- 1Duke Molecular Physiology Institute, Duke University School of Medicine, Durham, NC, United States

- 2Division of Hematology, Department of Medicine, Duke University School of Medicine, Durham, NC, United States

- 3Duke Center for the Study of Aging and Human Development, Duke University School of Medicine, Durham, NC, United States

Our understanding of the molecular basis of aging has greatly increased over the past few decades. In this review, we provide an overview of the key signaling pathways associated with aging, and whose modulation has been shown to extend lifespan in a range of model organisms. We also describe how these pathways converge onto autophagy, a catabolic process that functions to recycle dysfunctional cellular material and maintains energy homeostasis. Finally, we consider various approaches of therapeutically modulating these longevity pathways, highlighting exercise as a potent geroprotector.

Introduction

In the past two decades, the molecular signatures of aging have been started to be uncovered. A remarkable conservation of these cell signaling pathways has been shown across various invertebrate and vertebrate species (Kenyon, 2010). Autophagy is a cellular process that has emerged as a nexus at which these various pathways have been shown to converge. Autophagy is the catabolic process by which the cell eliminates unnecessary cellular components to maintain energy homeostasis and prevent the build-up of toxic material. There are three forms of autophagy—macroautophagy, microautophagy, and chaperone-mediated autophagy. In this review, we will only discuss macroautophagy (which we will henceforth refer to simply as “autophagy”). This review will provide an overview of the cell signaling pathways that are associated with longevity, and discuss how they all converge onto autophagy. We will also discuss how established anti-aging approaches including exercise, caloric restriction, and pharmaceutical therapeutics affect these pathways to regulate autophagy in ways that are geroprotective and possibly longevity-enhancing.

Evidence That Autophagy is Associated With and Necessary for Longevity

Autophagic activity has been shown to decline with age in various animal models. For example, body-wide quantification of autophagic flux in Caenorhabditis elegans revealed a general decline in activity in various tissues, including the intestine and neurons (Chang et al., 2017). A similar decline in function has been observed in mammals. For example, electron microscopy analysis of aged mouse livers revealed a depression in the rate of autophagic vesicle formation (Terman, 1995).

Various groups have identified a necessary role of autophagy in mediating the effects of longevity-enhancing mutations. The Levine group was the first to demonstrate that inhibiting autophagy in a long-lived mutant model nullifies the longevity-promoting effects of the mutation. C. elegans worms that carry a loss-of-function mutation in their daf-2 gene [which encodes for a common single insulin/Insulin-like Growth Factor (IGF)-1 Receptor in this organism] live significantly longer than their wild-type counterparts. They demonstrated that RNAi-mediated knockdown of the autophagy gene bec-1 significantly reduced the lifespan of the daf-2 mutants, clearly identifying autophagy as a process that is required for the increased longevity of this mutant (Melendez et al., 2003).

To demonstrate a causal relationship between autophagy and longevity, some groups have evaluated the effects of overexpressing autophagy genes. A positive relationship between autophagic activity and lifespan was first demonstrated in Drosophila. Neuron-specific overexpression of the Atg8a gene resulted both in an increase in lifespan and a reduction in the accumulation of toxic protein aggregates in neurons (Simonsen et al., 2008). Similarly, body-wide overexpression of Atg5 resulted in a significant increase in lifespan in mice (Pyo et al., 2013). Increase in autophagy via disruption of the beclin1-BCL2 complex has been shown to promote both healthspan and lifespan in mice (Fernandez et al., 2018).

Autophagy and the Hallmarks of Aging

Guido Kroemer and colleagues have recently published an excellent overview of the molecular underpinnings of aging, in which they enumerate the following nine hallmarks of aging—genomic instability, telomere shortening, epigenetic alterations, loss of proteostasis, dysregulated nutrient sensing, mitochondrial dysfunction, cell senescence, stem cell loss, and altered intercellular communication (Lopez-Otin et al., 2013). Remarkably, autophagy has been shown to be intimately involved in nearly all of these processes. Autophagy can mitigate the effects of genomic instability by reducing the production of DNA-damaging reactive oxygen species (ROS) production, and by promoting the recycling of DNA repair proteins (Vessoni et al., 2013). Although autophagy is unable to revert or stall telomere attrition, recent work has shown that telomere dysfunction directly stimulates autophagy to promote the death of precancerous cells (Nassour et al., 2019). While autophagy is not thought to have a direct relationship with epigenetic alterations, it has canonical roles in maintaining proteostasis (Kern and Behl, 2019), nutrient sensing (Dagon et al., 2015), and mitochondrial health via mitophagy (Palikaras et al., 2018). While the relationship between autophagy and senescence is complex and requires further disentangling, autophagy has been shown to play an essential role in the maintenance of stem cells (Boya et al., 2018). Finally, autophagy maintains proper immune function (a key component of intercellular communication) by preserving phagocytic activity and controlling levels of inflammation (Cuervo and Macian, 2014). In summary, autophagy has been shown to counter the effects of the majority of the presented hallmarks of aging.

