- 1School of Biological Sciences and Biotechnology, Institute of Advanced Research, Koba Institutional Area, Gandhinagar, India

- 2Department of R&D, Cementic S. A. S., Genopole, Paris, France

A Corrigendum on

Engineering Strategies in Microorganisms for the Enhanced Production of Squalene: Advances, Challenges and Opportunities

by Gohil, N., Bhattacharjee, G., Khambhati, K., Braddick, D., and Singh, V. (2019). Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 7:50. doi: 10.3389/fbioe.2019.00050

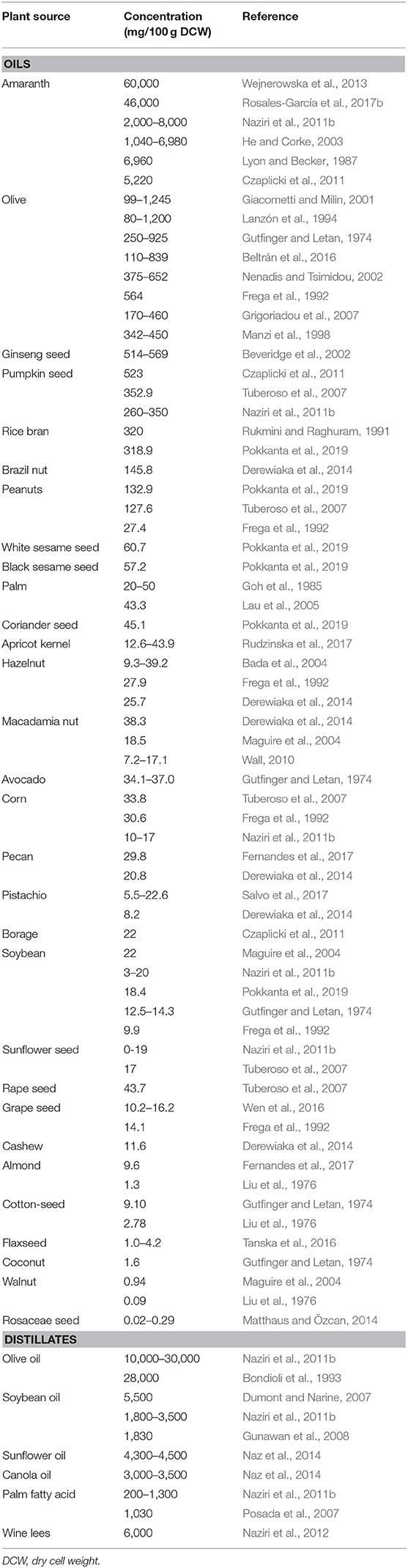

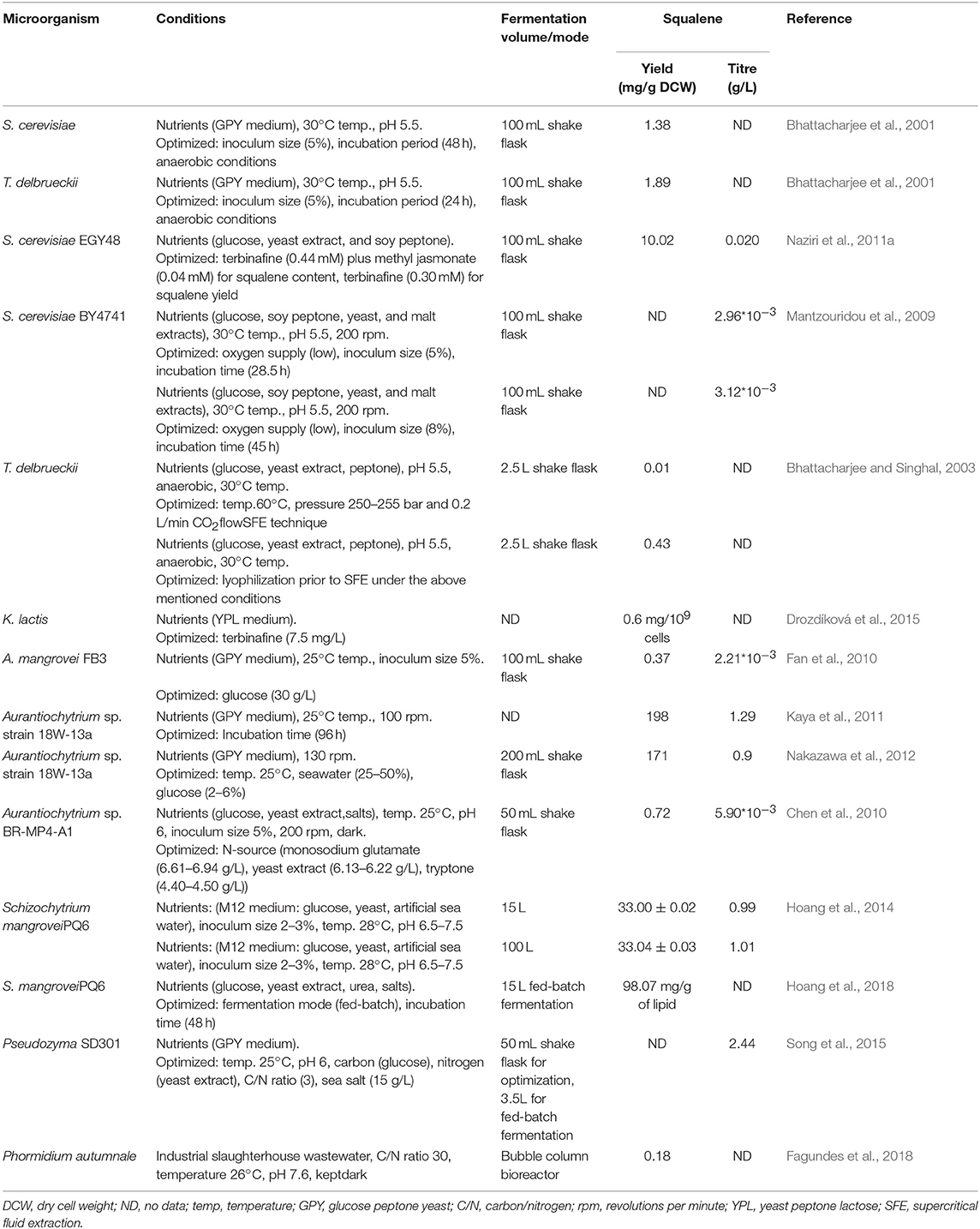

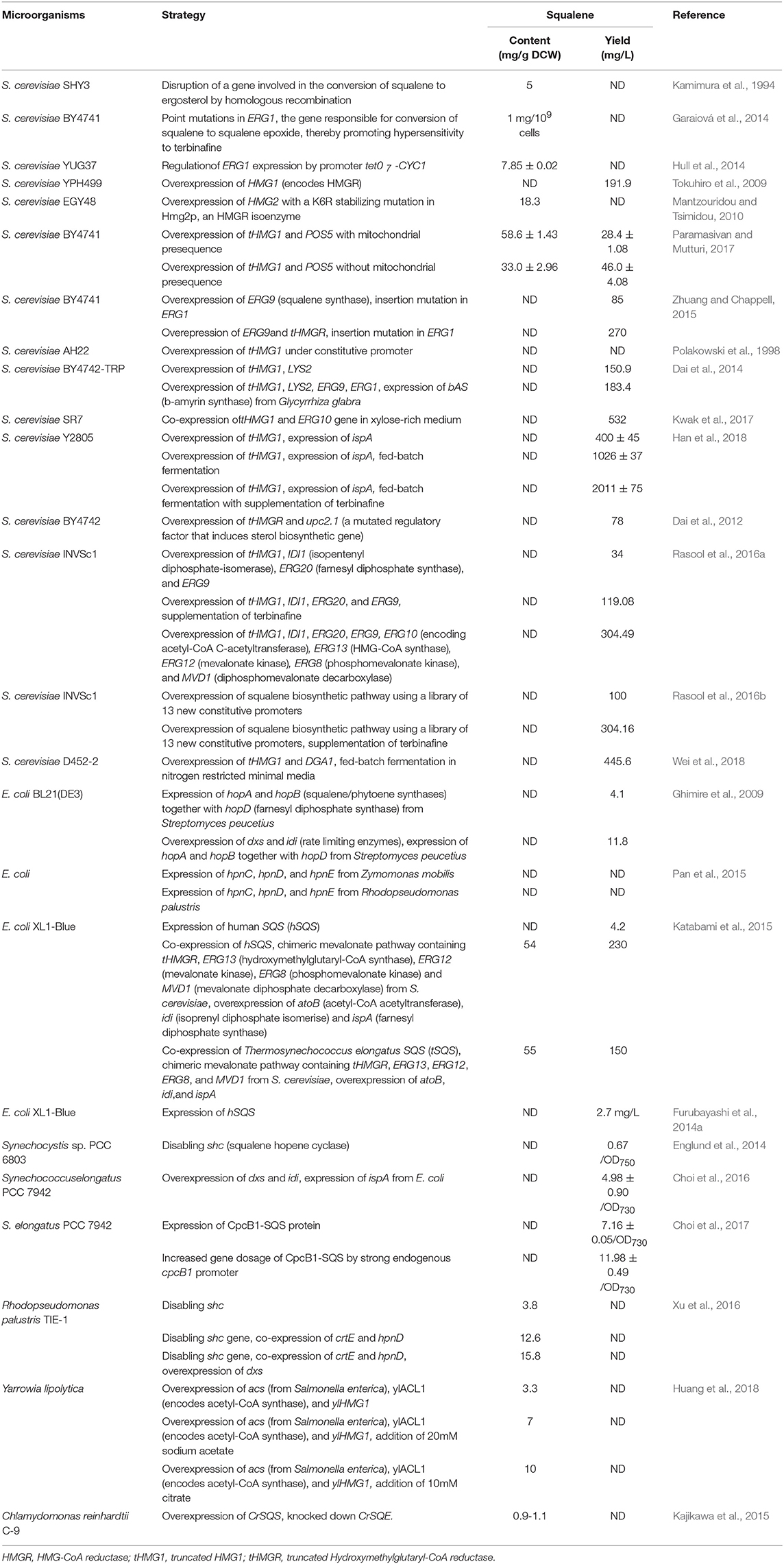

In the original article, there were mistakes in Tables 1, 3, and 4.

From Table 1, all squalene values associated with Ryan et al. (2006) work (brazil nut, pecan, pistachio, cashew, and pine nut) have been deleted as the authors consider the values in their original article to be impractical. Also, the concentration of squalene in rape seed and wine lees were mentioned as 17 and 60 mg/100 g DCW, respectively, which has been corrected. For rape seed it is 43.7 mg/100 g and for wine lees it is 6,000 mg/100 g.

In Table 3, some titer values (Mantzouridou et al., 2009; Chen et al., 2010; Fan et al., 2010) were mistakenly stated incorrectly following errors while converting units. In the case of Mantzouridou et al. (2009), the titers were incorrectly