- School of Material Science and Chemical Engineering, Institute of Drug Discovery Technology, Ningbo University, Ningbo, China

Metal-iodosylarene complexes have been recently viewed as a second oxidant alongside of the well-known high-valent metal-oxo species. Extensive efforts have been exerted to unveil the structure-function relationship of various metal-iodosylarene complexes. In the present manuscript, density functional theoretical calculations were employed to investigate such relationship of a specific manganese-iodosylbenzene complex [MnIII(TBDAP)(PhIO)(OH)]2+ (1). Our results fit the experimental observations and revealed new mechanistic findings. 1 acts as a stepwise 1e+1e oxidant in sulfoxidation reactions. Surprisingly, C-H bond activation of 9,10-dihydroanthracene (DHA) by 1 proceeds via a novel ionic hydride transfer/proton transfer (HT/PT) mechanism. As a comparison to 1, the electrophilicity of an iodosylbenzene monomer PhIO was investigated. PhIO performs concerted 2e-oxidations both in sulfoxidation and C-H activation. Hydroxylation of DHA by PhIO was found to proceed via a novel ionic and concerted proton-transfer/hydroxyl-rebound mechanism involving 2e-oxidation to form a transient carbonium species.

Introduction

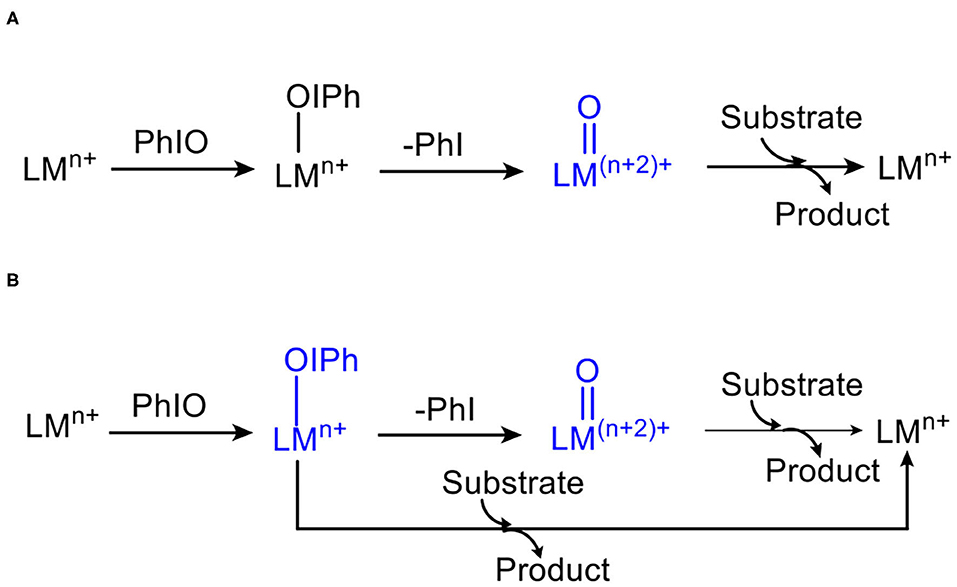

Iodosylarenes have been frequently employed as terminal oxidants in the synthesis of metal-oxo species, as well as in the catalytic oxidation of organic substrates including C–H hydroxylation and O-atom transfer to substrates (Zhdankin and Stang, 2002, 2008; Yoshimura and Zhdankin, 2016). Generally, the insoluble iodosylarenes bind to an heme or non-heme metal core and produce the metal-iodosylarene complexes (Scheme 1A) (Macikenas et al., 2000). Such metal-iodosylarene intermediates are unstable and ready to cleave into high-valent metal-oxo species and iodoarenes. The nascent high-valent metal-oxo species are believed to be the sole oxidants in the various oxygenation reactions (Groves et al., 1979; Groves and Nemo, 1983). Extensive experimental observations support this one-oxidant mechanism, which becomes a widely accepted mechanism in oxygenation chemistry (Shaik et al., 2005). However, in the 1990s, Valentine and co-workers found that epoxidation of olefin was significantly enhanced when redox-innocent metals were added in the oxidation system involving idosylbenzene (Nam and Valentine, 1990; Yang et al., 1990). This experimental result drops the one-oxidant mechanism into doubt. In 2000, Collman, Brauman and co-workers reported the oxidation rate ratios for each pair of substrates varied when different iodosylarenes were employed as terminal oxidants (Collman et al., 2000). In 2002, Nam and co-workers suggested that the ratio of stereoisomers in olefin epoxidation reactions catalyzed by porphyrin iron complex depended on the terminal oxidant or counterions, and proposed the multiple-oxidant mechanism (Scheme 1B) (Nam et al., 2002). In this mechanism, both metal-iodosylarene adducts and high-valent metal-oxo complexes are potential oxidants to oxidize the substrates to the products. Nam and co-workers have presented various spectroscopic (UV-Vis, Raman, etc.) and enantioselectivity evidences to support this mechanism (Hong et al., 2014; Wang et al., 2015).

Many evidences supporting the multiple-oxidant mechanism also come from other famous groups. Hill et al. reported iodosylbenzene adducts of a manganese porphyrin complex trans-[MnIV(por)(OI(OAc)Ph)2] as a precursor to active high-valent manganese–oxo species (Smegal and Hill, 1983). Fujii and his workers crystalized another Mn(IV)-iodosylarene complex trans-[MnIV(salen)(MesIO)2Cl]+ (Wang et al., 2012), and clarified that the reactivity and selectivity of iodosylarene adducts depended on steric and electronic properties of substituents on iodine(III) of the coordinated iodosylarenes (Wang et al., 2013). The spectroscopic evidence for a manganese iodosylarene porphyrin adduct [Mn(TDCPP)(ArIO)]+ was also reported by Lei (Guo et al., 2012). Meanwhile, other metal-iodosylarene complexes with different metals have been crystalized, such as the iron complex [FeIII(tpena)(OIPh)]+ by Mckenzie (Lennartson and Mckenzie, 2012), the rhodium complex [RhIIICp*(ppy)(sPhIO)]+ by Templeton (Turlington et al., 2014), and the cobalt complex [CoIITptBu(sPhIO)]+ by Anderson (Hill et al., 2018). In addition to normal transition-metal complex, the lanthanide complexes, the Ce-iodosylbenzene one [CeIV(LOEt)2(OI(Cl)Ph)2] and the Ce-iodylbenzene one [CeIV(LOEt)2(OI(O)ClPh)2] were reported by Leung et al. (Au-Yeung et al., 2016).

Recently, Cho and his co-workers crystallized the first X-ray crystal structure of a mononuclear manganese-iodosylarene complex, [MnIII(TBDAP)(OIPh)(OH)]2+ (1, TBDAP = N, N-ditert-butyl-2,11-diaza-[3.3](2,6)-pyridinophane), which is capable of conducting various oxidation reactions, such as C–H bond activation, sulfoxidation, and epoxidation (Jeong et al., 2018). In these reactions, 1 exhibits similar and even higher electrophilic oxidation power comparing to highly reactive manganese(IV)-oxo complexes. A consecutive Mn(III)(OIPh)(OH)/Mn(IV)(OH)2 conducting mechanism (Jeong et al., 2018) was proposed for the hydrogen abstraction reactions and a direct oxygen atom transfer mechanism (DOT) (Li et al., 2007; Shaik et al., 2010) was postulated for the sulfoxidation and epoxidation reactions. However, no further theoretical study is performed to support such mechanism. Herein, we presented the first theoretical investigation to the structure-reaction relationship of 1 shown in oxidative C-H bond activation and sulfoxidation. Our results demonstrate that such Mn(III)-OIPh complex 1 prefers to be stepwise 1e+1e oxidant in sulfoxidations, oxygen transfer occurs via the electron transfer followed by oxygen transfer (ETOT) mechanism proposed by Watanabe and Baciocchi (Goto et al., 1999; Baciocchi et al., 2003), not the DOT mechanism. Surprisingly, in the C-H bond activation mediated by 1, a new ionic hydride transfer/proton transfer (HT/PT) mechanism is preferred (Li et al., 2016; Geng et al., 2017, 2019; Schwarz et al., 2017).

