- 1School of Basic Medical Sciences, Henan University Joint National Laboratory for Antibody Drug Engineering, Kaifeng, China

- 2Department of Chemistry and Center of Diagnostics & Therapeutics, Georgia State University, Atlanta, GA, United States

- 3Central Laboratory, Linyi People's Hospital, Shandong University, Linyi, China

- 4State Key Laboratory of Medicinal Chemical Biology, College of Pharmacy and Tianjin Key Laboratory of Molecular Drug Research, Nankai University, Tianjin, China

- 5Department of Chemistry, University of California, Davis, Davis, CA, United States

O-GlcNAcase (OGA) is the only enzyme responsible for removing N-acetyl glucosamine (GlcNAc) attached to serine and threonine residues on proteins. This enzyme plays a key role in O-GlcNAc metabolism. However, the structural features of the sugar moiety recognized by human OGA (hOGA) remain unclear. In this study, a set of glycopeptides with modifications on the GlcNAc residue, were prepared in a recombinant full-length human OGT-catalyzed reaction, using chemoenzymatically synthesized UDP-GlcNAc derivatives. The resulting glycopeptides were used to evaluate the substrate specificity of hOGA toward the sugar moiety. This study will provide insights into the exploration of probes for O-GlcNAc modification, as well as a better understanding of the roles of O-GlcNAc in cellular physiology.

Introduction

Protein glycosylation is an important protein post-translational modification in various organisms and is critical for a wide range of biological processes. Defective or aberrant glycosylation can lead to serious cellular dysfunction or diseases in humans (Wells et al., 2001). O-GlcNAcylation is a single N-acetylglucosamine beta-linked to the serine or threonine residues of some nucleic acids and cytoplasmic proteins, and is essential for multiple cellular signaling cascades, including gene transcription, protein translation, cell cycle, and nutrient sensing (Chen et al., 2013; Ferrer et al., 2014; Hardiville and Hart, 2014). By affecting the stability, activity, or interactions of key signaling proteins, O-GlcNAcylation is a novel and vital factor in the cause of diseases such as diabetes, cancer, and neurodegeneration (Yuzwa et al., 2012; Yuzwa and Vocadlo, 2014; Zhu et al., 2014). Because of the importance of O-GlcNAc and its crucial role in disease pathology, the enzymes controlling O-GlcNAcylation levels are considered to be therapeutic targets.

O-GlcNAcylation is a dynamic reversible process, the addition and removal of GlcNAc residues from a protein is regulated by only two enzymes. Uridine diphosphate-N-acetyl-D-glucosamine: polypeptidyl transferase (OGT) is responsible for transferring a single GlcNAc from uridine diphosphate-α-N-acetyl-D-glucosamine (UDP-GlcNAc) to proteins. O-GlcNAcase (OGA) removes GlcNAc from glycoproteins. Substrate promiscuity of OGT and OGA has been shown to be valuable for enzymatic catalysis and O-GlcNAcylation level control. The substrate specificity of human OGT (hOGT) has been widely investigated and the hOGT crystal structure has been solved (Lazarus et al., 2011). Among the 26 UDP-sugar derivatives, 4 (UDP-GlcNPr, UDP-6-deoxy-GlcNAc, UDP-4-deoxy-GlcNAc and UDP-6-deoxy-GalNAc) were reported to highly glycosylate peptides via sOGT-catalyzed glycosylation (Ma et al., 2013). For peptide acceptor recognition, 3 positions (−2, −1, and +2) in the peptide sequence are vital for O-GlcNAcylation, and uncharged amino acids are preferred and show high reactivity (Liu et al., 2014). Recently, several research groups solved the structure of hOGA and revealed that hOGA existed as an unusual arm-in-arm homodimer. The residues of hOGA on the cleft surface enabled broad interactions with peptide substrates, indicating the important role of the peptide structure in the recognition mode (Elsen et al., 2017; Li et al., 2017; Roth et al., 2017). However, partly because of the difficulties in obtaining glycopeptides with modified GlcNAc residues, structure determination during GlcNAc-recognition by hOGA remains unclear.

