- School of Film and TV Arts, Xi'an Jiaotong-Liverpool University, Suzhou, China

In this essay I outline where I think the academic study of political communication should go—or rather, return to. First I discuss existing limitations and weaknesses of the current subfield of political communication, after which I highlight the work of political scientist Michael Parenti as an example of scholarship that I would like to see more of. In the Conclusion I summarize my main points and specify what I think should be priorities for scholars of political communication, as the world moves forward through these precarious times for democracy, justice, and even species survival.

Introduction

The mendacious and harmful presidency of Donald Trump and the limping Brexit saga exemplify worrying trends in the world today. Social inequality is on the rise; democracy on the decline. Progressing global warming, and the threat of nuclear war, both inadequately reported by the mainstream media, pose grave dangers to survival (Ellsberg, 2017). Support for Trump and Brexit might be interpreted as (misguided) resistance against the neoliberal policies of roughly the last 40 years, as forcefully argued by political economist Mark Blythe (in Meyer, 2019). In light of the breakdown of social democracy, which provided the framework within which many people in western countries could lead decent and productive lives in the decades after WWII, the question arises if, and if so how, scholars of political communication need to reconsider their research, including methodologies and ideological assumptions, whether they are recognized as such or not. In other words, Trump, and Brexit, however dangerous, might also provide a much-needed spur for scholars to consider reframing their research in ways that better and more directly align with the world's common interest.

In this essay I outline where I think the academic study of political communication should go—or rather, return to. First I discuss existing limitations and weaknesses of the current subfield of political communication, after which I highlight the work of political scientist Michael Parenti as an example of scholarship that I would like to see more of. In the Conclusion I summarize my main points and specify what I think should be priorities for scholars of political communication, as the world moves forward through these precarious times for democracy, justice, and even species survival.

Overcoming Political Communication's Weaknesses and Limitations

To grapple with pertinent limitations of the current subfield of Political Communication, one needs look no further than the recent outcry by its deacon, Lance W. Bennett, together with Barbara Pfetsch (2018). They propose nothing less than “reformatting the field.” This overhaul, they argue, should include “changing such core concepts as gatekeeping, framing, indexing, agenda-setting, and media effects in light of disrupted relations among media, publics, and democratic institutions” (Bennett and Pfetsch, 2018, p. 243). The authors assert that the “assumptions about broadly inclusive and relatively well-functioning public spheres in which communication from legitimate institutions passes through press organizations to affect the opinions and actions of citizens” as they supposedly existed in the glory days of North American and European social democracy, no longer can serve as foundations for the field in the current era. For,

many democracies today are experiencing varying forms of legitimacy crises, as center parties have become “hollowed out” by pressures related to globalization, social fragmentation, and loss of traditional social support. As a result, many societies face growing inequality, disruption of labor markets, immigration pressures, and citizen discontent across the political spectrum. While political institutions and press systems continue to operate, they often face serious problems engaging or representing citizens meaningfully, earning the term “post democracy”… (Bennett and Pfetsch, 2018, p. 243–244; also Entman and Usher, 2018).

In short, the field of Political Communication was built on standard liberal notions of the efficacy of western democracies in the post-WWII economic boom and social progress, and these highly dubious assumptions are alive and kicking. For instance, (Brants and Voltmer, 2011, p. 6–7) unreflectively celebrate commercial media by arguing that “the increasing competition in the media landscape has forced journalists to respond to the logic of the market and to take the needs and interests of their audiences more seriously into account when covering political issues.” Their view conforms to what James Curran labeled the liberal take on media history. They see commercial media as an “engine of freedom,” instead of a “system of control” (Curran, 2009, p. 10) Yet, of course, one might argue that such notions were always bankrupt to begin with or, at the minimum, severely circumscribed. Considering foreign news, for instance, Herring and Robinson acutely observed more than 15 years ago that

The standard liberal myth of the news media in the West—that it is independent of elite interests and provides the people with the information necessary to ensure that they can hold elites and in particular governments to democratic account—is rejected widely by academics who study the news media and US foreign policy… the most common and empirically substantiated perspective is that, with respect to coverage of US foreign policy, on balance, the US media serve elite interests and undermine democracy. The media do this by portraying the world in a way that tends to shape the perspective of those entering the political elite, generate public consent for or at least acquiescence to US foreign policy and make it difficult for the public to have access to information necessary to challenge the interests of the elite (Herring and Robinson, 2003, p. 554–555).

