- 1Department of Food and Resource Economics, University of Copenhagen, Copenhagen, Denmark

- 2Department of Sociology, Social Work, and Anthropology, Utah State University, Logan, UT, United States

- 3School of Communication and Media, Oregon State University, Corvallis, OR, United States

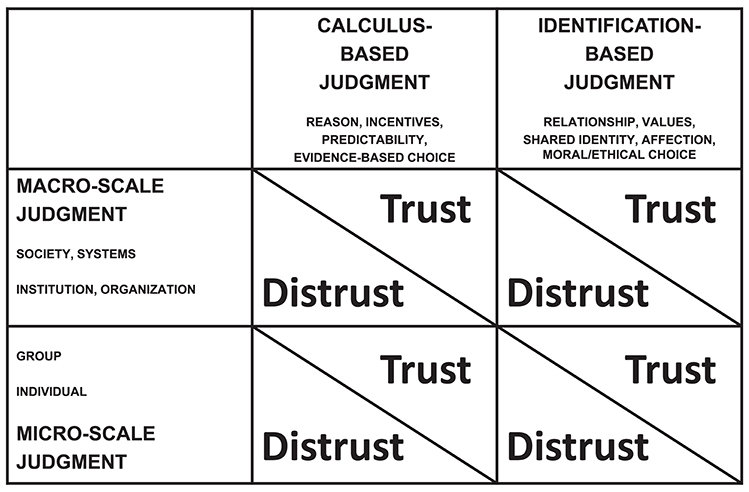

How can one simultaneously hold multiple trust judgments—some positive, some negative—and what relevance does this have to natural resource management processes? The paper examines trust through a lens of multiple simultaneous trust judgments, with application to the literature on trust in natural resource management. The conceptual contributions are (1) a clear distinction between trust and distrust, (2) how multiple trust/distrust judgments can co-exist, and (3) how multiple trust judgments can be assigned to individual vs. social/institutional scales. A framework for trust/distrust evaluation emerges in the form of a Trust/Distrust Matrix. One dimension of the matrix is the scales to which trust judgments may be assigned and one is the trust/distrust-judgments one makes that can either be calculus-based or identification-based. A set of propositions relevant to natural resource management are derived from the matrix. The fundamental purpose of this article is to bridge theory and practice.

Introduction

“I really trust Chris, our local Park Manager, but I don't trust the Parks Agency at all.”

Various permutations of this sentiment have arisen many times in the authors' collective experience as environmental facilitators and meditators. On face value, it appears inconsistent: how can you trust the local representative of an agency you fundamentally distrust? Trying to more fully understand such apparent contradictions serves as the point of departure for this article. The particular focus is on how an individual can simultaneously hold multiple overlapping and inter-related trust judgments. More intriguingly, how can some of those trust judgments be positive and others negative?

The fundamental purpose of this article is to build stronger ties between theory in trust scholarship and the practice of natural resource management. Trust is such an important concept that many disciplines have quite well-established research traditions on it. Our goal is to draw upon the general trust literature in a way that contributes to the natural resources-related literature by providing a framework that enables rigorous yet efficient analysis of simultaneous trust/distrust judgments. The most salient conceptual cornerstones of this article are (1) a clear differentiation between trust and distrust, (2) how multiple trust judgments can emerge and co-exist, and (3) how multiple trust judgments can be assigned at different social/organizational scales. The hope is that this framework can help natural resource managers on the front lines of controversial decision situations understand trust and distrust more completely and utilize that knowledge to move those situations in constructive directions.

This paper follows a straightforward path to achieve its objectives. First, we review key concepts in the theoretical literature on trust, striving to summarize the breadth of the ideas without either falling victim to paradigmatic partisanship or becoming entangled in the tall grass of terminology. Second, a trust-distrust framework is outlined, which is informed by both the general and natural resource-specific literatures. Finally, a series of propositions is presented that offers pragmatic suggestions on how to think through trust and distrust issues in the vertically differentiated administrative structures that characterize most natural resource management contexts. A selective review of the literature on trust in natural resource management is also presented as an Appendix.

Concept Review

In The Republic, Plato referred to trust as one of the four “affections arising in the soul” (along with intellection, thought and imagination, Bloom, 1968, p. 511d). Various philosophers (e.g., Kant, 1785; Gregor and Timmermann, 2012 trans) and social theorists [e.g., Simmel, 1950 (1908)] have wrestled with it since. It has been described as foundational to social order in that it allows for emergence of cooperative behavior. It fulfills this role by replacing uncertainty about how people will act with the belief that their behavior is in fact predictable.

Trust has been studied in a daunting range of disciplines (e.g., business, criminal justice, economics, organizational behavior, political science, psychology, and sociology), resulting in many conceptualizations of trust (Luhmann, 1979; Barber, 1983; Kramer and Tyler, 1996; Rousseau et al., 1998; Thomas, 1998; Kramer, 1999; Sztompka, 1999; Cook et al., 2005; Möllering, 2006; Lewicki and Tomlinson, 2014; Searle et al., 2018). Many conceptions of trust consider risk to be a defining parameter for “trusting situations” e.g., Lewicki and Bunker (1996), and Lewis and Weigert (1985) contending that trust “always involve an unavoidable element of risk and potential doubt” (p. 968). Trust has been described as “not mere predictability but confidence in the face of risk” (Lewicki and Bunker, 1996, p. 116). Along the same lines Boon and Holmes (1991) define trust as “a state involving confident positive expectations about another's motives with respect to oneself in situations entailing risks” (p. 194). Trust can under some circumstances be considered primarily a rational judgment based on a calculative assessment of a person's trustworthiness as well as the incentives in play (Deutsch, 1958; Lewis and Weigert, 1985; Gambetta, 1988; Ferrin et al., 2007), while under other circumstances trust might primarily stem from a relational, affective, or emotional basis that relates to the bonds of friendship, partnership, and love (Lewis and Weigert, 1985; Jones, 1996; Burke and Stets, 1999; Weber and Carter, 2003; van Knippenberg, 2018). This distinction has also been described as the “affective-cognitive duality of trust” (Baer and Colquitt, 2018, p. 172) and both must be taken into account as argued by Lewis and Weigert, 1985 (p. 972):”Trust in everyday life is a mix of feeling and rational thinking, and so to exclude one or the other from the analysis of trust leads only to misconceptions that conflate trust with faith or prediction1.”

Components of Trust

At its core, trust involves four components: (1) the trustor who is making the trust judgment; (2) the trustee, or target of the trust judgment (Mayer et al., 1995; Möllering, 2006; Baer and Colquitt, 2018); (3) the domain (area or type of behavior) to which the trust judgment is being applied (Lewicki and Wiethoff, 2000; Baer and Colquitt, 2018); and (4) the trust judgment itself (Luhmann, 1979; Lewis and Weigert, 1985; Möllering, 2006).

The (pre)dispositions of the trustor—the innate tendencies (or propensity) of an individual to trust or distrust is commonly seen as a major antecedent of trust at the individual level (Mayer et al., 1995; Kramer, 1999; Baer and Colquitt, 2018). The term “dispositional trust” emerges from the term “disposition,” referring to a person's personality or outlook. Dispositional trust is not (in our view) a specific type of trust judgment per se, as it is a predilection that makes certain trust judgments more or less likely than others. As such, two people might observe exactly the same behavior by a third yet draw substantially different trust inferences from it. From psychological research of personality traits, it seems evident that “people differ in their inherent propensity to trust” (Mayer et al., 1995, p. 715). Such individual personality differences in propensity to trust (or distrust) relate to the early psychosocial development, life experience and cultural background (Rotter, 1967, 1971; Mayer et al., 1995; Lewicki and Tomlinson, 2014). Propensity to trust seems to be a relatively stable within-party factor (Mayer et al., 1995), although trust judgments may be influenced by the affective state of the trustor (van Knippenberg, 2018). Trust development can be considered a self-reinforcing reciprocal process of exchanges between parties (Lewis and Weigert, 1985; Korsgaard, 2018), making trust dynamic in the sense that levels of trust will change over time in any relationship.

