Introduction: Reverse total shoulder arthroplasty (RTSA) retrieval humeral cups commonly exhibit damage in the inferior quadrant[1]-[3]. Reported simulator wear rates range from 4-125 mm3/Mc using various motion and loading conditions[4]-[8]. The present study assesses the wear of non-crosslinked RTSA implants using a custom wear simulation strategy[8], based in part on the load magnitudes and directions found in cadaveric RTSA reconstructed shoulder testing. This was expected to produce wear in the same locations as occurs in vivo and to help assess whether simulator wear rates could be high enough to cause clinical concerns regarding osteolysis.

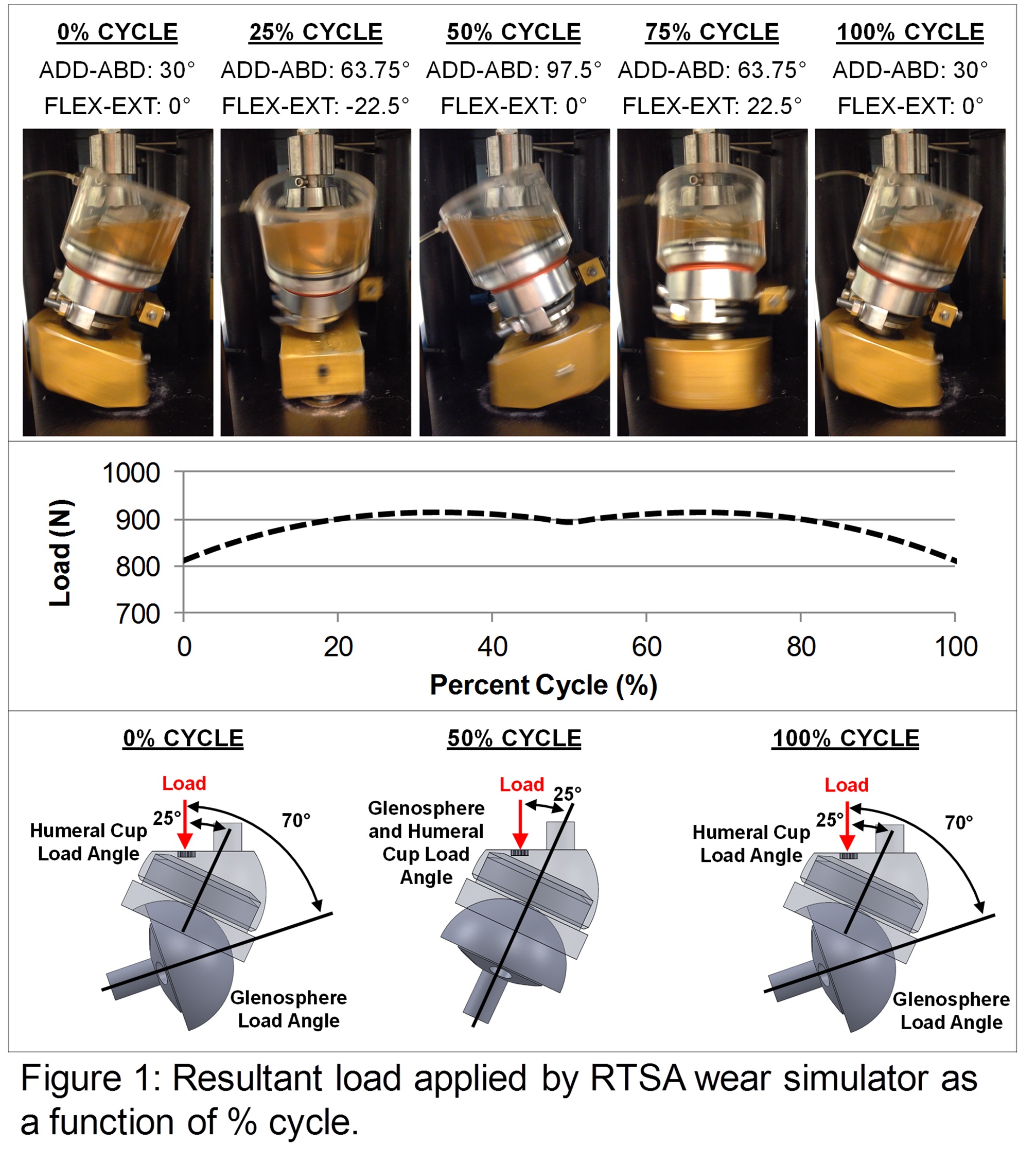

Methods: A modified orbital bearing hip wear simulator gave an adduction-abduction range of 30-97.5° and flexion-extension range of ±22.5°. A transient load profile with a 914 N peak was applied (Figure 1) similar to that observed in RTSA reconstructed cadaveric shoulders[8]. Wear testing was performed at 1.13 Hz for 1.44 Mc on eight RTSA implants (DePuy Delta XTEND, size: 38 mm). Following previous knee simulator wear testing[9],[10], the lubricant was bovine calf serum diluted with PBS to a 30 g/L protein concentration, with sodium hyaluronate (1.5 g/L) and an antibiotic-antimycotic (1%). Every 0.25 Mc, the specimens were cleaned and weighed.