Theoretical Methods

Coordinates of [MnIII(TBDAP)(OIPh)(OH)]2+ was obtained from the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Center with deposition number CCDC-1868139. Thioanisole and 9,10-Dihydroanthracene (DHA) were employed as the substrates in the mechanistic study of sulfoxidation and C–H bond activation, respectively. Density functional theory (DFT) calculations were carried out using the Gaussian 16 suite of quantum chemical programs (Frisch et al., 2016). The spin-unrestricted functional B3LYP-D3(BJ) (Becke, 1992a,b, 1993) with the addition of Grimme's D3 dispersion and Becke–Johnson damping (Grimme et al., 2010, 2011) was used. Such functional has been extensively verified to be accurate and efficient in many transition metal-containing reaction systems (Yang et al., 2016, 2019). Two mixed basis sets were carried out: (1) geometry optimizations and frequency calculations were performed with a set of basis set of Lanl2dz for Mn, Lanl2dzdp for I, 6-31G* for S, 6-31G** for the first coordinating moieties PhIO(I is excluded)/OH and 6-31G for the rest atoms. This basis set is denoted as B1 for simplicity. The benchmark on the other DFT functionals was added into the Supporting Materials. The validity of the functional B3LYP was evaluated by comparison with calculations that employed four other functionals: PBE0 (Adamo and Barone, 1999), B3PW91 (Kaupp et al., 2002), M06 (Zhao and Truhlar, 2008), and BP86 (Perdew, 1986), which are widely used in transition metal model systems. The hybrid DFT functionals (PBE0, B3PW91, M06) show consistent results with B3LYP (Supplementary Table S3). (2) Single point energy (SPE) calculations were done with the basis set of Lanl2tz for Mn, Lanl2dzdp (Hay and Wadt, 1985; Isaia et al., 2009; Jaccob et al., 2011) for I and 6-311+G** for the rest atoms. Basis sets lanl2dzdp and lanl2tz were obtained from the Basis Set Exchange library (Feller, 1996; Schuchardt et al., 2007). All geometries were optimized without any symmetry constraints. Solvent effects (acetonitrile, ε = 35.688) were included in all calculations using the conductor-like polarizable continuum model (CPCM) (Barone and Cossi, 1998; Cossi et al., 2003) as implemented in Gaussian 16. An experimental temperature of 293.15 K was adopted in the Gibbs free energy calculations. Transition states were ascertained by vibrational frequency analysis to possess a mode along the reaction coordinate with a sole imaginary frequency. The energy values in the text were calculated at the SPE/B2//B1+ZPE(B1) level. Energy values at other computing levels are presented in the Supporting Materials.

Result And Discussion

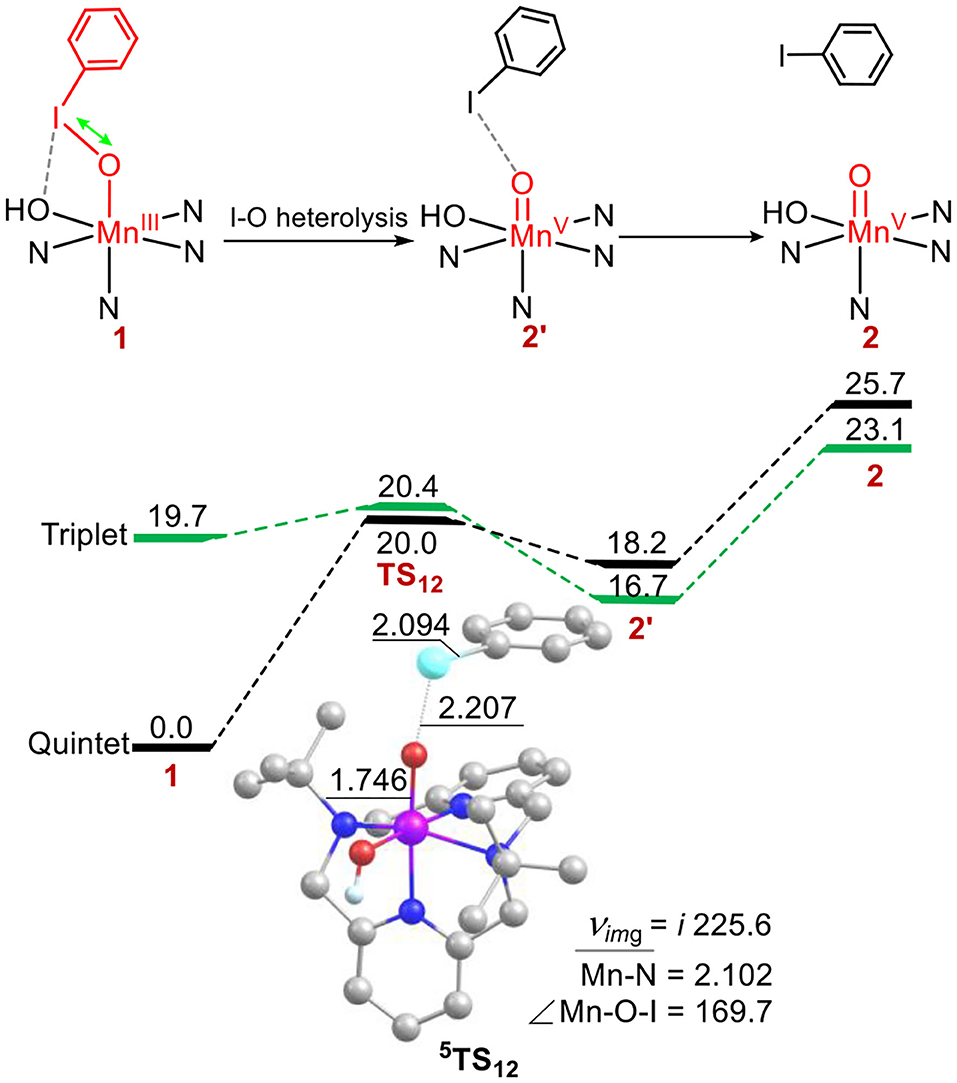

Conversion of the Manganese(III)–Iodosylarene Complex 1 to the High-Valent Manganese(V)-oxo Complex 2

First, the conversion from 1 to high-valent metal-oxo species 2 in the absence of substrates was investigated (Figure 1). For 1, the ground state is a high-spin quintet states (S = 2), the exited triplet/singlet spin states lie at 19.7/46.9 kcal/mol higher. Various SCF and free energies of the reactant on singlet state (S = 0) was found to have high energy throughout the reaction, Thus, the singlet state pathway was ruled out. For the ground state 51, the average distance of Mn-N is 2.202 Å, the distance of Mn-OIPh is 1.904 Å, the I-O distance is 1.938 Å, and the length of twisted T-shape halogen bond I-OH is 2.689 Å, which is consistent with Cho's experiment (Jeong et al., 2018). For the transition states 3, 5TS12, the energies is degenerate. 5TS12 lies 20.0 kcal mol−1 higher than 51, and 3TS12 only lies 0.4 kcal mol−1 above 5TS12. For the low-lying 5TS12, the calculated Mn-O distance is 1.746 Å, the I-O one is 2.207 Å, and the I-OH one is 4.592 Å (For 51, the length is 2.689 Å), indicating that the halogen bond between I and OH for 51 is broken on the transition state and thus raises the activation energy (Liu et al., 2016). The formed high-valent Mn(V)-oxo complex on the triplet ground state 32′ lies 16.7 kcal mol−1 higher than the quintet manages(III)-iodosylarene complex 51. For 32′, the Mn–O distance is 2.642 Å, indicating that I-O bond is still not completely broken and has a strong interaction. Such high-valent MO–iodine interaction was also found in the conversion of the iron(III)-PhIO complex Fe(III)(O)(tpena)-OIPh to the high-valent iron-oxo species Fe(V)(O)(tpena) (Lennartson and Mckenzie, 2012). To obtain a non-PhI-interacting Mn(V)(O)(TBDAP) complex 2 from 2′, an additional energy of 6.4 kcal mol is required (Figure 1). In short, conversion of the quintet complex (TBDAP)Mn(III)-OIPh to the high-valent species Mn(V)(O)(TBDAP) is a process of two-state reactivity (TSR) (Shaik et al., 1998, 2002; Ogliaro et al., 2000). The halogen bond between the iodine atom and the OH ligand is broken during the conversion, making such conversion kinetically and thermodynamically unfeasible.

