- 1Department of Environmental Studies, State University of New York College of Environmental Science and Forestry, Syracuse, NY, United States

- 2Texas A&M Natural Resources Institute, College Station, TX, United States

State and national park land management is rife with conflict, be it either over how land is managed within the park or how it affects adjacent private lands. The Adirondack Park in upstate New York is an especially interesting case due to its unique mix of public and private lands within the boundaries of the park, often referred to as the Blue Line. A recent land acquisition by the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation (NYSDEC) and the resultant land classification process is the most recent conflict in the region in a long line of land use/land designation conflicts. In the wake of recent attempts for greater collaboration, we explored this conflict by conducting a framing analysis of both stakeholders' online presence (i.e., websites and blogs) and local news media coverage of the classification process. Primary stakeholders included local town residents, sportsmen groups, NYSDEC, Adirondack Park Agency, local government, and environmental groups. We found that stakeholder groups' online materials utilized frames to describe their objectives based on different values. Dominant frames included a “reasonable access” frame used by residents and town officials to highlight rights to accessible use. Environmental groups heavily used an “environmental protection” frame, highlighting the ecologically important wetlands and opportunity to increase lands designated as “Wilderness.” In news media articles, the dominant frame was the “conflict frame,” portraying the decision-making process as riddled with tension and incompatibility. These frames indicate that the conflict over land classification stems from different values of accessibility and strong wilderness protection as well as being communicated as intractable by the media.

Introduction

At 6 million acres and comprised of roughly equal parts public and private lands, the Adirondack State Park (hereafter, the Adirondack Park or the Park) in upstate New York is unique in both its size and its composition. While mixed-use and multi-ownership parks are common in other countries (see the UK's Peak District National Park and Denmark's National Park Thy), the prevailing model in the United States remains one based in the “National Park Ideal,” defined by Neumann (1998, p. 9) as:

“the notion that ‘nature' can be ‘preserved' from the effects of human agency by legislatively creating a bounded space for nature controlled by a centralized beauracratic authority…initially implemented in the nineteenth century United States at Yellowstone…”

Of central importance is that the national park ideal is rooted in images of “pristine, untouched nature” created to provide an escape from development, yet a nature that is largely approached esthetically, as “scenery” (Neumann, 1998, p. 9). Further, in the United States, park creation has been built principally on a model of sole ownership (Sellars, 1997). This translates to federally controlled national parks that have been established through processes of dispossession and marginalization of those residing on today's park lands, most notably Native Americans who were forcibly removed from their ancestral lands so those lands could be deemed “pristine wilderness” and protected, emparked (Hecht and Cockburn, 1990; Neumann, 1998). Those processes may have been acute and immediate or may have constituted a gradual overtaking, but the result was the same—a federally controlled parcel of land from which traces of former inhabitants had been erased and the land deemed empty and wild (Hecht and Cockburn, 1990; Neumann, 1998).

The Adirondack Park thus presents a truly unique case in the American context. While it certainly follows Neumann's “National Park Ideal” in some ways (parcels of land are set aside as “natural” and promised to the Forest Preserve as “Forever Wild”), it is also singular in its composition—half public, half private, a truly mixed-use landscape. Deemed the “Great Experiment in Conservation” (Porter et al., 2009), it may very well serve as a model for parks in this country as we look to the next century of land conservation and preservation, as opportunities for preserving and protecting large swaths of land in today's socio-political and geographic climate diminish. With this unique composition, however, come challenges perhaps not faced by other, more traditionally modeled parks in the U.S. Indeed, conflict over land and resources has been part of the Park's history since its 1892 creation, beginning as early as the establishment of the Adirondack Forest Preserve, which predated the Park by 7 years (Terrie, 2008; Porter et al., 2009; Vidon, 2016). Historically, contestation in the Park principally has been driven by New York State's acquisition and (re)classification of land. The State of New York, represented in the Park by the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation (NYSDEC) and the Adirondack Park Agency (APA), maintains interest in purchasing as much private land in the Park as possible and committing that land to the Adirondack Forest Preserve, constitutionally protected as “Forever Wild” by Article XIV of the New York State constitution. The NYSDEC then classifies those lands according to the use(s) it deems appropriate, which has the potential to increase conflict with local communities and other stakeholders, depending on user groups and the impact that classification will have. There has been a recent flurry of activity associated with purchases and classifications, as the state purchased a large amount of land from timber company Finch, Pruyn, and Co. (hereafter, Finch and Pruyn) and has been in the process of reclassification for the past several years.

We use the recent acquisition and classification of Boreas Ponds in Adirondack Park as a case study to illustrate and underscore our central contention: in matters of land acquisition and classification, such conflicts are very often subsumed into the well worn environment versus development debate. Analysis of the Boreas Ponds case, however, reveals instead a much more nuanced situation—a complex social landscape with its own set of identities, histories, voices, and experiences that cannot be reduced to a mere environment/development dichotomy. Here, we come to these nuances and complexities through the use of framing analysis, which allows us to investigate the interests and positions of different stakeholder groups, including their representation by news media, in this unique social and physical landscape. Framing analysis provides a mechanism through which we may better understand stakeholders' different perspectives, how they developed or acquired these perspectives and allow greater insight into the media's portrayal of the process (Shmueli, 2008). Stakeholder groups include residents of local communities, local officials, sportsmen groups, environmental groups, the NYSDEC, and the APA. The case itself, including its rich history and complex sets of social and political relations, provides an empirical anchor for the more theoretical considerations and central contributions of this work. Thus, we begin by providing the background necessary for contextualizing this unique place, a critical step in understanding the nuances of both the area's contentious history and the challenges it currently faces.

