10.1038/ncb1802

28. Schmidt D, Müller S. Members of the PIAS family act as SUMO ligases for c-Jun and p53 and repress p53 activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. (2002) 99:2872–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.052559499

29. Lill NL, Grossman SR, Ginsberg D, DeCaprio J, Livingston DM. Binding and modulation of p53 by p300/CBP coactivators. Nature (1997) 387:823.

30. Barlev NA, Liu L, Chehab NH, Mansfield K, Harris KG, Halazonetis TD, et al. Acetylation of p53 activates transcription through recruitment of coactivators/histone acetyltransferases. Mol Cell (2001) 8:1243–54. doi: 10.1016/S1097-2765(01)00414-2

31. Tsai W-W, Nguyen TT, Shi Y, Barton MC. p53-targeted LSD1 functions in repression of chromatin structure and transcription in vivo. Mol Cell Biol. (2008) 28:5139–46. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00287-08

32. Seto E, Usheva A, Zambetti GP, Momand J, Horikoshi N, Weinmann R, et al. Wild-type p53 binds to the TATA-binding protein and represses transcription. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. (1992) 89:12028–32.

33. Xing J, Sheppard HM, Corneillie SI, Liu X. p53 stimulates TFIID-TFIIA-promoter complex assembly, and p53-T antigen complex inhibits TATA binding protein-TATA interaction. Mol Cell Biol. (2001) 21:3652–61. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.11.3652-3661.2001

34. Li AG, Piluso LG, Cai X, Gadd BJ, Ladurner AG, Liu X. An acetylation switch in p53 mediates Holo-TFIID recruitment. Mol Cell (2007) 28:408–21. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.09.006

35. Tang X, Milyavsky M, Shats I, Erez N, Goldfinger N, Rotter V. Activated p53 suppresses the histone methyltransferase EZH2 gene. Oncogene (2004) 23:5759–69. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207706

36. Beckerman R, Prives C. Transcriptional regulation by P53. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. (2010) 2:a000935. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a000935

37. Gottlieb E, Vousden KH. p53 regulation of metabolic pathways. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. (2010) 2:a001040. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a001040

38. Lebedeva MA, Eaton JS, Shadel GS. Loss of p53 causes mitochondrial DNA depletion and altered mitochondrial reactive oxygen species homeostasis. Biochim Biophys Acta (2009) 1787:328–34. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2009.01.004

39. Schoppy DW, Ruzankina Y, Brown EJ. Removing all obstacles. A critical role for p53 in promoting tissue renewal. Cell Cycle (2010) 9:1313–9. doi: 10.4161/cc.9.7.11194

40. Danilova N, Sakamoto KM, Lin S. p53 family in development. Mech Dev. (2008) 125:919–31. doi: 10.1016/j.mod.2008.09.003

41. Park J-H, Zhuang J, Li J, Hwang PM. p53 as guardian of the mitochondrial genome. FEBS Lett. (2016) 590:924–34. doi: 10.1002/1873-3468.12061

44. Liberti MV, Locasale JW. The Warburg effect: how does it benefit cancer cells? Trends Biochem Sci. (2016) 41:211–8. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2015.12.001

45. Vander Heiden MG, Cantley LC, Thompson CB. Understanding the Warburg effect: the metabolic requirements of cell proliferation. Science (2009) 324:1029–33. doi: 10.1126/science.1160809

46. Jiang P, Du W, Wang X, Mancuso A, Gao X, Wu M, et al. p53 regulates biosynthesis through direct inactivation of glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase. Nat Cell Biol. (2011) 13:310–6. doi: 10.1038/ncb2172

47. Maddocks ODK, Vousden KH. Metabolic regulation by p53. J Mol Med (Berl). (2011) 89:237–45. doi: 10.1007/s00109-011-0735-5

48. Boidot R, Vegran F, Meulle A, Le Breton A, Dessy C, Sonveaux P, et al. Regulation of monocarboxylate transporter MCT1 expression by p53 mediates inward and outward lactate fluxes in tumors. Cancer Res. (2012) 72:939–48. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-2474

49. Wang DB, Kinoshita C, Kinoshita Y, Morrison RS. p53 and mitochondrial function in neurons. Biochim Biophys Acta (2014) 1842:1186–97. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2013.12.015

