- Communication Studies, Western Washington University, Bellingham, WA, United States

Yoga's immense popularity prompts concerns about the extent to which cultural appropriation has compromised its original philosophy. This research examines how yoga is constructed by mainstream news media discourse, with an emphasis on its religious vs. spiritual attributes. In doing so, I consider yoga as a commodity articulated through globalization, capitalism, and transculturation, the product of cultural appropriation (Rogers, 2006) and symbolic displacement (Wilson, 2012). Findings demonstrate that yoga's discursive detachment from religious origins facilitates its rearticulation as: a means to achieve physical, emotional, and mental wellbeing; a flexible experience amenable to other faiths and creeds; and an elite and exotic commodity embedded within overlapping consumerist structures of capitalism and spiritual renewal. These findings reflect the extent to which its appropriation complicates conceptualizations of cultural ownership and indigeneity that–unlike prior instances of appropriation–specifically commodify yoga for global consumption within contemporary neoliberal contexts.

A few years ago, attempts to implement a student yoga program in Southern California propelled the Encinitas Union School District into the national spotlight. Parents and children alike protested that the program violated their religious freedom and was a subtle move to promote a non-Christian religion (Brown, 2013, July 24). Despite the organizers' hasty efforts to minimize damage by tweaking pose sequences and avoiding Sanskrit terminology, a widely publicized lawsuit ensued. However, the presiding judge ultimately ruled in favor of the Jois Foundation, a nonprofit group funding this yoga fitness program (California school yoga program gets $1.4m grant, 2013, August 01).

This incident is not isolated, yet it is symptomatic of a prevailing sense of uneasiness and suspicion toward non-Western religions. The Encinitas verdict also prompts questions about the extent to which religion may be conflated with spirituality. Current estimates denote that one-fifth of U.S. Americans self-identify as religiously unaffiliated–colloquially referred to as “nones”–be they atheist, agnostic, or simply choose to have no particular religious affiliation (Pew Research Center, 2012, October 09). Follow-up responses suggest that disenchantment with organized religion, rituals, and materialism are the primary reasons why most Americans between the ages of 18 and 50 years choose to disassociate from the “religious” and embrace the “spiritual.” It is therefore not surprising that the practice of popular Asian meditative experiences, such as t'ai chi and yoga, is frequently characterized by an active attempt to diminish religious elements. Yoga, with its ostensibly religious roots, is widely promoted and disseminated in the United States as a vehicle to attain inner peace, bodily health, and spiritual fulfillment (Van der Veer, 2007). This trend has elicited harsh criticism from some parties who seek to keep yogic practice faithful to its original philosophy, such as the Hindu American Foundation's (HAF) Take Back Yoga campaign which is strongly opposed to “the delinking of yoga from its Hindu roots, [and] the erroneous idea that yoga is primarily a physical practice” (Hindu American Foundation, 2013). However, in what ways does this rearticulation constrain or enable the consumption and commodification of yoga and engage larger themes of symbolic displacement, cultural appropriation, and power imbalances within the mainstream cultural milieu?

Health communication research–although previously characterized by largely interventionist tendencies that underscored a praxis-oriented post-positivist paradigm–now encompasses a diverse range of theoretical perspectives, including interpretive, critical, and cultural frameworks (Dutta and Zoller, 2008). Calls to incorporate critical cultural perspectives in health communication (Lupton, 1994) are especially germane to the ethics of appropriating ancient systems of knowledge, including how these processes sustain existing global inequities between wealthy and developing communities. Yoga's appropriation offers a compelling opportunity to examine how the channels to physical and mental wellness can simultaneously constrain and facilitate the ways in which we encounter cultural difference and (sometimes opposing) systems of knowledge. This study addresses how yoga is discursively constructed by mainstream media discourse, with an emphasis on the manner in which this coverage negotiates its religious and spiritual elements. In doing so, I consider yoga as a commodity articulated within the overlapping frameworks of globalization and transculturation, the product of cultural appropriation (Rogers, 2006) and symbolic displacement (Wilson, 2012). Although other cultural products no doubt provide rich insight into how yoga is commodified, distributed, and consumed by contemporary global consumers, my intentional emphasis on mainstream media discourse reflects the sociohistorical legacy of careful information selection and validation among prominent news publications (e.g., newspapers, magazines, curated blogs, etc.) that typically capture the prevailing Zeitgeist. In this sense, the current study provides but one glimpse of how prominent media discourse–as constructed and shaped by dominant media institutions–contributes to how global audiences encounter and understand yoga. I begin by examining the role of cultural appropriation and symbolic displacement in the commodification of indigenous practices. I then consider the extent to which New Age Orientalist desire (Islam, 2012) in tandem with the discourses of wellbeing and spiritualism (Chaoul and Cohen, 2010; Huffer, 2011; Islam, 2012; Wilson, 2012) have rearticulated yoga for Western consumption. This theoretical backdrop facilitates an interpretive analysis of how yoga has “traveled” beyond India, and its accompanying discursive construction in mainstream media discourse.

Theoretical Framework

Indigenous Artifacts, Cultural Appropriation, and Symbolic Displacement

Cultural artifacts–namely, objects, customs, behaviors, and practices that are characteristic of a particular cultural group–may be considered indigenous to the extent that they encapsulate the particular beliefs and value systems of that group. Specifically, indigenous artifacts emphasize the prevailing modes of meaning-making–or frameworks of significance–that characterize a given ethnic community. In this sense, indigenous artifacts, such as yoga, may be deemed as culturally authentic in the sense that they embody the specific belief traditions, bodies of knowledge, and modes of interaction of a particular locality–in comparison to more transnational or global cultural products. the Indian subcontinent. However, Dirlik (2003) recommends conceptualizing the indigenous beyond its obvious contrast to the global. Rather, the indigenous derives significance from “place-consciousness,” (p. 15), and indigenous cultural practices are often imbued with shared common assumptions “that reaffirm the intimate and organic connectedness of culture, social existence, and the natural environment” (p. 22). In this sense, an indigenous cultural artifact closely reflects the ontological assumptions of a particular people in a particular place. Yoga, for instance, is derived in part from ancient Vedic scriptures and reflects particular elements of Hindu thought and philosophy, both of which are uniquely associated with the Indian subcontinent. Efforts to dislocate or erase these local components thus inevitably compromise the place-consciousness of an indigenous artifact, while prompting important questions about the mechanisms and imperialist agendas that may undergird cultural appropriation. While blanket descriptors, such as “Western” and “Eastern” elide the complex and multi-layered indigenous bodies of knowledge and technology underlying these ethnic artifacts, these opposing perspectives nevertheless convey the undeniable power asymmetry that warrants critical examination and consideration as appropriated artifacts are transferred from peripheral (marginal) to central (dominant) spaces.

Cultural appropriation involves “the use of a culture's symbols, artifacts, genres, rituals, or technologies by members of another culture” (Rogers, 2006, p. 474). This process goes beyond mere borrowing, and involves an active “taking” and “making one's own” (Rogers, 2006) of another culture's elements. Examples include South American tribal medicines that have been commodified and marketed by pharmaceutical corporations (Ziff and Rao, 1997), and the 1960s Tropicalia fad–a vibrant cultural movement that influenced music, visual art, film, and theater and intertwined elements of psychedelia, funk, and avant-garde genres–that drew heavily from a corresponding Brazilian art movement (Stam and Shoat, 2005). As our lives become increasingly permeated by intercultural diversity, globalization, and cosmopolitanism, the cultural appropriation of indigenous artifacts is evident in even the most mundane contexts–from fashion (Antony, 2010; Semati, 2010), to music (Stam and Shoat, 2005), and culinary experiences (Chand, 2007). It behooves us to pause and consider “the symmetry or asymmetry of power relations” (Rogers, 2006, p. 476) that accompany this process of cultural transfer as an artifact is uprooted from its traditional context and relocated to a new environment. To what extent does appropriation benefit indigenous cultural communities and validate indigenous frameworks of significance? The power dynamics of cultural appropriation typically sustain existing geopolitical imbalances that privilege Western modes of consumerism, signification, and capitalism. Simultaneously, ethnic and indigenous communities seldom reap the profits generated by the commodification and mass consumerism of their artifacts, which in turn sustains their continued marginalization and exploitation within the neoliberal context. Historically, the borrowing culture stands to gain considerably more than the original culture from this process, prompting concerns about the appropriation of ethnic artifacts from previously oppressed cultural groups (Ziff and Rao, 1997; Katrak, 2004; Stam and Shoat, 2005; Rogers, 2007). Furthermore, relocating and embedding a cultural artifact within an entirely different symbolic framework (i.e., set of cultural meanings and connotations) inevitably impacts how it is subsequently perceived and received. As Appadurai (1988) notes, “whenever there are discontinuities in the knowledge that accompanies the movement of commodities, problems involving authenticity and expertise enter the picture” [my emphasis] (p. 44). This explains, for instance, why henna tattoos, bindis, and other Indian ethnic accessories receive critical scrutiny when they appear on non-Indian bodies in ways that disconfirm their prescribed traditional application (Antony, 2010). Indeed, Appadurai (1988) observes that ethnic arts and “traditions of fabrication…change in response to commercial and aesthetic impositions or temptations from larger-scale, and sometimes far-away consumers” (p. 47). It is therefore not uncommon for ethnic cultural artifacts to undergo radical resignification based on the goals and expectations of a receiving culture. However, as cultural artifacts garner new and evolving interpretations and applications through the processes of transfer and appropriation, rearticulation simultaneously diminishes and proliferates an ethnic artifact's symbolic value. The politics of cultural appropriation–and especially when it pertains to indigenous artifacts–therefore demand critical attention to who benefits from this process of symbolic transfer and how.