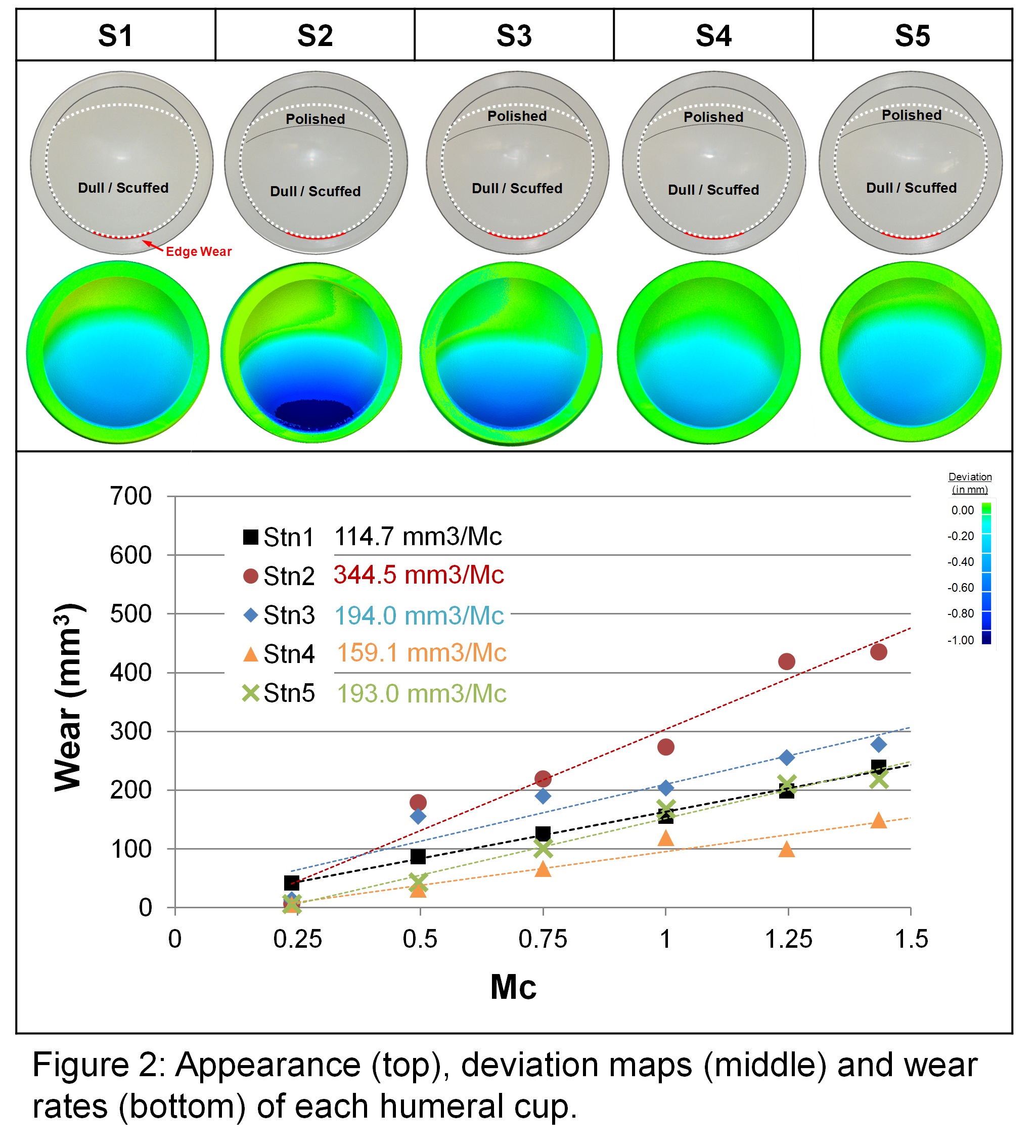

Results: All cups exhibited a large wear scar with a dull (non-reflective) scuffed appearance covering the entire intended articular surface, with only the superior-most surface remaining pristine (Figure 2). Four specimens exhibited a distinct thinner polished region near the superior wear scar margin. Inferior edge wear was present on all cups (red lines). Within the contact zone, all glenospheres exhibited light surface scratching, and after every 0.25 Mc there was some surface staining present, which was removed during ultrasonic cleaning. The wear rates of the humeral cups had considerable variation, with a range of 115 to 345 mm3/Mc (Figure 2), and a mean wear rate of 201 ± 87 mm3/Mc.

Discussion: The present study had by far the highest rate compared to other wear studies[4]-[7], although there was little consensus regarding simulator conditions. No other studies incorporated HA in their lubricant, which has been shown to increase wear rate[9],[10]. An earlier pilot study[8] used alpha calf serum and had a much lower wear rate, suggesting that the higher wear may be a consequence of the lubricant. The inferiomedial cup edge had considerable wear in the present simulator testing, similar to that found in clinical retrievals[1]-[3], damage which would have a detrimental effect on both contact mechanics and potentially the stability of the reconstructed joint in vivo.

Conclusions: The high wear rate in the present study suggests that RTSA wear could become a long term clinical problem for the more active patients. Highly crosslinked polyethylene humeral cups may reduce wear[6],[7] but this substitution may exacerbate problems associated with scapular notching[6] and thus new RTSA designs may also be needed.