While the target of trust judgments (the trustee) is often another person, other scales of social organization can be trusted as well. Just as trust judgments can be made toward someone, so can they be made toward a family, a business, a profession, etc. To account for trust at the aggregated and abstract scale, scholars typically include a form of trust that primarily operates in relation to the social systems, institutions, roles, and functions of the society, i.e., systems-based trust (Luhmann, 1979; Lewis and Weigert, 1985; Misztal, 1996; Sztompka, 1999; Giddens, 2001; Möllering, 2006; Bachmann, 2018). This type of trust judgment is impersonal in that it is not assigned to an individual but is assigned to organizations (e.g., an airline or NGO) and abstract systems (e.g., education or government) (Luhmann, 1979; Misztal, 1996; Giddens, 2001; Gillespie and Siebert, 2018). Such impersonal assignment of trust is considerably more complex than interpersonal trust (Gillespie and Siebert, 2018) and might therefore be more diffuse in nature as described by Bachmann (2018, p. 219): “… a potential trustor has general, often diffuse, confidence in the functioning of social systems, irrespective of whether these are seen as a highly abstract set of rules or more concrete organizational structures.” In this sense “trust means having confidence in ‘abstract systems”' (Giddens, 2001, p. 680). Such systems-based trust draws on subtle socially constructed norms and learned social interaction patterns, which can be highly variable within a society, over time, between groups and from country to country (Fukuyama, 1995; Sztompka, 1999; Six, 2018). To the extent that trust judgments at this scale rely on the credibility, stability, standard procedures, and transparency of institutions and organizations, they could be seen as calculative, rational and rule-based. By the same token systems-scale trust judgments can arise from one's affiliation with institutions and adherence to the values they represent.

Trust judgments can also be specific to a particular domain, e.g., related to competencies, types of behaviors, or aspects of life—“we do not trust everyone equally in every situation” (Baer and Colquitt, 2018, p. 168). We may trust a person to excel in mathematics but not in sports or music. Similarly, trust judgments in a given context may vary according to perceptions of the target's trustworthiness with regards to technical competence vs. moral character and fiduciary responsibility, as discussed by Barber (1983) making the point that: “Trust as fiduciary obligation goes beyond technically competent performance to the moral dimension of interaction” (p. 15). As such, it is possible to trust a person (e.g., a government official) to have the skills needed, but not the fiduciary obligation and moral responsibility to carry through. To the extent that trust judgments are intuitively derived probabilistic inferences about a future behavior (e.g., “John could be late for his own wedding”) there is no reason to believe that the target's behavior would necessarily be the same in a different domain (e.g., “John could be an excellent parent”). With these examples it should be clear that it is entirely possible to hold several simultaneous trust/distrust judgments across domains within a given target of trust (Lewis and Weigert, 1985; Lewicki and Wiethoff, 2000). Obviously, in some relationships trust develops within only a few domains, while in other relationships trust may cover a broad range of domains. Some relationships may best be described as “full trusting relationships” with high levels of trust across most aspects of life, as it may develop among spouses, between child-parent, colleagues or well-established teams (mountaineering as a classic example). Such full trusting relationships are probably the exception rather than the rule in daily life, in which most relationships tend to be more ambiguous, somewhere in between with mixed levels of trust across domains depending on context over time (Lewicki and Tomlinson, 2014; Sitkin and Bijlsma-Frankema, 2018).

Trust, at its core, replaces uncertainty with belief. Möllering (2001, 2006) provides a detailed account of the trust judgment itself and the psychological state of trusting. Möllering draws on a thread of ideas grounded in the works of Simmel 1950 (1908); 1990 (1907), further developed by Luhmann (1979), Lewis and Weigert (1985), as well as Giddens (1991) who states that trust “presumes a leap to commitment, a quality of “faith” which is irreducible” (Giddens, 1991, p. 19):

Although the image of the leap of faith is a very fortunate one since it connotes agency without suggesting perfect control or certainty, I prefer to speak about “suspension” as the process that enables actors to deal with irreducible uncertainty and vulnerability. Suspension is the essence of trust, because trust as a state of positive expectation of others can only be reached when reason, routine and reflexivity are combined with suspension (Möllering, 2006, p. 110).

By suspending uncertainty and embracing vulnerability, trust reduces the complexity of social life (Luhmann, 1979; Möllering, 2006). The psychological state of trusting precedes the possible manifestation of trusting behaviors in any given situation and may be grounded in cognitive, emotional or social (systems) based processes that bridge from a known past into an unknowable future.

Research Approaches Into Trust

The expansive nature of the trust literature means that distinct lines of research or methodological paradigms have emerged which emphasize and operationalize these four components in various ways. Consistent with the distinction drawn by Hamm et al. (2017), one useful categorization is between an elemental approach and a forms of trust approach. The former flows out of Mayer et al. (1995) and focuses on attributes of the trustee –typically benevolence, ability and integrity—to determine why they are trustworthy. The latter approach, also referred to as a “bases of trust” approach, begins perhaps with Lewicki and Bunker (1996), followed by Rousseau et al. (1998) and further developed by Lewicki and colleagues (Lewicki and Wiethoff, 2000; Lewicki and Tomlinson, 2014). Without needing to declare the superiority of any particular school of thought, and valuing the contributions of both, this article flows primarily out of the forms/bases of trust tradition. One critique that trustworthiness-based researchers make of the forms of trust approach is that the different bases of trust lead to similar states of vulnerability for the trustor (Hamm, 2017), which complicates survey design and statistical inference. But that is exactly part of its usefulness in the pragmatic argument this paper presents because it readily accommodates the often contradictory impulses for positive and negative trust judgments in complex multi-party natural resource management situations.

A key distinction made in the forms of trust literature is between calculus- and identification-based trust judgments. Calculus-based trust, as it typically unfolds in transactional relationships, is “an ongoing, market-oriented, economic calculation whose value is determined by the outcomes resulting from creating and sustaining the relationship relative to the costs of maintaining or severing it” (Lewicki and Wiethoff, 2000, p. 88). Calculus-based trust/distrust judgments stem from a foundation of calculative reasoning, rational consideration of risks and benefits, and prediction based on available information, data, and experience—you trust someone because you have seen them reliably follow through on their past commitments. This form of trust may also be enhanced through a range of contractual/incentive structures designed to make trustworthy behavior both explicitly expected and also in all parties' best interests.

Identification-based trust is “based on identification with the other's desires and intentions. This type of trust exists because the parties can effectively understand and appreciate one another's wants” (Lewicki and Wiethoff, 2000, p. 89). Identification-based trust emerges from shared values, common goals, emotional bonds, identification with others' interests, concerns, and intentions; and judgments of other parties' value-systems, ethical and moral character. Identification-based trust embraces the conception of trust as encapsulated interests (Hardin, 1991, 2002), according to which “we trust you because we think you take our interests to heart and encapsulate our interests in your own” (Cook et al., 2005, p. 5). It also embraces the work of Earle and Cvetkovich (1995) pointing to the importance of shared values for trust development, as aptly captured by Siegrist et al. (2000, p. 356): “One has social trust in people who share similar salient values” in context of new technology and environmental risk. Identification-based trust can be activated by a suite of in-group markers (e.g., if I am a member of the Hikers Alliance, I may more readily trust another member) (Lewicki and Bunker, 1996), and it may be quite intuitive in that it “feels right” (van Knippenberg, 2018), or takes the “fast form” of “swift trust” as seen in temporary task or working relationships (Blomqvist and Cook, 2018). A sense of shared group membership or belonging can arguably create mutual understanding and the assumption that certain desires, values and intentions are shared.

In summary, the construct “trust” is a psychological state grounded in cognitive/calculative and affective/relational information and processes that bridges from a known past into an unknowable future. Trust judgments are often domain-specific and can be based on experience with that actor or can be enhanced by structures or incentives (e.g., calculus-based trust). They can also be informed by the commonalities and values alignment between the parties (e.g., identification-based trust). The target of trust can be an individual, a group, a concrete institution or an abstract social system. With that foundational understanding, we now turn our attention to the question of distrust as potentially distinct from trust.

Trust and Distrust: Two Distinct Judgments

Is distrust merely the absence of trust? Consistent with a growing body of research and in line with the most recent distrust reviews (Lewicki et al., 1998; Hardin, 2004; Bies et al., 2018; Sitkin and Bijlsma-Frankema, 2018) we consider distrust a distinct judgment rather than simply a lack of trust. Distrust, like trust, is a grounded judgment based on reasons/affections that require some familiarity with the target of the judgment. People can have specific reasons for distrusting someone else, and distrust may be a sensible response to potential dangers (Larson, 2004). Kramer captured distrust as a lack of confidence in the other, a concern that the other may act to do harm, or does not care about one's welfare and/or is hostile (1999). Suspicion has been considered a central cognitive component of distrust, as we suspect people to take advantage of us, fail to follow through on their commitments, exploit our good faith and good will, or manipulate the relationship to their own ends (Deutsch, 1958; Lewicki et al., 2006).

