- 1Chua Thian Poh Community Leadership Center, National University of Singapore, Singapore, Singapore

- 2School of Communication, Journalism and Marketing, Massey University, Wellington, New Zealand

- 3Department of Information Systems and Analytics, National University of Singapore, Singapore, Singapore

This paper reports the formative research findings of a culture-centered heart health intervention with Malay community members belonging to low-income households. The community-based culture-centered intervention entailed working in the grassroots with community stakeholders to tailor a heart health campaign with and for low-income Malay Singaporeans. Community stakeholders designed and developed the heart health communicative infrastructures during six focus group sessions detailed in the results. The intervention included building smoking cessation information accessible to the community, the curation of heart healthy Malay centric recipes, and developing culturally responsive information infrastructures to understand a myocardial infarction. The intervention sought to bridge the gap for the community where there is an absence of culturally-centered communicative infrastructures on heart health.

Introduction

Every year, ~17 million people die from poor heart health conditions (Patel and Preedy, 2016). Globally, heart disease remains the number one cause of death. Coronary heart disease (CHD) has emerged as a critical public health burden across the developed and developing world. The burden of poor heart health is distributed unequally across societies. In Singapore, CHD afflicts minority communities such as Malays and Indians more so than the majority ethnic Chinese population (e.g., Sabanayagam et al., 2009; National Health Survey, 2010). This paper reports a complete culture-centered intervention conducted with low-income Malay community members to address the heart health disparity faced. The results are based on six focus group discussions conducted as part of the formative research that went into developing the culture-centered heart health intervention. The formative research designed the heart health intervention materials for and with Malay community members from low-income households through a culture-centered process.

Building on the medical and public health evidence regarding ethnic disparities and heart disease (e.g., Sabanayagam et al., 2013; Rakun et al., 2019), we argue for heart health can be understood through the lens of racial, economic, and health inequality, by centering the voices of those most afflicted by the heart health burden. The Malay community faces jarring heart health disparities compared to other ethnic populations in the country (Sabanayagam et al., 2009; Kaur, 2018). This research expands on the racial, economic, and health disparities by specifically interrogating heart health meanings through the lens of low-income Malay Singaporeans that are socio-economically disenfranchised.

Heart Health Disparities

CHD often termed as a lifestyle specific heart disease, is a global public health concern. In Asia alone, CHD rates remain on the uprise (e.g., Khor, 2001; Lam, 2015). In lowering risks of CHD, the biomedical literature indicates the need for individuals to partake in risk-reducing behaviors, modifiable through lifestyle changes (Pencina et al., 2019). Modifiable heart healthy behaviors include smoking cessation, reduction of alcohol intake, diet, exercise, and the tackling of obesity (Sturgiss and Agostino, 2018). However, Kaur (2018) argues that for structurally disadvantaged communities, the lowering of risks is beyond lifestyle centered decisions. The inability to negotiate or access health structures are embedded in everyday disparities faced by disenfranchised communities. A critical challenge remains for communities unable to participate in modifiable heart healthy behaviors. These limitations include the knowledge of good heart healthy practices and access to biomedical infrastructures when requiring diagnosis and treatment (Kaur, 2018). Yet, the realities of heart health include communities that live with the disparity remain unable to navigate the complex heart health etiologies concerning the management of heart-healthy behaviors. In theorizing the relationship between health inequalities and economic inequalities, Farmer (2003) interrogates the limits to achieving the substantive opportunity to health access as the vicious effects of economic disenfranchisement that have material and social consequences, implicating an individual's ability to receive better health outcomes. Barriers to what may seem as lifestyle choices limit opportunity for communities to acquire good heart health practices or access modifiable heart healthy behaviors. The biomedical literature continues to grapple with risk factors that go beyond the traditional interpretations of risk. A recent study revealed the role of financial stress in the incidence of CHD among the African American population (Moran et al., 2019), while other studies have identified psychiatric conditions impacting extent (Allan et al., 2019; Hamieh et al., 2019), including stress from situations such as prolonged armed conflict (Jawad et al., 2019).

More recent studies are providing insight on heart health that move beyond the dominant readings of heart healthy behaviors as modifiable risk factors. Marmot and Allen's (2014) discussion on the social determinants of health equity indicates priorities toward the social determinants approach to smoking, obesity, and alcohol consumption. The social determinants approach reveals how individualizing health as lifestyle centered, fails to pay attention to external factors that drive poor health behaviors (Marmot and Allen, 2014). For example, Koh et al. (2010) share how often social determinants are an interaction of factors that heighten health disparities such as the geography, the population dynamics, risk factors, and nature of diseases faced. According to Koh et al. (2010), this approach helps to reframe how public health stakeholders recognize how conditions of inequity inform why socially disadvantaged groups face more significant disparities in health. The social determinants approach focuses on social and environmental factors as fundamental toward achieving more significant health equity among economically disenfranchised communities. For example, Chaudhry et al. (2011) study on racial disparities of heart health among Black populations in the United States located literacy on heart health as contributing to heart health disparities. Health illiteracy refers to the inability to acquire “a constellation of skills, including the ability to perform basic reading… tasks required to function in the health care environment” (p. 123). Disenfranchised Black populations in the United States were unable to negotiate the health care environment with limited literacy on heart health dysfunctions (Chaudhry et al., 2011). The health care environment operating from a biomedical framework is often a confluence of complex negotiations that create barriers for disenfranchised communities to access health systems.

In the Singapore context, a study by Kaur (2018) with low-income Malays found that they were often disadvantaged by lower levels of literacy, were digitally disconnected, impeding their ability to seek health information on heart health. This led to further disparities in heart health literacy. They were often unable to acquire information on the signs and symptoms of myocardial infarction (heart attack) or a stroke. Cameron's (2013) study with South Asians in the United States also indicated the role of health literacy that impacted heart health information seeking among the community. Cameron (2013) parlayed the role of communication messages toward improving equity in heart health through culturally responsive messages in health interventions. In assessing heart health literacy, cultural, and structural factors should be accounted for in understanding disruptions in managing good heart health practices.

In narrowing down the social determinants approach, Dutta (2016) conceptualizes the structural determinants of health approach to studying health inequalities. Dutta (2016) suggests that health experts pay attention to macro-structural factors as opposed to individualized responses to health inequalities when researching health inequalities. A similar critique is posed on how communication, public health, and, medical education literature often sells persuasion messages toward good heart health practices that remain based on individual lifestyle changes, such as persuading individuals to change their diets, to stop smoking, and to get more physically active (e.g., Schooler et al., 1998; Rimal et al., 1999; Mollen et al., 2013). Dutta (2007) critiques individual health promotion messages as limited in their capacity to achieve targeted heart health outcomes. Messages on healthy eating, smoking cessation, and exercise fail to capture the broader structural parameters that limit opportunities for economic disenfranchised communities from making heart health changes, where the “powerful advertising machinery of the sugary sweet drink industry, availability of spaces to exercise, opportunities for leisure amid work in multiple shifts to simply afford a living, and the role of stressors in the broader neighborhood environment on the desire to exercise (p. 2–3)” remain challenging for economically disenfranchised communities.

This study adopts a culture-centered approach (CCA) to design a heart health intervention to work through the health disparities in the context of disenfranchisement, moving away from the critiques of traditional methods to health promotion. We employ the theoretical and methodological tenets of the CCA in developing a community fronted intervention. Our research questions interrogate how heart health meanings are negotiated in the everyday lived experience of living in a low-income context? How do various structural forces influence and impact low-income Malay Singaporeans experiences of heart health?

The Low-Income Context

Operationalizing, who constitutes the low-income in Singapore, remains challenging with no official measure of poverty in the country (Tan, 2016). Academics studying the low-income context in Singapore have suggested a few indicators as critical measurements of families living in poverty (Glendinning et al., 2018). An estimate of 20–35% of households in Singapore resides in relative poverty within a population of 5.8 million (Donaldson et al., 2013; Smith et al., 2015). Relative poverty is conceptualized as taking into account “the standard of living in a society as well as social exclusion” (p. xi). Within this percentage, 110–140,000 approximate households are argued to reside in the absolute poverty spectrum, which means that basic needs remain challenging to meet for these households.