50. Suzuki S, Tanaka T, Poyurovsky MV, Nagano H, Mayama T, Ohkubo S, et al. Phosphate-activated glutaminase (GLS2), a p53-inducible regulator of glutamine metabolism and reactive oxygen species. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. (2010) 107:7461–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1002459107

51. Hu W, Zhang C, Wu R, Sun Y, Levine A, Feng Z. Glutaminase 2, a novel p53 target gene regulating energy metabolism and antioxidant function. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. (2010) 107:7455–60. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1001006107

52. de la Cova C, Senoo-Matsuda N, Ziosi M, Wu DC, Bellosta P, Quinzii Catarina M, et al. Supercompetitor status of Drosophila Myc cells requires p53 as a fitness sensor to reprogram metabolism and promote viability. Cell Metab. (2014) 19:470–83. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2014.01.012

53. Kitamura N, Nakamura Y, Miyamoto Y, Miyamoto T, Kabu K, Yoshida M, et al. Mieap, a p53-inducible protein, controls mitochondrial quality by repairing or eliminating unhealthy mitochondria. PLoS ONE (2011) 6:e16060. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0016060

54. Gupta S, De S, Srivastava V, Hussain M, Kumari J, Muniyappa K, et al. RECQL4 and p53 potentiate the activity of polymerase γ and maintain the integrity of the human mitochondrial genome. Carcinogenesis (2013) 35:34–45. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgt315

55. Yahagi N, Shimano H, Matsuzaka T, Najima Y, Sekiya M, Nakagawa Y, et al. p53 activation in adipocytes of obese mice. J Biol Chem. (2003) 278:25395–400. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M302364200

56. Su X, Gi YJ, Chakravarti D, Chan IL, Zhang A, Xia X, et al. TAp63 is a master transcriptional regulator of lipid and glucose metabolism. Cell Metab. (2012) 16:511–25. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2012.09.006

57. Yahagi N, Shimano H, Matsuzaka T, Sekiya M, Najima Y, Okazaki S, et al. p53 involvement in the pathogenesis of fatty liver disease. J Biol Chem. (2004) 279:20571–5. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M400884200

58. Minamino T, Orimo M, Shimizu I, Kunieda T, Yokoyama M, Ito T, et al. A crucial role for adipose tissue p53 in the regulation of insulin resistance. Nat Med. (2009) 15:1082–7. doi: 10.1038/nm.2014

59. Shimizu I, Yoshida Y, Katsuno T, Tateno K, Okada S, Moriya J, et al. p53-induced adipose tissue inflammation is critically involved in the development of insulin resistance in heart failure. Cell Metab. (2012) 15:51–64. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2011.12.006

60. Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell (2011) 144:646–74. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013

61. Ibrahim MM. Subcutaneous and visceral adipose tissue: structural and functional differences. Obes Rev. (2010) 11:11–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2009.00623.x

62. Lee MJ, Wu Y, Fried SK. Adipose tissue heterogeneity: implication of depot differences in adipose tissue for obesity complications. Mol Aspects Med. (2013) 34:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.mam.2012.10.001

63. Tang QQ, Lane MD. Adipogenesis: from stem cell to adipocyte. Annu Rev Biochem. (2012) 81:715–36. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-052110-115718

64. Sacks H, Symonds ME. Anatomical locations of human brown adipose tissue: functional relevance and implications in obesity and type 2 diabetes. Diabetes (2013) 62:1783–90. doi: 10.2337/db12-1430

65. Fedorenko A, Lishko PV, Kirichok Y. Mechanism of fatty-acid-dependent UCP1 uncoupling in brown fat mitochondria. Cell (2012) 151:400–13. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.09.010

66. Wu J, Bostrom P, Sparks LM, Ye L, Choi JH, Giang AH, et al. Beige adipocytes are a distinct type of thermogenic fat cell in mouse and human. Cell (2012) 150:366–76. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.05.016

67. Seale P, Bjork B, Yang W, Kajimura S, Chin S, Kuang S, et al. PRDM16 controls a brown fat/skeletal muscle switch. Nature (2008) 454:961–7. doi: 10.1038/nature07182

68. Scheller EL, Doucette CR, Learman BS, Cawthorn WP, Khandaker S, Schell B, et al. Region-specific variation in the properties of skeletal adipocytes reveals regulated and constitutive marrow adipose tissues. Nat Commun. (2015) 6:7808. doi: 10.1038/ncomms8808

