- 1Chair of Computational Modeling of Materials in Manufacturing, ETH Zürich, Zurich, Switzerland

- 2LEM3, CNRS, University of Lorraine, Metz, France

Designing biomimetic artificial tendons requires a thorough, data-based understanding of the tendon's inner material properties. The current work exploits viscoelastic experimental observations at the tendon fascicle scale, making use of mechanical and data analysis methods. More specifically, based on reported elastic, volumetric and relaxation fascicle scale properties, we infer most probable, mechanically compatible material attributes at the fiber scale. In particular, the work provides pairs of elastic and viscous fiber-scale moduli, which can reproduce the upper scale tendon mechanics. The computed range of values for the fiber-scale tendon viscosity attest to the substantial stress relaxation capabilities of tendons. More importantly, the reported mechanical parameters constitute a basis for the design of tendon-specific restoration materials, such as fiber-based, engineering scaffolds.

Introduction

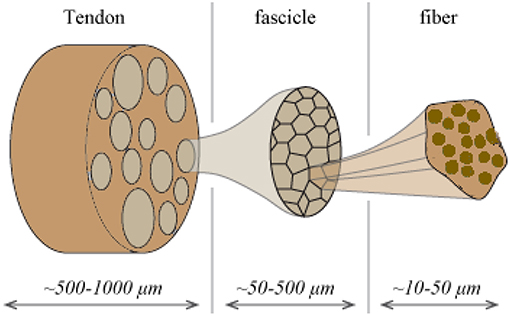

Tendons are natural fibrous tissues that transfer mechanical loads from the muscles to the bones. They are structured in a highly hierarchical manner (Maceri et al., 2012), consisting of a series of inner fibrillar scales that are immersed in a matrix substance (Shen, 2010; Zhang et al., 2014). As for their structural arrangement, both human and animal tendon specimens have been commonly described as a multiscale composite materials. The tendon unit consists of fascicles (at the scale of hundreds of micrometers), which are in turn composed of matrix-immersed fibers (micrometer). Figure 1 provides a schematic representation of the tendon's inner multiscale architecture (Figure 1) (Goh et al., 2008; Thorpe et al., 2014).

Figure 1. Schematic representation of the tendon's hierarchical inner structure: fibers are enclosed into fascicles which form the tendon macrostructure.

The tendons' inner fibrillar components are not parallel to the length evolution of the tendon. On the contrary, they are structured in helical patterns (Orgel et al., 2006), forming an undulated inner structure; an observation reported in different microscopy based studies (Yahia and Drouin, 1989; de Campos Vidal, 2003). Their helical arrangement, with a typical angular range in between 70 and 76° with respect to the plane normal to the tendon axis evolution (Järvinen et al., 2004; Starborg et al., 2013), leads to a characteristic coupled axial and torsional behavior at the fascicle scale (Thorpe et al., 2013). The effective mechanical behavior at the tendon macroscale, arises as a rather complex function of the properties of its inner constituents (Reese et al., 2013). The latter have been commonly measured by elastic, uniaxial strain experiments, carried out independently at the different inner tendon scales (Figure 1). At the lower scale of fibers, elastic moduli values of Ef = 0.57 ± 0.08 GPa and Ef = 2.69 ± 0.42 GPa have been reported for wet and dry rat tail tendon fiber specimens, respectively (Kato et al., 1989). Independent experimental studies provided moduli values of Ef = 1.17 ± 0.28 GPa for hydrated fiber tendon specimens (Gentleman et al., 2003), within the range reported by Kato et al. (1989). At the uppermost inner hierarchical scale of fascicles, experimental data suggest a substantially lower overall uncertainty. In particular, elastic moduli values of Efasc = 0.64 ± 0.03 GPa, Efasc = 0.48 ± 0.07 GPa, and Efasc = 0.55 ± 0.14 GPa have been reported (Derwin and Soslowsky, 1999; Lavagnino et al., 2005; Haraldsson et al., 2009; Svensson et al., 2010), exhibiting a maximum difference of 0.2 GPa with respect to their mean value.

The overall decrease observed in the elastic moduli of the upper scales is to be primarily attributed to the presence of the non-collagenous matrix substance (Figure 1). The latter has a quasi-negligible stiffness contribution with respect to the one provided by the fibrillar components. While no direct experimental measurement is available, analytical computations have estimated a matrix modulus Em below 1 MPa (Ault and Hoffman, 1992) that is more than two orders of magnitude lower than the one reported for any fibrillary component measurement (Thorpe et al., 2017); a value that has been typically employed in numerical studies (Reese et al., 2010). The content of fibers fr within fascicles (Figure 1) varies with the tendon's age and health state (Lavagnino et al., 2005; Svensson et al., 2010). Relevant studies provide fibrillar contents fr as low as 35% when a certain level of fiber swelling is accounted for (Svensson et al., 2012) and up to more than 60% (Hansen et al., 2010; Svensson et al., 2010).

The combination of high moduli differences amongst the embedding matrix and the fibrillar components (Ef >> Em), along with the helical arrangement of the tendon subunits have been shown to constitute the basic mechanisms responsible for the tendon's distinctive volumetric behavior (Reese et al., 2010; Swedberg et al., 2014; Karathanasopoulos et al., 2017). More specifically, experimental observations have reported Poisson's ratio values ν that well-exceed the ones observed in common engineering materials. In particular, mean Poisson's ratio values close to unity (Cheng and Screen, 2007) and up to 3 have been reported (Lynch, 2003), accompanied by substantial uncertainties.

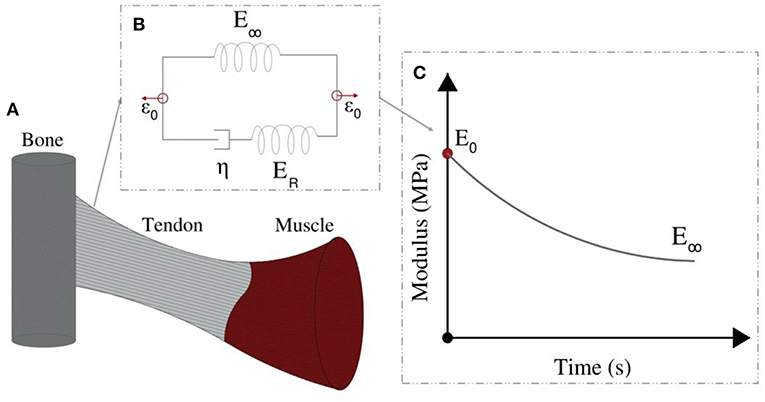

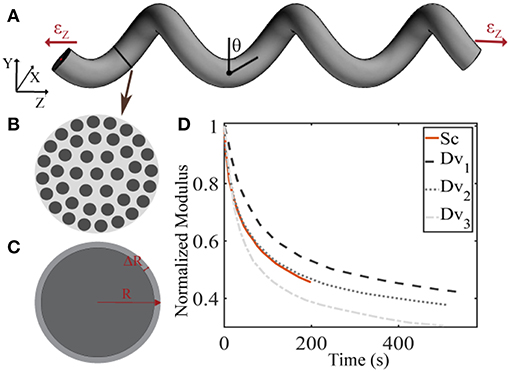

The linear elastic response cannot however explicate the considerable stress and shock absorption capacities of tendons (Salathe and Arangio, 1990), which are directly associated to a viscous, time-dependent behavior. The tendon's viscoelastic nature allows for the attenuation of stress stimuli and is commonly characterized by a viscosity parameter η, which is directly related to a relaxation time τ (Lakes, 2009), as schematically depicted in Figure 2. Tendon inner scales have been shown to yield a viscoelastic, time-dependent response, which however has not been typically characterized with respect to its effective viscosity value η. In particular, at the tendon fascicle scale, relaxation curves with a time-dependent modulus evolution over a range of 200 s and up to more than 500 s have been provided in independent experimental studies (Screen, 2008; Davis and De Vita, 2012) (Figure 3D). Relaxation experiments suggest a loss of 40–70% of the initial elastic modulus at the tendon fascicle scale over this time interval (Screen, 2008).