References:

[1] Nam et al (2010) Observations on retrieved humeral polyethylene components from reverse total shoulder arthroplasty. JSES, 19, 1003-12, 2010

[2] Day et al (2012) Polyethylene wear in retrieved reverse total shoulder components. JSES, 21, 667-74

[3] Wiater et al (2015) Elucidating trends in revision reverse total shoulder arthroplasty procedures: a retrieval study evaluating clinical radiographic, and functional outcomes data. JSES, in press

[4] Kohut et al (2012) Wear-induced loss of mass in reversed total shoulder arthroplasty with conventional and inverted bearing materials. J Biomech, 45, 469-73

[5] Vaupel et al (2012) Wear simulation of reverse total shoulder arthroplasty systems: effect of glenosphere design. JSES, 21, 1422–9

[6] Peers et al (2015) Wear rates of highly cross-linked polyethylene humeral liners subjected to alternating cycles of glenohumeral flexion and abduction. JSES, 24, 143–9

[7] Haider et al (2013) A method for wear testing of reverse shoulder arthroplasty systems. Bone Jt J 95-B, Sup 34, 607

[8] Langohr et al (2015) Wear simulation strategies for reverse total shoulder arthroplasty implants. Sub to IMechE, Pt H, J of Eng in Med

[9] DesJardins et al (2006) Increased total knee arthroplasty ultra-high molecular weight polyethylene wear using a clinically relevant hyaluronic acid simulator lubricant. IMechE, Pt H, J Eng in Med, 220, 609-23

[10] Brandt et al (2013) Antimicrobial agents and low-molecular weight polypeptides affect polyethylene wear in knee simulator testing. Trib Internat, 26, 97-104