We previously evaluated chemoenzymatic synthesis and purified oligosaccharides and glycopeptides (Wen et al., 2016a,b; Wu et al., 2016; Wang et al., 2018). As an extension of these studies, glycopeptides containing different GlcNAc derivatives were successfully synthesized and purified. Further, we investigated the substrate specificity of hOGA and found that hOGA was less promiscuous in tolerating substrates with modified GlcNAc.

Results

Synthesis of GlcNAc Derivatives

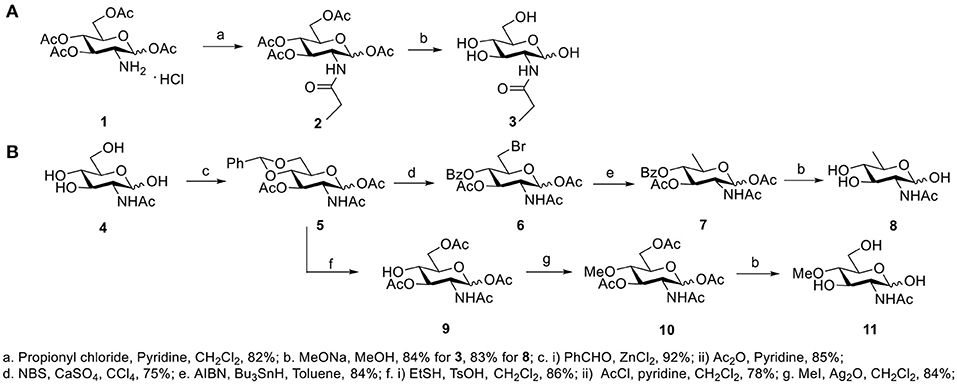

GlcNAc and GalNAc were purchased from Carbosynth (San Diego, CA, USA). GlcNPh, GlcNGc, GlcNTFA, and 6-N3-GlcNAc were gifted from Dr. Xi Chen's lab (UC Davis, USA). 4-Deoxy-GlcNAc and GlcNAz were synthesized according to our previous report (Li et al., 2016). The other three new compounds, GlcNPr, 4-OMe-GlcNAc, and 6-deoxy-GlcNAc, were synthesized for the first time in this study (Figure 1). GlcNPr was generated in the presence of propionyl chloride and pyridine after global deprotection. A convergent route was designed to synthesize 6-deo-GlcNAc and 4-OMe-GlcNAc; GlcNAc as the starting material was first protected with benzylidine and then subjected to 1,3-diacetylation to afford intermediate 5. Selective deprotection of benzylidine was carried out in the presence of NBS and calcium sulfate to afford 6. The desired target compound 8 was obtained after reduction of the bromide and full deacetylation. For 4-OMe-GlcNAc, bezylidine in 5 was removed and selective acetylation of the 6-OH freed the 4-OH, which was O-methylated in the presence of iodomethane and silver oxide. 11 was obtained after global deprotection.

Protein Expression and Purification

According to previous studies, we overexpressed Bifidobacterium infantis N-acetylhexosamine 1-kinase ATCC#15697 (BiNahK), human UDP-N-acetylgalactosamine pyrophosphorylase (hAGX1), human OGT (ncOGT), and human OGA (hOGA) in Escherichia coli (Gross et al., 2005; Guan et al., 2010; Li et al., 2011, 2012). Enzymes were expressed by induction with 1 mM of isopropyl 1-thio-β-D-galactopyranoside followed by incubation at 16°C for 24 h with vigorous shaking (200 rpm). After purification, 15 mg ncOGT, 20 mg hOGA, 40 mg BiNahK, and 20 mg hAGX1 were obtained from 1 L of an E. coli culture. As shown in Figure S1, enzymes with an N-terminal His6 tag showed 80% purity with a high yield. The apparent molecular weights of the enzymes according to SDS-PAGE were well-correlated with the calculated molecular weights of each protein.