Or take one of the shining examples of the virtues, and admittedly huge benefits for citizens, of a social democracy: the Netherlands. Surely the country presents one of the strongest examples that scholars could possibly trot out when defending the notion of well-functioning public spheres, media and politics, certainly from approximately the 1960s to the 1980s. A convincing case can be made, though, that even in Dutch social democracy's glory days, its media served political and economic elites first, and the public a distant second at best. In fact, leading Dutch political communication scholars, including Brants, have themselves provided much evidence that underpins a radical instead of liberal take, in Curran's typology, on the Dutch media (Bergman, 2014c).

In the current era things have gone from bad to worse. The Trump presidency and Brexit serve as the obvious examples. An elaborate and much-publicized study demonstrates the bankruptcy of American politics (Gilens and Page, 2014). It shows that in Washington DC, money does the talking for corporations while the mass of people falter forlornly into a precarious future. To add an example from Europe, already at the start of the 21st century Dutch democracy could be characterized as, in the words of one sociologist, “almost undemocratic” (cited in De Rek, 2012). In such a context, Bennett and Pfetsch's call for a “fundamental rethinking” of Political Communication comes as an overdue but welcome intervention. They rightly warn that

… many democratic societies are suffering profound challenges related to the legitimacy of institutions, the incoherence of publics, the rise of disinformation, and the limited reach of once-authoritative information flows from the legacy media. These warning signs require a fundamental rethinking of the political communication and press/politics fields (Bennett and Pfetsch, 2018, p. 245).

If the current economic and political crisis in the West can serve as an opportunity for scholars of Political Communication to rethink their assumptions, then perhaps a small amount of good can be rescued from the world's current predicament. Couched in academic language, Bennett and Pfetsch launch a frontal assault on the bulk of the work done in Political Communications. Insightfully, they emphasize

the importance of normative theory aimed at revealing how communication may help shape conditions for more vibrant democracies. Indeed, bringing politics and democracy back into the forefront of the field are crucial to better understanding communication in fragmented public spheres, weak legacy media systems, and disrupted democracies (Bennett and Pfetsch, 2018, p. 250).

Bennett and Pfetsch take the position that public resistance has reached critical mass. Publics are on to the democracy ruse. Therefore, scholars of political communication can and should no longer blithely assume that the existing foundations of western democracies and media are benign, never mind the daily proclamations by many politicians and scholars to the contrary. As long as publics remained quiet it was possible, though not justified, to continue to proceed from such unquestioned but questionable assumptions. These days though, that position becomes less and less tenable. Not necessarily because of a sudden downturn in the quality of western democracies, I would argue, but because large segments of the publics simply no longer buy into or acquiesce to the liberal narrative. Either way, Bennett and Pfetsch clearly identify a central problem of Political Communication: a lack of critical consideration of core concepts, especially “democracy” (Bergman, 2014c). As a social-scientific research field, Political Communication tends to be weak on foundational critical thinking. It has adopted the standard definition of democracy as propagated by elites and made it the unquestioned basis of its enquiries. And it has tended to neglect the extent to which the news media function as channels for elite propaganda, in part because such a focus would lead to conclusions of a radical nature that scholars in the field, who are on the whole liberals, almost instinctively shy away from.

The problem is summed up well in the old computer-science adage: garbage in, garbage out. Such, then, is the state of Political Communication. Moving beyond its limitations and weaknesses is long overdue (see also Servaes and Anderson, 2016).

Michael Parenti's Media Criticism

Enter Parenti (1933). Before the current generation of scholars of Political Communication even began measuring aspects of media and politics based on flawed assumptions, the Yale-educated American political scientist published the first edition of Democracy for the Few (1974), arguing “that our government often represents the privileged few rather than the needy many, and […] elections and the activities of political parties are insufficient measures against the influences of corporate wealth” (Parenti, 1995). (2) Parenti was involved in founding the Caucus for a New Political Science in 1967, which aimed for “a fundamental redefinition of the purposes, categories, and politics of political science.” The Caucus wanted to dismantle “the myth of value-free and politically neutral social science” (“About Us” n.d.)1 Marginalized from academia in the 1970s, despite plenty of accolades for his work, Parenti continues to this day as a prolific, engaged public intellectual.