Figure 1. Energy profiles (in kcal mol−1) for the conversion of manganese(III)–iodosylbenzene 1 to oxo-manganese(V) 2. Energies were calculated at the UB3LYP-D3(BJ)/B2//B1+ZPE/B1 level in solvent. The geometric information of the transition state 5TS12 is presented. Hydrogen atoms are omitted for clarity. Lengths are in Å units, angles are in degree units, and the imaginary frequency is in cm−1 unit.

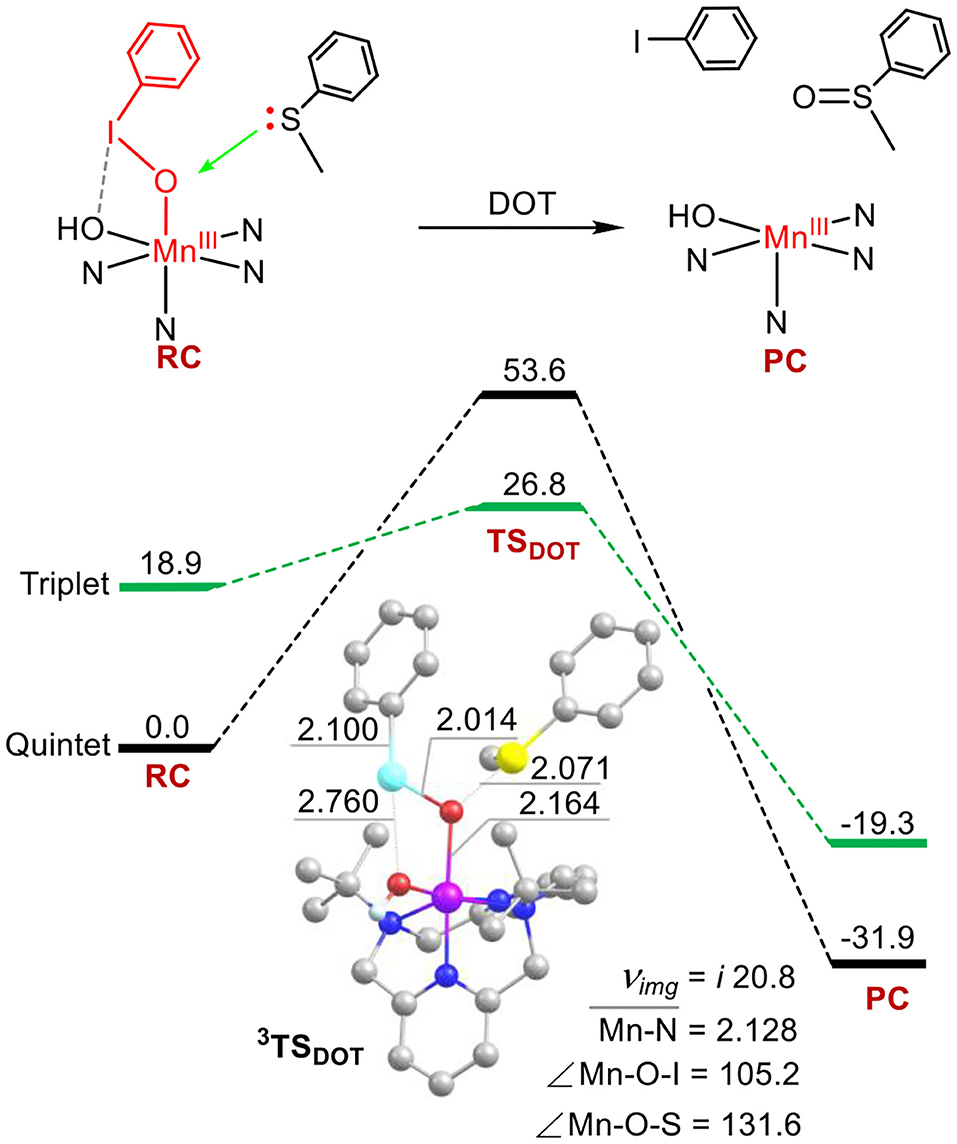

Sulfoxidation of Thioanisole by 1 via the Direct Oxygen-Atom Transfer (DOT) Mechanism

Next, we investigated the structure-reactivity relationship of 1. For sulfoxidation reaction of thioanisole by 1, the oxidation via the DOT mechanism was firstly calculated. As shown in Figure 2, for the reactant complex (RC), the ground state is a high-spin quintet states (S = 2), as the elongation of I-O bond, spin reversion occurs and the reaction path switches from the quintet to the triplet spin state (S = 1) on the transition state. The formed product complex is on the quintet ground state. This reaction is a TSR process (Shaik et al., 1998, 2002; Ogliaro et al., 2000). For 5RC, the average distance of Mn-N is 2.172 Å, the length of Mn-OIPh is 1.951 Å, and the I-O one is 1.922 Å. For the transition states 3, 5TSDOT, 5TSDOT lies 53.6 kcal mol−1 above by 5RC and 3TSDOT lies 26.8 kcal mol−1. The activation energy barrier of the DOT process is very high. For the low-lying 3TSDOT, the Mn-O distance is 2.164 Å, the S-O one is 2.071 Å, the O-I one is 2.014 Å, and the length of between I and OH is 2.760 Å, which means I-O bond and halogen bond I-OH cannot completely broken and has a strong interaction. The elongation of the two bonds needs such high activation energy barrier (26.8 kcal/mol), indicating that it is very difficult to oxide the thioanisole by the DOT mechanism with the way of two-electron transfer for complex 1. In previous work, Oae and his coworkers suggested ETOT mechanism for the sulfoxidation of a series of aromatic sulfides promoted by an iron (III) porphyrin (Oae et al., 1982). Lanzalunga also illustrate the aryl diphenylmethyl sulfides promoted by the non-heme iron(IV)-oxo complex occurs by electron transfer followed by oxygen transfer (ETOT) mechanism (Barbieri et al., 2016). Whether the sulfoxidation of thioanisole mediated by Mn(III)-iodosylarene complex was in the ETOT way?

Figure 2. Energy profiles (in kcal mol−1) for thioanisole sulfoxidation via the direct oxygen-atom transfer mechanism. Energies were calculated at the UB3LYP-D3(BJ)/B2//B1+ZPE/B1 level in solvent. Key geometric information on transition states is presented. Hydrogen atoms are omitted for clarity. Energies are in kcal mol−1 units, lengths are in Å units, angles are in degree units, and imaginary frequencies are in cm−1 units.