69. Bukowska J, Frazier T, Smith S, Brown T, Bender R, McCarthy M, et al. Bone marrow adipocyte developmental origin and biology. Curr Osteoporos Rep. (2018) 16:312–9. doi: 10.1007/s11914-018-0442-z

70. Lengyel E, Makowski L, DiGiovanni J, Kolonin MG. Cancer as a matter of fat: the crosstalk between adipose tissue and tumors. Trends Cancer (2018) 4:374–84. doi: 10.1016/j.trecan.2018.03.004

71. Farmer SR. Transcriptional control of adipocyte formation. Cell Metab. (2006) 4:263–73. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2006.07.001

72. Chu DT, Tao Y. Molecular connections of obesity and aging: a focus on adipose protein 53 and retinoblastoma protein. Biogerontology (2017) 18:321–32. doi: 10.1007/s10522-017-9698-4

73. Huang Q, Liu M, Du X, Zhang R, Xue Y, Zhang Y, et al. Role of p53 in preadipocyte differentiation. Cell Biol Int. (2014) 38:1384–93. doi: 10.1002/cbin.10334

74. Molchadsky A, Shats I, Goldfinger N, Pevsner-Fischer M, Olson M, Rinon A, et al. p53 plays a role in mesenchymal differentiation programs, in a cell fate dependent manner. PLoS ONE (2008) 3:e3707. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003707

75. Molchadsky A, Ezra O, Amendola PG, Krantz D, Kogan-Sakin I, Buganim Y, et al. p53 is required for brown adipogenic differentiation and has a protective role against diet-induced obesity. Cell Death Differ. (2013) 20:774–83. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2013.9

76. Tyner SD, Venkatachalam S, Choi J, Jones S, Ghebranious N, Igelmann H, et al. p53 mutant mice that display early aging-associated phenotypes. Nature (2002) 415:45–53. doi: 10.1038/415045a

77. Hallenborg P, Fjaere E, Liaset B, Petersen RK, Murano I, Sonne SB, et al. p53 regulates expression of uncoupling protein 1 through binding and repression of PPARgamma coactivator-1alpha. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. (2016) 310:E116–28. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00119.2015

78. Folkman J, Hahnfeldt P, Hlatky L. Cancer: looking outside the genome. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. (2000) 1:76–9. doi: 10.1038/35036100

79. Jansson PA, Larsson A, Lonnroth PN. Relationship between blood pressure, metabolic variables and blood flow in obese subjects with or without non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. Eur J Clin Invest (1998) 28:813–8.

80. Kanda H, Tateya S, Tamori Y, Kotani K, Hiasa K, Kitazawa R, et al. MCP-1 contributes to macrophage infiltration into adipose tissue, insulin resistance, and hepatic steatosis in obesity. J Clin Invest. (2006) 116:1494–505. doi: 10.1172/JCI26498

81. Lumeng CN, Bodzin JL, Saltiel AR. Obesity induces a phenotypic switch in adipose tissue macrophage polarization. J Clin Invest. (2007) 117:175–84. doi: 10.1172/JCI29881

82. Arita Y, Kihara S, Ouchi N, Takahashi M, Maeda K, Miyagawa J, et al. Paradoxical decrease of an adipose-specific protein, adiponectin, in obesity. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. (1999) 257:79–83.

83. Vergoni B, Cornejo PJ, Gilleron J, Djedaini M, Ceppo F, Jacquel A, et al. DNA damage and the activation of the p53 pathway mediate alterations in metabolic and secretory functions of adipocytes. Diabetes (2016) 65:3062–74. doi: 10.2337/db16-0014

84. Bogazzi F, Raggi F, Russo D, Bohlooly YM, Sardella C, Urbani C, et al. Growth hormone is necessary for the p53-mediated, obesity-induced insulin resistance in male C57BL/6J × CBA mice. Endocrinology (2013) 154:4226–36. doi: 10.1210/en.2013-1220

85. Homayounfar R, Jeddi-Tehrani M, Cheraghpour M, Ghorbani A, Zand H. Relationship of p53 accumulation in peripheral tissues of high-fat diet-induced obese rats with decrease in metabolic and oncogenic signaling of insulin. Gen Comp Endocrinol. (2015) 214:134–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ygcen.2014.06.029