For instance, Wilson (2012) considers the increasing global mobility of salsa–itself an amalgamation of multiple historical influences–and the way in which the ubiquity of this dance form complicates “the assumed homogeneity of terms, such as ‘authentic' and ‘indigenous”' (p. 207). Artifacts, such as these demonstrate the layers of complexity that accompany cultural appropriation and re-appropriation, challenging the very notion of a global/local binary. Although its global appropriation may still convey tired old stereotypes of the “spicy” and “sexy” Latin dancer, appropriation breeds symbolic mulitplicity:

Salsa, as a “local that moves,” fragments its own locality, or groundedness in Latin culture. Salsa does not become “less Latin” as it spreads around the world, but its Latin identity becomes displaced… various Salsa communities around the world…imagine their own “authentic and indigenous” Latin culture. This results in a multiplicity of Latin cultures as Salsa spreads to diverse places and is defined by new localities (p. 211).

For Wilson, cultural mobility spawns multiple levels of authenticity as dispersed communities adopt salsa and infuse it with their own indigenous modes of meaning-making. As a cultural artifact, therefore, the already complex constellation of meanings surrounding salsa as a dance form are further compounded and multiplied through its continued appropriation and global circulation. However, while this perspective may apply to artifacts that are not tied to any particular place or region, the case may be quite different for indigenous practices that are rooted in a definitive sense of place, as in the case of many religious traditions and rituals.

Hinduism, in particular, has a strained history of Western appropriation that is often characterized by misunderstanding and misperception. This may be the result of philosophical underpinnings and ontological tenets that bear little similarity to the (typically) Judeo-Christian frameworks that dominate Euro-American contexts (Stroud, 2003). In the absence of sufficient common ground, Hinduism and Vedic philosophy can intimidate and puzzle unfamiliar audiences (Blank, 1992). As a result, the discursive appropriation of indigenous Hindu artifacts into Western symbolic frameworks frequently entails replacing complex religious elements with more appealing and familiar signifiers (Islam, 2012). Ultimately, processes, such as these complicate issues of authenticity and expertise because the end result often bears little resemblance to the original indigenous artifact. For example, Ayurveda–a complex body of Vedic medical knowledge and healing practices dating back to 1,500 BC–postulates that the body and mind are complementary constituents and sources of disease (Islam, 2012). Traditional Ayurveda entails lengthy treatment plans that necessitate dietary modification, fitness, and naturopathy to restore balance to the body and mind. However, contemporary Ayurveda has been appropriated and branded within New Age Orientalist desire by the lucrative tourism industry as little more than a weekend spa package for affluent health consumers, who then need not make substantial lifestyle changes. Importantly, “the orientalist discourse of Ayurveda has been ‘deconstructed' [so that it] is no longer in dispute with conventional Western medicine” (Islam, 2012, p. 228), thus neutralizing and erasing the indigenous bodies of knowledge that have constructed Ayurveda, and simultaneously dislocating this quintessentially indigenous artifact from its south Indian roots.

In other instances, Hindu artifacts have been intentionally divested of religiosity to tout more familiar Western values, such as individual accomplishment and spirituality. Stroud (2003) offers a compelling analysis of how the Bhagavad Gita (a canonical Hindu sacred text) was translated into the novel The Legend of Bagger Vance, and subsequently into a popular Hollywood movie of the same name. The text's penetration deeper into western ideological systems was accompanied by a corresponding erosion of its religious emphasis. Whereas, the Bhagavad Gita emphasizes “dimunition of self and devotion to an all-encompassing deity,” The Legend of Bagger Vance valorizes individual initiative and goal accomplishment. Indeed, not only did the final Hollywood film represent a fundamental ontological shift from the deindividuated to the individuated self, but Vance himself (originally inspired by the Hindu deity Krishna) became “less of a god, and much more of a mysterious, comical guide” (p. 72). This rearticulation is more palatable to mainstream audiences who are uncomfortable with overt eastern religious messages.

Similarly, Huffer (2011) examines how contemporary transnational Indian gurus actively disavow religion through ambivalence to transcend the category of Hindu in favor of an ecumenical and non-denominational spirituality. They thus “distance themselves from the perceived orthodoxies of Hindu religiosity by using a decontextualized the olinguistic register to signify more egalitarian, democratic, inclusive, ecumenical, and universalistic impulses” (p. 374). This rhetorical shift rearticulates Hinduism-inspired doctrine in generalized and universalistic terms that emphasize benevolence and tolerance to enable the acceptance of an otherwise “foreign” faith. Yet it also prompts “often virulent contemporary debates in which Indian Hindu activists attempt to reclaim contemporary modalities (such as yoga) as Hindu” (p. 375), as in the case of the afore-mentioned HAF's Take Back Yoga campaign. However, Dirlik (2003) cautions against movements that seek to reverse and undo appropriation by exalting geographic origins, because an obsession with originating places may be little more than “a cover for parochialism and serve as an excuse for setting one place-based interest against another” (p. 26). Rather, he advocates “translocal or transplace interactions” as valuable foci for evolving and expanding the indigenous, while simultaneously retaining an awareness of global power relations. This observation is particularly relevant to the Western appropriation of yoga.

Appropriating and Rearticulating Yoga

Although some debate surrounds when exactly yoga originated ~2,000 years ago (Strauss, 2002; Gold, 2011), most scholars concur that yoga was derived from a foundational Indian text by Patanjali titled the Yoga Sutra–which forms the basis for this particular interpretation of yogic thought and philosophy, as well as subsequent analysis of cultural appropriation. The Sanskrit root of the word, “yuj,” means “to yoke or join together,” and its most common English translation is “union” (Strauss, 2004). Traditionally, this refers to the union of the individual self (microcosm) with the Absolute or Universal Self (macrocosm) (Chaoul and Cohen, 2010). Patanjali's classical yoga consists of an eight-stage process (ashtanga) which moves from bodily postures to a series of meditative states: (a) yama and (b) niyama advocate universal and personal rules for living a moral life; (c) asana and (d) pranayama outline body poses and breathing techniques for physical practice; and (e) pratyahara, (f) dharana, (g) dhyana, and (h) samadhi pertain to mental consciousness and the gradual removal of sensory input through focused attention, uninterrupted meditation, and perfect isolation and union with the Absolute (Strauss, 2002, 2004). In its broadest sense, classical yoga facilitates spiritual enlightenment (Chaoul and Cohen, 2010; Askegaard and Eckhardt, 2012) and the taming or “stilling of the modifications of the mind” (Gold, 2011). Yoga's inception was therefore deeply entrenched in Hindu spiritualism (Blank, 1992; McDaniel, 2012), and it originally developed as a predominantly male, high-caste, south Asian, ascetic, and spiritual set of beliefs and practices (Strauss, 2002). However, yoga has since evolved beyond this initial conceptualization.

A major discursive shift occurred during the Parliament of the World's Religions at the 1893 Chicago World's Fair when Swami Vivekananda, a dynamic and charismatic Hindu spiritual leader, first presented yoga to Western audiences (Strauss, 2002; Askegaard and Eckhardt, 2012). In this first level of symbolic displacement, Vivekananda rearticulated yoga as a physical, mental, and spiritual health commodity for Western consumption. He hoped to achieve an egalitarian exchange wherein he would bring India's spiritual wealth to the West and return with funds to help India's impoverished masses (Strauss, 2004). Claiming that Hinduism had “taught the world both tolerance and universal acceptance” (Van der Veer, 2007, p. 318), he resignified yoga as a metaphysics of mind-body unity that could be achieved through body exercises known as Hatha Yoga (Van der Veer, 2007). This discursive detachment from a concrete religious signifier still endures in contemporary mainstream perceptions of yoga.