Figure 2. Tendons transfer forces from muscles to bones (A). Their modulus depends on the loading time (C). Their relaxation behavior can be represented by the Standard linear solid model (B).

Figure 3. Schematic representation of the tendon fascicle's helical geometry (A) that is composed of matrix-embedded fibers (B) (Goh et al., 2008), with a Poisson's ratio behavior (C) that is dependent on the fascicle's structural composition (B) and geometry (A). In subplot (D), the tendon fascicle's experimental relaxation curves as provided by Screen (2008) (Sc) and Davis and De Vita (2012) (Dv) are summarized.

The material properties of the tendon building blocks considerably affect its functionality and its load transfer efficiency (Rawson et al., 2015); parameters of primal importance for connective tissues (Galbusera et al., 2014). A thorough quantification of the material properties of the tendons' inner constituents is essential, not only for the understanding of its nature (Balint et al., 2014), but most importantly for any repair and restoration process to take place (Robinson et al., 2004; Laurent et al., 2014; Lee et al., 2017). Up to now, restoration processes have primarily used biological and synthetic scaffolds (Kuo et al., 2010; Kwon et al., 2014; Sandri et al., 2016). Biological treatments employed biodegradable silk-collagen scaffolds that were meant to provide advanced regeneration capabilities (Abdullah, 2015). Synthetic replacements were based on textile scaffolds selected out of a list of existing substitutes (Lomas et al., 2015). However, scaffolds of the kind have been reported to show limited mechanical biocompatibility (Ratcliffe et al., 2015; Tang et al., 2018). Statistical data on the success of surgical restorations reveal rather low success rates. More specifically, for tendons injuries with large and extensive damage, the mean post-surgical, operation success rate does not exceed a mere 50 and 40%, accordingly (Meimandi-Parizi et al., 2013).

A part of the low efficiency of current restoration practices needs to be attributed to the rather limited understanding of the tendon's inner material properties (Kuo et al., 2010), in particular with respect to its viscoelastic properties (Ganghoffer et al., 2016). The latter depend both on the physiology and on the loading type applied (e.g., quasi-static, high strain rate) (Oftadeh et al., 2018; Wu et al., 2018; Kuznetsov et al., 2019). The use of biocompatible materials, which mimic the physiological functionality of the native tissue constitutes a key aspect for any tendon restoration process (Ganghoffer et al., 2016). During the last years, substantial efforts have been devoted to the engineering of novel biomaterials with enhanced structural performance and improved biochemical compatibility (Zhang et al., 2017; Li et al., 2018a,b; Li S. et al., 2018; Liu et al., 2018). However, primal tendon inner material attributes, such as the effective viscosity at the tendon fiber scale remain unquantified.

In the current work, numerical models that describe the tendon's fascicle and fiber scale mechanics are combined with probabilistic inference models and experimental observations. By that means, a quantitative link between the tendon's viscoelastic mechanical response at the fascicle scale and experimental data is established, through a Bayesian inference framework (Papadopoulos et al., 2012; Taflanidis and Beck, 2013; Farrell et al., 2015). This allows for the quantification of uncertain tendon inner mechanical parameters that determine the experimentally observed fascicle-scale mechanics. The paper is structured as follows: in section Materials and Methods the parametrization of the fascicle's viscoelastic models is provided and the mathematical formalism of the Bayesian probabilistic framework is discussed (section Inference of the Fascicle's Viscoelastic Mechanical Properties), summarizing the experimental data used for the study (section Tendon Fascicle Experimental Data). In section Results, the results of the inference process are provided, namely the elastic and viscous fiber-scale material properties, which can reproduce the experimental observations reported at the fascicle scale. The work continuous with an overall discussion of the obtained results and a concluding summary in section Discussion and Conclusions.

Materials and Methods

Tendon Fascicle Geometry and Mechanical Models

We describe the fascicle's elastic and viscoelastic relaxation response in a two-step process. More specifically, we compute its elastic response with a dedicated composite helical fascicle finite element model, which is comprised of fibers immersed in a matrix substance, detailed in Karathanasopoulos et al. (2017). The fascicle geometry follows a helical angle θ, with respect to the plane perpendicular to the tendon evolution, as schematically depicted in Figure 3A. The fascicle contains fibers in different fiber contents fr defined as the ratio of the area Af covered by fibers (dark-gray) over the total fascicle cross sectional area At (Figure 3B). We allow for the composition of fascicles to vary so that different fiber contents are captured. More specifically, in order to take into consideration a large part of the experimentally observed fascicle compositions (Goh et al., 2008; Hansen et al., 2010; Svensson et al., 2012), we build fascicle models with fiber contents of 35% up to 65% with a spacing of 5%, accounting for a fiber swelling in the determination of the upper content limit (Hansen et al., 2010). For the linear finite element computations, the fascicles' domain covered by fibers is assigned a Young's modulus Ef, while the matrix a modulus Em. The model computes the effective fascicle modulus Efasc and the fascicle's volumetric behavior νfasc = ΔR/R/εz (Figure 3C) for different fiber content values fr and angular arrangements θ (Figure 3A), which are considered to define distinct fascicle model classes . Both parameters are complex functions (f) of the tendon fascicle's inner material and geometric properties f(fr, θ, Ef, Em) (Reese et al., 2010, 2013; Karathanasopoulos et al., 2017). We enumerate a total of 49 fascicle model classes each i uniquely referring to a pair . The reader is referred to Karathanasopoulos and Hadjidoukas (2016) and Karathanasopoulos et al. (2017) for a detailed description of the numerical modeling specifications and for a quantification of the associated computational cost.

Following the linear computation, the relaxation response of the tendon fascicle is computed, using a Maxwell standard linear solid model (Figure 2). The time-dependent relaxation curve is characterized by a relaxation experiment, using a single viscosity parameter η, as follows (Christensen, 1982; Lakes, 2009; Shen, 2010):

where in Equation (1), ER is equal to the fiber's elastic modulus loss ER = Ef (t = 0) − E∞ during the relaxation process (Figure 2). For t = 0, the fascicles's elastic modulus is equal to its linear, non time-dependent value, so that the previous relation entails Efasc(t = 0) = fr (ER + E∞) + (1 − fr) Em (t). Noting that the matrix modulus Em has been shown to be more than two order of magnitudes lower than the one of its fibrillar components (Ef > > Em) (Ault and Hoffman, 1992; Reese et al., 2010; Karathanasopoulos et al., 2017), the primal contributors in the fascicle's relaxation curves (Figure 3D) described by Equation (1) are its embedded fibers (Em (t) ≈ 0). As a result, the fascicle's time-dependent modulus loss is essentially characterized by the relaxation behavior of its inner, matrix-embedded fibers, so that the viscous parameter 〈η〉 entering Equation (1) describes the effective -homogenized- viscosity of its embedded fibers, here named as ηf.

