- Emerson College, Boston, MA, United States

Despite medical advancements, Black gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men (BMSM) are the group most disproportionately impacted by HIV in the United States. Recent figures estimate one in two Black MSM will be diagnosed with HIV in their lifetime. From 2011 to 2015, the Center for Disease Control ran Testing Makes Us Stronger, a health communication campaign designed to increase rates of HIV testing in the Black MSM community. Past studies document the campaign's visibility, but fail to explain the continuous rise of HIV transmissions within the Black MSM community. Previous research on Testing Makes Us Stronger analyzes exposure to the campaign, but fails to capture the experiences and opinions of its target audience. Using the Culture-Centered Approach, this study conducted 20 semi-structured phone interviews to unveil how culture and systemic inequities influence rates of HIV transmission in the Black MSM community. Thematic analysis found three key themes: (1) trans invisibility, (2) call for holistic approaches, and (3) importance of local organizations. Findings from the study suggest HIV campaigns would benefit from working in tandem with other organizations designed to combat systemic inequalities.

Introduction

As rates of HIV transmission in Black men who have sex with other men continues to rise, health communication campaigns are uniquely suited to raise awareness and prompt behavior change. A plethora of social marketing campaigns, including Testing Makes Us Stronger, have launched, yet, they have had minimal impact on decreasing the number of new HIV positive diagnoses. This study seeks to understand why. First, it will discuss the current literature surrounding HIV in the Black MSM community. Next, it offers an overview of the Culture-Centered Approach (CCA) as well as aspects of social marketing, noting their application to Testing Makes Us Stronger. In order to understand systemic inequities in HIV testing, the study sought the opinions and perceptions of 20 Black MSM working in HIV advocacy. Implications are discussed.

HIV in Black MSM

In the United States, there are more than 1.1 million people aged 13 and older living with Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV), including the estimated 162,500 people who are living with HIV, but have yet to be diagnosed (Center For Disease Control, 2019a). Rising awareness, increased rates of testing, and more effective treatments have decreased rates of HIV acquisition for most demographics except one: MSM (Singh et al., 2018). In 2017, gay, bisexual, and other MSM comprised only 2% of the domestic population, yet they represented 70% of all new HIV diagnoses (Center For Disease Control, 2019b).

Black or African-American (hereafter referred to as Black) MSM continue to be disproportionately impacted more than their White counterparts, revealing a health disparity. According to the (Center For Disease Control, 2018), health disparities are “preventable differences in the burden of disease, injury, violence, or opportunities to achieve optimal health that are experienced by socially disadvantaged populations” (p. 1). Additionally, health disparities frequently translate to stark differences in the incidence, prevalence, and mortality of a disease (CDC, 2018). Recent (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2019) outline the vast difference in HIV incidence rates for Black MSM compared to White MSM, noting Black MSM, especially between the ages of 13–34, were nearly twice as likely to contract HIV. Next, of the 38,739 new HIV diagnoses in 2017, 10,070, or 37 percent of the diagnoses were among Black MSM (CDC, 2019). Other reports and data continue to shed light on this health disparity. For example, in 2013, the National Minority AIDS Council (NMAC) found between 2006 and 2009, young Black MSM saw a 48 percent spike in new HIV diagnoses; additionally, 2011 marked the first time the number of Black MSM diagnosed with HIV surpassed rates of transmission for White men (National Minority AIDS Council (NMAC), 2013). Most alarming, according to a groundbreaking report released at the 2016 Conference on Retrovirus and Opportunistic Infections (CROI Press Release, 2016), if current HIV diagnoses rates persist, 50 percent, or 1 in 2 Black MSM will be diagnosed with HIV in their lifetime, compared to 1 in 4 Latino MSM and 1 in 11 White MSM.

Several hypotheses have been proposed to explain this sharp increase in rates of HIV transmission. It was once believed Black MSM engaged in more unprotected intercourse compared to other MSM, but multiple studies debunk this myth. Black gay MSM do not engage in higher rates of risky sexual behavior (Clerkin et al., 2010; George et al., 2012; Millett et al., 2012; Sullivan et al., 2015). Instead, research suggests racially homophilious sexual networks are a leading factor (Amirkhanian, 2014; Hernández-Romieu et al., 2015). Newcomb and Mustanski's study (2013) was one of the first to analyze sexual network impact on rates of HIV transmission. Using Hierarchical Linear Modeling, their study found Black MSM reported significantly less unprotected sexual encounters than other groups, but were the most racially homophilous group in terms of sexual partnerships (Newcomb and Mustanski, 2013). Their research indicates Black MSM maintain an impermeable sexual network, as Black MSM engage in sexual intercourse almost exclusively with other Black MSM. Although Black MSM do not engage in unprotected sex more frequently than other groups, their dense sexual networks do contain a higher rate of transmission. In turn, because of their condensed sexual network, when unprotected sex does occur, there is a greater likelihood of contracting HIV.