As yoga's popularity increased, its health benefits attracted the attention of medical experts who are drawn to positive outcomes of asana and pranayama, such as reduced perceptions of stress, decreased blood pressure and heart rate, and improved self-efficacy (Khalsa et al., 2008; Chaoul and Cohen, 2010). Today yoga is utilized to treat anxiety and depression (Valanciute and Thampy, 2011), PTSD and combat stress (Yoga Warriors International, 2013), drug addiction and substance abuse (Khalsa et al., 2008), negative self-objectification (Impett et al., 2006), and stress (Chaoul and Cohen, 2010). Contemporary yoga is thus rearticulated within modern scientific discourses that reify logical claims, evidence, and explanatory frameworks for improved health (Askegaard and Eckhardt, 2012, p. 47). However, yoga's spiritual elements were eagerly embraced by a radically different demographic.

The youth revolution and hippie counterculture of the 1960s witnessed the popularity of yoga, particularly kundalini yoga (Valanciute and Thampy, 2011), and mainstream cultural icons like The Beatles enabled the commodification and promotion of Indian spirituality in the West (Van der Veer, 2007). As this discourse of spirituality permeated and displaced its religious origins, yoga became increasingly and inextricably connected with middle class aspirations and desires. Instruction tends to focus largely on instrumental asana practice, devoting negligible attention to the moral and ethical doctrine, both of which were integral components of traditional yogic practice and philosophy (Ketola, 2009). Concentration and meditation are typically directed toward spiritually ambiguous notions of a “higher power,” esoteric visualization (for example, colors and landscapes), and a nonjudgmental hyperawareness of body sensations (Impett et al., 2006). Symbolic resignification–namely, the process by which a cultural artifact is dislocated from prior modes of meaning-making and attached to new cultural frameworks and interpretations–occurs when Asian teachers settle and teach in Europe and America, and when yoga is taught by European and American teachers who have little knowledge of its history and original philosophy (Gold, 2011). Yoga is distanced from its philosophical origins and ontological foundations, and is re-signified in ways that make it compatible with prevailing systems of thought and action. Fueled by global capitalism, this trend has culminated in diversification and the availability of various yoga experiences, the proliferation of yoga accessories, and expensive yoga retreats and workshops (Bourne, 2010).

The final turn of this wheel takes us, strangely enough, back to India, where yoga is enjoying a resurgence in popularity as Western appropriation is “re-exported into India, yoga's traditional home” (Bourne, 2010, p. 11). Global capitalism has ushered yoga's therapeutic perspective into urban middle class Indian circles (Van der Veer, 2007), provoking mixed reactions among Hindu nationalists, who welcome the renewed emphasis on Hinduism and its traditions but are wary about the “new-fangled urban religiosity” (p. 326) that defines contemporary yoga experiences.

Yoga's continued appropriation thus fragments and displaces its original indigenous symbolism, resulting in a hybrid multiplicity of experiences (Wilson, 2012). However, Bhabha (1994) advocates “distinguishing between the semblance and similitude of symbols across diverse cultural experiences…and the social specificity of each of these productions of meaning as they circulate as signs within specific contextual locations and social systems of value” (p. 172). Accordingly, this research considers how yoga–as an appropriated and re-appropriated indigenous cultural artifact–has been resignified by mainstream media for contemporary global audiences. In doing so, I aim to investigate the social specificities of this symbolic rearticulation, with particular attention to processes of commodification, mass consumerism, and social value within the neoliberal context. I also examine the extent to which this process engages or divests this appropriated Indian artifact of its religious elements (Stroud, 2003; Huffer, 2011). My research agenda is:

RQ1: How do mainstream media texts discursively construct yoga?

RQ2: How does this process in turn negotiate yoga's religious vs. spiritual elements to enable consumption and commodification?

Method

Data

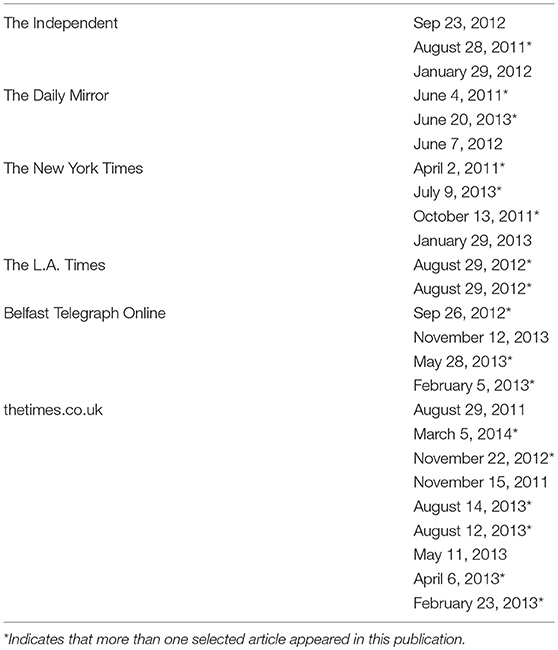

As mentioned, this analysis considers only mainstream media articles and reports. Although fictional (movies and novels) and other non-fiction media texts (biographies, autobiographies, documentaries, instructional videos, blogs, websites, etc.) are doubtless valuable avenues for discourse analysis, I chose to limit my attention specifically to mainstream newspapers (traditional and online). This allowed for a focus on how mass audiences discursively encounter yoga in the mundane and everyday context of a news publication covering global and local events. I began by entering the keyword “yoga” with (successively by turns) “religion,” “religious,” “spiritual,” “spirituality,” and “hindu” in the LexisNexis Academic database to locate news reports and articles containing combinations of these words. My data encompassed major newspapers (primarily U.S. and British press) published within 1 year of the Encinitas incident (January 01, 2013–March 10, 2014) to capture press responses to and following the school yoga program controversy. Letters to the editor, and book and film reviews were not included in my analysis–the former because this content is not created by news staff, and the latter because it reflects commentary on a published media artifact and its scope is therefore restricted by the structure and content of the original text. Blogs were only included if they were created by an existing news writer who was affiliated with the official news publication. Following the elimination of duplicated search results (e.g., newspaper articles published both online and in print), my final dataset consisted of 47 newspaper reports, 44 magazine articles, and 28 online articles that contained the specified keywords (see Table 1), yielding a total of ~153 pages of single-spaced 12-point font text.

Analysis

I employed discourse analysis to interrogate the manner in which yoga is aligned with religious and spiritual attributes. Specifically, I focused on the extent to which master signifiers (also known as nodal points) are constructed through clusters or links with other signifiers in chains of equivalence (Jorgensen and Phillips, 2002). A master signifier is a casing or shell that can be filled by other signifiers, and thus derives its meaning from the emergent relational identity of these other signifiers. Jorgensen and Phillips (2002) provide the example of how hegemonic American discourse constructs the master signifier “man” by equating it with other signifiers, such as “strength,” “football,” and “reason.” The nodal center “man” thus derives its identity from a cluster of surrounding signifiers, and is simultaneously differentiated from contrasting master signifiers (e.g., “woman”) and their respective signifier constellations. Meaning is therefore socially and politically “constituted through chains of equivalence where signs are sorted and linked together in chains [and] in opposition to other chains which thus define how the subject is, and how it is not” (p. 43). As a master signifier, yoga has been actively detached from some satellite signifiers that characterize its indigenous philosophies and origins, and derives new cultural significance as it becomes affixed to others through symbolic displacement. I therefore sought to uncover the cluster of signifiers that surround yoga as it is discursively constructed by mainstream media. This in turn allowed me to compare the emerging discursive framework within oppositional chains (for instance, “yoga” → “religion” vs. “yoga” → “spirituality”) and thus determine the direction of symbolic displacement.

The resulting chains of equivalence materialized between the master signifier “yoga” and three distinct yet interconnected signifier clusters. Specifically, yoga was rearticulated as: a means to achieve physical, emotional, and mental wellbeing; a flexible and ambiguous spirituality that was amenable to other religious creeds; and an elite exotic commodity embedded within the overlapping frameworks of consumerism and spiritual renewal. Furthermore, mainstream media discourse frequently pivoted back and forth between these satellite signifiers as yoga discursively emerged at their synergistic and relational confluence. I now reveal the intricacies of these individual signifiers.