We subsequently parametrize each fascicle model class by a total of three parameters, namely by the elastic modulus of the fiber and of the matrix Ef and Em and by the viscous modulus of its embedded fibers ηf. We note that the fascicle's effective Poisson's ratio value νfasc is a non-linear function of its fiber content fr, angle θ (thus ) and fiber and matrix elastic moduli values Ef and Em, as elaborated in Appendix section Fascicle Poisson Ratio. Accordingly, the fascicle's time-dependent response well differs, depending on the combination of the elastic and viscous properties entering Equation (1), as demonstrated in Appendix section Fascicle Relaxation Response. Using the previously defined parameters, we compute a total of three quantities of interest for each model class , as follows:

where in Equation (2), Ēfasc(t) stands for the time-evolution of the normalized fascicle modulus, the normalization carried out with respect to its initial elastic modulus .

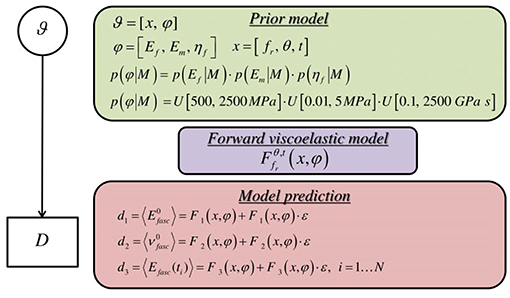

Inference of the Fascicle's Viscoelastic Mechanical Properties

The goal in parameter inference is to infer the parameters after observing the data D = {di|i = 1, …, N}. The computational model used to simulate the data D can be described through a function F(x; φ) ∈ RN, which depends on both the parameters φ and on input parameters that are not being inferred.

In Uncertainty Quantification we are interested in sampling the conditional posterior distribution p(φ|D), using the Bayes' theorem, defined as follows:

where in Equation (3) p(D|φ, M) is the likelihood function, p(φ|M) is the prior probability distribution and p(D|M) is the model evidence. Here, M stands for the model under consideration and contains all the information that describes the computational and the statistical model. The models are here parametrized by the fascicle angle θ and fibrillar content fr, denoted as , as explicated in section Tendon Fascicle Geometry and Mechanical Models. The likelihood function is a measure of the probability that the data D are reproduced by the computational model employed, while the prior probability encodes all available information before observing any data. In the present work, we make the assumption that the data Di are independent and normally distributed around the observable of the model, with a proportional model error, so that:

where the data Di are assigned a proportional error model. Using Equation (4), the likeli- hood function p(D|φ, M) takes the form:

Where the model and the error parameters can be described by the vector in a unified form. In most practical applications the posterior distribution (Equation 3) cannot be expressed analytically. Moreover, the model evidence p(D|M) is typically not known, since it is given by integration of the nominator of Equation (3) over the potentially high dimensional domain of the parameters. In the current work, we rely on efficient sampling algorithms to identify the posterior distribution. In particular, we use the Transitional Markov Chain Monte Carlo algorithm (TMCMC) (Ching and Chen, 2007; Farrell et al., 2015). The algorithm starts by sampling the prior distribution, which is usually trivial to be sampled, and through annealing steps it provides samples from the posterior distribution. One major advantage of this algorithm is its ability to sample multimodal distributions and provide low bias estimators of the model evidence (Ching and Chen, 2007).

Here, we make use of uniform prior distributions U for each of the modeling parameters φ = [Ef, ηf, Em] which encompass and exceed the range reported in the corresponding experimental observations of section Introduction, indicating prior ignorance with respect to their actual value. In particular, we allow their values to vary in between 500−2500 MPa, 0.1−2500 GPa s and 0.01−5 MPa. A graphical representation of the probability model formulation is provided in Figure 4.

Figure 4. Graphical probability model describing the formulation of the forward stochastic model used to reproduce the data D.

Tendon Fascicle Experimental Data

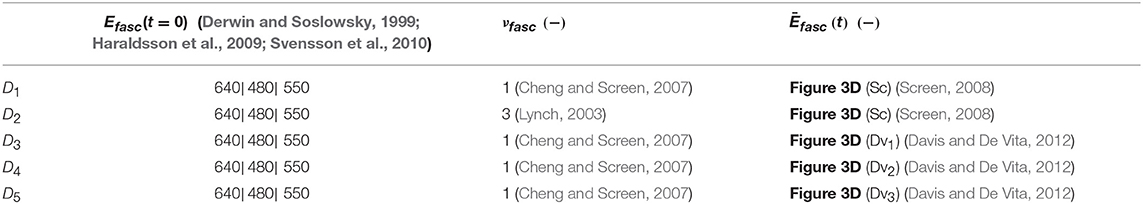

For the inference process we combine multiple available experimental data, pertaining to both the linear and the time-dependent fascicle response. In particular, for the quantities of interest q1 and q2 of Equation (2), we made use of the elastic, non time-dependent experimental data reported in Derwin and Soslowsky (1999), Haraldsson et al. (2009) and Svensson et al. (2010); and Lynch (2003) and Cheng and Screen (2007), accordingly. What is more, for the time-dependent quantity q3 of Equation (2), we digitalize the experimental relaxation curves provided in Screen (2008) and Davis and De Vita (2012) and summarized in Figure 3D, using ~30 equally spaced time-intervals along the relaxation curve, as control points for our modeling predictions. We consider a total of five groups of experimental observations D1, D2, D3, D4, and D5. Each data set Di contains a set of normalized fascicle moduli ratios Ēfasc(t), as schematically depicted in Figure 3D. In Table 1, we summarize the considered experimental measurements for each group of experimental observations.

Table 1. Fascicle experimental data sets Di encompassing the fascicle initial elastic modulus Efasc, Poisson's ratio value νfasc, and the time-dependent response of its modulus Ēfasc(t).