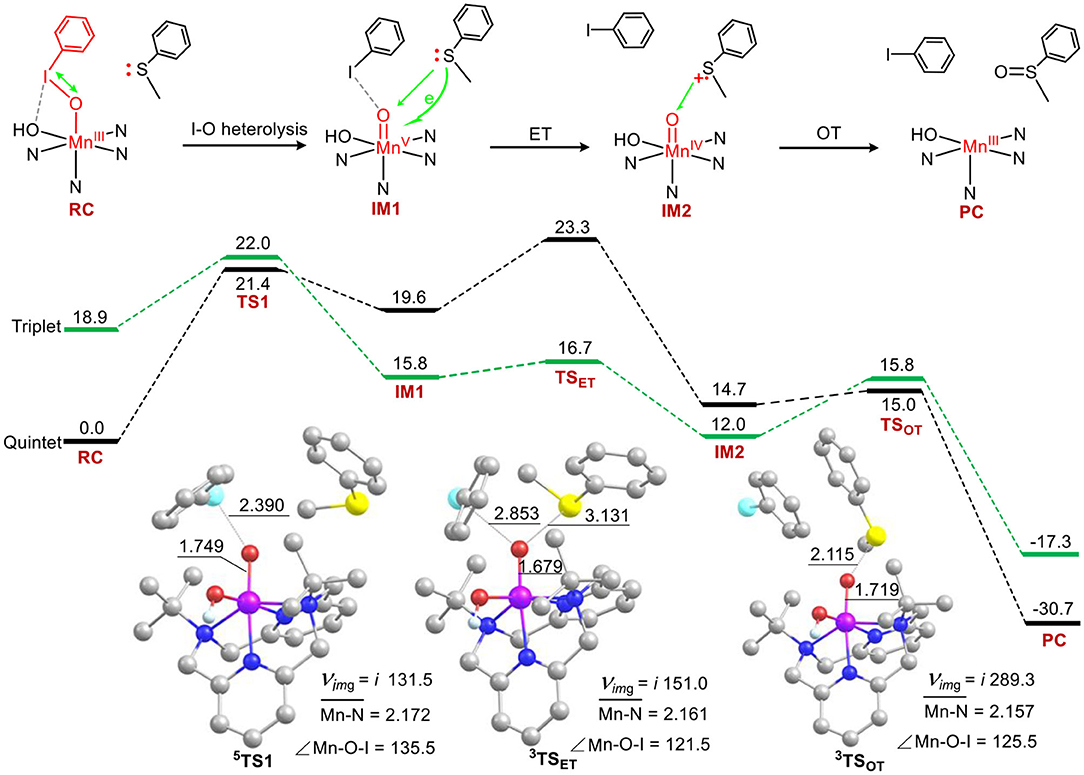

Sulfoxidation of Thioanisole by 1 via the Electron Transfer/Oxygen Transfer (ETOT) Mechanism

The calculated energy profiles for sulfoxidation via the ETOT mechanism have been presented in Figure 3. The activation barrier of the rate-limiting step of I-O bond cleavage is 21.4 kcal mol−1, which is 5.4 kcal mol−1 lower than the barrier of sulfoxidation in the DOT mechanism (Figure 2). For 5TS1, the I-O distance is 2.390 Å, the Mn-O distance is 1.749 Å, the S-O one was kept at 4.384 Å. The angle of Mn-O-I is 135.5°. Both the activation energy and the geometries of transitions states have introduced into the reaction system (comparing to Figure 1 for the case of absence of substrates). As the I-O bond further elongation, spin reversion occurs and the reaction path switches from the quintet state to the triplet one (S = 1) on the transition state 2. Thus, this is an another two-state reactivity (TSR) process (Shaik et al., 1998, 2002; Ogliaro et al., 2000). During the substrate thioanisole approaching, an intermolecular electron transfer occurs from thioanisole to the manganese-oxo moiety to form an Mn(IV)–oxo species with an one-electron oxidized thioanisole cation radical. For the low-lying 3TSET, as depicted in Figure 3, the I-O distance is 2.853 Å, the Mn-O one is 1.679 Å, and the I-OH one is 3.460 Å, the angle of Mn-O-I is 121.5°. The spin of thioanisole is ca. 1.3. This conversion has a tiny barrier of 0.9 kcal mol−1. The following oxygen transfer step is a two-state reactivity process, with degenerate quintet and triplet transition states 3, 5TSOT (5TSOT is 0.8 kcal mol−1 lower than 3TSOT). The ground state of product complex is the quintet state and the products are the quintet MnIII (TBDAP)(OH)− complex and sulfoxide. This step is an exothermic process with large heat (42.7 kcal mol−1). In short, the reaction proceeds in a stepwise way; first involving a substrate-induced O-I bond small but obvious change when the substrate thioanisole is cleavage, following by an intermolecular electron transfer from the substrate to the Mn(V)–oxo core, and ended by an oxygen rebound step to form the sulfoxide product. In such way, the ETOT pathway has lower activation energy and becomes dominant over the DOT pathway.

Figure 3. Energy profiles (in kcal mol−1) for the thioanisole sulfoxidation via the ETOT mechanism. Energies were calculated at the UB3LYP-D3(BJ)/B2//B1+ZPE/B1 level in solvent. The key geometric data of the transition states are presented. Hydrogen atoms are omitted for clarity. Lengths are in Å units, angles are in degree units, and imaginary frequencies are in cm−1 unit.