Longevity Pathways and Autophagy

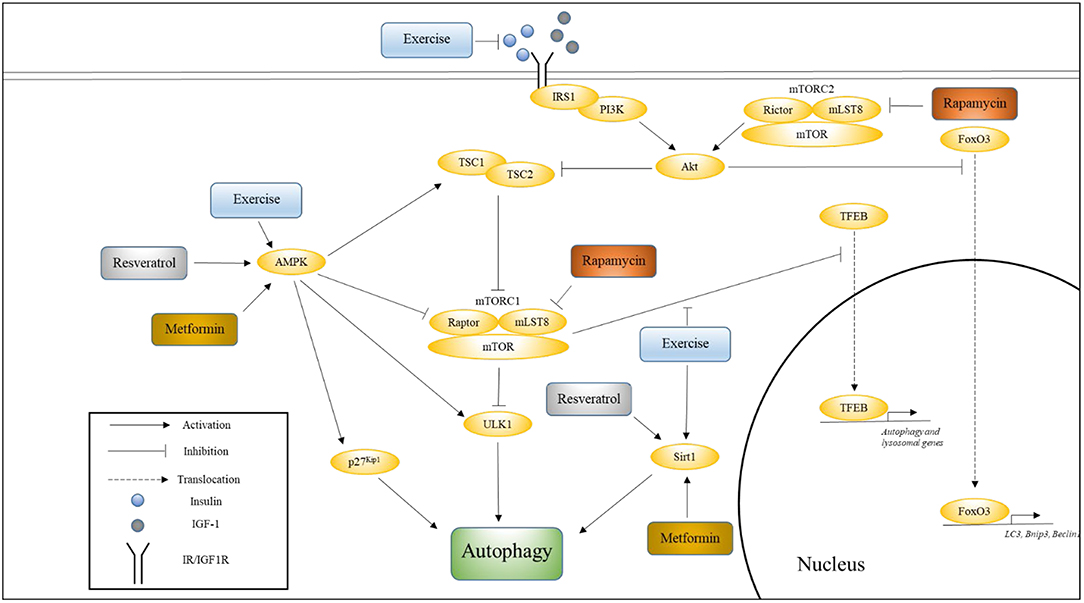

Four well-studied pathways that are known to regulate aging, and whose modulation has been shown to influence the rate of aging are Insulin/IGF-1, mechanistic target of rapamycin (mTOR), AMP-activating protein kinase (AMPK), and Sirtuin pathways (Kenyon, 2010). In this section, we will discuss the relationship between each of these pathways and longevity, their effects on autophagy, and the effects of aging and exercise on these pathways with respect to autophagy. Figure 1 illustrates how these various pathways converge onto, and activate, autophagy.

Figure 1. The influence of exercise on cell signaling pathways that regulate autophagy. This figure shows how various pathways associated with longevity converge onto autophagy, and how exercise influences these pathways. Also indicated are the nodes upon which Metformin, Rapamycin, and Resveratrol are thought to act. Please see text for details.

Insulin/IGF-1 Signaling (IIS)

IIS and Longevity

The insulin/IGF-1 (IIS) pathway was the first pathway to be shown to affect aging (Kenyon et al., 1993). C. elegans worms with a loss-of-function mutation in their daf-2 gene experienced a >2-fold extension in lifespan compared to wild-type. Inhibition of this pathway in vertebrate models has also been shown to extend lifespan, but to a lesser degree and in a more inconsistent manner. Female 129/SvPas mice heterozygous for the IGF-1 receptor null allele (Igf1r+/−) have been shown to live significantly longer (33%) than wild-type females, while male mutant mice demonstrated no such lifespan enhancing benefits (Holzenberger et al., 2003). Subsequent work has demonstrated that these benefits are strain dependent, as female C57BL/6J Igf1r+/− mice experienced a more modest (albeit significant) increase in lifespan compared to wild-type controls (Xu et al., 2014). In contrast, both male and female fat-specific insulin receptor knockout (FIRKO) mice showed a significant increase in lifespan (Bluher et al., 2003), possibly indicating that insulin signaling is more relevant to longevity than IGF-1 signaling. Alternatively, perhaps these differences between C. elegans and mice can be attributed to the fact that daf-2 encodes for a receptor that shows significant homology to both the IGF-1 receptor and the insulin receptor (Kimura et al., 1997), suggesting that dual knockout (or knockdown) of these receptors is necessary to achieve enhanced lifespan extension. In support of this supposition is the finding that both male and female mice that are null for the insulin receptor substrate protein 1 (Irs1) experienced significant extensions in lifespan (Selman et al., 2011). Irs1 is an adaptor protein that mediates the actions of both insulin and IGF-1.

Effects of IIS on Autophagy

The C. elegans daf-2 mutants exhibit a pronounced increase in autophagic activity compared to wild-type worms, indicating that the IIS pathway suppresses autophagy (Hansen et al., 2008). Indeed, activation of the IIS pathway is known to inhibit autophagy via the activation of mTORC1 and inhibition of FoxO signaling. FoxO proteins are transcription factors whose translocation to the nucleus is blocked via phosphorylation of Akt, which is a key kinase in the IIS pathway (Sandri et al., 2004). Under conditions of nutrient deprivation (and suppressed IIS), FoxO3 upregulates autophagy by promoting the expression of autophagy-related genes, including LC3, Bnip3, and Beclin1 (Mammucari et al., 2007; Zhao et al., 2007).

Effects of Age on IIS

As people age they enter a stage known as somatopause, during which they experience a decline in circulating growth hormone (GH) and IGF-1 levels (Junnila et al., 2013). Somatopause has also been detected in other mammals (Bartke, 2008). Paradoxically, centenarians have been shown to have significantly lower levels of circulating IGF-1 (Bonafe et al., 2003). Additionally, the offspring of centenarians have been shown to have both lower levels of circulating IGF-1 and lower IGF-1 activity compared to controls whose parents both died relatively young (Vitale et al., 2012). Perhaps the potential negative effects of lower GH/IGF-1 levels (e.g., lower levels of anabolism) are offset by a less pronounced decline in systemic autophagic activity. In support of this idea, healthy centenarians have been shown to have significantly higher levels of circulating beclin-1 compared to both young patients who have experienced an acute myocardial infarction and healthy young controls (Emanuele et al., 2014). This observation has been independently confirmed in a recent study that also showed a general increase in the expression of genes in the autophagy-lysosomal pathway in centenarians (Xiao et al., 2018).

Unlike IGF-1, circulating insulin levels generally increase with age. Aging is associated with hyperinsulinemia and insulin resistance that are caused by greater secretion of insulin in response to the same stimulus compared to younger individuals (Gumbiner et al., 1989). In contrast, centenarians have been shown to exhibit both a lower degree of insulin resistance and preserved β-cell function (Paolisso et al., 2001). Additionally, increased insulin sensitivity and lower mean fasting insulin levels have been observed in the offspring of nonagenarians compared to their partners (Rozing et al., 2010). A causal relationship between higher circulating insulin levels and decreased hepatic autophagy has been demonstrated in mice (Liu et al., 2009).

In summary, aging is associated with decreasing levels of autophagic activity that are partially the result of dysregulated IIS. Healthy centenarians, who do not experience the typical effects of normal aging, display both enhanced autophagy and better-preserved and regulated IIS.

