- 1Centre for Industrial Electronics, Mads Clausen Institute, University of Southern Denmark, Sønderborg, Denmark

- 2Department of Technology Entrepreneurship and Innovation, Mads Clausen Institute, University of Southern Denmark, Sønderborg, Denmark

Perceived charisma is an important success factor in professional life. However, women are worse than men in conveying physical charisma signals while at the same time having to perform better than men in order to be perceived equally charismatic. Speech prosody probably contains the most influential charisma signals. We have developed a system called “Pascal” that analyzes and assesses on objective acoustic grounds how well-speakers employ their prosodic charisma parameters. Pascal is used for charismatic-speech training in 12-weeks and 4-h courses on entrepreneurship and leadership. Comparing the prosodic-charisma scores for a total of 72 participants at the beginning and end of these two course types showed that female speakers start with significantly lower prosodic-charisma scores than male speakers. However, at the end of the 4-h course, female speakers can catch up with their male counterparts in terms of prosodic charisma. At the end of the 12-weeks courses, male speakers keep their lead, but female speakers are able to significantly reduce the prosodic charisma gap to male speakers. Since leadership and entrepreneurship are still male-dominated domains, our results can be seen as an encouragement for women to attend prosodic charisma training. Furthermore, these courses require a gender-specific design as we found men to improve mainly in F0 parameters and women in duration and phonation parameters.

Introduction

Charismatic speakers convey emotionally “contagious” (Fox Cabane, 2012, p. 145) verbal and non-verbal signals that make others invest their thoughts, actions, time or money into them (Antonakis et al., 2016). There seems to be a tangible cognitive reason for these charisma effects: Perceived charisma can inhibit areas of the brain that are associated with cognitive control of behavior and abstract reasoning (Schjødt et al., 2010). Acoustic cues alone predict perceived speaker charisma with an accuracy of 66–75% (Chen et al., 2014; Park et al., 2014), with prosodic features making the largest contribution to this prediction accuracy (cf. also Gregory and Gallagher, 2002). It was findings like these that recently boosted the interest of phoneticians in charismatic speech.

Phonetic studies have shown that acoustic-prosodic parameters are positively correlated with perceived speaker charisma (Strangert and Gustafson, 2008; Rosenberg and Hirschberg, 2009; Signorello et al., 2012; D'Errico et al., 2013; Niebuhr et al., 2016, 2018). For example, higher F0 levels, larger F0 ranges, and faster speaking rates make speakers sound more charismatic. The same also applies to the intensity level and standard deviation as well as to the frequency of emphatically stressed words. Disfluency count (incl. silent pauses), formant levels (F1–F3), prosodic-phrase durations, and spectral-slope voice-quality measures are negatively correlated with perceived speaker charisma.

Women sound less charismatic than men (Brands et al., 2015; Jokisch et al., 2018). This is true even if all other factors besides gender (incl. all prosodic parameters) are equal (Novák-Tót et al., 2017; Niebuhr et al., 2018). This is rarely the case in everyday life because men's speaking skills are promoted and valued more and perhaps even judged less critically by the society than those of women (Baxter, 1999; Sellnow and Treinen, 2004; Cameron, 2006).

Charisma also plays a big role in entrepreneurship; both with respect to the success of young companies in being innovative (Todorovic and Schlosser, 2007) and the success of individuals in founding a sustainable start-up business through legitimizing and fund-raising activities (Clark, 2008; Davis et al., 2017). The relevance of charisma in entrepreneurship and the finding that women sound less charismatic than men together resonate with what is known as the “gender gap” in entrepreneurship (Markussen and Røed, 2017). Besides the fact that many investors think of entrepreneurship as a male domain (Marlow, 2014) and, therefore, “screen out” women's business ideas while men's ideas are “screened in” (Kanze et al., 2018), women's oral presentations in front of investors sound less persuasive and are less likely to be funded and supported than those of men (Brooks et al., 2014).