In essence we concur with the conceptualization that there are (at least) three different psychological states: unfamiliarity—before any form of trust judgment has yet been made; trust—a confident positive expectation of another's conduct; and distrust—a confident negative expectation of another's conduct (McAllister, 1995). This is clearly captured in the broad definition of distrust from van de Walle and Six (2014) that distrust is generally defined in terms of negative expectations toward people's intentions or behaviors, and concurs with the summary of Bies et al. (2018, drawing on Rousseau et al., 1998, Lewicki et al., 1998, and Lewicki et al., 2006) “that trust reflects positive expectations and willingness to be vulnerable to another, whereas distrust involves (pervasive) negative expectations and perceptions about the intentions or behavior of another” (p. 304, parenthesis added). Distrust (like trust) judgments are influenced by the judger's personality/propensity, mood, emotions and affective state. Certain persistent attitudes, such as those linked to cynicism, may play a significant role in the development of distrust and conceptualized as dispositional distrust (Andersson and Bateman, 1997; Dean et al., 1998; Macey, 2002).

Distrust is distinctly different from low trust, or absence of trust, which is the inability to make a trust judgment at all (Sitkin and Roth, 1993; Sitkin and Stickel, 1996; Sitkin and Bijlsma-Frankema, 2018). This distinction allows for a nuanced trust/distrust-analysis and presentation of aggregated trust/distrust-profiles across relevant trust/distrust-dimensions of a given situation where valid reasons (and/or affections) to trust occur in a mix with equally valid reasons (and/or disaffections) to distrust, as presented by Lewicki and Wiethoff (2000). Such nuanced trust/distrust judgments within a relationship can develop and exist across actions or domains of the relationship (I might trust him to drive me home, but distrust him look after my child) or be context specific (when it is late in the month I don't trust him to pay me back). Such different, co-existing and evolving trust/distrust judgments engender ambiguity and ambivalence in relationships (Bies et al., 2018). In some situations, domains, or times we may trust a certain person while yet in others we may have equally valid distrust of him/her, allowing for “incorporation of ambivalence (e.g., when both trust and distrust are simultaneously present) and multiplex relationships (i.e., trust in some domains in a relationship and distrust in others)” (Sitkin and Bijlsma-Frankema, 2018, p. 53). Lewicki and Tomlinson (2014) posit that those mixed reasons and judgments are likely to be either calculus-based or identification-based and that they all together form multifaceted trust relationships in which elements of trust and distrust co-exist. Further, they contend that “Relationships balanced with trust and distrust are likely to be healthier than relationships grounded in only trust” (p. 112) in particular in organizational, business and managerial relationships, where “unquestioning trust without distrust is more likely to create more problems than solutions” (p. 112). Trust and distrust are both likely present and fundamentally important in sustained relationships, since they lead to different beliefs, attitudes and behaviors. Initial distrust and/or breach of trust can lead to short-sighted opportunistic behaviors that tend to undermine the evolution of cooperation in the long run (Axelrod, 1984), while high trust levels facilitates cooperation (Gambetta, 1988; Deutsch, 2000, 2011). There can also be analogous intertemporal/cyclical dynamics; just as there can be gradually increasing layers of trust in an on-going relationship, there can also be “spiraling distrust” with significant negative consequences (Korsgaard, 2018; Sitkin and Bijlsma-Frankema, 2018).

Our professional experience as facilitator/mediators has led us to conclude that many natural resource situations are characterized by a substantial amount of clearly articulated and strongly held distrust judgments that can contribute to polarization and rancor. The accumulated costs of distrust can be high for individuals and societies, because inasmuch as trust tends to engender trust and the dividends of cooperation, distrust may be even more self-reinforcing, leading to division and decline (Bijlsma-Frankema et al., 2015). Merely conflating distrust with low trust is a blunt conceptualization that fails to anticipate the impact of the acrimony that can accompany distrustful relationships. This article's conceptualization of trust and distrust as being equally confident conclusions arising from analogous (cognitive/affective) processes is very different from conflating distrust with low trust, and strongly resonates with our experience in contentious natural resource settings.

The Trust/Distrust Matrix—A Compact Framework

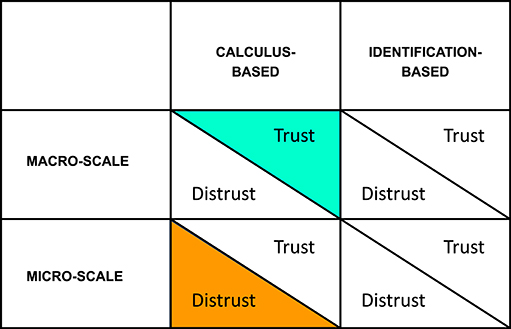

In an effort to create an integrative representation of the trust scholarship—particularly as it can inform natural resource management decision processes—we have developed the Trust/Distrust Matrix (TDM) presented in Figure 1. This is less an attempt to construct new theory than to weave together key aspects from existing theoretical constructs into a compact framework that resonates with our lived experience as the designers and facilitators of natural resource conflict management processes. The key elements of the framework are the trustor, the trustee/target of trust/distrust, the bases of trust/distrust and the scales at which trust/distrust can be assigned within a particular context. The matrix has two intersecting dimensions: one represented by the social scale at which trust is assigned to the trustee (or target) represented by the micro scale of individuals or groups and the macro scales of institutions, organizations and other societal systems; and the second represented by the bases for the trustor's judgments, either a calculus-based or identification-based. Within each of the cells of this matrix, there may be either trust or distrust judgments (as developed by the trustor facing the trustee/target(s) of trust). It should be noted that any particular trust/distrust judgment is time and context specific, recalling that trust judgments may vary over time and across domains of a given relationship.

In a heuristic sense, the TDM presents trust/distrust judgments as dependent variables that are functions of combining the judgment processes that occur within the trustor (the forms/bases of trust/distrust represented by the columns) and the attributes of the situation including the trustworthiness of the target(s) of trust/distrust (the scales/rows).

The structure of the TDM represents an adoption of a clear distinction between trust and distrust (Sitkin and Bijlsma-Frankema, 2018), as well as the conclusions of Lewicki and Tomlinson (2014) that relationships are multifaceted in terms of trust and distrust, where trust/distrust judgments tend to be either calculus-based or identification-based. It is possible to have strong identification-based reasons to feel like trusting someone, while one's track record of experience with them indicates that such trust would be misplaced. Further, it is possible to trust a person in some domains while distrusting in other domains of life—e.g., trusting a friend on money issues, while not trusting him/her to babysit. Accordingly, it should be noted that such multifaceted, multiplex relationships may lead to complex trust/distrust assessments (across several domains within the relationship) necessitating nuanced and thoughtful trust/distrust management approaches (as discussed in section Propositions Inferred From the Trust/Distrust Matrix) that simultaneously address several trust/distrust issues within a relationship. Such assessments and management approaches can be considered as working at a “fine-grained,” multifaceted analytical level below the scale of the individual, as several domains within a given relationship may need to be considered.

The social scale to which trust judgments can be assigned is coarsely depicted as a micro/macro dichotomy but also each of those is further sub-divisible. The appropriate division of scales is not fixed; one or more of the scales in Figure 1 might not be applicable in a given situation and other scales might be more so. The key point is that even as trust judgments are assigned to individuals, they ought to be characterized as actors who are socially or organizationally embedded in hierarchical systems, and therefore their behaviors are not truly independent but variously mandated, constrained, or at least informed by that embeddedness. Moving beyond the assignment of trust judgments to individuals, the notion of systems-based trust is closely attached to societal structures and institutions occurring at a larger scale than the individual, such as government institutions, bureaucracies, cultural institutions, education systems, private firms, NGO's etc. In our matrix, systems-based trust is represented by the macro-scale trust component—which is the scale at which abstract and impersonal systems dominate. When a person expresses trust in a certain organization this trust will in many cases be systems-based, shaped by the values, norms, rules and routines of this specific organization. The matrix provides a useful deconstruction of systems-based trust by identifying distinct calculus and identification bases for it. It is clearly possible to make calculus-based judgments regarding a system (the train has been late the last four times I used it) as well as identification-based judgments (as a member of the Green Party, I trust their analysis of proposed laws).

As indicated in the introductory example the target(s) of trust in a given situation may simultaneously cut across roles and scales—as Chris may be trusted as an individual (micro scale), while at the same time being distrusted as an agent/embodiment of the Parks Agency (macro scale) who is professionally bound to implement and/or explain Parks Agency decisions. In such situations it is possible, as depicted in the matrix, to consider Chris and the Parks Agency as two different (but closely interconnected) targets of trust/distrust represented by the micro and macro levels, respectively. As noted above, it is entirely possible to flexibly consider even more levels/scales within the idea and structure of the framework—such as the (local) Parks Agency is part of a Regional Office, which is part of the Federal Government, which both may be trusted/distrusted somewhat independently of the local Agency. As will be expanded upon below (section Propositions Inferred From the Trust/Distrust Matrix) the vertical differentiation of scales in the framework contributes substantially to its applicability in natural resource management situations/scenarios, which often involve hierarchical administrative structures, wherein decisions with local significance may be made at levels far removed from the locales being affected by them.