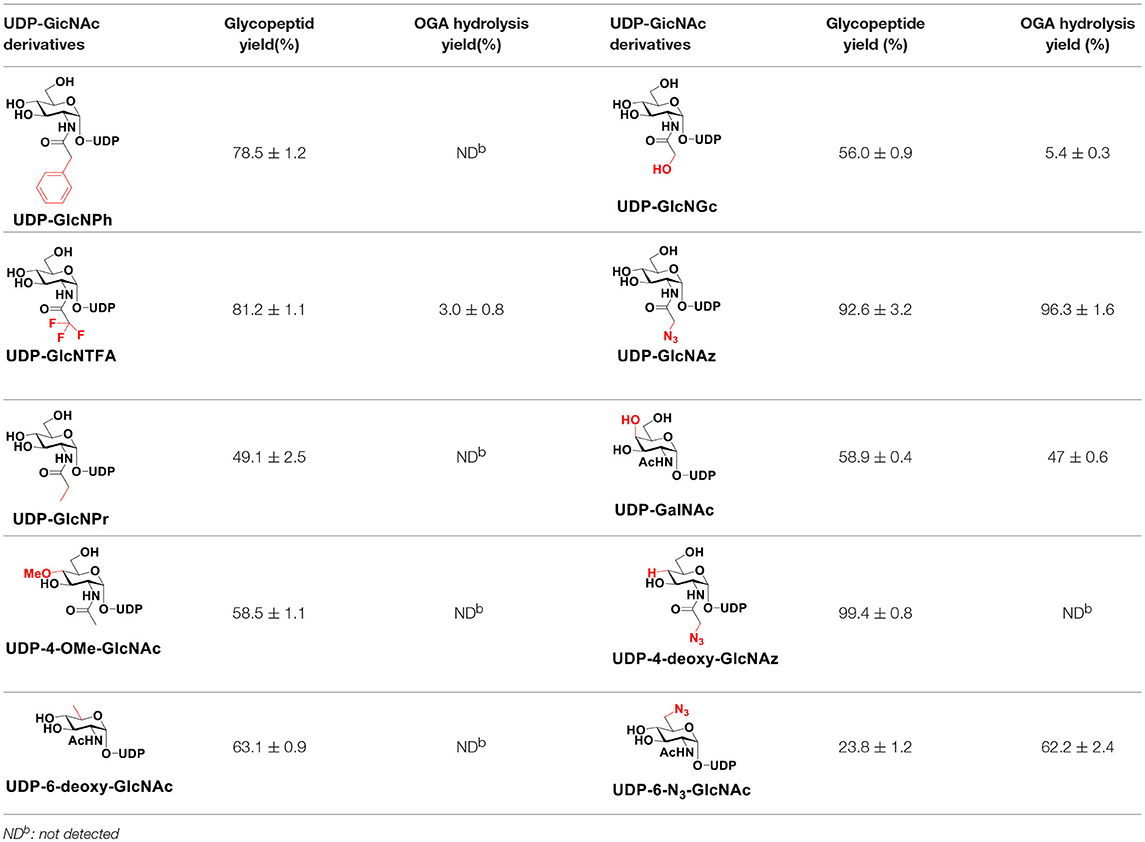

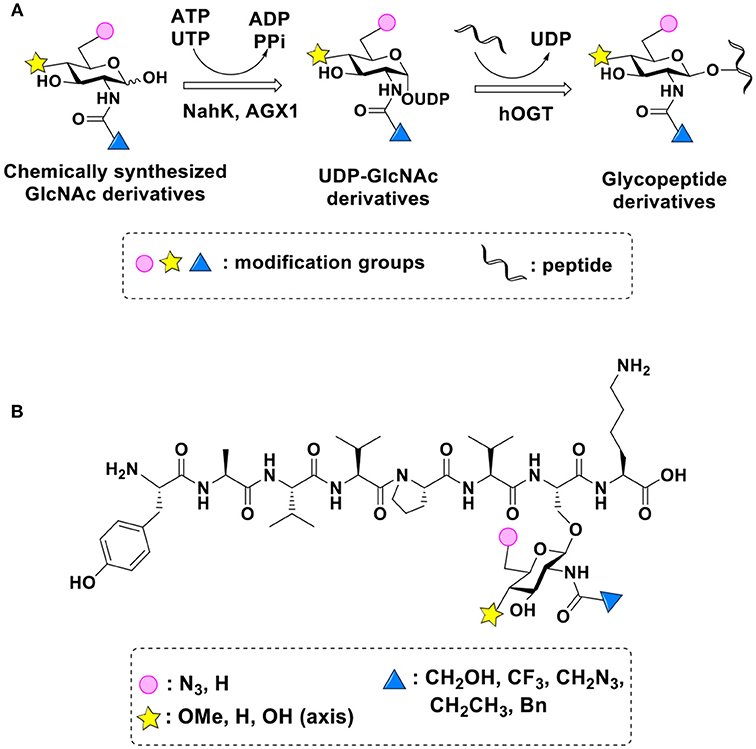

Production of Glycopeptides and Determination of Substrate Specificity of OGT

UDP-GlcNPh, UDP-GlcNGc, UDP-GlcNTFA, and UDP-6-N3-GlcNAc were synthesized as reported previously (Chen et al., 2011). Other sugar nucleotides were obtained through a chemoenzymatic strategy by chemical synthesis of GlcNAc derivatives, which were used as the substrates in a one-pot two-enzyme system containing BiNahK and hAGX1 (Figure 2A). All UDP-sugars produced were characterized by capillary electrophoresis and matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization (MALDI)-time-of-flight mass spectrometry (Figure S3).

Figure 2. (A) Production of glycopeptides by hOGT-catalyzed reaction using chemoenzymatically synthesized UDP-GlcNAc derivatives. (B) The structures of glycopeptide derivatives used in the study.

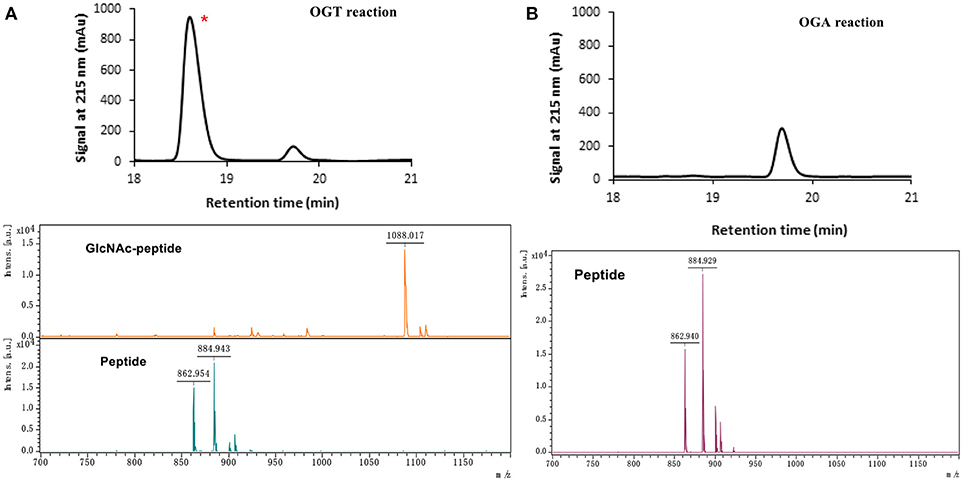

The peptide substrate (YAVVPVSK) was synthesized based on the Fmoc-strategy using a Liberty Blue Peptide Synthesizer and purified by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) (Liu et al., 2014) (Figure S4). A set of glycopeptides carrying modifications on the GlcNAc residue were subsequently prepared in a