The Caucus goals are still as worthy as ever, and still not completely fulfilled: venturing into forbidden areas, research that is critical, comprehensible, and relevant to political struggle and history. It was unimaginable back in 1967 that almost a half-century later things in the profession would be pretty much the same. Today we have the same suffocating centrist ideology making false claim to objectivity. Today mainstream political scientists still debate the same tired questions about methodological rigor and paradigmatic shifts (Parenti in Boggs, 2012, p. 229).

Parenti has thus paid a heavy personal price for his continued and prolific engaged scholarship. “Financially it has been difficult at times, but I have survived so far.” (Interestingly, his son, Christian Parenti, also an engaged, radical scholar, has secured tenure).

… the only things I knew how to do in life were write and speak, so I continued doing them. What impelled me onward was the urge to seek truth amidst the lies and obfuscation of ruling interests. My efforts repeatedly drew me into forbidden terrain of a kind that does not lead to tenure. Deprived of a regular university position because of my activism and iconoclastic writings, I dedicated myself to trying to become a public intellectual (Parenti in Boggs, 2012, p. 228).

In the context of this essay, Parenti's published works on the media are most relevant (e.g., Parenti, 1986, 1992, 2002, 2010). What, then, can and should media scholars, including the political communication scholars urged by Bennett and Pfetsch to find new directions, take away from Parenti's work? First of all, Parenti adopts as his basic starting point a critical political economy of the media (Mosco, 1996; Wasko, 2014). As he wrote, “the important legitimating symbols of our culture are mediated through a social structure that is largely controlled by centralized, moneyed organizations. This is especially true of our information universe whose mass market is pretty much monopolized by corporate-owned media” (cited in Boggs, 2012, p. 234). His critical engagement with the political economy of the media as a starting point for his analyses separates Parenti from the bulk of political communication scholars. In other words, Parenti's assumptions are not unreflectively copied from liberal elites, but are grounded in a critical take on capitalism and the “capitalist state” as serving “to protect capitalism from the capitalists” (Parenti in Boggs, 2012, p. 234). Quite simply, their capitalist foundations explain a lot about media behavior, and Parenti understands and shows this, acknowledging an intellectual debt to media critics including Stuart Ewen (1986, p. 4), Ben Bagdikian (1986, p. 13), Antonio Gramsci (1986, p. 244), Herbert Schiller, Herbert Gans, Todd Gitlin, Alexander Cockburn, Robert Entman, Noam Chomsky, and Edward Herman (Parenti, 1986, p. xii-xiii). Some of these authors, including Gans and Entman, provide certain insight in the workings of the mass media, though they do not share Parenti's radical positions.

Before the appearance of a classic dissection of the America media in this tradition, Edward Herman and Noam Chomsky's Manufacturing Consent (1988), he already cited these authors approvingly:

In order to maintain a sense of self-respect and independence, many newspeople deny the realities of class power under which they manufacture the news. “The mass media are capitalist institutions,” notes Chomsky. “The fact that these institutions reflect the ideology of dominant economic interests is hardly surprising.” (Parenti, 1986, p. 58).

Indeed, since then Herman and Chomsky's propaganda model has withstood countless attacks, from the political center, left and the right, in large part because of the abundance and detail of the evidence that supports it (Herman and Chomsky, 1988). Other scholars have explained, defended, updated, adapted or otherwise shown the relevance of the model (Mullen, 2010; Mullen and Klaehn, 2010; McChesney, 2013; Bergman, 2014a,b, 2018; Srnicek, 2017; Zollmann, 2017; Klaehn et al., 2018; Pedro-Carañana et al., 2018; Zollmann et al., 2018). As a historian and a scholar who focuses on synthesizing research for a large audience, Parenti himself has made a relatively small contribution to providing more evidence, with his original analysis of ideological messages in movies and TV programs. His main strength, in short, is that, in contrast to Political Communication, he has always and unwaveringly put a critical political-economic take on the media, with its emphasis on their private ownership and the abundance of propaganda found in the news media, front, and center.