provided as “2.96*103 and 3.12*103 g/L” while they should be “2.96*10−3 and 3.12*10−3” g/L, respectively. As for Fan et al. (2010), the corrected titer value is “2.21*10−3” instead of “21.2 g/L.” Additionally, the biomass weight was earlier stated as “No Data (ND)” but it was later found to be “0.37 mg/g” dry cell weight (DCW) when the glucose concentration was 30 g/L. Lastly, for Chen et al. (2010), the titer was incorrectly provided as “5.90 g/L” while it is “5.90*10−3 g/L.” The work of Kaya et al. (2011) has been cited again in Table 3 (cited priorly in Table 2) pertaining to its fermentation parameter optimization.

As for Table 4, the squalene biomass and yield values under Paramasivan and Mutturi's work 2017 have been corrected. Upon correction, the squalene biomass and yield in presence and absence of mitochondrial presequence have been labeled separately. The squalene biomass with the mitochondrial sequence happens to be 58.6 ± 1.43 mg/g DCW, while the yield is 28.4 ± 1.08 mg/L. Squalene biomass and yield without the mitochondrial presequence is 33.0 ± 2.96 mg/g DCW and 46.0 ± 4.08 mg/L, respectively.

The corrected Tables 1, 3, and 4 appear below.

Additionally, there were errors in the text. Following the deletion of Ryan et al.'s work from Table 1, paragraph 2 under “Squalene From Plants” has been reformed as follows:

