- 1Hubei Key Laboratory of Natural Medicinal Chemistry and Resource Evaluation, School of Pharmacy, Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science and Technology, Wuhan, China

- 2Department of Pharmacy, the Central Hospital of Wuhan, Wuhan, China

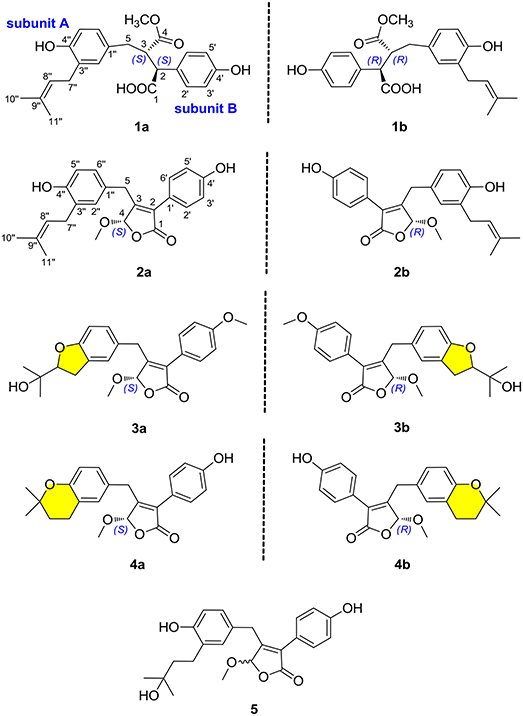

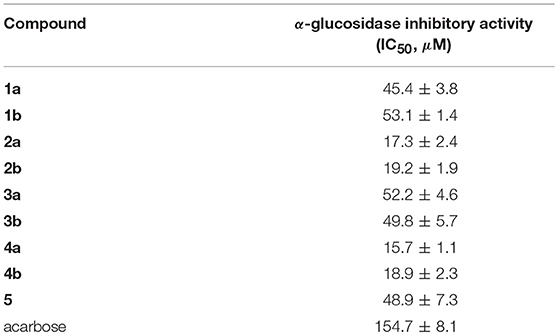

Nine novel butenolide derivatives, including four pairs of enantiomers, named (±)-asperteretones A–D (1a/1b–4a/4b), and a racemate, named asperteretone E (5), were isolated and identified from the coral-associated fungus Aspergillus terreus. All the structures were established based on extensive spectroscopic analyses, including HRESIMS and NMR data. The chiral chromatography analyses allowed the separation of (±)-asperteretones A–D, whose absolute configurations were further confirmed by experimental and calculated electronic circular dichroism (ECD) analysis. Structurally, compounds 2–5 represented the first examples of prenylated γ-butenolides bearing 2-phenyl-3-benzyl-4H-furan-1-one motifs, and their crucial biogenetically related metabolite, compound 1, was uniquely defined by an unexpected cleavage of oxygen bridge between C-1 and C-4. Importantly, (±)-asperteretal D and (4S)-4-decarboxylflavipesolide C were revised to (±)-asperteretones B (2a/2b) and D (4), respectively. Additionally, compounds 1a/1b–4a/4b and 5 were evaluated for the α-glucosidase inhibitory activity, and all these compounds exhibited potent inhibitory potency against α-glucosidase, with IC50 values ranging from 15.7 ± 1.1 to 53.1 ± 1.4 μM, which was much lower than that of the positive control acarbose (IC50 = 154.7 ± 8.1 μM), endowing them as promising leading molecules for the discovery of new α-glucosidase inhibitors for type-2 diabetes mellitus treatment.

Introduction

Diabetes mellitus (DM) is one of the most serious chronic diseases with the ever-increasing incidence rates of obesity and aging of the general population throughout the world (Kopelman, 2000) In 2013, it was estimated that over 382 million people all over the world have DM and this number is predicted to increase up to 500 million in 2030, when this disease will be excepted to be the 7th leading cause of death (Lauritano and Ianora, 2016). Globally, type-2 diabetes (non-insulin-dependent DM) covered 90–95% of all the diabetes cases (Lauritano and Ianora, 2016). Postprandial hyperglycemia is an important factor for the induction of type-2 diabetes and complications related to the diseases, such as micro- and macro-vascular diseases (Baron, 1998). A good strategy to maintain the normal level of postprandial plasma glucose is to medicate in combination with dietary restriction and an exercise plan (Kim et al., 2008). In type-2 diabetes, delaying glucose absorption after meals by inhibition of α-glucosidase is known to help the therapy (Kim et al., 2008). For diabetic patients, α-glucosidase inhibitors (AGIs) are widely applied either as monotherapy or in combination with other oral hypoglycemic agents or insulin (Hung et al., 2012). However, AGIs-induced serious liver injuries and gastrointestinal side effects restricted the clinical practice (Yin et al., 2014; Kao et al., 2016). In view of the limited number of safe anti-diabetic drugs with low toxicity and ever-increasing number of diabetic patients, the exploration for new α-glucosidase inhibitors, attracted, and still attract great interests from scientific community.

In our continuous search for chemically novel and bioactive secondary metabolites from marine fungi (Hu et al., 2014; Liu et al., 2018a,b; Yang et al., 2018), we focused our attention on a coral-associated fungus Aspergillus terreus. A systematic chemical investigation on the ethyl acetate extracts of rice medium of this fungal strain facilitated the isolation and identification of nine novel butenolide derivatives, including four pairs of enantiomers, named (±)-asperteretones A–D (1a/1b–4a/4b), and a racemate, named asperteretone E (5). Structurally, compounds 2–5 represented the first examples of prenylated γ-butenolides bearing 2-phenyl-3-benzyl-4H-furan-1-one motifs, and their crucial biogenetically related metabolite, compound 1, was uniquely defined by an unexpected cleavage of oxygen bridge between C-1 and C-4. Importantly, by an experimental validation method, (±)-asperteretal D and (4S)-4-decarboxylflavipesolide C were revised to (±)-asperteretones B (2a/2b) and D (4), respectively. Herein, the detailed isolation, structure elucidation, and α-glucosidase inhibitory activity of these compounds (Figure 1) are described.

Materials and Methods

General Experimental Procedures

Optical rotations and IR data were collected from a PerkinElmer PE-341 instrument (PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA, USA) and a Bruker Vertex 70 FT-IR spectrophotometer (Bruker, Karlsruhe, Germany) with KBr pellets, respectively. UV and ECD spectra were collected from a Varian Cary 50 UV/vis spectrophotometer (Varian, Salt Lake City, UT, USA) and a JASCO-810 spectrometer, respectively. 1D and 2D NMR spectra were measured by using a Bruker AM-400 NMR spectrometer (Bruker, Karlsruhe, Germany). The solvent or solvent impurity peaks for methanol-d4 (δH 3.31 and δC 49.0) and CDCl3 (δH 7.24 and δC 77.23) were referenced to the 1H and 13C NMR chemical shifts. High-resolution electrospray ionization mass spectrometry (HRESIMS) were measured by using a Thermo Fisher LTQ XL LC/MS (Thermo Fisher, Palo Alto, CA, USA). Column chromatography (CC) was carried out by using silica gel (200–300 mesh; Qingdao Marine Chemical Inc., China), Sephadex LH-20 (40–70 μm, Amersham Pharmacia Biotech AB, Uppsala, Sweden, Sweden), and octadecylsilyl (ODS, 50 μm, YMC Co. Ltd., Japan). Semi-preparative HPLC separations were carried out on an Agilent 1100 liquid chromatograph with a Zorbax SB-C18 (9.4 × 250 mm) and a Daicel IC column (5 μm, 4.6 × 250 mm, Daicel Chiral Technologies Co., Ltd., China) column. Thin-layer chromatography (TLC) was carried out by using silica gel 60 F254 (Yantai Chemical Industry Research Institute) and RP-C18 F254 plates (Merck, Germany).