In summary, the Trust/Distrust Matrix offers an intellectual contribution that is more integrative than innovative. First, the matrix makes a clear distinction between trust and distrust and adopts the view that the presence of trust or distrust implies dramatically different expectations, social dynamics and outcomes. Second, it accommodates the need to comprehend trust across scales—that is, to distinguish between trustworthiness of an individual and the institution he or she represents. Third, the matrix distinguishes between two fundamentally different bases of trust/distrust judgments: a) a trust/distrust judgment merely based on a calculation of likelihood based on available information, such as past experiences, incentives/contractual requirements and expected gains/losses of future transactions; and b) a trust/distrust judgment that emerges from a stronger/weaker/absent foundation of shared identity, values and worldviews leading to mutual understanding, collective identity and appreciation for others' values, interests and needs2.

Extending the Trust/Distrust Matrix

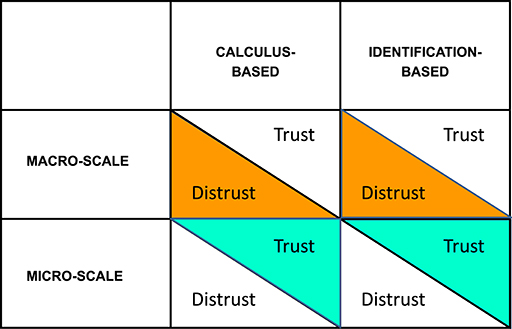

A core goal of the TDM is to readily represent multiple simultaneous trust/distrust judgments. Figures 2–5 shows four different combinations of cells in the matrix being “lit up” to display complex combinations of trust/distrust judgments3. Figure 2 coveys the sentiments expressed in the allegorical lead-in to this paper: “I trust Chris, our local parks manager, but I do not trust the Parks Agency at all” because the individual judgments toward Chris are trusting while the more macro scale judgments toward the Parks Agency are distrusting.

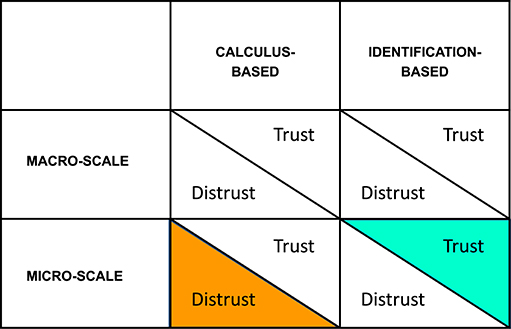

With more specific information about the bases for judgments, it is possible to represent simultaneous trust and distrust judgments about the same person (Figures 3, 4).

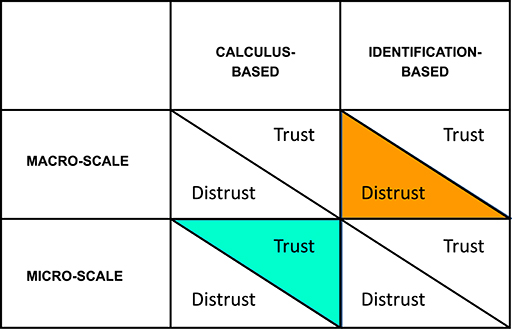

It is also possible to trust a macro organization more than any particular member or representative of it, as in Figure 5.

Our final remark on the use of the TDM is that it is intended to be a flexible tool to help structure and inform thinking, communication and analysis of a very complicated issue of great importance for natural resource management. In its compact form it may not immediately fit all situations or purposes. In some contexts, it may make sense to further develop the matrix—for example by adding more rows, in order to represent several participants in a given multi-party negotiation situation, or by adding more vertical layers or perhaps gradations in the levels of trust/distrust to enable a more situationally appropriate analysis.

Propositions Inferred from the Trust/Distrust Matrix

The process that gave rise to the TDM can be viewed as akin to Habermas' concept of rational reconstruction (1979) as a source of useful knowledge. We have attempted to interpret the realities of different forms of trust through the eyes of competent observers, and thereby reveal the deep structures embedded within those realities (i.e., scales, types of trust judgments, and the distinct difference between trust and distrust). If our interpretation has been on the mark, these deep structures should be manifest as surface structures that are far more visible and interactional. In other words, if our framework is valid, it should correspond to readily visible dynamics and inform practice—it should mirror our lived experience. To that end, we have prepared a set of propositions that articulate how structures interpreted through this trust framework could be manifest in practice. They all take departure from the core argument of this paper: that holding multiple trust judgments simultaneously is more typical than rare, and that it is entirely possible that they will be a mix of trust and distrust judgments (rather than uniformly positive or negative).

“Trust Building” Approaches May Often Be Misapplied to Situations That Really Need “Distrust Reduction”

When managers express a need to build trust among certain stakeholders, they may actually signal the existence of distrust. In such cases, the first step should focus on the assessment, management, and reduction of distrust, rather than (unrealistically) start building trust. Reducing a firmly-held distrust attitude between well-acquainted parties is a very different task than creating an initial trust judgment among people unfamiliar with one another, and indeed there is a body of literature that concludes that eliminating distrust may not be all that possible (Sitkin and Bijlsma-Frankema, 2018). In their study of trust and conflict in national park management in Benin, Idrissou et al. (2013) observe that “trust and distrust may appear simultaneously in a relationship and are considered important coexistent mechanisms for managing relationship complexity” (p. 67). Consequently, a clear distinction between trust and distrust may therefore improve the accuracy of the situation assessment and efficacy of management decisions.

Although not necessarily distrust, an unwillingness to trust may be the default condition when parties do not have any significant relational history. For example, when a new supervisor is selected to manage a national forest, the local community may withhold trust until the new manager demonstrates trustworthiness in some manner. This withholding of trust could become distrust if the new manager takes actions contrary to the values of the community.

Direct Attempts to Reduce Distrust May Be Less Successful Than Indirect Approaches

“Direct attempt” refers to any overt act intended to persuade a person (trustor) to revise a distrust judgment. From a trustor's point of view, a direct appeal to change one's mind about someone you distrust is as likely to engender suspicion and generate yet more distrust. It is more likely to bear fruit if you (as trustee) change your own behavior to provide valid reasons for others to change their judgments of your trustworthiness. Fortunately, you can control your own behavior (and the TDM can suggest where to start). In doing so, it seems evident that substantive responses (actual actions) are likely to be more effective than verbal responses (“cheap talk” ala Bottom et al., 2002). Further, it seems worthwhile to take the interactive and reflexive nature of trust/distrust development into account when trying to influence trust/distrust dynamics (Kim, 2018).

If trying to reduce someone's distrust judgments toward you or your organization, it could be worth trying to create a measure of cognitive dissonance regarding trust and distrust. So if there seems to be distrust based on value differences, it may be possible to reduce total distrust by clearly showing trustworthiness by being consistently reliable and predictable. In this way calculus-based trust may create openness to distrust reduction (and trust-building) even in other trust dimensions/scales. That cognitive dissonance creates the space within which one's own trust judgments become subject to revision (Festinger, 1962).

One form of indirectness involves the use of an impartial third party (Hocker and Wilmot, 2018). A mediator or facilitator can create a place and space in which parties can consider actions—both verbal and non-verbal—that impact trust and distrust. For example, Engel and Korf, writing in the FAO document Negotiation and Mediation Techniques for Natural Resource Management, explain that in “non-direct dealing” cultures, “mediation is a communal process that involves trusted leadership.” They add that “the indirect, triangular processes of a go-between are more desirable to save face, reduce threat, balance power, and equalize verbal and argumentative abilities” (2005, p. 57). In a similar vein, the United Nations Publication Natural Resources and Conflict: A Guide for Mediation Practitioners, proposes that:

Mediators vary on the degree of focus given to the substantive, procedural, and psychological aspects of the dispute. A substantive focus deals heavily with the interests of the parties, helping them assess their case, evaluate their proposals, identify criteria for consideration or even recommend the contents of an agreement. A procedural focus concerns the process-related aspects of the mediation, such as issues around communications, timing, sequencing or the administrative elements at play. A psychological focus prioritizes the relationship and trust between the parties. A given mediation process on natural resources will shift the focus as needed based on the dynamics of the negotiation (Jensen et al., 2015, p. 12).

The use of a third-party mediator/facilitator obviously raises the issue of whether or not they are trusted or distrusted; the former is not a forgone conclusion for intervenors any more that for anyone else.

Calculus-Based Trust Judgments May Be More Subject to Revision Than Are Identification-Based Trust Judgments

Because they are more evidence based, calculus-based trust judgments can be updated as a relationship unfolds and are therefore easier to revise than judgments based on values and identity which usually would be more stable and deeply embedded. Therefore, it may be an effective strategy to start out by trying to build calculus-based trust (e.g., by consistently being reliable, keep your word and fulfilling obligations). Provision of new evidence (e.g., changed behavior) that challenges existing calculus-based trust judgments (cognitive dissonance) could be combined with agreements, contracts and other incentives that encourage/secure the desired (trustworthy) behaviors. Several factors along those lines can act in concert to induce calculus-based trust judgment revision. From this basis it may be possible to eventually build identification-based trust in the longer term by building upon common values and identities (Sitkin and Bijlsma-Frankema, 2018).