The Boreas Ponds Tract is a 20,786-acre parcel purchased by New York State (NYS) from the Nature Conservancy in April 2015 and is the largest acquisition made by the state in over a century (NYSDEC, 2016). This was part of a larger acquisition totaling 69,000 acres of former Finch & Pruyn lands that was initially sold to The Nature Conservancy. The Boreas Ponds Tract is located in the Central Adirondacks between the towns of Newcomb and North Hudson, both of which rely heavily on tourism to support their economies (Tohamy and Swinscoe, 2014).

After the state acquires a parcel of land, it is then tasked with classifying that parcel, based on its own goals and objectives as well as on public opinion, gathered in the form of a formal public comment period. Each land classification includes its own set of restrictions regarding use, access, and appropriate esthetics of the land (i.e., what built structures are permissible). These restrictions on access, use, and esthetics often occupy the heart of conflicts around the classifications, as each user or stakeholder group has its own ideas about how those parcels of land should be used and what they should look like. While there are many classifications in NYSDEC's schema, the most important for our purposes are Wilderness and Wild Forest, as these are the two that were most hotly debated. The most prohibitive classification is Wilderness, defined in part as:

“…an area where the earth and its community of life are untrammeled by man—where man himself is a visitor who does not remain. A wilderness area is further defined to mean an area of state land or water having a primeval character, without significant improvement or protected and managed so as to preserve, enhance and restore, where necessary, its natural conditions, and which generally appears to have been affected primarily by the forces of nature, with the imprint of man's work substantially unnoticeable…” (NYSDEC, 2018a).

In an Adirondack Wilderness area, no motorized vehicles are allowed, nor are any structures that appear to be human made. Previous research has indicated that while this classification may appeal to stakeholders such as environmental groups and nature tourists who wish to backpack and camp, it may be less appealing to sportsmen groups who need all-terrain vehicles (ATVs) to hunt or to residents or business owners who wish to bring in a more diverse group of tourists to their communities (Vidon, 2016, 2017). Wild Forest is a less prohibitive classification, even allowing for motorized vehicles and roads, provided those are incorporated into the Unit Management Plan (UMP). Wild Forest is defined by the NYSDEC as:

“…an area where the resources permit a somewhat higher degree of human use than in wilderness, primitive or canoe areas, while retaining an essentially wild character. A wild forest area is further defined as an area that frequently lacks the sense of remoteness of wilderness, primitive or canoe areas and that permits a wide variety of outdoor recreation…Wild forest areas are managed to provide opportunities for a greater variety of recreational activities and a higher intensity of recreational use.” (NYSDEC, 2018b).

As mentioned above, Boreas Ponds was part of a much larger acquisition of lands formerly owned by timber company Finch & Pruyn and sold to the state in a phased five-year contract. As the state has classified others already (Essex Chain Lakes was the latest to go through this process), Boreas Ponds is the most recent parcel in the lineup. Thus, it is no great surprise that residents in the Central Adirondacks may be feeling some degree of land classification fatigue - they have been dealing with these acquisitions and classifications now since 2007, when the Adirondack Nature Conservancy first purchased all 161,000 acres from Finch and Pruyn and NYS agreed to buy 65,000 of these acres (Brown, 2014; Vidon, 2016). Nevertheless, the Boreas Ponds acquisition did not turn contentious until the Draft Supplemental Environmental Impact Statement (DSEIS) was released with three classification alternatives, all of which allowed motor vehicle access. This suite of alternatives flew in the face of what multiple stakeholder groups in the region had been calling for—a Wilderness alternative that would preserve the natural splendor of Boreas Ponds, and the perceived slight set the stage for contentious public hearings beginning in November 2016. Important to note is that the Boreas Ponds alternatives came on the heels of the Essex Chain Lakes classification debate, which ended in a Wild Forest determination rather than the Wilderness for which many were advocating (Brown, 2014; Vidon, 2016). That the initial Boreas Ponds alternatives lacked a mostly Wilderness option was not a singular or isolated affront, but was perceived instead as one more insult by some stakeholder groups, particularly local environmental groups (i.e., Protect the Adirondacks, Adirondack Wild, Adirondack Wilderness Advocates) and nature tourists who recreate in the area (Brown, 2014; Vidon, 2016). Also important, however, is that Boreas Ponds, having been owned by a timber company, has logging roads throughout the parcel, one of which (Gulf Brook Road) runs directly to the ponds. In addition, Finch and Pruyn leased their lands to sportsmen and hunting groups such as the Gooley Club. Sportsmen groups used the logging roads for their ATVs and trucks so they could haul away what they hunted, and argued that since the roads were already there, a Wilderness designation was a difficult one to sell. Following criticism from environmental groups, nature tourists, and others from “downstate” (i.e., New York City), however, the NYSDEC and APA proposed a fourth alternative that included more Wilderness, thus restricting motor vehicle use near the ponds where the logging roads exist. Conflict emerged in public hearings as environmental groups, sportsmen groups, and local town officials disagreed over which classification alternative should be chosen. Perhaps predictably, local town officials and sportsmen groups advocated for an alternative that incorporated as much of the logging road that goes to the ponds as possible and thus as much Wild Forest designation as possible, citing “reasonable access” for all and promoting the idea of an economic boost from tourism (Access Adirondacks, 2016). Environmental groups advocated for more or all Wilderness classification claiming the ecological importance of the ponds and the attraction potential of hikers (Be Wild, 2015). Beyond these positions lay more nuanced interests and strategies to get a desired classification alternative presented by the APA during public hearings. It is here that framing analysis is particularly useful in providing a deeper examination of positions and interests involved in the conflict.