Fungus Material

The fungus Aspergillus terreus was isolated from the soft coral Sarcophyton subviride, which was collected from the Xisha Island in the South China Sea. This strain was cultivated on potato dextrose agar (PDA) medium and identified by one of the authors (JW), based on its morphological properties and ITS sequence analysis (GenBank access no. MF972904). The fungal strain was reserved in the culture collection of Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science and Technology.

Cultivation, Extraction, and Isolation

The strain Aspergillus terreus was cultivated on PDA (Potato Dextrose Agar) medium at 28°C for 1 week to prepare the seed cultures. Agar plugs were cut into small pieces (approximately 0.5 × 0.5 × 0.5 cm3) and then was inoculated in 300 × 500 mL Erlenmeyer flasks which were previously sterilized by autoclaving, each containing 200 g rice and 200 mL distilled water. All flasks were incubated at 28°C for 28 days. Then, the whole rice solid medium was extracted seven times in 95% aqueous EtOH at room temperature, and the solvent was removed under reduced pressure to afford a crude extract, which was partitioned with ethyl acetate against water to obtain the ethyl acetate soluble part (1.5 kg). The organic extract was separated by silica gel CC (100–200 mesh) with a stepwise gradient elution of petroleum ether–ethyl acetate–MeOH (10:1:0, 7:1:0, 5:1:0, 3:1:0, 1:1:0, 2:2:1, 1:1:1) to afford seven fractions (A–G).

Fraction C (75 g) was separated by an RP-C18 column using MeOH–H2O (from 20:80 to 100:0, v/v) to give five main fractions (C1–C5). Fraction C3 (2.3 g) was further purified by Sephadex LH-20 using CH2Cl2-MeOH (1:1, v/v) to yield two fractions (C3.1–C3.2). Fraction C3.2 was applied to silica gel CC eluted with petroleum ether–ethyl acetate (stepwise 4:1–1:1) to furnish four additional fractions (C3.2.1–C3.2.4). Repeated purification of fraction C3.2.3 (92 mg) by semi-preparative HPLC with CH3CN–H2O (50:50, v/v, 3.0 mL/min) to yield compounds 2 (4.8 mg; tR 12.5 min) and 4 (4.0 mg; tR 28.2 min). Afterwards, compound 2 was further purified by chiral HPLC using a Daicel IC column (isopropanol–n-hexane, 8:92, v/v, 2.0 mL/min) to give 2a (2.2 mg; tR 60.7 min) and 2b (2.3 mg; tR 55.2 min). The enantiomers 4a (1.8 mg; tR 50.5 min) and 4b (2.0 mg; tR 41.8 min) were obtained by chiral HPLC separation of compound 4 using a Daicel IC column eluted with isopropanol–n-hexane (8:92, v/v, 2.0 mL/min).

Fraction D (198 g) was subjected to an RP-C18 column eluted with MeOH–H2O (from 20:80 to 100:0, v/v) to yield five fractions (D1–D5). Fraction D4 (2.4 g) was applied to Sephadex LH-20 eluted with CH2Cl2-MeOH (1:1, v/v) and further purified by semi-preparative HPLC using CH3CN–H2O (60:40, v/v, 3.0 mL/min) to yield a racemic mixture 3 (9.6 mg; tR 38.2 min). The enantiomers 3a (1.1 mg; tR 12.5 min) and 3b (1.8 mg; tR 14.8 min) were further purified by chiral HPLC using a Daicel IC column eluted with isopropanol–n-hexane (8:92, v/v, 2.0 mL/min).

Fraction E (186 g) was chromatographed on silica gel CC (CH2Cl2-MeOH, 1:0–50:1, v/v) to yield five main fractions (E1–E5). Repeated purification of fraction E5 (1.3 g) using Sephadex LH-20 with CH3OH as eluent and RP-C18 column (MeOH–H2O, from 30:70 to 100:0, v/v) to give three mixtures (E5.1–E5.3). Fractions E5.1 (210 mg) was subjected to semi-preparative HPLC (MeOH–H2O, 60:40, v/v, 3.0 mL/min) to afford compound 1 (6.7 mg; tR 43 min). Subsequently, compound 1 was subjected to chiral HPLC using a Daicel IC column (isopropanol–n-hexane, 7:93, v/v, 2.0 mL/min), resulting in the separation of 1a (2.7 mg; tR 12.4 min) and 1b (2.5 mg; tR 16.2 min). A racemic mixture 5 (3.2 mg) was isolated by semi-preparative HPLC (MeOH–H2O, 70:30, v/v, 3.0 mL/min) from fraction E5.2 (54.5 mg).

(±)-Asperteretone A (1). White, amorphous powder; [α] 0 (c 0.1, MeOH); UV (MeOH) λmax (log ε) = 202 (4.63), 229 (4.06), 279 (3.43) nm; IR νmax = 3435, 2925, 1718, 1623, 1511, 1446, 1381, 1257, 1179, 1047, 829, 573 cm−1; HRESIMS m/z 421.1622 [M + Na]+ (calcd for C23H26O6Na, 421.1627); For 1H NMR and 13C NMR data, see Table 1.

(−)-Asperteretone A (1a). White, amorphous powder; [α] −34 (c 0.1, MeOH); ECD (c 0.1, MeOH) = Δε210 −0.85, Δε227 −1.52.

(+)-Asperteretone A (1b). White, amorphous powder; [α] +37 (c 0.1, MeOH); ECD (c 0.1, MeOH) = Δε209 +6.18, Δε226 +5.80.

(±)-Asperteretone B (2). White, amorphous powder; [α] 0 (c 0.1, MeOH); UV (MeOH) λmax (log ε) = 202 (4.21), 215 (3.85), 285 (3.50) nm; IR νmax = 3425, 2927, 2853, 1747, 1611, 1514, 1440, 1372, 1342, 1269, 1204, 1144, 1113, 1020, 987, 946, 839, 789, 557, 534 cm−1; HRESIMS m/z 403.1526 [M + Na]+ (calcd for C23H24O5Na, 403.1521); For 1H NMR and 13C NMR data, see Table 2.

(−)-Asperteretone B (2a). White, amorphous powder; [α] −140 (c 0.1, MeOH); ECD (c 0.1, MeOH) = Δε207−16.99, Δε232−2.90, Δε282−10.57.

(+)-Asperteretone B (2b). White, amorphous powder; [α] +136 (c 0.1, MeOH); ECD (c 0.1, MeOH) = Δε207 +10.92, Δε232 +3.56, Δε282 +8.98.

(±)-Asperteretone C (3). White, amorphous powder; [α] 0 (c 0.1, MeOH); UV (MeOH) λmax (log ε) = 202 (4.23), 223 (3.77), 285 (3.67) nm; IR νmax = 3483, 2991, 2952, 2878, 1712, 1637, 1453, 1434, 1396, 1351, 1267, 1170, 1133, 1008, 988, 967, 942, 900, 838, 736, 702, 605, 564 cm−1; HRESIMS m/z 411.1802 [M + H]+ (calcd for C24H27O6, 411.1808) and m/z 433.1635 [M + Na]+ (calcd for C24H26O6Na, 433.1627); For 1H NMR and 13C NMR data, see Table 1.