To illustrate: One of the authors was involved in the development of a community-based collaborative group in a coastal community. The group wanted to work on various environment and natural resource management issues, including climate change adaptation. While the stakeholder community was diverse, many participants acknowledged that they were skeptical about the group, in part, because of limited trust. Consequently, the first task the group addressed was the construction of a “Collaboration Compact.” While not referring to trust explicitly, the Compact was designed to address factors that generate trust or distrust (e.g., transparency and inclusion) (Partnership for Coastal Watersheds, 2019). It served as an informal contract that specified what behaviors all participants were expected to exhibit and functioned as a temporary bridge that allowed people to make the first tentative steps toward working with one another until trust could more organically emerge.

Identification-Based Judgments Are Revised by Emphasizing Values Alignment/Compatibility, Shared History, and Commitment to Place

Identification-based trust judgments are more likely to evolve as a result of personal interaction, dialogue or insights during which the persons see new and more nuanced sides of one another, realizing common identities, shared values and human needs. That can be as simple as the realization that both parties actually feel attached to and love the landscapes over which they are disputing. Or it could be that they realize that they share values of care, commitment and team-spirit as volunteers in the local sports clubs (which is not directly related to the dispute, but nevertheless leads to increased identification and trust). On the negative side of the ledger, identification-based distrust can grow as parties realize they have different core values (Korsgaard, 2018).

Studies highlighted in the Appendix address the values-trust relationship. Davenport et al. (2007), for example, found that shared values contributed to trust whereas competing values constrained trust. Smith et al. (2013) discovered that stakeholders whose values aligned with public land managers were less likely to participate in public involvement activities than parties whose values were different, possibly because they trusted the land managers to make good management decisions.

Distrust May Motivate Engagement in Public Decision Processes More Than Does Trust

Several case-studies (e.g., Smith et al., 2013 referred to above) indicate that distrust can motivate engagement in public policy processes. Those who distrust either the individual planners or the broader agency/system has a strong incentive to participate in order to protect their interests. Those who trust the system and the personnel have less incentive to show up as they trust that their interests will be adequately considered and the outcome will be fair and balanced. In their discussion of the “trust ecology” framework, Stern and Baird (2015) assert that “positive trust, lack of trust, and distrust each function differently within a NRM [natural resource management] institution… For example, a general lack of trust may lead to apathy, hesitancy to become involved, or active information seeking. Explicit distrust may more commonly lead to selectively screening information to confirm one's beliefs” (p. 14).

Micro-Scale Judgments Are More Subject to Experience-Based Revision Than Are Macro (e.g., Systems/Societal) Scale Judgments

It seems likely that a person would more readily update their trust judgments about an individual based on directly observed trustworthy behavior, as opposed to revising their views toward larger systems/organizations. Social systems (institutions, organizations, agencies) tend to be heavier and rule-based, and therefore less flexible and slower to change. Any new evidence about macro-scale trustworthiness must therefore be stronger and perhaps based on new revised rules (or leadership) in order to generate enough new information to induce revision of judgment. There is evidence of this effect in the health care system where trust in one's own doctor can be paired with distrust in the general system (Peters and Bilton, 2018), which is analogous to the dynamic we have experienced repeatedly in the natural resources realm: “I like my local District Ranger, but the agency is inept/unprofessional/unconstitutional (or all of the above).”

This implies that managing trust/distrust at each scale could require an approach that was unique to that scale. If your analysis indicates that trust is lacking among individuals (rather than between individuals and your organization as such) it may call for targeted actions at the person-to-person level such as kitchen-table talks or personal involvement of employees in the local community in order to build relationships and trust. If the lack of trust (or distrust) is rooted in deep-seated features of the organization it may require changes of the system as such to prove trustworthy, such as revised rules, interpretations or practices—and may involve concerns about how to clearly display and carry out those changes so they will actually be acknowledged as trustworthy (e.g., in the form of changed leadership). As the two levels are inter-linked and embedded, a multi-level design strategy may be needed, echoing the perspectives of Daniels et al. (2012) regarding structured approaches to public policy negotiation and facilitation designs; as well as Peters and Bilton (2018) regarding trust in health care systems.

In a New or Temporary Relationship One May Not Have Much Evidence to Judge From—and Will Use/Seek What Is Available

“Swift trust” (Blomqvist and Cook, 2018) requires that typical trust formation processes be abbreviated. Available information may be selectively chosen, so certain aspects (calculus/identification-based, micro/macro) may weigh in disproportionally, perhaps leading to biased perceptions. Judging a person based on the values and political agendas of the organization he or she represents may lead to inaccurate judgment (prejudice) of this person's trustworthiness. By seeking information across scales and being aware of the different trust types it may be possible to get a more nuanced basis for making accurate trust and distrust judgments.

A recent study explored the extent to which someone is trusted because of their professional identity, specifically, as a scientist. Absent other factors, does the person's position as a scientist generate trust in an environmental management situation? In their examination of compliance with fisheries regulations in Brazil, Shirley and Gore discovered that “the most important factor influencing non-compliance rate among the population of professional fishermen in this study group in the Pantanal was trust in the scientists helping to define the rules” (2019). They concluded that “Increasing trust in scientists may be one mechanism for decreasing rates of non-compliance among our study population” (2019). This trust related to the scientist role exemplifies a form of swift trust; trust based on a factor like a person's profession or position. Trust/distrust judgments, decided quickly, can cut in either direction.

Process Design Choices and Trust/Distrust Development

Taking these propositions from the Trust/Distrust Matrix together, it becomes easier to see the extent to which a manager's/facilitator's process choices can influence the development of trust and distrust in a natural resource management situation. If a given case is characterized by identification-based distrust among key stakeholders at the institutional (macro) level, while there simultaneously exists some level of calculus-based trust at the person-to-person level (same pattern as Figure 4), a targeted process design could aim to further strengthen the existing trust at micro level by organizing relevant field trips, where participants from the key stakeholder organizations have the opportunity to develop personal bonds in a constructive setting. That could be a day in the field succeeded by a good meal and a beer at the bonfire, where participants can listen and talk to one another. If/when mutual understanding, empathy and trust has grown at the micro level a second step could entail mutual invitations among the key stakeholders to “visit each other's project sites” to gain insights about each other's organizations' aims and current challenges. Such targeted dialogue processes could at its best induce curious perspective taking amongst the stakeholders, leading to increased levels of mutual understanding, transparency and trust. Process designs should seek to eliminate polarized arguments where the parties end up attacking each other's organizational aims, values and jurisdiction, which in turn could exacerbate negative attitudes and attributions, increasing distrust, in-group out-group dynamics and spiraling conflict escalation. The example illustrates how the framework could support pragmatic incorporation of trust and distrust issues into the design and facilitation of dialogue processes in the vertically differentiated administrative landscapes of environmental conflict and natural resource management (Daniels et al., 2012).

Conclusion

Environmental decision making in the public sphere often involves a complex web of attitudes, trust judgments, and attributions. As facilitators of these processes we are often asked to “build trust,” between natural resource managers and stakeholders without any further explanation of what that means or how it might be achieved. Figuring out who will work with whom (and why) and who distrusts whom (and why) is a big part of charting a path forward. The trust/distrust framework presented in this paper frames that task to a considerable extent. A request for “trust building” may actually be a request for “distrust reduction.” Natural resource disputes are often long-lived threads of interaction that are woven into the history of a region, with much the same cast of characters engaged in repeated episodes. Ill will that emerged in the past among parties and organizations can become an anchor that is dragged into every new interaction. The Trust/Distrust Matrix makes it possible for facilitators to make a nuanced and relevant assessment of trust and distrust—without drowning in details. We have conveyed three main distinctions about trust via our compact framework: between trust and distrust judgments, between calculus- and identity-bases for those judgments, and between trust judgments assigned at the individual vs. more institutional scales. In some situations “management and mitigation of distrust” may represent a more accurate depiction of the challenge natural resource managers face, while in other situations it may be effective to develop trust building strategies that specifically are designed to build calculus-based trust at the institutional level, while in yet other situations it may make more sense to develop strategies that deliberately seeks to increase trust levels by focusing on individuals' common identity, shared values and hopes for the future. By providing a vocabulary and structure to illuminate such subtle differences, this compact framework should enable more precise articulation and targeted responses by natural resource managers to trust and distrust issues.