Effects of Exercise on IIS

There is strong evidence to suggest that exercise promotes both healthspan and lifespan in worms (Chuang et al., 2016), flies (Piazza et al., 2009), and mammals (Cartee et al., 2016). In association, there is extensive evidence that indicates that exercise effectively suppresses insulin resistance and hyperinsulinemia (Ryan, 2000). Various population studies have shown inverse associations between physical activity and the incidence of type 2 diabetes mellitus, and both regular aerobic and resistance exercise have been recommended by the American Diabetes Association, especially for patients with type 2 diabetes (Colberg et al., 2016). Vigorous endurance exercise has been shown to decrease plasma insulin concentration and increase insulin sensitivity in subjects in their 60 s (Kirwan et al., 1993). A recent study has shown that a more gentle exercise regimen involving 20 min of resistance band exercise and 30 min of walking three times a week for 12 weeks is sufficient to improve insulin resistance in elderly women aged 70–80 years (Ha and Son, 2018). Mechanistically, one of the ways in which exercise is thought to increase insulin sensitivity is via contraction-stimulated glucose uptake, which involves the activation of AMPK. Importantly, exercise has also been shown to promote systemic autophagy (He et al., 2012). Perhaps acute exercise counteracts the autophagy-suppressing effects of IIS via the activation of autophagy promoters (such as AMPK), and regular exercise maintains long-term autophagic activity via preservation of insulin sensitivity and the consequent reduction in circulating insulin levels. Finally, the insulin sensitizing role of exercise-regulated myokines is discussed in a later section.

mTOR

mTOR and Longevity

As with the IIS pathway, inhibition of mTOR results in increased longevity. C. elegans deficient in TOR, like the previously-described daf-2 mutants, also displayed a doubling in lifespan (Vellai et al., 2003). Suppression of mTOR to ~25% of wild-type levels in mice carrying two hypomorphic mTOR alleles has also been shown to significantly extend median lifespan in both male and female mice (Wu et al., 2013). However, these mice experience lifespan extension of only ~20%, which approximately mirrors the lifespan extension seen in mice with suppressed IIS, as previously noted.

Effects of mTOR on Autophagy

As in the case of the daf-2 mutants, inactivation of TOR signaling in C. elegans also resulted in increased levels of autophagy, and suppression of autophagy resulted in the reversal of these lifespan-increasing effects (Hansen et al., 2008). Mechanistically, mTOR (while in the mTORC1 complex) has been shown to inhibit autophagy in two ways—via direct phosphorylation and inhibition of the autophagy-initiating kinase Ulk1 (Kim et al., 2011), and by phosphorylating transcription factor EB (TFEB) to prevent it from entering the nucleus where it can promote the expression of various autophagy and lysosomal genes (Martina et al., 2012).

Effects of Age on mTOR

Full activation of mTORC1 requires both growth factors (such as insulin or IGF-1) and a supply of amino acids (such as leucine, methionine, and arginine) (Saxton and Sabatini, 2017). As discussed previously, aging is associated with hyperinsulinemia, suggesting that mTORC1 activity also increases with age. Additionally, recent work has shown that the methionine metabolite, homocysteine, can also activate mTORC1 (Khayati et al., 2017). Homocysteine has been shown by various groups to accumulate with age (Selhub, 1999; Tucker et al., 2005; Smith and Refsum, 2016; Antikainen et al., 2017), also indicating a positive correlation between aging and mTORC1 activity. Increased mTORC1 activity would therefore serve as another reason for the general decline in autophagic activity seen with age.

Effects of Exercise on mTOR

Exercise has been shown to inhibit the mTORC1 pathway by reversing the phosphorylation of TFEB (Medina et al., 2015). It does so by promoting the release of Ca2+ from lysosomes via MCOLN1 resulting in local activation of calcineurin, which in turn dephosphorylates TFEB to promote its entry into the nucleus where it binds to and activates the promoters of various autophagic and lysosomal genes. Therefore, perhaps some of the lifespan-extending effects of exercise can be attributed to its effect on TFEB nuclear localization.

AMPK

AMPK and Longevity

A positive correlation between AMPK activity and longevity has been demonstrated in both invertebrate and vertebrate models. C. elegans worms that lack AMPK experienced a 12% reduction in lifespan compared to wild-type worms, whereas, AMPK overexpression resulted in a 13% increase in lifespan (Apfeld et al., 2004). Female mice chronically treated with Metformin, an anti-diabetic drug that activates AMPK, experienced maximum lifespan increase of ~10% compared to control mice (Anisimov et al., 2008).

Effects of AMPK on Autophagy

AMPK is a potent promoter of autophagy. Under conditions of stress, AMPK has been shown to promote autophagy via phosphorylation and subsequent stabilization of the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p27Kip1 (Liang et al., 2007). During glucose starvation, AMPK promotes autophagy by phosphorylating and activating the autophagy-initiating kinase Ulk1 (Kim et al., 2011). AMPK also promotes autophagy by directly and indirectly inhibiting mTORC1. AMPK directly phosphorylates raptor (which is a member of the mTORC1 complex) resulting in a suppression of mTORC1 kinase activity (Gwinn et al., 2008). AMPK indirectly suppresses mTORC1 by phosphorylating tuberous sclerosis complex 2 (TSC2) which enhances its GAP activity (Inoki et al., 2003).

Effects of Age on AMPK

Aging has a potent inhibitory effect on AMPK activity. Although baseline AMPK activity was comparable between young and old rats, old rats displayed a severely compromised ability to respond to activators of AMPK. Acute stimulation of AMPK via either administration of the AMPK activator AICAR or exercise was severely blunted in skeletal muscle of old rats compared to young (Reznick et al., 2007).

Effects of Exercise on AMPK

Various studies have demonstrated the ability of exercise to promote AMPK activation (Kjobsted et al., 2018). One of the ways in which it does so is by increasing the intracellular ratios of AMP:ATP and ADP:ATP (Gowans and Hardie, 2014). However, it should be noted that exercise has been shown to be unable to activate AMPK in aged tissue (Reznick et al., 2007). Therefore, perhaps in order for exercise to have an effect on autophagy via this pathway, it must be initiated early in life. Additionally, Reznick et al. subjected their rats to only 5 days of treadmill exercise. Perhaps a longer term exercise regimen would be able to overcome this inability to activate AMPK.

Sirtuins

Sirtuins and Longevity

Sirtuins are NAD+-dependent protein deacetylases whose increased activity has been linked to lifespan extension in both invertebrates and vertebrates. Increased gene dosage of sir-2.1 in C. elegans resulted in up to a 50% increase in lifespan (Tissenbaum and Guarente, 2001). Brain-specific overexpression of the mammalian ortholog of Sirt2—Sirt1—resulted in a significant increase in median lifespan (~16% for female mice, and ~9% for male mice) compared to wild-type controls (Satoh et al., 2013).