Findings

Mind-Body Wellness

This category touted the physical, mental, and emotional benefits that yoga afforded its practitioners, reflecting the persistence of the scientific paradigm–factual claims, evidence, and logical explanations–to underscore yoga's utility as a panacea for everyday illness and fatigue (Askegaard and Eckhardt, 2012). News writers emphasized the physiological, cardiovascular, respiratory, and neurocognitive advantages of regular practice, citing examples of how yoga “reduces chronic pain, such as lower back pain, arthritis and headaches, blood pressure, improves heart and breathing rates, alleviates insomnia,” (Toribio, 2014, March 04) and also “improves a range of conditions, including the nerve condition carpal tunnel syndrome, and asthma” (O'Reilly, 2008, January 08). One article labeled yoga “a form of exercise, which originated in India,” [my emphasis] citing an instructor who advised that only through regular yoga “will you reap the rewards of a fitter, more toned body and a calmer and more centered mind.” (Fontyn, 2010, December 24). Indeed, some media commentary suggested that “athletic, fast-moving styles, such as Vinyasa and Ashtanga (sometimes called power yoga)” were useful to men, who “use yoga as complementary cross-training to loosen hamstrings winched tight from running” and “unlock chests and shoulders stiffened by bench-pressing” (Capouya, 2003, June 16). Asana practice is thus inextricably allied with the discourse of athleticism and physical vitality, particularly with regard to toning and regulating the masculine body. This pattern extended to provide a rational explanation for mental wellness, as a neurocognitive expert noted that this routine prompted the “release of serotonin from what can be demanding exercise” (Burke, 2007, June 27).

Some experts situated the physiological benefits of chanting (which adds a vocal dimension to asana practice) within the scientific register, “Chanting yoga is based on the principle of vibrational medicine and involves the primordial sound vibration of mantras…[This is] a sublime process for deep relaxation, achieving greater concentration and transformation of consciousness to a higher level” (Gautam, 2007, December 07). Similarly, another instructor claimed that “We chant ‘om' because humming calms the vagus nerve [in the cranium] and clears the sinuses” (Fontyn, 2010, December 24). Perspectives, such as these erase the religious foundations underlying the act of chanting, instead lodging yoga within the discourse of modern science and recuperative medicine to expound its utility in healing the human body.

Simultaneously, this category revealed the enduring influence of Vivekananda's pivotal rearticulation of yoga as the “metaphysics of mind-body unity” (Van der Veer, 2007), by also accentuating the emotional wellbeing resulting from sustained and contemplative asana practice. These observations typically referred to yoga as “a pushback against hectic lifestyles,” (Rajghatta, 2013, June 23), everyday stressors, and fast-paced careers to restore sagging spirits and provide spiritual upliftment: “Ultimately, yoga is gaining popularity because it feels good. Or maybe better than good. “I leave feeling like I'm on drugs,” one student says. Others are finding a different kind of high: spiritual elevation” (Talbot and Schwartz, 1992, February 03). Yoga therefore becomes a transcendental tool to attain enhanced awareness, although these practitioners liken the experience to the mind-altering haze of a drug-induced high rather than religious ecstasy. Elsewhere, a combination of the Kama Sutra, tantra, and couples yoga are recommended as ways to heighten emotional bonding and “understand sex in spiritual terms” (Rossi, 2006, October 02). Yoga thus offers the opportunity of temporary escapism, to transcend the trappings of this mortal coil. However, the ultimate purpose is to appreciate and reconnect with one's own body, as in the case of a reporter who visited yoga class that “intentionally recognizes and honors the subtle differences in a woman's body, mind and heart” (Heckel, 2013, June 19):

The class is arranged in a circle…weaving together yoga, spirituality and relationships. Women are hard-wired for connection… When women hang out with other women, their stress hormones drop and they produce more oxytocin, so you physically feel happier. Instead of trying to get up and out of our bodies, like many traditional yoga practices do, it's more of an embodiment… coming into full connection with all of life, instead of trying to reach some idealized state of perfection [my emphasis].

Yoga thus becomes a cohesive mechanism to celebrate shared womanhood and help women better connect with their material existence. In all these instances, the ultimate goal of yoga practice is discursively shifted to the self (one's own body and mind), rather than self-diminishment, ego transcendence, and union with the divine (Strauss, 2002, 2004). Yoga practice eventually hones and refines the practitioner's ego to achieve a recommitment to the material and physical plane, and thus fundamentally displaces the traditional philosophy.

An Ambiguous and Flexible Spirituality: Erasing and “Stretching” Hinduism

A second cluster materialized around intentionally erasing and replacing yoga's Hindu elements with those of other religions. At this point, I wish to clarify that my analysis draws largely on a Patanjali-centered interpretation of yoga, and reflects the tenets and precepts of this foundational yoga text. Here, yoga served as a flexible framework or scaffolding upon which other faiths could drape their creeds. One columnist labeled American yoga as little more than “a mishmash [of] Zen and Tibetan Buddhism, 12-step rhetoric, self-help philosophies, cleansing diets, exercise, physical therapy, and massage,” attributing this to an intentional effort to make it more palatable: “Hindu roots are obliterated by the modern infatuation with all things Eastern–and by our growing predilection for spiritual practices stripped of the sectarian burdens of religion” (Miller, 2010, May 31). This “salad-bar approach” (Yabroff, 2011, January 17) is motivated by public antagonism toward injecting “religious” practice in secular spaces like schools, as in the case of the Encinitas controversy, and similar situations in Albuquerque (Simonich, 2013, October 19) and even India (Scribner, 2013, October 29). Instructors scramble to modify pose sequences and terminology–for instance, “lotus position was renamed the ‘crisscross applesauce' pose” (Brown, 2013, July 02)–to appease anxious parents and administrators. Proponents largely drew on the previous signifier cluster to justify yoga programs in terms of the physiological benefits, such as a member of USA Yoga's board of directors who stated, “Yoga is a set of exercises to improve your body and your mind…it is not in and of itself a religious practice” (Holy row over yoga in schools, 2013, January 13). Voices, such as these distance yoga from ostensibly religious underpinnings, and construct it solely as fitness activity.

Interestingly, several Indian proponents disavowed yoga's Hindu roots. According to one Indian columnist, “Yoga is by no stretch of imagination ‘Hindu'; besides, ‘Hindusim' is not a proselytizing religion, but one respecting all religions” (Kamath, 2013, October 31). Inaugurating an international yoga festival on the banks of the sacred Ganges river, an Indian politician echoed Vivekananda's message, “Yoga should not be related to religion because it helps us lead a stress-free life and make our body, mind and souls pure” (Pioneer News Service, 2013, March 01). Likewise, the vice chancellor of the Swami Vivekananda Yoga Anushtana Samasthana scoffed at attempts to associate yoga with Hinduism, “Although the Vedic science was developed in India, it does not mean it is inclined toward Hinduism or Buddhism or any other religion. Yoga is based on the dos, don'ts and some commandments” (TNN, 2013, March 11). Although he did not elaborate on which specific precepts and commandments, this comment (and others like it) parallel global processes that erase yoga's theolinguistic register (Huffer, 2011) from yoga discourse (Antony, 2014). At first, these sentiments emanating from Indian mouths seem puzzling. However, they are likely prompted by an underlying incentive to market the lucrative yoga tourism industry to international customers–a theme that is explored in detail in the next section.

Despite instructors' insistence on the health benefits, apprehension toward its Hindu roots has led to the cancellation of yoga programs in Christian centers (Catholic church bans yoga class, 2012, September 26; Little, 2007, August 01), leading some to take inventive steps to adapt the practice so that it complements existing religious beliefs. Christoga: Yoga Filled Body, Christ Filled Soul aligns traditional yoga with Christian teachings (Miller, 2007, September 17). Other similar programs include the Arizona-based Yahweh Yoga and PraiseMoves–the latter including “poses that have names like Angel and Prayer Warrior, where each is tied to a specific verse in Scripture” (Miller, 2007, September 17). The owner of Holy Yoga OC in Orange County, that modifies yoga to facilitate a Christ-honoring experience, affirms that “We know that yoga predates Hinduism. It's mainly associated with Hinduism, they kind of popularized it,” [my emphasis] (Cooley, 2013, September 05). At a Miami spa, Kabbalah Yoga customers replace the traditional “Om” chant with “Shalom” as they meditate on the kabbalah's heavenly gates (Marks, 1999, August 02). Students of Avraham Kolberg, a Breslov Hassid, risk social censure, stigma, and expulsion from the ultra-conservative Hassidic community to find relief for chronic illnesses and health issues at his yoga sessions. To Kolberg, yoga asana actually fulfills “the Jewish religious mitzva to take care of themselves” (Sokol, 2013, January 04). In all these cases, yoga is intentionally detached from its religious core and then discursively linked to a new religious framework to provide an experience that is congruent and compatible with existing belief systems (Antony, 2014). Through this process, consumers can harvest the physical benefits of yoga while remaining loyal to their religious creeds, and thus are freed from any accompanying trepidation or guilt that they are encouraging “paganism” (Sokol, 2013, January 04) or risk losing their souls to the devil (Catholic church bans yoga class, 2012, September 26).