A male advantage also exists in politics, although perhaps less strongly so than in entrepreneurship (Bystorm et al., 2001). Additionally, entrepreneurship represents a pillar of economic growth in today's innovation-driven economies (Audretsch et al., 2006), with female entrepreneurs making a disproportionate contribution to this growth (Gutierrez, 2017). Therefore, the question arises as to how this unfavorable gender gap in entrepreneurship can be closed. One answer is: with an effective way of turning female entrepreneurs into more charismatic speakers. The growing phonetic understanding of perceived speaker charisma has enabled researchers to develop computer-based systems for a precise parametric assessment and objective training of charismatic speech. Some systems are multi-modal, like Cicero (Batrinca et al., 2013) and MACH (Hoque et al., 2013). Our system focuses on the acoustic key parameters of prosody. It is called “Pascal”: Prosodic Analysis of Speaker Charisma—Assessment and Learning.

While users' learning success has already been documented for Cicero and MACH (Batrinca et al., 2013; Hoque et al., 2013), it still needs to be checked for Pascal. Moreover, neither system has been analyzed so far as to whether men or women benefit differently from using it. There is growing evidence that women are more sensitive to emotional and interactional prosodic elements than men, and that they also use these elements to a greater extent in speech production (Daly and Warren, 2001; Haan, 2002; Lausen and Schacht, 2018). So, if Pascal is able to shift a speaker's prosodic parameters in a more charismatic direction, it is possible that women benefit more from Pascal training than men, meaning that Pascal training would be a suitable means to reduce or close the “gender gap” in entrepreneurship. Specifically, the following questions are addressed: (1) Do women have a lower baseline (untrained) prosodic charisma level than men when they perform an entrepreneurial task like giving a short investor-oriented presentation of a business idea? (2) Is prosodic training able to shift a speaker's speech parameters in a more charismatic direction? (3) Do men and women benefit equally from such training or is there a gender specificity? (4) How are (2) and (3) affected by training time, i.e., in the comparison of a short crash course and a long intensive course?

Methods

Pascal and TPCS

Pascal is the patent-pending result of years of experimental-phonetic research in speech production and perception. It is based on the correlations listed in the Introduction between prosodic parameters and perceived speaker charisma, with one crucial innovation: the notion of an “overdose” (cf. also Rosenberg and Hirschberg, 2009). Perceived speaker charisma cannot be infinitely increased by a prosodic parameter shift in a given direction. Above a certain “overdose” threshold, the effect is reversed, making a further parameter shift increasingly detrimental for perceived speaker charisma. For example, a higher F0 level and a faster speaking rate make a speaker sound more charismatic, but when speakers get too high-pitched or too fast, the charisma level drops drastically. These “overdose” thresholds have been determined for each parameter in a large-scale series of perception experiments, also taking into account confounding variables like speaker gender. Furthermore, by playing off each parameter against the others in these perception experiments, we determined perceptual weights for the individual prosodic parameters (Berger et al., 2017). For example, after having found that F0 range is more relevant for perceived speaker charisma than F0 level, we developed multipliers for both F0 parameters that appropriately represent their relevance difference in Pascal's user feedback. Further details of Pascal are outlined in Niebuhr et al. (2017).