(−)-Asperteretone C (3a). White, amorphous powder; [α] −135 (c 0.1, MeOH); ECD (c 0.1, MeOH) = Δε207 −9.13, Δε232 −3.29, Δε282 −5.67.

(+)-Asperteretone C (3b). White, amorphous powder; [α] +137 (c 0.1, MeOH); ECD (c 0.1, MeOH) = Δε208 +9.79, Δε236 +1.78, Δε284 +8.67.

(±)-Asperteretone D (4). White, amorphous powder; [α] 0 (c 0.1, MeOH); UV (MeOH) λmax (log ε) = 202 (4.62), 221 (4.32), 283 (4.05) nm; IR νmax = 3432, 2974, 2930, 2853, 1756, 1616, 1503, 1444, 1374, 1263, 1208, 1158, 1116, 1028, 994, 837, 670 cm−1; HRESIMS m/z 381.1692 [M + H]+ (calcd for C23H25O5, 381.1702) and m/z 403.1513 [M + Na]+ (calcd for C23H24O5Na, 403.1521); For 1H NMR and 13C NMR data, see Table 1.

(−)-Asperteretone D (4a). White, amorphous powder; [α] −120 (c 0.1, CH2Cl2); ECD (c 0.1, MeOH) = Δε207−13.10, Δε232−3.81, Δε283−7.07.

(+)-Asperteretone D (4b). White, amorphous powder; [α] +116 (c 0.1, CH2Cl2); ECD (c 0.1, MeOH) = Δε207 +9.95, Δε232 +4.60, Δε282 +9.14.

Asperteretone E (5). White, amorphous powder; [α] 0 (c 0.1, MeOH); UV (MeOH) λmax (log ε) = 202 (4.55), 218 (4.29), 285 (4.06) nm; IR νmax = 3428, 2965, 2926, 2853, 1750, 1615, 1512, 1441, 1373, 1266, 1207, 1109, 1032, 946, 837, 565 cm−1; HRESIMS m/z 421.1626 [M + Na]+ (calcd for C23H26O6Na, 421.1627); For 1H NMR and 13C NMR data, see Table 1.

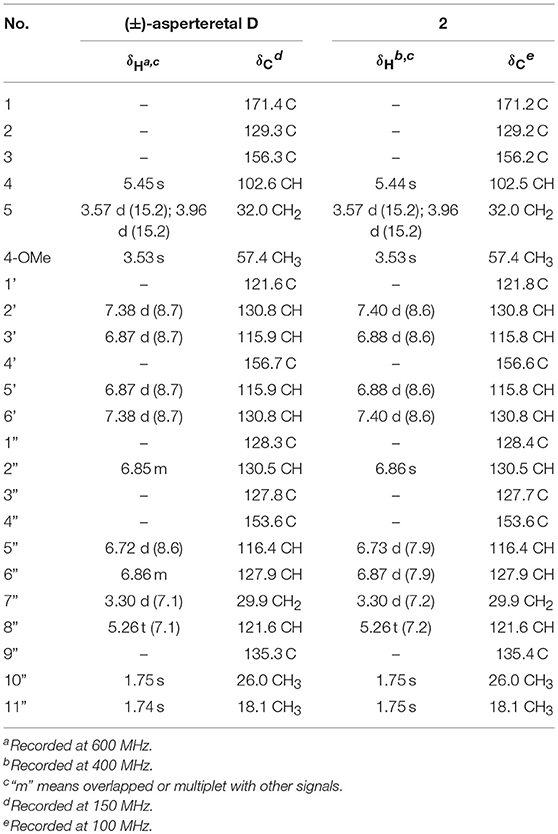

Table 2. Comparison of the 1H and 13C NMR data for reported (±)-asperteretal D and 2 in CDCl3 (δ in ppm and J in Hz).

ECD Calculations

The theoretical calculations of compounds 1a/1b and 2a/2b were performed using Gaussian 09 and figured using GaussView 5.0 (He et al., 2017a,b,c; Hu et al., 2017). Conformation search using molecular mechanics calculations was performed in the Discovery Studio 3.5 Client with MMFF force field with 20 kcal mol−1 upper energy limit (Smith and Goodman, 2010). The optimized conformation geometries and thermodynamic parameters of all selected conformations were provided. The predominant conformers were optimized at B3LYP/6-31G(d,p) level. The theoretical calculation of ECD was performed using time dependent Density Functional Theory (TDDFT) at the B3LYP/6-31G(d,p) level in MeOH with PCM model (Miertus et al., 1981). The ECD spectra of compounds 1a/1b and 2a/2b were obtained by weighing the Boltzmann distribution rate of each geometric conformation (Tähtinen et al., 2003).

The ECD spectra were simulated by overlapping Gaussian functions for each transition according to:

The σ represented the width of the band at 1/e height, and ΔEi and Ri were the excitation energies and rotational strengths for transition i, respectively. Rvel had been used in this work.

α-Glucosidase Inhibitory Assay

The α-glucosidase enzyme from Saccharomyces cerevisiae (Sigma Aldrich, USA) solution (1.5 U/mL) was prepared by dissolving the α-glucosidase in 200 M phosphate buffer (pH 6.8). The α-glucosidase enzyme solution (20 μL), test compounds (10 μL) and buffer (40 μL) were pipetted and mixed in a 96 well microtiter plate. The mixture was incubated at 37°C for 10 min. After incubation, p-nitrophenyl-α-D-glucopyranoside (PNP-G) substrate solution (10 μL, in 20 mM phosphate buffer) was added. The increment of absorbance due to the hydrolysis of PNP-G by α-glucosidase was measured at the wavelength of 410 nm with a microplate reader (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA). Acarbose was used as a positive control and averages of three replicates were calculated. The α-glucosidase inhibitory activity was expressed as percentage inhibition and was calculated using the following formula: inhibition (%) = [1–(ODsample/ODblank)] × 100. The half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) was calculated as the compound concentration that is required for 50% inhibition, and the IC50 value of the acarbose was 154.7 ± 8.1 μM.

Molecular Docking Simulation

The virtual docking was implemented in the Surflex-Dock module of the FlexX/Sybyl software, which is a fast docking method that allows sufficient flexibility of ligands and keeps the target protein rigid. Molecules were built with Chemdraw and optimized at molecular mechanical and semiempirical level by using Open Babel GUI. The crystallographic ligands were extracted from the active site and the designed ligands were modeled. All the hydrogen atoms were added to define the correct ionization and tautomeric states, and the carboxylate, phosphonate and sulphonate groups were considered in their charged form. In the docking calculation, the default FlexX scoring function was used for exhaustive searching, solid body optimizing and interaction scoring. Finally, the ligands with the lowest-energy and the most favorable orientation were selected.