Results

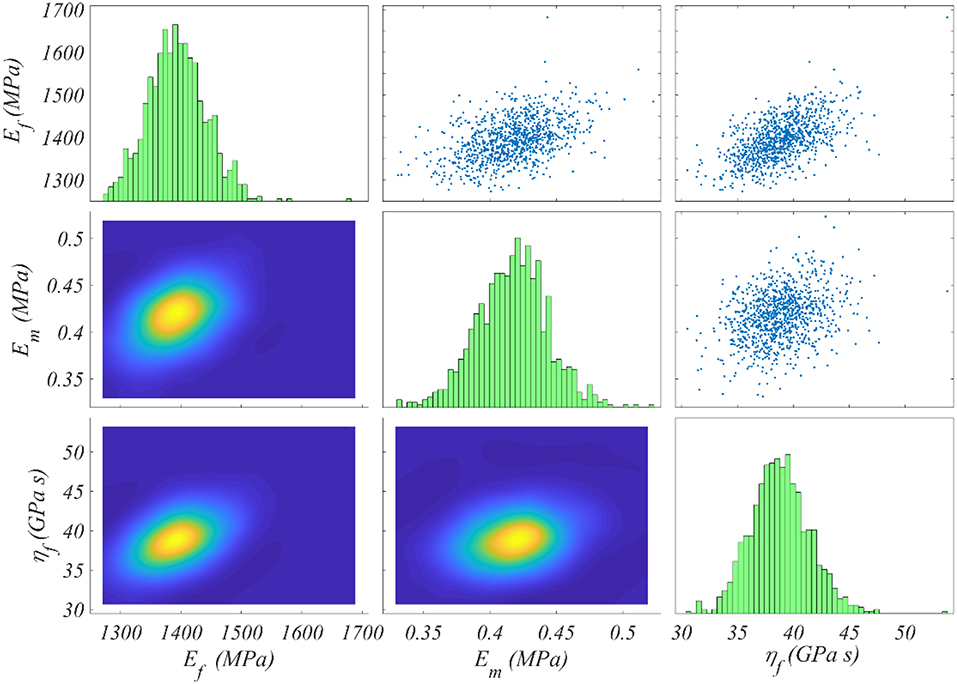

We compute the posterior sample distributions using the TMCMC algorithm elaborated in Ching and Chen (2007) for all model classes , for each of the data sets Di included in Table 1. In Figure 5 we provide the posterior frequency distribution for each of the inferred parameters φ = [Ef, ηf, Em] for the model with a fiber content fr = 35% and an angle θ = 75o. The results correspond to the data set D1 of Table 1.

Figure 5. Posterior frequency distribution of the modeling parameters φ for a model with a content fr = 35% and an angle θ = 75o. The posterior distribution corresponds to the data set D1 of Table 1.

Figure 5 depicts a posterior distribution of the modeling parameters φ with a clear clustering of values for each of the Ef, ηf, Em. In particular, for each parameter, the range of values with a non-zero posterior probability is a narrow subspace of the uniform prior used as initial modeling hypothesis and summarized in Figure 4. More specifically, the fiber modulus Ef ranges in between 1,300 and 1, 500 MPa, while the matrix modulus Em within 0.35 and 0.5 MPa. Accordingly, the entire probability mass for the viscosity parameter ηf ranges among 35 and 45 GPa s. The model proportional error (Equation 4) associated to the results of Figure 5 is restrained to a maximum of 8% for all model classes and data sets Di. Analogous posterior parameter frequency distributions with the one provided in Figure 5 are obtained for all model classes and data sets Di of Table 1.

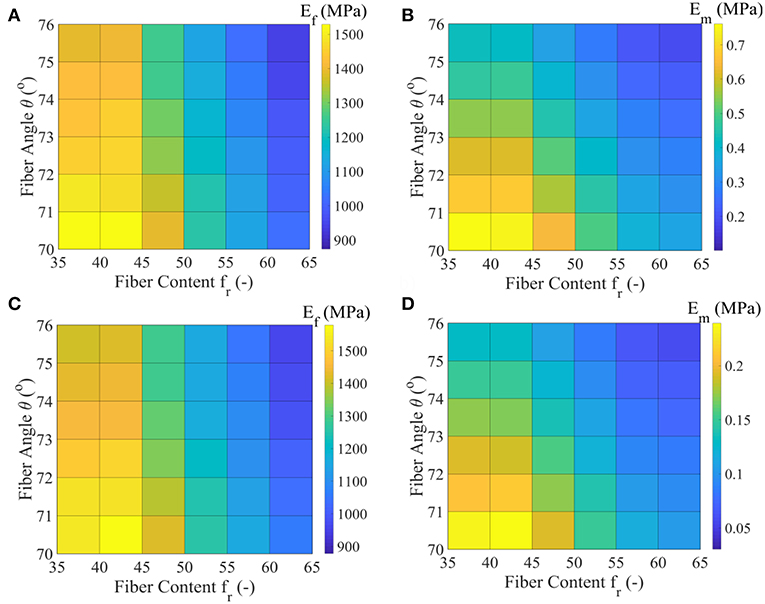

In Figures 6A,B we provide the values Ef and Em that maximize the posterior PDF for each respective model class for the data set D1. These values, named as the Maximum A-Posteriori (MAP) values are defined as . In Figures 6C,D, we provide the values for Ef and Em for the data set D2, pertaining to a fascicle Poisson's ratio value ν = 3 (Table 1).

Figure 6. Maximum A-Posteriori (MAP) values for the fiber elastic modulus Ef and matrix elastic modulus Em for the all model classes of the data set D1 (subplots A,B) and data set D2 (subplots C,D) of Table 1.

Figures 6A,C suggest a non-linear relation between the fiber modulus Ef and the fiber content fr, so that the higher the fiber content value, the lower the most probable fiber modulus value obtained. In particular, a maximum and a minimum most probable fiber modulus of approximately 1550 MPa and 900 MPa is obtained for a 35% and a 65% fiber content, accordingly. The fiber angle θ affects the magnitude of the Ef value: higher angle values θ correspond to lower fiber moduli Ef, irrespective of the fascicle's fibrillary content fr. The associated difference lies however within a maximum range of 150 MPa for a given fiber content value (Figures 6A,C).

The different fascicle Poisson's ratio values (νfasc in Table 1) used among the data sets D1 and D2, appear to minorly affect the peaks of the posterior probability distribution for Ef (Figures 6A,C), while they decisively affect the Em MAP values (Figures 6B,D). In particular, the higher fascicle Poisson's ratio value of data set D2 results in considerably reduced Em MAP values with respect to the ones computed for the data set D1. However, the dependence of Em on fr and θ is analogous to the one obtained for the fiber modulus Ef. The a-posteriori, most probable inferred fiber moduli values Ef well compare to the ones suggested by the experimental study of Gentleman et al. (2003), while the matrix modulus values Em to the analytical modeling predictions of Ault and Hoffman (1992), being smaller than 0.7 MPa in the entire parametric space. For the data sets D3 to D5 of Table 1, fiber and matrix moduli values that differ by a maximum of 5% with respect to the ones provided in Figures 6A,B are obtained. The inferred MAP values for all data sets Di and model classes are provided in the form of Supplementary Material.