Even when sexual networks are considered, individual behavior, such as condom use, partner selection, and consumption of drugs and alcohol, still do not fully explain Black MSM's high HIV incidence rate (Millett et al., 2012; Sullivan et al., 2015). Disproportionate rates of HIV transmission are most likely also driven by a myriad of systemic inequities and social determinants of health1. For example, undiagnosed STIs, access to testing, lack of healthcare, socioeconomic status, low educational attainment, and incarceration exacerbate rates of HIV transmission (Harper et al., 2016). The Black community possesses a higher poverty rate than other racial groups, and this impacts virtually every aspect of HIV care (Gayles et al., 2016). The CDC (2019) notes socioeconomic issues associated with poverty-such as lack of access to high quality health care, housing, and HIV education directly and indirectly increases the risk of HIV transmission for Black MSM compared to White MSM. Socioeconomic disconnection, which occurs when an individual is neither enrolled in school or working, has been found to be significantly and positively associated with one becoming HIV positive; multiple studies indicate Black MSM are significantly more likely to be socioeconomically disconnected than their White counterparts (Mayer et al., 2014; Sullivan et al., 2015; Gayles et al., 2016). The lack of economic connection has proven to increase rates of HIV transmission in a myriad of ways. First, lack of economic opportunity or enrollment in school has been linked to both (1) increased substance use and (2) decreased social support, as one's job/school often provides a communication network (Zaller et al., 2017). Zaller et al. (2017) note many MSM use substances, including methamphetamine, alcohol, and cocaine to not only increase sexual pleasure during intercourse, but also as a coping mechanism to deal with the chronic stress of being economically disenfranchised. Additionally, substance use increases rates of condomless sex and spontaneous intercourse (Zaller et al., 2017). Second, the lack of economic opportunity impacts one's access to HIV related care. The cost of securing testing, purchasing important medications, and staying retained in care is directly linked to one's health insurance, which is often tied to employment (Maulsby et al., 2013). Lastly, limited economic and education opportunities, especially periods of homelessness, have been associated with riskier sexual practices. Individuals living in poverty are more likely to engage in survival sex, a transactional act where one engages in sexual intercourse in exchange for food, money, shelter, and other essentials (Kalichman et al., 2011). Next, geographic region is also an important factor to consider. People living with HIV in rural areas face larger barriers to accessing HIV care and medications as well as greater mortality than individuals who live in urban areas (Quinn et al., 2017). In some Black communities, especially in the rural Deep South, one's desire to get tested is simply not enough as access to a testing center is often hours away, highlighting the importance of consistent public transportation and/or the need for more testing locations (Johnson, 2017). Johnson's study unveils another critical layer related to this disparity; structural inequities are often compounded by cultural influences. For example, HIV related stigma is particularly salient in the Deep South, even within the medical community (Stringer et al., 2015). Of the 777 healthcare workers in the Deep South who were surveyed, 93% reported at least one stigmatizing attitude or negative belief toward HIV (Stringer et al., 2015). Analyzed together, these studies suggest not only is it difficult for one to even access a doctor, but, once they enter the physician's room, patients are also forced to combat stigma. Additionally, despite increased knowledge and awareness, religious based stigma in the Black community still influences all aspects of the HIV care continuum (HIV.gov, 2018), ranging from testing to viral suppression (Jeffries et al., 2015). The Black community has steadfast ties to religious doctrine as religion has been a critical factor in helping the community establish hope. The role of religion played an integral part in surviving slavery and enduring racial violence during the Civil Rights movement (Nelson et al., 2016). Unfortunately, these strong religious ties are often weaponized and messages of homophobia are launched at Black MSM, increasing stigma (Nelson et al., 2016). Goffman (1974) defined stigma as a “profoundly discreditable attribute of a person or group that devalues their position in society.” Moreover, many Black MSM are “triply cursed,” facing racism, homophobia, and HIV related stigma (Arnold et al., 2014). Understanding the systemic inequities as well as cultural and social factors that put Black MSM at higher risk for acquiring HIV is critical to mitigating the epidemic.

Culture Centered Approach to Health Communication

The culture-centered approach (CCA) contends structural inequalities are intertwined with communicative and health inequities (Dutta, 2018). Therefore, if one desires to mitigate a health disparity, they must first address systemic inequities. CCA contends communication exists at the intersection of culture, structure and agency (Dutta, 2008). First, according to Dutta (2018) culture “reflects the shared values, practices, and meanings that are negotiated in communities” (p. 241). Culture refers to how communities make meanings. For example, as mentioned above, religious based stigma is a cultural component impacting HIV testing in Black MSM. Second, structure refers to systems in place that increase or decrease resources, rules, and assumptions within a community (Dutta, 2018). Third, agency refers to the degree of which an individual and/or community can enact daily choices while interacting with structures. Dutta (2018) writes, “whereas agency is communicatively expressed, the process of communication draws upon cultural meanings, and is located in its relationship to structures” (p. 241). CCA cautious against top down health communication campaigns, instead, researchers are obligated to elicit community involvement and input. Through dialogue, knowledge is co-created in community spaces opposed to isolated in the Ivory Tower or board room. Moreover, Dutta (2018) argues CCA is more than formative research that can be used to guide message construction, proper use of CCA shifts decision-making possibilities to the hands of the community. CCA can, and should be used in every step of social marketing campaigns, from message construction to campaign evaluation and processing feedback. Under this framework, this study reached out to community members to (1) evaluate how a HIV social marketing campaign targeting Black MSM was implemented and (2) community perceptions of the campaign.

Health Communication and Social Marketing

Health communication campaigns are frequently employed to raise awareness and promote healthy behavior change (Boudewyns et al., 2018). Kreps (2015) notes the effectiveness of health communication campaigns is influenced by a myriad of factors including: audience perceptions of campaign's desired behavior, message design/strategy, and identifying the appropriate communication channels. According to Kreps (2015), tailored message strategies identify key individual and community factors that drive health-promotion materials. As health communication campaigns have become more popular, more attention has been given to the importance of audience analysis/segmentation and community involvement (Kreps, 2015). When health communication campaigns are specifically tailored, the target audience is more likely to perceive the information as personally relevant, and therefore, the campaign is more likely to be cognitively processed, and ultimately, will have a higher likelihood of changing behavior (Noar et al., 2010).

It is important to note the distinction between health marketing and health communication. According to the (Center For Disease Control, 2020), health marketing is a multidisciplinary area of public health that draws on marketing, communication, and public health practices to inform the public on health messages, health needs, and methods of promotion. Health communication campaigns are undoubtedly a lynchpin of health marketing, but the study of health communication can also be studied through an interpersonal, organizational, and/or pop culture lens etc. Health campaigns often utilize traditional marketing techniques to prompt individuals to adapt their behavior, colloquially known as social marketing (Ramirez et al., 2017). The use of social marketing in public health is widespread, tackling issues ranging from smoking to recycling (Farrelly et al., 2009). Farrelly et al. (2009) found the Truth anti-smoking campaign targeted toward sensation seeking teenagers averted half a million teens from smoking. Additionally, the promotion of condom use internationally, especially in Sub-Saharan African countries, is another example of a large scale social marketing success (Grier and Bryant, 2005). Effective social marketing is predicated on implementing the four Ps.

Marketing Mix

Drawing from the field of advertising, health based social marketing campaigns rely on the four Ps: product, price, place, and promotion (Grier and Bryant, 2005). Outlining the tenets of social marketing is critical to understanding the CDC's Testing Makes Us Stronger campaign.

Product

In traditional marketing, the goal is to yield a profit and sell a physical product; however, in social marketing, the goal is to develop and integrate marketing ideas that harness a social good (Lee and Kotler, 2016). Lee and Kotler (2016) identify two different types of products- (1) core product, or the benefits of a behavior and (2) actual product, the desired enacted behavior. For example, a campaign may desire to increase rates of HIV testing in the Black MSM community; in this instance, the actual product (2) would be the physical practice of one completing an HIV test whereas the (1) core product could be various benefits including: peace of mind, increased trust, and physical health. Next, it is important to note promotional materials (billboards, posters, pamphlets, advertisements) are not considered products, instead, they are classified as promotional resources that increase the likelihood of adopting the desired behavior (product).

Price

Price may refer to monetary costs, but it also includes any sacrifices (emotional, psychological, time) one has to make in order to enact a campaign's behavior (Lee and Kotler, 2016). A behavior's “price” should always be analyzed from the consumer's point of view, and typically, consumers only enact a desired behavior if the benefits outweigh the costs (Grier and Bryant, 2005). Proper audience segmentation and formative research is key to understanding the target community's perception of price (Rimal et al., 2009). For example, for some, the risk of being outed, HIV related stigma and other psychological factors may be more important price points than the monetary medical cost of one receiving a HIV screening.