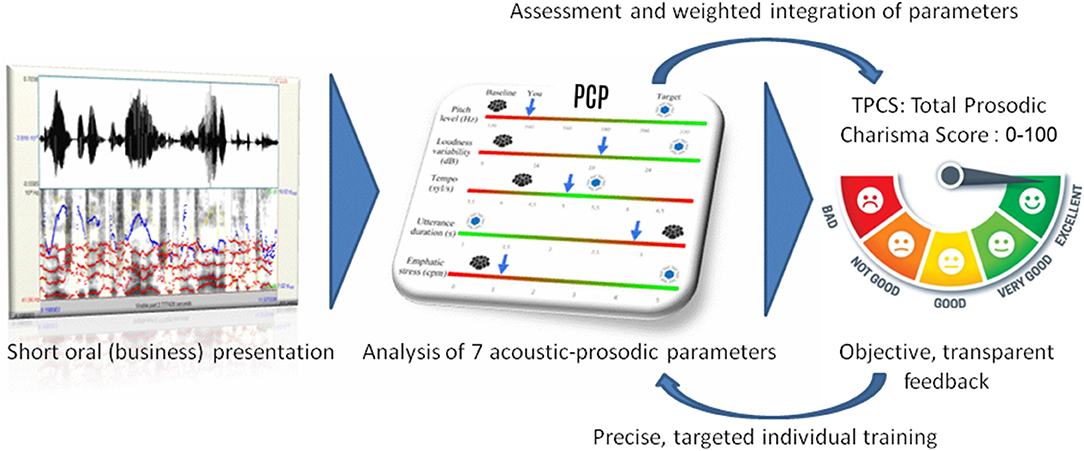

On this basis, any recorded speech sample can be uploaded to Pascal. The system then breaks down the sample into its relevant prosodic parameters, determines the mean parameter levels, and returns a twofold output: a Total Prosodic Charisma Score (TPCS), and a user-friendly Prosodic Charisma Profile (PCP), showing how the speaker performs on each prosodic parameter in relation to the overdose thresholds (red sections on the PCP scales), see Figure 1.

The TPCS is the dependent variable of the present paper. Using the TPCS as dependent variable does not mean that subjective charisma performances are compared. The TPCS is primarily rooted in acoustics. It translates acoustic-prosodic parameter values into a psychoacoustic measure that is calibrated through listener ratings. In this respect, TPCS is similar to the translation of F0 (Hz) into perceived pitch along the Mel scale or the translation of acoustic energy (dB) into perceived loudness along the Sone scale (Fastl and Zwicker, 2006). However, Mel and Sone are both scalar psychoacoustic translations of single acoustic parameters. Other parameters have to be constant when measuring Mel and Sone (e.g., 1 kHz, 1 s, pure tone etc.). In contrast, the TPCS integrates multiple acoustic parameters and offsets them against each other. In addition, the TPCS is, through its listener ratings, already normalized for the gender bias in perceived speaker charisma. Thus, a man and a woman both with a TPCS of, for example, “35” can be assumed to convey equally strong prosodic charisma signals. Of course, other speaker factors like foreign accent, body language, verbal rhetoric, physical attractiveness etc. can still make these (and any other) two speakers differently charismatic overall for listeners (e.g., Antonakis et al., 2011; Fox Cabane, 2012; Scherer et al., 2012). However, the present study is exclusively concerned with prosody and gender-specific differences in TPCS levels and improvements. These differences and improvements matter irrespective of all other possible sources of charisma that are not taken into account and controlled here. Moreover, these other factors are irrelevant here insofar as they have no influence on the acoustic TPCS measurements.

Charisma Training Courses

In entrepreneurship education, Pascal has been used regularly since 2017 in two different types of courses whose participants learn how to give successful business presentations. One course is a long intensive course that consists of 12 lectures of 90 min each over a whole semester. The other course is a short crash course of 4-h on a single day. Both courses are for entrepreneurs with an academic background in business engineering who plan to found a new start-up company or lead an innovation department within an existing company. The 12-weeks and 4-h courses obviously differ in the amount and detail of multi-modal rhetorical information provided to participants. However, at the heart of both courses is the successive improvement of prosodic charisma parameters through the reiterative use of Pascal. Participants upload their speech samples to the system, receive automatic PCP and TPCS feedback, interpret this feedback, and then try to produce a more charismatic speech. The type of speech was in all cases a short oral business presentation of 3–5 min, given in L2 English. The presentation was uploaded to and analyzed by Pascal as a whole.