Results and Discussion

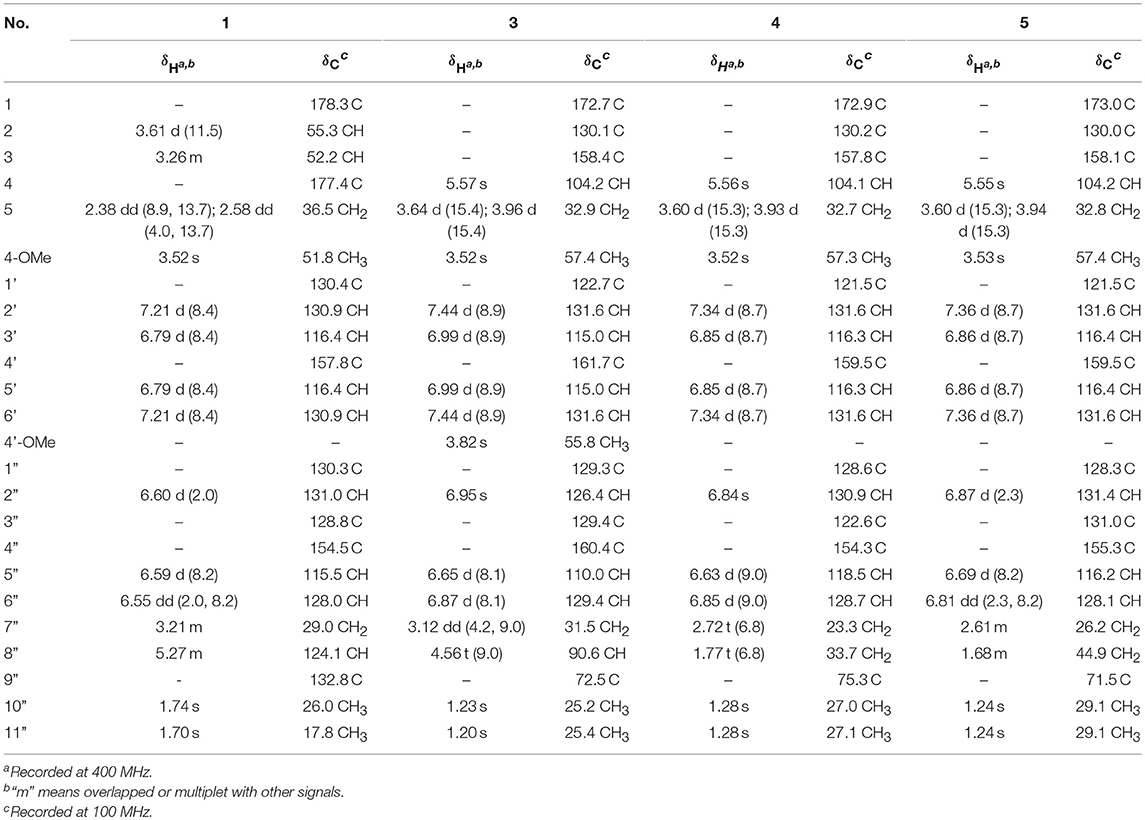

(±)-Asperteretone A (1a/1b) were obtained as white, amorphous powders. The molecular formula C23H26O6 was deduced from the HRESIMS data at m/z 421.1622 [M + Na]+ (calcd for C23H26O6Na, 421.1627), requiring 11 degrees of unsaturation. Its IR spectrum displayed intense absorption bands for hydroxyl (3,435 cm−1), carbonyl (1,718 cm−1), and aromatic ring (1,623 and 1,511 cm−1). The 1H NMR spectrum (Table 1) of 1 showed characterized signals for a para-disubstituted phenyl group at δH 7.21 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, H-2', 6') and 6.79 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, H-3', 5'), a 1,3,4-trisubstituted phenyl group at δH 6.60 (d, J = 2.0 Hz, H-2”), 6.59 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, H-5”), and 6.55 (dd, J = 2.0, 8.2 Hz, H-6”), a prenyl group at δH 3.21 (m, H2-7”), 5.27 (m, H-8”), 1.74 (s, H3-10”), and 1.70 (s, H3-11”), a methoxy group at δH 3.52 (s, OMe-4), two methines at δH 3.61 (d, J = 11.5 Hz, H-2) and 3.26 (m, H-3), and a methylene at δH 2.38 (dd, J = 8.9, 13.7 Hz, H-5) and 2.58 (dd, J = 4.0, 13.7 Hz, H-5). The 13C NMR and DEPT spectra (Table 1) of 1 showed 23 carbon resonances categorized as two methyls, two methylenes, ten methines (including eight olefinic), eight nonprotonated carbons (including six olefinic, one carboxyl, and one ester carbonyl), and one methoxyl. The diagnostic data above indicated that compound 1 was a butenolide derivative.

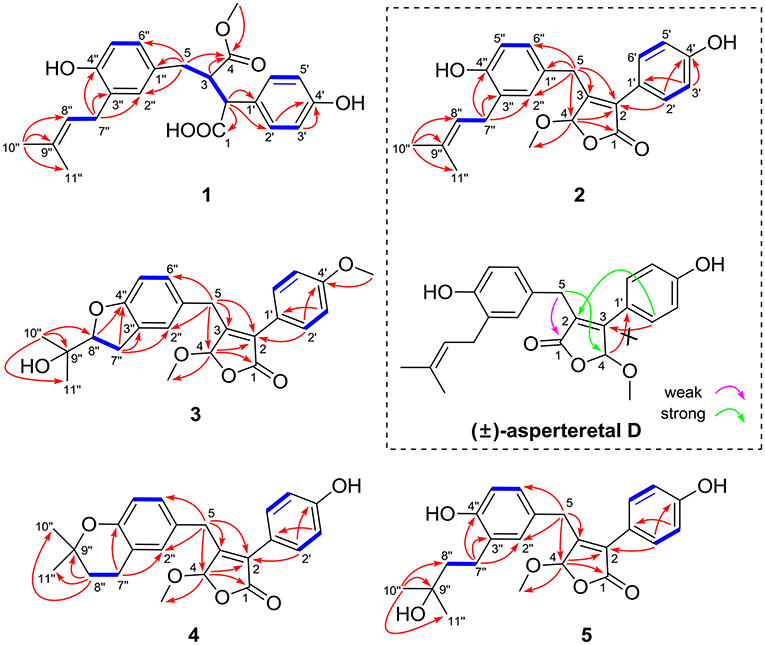

The protons and protonated carbon resonances in the NMR spectra were unambiguously assigned through the HSQC experiment. In the HMBC experiment (Figure 2), the correlations from H3-10” to C-8”, C-9”, and C-11” and from H2-7” to C-2”, C-3”, and C-4”, as well as the 1H–1H COZY correlations (Figure 2) of H2-7”/H-8” and H-5”/H-6”, confirmed the presence of the 1,3,4-trisubstituted phenyl group (subunit A) with a hydroxyl and a prenyl motif attached at C-4” and C-3”, respectively. Besides, the 1H–1H COZY correlations of H-2'/H-3' and H-5'/H-6' and HMBC correlations from both H-2' and H-3' to C-4' (δC 157.8) confirmed the presence of the para-disubstituted phenyl group (subunit B) with a hydroxyl motif attached at C-4'. Subunits A and B were connected through a “-CH2(5)-CH(3)-CH(2)-” group, as confirmed by the 1H–1H COZY correlations of H-2/H-3/H2-5 and HMBC correlations from H2-5 to C-1”, C-2”, and C-6” and from H-2 to C-1', C-2', and C-6'. In addition, the key HMBC correlations from H-3, H2-5, and OMe-4 to C-4 (δC 177.4) and H-2 to C-1 (δC 178.3) indicated that a methyl ester and a carboxyl group were attached at C-3 and C-2, respectively. Thus, the planar structure of 1 was determined.