Place

(Lee and Kotler, 2016) note place translates to action outlets, which requires the audience to not only understand where and when a behavior can be enacted, but also where resources and materials for the behavior are located. Grier and Bryant (2005) write, “place includes the actual physical location of outlets, operating hours, site attractiveness, and accessibility” (p. 323). Place does not refer to the placement of promotional materials. In the instance of Testing Makes Us Stronger, place refers to the physical locations where one could get tested (clinics, hospitals, community centers, etc).

Promotion

Often the most visible component, Grier and Bryant (2005) note promotion analyzes what increases the likelihood of the audience buying the product. Promotion refers to both (1) the type of messaging used (fear, guilt, shame, hope, etc.), and (2) where the messaging appears. The use of TV/radio advertisements, print media including pamphlets and billboards, t-shirts, special events, celebrity endorsements, and face-to-face influence are all examples of social marketing promotion (Grier and Bryant, 2005). An example of a social marketing campaign, Testing Makes Us Stronger, is analyzed in the forthcoming section.

Testing Makes Us Stronger

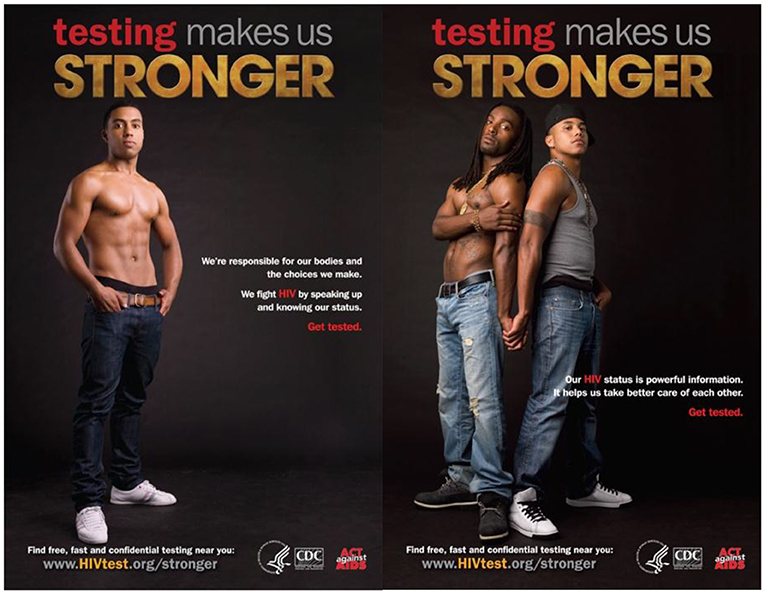

Social marketing campaigns designed to combat HIV via increased condom use and testing have significantly impacted behavior change (Habarta et al., 2017; Boudewyns et al., 2018). In April 2009, The White House and CDC launched Act Against AIDS, a multi-pronged health communication initiative designed to raise awareness of rising HIV rates. Under this program, in 2011, the CDC introduced Testing Makes Us Stronger (TMUS), a social marketing campaign that encourages HIV testing for Black MSM (Habarta et al., 2017). TMUS was launched in November 2011 and remained active until September 2015. Although national in scope, the campaign was heavily implemented in eight major cities: Atlanta, Baltimore, Chicago, Houston, New Orleans, New York, Oakland and Washington D.C. The campaign's goal was to increase HIV testing among Black MSM from ages 18–44 (Boudewyns et al., 2018). Formative research, also known as a needs assessment, was conducted, and multiple messages strategies were tested (Habarta et al., 2017; Boudewyns et al., 2018). However, there is a dearth research on who participated in these pre-tests, where the tests were held, and how they were conducted. At best, Boudewyns et al. (2018) write, “as campaign messages and concepts were developed, multiple rounds of pre-testing, including both quantitative and qualitative methods were conducted” (p. 866). Using insights from the pre-tests, the campaign relied on a strength/affirmation based approach and positive communal bonds. Campaign messages infused three different concepts: (1) Knowing your status helps us take care of each other, (2) We are standing up against HIV and stigma by getting tested and (3) We are responsible for our bodies and choices (Boudewyns et al., 2018). Promotional materials were designed to reach Black MSM through multiple channels; therefore, in addition to magazines and billboards, TMUS utilized multiple digital avenues, including targeted social media ads via Facebook and Twitter and a dedicated website (Habarta et al., 2017) (Figure 1). The national website provided information about HIV prevention, campaign goals, and a search tool for one to find testing sites based on their ZIP code (Habarta et al., 2017). Additionally, campaign presence was increased for community events such as national conferences, Gay Pride parades, and house/ball pageants (Habarta et al., 2017).

Figure 1. Sample TMUS campaign materials [Testing Makes Us Stronger Poster (Digital image), 2011].

To date, two quantitative TMUS evaluations have been conducted using survey data (Habarta et al., 2017; Boudewyns et al., 2018). Both studies found exposure to TMUS increased self-efficacy to get tested, increased intentions to get tested, and more positive behavioral beliefs toward HIV testing (Habarta et al., 2017; Boudewyns et al., 2018). However, the number of individuals living with HIV continues to rise. Clearly, these findings represent a disconnect between increased testing and a decrease in HIV acquisition amongst Black MSM. These studies do not explore the experiences and complexities related to HIV, instead, they classify HIV testing as a band-aid solution to a complex problem embedded in racism, homophobia, and socioeconomic disenfranchisement. I seek to fill the gap in literature by examining various opinions of TMUS, and how it could be improved. Through thematic analysis, I discuss how cultural components and structural inequities were not analyzed before launching the campaign. In other words, this study unpacks the structural inequalities that permeate through current HIV campaigns targeting Black MSM.

Research Questions

Utilizing the findings from the two previous quantitative studies, the following research question is proffered.

RQ1: How did Black MSM think about TMUS?

RQ2: What role did culture play in Black MSMs' perception of TMUS?

Methods

Gibbs (2018) explains qualitative research can be useful to not only understand how an individual experiences a phenomenon, but also how they “make sense” of the issue at hand. Kreps (2008) furthers, “qualitative inquiry can provide context and information rich data for increasing the validity of health communication research” (p. 8). Finally, qualitative research can be useful when identifying structures that limit health of marginalized groups (Olson et al., 2016). I contend the fight to transform systemic inequalities can only be addressed after (1) the structures have been identified and (2) we understand the community's perception of the phenomenon at hand. Qualitative research allows researchers to better understand culture, a key component of CCA. Similar to Dutta, I argue that culture is not a simple secondary factor when discussing HIV; culture plays a vital role in the rising rates of HIV transmission in the Black MSM community. Previous research on the culture-centered approach explains how culture plays an important role in how individuals view and interact with their healthcare (Dutta, 2008). Research supports the notion that qualitative research yields fruitful data related to HIV prevention (Arnold et al., 2014; Adams et al., 2018). Adams et al. (2018) conducted interviews to better understand barriers to testing for young Black MSM and transwomen; they found fear for violence to be a recurring theme. A study featuring interviews of 31 young Black MSM found that HIV-related stigma and homophobia, within the larger societal context of racism, were related to sexual risk behavior, reluctance to obtain HIV testing or care, lower adherence to treatment medication, and non-disclosure of a positive HIV status to sexual partners (Arnold et al., 2014). The aforementioned study found that interviewees reported HIV-related stigma at the hands of church and family members. Based on the promise of previous studies, this study followed a similar approach, utilizing phenomenological interviews.