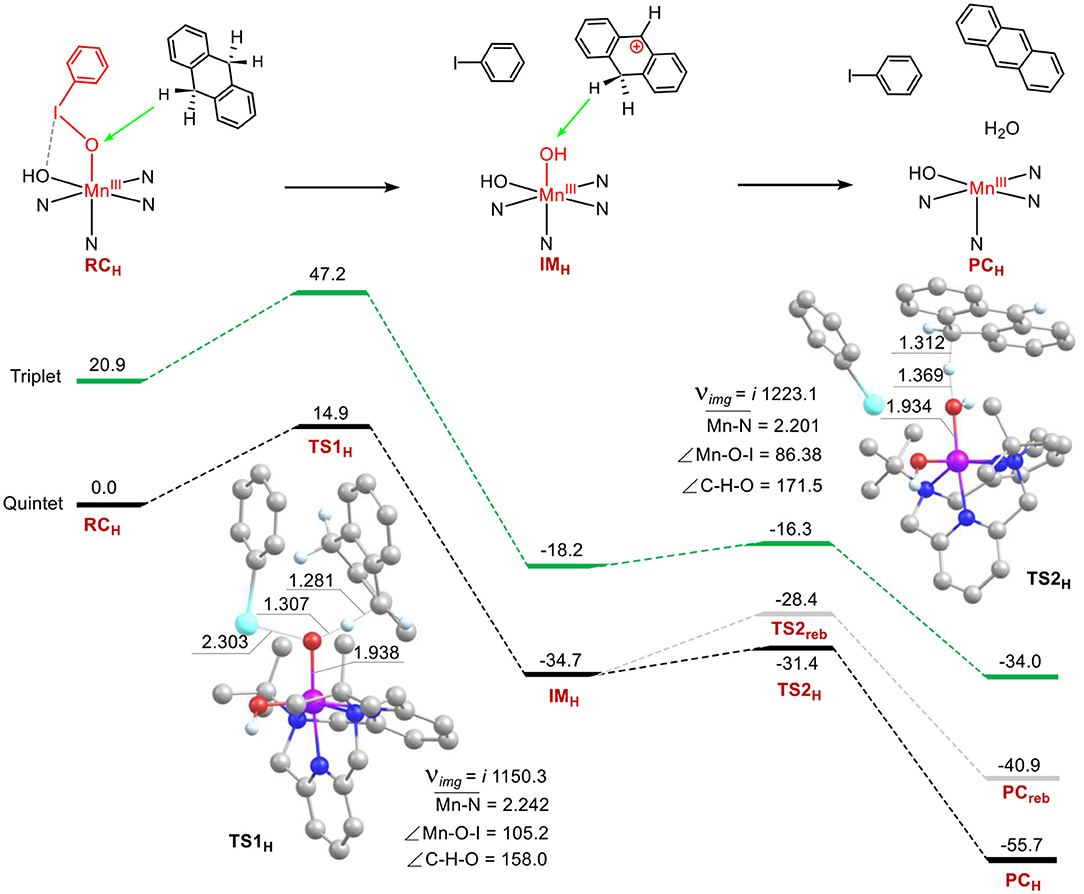

C-H Bond Activation of 9, 10-Dihydroanthracene by 1

The C–H bond activation of hydrocarbons by metal-oxo active oxygen species is one of the most important subjects in bioinorganic and oxidation chemistry (Solomon et al., 2000; Nam, 2007; Shaik et al., 2007; Van Eldik, 2007; Gunay and Theopold, 2010; Mayer, 2010; Cho et al., 2012). The reactivity of 1 in the C–H activation reaction was investigated as well. Energy profiles for the C-H bond activation of 9, 10-dihydroanthracene (DHA) have been present in Figure 4. Surprisingly, the manganese-iodosylarene complex 1 exhibits robust oxidative ability toward DHA. The rate-limiting step of the first C-H abstraction step holds a barrier of 14.9 kcal mol−1, which is much lower than the barriers in sulfoxidation of thioanisole. The result is also in agreement with the rank of second-order rate constant (Jeong et al., 2018). For 5TS1H, the Mn-O distance is 1.938 Å, the I-O one is 2.303 Å, the Mn-O-I angle is 105.2°. For the reaction coordinates, the C-H distance is 1.281 Å, the O-H distance is 1.307 Å and the C-H-O angle is 158.0°. The lengths of the O-H moiety and the C-H one are consistent with normal C-H abstraction protocol, while the C-H-O angle is too bent (normally the angle is nearly 180° for C-H abstraction by high-valent metal-oxo species). Investigation of 5TS1H's geometry, we can see there is a strong stacking interaction between the phenyl ring of PhI and the ring of DHA. Such a reaction is beneficial to lower the activation energy. After the transition state, the H-abstracted DHA moiety (DHA-H) automatically rotates and directs the second C-H moiety of the methylene moiety (-CH2-) to the nascent Mn(III)-(OH)2 complex (IMH). Surprisingly, There is no spin for H and the DHA-H moiety at the intermediate state IMH (Supplementary Table S10), the Mulliken charge of DHA-H changes from a negative value (ca. −0.16) in the reagent complex to a positive one (ca. 0.95) in the IMH. Thus, the DHA-H becomes a carbonium species, which could well explain the rotation of DHA as the repulsive effect between cationic carbonium and H parts. Thus, the first C-H bond activation step is a novel hydride transfer (HT) process. Subsequently, a second C-H abstraction of the methylene group by the Mn(III)-(OH)2 complex occurs. The barrier of the second hydrogen abstraction is only 3.3 kcal mol−1, it's an easy process to occur. For the low-lying 5TS2H, there is no spin populated in the DHA-H moiety yet, and the Mulliken charge of DHA-H is decreased (ca. 0.38), demonstrating that the second step is a proton transfer (PT) process. We also calculated the possible oxygen rebound step and found that the energy of the transition state for the rebound step is 3.0 kcal mol−1 higher than the energy of the second H-abstraction step. The exothermicity of the rebound step is also 14.8 kcal mol−1 less than that of the second hydrogen abstraction step. Thus, C-H activation of DHA by 1 proceeds via a novel ionic hydride transfer/proton transfer (HT/PT) mechanism, not the H-abstraction/O-rebound mechanism, or the dual hydrogen abstraction mechanism in P450 chemistry. Interestingly, for the transition state of the second hydrogen abstraction, the reaction coordinate C-H-O is nearly colinear (the C-H-O angle is 171°). This is for the sake that in 5TS2H, there is no stacking interaction. At the product complex state, a H2O and the manganese(III) catalyst are formed for the second catalytic cycle. In short, our calculations support the mechanistic proposed by the Cho's experiment that 1 is a good electrophilic agent in oxidative C-H bond activation (Jeong et al., 2018).

Figure 4. Energy profiles (in kcal mol−1) for the C-H bond activation of 9,10-dihydroanthracene. Energies were calculated at the UB3LYP-D3(BJ)/B2//B1+ZPE/B1 level in solvent. The key geometric information on the transition state TS1 and TS2 is presented. Unimportant hydrogen atoms are omitted for clarity. Lengths are in Å units, angles are in degree units, and imaginary frequencies are in cm−1 unit.

The Electrophilicity of the Iodosylbenzene Monomer PhIO in Thioanisole Sulfoxidation and in C-H Bond Activation