Figure 2. Selected 1H–1H COZY (blue bold lines) and HMBC (single arrows) correlations of compounds 1–5 and key HMBC analysis in original structure (±)-asperteretal D.

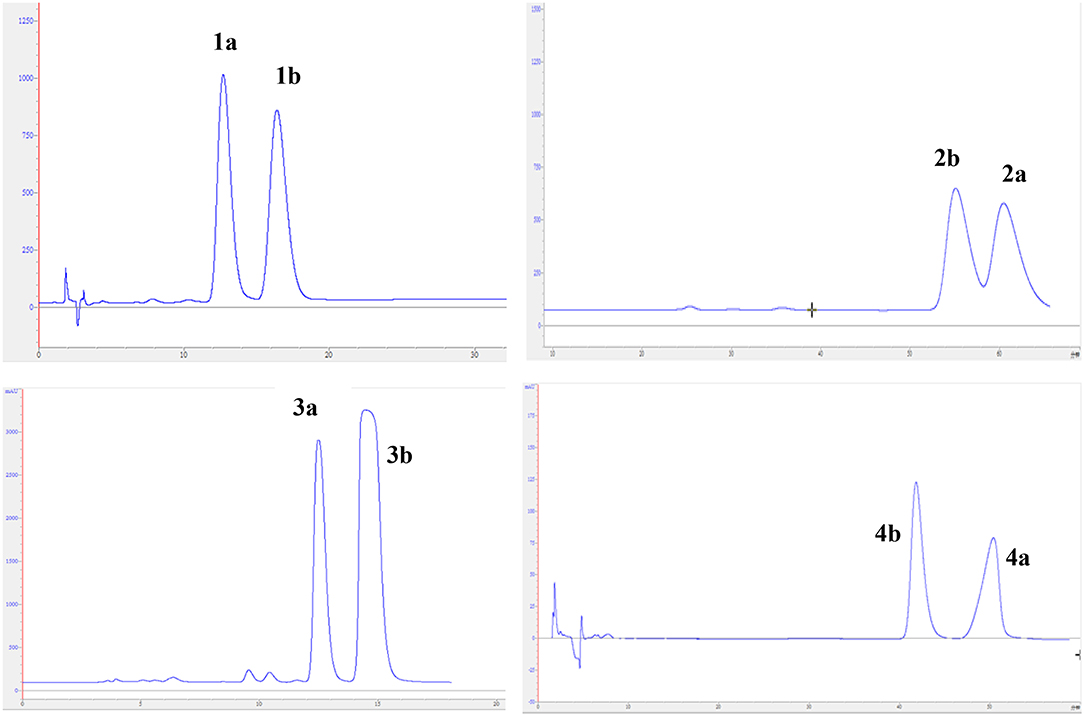

The experimental electronic circular dichroic (ECD) spectrum was measured in MeOH. Surprisingly, no apparent ECD Cotton effects were observed, suggesting that compound 1 was racemic, which adhered well to its lack of optical rotation. Subsequently, compound 1 was separated into two optically pure enantiomers, (−)-asperteretone A (1a, [α] −34) and (+)-asperteretone A (1b, [α] +37) using high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) on a Daicel IC column (Figure 3).

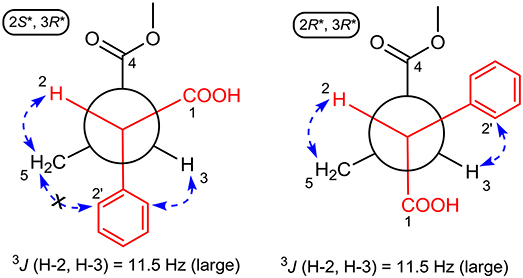

The large coupling constant (J = 11.5 Hz) suggested the trans-relationship of H-2 and H-3, thus two possible optimal conformations existed for its conformation analysis (Figure 4). When the relative configuration of 1 was 2S*,3R*, despite there were obvious NOE correlations of H-2/H2-5 and H-3/H-6' (or H-2'), the diagnostic NOE correlation of H2-5/H-2' (or H-6') was not observed in the NOESY spectrum, indicating that the assumption for 2S*,3R*-configuration should be wrong. Thus, the relative configuration of 1 was deduced to be 2R*,3R*, which was completely supported by the NOE correlations of H-2/H2-5 and H-3/H-2' (or H-6'). Accordingly, the relative configuration of 1 was determined to be 2R*,3R*.

Figure 4. ROESY correlations (dashed blue arrows) and coupling constant were used to determine the relative configuration of 1 by optimized conformation analysis for C-2 to C-3.

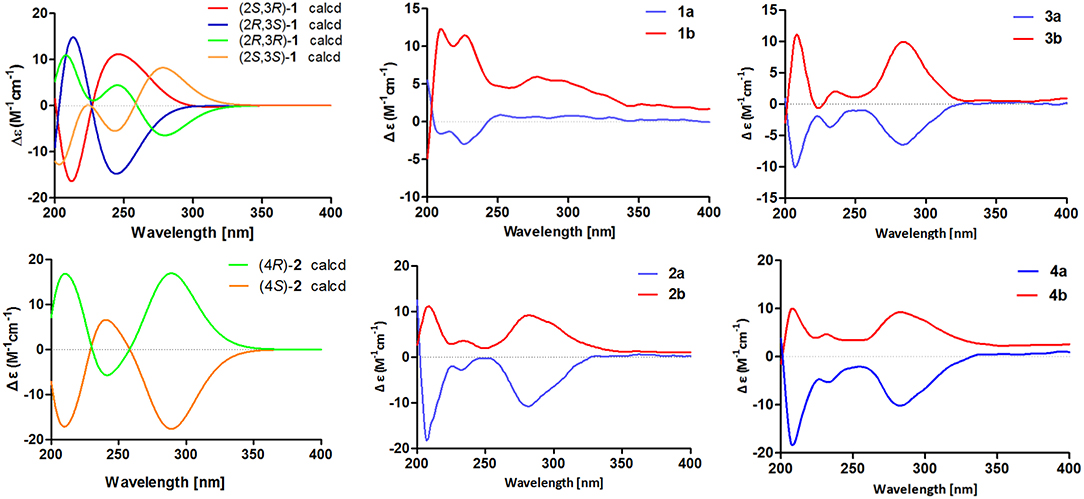

To further confirm the above conclusion and determine the absolute configurations of 1a and 1b, a time-dependent density functional theory (TDDFT) method at the at B3LYP/6-31G(d,p) level in MeOH with PCM model was performed for (2S,3R)-1, (2R,3S)-1, (2S,3S)-1, and (2R,3R)-1 (Figure 5), of which the DFT-calculated ECD spectra of (2S,3S)-1 and (2R,3R)-1 showed close similarities to the experimental ECD spectra of 1a and 1b, suggesting that the absolute structures of 1a and 1b should be assigned as (2S,3S)- and (2R,3R)-configuration, respectively.

Figure 5. Calculated ECD spectra of (2S,3R)-1, (2R,3S)-1, (2R,3R)-1, (2S,3S)-1, (4R)-2, and (4S)-2 and experimental ECD spectra of 1a/1b–4a/4b.