Phenomenological Interviews

A phenomenological study “describes the common meaning for several individuals of their lived experiences of a concept or a phenomenon” (Creswell, 2007, p. 57). This approach allows respondents to discuss their perception of a phenomenon. In this study, the phenomenon of interest was Testing Makes Us Stronger, a health communication campaign targeting Black MSM. Next, because CCA is framing this study, I wanted to understand how culture influenced the community's perception of the campaign. Data collection in phenomenological studies frequently consists of in depth interviews (Creswell, 2007). Thus, this study depended on in depth interviews of Black MSM employed in community-based organizations involved in HIV advocacy.

Procedure

Recruitment

Approval for the study was obtained from a large institution on the east coast before data collection began. Data were collected over an 8 month period in 2016 to early 2017. To participate in the study, individuals had to self-identify as Black MSM, and be employed at a community based organization involved in HIV advocacy. Previous research surrounding the general Black MSM community's exposure toward TMUS has already been conducted, but there is a lack of in-depth research surrounding the opinions of individuals who are employed to deliver the services of TMUS. These men employed in community based organizations are (1) often the point of contact for the larger Black MSM community and (2) are often evaluated and funded based on their implementation of national initiatives; therefore, this study sought out their voices and perceptions of the campaign.

Respondents were recruited by snowball and purposeful sampling. First, a formal announcement was made at two conferences, the United States Conference on AIDS (USCA) and National African American MSM Leadership Conference (NAESM). Next, a solicitation message was posted on various social media pages, including the study's principal investigator. Third, respondents were recruited directly by using the contact e-mail located on organizations' web page. Finally, individuals completing the interview were asked to send information to colleagues and peers who qualify for the study. All respondents were provided with necessary IRB information. Since all interviews were conducted via telephone, respondents were given the option of providing (1) recorded verbal consent or (2) the ability to be e-mailed a physical consent form that could be signed; all respondents indicated verbal consent was preferable. Interviews only continued once verbal consent was acknowledged. As part of the consent process, respondents were informed that their quotes would be used in a study; all respondents acknowledged this and consented to quotes being used in publication. No compensation was given for participation.

Participants

After verbal consent was given, the study's author conducted semi-structured phone interviews. Twenty-one (21) semi structured phone interviews were conducted, but, due to recording issues, one interview was omitted. Twenty (20) recorded interviews were analyzed. The interviewer used a series of questions, and probed for further clarification when necessary. Sample questions include:

• How long have you been involved in HIV related work?

• Are you aware of Testing Makes Us Stronger Campaign?

• What are some of the campaigns strengths and weaknesses?

• Do you believe the campaign was successful? Why or why not?

• If you could draft your own campaign, what would it include and why?

All respondents identified as cisgender males. Age varied for the respondents, ranging from ages 22–57 years old. In addition, educational attainment ranged from high school diploma to terminal degree (Ph.D.). To ensure confidentiality, all interviews were conducted in a private library room located on a college campus. In order to ensure anonymity, names of individuals, job titles, and specific places of employment were omitted. Pseudonyms were given to each respondent. All of the interviews were recorded using the iPhone application, TapeACallPro. All interviews were transferred to a password protected flash drive within 24 h, and the flash drive is only accessible to the author as it is held in a locked office. All recordings were permanently deleted from the researcher's personal cell phone. All interviews were transcribed within 2 weeks of recording.

Thematic Analysis

According to Moustakas (1995) a researcher ought to read and listen to their transcripts multiple times to familiarize oneself with the data. After this step is complete, the lead researcher is responsible for identifying and extracting key phrases that highlight respondent experiences; these experiences are translated into codes or labels (Moustakas, 1995). Saldaña (2016) writes, “a code in qualitative inquiry is most often a word or short phrase that symbolically assigns a summative, salient, essence capturing attribute for a portion of language-based data” (p. 3). Following the work of Saldaña (2016), the study then coded for repeated patterns, until saturation was reached. Saturation occurs when no new information emerges from the coding and no new properties, dimensions, or actions are seen in the data (Saldaña, 2016). After reaching saturation, the researcher used the coded patterns to establish the most prevalent themes. Next, the researcher isolated key quotations that best illustrated the theme, and captured rich description of respondent experiences. Although the researcher was the sole coder, steps were taken to ensure validity of the data. Throughout the data collection process, the researcher consistently participated in member reflections, a collaborative process where one works with the respondents in the study to ensure transparency and data authenticity. Tracy (2010) writes, “member reflections” allow for sharing and dialoguing with participants, providing opportunities for questions, critique, feedback, affirmation, and even collaboration (p. 844). This study utilized member checks, a type of member reflection, that prompts researchers to take findings back to participants to verify the truth and accuracy of the researcher's interpretation (Tracy, 2010).

Findings

Thematic analysis yielded three key themes: (1) trans invisibility, (2) call for more holistic approaches, and (3) necessity of local organizations.

Trans Invisibility

First, despite the study intending to focus exclusively on Black MSM, several respondents indicated that their community based organization not only serves Black MSM, but transwomen as well.

Joshua, New Orleans

My organization primarily deals with Black gay men, but I see quite a few transwomen as well. (responding to probing question) My best guess is that they have nowhere else to go. It's really bad down here in the South. Homophobia is bad, but transphobia is worse. I want them to know that this will always be their safe space. So many of them are murdered….in cold blood (pause) So I want them to know….this isn't just a gay space. This is your place too.

This notion of the organization being a safe space for transwomen was reiterated by multiple respondents.

Robert, Indianapolis

I've seen more and more transwomen come through the doors. They are our sisters in the fight. And to be honest, transwomen are the most resilient people I know. The amount of shit they face….I can't imagine. The average life expectancy of a transwoman is something like 35 years old. Imagine that? Imagine thinking you're only going to live for 35 years. We should do more for them. We wouldn't be here if it weren't for them. They have, and will always be a part of this community. As long as I'm here, this door will always be open for transwomen.