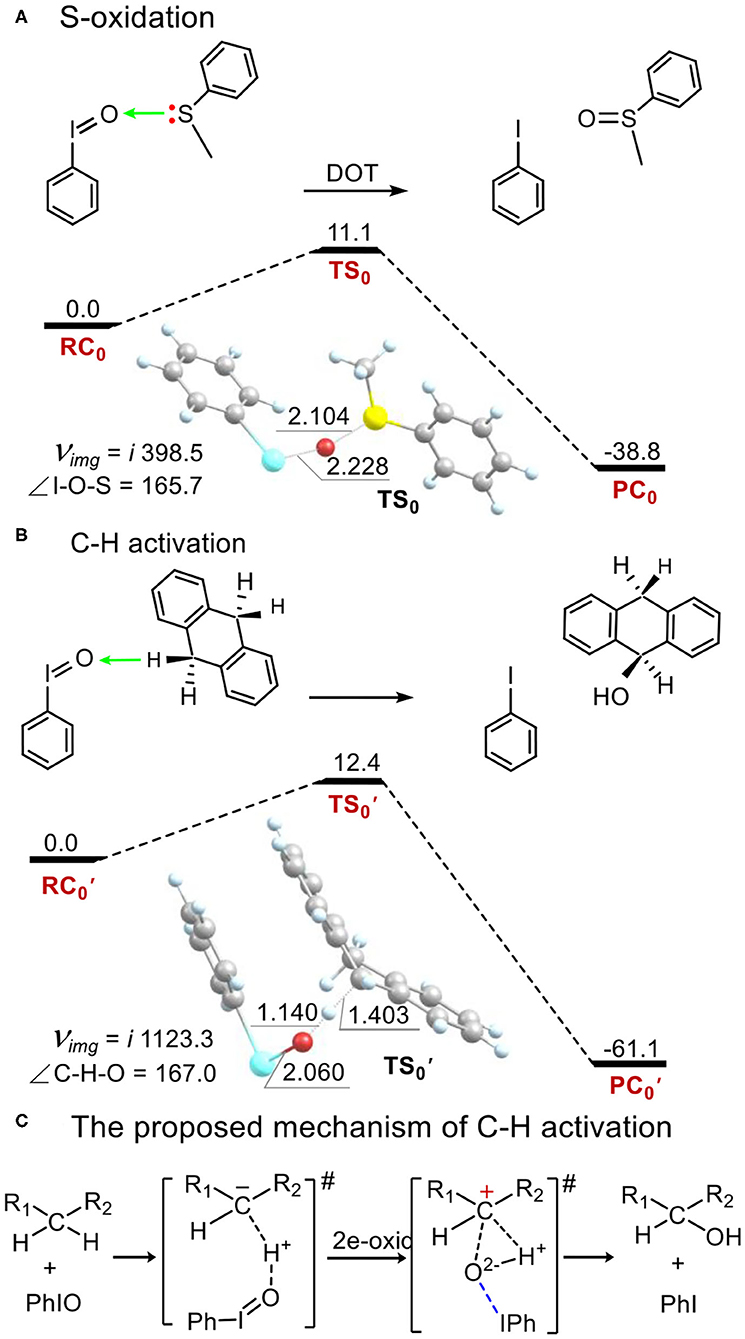

As a comparison to the electrophilicity of metal-iodosybenzene adduct 1, we investigated the electrophilicity of an iodosylbenzene monomer PhIO in thioanisole sulfoxidation and in C-H bond activation of DHA. As shown in Figure 5, PhIO acts as a robust electrophilic agent in these two oxidations (Barbieri et al., 2016). In the activation energy is only 11.1 kcal mol−1 in thioanisole sulfoxidation (Figure 5A) and is only 12.4 kcal mol−1 in hydroxylation of DHA (Figure 5B), which is consistent with the calculated results of hydroxylation of ethylbenzene by PhIO (Kim et al., 2009; Kumar et al., 2009; Kang et al., 2017). In sulfoxidation, the mechanism is a direct oxygen transfer (DOT) mechanism. For the transition state TS0, the I-O distance is 2.228 Å, the S-O one is 2.104 Å and the angle of I-O-S is 165.7°. Mulliken spin of the relaying oxygen is zero. In hydroxylation of DHA, the reaction mechanism is not the stepwise radical-involving hydrogen-abstraction/oxygen-rebound mechanism shown in alkane hydroxylation by high-valent metal-oxo reaction intermediates. The reaction is concerted and for the sole transition state (Figure 5B), the O-H distance is 1.140 Å, the C-H one is 1.403 Å and the C-H-O angle is 167.0°, which is not as colinear as the one in alkane hydroxylation by high-valent metal-oxo. Such non-colinear hydrogen abstraction is also reported by de Visser and Nam (Kim et al., 2009). We can find that there is no spin in any moieties at the transition state . Mulliken charge of H-abstracted DHA (DHA-H) changes from a negative value (ca. −0.3) in the reagent complex and the transition state to a positive one (ca. 0.3) after the transition state alongside the intrinsic reaction coordinate (Supplementary Figures S12, S13). Thus, hydroxylation by PhIO is an ionic and concerted proton-transfer/hydroxyl rebound process (Figure 5C).

Figure 5. Energy profiles (in kcal mol−1) for (A) thioanisole sulfoxidation and (B) C-H bond activation of 9,10-dihydroanthracene by the PhIO monomer. (C) An ionic proton-transfer/hydroxyl-rebound mechanism was proposed for C-H activation by PhIO. Energies were calculated at the UB3LYP-D3(BJ)/B2//B1+ZPE/B1 level in solvent. Geometric data of transition states are presented. Lengths are in Å units, angles are in degree units, and imaginary frequencies are in cm−1 unit.

Conclusions

In the present manuscript, the structure-function relationship of a metal-iodosylarene adduct [MnIII(TBDAP)(OIPh)(OH)]2+ 1 in sulfoxidation and oxidative C-H bond activation were investigated by means of density functional theoretical calculation. The calculated results are consistent with the experimental results and the conclusion by Cho et al. that the metal-iodosylarene adduct 1 is a good electrophilic agent. The theoretical study also revealed some new interesting mechanistic insights into the electrophilicity of 1. 1 behaves as a stepwise 1e+1e oxidant in sulfoxidations, oxygen transfer occurs via the electron transfer followed by oxygen transfer (ETOT). While In oxidation of DHA, a novel and ionic hydride transfer/proton transfer (HT/PT) mechanism, not the normal hydrogen-abstraction/oxygen rebound mechanism or the dual hydrogen abstraction mechanism in P450 chemistry, was found to mediate the reaction. Such new mechanistic properties are caused by the halogen bond between phenyl ring of PhIO and the ligated hydroxyl group, and also by the stacking interaction between the phenyl ring of PhIO and substrates. As a comparison to the electrophilicity of the metal-iodosylarene adduct 1, the structure-function relationship of an iodosylbenzene monomer PhIO is also presented. The calculated results demonstrated that electrophilicity of PhIO is even more robust than that of 1. PhIO behaves as a 2e-oxidant in both thioanisole oxidation and hydroxylation of DHA. A new ionic and concerted proton transfer/hydroxyl rebound mechanism involving 2e-oxidation to form a transient carbonium species was proposed for the hydroxylation of DHA by PhIO.

Data Availability Statement

All datasets presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Material.

Author Contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct and intellectual contribution to the work, and approved it for publication.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (project 21873052), the Natural Science Foundation of Zhejiang Province (project LQ20B030004), and the open fund of the State Key Laboratory of Molecular Reaction Dynamics (project SKLMRD-K202005).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fchem.2020.00744/full#supplementary-material

References

Adamo, C., and Barone, V. (1999). Toward reliable density functional methods without adjustable parameters: the PBE0 model. J. Chem. Phys. 110, 6158–6170. doi: 10.1063/1.478522

Au-Yeung, K.-C., So, Y.-M., Wang, G.-C., Sung, H. H. Y., Williams, I. D., and Leung, W. H. (2016). Iodosylbenzene and iodylbenzene adducts of cerium (iv) complexes bearing chelating oxygen ligands. Dalton. Trans. 45, 5434–5438. doi: 10.1039/C6DT00267F

Baciocchi, E., Gerini, M. F., Lanzalunga, O., Lapi, A., and Piparo, M. G. L. (2003). Mechanism of the oxidation of aromatic sulfides catalysed by a water soluble iron porphyrin. Org. Biomol. Chem. 1, 422–426. doi: 10.1039/b209004j

Barbieri, A., Chimienti, R. D. C., Del Giacco, T., Di Stefano, S., Lanzalunga, O., Lapi, A., et al. (2016). Oxidation of aryl diphenylmethyl sulfides promoted by a nonheme iron(IV)-oxo complex: evidence for an electron transfer-oxygen transfer mechanism. J. Org. Chem. 81, 2513–2520. doi: 10.1021/acs.joc.6b00099

Barone, V., and Cossi, M. (1998). Quantum calculation of molecular energies and energy gradients in solution by a conductor solvent model. J. Phys. Chem. A 102, 1995–2001. doi: 10.1021/jp9716997

Becke, A. D. (1992a). Density-functional thermochemistry. I. The effect of the exchange-only gradient correction. J. Chem. Phys. 96, 2155–2160. doi: 10.1063/1.462066

Becke, A. D. (1992b). Density-functional thermochemistry. II. The effect of the Perdew–Wang generalized-gradient correlation correction. J. Chem. Phys. 97, 9173–9177. doi: 10.1063/1.463343

Becke, A. D. (1993). Density-functional thermochemistry. III. The role of exact exchange. J. Chem. Phys. 98, 5648–5652. doi: 10.1063/1.464913

Cho, J., Sarangi, R., and Wonwoo, N. (2012). Mononuclear metal-O2 complexes bearing macrocyclic N-tetramethylated cyclam ligands. Acc. Chem. Res. 45, 1321–1330. doi: 10.1021/ar3000019

Collman, J. P., Chien, A. S., Eberspacher, T. A., and Brauman, J. I. (2000). Multiple active oxidants in cytochrome P-450 model oxidations. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 122, 11098–11100. doi: 10.1021/ja000961d

Cossi, M., Rega, N., Scalmani, G., and Barone, V. (2003). Energies, structures, and electronic properties of molecules in solution with the C-PCM solvation model. J. Comput. Chem. 24, 669–681. doi: 10.1002/jcc.10189

Feller, D. (1996). The role of databases in support of computational chemistry calculations. J. Comput. Chem. 17, 1571–1586. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-987X(199610)17:13<1571::AID-JCC9>3.0.CO;2-P

Frisch, M. J., Trucks, G. W., Schlegel, H. B., Scuseria, G. E., Robb, M. A., Cheeseman, J. R., et al. (2016). Gaussian 16. Revision B.01. Wallingford, CT: Gaussian, Inc.