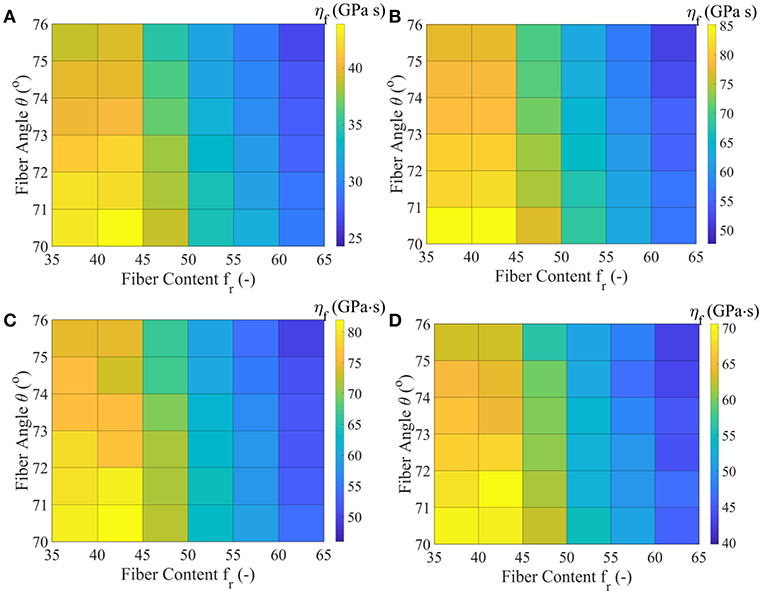

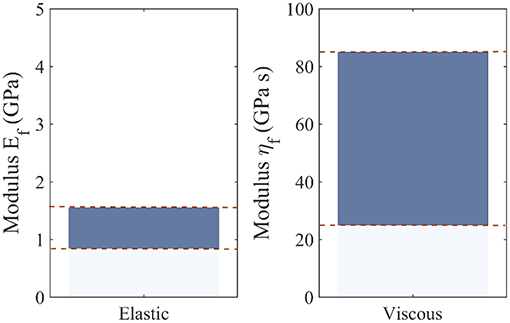

In Figure 7, we provide the MAP values for the viscoelastic modulus ηf of the matrix-embedded fibers for all model classes introduced in section Inference of the Fascicle's Viscoelastic Mechanical Properties, corresponding to the relaxation curves of Figure 3D. The maximum a-posteriori viscosity values are provided for the data sets D1, D3, D4, and D5 of Table 1.

Figure 7. MAP values for the effective viscous modulus ηf for all model classes acquired for the data-sets D1 (A), D3 (B), D4 (C), and D5 (D), as defined in Table 1.

Figure 7 suggests relaxation moduli values ηf for the embedded fibers of several tens of GPa s for all model classes and data sets Di. In particular, a minimum most probable value of approximately 25 GPa s is obtained for the highest fiber content and fiber angle model . Data set D3 yields the maximum viscosity parameter ηf = 85 GPa s for the lowest fibrillar content and fiber angle model class analyzed . The relaxation curves corresponding to data-sets D4 and D5 of Table 1 relate to a range of ηf values in between 40 and 80 GPa s. For all data sets, low fibrillar contents fr pair to high relaxation moduli values, while increased fiber angles θ to lower ηf values for a given data set Di and content value fr. We note that the linear elastic, non time-dependent fascicle Poisson's ratio value νfasc is independent of the relaxation moduli ηf, so that no significant differences arise between the inferred ηf values of data sets D1 and D2. The inferred MAP values for the parameter [Ef, ηf, Em] are provided for all data sets Di and model classes in the form of Supplementary Material. Each set of material properties provided in Figures 6, 7 can well-reproduce both the elastic and the experimentally observed time-dependent fascicle behavior summarized in Table 1.

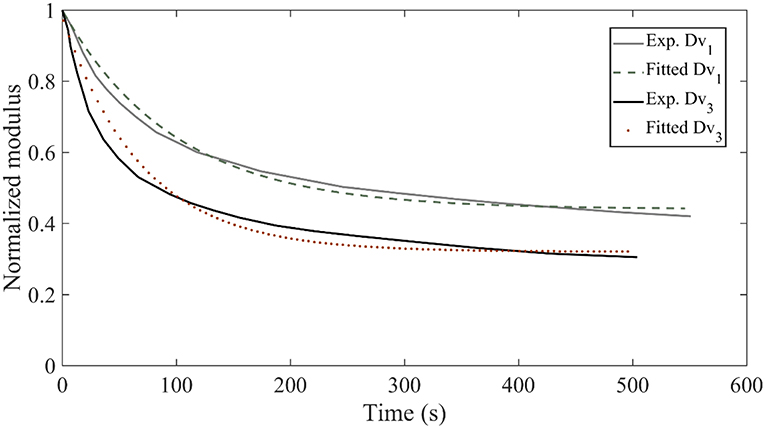

In Figure 8, we provide for verification purposes a comparison of the fascicle relaxation response as computed by the previously inferred mechanical parameters and by the experimentally provided response. To that scope, we make use of the inferred MAP elastic and viscous mechanical properties part of them depicted in Figures 6C,D, 7B,D for the model class , which we compare with the experimental curves Dv1 and Dv3, provided in Figure 3D.

Figure 8. Relaxation response for the experimental curves Dv1 and Dv3 of Figure 3D compared to the relaxation response obtained with the inferred mechanical properties of the data sets D3 and D5 for the model class .

Figure 8 suggests a very good agreement between the experimental relaxation response and the relaxation behavior arising from the inferred mechanical properties. Analogous behavior is obtained for all model classes and data sets Di of Table 1.We note that non-optimized sets of the parameters Ef, Em, ηf lead to utterly different fascicle relaxation behaviors, as elaborated and showcased in Appendix section Fascicle Relaxation Response.

Discussion and Conclusions

Knowledge of the tendon's inner material properties is a primal prerequisite for the application of any successful treatment or restoration process (Snedeker and Foolen, 2017; Karathanasopoulos et al., 2019). However, experimental data on the material attributes of inner, lower tendon subunits are commonly highly uncertain, while fundamental parameters, such as the ηf of tendon fibers remain unquantified (section Introduction). Combining upper (fascicle) and lower (fiber) tendon scale mechanics with experimental observations, provides a means to infer and quantify lower scale tendon mechanical properties, so that they are able to reproduce upper scale mechanics.

The inferred fiber scale mechanics indicate that the most probable fiber modulus values Ef range between 900 and 1, 600 MPa (Figure 6), thus in a subspace of the literature reported range of moduli (Kato et al., 1989; Gentleman et al., 2003), when using experimental observations at the fascicle tendon scale. In particular, if information on the fibrillar content value fr is provided, the fiber modulus Ef can be estimated, within a range of 200 MPa when the 95% of the mass of the posterior probability distribution is accounted for (Figure 5). Moreover, for the observed volumetric behaviors at the fascicle scale to be retrieved (Table 1), a matrix modulus Em below 1 MPa is required for all fibrillar content and fiber angle values model classes . Increased fascicle lateral volumetric contractions are obtained by decreasing the matrix modulus Em (Figure 6), thus by increasing the relative contrast of elastic properties Ef/Em at the fiber scale.

The viscous moduli ηf values provided in Figure 7 constitute the first quantitative estimates of the embedded fiber viscosity that is based on experimental observations. For a given fascicle composition and data set Di, the posterior distribution of the embedded fiber viscosity suggests ηf values which at most differ by 10 GPa s (Figure 5), considering the entire mass of the posterior probability distribution. For fascicles with a low fibrillar content and fiber angle, most probable ηf values of more than 40 GPa s are obtained, irrespective of the data-set Di considered (Figure 7). The values of Figure 7 combined with the most probable fiber elastic moduli values of Figure 6 can be viewed as a fundamental reference table in the design of artificial tendons. In particular, each pair of most probable Ef, ηf values can be used as a set of basic elastic and time-dependent material properties for the engineering of artificial fibers in scaffold-based tendon restoration processes (Kuo et al., 2010; Abdullah, 2015; Sandri et al., 2016).