Robert's comments highlight the communal aspect of the Black MSM and transcommunity, a component TMUS relied on. Yet, this finding highlights a disconnect between TMUS and Black MSM, its target population. One of the core components of TMUS was the importance of strong communal bonds, but these quotations support the notion that these bonds not only exist within Black MSM, but Black transwomen as well. Unfortunately, TMUS falsely conflated target population and community. Black MSM consider Black transwomen to be vital parts of their larger community, but TMUS failed to have a component aimed at Black transwomen. Similar to the rates of HIV in the Black MSM community, Black transwomen experience HIV transmission at a larger rate as well. Although only 14% of transgender women in the US are HIV positive, an estimated 44% of Black transgender women have HIV (Center For Disease Control, 2019b). Many of the respondents, like Robert, voiced frustration with these figures, imploring organizations and campaigns to “do more.” This idea of leaving transwomen behind and rendering them silent was pervasive in the data. Some argued that the local paradigm of community based organizations systematically silences the voices and needs of transgender women. Responses from the interviewees indicate they believe current HIV focused health communication campaigns fail to include Black transwoman, one of the queer communities most marginalized populations.

Miguel, Miami

So I know this interview is about a specific campaign, but I want to make something clear. We have it bad, but our trans sisters got it much worse. No matter how bad I think Testing Makes Us Stronger is….at least I saw someone who looked like me. Trans women are left out to dry, even by organizations dedicated to Black gay men. And I think that's so messed up. If they can't come here, where can they go?

Miguel's comments were reinforced by others, who pointed out that trans women have been largely ignored. Some even pointed out that their organization fails to hire Black transwomen, an example of systemic oppression in the form of limited economic opportunities.

Derek, San Francisco

In the same way a bullet has no name to it, HIV has no name to it. It can and does impact anyone. We lack the inclusion of transgender women on two fronts. One…transwomen of color, particularly Black and Latina need to be employed by these CBOS…mine included. No shade. I've tried to bring it up, but I'm always shot down. Two….women come in to my office all the time and I feel bad because I cannot answer their questions. I have noticed we don't include them, it is all about inclusion. Transgender women are individuals who have been left out. I think we need to include them and hear what they have to say. Build some awareness of their issues. It's not the same as my issues as a gay man.

George, Atlanta

We have to get people who don't necessarily identify as gay. Trans women are not gay men. There is a heavy loss when looking at the trans community. I think we need more focus on how we speak to trans women, more research. Those that don't identify as gay but seek out as same sex. There hasn't been any focus on trans women at all. Testing Makes Us Stronger did nothing to change it.

This analysis reveals that respondents believed there were larger issues at hand than a single campaign, instead, they contend we should be focused on uplifting the most disenfranchised individuals in the queer community. Second, it unveils various systemic barriers at play to transwomen receiving care related to HIV. This will be later explored in the discussion section. To this date, there has yet to be a HIV social marketing campaign targeting transwomen of color.

Holistic Approaches

One of the most prevalent, and perhaps, provocative findings was the call for programs to have a more holistic approach. Several respondents indicated that current national campaigns operate in a utopia, meaning they are predicated on the belief that awareness yields more testing and that testing leads to more care. However, one respondent, Daryl, stated, “this belief is offensive and shows how much they don't know. There is real trauma that can come with a positive diagnosis.” There were several calls to address the more systemic issues that exacerbate the epidemic ranging from an overhaul of sex education to addressing homelessness.

Travis, Little Rock

Speaking directly to the type of services received. In my opinion, and I know I am young but I am HIV positive so I know what it is like. Every single clinic needs holistic approaches. Food bank, therapists on site. Testing Makes Us Stronger wasn't bad, but it didn't address the larger issues. Poverty, education, jobs. We can't ignore these issues. If we forget about my mental health….what if I'm already depressed from being gay. Me testing positive could trigger a suicide attempt. What if I aint ate in two days……why the hell would I want you to poke into my arm, I don't wanna do that. If I'm worried about where Imma sleep or how Im gonna afford medicine….I don't care about getting tested. I am not gonna come to my appointment to get poked with needles. Or I can't think because I'm too depressed cause my family hates me and I don't have a job. Why would I worry about an appointment? The answer is I wouldn't. I wouldn't show up to the appointment.

Comments like Travis's allude to the power of systems, a tenet of CCA. Additionally, following CCA, the quotation above reveals how systems interact with one's agency. In the example articulated above, the lack of economic opportunity and dearth of mental health services are systemic barriers to one getting tested (agency).

Mike, New York City

I think organizations need to move away and I don't think organizations can do this alone. But we need to move away from the idea that testing is the end answer. Testing Makes Us Stronger assumes testing is the answer to decreasing HIV. Well….guess what sis? It's not!(laughter) We need HIV specific services to address issues we already know place someone at risk. Homelessness, survival sex, depression, access, so on so forth. That comes first, then we can talk about HIV. Sometimes I think people think that being Black and gay means HIV is the first thing on your mind, that isn't true. We have tons of other things to worry about. We are still people. Even with Testing Makes Us Stronger….ok so let's say I wanna get tested. Where do I go? How can I get there? Does it cost? These are things campaigns need to think about.

Again, similar to Travis, Mike explores cultural and systemic inequities that exacerbate the epidemic. In addition to this, Mike's comment is important as he explicitly states “testing is not the answer to decreasing HIV.” Additionally, Mike's comment explores the connection between place, where the desired action can take place and systemic barriers. Simply put, TMUS assumed the desire to get tested was the barrier, but this analysis suggests multiple systemic factors are at play. This notion of testing being the beginning, not the end, of combatting HIV is also echoed in the quotation below.

Scottie, Los Angeles

We are not going to test our way out of this epidemic (responding to probing question). Ummm. a lot of it will have to deal with addressing those very real structural social issues that Black gay men are experiencing. We don't even think about the fact that so many young Black gay men were never taught about HIV and condoms in school. Let alone gay hookups. They don't learn that. Often times national campaigns don't get to the heart of these issues. I look at HIV funding as a sandwich. The majority of the funding, the biggest piece, I guess the bread is in research and in service delivery. Treatment for folks that are positive and research to improve existing treatment regimens or create new ones. Almost nothing is dedicated to advocacy for public policy that can do some real help for the community. Sometimes, I wanna shake people and say testing is one part of the continuum. It's a piece of the pie, not the whole pie.

Darrius, Washington DC

Testing Makes Us Stronger is coo, but……. (pause) I really don't want to knock the campaign because it tried. It was one of the first times there was a campaign for us. But man…I don't know. (pause) Ok let me put it to you like this. I get tested. Bam, Im positive. Now what? What if I don't got insurance? That's what the campaign misses. I can be positive and never go back to a doctor. I can be positive and go to the doctor once. Get pills and take ‘em and think im coo. I can be positive and achieve viral suppression, and stop going. Not knowing that I gotta keep taking the meds. Man, I've had clients who stopped taking their medicine because they were undetectable. They go back to doctor and realize their T cells are low, low, low. Its level to it.