Effects of Sirtuins on Autophagy

Sirt1 has been shown to play a role in the regulation of autophagy via direct interaction with participants in the autophagic pathway, including Atg5, Atg7, and Atg8 (Lee et al., 2008). Sirt1−/− fibroblasts show suppressed autophagy in the context of starvation and a marked elevation of acetylation of key autophagy proteins. Therefore, Sirt1 promotes autophagy via the deacetylation of proteins involved in the autophagy pathway.

Effects of Age on Sirtuins

A general decline in sirtuin function with age has been observed. Reduced Sirt1 activity has been observed in the liver, heart, kidney, and lung of aged rats compared to young controls (Braidy et al., 2011). This decline in activity has been attributed to lower levels of NAD+. Similarly, a decrease in Sirt1 expression has been detected in the arteries of both mice and humans (Donato et al., 2011).

Effects of Exercise on Sirtuins

Exercise has been shown to be a potent activator of sirtuins. Old rats subjected to an 8-week long regimen of treadmill exercise experienced a significant increase in Sirt1 deacetylase activity compared to both young and sedentary old rats (Ferrara et al., 2008). Similarly, both old and young human subjects experienced a significant increase in skeletal muscle Sirt1 expression after just one bout of intense treadmill exercise (Bori et al., 2012).

Does Exercise Regulate Autophagy via the Regulation of Myokine Secretion?

There is emerging evidence that skeletal muscle can regulate both systemic physiology and aging via the release of so-called “myokines” (Demontis et al., 2013). As mentioned before, exercise has the effect of promoting insulin sensitivity, and there is evidence to suggest that this effect is partially mediated by the regulation of myokine secretion. One of the most extensively studied myokines is myostatin, which belongs to the TGF-β superfamily of ligands and is a potent inhibitor of muscle mass. Myostatin has also been suggested to be a promoter of insulin resistance, and aerobic exercise has the effect of suppressing circulating levels of myostatin (Hittel et al., 2010). Conversely, exercise has been shown to promote the secretion of the myokines IL-6, IL-15, Irisin, Metrnl, and myonectin, all of which have been associated with improved insulin sensitivity (Ellingsgaard et al., 2011; Barra et al., 2012; Bostrom et al., 2012; Rao et al., 2014; Gizaw et al., 2017; Jung et al., 2018; Pourranjbar et al., 2018). Myokines Metrnl (Jung et al., 2018), Irisin (Li et al., 2018, 2019), and IL-15 (Nadeau et al., 2019) activate AMPK in skeletal muscle and cardiac tissue suggesting a possible mechanism to induce autophagy throughout muscle and possibly non-muscle tissue. The role of myokines in exercise-induced autophagy has not been extensively studied. Given the emerging importance of myokines in mediating the insulin sensitizing effects of exercise, we propose that this possible role is worthy of further examination.

Pharmacological Agents, Exercise, or Diet?

Various drug candidates have been identified that can modulate each of the above pathways described. These autophagy-promoting pharmacological agents have been discussed elsewhere (Vakifahmetoglu-Norberg et al., 2015). While these agents have shown varying success in preclinical settings, certain caveats associated with them must be noted, including that they typically target just one protein or pathway, and their potentially negative side-effects have not been thoroughly examined, particularly in the setting of human biology. Alternatively, non-pharmacological approaches such as exercise and dietary interventions (such as calorie restriction) have been shown to be potent autophagy activators that effectively target all of the previously described longevity pathways. Additionally, exercise (especially moderate exercise) has few, if any, adverse side effects.

Among the best-studied autophagy promoting agents are Metformin, Rapamycin, and Resveratrol. Metformin is a drug that is used to treat type 2 diabetes. It has been shown to promote autophagy via activation of both AMPK and Sirt1 (Zhou et al., 2001; Song et al., 2015), however it is also known to have various off-target effects such as inhibition of respiratory complex I. Similarly, Resveratrol has also been shown to activate AMPK and Sirt1 (Borra et al., 2005; Vingtdeux et al., 2010). However, trials in clinical settings have produced murky and sometimes contradictory findings, as described in Bitterman and Chung (2015). Rapamycin indirectly activates autophagy by inhibiting mTORC1. It is currently being tested in clinical trials as a therapy for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT03359538). Although a potent promoter of autophagy, Rapamycin treatment is associated with various negative side-effects, including immunosuppression and the potential induction of insulin resistance via off-target inhibition of mTORC2 (Saxton and Sabatini, 2017).

In summary, although these and various other drugs have been shown to positively modulate autophagy and even have life-extending effects (Howitz et al., 2003; Harrison et al., 2009) in animal models, there are many concerns about their potential translation to a human setting.

Calorie restriction (CR) is another intervention that has also been shown to promote longevity and beneficially modulate the previously described longevity pathways (Kenyon, 2010). Although CR holds much promise as a promoter of healthspan and lifespan, there are limited long-term studies on the effects of CR in humans. Additionally, it is not an advisable intervention for subjects wanting to maintain lean mass, such as patients with cancer-associated cachexia and elderly individuals with symptoms of sarcopenia (Galluzzi et al., 2017). Finally, life-long adherence to a CR diet, notwithstanding its potentially life-extending effects, is unlikely to be an attractive option for most people. However, in light of the therapeutic promise that CR holds, it is worth exploring alternative and more feasible ways in which it could be exploited. To that end, time-restricted feeding, which entails food consumption within a certain time window and is seen as a more easily adoptable alternative to CR, has been shown to impede the development of high fat-induced metabolic disorders such as obesity, dyslipidemia, and glucose intolerance (Chaix et al., 2019). Finally, recent studies have revealed an additive effect of exercise and CR in promoting mitochondrial health and increasing insulin sensitivity (Sharma et al., 2015; Kitaoka et al., 2016).

Future Directions

An important future research direction is a thorough assessment of the relative contribution of each of the pathways discussed in this review to autophagy regulation in individual organs and tissue systems. Significant effort has been made to show that organ-specific blockade of autophagy has deleterious effects, including skeletal muscle (Carnio et al., 2014), brain (Komatsu et al., 2007), and liver (Inami et al., 2011). However, few studies have evaluated the effects of this organ-specific inhibition on lifespan. Finally, it would be of equal importance to determine the effects of organ-specific induction of autophagy on organismal health and longevity.

Conclusion

In summary, autophagy has convincingly been shown to play a pivotal role in healthspan and lifespan extension. In this review, we have discussed various cell signaling pathways whose modulation has been shown to have beneficial effects on longevity, and how autophagy is a necessary mediator of these effects. We have also presented current pharmaceutical therapies, exercise and dietary restriction as effective ways to modulate many of these pathways to increase or preserve autophagic activity, thereby acting as a potent geroprotector.