Note that the differences observed among the most probable viscoelastic embedded fiber moduli values ηf (Figure 7) reflect to a large extent the discrepancies among the experimentally reported relaxation curves of Figure 3, as well as the wide range of possible fibrillar content values fr. Figure 9 summarizes the range of values for the most probable elastic and viscous fiber parameters (Figures 6, 7), when all fiber content values fr, fiber angles θ, and data-sets Di are considered. In order to further delimit the range of probable elastic and viscous parameters, further relaxation experiments need to be conducted at the tendon fascicle scale. The latter need to provide mean and standard deviation values for the relaxation moduli at different time-frames throughout the relaxation process at different strain magnitudes and initial loading strain-rates. Data of the kind will allow for a series of secondary analysis to be carried out, which are as of now intractable. In particular, they will allow for the consideration of more complex relaxation models with multiple relaxation times or for the modeling of strain-rate and strain-magnitude effects (Oftadeh et al., 2018). Moreover, they would allow to account for the presence of geometric or material non-linearities, phenomena which typically play a role in the mechanical behavior of biological materials (Kuznetsov et al., 2019); objectives which are way beyond the current tendon mechanics-related data availability.

Figure 9. Range of most probable elastic Ef and viscous fiber ηf moduli values, including all possible fiber content values fr, fiber orientations θ, and data-sets Di.

Author Contributions

NK: conception, design, results acquisition, and analysis. J-FG: modeling, analysis, and interpretation of results.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

NK acknowledges support of the Freenovation 2017 Grant, Switzerland and the support of the ETH CSE-Lab in the writing of the corresponding application.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fbioe.2019.00085/full#supplementary-material

Data Sheet 1. Summary of the MAP values for the datasets D1–D5 of Table 1.

References

Abdullah, S. (2015). Usage of synthetic tendons in tendon reconstruction. BMC Proc. 9:A68. doi: 10.1186/1753-6561-9-S3-A68

Ault, H. K., and Hoffman, A. H. (1992). A composite micromechanical model for connective tissues: part II—application to rat tail tendon and joint capsule. J. Biomech. Eng. 114, 142–146. doi: 10.1115/1.2895438

Balint, R., Cassidy, N. J., and Cartmell, S. H. (2014). Conductive polymers: towards a smart biomaterial for tissue engineering. Acta Biomater. 10, 2341–2353. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2014.02.015

Cheng, V. W. T., and Screen, H. R. C. (2007). The micro-structural strain response of tendon. J. Mat. Sci. 42, 8957–8965. doi: 10.1007/s10853-007-1653-3

Ching, J., and Chen, Y. (2007). Transitional Markov chain Monte Carlo method for Bayesian model updating, model class selection, and model averaging. J. Eng. Mech. 133, 816–832. doi: 10.1061/(ASCE)0733-9399(2007)133:7(816)

Davis, F. M., and De Vita, R. (2012). A nonlinear constitutive model for stress relaxation in ligaments and tendons. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 40, 1–10. doi: 10.1007/s10439-012-0596-2

de Campos Vidal, B. (2003). Image analysis of tendon helical superstructure using interference and polarized light microscopy. Micron 34, 423–432. doi: 10.1016/S0968-4328(03)00039-8

Derwin, K. A., and Soslowsky, L. J. (1999). A quantitative investigation of structure-function relationships in a tendon fascicle model. J. Biomech. Eng. 121, 598–604. doi: 10.1115/1.2800859

Farrell, K., Oden, J. T., and Faghihi, D. (2015). A bayesian framework for adaptive selection, calibration, and validation of coarse-grained models of atomistic systems. J. Comput. Phys. 295, 189–208. doi: 10.1016/j.jcp.2015.03.071

Galbusera, F., Freutel, M., Dürselen, L., D'Aiuto, M., Croce, D., Villa, T., et al. (2014). Material models and properties in the finite element analysis of knee ligaments: a literature review. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2:54. doi: 10.3389/fbioe.2014.00054

Ganghoffer, J., Laurent, C., Maurice, G., Rahouadj, R., and Wang, X. (2016). Nonlinear viscous behavior of the tendon's fascicles from the homogenization of viscoelastic collagen fibers. Eur. J. Mech. A Solids 59, 265–279. doi: 10.1016/j.euromechsol.2016.04.006

Gentleman, E., Lay, A. N., Dickerson, D. A., Nauman, E. A., Livesay, G. A., and Dee, K. C. (2003). Mechanical characterization of collagen fibers and scaffolds for tissue engineering. Biomaterials 24, 3805–3813. doi: 10.1016/S0142-9612(03)00206-0

Goh, K. L., Holmes, D. F., Lu, H.-Y., Richardson, S., Kadler, K. E., Purslow, P. P., et al. (2008). Ageing changes in the tensile properties of tendons: influence of collagen fibril volume fraction. J. Biomech. Eng. 130:021011. doi: 10.1115/1.2898732

Hansen, P., Haraldsson, B. T., Aagaard, P., Kovanen, V., Avery, N. C., Qvortrup, K., et al. (2010). Lower strength of the human posterior patellar tendon seems unrelated to mature collagen cross-linking and fibril morphology. J. Appl. Physiol. 108, 47–52. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00944.2009

Haraldsson, B. T., Aagaard, P., Crafoord-Larsen, D., Kjaer, M., and Magnusson, S. P. (2009). Corticosteroid administration alters the mechanical properties of isolated collagen fascicles in rat-tail tendon. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 19, 621–626. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0838.2008.00859.x

Järvinen, T. A., Järvinen, T. L. N., Kannus, P., Józsa, L., and Järvinen, M. (2004). Collagen fibres of the spontaneously ruptured human tendons display decreased thickness and crimp angle. J. Orth. Res. 22, 1303–1309. doi: 10.1016/j.orthres.2004.04.003

Karathanasopoulos, N., Angelikopoulos, P., Papadimitriou, C., and Koumoutsakos, P. (2017). Bayesian identification of the tendon fascicle's structural composition using finite element models for helical geometries. Computer Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. 313, 744–758. doi: 10.1016/j.cma.2016.10.024

Karathanasopoulos, N., Arampatzis, G., and Ganghoffer, J.-F. (2019). Unravelling the viscoelastic, buffer-like mechanical behavior of tendons: a numerical quantitative study at the fibril-fiber scale. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 90, 256–263. doi: 10.1016/j.jmbbm.2018.10.019

Karathanasopoulos, N., and Hadjidoukas, P. (2019). TendonMech: An open source high performance code to compute the mechanical behavior of tendon fascicles. SoftwareX 9, 324–327. doi: 10.1016/j.softx.2019.04.007

Kato, Y. P., Christiansen, D. L., Hahn, R. A., Shieh, S. J., Goldstein, J. D., and Silver, F. H. (1989). Mechanical properties of collagen fibres: a comparison of reconstituted and rat tail. Biomaterials 10, 38–42. doi: 10.1016/0142-9612(89)90007-0

Kuo, C. K., Marturano, J. E., and Tuan, R. S. (2010). Novel strategies in tendon and ligament tissue engineering: advanced biomaterials and regeneration motifs. Sports Med. Arthrosc. Rehabil. Ther. Technol. 2:20. doi: 10.1186/1758-2555-2-20

Kuznetsov, S., Pankow, M., Peters, K., and Shadow Huang, H.-Y. (2019). Strain state dependent anisotropic viscoelasticity of tendon-to-bone insertion. Math. Biosci. 308, 1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.mbs.2018.12.007