86. Ortega FJ, Moreno-Navarrete JM, Mayas D, Serino M, Rodriguez-Hermosa JI, Ricart W, et al. Inflammation and insulin resistance exert dual effects on adipose tissue tumor protein 53 expression. Int J Obes (Lond). (2014) 38:737–45. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2013.163

87. Kung CP, Leu JI, Basu S, Khaku S, Anokye-Danso F, Liu Q, et al. The P72R polymorphism of p53 predisposes to obesity and metabolic dysfunction. Cell Rep. (2016) 14:2413–25. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.02.037

88. Liu S, Kim T-H, Franklin DA, Zhang Y. Protection against high-fat-diet-induced obesity in MDM2C305F mice due to reduced p53 activity and enhanced energy expenditure. Cell Rep. (2017) 18:1005–18. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.12.086

89. Derdak Z, Villegas KA, Harb R, Wu AM, Sousa A, Wands JR. Inhibition of p53 attenuates steatosis and liver injury in a mouse model of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. J Hepatol. (2013) 58:785–91. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2012.11.042

90. Lehr S, Hartwig S, Sell H. Adipokines: a treasure trove for the discovery of biomarkers for metabolic disorders. Proteomics Clin Appl. (2012) 6:91–101. doi: 10.1002/prca.201100052

91. Jarde T, Caldefie-Chezet F, Damez M, Mishellany F, Penault-Llorca F, Guillot J, et al. Leptin and leptin receptor involvement in cancer development: a study on human primary breast carcinoma. Oncol Rep. (2008) 19:905–11. doi: 10.3892/or.19.4.905

92. Gnerlich JL, Yao KA, Fitchev PS, Goldschmidt RA, Bond MC, Cornwell M, et al. Peritumoral expression of adipokines and fatty acids in breast cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. (2013) 20:S731–8. doi: 10.1245/s10434-013-3274-1

93. Toro AR, Maymó JL, Ibarbalz FM, Pérez AP, Maskin B, Faletti AG, et al. Leptin is an anti-apoptotic effector in placental cells involving p53 downregulation. PLoS ONE (2014) 9:e99187. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0099187

94. Perera CN, Spalding HS, Mohammed SI, Camarillo IG. Identification of proteins secreted from leptin stimulated MCF-7 breast cancer cells: a dual proteomic approach. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) (2008) 233:708–20. doi: 10.3181/0710-RM-281

95. Saxena NK, Vertino PM, Anania FA, Sharma D. Leptin-induced growth stimulation of breast cancer cells involves recruitment of histone acetyltransferases and mediator complex to CYCLIN D1 promoter via activation of Stat3. J Biol Chem. (2007) 282:13316–25. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M609798200

96. Yin N, Wang D, Zhang H, Yi X, Sun X, Shi B, et al. Molecular mechanisms involved in the growth stimulation of breast cancer cells by leptin. Cancer Res. (2004) 64:5870–5. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-0655

97. Nicholson KM, Anderson NG. The protein kinase B/Akt signalling pathway in human malignancy. Cell Signal. (2002) 14:381–95. doi: 10.1016/S0898-6568(01)00271-6

98. Thomas SJ, Snowden JA, Zeidler MP, Danson SJ. The role of JAK/STAT signalling in the pathogenesis, prognosis and treatment of solid tumours. Br J Cancer (2015) 113:365–71. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2015.233

99. Saha Roy S, Vadlamudi RK. Role of estrogen receptor signaling in breast cancer metastasis. Int J Breast Cancer (2012) 2012:654698. doi: 10.1155/2012/654698

100. Zahid H, Subbaramaiah K, Iyengar NM, Zhou XK, Chen IC, Bhardwaj P, et al. Leptin regulation of the p53-HIF1alpha/PKM2-aromatase axis in breast adipose stromal cells: a novel mechanism for the obesity-breast cancer link. Int J Obes (Lond). (2017) 42:711–20. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2017.273

101. Wang X, Docanto MM, Sasano H, Kathleen Cuningham Foundation Consortium for Research into Familial Breast C, Lo C, Simpson ER, Brown KA. Prostaglandin E2 inhibits p53 in human breast adipose stromal cells: a novel mechanism for the regulation of aromatase in obesity and breast cancer. Cancer Res. (2015) 75:645–55. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-14-2164

102. Zhang YY, Zhou LM. Omentin-1, a new adipokine, promotes apoptosis through regulating Sirt1-dependent p53 deacetylation in hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Eur J Pharmacol. (2013) 698:137–44. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2012.11.016