Author Contributions

JW, AB, and DL wrote the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

JW was supported by NIH/NIA grant K01AG056664, Borden Scholar Award through Duke University and the Pepper Center grant P30 AG028716. DL was supported by NIH/NHLBI training grant T32HL007057.

References

Anisimov, V. N., Berstein, L. M., Egormin, P. A., Piskunova, T. S., Popovich, I. G., Zabezhinski, M. A., et al. (2008). Metformin slows down aging and extends life span of female SHR mice. Cell Cycle 7, 2769–2773. doi: 10.4161/cc.7.17.6625

Antikainen, H., Driscoll, M., Haspel, G., and Dobrowolski, R. (2017). TOR-mediated regulation of metabolism in aging. Aging Cell 16, 1219–1233. doi: 10.1111/acel.12689

Apfeld, J., O'Connor, G., McDonagh, T., DiStefano, P. S., and Curtis, R. (2004). The AMP-activated protein kinase AAK-2 links energy levels and insulin-like signals to lifespan in C. elegans. Genes Dev. 18, 3004–3009. doi: 10.1101/gad.1255404

Barra, N. G., Chew, M. V., Holloway, A. C., and Ashkar, A. A. (2012). Interleukin-15 treatment improves glucose homeostasis and insulin sensitivity in obese mice. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 14, 190–193. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1326.2011.01495.x

Bartke, A. (2008). Growth hormone and aging: a challenging controversy. Clin. Interv. Aging 3, 659–665. doi: 10.2147/CIA.S3697

Bitterman, J. L., and Chung, J. H. (2015). Metabolic effects of resveratrol: addressing the controversies. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 72, 1473–1488. doi: 10.1007/s00018-014-1808-8

Bluher, M., Kahn, B. B., and Kahn, C. R. (2003). Extended longevity in mice lacking the insulin receptor in adipose tissue. Science 299, 572–574. doi: 10.1126/science.1078223

Bonafe, M., Barbieri, M., Marchegiani, F., Olivieri, F., Ragno, E., Giampieri, C., et al. (2003). Polymorphic variants of insulin-like growth factor I (IGF-I) receptor and phosphoinositide 3-kinase genes affect IGF-I plasma levels and human longevity: cues for an evolutionarily conserved mechanism of life span control. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 88, 3299–3304. doi: 10.1210/jc.2002-021810

Bori, Z., Zhao, Z., Koltai, E., Fatouros, I. G., Jamurtas, A. Z., Douroudos, I. I., et al. (2012). The effects of aging, physical training, and a single bout of exercise on mitochondrial protein expression in human skeletal muscle. Exp. Gerontol. 47, 417–424. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2012.03.004

Borra, M. T., Smith, B. C., and Denu, J. M. (2005). Mechanism of human SIRT1 activation by resveratrol. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 17187–17195. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M501250200

Bostrom, P., Wu, J., Jedrychowski, M. P., Korde, A., Ye, L., Lo, J. C., et al. (2012). A PGC1-α-dependent myokine that drives brown-fat-like development of white fat and thermogenesis. Nature 481, 463–468. doi: 10.1038/nature10777

Boya, P., Codogno, P., and Rodriguez-Muela, N. (2018). Autophagy in stem cells: repair, remodelling and metabolic reprogramming. Development 145:dev146506. doi: 10.1242/dev.146506

Braidy, N., Guillemin, G. J., Mansour, H., Chan-Ling, T., Poljak, A., and Grant, R. (2011). Age related changes in NAD+ metabolism oxidative stress and Sirt1 activity in wistar rats. PLoS ONE 6:e19194. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0019194

Carnio, S., LoVerso, F., Baraibar, M. A., Longa, E., Khan, M. M., Maffei, M., et al. (2014). Autophagy impairment in muscle induces neuromuscular junction degeneration and precocious aging. Cell Rep. 8, 1509–1521. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.07.061

Cartee, G. D., Hepple, R. T., Bamman, M. M., and Zierath, J. R. (2016). Exercise promotes healthy aging of skeletal muscle. Cell Metab. 23, 1034–1047. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2016.05.007

Chaix, A., Lin, T., Le, H. D., Chang, M. W., and Panda, S. (2019). Time-restricted feeding prevents obesity and metabolic syndrome in mice lacking a circadian clock. Cell Metab. 29, 303–319.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2018.08.004

Chang, J. T., Kumsta, C., Hellman, A. B., Adams, L. M., and Hansen, M. (2017). Spatiotemporal regulation of autophagy during Caenorhabditis elegans aging. Elife 6:e18459. doi: 10.7554/eLife.18459

Chuang, H. S., Kuo, W. J., Lee, C. L., Chu, I. H., and Chen, C. S. (2016). Exercise in an electrotactic flow chamber ameliorates age-related degeneration in Caenorhabditis elegans. Sci. Rep. 6:28064. doi: 10.1038/srep28064

Colberg, S. R., Sigal, R. J., Yardley, J. E., Riddell, M. C., Dunstan, D. W., Dempsey, P. C., et al. (2016). Physical activity/exercise and diabetes: a position statement of the american diabetes association. Diabetes Care 39, 2065–2079. doi: 10.2337/dc16-1728

Cuervo, A. M., and Macian, F. (2014). Autophagy and the immune function in aging. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 29, 97–104. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2014.05.006

Dagon, Y., Mantzoros, C., and Kim, Y. B. (2015). Exercising insulin sensitivity: AMPK turns on autophagy! Metab. Clin. Exp. 64, 655–657. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2015.03.002

Demontis, F., Piccirillo, R., Goldberg, A. L., and Perrimon, N. (2013). The influence of skeletal muscle on systemic aging and lifespan. Aging Cell 12, 943–949. doi: 10.1111/acel.12126

Donato, A. J., Magerko, K. A., Lawson, B. R., Durrant, J. R., Lesniewski, L. A., and Seals, D. R. (2011). SIRT-1 and vascular endothelial dysfunction with ageing in mice and humans. J. Physiol. 589, 4545–4554. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2011.211219

Ellingsgaard, H., Hauselmann, I., Schuler, B., Habib, A. M., Baggio, L. L., Meier, D. T., et al. (2011). Interleukin-6 enhances insulin secretion by increasing glucagon-like peptide-1 secretion from L cells and alpha cells. Nat. Med. 17, 1481–1489. doi: 10.1038/nm.2513