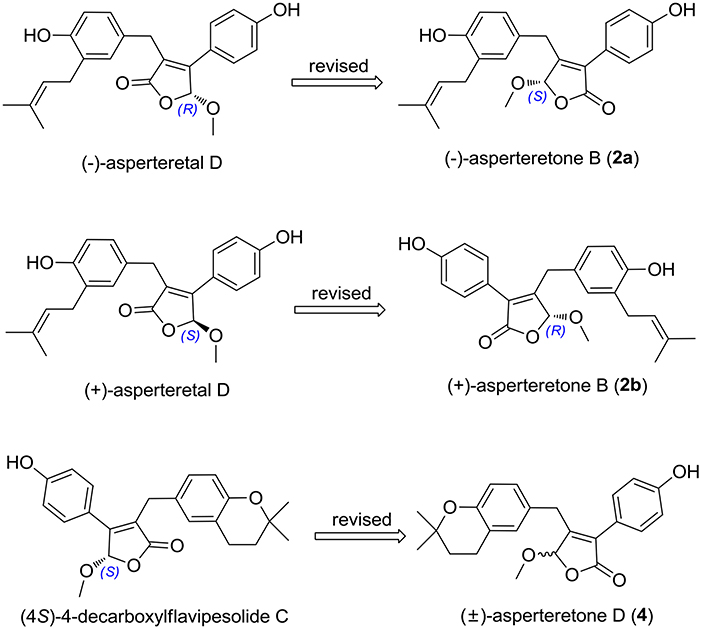

(±)-Asperteretone B (2a/2b) were also obtained as white, amorphous powders and assigned the molecular formula C23H24O5, as determined from the HRESIMS analysis at m/z 403.1526 [M + Na]+ (calcd for C23H24O5Na, 403.1521) and 13C NMR data. The 1D (Table 2) and 2D NMR spectra of 2 were completely identical to that of the reported (±)-asperteretal D (Sun Y. et al., 2018), which drove us to believe that they shared the same structures. The 1,3,4-trisubstituted phenyl group with a C-4” hydroxyl and a C-3” prenyl motif and para-disubstituted phenyl group with a C-4' hydroxyl motif were explicitly confirmed by detailed analysis of the 2D NMR data (Figure 2) of 2. However, a strong four-bond HMBC correlation from H2-5 to C-4 made us confused about the correctness of (±)-asperteretal D. After careful examination of the HMBC spectrum (Figure 2) of (±)-asperteretal D, key correlations from H-2' to C-3 and from H-4 to C-1' were not observed in the HMBC spectrum; on the contrary, two four-bond HMBC correlations from H-2' to C-2 and from H2-5 to C-4 were observed, which were also found in the HMBC spectrum of 2. These data above suggested that (±)-asperteretal D should be structurally revised from 2-benzyl-3-phenyl-type to 2-phenyl-3-benzyl-type.

The chiral resolution (Figure 3) of 2 afforded a pair of enantiomers, (±)-asperteretone B (2a/2b). To determine their absolute configurations, the ECD spectra of (4S)-2 and (4R)-2 were calculated by the TDDFT methodology, which matched well with those of (−)-asperteretone B (2a) and (+)-asperteretone B (2b), respectively, indicating that the absolute stereochemistry of 2a and 2b should be 4S- and 4R-configuration, respectively. Furthermore, by comparison of their experimental ECD spectra (Figure 5) and similar specific rotation values, the structures of (−)-asperteretal D and (+)-asperteretal D were revised to 2a and 2b (Figure 6), respectively.

Figure 6. Structure reassignments of 2-benzyl-3-phenyl-type (±)-asperteretal D and (4S)-4-decarboxylflavipesolide C to 2-phenyl-3-benzyl-type (±)-asperteretones B (2a/2b) and D (4), respectively.

(±)-Asperteretone C (3a/3b), obtained as white, amorphous powders, were determined to have the molecular formula C24H26O6, as deduced from the HRESIMS data at m/z 411.1802 [M + H]+ (calcd for C24H27O6, 411.1808) and m/z 433.1635 [M + Na]+ (calcd for C24H26O6Na, 433.1627), which was indicative of twelve degrees of unsaturation. Its high similarities of NMR data (Table 1) with those of 2 suggested that 3 was also a butenolide derivative, with the differences that the para-disubstituted phenyl group was attached with a C-4' methoxy motif in 3 rather than a C-4' hydroxyl motif in 2, and the 1,3,4-trisubstituted phenyl group attached with a C-4” hydroxyl and a C-3” prenyl motif in 2 was replaced by a 2-(2,3-dihydrobenzofuran-2-yl)propan-2-ol motif in 3, as supported by the 2D NMR spectra (Figure 2), including HMBC and 1H–1H COZY correlations. Thus, the structure of 3 was determined.

Considering the similar structural features of 2 and 3, we deduced that compound 3 was likely a racemic mixture. As expected, by chiral HPLC resolution (Figure 3), two isolates were obtained. Since no apparent Cotton effects were decisive for the absolute stereochemistry of C-8”, the experimental ECD spectra (Figure 5) of 3a and 3b were closely similar to those of (−)-asperteretone B (2a) and (+)-asperteretone B (2b), respectively, indicating that compounds 3a and 3b possessed the 4S- and 4R-configuration, respectively. Regrettably, the configuration of C-8” was difficult to be determined (Liu et al., 2018b).

(±)-Asperteretone D (4a/4b) gave the molecular formula C23H24O5, as determined by the HRESIMS analysis at m/z 381.1692 [M + H]+ (calcd for C23H25O5, 381.1702) and m/z 403.1513 [M + Na]+ (calcd for C23H24O5Na, 403.1521), corresponding to twelve degrees of unsaturation. Detailed analysis of the 1H and 13C NMR data (Tables 1, 2) of 4 and 2 suggested that they shared the similar structural features, differing in that the 1,3,4-trisubstituted phenyl group attached with a C-4” hydroxyl and a C-3” prenyl motif in 2 was replaced by the 1,3,4-trisubstituted phenyl with the fusion of gem-dimethyl substituted tetrahydropyrane ring, as supported by the HMBC correlations from H2-8” to C-9”, C-10”, and C-11” and from H2-7” to C-2” and C-4”, as well as the 1H–1H COZY correlation of H2-7”/H2-8”. Thus, the planar structure of 4 was determined.

The lack of optical rotation and no obviously observed Cotton effects in the experimental ECD spectrum suggested that compound 4 was also a racemic mixture, which was then subjected to the Daicel IC column by chiral HPLC resolution (Figure 3), thus affording a pair of enantiomers, (±)-asperteretone D (4a/4b). The ECD spectra of (−)-asperteretone D (4a) and (+)-asperteretone D (4b) matched well with those of (−)-asperteretone B (2a) and (+)-asperteretone B (2b) (Figure 5), respectively, indicating that the absolute structures of 4a and 4b should be 4S- and 4R-configuration, respectively.

Most importantly, the 1H and 13C NMR data in CDCl3 (Supplementary Materials, Figures S39, S40) of 4 were identical to those of (4S)-4-decarboxylflavipesolide C (Sun K. et al., 2018), indicating that (4S)-4-decarboxylflavipesolide C should be revised to 4 (Figure 6), as supported by the strong correlations from H2-5 (δH 3.58 and 3.99) to C-4 (δC 102.2) and from H-2' (δH 7.43) to C-2 (δC 128.9) in the HMBC spectrum of (4S)-4-decarboxylflavipesolide C, whose situation was just the same as that of (±)-asperteretal D (Sun Y. et al., 2018). The minor specific rotation value {[α] −18 (c 0.1, CH2Cl2)} of (4S)-4-decarboxylflavipesolide C was obviously different from those of 4a {[α] −120 (c 0.1, CH2Cl2)} and 4b {[α] +116 (c 0.1, CH2Cl2)}, indicating that (4S)-4-decarboxylflavipesolide C should be a racemic mixture with unsymmetrical amounts rather than a pure substance.