Author Contributions

JE has been the coordinating lead author and researcher throughout this project. Fundamentally, it has been a joint, integrated, long-term effort among JE, SD, and GW—to review, analyze, discuss, and clarify existing trust/distrust conceptions across scales and integrate them into a useful framework.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful for many fruitful interactions and learning moments with professionals, stakeholders and citizens we have met during our work as facilitators and researchers. We are equally grateful for the inspiration, critical perspectives and rigorous thinking on the topic from senior colleagues, as well as from the younger generation of scholars and students. In particular, we have appreciated inspiring discussions with former PhD students Cathy Brown Stummann, Mikaela Vasstrøm, Maya Pasgaard, Jennifer Bond, Riyong Kim Bakkegaard, Katinka Johansen and Raphael Kweyu, as well as critical reading and creative thinking provided by Jørn Emborg and Peter Daniels during the writing process. Finally, we wish to thank the editors and reviewers for reading our manuscript with great care for details and nuances while providing constructive comments to our work.

Footnotes

1. ^Understanding trust as a rational judgment choice includes consideration of game theory experiments wherein participants cooperate/compete in repeated interactions under various incentives structures and monitoring options (Deutsch, 1958; Lewis and Weigert, 1985; Ferrin et al., 2007). Understanding trust as a relational, affective- and emotion-based concept involves studying psychological constructs such as identity, orientations, attitudes, values, identification, emotions, affection and commitment (Jones and George, 1998; Burke and Stets, 1999; Weber and Carter, 2003; van Knippenberg, 2018). In most situations, trust is a blend of affective and more cognitive judgments (Lewis and Weigert, 1985; Möllering, 2001).

2. ^The issues of trustworthiness and antecedents to trust judgments has had their own foci in the general trust literature, but is largely beyond the scope of this article; for an entrée article see Baer and Colquitt (2018), for a classic see Mayer et al. (1995).

3. ^This visual simplification does not adequately convey the high/low (/absence) continuum of trust and distrust. However, this is where we start to illustrate the potential of the TDM – and it is not difficult to imagine various ways to capture and depict the continuum (colors, shading, font size etc.).

References

Andersson, L. M., and Bateman, T. S. (1997). Cynicism in the workplace: some causes and effects J. Organ. Behav. 18, 449–469.

Bachman, R., and Inkpen, A. C. (2011). Understanding institutional-based trust building processes in inter-organizational relationships. Organ. Stud. 32, 281–301. doi: 10.1177/0170840610397477

Bachmann, R. (2018). “Trust in institutions,” in The Routledge Companion to Trust, eds R. H. Searle, A. M. I. Nienaber, and S. B. Sitkin (New York, NY: Routledge), 218–227.

Baer, M. D., and Colquitt, J. A. (2018). “Why do people trust? moving toward a comprehensive consideration of the antecedents of trust,” in The Routledge Companion to Trust, eds R. H. Searle, A. -M. I. Nienaber, and S. B. Sitkin (New York, NY: Routledge), 163–182.

Bies, R. J., Barclay, L. J., Saldanha, M. F., Kay, A. A., and Tripp, T. M. (2018). “Trust and distrust. their interplay with forgiveness in organizations,” in The Routledge Companion to Trust, eds R. H. Searle, A. M. I. Nienaber, and S. B. Sitkin (New York, NY: Routledge), 302–325.

Bijlsma-Frankema, K. M., Sitkin, S. B., and Weibel, A. (2015). Distrust in the balance: the emergence and development of intergroup distrust in a court of law. Organ. Sci. 26, 1018–1039. doi: 10.1287/orsc.2015.0977

Blomqvist, K., and Cook, K. S. (2018). “Swift trust: State-of-the-art and future research directions,” in The Routledge Companion to Trust, eds R. H. Searle, A. M. I. Nienaber, and S. B. Sitkin (New York, NY: Routledge), 29–42.

Boon, S. D., and Holmes, J. G. (1991). “The dynamics of interpersonal trust: resolving uncertainty in the face of risk,” in Cooperation and Prosocial Behavior, eds R. A. Hinde and J. Groebel (Cambridge UK: Cambridge University Press), 190–211.

Bottom, W. P., Gibson, K., Daniels, S., and Murnigham, J. K. (2002). When talk is not cheap: substantive penance and expressions of intent in rebuilding cooperation. Organ. Sci. 13, 497–513. doi: 10.1287/orsc.13.5.497.7816

Burke, J. P., and Stets, J. E. (1999). Trust and commitment through self-verification. Soc. Psychol. Q. 62, 347–366. doi: 10.2307/2695833

Coleman, K., and Stern, M. J. (2018). Exploring the functions of different forms of trust in collaborative natural resource management. Soc. Nat. Resour. 31, 21–38. doi: 10.1080/08941920.2017.1364452

Cook, K. S., Hardin, R., and Levi, M. (2005). Cooperation Without Trust? Volume IX in the Russell Sage Foundation Series on Trust. New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation.

Daniels, S. E., Walker, G. B., and Emborg, J. (2012). The unifying negotiation framework: a model of policy discourse. Conflict Resol. Q. 30, 3–31. doi: 10.1002/crq.21045

Davenport, M. A., Leahy, J. E., Anderson, D. H., and Jakes, P. J. (2007). Building trust in natural resource management within local communities: a case study of the Midewinn National Tallgrass Prairie. Environ. Manage. 39, 353–368. doi: 10.1007/s00267-006-0016-1

Dean, J. S., Brandes, P., and Dharwadkar, R. (1998). Organizational cynicism. Acad. Manage. Rev. 23, 341–352. doi: 10.5465/amr.1998.533230

Deutsch, M. (1958). Trust and suspicion. J. Conflict Resol. 2, 265–279. doi: 10.1177/002200275800200401

Deutsch, M. (2000). “Cooperation and competition,” in The Handbook of Conflict Resolution, eds M. Deutsch, and P. T. Coleman (San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass), 21–40.

Deutsch, M. (2011). “Cooperation and competition,” in Conflict, Interdependence, and Justice, ed P. T. Coleman (New York, NY: Springer), 23–40.

Earle, T. C., and Cvetkovich, G. T. (1995). Social Trust: Toward a Cosmopolitan Society. Westport, CT: Praeger.

Engel, A., and Korf, B. (2005). Negotiation and Mediation Techniques for Natural Resource Management. Rome, Italy: Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO).

Ferrin, D. L., Bligh, M. C., and Kohles, J. C. (2007). Can I trust you to trust me? A theory of trust, monitoring, and cooperation in interpersonal and intergroup relationships. Group Organ. Manage. 32, 465–499. doi: 10.1177/1059601106293960

Fukuyama, F. (1995). Trust: The Social Virtues and the Creation of Prosperity. New York, NY: Free Press.

Gambetta, D., (ed.). (1988). Trust: Making and Breaking Cooperative Relations. New York, NY: Blackwell.

Giddens, A. (1991). Modernity and Self-identity. Cambridge: Polity Press; Cambridge University Press.

Gillespie, N., and Siebert, S. (2018). “Organizational trust repair,” in The Routledge Companion to Trust, eds R. H. Searle, A. M. I. Nienaber and S. B. Sitkin (New York: Routledge), 284–301.

Gregor, M., and Timmermann, J. (2012). Kant: Groundwork of the Metaphysics of Morals, 2nd Edn, Cambridge: Cambridge Texts in the History of Philosophy.

Hamm, J. A. (2017). Trust, trustworthiness, and motivation in the natural resource management context. Soc. Nat. Resour. 30, 919–933. doi: 10.1080/08941920.2016.1273419

Hamm, J. A., Hoffman, L., Tomkins, A. J., and Bornstein, B. H. (2016). On the influence of trust in predicting rural landowner cooperation with natural resource management institutions. J. Trust Res. 6, 37–62. doi: 10.1080/21515581.2015.1108202

Hamm, J. A., Trinkner, R., and Carr, J. D. (2017). Fair process, trust, and cooperation: moving toward an integrated framework of police legitimacy. Crim. Justice Behav. 44, 1183–1212. doi: 10.1177/0093854817710058

Hardin, R. (1991). “Trusting persons, trusting institutions,” in Strategy and Choice, ed R. J. Zeckhauser (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press), 185–210.

Heemskerk, M., Duijves, C., and Pinas, M. (2015). Interpersonal and institutional distrust as disabling factors in natural resources management: small-scale gold miners and the government in Suriname. Soc. Nat. Res. 28, 133–148. doi: 10.1080/08941920.2014.929769

Hocker, J. L., and Wilmot, W. W. (2018). Interpersonal Conflict, 10th Edn, New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

Idrissou, L., van Paasen, A., Aarts, N., Vodouhe, S., and Leeuwis, C. (2013). Trust and hidden conflict in participatory natural resource management: the case of the Pendjari National Park (PNP) in Benin. For. Policy Econ. 27, 65–74. doi: 10.1016/j.forpol.2012.11.005

Jensen, D., Brown, M., Grzybowski, A., and Kaye, J. L. (2015). Natural Resources and Conflict: A Guide for Mediation Practitioners. United Nations Department of Political Affairs and United Nations Environment Programme.