“Rice bran, a co-product of the rice milling process also contains a good amount (318.9–320 mg/100 g) of squalene (Rukmini and Raghuram, 1991; Pokkanta et al., 2019). Palm oil has just 20–50 mg/100 g of squalene (Goh et al., 1985; Lau et al., 2005) but because of its large-scale production, it can be considered as an acceptable source of the squalene overall. Apart from this, avocado (34–37 mg/100 g squalene) (Gutfinger and Letan, 1974) has also been reported to contain a meager amount of squalene. Some nuts also contain small amounts of squalene, including brazil nut (145.8 mg/100 g) (Derewiaka et al., 2014), peanut (27.4–132.9 mg/100 g) (Frega et al., 1992; Tuberoso et al., 2007; Pokkanta et al., 2019), hazelnut (9.3–39.2 mg/100 g) (Frega et al., 1992; Bada et al., 2004; Derewiaka et al., 2014), macadamia (7.2–38.3 mg/100 g) (Maguire et al., 2004; Wall, 2010; Derewiaka et al., 2014), pecan (20.8–29.8 mg/100 g) (Derewiaka et al., 2014; Fernandes et al., 2017), pistachio (5.5–22.6 mg/100 g) (Derewiaka et al., 2014; Salvo et al., 2017), cashew (11.6 mg/100 g) (Derewiaka et al., 2014), almond (1.3–9.6 mg/100 g) (Liu et al., 1976; Fernandes et al., 2017), and walnut (0.09–0.94 mg/100 g).”

Following the correction in the concentration of squalene in rape seed in Table 1, the value of the same in the manuscript (“Squalene From Plants”; paragraph 3) been corrected as 43.7 mg of squalene per 100 gm DCW.