There is much debate on the existence of absolute poverty in Singapore with some scholarship using the Average Household Expenditure on Basic Needs (AHEBN) as a data point. According to Donaldson et al. (2013) report on poverty in Singapore, the AHEBN consists of “the average expenditure on food, clothing, and shelter in a reference poor household living in a one to two-room Housing and Development Board (HDB) or government rental flat, multiplied by a factor of 1.25 to account for other household needs like transport, education, and other necessary expenditures for normal living” (p. 60). Donaldson et al. (2013) study reported that based on parliamentary proceedings in 2012 that $1,250 household income per month was a potential indicator of absolute poverty in Singapore. The approximation would be fewer than 140,000 households were living within this range. The profile of individuals within this spectrum included the working poor, unemployed poor, and needy retirees (Donaldson et al., 2013).

Looking more specifically at the Malay community, there was a growing number of Malays that made up the demographic for one and two-room rental flats 1(Heng, 2016; Yayasan, 2016). The income eligibility criteria for rental flats were at SGD,1,500, acting as a potential indicator of living in either relative or absolute poverty. In Donaldson et al. (2013) report, relative poverty is most commonly calculated a 50% of the median household income and the should be within the income bracket of SGD 2,500. None of our participants in the study were within the relative poverty guide if we use the 50% of median household income measurement, as they lived in rental flats where qualification for living in a rental flat was SGD 1,500 and below. Kaur (2018) summarizes that poverty remains “an ideological barrier that has been socially engineered by the state in the framing of the national narrative” (p. 104), disrupting the possibility of rendering a thorough, immersive, and in-depth understanding of the challenges living in a low-income context (Tan et al., 2017; Teo, 2019).

Malay Disenfrachisment and Health Disparities

Malays in Singapore face multiple disparities. The literature indicates that the Malay population in Singapore face health, economic, and educational disparities (Mutalib, 2012; Chua et al., 2019; Rakun et al., 2019). In terms of education, housing, and socioeconomic status (SES), there are still critical gaps faced by the Malay community compared to the rest of the population (Mathew and Lim, 2019). Mathew and Lim (2019) elucidate that because Malays make up a significant number of residents in rental flats, a lack of homeownership remained another financial set back for the community in terms of asset consolidation. Heng (2016) reported that in 2016, there were double the number of Malay residents in rental flats in just over a decade from 4.9% in 2005 to 10.9% in 2015. These disparities act as barriers for the community to achieve health equity.

The medical literature indicates that both Malays and Indians in Singapore suffer from CHD disparities. Liu et al. (2016) study reported that Malays and Indians in Singapore suffered from diabetes mellitus, mortality from CHD, acute myocardial infarction, and end-stage renal failure more than the majority Chinese population in Singapore. Liu et al. (2016) caution the excessive risk of native Asians with type 2 diabetes (in reference to the ethnic Malay community) have to CVD. According to Liu et al. (2016), “the excess CVD risk in the Malay group may be attributable to the high prevalence of diabetic kidney disease” (p. 336). The disparity faced is further backed up by a population research report by Yayasan (2016), Singapore's Malay self-help organization indicating that Malays had the highest prevalence of cholesterol, obesity, and hypertension when compared to other ethnic groups in Singapore. Amenable mortality rates were highest among the Malays. Life expectancy gaps among the Malay community compared to the other two ethnic groups were also reflected (Lim et al., 2013).

Furthermore, the rates of smoking were most significant (both male and female) within the ethnic group. Exercise behaviors remained limited compared to other ethnic groups as well (Yayasan, 2016). Furthermore, research on the community itself found that Malay males and females had higher body mass index, reflected more elevated rates of smoking, more significant readings of systolic blood pressure, and hypertension (Mak et al., 2003; Morrow and Barraclough, 2003; Liu et al., 2016). Based on the ontological frameworks of biomedicine, all of these risks would be deemed potentially modifiable.

To further breakdown these disparities, Sabanayagam et al. (2009) interrogated the role of unemployment, educational qualification, and body fat ratio (overweight) to its relationship with diabetes mellitus and hypertension. Sabanayagam et al. (2009) found that socioeconomic status (SES) was related to a high body mass index (overweight/obese) among Malays, with women bearing a more substantial burden of the risk when they had lower SES. Obesity and poverty share a complicated relationship in the developed world where poverty could mean living with a higher risk of obesity (Alavi Hojjat and Hojjat, 2017). Studying the developed context of poverty and obesity, Alavi Hojjat and Hojjat (2017) position the argument that “obesity is truly a form of serious malnutrition” (p. 20). Healthier diets are harder to access among communities belonging to low SES households SES, face literacy challenges, and are more likely to be a minority community (Henderson, 2007). Challenges remain in the Singapore context as the discourse on poverty in the city-state are couched in ways that erase the experiences of those residing in impoverishment (Tan, 2016; Tan et al., 2017).

Theoretical Insight: Culture-Centered Approach to Disparities

The CCA adopts a critical perspective toward understanding structural disadvantages in its assessment of health disparities. Dutta (2008) informs that the structural determinants of health are built based on a free market ideology where health becomes a commodity to be purchased. “As a private commodity, health has to be purchased, with the rhetoric of personal choice, and individual responsibility inundating the neoliberal propaganda” (p. 2), where the management of health is individualized. Therefore, when studying disenfranchised populations facing health disparities, a structural reading is necessary. Starting from recognizing how low SES communities residing in health systems that operate on a neoliberal logic of health provision often are unable to access health institutions. In not being able to access health institutions, low-income patients may delay treatment or fail to comply with medication prescriptions for fear of health costs (Low et al., 2017; Suen and Thang, 2018).

Individuals from more impoverished communities are also left further disenfranchised when faced with chronic diseases. The poor in Singapore were more likely to suffer the chronic disease burden with a higher prevalence of deficient treatment and management of chronic disease (Wee et al., 2013, 2017). Access to health services remain limitedly used among low-income Singaporeans. A study by Wee et al. (2019) indicated that Singaporeans living in the country's public rental flat scheme for low-income Singaporeans had higher rates of healthcare utilization (emergency room visits and hospitalization). Yet, access and utilization of health resources such as informational services and interpersonal interaction with community health providers remain problematic for the low-income (Wee et al., 2013).

A central aspect of the CCA is configuring grounded up strategies on a community's structural challenges of health before solutioning to reduce disparities. By centering the relationship between culture, structure, and agency, an intervention is designed with community members (drawing from community agency) to address their lived experiences with heart health disparities. The culture of communities forms the guidelines, norms, understandings, frameworks, and membership cues. With local etiologies centered, culturally relevant and structurally accessible materials are developed.

The Culture Centered Approach to Participatory Research

In determining heart health interventions, the centering of a community's interpretation of heart health forms a starting point for building academic-community partnerships. Wallerstein and Duran (2010) interpret CPBR as a potential bridge that facilitates community praxis and social action, with science to achieve health equity. Knowledge hybridity that incorporates egalitarian practices of power-sharing, information dissemination, and the production of health resources by experts and community members is central to the CBPR process. The goal of CPBR, according to Wallerstein and Duran (2010), is in creating space for “translational intervention and implementation sciences to influence practices and policies for eliminating disparities” (p. 44). Hacker (2013) describes the goal of CPBR as “creating an effective translational process that will increase bidirectional connections between academics and the communities they study” (p. 2). Note here that the notion of equitability is grounded in academic power over the definitional terrains.

Several heart health interventions using CBPR found that empowering participants through participation in the research process produced culturally relevant and contextually focused health solutions (Taylor et al., 2005; Andrews et al., 2012). The Jackson Heart Study sought to address heart health disparities faced by the Black population in three Mississippi counties. The praxis focus of the CBPR process is in its promotion of equitability in getting all stakeholders involved in the research process and ensuring the centering of voice in deducing research goals, outputs, and outcomes (Taylor et al., 2005). CBPR as a research technique embeds involvement by community members as a fundamental principle of the approach (Hacker, 2013).