recombinant full-length hOGT-catalyzed reaction using chemoenzymatically synthesized UDP-GlcNAc derivatives (Figure 2A). The hOGT enzyme reactions were carried out at 37°C for 2 h in a volume of 100 μL containing 1 mM peptide, 3 mM UDP-GlcNAc analogs, and 50 μg ncOGT in buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 10 mM Mg2+). The reaction was boiled, and the products were subjected to HPLC purification and yield quantification (Table 1). Each peak was collected and identified based on MALDI. For example, GlcNAc showed a peak at 18.6 min and was characterized as GlcNAc-peptide with m/z = 1088.017, while the peak at 19.7 min was characterized as a peptide with m/z = 862.954 (M+H) and 884.943 (M+Na) (Figure 3A). The retention time of the pure peptide was 19.7 min, while the GlcNAc-peptide showed a retention time of 18.6 min because of the increased polarity of GlcNAc (Figure 3A). Moreover, the OGT reaction efficiency was calculated as the glycopeptide yield (Ya%). The yield was calculated with the formula Ya = S1/(S1+S2), where S1 and S2 are the integrated areas of the glycopeptide and peptide peaks, respectively (Table 1). The HPLC profile of the OGT and OGA reaction on the peptide are detailed in the Supporting Materials (Figure S2).