Crucially, there is no systematically different treatment of men and women in the courses. Firstly, the primary feedback comes from the unbiased Pascal system itself. The human course instructor (first author) only adds explanations, clarifications, and guidance to the machine feedback. Secondly, the present paper is a post-hoc analysis of existing data. At the time of the courses, the course instructor did not yet know the gender-specific questions of the paper and, thus, could not influence participants consciously or subconsciously.

The 12-weeks and 4-h courses both start with the participants holding their business-idea presentation for the first time; and the two courses both end with a final matured presentation (of the same business idea) in which each participant can showcase what s/he has learned. Both presentations are fed into Pascal. The two resulting PCPs represent the baseline profile (BP) and the trained profile (TP). Their corresponding TPCSs are compared here. The 12-weeks and 4-h courses are entirely given in English, which includes the business-idea presentations as well as the expert supervision and Pascal's PCP and TPCS feedback interface.

Course Participants

The 12-weeks intensive course included 35 participants, 20 males, and 15 females. The 4-h crash course was carried out with 37 participants, 21 males and 16 females. All participants held, after about 15 years of education, an academic degree in business engineering or management. Moreover, all participants were post-graduate university students with part-time company employment and at least 1 year of working experience. The proficiency level of L2 English was at least B2, according to university-internal aptitude tests. There were no English native speakers in the courses.

Native-language background differed between the course participants. In the 12-weeks course, the majority of the 20 male speakers had German as their native language (35%), followed by Danish (25%), Slavic languages like Russian or Czech (20%), Arabic (15%), and Mandarin Chinese (5%). The percentages were similar for the 15 female speakers in that course (German 40%, Danish 20%, Slavic languages 20%, Arabic 6.7%, Mandarin Chinese 13.3%). In the 4-h course, the majority of speakers were again German (52.4% in the male and 56.3% in the female speaker sample). The percentages of Scandinavian speakers, Slavic speakers, Arabic speakers, and Mandarin Chinese speakers were all similarly low (between 19 and 6.3%), but in all cases larger than 0%. Chi-squared tests were carried out and showed by lack of significant differences that the native-language backgrounds were similarly distributed between the male and female speaker samples of each course. The same applied to speaker age. It ranged from 21 to 31 years in the 12-weeks course (ø = 23.6 years, sd = 2.6 years) and from 22 to 45 years in the 4-h course (ø = 28.8 years, sd = 3.2 years).

An ethics approval was not required for this empirical but non-experimental research as per institutional guidelines and national regulations. We adhered to the Danish Code of Conduct for Research Integrity and current data protection rules (GDPR). All our course participants gave informed written consent (cf. Declaration of Helsinki) that their data is recorded and can be used for scientific analysis in an entirely anonymous fashion.