Frames and framing are a social constructionist concept which views reality as shaped and institutionalized through social interaction (Van Gorp, 2007). Framing is both a cognitive and communicative concept. Cognitively, a frame is a way people interpret and organize life experiences; a filter that we use to navigate complex life situations to fit within our worldviews (Goffman, 1974; Entman, 1993). Frames may also be used to communicate messages in a way to lead to certain logical conclusions; a tool to persuade, negotiate or rally (Entman, 1993; Shmueli, 2008). Frames function by highlighting selected points to expose a particular problem, cause, evaluation or recommendation by resonating with culturally relevant schemas (Entman, 1993; Van Gorp, 2007). Thus, in framing lies the potential to glean a better understanding of the interests and motives of a current position. As frames are particular ways a problem or conflict is presented, they reflect a stakeholder's view of what issues are salient and what outcomes are desired (Davis and Lewicki, 2003).

Framing analysis is a growing methodology and when applied to environmental conflicts, we have the ability to examine current viewpoints as well as past positions and interests open to reframing in the current context (Davis and Lewicki, 2003; Shmueli, 2008; Fletcher and Fletcher, 2016). Thus, utilizing the constructionist tradition of framing analysis we seek to answer several questions: What frames are utilized by stakeholders in the Boreas Ponds tract conflict? How does news media frame the conflict? Finally, what are the dominant frames from both analyses and are there similarities to their presentations of the issue? Through our study of both stakeholder produced materials and news media reporting, we are able to get a more comprehensive picture of the conflict discourse and how the various “sides” are framing their case for how the land should be classified.

Materials and Methods

To examine the conflict over the land classification of the Boreas Ponds tract within the Finch and Pruyn land acquisition, we conducted a framing analysis of (1) stakeholder groups' online presence addressing the conflict and (2) news media coverage of the conflict. Both analyses followed the same general methodology. To examine stakeholder groups' online presence, we used references to stakeholder websites and blogs from newspaper coverage of the conflict as a starting point. From there, we used snowball sampling (i.e., references within the sites to other online material) to expand our dataset. For the media analysis, we used the Google search engine and snowball sampling (i.e., references within the article to other news articles) to capture news coverage coming from local news media. Due to the fact that these newspapers are small with very localized readership, they were not accessible through academic news media databases. Our data collection time period for both analyses was from April 2015 to November 2016, coinciding with the peak of the classification debate. The sampling units for the analyses were the website/blog and news article. Search terms included, “Boreas Ponds,” “news,” “conflict,” “acquisition,” and “classification.” Snowball sampling was concluded once we reached saturation (i.e., ran into repeated stories/online content). At the completion of the sampling process, we collected 32 online stakeholder websites/blogs and 38 newspaper articles.

Once stakeholder groups' online materials and news articles were collected, frames were then inductively constructed for both analyses (see Appendices A and B for the full framing matrices for the online stakeholder group and news media analyses). Our inductive construction of frames was based on the methodology of Gamson and Lasch (1983) and Van Gorp (2007, 2010). Inductive construction was utilized over searching for existing frames in the literature because it embodies the social constructionist view that the audience and media socially develop frames based upon culturally embedded themes and messages (Van Gorp, 2007). With the understanding that frames operate at the cultural level and not the individual, it's supposed that there is a “stock” of frames, some of which may not be included in frames existing in the literature (Van Gorp, 2007). Thus, inductive frame construction allows for the possibility of describing relevant frames to the conflict beyond what may be available in the literature.

Frames were constructed into a “frame matrix” with frames serving as the rows and framing and reasoning devices as the columns (Gamson and Modigliani, 1989; Pan and Kosicki, 1993; Van Gorp, 2010). Frames are manifested through framing devices such as metaphors, catch-phrases, descriptions, arguments, visuals, lines of reasoning, causal connections, exemplars, types of actors, or settings, among others (Van Gorp, 2010). Reasoning devices function as those elements that define the frame (Entman, 1993) and invoke a particular conclusion or line of thinking with a particular frame (Van Gorp, 2010). Framing and reasoning devices help address the content validity of the frame. Construction of the frame matrix itself and identifying frame and reasoning devices utilized the principle of “constant comparison” out of grounded theory (Corbin and Strauss, 1990). For both the stakeholder and media analyses, a representative subsample was initially used to create the frame matrix and was adjusted as further data was added.

To address validity concerns of inductively constructing frames, an intercoder reliability coefficient was calculated for both analyses on half of the sample. A codebook was developed for a second coder to identify frames holistically using yes/ no questions to reduce interpretation and based on previous success on the method (Semetko and Valkenburg, 2000). Cohen's Kappa coefficient (κ) was utilized as the coefficient as it is specifically formulated for two coders and has shown to be generally valid within the literature (Neuendorf, 2002). The Stakeholder analysis intercoder reliability was κ = 0.86 and the media analysis yielded κ = 0.71. Once the intercoder reliability was within acceptable ranges (i.e., κ ≥ 0.7; Neuendorf, 2002), a single coder coded the remaining websites and news articles and finalized the framing matrices, one for stakeholders and one for news media. Finally, we calculated frequencies for the different frames for purposes of comparison.