Additionally, in paragraph 4, the following correction has been made: “Similarly, soybean, sunflower, canola, and palm fatty acid distillates encompass about 18–35, 43–45, 30–35, and 2–13 g/kg of squalene, respectively (Naziri et al., 2011b)” has been changed to “Similarly, soybean, sunflower, canola, and palm fatty acid distillates encompass about 18–55, 43–45, 30–35, and 2–13 g/kg of squalene, respectively (Dumont and Narine, 2007; Naziri et al., 2011b; Naz et al., 2014).”

Two corrections have been made in “Fermentation Optimization for Squalene Production.” In paragraph 2, “The maximum squalene production was noted to be 2.97 ± 0.12 and 3.13 ± 0.11 mg/L, whilst productivity of 0.10 ± 0.04 and 0.16 ± 0.05 mg/L/h was gained for S. cerevisiae BY4741 and EGY48, respectively (Mantzouridou et al., 2009).” has been changed to “The maximum squalene production was noted to be 2.97 ± 0.12 and 3.13 ± 0.11 mg/L, whilst productivity of 0.10 and 0.16 mg/L/h was gained for S. cerevisiae BY4741 and EGY48, respectively (Mantzouridou et al., 2009).”.

In paragraph 3, It was stated “In an experiment, squalene content was lifted to 21.2 g/L with a glucose concentration of 60 g/L.” while it should be “In an experiment, squalene content was lifted to 2.21 mg/L with a glucose concentration of 30 g/L.”

In “Engineering Saccharomyces cerevisiae for Squalene Production”, paragraph 2, “Additionally, this has been further improved to 250 mg/L by expressing the truncated HMGR (tHMGR) gene (Zhuang and Chappell, 2015).” has been changed to “Additionally, this has been further improved to 270 mg/L by expressing the truncated HMGR (tHMGR) gene (Zhuang and Chappell, 2015)”. Additionally, in paragraph 3, “Eventually, the complete biosynthetic pathway for squalene was overexpressed and that obtained a yield reaching as high as 304.09 mg/L (Rasool et al., 2016a).” has been changed to “Eventually, the complete biosynthetic pathway for squalene was overexpressed and that obtained a yield reaching as high as 304.49 mg/L (Rasool et al., 2016a).”

The authors apologize for these errors and state that this does not change the scientific conclusions of the article in any way. The original article has been updated.

References

Bada, J. C., León-Camacho, M., Prieto, M., and Alonso, L. (2004). Characterization of oils of hazelnuts from Asturias, Spain. Eur. J. Lipid Sci. Technol. 106, 294–300. doi: 10.1002/ejlt.200300922

Beltrán, G., Bucheli, M. E., Aguilera, M. P., Belaj, A., and Jimenez, A. (2016). Squalene in virgin olive oil: screening of variability in olive cultivars. Eur. J. Lipid Sci. Technol. 118, 1250–1253. doi: 10.1002/ejlt.201500295

Beveridge, T. H., Li, T. S., and Drover, J. C. (2002). Phytosterol content in American ginseng seed oil. J. Agric. Food Chem. 50, 744–750. doi: 10.1021/jf010701v

Bhattacharjee, P., Shukla, V. B., Singhal, R. S., and Kulkarni, P. R. (2001). Studies on fermentative production of squalene. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 17, 811–816. doi: 10.1023/A:1013573912952

Bhattacharjee, P., and Singhal, R. S. (2003). Extraction of squalene from yeast by supercritical carbon dioxide. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 19, 605–608. doi: 10.1023/A:1025146132281

Bondioli, P., Mariani, C., Lanzani, A., Fedeli, E., and Muller, A. (1993). Squalene recovery from olive oil deodorizer distillates. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 70, 763–766. doi: 10.1007/BF02542597

Chen, G., Fan, K. W., Lu, F. P., Li, Q., Aki, T., Chen, F., et al. (2010). Optimization of nitrogen source for enhanced production of squalene from thraustochytrid Aurantiochytrium sp. New Biotechnol. 27, 382–389. doi: 10.1016/j.nbt.2010.04.005

Choi, S. Y., Lee, H. J., Choi, J., Kim, J., Sim, S. J., Um, Y., et al. (2016). Photosynthetic conversion of CO2 to farnesyl diphosphate-derived phytochemicals (amorpha-4, 11-diene and squalene) by engineered cyanobacteria. Biotechnol. Biofuels 9:202. doi: 10.1186/s13068-016-0617-8

Choi, S. Y., Wang, J. Y., Kwak, H. S., Lee, S. M., Um, Y., Kim, Y., et al. (2017). Improvement of squalene production from CO2 in Synechococcus elongatus PCC 7942 by metabolic engineering and scalable production in a photobioreactor. ACS Synth. Biol. 6, 1289–1295. doi: 10.1021/acssynbio.7b00083