In some cases, rearticulation eliminates religion entirely, instead coalescing yogic meditation around undeniably worldly outcomes. At the Women's Yoga class mentioned earlier, the instructor advises students to manage challenging poses by guiding their thoughts toward “what in life matters the most to you. Do this for that.” When the writer follows this advice by focusing on her family and the extra jobs she works so that they can afford to follow their passions, she discovers that “suddenly, my pose was about all of that. And I was able to stay in that challenging place for them (I would have totally come out of it otherwise)” (Heckel, 2013, June 19). Although this strategy does reflect some level of the self-sacrifice and ego diminishment outlined in Patanjali's sutras, the ultimate objective is still firmly entrenched in the material sphere of direct blood relatives, which some could argue is an extension of the self. Other enterprising instructors situate yoga in the discourse of financial management and monetary gain. The founder of a wealth-management firm offers Yoga for Money workshops in Beverly Hills that “explore the semi-mystical relationship between people and their cash” to help customers mindfully approach their financial limitations and thus prepare an “accurate financial statement” (Gegax, 2003, October 20). Abacus Wealth Partners offers clients recovering from the 2008 financial crash “both financial planning and a breathing exercise called ‘the money breath' to help them to remain calm when the outlook becomes unstable.” Yogic Investing helps clients to “integrate yoga and money and ‘move your yoga practice off the mat”' to better manage their savings and stock investments (Pavia, 2013, June 11). The preoccupation with worldly wealth that characterizes these programs is a far cry from Patanjali's Yoga Sutra which advocates the eventual removal of sensory input to facilitate perfect isolation and contemplation on the divine (Strauss, 2002, 2004).

Displacing and erasing yoga's Hindu elements thus paves the way for an amorphous spiritual experience that can then be discursively molded to emphasize other faiths or pragmatic outcomes grounded in the material world. Rearticulating yoga as a spiritual rather than religious experience undermines its ostensibly “foreign” origins, and makes it less threatening to those who are wary of organized religion (Antony, 2014, 2016). These discursive maneuvers warrant close critical attention, particularly when contextualized within neo-imperialist frameworks that seek to diminish the local authority of indigenous bodies of knowledge, and thus make them amenable to neo-capitalist globalization agendas. For some, however, the final outcome matters little because yoga functions primarily to signify social capital and status.

An Elite and Exotic Commodity: Decadence and Glamor

Finally, several news articles constructed yoga as a luxury commodity that secured social prestige for the affluent and upwardly mobile alike. Whether escaping to exotic locales on extravagant yoga getaways or espousing progressive eco-conscious principles, yoga functioned as an accessory for New Age spirituality and glamorous lifestyles. In stark contrast to the “austere regimen of meditation and painful asanas” of previous ascetics, the “Ananda Himalayan destination spa” offered a 14-days yoga package in a villa with a private pool, complete with a personal breathing and meditation instructor for the modest sum of $14,415 (Guo, 2010, July 05). Africa Classic Safaris offered to close the entire South African national park for $4,370 so that customers could perform yoga beside zebras and giraffes. Other luxury tour operators vied with each other to promote yoga holidays in the Canadian Rockies, Costa Rica, Cancun, Utah ski resorts, Hawaiian hideaways, old European castles, and secluded islands off the Mozambique coast (, October 13; Guo, 2010, July 05 Klein, 2002, April 22). Typically, these packages included gourmet meals, private chefs, personal masseurs, day excursions, and studios with breathtaking views of rainforests and the ocean (Klein, 2002, April 22). One hosted tour promised “classes in the Big Apple's top yoga studios. And there'll be time for Christmas shopping, too!” (Gillmore, 2011 October 13). These exotic vacations drew liberally from popular culture to market spiritual getaways–where self-discovery was but one sun salutation away–and Elizabeth Gilbert's Eat Pray Love was recommended as “essential reading” (Delaney, 2014, February 02) by some columnists.

Simultaneously, the discourse of yoga was inextricably linked with consumerism and athleticism to market a range of branded accessories that promised to enhance the yoga experience. Nike targeted “yoganistas”–defined as “upwardly mobile women who practice yoga in order to attain inner peace and firmer buns”–with Kyoto, a cross-training sport shoe (Melillo, 2003, January 06)–unfazed by the fact that yoga asana is traditionally practiced barefoot. The tenuous connection between brand name and product prompted the news writer to muse that “maybe Nike is just pitching a general Zen concept” to customers who are drawn to “tie-dyed lacy camisole yoga tops.” Yoga wear among high-end retailers “averages $50 for tops and $77 for bottoms” (Pasquarelli, 2008, June 30). Some entrepreneurs and market analysts perceive yoga “which encourages participants to adopt an overall ecological and spiritual lifestyle, as a way to tap into current wellness and environmental trends” and thus promote clothing made from soy and bamboo fabrics. Designers attempt to create yoga outfits “that can be worn straight from the yoga studio to the nightclub,” with the primary goal being that the fabric “must be tight-fitting and breathable.” This commodification and commercialization thus constructs yoga as sporty, desirable, sexy, and eco-friendly. The pricing defines yoga as an elite activity and implies its accessibility to a specific socioeconomic bracket.

This exclusivity is mirrored by a fascination with celebrities who endorse yoga, among them Madonna, Sting, Bjork, Jake Gyllenhaal, Cameron Diaz, and Britney Spears (Slater, 2013, May 28; Dasgupta, 2013, August 02). Comedian, actor, and Kundalini yoga enthusiast Russell Brand is credited with guiding a string of high-profile romantic partners, including the recently divorced Demi Moore, to yoga in their “search for spiritual fulfillment” (Cover Media, 2013, February 21). Brand describes Kundalini yoga as “highly psychological, and very beautiful…and real, and trippy” (Warrington, 2013, May 11), exemplifying the Orientalist discourse of a strange and mysterious East that, coupled with sexiness and desire, characterizes the commodification and marketing of most yoga experiences. This air of fandom also contributed the cult status of several high-profile and eccentric yoga instructors, such as the controversial Bikram Choudhury, the elusive Daniele Boido (Slater, 2013, April 06)–who typically “charges £80 a session, but recently saw a client in exchange for a mango”–and the entrepreneurial John Friend who founded the Anusara yoga trademark (Slater, 2013, May 28).

As a lifestyle accessory, yoga functions as a flexible signifier that complements New Age spiritual seekers and adventure enthusiasts alike, and more extreme yoga enthusiasts can dabble in super power yoga (where participants wear weighted vests to boost strength), paddleboard yoga (that fuses surfing and yoga), and yoga hiking (a barefoot 90-min brisk hike with regular stops for brief yoga sessions; Transcending the Serenity of the Soul, 2013 February 23). Interestingly, yoga's diversification and polysemy is enthusiastically endorsed by Indian spokespersons. For instance, Britney Spears' newfound fascination with yoga elicited praise from some Hindus who then invited her to explore “the other five orthodox systems of Hindu philosophy” (US Hindus urge Britney Spears to go beyond Yoga, 2013, May 13). The Indian government also heartily publicized Zambhala, the first ever Yoga, Music and Life Spirit Festival in India. A spokesperson who described India as “the spiritual home of Yoga and the search for personal enlightenment,” labeled this event “India's Glastonbury Festival–with Yoga and Spirituality at the heart of it” (Dasgupta, 2013, August 02), thus likening this event to the extremely popular annual performing arts Glastonbury Festival in England. Indians therefore embrace the discursive displacement toward an ambiguous and vague spirituality that characterizes the consumerist marketing of yoga, while still laying claim to it as an essentially Indian artifact. This aggressive marketing and pandering to Western rearticulation may be attributable to the booming “spiritual and wellness tourism” industry which generated $1.3 billion in foreign exchange earnings in 2011, and continues to steadily grow (Pagnamenta, 2011, November 15).

An obsession with material accessories, glamorous locations, and cultural icons thus situates yoga as an elite and exotic commodity embedded within the overlapping frameworks of cosmopolitanism, consumerism, and New Age spiritual renewal. I now situate these findings within the broader context of ownership, symbolic displacement, and the global circulation of appropriated indigenous artifacts.