Asperteretone E (5), obtained as a white, amorphous powder, was found to have a molecular formula of C23H26O6 with 11 degrees of unsaturation, as deduced from the HRESIMS analysis at m/z 421.1626 [M + Na]+ (calcd for C23H26O6Na, 421.1627). Side-by-side comparison of the 1H and 13C NMR data (Tables 1, 2) of 5 with those of 2, suggesting that they shared the same core skeleton, with the only difference being that the Δ8″, 9″ double bond in 2 was replaced by a methylene (δC 44.9, C-8”) and an oxygenated tertiary carbon (δC 71.5, C-9”) in 5, as supported by the HMBC correlations (Figure 2) from H3-10” to C-8”, C-9”, and C-11”. Thus, the structure of compound 5 was determined.

The optical rotation of zero in MeOH and inapparent Cotton effects in the ECD curve highlighted that 5 was racemic. Unluckily, despite for many attempts for several chiral columns using various mobile phase systems, we still failed to obtain the enantiomers of 5, which might own to that the rapid interconversion of these two enantiomers in the solvents prevented the separation on chiral columns.

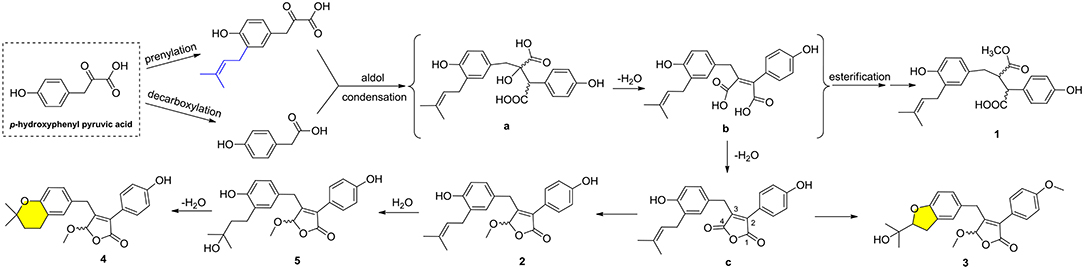

Compounds 1–5 represented two special classes of 7,8-dimeric phenylpropanoids with unexpected architectures, and their plausible biogenetic pathways were proposed as follows (Scheme 1): two molecules, p-hydroxyphenyl pyruvic acid, underwent prenylation and decarboxylation reactions, respectively, followed by aldol condensation and dehydration reactions to create intermediate b. Alternatively, a further dehydration reaction of b could generate an acid anhydride-containing intermediate c, which could furnish 2–5 through a series of reduction, cyclization, esterification, and so on. Meanwhile, the esterification at C-4 and reduction of Δ2, 3 double bond could from 1, which was identified as a crucial biogenetically related metabolite, was the first report of 2,3-disubstituted butenolide derivatives with an unexpected cleavage of oxygen bridge between C-1 and C-4. This finding would greatly expand the chemical space and biosynthesis study for butenolide derivatives.

Biological Evaluation of Compounds 1a/1b–4a/4b and 5

Compounds 1a/1b–4a/4b and 5 were evaluated for the α-glucosidase inhibitory activity. As shown in Table 3, all the compounds exhibited potent inhibitory potency against α-glucosidase, with IC50 values ranging from 15.7 ± 1.1 to 53.1 ± 1.4 μM, which was much lower than that of the positive control acarbose (IC50 = 154.7 ± 8.1 μM). All enantiomers displayed nearly horizontal IC50 values against α-glucosidase inhibitory activity, indicating that the difference of chirality might have a negligible impact on the activity. Most importantly, compounds 1a/1b–4a/4b and 5 may provide novel chemical scaffolds for the discovery of new α-glucosidase inhibitors.

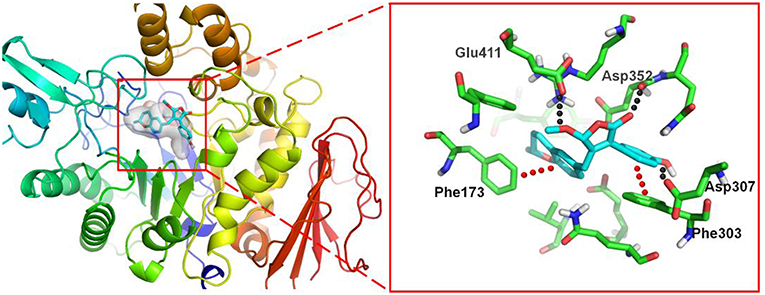

To investigate the binding mode of these compounds with α-glucosidase, molecular docking study was carried out by using the SYBYL 2.0 software. Due to the unavailable of crystal structure of α-glucosidase from Saccharomyces cerevisiae, the crystal structure of isomaltase (PDB ID: 3A4A) from S. cerevisiae, which is 84% similar to that of S. cerevisiae α-glucosidase, was conducted as docking model (Shen et al., 2015). The theoretical binding mode between 4a and the enzyme was shown in Figure 7. Compound 4a adopted a “V-shaped” conformation in the pocket. Detailed analysis showed that the phenolic group and benzopyran group of 4a formed π-π stacking interaction with the residue Phe303 and Phe173, respectively. It was also shown that the residue Asp307, Asp352, and Glu411 formed key hydrogen bonds with 4a, which were the main interactions between 4a and the enzyme. All these interactions helped 4a to anchor in the binding site of the enzyme.

Figure 7. 3D docking pose shows the interaction of 4a in the binding site of the enzyme from Saccharomyces cerevisiae (PDB ID: 3A4A): the left side shows the global view of the enzyme; the right side shows an expanded view of 4a in the binding site.

Conclusions

In conclusion, nine novel butenolide derivatives belonging to two undescribed structural types, including four pairs of enantiomers (1a/1b–4a/4b) and a racemate (5), were isolated from the coral-associated fungus Aspergillus terreus. More importantly, (±)-asperteretal D and (4S)-4-decarboxylflavipesolide C were structurally revised to 2a/2b and 4, respectively. This study further enriched secondary metabolites in the Aspergillus species and was also a strong structural supplement to the new class of γ-butenolides. In addition, bioactivity evaluation results showed that all the isolates exhibited potent α-glucosidase inhibitory activity with IC50 values ranging from 15.7 ± 1.1 to 53.1 ± 1.4 μM. On the background that DM is becoming a global public health problem and more new effective therapeutic agents are in the urgent need, our findings provide a basis for further development and utilization of butenolide derivatives as source of potential α-glucosidase inhibitors as therapeutic agents for type-2 diabetes mellitus.

Author Contributions

ML and CQ contributed to the extraction, isolation, identification, and manuscript preparation. WS contributed to the α-glucosidase inhibitory activity test. LS contributed to the fungal isolation and fermentation. JW advised and assisted Liu's experiments. JL contributed to the ECD calculations. YL contributed to the molecular docking experiment. YX contributed to the structure identification of isolated compounds. ZH guided Liu's experiments and wrote the manuscript. YZ designed the experiments and revised the manuscript.