Culture-Centered Intervention

The CCA foregrounds the ownership of health infrastructures for participation in the hands of the margins (Dutta, 2008; Dutta et al., 2019). Community members are central in formalizing the key conceptualizations of intervention before the introduction of experts. Experts are fundamentally only present if community members articulate their need for facilitation. Community members remain the primary arbiters in facilitating, designing, and negotiating the intervention proposed. While this research began with a grant by the Singapore Heart Foundation awarded to the researchers for specifically the study heart health in the Malay community. The researchers located natural community organizers through the formative research process that assisted in connecting key stakeholders as primary facilitators of the culture-centered process. The intervention was fully developed by only community members that belonged to the low-income context. Local articulations of knowledge are central throughout the building of the intervention. Recognizing communities at the margins as generators of knowledge turns ownership as the basis for the academic-community relationship, with communities at the margins taking charge of owning the research process, outcome, and output. The culture-centered process thus foregrounds structural transformation as the basis for transfiguring existing power relationships (Dutta, 2008).

Adopting this approach includes thinking about how knowledge is created and shared with communities' local articulations, shifting the power dynamics from the academic partner to the community. The consolidation of power in the academe is shifted, where communities are at the center of the knowledge production process. The promise of a culture-centered intervention lies in envisioning a social justice approach to health by interrogating the very knowledge structures that form the basis for the development of health interventions, with the design and implementation moving beyond empowerment to transforming relationships of power that enable designing and implementing for health equity (Dutta, 2011).

With this understanding of heart health disparities as reflective of everyday inequalities, we begin by asking the meanings of heart health of the Malay community in Singapore. In the culture-centered intervention depicted in this manuscript, we sought to locate localized articulations of heart health meanings, which in turn formed the basis for the community designing a community negotiated intervention that pays attention to the limitations faced in achieving equitable heart health.

Method

A CCA intervention involves the organizing of community members in the solutioning process. This experience can be unique, depending on how community members identify the norms and guides of inclusion and exclusion. In culture-centered interventions, these norms and guides are rewritten based on the infrastructures of subaltern voice. We recruited 15 low-income Malays for six focus group sessions to design and implement health promotion material on heart health in the Malay community. For this specific project located within low-income spaces of Malay communities, the notions of heart health remain complexified amidst the negotiations of community norms.

As researchers, our imaginations of low-income Malay community spaces existed to only capture specific ethnically centered community members within our initial research design. Yet, the low-income Malay community members who participated in our initial dialogues rendered these spaces open and invitational, always inviting members living within the rental flat vicinity to join in the discussions and activities. During the launch event, members from the low-income neighborhoods from all races could participate and learn from the heart health materials developed as specified by community members on the project. Tenets of the CCA locate the rules and norms of participation to be set by those in the margins (Dutta, 2011). These rules and norms articulated by our initial Malay advisory group members envisioned participants in the advisory boards as friends and neighbors that were not ethnically Malay. Community members were invitational for other low-income neighbors to learn about their heart health, thus creating a dialogic space that is open-ended, inviting others from the margins. In sum, using CCA meant that even in participatory design, expert control is removed, transforming what it means to develop an intervention constituted amidst centering community agency.

Context of Recruitment

In approaching the community-centered research study among low-income Malay families, we first needed to identify participants that shared membership norms within a rental flat neighborhood that had strong social networks within specific estates. The formative part of the study included both purposive and convenience sampling of low-income Malay households to understand their meanings of heart health, including reaching out to low-income Malay families by knocking on rental flat doors or through connections with locality-based Malay committee members in the area. In the process, we met with an informal community leader who knew all the Malay residents living in the rental flats and terms of recruitment were directed and organized through the community organizer. With her assistance, we were able to organize six focus group sessions with 12–15 participants for each session. For this research paper, we analyze the focus group findings.

The entire study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) at the National University of Singapore (approval certificate 2484). As community members typically drive culture-centered interventions, we had to go back and forth with IRB for each phase of the project to ensure that the IRB was updated. Due to vulnerability issues, IRB states that all identifiers, such as names or any other details, must be anonymized. Written consent for the collaterals designed were taken from participants featured in them.

All the focus group participants identified themselves as belonging to the community of place (residential estate), residing with each other among three rental flat blocks located next to each other. This meant that many participants were neighbors and friends. Participants ranged from the ages of 25–70 with higher attendance by females than male counterparts. On average, each focus group consisted of 7–9 females and 3–4 male participants. Participants were also generally belonging to the middle to older age groups, with most of them aged 45 and above. The focus group sessions ran for 75 to 150 min each and were conducted under the rental flat blocks known as void decks. At the void deck, there are typically grassroots or NGO organizations that have an office or space for communities to use. We were able to get in touch with a local NGO that provided a space for the focus group discussions. Participants just needed to take lift down from their blocks to get to the center, enabling greater participation and attendance. Even though we did not specifically target participants that had a prior heart health episode such as a heart attack, high blood pressure, high cholesterol, or diabetes, all except two of our participants had heart health-related health conditions.

Data Collection and Analysis

Upon forming the focus group, we ran a total of six focus group sessions with open-ended questions on meanings of heart health, lived experiences with heart health, challenges faced, and heart health knowledge and current resources. These open-ended questions allowed the community members to begin building the intervention. From there, participants articulated during the focus group session both the challenges to achieving good heart health as well as contributed to the solutioning of culturally-centered material. The focus group data went through a constant process of iteration and reiteration during the coding process with the researcher working with community members on coding the data. All findings were discussed and analyzed with community members throughout the sessions. We worked toward familiarizing ourselves with the initial dataset (first and second focus group data) and coded them (Vaismoradi et al., 2013). The coded dataset was then brought back to the community to discuss before deciding on how the intervention will be designed. The coded set informed our themes. In Table 1 below, we summarize how the codes generated the themes in our findings.

Breaking Down Heart Health Meanings

The first theme addresses how the community broke down their understandings of heart health. When facilitators asked the participants about heart health, some participants were unable to detail what heart health meant in their meaning formations. What are your challenges with heart health was a salient starting point of the first focus group discussion, where we were met with responses such as “tak paham terus” which directly translates to “don't understand at all.” Other meanings also emerged such as referring to heart health to “jantung berlubang (heart murmur).” The absence of an ontological category for meaning-making can be understood as the lack of ability to make sense of information about CHD or related practices of good heart health from the biomedical literature. This lack of ability to make sense of the traditional definitions of heart health was salient among the majority of the participants. The confusion with other forms of cardiovascular illnesses that were not lifestyle-related was also limiting the understandings of heart healthy practices such as references to heart murmurs in their definitions of heart health.

There was a limited reference to a single conceptualization of the heart health aligned with the biomedical readings of CHD. Instead, the meanings of heart health included the absence or limited knowledge of heart health related material. There were also specific individual interpretations of heart health understandings. A few participants pointed out that poor heart health was often linked to other heart health dysfunctions that were non-modifiable such as a heart murmur. The sharing also entailed heart health understandings that did not fit into the dominant categories of CHD, such as linking it with “having a hole in the heart.” When we probed further, participants were referring to the biomedical term known as the ventricular septal defect. Participants described poor heart health descriptions as “like lung, blocking smoking like this can cause jantung (heart) not to function” or “stress.” While others mentioned its relationship with “high cholesterol can also get stroke.” What these understandings told us is how heart disease was also shaped by behaviors. However, they did not interpret these behaviors as lifestyle choices but conditions of dysfunction and stress. These understandings were valuable in terms of assessing the different ways in which participants reflected their interpretations of risk factors vs. how the biomedical frameworks impose the language of lifestyle risk factors as amplifying CHD. When asked if participants have had a heart health episode such as a heart attack, Hashim one of the participants related,

“I don't know whether heart attack, but I go to doctor, my private doctor check me, ask me to take all the medicine, and then straight go to hospital, and then the hospital stay there for four months. I stop smoking…every morning I take two medicine…one small one big…an inhaler twice a day…that's it”

When we probed further, Hashim was at a loss in breaking down this information further. He was unable to explain to us in detail the heart attack episode, but he knew that he was diagnosed with a heart issue.