Jones, G. R., and George, J. M. (1998). The experience and evolution of trust: implications for cooperation and teamwork. Acad. Manage. Rev. 23, 531–546. doi: 10.5465/amr.1998.926625

Jones, N., Filos, E., Fates, E., and Dimitrakopoulos, P. G. (2015). Exploring perceptions on participatory management of NATURA 2000 forest sites in Greece. For. Policy Econ. 56, 1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.forpol.2015.03.010

Kahsay, G. A., and Bulte, E. (2019). Trust, regulation and participatory forest management: micro-level evidence on forest governance from Ethiopia. World Dev. 120, 118–132. doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2019.04.007

Kant, I. (1785). “Groundwork of the Metaphysics of Morals,” in Kant: Groundwork of the Metaphysics of Morals, Vol. 7, 2nd Edn, eds M. Gregor and J. Timmermann (Cambridge: Cambridge Texts in the History of Philosophy), 42–49.

Kim, P. H. (2018). “An interactive perspective on trust repair,” in The Routledge Companion to Trust, eds R. H.Searle, A. -M. I. Nienaber, and S. B. Sitkin (New York, NY: Routledge), 269–283.

Korsgaard, M. A. (2018). “Reciprocal trust: a self-reinforcing dynamic process,” in The Routledge Companion to Trust, eds R. H.Searle, A. M. I. Nienaber, and S. B. Sitkin (New York, NY: Routledge), 14–28.

Kramer, R. M. (1999). Trust and distrust in organizations: emerging perspectives, enduring questions. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 50, 569–598. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.50.1.569

Kramer, R. M., and Tyler, T. R. (1996). Trust in Organizations: Frontiers of Theory and Research. Los Angeles, CA: Sage Publications, Inc.

Lachapelle, P. R., and McCool, S. F. (2012). The role of trust in community wildland fire protection planning. Soc. Nat. Res. 25, 321–335. doi: 10.1080/08941920.2011.569855

Larson, D. W. (2004). “Distrust: prudent if not always wise,” in Distrust, ed R. Hardin (New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation), 34–59.

Levesque, V. R., Calhoun, A. J. K., Bell, K. P., and Johnson, T. R. (2017). Turning contention into collaboration: engaging power, trust and learning in collaborative networks. Soc. Nat. Res. 30, 245–260. doi: 10.1080/08941920.2016.1180726

Lewicki, R. J., and Bunker, B. B. (1996). “Developing and maintaining trust in work relationships,” in Trust in Organizations: Frontiers of Theory and Research, eds R. M. Kramer and T. R. Tyler (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage), 114–139.

Lewicki, R. J., Daniel, J., McAllister, D. J., and Bies, R. J. (1998). Trust and distrust: new relationships and realities. Acad. Manage. Rev. 23, 438–458. doi: 10.5465/amr.1998.926620

Lewicki, R. J., and Tomlinson, E. C. (2014). “Trust, trust development and trust repair,” in: The Handbook of Conflict Resolution. Theory and Practice, 3rd Edn, eds P. T. Coleman, M. Deutsch, and E. C. Marcus (San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass), 104–136.

Lewicki, R. J., Tomlinson, E. C., and Gillespie, N. (2006). Models of interpersonal trust development: theoretical approaches, empirical evidence, and future directions. J. Manage. 32, 991–1022. doi: 10.1177/0149206306294405

Lewicki, R. J., and Wiethoff, C. (2000). “Trust, trust development and trust repair,” in: The Handbook of Conflict Resolution. Theory and Practice, eds P. T. Coleman, M. Deutsch, and E. C. Marcus (San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass), 86–107.

Lewis, J. D., and Weigert, A. (1985). Trust as a social reality. Soc. Forces 63, 967–985. doi: 10.2307/2578601

Macey, J. R. (2002). Cynicism and trust in politics and constitutional theory. Cornell Law Rev. 87, 280–310.

Mayer, R. C., Davis, J. H., and Schoorman, F. D. (1995). An integrative model of organizational trust. Acad. Manage. Rev. 20, 709–734.

McAllister, D. J. (1995). Affect- and cognition-based trust as foundations for interpersonal cooperation in organizations. Acad. Manage. J. 38, 24–59. doi: 10.2307/256727

Menzel, S., Buchecker, M., and Schulz, T. (2013). Forming social capital—does participatory planning foster trust in institutions? J. Environ. Manage. 131, 351–362 doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2013.10.010

Misztal, B. A. (1996). Trust in Modern Societies: The Search for the Bases of Social Order. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Möllering, G. (2001). The nature of trust: from georg simmel to a theory of expectation, interpretation, and suspension. Sociology 35, 403–420. doi: 10.1017/S0038038501000190

Partnership for Coastal Watersheds (2019). The Partnership for Costal Watersheds Collaboration Compact. Available online at: https://www.partnershipforcoastalwatersheds.org/steering-committee-2/

Perry, E. E., Needham, M. D., and Cramer, L. A. (2017). Coastal resident trust, similarity, attitudes, and intentions regarding new marine reserves in Oregon. Soc. Nat. Res. 30, 315–330. doi: 10.1080/08941920.2016.1239150

Peters, S., and Bilton, D. (2018). “‘Right-touch' trust: thoughts on trust in healthcare,” in The Routledge Companion to Trust, eds R. H. Searle, A. M. I. Nienaber, and S. B. Sitkin (New York, NY: Routledge), 330–347.

Ross, V. L., Fielding, K. S., and Louis, W. R. (2014). Social trust, risk perceptions and public acceptance of recycled water: testing a social-psychological model. J. Environ. Manage. 137, 61–68. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2014.01.039

Rotter, J. B. (1967). A new scale for the measurement of inter-personal trust. J. Personality 35, 651–665. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.1967.tb01454.x

Rotter, J. B. (1971). Generalized expectancies for interpersonal trust. Am. Psychol. 26, 443–452. doi: 10.1037/h0031464

Rousseau, D. M., Sitkin, S. B., Burt, R. S., and Camerer, C. (1998). Introduction to special topic forum: Not so different after all: a cross-discipline view of trust. The Acad. Manage. Rev. 23, 393–404. doi: 10.5465/amr.1998.926617

Searle, R. H., Nienaber, A.-M. I., and Sitkin, S. B., (eds.). (2018). The Routledge Companion to Trust. New York, NY: Routledge.

Sharp, E. A., Thwaites, R., Curtis, A., and Millar, J. (2013). Trust and trustworthiness: conceptual distinctions and their implications for natural resources management. J. Environ. Plann. Manage. 56, 1246–1265. doi: 10.1080/09640568.2012.717052

Shindler, B., Olsen, C., McCaffrey, S., McFarlane, B., Christianson, A., McGee, T., et al. (2014). Research and Management Experience in Australia, Canada, and the United States. Corvallis, OR: A Joint Fire Science Program Research Publication; Oregon State University.

Shirley, E. A., and Gore, M. L. (2019). Trust in scientists and rates of noncompliance with a fisheries rule in the Brazilian Pantanal. PLoS ONE 14:e0207973. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0207973

Siegrist, M., Cvetkovich, G., and Roth, C. (2000). Salient value similarity, social trust, and risk/benefit perception. Risk Analysis 20, 353–362. doi: 10.1111/0272-4332.203034

Sitkin, S. B., and Bijlsma-Frankema, K. M. (2018). “Distrust,” in The Routledge Companion to Trust, eds R. H.Searle, A. M. I. Nienaber, and S. B. Sitkin (New York, NY: Routledge), 50–61.

Sitkin, S. B., and Roth, N. L. (1993). Explaining the limited effectiveness of legalistic “remedies” for trust/distrust. Organ. Sci. 4, 367–392. doi: 10.1287/orsc.4.3.367

Sitkin, S. B., and Stickel, D. (1996). “The road to hell: the dynamics of distrust in an era of quality,” in Trust in Organizations. Frontiers of Theory and Research, eds R. M. Kramer and T. R. Tyler (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications), 196–215.

Six, F. (2018). “Trust in public professionals and their professions,” in The Routledge Companion to Trust, eds R. H. Searle, A. M. I. Nienaber, and S. B. Sitkin (New York, NY: Routledge), 361–75.