Scottie's comments, paired with the others, highlight a prominent problem with the goal of TMUS; all respondents indicated testing alone is not enough. Scottie mentioned to “the continuum,” which refers to the HIV care continuum. According to the (Center For Disease Control, 2019b), the HIV care continuum consists of five steps: (1) testing and diagnosis, (2) linkage to care, (3) retained in care, (4) prescribed antiretroviral therapy and (5) viral suppression-“undetectable.” The comments above argue that TMUS assumes the most important stage is diagnosis, but they refute that claim. According to the analysis, campaigns ought to address various aspects of the HIV care continuum. It is important to acknowledge the structural barriers which influence access to care.

Local Organizations

Lastly, respondents revealed the importance of local, community based organizations. Several individuals contended local organizations are more in touch with the needs of the community. Dutta (2018) would argue local organizations are more in tune with cultural norms, and therefore, better equipped to aid their communities. Local organizations are key players in the process of co-creating knowledge with their clients.

Chris, Atlanta

We received money from CDC for Testing Makes Us Stronger, and it got a bit tense. (responding to probing question) Because they would come down and say “why aren't rates going down?” Sounded very accusatory. Like we aren't doing enough or aren't trying. I had to tell them, look. You don't get it. They only get statistics, but we deal with people. I don't think statistics can gather everything. People come with stories and backgrounds. That matters. Only local organizations can really reach those who need it most. If a old white man walk in here asking to test folks, there aint no way my clients would trust him.

The idea of community based organizations being the lynchpin of HIV advocacy was reinforced by others as well.

Julian, Birmingham

(referring to TMUS) I wish they would have talked to local organizations more. They gave us some pamphlets and new testing training and left it at that. (responding to probing question) Of course we have to reach out to CBOS. Why? Because they are community based organizations. CDC….the CDC is like the parent if I may. They basically say we are going to extend some opportunities to you. These are the things that you can do and the resources we are going to give you to draw in these people. They give it to CBOS and CBOs are the heart. It is their job to hit the ground and get people. Let people know…come to my facility. Where people look like you. We got you. I've been in their shoes so if they are reluctant, I get it. I just stay patient.

In addition to the call for community-based organizations, several respondents indicated that these organizations need to employ more Black MSM, particularly, HIV+ Black MSM, stating that representation is important. In short, they argue that because Black MSM who are HIV+ operate in such a unique social location due to being “triply cursed,” representation and visibility is key to decreasing the number of Black MSM diagnosed with HIV. The act of hiring Black HIV+ MSM is a way to combat systemic oppression within the community.

Travis, Little Rock

You know what's wild? The CDC gave all of that money to Testing Makes Us Stronger, but did nothing to make sure more of us were hired to do the testing. So they put us up on some posters and internet, but when people go to get tested……we aint nowhere to be seen. It can be hard to approach people that aren't like you. I know some Black guys are homophobic so I desperately need for a community organization to make me feel safe and secure. Even sometimes with Black gay men….I feel like when I say I am HIV positive, they judge me. Being positive and negative are two very different experiences. We need more HIV positive people in organizations because they know what we need.

Discussion

Although other studies have analyzed exposure to Testing Makes Us Stronger, this was the first to analyze the campaign through a critical cultural approach, yielding several implications. First, respondents were aware of the systemic barriers that influence increased rates of HIV transmission in the Black MSM community. Drawing on their own experiences, they argued issues like homelessness and economic opportunities are not mere by products of HIV, instead, they are critical factors increasing rates of HIV; therefore, when discussing HIV, social marketing campaigns alone are simply not enough. Combatting rates of HIV transmission is undoubtedly a public health issue, but it is one that must be addressed from multiple angles including public policy, education, mental health, and housing. The spread of HIV in the Black MSM community is one rooted in social determinants of health. The Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion (ODPHP) recognizes the impact of social determinants on health outcomes. According to the ODPHP's Healthy People 2020 campaign, social determinants of health are “conditions in the environments in which people are born, live, learn, work, play, worship, and age that affects wide range of health, functioning, and quality-of-life outcomes and risks [The Office Of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion (ODPHP), 2019, p. 1]. Examples of social determinants echoed by respondents include: availability of housing, access to quality education, affordable health care, and food insecurity. Following CCA would allow for researchers to identify the myriad of systemic factors that influence one's risk of contracting HIV.

Second, analysis shows the importance of applying CCA to social marketing campaigns. For example, social marketing contends place, or a location where a desired behavior is important; applying CCA to campaigns forces researchers to evaluate if the place is accessible to the target population. Additionally, price, or the sacrifices one makes to engage in behavior, is undoubtedly culturally constructed; cultural norms of testing, HIV status, homophobia, and stigma are all incredibly important to the Black MSM community (Arnold et al., 2014). Third, analysis reveals TMUS focused on the wrong “product.” The campaign was framed around testing, but analysis revealed that for our respondents, testing alone is not how we are going to mitigate HIV in the Black MSM community. As one respondent indicated, one could test positive for HIV, and still, have no clear trajectory or plan for accessing and affording care. Worse, a positive diagnosis in conjunction with severe economic disenfranchisement may lead one to adopting a fatalistic mentality. The campaign seemed to assume the target population had no desire to get tested, but findings from this study suggest otherwise. High locus of control or increased perceptions of self-efficacy are rendered obsolete if one (1) does now know where to get tested, (2) can't afford testing, and (3) has no ability to get to the testing location. Additionally, accepting the premise of testing being the foundation of a HIV mitigation strategy also assumes doctors and healthcare workers are willing to overcome their HIV related stigma, yet, studies reveal stigma runs rampant. Social marketing campaigns must focus on the various stages of the HIV care continuum; it is imperative that researchers and scholars do not view testing in a vacuum. As a respondent stated, it is a piece of the pie, not the entire pie. I argue these multiple campaigns can and should be run concurrently. For example, TMUS could have simultaneously be run with an Undetectable=Untransmittable campaign, targeting individuals at various stages of the HIV care continuum. Fourth, as the last theme revealed, many respondents felt silenced, scrutinized, and shut down by national organizations. In addition to this, the lack of trans inclusion in the TMUS highlighted a disconnect between the campaign goal and community perceptions, highlighting the importance of community based participatory research. Previous research from Kreps (2015) and Noar et al. (2010) has already established the importance of proper message tailoring and audience segmentation, and community based participatory research reinforces this importance. Similar to CCA, community based participatory research avoids a top down approach to health campaigns, instead, it invites community members, organizational representatives, and academic researchers to contribute and comment on all phases of the research process (Rhodes et al., 2010). As articulated above, CCA encourages a paradigm shift, where agency should exist within the community, not just researchers. Respondents in this study would agree; according to the respondents, TMUS would have been more effective if the voice of the community would have been allowed to permeate through the entire process, ranging from defining the problem to implementation of campaign materials. Instead, they felt as if they were told what they could do as well as when and how they could do it; simply put, their agency was taken away. Local community organizations ought to always have a seat at the table.