Among other participants, the articulations of heart health often engaged meaningfully with specific symptoms. For instance, high blood pressure often emerged as an anchor for community discussions. When the facilitator asked the participants if they had “tekanan darah tinggi” known as high blood pressure, a majority of participants exclaimed a resounding “yes.”

A participant begins sharing her experience living with high cholesterol. Farah, shares that she was diagnosed with extremely high cholesterol,

“I got very high cholesterol, 100 mg I have to take…yes (in reference to making changes)…like lettuce.vege…no oily food…change…I go for my blood test…next week let's see what happens”.

Farah had wanted to address how to deal with her cholesterol levels in a more in-depth and culturally situated way. The focus group discussion also included asking participants if they thought heart health was a problem for the community, there was a collective response that reflected a resounding yes with a participant adding “of course la have.” All participants recognized that poor heart health was a problem in the community and the issue required attention. Heart health was discussed from several perspectives. These included its relationship to diabetes, high blood pressure, cholesterol, and asthma. Stress too was highlighted as part of the heart health conundrum.

Last but not least, smoking was also discussed especially concerning “causing a blockage in the lungs” by participants. Hashim shares “poor heart health because the lung tak (can't) function, blocking…smoking…all these… lung cannot function.” At this juncture, participants acknowledged that the first step to a heart health intervention meant the building of knowledge infrastructures for the community to understand what heart health issues were, and how to maintain a heart healthy lifestyle while residing as a low-income Malay member in Singapore. In coding their responses relating to knowledge infrastructures, the participants discussed what they thought were the reasons for the poor heart health situation among the community. There was a discussion about the attitudes of the community toward heart health, where a participant shares,

“because you never take care, you never eat the proper food, you know you got this heart problem, you follow what the doctor advise, just maintain your food, maybe can lower….”

While other participants query,

eat chillies eh, smoking, oily food. Over high smoking la”, “mesti ada minyak (consumption of overly oily food)”. Makan makan, then tidur….malas la…exercise….biase kan (eating and then sleeping…not exercising)”.

Here the participants converse suggesting that the food they eat is typically overly oily, and the lack of exercise are also factors that contribute to poor heart health. While others reiterated “tak paham (don't know).” These insights emerged when the facilitator asked what were the attitudes toward heart health in the community?

There was also a discussion on the “money situation” as a fundamental barrier toward diagnosing poor heart health symptoms. On the topic of money, a participant says, “sure if I have money, I will buy good good thing for myself (in reference to purchasing heart healthy foods)…all about money…”. The lack of financial assets informed the limitations of heart healthy choices. Money was also directly related to, therefore, as shared by a participant as being “takut pergi doktor (scared of seeing a doctor)” as it would involve having cash in hand which many members struggled with having financial assets. The low-income plight is often decision-making amid limited resources culminating into poor outcomes (Tan et al., 2017; Teo, 2019).

Smoking Conundrum

Participants also identified smoking as a critical challenge for poor heart health in the community. In the first focus group, it was quickly identified that smoking was a barrier toward achieving heart healthy practices. Participants understood that tobacco, in general, was bad for health, not just heart health. In further interrogating this question on understanding the repercussions of smoking for the heart, led to further inquiry on why smoking cessation was challenging. Sharifah began the conversation by suggesting that a barrier to good heart health “is that my husband is a heavy smoker.” In revisiting this question on smoking, a lot of contention also emerged in the room. As many participants did not want to discuss smoking when this topic re-emerged again in the focus group discussion, there was a dispute. Sharifah, the same participant that identified smoking as a barrier later, suggested that no one in the focus group smoked. Yet, two participants were later recorded as smokers. The interlocutor interpreted Sharifah's retraction as a potential denial amid other participant voices.

When the conversation on smoking was discussed again in the focus groups, participants then said that “they don't think that there are many who smoke” referring to community perception of smoking behaviors. Other participants emerged in the discussion suggesting that “it doesn't make a difference, some people who smoke also get heart diseases” with another participant adding that “my husband smokes, but the one who got a heart attack is me and I don't smoke.” A participant also added that it was, in fact, the act of smoking cessation as the point in which one falls ill. Indri shares,

“if you have smoked for a very long time, and you suddenly stop, you will also get sick. Those who have smoked for a very long time cannot stop smoking….my brother stopped smoking and after a year, he got very ill.

Smoking cessation was alluded as causing further stress to the body and harming it in the process. Participants also responded to questions on smoking by discussing the context of stress in relation to smoking. Overcoming stress was discussed as an underlying reason regarding cigarette uptake. While other participants revealed that smoking was difficult to curb because it was a problem of “habit and addiction.” Concerning “habit and addiction” participants were unaware of how to negotiate addiction behavior with some responding that “if one is not stress, they will smoke less… if they were more relaxed.” Here again, alluding smoking behaviors as linked to everyday stress as lived experience of a low-income individual.

Midway through the initial discussion on smoking, a participant expressed frustration on the topic of smoking. She too, was a smoker, and another participant had called her out on her smoking behaviors. She became frustrated in the process and then strongly verbalized “dont bring up smoking to me. It makes me angry… it is my right to smoke. Don't talk about my rights” to the participant next to her. In the process, we identified the stressors and challenges of discussing smoking as a heart unhealthy behavior while at the same time recognizing the affective responses toward smoking cessation. Stress was conceptualized in multiple forms in relation to smoking. Stress referred to financial rife faced that led to the need to smoke, while at the same time, smoking also alleviated everyday stressors of dealing with financial pressures.

In another example, the discussion on smoking re-emerges with the facilitator probing what are the barriers to quitting smoking. A participant responds, “because don't have money, that is why I smoke.” The facilitator laughs in confusion but pushes to ask again, “if you don't have money, how to smoke?” reflecting our privilege when thinking about the affordances of smoking behaviors from the point of view of financial accesses. From the facilitator's point of view, it was not possible to afford smoking if you did not have money, but from the participant's point of view, it is because one does not have money relating to a lack of finances that causes one to smoke. Smoking was a behavior of the deprived. If one had money, they would not need to smoke, relating smoke to stress. The stress from financial issues is central to the amplification of addiction to smoking again.

Smoking cessation re-emerged in a further focus group discussion with participants identifying the need to construct knowledge infrastructures on nicotine addiction and seeking medical help in resource-poor spaces. When asked if they have tried different techniques to curb smoking, participants shared, “I start chewing gum but it did not help my craving.” In terms of knowing spaces that provided smoking cessation services, participants shared that they had not attended any, with one participant Cik Ang who located advertisements on smoking cessation services in the newspapers. Counseling sessions were also challenging because of the caregiving needs of their children and grandchildren at home. Participant Halimah went further to discuss that counseling sessions were only effective if “both wife and husband to sit down together with the counselor and discuss their financial difficulties and how much money we are spending on smoking.” Cik Ang adds about her own husband's narrative “my husband have a heart attack and then he immediately stopped smoking after that…it is all about the mindset.”

Participants shared that the only time abstinence is possible was during the period of Ramadan where “it is possible to stop smoking during the fasting period but after breaking fast, I will breakfast with cigarettes.” Therefore, a good target for them to work with is not cessation entirely, but to reduce the number of cigarettes smoked. This led to the creation of the material on smoking cessation based on the needs of the community such accessing these resources that were available for free to break the addiction. The creation of the collaterals with the community during the focus groups are further documented in the section below on ‘Culturally responsive heart health material’.

Malay Is Food: How to Eat Heart Healthy?