Results

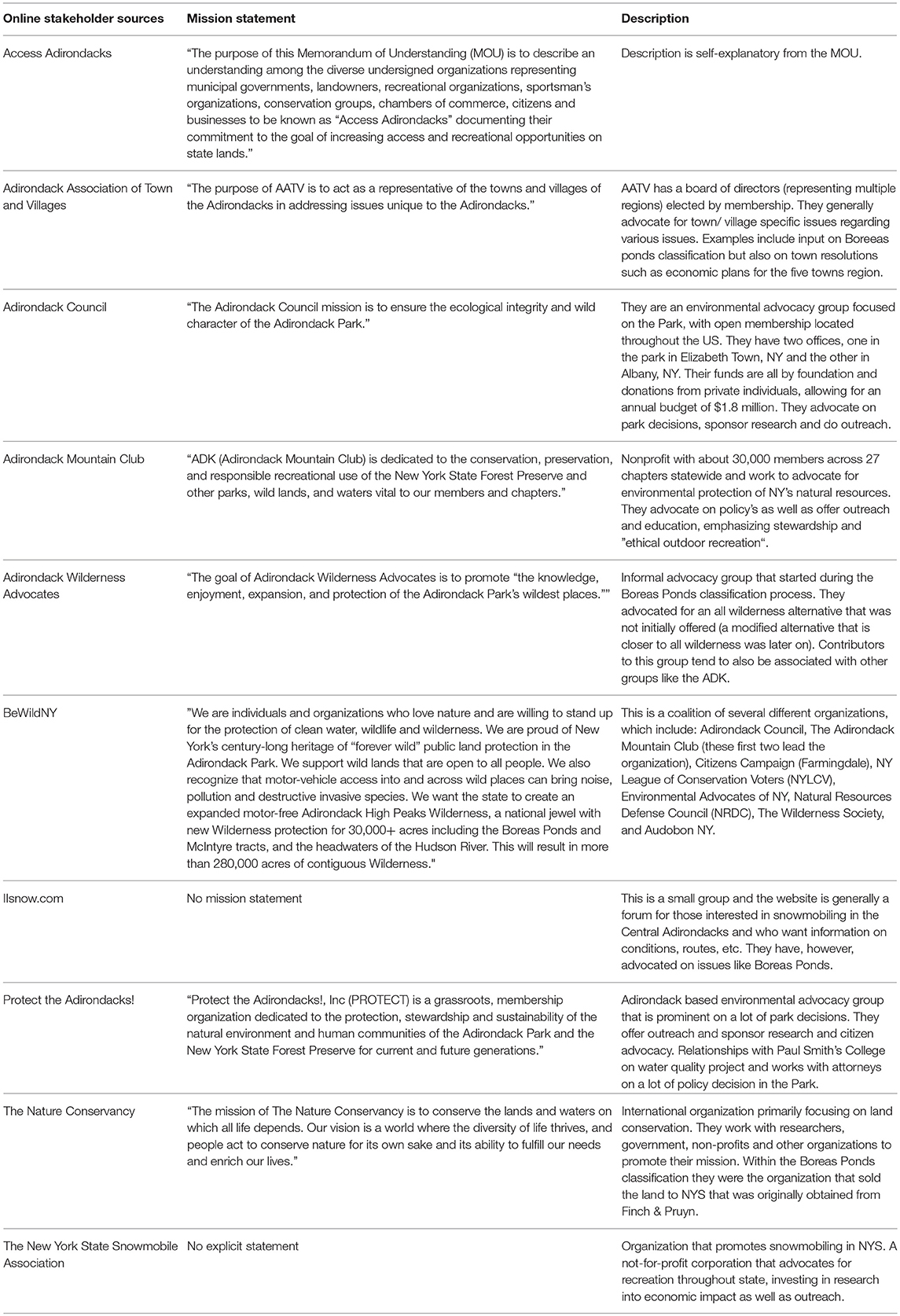

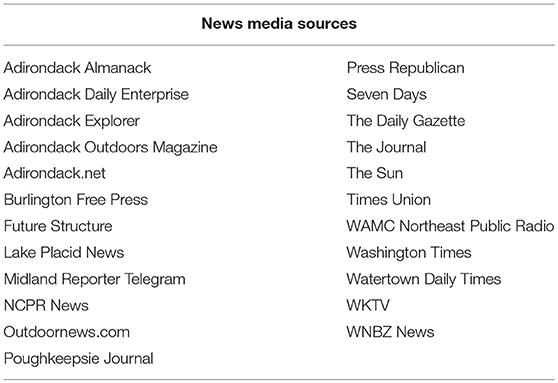

In this section we describe frames emerging from stakeholder groups' online materials and news media articles, pulling from our framing matrices. We also present how often these frames were used in the text and what frames tended to dominate the online and news media discourse. A list of the stakeholder groups and their organization mission statements and descriptions are found in Table 1. A list of news media sources are found in Table 2.

Online Stakeholder Frames

Stakeholders in this conflict generally fell into one or more of the following categories: environmental groups, local organizations/governments, and sportsmen's groups. Within their online text emerged five frames that were utilized among stakeholders: collective action, critical, economy, environmental protection, and reasonable access frames. A majority of online stakeholder pieces (69%) utilized multiple frames when conveying a message. The most commonly combined frames were the collective action frame in conjunction with either the environmental protection frame or reasonable access frame. Considering that the environmental protection frame and the reasonable access frame were considered at odds, the use of the collective action frame in combination with either of these two frames demonstrated a potential mobilizing attempt for one or the other position. Other combinations included the environmental protection frame and the critical frame as well as the environmental protection frame and collective action frames. When in combination, the frames most utilized were environmental protection (37%), collective action (25%), reasonable access (20%), critical (10%), and economy (7%) frames respectively. When competing frames were present together, they consisted of the reasonable access and environmental protection frames (i.e., the two opposing positions). Of the remaining 31% of online stakeholder pieces that only utilized one frame, the environmental protection frame was dominant followed by the reasonable access frame. Descriptions of the frames are as follows.

Environmental Protection Frame

This frame was primarily used by environmental groups and highlighted the preservationist goals of the groups to classify the parcel as wilderness to protect the natural resources within. The prominent theme was that this was the last potential acquisition by the state of this size and would be one of the largest wilderness additions if classified as such. This was seen as important by environmental groups because of the belief that such biodiversity rich places across the state are declining. Lexical choices such as “Expand the Adirondack wilderness,” “sensitive,” “protect,” “gem,” and “ecological integrity” support the frame as well as a common depiction of the parcel being “unique,” “pristine,” and “ecologically sensitive.” Very often, motorized recreation is specifically vilified. The frame appeals to traditional wilderness and preservation ideals and hopes to have a mostly or all wilderness classification.