Geng, C. Y., Weiske, T., Li, J. L., Shaik, S., and Schwarz, H. (2019). Intrinsic reactivity of diatomic 3d transition-metal carbides in the thermal activation of methane: striking electronic structure effects. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141, 599–610. doi: 10.1021/jacs.8b11739

Geng, C. Y., Weiske, T., Schlangen, M., Shaik, S., and Schwarz, H. (2017). Electrostatic and charge-induced methane activation by a concerted double C-H bond insertion. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 1684–1689. doi: 10.1021/jacs.6b12514

Goto, Y., Matsui, T., Ozaki, S.-I., Watanabe, Y., and Fukuzumi, S. (1999). Mechanisms of sulfoxidation catalyzed by high-valent intermediates of heme enzymes: electron-transfer vs oxygen-transfer mechanism. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 121, 9497–9502. doi: 10.1021/ja9901359

Grimme, S., Antony, J., Ehrlich, S., and Krieg, H. (2010). A consistent and accurate ab initio parametrization of density functional dispersion correction (DFT-D) for the 94 elements H-Pu. J. Chem. Phys. 132:154104. doi: 10.1063/1.3382344

Grimme, S., Ehrlich, S., and Goerigk, L. (2011). Effect of the damping function in dispersion corrected density functional theory. J. Comput. Chem. 32, 1456–1465. doi: 10.1002/jcc.21759

Groves, J. T., and Nemo, T. E. (1983). Epoxidation reactions catalyzed by iron porphyrins. Oxygen transfer from iodosylbenzene. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 105, 5786–5791. doi: 10.1021/ja00356a015

Groves, J. T., Nemo, T. E., and Myers, R. S. (1979). Hydroxylation and epoxidation catalyzed by iron-porphine complexes. Oxygen transfer from iodosylbenzene. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 101, 1032–1033. doi: 10.1021/ja00498a040

Gunay, A., and Theopold, K. H. (2010). C– H bond activations by metal oxo compounds. Chem. Rev. 110, 1060–1081. doi: 10.1021/cr900269x

Guo, M., Dong, H., Li, J., Cheng, B., Huang, Y.-Q., Feng, Y.-Q., et al. (2012). Spectroscopic observation of iodosylarene metalloporphyrin adducts and manganese (V)-oxo porphyrin species in a cytochrome P450 analogue. Nat. Commun. 3:1190. doi: 10.1038/ncomms2196

Hay, P. J., and Wadt, W. R. (1985). Ab initio effective core potentials for molecular calculations. Potentials for K to Au including the outermost core orbitals. J. Chem. Phys. 82, 299–310. doi: 10.1063/1.448975

Hill, E. A., Kelty, M. L., Filatov, A. S., and Anderson, J. S. (2018). Isolable iodosylarene and iodoxyarene adducts of Co and their O-atom transfer and C–H activation reactivity. Chem. Sci. 9, 4493–4499. doi: 10.1039/C8SC01167B

Hong, S., Wang, B., Seo, M. S., Lee, Y. M., Kim, M. J., Kim, H. R., et al. (2014). Highly reactive nonheme iron (III) iodosylarene complexes in alkane hydroxylation and sulfoxidation reactions. Angew. Chem. Int. Edit. 53, 6388–6392. doi: 10.1002/anie.201402537

Isaia, F., Aragoni, M. C., Arca, M., Demartin, F., Devillanova, F. A., Ennas, G., et al. (2009). Molecular iodine stabilization in an extended N··· I-I··· N assembly. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2009, 3667–3672. doi: 10.1002/ejic.200900429

Jaccob, M., Comba, P., Maurer, M., Vadivelu, P., and Venuvanalingam, P. (2011). A combined experimental and computational study on the sulfoxidation by high-valent iron bispidine complexes. Dalton Trans. 40, 11276–11281. doi: 10.1039/c1dt11533b

Jeong, D., Ohta, T., and Cho, J. (2018). Structure and reactivity of a mononuclear nonheme manganese(III)-iodosylarene complex. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 140, 16037–16041. doi: 10.1021/jacs.8b10244

Kang, Y., Li, X. X., Cho, K. B., Sun, W., Xia, C., Nam, W., et al. (2017). Mutable properties of nonheme iron(III)-iodosylarene complexes result in the elusive multiple-oxidant mechanism. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 7444–7447. doi: 10.1021/jacs.7b03310

Kaupp, M., Reviakine, R., Malkina, O. L., Arbuznikov, A., Schimmelpfennig, B., and Malkin, V. G. (2002). Calculation of electronic g-tensors for transition metal complexes using hybrid density functionals and atomic meanfield spin-orbit operators. J. Comput.Chem. 23, 794–803. doi: 10.1002/jcc.10049

Kim, S. J., Latifi, R., Kang, H. Y., Nam, W., and De Visser, S. P. (2009). Activation of hydrocarbon C-H bonds by iodosylbenzene: how does it compare with iron(IV)-oxo oxidants? Chem. Comm. 13, 1562–1564. doi: 10.1039/b820812c

Kumar, D., Tahsini, L., De Visser, S. P., Kang, H. Y., Kim, S. J., and Nam, W. (2009). Effect of porphyrin ligands on the regioselective dehydrogenation versus epoxidation of olefins by oxoiron (IV) mimics of cytochrome P450. J. Phys. Chem. A 113, 11713–11722. doi: 10.1021/jp9028694

Lennartson, A., and Mckenzie, C. J. (2012). An iron(III) iodosylbenzene complex: a masked non-heme FeVO. Angew. Chem. Int. Edit. 51, 6767–6770. doi: 10.1002/anie.201202487

Li, C., Zhang, L., Zhang, C., Hirao, H., Wu, W., and Shaik, S. (2007). Which oxidant is really responsible for sulfur oxidation by cytochrome P450? Angew. Chem. Int. Edit. 46, 8168–8170. doi: 10.1002/anie.200702867

Li, J. L., Zhou, S., Schlangen, M., Weiske, T., and Schwarz, H. (2016). Hidden hydride transfer as a decisive mechanistic step in the reactions of the unligated gold carbide [AuC]+ with methane under ambient conditions. Angew. Chem. Int. Edit. 55, 3072–13075. doi: 10.1002/anie.201606707

Liu, F., Du, L., Zhang, D., and Gao, J. (2016). Performance of density functional theory on the anisotropic halogen··· halogen interactions and potential energy surface: problems and possible solutions. Int. J. Quantum Chem. 116, 710–717. doi: 10.1002/qua.25093

Macikenas, D., Skrzypczak-Jankun, E., and Protasiewicz, J. D. (2000). Redirecting secondary bonds to control molecular and crystal properties of an iodosyl-and an iodylbenzene. Angew. Chem. Int. Edit. 39, 2007–2010. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20000602)39:11<2007::AID-ANIE2007>3.0.CO;2-Z

Mayer, J. M. (2010). Understanding hydrogen atom transfer: from bond strengths to Marcus theory. Acc. Chem. Res. 44, 36–46. doi: 10.1021/ar100093z

Nam, W. (2007). High-valent iron (IV)–oxo complexes of heme and non-heme ligands in oxygenation reactions. Acc. Chem. Res. 40, 522–531. doi: 10.1021/ar700027f

Nam, W., Jin, S. W., Lim, M. H., Ryu, J. Y., and Kim, C. (2002). Anionic ligand effect on the nature of epoxidizing intermediates in iron porphyrin complex-catalyzed epoxidation reactions. Inorg. Chem. 41, 3647–3652. doi: 10.1021/ic011145p