Malay food emerged as the richest discussion on the conversation regarding heart health. One the one hand, everyday diet was a central category; participants were most willing to address and shift. On the other hand, the limitations of how to eat healthy Malay-centric food remained absent in their understandings. This was an essential aspect of knowledge infrastructures the community hoped to build together where there were no disparate viewpoints. A large part of the conversation began with the importance of Malay cuisine to their identities and their lived experiences. The process of sharing their cuisine was a central part of the value placed on the complex and unique way Malay food is prepared, while at the same time acknowledging that aspects of its preparation could be more heart health friendly.

Food was mentioned from multiple dimensions. The identification of food as a primary barrier toward achieving a healthy heart were explained in terms of the nature of eating practices and more specifically, diet consumption. Some of the excerpts relating to food included managing food “jaga makanan kita (don't know how to control food).” Here participants were referring to both quantity and quality of consumption. Others asked questions that attributed poor heart health to “eating more chillies eh…oily.” A participant questioned during the focus group discussions, “belachan sehat tak (is belachan healthy)?”. Belachan is a paste made of chili peppers and shrimp paste as two central ingredients. The process of making it that involves grinding and then frying the grinded mixture leaves participants confused about its health appeal. Yet, belachan was a key ingredient in many Malay centric dishes.

Other food queries involved the nature of eating such as “eating and then sleeping,” “you are what you eat,” while also suggesting that the kind of food the community eats is problematic “makanan kita (our type of food)” known as “malas” the act of not performing an activity. Amid these responses, were also a reflection of the lack of knowledge on “we don't know when to stop eating…. what food to take,” once again tying back to the broader theme of an absence of health information on what constitutes good heart health behaviors or how to look after once heart.

When questioned on oils known as minyak, sugars known as gula were posed, some participants acknowledge that there was little knowledge, but others mentioned that they “don't know at all.” For example, participants were unable to determine how much oil or sugar to use that did not border on at levels that were not healthy for the heart.

During the discussion, the kinds of rice utilized and how to select rice that was of better quality (white, brown etc.) emerged as well. On the conversation regarding what constitutes heart healthy or unhealthy food, participants were able to identify heart unhealthy Malay food. The facilitator begins by asking, “what are heart healthy foods located within the Malay food groups”? These were described in rich detail. A Malay beef stew called rendang was mentioned multiple times, with a participant describing the dish as “rendang tu dangerous (very heart unhealthy),” while another participant discusses “prata, mee goreng, nasi biryani, ayam goreng … tak sihat la (all of these are dishes located in the Malay and Indian Muslim food categories that were described as unhealthy).” Another participant proposes the possibility of steaming a Malay dish named nasi ayam, “nasi ayam boleh steam tak?” instead of other unhealthier methods of food preparation. The mention of soups and the process of steaming food also emerged. There was a discussion on the preparation of Singgang, a Malay fish soup. Here participants began discussing heart healthy recipes that were Malay centered, described as “must have the Malay flavor.”

One aspect of the discussion involved adopting other food groups that were outside of the Malay cuisine, such as whether or not there should be greater knowledge on eating and preparing Western-centric food groups such as yogurt, soups, and salads. All but one participant preferred navigating within these food groups for a healthier heart. One participant outrightly suggested that “I don't and won't eat western food.” A few participants discussed their fear of soups while acknowledging that “tomato soup…itu la makanan sehat [this is healthy food].”

Other elements regarding food from a low-income perspective included access to heart healthy foods found within the household. Sometimes these included canned rations from food distribution drives. Participants also discussed the nature of food prepared for consumption over a few days. With limited resources, food was made based on what could provide them with the most considerable amount, over a more extended period, as opposed to thinking through heart healthy methods of preparation. Other types of eating included seeking out food options relating to once finances, with a participant commenting “that everyone here has financial problems so they can [meant to be cannot] buy expensive good food.” Maintaining good heart health practices, therefore, was situated within the ambits of structural access and choice over resources.

Developing Heart Health Knowledge Infrastructures

Developing heart health knowledge infrastructures refers to detailing the process of developing community-centered material to conceptualizing the distribution of the content. Participants designed these during the focus group process. Participants discussed that “we want to target all the unhealthy people like us… within our neighborhood…around here la… banyak (many) Malay families here…can say majority ah…can say one block about 74.” In trying to target their intended audiences, participants indicated several concerns, including how many of their potential target audiences were in wheelchairs and needed to be addressed to receive the collaterals through door knocking exercises.

The critical themes involved, developing collaterals to undo the information disparity currently faced by the community on heart health. These included dealing with the lack of knowledge on heart attacks, centering the differences in gender by sharing the gender variation on some of these symptoms (refer to Figure 1). The second involved Malay-centered heart healthy recipes tailored explicitly for heart healthy cooking in a low-income setting that often involves limited food resources (refer to Figures 2, 3 for examples). The third focused on smoking cessation was tailored to be directed at potential community members with the structural access that provided the necessary resources for reducing addiction behavior, The goal of the material was to assist with smoking cessation cost-effectively (refer to Figure 4).

Channel Identification

A vital part of the discussions were in identifying mediums and channels for sharing the community-built knowledge infrastructures. There were extensive discussions regarding medium and channel use. Again, using a culture-centered intervention meant community members at the grassroots fundamentally identify the kind of channels they use to receive, seek, and share health information. Much of the heart health literature exist in spaces that are hard to access for low-income communities. These include heart health material online, mobile phones, social media, and other digitally unequal mediums. The elderly in Singapore remain excluded from the consumption of information communication technologies (ICTs) unable to familiarize themselves with the constant pace at which new technologies emerge and change (Tan and Chan, 2018). Gender and socioeconomic disadvantages also impacted technology use in Singapore (Cheong, 2007). Low-income and more specifically, low-income elderly participants had the least access to these resources on ICTs (Ee, 2012).

In working through the solutioning of challenges toward access heart health material, printed material remained the top choice for participants. Grassroots and local events were also highlighted as necessary in spreading information about heart healthy resources. Keeping to the tenets of the CCA, the best channels for information dissemination were determined by the participants as well, seen as experts of their communities. These included placing pamphlets that were meant to be placed in letterboxes were delivered through door-knocking instead. Participants discussed how a key strategy toward disseminating the heart health information meant ensuring immobile elderly were also receiving this information.

The process included a vibrant discussion on channels for health information seeking. Some participants suggested posters, but it was collectively agreed that the “posters would be torn up” and, therefore, would not allow for longer-term access to information. Pamphlets remained popular, but the discussion also highlighted the problem of disseminating pamphlets through letterboxes that would have good outreach. However, the participants also noted that the “letterboxes all lock la” therefore, limiting its reach. Members then shared the possibility of handing out these materials through word of mouth and community members. “SMS second choice” was discussed for sharing Malay centric recipes, referring to text messaging. However, they were concerned about the lack of mobile phone use, especially among the low-income elderly. Finally, participants reiterated their need for accessible channels and these included brochures and pamphlets that they could store and distribute efficiently to other community members via word of mouth.

Culturally Responsive Heart Health Material

In discussing the building of knowledge infrastructures to close the information gap on heart health, participants wanted to address three aspects. These were issues on smoking, closing the knowledge gap on heart health, and designing heart healthy Malay centric recipes. All of these needed to be accessible to their cultural and structural capacities. What this immediately meant was that the material could not be produced in English and it was instrumental to center the Malay language in the published content. In designing these materials, visuals were indicated as helpful in their understanding instead of the mere use of words. Concerning the generation of recipes that were heart healthy, for example, participants discuss “drawing the ingredients as opposed to writing them out,” reflecting a visual need to understand healthy ingredients. Keeping these factors in mind, our production designer worked with the community to go and back and forth with the designing of the collaterals.