Smith, J. W., Leahy, J. E., Anderson, D. H., and Davenport, M. A. (2013). Community-agency trust and public involvement in resource planning. Soc. Nat. Res. 26, 452–471. doi: 10.1080/08941920.2012.678465

Stern, M. J., and Baird, T. (2015). Trust ecology and the resilience of natural resource management institutions. Ecol. Soc. 20:14. doi: 10.5751/ES-07248-200214

Stern, M. J., and Coleman, K. J. (2015). The multidimensionality of trust: applications in collaborative natural resource management, Soc. Nat. Res. Int. J. 28, 117–132. doi: 10.1080/08941920.2014.945062

Thomas, C. W. (1998). Maintaining and restoring public trust in government agencies and their employees. Adm. Soc. 28, 166–193. doi: 10.1177/0095399798302003

van de Walle, S., and Six, F. (2014). Trust and distrust as distinct concepts: why studying distrust in institutions is important. J. Comp. Policy Anal. Res. Pract. 16, 158–174. doi: 10.1080/13876988.2013.785146

van Knippenberg, D. (2018). “Reconsidering affect-based trust: A new research agenda,” in The Routledge Companion to Trust, eds R. H. Searle, A. M. I.Nienaber, and S. B. Sitkin (New York, NY: Routledge), 3–13.

Weber, L. R., and Carter, A. I. (2003). The Social Construction of Trust. New York, NY: Kluwer Academic Press.

Winter, P. L., and Cvetkovich, G. T. (2010). Trust mediates conservation-related behaviors. Ecopsychology 2, 211–219. doi: 10.1089/eco.2010.0046

Wynveen, C., and Sutton, S. (2015). Engaging the public in climate change-related pro-environmental behaviors to protect coral reefs: the role of public trust in the management agency. Mar. Policy 53, 131–140. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2014.10.030

Yandle, T., Hajj, N., and Raciborski, R. (2011). The Goldilocks solution: exploring the relationship between trust and participation in resource management within the New Zealand rock lobster fishery. Policy Stud. J. 39, 631–658. doi: 10.1111/j.1541-0072.2011.00425.x

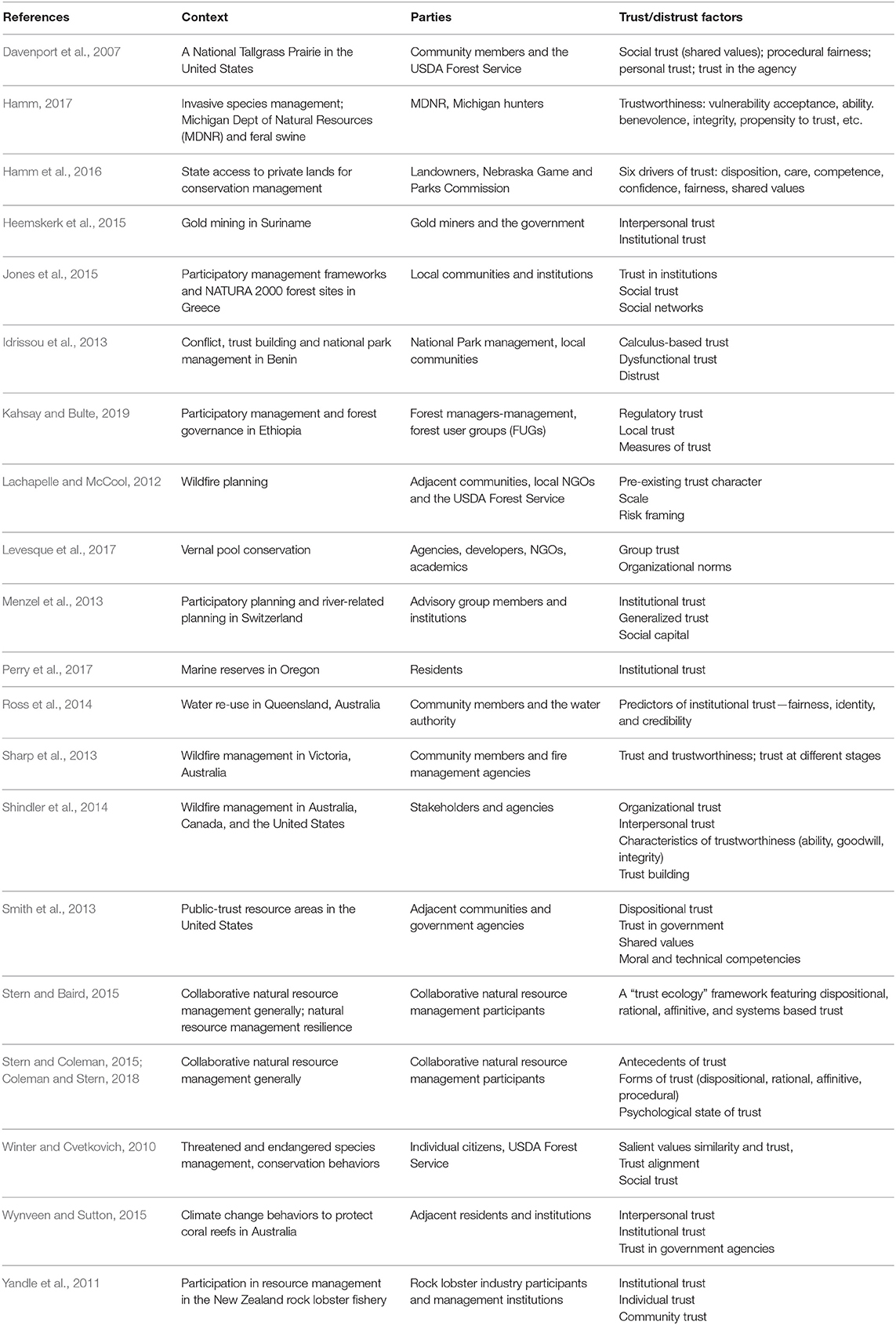

Appendix: Characterizations of Trust/Distrust in Natural Resource Management Scholarship

While the bulk of this paper attempts to develop an integrative representation of general trust/distrust concepts and academic approaches that resonates with our experience as process designers and facilitators, it is also useful to contextualize this effort within the trust literature arising within the natural resource management field. Consequently, as we have been developing our approach to trust and distrust, we have considered a range of publications that address trust/distrust in a natural resource management context. We highlight twenty of these articles in Table A1, selected to highlight the conceptual, geographic, methodological, and topical variety in the natural resource management related trust literature.

Across the breadth of this scholarship we do not see a sufficiently clear differentiation between trust and distrust and contend that more extensive attention to distrust is warranted. To be clear, distrust has received some attention, as the Table text illustrates. Heemskerk et al. (2015) address distrust explicitly in the case of small-scale gold mining in Suriname, although their distinction between trust and distrust is somewhat vague/taken-for-granted. Idrissou et al. (2013) contend that “Calculus-based trust needs thus to be counter balanced with deterrence-based trust, which enables the different parties to set the boundaries of the relationship and the punishments in case of trust breaking.” They explain that, if calculus-based trust is not constantly managed, distrust will arise among the parties (p. 73). In a recent study, Coleman and Stern (2018) explain how distrust exists as complementary to each form of trust (dispositional, rational, affinitive, procedural), thus receiving significant attention and discussion. However, overall most of the studies we have considered pay limited attention to distrust (and in some cases, none at all).

Many studies present a clear distinction between trust at the individual/interpersonal level and trust at the institutional/governmental level. A number of different types or categories of trust have been identified, of which many have a fair amount of overlap in content while different words and terms have been used to capture this content, e.g., personal, shared values, moral, integrity and affinitive based trust or systems-based, institutional, organizational and procedural based trust. The trust terminology has not yet converged in the natural resource management literature.

It should be equally clear that, in a natural resource management context, we must acknowledge the importance of trust across the full continuum of social organizations from the individual to the institutional/system level—and in this regard make a distinction between trust as it occurs at the individual (micro) level and trust as it occurs at institutional/systems (macro) level (as pinpointed by Bachman and Inkpen, 2011). While making a clear distinction between trust judgments of the micro level targets vs. trust judgments of the macro level targets, it should be noticed that the connections between the two levels are complex—e.g., in that the institutional/macro level forms part of the context for the trust development at the individual/micro level (Bachman and Inkpen, 2011).

Keywords: trust building, distrust management, trust judgments, trustworthiness, environmental conflict, collaboration, public involvement, facilitation process design

Citation: Emborg J, Daniels SE and Walker GB (2020) A Framework for Exploring Trust and Distrust in Natural Resource Management. Front. Commun. 5:13. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2020.00013

Received: 20 September 2019; Accepted: 12 February 2020;

Published: 17 April 2020.

Edited by:

Joseph A. Hamm, Michigan State University, United StatesReviewed by:

Lisa PytlikZillig, University of Nebraska, United StatesJames G. Cantrill, Northern Michigan University, United States

Copyright © 2020 Emborg, Daniels and Walker. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Jens Emborg, amVlJiN4MDAwNDA7aWZyby5rdS5kaw==

Jens Emborg

Jens Emborg Steven E. Daniels

Steven E. Daniels Gregg B. Walker

Gregg B. Walker