Limitations

This study possesses various limitations. First, it used snowball and purposive sampling, relying on individuals to reach out to their individual networks. This type of sampling could skew results by relying on people who are already well-connected and knowledgeable. For instance, each individual interviewed is employed and experienced in HIV advocacy, therefore, their critique and read of the campaign may be different than someone who is not involved in health promotion. Also, the author made an announcement at several national conferences related to HIV, but many organizations do not have funding to send individuals to such conferences. Next, while there were multiple respondents from the Deep South, none of the interviewees reported living in rural communities. This is an area ripe for future research, especially considering HIV continues to rise in the rural South. Second, despite conducting member checks, the analysis of the data relied on one coder, but different researchers may code interviews in vastly different ways (Saldaña, 2016). Lastly, as with any qualitative study utilizing interviews, the findings are not designed to be generalized, instead, they only represent the opinions and perceptions of the 20 respondents.

Conclusion

Rates of HIV transmission continue to rise in the Black MSM community. Health campaigns, such as Testing Makes Us Stronger, have been implemented, but have had limited success. Quantitative studies have illustrated the promise of the campaign's exposure, but there is a lack of research surrounding community perceptions and understandings of the campaign.

Qualitative interviews and thematic analysis revealed TMUS not only failed to account for various structural barriers, including homelessness, poverty and education, but it also ignored the voices of community members and local organizations. Future health communication campaigns should utilize CCA as a lens to unpack how culture, systems, and agency influence one's access to HIV care across the continuum.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated for this study are available on request to the corresponding author.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by IRB George Mason University. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author Contributions

All of the ideas and writing presented were conducted solely by the corresponding author.

Conflict of Interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Footnotes

1. ^Social Determinants of Health (2019). Available online at: https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topics-objectives/topic/social-determinants-of-health (accessed December 11, 2019).

References

Adams, B., Krier, S., Netto, J., Feliz, N., and Friedman, M. R. (2018). “All we had were the streets”: lessons learned from a recreation-based community health space for young black MSM and trans women across the HIV prevention and care continuum. AIDS Educ. Prev. 30, 309–321. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2018.30.4.309

Amirkhanian, Y. A. (2014). Social networks, sexual networks and HIV risk in men who have sex with men. Curr. HIV/AIDS Rep. 11, 81–92. doi: 10.1007/s11904-013-0194-4

Arnold, E. A., Rebchook, G. M., and Kegeles, S. M. (2014). ‘Triply cursed': racism, homophobia and HIV-related stigma are barriers to regular HIV testing, treatment adherence and disclosure among young black gay men. Cult. Health Sex. 16, 710–722. doi: 10.1080/13691058.2014.905706

Boudewyns, V., Paquin, R. S., Uhrig, J. D., Badal, H., August, E., and Stryker, J. E. (2018). An interrupted time series evaluation of the testing makes Us stronger HIV campaign for black gay and bisexual men in the United States. J. Health Commun. 23, 865–873. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2018.1528318

Center For Disease Control (2018). Reaching for Health Equity. Retrieved from: https://www.cdc.gov/features/reduce-health-disparities/index.html (accessed February 3, 2020).

Center For Disease Control (2019a). Living With HIV. Retrieved from: https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/basics/livingwithhiv/index.html (accessed February 3, 2020).

Center For Disease Control (2019b). HIV and African American Gay and Bisexual Men. Retrieved from: https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/group/msm/bmsm.html (accessed February 3, 2020).

Center For Disease Control (2020). What is HEALTH Marketing? Retrieved from: https://www.cdc.gov/healthcommunication/toolstemplates/WhatIsHM.html (accessed April 27, 2020).

Centers for Disease Control Prevention (2019). HIV Surveillance Report, vol. 30. Available online at: http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/library/reports/hiv-surveillance.html (accessed April, 2020).

Clerkin, E. M., Newcomb, M. E., and Mustanski, B. (2010). Unpacking the racial disparity in HIV rates: the effect of race on risky sexual behavior among black young men who have sex with men (YMSM). J. Behav. Med. 34, 237–243. doi: 10.1007/s10865-010-9306-4

Creswell, J. W. (2007). Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing Among Five Traditions. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

CROI Press Release (2016). Lifetime HIV Risk CDC. Available online at: https://www.cdc.gov/nchhstp/newsroom/2016/croi-press-release-risk.html (accessed September 29, 2019).

Dutta, M. J. (2018). Culture-centered approach in addressing health disparities: communication infrastructures for subaltern voices. Commun. Methods Meas. 12, 239–259. doi: 10.1080/19312458.2018.1453057

Farrelly, M. C., Nonnemaker, J., Davis, K. C., and Hussin, A. (2009). The influence of the national truth® campaign on smoking initiation. Am. J. Prev. Med. 36, 379–384. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.01.019

Gayles, T. A., Kuhns, L. M., Kwon, S., Mustanski, B., and Garofalo, R. (2016). Socioeconomic disconnection as a risk factor for increased HIV infection in young men who have sex with men. LGBT Health 3, 219–224. doi: 10.1089/lgbt.2015.0102

George, C., Adam, B. D., Read, S. E., Husbands, W. C., Remis, R. S., Makoroka, L., et al. (2012). The MaBwana black men's study: community and belonging in the lives of african, caribbean and other black gay men in Toronto. Cult. Health Sex. 14, 549–562. doi: 10.1080/13691058.2012.674158

Goffman, E. (1974). Stigma: Notes on the Managment of Spoiled Identity. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books.

Grier, S., and Bryant, C. A. (2005). Social marketing in public health. Annu. Rev. Public Health 26, 319–339. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.26.021304.144610

Habarta, N., Boudewyns, V., Badal, H., Johnston, J., Uhrig, J., Green, D., et al. (2017). CDC'S testing makes Us stronger (TMUS) campaign: was campaign exposure associated with HIV testing behavior among black gay and bisexual men? AIDS Educ. Prev. 29, 228–240. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2017.29.3.228

Harper, G. W., Tyler, A. T., Bruce, D., Graham, L., and Wade, R. M. (2016). Drugs, sex, and condoms: identification and interpretation of race-specific cultural messages influencing black gay and bisexual young men living with HIV. Am. J. Community. Psychol. 58, 463–476. doi: 10.1002/ajcp.12109

Hernández-Romieu, A. C., Sullivan, P. S., Rothenberg, R., Grey, J., Luisi, N., Kelley, C. F., et al. (2015). Heterogeneity of HIV prevalence among the sexual networks of black and white men who have sex with men in Atlanta. Sex. Transm. Dis. 42, 505–512. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0000000000000332

HIV.gov (2018). HIV Care Continuum. Content Source: HI.gov Date last updated (2018). Available online at: https://www.hiv.gov/federal-response/policies-issues/hiv-aids-care-continuum (accessed September 29, 2019).