Collective Action Frame

In the collective action frame, stakeholder groups were utilizing calls of mobilization to forward a goal, in particular, to communicate a specific alternative or present comments to create a new alternative. Indicators of use of this frame primarily included explicit calls to contact the APA to participate in their process through their open comment period. Sometimes this would even include a premade email form where someone can choose to edit the message before sending it along to the APA. The latter was mostly used by environmental groups such as the Adirondack Wilderness Advocates. Lexical choices that supported the frame included the use of terms such as “encourage,” “urge,” “attend,” and “take action.” Often, the Boreas Pond tract was depicted quite differently based on who utilized the frame, but what was common was the depiction that the parcel will have a dramatic effect based on classification—whether that be economic impacts or impacts on preservation. This frame appeals to principles of civic duty to participate in a public process and to act for good, which again will vary based on which position utilized the frame.

Reasonable Access Frame

The reasonable access was a frame primarily used by town organizations/governments. This frame is defined by the argument that the parcel was purchased with NYS tax dollars and thus should be accessible to as many New Yorkers as possible, in particular, the disabled and elderly. Concerns of exclusion were prominent in some press releases, sometimes referencing prior purchases that were classified as wilderness despite resident wishes. Lexical choices of rights and access were frequent as terms like “reasonable access,” “right of every New Yorker…,” and “rightful public access” appear. Similar to the economy frame noted below, Boreas Ponds is depicted as not wilderness by APAs definition and containing infrastructure to support access already. The frame seeks to appeal to rights of citizens to get a more accessible alternative.

Critical Frame

This frame was defined by criticism toward the decision-making process or the state agencies themselves. The critique of the process was that it didn't accurately represent all the potential alternatives and thus views and perspectives involved. This frame is supported by lexical choices indicating direct criticism such as “…APA fails to reject…” and “…reject flawed classification.” Exemplars include press releases that target the APA by name directly and in particular from environmental groups who wished to see an all wilderness classification alternative, which was not offered in the DSEIS. The main issue highlighted in this frame was the belief that the APA was not operating under its own auspices correctly by failing to represent all possible alternatives. This frame appeals to calls to action to persuade the APA to add a new alternative.

Economy Frame

This frame was utilized to imply a large economic potential depending on the classification of the parcel. The local surrounding towns' struggling economies and large dependence on tourism dollars are the focus. This frame was predominately used by the town and resident groups such as Access Adirondacks. The frame was supported by press releases emphasizing the economic potential to the towns if the parcel offered a large variety of recreational activities. Lexical choices included references to “revenue” and “community prosperity.” Boreas Ponds in particular was often depicted as a parcel managed previously by Finch and Pruyn and not conforming to traditional wilderness standards of the APA. This frame appealed to others for help for their struggling economies and pushes for one of the presented alternatives that have more motorized classification scheme.

News Media Frames

We identified three frames from news media's representation of the conflict with only partial overlap with frames from the online stakeholder materials. News media frames included an advocate frame, which was further divided into a wilderness advocate frame and an access advocate frame, essentially the two opposing positions in the classification conflict. The other two frames included a conflict frame and a critical frame. Unlike the stakeholder groups' online text, news media tended to use a single frame in their articles (71%). The most frequently used frame was the conflict frame (38%) followed by wilderness advocate (26%), access advocate (20%), and critical frames (16%). Of the 29% of news articles that used more than one frame, the most frequently used combination was the wilderness advocate and critical frames followed by the wilderness advocate, conflict, and critical frames. There seemed to be a balanced presentation of the conflict frame with the two advocate sub-frames. Descriptions of the frames are as follows.

Conflict Frame

This frame was the most common among news articles about the Boreas Ponds. It was defined by presenting the classification process as fundamentally intractable, often presenting stakeholders as different sides in a battle or “clash.” Terms like “controversy,” “army,” “heated,” and “contentious” were frequently used in the articles. Quotes used, regardless of stakeholder position, were often negative in tone and divisive. Preservation and development/motorized access were depicted as mutually exclusive. The core issue is that there was no room for compromise and no easy solution, appealing to the principle that environmental and business goals were completely incompatible. Exemplar articles often explicitly expressed an expectation of contention and continued criticism of the APA, as the decision was likely to make a large group of people upset and often contained a tone of pessimism.

Advocate Frame: Wilderness Sub-Frame

Again, this frame advocates a position, however, this one was dominated by preservationist ideals and wilderness protection. News media utilized this frame often to depict Boreas Ponds as pristine wilderness that needed “protection” and is a “treasure” needing to be “preserved.” Environmental group representatives were often quoted, and descriptions and photos of the tract's natural features were highlighted, especially the ponds themselves. This frame usually highlighted the unique potential for remote and quiet recreation, which is deemed rare and as something that should be expanded. Also of note was that science was often used in these articles to support environmental group positions. Finally, motorized recreation was often specifically portrayed as damaging, and appeals to the parcel's wilderness character were used to advocate a more restrictive alternative.

Advocate Frame: Access Sub-frame

The advocate frame in general was the news media's presentation of a particular advocacy position. The access sub-frame in particular was defined by a dominant theme of reasonable access, much like the corresponding frame in the stakeholder analysis. News media frequently used terms such as “reasonable access” but were also coupled with terms like “desperate” and “dependent on tourism,” highlighting the economic need of the nearby towns. These articles often highlighted difficult access with the NYSDEC's interim plan, the multi-use potential of the parcel and often quoted local sportsmen clubs and town authorities.

The main issue presented by news media was the economic state of the local communities, depicting the towns in rough economic shape and that previous land classifications have been deemed exclusive. It was argued that land should be accessible to more taxpayers and recreational activities, in particular, motorized sports such as snowmobiling. There were also appeals to inclusiveness as the frame promoted more accessible classification through its calls for equitable access opportunities.