Symptoms of a Heart Attack [Figure 1]

Figure 1, titled as “Serangan Jantung (Heart Attack)” and “Angin Ahmar (Stroke) formed the central component of the poster featuring elderly community participants as the key visual representations that would communicate central elements of the heart health message. This related to community members as central in identifying with the visual material and navigating the heart health information in a discernible way. The poster systematically depicted how to recognize and connect heart attack and stroke symptoms clearly, describing them in Malay through an interaction of visual and text. At the bottom of the poster, it provided vital contact information and what to prepare once a heart attack is identified. The two individuals featured in the poster were community-identified figures. Participants in the discussions voted among themselves to identify participants that will be featured in the material.

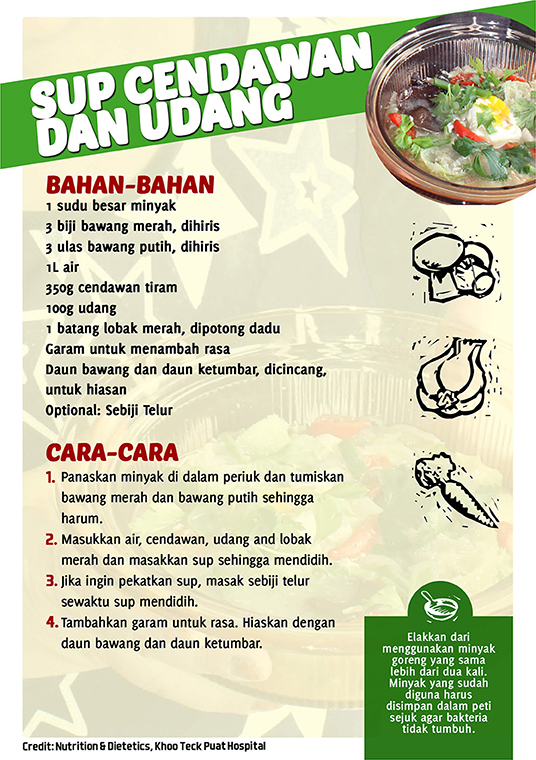

Malay-Centric Heart Healthy Recipes [Figures 2, 3]

Figures 2, 3 are examples of how the community specifically addressed eating heart healthy while factoring into account the low-income context of food resources. For example, Figure 2 is the overview of the recipe offered, followed by Figure 3 that provides that ingredient list and preparation techniques. Especially striking when adopting a participatory process was identifying positive deviance among Malay community members that were already preparing heart healthy meals. Researchers worked with these various community members to develop Malay-centric recipe guides from participants that were already practicing heart healthy cooking of Malay dishes. These recipes were discussed among researchers, community members, and the production designer. Ingredients were substituted, depending on the kind of food resources community members could access, while at the same time keeping the recipes heart healthy. Recipes acted as simple frameworks for heart healthy Malay-centric recipes where community members were able to substitute the basic ingredients if they were inaccessible. The recipes presented kept to the participants' need for “Malay flavor” that referring to the community's need to ensure Malay spices and techniques were engaged in the recipe design, while at the same time remained healthier options compared to other cooking techniques typically used in the preparation of Malay cuisine. These recipes ranged from a Malay porridge recipe, soups, and healthier version of fried rice that had reduced salt and more vegetables.

The recipes also featured the makciks (aunties) who constructed them during the focus group discussions. These dishes displayed are commonly prepared across Malay households, and the women adapted them to their families' needs. Here the women exercised their agency by sharing these recipes and then designing them in a way that is both resource and heart health accessible. In honoring their contribution, they displayed the recipes and themselves in the collaterals. Ownership and empowerment were central to the CCA process and their displays in the collaterals honored their authorship of these recipes.

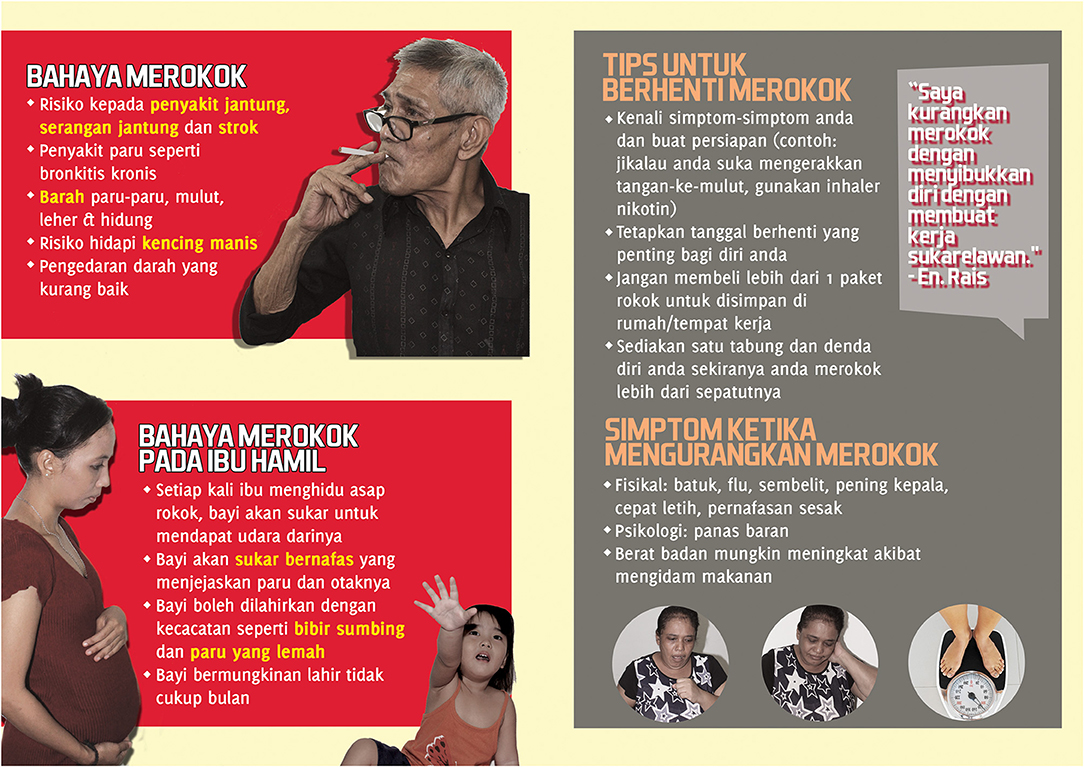

Smoking Cessation [Figure 4]

Figure 4 was aimed at building and connecting informational resources on smoking cessation for community members. The title “Berhentilah Merokok Sebelum Terlambat (Stop Smoking Before It is Too Late) was the crux of the tagline of the poster with three different representations constituting the face of the poster. As discussed, participants identified smoking as problematic across various community members and wanted different faces that represented potential target audiences in the community. The first red box on the top left featuring a Malay male detailed the dangers of smoking known as “Bahaya Merokok.” Just below the figure of the Malay male, the risks of smoking for pregnant mothers “Bahaya Merokok Pada Ibu Hamil” were highlighted detailing the effects on how smoking has an impact on the unborn fetus and young children. The other details in the poster included tips on how to stop smoking include some of the symptoms faced during the cessation period. These suggestions helped participants better understand how the body reacts during different periods when curbing the addiction. For participants, cessation could only happen if they were able to access free resources. Thus, researchers' located various health infrastructures across the island that provided these services. The free services for smoking cessation were highlighted in the content as well-indicated as “tempat tempat tersebut menawarkan kaunseling peribadi bahan-bahan pendidikan dan sesi (the venue offers personalized educational counseling and follow-up sessions during the process).

Post collateral development, community members then came together to organize a launch event with a clear objective of sharing, disseminating, and explaining the collaterals designed. Again, all members from the low-income space were invited including Chinese and Indian neighbors. The participants themselves distributed the invites. The campaign launch was titled, “Healthy Cooking” where the slogan for the entire campaign was “berjaga-jaga sebelum terlambat (take precaution before it is too late)” (Figure 4). The launch event was made possible through collaboration with the local community citizen center. Participants turned volunteers cooked healthy Malay recipes that were developed during the focus group discussions that included “nasi goreng (fried rice), bubur terigu (porridge)” among others.