Czaplicki, S., Ogrodowska, D., Derewiaka, D., Tanska, M., and Zadernowski, R. (2011). Bioactive compounds in unsaponifiable fraction of oils from unconventional sources. Eur. J. Lipid Sci. Technol. 113, 1456–1464. doi: 10.1002/ejlt.201000410

Dai, Z., Liu, Y., Huang, L., and Zhang, X. (2012). Production of miltiradiene by metabolically engineered Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 109, 2845–2853. doi: 10.1002/bit.24547

Dai, Z., Wang, B., Liu, Y., Shi, M., Wang, D., Zhang, X., et al. (2014). Producing aglycons of ginsenosides in bakers' yeast. Sci. Rep. 4:3698. doi: 10.1038/srep03698

Derewiaka, D., Szwed, E., and Wolosiak, R. (2014). Physicochemical properties and composition of lipid fraction of selected edible nuts. Pak. J. Bot. 46, 337–343.

Drozdíková, E., Garaiová, M., Csáky, Z., Obernauerová, M., and Hapala, I. (2015). Production of squalene by lactose-fermenting yeast Kluyveromyces lactis with reduced squalene epoxidase activity. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 61, 77–84. doi: 10.1111/lam.12425

Dumont, M. J., and Narine, S. S. (2007). Characterization of flax and soybean soapstocks, and soybean deodorizer distillate by GCFID. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 84, 1101–1105. doi: 10.1007/s11746-007-1154-1

Englund, E., Pattanaik, B., Ubhayasekera, S. J. K., Stensjö, K., Bergquist, J., and Lindberg, P. (2014). Production of squalene in Synechocystis sp. PCC 6803. PLoS ONE 9:e90270. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0090270

Fagundes, M. B., Vendruscolo, R. G., Maroneze, M. M., Barin, J. S., de Menezes, C. R., Zepka, L. Q., et al. (2018). Towards a sustainable route for the production of squalene using cyanobacteria. Waste Biomass Valorization 1–8. doi: 10.1007/s12649-017-0191-8

Fan, K. W., Aki, T., Chen, F., and Jiang, Y. (2010). Enhanced production of squalene in the thraustochytrid Aurantiochytrium mangrovei by medium optimization and treatment with terbinafine. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 26, 1303–1309. doi: 10.1007/s11274-009-0301-2

Fernandes, G. D., Gómez-Coca, R. B., Pérez-Camino, M. D. C., Moreda, W., and Barrera-Arellano, D. (2017). Chemical characterization of major and minor compounds of nut oils: almond, hazelnut, and pecan nut. J. Chem. 2017:2609549. doi: 10.1155/2017/2609549

Frega, N., Bocci, F., and Lercker, G. (1992). Direct gas chromatographic analysis of the unsaponifiable fraction of different oils with a polar capillary column. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 69, 447–450. doi: 10.1007/BF02540946

Furubayashi, M., Li, L., Katabami, A., Saito, K., and Umeno, D. (2014a). Construction of carotenoid biosynthetic pathways using squalene synthase. FEBS Lett. 588, 436–442. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2013.12.003

Garaiová, M., Zambojová, V., Šimová, Z., Griač, P., and Hapala, I. (2014). Squalene epoxidase as a target for manipulation of squalene levels in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. FEMS Yeast Res. 14, 310–323. doi: 10.1111/1567-1364.12107

Ghimire, G. P., Lee, H. C., and Sohng, J. K. (2009). Improved squalene production via modulation of the methyl-erythritol 4-phosphate pathway and heterologous expression of genes from Streptomyces peucetius ATCC 27952 in Escherichia coli. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 75, 7291–7293. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01402-09

Giacometti, J., and Milin, C. (2001). Composition and qualitative characteristics of virgin olive oils produced in northern Adriatic region, Republic of Croatia. Grasas Aceites 52, 397–402. doi: 10.3989/gya.2001.v52.i6.350

Goh, S. H., Choo, Y. M., and Ong, S. H. (1985). Minor constituents of palm oil. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 62, 237–240. doi: 10.1007/BF02541384

Grigoriadou, D., Androulaki, A., Psomiadou, E., and Tsimidou, M. Z. (2007). Solid phase extraction in the analysis of squalene and tocopherols in olive oil. Food Chem. 105, 675–680. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2006.12.065

Gunawan, S., Kasim, N. S., and Ju, Y. H. (2008). Separation and purification of squalene from soybean oil deodorizer distillate. Sep. Purif. Technol. 60, 128–135. doi: 10.1016/j.seppur.2007.08.001

Gutfinger, T., and Letan, A. (1974). Studies of unsaponifiables in several vegetable oils. Lipids 9, 658–663. doi: 10.1007/BF02532171