Results

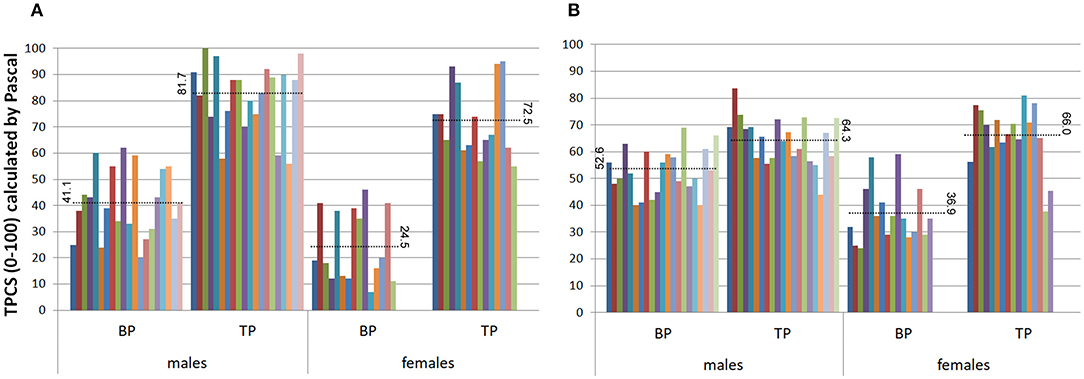

A three-way General Linear Mixed Model (GLMM) analysis was conducted for the TPCS data (dependent variable). Course Type (12 weeks vs. 4-h) and Gender (male vs. female) were between-subject factors, and Training (BP vs. TP) was a within-subject factor. Individual speaker was included as a covariate. A descriptive results summary of BP and TP values across the three factors is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. The TPCSs per participant, recording, and course type. Dotted lines show BP/TP means. (A) 12-week course, 20m+15f. (B) 4-hour course, 21m+16f.

The three-way GLMM yielded a significant main effect of Gender [F(1, 68) = 26.19, p < 0.001] as the acoustic-prosodic charisma scores (TP and BP) were on average significantly lower for female than for male speakers in our courses [ø males = 59.9 vs. ø females = 49.8; t(81, 61) = 2.84, p = 0.002]. There is also a significant main effect of Training [F(1, 68) = 268.62, p < 0.001] as TP scores were, across all speakers and both courses, higher than BP scores, thus indicating the participants' significant TPCS improvement from the beginning to the end of a course [øBPm&f = 40.0 vs. øTPm&f = 71.2; t(71) = −12.31, p < 0.001]. A significant interaction between Training and Gender [F(1, 68) = 9.92, p = 0.002] reflects that women's BP scores were a lot lower than men's BP scores (øBPm = 46.9 vs. øBPf = 30.7), but that this score difference became smaller (but was overall still significant) in the TP recordings (øTPm = 72.8 vs. øTPf = 69.1; t(40, 30) = 2.03, p = 0.04].

Course Type had no separate significant main effect. However, we found significant interactions between Course Type and Training [F(1, 68) = 36.61, p < 0.001] and Course Type and Gender [F(1, 68) = 7.55, p = 0.03]. The three-way interaction was not significant.

In order to examine the effect of Course Type in more detail, we split up the three-way GLMM and ran two additional separate two-way GLMMs, one on the 12-weeks intensive course and one on the 4-h crash course. The additional GLMMs replicated, separately for both courses, the beneficial effect of Training on TP scores [12-weeks: F(1, 66) = 189.53, p < 0.001; 4-h: F(1, 64) = 148.95, p < 0.001]. However, the size of this Training effect, i.e., the learning success in terms of the speakers' acoustic-prosodic charisma improvement, differed depending on Course Type. The improvement was larger in the 12-weeks intensive course than in the 4-h crash course, which caused the significant interaction Course Type*Training in the three-way GLMM.

The two additional GLMMs also replicated the significant interaction of Training and Gender for both courses [12-weeks: F(1, 66) = 16.04, p < 0.001; 4-h: F(1, 64) = 14.96, p < 0.001]. Again, these interactions differed depending on Course Type. In the 12-weeks course, the interaction reflects that women managed to significantly reduce men's TPCS lead from BP to TP recordings [øBPm = 41.1 vs. øBPf = 24.5; t(19, 14) = 3.67, p < 0.001; øTPm = 81.7 vs. øTPf = 72.5; t(19, 14) = 2.00, p = 0.027]. In the 4-h course, women were even able to turn their lower initial BP performance [øBPm = 52.6 vs. øBPf = 36.9; t(20, 15) = 4.42, p < 0.001] into a TP performance at eye level with men (øTPm = 64.3 vs. øTPf = 66.0; n.s.). It was for this reason that the interaction Course Type*Gender became significant and that the women's overall disadvantage over men in terms of TPCSs only showed up as a significant main effect in the GLMM on the 12-weeks course [F(1, 64) = 7.65, p = 0.008].