Hundred community members attended the event with most of them above the age of 45 and an approximate 70% attendance of Malay individuals. The launch began with the distribution of brochures and postcards of which the focus group members had tried and tested (Figures 1–4 are examples). All of these materials developed and designed through the focus group process. Participants and facilitators provided a short talk in Malay explaining the collaterals and also spent time addressing a question and answer session. In the process, the manager of the citizens' corner translated the material for Chinese attendees and shared with them the nature of the collaterals in Mandarin. Focus group participants orchestrated simple games to facilitate greater interaction to ease comfort, to get participants to participate in answering questions on heart health located in the collaterals. The event specifics were chaired discussed by participants at the focus group meetings. The event was initiated and organized by community members to launch the material designed and developed.

Discussion

The most salient aspect of adopting a culture-centered health intervention is identifying the ontological limits of how participants framed heart health. In this study, the absences began from the very concepts and categories of what heart health entailed (coronary heart disease), depicting the lack of culturally grounded information architecture within the communities. In recognizing these absences, it became necessary to negotiate the definitional terrains in which academics work on/from. In selecting the meta-theoretical frameworks of the CCA to address health promotion in marginalized settings, the material realities of disenfranchisement connect to the everyday cultural and local meanings. A culture-centered intervention, therefore, provides the theoretical and methodological lens toward inverting the dominant power dynamics of health experts. Culture-centered readings on the knowledge gap reshape the definitional terrain, offering anchors to deep reflexivity about how “health problems” are framed for the margins. Lupton (1994) cautioned the lack of responsiveness to health promotion that fails to acknowledge and respond to the cultural context in which health meanings, understandings, and lived experiences are based. The culture-centered intervention tries to address this gap by paying attention to the socio-cultural environments where health promotion campaigns target.

While a similar heart health study was located by Kandula et al. (2012) for South Asians in America facing disparities in heart health, it did not utilize the fundamental tenets of a structure, culture, agency approach of the CCA. Heart health material were constructed for cultural targeting to the underserved South Asian population using pre-designed expert centered CHD material. The health promotion material remained biomedically framed. Changing the language of the material fails to pay attention to the various dimensions of culture and structure that limit participant negotiation in locating their health meanings. In community-based heart health research from a top-down information dissemination perspective, the assumptions regarding the meanings of heart health are already pre-defined for participants by research teams (e.g., Kandula et al., 2015). Participation then takes place through the negotiations of terminologies and meanings that have already been pre-configured and well-conceptualized. The biomedical literature discusses the heart from the cardiovascular, while at the same time continually tries to make sense of how modifiable lifestyle factors afflict the cardiovascular system.

In a seminal piece, the Dutta (2007) delineates how a CCA process is different from culture-sensitivity approaches conducted by Kandula et al. (2012). The participatory process in such studies causes no shift in the power dynamics of the researched. The locus of control held by experts vs. the community is often a central difference between a CCA study from a culturally sensitive approach (Dutta, 2007). Even though Kandula et al. (2012) and Kandula et al. (2015) study on heart health proved effective in addressing heart health risk factors based on a randomized controlled trial, it did not push for participants to take charge in the process of participation. Evaluating a CCA intervention is primarily based on centering community voice, undoing co-opted participatory practices, and democratizing power in health settings.

Community Grounded Heart Health Meanings

Community voice suggests that the spectrum of understanding of the cardiovascular system works through a different set of interpretations. The heart is viewed as a holistic system rather than the delineations based on modifiable and unmodifiable risk factors that result in poor heart health conditions. A study with African Americans where stress from structural racism contributed to heart health disparities, reveals the different interpretations and understandings of heart health challenges (Dutta et al., 2019). These articulations undo the hegemonic imposition on the framing of CHD. Yet, when participants take control of the research process, CHD meanings are refashioned, where CHD becomes a problem of limited choice and structural disadvantage. The language of lifestyle factors is challenged when participants conceptualize how behaviors are often far from agentic, removed from their ability to make any real lifestyle choices (Kaur, 2018).

Similarly, in the Singapore heart health study, creating culturally focused heart-healthy food choices remained insufficient in the articulations of low-income Malay community members. Community members needed the building of Malay-centric heart-healthy knowledge that would also center their financial and resource allocation challenges as central to their lived experiences and outcomes with heart health. In another example, smoking behavior, especially within low-income spaces, remained a site of active contestation locally. Even within the focus group discussions, smoking behaviors, and heart health often led to heated conversations. While many recognized that smoking behaviors were detrimental to health, smoking behaviors were also tied to managing everyday stress in the low-income context. National discourses have often vilified smoking behaviors among low-income individuals in connection to limited welfare provisions. Kaur (2018) discusses this further in a qualitative study on heart health meanings among low-income Malays,

“the purchasing of cigarettes by low-income participants are often viewed contentiously by actors of welfare provisions. Many see the consumption of cigarettes by low-income participants as a narrative that comes into direct tension with how needy participants are supposed to live. Our dominant assumptions of low-income participants manifest in particular ways that disallow us from interrogating their lives in complex ways” (p. 149).

This reference sums up the debate by structural actors on cigarette consumption and aid. In our focus group discussions, the analysis of cigarette consumption was far more complex and contested. Community members read cigarette consumption from various perspectives. For families, a smoking family member was embedded within relationships of care. Moreover, the behavior of smoking itself was situated amidst the multiple forms of stress created by structures and embedded within the structures. The understanding of smoking located in the realm of everyday stress, transformed the decontextualized construction of smoking behaviors as individual lifestyle choice, instead of constructing it as a behavior tied to stressors in the life of a low-income person, the negotiations of livelihood, and the struggles with making a living as a low-income individual in Singapore.

As detailed in the discussion on smoking cessation, a fundamental part of the process entailed locating centers and clinics that provided free services to assist with addiction behavior. Therefore, moving beyond just knowledge provision, but also identifying potential structural resources that could support community members in their negotiations of heart health. This led to the creation of structurally responsive materials that would assist community members in navigating the complex and unstructured distribution of heart health information in a culturally situated way. A structurally responsive intervention meant interrogating the deep relationship structure shares with culture in limiting access to resources. Community-based participatory research, for example, may construct responses that are community-centered, detailing cultural-sensitive ways to navigate health outcomes. A culture-centered intervention on the other hand, is situated at the structure, culture, agency nexus, thus reading both the enabling and limiting aspects of structure, locating community-driven solutions that are within a local understanding of a community's health behaviors and outcomes.

Limitations and Conclusion

Our approach to Malay Heart Health began by identifying localized articulations of heart health and building the knowledge capacity of the community by designing heart health scripts with the community. In the solutioning process, community voice centered as a key anchor toward the process of building these scripts. What remained a challenge with limited funding resources were opportunities to push the intervention further to include other themes that were identified, including building capacity for physical activity. Outreach remained challenging as well, with community members unable to participate in the discussions due to work schedules, caregiving, and disability issues. This meant that certain voices in the margins remained further disengaged in the process. Male participants in the study remained marginal as well. The participants in our research had also wanted greater engagement with Malay experts on nutrition and diet to further assist with the tailoring of Malay heart healthy recipe collaterals. Despite these challenges, participants took ownership and carried on learning and preparing new heart healthy Malay recipes at the local citizens' center located within the rental flat estates. Due to budget and funding issues, we were unable to tackle all the themes proposed by participants in the research process. Other limitations include the site of the study. The site of the study was narrowed to a specific physical location in Singapore. This was a mature estate [older residential estate] where Malay community members have lived for an extensive period and could potentially comprise an older low-income Malay population, leaving out other age groups belonging to the low-income space.

Other limitations also include the interlocuter's translation and interpretation of the voices of our participants during the focus group sessions. While all care was ensured such that the subjectivity of the researcher was limited in the relaying of the data, it must be mentioned that the interlocutor was not a cultural insider to the community. Despite Malay being the interlocuter's second language, specific meanings of lived experiences often required clarification. On page 13 (paragraph three), we see the challenges of dialogue between the interlocuter and the participants on the topic of smoking. This conversation required going back and forth to ensure participant voice was centered in the meaning-making of heart health understandings. To limit subjectivity, the interlocuter would provide constant clarification throughout the focus group with participants, before translation.