Han, J. Y., Seo, S. H., Song, J. M., Lee, H., and Choi, E. S. (2018). High-level recombinant production of squalene using selected Saccharomyces cerevisiae strains. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 45, 239–251. doi: 10.1007/s10295-018-2018-4

He, H. P., and Corke, H. (2003). Oil and squalene in amaranthus grain and leaf. J. Agric. Food Chem. 51, 7913–7920. doi: 10.1021/jf030489q

Hoang, L. A. T., Nguyen, H. C., Le, T. T., Hoang, T. H. Q., Pham, V. N., Hoang, M. H. T., et al. (2018). Different fermentation strategies by Schizochytrium mangrovei strain pq6 to produce feedstock for exploitation of squalene and omega-3 fatty acids. J. Phycol. 54, 550–556. doi: 10.1111/jpy.12757

Hoang, M. H., Ha, N. C., Tam, L. T., Anh, H. T. L., Thu, N. T. H., and Hong, D. D. (2014). Extraction of squalene as value-added product from the residual biomass of Schizochytrium mangrovei PQ6 during biodiesel producing process. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 118, 632–639. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiosc.2014.05.015

Huang, Y. Y., Jian, X. X., Lv, Y. B., Nian, K. Q., Gao, Q., Chen, J., et al. (2018). Enhanced squalene biosynthesis in Yarrowia lipolytica based on metabolically engineered acetyl-CoA metabolism. J. Biotechnol. 281, 106–114. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2018.07.001

Hull, C. M., Loveridge, E. J., Rolley, N. J., Donnison, I. S., Kelly, S. L., and Kelly, D. E. (2014). Co-production of ethanol and squalene using a Saccharomyces cerevisiae ERG1 (squalene epoxidase) mutant and agro-industrial feedstock. Biotechnol. Biofuels 7:133. doi: 10.1186/s13068-014-0133-7

Kajikawa, M., Kinohira, S., Ando, A., Shimoyama, M., Kato, M., and Fukuzawa, H. (2015). Accumulation of squalene in a microalga Chlamydomonas reinhardtii by genetic modification of squalene synthase and squalene epoxidase genes. PLoS ONE 10:e0120446. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0120446

Kamimura, N., Hidaka, M., Masaki, H., and Uozumi, T. (1994). Construction of squalene-accumulating Saccharomyces cerevisiae mutants by gene disruption through homologous recombination. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 42, 353–357. doi: 10.1007/s002530050262

Katabami, A., Li, L., Iwasaki, M., Furubayashi, M., Saito, K., and Umeno, D. (2015). Production of squalene by squalene synthases and their truncated mutants in Escherichia coli. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 119, 165–171. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiosc.2014.07.013

Kaya, K., Nakazawa, A., Matsuura, H., Honda, D., Inouye, I., and Watanabe, M. M. (2011). Thraustochytrid Aurantiochytrium sp. 18 W-13a accumulates high amounts of squalene. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 75, 2246–2248. doi: 10.1271/bbb.110430

Kwak, S., Kim, S. R., Xu, H., Zhang, G. C., Lane, S., Kim, H., et al. (2017). Enhanced isoprenoid production from xylose by engineered Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 114, 2581–2591. doi: 10.1002/bit.26369

Lanzón, A., Albi, T., Cert, A., and Gracián, J. (1994). The hydrocarbon fraction of virgin olive oil and changes resulting from refining. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 71, 285–291. doi: 10.1007/BF02638054

Lau, H. L., Puah, C. W., Choo, Y. M., Ma, A. N., and Chuah, C. H. (2005). Simultaneous quantification of free fatty acids, free sterols, squalene, and acylglycerol molecular species in palm oil by high-temperature gas chromatography-flame ionization detection. Lipids 40, 523–528. doi: 10.1007/s11745-005-1413-1

Liu, G. C., Ahrens, E. H., Schreibman, P. H., and Crouse, J. R. (1976). Measurement of squalene in human tissues and plasma: validation and application. J. Lipid Res. 17, 38–45.

Lyon, C.K., and Becker, R. (1987). Extraction and refining of oil from amaranth seed. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 64, 233–236. doi: 10.1007/bf02542008

Maguire, L. S., O'Sullivan, S. M., Galvin, K., O'Connor, T. P., and O'Brien, N. M. (2004). Fatty acid profile, tocopherol, squalene and phytosterol content of walnuts, almonds, peanuts, hazelnuts and the macadamia nut. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 55, 171–178. doi: 10.1080/09637480410001725175

Mantzouridou, F., Naziri, E., and Tsimidou, M. Z. (2009). Squalene versus ergosterol formation using Saccharomyces cerevisiae: combined effect of oxygen supply, inoculum size, and fermentation time on yield and selectivity of the bioprocess. J. Agric. Food Chem. 57, 6189–6198. doi: 10.1021/jf900673n