Funding

We greatly acknowledge the financial support from the National Science Fund for Distinguished Young Scholars (No. 81725021), the Innovative Research Groups of the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81721005), the Program for Changjiang Scholars of Ministry of Education of the People's Republic of China (No. T2016088), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 21702067, 81573316, 81703580, and 81502943), the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation Funded Project (Nos. 2017M610479 and 2018T110777), the Academic Frontier Youth Team of HUST, and the Integrated Innovative Team for Major Human Diseases Program of Tongji Medical College (HUST).

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We are also thankful to the Analytical and Testing Center at Huazhong University of Science and Technology for assistance in measuring the CD and IR data.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fchem.2018.00422/full#supplementary-material

References

Baron, A. D. (1998). Postprandial hyperglycaemia and α-glucosidase inhibitors. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pr. 40, 51–55. doi: 10.1016/S0168-8227(98)00043-6

He, Y., Hu, Z., Li, Q., Huang, J., Li, X. N., Zhu, H., et al. (2017a). Bioassay-guided isolation of antibacterial metabolites from Emericella sp. TJ29. J. Nat. Prod. 80, 2399–2405. doi: 10.1021/acs.jnatprod.7b00077

He, Y., Hu, Z., Sun, W., Li, Q., Li, X. N., Zhu, H., et al. (2017b). Spiroaspertrione A, a Bridged Spirocyclic meroterpenoid, as a potent potentiator of oxacillin against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus from Aspergillus sp. TJ23. J. Org. Chem. 82, 3125–3131. doi: 10.1021/acs.joc.7b00056

He, Y., Zheng, M., Li, Q., Hu, Z., Zhu, H., Liu, J., et al. (2017c). Asperspiropene A, a novel fungal metabolite as an inhibitor of cancer-associated mutant isocitrate dehydrogenase 1. Org. Chem. Front. 4, 1137–1144. doi: 10.1039/c6qo00847j

Hu, Z., Wu, Y., Xie, S., Sun, W., Guo, Y., Li, X. N., et al. (2017). Phomopsterones A and B, two functionalized ergostane-type steroids from the endophytic fungus Phomopsis sp. TJ507A. Org. Lett. 19, 258–261. doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.6b03557

Hu, Z. X., Xue, Y. B., Bi, X. B., Zhang, J. W., Luo, Z. W., Li, X. N., et al. (2014). Five new secondary metabolites produced by a marine-associated fungus, Daldinia eschscholzii. Mar. Drugs 12, 5563–5575. doi: 10.3390/md12115563

Hung, H. Y., Qian, K., Morris-Natschke, S. L., Hsu, C. S., and Lee, K. H. (2012). Recent discovery of plant-derived anti-diabetic natural products. Nat. Prod. Rep. 29, 580–606. doi: 10.1039/C2NP00074A

Kao, C. C., Wu, P. C., Wu, C. H., Chen, L. K., Chen, H. H., Wu, M. S., et al. (2016). Risk of liver injury after α-glucosidase inhibitor therapy in advanced chronic kidney disease patients. Sci. Rep. 6:18996. doi: 10.1038/srep18996

Kim, K. Y., Nam, K. A., Kurihara, H., and Kim, S. M. (2008). Potent α-glucosidase inhibitors purified from the red alga Grateloupia elliptica. Phytochemistry 69, 2820–2825. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2008.09.007

Lauritano, C., and Ianora, A. (2016). Marine organisms with anti-diabetes properties. Mar. Drugs 14:220. doi: 10.3390/md14120220

Liu, M., Sun, W., Wang, J., He, Y., Zhang, J., Li, F., et al. (2018a). Bioactive secondary metabolites from the marine-associated fungus Aspergillus terreus. Bioorg. Chem. 80, 525–530. doi: 10.1016/j.bioorg.2018.06.029

Liu, M., Zhou, Q., Wang, J., Liu, J., Qi, C., Lai, Y., et al. (2018b). Anti-inflammatory butenolide derivatives from the coral-derived fungus Aspergillus terreus and structure revisions of aspernolides D and G, butyrolactone VI and 4',8”-diacetoxy butyrolactone VI. RSC Adv. 8, 13040–13047. doi: 10.1039/c8ra01840e

Miertus, S., Scrocc, E., and Tomasi, J. (1981). Electrostatic interaction of a solute with a continuum. A direct utilizaion of AB initio molecular potentials for the prevision of solvent effects. J. Chem. Phys. 55, 117–129. doi: 10.1016/0301-0104(81)85090-2

Shen, X., Saburi, W., Gai, Z., Kato, K., Ojima-Kato, T., Yu, J., et al. (2015). Structural analysis of the α-glucosidase HaG provides new insights into substrate specificity and catalytic mechanism. Acta Cryst. 71, 1382–1391. doi: 10.1107/S139900471500721X

Smith, S. G., and Goodman, J. M. (2010). Assigning stereochemistry to single diastereoisomers by GIAO NMR calculation: the DP4 probability. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 132, 12946–12959. doi: 10.1021/ja105035r

Sun, K., Zhu, G., Hao, J., Wang, Y., and Zhu, W. (2018). Chemical-epigenetic method to enhance the chemodiversity of the marine algicolous fungus, Aspergillus terreus OUCMDZ-2739. Tetrahedron 74, 83–87. doi: 10.1016/j.tet.2017.11.039

Sun, Y., Liu, J., Li, L., Gong, C., Wang, S., Yang, F., et al. (2018). New butenolide derivatives from the marine sponge-derived fungus Aspergillus terreus. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 28, 315–318. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2017.12.049

Tähtinen, P., Bagno, A., Klika, K. D., and Pihlaja, K. (2003). Modeling NMR parameters by DFT methods as an aid to the conformational analysis of cis-fused 7a(8a)-methyl octa(hexa)hydrocyclopenta[d][1,3]oxazines and [3,1]benzoxazines. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 125, 4609–4618. doi: 10.1021/ja021237t

Yang, B., Sun, W., Wang, J., Lin, S., Li, X. N., Zhu, H., et al. (2018). A new breviane spiroditerpenoid from the marine-derived fungus Penicillium sp. TJ403-1. Mar. Drugs 16:110. doi: 10.3390/md16040110

Keywords: coral-associated fungus, Aspergillus terreus, butenolide derivatives, structure reassignments, α-glucosidase inhibitors

Citation: Liu M, Qi C, Sun W, Shen L, Wang J, Liu J, Lai Y, Xue Y, Hu Z and Zhang Y (2018) α-Glucosidase Inhibitors From the Coral-Associated Fungus Aspergillus terreus. Front. Chem. 6:422. doi: 10.3389/fchem.2018.00422

Received: 24 July 2018; Accepted: 24 August 2018;

Published: 13 September 2018.

Edited by:

Xian-Wen Yang, Third Institute of Oceanography, State Oceanic Administration, ChinaReviewed by:

Junfeng Wang, South China Sea Institute of Oceanology (CAS), ChinaValeria Costantino, Università degli Studi di Napoli Federico II, Italy

Copyright © 2018 Liu, Qi, Sun, Shen, Wang, Liu, Lai, Xue, Hu and Zhang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Zhengxi Hu, hzx616@126.com

Yonghui Zhang, zhangyh@mails.tjmu.edu.cn

† These authors have contributed equally to this work

Mengting Liu1†

Mengting Liu1† Weiguang Sun

Weiguang Sun Ling Shen

Ling Shen Junjun Liu

Junjun Liu Yongbo Xue

Yongbo Xue Zhengxi Hu

Zhengxi Hu Yonghui Zhang

Yonghui Zhang