In the CCA process of participation, ownership was central toward empowering communities toward the sustainability of the broader goals of the project. Key learning from the participatory process is that communities are not passive toward heart health outcomes and were in fact, empowered to change their lived experiences with heart health disparities when they were actively involved. The participatory openings for participants to develop health knowledge also invert the presentation of illness by expert actors, demystifying biomedical language as the only framework for making sense of disparities from agentic health behaviors. The hegemonic production of heart disease requires critical interrogation for rendering a single story on individual behavior as a site of health behavior change.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated for this study will not be made publicly available due to the vulnerability of the participants as per IRB approval clause.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by National University of Singapore IRB. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author Contributions

All authors have contributed to both the research process and writing of the paper.

Funding

This work was funded by the RG2013/1 Singapore Heart Foundation.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Footnote

1. ^Rental flats refer to the Public Rental Scheme of retrieving heavily subsidized housing by the state (Housing).

References

Alavi Hojjat, T., and Hojjat, R. (2017). “Socioeconomic factors: poverty and obesity,” in The Economics of Obesity. SpringerBriefs in Public Health (Singapore: Springer), 19–25.

Allan, K. S., Morrison, L. J., Pinter, A., Tu, J. V., and Dorian, P. (2019). Unexpected high prevalence of cardiovascular disease risk factors and psychiatric disease among young people with sudden cardiac arrest. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 8:e010330. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.118.010330

Andrews, J. O., Tingen, M. S., Jarriel, S. C., Caleb, M., Simmons, A., Brunson, J., et al. (2012). Application of a CBPR framework to inform a multi-level tobacco cessation intervention in public housing neighborhoods. Am. J. Community Psychol. 50, 129–140. doi: 10.1007/s10464-011-9482-6

Cameron, K. A. (2013). Advancing equity in clinical preventive services: the role of health communication. J. Commun. 63, 31–50.

Chaudhry, S. I., Herrin, J., Phillips, C., Butler, J., Mukerjhee, S., Murillo, J., et al. (2011). Racial disparities in health literacy and access to care among patients with heart failure. J. Card. Fail. 17, 122–127. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2010.09.016

Cheong, P. H. (2007). Gender and perceived internet efficacy: examining secondary digital divide issues in Singapore. Women's Stud. Commun. 30, 205–228. doi: 10.1080/07491409.2007.10162513

Chua, V., Swee, E. L., and Wellman, B. (2019). Getting ahead in Singapore: how neighborhoods, gender, and ethnicity affect enrollment into elite schools. Sociol. Educ. 92, 176–198. doi: 10.1177/0038040719835489

Donaldson, J. A., Loh, J., Mudaliar, S., Md Kadir, M., Wu, B., and Yeoh, L. K. (2013). Measuring poverty in Singapore: frameworks for consideration. Soc. Space, 58–66. Available online at: https://ink.library.smu.edu.sg/lien_research/124

Dutta, M. J. (2007). Communicating about culture and health: Theorizing culture-centered and cultural sensitivity approaches. Commun. Theory 17, 304–328.

Dutta, M. J. (2016). Cultural context, structural determinants, and global health inequities: The role of communication. Front. Commun. 1:5. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2016.00005

Dutta, M. J., Collins, W., Sastry, S., Dillard, S., Anaele, A., Kumar, R., et al. (2019). A culture-centered community-grounded approach to disseminating health information among African Americans. Health Commun. 34, 1075–1084.

Ee, M. (2012). Prosperous State, Prosperous Old? Growing Social Stratification Among Elderly Singaporeans. Singapore: Asia Research Institute, National University of Singapore.

Farmer, P. (2003). Pathologies of Power: Health, Human Rights, and the New War on the Poor. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Glendinning, E., Shee, S. Y., Nagpaul, T., and Chen, J. (2018). Hunger in a Food Lover's Paradise: Understanding Food Insecurity in Singapore. Lien Centre for Social Innovation: Research (Singapore), 1–35.

Hamieh, N., Meneton, P., Wiernik, E., Limosin, F., Zins, M., Goldberg, M., et al. (2019). Depression, treatable cardiovascular risk factors and incident cardiac events in the Gazel cohort. Int. J. Cardiol. 284, 90–95. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2018.10.013

Henderson, L. J. (2007) “Obesity, poverty and diversity: theoretical and strategic challenges,” in Obesity, Business, and Public Policy, eds J. Zoltan, Z. Acs, and A. Lyles (Cheltenham: Edward Elgar), 57–77.

Heng, J. (2016). More Malay Families Living in Rental Flats. Retrieved from: https://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/more-malay-families-living-in-rental-flats (accessed October 9, 2019).

Jawad, M., Vamos, E. P., Najim, M., Roberts, B., and Millett, C. (2019). Impact of armed conflict on cardiovascular disease risk: a systematic review. Heart 105, 1388–1394. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2018-314459

Kandula, N. R., Dave, S., De Chavez, P. J., Bharucha, H., Patel, Y., Seguil, P., et al. (2015). Translating a heart disease lifestyle intervention into the community: the South Asian heart lifestyle intervention (SAHELI) study; a randomized control trial. BMC Public Health 15:1064. doi: 10.1186/s12889-015-2401-2

Kandula, N. R., Khurana, N. R., Makoul, G., Glass, S., and Baker, D. W. (2012). A community and culture-centered approach to developing effective cardiovascular health messages. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 27, 1308–1316. doi: 10.1007/s11606-012-2102-9

Kaur, S. (2018). Reducing Heart Health Disparities: A Culture-Centered Approach to Understanding Heart Health Meanings Among Low-Income Malay Community Members in Singapore (Doctoral dissertation).

Khor, G. L. (2001). Cardiovascular epidemiology in the Asia–Pacific region. Asia Pac. J. Clin. Nutr. 10, 76–80. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-6047.2001.00230.x

Koh, H. K., Oppenheimer, S. C., Massin-Short, S. B., Emmons, K. M., Geller, A. C., and Viswanath, K. (2010). Translating research evidence into practice to reduce health disparities: a social determinants approach. Am. J. Public Health 100, S72–S80. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.167353

Lam, C. S. P. (2015). Heart failure in Southeast Asia: facts and numbers. ESC Heart Fail. 2, 46–49. doi: 10.1002/ehf2.12036

Lim, R. B., Zheng, H., Yang, Q., Cook, A. R., Chia, K. S., and Lim, W. Y. (2013). Ethnic and gender specific life expectancies of the Singapore population, 1965 to 2009 - converging, or diverging? BMC Public Health 13:1012. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-1012

Liu, J. J., Lim, S. C., Yeoh, L. Y., Su, C., Tai, B. C., Low, S., et al. (2016). Ethnic disparities in risk of cardiovascular disease, end-stage renal disease and all-cause mortality: a prospective study among Asian people with type 2 diabetes. Diabet. Med. 33, 332–339. doi: 10.1111/dme.13020

Low, L. L., Maulod, A., and Lee, K. H. (2017). Evaluating a novel integrated community of care (ICoC) for patients from an urbanised low-income community in Singapore using the participatory action research (PAR) methodology: a study protocol. BMJ Open 7:e017839. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-017839

Lupton, D. (1994). Toward the development of a critical health communication praxis. Health Commun.6, 55–67. doi: 10.1207/s15327027hc0601_4

Mak, K. H., Chia, K. S., Kark, J. D., Chua, T., Tan, C., Foong, B. H., et al. (2003). Ethnic differences in acute myocardial infarction in Singapore. Eur. Heart J. 24, 151–160. doi: 10.1016/S0195-668X(02)00423-2

Marmot, M., and Allen, J. J. (2014). Social determinants of health equity. Am. J. Public Health 104, S517–S519. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.302200