Discussion

The cultural identity of indigenous artifacts embodies and reflects the ontological assumptions of a particular people in a particular place (Dirlik, 2003), yet appropriation (Rogers, 2006) inevitably complicates issues of ownership and place-basedness. As an indigenous artifact, yoga's roots trace back to seminal Vedic texts that were deeply entrenched in Hindu philosophy (Blank, 1992; McDaniel, 2012), yet several levels of symbolic displacement over centuries have functioned to distance this artifact from its original foundations. My findings illustrate the manner in which yoga is divested of its religious connotations to discursively rearticulate it as a vehicle to achieve physical and emotional wellness, a nebulous spiritual experience that is easily filled by other religious creeds, and an elite and exotic commodity that is accessible through consumerism. Yoga's origins and foundations are rooted in ontological assumptions that emphasize the diminution and obliteration of the ego in a quest for perfect union with the divine (Strauss, 2002). Its resignification and appropriation have transformed this indigenous practice into an artifact that complements and sustains neoliberalist frameworks, individualism, and personal accomplishment (Stroud, 2003). Furthermore, rearticulating yoga as a spiritual rather than religious experience undermines its ostensibly “foreign” origins, and makes it less threatening to those who are wary of non–Judeo Christian faiths. Ultimately, this turn of the wheel articulates yoga in ways that complement the specific zeitgeist of a late-capitalist millennial ethos. Divorced from its origins and elements that reflect a primarily Vedic and Hindu ontological system of belief, yoga now represents an amorphous, vaguely spiritual, and (primarily) physical practice that is easily coupled with prevailing discourses of mind/body wellness, expedient healing and rejuvenation, and new-age spirituality. Yoga's latest symbolic rearticulation also positions it as a malleable form of meditation and exercise, whose apparently foreign components can be safely molded and integrated within dominant Euro-centric religious frameworks without threatening or challenging the familiar and fundamental theological underpinnings of these primarily Western faith systems. In this manner, yoga as it has been commodified and reproduced within the current neoliberal context bears some hallmarks of its earlier nineteenth century rearticulation, yet pivots undeniably further from its apparently Indian origins. Even variations that purportedly espouse particular strains of Vedic practice (e.g., Bikram and Iyengar variations) demonstrate an unmistakable catering to Western (or global) appetites and proclivities.

Theoretically, yoga's appropriation, resignification, and commodification involve a fundamental delinking of the artifact from its foundational philosophy. The early stages of ashtanga are detached and isolated from the progression toward advanced stages that advocate uninterrupted meditation and concentration on the Absolute (Strauss, 2002). Yoga becomes a free-floating signifier disconnected from the very ontological tenets and epistemological assumptions that motivated its inception. Symbolic displacement and rearticulation thus necessitates the forging and affirmation of new chains of significance within these varied contexts–an endeavor that poses particular challenges in non-religious contexts, such as the Women's Yoga and Yoga for Money workshops. In these cases, rearticulation entails discursively connecting the master signifier “yoga” to other powerful social and economic structures, while simultaneously bolstering this connection by grounding the practice in the rational scientific paradigm (Bourne, 2010). This analysis also demonstrates how yoga is subsumed by a global appetite for New Age spirituality (Islam, 2012) fueled by a blend of hyper-consumerism of the indigenous (artifacts, experiences, and locales), eco-consciousness, and an infatuation with Eastern spirituality and mysticism. Celebrity appeal combines with these characteristics to discursively construct yoga as elite, sensual, and exotic.

Ownership and cultural authenticity are further complicated when the nodal center is discursively attached to other religious creeds, such as Christianity and Judaism. Does the erasure and replacement of Hindu elements with those corresponding to other faiths diminish the ultimate goal, i.e., perfect union with the divine? Some experts might argue that yoga's authenticity is diluted when it is discursively distanced from its Hindu origins (Stroud, 2003; Huffer, 2011). Yet this research provides strong evidence that these processes are endorsed and even encouraged by Indians. Why do Indians acquiesce to–and indeed, propagate–the very discourses that displace and undermine the historical foundations of this traditional indigenous artifact? My findings demonstrate that the re-appropriation of previously appropriated artifacts can reinforce and affirm symbolic displacement, particularly when the original culture recognizes the social value of the commodity and its economic potential. To clarify, eradicating Hinduism from yogic discourse and rearticulating yoga as an amorphous “one-size-fits-all” spirituality (Huffer, 2011) expands and proliferates its utility to global consumers, and the Indian economy can subsequently reap the benefits of “spiritual” tourism. However, here an interesting opposition develops between native Indians and non-resident Indians (colloquially referred to as NRIs), particularly those settled in the U.S., with the latter being far more likely to decry yoga devoid of Hindu elements (this may hold true for the primarily NRI-composed Hindu American Foundation). A columnist with the New York Times attributes this antagonism to a complex diasporic identity crisis, describing this population as “middle-class South Asian settlements in the United States that are growing disenchanted, whether discreetly or overtly, with the West and thus are becoming obsessed with their roots” (Joseph, 2013, January 17). He further observes that distance from the homeland coupled with a strong conservative streak clouds their reception of all things Indian. It is therefore possible that whereas native Indians capitalize on the lucrative opportunities that symbolic displacement poses for yoga tourism to India, some NRIs reject global processes that tarnish Indianness and Hinduism in global spaces.

Does detaching yoga from its religious origins fundamentally compromise its core principles? Blank (1992) claims that the religious yoga of a devout Hindu bears little similarity to the stretching and relaxation classes which go by that name in America: “about as much relation, perhaps, as receiving holy communion has to do with munching Saltines: the latter action is similar, but stripped of all meaning” (p. 44). This view complements that of critical scholars who condemn the appropriation of indigenous artifacts by drawing attention to inherent power imbalances (Rogers, 2007; Van der Veer, 2007; Islam, 2012). However, history distinguishes yoga from other appropriated artifacts. First, yoga's early restriction to predominantly male, high-caste, south Asian, ascetics (Strauss, 2002) betrays its elitist roots. Appropriation has overturned this asymmetrical power balance and promoted its accessibility to other populations. Second, yoga's first level of symbolic displacement can be traced back to a prominent Indian leader who single-handedly replaced the religious register with universalist principles (Strauss, 2004). These facts complicate issues of ownership, nativeness, and privilege that typically accompany the critical examination of appropriated artifacts.

While I support and echo these concerns, it is also important to transcend the rigid confines of essentialism to truly appreciate the symbolic diversification and polysemic pluralism of traveling cultural artifacts (Dirlik, 2003; Wilson, 2012). Scholars who reify and glorify the local, ethnic, and indigenous may inadvertently preclude opportunities for genuine and appreciative intercultural encounter and engagement. Essentialist and reductive interpretations of the local/global binary can present challenges and barriers to the evolving polysemic environments of hybrid spaces and subjectivities in an increasingly globalized world. Such perspectives can limit the propensity for democratic participation and access to cultural artifacts and resources by resorting to narrow definitions of belonging and in-group membership. Yoga's journey has diversified its interpretations, applications, and utilities to a range of audiences in evolving global contexts. Resisting the knee-jerk instinct to hastily condemn and criticize inauthenticity can open scholarly eyes to the “liminal space which is revolutionary and engaged in a continual process of translation”–where there is “never an original or essential meaning, [but] rather one that is imitated, simulated, copied or transformed” (Chand, 2007, p. 139). Bhabha (1994) also cautions against valorizing the past at the expense of disregarding the future when he notes that traditional practices can sometimes be “revalued as a form of anteriority–a before that has no a priori(ty)–whose causality is effective because it returns to displace the present, to make it disjunctive” (p. 174). I therefore urge an appreciation for the unique transcription that local cultures impose on traveling artifacts (Wilson, 2012).

That said, it is important to consider the implications of stripping contemporary yoga of its Hindu elements, particularly with regard to how minor faiths are represented in mainstream discourse. Moves, such as this construct Hinduism as “traditional, stagnant, ritualistic, and in the process siphon off its potential for innovation and renewal in modernity” (Huffer, 2011, p. 376), an observation that gains relevance within the current jittery climate generated by Islamophobia and the perceived threat of brownness (Semati, 2010). Furthermore, instructors who choose to resignify yoga in a manner that communicatively distances it from Hinduism and Vedic ontology (inadvertently) contribute to hegemonic trends that confine non-Western belief structures to the periphery by fostering the misinterpretation of ancient religious traditions (Antony, 2016). The Hindu thus remains an ostensibly foreign and inscrutable entity within the mainstream American cultural milieu (Antony, 2014). A disinclination to reconcile Hinduism and yoga diminishes the potential for meaningful intercultural dialogue and understanding.