Emanuele, E., Minoretti, P., Sanchis-Gomar, F., Pareja-Galeano, H., Yilmaz, Y., Garatachea, N., et al. (2014). Can enhanced autophagy be associated with human longevity? Serum levels of the autophagy biomarker beclin-1 are increased in healthy centenarians. Rejuvenation Res. 17, 518–524. doi: 10.1089/rej.2014.1607

Fernandez, A. F., Sebti, S., Wei, Y., Zou, Z., Shi, M., McMillan, K. L., et al. (2018). Disruption of the beclin 1-BCL2 autophagy regulatory complex promotes longevity in mice. Nature 558, 136–140. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0162-7

Ferrara, N., Rinaldi, B., Corbi, G., Conti, V., Stiuso, P., Boccuti, S., et al. (2008). Exercise training promotes SIRT1 activity in aged rats. Rejuvenation Res. 11, 139–150. doi: 10.1089/rej.2007.0576

Galluzzi, L., Bravo-San Pedro, J. M., Levine, B., Green, D. R., and Kroemer, G. (2017). Pharmacological modulation of autophagy: therapeutic potential and persisting obstacles. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 16, 487–511. doi: 10.1038/nrd.2017.22

Gizaw, M., Anandakumar, P., and Debela, T. (2017). A review on the role of irisin in insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes mellitus. J. Pharmacopuncture 20, 235–242. doi: 10.3831/KPI.2017.20.029

Gowans, G. J., and Hardie, D. G. (2014). AMPK: a cellular energy sensor primarily regulated by AMP. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 42, 71–75. doi: 10.1042/BST20130244

Gumbiner, B., Polonsky, K. S., Beltz, W. F., Wallace, P., Brechtel, G., and Fink, R. I. (1989). Effects of aging on insulin secretion. Diabetes 38, 1549–1556. doi: 10.2337/diab.38.12.1549

Gwinn, D. M., Shackelford, D. B., Egan, D. F., Mihaylova, M. M., Mery, A., Vasquez, D. S., et al. (2008). AMPK phosphorylation of raptor mediates a metabolic checkpoint. Mol. Cell 30, 214–226. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.03.003

Ha, M. S., and Son, W. M. (2018). Combined exercise is a modality for improving insulin resistance and aging-related hormone biomarkers in elderly Korean women. Exp. Gerontol. 114, 13–18. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2018.10.012

Hansen, M., Chandra, A., Mitic, L. L., Onken, B., Driscoll, M., and Kenyon, C. (2008). A role for autophagy in the extension of lifespan by dietary restriction in C. elegans. PLoS Genet. 4:e24. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0040024

Harrison, D. E., Strong, R., Sharp, Z. D., Nelson, J. F., Astle, C. M., Flurkey, K., et al. (2009). Rapamycin fed late in life extends lifespan in genetically heterogeneous mice. Nature 460, 392–395. doi: 10.1038/nature08221

He, C., Sumpter, R., and Levine, B. (2012). Exercise induces autophagy in peripheral tissues and in the brain. Autophagy 8, 1548–1551. doi: 10.4161/auto.21327

Hittel, D. S., Axelson, M., Sarna, N., Shearer, J., Huffman, K. M., and Kraus, W. E. (2010). Myostatin decreases with aerobic exercise and associates with insulin resistance. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 42, 2023–2029. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181e0b9a8

Holzenberger, M., Dupont, J., Ducos, B., Leneuve, P., Geloen, A., Even, P. C., et al. (2003). IGF-1 receptor regulates lifespan and resistance to oxidative stress in mice. Nature 421, 182–187. doi: 10.1038/nature01298

Howitz, K. T., Bitterman, K. J., Cohen, H. Y., Lamming, D. W., Lavu, S., Wood, J. G., et al. (2003). Small molecule activators of sirtuins extend Saccharomyces cerevisiae lifespan. Nature 425, 191–196. doi: 10.1038/nature01960

Inami, Y., Waguri, S., Sakamoto, A., Kouno, T., Nakada, K., Hino, O., et al. (2011). Persistent activation of Nrf2 through p62 in hepatocellular carcinoma cells. J. Cell Biol. 193, 275–284. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201102031

Inoki, K., Zhu, T., and Guan, K. L. (2003). TSC2 mediates cellular energy response to control cell growth and survival. Cell 115, 577–590. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(03)00929-2

Jung, T. W., Lee, S. H., Kim, H. C., Bang, J. S., Abd El-Aty, A. M., Hacimuftuoglu, A., et al. (2018). METRNL attenuates lipid-induced inflammation and insulin resistance via AMPK or PPARδ-dependent pathways in skeletal muscle of mice. Exp. Mol. Med. 50:122. doi: 10.1038/s12276-018-0147-5

Junnila, R. K., List, E. O., Berryman, D. E., Murrey, J. W., and Kopchick, J. J. (2013). The GH/IGF-1 axis in ageing and longevity. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 9, 366–376. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2013.67

Kenyon, C., Chang, J., Gensch, E., Rudner, A., and Tabtiang, R. (1993). A C. elegans mutant that lives twice as long as wild type. Nature 366, 461–464. doi: 10.1038/366461a0

Kern, A., and Behl, C. (2019). Special issue on “proteostasis and autophagy.” Cells 8:E642. doi: 10.3390/cells8070642

Khayati, K., Antikainen, H., Bonder, E. M., Weber, G. F., Kruger, W. D., Jakubowski, H., et al. (2017). The amino acid metabolite homocysteine activates mTORC1 to inhibit autophagy and form abnormal proteins in human neurons and mice. FASEB J. 31, 598–609. doi: 10.1096/fj.201600915R

Kim, J., Kundu, M., Viollet, B., and Guan, K. L. (2011). AMPK and mTOR regulate autophagy through direct phosphorylation of Ulk1. Nat. Cell Biol. 13, 132–141. doi: 10.1038/ncb2152

Kimura, K. D., Tissenbaum, H. A., Liu, Y., and Ruvkun, G. (1997). daf-2, an insulin receptor-like gene that regulates longevity and diapause in Caenorhabditis elegans. Science 277, 942–946. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5328.942

Kirwan, J. P., Kohrt, W. M., Wojta, D. M., Bourey, R. E., and Holloszy, J. O. (1993). Endurance exercise training reduces glucose-stimulated insulin levels in 60- to 70-year-old men and women. J. Gerontol. 48, M84–90. doi: 10.1093/geronj/48.3.M84