Figure 3. The HPLC and MALDI-TOF profile for OGT (A) and OGA (B) reactions toward UDP-GlcNAc substrates. * represents the glycopeptide peak.

By utilizing this method, 10 glycopeptide derivatives (5 glycopeptides with C2-modified GlcNAc, 3 glycopeptides with C4-modified GlcNAc, and 2 glycopeptides with C6-modified GlcNAc) were produced (Figure 2B), purified by HPLC, and characterized by MALDI (Figure S5). All UDP-GlcNAc derivatives were good substrates for hOGT except for UDP-6-N3-GlcNAc, which resulted in only 23.8% yield in vitro (Table 1). Notably, hOGT was the full-length isoform with 13.5 tetratricopeptide repeats (TPRs), which showed higher activity than sOGT (short OGT with 2.5 TPRs). For example, when sOGT was used, six UDP-GlcNAc derivatives (UDP-GlcNGc, UDP-GlcNAz, UDP-GlcNTFA, UDP-GlcNPh, UDP-6-N3-GlcNAc, and UDP-GalNAc) used as the substrates produced <1% yield (Ma et al., 2013). In comparison, over 49% yield was obtained when full-length hOGT was used. The crystal structures of the N-terminal domain of full-length hOGT containing the first 11.5 TPRs, showed that the conserved asparagine residues in the TPR domain directly contacted the substrates, supporting the role of the TRP domains in initial recognition and substrate specificity determination (Jinek et al., 2004). In summary, in addition to preparing glycopeptides, we found that full-length hOGT is a more efficient catalyst than the previously reported short sOGT.

OGA Substrate Specificity Assay

The glycopeptide peaks from OGT reactions were collected and lyophilized for the hOGA substrate specificity assay. The hOGA reaction was conducted overnight in a volume of 100 μL containing the glycopeptides, MgCl2 (20 mM), Tris–HCl (200 mM), and recombinant hOGA (0.1 mg). The reaction mixture was boiled and centrifuged before HPLC separation. Each peak was collected and characterized by MALDI. When the GlcNAc-peptide was treated with hOGA, efficient hydrolysis activity of hOGA and a single peptide peak were observed (Figure 3B). The hOGA hydrolysis yield (Yb%) was calculated using the formula Yb = S2/(S1+S2), where S1 and S2 are the integrated areas of the glycopeptide and peptide peaks, respectively. The HPLC profiles of the OGT and OGA reaction on the peptide are described in detail in the Supporting Materials (Figure S2). The GlcNAz-peptide and 6-N3-GlcNAc-peptide were well-tolerated by hOGA, and other glycopeptide derivatives significantly decreased the efficiency of hOGA, showing <10% hydrolysis yield (Table 1). The results revealed that hOGA had a relatively strict recognition for the sugar moiety in the glycopeptides, thus exhibiting limited activities for glycopeptide derivatives with C2, C4, and C6 modifications on GlcNAc.

Conclusion

Glycopeptides containing different GlcNAc derivatives were successfully synthesized in a recombinant full-length hOGT-catalyzed reaction, using chemoenzymatically synthesized UDP-GlcNAc derivatives. We also found that full-length hOGT is a more efficient catalyst than sOGT, as over a 49-fold yield was observed when hOGT was used. The resulting glycopeptides were used to investigate the substrate specificity of hOGA toward the sugar moiety. hOGA was less promiscuous in tolerating glycopeptide substrates with modified GlcNAc, and changes in the C2, C4, and C6 positions of GlcNAc partially affected its recognition. Interestingly, OGT and OGA possessed different levels of tolerance to the same sugar moiety, such as GlcNPh, GlcNTFA, and 4-OMe-GlcNAc. Therefore, the acquired GlcNAc derivatives, which were well-recognized by OGT but not hydrolyzed by OGA, may increase the O-GlcNAcylation level in vivo when the peracetylated compound is metabolically incorporated. Indeed, our group developed an OGA-resistant probe, peracetylated 4-deoxy-N-azidoacetylglucosamine (Ac3-4-deoxy-GlcNAz), which can be used as a potent tool for O-GlcNAcylation detection and the identification of O-GlcNAcylated proteins (Li et al., 2016). Thus, OGA-resistant GlcNAc substrates show potential as excellent probes for investigating O-GlcNAcylation and elucidating their importance in cellular events.