Kwon, S.-Y., Chung, J.-W., Park, H.-J., Jiang, Y.-Y., Park, J.-K., and Seo, Y.-K. (2014). Silk and collagen scaffolds for tendon reconstruction. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part H 228, 388–396. doi: 10.1177/0954411914528890

Laurent, C. P., Latil, P., Durville, D., Rahouadj, R., Geindreau, C., Orgéas, L., et al. (2014). Mechanical behaviour of a fibrous scaffold for ligament tissue engineering: finite elements analysis vs. X-ray tomography imaging. J. Mech. Beh. Biomed. Mat. 40, 222–233. doi: 10.1016/j.jmbbm.2014.09.003

Lavagnino, M., Arnoczky, S. P., Frank, K., and Tian, T. (2005). Collagen fibril diameter distribution does not reflect changes in the mechanical properties of in vitro stress-deprived tendons. J. Biomech. 38, 69–75. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2004.03.035

Lee, A. H., Szczesny, S. E., Santare, M. H., and Elliott, D. M. (2017). Investigating mechanisms of tendon damage by measuring multi-scale recovery following tensile loading. Acta Biomater. 57, 363–372. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2017.04.011

Li, J., Xu, W., Chen, J., Li, D., Zhang, K., Liu, T., et al. (2018b). Highly bioadhesive polymer membrane continuously releases cytostatic and anti-inflammatory drugs for peritoneal adhesion prevention. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 4, 42026–42036. doi: 10.1021/acsbiomaterials.7b00605

Li, J., Xu, W., Li, D., Liu, T., Zhang, Y. S., Ding, J., et al. (2018a). Locally deployable nanofiber patch for sequential drug delivery in treatment of primary and advanced orthotopic hepatomas. ACS Nano 12, 6685–6699. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.8b01729

Li, S., Dong, S., Xu, W., Tu, S., Yan, L., Zhao, C., et al. (2018). Antibacterial hydrogels. Adv. Sci. 5:1700527. doi: 10.1002/advs.201700527

Liu, H., Cheng, Y., Chen, J., Chang, F., Wang, J., Ding, J., et al. (2018). Component effect of stem cell-loaded thermosensitive polypeptide hydrogels on cartilage repair. Acta Biomater. 73, 103–111. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2018.04.035

Lomas, A. J., Ryan, C., Sorushanova, A., Shologu, N., Sideri, A., Tsioli, V., et al. (2015). The past, present and future in scaffold-based tendon treatments. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 84, 257–277. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2014.11.022

Lynch, H. A. (2003). Effect of fiber orientation and strain rate on the nonlinear uniaxial tensile material properties of tendon. J. Biomech. Eng. 125, 726–731. doi: 10.1115/1.1614819

Maceri, F., Marino, M., and Vairo, G. (2012). An insight on multiscale tendon modeling in muscle-tendon integrated behavior. Biomech. Model. Mechanobiol. 11, 505–517. doi: 10.1007/s10237-011-0329-8

Meimandi-Parizi, A., Oryan, A., and Moshiri, A. (2013). Tendon tissue engineering and its role on healing of the experimentally induced large tendon defect model in rabbits: a comprehensive in vivo study. PLoS ONE 8:e73016. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0073016

Oftadeh, R., Connizzo, B. K., Tavakoli Nia, H., Ortiz, C., and Grodzinsky, A. J. (2018). Biological connective tissues exhibit viscoelastic and poroelastic behavior at different frequency regimes: application to tendon and skin biophysics. Acta Biomater. 70, 249–259. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2018.01.041

Orgel, J. P., Irving, T. C., Miller, A., and Wess, T. J. (2006). Microfibrillar structure of type i collagen in situ. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 9001–9005. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0502718103

Papadopoulos, V., Giovanis, D. G., Lagaros, N. D., and Papadrakakis, M. (2012). Accelerated subset simulation with neural networks for reliability analysis. Computer Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. 223–224, 70–80. doi: 10.1016/j.cma.2012.02.013

Ratcliffe, A., Butler, D. L., Dyment, N. A., Cagle, P. J., Proctor, C. S., Ratcliffe, S. S., et al. (2015). Scaffolds for tendon and ligament repair and regeneration. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 43, 819–831. doi: 10.1007/s10439-015-1263-1

Rawson, S. D., Margetts, L., Wong, J. K. F., and Cartmell, S. H. (2015). Sutured tendon repair; a multi-scale finite element model. Biomech. Model. Mechanobiol. 14, 123–133. doi: 10.1007/s10237-014-0593-5

Reese, S. P., Ellis, B. J., and Weiss, J. A. (2013). Micromechanical model of a surrogate for collagenous soft tissues: development, validation and analysis of mesoscale size effects. Biomech. Model. Mechanobiol. 12, 1195–1204. doi: 10.1007/s10237-013-0475-2

Reese, S. P., Maas, S. A., and Weiss, J. A. (2010). Micromechanical models of helical superstructures in ligament and tendon fibers predict large Poisson's ratios. J. Biomech. 43, 1394–1400. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2010.01.004

Robinson, P. S., Lin, T., Jawad, A., Iozzo, R., and Soslowsky, L. (2004). Investigating tendon fascicle structure-function relationships in a transgenic-age mouse model using multiple regression models. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 32, 924–931. doi: 10.1023/B:ABME.0000032455.78459.56

Salathe, E. P., and Arangio, G. (1990). The foot as a shock absorber. J. Biomech. 23, 655–659. doi: 10.1016/0021-9290(90)90165-Y

Sandri, M., Filardo, G., Kon, E., Panseri, S., Montesi, M., Iafisco, M., et al. (2016). Fabrication and pilot in vivo study of a collagen-BDDGE-elastin core-shell scaffold for tendon regeneration. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 4:52. doi: 10.3389/fbioe.2016.00052

Screen, H. (2008). Investigating load relaxation mechanics in tendon. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 1, 51–58. doi: 10.1016/j.jmbbm.2007.03.002

Shen, Z. L. (2010). Tensile Mechanical Properties of Isolated Collagen Fibrils Obtained by Micro Electrochemical Systems Technology. Ph.D. thesis. Case Western Reserve University.

Snedeker, J. G., and Foolen, J. (2017). Tendon injury and repair—a perspective on the basic mechanisms of tendon disease and future clinical therapy. Acta Biomater. 63, 18–36. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2017.08.032

Starborg, T., Kalson, N. S., Lu, Y., Mironov, A., Cootes, T. F., Holmes, D. F., et al. (2013). Using transmission electron microscopy and 3View to determine collagen fibril size and three-dimensional organization. Nat. Protocols 8, 1433–1448. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2013.086

Svensson, R. B., Hansen, P., Hassenkam, T., Haraldsson, B. T., Aagaard, P., Kovanen, V., et al. (2012). Mechanical properties of human patellar tendon at the hierarchical levels of tendon and fibril. J. Appl. Physiol. 112, 419–426. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01172.2011

Svensson, R. B., Hassenkam, T., Grant, C. A., and Magnusson, S. P. (2010). Tensile properties of human collagen fibrils and fascicles are insensitive to environmental salts. Biophys. J. 99, 4020–4027. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2010.11.018

Swedberg, A. M., Reese, S. P., Maas, S. A., Ellis, B. J., and Weiss, J. A. (2014). Continuum description of the Poisson's ratio of ligament and tendon under finite deformation. J. Biomech. 47, 3201–3209. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2014.05.011