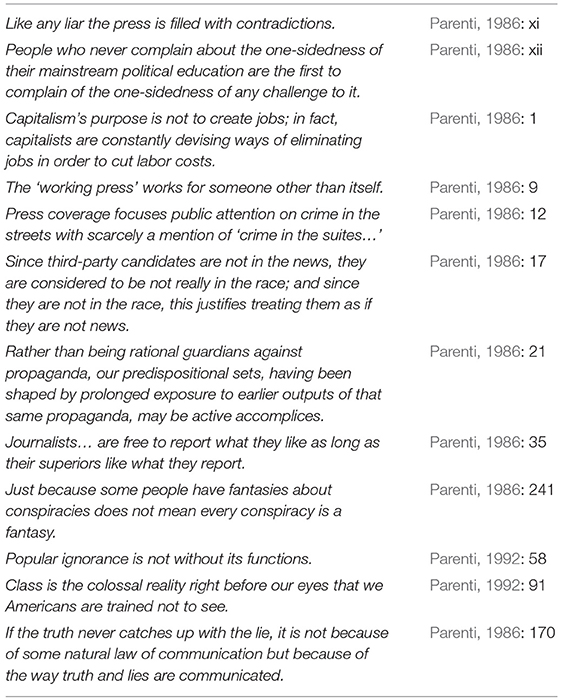

Furthermore, Parenti's writings are highly accessible to the interested layman. His major works on the media, Inventing Reality (Parenti, 1986) and Make-Believe Media (Parenti, 1992) constitute engaging reads, replete with memorable quotes and pithy phrases and sentences that to this day reveal important truths about media and society (Table 1). The only drawback to the accessibility, as far as I can tell, is that sometimes controversial information is presented without adequate referencing. Although the telling examples from the news and entertainment media are dated, these books constitute the best introduction to a radical take on the mainstream media that I know, with the possible exception of Ben Bagdikian's editions of the Media Monopoly (e.g., Bagdikian, 2004).

Another strong feature of Parenti's media criticism is the focus not just on media content, but on the hegemony-undermining information and views that usually fail to make the cut and that belie or put the mainstream media's actual content in a strikingly different light (e.g., Parenti, 1992, p. 55). Finally, by discussing not just characteristic media content but also the hegemony-challenging exceptions, Parenti strikes a fine balance between emphasizing the mainstreaming effect of the bulk of media content and acknowledging that media content is not ideologically monolithic (e.g., Parenti, 1992, p. 68).

Conclusion: Quo Vadis Political Communication?

Political Communication, then, would do well to heed Bennett and Pfetsch's call for a radical restructuring of the field. Parenti's work, regrettably hardly ever cited in the media and communications literature, can nonetheless serve as a constructive guideline for research while the world is moving forward through these uncertain and dangerous times. His embrace of a critical political-economic take, which acknowledges the importance of capitalism for understanding the media, and his strongly normative stance combined with his calling for media to truly serve the public interest, while addressing the public directly, all constitute features that would make political communication more trenchant in its critique and more socially relevant. It is noteworthy that, no doubt unwittingly, an outspoken report by a House of Commons committee on disinformation and fake news (House of Commons Digital Culture Media Sport Committee, 2019). (13) strikes a blow for a critical political-economic take on social media platforms by arguing that because of its dependence on advertising Facebook would need to be strictly regulated, so as to alleviate the “tension” between its business model and human rights. In fact, one might argue that the recent negative news on social media platforms and the public flak it has generated, illustrates the viability of a critical political-economic take on the media.

The contemporary “frontiers” in Political Communication that should be conquered entail a return to the values of radical scholarship that came up in the 1960s and have been honored by Parenti to the present day. The surge in radical scholarship back then was in part in response to American crimes in South-East Asia. Currently plenty of state and corporate crimes could and should form the impetus for a more critical look at western media and politics. Still following Parenti, scholarship in political communication should strive not just for academic rigor but also accessibility and societal relevance. It should advance critical media research with the aim to improve life for the mass of people.

Author Contributions

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and has approved it for publication.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Footnotes

References

Bennett, W. L., and Pfetsch, B. (2018). Rethinking political communication in a time of disrupted public spheres. J. Commun. 68, 243–253. doi: 10.1093/joc/jqx017

Bergman, T. (2014b). The Dutch Media Monopoly: A Political-Economic Analysis of the Crisis of Journalism in the Netherlands. Amsterdam: VU University Press.

Bergman, T. (2014c). Liberal or radical? Rethinking Dutch media history. Javnost-The Public 20, 93–108.

Bergman, T. (2018). “American television: manufacturing consumerism,” in The Propaganda Model Today: Filtering Perception and Awareness, eds J. Pedro-Carañana, D. Broudy, and J. Klaehn (London: University of Westminster Press), 159–172.