This analysis is doubtless limited by the fact that it has only considered primarily print coverage of yoga. Additionally, the dataset was restricted only to those publications (and drew primarily from U.S. and U.K. press outlets) that contained the specified keywords. There is a wealth of information available in other media texts, including popular media, blogs, popular entertainment texts, and instructional videos, that may better inform the discursive construction of yoga for global audiences. The current study provides but one glimpse of how prominent media institutions impact the ways in which global audiences encounter and understand yoga. Additional analyses that encompass other media and cultural products will no doubt lend richness and complexity to understanding how non-Western cultural artifacts–and yoga, in particular–are rearticulated, commodified, and consumed in contemporary neoliberal contexts. Another valuable avenue for investigation concerns the ways in which recent nativist trends in India (for instance, the Modi government's initiatives to capitalize on the inherent “Hindu-ness” of yoga) passionately challenge the appropriation outlined in this manuscript. Attempts to wrest this indigenous cultural artifact away from New-Age spiritualists and multinational fitness corporations tenaciously reinforces yoga's Vedic origins, yet continue to fragment the evolving polysemy of an already complex signifier as yoga becomes a tool to promote tourism and simultaneously propelling a fundamental Hindu nationalist agenda.

Author Contributions

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and has approved it for publication.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

Antony, M. G. (2010). On the spot: seeking acceptance and expressing resistance through the bindi. J. Int. Intercult. Commun. 3, 346–368. doi: 10.1080/17513057.2010.510606

Antony, M. G. (2014). “It's Not Religious, But It's Spiritual:” Appropriation and the Universal Spirituality of Yoga. J. Commun. Religion 37, 63–75. Available online at: http://connection.ebscohost.com/c/articles/112266259/not-religious-but-spiritual-appropriation-universal-spirituality-yoga

Antony, M. G. (2016). Tailoring Nirvana: Appropriating Yoga, resignification, and instructional challenges. Int. J. Media Cult. Polit. 12, 283–303. doi: 10.1386/macp.12.3.283_1

Appadurai, A. (1988). “Introduction: commodities and the politics of value,” in The Social Life of Things: Commodities in Cultural Perspective, ed A. Appadurai (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), 353–371.

Askegaard, S., and Eckhardt, G. M. (2012). Glocal yoga: re-appropriation in the Indian consumptionscape. Mark. Theory 12, 45–60. doi: 10.1177/1470593111424180

Bourne, J. (2010). Pedagogic practice, culture and the globalization of yoga teaching. J. Appl. Linguist. Prof. Pract. 7, 11–26. doi: 10.1558/japl.v7i1.11

Brown, C. G. (2013, July 24). What Makes the Encinitas School Yoga Program Religious? The Huffington Post: Religion. Retrieved 08/10/2013, Available online at: http://www.huffingtonpost.com/candy-gunther-brown-phd/encinitas-yoga-lawsuit_b_3570850.html.

Burke, T. (2007, June 27). Quick guide to… YOGA. Resources: Young People Now. Retrieved 03/13/2014, Available online at: http://www.cypnow.co.uk/ypn/news/1063291/resources-quick-guide-yoga.

California school yoga program gets $1.4m grant (2013, August 01). The Associated Press. Retrieved 08/10/2013, Available online at: https://www.yahoo.com/news/california-school-yoga-program-gets-1-4m-grant-171313325.html.

Capouya, J. (2003, June 16). Reaching Your Peak: Real Men do Yoga. Health for Life: Newsweek. Retrieved 03/13/2014, Available online at: http://www.newsweek.com/reaching-your-peak-real-men-do-yoga-137713.

Catholic church bans yoga class (2012, September 26). Breaking News: Belfast Telegraph Online. Retrieved 03/13/2014, Available online at: http://www.belfasttelegraph.co.uk/breakingnews/offbeat/catholic-church-bans-yoga-class-28867770.html.

Chand, A. (2007). The Fiji Indian chutney generation: the cultural spread between Fiji and Australia. Int. J. Media Cult. Polit. 3, 131–148. doi: 10.1386/macp.3.2.131_1

Chaoul, M. A., and Cohen, L. (2010). Rethinking yoga and the application of yoga in modern medicine. Crosscurrents 60, 144–167. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-3881.2010.00117.x

Cooley, R. (2013, September 05). Holy Yoga Adds Spirit to Mind and Body. Orange County Register, p. D. Orange County, CA.

Cover Media (2013, February 21). Demi Moore ‘calls Brand spiritual guru.' Entertainment News: Belfast Telegraph Online. Retrieved 03/13/2014. Available online at: http://www.belfasttelegraph.co.uk/entertainment/news/demi-moore-calls-brand-spiritual-guru-29086354.html.

Dasgupta, P. (2013, August 02). Zambhala Festival to be Held in Goa. People: The Times of India (Kolkata).

Delaney, B. (2014, February 02). Salute to the Sun; Travel. Sunday Life: The Sun Herald, p. 26 (Biloxi, MS).

Dirlik, A. (2003). Globalization, indigenism, and the politics of place. Ariel 34, 15–29. Available online at: https://journalhosting.ucalgary.ca/index.php/ariel/article/view/34696

Dutta, M. J., and Zoller, H. M. (2008). Theoretical foundations: Interpretive, critical, and cultural approaches to health communication. in Emerging Perspectives in Health Communication: Meaning, Culture, and Power, eds H. M. Zoller and M. J. Dutta (New York, NY: Routledge), 1–28.

Fontyn, Y. (2010, December 28). Bend to feel better. Financial Mail. BizCommunity.com. Available online at: http://www.bizcommunity.com/Print.aspx?l=196&c=148&ct=1&ci=55478.

Gautam, J. (2007, December 07). I Relax With…Chanting Yoga. GP Life: GP. Retrieved 03/13/2014, Available online at: http://m.gponline.com/article/771418/i-relax-with-chanting-yoga.

Gegax, T. T. (2003, October 20). Finance: Cash yoga. Periscope: Newsweek, Retrieved 03/13/2014, Available online at: http://www.newsweek.com/finance-cash-yoga-138643.

Gillmore, L. (2011, October 13). The Perfect Holidays for Posers. Europe: The Indepenent, Retrieved 03/13/2014, Available online at: http://www.independent.co.uk/travel/europe/the-perfect-holidays-for-posers-2368947.html.

Gold, J. B. (2011). A critical glimpse at the American appropriation of Asian meditative traditions: confessions of an unsuccessful meditator. Int. J. Religion Spiritual. Soc. 1, 139–148. doi: 10.18848/2154-8633/CGP/v01i02/51144

Guo, J. (2010, July 05). Upmarket-Facing Dog. Newsweek, 156. Available online at: http://www.newsweek.com/upscale-yoga-retreats-73035.

Hindu American Foundation (2013). Take Yoga Back: Bringing to Light Yoga's Hindu Root. Retrieved 08/10/2013, Available online at: http://www.hafsite.org/media/pr/takeyogaback

Huffer, A. J. (2011). Hinduism without religion: Amma's movement in America. Crosscurrents 61, 374–398. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-3881.2011.00188.x

Impett, E. A., Daubenmier, J. J., and Hirschman, A. L. (2006). Minding the body: Yoga, embodiment and well-being. Sexual. Res. Soc. Pol. 3, 39–48. doi: 10.1525/srsp.2006.3.4.39

Islam, N. (2012). New age orientalism: Ayurvedic ‘wellness and spa culture'. Health Sociol. Rev. 21, 220–231. doi: 10.5172/hesr.2012.21.2.220

Jorgensen, M., and Phillips, L. J. (2002). Laclau and Mouffe's discourse theory. in Discourse Analysis as Theory and Method, eds M. Jorgensen and L. J. Phillips (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications), 24–59.

Joseph, M. (2013, January 17). U.S. Hindus Hear the Call of India. India Letter: The New York Times (New York City, NY).

Kamath, M. V. (2013, October 31). What's in a Name? Culture, not Religion. The Free Press Journal. Retrieved 03/13/2014, Available online at: http://www.freepressjournal.in/analysis/whats-in-a-name-culture-not-religion/246765.

Katrak, K. H. (2004). ‘Cultural translation' of Bhratanatyam into ‘contemporary Indian dance': second-generation South Asian Americans and cultural politics in diasporic locations. South Asian Pop. Cult. 2, 79–102. doi: 10.1080/1474668042000275699

Ketola, K. (2009). Can the modes theory of religiosity account for mystical traditions? An empirical study of practitioners of yoga and meditation. J. Cogn. Cult. 9, 79–113. doi: 10.1163/156853709X414665

Khalsa, S. B. S., Khalsa, G. S., Khalsa, H. K., and Khalsa, M. K. (2008). Evaluation of a residential Kundalini yoga lifestyle pilot program for addiction in India. J. Ethn. Subst. Abuse 7, 67–79. doi: 10.1080/15332640802081968

Klein, D. A. (2002, April 22). Inner Peace, Good Eats. Focus on Travel: Newsweek. Retrieved 03/13/2014, Available online at: http://www.newsweek.com/inner-peace-good-eats-142927.