Nam, W., and Valentine, J. S. (1990). Zinc (II) complexes and aluminum (III) porphyrin complexes catalyze the epoxidation of olefins by iodosylbenzene. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 112, 4977–4979. doi: 10.1021/ja00168a063

Oae, S., Watanabe, Y., and Fujimori, K. (1982). Biomimetic oxidation of organic sulfides with TPPFe(III)Cl/imidazole/hydrogen peroxide. Tetrahedron Lett. 23, 1189–1192. doi: 10.1016/S0040-4039(00)87056-2

Ogliaro, F., Harris, N., Cohen, S., Filatov, M., De Visser, S. P., and Shaik, S. (2000). A model “rebound” mechanism of hydroxylation by cytochrome P450: stepwise and effectively concerted pathways, and their reactivity patterns. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 122, 8977–8989. doi: 10.1021/ja991878x

Perdew, J. P. (1986). Density-functional approximation for the correlation energy of the inhomogeneous electron gas. Phys. Rev. B 33:8822. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.33.8822

Schuchardt, K. L., Didier, B. T., Elsethagen, T., Sun, L., Gurumoorthi, V., Chase, J., et al. (2007). Basis set exchange: a community database for computational sciences. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 47, 1045–1052. doi: 10.1021/ci600510j

Schwarz, H., Shaik, S., and Li, J. L. (2017). Electronic effects On room-temperature, gas-Phase C-H bond activations by cluster oxides and metal carbides: the methane challenge. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 17201–17212. doi: 10.1021/jacs.7b10139

Shaik, S., De Visser, S. P., Ogliaro, F., Schwarz, H., and Schröder, D. (2002). Two-state reactivity mechanisms of hydroxylation and epoxidation by cytochrome P-450 revealed by theory. Curr. Opin. Chem. Bio. 6, 556–567. doi: 10.1016/S1367-5931(02)00363-0

Shaik, S., Filatov, M., Schröder, D., and Schwarz, H. (1998). Electronic structure makes a difference: cytochrome P-450 mediated hydroxylations of hydrocarbons as a two-state reactivity paradigm. Chem. Eur. J. 4, 193–199. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-3765(19980210)4:2<193::AID-CHEM193>3.0.CO;2-Q

Shaik, S., Hirao, H., and Kumar, D. (2007). Reactivity of high-valent iron–oxo species in enzymes and synthetic reagents: a tale of many states. Acc. Chem. Res. 40, 532–542. doi: 10.1021/ar600042c

Shaik, S., Kumar, D., De Visser, S. P., Altun, A., and Thiel, W. (2005). Theoretical perspective on the structure and mechanism of cytochrome P450 enzymes. Chem. Rev. 105, 2279–2328. doi: 10.1021/cr030722j

Shaik, S., Wang, Y., Chen, H., Song, J., and Meir, R. (2010). Valence bond modelling and density functional theory calculations of reactivity and mechanism of cytochrome P450 enzymes: thioether sulfoxidation. Faraday Discuss. 145, 49–70. doi: 10.1039/B906094D

Smegal, J. A., and Hill, C. L. (1983). Hydrocarbon functionalization by the (iodosylbenzene) manganese (IV) porphyrin complexes from the (tetraphenylporphinato) manganese (III)-iodosylbenzene catalytic hydrocarbon oxidation system. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 105, 3515–3521. doi: 10.1021/ja00349a025

Solomon, E. I., Brunold, T. C., Davis, M. I., Kemsley, J. N., Lee, S. K., Lehnert, N., et al. (2000). Geometric and electronic structure/function correlations in non-heme iron enzymes. Chem. Rev. 100, 235–349. doi: 10.1021/cr9900275

Turlington, C. R., Morris, J., White, P. S., Brennessel, W. W., Jones, W. D., Brookhart, M., et al. (2014). Exploring oxidation of half-sandwich rhodium complexes: oxygen atom insertion into the rhodium–carbon bond of κ2-coordinated 2-phenylpyridine. Organometallics 33, 4442–4448. doi: 10.1021/om500660n

Van Eldik, R. (2007). Fascinating inorganic/bioinorganic reaction mechanisms. Coordin. Chem. Rev. 251, 1649–1662. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2007.02.004

Wang, B., Lee, Y. M., Seo, M. S., and Nam, W. (2015). Mononuclear nonheme iron (III)-iodosylarene and high-valent iron-oxo complexes in olefin epoxidation reactions. Angew. Chem. Int. Edit. 54, 11740–11744. doi: 10.1002/anie.201505796

Wang, C., Kurahashi, T., and Fujii, H. (2012). Structure and reactivity of an iodosylarene adduct of a manganese (IV)–salen complex. Angew. Chem. Int. Edit. 51, 7809–7811. doi: 10.1002/anie.201202835

Wang, C., Kurahashi, T., Inomata, K., Hada, M., and Fujii, H. (2013). Oxygen-atom transfer from iodosylarene adducts of a manganese (IV) salen complex: effect of arenes and anions on I (III) of the coordinated iodosylarene. Inorg. Chem. 52, 9557–9566. doi: 10.1021/ic401270j

Yang, L., Wang, F., Gao, J., and Wang, Y. (2019). What factors tune the chemical equilibrium between metal-iodosylarene oxidants and high-valent metal-oxo ones? Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 21, 1271–1276. doi: 10.1039/C8CP06117C

Yang, T., Quesne, M. G., Neu, H. M., Reinhard, F. G. C., Goldberg, D. P., and De Visser, S. P. (2016). Singlet versus triplet reactivity in an Mn(V)-oxo species: testing theoretical predictions against experimental evidence. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 138, 12375–12386. doi: 10.1021/jacs.6b05027

Yang, Y., Diederich, F., and Valentine, J. S. (1990). Reaction of cyclohexene with iodosylbenzene catalyzed by non-porphyrin complexes of iron (III) and aluminum (III). Newly discovered products and a new mechanistic proposal. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 112, 7826–7828. doi: 10.1021/ja00177a071

Yoshimura, A., and Zhdankin, V. V. (2016). Advances in synthetic applications of hypervalent iodine compounds. Chem. Rev. 116, 3328–3435. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.5b00547

Zhao, Y., and Truhlar, D. G. (2008). The M06 suite of density functionals for main group thermochemistry, thermochemical kinetics, noncovalent interactions, excited states, and transition elements: two new functionals and systematic testing of four M06-class functionals and 12 other functionals. Theor. Chem. Acc. 120, 215–241. doi: 10.1007/s00214-007-0310-x

Zhdankin, V. V., and Stang, P. J. (2002). Recent developments in the chemistry of polyvalent iodine compounds. Chem. Rev. 102, 2523–2584. doi: 10.1021/cr010003+

Keywords: manganese(III)–iodosylarene, sulfoxidation, C-H bond activation, mechanism, DFT

Citation: Sun D, Chen X, Gao L, Zhao Y and Wang Y (2020) Theoretical Study on the Structural-Function Relationship of Manganese(III)-Iodosylarene Adducts. Front. Chem. 8:744. doi: 10.3389/fchem.2020.00744

Received: 24 June 2020; Accepted: 17 July 2020;

Published: 20 August 2020.

Edited by:

Jilai Li, Jilin University, ChinaReviewed by:

Binju Wang, Xiamen University, ChinaGeng Dong, College of Medicine, Shantou University, China

Copyright © 2020 Sun, Chen, Gao, Zhao and Wang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Dongru Sun, c3VuZG9uZ3J1JiN4MDAwNDA7bmJ1LmVkdS5jbg==; Yong Wang, eW9uZyYjeDAwMDQwO25idS5lZHUuY24=

Dongru Sun*

Dongru Sun* Yufen Zhao

Yufen Zhao Yong Wang

Yong Wang