Critical Frame

This frame was similar to the critical frame in the stakeholder analysis. News media, when invoking this frame, highlighted problems with the classification process itself and/or the state agencies involved. Frequently, term definitions were called into question, such as the APA's definition of Wilderness and how the process did not reflect its legal definition (noted above in the introduction). Headlines often highlight tensions caused by the agency such as the more explicit, “APA fails to end criticism over Boreas Ponds options.” Other common examples of APA criticism included “We need more alternatives…” and “didn't take into consideration.” The line of reasoning, as presented by the news media, was that the APA was damaging the land by not offering preferred alternatives (often all Wilderness) or being exclusionary by not classifying based on its own legal definitions of Wilderness. Furthermore, there was an appeal to be fair and impartial with a push to highlight the need for more alternatives.

Discussion

From the stakeholder framing analysis, several key points emerge, the most salient being the debate of motorized access to the Boreas Ponds. Local groups such as Access Adirondacks used frames such as reasonable access and economy to garner support from others by expressing inclusiveness as a way to ensure as many tax-paying New Yorkers can access the parcel as well as helping to support economies reliant on tourism. Environmental groups such as the Be Wild NY coalition, on the other hand, argued that as much of the area as possible should remain motor-free due to ecologically important ponds, and the opportunity to provide remote and quiet recreation in what they claim to be pristine wilderness. The dominance of the environmental protection frame reflects the large environmental community involved in the Adirondack Park. Access Adirondacks is the only formal organization to represent local interests in the classification process. Local communities in the Park have often felt marginalized in many land management decisions, overshadowed by environmental interests (Vidon, 2016). Anxiety over previous wilderness classifications was expressed through releases using the reasonable access frame over concerns on how that classification for Boreas Ponds would exclude the elderly, handicapped, and those unable to participate in backcountry activities. Such framing plays on what Haidt (2003) calls moral emotions which are emotions “that are linked to the interests or welfare of either a society as a whole or at least of persons other than the agent.”

Angman et al. (2016), writing about the legitimacy of emotions in natural resources management, add to this concept of moral emotions by discussing how emotions may or may not be considered legitimate in a decision-making process based on stakeholder perceptions of what is considered socially appropriate. In this case, Access Adirondacks was using moral emotion in the form of inclusivity for all park-goers, whereas organizations such as Be Wild NY promoted the ecological importance of the region and its preservation for the future. Both can be considered moral emotional frames due to their appeals to the social good. Specifically for organizations speaking for local communities, appeals to inclusivity expanded their framing of the issue beyond local economic interests to this being an issue for all who want access to tracks of land in the Park. Thus, as a result of how this issue of land classification is being framed, these values of environmental preservation and inclusiveness are often pitted again one another, emphasizing incompatibility over compromise. This is highlighted by the heavy usage of the collective action frame by stakeholder groups. Webpages and press releases evoking the collective action frame often used terms of urgency and saliency as they urged the public to attend the meetings to voice their message. To some degree, this may have been effective due to the fact that the APA had to change venues for their public meetings because of increased attendance (APA, 2016).

The critical and economy frames are utilized but not nearly as often, highlighting the fact that the core of the conflict for stakeholders was access to the resource. The critical frame was invoked when wilderness advocates criticized the APA for not presenting an option that would classify the land as entirely Wilderness, a more one-sided option than any of the alternatives presented, indicating disagreement even among wilderness advocates about how the land should be classified. The critical frame was also used by those who advocated access by highlighting the APA's definition of Wilderness and how the tract does not conform to the definition due to existing structures (refer back to Wilderness definition in the introduction; see citation link for full definition). As Peterson and Feldpausch-Parker (2013, p. 515) note, “The public expects government decision makers to represent the public interest and to protect the public good when addressing environmental resource issues. When the public perceives that this has not occurred, dissatisfaction arises.” Thus, some stakeholder groups made it known that they felt their views were not represented in the process and made a point to contest the parameters of the process led by the NYSDEC and APA.

Unlike the stakeholder analysis, news media used a few select frames in their reporting of the classification conflict. One place where they overlapped the most with the stakeholder content was news media's use of the critical frame. They also had relating content in their advocacy frame to the stakeholders' collective action and positional frames. Further differences between the two analyses were that news media utilized the critical frame much more often and only in conjunction with the wilderness advocate sub-frame. The main criticism, as reported in the articles, was of the APA's decision to exclude an all-Wilderness alternative. The decision-making process became the point of blame as the conflict grew to encompass more than just the land classification. This piece is particularly interesting as the APA in the past has received praise from environmental groups while drawing the ire of local businesses as their decisions tended to be more restrictive (Terrie, 2008). Even more interesting was the public separation of one group, Adirondack Wild, from the Be Wild NY coalition because it wanted to see an all-Wilderness classification while the rest of Be Wild NY was advocating one of the APA proposed alternatives (Brown, 2016). As implied within the stakeholder analysis, there was disagreement even within environmental groups. This supports previous work indicating that conflict, especially involving environmental disputes, may be more nuanced than just environmental groups against industry/business/motorized recreation (Parker and Feldpausch-Parker, 2013). In these situations, stakeholders within groups may frame situations differently (Brummans et al., 2008), framing the issue as a problem within the decision-making process.

The most notable difference between the two analyses was the news media's consistent use of the conflict frame, which appeared more often than any other frame. Framing different stakeholders as adversaries and the process more like a battle than a decision-making process left no room for compromise or common ground for vested parties. From a theoretical perspective, this negative framing of conflict is typical, but limiting because it does not account for the constructive elements of conflict such as the encouragement of democratic debate by stakeholders who have dissenting opinions on an issue, but at the same time are given voice in a decision-making process (Mouffe, 2005; Hallgren, 2016). As noted above, the fact that stakeholder groups used the collective action frame for both positions is a constructive example of encouraging people to participate in deliberative democracy. News media, however, chose to focus on the destructive elements of conflict by frequently referencing negative quotes from different stakeholder groups and focusing on disagreement and incompatibility over potential areas of compromise or collaboration. For instance, any alternative designation requires a Unit Management Plan (UMP), which could regulate the use of motor vehicles in terms of access and location. News articles utilizing this frame painted any form of commonality between stakeholders as unlikely.