Kitaoka, Y., Nakazato, K., and Ogasawara, R. (2016). Combined effects of resistance training and calorie restriction on mitochondrial fusion and fission proteins in rat skeletal muscle. J. Appl. Physiol. 121, 806–810. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00465.2016

Kjobsted, R., Hingst, J. R., Fentz, J., Foretz, M., Sanz, M. N., Pehmoller, C., et al. (2018). AMPK in skeletal muscle function and metabolism. FASEB J. 32, 1741–1777. doi: 10.1096/fj.201700442R

Komatsu, M., Wang, Q. J., Holstein, G. R., Friedrich, V. L., Iwata, J., Kominami, E., et al. (2007). Essential role for autophagy protein Atg7 in the maintenance of axonal homeostasis and the prevention of axonal degeneration. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 14489–14494. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0701311104

Lee, I. H., Cao, L., Mostoslavsky, R., Lombard, D. B., Liu, J., Bruns, N. E., et al. (2008). A role for the NAD-dependent deacetylase Sirt1 in the regulation of autophagy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 3374–3379. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0712145105

Li, R., Wang, X., Wu, S., Wu, Y., Chen, H., Xin, J., et al. (2019). Irisin ameliorates angiotensin II-induced cardiomyocyte apoptosis through autophagy. J. Cell Physiol. 234, 17578–17588. doi: 10.1002/jcp.28382

Li, R. L., Wu, S. S., Wu, Y., Wang, X. X., Chen, H. Y., Xin, J. J., et al. (2018). Irisin alleviates pressure overload-induced cardiac hypertrophy by inducing protective autophagy via mTOR-independent activation of the AMPK-ULK1 pathway. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 121, 242–255. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2018.07.250

Liang, J., Shao, S. H., Xu, Z. X., Hennessy, B., Ding, Z., Larrea, M., et al. (2007). The energy sensing LKB1-AMPK pathway regulates p27(kip1) phosphorylation mediating the decision to enter autophagy or apoptosis. Nat. Cell Biol. 9, 218–224. doi: 10.1038/ncb1537

Liu, H. Y., Han, J., Cao, S. Y., Hong, T., Zhuo, D., Shi, J., et al. (2009). Hepatic autophagy is suppressed in the presence of insulin resistance and hyperinsulinemia: inhibition of FoxO1-dependent expression of key autophagy genes by insulin. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 31484–31492. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.033936

Lopez-Otin, C., Blasco, M. A., Partridge, L., Serrano, M., and Kroemer, G. (2013). The hallmarks of aging. Cell 153, 1194–1217. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.05.039

Mammucari, C., Milan, G., Romanello, V., Masiero, E., Rudolf, R., Del Piccolo, P., et al. (2007). FoxO3 controls autophagy in skeletal muscle in vivo. Cell Metab. 6, 458–471. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2007.11.001

Martina, J. A., Chen, Y., Gucek, M., and Puertollano, R. (2012). MTORC1 functions as a transcriptional regulator of autophagy by preventing nuclear transport of TFEB. Autophagy 8, 903–914. doi: 10.4161/auto.19653

Medina, D. L., Di Paola, S., Peluso, I., Armani, A., De Stefani, D., Venditti, R., et al. (2015). Lysosomal calcium signalling regulates autophagy through calcineurin and TFEB. Nat. Cell Biol. 17, 288–299. doi: 10.1038/ncb3114

Melendez, A., Talloczy, Z., Seaman, M., Eskelinen, E. L., Hall, D. H., and Levine, B. (2003). Autophagy genes are essential for dauer development and life-span extension in C. elegans. Science 301, 1387–1391. doi: 10.1126/science.1087782

Nadeau, L., Patten, D. A., Caron, A., Garneau, L., Pinault-Masson, E., Foretz, M., et al. (2019). IL-15 improves skeletal muscle oxidative metabolism and glucose uptake in association with increased respiratory chain supercomplex formation and AMPK pathway activation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Gen. Subj. 1863, 395–407. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2018.10.021

Nassour, J., Radford, R., Correia, A., Fuste, J. M., Schoell, B., Jauch, A., et al. (2019). Autophagic cell death restricts chromosomal instability during replicative crisis. Nature 565, 659–663. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-0885-0

Palikaras, K., Lionaki, E., and Tavernarakis, N. (2018). Mechanisms of mitophagy in cellular homeostasis, physiology and pathology. Nat. Cell Biol. 20, 1013–1022. doi: 10.1038/s41556-018-0176-2

Paolisso, G., Barbieri, M., Rizzo, M. R., Carella, C., Rotondi, M., Bonafe, M., et al. (2001). Low insulin resistance and preserved beta-cell function contribute to human longevity but are not associated with TH-INS genes. Exp. Gerontol. 37, 149–156. doi: 10.1016/S0531-5565(01)00148-6

Piazza, N., Gosangi, B., Devilla, S., Arking, R., and Wessells, R. (2009). Exercise-training in young Drosophila melanogaster reduces age-related decline in mobility and cardiac performance. PLoS ONE 4:e5886. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005886

Pourranjbar, M., Arabnejad, N., Naderipour, K., and Rafie, F. (2018). Effects of aerobic exercises on serum levels of myonectin and insulin resistance in obese and overweight women. J. Med. Life 11, 381–386. doi: 10.25122/jml-2018-0033

Pyo, J. O., Yoo, S. M., Ahn, H. H., Nah, J., Hong, S. H., Kam, T. I., et al. (2013). Overexpression of Atg5 in mice activates autophagy and extends lifespan. Nat. Commun. 4:2300. doi: 10.1038/ncomms3300

Rao, R. R., Long, J. Z., White, J. P., Svensson, K. J., Lou, J., Lokurkar, I., et al. (2014). Meteorin-like is a hormone that regulates immune-adipose interactions to increase beige fat thermogenesis. Cell 157, 1279–1291. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.03.065

Reznick, R. M., Zong, H., Li, J., Morino, K., Moore, I. K., Yu, H. J., et al. (2007). Aging-associated reductions in AMP-activated protein kinase activity and mitochondrial biogenesis. Cell Metab. 5, 151–156. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2007.01.008

Rozing, M. P., Westendorp, R. G., de Craen, A. J., Frolich, M., de Goeij, M. C., Heijmans, B. T., et al. (2010). Favorable glucose tolerance and lower prevalence of metabolic syndrome in offspring without diabetes mellitus of nonagenarian siblings: the Leiden longevity study. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 58, 564–569. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.02725.x