Mantzouridou, F., and Tsimidou, M. Z. (2010). Observations on squalene accumulation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae due to the manipulation of HMG2 and ERG6. FEMS Yeast Res. 10, 699–707. doi: 10.1111/j.1567-1364.2010.00645.x

Manzi, P., Panfili, G., Esti, M., and Pizzoferrato, L. (1998). Natural antioxidants in the unsaponifiable fraction of virgin olive oils from different cultivars. J. Sci. Food Agric. 77, 115–120. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0010(199805)77:1<115::AID-JSFA13>3.0.CO;2-N

Matthaus, B., and Özcan, M. M. (2014). Fatty acid, tocopherol and squalene contents of Rosaceae seed oils. Bot. Stud. 55:48. doi: 10.1186/s40529-014-0048-4

Nakazawa, A., Matsuura, H., Kose, R., Kato, S., Honda, D., Inouye, I., et al. (2012). Optimization of culture conditions of the thraustochytrid Aurantiochytrium sp. strain 18W-13a for squalene production. Bioresour. Technol. 109, 287–291. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2011.09.127

Naz, S., Sherazi, S. T. H., Talpur, F. N., Kara, H., Uddin, S., and Khaskheli, R. (2014). Chemical characterization of canola and sunflower oil deodorizer distillates. Pol. J. Food Nutr. Sci. 64, 115–120. doi: 10.2478/pjfns-2013-0008

Naziri, E., Mantzouridou, F., and Tsimidou, M. Z. (2011a). Enhanced squalene production by wild-type Saccharomyces cerevisiae strains using safe chemical means. J. Agric. Food Chem. 59, 9980–9989. doi: 10.1021/jf201328a

Naziri, E., Mantzouridou, F., and Tsimidou, M. Z. (2011b). Squalene resources and uses point to the potential of biotechnology. Lipid Technol. 23, 270–273. doi: 10.1002/lite.201100157

Naziri, E., Mantzouridou, F., and Tsimidou, M. Z. (2012). Recovery of squalene from wine lees using ultrasound assisted extraction - a feasibility study. J. Agric. Food Chem. 60, 9195–9201. doi: 10.1021/jf301059y

Nenadis, N., and Tsimidou, M. (2002). Determination of squalene in olive oil using fractional crystallization for sample preparation. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 79, 257–259. doi: 10.1007/s11746-002-0470-1

Pan, J. J., Solbiati, J. O., Ramamoorthy, G., Hillerich, B. S., Seidel, R. D., Cronan, J. E., et al. (2015). Biosynthesis of squalene from farnesyl diphosphate in bacteria: three steps catalyzed by three enzymes. ACS Cent. Sci. 1, 77–82. doi: 10.1021/acscentsci.5b00115

Paramasivan, K., and Mutturi, S. (2017). Regeneration of NADPH coupled with HMG-CoA reductase activity increases squalene synthesis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Agric. Food Chem. 65, 8162–8170. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.7b02945

Pokkanta, P., Sookwong, P., Tanang, M., Setchaiyan, S., Boontakham, P., and Mahatheeranont, S. (2019). Simultaneous determination of tocols, γ-oryzanols, phytosterols, squalene, cholecalciferol and phylloquinone in rice bran and vegetable oil samples. Food Chem. 271, 630–638. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2018.07.225

Polakowski, T., Stahl, U., and Lang, C. (1998). Overexpression of a cytosolic hydroxymethylglutaryl-CoA reductase leads to squalene accumulation in yeast. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 49, 66–71. doi: 10.1007/s002530051138

Posada, L. R., Shi, J., Kakuda, Y., and Xue, S. J. (2007). Extraction of tocotrienols from palm fatty acid distillates using molecular distillation. Sep. Purif. Technol. 57, 220–229. doi: 10.1016/j.seppur.2007.04.016

Rasool, A., Ahmed, M. S., and Li, C. (2016a). Overproduction of squalene synergistically downregulates ethanol production in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Chem. Eng. Sci. 152, 370–380. doi: 10.1016/j.ces.2016.06.014

Rasool, A., Zhang, G., Li, Z., and Li, C. (2016b). Engineering of the terpenoid pathway in Saccharomyces cerevisiae co-overproduces squalene and the non-terpenoid compound oleic acid. Chem. Eng. Sci. 152, 457–467. doi: 10.1016/j.ces.2016.06.004

Rosales-García, T., Jiménez-Martínez, C., Cardador-Martínez, A., Martín-del Campo, S. T., Galicia-Luna, L. A., Téllez-Medina, D. I., et al. (2017b). Squalene extraction by supercritical fluids from traditionally puffed Amaranthus hypochondriacus seeds. J. Food Qual. 2017:6879712. doi: 10.1155/2017/6879712