Conclusion

While at first blush appearing as simple as the age-old development vs. environment debate, the Boreas Ponds conflict cannot be reduced to such a clear dichotomy. Rather, frame analysis reveals a much more nuanced and interwoven set of histories, social relations, and interactions with the landscape that result in complex articulations of voice, agency, and experience in this contested terrain (Terrie, 2008). Furthermore, the Adirondack Park may very well serve as the model for future park creation in the US with its mixed-use landscape comprised of both public and private lands. The series of frames used reveal different parts of these histories, voices, and experiences, thus illuminating the hopes and the apprehensions of multiple groups. For instance, the reasonable access frame reveals fears of exclusion based on a history of previous acquisitions along with hopes for a potential break from economic struggles, while the environmental protection frame highlights preserving a large tract of land in a world where large purchases for preservation are less and less viable. Adding to the complexity of hopes and apprehensions based on multiple histories, the process itself is scrutinized. With the utilization of the critical frame from both media and stakeholders, there is an indication that the APA may not be incorporating all possible views in its decision-making process, thus leading to heightened mistrust in the State and skepticism in the integrity of the process. With a difficult history between the State, residents, and tourists in the Park (Vidon, 2016), trust in the process is key for success moving forward. Establishment of the Common Grounds Alliance (CGA) has moved this trust forward significantly from where it was in the 1970s, but trust is a delicate thing that is easily eroded in times of stress. Adding to the difficulty, the media's presentation of the process as a conflict only further polarizes the issue, discursively constructing it as something “negative” instead of something that has the potential to move communities and landscapes forward in a positive way. With these discursive mechanisms firmly entrenched, the debate anchors itself in pre-existing issues and pre-established alternatives while silencing and marginalizing stakeholder voices and thus the scope of their interests. Tensions may certainly remain given the nature of the decision-making process, even though a decision has been reached. The APA relies on a traditional method of involving the public through environmental impact review, which is the public hearing and written comment period under SEQRA. From the comments and the public hearings, the APA and NYSDEC work to either choose one of the DSEIS alternatives or form a new one to be presented in the FSEIS. This limits input from stakeholders to either a letter and/or a few minutes in a public meeting. This form of engagement over environmental conflict has demonstrated to instill distrust and frustration for stakeholders (Walker et al., 2006; Clarke and Peterson, 2016).

Update: In February 2018, the APA voted 8-1 to split the Boreas Ponds tract into two main classifications, Wilderness and Wild Forest, making lands north of the logging roads Wilderness, including the ponds, and those south of the roads Wild Forest (Brown, 2018a). The APA's decision was approved by New York State Governor Andrew Cuomo a month later (Brown, 2018b).

Author Contributions

This manuscript is the result of CS's thesis research with assistance from her committee: AF-P, EV, and IP. The concept and study design behind this project was the combined effort of CS and AF-P. Data collection and analysis was completed by CS. Writing of the manuscript was a collaborative effort by CS, AF-P, EV and IP.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Theodora Greene Weatherby for her assistance with intercoder reliability testing.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fcomm.2018.00042/full#supplementary-material

References

Access Adirondacks (2016). Classify Boreas Ponds and Macintyre Tracts Wild Forest. Available online at: http://www.accessadk.com

Adirondack Park Agency (APA) (2016). Adirondack Park State Land Master Plan. New York, NY: Adirondack Park Agency.

Angman, E., Buijs, A. E., Arts, I., Ljunggren Bergea, H., and Verschoor, G. (2016). “Communicating emotions in conflicts over natural resource management in the Netherlands and Sweden in Peterson,” in Environmental Communication and Community: Constructive and Destructive Dynamics of Social Transformation, eds T. R. H. Ljunggren Bergea, A. M. Feldpausch-Parker, and K. Raitio (New York, NY: Earthscan from Routledge), 16–29.

Be Wild, NY. (2015), November 9). About us. Available online at: http://bewildnewyork.org/ about-us/

Brown, P. (2014). Update on Recent NYS Land Purchases. The Adirondack Almanack. Available online at: https://www.adirondackalmanack.com/2014/05/update-on-recent-state-land-acquisitions.html

Brown, P. (2016). State Buys Boreas Ponds, Completing Finch, Pruyn Deal. Available online at: http://www.adirondackalmanack.com/2016/04/59863.html

Brown, P. (2018a). APA approves Boreas Ponds Classification. Adirondack Explorer. Available Online at: https://www.adirondackexplorer.org/outtakes/apa-approves-boreas-ponds-classification

Brown, P. (2018b). Cuomo Approves Boreas Ponds Classification. Adirondack Explorer. Available online at: https://www.adirondackexplorer.org/news_releases/boreas-ponds-classification

Brummans, B. H. J. M., Putnam, L. L., Gray, B., Hanke, R., Lewicki, R. J., and Wiethoff, C. (2008). Making sense of intractable multiparty conflict: a study of framing in four environmental disputes. Commun. Monogr. 75, 25–51. doi: 10.1080/03637750801952735

Clarke, T., and Peterson, T. R. (2016). Environmental Conflict Management. Los Angeles, CA: Sage Publications.