Jeffries, L., Gelaude, D. J., Torrone, E. A., Gasiorowicz, M., Oster, A. M., Spikes, P. S., et al. (2015). Unhealthy environments, unhealthy consequences: experienced homonegativity and HIV infection risk among young men who have sex with men. Global Public Health 12, 116–129. doi: 10.1080/17441692.2015.1062120

Johnson, M. (2017). Report Highlights Challenges of HIV Care in Rural Deep South. Available online at: https://www.healio.com/infectious-disease/hiv-aids/news/online/%7B4d662af4-d50e-4afb-91ea-f64f843526b0%7D/report-highlights-challenges-of-hiv-care-in-rural-deep-south (accessed September 29, 2019).

Kalichman, C., Pellowski, J., Kalichman, M. O., Cherry, C., Detorio, M., Caliendo, A. M., et al. (2011). Food insufficiency and medication adherence among people living with HIV/AIDS in urban and peri-urban settings. Prev. Sci. 12, 324–332. doi: 10.1007/s11121-011-0222-9

Kreps, G. L. (2008). Qualitative inquiry and the future of health communication research. Qual. Res. Rep. Commun. 9, 2–12. doi: 10.1080/17459430802440817

Kreps, G. L. (2015). Health communication inquiry and health promotion: a state of the art review. J. Nat. Sci. 1:e35.

Lee, N., and Kotler, P. (2016). Social Marketing: Behavior Change for Social Good. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications.

Maulsby, C., Millett, G., Lindsey, K., Kelley, R., Johnson, K., Montoya, D., et al. (2013). HIV among black men who have sex with men (MSM) in the United states: a review of the literature. AIDS Behav. 18, 10–25. doi: 10.1007/s10461-013-0476-2

Mayer, K. H., Wang, L., Koblin, B., Mannheimer, S., Magnus, M., Rio, C. D., et al. (2014). Concomitant socioeconomic, behavioral, and biological factors associated with the disproportionate HIV infection burden among black men who have sex with men in 6 U.S. cities. PLoS ONE 9:e87298. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0087298

Millett, G. A., Peterson, J. L., Flores, S. A., Hart, T. A., Jeffries, W. L., Wilson, P. A., et al. (2012). Comparisons of disparities and risks of HIV infection in black and other men who have sex with men in Canada, UK, and USA: a meta-analysis. Lancet 380, 341–348. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60899-X

National Minority AIDS Council (NMAC) (2013). RISE Proud: Combating HIV Among Black Gay and Bisexual Men (Rep.). Retrieved from: http://www.nmac.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/05/Action-Plan_6.5.13.pdf (accessed April 27, 2020).

Nelson, L. E., Wilton, L., Zhang, N., Regan, R., Thach, C. T., Dyer, T. V., et al. (2016). Childhood exposure to religions with high prevalence of members who discourage homosexuality is associated with adult HIV risk behaviors and hiv infection in black men who have sex with men. Am. J. Mens Health 11, 1309–1321. doi: 10.1177/1557988315626264

Newcomb, M. E., and Mustanski, B. (2013). Racial differences in same-race partnering and the effects of sexual partnership characteristics on HIV risk in MSM. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 62, 329–333. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31827e5f8c

Noar, S. M., Harrington, N. G., Stee, S. K., and Aldrich, R. S. (2010). Tailored health communication to change lifestyle behaviors. Am. J. Lifestyle Med. 5, 112–122. doi: 10.1177/1559827610387255

Olson, K., Young, R. A., and Schultz, I. Z. (2016). Handbook of Qualitative Health Research for Evidence-Based Practice. New York, NY: Springer. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-2920-7

Quinn, K., Sanders, C., and Petroll, A. E. (2017). “Hiv is not going to kill me, old age is!”: the intersection of aging and hiv for older hiv-infected adults in rural communities. AIDS Educ. Prev. 29, 62–76. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2017.29.1.62

Ramirez, A. S., Rios, L. K., Valdez, Z., Estrada, E., and Ruiz, A. (2017). Bringing produce to the people: implementing a social marketing food access intervention in rural food deserts. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 49, 166–174.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jneb.2016.10.017

Rhodes, S. D., Malow, R. M., and Jolly, C. (2010). Community-based participatory research: a new and not-so-new approach to HIV/AIDS prevention, care, and treatment. AIDS Educ. Prev. 22, 173–183. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2010.22.3.173

Rimal, R. N., Brown, J., Mkandawire, G., Folda, L., Böse, K., and Creel, A. H. (2009). Audience segmentation as a social-marketing tool in health promotion: use of the risk perception attitude framework in HIV prevention in Malawi. Am. J. Public Health 99, 2224–2229. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.155234

Singh, S., Song, R., Johnson, A. S., Mccray, E., and Hall, H. I. (2018). HIV incidence, prevalence, and undiagnosed infections in U.S. men who have sex with men. Ann. Intern. Med. 168, 685–694. doi: 10.7326/M17-2082

Stringer, L., Turan, B., Mccormick, L., Durojaiye, M., Nyblade, L., Kempf, M., et al. (2015). HIV-related stigma among healthcare providers in the deep south. AIDS Behav. 20, 115–125. doi: 10.1007/s10461-015-1256-y

Sullivan, P. S., Rosenberg, E. S., Sanchez, T. H., Kelley, C. F., Luisi, N., Cooper, H. L., et al. (2015). Explaining racial disparities in HIV incidence in black and white men who have sex with men in Atlanta, GA: a prospective observational cohort study. Ann. Epidemiol. 25, 445–454. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2015.03.006

Testing Makes Us Stronger Poster (Digital image). (2011). Retrieved from https://npin.cdc.gov/web-tools/testing-makes-us-stronger-tmus-poster.

The Office Of Disease Prevention Health Promotion (ODPHP) (2019). Social Determinants of Health. Retrieved from: https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topics-objectives/topic/social-determinants-of-health (accessed April 27, 2020).

Tracy, S. J. (2010). Qualitative quality: eight “Big-Tent” criteria for excellent qualitative research. Qual. Inq. 16, 837–851. doi: 10.1177/1077800410383121

Keywords: HIV Testing, Center for Disease Control (CDC), Black MSM, disparity, critical, Testing Makes Us Stronger

Citation: Hawkins DS (2020) “What If I Aint Ate in 2 Days, Why the Hell Would I Want You to Poke Into My Arm”: A Critical Cultural Analysis of Testing Makes Us Stronger. Front. Commun. 5:26. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2020.00026

Received: 01 October 2019; Accepted: 14 April 2020;

Published: 07 May 2020.

Edited by:

Vinita Agarwal, Salisbury University, United StatesReviewed by:

Andrew R. Spieldenner, California State University San Marcos, United StatesElizabeth M. Glowacki, Northeastern University, United States

Copyright © 2020 Hawkins. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Deion Scott Hawkins, deion_hawkins@emerson.edu

Deion Scott Hawkins

Deion Scott Hawkins