103. Jones RG, Plas DR, Kubek S, Buzzai M, Mu J, Xu Y, et al. AMP-activated protein kinase induces a p53-dependent metabolic checkpoint. Mol Cell (2005) 18:283–93. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.03.027

104. Assaily W, Rubinger DA, Wheaton K, Lin Y, Ma W, Xuan W, et al. ROS-mediated p53 induction of Lpin1 regulates fatty acid oxidation in response to nutritional stress. Mol Cell (2011) 44:491–501. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.08.038

105. Subbaramaiah K, Morris PG, Zhou XK, Morrow M, Du B, Giri D, et al. Increased levels of COX-2 and prostaglandin E2 contribute to elevated aromatase expression in inflamed breast tissue of obese women. Cancer Discov. (2012) 2:356–65. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-11-0241

106. Docanto MM, Ham S, Corbould A, Brown KA. Obesity-associated inflammatory cytokines and prostaglandin E2 stimulate glucose transporter mRNA expression and glucose uptake in primary human adipose stromal cells. J Interferon Cytokine Res. (2015) 35:600–5. doi: 10.1089/jir.2014.0194

107. Park J, Morley TS, Kim M, Clegg DJ, Scherer PE. Obesity and cancer–mechanisms underlying tumour progression and recurrence. Nat Rev Endocrinol. (2014) 10:455–65. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2014.94

108. Yamaguchi J, Ohtani H, Nakamura K, Shimokawa I, Kanematsu T. Prognostic impact of marginal adipose tissue invasion in ductal carcinoma of the breast. Am J Clin Pathol. (2008) 130:382–8. doi: 10.1309/MX6KKA1UNJ1YG8VN

109. Wang YY, Attané C, Milhas D, Dirat B, Dauvillier S, Guerard A, et al. Mammary adipocytes stimulate breast cancer invasion through metabolic remodeling of tumor cells. JCI Insight (2017) 2:e87489. doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.87489

110. Fairfield H, Falank C, Farrell M, Vary C, Boucher JM, Driscoll H, et al. Development of a 3D bone marrow adipose tissue model. Bone (2018). doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2018.01.023. [Epub ahead of print].

111. Jahangir E, De Schutter A, Lavie CJ. The relationship between obesity and coronary artery disease. Transl Res. (2014) 164:336–44. doi: 10.1016/j.trsl.2014.03.010

112. Ligibel JA, Alfano CM, Courneya KS, Demark-Wahnefried W, Burger RA, Chlebowski RT, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology position statement on obesity and cancer. J Clin Oncol. (2014) 32:3568–74. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.58.4680

113. Calle EE, Rodriguez C, Walker-Thurmond K, Thun MJ. Overweight, obesity, and mortality from cancer in a prospectively studied cohort of U.S. adults. N Engl J Med. (2003) 348:1625–38. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa021423

114. Kyrgiou M, Kalliala I, Markozannes G, Gunter MJ, Paraskevaidis E, Gabra H, et al. Adiposity and cancer at major anatomical sites: umbrella review of the literature. BMJ (2017) 356:j477. doi: 10.1136/bmj.j477

Keywords: p53, adipokines, obesity, cancer, white adipose tissue, metabolism

Citation: Zwezdaryk K, Sullivan D and Saifudeen Z (2018) The p53/Adipose-Tissue/Cancer Nexus. Front. Endocrinol. 9:457. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2018.00457

Received: 21 March 2018; Accepted: 24 July 2018;

Published: 14 August 2018.

Edited by:

Che-Pei Kung, School of Medicine, Washington University in St. Louis, United StatesReviewed by:

Eva Surmacz, Temple University, United StatesMichaela Ruth Reagan, Maine Medical Center Research Institute, United States

Copyright © 2018 Zwezdaryk, Sullivan and Saifudeen. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Kevin Zwezdaryk, a3p3ZXpkYXJAdHVsYW5lLmVkdQ==

Deborah Sullivan, ZHN1bGxpdmFAdHVsYW5lLmVkdQ==

Zubaida Saifudeen, enViaXNhaWZAdHVsYW5lLmVkdQ==

Kevin Zwezdaryk

Kevin Zwezdaryk Deborah Sullivan

Deborah Sullivan Zubaida Saifudeen

Zubaida Saifudeen