Boggs, C. (2012). Reflections on politics and academia: an interview with michael parenti. N. Polit. Sci. 34, 228–236. doi: 10.1080/07393148.2012.676401

Brants, K., and Voltmer, K. (2011). Political Communication in Postmodern Democracy: Challenging the Primacy of Politics. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Curran, J. P. (2009). “Narratives of media history revisited,” in Narrating Media History, ed B. Michael (London: Routledge), 1–21.

Ellsberg, D. (2017). The Doomsday Machine: Confessions of a Nuclear War Planner. New York, NY: Bloomsbury.

Entman, R., and Usher, N. (2018). Framing in a fractured democracy. J. Commun. 68, 298–308. doi: 10.1093/joc/jqx019

Gilens, M., and Page, B. I. (2014). Testing theories of american politics: elites, interest groups, and average citizens. Perspect. Polit. 12, 564–581. doi: 10.1017/S1537592714001595

Herman, E. S., and Chomsky, N. (1988). Manufacturing Consent: The Political Economy of the Mass Media. New York, NY: Pantheon.

Herring, E., and Robinson, P. (2003). Too polemical or too critical? Chomsky on the study of the US news media and US foreign policy. Rev. Int. Stud. 29, 553–568.

House of Commons Digital Culture Media Sport Committee. (2019). Disinformation and ‘Fake News’: Final Report. Available online at: https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm201719/cmselect/cmcumeds/1791/1791.pdf

Klaehn, J., Broudy, D., Fuchs, C., Godler, Y., Zollmann, F., Chomsky, N., et al. (2018). Media theory, public relevance and the propaganda model today. Media Theory 2,164–191.

McChesney, R. W. (2013). Digital Disconnect: How Capitalism is Turning the Internet Against Democracy. New York, NY: The New Press.

Meyer, H. (2019). (January 10). The Crisis of Globalisation: Interview With Mark Blyth. Available online at: https://www.socialeurope.eu/crisis-of-globalisation-mark-blyth

Mullen, A. (2010). Twenty years on: the second-order prediction of the herman-chomsky propaganda model. Media Cult. Soc. 32, 673–690. doi: 10.1177/0163443710367714

Mullen, A., and Klaehn, J. (2010). The propaganda model and sociology: understanding the media and society. Synaesthesia 1, 10–23.

Parenti, M. (1986). Inventing Reality: The Politics of the Mass Media. New York, NY: St. Martin's Press.

Parenti, M. (1992). Make-Believe Media: The Politics of Entertainment. New York, NY: St. Martin's Press.

Parenti, M. (2002). Monopoly Media Manipulation. Mediterran. Q. Spring, 13, 56–65. doi: 10.1215/10474552-13-2-56

Parenti, M. (2010). “Foreword,” in Hollywood Cinema and American Supremacy, eds Matthew A, and Power R (London: Pluto Press), vii–xiii.

Pedro-Carañana, J., Joan, B. D., and Klaehn, J. (eds.). (2018). The Propaganda Model Today: Filtering Perception and Awareness. London: University of Westminster Press.

Servaes, J., and Anderson, J. (2016). Introduction: hope or despair. Int. Commun. Gazette 78, 609–611. doi: 10.1177/1748048516655703

Srnicek, N. (2017). The challenges of platform capitalism: Understanding the logic of a new business model. Juncture 23, 254–257. doi: 10.1111/newe.12023

Wasko, J. (2014). “Understanding the critical political economy of the media,” in Communication Theories in a Multicultural World, eds Clifford, C, and Nordenstreng, K (New York, NY: Peter Lang), 60–82.

Zollmann, F. (2017). Bringing propaganda back into news media studies. Crit. Sociol. 45:089692051773113. doi: 10.1177/0896920517731134

Keywords: michael parenti, political communication, critical political economy, frontiers in political communication, social science

Citation: Bergman T (2019) “Old-New” Directions in Political Communication: Taking Michael Parenti's Media Criticism as a Guide. Front. Commun. 4:23. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2019.00023

Received: 22 February 2019; Accepted: 07 May 2019;

Published: 29 May 2019.

Edited by:

Piers Gregory Robinson, Independent Researcher, Berlin, GermanyReviewed by:

Jeffery Klaehn, Independent Researcher, Kitchener, ON, CanadaYigal Godler, University of Groningen, Netherlands

Copyright © 2019 Bergman. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Tabe Bergman, dGFiZS5iZXJnbWFuQHhqdGx1LmVkdS5jbg==

Tabe Bergman

Tabe Bergman