Ryan, A. S. (2000). Insulin resistance with aging: effects of diet and exercise. Sports Med. 30, 327–346. doi: 10.2165/00007256-200030050-00002

Sandri, M., Sandri, C., Gilbert, A., Skurk, C., Calabria, E., Picard, A., et al. (2004). Foxo transcription factors induce the atrophy-related ubiquitin ligase atrogin-1 and cause skeletal muscle atrophy. Cell 117, 399–412. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(04)00400-3

Satoh, A., Brace, C. S., Rensing, N., Cliften, P., Wozniak, D. F., Herzog, E. D., et al. (2013). Sirt1 extends life span and delays aging in mice through the regulation of Nk2 homeobox 1 in the DMH and LH. Cell Metab. 18, 416–430. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2013.07.013

Saxton, R. A., and Sabatini, D. M. (2017). mTOR signaling in growth, metabolism, and disease. Cell 169, 361–371. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.03.035

Selhub, J. (1999). Homocysteine metabolism. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 19, 217–246. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nutr.19.1.217

Selman, C., Partridge, L., and Withers, D. J. (2011). Replication of extended lifespan phenotype in mice with deletion of insulin receptor substrate 1. PLoS ONE 6:e16144. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0016144

Sharma, N., Wang, H., Arias, E. B., Castorena, C. M., and Cartee, G. D. (2015). Mechanisms for independent and combined effects of calorie restriction and acute exercise on insulin-stimulated glucose uptake by skeletal muscle of old rats. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 308, E603–E612. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00618.2014

Simonsen, A., Cumming, R. C., Brech, A., Isakson, P., Schubert, D. R., and Finley, K. D. (2008). Promoting basal levels of autophagy in the nervous system enhances longevity and oxidant resistance in adult Drosophila. Autophagy 4, 176–184. doi: 10.4161/auto.5269

Smith, A. D., and Refsum, H. (2016). Homocysteine, B vitamins, and cognitive impairment. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 36, 211–239. doi: 10.1146/annurev-nutr-071715-050947

Song, Y. M., Lee, Y. H., Kim, J. W., Ham, D. S., Kang, E. S., Cha, B. S., et al. (2015). Metformin alleviates hepatosteatosis by restoring SIRT1-mediated autophagy induction via an AMP-activated protein kinase-independent pathway. Autophagy 11, 46–59. doi: 10.4161/15548627.2014.984271

Terman, A. (1995). The effect of age on formation and elimination of autophagic vacuoles in mouse hepatocytes. Gerontology 41(Suppl. 2), 319–326. doi: 10.1159/000213753

Tissenbaum, H. A., and Guarente, L. (2001). Increased dosage of a sir-2 gene extends lifespan in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature 410, 227–230. doi: 10.1038/35065638

Tucker, K. L., Qiao, N., Scott, T., Rosenberg, I., and Spiro, A. III. (2005). High homocysteine and low B vitamins predict cognitive decline in aging men: the Veterans Affairs Normative Aging Study. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 82, 627–635. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/82.3.627

Vakifahmetoglu-Norberg, H., Xia, H. G., and Yuan, J. (2015). Pharmacologic agents targeting autophagy. J. Clin. Invest. 125, 5–13. doi: 10.1172/JCI73937

Vellai, T., Takacs-Vellai, K., Zhang, Y., Kovacs, A. L., Orosz, L., and Muller, F. (2003). Genetics: influence of TOR kinase on lifespan in C. elegans. Nature 426, 620. doi: 10.1038/426620a

Vessoni, A. T., Filippi-Chiela, E. C., Menck, C. F., and Lenz, G. (2013). Autophagy and genomic integrity. Cell Death Differ. 20, 1444–1454. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2013.103

Vingtdeux, V., Giliberto, L., Zhao, H., Chandakkar, P., Wu, Q., Simon, J. E., et al. (2010). AMP-activated protein kinase signaling activation by resveratrol modulates amyloid-beta peptide metabolism. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 9100–9113. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.060061

Vitale, G., Brugts, M. P., Ogliari, G., Castaldi, D., Fatti, L. M., Varewijck, A. J., et al. (2012). Low circulating IGF-I bioactivity is associated with human longevity: findings in centenarians' offspring. Aging 4, 580–589. doi: 10.18632/aging.100484

Wu, J. J., Liu, J., Chen, E. B., Wang, J. J., Cao, L., Narayan, N., et al. (2013). Increased mammalian lifespan and a segmental and tissue-specific slowing of aging after genetic reduction of mTOR expression. Cell Rep. 4, 913–920. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2013.07.030

Xiao, F. H., Chen, X. Q., Yu, Q., Ye, Y., Liu, Y. W., Yan, D., et al. (2018). Transcriptome evidence reveals enhanced autophagy-lysosomal function in centenarians. Genome Res. 28, 1601–1610. doi: 10.1101/gr.220780.117

Xu, J., Gontier, G., Chaker, Z., Lacube, P., Dupont, J., and Holzenberger, M. (2014). Longevity effect of IGF-1R(+/-) mutation depends on genetic background-specific receptor activation. Aging Cell 13, 19–28. doi: 10.1111/acel.12145

Zhao, J., Brault, J. J., Schild, A., Cao, P., Sandri, M., Schiaffino, S., et al. (2007). FoxO3 coordinately activates protein degradation by the autophagic/lysosomal and proteasomal pathways in atrophying muscle cells. Cell Metab. 6, 472–483. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2007.11.004

Keywords: autophagy, longevity, aging, exercise, healthspan

Citation: Bareja A, Lee DE and White JP (2019) Maximizing Longevity and Healthspan: Multiple Approaches All Converging on Autophagy. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 7:183. doi: 10.3389/fcell.2019.00183

Received: 05 May 2019; Accepted: 20 August 2019;

Published: 06 September 2019.

Edited by:

Tassula Proikas-Cezanne, University of Tübingen, GermanyReviewed by:

Carsten Culmsee, University of Marburg, GermanyShaochun Yuan, Sun Yat-sen University, China

Copyright © 2019 Bareja, Lee and White. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: James P. White, amFtZXMud2hpdGUmI3gwMDA0MDtkbS5kdWtlLmVkdQ==

Akshay Bareja

Akshay Bareja David E. Lee

David E. Lee James P. White

James P. White