Author Contributions

SL and JW conducted the experiments and wrote the manuscript. LZ, JG, HZ, JZ, YC, YL, and XC conducted the experiments and the sample analysis. XC and LW contributed to the manuscript revision. PW and JL designed and managed the study.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We thank S. Walker from Harvard Medical School for providing the plasmid pET24b-ncOGT. We acknowledge J. Jiang for her suggestions to this project and financial support from the Molecular Basis of Disease program in Georgia State University as well as grants from the Natural Science Foundation of China (NO. 31000371), Natural Science Foundation of Tianjin (15JCYBJC29000), and Key scientific research projects of universities in Henan (19B15003).

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fchem.2018.00646/full#supplementary-material

References

Chen, Q., Chen, Y., Bian, C., Fujiki, R., and Yu, X. (2013). TET2 promotes histone O-GlcNAcylation during gene transcription. Nature 493, 561–564. doi: 10.1038/nature11742

Chen, Y., Thon, V., Li, Y., Yu, H., Ding, L., Lau, K., et al. (2011). One-pot three-enzyme synthesis of UDP-GlcNAc derivatives. Chem. Commun. 47, 10815–10817. doi: 10.1039/c1cc14034e

Elsen, N. L., Patel, S. B., Ford, R. E., Hall, D. L., Hess, F., Kandula, H., et al. (2017). Insights into activity and inhibition from the crystal structure of human O-GlcNAcase. Nat. Chem. Biol. 13, 613–615. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.2357

Ferrer, C. M., Lynch, T. P., Sodi, V. L., Falcone, J. N., Schwab, L. P., Peacock, D. L., et al. (2014). O-GlcNAcylation regulates cancer metabolism and survival stress signaling via regulation of the HIF-1 pathway. Mol. Cell. 54, 820–831. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2014.04.026

Gross, B. J., Kraybill, B. C., and Walker, S. (2005). Discovery of O-GlcNAc transferase inhibitors. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 127, 14588–14589. doi: 10.1021/ja0555217

Guan, W., Cai, L., and Wang, P. G. (2010). Highly efficient synthesis of UDP-GalNAc/GlcNAc analogues with promiscuous recombinant human UDP-GalNAc pyrophosphorylase AGX1. Chemistry 16, 13343–13345. doi: 10.1002/chem.201002315

Hardiville, S., and Hart, G. W. (2014). Nutrient regulation of signaling, transcription, and cell physiology by O-GlcNAcylation. Cell Metab. 20, 208–213. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2014.07.014

Jinek, M., Rehwinkel, J., Lazarus, B. D., Izaurralde, E., Hanover, J. A., and Conti, E. (2004). The superhelical TPR-repeat domain of O-linked GlcNAc transferase exhibits structural similarities to importin alpha. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 11, 1001–1007. doi: 10.1038/nsmb833

Lazarus, M. B., Nam, Y., Jiang, J., Sliz, P., and Walker, S. (2011). Structure of human O-GlcNAc transferase and its complex with a peptide substrate. Nature 469, 564–567. doi: 10.1038/nature09638

Li, B., Li, H., Lu, L., and Jiang, J. (2017). Structures of human O-GlcNAcase and its complexes reveal a new substrate recognition mode. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 24, 362–369. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.3390.

Li, J., Li, Z., Li, T., Lin, L., Zhang, Y., Guo, L., et al. (2012). Identification of a specific inhibitor of nOGA - a caspase-3 cleaved O-GlcNAcase variant during apoptosis. Biochemistry 77, 194–200. doi: 10.1134/S0006297912020113

Li, J., Wang, J., Wen, L., Zhu, H., Li, S., Huang, K., et al. (2016). An OGA-resistant probe allows specific visualization and accurate identification of O-GlcNAc-modified proteins in cells. ACS Chem. Biol. 11, 3002–3006. doi: 10.1021/acschembio.6b00678

Li, Y., Yu, H., Chen, Y., Lau, K., Cai, L., Cao, H., et al. (2011). Substrate promiscuity of N-acetylhexosamine 1-kinases. Molecules 16, 6396–6407. doi: 10.3390/molecules16086396