Discussion

Our results suggest positive answers to all questions raised in the Introduction. (1) Women have a lower baseline prosodic charisma level (BP) than men when they perform an entrepreneurial task like giving a short investor-oriented presentation of a business idea. This is true in the same way for both independent speaker samples of the 4-h and 12-weeks courses. Our supporting evidence on question (1) matches with the well-known “gender gap” in entrepreneurship, particularly since the speaking task was an entrepreneurial one and all analyzed speakers are in some way involved in entrepreneurial activities. However, the “gender gap” in entrepreneurship underlies a complex explanation (Markussen and Røed, 2017), and the prosodic charisma gap between prosodically untrained men and women can only be one component of its origin.

Furthermore, we found clear empirical evidence that (2) acoustically based prosody training is able to shift a speaker's prosodic parameters in a more charismatic direction and that, most importantly, (3) there is a gender specificity in the effect of (2). Women do benefit more from this prosody training than men. Compared to men, women's prosodic charisma improved faster so that they caught up with male-speaker performances after only 4-h of training. In combination with the finding that women started at lower BP-TPCS levels, this also means that women learn more during acoustically based prosody training. Men could only maintain a small TPCS lead after a longer period of training, as in the 12-weeks intensive course. Thus, (4) training time has an effect.

Note that decomposing the TPCS into its individual parameters revealed that the improvements of men and women rely partly on different parameters. Men improved mainly through higher F0 levels ranges and more emphatically-stressed words. Women's improvement was primarily based on shorter prosodic-phrase durations and better intensity and voice-quality measurements. This difference applies to the speaker samples of both courses. In combination with the lack of significant demographic differences between the male and female speakers within both courses, the findings suggest that prosodic charisma training needs to be gender-tailored in order to be effective across the full range of acoustic-prosodic parameters. However, our speaker sample is relatively small, and the sample sizes are not balanced across gender groups. Therefore, it is not clear how far these findings can be generalized, particularly beyond the analyzed speakers' age group and educational and socio-economic backgrounds as well as beyond other settings than short business presentations held in non-native English. These aspects of generalization are obvious starting points for follow-up studies. We are currently focusing on the aspect of native-language background.

Nevertheless, taken together, the present findings should be seen as a strong encouragement for female entrepreneurs to take part in a prosodic charisma training. It can make a significant contribution to counterbalance the stronger financial and technical support of male business ideas by male investors or decision makers.

Author Contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct and intellectual contribution to the work, and approved it for publication.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Refereces

Antonakis, J., Bastardoz, N., and Jacquart, P. (2016). Charisma: an ill-defined and ill-measured gift. Ann. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 3, 293–319. doi: 10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-041015-062305

Antonakis, J., Fenley, M., and Liechti, S. (2011). Can charisma be taught? Tests of two interventions. Acad. Manag. Learn. Educ. 10, 374–396. doi: 10.5465/amle.2010.0012

Audretsch, D. B., Keilbach, M. C., and Lehmann, E. (2006). Entrepreneurship and Economic Growth. Oxford, NY: Oxford University Press. doi: 10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195183511.001.0001

Batrinca, L., Stratou, G., Shapiro, A., Morency, L.-P., and Scherer, S. (2013). “Cicero - towards a multimodal virtual audience platform for public speaking training,” in Proceedings Intelligent Virtual Agents 2013 (Edinburgh).

Baxter, J. A. (1999). Teaching girls to speak out: the female voice in public contexts. Lang. Educ. 13, 81–98.

Berger, S., Niebuhr, O., and Peters, B. (2017). “Winning over an audience - a perception-based analysis of prosodic features of charismatic speech,” in Proceedings 43rd Annual Meeting of the German Acoustical Society (Kiel), 793–796.