Corbin, J. M., and Strauss, A. (1990). Grounded theory research: procedures, canons, and evaluative criteria. Qualitative Soc. 13, 3–21. doi: 10.1007/BF00988593

Davis, C. B., and Lewicki, R. J. (2003). Environmental conflict resolution: framing and intractability—an introduction. Env. Pract. 5, 200–206. doi: 10.1017/S1466046603035580

Entman, R. M. (1993). Framing: toward clarification of a fractured paradigm. J Commun. 43, 51–58. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-2466.1993.tb01304.x

Fletcher, A. L., and Fletcher, A. L. (2016). Clearing the air : the contribution of frame analysis to understanding climate policy in the United States climate policy in the United States. Environ. Pol. 18, 800–816. doi: 10.1080/09644010903157123

Gamson, W. A., and Lasch, K. E. (1983). The political culture of social welfare policy. Eval. Welfare State Soc. Politi. Persp. 95, 397–415. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-657980-2.50032-2

Gamson, W. A., and Modigliani, A. (1989). Media discourse and public opinion on nuclear power : a constructionist approach. Univer. Chicago 95, 1–37. doi: 10.1086/229213

Goffman, E. (1974). Frame Analysis: An Essay on the Organization of Experience. Boston, MA: Northeastern University Press.

Haidt, J. (2003). “The moral emotions,” in Series in Affective Science. Handbook of Affective Sciences, eds R. J. Davidson, K. R. Scherer, and H. H. Goldsmith (New York, NY: Oxford University Press), 852–870.

Hallgren, L. (2016). “Reframing conflict in natural resource management: mutuality, reciprocity and pluralistic agonism as dynamics of community constructivity and destructivity in Peterson,” in Environmental Communication and Community: Constructive and Destructive Dynamics of Social Transformation, eds T. R. H. Ljunggren Bergea, A. M. Feldpausch-Parker, and K. Raitio (New York, NY: Earthscan from Routledge), 16–29.

Hecht, S., and Cockburn, A. (1990). The Fate of the Forest: Developers, Destroyers and Defenders of the Amazon. New York, NY: HarperCollins.

Neumann, R. (1998). Imposing Wilderness: Struggles Over Livelihood and Nature Preservation in Africa. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

New York State Department of Environmental Conservation (NYSDEC) (2016). Acquisition of Former Finch Pruyn Lands. Available online at: http://www.dec.ny.gov/lands/42077.html

New York State Department of Environmental Conservation (NYSDEC) (2018a). State Land Classifications: Wilderness. (Accessed 15 June, 2018). Available online at: https://www.dec.ny.gov/lands/7811.html#A_Wilderness

New York State Department of Environmental Conservation (NYSDEC) (2018b). State Land Classifications: Wild Forest. Accessed 15 June, 2018. Available online at: https://www.dec.ny.gov/lands/7811.html#B_Wild_Forest

Pan, Z., and Kosicki, G. (1993). Framing analysis: an approach to news discourse. Polit. Commun. 10, 55–75. doi: 10.1080/10584609.1993.9962963

Parker, I. D., and Feldpausch-Parker, A. M. (2013). Yellowstone grizzly delisting rhetoric: an analysis of the online debate. Wildlife Soc. Bull. 37, 248–255. doi: 10.1002/wsb.251

Peterson, T. R., and Feldpausch-Parker, A. M. (2013). “Environmental conflict communication,” in The SAGE Handbook on Conflict Communication: Integrating Theory, Research, and Practice, 2nd Edn, eds J. G. Oetzeland and S. Ting-Toomey (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications,), 513–535.

Porter, W., Erickson, J., and Whaley, R. (2009). The Great Experiment in Conservation: Voices From the Adirondack Park. Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press.

Semetko, H. A., and Valkenburg, P. M. (2000). Framing european politics. a content analysis of press and television news. J. Commun. 50, 93–1009. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-2466.2000.tb02843.x

Shmueli, D. F. (2008). Framing in geographical analysis of environmental conflicts: theory, methodology and three case studies. Geoforum 39, 2048–2061. doi: 10.1016/j.geoforum.2008.08.006

Terrie, P. (2008). Contested Terrain: A New History of Nature and People in the Adirondacks, 2nd Edn. Blue Mountain Lake, NY: The Adirondack Museum.

Tohamy, S., and Swinscoe, A. (2014). The Economic Impact of Tourism in New York Adirondacks Focus. Available online at: http://nmtourism.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/NM-Visitor-Economic-Impact-2014-w-counties.pdf

Van Gorp, B. (2007). The constructionist approach to framing: bringing culture back in. J. Commun. 57, 60–78. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-2466.2006.00329.x

Van Gorp, B. (2010). “Strategies to take subjectivity out of framing analysis,” in Doing News Framing Analysis: Empirical and Theoretical Perspectives, eds P. D'Angelo and J. A. Kuypers (New York, NY: Routledge), 113–143.

Vidon, E. (2016). “The call of the wild: power and ideology in the Adirondack Park,” in Political Ecology and Tourism, eds S. Nepal and J. Saarinen (New York, NY: Routledge), 100–114.

Vidon, E. (2017). Why wilderness: alienation, authenticity, and nature. Tourist Stud. doi: 10.1177/1468797617723473. [Epub ahead of print].

Keywords: Adirondack State Park, conflict, framing analysis, media, stakeholders, wilderness, land classification

Citation: Sandrow CA, Feldpausch-Parker AM, Vidon ES and Parker ID (2018) Anything but a Walk in the Park: Framing Analysis of the Adirondack State Park Land Classification Conflict. Front. Commun. 3:42. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2018.00042

Received: 13 July 2018; Accepted: 03 September 2018;

Published: 25 September 2018.

Edited by:

Michael J. Liles, The University of Texas at El Paso, United StatesReviewed by:

Shawn Kyle Davis, Slippery Rock University of Pennsylvania, United StatesSamantha Senda-Cook, Creighton University, United States

Copyright © 2018 Sandrow, Feldpausch-Parker, Vidon and Parker. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Andrea M. Feldpausch-Parker, YW1wYXJrZXJAZXNmLmVkdQ==

Cheryl A. Sandrow

Cheryl A. Sandrow Andrea M. Feldpausch-Parker

Andrea M. Feldpausch-Parker Elizabeth S. Vidon

Elizabeth S. Vidon Israel D. Parker2

Israel D. Parker2