Taflanidis, A., and Beck, J. L. (2013). Prior and posterior robust stochastic predictions for dynamical systems using probability logic. Int. J. Unc. Qunt. 3, 271–288. doi: 10.1615/int.j.uncertaintyquantification.2012003641

Tang, J., Chen, J., Guo, J., Wei, Q., and Fan, H. (2018). Construction and evaluation of fibrillar composite hydrogel of collagen/konjac glucomannan for potential biomedical applications. Regen. Biomater. 5, 239–250. doi: 10.1093/rb/rby018

Thorpe, C. T., Klemt, C., Riley, G. P., Birch, H. L., Clegg, P. D., and Screen, H. R. C. (2013). Helical sub-structures in energy-storing tendons provide a possible mechanism for efficient energy storage and return. Acta Biomater. 9, 7948–7956. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2013.05.004

Thorpe, C. T., Riley, G. P., Birch, H. L., Clegg, P. D., and Screen, H. R. (2017). Fascicles and the interfascicular matrix show decreased fatigue life with ageing in energy storing tendons. Acta Biomater. 56, 58–64. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2017.03.024

Thorpe, C. T., Riley, G. P., Birch, H. L., Clegg, P. D., and Screen, H. R. C. (2014). Fascicles from energy-storing tendons show an age-specific response to cyclic fatigue loading. J. R Soc. Interface 11:20131058. doi: 10.1098/rsif.2013.1058

Wu, J., Yuan, H., Li, L., Fan, K., Qian, S., and Li, B. (2018). Viscoelastic shear lag model to predict the micromechanical behavior of tendon under dynamic tensile loading. J. Theor. Biol. 437, 202–213. doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2017.10.018

Yahia, L. H., and Drouin, G. (1989). Microscopical investigation of canine anterior cruciate ligament and patellar tendon: collagen fascicle morphology and architecture. J. Orth. Res. 7, 243–251. doi: 10.1002/jor.1100070212

Zhang, J., Zheng, T., Alarçin, E., Byambaa, B., Guan, X., Ding, J., et al. (2017). Biomedicine: porous electrospun fibers with self-sealing functionality: an enabling strategy for trapping biomacromolecules. Small 13:1770249. doi: 10.1002/smll.201770249

Zhang, Z. J., Ng, G. Y., Lee, W. C., and Fu, S. N. (2014). Changes in morphological and elastic properties of patellar tendon in athletes with unilateral patellar tendinopathy and their relationships with pain and functional disability. PLoS ONE 9:e108337. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0108337

Appendix

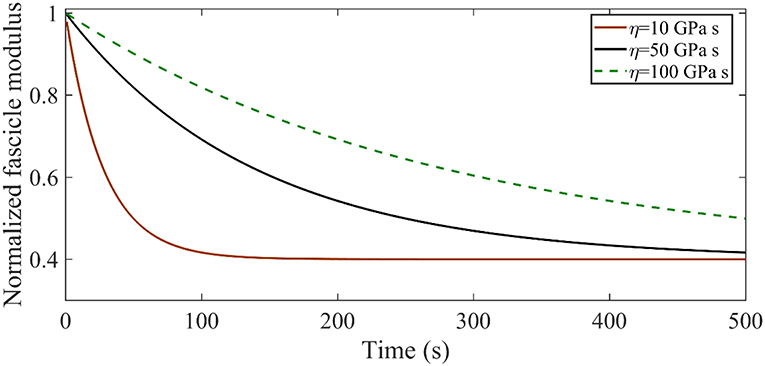

Fascicle Relaxation Response

The time-dependent relaxation response of tendon fascicles depends on both their elastic properties E∞, ER as indicated by Equation 1 on their viscosity ηf. In Figure A1 we provide an insight in the role of the effective viscosity parameter ηf on the form of the relaxation curve. To that scope, we compute the relaxation response of a tendon fascicle with an initial zero-time (t = 0) elastic modulus Efasc(0) = 600 MPa (with an Ef = 1025 MPa Em = 0.4 MPa fr = 0.65 θ = 72o) and a relaxing elastic modulus ER = 720 MPa for viscosity values of ηf = 10 GPa s ηf = 50 GPa s and ηf = 100 GPa s.

Figure A1. Relaxation response for an initial elastic modulus Efasc = 600 MPa with a relaxing elastic modulus ER = 720 MPa for different viscosity values η.

Figure A1 suggests that increasing the viscosity parameter η results in higher time-dependent moduli values Efasc(t), with the maximum difference to amount to several hundreds of MPa. As an example, for η = 10 GPa s at t = 100s the structure has relaxed to Efasc(100) = 240 MPa, while for η = 50 GPa s the corresponding value is Efasc(100) = 420 MPa.

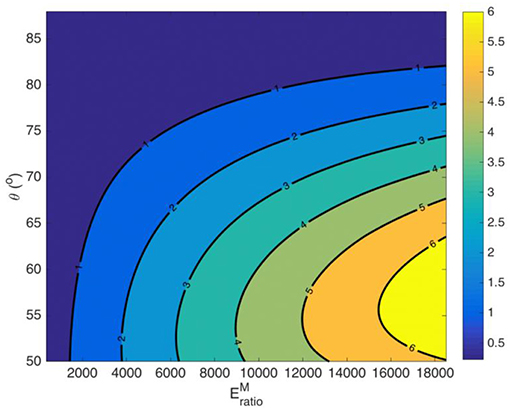

Fascicle Poisson Ratio

The effective Poisson ratio of the fascicle νfasc hinges on both the material properties of the fiber and the matrix (Ef, Em) and on its geometric arrangement (fr, θ) [21, 25]. As a result, different volumetric fascicle behaviors are obtained depending on the set of parameters selected. In Figure A2, we provide the effective Poisson's ratio values for a case study with a fibrillar content fr = 0.6 over different helix angles θ and for different ratios of the fiber modulus to the matrix modulus , computed for a matrix modulus value of Em = 1.

Figure A2. Fascicle effective Poisson ratio values for a fiber content fr = 0.6 and a matrix modulus Em = 1 MPa.

Figure A2 suggests a highly non-linear relation between the moduli ratio value and the fascicle's Poisson's ratio value, which depends on both the fibrillar content fr and on the fiber angle θ.

Keywords: tendon, tissue engineering, biomaterials, viscoelasticity, fibers, relaxation, matrix

Citation: Karathanasopoulos N and Ganghoffer J-F (2019) Exploiting Viscoelastic Experimental Observations and Numerical Simulations to Infer Biomimetic Artificial Tendon Fiber Designs. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 7:85. doi: 10.3389/fbioe.2019.00085

Received: 18 January 2019; Accepted: 05 April 2019;

Published: 07 May 2019.

Edited by:

Nihal Engin Vrana, Protip Medical, FranceReviewed by:

Jianxun Ding, Changchun Institute of Applied Chemistry (CAS), ChinaGarrett Brian McGuinness, Dublin City University, Ireland

Copyright © 2019 Karathanasopoulos and Ganghoffer. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Nikolaos Karathanasopoulos, bmthcmF0aGFAZXRoei5jaA==

Nikolaos Karathanasopoulos

Nikolaos Karathanasopoulos Jean-Francois Ganghoffer

Jean-Francois Ganghoffer