Brands, R. A., Menges, J. I., and Kilduff, M. (2015). The leader-in-social-network schema: perceptions of network structure affect gendered attributions of charisma. Org. Sci. 26, 1210–1225. doi: 10.1287/orsc.2015.0965

Brooks, A. W., Huang, L., Kearney, S. W., and Murray, F. E. (2014). Investors prefer entrepreneurial ventures pitched by attractive men. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 111, 4427–4431. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1321202111

Bystorm, D. G., Robertson, T. A., and Banwart, M. C. (2001). Framing the fight - An analysis of media coverage of male and female candidates in primary races for Governor and U.S. Senate in 2000. Am. Behav. Sci. 44, 1999–2013. doi: 10.1177/00027640121958456

Cameron, D. (2006). “Theorising the female voice in public context,” in Speaking Out, ed J. Baxter (New York, NY: Palgrave), 3–20.

Chen, L., Feng, G., Joe, J., Leong, C. W., Kitchen, C., and Lee, C. M. (2014). “Towards automated assessment of public speaking skills using multimodal cues,” in Proceedings 16th International Conference on Multimodal Interaction (Istanbul).

Clark, C. (2008). The impact of entrepreneurs' oral ‘pitch’ presentation skills on business angels' initial screening investment decisions. Vent. Cap. 10:3, 257–279. doi: 10.1080/13691060802151945

Daly, N., and Warren, P. (2001). Pitching it differently in New Zealand english: speaker sex and intonation patterns. J. Sociol. 5, 85–96. doi: 10.1111/1467-9481.00139

Davis, B. C., Hmieleski, K. M., Webb, J. W., and Coombs, J. E. (2017). Funders' positive affective reactions to entrepreneurs' crowd-funding pitches: the influence of perceived product creativity and entrepreneurial passion. J. Bus Vent. 32, 90–106. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusvent.2016.10.006

D'Errico, F., Signorello, R., Demolin, D., and Poggi, I. (2013). “The perception of charisma from voice. A crosscultural study,” in Proceedings Humaine Association Conference on Affective Computing and Intelligent Interaction (Geneva).

Fastl, H., and Zwicker, E. (2006). Psychoacoustics - Facts and Models. Berlin; Heidelberg: Springer.

Fox Cabane, O. (2012). The Charisma Myth: How Anyone Can Master the Art and Science of Personal Magnetism. New York, NY: Penguin.

Gregory, S. W. Jr., and Gallagher, T. J. (2002). Spectral analysis of candidates' nonverbal vocal communication: predicting U.S. presidential election outcomes. Soc. Psychol. Q. 65, 298–308. doi: 10.2307/3090125

Gutierrez, C. M. (2017). Women Entrepreneurs Are Driving Economic Growth. Available online at: https://www.huffingtonpost.com/entry/women-entrepreneurs-are-driving-economic-growth_us_59f7c3dce4b04494283378f3

Hoque, M. E., Courgeon, M., Martin, J.-C., Mutlu, B., and Picard, R. W. (2013). “MACH: my automated conversation coach,” in Proceedings ACM International Joint Conference on Pervasive and Ubiquitous Computing (Zurich).

Jokisch, O., Iaroshenko, V., Maruschke, M., and Ding, H. (2018). “Influence of Age, gender and sample duration on the charisma assessment of German speakers,” in Proceedings 29th Conference on Electronic Speech Signal Process (Ulm).

Kanze, D., Huang, L., Conley, M. A., and Higgins, E. T. (2018). We ask men to win & women not to lose: closing the gender gap in startup funding. Acad. Manag. J. 61, 1–29. doi: 10.5465/amj.2016.1215

Lausen, A., and Schacht, A. (2018). Gender differences in the recognition of vocal emotions. Front. Psychol. 9:882. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00882

Markussen, S., and Røed, K. (2017). The gender gap in entrepreneurship – The role of peer effects. J. Econom. Behav. Organ. 134, 356–373. doi: 10.1016/j.jebo.2016.12.013

Marlow, S. (2014). Exploring future research agendas in the field of gender and entrepreneurship. Int. J. Gender Entrepr. 6, 102–120. doi: 10.1108/IJGE-01-2013-0003