Little, M. (2007, August 01). Salvation Army Bans Yoga at HQ. Management: Third Sector. Retrieved 03/13/2014, Available online at: http://www.thirdsector.co.uk/Management/article/674147/Salvation-Army-bans-yoga-HQ/.

Lupton, D. (1994). Toward the development of critical health communication praxis. Health Commun. 6, 55–67. doi: 10.1207/s15327027hc0601_4

Marks, M. (1999, August 02). Quieting the Soul. The Jerusalem Report. Retrieved, 03/13/2014, Available online at: http://www.beliefnet.com/Faiths/Judaism/2000/01/Quieting-The-Soul.aspx.

McDaniel, J. (2012). The role of yoga in some Bengali bhakti traditions: Shaktism, gaudiya vaisnavism, baul, and sahajiya dharma. J. Hindu Stud. 5, 53–74. doi: 10.1093/jhs/his011

Melillo, W. (2003, Januray 06). Ohm No! AdWeek: Art & Commerce. Retrieved 03/13/2014, Available online at: http://www.adweek.com/news/advertising/art-commerce-ohm-no-60730.

Miller, L. (2010, May 31). Do Yoga's Hindu Roots Matter? Newsweek, 155, 25. Available online at: http://www.newsweek.com/do-yogas-hindu-roots-matter-72463.

O'Reilly, S. (2008, January 08). Wellbeing in Focus: Yoga Classes – Bending the Rules. Personnel Today. Available online at: http://www.personneltoday.com/hr/wellbeing-in-focus-yoga-classes-bending-the-rules/.

Pagnamenta, R. (2011, November 11). It's Getting Crowded on Path to Enlightenment. Asia: The Times. Retrieved 03/13/2014, Available online at: http://www.thetimes.co.uk/tto/news/world/asia/article3226573.ece.

Pasquarelli, A. (2008, June 30). Yoga Craze Brings Retailers to Zen Zone: J. Crew, Others Launch Apparel Lines, Squeezing the Studios? News: Crain's New York Business, p. 2 (New York City, NY).

Pavia, W. (2013, June 11). Financial Advisers Seek Inner Peace – and Big Profts. US & Americas: The Times. Retrieved 03/13/2014, Available online at: http://www.thetimes.co.uk/tto/news/world/americas/article3787675.ece.

Pew Research Center (2012, October 09). “Nones” on the Rise: One-in-Five Adults Have no Religious Affiliation. The Pew Forum on Religion & Public Life. Available online at: http://www.pewforum.org/2012/10/09/nones-on-the-rise-new-report-finds-one-in-five-adults-have-no-religious-affiliation/.

Pioneer News Service (2013, March 01). Yoga Key to Healthy Body, Mind: CM. The Pioneer (India), Retrieved 03/13/2014. Available online at: https://www.dailypioneer.com/columnists/edi/nothing-religious-about-it.html.

Rajghatta, C. (2013, June 23). New York's Times Square Becomes Yoga's Om Sweet Om. The Times of India, Retreived 03/13/2014, Available online at: http://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/world/us/New-Yorks-Times-Square-becomes-yogas-Om-Sweet-Om/articleshow/20718096.cms.

Rogers, R. A. (2006). From cultural exchange to transculturation: a review and reconceptualization of cultural appropriation. Commun. Theory 16, 474–503. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2885.2006.00277.x

Rogers, R. A. (2007). Deciphering Kokopelli: masculinity in commodified appropriations of Native American imagery. Commun. Crit. Cult. Stud. 4, 233–255. doi: 10.1080/14791420701459715

Rossi, H. L. (2006, October 02). BeliefWatch: God's Gift. Periscope: Newsweek. Retrieved 03/13/2014, Available online at: http://www.newsweek.com/beliefwatch-gods-gift-111541.

Scribner, H. (2013, October 29). Yoga as Religion Debate Heats up in India. Deseret Morning News (Salt Lake City, UT).

Semati, M. (2010). Islamophobia, culture, and race in the age of empire. Cult. Stud. 24, 256–75. doi: 10.1080/09502380903541696

Simonich, M. (2013, October 19). Yoga is a Banned Word for New Mexico Fitness Teacher. News: Farmington Daily Times.

Slater, L. (2013, April 06). Daniele Boido, the A list's go to guru. The Times. Available online at: https://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/daniele-boido-the-a-lists-go-to-guru-66nw3wkcgx2.

Sokol, S. (2013, January 04). Breaking Stigmas in a Relaxed Way. Features: Jerusalem Post, p. 30 (Jerusalem).

Stam, R., and Shoat, E. (2005). “De-Eurocentricizing cultural studies: some proposals,” in Internationalizing Cultural Studies: An Anthology, eds A. Abbas, and J. Nguyet Erni (Malden, MA: Blackwell), 481–498.

Strauss, S. (2002). “Adapt, adjust, accommodate”: the production of yoga in a transnational world. Hist. Anthropol. 13, 231–251. doi: 10.1080/0275720022000025556

Strauss, S. (2004). Re-orienting yoga. Expedition 46, 29–34. Available online at: http://www.penn.museum/sites/expedition/?p=8855

Stroud, S. R. (2003). Narrative translation across cultures: from the Bhagavad Gita to The Legend of Bagger Vance. J. Commun. Religion 26, 51–82. Available online at: http://connection.ebscohost.com/c/articles/10954933/narrative-translation-across-cultures-from-bhagavad-gita-legend-bagger-vance

Talbot, M., and Schwartz, J. (1992, February 03). Om is Where the Heart is. Life/Style: Newsweek, p. 71 (New York City, NY).

TNN (2013, March 11). Yoga & Hinduism? It's All in the Mind. The Times of India, Bangalore Edn. Retrieved 03/13/2014, Available online at: http://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/bangalore/Yoga-Hinduism-Its-all-in-the-mind/articleshow/18901858.cms?referral=PM.

Toribio, E. (2014, March 04). Ask the Yogi: Posing Questions, Answers. Life: Herald News, p. D01 (Fall River, MA).

Transcending the Serenity of the Soul (2013, February 23). Transcending the Serenity of the Soul, it's the Rise of the Yoga Show-Offs. Health: The Times. Retrieved 03/13/2014, Available online at: http://www.thetimes.co.uk/tto/health/article3696413.ece.

US Hindus urge Britney Spears to go beyond Yoga (2013, May 13). World: India Noon. Retrieved 03/13/2014, Available online at: http://www.rangdeindia.tv/spotlightdetail/us-hindus-urge-britney-spears-to-go-beyond-yoga/37967.

Valanciute, A., and Thampy, L. A. (2011). Physio Kundalini syndrome and mental health. Mental Health Religion Cult. 14, 839–842. doi: 10.1080/13674676.2010.530648

Van der Veer, P. (2007). Global breathing: religious utopias in India and China. Anthropol. Theory 7, 315–328. doi: 10.1177/1463499607080193

Warrington, R. (2013, May 11). Turbans and White Robes: The Latest Yoga Craze is Kundalini. Diet and Fitness: The Times. Retrieved 03/13/2014, Available online at: http://www.thetimes.co.uk/tto/health/diet-fitness/article3760584.ece.

Wilson, K. (2012). The space of salsa: theory and implications of a global dance phenomenon. At the Interface/Probing the Boundaries 79, 207–217.

Yabroff, J. (2011, January 17). The Downward Facing Memoir. Culture: Newsweek, 157, p. 53 (New York City, NY).

Yoga Warriors International (2013). Yoga Warriors International: Healing the Wounds of War Breath by Breath. Retrieved 08/13/2013. Available online at: http://www.yogawarriors.com/

Keywords: Yoga, cultural appropriation, spirituality, Hinduism, rearticulation

Citation: Antony MG (2018) That's a Stretch: Reconstructing, Rearticulating, and Commodifying Yoga. Front. Commun. 3:47. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2018.00047

Received: 29 September 2017; Accepted: 03 October 2018;

Published: 23 October 2018.

Edited by:

Iccha Basnyat, James Madison University, United StatesReviewed by:

Raihan Jamil, Zayed University, United Arab EmiratesShaunak Sastry, University of Cincinnati, United States

Copyright © 2018 Antony. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Mary Grace Antony, YW50b255bUB3d3UuZWR1

Mary Grace Antony

Mary Grace Antony