Rudzinska, M., Górnaś, P., Raczyk, M., and Soliven, A. (2017). Sterols and squalene in apricot (Prunus armeniaca L.) kernel oils: the variety as a key factor. Nat. Prod. Res. 31, 84–88. doi: 10.1080/14786419.2015.1135146

Rukmini, C., and Raghuram, T. C. (1991). Nutritional and biochemical aspects of the hypolipidemic action of rice bran oil: a review. J. Am. Coll. Nutr. 10, 593–601. doi: 10.1080/07315724.1991.10718181

Ryan, E., Galvin, K., O'connor, T. P., Maguire, A. R., and O'brien, N. M. (2006). Fatty acid profile, tocopherol, squalene and phytosterol content of brazil, pecan, pine, pistachio and cashew nuts. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 57, 219–228. doi: 10.1080/09637480600768077

Salvo, A., La Torre, G. L., Di Stefano, V., Capocchiano, V., Mangano, V., Saija, E., et al. (2017). Fast UPLC/PDA determination of squalene in Sicilian PDO pistachio from Bronte: optimization of oil extraction method and analytical characterization. Food Chem. 221, 1631–1636. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2016.10.126

Song, X., Wang, X., Tan, Y., Feng, Y., Li, W., and Cui, Q. (2015). High production of squalene using a newly isolated yeast-like strain Pseudozyma sp. SD301. J. Agric. Food Chem. 63, 8445–8451. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.5b03539

Tanska, M., Roszkowska, B., Skrajda, M., and Dabrowski, G. (2016). Commercial cold pressed flaxseed oils quality and oxidative stability at the beginning and the end of their shelf life. J. Oleo Sci. 65, 111–121. doi: 10.5650/jos.ess15243

Tokuhiro, K., Muramatsu, M., Ohto, C., Kawaguchi, T., Obata, S., Muramoto, N., et al. (2009). Overproduction of geranylgeraniol by metabolically engineered Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 75, 5536–5543. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00277-09

Tuberoso, C. I., Kowalczyk, A., Sarritzu, E., and Cabras, P. (2007). Determination of antioxidant compounds and antioxidant activity in commercial oilseeds for food use. Food Chem. 103, 1494–1501. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2006.08.014

Wall, M. M. (2010). Functional lipid characteristics, oxidative stability, and antioxidant activity of macadamia nut (Macadamia integrifolia) cultivars. Food Chem. 121, 1103–1108. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2010.01.057

Wei, L. J., Kwak, S., Liu, J. J., Lane, S., Hua, Q., Kweon, D. H., et al. (2018). Improved squalene production through increasing lipid contents in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 115, 1793–1800. doi: 10.1002/bit.26595

Wejnerowska, G., Heinrich, P., and Gaca, J. (2013). Separation of squalene and oil from Amaranthus seeds by supercritical carbon dioxide. Sep. Purif. Technol. 110, 39–43. doi: 10.1016/j.seppur.2013.02.032

Wen, X., Zhu, M., Hu, R., Zhao, J., Chen, Z., Li, J., et al. (2016). Characterisation of seed oils from different grape cultivars grown in China. J. Food Sci. Technol. 53, 3129–3136. doi: 10.1007/s13197-016-2286-9

Xu, W., Chai, C., Shao, L., Yao, J., and Wang, Y. (2016). Metabolic engineering of Rhodopseudomonas palustris for squalene production. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 43, 719–725. doi: 10.1007/s10295-016-1745-7

Keywords: squalene, metabolic engineering, fermentation, biosynthesis, production, synthetic biology, anti-oxidant, anti-aging

Citation: Gohil N, Bhattacharjee G, Khambhati K, Braddick D and Singh V (2019) Corrigendum: Engineering Strategies in Microorganisms for the Enhanced Production of Squalene: Advances, Challenges and Opportunities. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 7:114. doi: 10.3389/fbioe.2019.00114

Received: 08 April 2019; Accepted: 07 May 2019;

Published: 28 May 2019.

Edited by:

Pablo Carbonell, University of Manchester, United KingdomReviewed by:

Yan Xiao, Qingdao Institute of Bioenergy and Bioprocess Technology (CAS), ChinaCopyright © 2019 Gohil, Bhattacharjee, Khambhati, Braddick and Singh. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Vijai Singh, dmlqYWlzaW5naDE1QGdtYWlsLmNvbQ==; dmlqYWkuc2luZ2hAaWFyLmFjLmlu

Nisarg Gohil

Nisarg Gohil Gargi Bhattacharjee

Gargi Bhattacharjee Khushal Khambhati

Khushal Khambhati Darren Braddick

Darren Braddick Vijai Singh

Vijai Singh