Liu, X., Li, L., Wang, Y., Yan, H., Ma, X., Wang, P. G., et al. (2014). A peptide panel investigation reveals the acceptor specificity of O-GlcNAc transferase. FASEB J. 28, 3362–3372. doi: 10.1096/fj.13-246850

Ma, X., Liu, P., Yan, H., Sun, H., Liu, X., Zhou, F., et al. (2013). Substrate specificity provides insights into the sugar donor recognition mechanism of O-GlcNAc transferase (OGT). PLoS ONE 8:e63452. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0063452

Roth, C., Chan, S., Offen, W. A., Hemsworth, G. R., Willems, L. I., King, D. T., et al. (2017). Structural and functional insight into human O-GlcNAcase. Nat. Chem. Biol. 13, 610–612. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.2358

Wang, J., Greenway, H., Li, S., Wei, M., Polizzi, S. J., and Wang, P. G. (2018). Facile and stereo-selective synthesis of UDP-alpha-D-xylose and UDP-beta-L-arabinose using UDP-Sugar pyrophosphorylase. Front. Chem. 6:163. doi: 10.3389/fchem.2018.00163

Wells, L., Vosseller, K., and Hart, G. W. (2001). Glycosylation of nucleocytoplasmic proteins: signal transduction and O-GlcNAc. Science 291, 2376–2378. doi: 10.1126/science.1058714

Wen, L., Zang, L., Huang, K., Li, S., Wang, R., and Wang, P. G. (2016a). Efficient enzymatic synthesis of L-rhamnulose and L-fuculose. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 26, 969–972. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2015.12.051

Wen, L., Zheng, Y., Jiang, K., Zhang, M., Kondengaden, S. M., Li, S., et al. (2016b). Two-step chemoenzymatic detection of N-Acetylneuraminic Acid-alpha(2–3)-Galactose glycans. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 138, 11473–11476. doi: 10.1021/jacs.6b07132

Wu, Z., Jiang, K., Zhu, H., Ma, C., Yu, Z., Li, L., et al. (2016). Site-directed glycosylation of peptide/protein with homogeneous O-linked eukaryotic N-Glycans. Bioconjug. Chem. 27, 1972–1975. doi: 10.1021/acs.bioconjchem.6b00385

Yuzwa, S. A., Shan, X., Macauley, M. S., Clark, T., Skorobogatko, Y., Vosseller, K., et al. (2012). Increasing O-GlcNAc slows neurodegeneration and stabilizes tau against aggregation. Nat. Chem. Biol. 8, 393–399. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.797

Yuzwa, S. A., and Vocadlo, D. J. (2014). O-GlcNAc and neurodegeneration: biochemical mechanisms and potential roles in Alzheimer's disease and beyond. Chem. Soc. Rev. 43, 6839–6858. doi: 10.1039/c4cs00038b

Keywords: O-GlcNAcylation, O-GlcNAcase, sugar moiety, GlcNAc derivatives, substrate specificity

Citation: Li S, Wang J, Zang L, Zhu H, Guo J, Zhang J, Wen L, Chen Y, Li Y, Chen X, Wang PG and Li J (2019) Production of Glycopeptide Derivatives for Exploring Substrate Specificity of Human OGA Toward Sugar Moiety. Front. Chem. 6:646. doi: 10.3389/fchem.2018.00646

Received: 08 October 2018; Accepted: 12 December 2018;

Published: 14 January 2019.

Edited by:

Xuechen Li, The University of Hong Kong, Hong KongReviewed by:

Chang-Chun Ling, University of Calgary, CanadaMatthew Robert Pratt, University of Southern California, United States

Copyright © 2019 Li, Wang, Zang, Zhu, Guo, Zhang, Wen, Chen, Li, Chen, Wang and Li. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Jiajia Wang, andhbmc3N0B2aXAuaGVudS5lZHUuY24=

Peng George Wang, cHdhbmcxMUBnc3UuZWR1

Jing Li, amluZ2xpbmtAbmFua2FpLmVkdS5jbg==

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Shanshan Li2†

Shanshan Li2† Jiajia Wang

Jiajia Wang Lanlan Zang

Lanlan Zang Liuqing Wen

Liuqing Wen Xi Chen

Xi Chen Jing Li

Jing Li