Niebuhr, O., Skarnitzl, R., and Tylečková, L. (2018). “The acoustic fingerprint of a charismatic voice - Initial evidence from correlations between long-term spectral features and listener ratings,” in Proceedings 18th International Conference of Speech Prosody (Poznán). doi: 10.21437/SpeechProsody.2018-73

Niebuhr, O., Tegtmeier, S., and Brem, A. (2017). Advancing research and practice in entrepreneurship through speech analysis – from descriptive rhetorical terms to phonetically informed acoustic charisma metrics. J. Speech Sci. 6, 3–26.

Niebuhr, O., Voße, J., and Brem, A. (2016). What makes a charismatic speaker? A computer-based acoustic prosodic analysis of Steve Jobs tone of voice. Comput. Hum. Behav. 64, 366–382. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2016.06.059

Novák-Tót, E., Niebuhr, O., and Chen, A. (2017). “A gender bias in the acoustic-melodic features of charismatic speech?” in Proceedings Annual Conference of the International Speech Communication Association (Stockholm), 2248–2252. doi: 10.21437/Interspeech.2017-1349

Park, S., Shoemark, P., and Morency, L.-P. (2014). “Toward crowd-sourcing micro-level behavior annotations: the challenges of interface, training, and generalization,” in Proceedings of the 18th International Conference on Intelligent User Interfaces (Santa Monica, CA).

Rosenberg, A., and Hirschberg, J. (2009). Charisma perception from text and speech. Speech Commun. 51, 640–655. doi: 10.1016/j.specom.2008.11.001

Scherer, S., Layher, G., Kane, J., Neumann, H., and Campbell, N. (2012). “An audiovisual political speech analysis incorporating eye-tracking and perception data,” in Proceedings 8th International Conference on Language Resources and Evaluation (LREC'12) (Istanbul).

Schjødt, H., Stodkilde-Jorgensen, A. W., Geertz, T. E., and Lund, A. (2010). roepstorffthe power of charisma-perceived charisma inhibits the frontal executive network of believers in intercessory prayer social cognitive and affective. Neuroscience. 6, 119–127. doi: 10.1093/scan/nsq023

Sellnow, D. D., and Treinen, K. P. (2004). The role of gender in perceived speaker competence: an analysis of student peer critiques. Commun. Educ. 53, 286–296. doi: 10.1080/0363452042000265215

Signorello, R., D'Errico, F., Poggi, I., and Demolin, D. (2012). “How charisma is perceived from speech: a multidimensional approach. privacy, security, risk and trust (PASSAT),” in International Conference on Social Computing (SocialCom) (Amsterdam).

Strangert, E., and Gustafson, J. (2008). “What makes a good speaker? Subject ratings, acoustic measurements and perceptual evaluations,” in Proceedings of the 9th International Interspeech Conference (Brisbane), 1688–1691.

Keywords: prosody, charisma, entrepreneurship, rhetoric, sex differences, phonetics, speaker training, leadership

Citation: Niebuhr O, Tegtmeier S and Schweisfurth T (2019) Female Speakers Benefit More Than Male Speakers From Prosodic Charisma Training—A Before-After Analysis of 12-Weeks and 4-h Courses. Front. Commun. 4:12. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2019.00012

Received: 27 September 2018; Accepted: 13 March 2019;

Published: 03 April 2019.

Edited by:

Yury Y. Shtyrov, Aarhus University, DenmarkReviewed by:

Silke Paulmann, University of Essex, United KingdomFrancesca D'Errico, Roma Tre University, Italy

Copyright © 2019 Niebuhr, Tegtmeier and Schweisfurth. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Oliver Niebuhr, b2xuaUBzZHUuZGs=

Oliver Niebuhr

Oliver Niebuhr Silke Tegtmeier

Silke Tegtmeier Tim Schweisfurth2

Tim Schweisfurth2